Abstract

Alanine racemase (Alr) catalyzes the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent racemization between l- and d-alanine in bacteria. Owing to the potential interest in targeting Alr for antibacterial drug development, several studies have determined the structures of Alr from different species, proposing models for the reaction mechanism. Insights into its reaction dynamics may be conducive to a better understanding of the Alr reaction mechanism. In this study, we determined the structures of the apo and reaction states of Bacillus subtilis Alr (BsAlr) at room temperature using a fixed-target based X-ray free-electron laser. The 2.3 Å resolution structures revealed the alanine substrate or intermediate in various positions at the active site. Conformational change between the N- and C-terminal domains of BsAlr expanded the entryway for substrate binding. In the reaction state of BsAlr, two main alanine binding states were observed: one alanine molecule is positioned away from PLP, whereas the other alanine molecule is covalently bonded to PLP. These structures might represent the dynamic states of the substrate for entrance into, reaction with, or exit from the active site. Our approach provides a simple and rapid method for elucidating the intermediate structure of Alr, which can be expanded to other enzymes.

Keywords: Racemase, Antibiotic drug target, Intermediate, X-ray free-electron laser, Reaction mechanism

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Molecular biology, Structural biology

Introduction

Peptidoglycan plays a critical role in maintaining bacterial cell shape1, and d-alanine is essential for its integrity, as it cross-links the peptidoglycan layers, providing mechanical strength and rigidity2. In bacteria, alanine racemase (Alr) catalyzes the racemization reaction between l- and d-alanine (Ala) in a pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent manner3,4. The absence of Alr function in eukaryotes makes this enzyme an attractive target for antibacterial drug development5–7. Understanding the structures and mechanisms of different Alr enzymes is an important step in the design of Alr inhibitors8,9.

To date, the crystal structures of Alr from various bacterial species have been reported3,10–19. Each of these Alr monomers comprises an N-terminal α/β barrel and a C-terminal extended β-strand domain3. These monomers form a homodimeric structure with a head-to-tail arrangement, which is essential for active site formation. The PLP molecule is located on the α/β barrel and forms the internal aldimine with a catalytic Lys residue3. In Bacillus subtilis Alr (BsAlr), the active site contains two conserved catalytic residues, Lys39 and Tyr272′ (prime symbols represent residues from another subunit), which vertically flank the pyridine ring of PLP. Near the PLP, His169 bridges Arg225 and Tyr272′14. The residues involved in racemase reactions are highly conserved in most species20.

Structural and biochemical analyses have suggested the following racemization mechanism for Alr: Arg225 interacts with the pyridine nitrogen atom of PLP and forms hydrogen bonds consisting of Arg225-His169-Tyr272′, thus lowering the pKa of Tyr272′ and allowing it to abstract a proton from the Cα atom of l-Ala21. Tyr272′ then transfers a proton to the carboxylate group of the external aldimine carbanion, which subsequently delivers a proton to Lys39. Next, the amino group of Lys39 protonates the carbanion to form d-Ala22. In the proton transfer event from the aldimine carbanion carboxylate group to Lys39, it has been proposed that the carboxylate group is rotated along the Cα-C bond22. However, such movement has been questioned because the carboxylate group of Ala interacts with nearby residues, which may form an energy barrier, making this event difficult to complete23.

X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) are efficient for time-resolved analysis in which the ultrafast dynamics of enzymes can be elucidated24,25. For time-resolved serial femtosecond X-ray crystallography (SFX) analysis, the substrate analogs must be activated at a designated time point through various pulses such as pH and temperature26. However, the preparation of a substrate or intermediate analog is challenging. Although not as effective and accurate as time-resolved SFX, we employed an alternative approach to obtain the averaged reaction structures in multiple conformations using fixed-target method in XFEL at room temperature, which we previously used to elucidate the structural dynamics of cyanase27. In this study, we investigated the reaction mechanism of Alr by determining its crystal structure during the reaction using an XFEL. The XFEL structures of BsAlr incubated with l-Ala revealed either a substrate Ala or an intermediate (or a product), including an external aldimine intermediate, at various positions. We observed at least three different types of Ala positions forming different interaction networks with the active site residues. A comparison of these classified structures with previous studies14,16,22 revealed a substrate (or intermediate) in new positions, as well as a similar intermediate structure. Based on these structures, we propose a reaction mechanism for Alr. We suggest that the method used in this study can also be applied to investigate the intermediate structures of other enzymes.

