Abstract

Background

Nuclear medicine is an interdisciplinary field that integrates basic science with clinical medicine. The traditional classroom teaching model lacks interactive and efficient teaching methods and does not adequately address the learning needs and educational goals associated with standardized training for residents. The teaching model that combines Small Private Online Courses (SPOCs) with a flipped classroom approach is more aligned with the demands of real-life scenarios and workplace requirements, thereby assisting students in developing comprehensive literacy and practical problem-solving skills. However, this innovative teaching model has yet to be implemented in Nuclear medicine courses. This study aimed to explore whether the post-training competence for residents can be improved based on this new teaching model.

Methods

A total of 103 first-year residents from Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital were randomly assigned to either an experimental group (n = 52) or a control group (n = 51) between July 2019 and June 2023. The experimental group utilized a SPOC and flipped classroom-blended teaching model, while the control group received traditional lecture-based learning (LBL). We assessed the theoretical evaluation scores and questionnaire responses from both groups to determine the effectiveness of the new pedagogical approach.

Results

Residents in the experimental group demonstrated a superior understanding of nuclear medicine content compared to those in the control group, achieving higher scores on pre-class assessments, after-class tests, and final exams (P < 0.01). A majority of the residents in the experimental group expressed that the innovative teaching model, which integrated SPOC and a flipped classroom approach, significantly enhanced their motivation and contributed to the development of their ‘professional skills,’ ‘patient care,’ ‘interaction and teamwork,’ ‘teaching proficiency,’ and ‘learning capabilities’. The teaching satisfaction survey indicated that the experimental group reported significantly higher levels of ‘overall satisfaction,’ as well as greater satisfaction with ' teaching methodologies ' and ' fulfillment of targeted clinical skills,’ compared to the control group (P < 0.01).

Conclusions

The SPOC and flipped classroom teaching model is better than traditional LBL in enriching residents’ professional knowledge and cultivating their post-training competence. It can effectively promote educational quality, improve residents’ learning, and enhance their satisfaction.

Keywords: Nuclear medicine, Small private online courses, Flipped classroom, Lecture-based learning, Standardised resident training

Introduction

The rapid development of information technology has enabled the widespread use of the Internet, particularly within educational environments [1]. The flipped classroom represents an innovative instructional approach that reorganizes the allocation of time both in class and outside of it, transferring the authority over learning from educators to learners. Within this framework, teachers dedicate less time to articulating knowledge points in detail during class sessions. Instead, they allocate more time to addressing student questions and expanding their understanding, necessitating that students engage in self-directed learning during their own time. This approach to the flipped classroom has led to notable enhancements in students’ capacity for independent study [2]. Additionally, the interaction between educators and learners fosters a deeper comprehension of content among students and tends to boost their overall enthusiasm for learning [3]. Flipped classroom teaching model is very open, and its internal link can be com bined with other methods to achieve a better teaching efect. The flipped classroom approach aligns with the demands of the information age by ‘reversing’ the traditional spatiotemporal order [4]. There has been an increase in studies on flipped classrooms during recent years as well as some promising results. As the beneffts of flipped classroom, its use is increasingly being adopted in medical education, such as nursing [5], pharmacology [6], ophthalmology [7, 8], radiology, epidemiology, and podiatric medical education [9, 10].

The introduction of massive open online courses (MOOCs) in 2012 has triggered a transformation in online education. Nonetheless, in spite of the existing opportunities, MOOCs encounter the difficulty of combining online courses with traditional classroom instruction. Additionally, issues such as low student engagement, high dropout rates, and the diverse backgrounds of students represent significant challenges [11]. In 2013, Professor Armando Fox at the University of California, Berkeley, introduced the concept of small private online courses (SPOCs) [12]. The SPOC platform, built upon the foundation of MOOCs, provides a wealth of educational resources comparable to those available in MOOCs [13]. Additionally, it features streamlined management procedures and reduced administrative costs. By combining the advantages of virtual and in-person instruction, SPOCs serve as a robust foundation for knowledge acquisition in a flipped classroom setting [14]. The integration of flipped classrooms and SPOCs is set to invigorate course instruction [15–17]. The teaching model of SPOCs combined with the flipped classroom approach has yielded positive results and has received recognition from students. This model exemplifies the value of online education in Chinese universities. By leveraging the strengths of both methodologies, educators can create a more engaging, personalized, and effective learning environment.

