Abstract

Background

Local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication. Under general anesthesia, neurological signs are often masked, delaying diagnosis and increasing the risk of sudden cardiovascular collapse. Therefore, early detection methods are critically needed.

Case presentation

A 48-year-old male patient (height: 182 cm, weight: 98 kg) underwent resection of a mediastinal goiter. He received 10 mL of 4% lidocaine for topical airway anesthesia and 20 mL of 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine for chest wall anesthesia. Thirty minutes after airway anesthesia, continuous theta waves appeared on the frontal electroencephalogram (EEG), which were enhanced following chest wall anesthesia. These waves transitioned into a repeating pattern and evolved into sharp periodic discharges. After administering 150 mL of 20% lipid emulsion, the EEG normalized.

Conclusions

This case highlights that EEG monitoring during general anesthesia may facilitate the early detection of LAST and provide real-time feedback on treatment efficacy.

Keywords: Electroencephalogram, Electrographic seizures, Epileptiform discharges, Local anesthetic systemic toxicity

Background

Local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication associated with the use of local anesthetics [1]. Clinical manifestations of LAST encompass a spectrum of neurological and cardiovascular symptoms, starting with mild symptoms (e.g., dizziness, tinnitus, and conduction disturbances) and progressing to severe symptoms (e.g., seizures, coma, and cardiac arrest) [2]. Early recognition of LAST and prompt treatment with lipid emulsion, which promotes the redistribution of local anesthetics from the brain and heart to peripheral tissues such as muscle and liver, are critical for ensuring patient safety [1].

In approximately 70% of cases, neurological symptoms precede the onset of cardiovascular symptoms [2]. However, under general anesthesia, particularly when neuromuscular blockade is used, the typical neurological signs of toxicity are often masked. This delay in recognizing LAST increases the risk of sudden cardiovascular collapse [3]. These challenges underscore the need for clinical advancements to enable the early detection of LAST during general anesthesia.

Here, we report a case in which electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring under general anesthesia appeared to facilitate the early detection of LAST and provide real-time feedback on treatment efficacy. Written informed consent for publication of this case report was obtained from the patient.

Case presentation

A previously healthy 48-year-old male patient (height: 182 cm, weight: 98 kg) was scheduled to undergo resection of a mediastinal goiter. Preoperative laboratory investigations were within normal limits. A chest radiograph revealed no lung infiltrates or cardiomegaly. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed normal sinus rhythm at 60 bpm. Computed tomography of the neck and chest revealed a tumor measuring 191 × 84 × 68 mm, extending from the right thyroid lobe to the anterior region of the tracheal bifurcation. The tumor caused leftward deviation and compression of the trachea in the cervical region and posterior compression in the thoracic region. The patient presented with dyspnea in the supine position, although arterial oxygen saturation was maintained at 99% on room air. No central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities were noted preoperatively.

The patient received no premedication. In the operating room, standard biometric monitoring was performed. Additionally, invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring, processed EEG, and acceleromyography at the adductor pollicis muscle were implemented. Processed EEG monitoring was conducted using a BIS Quatro sensor (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) placed on the left forehead, with electrode impedance maintained at 5 kΩ or less throughout the procedure. EEG waveform data were recorded in a database at a sampling rate of 250 Hz and analyzed offline using MATLAB R2024a (MathWorks, Natick, MA). The power spectrum and spectrogram were generated using the Chronux mtspecgramc function with the following parameters: a window length of 3 s, a 0.5-s overlap, a time-bandwidth product of 3, and 5 tapers.

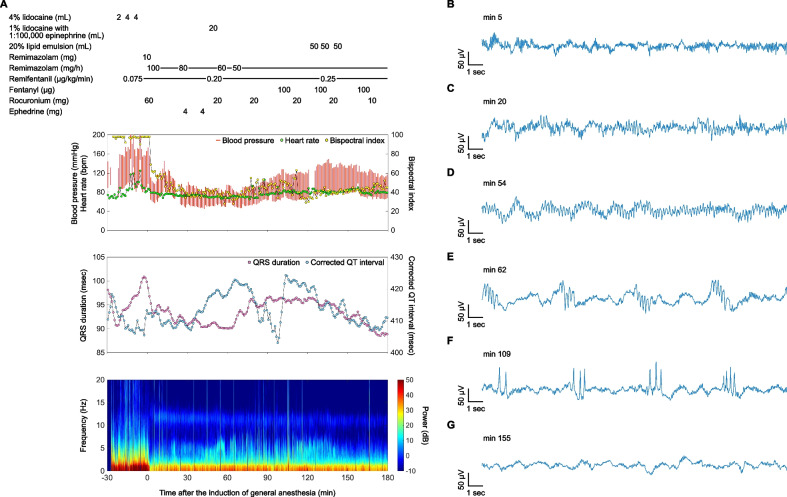

The anesthetic record and EEG spectrogram throughout the course of events are shown in Fig. 1A. Due to the presence of a potentially difficult airway, awake nasotracheal intubation was performed using a local anesthetic spray (total of 10 mL of 4% lidocaine) and a continuous infusion of remifentanil at 0.075 μg/kg/min. Following successful intubation, general anesthesia and neuromuscular blockade were induced with 10 mg of remimazolam and 60 mg of rocuronium, respectively. The initial frontal EEG waveform after induction of general anesthesia exhibited delta and alpha oscillations (Fig. 1B). General anesthesia was maintained with remimazolam (30–100 mg/h), remifentanil (0.075–0.25 μg/kg/min), and intermittent boluses of fentanyl (total dose: 700 μg). Neuromuscular blockade was maintained with intermittent boluses of rocuronium, achieving a train-of-four count of less than 1 throughout the surgery.

