Abstract

Research question

Is it possible to predict blastocyst quality, embryo chromosomal ploidy, and clinical pregnancy outcome after single embryo transfer from embryo developmental morphokinetic parameters?

Design

The morphokinetic parameters of 1011 blastocysts from 227 patients undergoing preimplantation genetic testing were examined. Correlations between the morphokinetic parameters and the quality of blastocysts, chromosomal ploidy, and clinical pregnancy outcomes following the transfer of single blastocysts were retrospectively analyzed.

Results

The morphokinetic parameters of embryos in the high-quality blastocyst group were significantly shorter than those in the low-quality blastocyst group (p < 0.05). In contrast, the CC2 time was significantly prolonged (p < 0.05). On chromosomal analysis of biopsy blastocysts nourished by trophectoderm cells, in comparison to euploid embryos, aneuploid embryos exhibited significant extensions in tPNa, S3, tSC, tM, tSB, and tB (p < 0.05), with a simultaneous significant reduction in CC2 time (p < 0.05). After adjusting for age and body mass index through logistic regression analysis, late morphokinetic parameters, namely tM (OR 0.96; 95% CI 0.93–0.99), tSB (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.90–0.97), and tB (OR 0.93; 95% CI 0.90–0.97), emerged as independent risk factors influencing the development of embryos into high-quality blastocysts. S3 (< 12.01 h), t8 (< 62.48 h), and tPB2 (< 3.36 h) were potential predictors of a successful clinical pregnancy after blastocyst transfer.

Conclusion

Morphokinetic parameters showed correlations with blastocyst quality, chromosomal status, and clinical pregnancy outcomes post-transfer, making them effective predictors for clinical results. Embryos with relatively rapid development tended to exhibit better blastocyst quality, chromosomal ploidy, and improved clinical pregnancy outcomes. The late morphokinetic parameter, S3, demonstrated a strong predictive effect on blastocyst quality, chromosomal ploidy, and clinical pregnancy outcomes.

Keywords: Time-lapse monitoring, Preimplantation genetic testing, Morphokinetic parameters, Embryo quality, Ploidy, Clinical pregnancy

Introduction

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) has been associated with significant advancements over the last four decades. Progress in both clinical and embryonic laboratory techniques has significantly enhanced the success rates of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfers (IVF-ET). Nevertheless, a crucial challenge persists in the field of ART, i.e., the effective selection of the embryo with the highest developmental potential for transfer [8]. Embryo selection methods currently employ two primary strategies: invasive and non-invasive. Non-invasive approaches encompass morphological grading, time-lapse monitoring (TLM) among others. Invasive strategies involve the biopsy of trophectoderm (TE) cells for chromosomal analysis. To date, morphological observation remains the most prevalent method for embryologists to monitor embryo development and identify optimal embryos for transfer [15]. However, chromosomal abnormalities in embryos stand out as a prominent factor influencing the success rates of IVF [28, 29]. In treatments such as in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection-embryo transfers (IVF/ICSI-ET) in the absence of PGT, the genetic status of embryos remains unpredictable before transfer. Even morphologically normal embryos may exhibit numerical or structural chromosomal abnormalities, leading to issues such as recurrent pregnancy loss or post-transfer birth defects [13]. The application of high-resolution sequencing technology by Friedenthal et al. [14] for preimplantation embryo genetic status detection, followed by the selective transfer of euploid embryos, has notably improved outcomes in single embryo transfer (SET) cycles. However, reports indicate that invasive biopsies at the cleavage stage are linked to an elevated risk of low birth weight and preterm birth; and patients undergoing a TE biopsy for chromosomal analysis may face an increased risk of preterm birth and birth defects [3].

TLM stands out as an innovative non-invasive technology offering dynamic observation of embryo morphology across various developmental stages. It records time parameters at each developmental phase, providing a foundation for predicting embryo ploidy [32]. Moreover, TLM minimizes embryo exposure to external environmental factors outside the incubator, mitigating inaccuracies associated with static morphological assessments [19, 22]. The correlation between differences in morphokinetic parameters and chromosomal ploidy proves instrumental in selecting embryos with developmental potential for traditional IVF/ICSI treatments [21]. Beyond its predictive capabilities, TLM enhances traditional morphological evaluations, thereby refining embryo selection processes and subsequently improving clinical pregnancy outcomes without needing to invasively test embryos. The conventional blastocyst grading system involves assessing blastocyst cavity expansion, inner cell mass (ICM), and TE cell condition [15]. Earlier reports have identified correlations between morphokinetic parameters and the formation and development of blastocysts [4, 16]. Furthermore, morphokinetic parameters serve as robust predictors for live birth rates following both fresh and frozen-thawed embryo transfers (FET) [1, 15]. Kirkegaard et al. [20] conducted a prospective study involving 571 ICSI-fertilized embryos, highlighting the ability of morphokinetic parameters within the first 48 h to predict the formation of high-quality blastocysts. Additionally, Dahl et al. [10] delved into spatial transcriptomic research on early human embryo development, revealing a sequential process involving maternal gene decline during early development (from the two-cell to the four-cell stage) followed by the activation of the major zygotic genome (from the four-cell to the eight-cell stage). This establishes a theoretical framework, emphasizing the crucial role of early morphokinetic parameters in influencing embryo developmental potential [10].