Standardized training for residents is critically important in the field of medical education for graduates. In China, participation in resident training is mandatory for medical students to develop their proficiency as physicians [18, 19]. Nuclear medicine, an interdisciplinary field that integrates basic science with clinical medicine, has established a new independent professional training base. This discipline requires a high degree of practical skills, necessitating that the training curriculum for nuclear medicine residents encompasses multiple domains, including medical ethics, specialized knowledge, practical skills, clinical reasoning, effective communication with patients, and the capacity for scientific inquiry [20, 21]. In China, standardized training for nuclear medicine residents remains in its early stages and encounters several challenges, such as the uneven development of disciplines, insufficient awareness of teaching methodologies, and the lack of comprehensive assessment and evaluation systems [22]. The traditional model of teaching nuclear medicine restricts residents’ acquisition of knowledge and skills. In traditional nuclear medicine education, residents often passively receive information through teacher-centered lectures, leading to a lack of independent thinking and learning. Additionally, conventional classroom settings do not provide enough time for meaningful discussion and interaction with peers and instructors, resulting in delayed resolution of residents’ queries. Furthermore, traditional assessment methods mainly rely on final exam scores, which fail to offer a comprehensive and accurate evaluation of the entire learning experience. Consequently, it is essential to implement innovative teaching strategies to enhance residents’ learning effectiveness in this demanding course.

Considering the benefits and advantages of flipped classrooms alongside SPOCs, these approaches could be effective in transforming traditional classrooms to cater to student needs. Furthermore, integrating these methods might yield improved results in the standardized training of nuclear medicine residents. Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, research assessing the efficacy of a pedagogy that merges flipped classrooms and SPOCs in educating nuclear medicine residents is currently lacking.

The present study was conducted to implement a SPOC based on the flipped classroom model in the field of nuclear medicine. This research aims to explore strategies for improving the quality of nuclear medicine education and enhancing the learning experience and outcomes for residents undergoing standardized training by integrating the teaching methodologies of SPOC and the flipped classroom.

Methods

Participants and study setting

This prospective study involved first-year residents from Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital specializing in nuclear medicine. All residents had successfully completed a standardized training entrance exam, achieving similar scores that indicate comparable levels of foundational knowledge. A total of 103 residents participated in the study, which divided them randomly into an experimental group (n = 52) and a control group (n = 51). Each resident’s course was conducted over one academic year, and the project spanned from July 2019 to June 2023. A flow diagram illustrating participant enrollment and the study profile is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participant enrollment and study profile

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital.

Intervention

The instructional materials and timing arrangements for the two groups were determined by the Content and Standard of Standardised Training for Residents. The course description was made public two to three weeks prior to the course commencement, mandating residents to thoroughly read and acquaint themselves with the details. At least twice a week, we shared updates on the progress and dynamics of nuclear medicine through the network platform, allowing residents to gain insights into the latest advancements both domestically and internationally.

‘SPOC + fipped classroom’ model design

The experimental group participants were segmented into multiple groups, each comprising four to five students. The diagram in Fig. 2 illustrates the experiential learning processes of the classes.

Fig. 2.

The schematic diagram of the teaching processes of the experiment class

Organise pre-class tasks

Following the learning assignments assigned by the instructors, participants independently viewed video lectures and PowerPoint presentations before the scheduled class sessions. The instructional video was created based on the principle of ‘simple and practical’. All videos lasted about 8–10 min and were divided into four sections: introduction of concepts, explanation of concepts, classic examples, and summary of knowledge. Learners had the ability to adjust the speed of video playback and determine their study duration independently. The experimental groups were required to complete a quiz consisting of 20 questions following the pre-class tasks.