Materials and methods

Cloning and protein purification

The full-length alr2 gene encoding BsAlr (UniProt code: P94494) was amplified via PCR using B. subtilis genomic DNA. The amplified DNA was cloned into the NdeI and XhoI sites of a pET-28a (Novagen) vector containing an N-terminal hexahistidine tag. The recombinant DNA was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells. The cells were grown in lysogeny broth medium supplemented with 0.1 µg/mL kanamycin at 37℃. When the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.5, protein expression was induced by adding isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside to a final concentration of 1 mM. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h with shaking at 200 rpm. Thereafter, the cells were harvested via centrifugation for 20 min at 4 ℃ and 4,600 × g and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). After cell lysis via sonication, the cell debris was removed using centrifugation for 1 h at 4 °C and 31,660 × g. The supernatant was loaded onto a HiTrap chelating HP column (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) equilibrated with buffer A (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol) containing 10 mM imidazole. The resin was washed with buffer A containing 50 mM imidazole, and the protein was eluted using a linear gradient of imidazole (10–500 mM) in Buffer A. The elution was dialyzed overnight at 4 °C with thrombin to cleave the N-terminal hexahistidine tag. Thereafter, His-tag cleavage was verified and the purity of the obtained proteins was analyzed using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Crystallization

Purified BsAlr was concentrated to 5 mg/mL using a Centricon (Merck, NJ, USA). The crystallization of B. subtilis Alr was performed using batch crystallization at 293 K. The protein (50 µL) and crystallization solutions (125 µL) containing 100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.5), 0.25 M MgCl2, and 25% (w/v) PEG 4000 were mixed in a 1.5 mL microtube. Suitable crystals for X-ray diffraction were grown within two days. The crystals were rectangular-shaped with dimensions of 20 × 20 × 50 µm3.

Data collection

XFEL data were collected at the nanocrystallography and coherent imaging (NCI) experimental hutch at the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory X-ray Free Electron Laser (PAL-XFEL; Pohang, Republic of Korea)28,29. The photon energy and flux were 12,400 eV and ~ 5 × 1011 photons/pulse, respectively. The X-ray repetition rate was 30 Hz and the X-ray beam size at the sample point was 4 μm × 4 μm (horizontal × vertical: full-width at half-maximum)30. The BsAlr crystals were delivered to the X-ray interaction point using a nylon mesh-based sample holder (Supplementary Fig. S1a online)31. To obtain the apo state, a BsAlr crystal suspension was loaded and evenly distributed onto the nylon mesh (60 μm pore size) on a fixed-target sample holder (20 × 20 mm) and immediately sealed with polyimide film to prevent crystal dehydration. The BsAlr crystal-containing sample holder was positioned in the fixed-target sample chamber. The sample holder containing the BsAlr crystal was raster scanned from the top to the bottom. The sample holder was scanned at 50 μm intervals in both horizontal and vertical directions, ensuring each crystal was exposed to the X-ray only once. The velocity of the sample holder mounted in the translation stage was 1.5 mm/s in both horizontal and vertical directions.

To obtain the reaction state, a suspension of BsAlr crystals was mixed with an equal volume of crystallization solution containing 400 mM L-Ala in an 1.5 mL micro-tube (Total 60–80 µL per one sample holder, Supplementary Fig. S1a online). This mixture was immediately transferred to the nylon mesh using the same preparation method as for the apo state BsAlr. The diffraction data were recorded using an MX225-HS detector (Rayonix, LLC, Evanston, IL, USA) at 25 ± 0.5 °C. Real-time monitoring of diffraction images was performed using OnDA32.