Nonetheless, skepticism persists among certain researchers regarding the practical value of TLM. Reignier et al. [25] argued that no single morphokinetic parameter or combination thereof was consistently identified as a reliable predictor for the ploidy status of embryos. This inconsistency may be attributed to variations in study design, individual patient differences, the timing of embryo biopsies, statistical methodologies, and resulting analysis [25]. Furthermore, placing sole reliance on morphological analysis does not guarantee the identification of chromosomally normal embryos. In an observational study analyzing 500 transplanted embryos, Alfarawati et al. [2] found that 48% of high-quality blastocysts were still aneuploid, while 37% of low-quality blastocysts were euploid. Additionally, Capalbo et al. [6], through the analysis of morphokinetic parameters of 956 blastocysts from 213 patients, concluded that blastocyst grading alone was insufficient to enhance the selection of euploid embryos. In our study, we systematically investigated the morphokinetic parameters of a total of 1011 blastocysts. We explored their correlations with blastocyst quality, chromosomal ploidy, and clinical pregnancy outcomes post-transfer. Based on our results, multiple key morphokinetic parameters relevant to embryo selection were identified and proposed as reference points.

Materials and methods

Research participants

This study conducted a retrospective analysis of the clinical data from 227 patients who underwent preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) for ART at the Reproductive Medicine Center of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University from March to November 2022. The inclusion criteria for PGT diagnosis adhered to the “Expert Consensus on Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis/Screening in China.” Eligibility encompassed couples or individuals with a genetic disease or carrier status, repeated implantation failures, unexplained recurrent miscarriages, or advanced maternal age (age ≥ 38 years). Patients with conditions such as uterine malformations, adenomyosis, or uterine fibroids, were excluded. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (reference number: 2018-KY-66).

Controlled ovulation induction and oocyte Retrieval

Standard protocols for ovarian stimulation and oocyte retrieval were followed. Recombinant hCG (250 mg) (Serono Ltd., Switzerland) was administered when a single follicle reached a diameter of ≥ 20 mm, three follicles reached a diameter of ≥ 17 mm, or two-thirds of the follicles reached a diameter of ≥ 16 mm. Oocyte retrieval was conducted under vaginal ultrasound guidance to collect cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs). Harvested COCs were immediately placed in G-IVF Plus medium (Vitrolife, Gothenburg, Sweden) and cultured at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator for 1–2 h. Hyaluronidase (Vitrolife, Sweden) was used to remove surrounding cumulus cells, followed by using a 150 μm-diameter needle (Sunlight, FL, USA) to further eliminate cumulus cells. Denuded oocytes were transferred to G-IVF Plus for continued cultivation for an additional 1–2 h.

Sperm Collection and ICSI

The collected semen sample underwent initial density gradient centrifugation (90% and 45%) using Spermgrad (Vitrolife, Sweden), followed by centrifugation and washing with G-IVF Plus to isolate sperm. For patients with obstructive azoospermia, sperm were collected through epididymal puncture, subjected to density gradient centrifugation, and washed with G-IVF Plus. In the case of testicular sperm extraction patients, a 1 ml needle was used to tear and mince the obtained testicular tissue in a G-IVF Plus solution, releasing the sperm, which were then directly collected after centrifugation, following instructions from a previous study [6]. All patients undergoing PGT received ICSI, performed under an inverted microscope (TE 2000-U, Nikon, Japan). The fertilization status of oocytes was observed using the TLM system. Normally fertilized zygotes display two distinct pronuclei (2PN). The 2PN rate (%) was calculated by dividing the number of 2PN zygotes by the number of mature metaphase II (MII) oocytes and multiplying by 100%.

Embryo culture

Fertilized zygotes after ICSI were transferred to a specialized 12-well culture dish (EmbryoSlide® culture dish, Vitrolife, Denmark) containing a G-1 Plus (Vitrolife, Sweden) culture medium and cultured until the third day (D3). Subsequently, D3 embryos were transferred to another specialized culture dish containing G-2 Plus (Vitrolife, Sweden) medium where they continued to be cultured until the fifth (D5) or sixth day (D6). Blastocysts were subsequently graded according to the Gardner grading system, with the blastocyst cavity size and hatching stage rated from 1 to 6. Blastocysts of stage 3 or higher were further classified as grade A, B, or C based on the number and compactness of ICM and TE cells [15]. High-quality blastocysts were assigned AA, AB, or BB grades, while low-quality blastocysts were categorized as AC, BC, CA, CB or CC. All embryos were cultured in a time-lapse incubator (EmbryoScope ES-D, Vitrolife, Denmark) under conditions of 37 °C, 6% CO2, and 5% O2.

TE Biopsy and chromosomal analysis

On the fourth day of embryonic development (D4) in the afternoon, the laser-assisted hatching system (ZERTAS-tk, Hamilton Thorne Biosciences, Beverly, Massachusetts, USA) was used to create perforations on the zona pellucida (ZP) away from the ICM, promoting outward growth of the TE cells. A TE biopsy was conducted on D5 or D6 when the blastocysts exhibited significant expansion and protrusion of the blastocyst cavity. Under an inverted microscope, a biopsy needle with a 25 μm inner diameter (Origio, VA, USA) was employed to extract 3–5 TE cells for subsequent chromosomal analysis [33]. Fragment gain or loss of individual chromosomes was defined as changes in segments with a size of 10 MB or more.