Carry out the classroom teaching

The experimental group employed a 2-hour weekly blended teaching strategy that combined the SPOC platform with an offline flipped classroom model. Content was aligned with the guidelines for training in the field of nuclear medicine, and instructional videos were created for each key concept. During the teaching process, the classroom should also be problem-oriented and fully develop residents’ subjective initiative. For example, should renal dynamic imaging be performed during the preoperative assessment of renal function in patients with renal tumours? Are other techniques available for assessing renal function? What are the most commonly used imaging agents for renal dynamic imaging? What imaging agents are used for renal tubule secretory and glomerular filtration nuclides? What are the most commonly used evaluation indicators? What is the clinical significance of a continuously ascending, parabolic, and low-level elongated nephrogram? What are the interventional renal dynamic imaging tests for upper urinary tract obstruction and renal vascular hypertension? What are the common factors affecting the results of renal dynamic imaging? What are the clinical indications for and common imaging agents used in static renal imaging? Through a series of progressive questions, it is helpful for residents to clearly sort out the relevant knowledge points of renal dynamic imaging, so as to achieve the inevitable teaching effect of understanding its nature.

The classroom learning process was divided into three distinct stages:

① In the flipped classroom setting, each group was assigned a random question to explore, with a resident doctor tasked to explain and present the findings. The resident doctor could present a report based on a pre-prepared PPT, and elaborate on the main points and challenges of the chapter while incorporating case data. The presentation time was limited to 15 min.

② In the context of group discussions, prior to the class session, residents participated in analytical and interactive discussions on various study topics. These discussions were overseen by two instructors who facilitated the dialogue and assessed participation. These instructors served as facilitators and mentors, guiding residents towards independent problem-solving and fostering a spirit of curiosity for exploring new information. While this phase emphasized student involvement, instructors were advised to monitor the pace and timing of discussions, actively observe interactions, and offer guidance as needed to ensure a productive learning environment.

③ After the discussion, each study group designated a member to report the results of the discussion (including answers or solutions to relevant questions) and put forward doubts that still exist. The teacher made a brief comment on each group of reports, made a targeted evaluation of residents’ performance and discussion results, concentrated answers to common questions reflected by all residents and face-to-face answers to non-common questions, and implemented personalised guidance to highlight teachers’ classroom leadership. In addition, to strengthen residents’ subjectivity in flipped classrooms, they could carry out mutual evaluations. Based on the class test questions reported by the residents in the course, the teacher compiled the class test questions of this class. The resident doctors’ self-assessment and teacher evaluation forms are shown in Tables S1 and S2.

Ability extension after class

One or two advanced tasks were released after class to reinforce the residents’ learning. The teachers set topics for each item according to the training requirements. The residents collected and sorted the answers for each topic through self-study and consulting literature and materials, etc. After the residents finished and submitted their homework, the teacher corrected it in a timely fashion and explained the residents’ answers on the network platform.

Conventional lecture-based learning model design

The control group residents engaged in the lecture-based learning (LBL) teaching approach, primarily preparing through textbook reading for 10–15 min instead of viewing videos prior to class. They were then required to complete an identical quiz consisting of 20 questions. During the classroom learning process, instructors utilized PowerPoint presentations to clarify topics related to nuclear medicine in a traditional lecture format.

Evaluating the effect of teaching model application

Knowledge evaluation

The knowledge evaluation was based on a quiz before the class, an after-class test with standardised answers, and final exam results.

Collect questionnaires

After finishing all the class, the survey was distributed to the participants, who were instructed to complete it promptly and submit it. The assessment focused on the effectiveness of the two teaching techniques as well as the residents’ satisfaction with the educational approaches employed by both groups. The questionnaires were completed voluntarily and submitted anonymously.

Instruments

Knowledge assessment

I. Quiz Before the Class: The residents participating in this study completed a quiz comprising 20 questions after the pre-class tasks. This quiz assessed their understanding and mastery of the course material following the completion of the pre-class tasks. It consisted of objective questions, with a maximum score of 100 points.