Data processing and refinement

Hit images containing Bragg peaks were filtered using the Cheetah33. Diffraction data collected for a 60-min period were processed for full time (0–60 min) or 20-min intervals (0–20, 20–40, and 40–60 min). The hit images were indexed and scaled using CrystFEL34 with the Mosflm35 and XGANDALF36 indexing algorithms. The phasing problem was solved by molecular replacement using Phaser37, with the crystal structure of B. subtilis Alr (PDB ID 6Q72)14 as the search model. Model building and structure refinement were performed using COOT38 and phenix.refine in PHENIX39, respectively. Geometries of the final model structures were evaluated using MolProbity40. The model structures were visualized using PyMOL41. Electron density maps, including simulated annealing omit and 2Fo-Fc electron density maps, were generated using PHENIX39.

Results

Structure determination of the apo- and reaction-state of BsAlr

To obtain accurate structural information, we collected XFEL data of the apo-state of BsAlr, which provides a room-temperature structure without radiation damage. Using a total of 68,582 indexed images, the room-temperature structure of the apo-state of BsAlr was determined at a 2.3 Å resolution (Table 1). In addition, to track the molecular dynamics of a substrate at the active site of Alr during the reaction, we performed XFEL diffraction data collection of BsAlr in the presence of 200 mM l-Ala using a fixed-target scanning method. During data collection, the racemase reaction, with access to and release of Ala at the active site of BsAlr occurred continuously. Consequently, the electron density map provided by the reaction state of BsAlr does not represent a single conformation at a specific time but rather an averaged electron density map reflecting the movement and binding of Ala substrates at the active site (Supplementary Fig. S1b online). In the XFEL data collected for an hour, different electron density maps corresponding to the Ala molecule were observed at four active sites within the asymmetric unit. We performed structural analysis using the entire dataset. In addition, we divided the data into three complete structural datasets (Data I, Data II, and Data III for 0–20, 20–40, and 40–60 min, respectively) based on completeness and the signal-to-noise ratio for data processing (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1a, b online). We hypothesized that the divided datasets processed at specific time intervals may provide more diverse information on the structural changes at the active site compared to a single entire dataset. Dividing the entire data into three sets based on the collection time yielded a sufficiently large amount of data that provided high-quality electron density maps and allowed us to observe electron density maps for Ala molecules at 12 active sites (Supplementary Fig. S2 online). Subsequently, we compared these electron density maps with those obtained from the entire dataset at four active sites. While three reaction states are commonly observed in all datasets, we observed variations in active sites from the divided datasets. These reaction states of BsAlr were processed up to a 2.3 Å resolution (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Data collection | Apo | 0–60 min | 0–20 min (Data I) |

20–40 min (Data II) |

40–60 min (Data III) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB ID | 8ZPE | 9JT7 | 8ZPF | 8ZPG | 8ZPH | |

| Energy (eV) | 12,400 | 12,400 | 12,400 | 12,400 | 12,400 | |

| Exposure time | 50 fs | 50 fs | 50 fs | 50 fs | 50 fs | |

| Space group | P21 | P21 | P21 | P21 | P21 | |

|

Cell dimensions a, b, c (Å) α, β, γ (°) |

87.7, 108.7, 89.2 90.0, 115.0, 90.0 |

90.2, 112.9, 91.8 90.0, 115.0, 90.0 |

90.2, 112.9, 91.8 90.0, 115.0, 90.0 |

90.2, 112.9, 91.8 90.0, 115.0, 90.0 |

90.2, 112.9, 91.8 90.0, 115.0, 90.0 |

|

| Collected images | 280,000 | 540,000 | 180,000 | 180,000 | 180,000 | |

| Hits images | 109,247 | 189,688 | 69,819 | 59,939 | 59,932 | |

| Indexed pattern | 68,582 | 99,545 | 40,081 | 28,773 | 30,692 | |

| Resolution (Å) |

50.0–2.30 (2.39–2.30)a |

50.0–2.30 (2.39–2.30) |

50.0–2.30 (2.39–2.30) |

50.0–2.30 (2.39–2.30) |

50.0–2.30 (2.39–2.30) |

|

| Reflections | 132,320 (19,407) | 156,084 (15,614) | 146,820 (20,790) | 146,719 (20,730) | 146,722 (20,700) | |