TLM and morphokinetic parameters

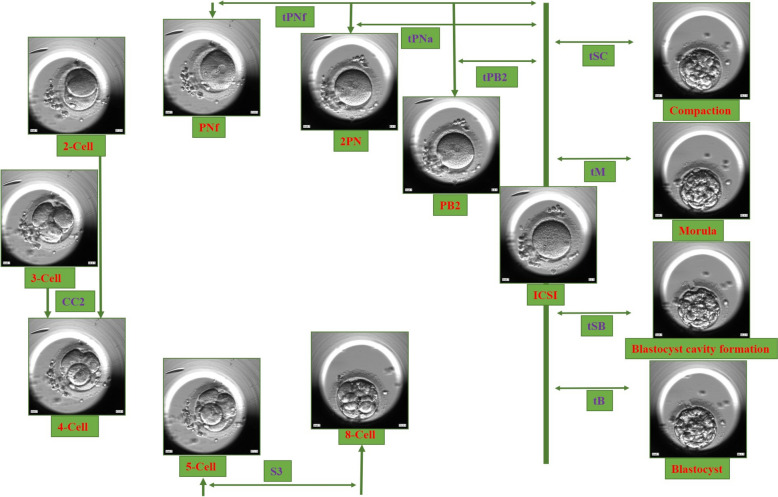

The time-lapse incubator was set to capture images every 10 min, effectively monitoring the entire embryonic development process. Utilizing the EmbryoViewer software (UnisenseFertilitech, Denmark), the morphokinetic parameters were recorded. The included early morphokinetic parameters were as follows: tPB2 represented the time from fertilization initiation to the second polar body extrusion; tPNa and tPNf represented the time from fertilization initiation to the appearance and disappearance of pronuclei, respectively; t2-t9 represented the time from fertilization initiation to the development of 2-cell to 9-cell embryos; CC2 represented the interval between the first and second cleavage, i.e., the duration of the 2-cell embryo; CC3 represented the interval between the second and third cleavage; S2 represented the duration of the second cleavage, i.e., the duration of the 3-cell embryo; S3 represented the duration of the third cleavage; tSC represented the time from fertilization initiation to the initiation of blastomere compaction; tM represented the time from fertilization initiation to the formation of morula; tSB represented the time from fertilization initiation to the initiation of blastocyst cavity appearance; and tB represented the time for the blastocyst cavity to fill the entire ZP (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Timing of human early embryonic development. Embryonic developmental events PB2, 2PN, PNf, 2-Cell, 3-Cell, 4-Cell, 5-Cell, 8-Cell, tPB2, tPNa, tPNf, CC2, S3, tSC, tM, tSB, tB, Compaction, Morula, Blastocyst cavity formation, Blastocyst are shown in Graphic. We determined the precise times and measured them within hours of ICSI

Clinical outcomes in frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles

Single blastocyst transfers were carried out in frozen-thawed cycles. Clinical pregnancy was confirmed when original cardiac activity and a gestational sac were observed on the 35th day post-transfer through ultrasound. The clinical pregnancy rate (%) was calculated as the number of clinical pregnancies divided by the total number of embryo transfer cycles, multiplied by 100%.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis employed SPSS 26.0 software. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test assessed the normality of continuous variables. Normally distributed data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (x ± s), and independent sample t-tests were used for between-group comparisons. A multiple factor analysis was performed using logistic regression models. Count data were expressed as rates (%), and between-group comparisons were assessed using the χ2 test. p values < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. GraphPad Prism 9 software was utilized for data visualization.

Results

General Information of Research Participants

This study conducted a retrospective analysis involving 1011 blastocysts from 227 patients undergoing PGT, focusing on the relationship between early morphokinetic parameters, embryo quality, chromosomal status, and clinical outcome (Table 1). The average age of the included patients was 31.8 ± 4.9 years, with a baseline body mass index (BMI) of 23.29 ± 3.19 kg/m2 and an Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) level of 3.62 ± 2.57 ng/ml. Baseline levels of FSH, LH, E2, P, PRL, and Testosterone (T) were within normal ranges. Additionally, the average number of retrieved oocytes was 14.96 ± 6.42, with an 82.01% MII oocyte rate and a 77.20% 2PN fertilization rate.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of PGT cycles

| Parameter | Mean ± SD/Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| No. of cycles | 227 |

| Age (year) | 31.8 ± 4.90 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.29 ± 3.19 |

| AMH (ng/ml) | 3.62 ± 2.57 |

| Basal FSH (mIU/ml) | 6.41 ± 1.98 |

| Basal LH (mIU/ml) | 5.60 ± 4.44 |

| Basal E2 (pg/ml) | 43.54 ± 25.07 |

| Basal P (ng/ml) | 1.31 ± 3.86 |

| Basal PRL (ng/ml) | 24.40 ± 36.13 |

| Basal T (ng/ml) | 0.76 ± 4.41 |

| Mean oocytes retrieved | 14.96 ± 6.42 |

| MII rate (%) | 82.01%(2772/3380) |

| 2PN rate (%) | 77.20%(2140/2772) |

Note: BMI body mass index, AMH antimullerian hormone, FSH follicle-stimulating hormone, LH luteinising hormone, E2 oestradiol, P progesterone, PRL prolactin, T testosterone, The MII rate (%) represents the total number of mature oocytes/total number of all oocytes obtained × 100%; the 2PN rate (%) represents the total number of 2PN zygotes/total number of MII oocytes × 100%