II. After-Class Test: The residents who participated in the study underwent assessments after each course. The content of these tests encompassed the nuclear medicine theories and skills outlined in the standardized training and assessment syllabus that residents are expected to master at their current stage of study. The test questions could be either objective or subjective, with a maximum score of 100 points. III. Final Exam: Upon completion of all classes, the students took a final theoretical and practical examination. The operation of nuclear medicine imaging equipment was conducted as the final practical performance test. The performance scores were evaluated by instructors according to standardized criteria. The final total score comprised the examination paper score (50%) and the operational performance score (50%), with a maximum score of 100 points.

Course satisfaction

Residents’ contentment with the educational approaches of both groups was assessed across five different areas: overall contentment, satisfaction with instructional methods, approval of instructors, satisfaction with daily instructional practices at the facility, and satisfaction with the attainment of specified clinical competencies. The contents of the questionnaire are presented in Tables S3.

Course effectiveness

The effectiveness of the two teaching techniques was evaluated based on the following six aspects: competence in the field, proficiency, management of patients, communication skills, teamwork, teaching skills, and improvement in learning capabilities. The contents of the questionnaire are presented in Tables S4.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software (version 22.0) was utilized for data analysis. Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations, and the Student’s t-test was employed to compare the mean scores of tests etween two different teaching models. Categorical data were represented as proportions or percentages and analyzed using the Chi-square test. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05.

Results

Population Study characteristics

A total of 52 residents were enrolled in the experimental group, which included 25 men and 27 women aged between 23 and 28 years, with a mean age of 24.9 ± 1.6 years. The control cohort comprised 51 residents, consisting of 22 males and 29 females aged between 23 and 29 years, with a mean age of 25.2 ± 1.9 years. No significant differences in gender or age were observed between the two groups.

Knowledge evaluation

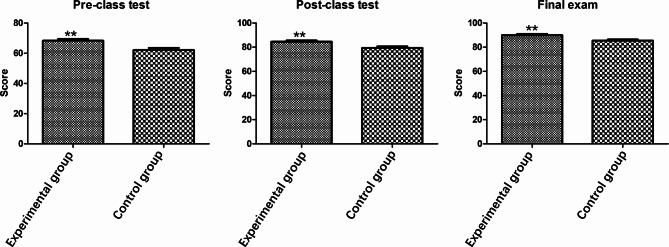

Both the experimental and control groups underwent the same test. The experimental group comprised 52 residents, who achieved average scores of 68.31 ± 8.13, 84.54 ± 7.09, and 89.98 ± 6.78 on the pre-class and post-class tests, and the final exam, respectively. In contrast, the control group included 51 residents, with average scores of 62.05 ± 11.04, 79.37 ± 8.93, and 85.43 ± 6.67 on the same assessments (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The pre-class, post-class test scores, and final exam results of both the experimental and control groups. The experimental group achieved significantly higher scores than the control group, with pre-class scores of 68.31 ± 8.13 compared to 62.05 ± 11.04, post-class scores of 84.54 ± 7.09 versus 79.37 ± 8.93, and final exam scores of 89.98 ± 6.78 against 85.43 ± 6.67, respectively (t = 3.264, 3.253 and 3.431, all P < 0.01). **P < 0.01

To evaluate the effectiveness of the ‘SPOC + flipped classroom’ model in enhancing the overall performance of residents, we conducted a comparative analysis of pre-class and post-class test scores, as well as final exam results, between the control and experimental groups using Student’s t-test. The analysis indicated that the scores of the experimental group were significantly higher than those of the control group (t = 3.264, 3.253 and 3.431, all P < 0.01) (refer to Table 1). These findings suggest that a SPOC based on the flipped classroom model represents a superior approach for significantly improving pre-class, post-class and final examination scores.

Table 1.