| redundancy | 335.85 (56.8) | 1526.56(1037.0) | 655.44 (445.3) | 414.54 (281.6) | 463.78 (315.0) | |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) | |

| SNR | 4.79 (0.79) | 5.99(1.62) | 3.86 (0.82) | 3.51 (0.73) | 3.40 (0.66) | |

| CC* | 0.99 (0.63) | 0.99(0.66) | 0.99 (0.46) | 0.99 (0.44) | 0.99 (0.43) | |

| Rsplit (%)b | 19.00 (132.89) | 12.43(96.56) | 19.68 (147.73) | 22.09 (168.87) | 21.66 (186.34) | |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 45.37 | 51.04 | 51.46 | 51.26 | 52.11 | |

| Refinement | ||||||

| Resolution (Å) |

50.0-2.3 (2.34–2.30) |

50.0-2.3. (2.42–2.30) |

50.0-2.3. (2.42–2.30) |

50.0-2.3. (2.42–2.30) |

50.0-2.3. (2.42–2.30) |

|

| Rwork | 0.1782 (0.3744) | 0.1847(0.3073) | 0.1964 (0.3532) | 0.2046 (0.3546) | 0.2010 (0.3465) | |

| Rfreec | 0.2324 (0.3859) | 0.2330(0.3830) | 0.2460 (0.4105) | 0.2592 (0.3720) | 0.2541 (0.3910) | |

| No. of water molecules | 219 | 198 | 176 | 78 | 83 | |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||||||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.009 | |

| Bond angle (°) | 0.944 | 1.003 | 0.980 | 1.067 | 1.042 | |

| B factors (Å2) | ||||||

| Protein | 46.25 | 53.69 | 56.44 | 53.61 | 54.14 | |

| Ligands | 50.03 | 54.49 | 56.69 | 54.67 | 55.67 | |

| Water | 40.31 | 47.65 | 49.52 | 47.48 | 49.10 | |

| Ramachandran (%) | ||||||

| Preferred | 96.16 | 95.25 | 94.08 | 93.04 | 93.16 | |

| Allowed | 3.58 | 4.10 | 5.14 | 5.92 | 5.99 | |

| Outliers | 0.26 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 1.04 | 0.85 | |

a Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

bRsplit = 2−0.5 * sum(|I1-kI2|) / [ 0.5*sum(I1 + kI2) ]

c The free set represents a random 5% of reflections that were not included in refinement.