Retrospective analysis of key morphokinetic parameters for blastocyst quality

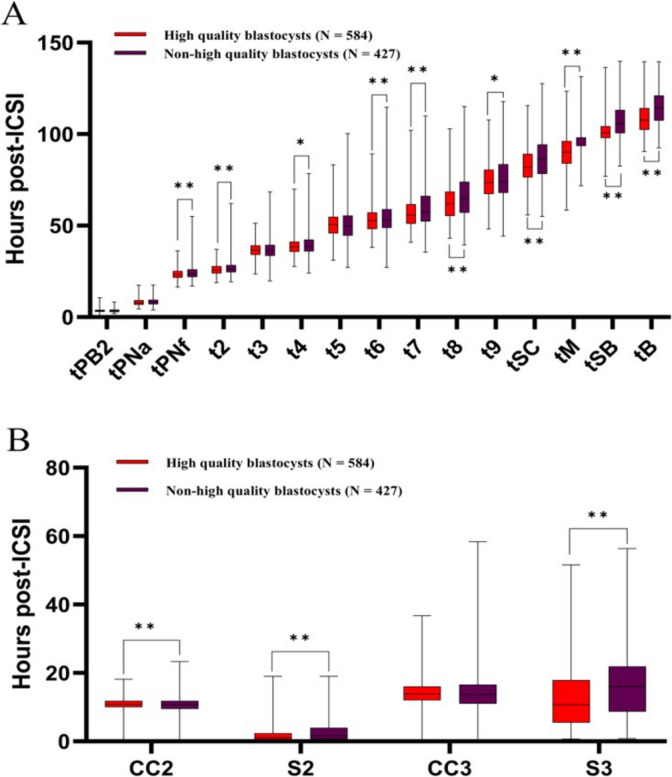

To identify factors influencing blastocyst quality, we categorized blastocysts into two groups using the Gardner grading system, namely high-quality blastocysts (584, 57.8%) and Non-high quality blastocysts (427, 42.2%). We then delved into the morphokinetic parameters between these groups (Fig. 2). The findings indicated that, high-quality blastocysts exhibited significantly shortened early morphokinetic parameters in comparison to Non-high quality blastocysts, including tPNf (23.5 ± 2.8 h vs. 24.2 ± 3.5 h), t2 (26.1 ± 2.9 h vs. 26.8 ± 3.8 h), t4 (38.7 ± 4.7 h vs. 39.5 ± 6.1 h), t6 (53.5 ± 7.0 h vs. 55.3 ± 10.4 h), t7 (57.3 ± 8.8 h vs. 60.4 ± 11.9 h), t8 (63.5 ± 10.6 h vs. 66.8 ± 13.5 h), t9 (74.3 ± 10.2 h vs. 76.1 ± 12.9 h), and S2 (2.2 ± 3.1 h vs. 2.9 ± 3.9 h), as well as late morphokinetic parameters, including S3 (12.9 ± 8.6 h vs. 16.6 ± 9.8 h), tSC (83.3 ± 9.5 h vs. 86.9 ± 11.4 h), tM (90.7 ± 9.2 h vs. 95.8 ± 10.6 h), tSB (102.1 ± 8.6 h vs. 107.2 ± 10.1 h), and tB (108.9 ± 8.8 h vs. 114.8 ± 10.0 h) (p < 0.05). High-quality blastocysts also displayed significantly longer CC2 (10.5 ± 2.9 h vs. 9.3 ± 3.7 h) (p < 0.05), while tPB2, tPNa, t3, t5and CC3 were not significantly different in the two groups (p > 0.05). These findings suggest that early (tPNf, t2, t4, t6, t7, t8, t9, and CC2, S2) and late morphokinetic parameters (S3, tSC, tM, tSB, and tB) held reference value in predicting whether the embryos could or could not progress into high-quality blastocysts.

Fig. 2.

Comparative analysis of kinetic parameters of early embryonic development of high-quality blastocysts and non-high quality blastocysts. Box plots indicate the mean, standard deviation, and time to minimum and maximum (A) and the duration of the associated developmental events (B) of the kinetic parameters of embryo development. Red and purple colors indicate high-quality blastocysts and non-high quality blastocysts, respectively. * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01, and p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between the two groups

Logistic regression analysis of the relationship between morphokinetic parameters and blastocyst quality

The study further incorpo.

rated age and BMI to construct a multifactor logistic regression equation for the correlation analysis between morphokinetic parameters and blastocyst quality (Table 2). The results indicated that a significant reduction in the morphokinetic parameter, tM, significantly increased the probability of embryonic development into high-quality blastocysts (OR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.93–0.99, p = 0.002). Similarly, a decrease in tSB significantly increased the probability of embryonic development into high-quality blastocysts (OR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.90–0.97, p = 0.001). Moreover, a decrease in the kinetic parameter, tB, also significantly raised the probability of high-quality blastocyst formation (OR: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.90–0.97, p = 0.001). These results suggested that embryos with shortened tM, tSB, and tB parameters were more likely to develop into high-quality blastocysts.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis for the association between the blastocyst quality and embryonic developmental morphokinetic parameters

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Significance | OR | 95% C.I. for OR | Significance | OR | 95% C.I. for OR | ||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age | 0.154 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 1.02 | 0.141 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 1.01 |

| BMI | 0.974 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.09 | 0.888 | 1.01 | 0.92 | 1.10 |

| tM | 0.001 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.002 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.99 |

| tSB | 0.001 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.001 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.97 |

| tB | 0.001 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.001 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.97 |

Model 1: Crude model.

Model 2: Adjusted for Age, BMI.