Comparison of the average scores of preclass, after-class and final exam between two groups

| Groups | Pre-class test scores (‾x ± s ) |

After-class test scores (‾x ± s ) | Final exam scores (‾x ± s ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group | 68.31 ± 8.13 | 84.54 ± 7.09 | 89.98 ± 6.78 |

| Control group | 62.05 ± 11.04 | 79.37 ± 8.93 | 85.43 ± 6.67 |

| t | 3.264 | 3.253 | 3.431 |

| P | 0.002** | 0.002** | 0.001** |

**P < 0.01

Residents’ satisfaction with the two educational approaches

Table 2 presents the five aspects of the satisfaction survey concerning the teaching approaches experienced by both groups. Significant differences were observed between the experimental and control groups in the areas of ‘overall satisfaction,’ ‘teaching methodologies,’ and ‘fulfillment of targeted clinical skills’ (χ2 = 18.391, 24.832, and 10.228, respectively; all P < 0.01). In contrast, no significant differences were found in ‘instructors’ and ‘daily educational activities’ between the experimental and control groups (χ2 = 0.320 and 2.956, all P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Evaluation of teaching method satisfaction

| Items | Groups | Very satisfied | General satisfied | Dissatisfied | χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall satisfaction | SPOC + flipped classroom |

12 (23.08%) |

30 (57.69%) |

10 (19.23%) |

18.391 | 0.000** | |

| Control | 2(3.92%) | 20(39.22%) | 29(56.86%) | ||||

| Teaching methodologies | SPOC + flipped classroom |

24 (46.15%) |

19 (36.54%) |

9 (17.31%) |

24.832 | 0.000** | |

| Control | 4(7.84%) | 18(35.29%) | 29(56.87%) | ||||

| Instructors | SPOC + flipped classroom |

10 (19.23%) |

32 (61.54%) |

10 (19.23%) |

0.320 | 0.852 | |

| Control | 12(23.53%) | 29(56.86%) | 10(19.61%) | ||||

| Daily educational activities | SPOC + flipped classroom |

10 (19.23%) |

25 (48.08%) |

17 (32.69%) |

2.956 | 0.228 | |

| Control | 6(11.76%) | 33(64.71%) | 12(23.53%) | ||||

| Fulfillment of targeted clinical skills | SPOC + flipped classroom |

14 (26.92%) |

25 (48.07%) |

13 (25.01%) |

10.228 | 0.006** | |

| Control | 4(7.84%) | 21(41.18%) | 26(50.98%) | ||||

**P < 0.01

Effectiveness of the two teaching techniques

Table 3 presents the results of the questionnaire assessing the effectiveness of the two teaching methods across six items. We employed both numerical values and percentages to illustrate the residents’ attitudes. Notably, significant discrepancies were observed between the experimental and control groups in the areas of ‘professional skills,’ ‘patient care,’ ‘interaction and teamwork,’ ‘teaching proficiency,’ and ‘learning capabilities’ (χ2 = 35.397, 19.406, 38.606, 17.959, and 23.336, respectively; all P < 0.001). However, no significant variance was found in ‘professional standards’ between the experimental and control groups (χ2 = 0.635, P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Evaluation of teaching method effectiveness

| Items | Groups | Strongly agree | Agree | Disagree | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional standards | SPOC + flipped classroom | 8(15.38%) | 30(57.70%) | 14(26.92%) | 0.635 | 0.728 |

| Control | 6(11.76%) | 28(54.90%) | 17(33.34%) | |||

| Professional skills | SPOC + flipped classroom | 14(26.92%) | 30(57.69%) | 8(15.39%) | 35.397 | < 0.001** |

| Control | 2(3.92%) | 12(23.53%) | 37(72.55%) | |||

| Patient care | SPOC + flipped classroom | 10(19.23%) | 34(65.38%) | 8(15.39%) | 19.406 | < 0.001** |

| Control | 4(7.84%) | 18(35.29%) | 29(56.87%) | |||

| Interaction and teamwork | SPOC + flipped classroom | 14(26.92%) | 29(55.77%) | 9(17.31%) | 38.606 | < 0.001** |

| Control | 4(7.84%) | 7(13.73%) | 40(78.43%) | |||

| Teaching proficiency | SPOC + flipped classroom | 13(25%) | 24(46.15%) | 15(28.85%) | 17.959 | < 0.001** |

| Control | 5(9.80%) | 10(19.60%) | 36(70.60%) | |||

| Learning capabilities | SPOC + flipped classroom | 11(21.15%) | 27(51.92%) | 14(26.93%) | 23.336 | < 0.001** |

| Control | 4(7.84%) | 9(17.65%) | 38(74.51%) |

**P < 0.01

Discussion

This study presents the design of a SPOC in conjunction with a flipped-classroom model as a blended learning activity in the standardized training of nuclear medicine residents. Our findings demonstrate that this educational approach has effectively enhanced the residents’ academic performance and positively influenced their overall job competency. Furthermore, high levels of residents satisfaction were observed across multiple aspects. Through the adoption of the blended teaching model for standardized training and educational initiatives for residents in the Nuclear Medicine Department, we have presented novel concepts and established new methodologies that can aid research efforts for up-and-coming scholars in the realm of nuclear medicine education.