Fig. 1.

Anesthetic record with a spectrogram of the frontal electroencephalogram (EEG), and time-domain frontal EEG signatures. A Anesthetic record and spectrogram throughout the course of events, with time 0 marking the induction of general anesthesia. EEG waveform (B) after induction of general anesthesia with remimazolam, showing delta and alpha oscillations; C 30 min after topical airway anesthesia with a total of 10 mL of 4% lidocaine, displaying the emergence of continuous theta waves; D immediately after local anesthesia of the chest wall with 20 mL of 1% lidocaine containing 1:100,000 epinephrine, illustrating enhanced continuous theta waves; E after the transition of theta waves to a frequently repeating pattern, persisting for approximately 1 s every 5 s; F following the emergence of sharp 2–5 phase periodic discharges, exhibiting a similar duration and cycle to the theta waves; G after administering a total of 150 mL of 20% lipid emulsion, showing the return of delta and alpha oscillations

Thirty minutes after the administration of topical airway anesthesia, continuous theta waves appeared on the frontal EEG (Fig. 1C). These theta waves were further enhanced immediately after the administration of 20 mL of 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine for chest wall local anesthesia (Fig. 1D). Subsequently, the theta waves transitioned into a frequently repeating pattern, persisting for approximately 1 s every 5 s (Fig. 1E). Eventually, sharp 2–5 phase periodic discharges emerged, exhibiting a similar duration and cycle to the theta waves (Fig. 1F). Following the administration of 20% lipid emulsion in divided doses of 50 mL, totaling 150 mL, the EEG normalized to delta and alpha oscillations (Fig. 1G).

During the period of EEG alterations, the bispectral index ranged from 28 to 63. The predicted effect-site concentrations of remimazolam [4], remifentanil [5], and fentanyl [6] were 660–880, 2.5–8.5, and 0–2.3 ng/mL, respectively. Although the QRS duration and corrected QT interval on the ECG were slightly prolonged, with fluctuations observed in the corrected QT interval (Fig. 1A), both normalized following lipid emulsion therapy.

The surgery was completed uneventfully in 368 min. The patient was alert and calm 8 min after the discontinuation of remimazolam infusion. He followed commands 3 min after the administration of 0.2 mg flumazenil. Following uneventful extubation, the patient remained stable and exhibited no prodromal CNS symptoms of LAST, such as dizziness or tinnitus. His postoperative course was uneventful except for right ulnar nerve palsy, likely caused by intraoperative compression of the right upper limb. He was discharged on postoperative day 10.

Discussion

Under normal circumstances, local anesthetics block nerve conduction by inhibiting the transduction of sodium, calcium, and potassium through voltage-gated ion channels located in the cell membrane [1]. At increasing plasma concentrations, local anesthetics initially compromise cortical inhibitory pathways by disrupting inhibitory neuron depolarization [7]. This inhibition leads to excitatory clinical features, including sensory changes, muscular activation, and seizure activity. As plasma concentrations continue to rise, excitatory pathways are also affected, resulting in a depressive phase of neurological toxicity.

Given the effects of local anesthetics on multiple ion channels and the diverse CNS presentations in LAST, it is plausible that EEG monitoring could reveal a variety of abnormal signatures. EEG monitoring allows real-time assessment of cortical electrical activity, enabling clinicians to detect epileptiform discharges or other abnormal patterns. However, the effects of local anesthetics on human EEG signatures under general anesthesia are poorly documented, making it challenging to definitively attribute specific EEG alterations to LAST.

In the present case, several points suggest that the observed EEG changes may have been caused by LAST: (1) theta waves are not typically predominant in frontal EEG under the predicted effect-site concentration of remimazolam in this patient [8]; (2) lidocaine absorption through the upper airway mucosa peaks at plasma levels approximately 20–60 min after administration [9]; (3) LAST can persist for several hours following airway local anesthesia [10]; (4) theta wave power was enhanced immediately after the administration of lidocaine combined with epinephrine, which is associated with greater CNS toxicity compared to lidocaine alone [11]; (5) theta waves evolved into sharp waves, suggesting epileptiform discharges [12]; and (6) sharp waves resolved after lipid emulsion therapy, coinciding with the normalization of the QRS duration and corrected QT interval on the ECG [7]. Remifentanil and fentanyl are known to cause EEG slowing in a dose-dependent manner; however, the predicted effect-site concentrations in this patient were unlikely to have induced EEG slowing to the extent of theta wave activity [13, 14].