Structure of BsAlr in the apo-state

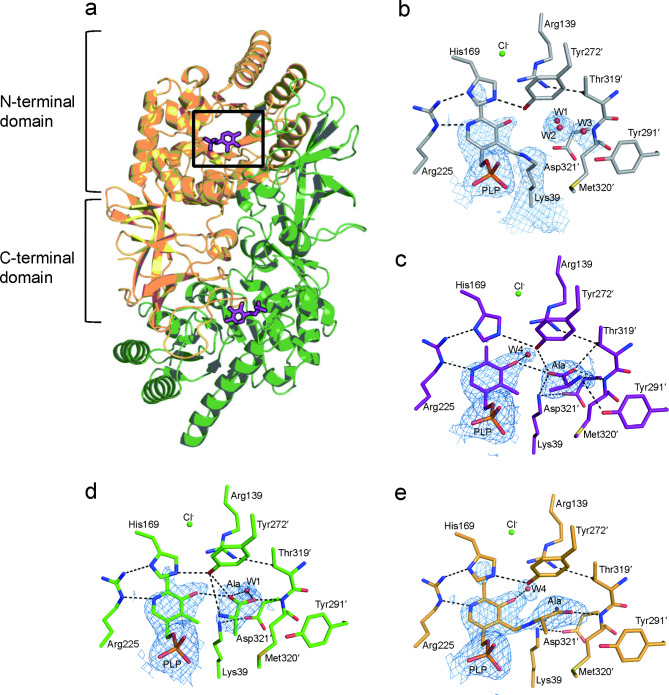

The apo BsAlr determined via XFEL at room temperature revealed two BsAlr dimers in the asymmetric unit. The electron density map of apo BsAlr was well defined from the Met1 to Lys386 of the four monomers. Each monomer of BsAlr consisted of N-terminal α/β barrel and C-terminal β-strands domains. The active site was located in the interspace between the α/β barrel domain of one subunit and β-strands domain of the other (Fig. 1a). PLP was covalently linked to Lys39 at the mouth of the α/β barrel, forming an internal aldimine, as previously reported (Fig. 1b)3. The electron density map for the C2 and C2A atoms of PLP was of poor quality compared to that for the other PLP atoms, suggesting the high flexibility of this region as judged by a higher B-factor (52.1 Å2) relative to those of the neighboring residues Arg139, His169, and Arg225 (41.6 Å2) (Supplementary Fig. S3a, b online). His169 is located between Arg225 and Tyr272′ near the PLP and stabilizes the position of Tyr272′. The phosphate group of PLP was stabilized through hydrogen bonds with Tyr43, Thr210, and Tyr364 (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S3c, d online).

Fig. 1.

Overall XFEL structure of BsAlr determined at room-temperature. (a) The crystal structure of dimeric apo BsAlr, with each monomer represented in a different color. Pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP), which is positioned at the active site (black box), is shown as magenta sticks. (b-e) The 2Fo-Fc electron density of alanine, water molecules, and pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP) at the active site are shown (blue mesh, 1σ). (b) Close-up view of the active site of apo BsAlr. (c–e) Close-up view of the active site of BsAlr in a reaction state, (c) class A (purple), (d) class A′ (green), and (e) class B (orange). Residues from the other subunit are labeled with prime symbols. The O, S, and N atoms are colored red, yellow, and blue, respectively. Putative hydrogen bonds are indicated as black dashed lines, while water molecules and chlorine ions are represented as red and green spheres, respectively.

To better understand the temperature-dependent structural changes, the room temperature structure of the BsAlr (BsAlr-RT; 293 K) determined in this experiment was compared with the previously determined BsAlr (PDB ID: 6Q71)14 at 100 K (BsAlr-100 K). Superimposition of BsAlr-RT and BsAlr-100 K exhibited an almost similar overall conformation, with r.m.s. deviations of 0.3 Å for the Cα atoms. The guanidinium group of Arg139 was stabilized through its interaction with a chloride ion. Unlike BsAlr-RT, the electron density map around the C2 and C2A atoms of PLP in all two subunits of BsAlr-100 K was clearly observed, indicating that the flexibility between the C2 and C2A atoms of PLP in BsAlr is temperature-dependent (Supplementary Fig. S3a, b online). Notably, observed water molecules were different between the BsAlr-RT and BsAlr-100 K. In the active sites of BsAlr-RT and BsAlr-100 K, water molecules were commonly bound to Asp321′, Met320′, and Tyr291′. Meanwhile, in BsAlr-100 K, two water molecules interacted with Tyr272′, whereas no water molecules were observed near Tyr272′ in BsAlr-RT, indicating that temperature affected the dynamics of water molecules at the active site of BsAlr (Supplementary Fig. S3c, d online).

Structures of BsAlr in the reaction states

The structure of BsAlr from the entire dataset (0–60 min) revealed four distinct active sites for two dimers. After molecular replacement, we observed rectangular-shaped positive Fo-Fc electron density map corresponding to an Ala molecule near the Met320′ backbone amide and Arg139 in three (class A, A′, and B, see below) out of four active sites (Fig. 1c-e and Supplementary Fig. S4a-h online). We classified the three different active sites into two classes (A and B) according to the position of Ala with respect to PLP. That is, Ala distant from PLP belongs to class A, and Ala in proximity to PLP belongs to class B.

Although the Ala substrate fits into the electron density map at the active site, we could not determine whether the density represented l- or d-Ala. This is because the density likely reflects the reaction states in which a mixture of l- and d-Ala is present. Moreover, the density resolution was not sufficient to distinguish between l- and d-Ala. As we experimentally incubated the enzyme with l-Ala, we simply modeled it as the substrate. However, considering the high concentration of enzyme used for crystallization (5 mg/ml), it is likely that a fraction of the substrate was converted into d-Ala during data collection, and thus, we also modeled d-Ala and described its interaction with neighboring residues in the active site (Supplementary Information and Supplementary Fig. S5a-c online).