Note: BMI Body mass index, p < 0.05 indicates significant differences

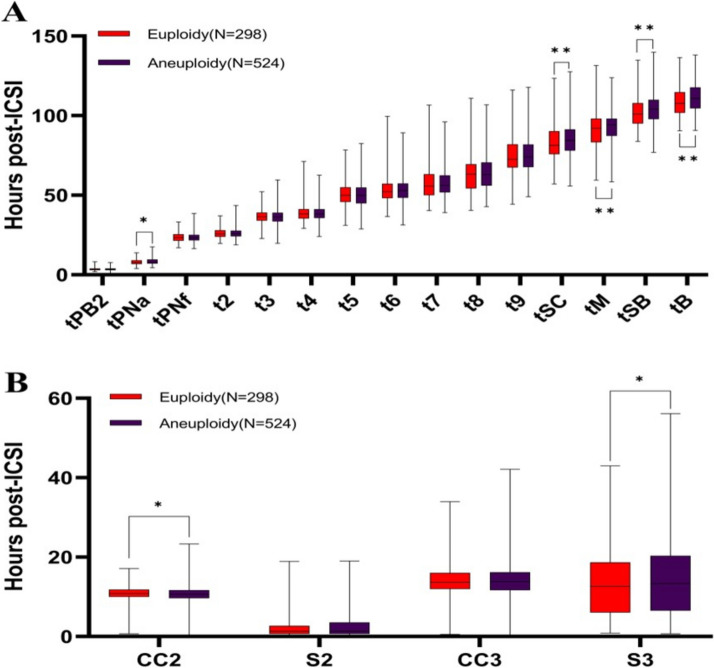

Exploring key morphokinetic parameters influencing embryonic ploidy through chromosomal analysis results

To investigate the correlation between morphokinetic parameters and chromosomal status, we conducted an analysis of the morphokinetic parameters of 822 blastocysts with evident chromosomal signals. This included 298 blastocysts with normal chromosomal signals (euploid, 36.4%) and 524 blastocysts with abnormal chromosomal signals (aneuploid, 63.6%) (Fig. 3). The parameters considered comprised 14 time points (tPB2, tPNf, t2, t3, t4, t5, t6, t7, t8, t9, tSC, tM, tSB, and tB) and 4-time intervals (CC2, S2, CC3, and S3). The findings revealed that, in comparison to euploid blastocysts, aneuploid blastocysts exhibited significantly prolonged kinetic parameters, including tPNa (8.5 ± 2.2 vs. 8.1 ± 1.8 h), S3 (14.71 ± 9.7 vs. 13.3 ± 8.6 h), tSC (85.1 ± 10.2 vs. 83.1 ± 10.2 h), tM (93.1 ± 9.7 vs. 90.7 ± 10.2 h), tSB (104.4 ± 9.0 vs. 102.1 ± 9.7 h), and tB (111.8 ± 9.4 vs. 108.9 ± 9.7 h) (p < 0.05). Conversely, the CC2 value for euploid blastocysts was significantly higher than that for aneuploid blastocysts (10.5 ± 2.6 vs. 10.1 ± 3.3 h) (p < 0.05). These results suggested that the morphokinetic parameters, tPNa, CC2, S3, tSC, tM, tSB, and tB, held potential value in predicting blastocyst ploidy.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of parameters analysed for embryonic developmental dynamics of blastocyst chromosome conditions. Box plots represent the mean, standard deviation and time to minimum and maximum (A) and duration of relevant developmental events (B) of different embryonic developmental morphokinetic parameters between aneuploid and aneuploid blastocysts, with red and purple boxes indicating blastocysts with normal chromosomes (aneuploid) and abnormal chromosomes (aneuploid), respectively. * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01, and p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference

Retrospective analysis of the clinical application value of morphokinetic parameters in clinical pregnancy outcomes

To investigate the clinical application value of morphokinetic parameters in single blastocyst transfer, we divided 154 transplanted blastocysts into a clinical pregnancy group and a non-clinical pregnancy group. Subsequently, we compared and analyzed the differences in morphokinetic parameters between the two groups. The results revealed that tPB2 (3.36 ± 0.83 vs. 3.88 ± 1.11 h), t8 (61.54 ± 9.39 vs. 65.77 ± 13.61 h), and S3 (11.41 ± 7.34 vs. 14.71 ± 8.26 h) of blastocysts in the clinical pregnancy group were significantly shorter than those in the non-clinical pregnancy group (p < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences between the two groups in tPNa, tPNf, t2, t3, t4, t5, t6, t7, t9, tSC, tM, tSB, tB, CC2, S2, and CC3 (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

The comparison of different embryonic development morphokinetic parameters between the blastocysts with clinical and non-clinical pregnancy

| Parameter | Clinical pregnancy(N = 96) | Non-clinical pregnancy (N = 58) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| tPB2 | 3.36 ± 0.83 | 3.88 ± 1.11 | 0.03 |

| tPNa | 8.14 ± 1.79 | 7.89 ± 1.49 | 0.40 |

| tPNf | 23.41 ± 2.81 | 23.49 ± 3.26 | 0.88 |

| t2 | 26.00 ± 2.99 | 26.31 ± 3.68 | 0.58 |

| t3 | 36.42 ± 3.85 | 36.48 ± 5.11 | 0.94 |

| t4 | 38.39 ± 3.96 | 39.42 ± 6.01 | 0.21 |

| t5 | 50.13 ± 6.49 | 51.06 ± 9.08 | 0.47 |

| t6 | 52.93 ± 6.22 | 54.63 ± 9.15 | 0.18 |

| t7 | 56.1 ± 7.97 | 59.17 ± 11.44 | 0.06 |

| t8 | 61.54 ± 9.39 | 65.77 ± 13.61 | 0.03 |

| t9 | 72.75 ± 10.19 | 74.17 ± 14.04 | 0.48 |

| tSC | 82.24 ± 9.28 | 83.61 ± 10.98 | 0.43 |

| tM | 90.23 ± 9.08 | 91.45 ± 10.5 | 0.47 |

| tSB | 101.64 ± 8.31 | 102.59 ± 9.94 | 0.54 |

| tB | 107.94 ± 8.16 | 109.51 ± 9.76 | 0.30 |

| CC2 | 10.43 ± 2.48 | 10.17 ± 3.04 | 0.59 |

| S2 | 1.97 ± 2.72 | 2.94 ± 3.97 | 0.08 |

| CC3 | 13.71 ± 4.6 | 14.58 ± 5.65 | 0.32 |

| S3 | 11.41 ± 7.34 | 14.71 ± 8.26 | 0.01 |

Note: Data are expressed as Mean ± SD, p < 0.05 indicates significant differences