The diagnostic criteria for electrographic seizures, as outlined by the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society, include epileptiform discharges averaging > 2.5 Hz for ≥ 10 s (> 25 discharges in 10 s) or any pattern with definite evolution lasting ≥ 10 s [12]. In the current case, the evolution of EEG morphology was observed as follows: continuous theta waves, followed by repeating series of theta waves, and subsequently sharp 2–5 phase periodic discharges, suggesting the development of electrographic seizures.

One possible explanation for the absence of clinical convulsions is the maintained neuromuscular blockade during surgery. Despite the continuous infusion of remimazolam, a benzodiazepine recommended for managing seizures associated with LAST [1], sharp waves were observed. In response, 20% lipid emulsion was administered in divided doses under careful observation. Although it is unclear whether the neuropathophysiology observed in this patient required emergency intervention, aggressive management was undertaken due to concerns about the potential for LAST to manifest as sudden cardiovascular collapse under general anesthesia [1, 3]. Lipid emulsion therapy for LAST is associated with rare or minimal adverse effects [1, 2], and its benefits were considered to outweigh the risks. Consequently, the pronounced EEG changes and minor ECG abnormalities normalized without any complications.

In conclusion, the present case suggests that EEG monitoring following the administration of local anesthetics during general anesthesia may facilitate the early detection of LAST and the evaluation of treatment efficacy. Since perioperative frontal EEG monitoring is routinely performed to assess the depth of anesthesia, leveraging EEG for the diagnosis and management of LAST appears to be both practical and feasible. Further research is warranted to elucidate the effects of local anesthetics on EEG patterns under general anesthesia and to evaluate the clinical utility of EEG monitoring for the diagnosis and treatment of LAST in this context.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CNS

Central nervous system

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- EEG

Electroencephalogram

- LAST

Local anesthetic systemic toxicity

Authors’ contributions

RW participated in the anesthetic management of the patient, contributed to the conception and design of the work, analyzed and interpreted the electroencephalogram, and drafted the manuscript. SA contributed to the conception and design of the work, analyzed and interpreted the electroencephalogram, and provided significant feedback on the manuscript. SH participated in the anesthetic management of the patient and provided significant feedback on the manuscript. YU contributed to the conception and design of the work and provided significant feedback on the manuscript. MI supervised the anesthetic management of the patient and provided significant feedback on the manuscript. MA contributed to the conception and design of the work and provided significant feedback on the manuscript. KU critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have reviewed the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Support was provided solely from institutional and/or departmental sources.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of this case report was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Neal JM, Woodward CM, Harrison TK. The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Checklist for Managing Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity: 2017 Version. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:150–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gitman M, Barrington MJ. Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity: A Review of Recent Case Reports and Registries. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:124–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Gregorio G, Neal JM, Rosenquist RW, Weinberg GL. Clinical presentation of local anesthetic systemic toxicity: a review of published cases, 1979 to 2009. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35:181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masui K, Stöhr T, Pesic M, Tonai T. A population pharmacokinetic model of remimazolam for general anesthesia and consideration of remimazolam dose in clinical practice. J Anesth. 2022;36:493–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eleveld DJ, Proost JH, Vereecke H, et al. An Allometric Model of Remifentanil Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:1005–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bae J, Kwon M, Lee YH, Lee EK, Choi BM, Noh GJ. An allometric pharmacokinetic model and minimum effective analgesic concentration of fentanyl in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:976–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Boghdadly K, Pawa A, Chin KJ. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity: current perspectives. Local Reg Anesth. 2018;11:35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenried A, Schüttler J, Lerch M, Ihmsen H, Jeleazcov C. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of remimazolam (CNS 7056) after continuous infusion in healthy male volunteers: part II. Pharmacodynamics of electroencephalogram effects. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:652–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Efthimiou J, Higenbottam T, Holt D, Cochrane GM. Plasma concentrations of lignocaine during fibreoptic bronchoscopy. Thorax. 1982;37:68–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearson F, Chiam P. Local anaesthetic toxicity during an awake tracheal intubation course. Anaesth Rep. 2020;8:6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi R, Oda Y, Tanaka K, Morishima HO, Inoue K, Asada A. Epinephrine increases the extracellular lidocaine concentration in the brain: a possible mechanism for increased central nervous system toxicity. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:984–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsch LJ, Fong MWK, Leitinger M, LaRoche SM, Beniczky S, Abend NS, et al. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society’s Standardized Critical Care EEG Terminology: 2021 Version. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2021;38:1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egan TD, Minto CF, Hermann DJ, Barr J, Muir KT, Shafer SL. Remifentanil versus alfentanil: comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in healthy adult male volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:821–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott JC, Ponganis KV, Stanski DR. EEG quantitation of narcotic effect: the comparative pharmacodynamics of fentanyl and alfentanil. Anesthesiology. 1985;62:234–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.