In our study, we found that the video lecture-based preview was more effective than the textbook-based preview when comparing the pre-class scores of the two groups of residents. This outcome may arise from the interdisciplinary nature of nuclear medicine, which encompasses nuclear physics, electronics, chemistry, biology, computer technology, and other related fields. Consequently, residents may find it difficult to grasp the relevant professional knowledge through traditional textbook-based preview methods. In contrast, a lecture-based video preview approach can provide a more engaging learning experience for residents who are new to the field of nuclear medicine. Furthermore, the SPOC model employed outside the classroom proves advantageous for residents, as it allows for multiple viewings of instructional videos, thereby enabling a deeper understanding of key concepts at their own pace. This finding aligns with those reported in the literature [23–26]. By incorporating these innovative pedagogical strategies, we can create a more interactive and intellectually stimulating educational environment that caters to the diverse learning needs of all residents.

Furthermore, this study demonstrated that the implementation of the blended teaching method significantly enhanced residents’ academic performance in post-class assessments and the final examination. In a similar vein, Zhang et al. [11] demonstrated that the incorporation of SPOC into the flipped classroom model resulted in increased scores for students in both pre-class and post-class tests in the physiology course. This result may be attributed to the fact that the blended teaching method enhances teachers’ instructional objectives, empowers residents with the autonomy for independent learning, and improves educational outcomes. It has emerged as a novel concept and teaching model aimed at residents education, particularly in stimulating learning motivation and professional interests, diversifying instructional methods, increasing the attractiveness of teaching, and enhancing interactivity. Furthermore, by deepening the understanding of residents’ performance in both classroom and online learning evaluations, the blended teaching method can foster active learning, promote personalized educational experiences, enhance independent learning capabilities, and develop critical thinking skills, thereby facilitating overall residents’ development.

According to the consensus established by the Resident Core Competency Framework of the China Residency Training Elite Teaching Hospital Alliance, residents should possess six core competencies: professionalism, knowledge and skills, patient care, communication and cooperation, teaching ability, and lifelong learning. The development of these competencies must be achieved through standardized training and practice, ensuring that residents comprehensively master the requisite knowledge and skills in the medical field and are equipped to provide high-quality medical services to patients. The blended learning in our study demonstrated greater efficacy in fostering residents’ skills in analyzing and addressing clinical problems compared to the LBL teaching mode. The questionnaire survey found that residents’ recognition of the blended teaching method was high, with most dimensions of job competency significantly improvesd, including ‘professional skills,’ ‘patient care,’ ‘interaction and teamwork,’ ‘teaching proficiency,’ and ‘learning capabilities’. Residents’ satisfaction with this blended teaching model is reflected in ‘overall satisfaction,’ ‘teaching methodologies,’ and ‘fulfillment of targeted clinical skills’. The blended teaching method has perfectly realised the ‘three-stage guide’ and the full integration of online and offline teaching before, during, and after class. These results are consistent with those reported by Zhou and colleagues [27], who found that the SPOC + flipped classroom model significantly enhances class efficacy and improves student abilities compared to traditional methods. Additionally, most students expressed interest in and satisfaction with this teaching model.

The positive effects were mainly achieved in the following respects: First, the residents carried out effective self-preparatory studies before class. They were able to think for themselves based on the questions asked by the teacher, felt more involved in the process, and knew what they were doing. Second, they could master important and difficult knowledge in class. In daily learning and discussion, they distinguished between primary and secondary points, and through discussions between groups, teachers could provide targeted explanations of difficult problems so that knowledge can be better internalised, which is conducive to better understanding and application. Finally, this enthusiasm for learning continued after class because every study starts with a problem and ends with another new problem, so that everyone was brave and willing to think. More importantly, it enabled residents to learn about their habits. In this concentrated and fragmented learning, residents did not experience much ideological pressure; they unconsciously learned to think, absorb fresh knowledge, and constantly improve their communication.