Next, we divided the significantly different parameters, tPB2, t8, and S3, into quartiles (Q1-Q4, each accounting for 25%) between the two groups, aiming to identify morphokinetic parameters that could predict a higher probability of clinical pregnancy after embryo transfer. The results showed that, for the three evaluated morphokinetic parameters, blastocysts in the Q1 + Q2 group exhibited higher clinical pregnancy rates compared to Q3 + Q4 group (Table 4). Compared to the Q3 + Q4 group, the clinical pregnancy rate was 22% higher for blastocysts with tPB2 in the Q1 + Q2 group. Alternatively, for the parameter S3, the clinical pregnancy rate was 18.4% higher in the Q1 + Q2 group compared to Q3 + Q4 group. Lastly, regarding t8, the clinical pregnancy rate was 16% higher in the Q1 + Q2 group compared to Q3 + Q4 group. Through quartile grouping analysis, we further analyzed the threshold values of these three morphokinetic parameters. The results showed that blastocysts with a tPB2 of less than 3.36 h had a significantly higher clinical pregnancy rate than those with a tPB2 that was greater than 3.36 h (61.0% vs. 39.0%, p < 0.05). Blastocysts with a t8 of less than 62.48 h had a significantly higher clinical pregnancy rate than those with a t8 that was greater than 62.48 h (58.1% vs. 41.9%, p < 0.05). Blastocysts with a S3 of less than 12.01 h had a significantly higher clinical pregnancy rate than those with a S3 that was greater than 12.01 h (59.1% vs. 40.9%, p < 0.01) (Fig. 4). These results suggested that the morphokinetic parameters tPB2, t8, and S3 were effective predictors of clinical pregnancy outcome.

Table 4.

Proportion of clinical pregnancy rates in different quartile groups analyzing morphokinetic parameters

| Parameter | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limit (h) | CPR (%) | Limit (h) | CPR(%) | Limit (h) | CPR(%) | Limit (h) | CPR (%) | |

| tPB2 | <2.85 | 31.7 | 2.85–3.36 | 29.3 | 3.36–3.98 | 19.5 | >3.98 | 19.5 |

| t8 | <55.38 | 24.7 | 55.38–62.48 | 33.3 | 62.48–67.62 | 23.7 | >67.62 | 18.3 |

| S3 | <5.92 | 31.2 | 5.92–12.01 | 28.1 | 12.01–17.51 | 21.5 | >17.51 | 19.4 |

Note: CPR clinical pregnancy rate

Fig. 4.

Thresholds for embryo developmental morphokinetic parameters and clinical pregnancy outcomes. Parameter thresholds were mainly based on the values of embryonic developmental morphokinetic parameters with higher pregnancy rates obtained by quartile grouping. Comparisons between groups were statistically analysed using the chi-square test, * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01, and p < 0.05 denotes a statistically significant difference

Discussion

As infertility rates continue to rise, an increasing number of individuals are turning to ART to conceive. Consequently, there is a substantial demand for ART services. Currently, one of the primary challenges in the field of ART is the selection of embryos. The application of TLM in ART addresses the limitations of traditional assessment methods. It effectively captures a series of dynamic changes in the development of fertilized eggs into blastocysts, including the formation and disappearance of pronuclei, the cleavage process, and the presence of abnormalities. These changes have been proven to be closely associated with embryo quality and developmental potential [18].

A previous study has reported a correlation between morphokinetic parameters and the formation rate of high-quality blastocysts [30]. Cruz et al. analyzed data from 834 morphokinetic parameters and found a correlation between blastocyst formation rate, blastocyst quality, and early morphokinetic parameters [9]. A study by Hashimoto [17] et al. suggested that, compared to low-quality blastocysts, high-quality blastocysts had shorter time intervals between the three to four-cell and five to eight-cell stages. Similarly, Desai et al. analyzed the morphokinetic parameters of 648 embryos and suggested a strong correlation between kinetic parameters and the formation of high-quality blastocysts. High-quality blastocysts exhibited different values for tPNf, t2, t4, t8, S1, S2, S3, and CC2 (t3-t2) compared to embryos that did not form blastocysts or formed low-quality blastocysts [12]. In our study, we compared the growth rate between high-quality blastocysts and low-quality blastocysts. We observed that low-quality blastocysts not only demonstrated significant delays in the early stages (tPNf, t2, t4, t6, t7, t8, t9) but also exhibited noteworthy delays in synchronicity indicators during the second and third cleavage (s2 and s3), and in the period of blastocyst formation (tM, tSB, and tB). Furthermore, with the prolongation of time, embryos with delayed development demonstrated poorer developmental potential.