Structures of BsAlr active sites in three different states

Careful inspection of the electron density maps revealed that those for the Ala substrate distant from PLP can be further divided into two classes. Thus, we divided class A into class A and A′, in which the Ala substrate can be positioned in two different orientations (Figs. 1c and d and 2a and b). We classified the structures based on positions of the carboxylate group and Cα atom of the Ala substrate with respect to the O3A and C4A atoms of PLP, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagrams of the active site of BsAlr. class A, A′ and B structures. (a-c) The active site of BsAlr in reaction states, (a) class A, (b) class A′, and (c) class B. Hydrogen bonds within a distance of 3.5 Å are depicted as dashed lines and the distances of hydrogen bonds are indicated. The residues, water molecules and pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP) are labeled. (d-f) Superimposed structures showing the orientation of Ala substrate in class A (d), class A′ (e), and class B (f) BsAlr. The rotation and position of Alr are depicted from the top view. Compared to class A, the rotation angles of class A′ and B Ala substrates are indicated. The active site residues are labeled and colored purple (class A), green (class A′), and orange (class B). The O, P, and N atoms are colored in red, orange, and blue, respectively. Near-active site residues are omitted for clarity.

In class A, the substrate was located near the inner layer of the proposed entryway comprising Tyr272′ and Tyr291′42. The Ala substrate was oriented parallel to the pyridine ring of PLP (Fig. 2a, d). The C-Cα axes of the Ala substrate was approximately 2 Å apart from pyridine ring plane toward Tyr272′ (Figs. 1c and 2a). The amine group of Ala substrate is away from the C4A atom of the PLP. Binding of the Ala substrate was stabilized via hydrogen bonds with the Met320′ backbone amide, the sidechains of Lys39, Tyr291′, and Thr319′, and the O3A atom of PLP. In this class, a water molecule located between Arg139 and PLP interacted with the O3A atom of PLP (Figs. 1c and 2a).

Compared to the Ala in class A, the Ala substrate in class A′ were rotated along the vertical axis of the peptide plane by 40° in a clockwise direction, and the Cα atom moved toward phosphate group of PLP. As a result, the Cα of the class A′ Ala located closer to the C4A atom of PLP than that of the Ala in class A (Fig. 2b, e). Hence, interactions between Ala and residues of class A′ BsAlr are different from those of class A BsAlr. The Ala substrate interacts with Thr319′ only in class A but not in class A′, whereas the Ala substrate interacts with Met320′ in both A and A′ classes. The amine group of Ala substrate was oriented toward the C4A atom, and located 3.5 Å away from the hydroxyl group of Tyr272′. As a result, the location of Ala in class A′ is more suitable for a transaldimination reaction. A water molecule near the mainchain amide of Asp321′ interacted with the carboxylate group of the substrate Ala in class A′ (Figs. 1d and 2b).

In contrast with the substrate Ala in classes A and A′, wherein the amine group of Ala was positioned over 3 Å away from the C4A atom of PLP, the amine group of Ala formed an external aldimine with the C4A atom of PLP in class B, which resembles the structure of the bound form of the reaction intermediate analog (Figs. 1e and 2c)22. The electron density map of PLP and Ala substrate indicated that these were connected via the C4A and N atoms, respectively, and the PLP-Ala ligand fits well into the density map, with the exception of the Cβ atom (Fig. 1e). The C-Cα axis of class B Ala substrate was located 1.8 Å away from the plane of the pyridine ring of PLP toward Tyr272’. Compared to the Ala substrate in class A, that in class B was rotated by 60° in a clockwise direction when viewed along the vertical axis from the top of the peptide plane (Fig. 2f). The position of the Cα atom of the B Ala was located closer to the C4A atom of PLP than those of class A and A′, respectively.