Nevertheless, there was no notable distinction in the ‘professional quality’ between the trial group and the reference group when assessing the efficacy of the teaching approach. Furthermore, participants expressed equal contentment with ‘instructors’ and ‘daily educational routines’ in both the trial and reference groups. Several factors could account for these findings. Initially, the blended teaching technique remains in its preliminary phase, with instructors lacking teaching expertise and technological glitches frequently compromising instructional standards. Conversely, participants were also acclimating to this novel teaching method; occasionally, disrupted learning outcomes were attributed to a deficient network or equipment, or even external environmental influences.

There were several limitations in the present study. First, the teaching method of SPOC limited the number of participants in this study. Secondly, while this study confirmed the positive impact of the blended teaching model combining ‘SPOC and flipped classroom’ on the standardized training of first-year nuclear medicine residents, the research duration for each physician was only one year, which did not allow for an investigation into the effects of this blended teaching model on the more advanced teaching requirements in the second and third years. Finally, the assessment methods used to evaluate the learning skills of enrolled residents remain rudimentary; thus, these methods require improvement and refinement to more accurately gauge the impact of this blended teaching model.

Conclusion

In this research, a flipped classroom approach based on the SPOC method was implemented for the standardized training of nuclear medicine. Comparing the outcomes of the traditional LBL teaching method with the ‘SPOC + flipped classroom’ approach, it was noted that the latter had a beneficial impact on the post-training competency of residents and enhanced their intrinsic motivation. Enhancements in skills related to professional practice, patient care, communication, collaboration, teaching, and learning may be attributed to the effectiveness of the blended teaching approach in enhancing the post-training competency of nuclear medicine trainees. This new teaching model provides residents with more personalized support, leading to increased satisfaction and motivation, which in turn fosters the internalization of learning motivation and the development of higher levels of autonomy. Nevertheless, it is essential to further refine the ‘SPOC + flipped classroom’ model and conduct long-term assessments to validate its efficacy in educational settings.

Acknowledgements

We thank everyone involved for their efforts in the writing and critical review of this manuscript.

Author contributions

SL and YL designed and carried out the study, KW and ZG contributed to the data analysis, PH and WY creation of the figures, WH and ZW wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81960320).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. Additional data utilized to support the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Clinical trial number not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hao Wang and Wei Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Lu Wei Ye, Email: yeluwei861209@163.com.

Lan Shang, Email: shanglan8282@163.com.