It is noteworthy that our experiment aligns with the findings of Desai et al. [12]. We observed a significant delay in CC2 (t3-t2) in both euploid blastocysts and high-quality blastocysts, consistent with their research [12]. However, based on our prior study on chromatin analysis during early human embryo development, the expressions of “maternal transcription factors” such as CTCF, KLF, and OTX2, started diminishing during the two-cell to four-cell stages and beyond (i.e., ZGA) [31]. Consequently, we propose that in early human embryo development, CC2 (t3-t2) may be correlated with the expressions of “maternal transcription factors”, suggesting that embryos with prolonged expressions of these factors have a higher potential to develop into high-quality and euploid embryos. Moreover, the timing of S3 (t8-t5) in the early development of human embryos aligns with the activation of the “major zygotic genome”. This may indicate that the S3 (t8-t5) stage serves as the activation phase for the “major zygotic genome” and plays a pivotal role in early embryo development [31]. According to our research results, S3 is significantly shortened in high-quality blastocysts and in blastocysts leading to clinical pregnancy (discussed later). Consequently, we propose that a shorter activation time for the “major zygotic genome” within the S3 parameter, corresponds with embryos having a greater potential to develop into high-quality blastocysts, and with successful clinical pregnancies.

Embryo ploidy has consistently been recognized as a critical factor influencing successful implantation and pregnancy [7]. With the advent of TLM, morphokinetic parameters have been harnessed to predict the chromosomal status of blastocysts. In a study by Minasi et al. [23], which analyzed 928 blastocysts, the chromosomal status was assessed alongside standard morphological evaluation and morphokinetic parameters. The findings suggested that euploid blastocysts, when compared to the aneuploid counterparts, exhibited a higher proportion of high-quality ICM and TE. Additionally, they demonstrated shorter times for blastocyst formation, expansion, and hatching [23]. Another study by Campbell et al. [5] found that late kinetic parameters (tSC and tB) were significantly prolonged in aneuploid embryos compared to euploid embryos. In our study, both early (tPNa and S3) and late morphokinetic parameters (tSC, tM, tSB, tB) for chromosomally abnormal blastocysts were prolonged, compared to euploid embryos. These research findings suggest that embryos with chromosomal abnormalities exhibit slower development and diminished developmental potential. This may be attributed to errors in the segregation and independent assortment of parental genomes, disrupting the normal pattern of embryo gene expression [11, 25]. Therefore, we recommend prioritizing embryos with shorter early (tPNa and S3) and late morphokinetic parameters (tSC, tM, tSB, tB) for transfer, as this approach may assist in identifying euploid embryos.

In practice, studies have reported variations in the proportions of euploidy, mosaicism, and aneuploidy rates among different fertility centers. These differences may be linked to factors such as patient population, female age, ovarian stimulation protocols, oocyte quantity, in vitro oocyte maturation, and variations in culture medium components [24, 26]. In our investigation, the analysis of chromosomal ploidy rates in 822 biopsy-derived blastocysts aligned with the results reported by Lee et al. [21] for 694 blastocysts (36.3% vs. 37.5%). However, Munne et al. [24], studying 13,595 blastocysts from young women (< 35 years) across 42 centers, highlighted significant differences in ploidy rates among these centers. They suggested that some of these differences were iatrogenic and closely related to hormonal stimulation or specific cultural conditions [24]. Consequently, both clinical protocols and laboratory procedures may influence the ploidy rates of biopsy-derived blastocysts. Therefore, the application of the obtained embryonic development morphokinetic parameters in different medical centers has certain limitations. More centers are need to conduct such research, or multi-center studies, in order to obtain more universal results and provide reference for embryo selection in clinical practice.

In a study exploring the correlation between early morphokinetic parameters and clinical outcomes, it was determined that parameters t5 and CC2 held the highest predictive value for implantation and live birth following IVF [27]. In terms of clinical outcome, PGT cycles were selected for transferring embryos with normal chromosomal signals, and it was found that there was no significant difference in clinical pregnancy outcome between good quality blastocysts and non-good quality blastocysts (66.10% vs. 60.00%, p = 0.644). Therefore, this difference in clinical pregnancy outcome stems more from the difference between embryo chromosome ploidy and with embryo development morphokinetic parameters. Moreover, our current investigation revealed significant disparities in the developmental timelines of embryos between the clinical pregnancy group and the non-pregnancy group after the transfer of a single blastocyst. Furthermore, our findings indicated optimal time intervals for kinetic parameters representing both early and late embryonic development, where tPB2 < 3.36 h (p < 0.05), S3 < 12.01 h (p < 0.05), or t8 < 62.48 h (p < 0.01) were all indicative of significantly heightened chances of a successful clinical pregnancy.

Conclusion

This study established a correlation between morphokinetic parameters and blastocyst quality, chromosomal status, and clinical pregnancy outcomes following blastocyst transfer, suggesting these parameters as reliable predictors for clinical outcomes. Moreover, embryos exhibiting faster development demonstrated superior blastocyst quality, chromosomal ploidy, and favorable clinical outcomes. The late morphokinetic parameter S3 emerged as a robust predictor for blastocyst quality, chromosomal ploidy, and clinical outcome. Integrating TLM application with a standard morphological assessment significantly enhanced the precision of embryo selection. The results of this study provide a scientific foundation for employing TLM in selecting single blastocysts with heightened developmental potential, highlighting its considerable promise in clinical applications.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients from the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University and the staff in the Center for Reproductive Medicine.