Structural comparison between Alr in the apo- and reaction-state

To better understand the substrate-induced structural changes, the apo- and reaction-state of BsAlr structures were compared. Crystallographic results showed that the unit cell dimensions of reaction state of BsAlr (a = 90.2 Å, b = 112.9 Å, and c = 91.8 Å) were slightly larger than those of the apo-state (a = 87.7 Å, b = 108.7 Å, and c = 89.2 Å). The volumes of the two BsAlr dimers in the asymmetric unit of the reaction state were larger than those of the two apo-state BsAlr dimers. The superimposition of the apo- and reaction-state BsAlr dimers exhibited an r.m.s. deviation of 1.3 Å. When the C-terminal domains of the apo- and reaction-state BsAlr structures were superimposed, the N-terminal domain containing the PLP molecule shifted away from the C-terminal domain by 1.2 Å, suggesting domain movement upon enzyme reaction (Supplementary Fig. S6a, b online). These structural changes between the two domains of BsAlr altered the width and height of the entryway channel from 2 × 3 Å for the apo form to 2 × 4 Å for the reaction-state (Supplementary Fig. S6c, d online).

Active-site environments of the apo and the three classes of reaction states of BsAlr exhibited almost identical structures. The positions of substrate-binding residues Arg139, Tyr291′, Thr319′, and Met320′ were nearly identical. Although the imidazole ring of His169 rotated among the structures, the hydrogen bond bridges in Arg225, His169, and Tyr272′ remained intact (Fig. 1b-e). In the apo structure, the Nε atom of His169 and the hydroxyl group of Tyr272′ were separated by 2.5 Å, which expanded to approximately 3 Å in the reaction states, suggesting a conformational change of Tyr272′ upon substrate binding (Fig. 1b-e). In the reaction state, Lys39 formed a hydrogen bond with Asp321′, whereas in the apo structure, it was connected to the C4A atom of PLP (Fig. 1b-e). In the apo state of BsAlr, the electron density map corresponding to the C2 and C2A atoms of PLP was disordered, which indicates a high flexibility of this moiety. In contrast, in the reaction state of BsAlr, the electron density map corresponding to the O3A and C2 atoms of PLP was clearly observed suggesting that the binding of Ala to the active site may contribute to stabilization of the pyridine ring. In the apo state of BsAlr, water molecules were bound to Asp321′, Met320′, and Tyr291′, but these were absent in the reaction structure. Instead, the carboxylate group of the Ala substrate occupied the corresponding region (Fig. 1b-e). This observation suggests that the position of the water molecule in the active site continuously changes as substrate access and product release occur during the reaction process.

Structural comparison between Alr in the entire and three divided datasets

We also calculated electron density maps from Data I, II, and III in the data divided in 20-min intervals. The three datasets revealed 12 active sites for two dimers from each dataset. The two, three, and two structures belonged to class A, A′ and B, respectively. Structures from Data I revealed the active sites occupied with the substrates belonged to class A and A′. Active sites in the structure from Data II showed the electron density maps for the substrates belonged to class A, A′ and B. Data III provided the electron density maps at the active sites representing class A′ and B. While electron density maps are similar to those obtained from the entire dataset, we observed slight variations in the electron density maps of several active sites from the divided datasets (Supplementary Fig. S2 online). For five active sites, electron density maps for the Ala substrate were not well defined, thus we did not build models.

While conformations of BsAlr from the three datasets can be analyzed in a time-dependent sequential manner, our data are unlikely to represent the exact time dependency because they provide the average structures for different steps in the reaction. Additionally, we expected the variation in the substrate-penetration time to cause time differences in substrate binding and reaction for each microcrystal. The Ala substrates in each active site of three divided datasets exhibited interactions with neighboring residues of BsAlr similar to those observed in the structure from the entire dataset. The most notable differences are observed in class B. In class B, all atoms of the two Ala substrates, except for the Cβ atoms, were almost in the same plane. However, the two carboxylate groups of class B Ala substrates are laterally displaced by 0.6 Å in the plane. Hence, one Ala substrate was positioned closer to PLP, allowing it to interact with the Met320′, Arg139, Lys39, and O3A atom of PLP as well as with Tyr272′. The other Ala substrate formed hydrogen bonds only with Met320′ and Tyr272′. In addition, the active site of only one class B contained a water molecule, which was located between Arg139 and Ala and was interacting with the carboxylate group of Ala (Supplementary Fig. S7 online).