References

- 1.Soufiane O, Mohamed E, Mohamed K. Proposal of a flipped classroom model based on SPOC. RA J Appl Res. 2022;8(5):363–7. 10.47191/rajar/v8i5.06. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chi M, Wang N, Wu Q, Cheng M, Zhu C, Wang X, Hou Y. Implementation of the flipped Classroom combined with problem-based learning in a medical nursing course: a Quasi-experimental Design. Healthc (Basel). 2022;10(12):2572. 10.3390/healthcare10122572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wen H, Hong M, Chen F, Jiang X, Zhang R, Zeng J, Peng L, Chen Y. CRISP method with flipped classroom approach in ECG teaching of arrhythmia for trainee nurses: a randomized controlled study. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):850. 10.1186/s12909-022-03932-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawks SJ. The flipped classroom: now or never. AANA J. 2014;82(4):264–9. PMID: 25167605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Della Ratta CB. Flipping the classroom with team-based learning in undergraduate nursing education. Nurse Educ. 2015;40(2):71–4. 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaughlin JE, Griffin LM, Esserman DA, Davidson CA, Glatt DM, Roth MT, Gharkholonarehe N, Mumper RJ. Pharmacy student engagement, performance, and perception in a flipped satellite classroom. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(9):196. 10.5688/ajpe779196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alabiad CR, Moore KJ, Green DP, Kofoed M, Mechaber AJ, Karp CL. The Flipped Classroom: An Innovative Approach to Medical Education in Ophthalmology. J Acad Ophthalmol (2017). 2020;12(2):e96-96e103. 10.1055/s-0040-1713681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Tang F, Chen C, Zhu Y, Zuo C, Zhong Y, Wang N, Zhou L, Zou Y, Liang D. Comparison between flipped classroom and lecture-based classroom in ophthalmology clerkship. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1395679. 10.1080/10872981.2017.1395679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hew KF, Lo CK. Flipped classroom improves student learning in health professions education: a meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):38. 10.1186/s12909-018-1144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall AM, Conroy ZE. Effective and time-efficient implementation of a flipped-Classroom in Preclinical Medical Education. Med Sci Educ. 2022;32(4):811–7. 10.1007/s40670-022-01572-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang XM, Yu JY, Yang Y, Feng CP, Lyu J, Xu SL. A flipped classroom method based on a small private online course in physiology. Adv Physiol Educ. 2019;43(3):345–9. 10.1152/advan.00143.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox A. From MOOCs to SPOCs. Commun ACM. 2013;56(12):38–40. 10.1145/2535918. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott KW, Dushime T, Rusanganwa V, Woskie L, Attebery C, Binagwaho A. Leveraging massive open online courses to expand quality of healthcare education to health practitioners in Rwanda. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8(4):e000532. 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin YS, Lai YH. Analysis of AI Precision Education Strategy for small private online courses. Front Psychol. 2021;12:749629. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.749629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo CK, Hew KF. Student Engagement in Mathematics flipped classrooms: implications of Journal publications from 2011 to 2020. Front Psychol. 2021;12:672610. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.672610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks L, Kay R. Exploring flipped classrooms in undergraduate nursing and health science: a systematic review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;64:103417. 10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aljaber N, Alsaidan J, Shebl N, Almanasef M. Flipped classrooms in pharmacy education: a systematic review. Saudi Pharm J. 2023;31(12):101873. 10.1016/j.jsps.2023.101873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan W, Li Z, Han J, Chu H, Lu S, Gu S, et al. Improving the resident assessment process: application of app-based e-training platform and lean thinking. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):134. 10.1186/s12909-023-04118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang SL, Chen Q, Liu Y. Medical resident training in China. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:108–10. 10.5116/ijme.5ad1.d8be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham MM, Metter DF. Evolution of nuclear medicine training: past, present, and future. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(2):257–68. PMID: 17268024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arevalo-Perez J, Paris M, Graham MM, Osborne JR. A perspective of the future of Nuclear Medicine Training and Certification. Semin Nucl Med. 2016;46(1):88–96. 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mankoff D, Pryma DA. Nuclear Medicine Training: what now. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(10):1536–8. 10.2967/jnumed.117.190132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng J, Liu L, Tong X, Gao L, Zhou L, Guo A, et al. Application of blended teaching model based on SPOC and TBL in dermatology and venereology. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):606. 10.1186/s12909-021-03042-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lockhart BJ, Capurso NA, Chase I, Arbuckle MR, Travis MJ, Eisen J et al. The Use of a Small Private Online Course to Allow Educators to Share Teaching Resources Across Diverse Sites: The Future of Psychiatric Case Conferences. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(1):81 – 5. 10.1007/s40596-015-0460-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Vaysse C, Chantalat E, Beyne-Rauzy O, Morineau L, Despas F, Bachaud JM, et al. The impact of a small private online course as a New Approach to Teaching Oncology: development and evaluation. JMIR Med Educ. 2018;4(1):e6. 10.2196/mededu.9185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo Y, Liu H, Hao A, Liu S, Zhang X, Liu H. Blended learning model via small private online course improves active learning and academic performance of embryology. Clin Anat. 2022;35(2):211–21. 10.1002/ca.23818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou X, Yu G, Li X, Zhang W, Nian X, Cui J, et al. The application and influence of small private online course based on flipped classroom teaching model in the course of fundamental operations in surgery in China. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):375. 10.1038/s41598-023-50580-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. Additional data utilized to support the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.