Abbreviations

- ART

Assisted reproductive technology

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- COC

Cumulus-oocyte complexes

- ICM

Inner cell mass

- LBR

Live birth rates

- OR

Odds ratio

- PGT

Preimplantation genetic testing

- RPL

Recurrent pregnancy loss

- TESE

Testicular sperm extraction

- TLM

Time-lapse monitoring

Authors’ contributions

RJ: data collection, data analysis and writing the manuscript. GD-Y: concept, design and supervise the study. GY, HH-W, and JN-F: data collection and data analysis. JY-H, TW-Z, YK,ZT-W, XJ-H, LQ, NS, WY-S, and HX-J: Collection of data. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1904138), Provincial and Ministerial co-construction project of Henan Medical Science and Technology Program (SBGJ202102098 & SBGJ202102104), and Zhengzhou University School of Medical Sciences Clinical First-class Subject Talent Cultivation Project (to Guidong Yao).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Guidong Yao, upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for date use prior to enrollment. This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (reference number: 2018-KY-66).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ran Jiang, Guang Yang, Huihui Wang and Junnan Fang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Ahlstrom A, et al. Prediction of live birth in frozen-thawed single blastocyst transfer cycles by pre-freeze and post-thaw morphology. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(5):1199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfarawati S, et al. The relationship between blastocyst morphology, chromosomal abnormality, and embryo gender. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(2):520–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alteri A, et al. Obstetric, neonatal, and child health outcomes following embryo biopsy for preimplantation genetic testing. Hum Reprod Update. 2023;29(3):291–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes J, et al. A non-invasive artificial intelligence approach for the prediction of human blastocyst ploidy: a retrospective model development and validation study. Lancet Digit Health. 2023;5(1):e28-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell A, et al. Modelling a risk classification of aneuploidy in human embryos using non-invasive morphokinetics. Reprod Biomed Online. 2013;26(5):477–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capalbo A, et al. Correlation between standard blastocyst morphology, euploidy and implantation: an observational study in two centers involving 956 screened blastocysts. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(6):1173–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Chavli EA, et al. Single-cell DNA sequencing reveals a high incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in human blastocysts. J Clin Investig. 2024;134(6): e174483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chronopoulou E, et al. IVF culture media: past, present and future. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(1):39–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruz M, et al. Timing of cell division in human cleavage-stage embryos is linked with blastocyst formation and quality. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;25(4):371–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahl JA, et al. Broad histone H3K4me3 domains in mouse oocytes modulate maternal-to-zygotic transition. Nature. 2016;537(7621):548–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Coster T, et al. Parental genomes segregate into distinct blastomeres during multipolar zygotic divisions leading to mixoploid and chimeric blastocysts. Genome Biol. 2022;23(1):201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desai N, et al. Analysis of embryo morphokinetics, multinucleation and cleavage anomalies using continuous time-lapse monitoring in blastocyst transfer cycles. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2014;12:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai N, et al. Delayed blastulation, multinucleation, and expansion grade are independently associated with live-birth rates in frozen blastocyst transfer cycles. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(6):1370–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedenthal J, et al. Next generation sequencing for preimplantation genetic screening improves pregnancy outcomes compared with array comparative genomic hybridization in single thawed euploid embryo transfer cycles. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(4):627–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner DK, et al. Blastocyst score affects implantation and pregnancy outcome: towards a single blastocyst transfer. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(6):1155–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giménez C, et al. Time-lapse imaging: morphokinetic analysis of in vitro fertilization outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2023;120(2):218–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashimoto S, et al. Selection of high-potential embryos by culture in poly(dimethylsiloxane) microwells and time-lapse imaging. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(2):332–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin L, et al. Incidence, dynamics and recurrences of reverse cleavage in aneuploid, mosaic and euploid blastocysts, and its relationship with embryo quality. J Ovarian Res. 2022;15(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaser DJ, et al. Clinical outcomes following selection of human preimplantation embryos with time-lapse monitoring: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):617–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirkegaard K, et al. Time-lapse parameters as predictors of blastocyst development and pregnancy outcome in embryos from good prognosis patients: a prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(10):2643–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CI, et al. Embryo morphokinetics is potentially associated with clinical outcomes of single-embryo transfers in preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy cycles. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;39(4):569–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meseguer M, et al. The use of morphokinetics as a predictor of embryo implantation. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(10):2658–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minasi MG, et al. Correlation between aneuploidy, standard morphology evaluation and morphokinetic development in 1730 biopsied blastocysts: a consecutive case series study. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(10):2245–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munne S, et al. Euploidy rates in donor egg cycles significantly differ between fertility centers. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(4):743–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reignier A, et al. Can time-lapse parameters predict embryo ploidy? A systematic review. Reprod Biomed Online. 2018;36(4):380–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sachdev NM, et al. Diagnosis and clinical management of embryonic mosaicism. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(1):6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sayed S, et al. Time-lapse imaging derived morphokinetic variables reveal association with implantation and live birth following in vitro fertilization: a retrospective study using data from transferred human embryos. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0242377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott RJ, et al. Comprehensive chromosome screening is highly predictive of the reproductive potential of human embryos: a prospective, blinded, nonselection study. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(4):870–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Werner M, et al. Characteristics of chromosomal abnormalities diagnosed after spontaneous abortions in an infertile population. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29(8):817–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong CC, et al. Non-invasive imaging of human embryos before embryonic genome activation predicts development to the blastocyst stage. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(10):1115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu J, et al. Chromatin analysis in human early development reveals epigenetic transition during ZGA. Nat (London). 2018;557(7704):256–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Q, et al. Analysis of maturation dynamics and developmental competence of in vitro matured oocytes under time-lapse monitoring. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2021;19(1):183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, et al. Effect of calcium ionophore (A23187) on embryo development and its safety in PGT cycles. Front Endocrinol. 2023;13:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Guidong Yao, upon reasonable request.