Comparison of the structures between BsAlr-Ala and the reported Alr-Ala complex

To enhance our understanding of the PLP and Ala binding site in Alr, structures of the BsAlr determined in this work were compared to the structure of Alr in complex with Ala from Latilactobacillus sakei UONUMA (U1Alr) (PDB ID: 7XLL)16. At the active sites of BsAlr classes A-B, the NZ atom of Lys39 formed a hydrogen bond with Asp321′ and away from the C4A atom of PLP without forming a Schiff base. In U1Alr, the NZ atom of Lys41 (Lys39 of BsAlr) covalently bound with the C4A atom of PLP, forming an internal aldimine with PLP (Supplementary Fig. S8a, b online).

The orientation of Ala substrate relative to PLP in U1Alr was most similar to that in class A′ of BsAlr (Supplementary Fig. S8c online). However, the C-Cα axis of U1Alr Ala was found to be over 0.5 Å higher in position than class A′ Ala substrates from the pyridine ring plane toward Tyr271′ (Tyr272′ of BsAlr). This orientation of U1Alr Ala caused its amine group to be located closer to Tyr271′, as compared to class A′ Ala (Supplementary Fig. S8d online).

Comparison between class B Alr and PLP-Ala-bound Alr

In the l-Ala-modeled class B structure, the Cα atom of l-Ala is 3.1 Å and 4.2 Å apart from the hydroxyl group of Tyr272′ and the amino group of Lys39, respectively. When d-Ala was modeled, its position and corresponding distances were 3.6 Å and 4.1 Å, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S9 online). In reported structures of the Geobacillus subtilis Alr (GsAlr) complexed with PLP-l-Ala (PDB ID: 1L6F)22, the pyridine ring of PLP tilted by 20° toward catalytic Tyr compared to that of class B BsAlr. In addition, the carboxylate and amine groups of GsAlr l-Ala were shifted within a range of 0.4–1.0 Å toward Lys39 compared to those of l-Ala of class B BsAlr. The Cα atom of l-Ala in GsAlr was 3.6 Å away from the hydroxyl group of Tyr265′ (Tyr272′ of BsAlr) and the amino group of Lys39. In PLP-d-Ala of GsAlr (PDB ID: 1L6G), the Cα atom of d-Ala is 1.7 Å away from that of class B Ala in BsAlr toward Lys39, but the carboxyl carbon is 0.4 Å away from that of class B Ala in BsAlr. The distances from the Cα atom of d-Ala to Tyr265′ and Lys39 were 4.0 Å and 3.5 Å, respectively (Fig. 3a). Thus, the position of the Cα atom of Ala in class B with respect to the catalytic Tyr was similar to that of the PLP-l-Ala of GsAlr in the superimposed structures between class B BsAlr and PLP-l-Ala or PLP-d-Ala of GsAlr (Fig. 3b). Even in the d-Ala-modeled class B, the Cα position was closer to the hydroxyl group of Tyr272′ than to the amino group of Lys39. These observations suggest that the Ala in class B BsAlr likely represents l-Ala. The distances between the Ala-interacting residues in the active site and Ala are listed in Supplementary Table S1 online.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the external aldimine structure of BsAlr class B and GsAlr. (a) Superimposed structures of GsAlr complexed with pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP)-l-Ala (PDB ID: 1L6F) and PLP-d-Ala (1L6G) depicted as pink and blue sticks, respectively. Distances of Tyr265′ and Lys39 to the Cα of alanine are presented as colored dashed lines. (b) Superimposed structures of BsAlr class B (orange, Data III), BsAlr class B (pale-green, Data II), GsAlr with PLP-l-Ala (pink), and GsAlr with PLP-d-Ala (blue). Residue numbers of GsAlr are labeled in parentheses. (c) Comparison of the external aldimines and their interacting residues of BsAlr class B and GsAlr PLP-Ala. The distances of interaction within 3.5 Å are indicated as dashed lines. Near-active site residues are omitted for clarity. (d) Potential proton transfer of BsAlr class B (left, orange) and GsAlr PLP-l-Ala (right, blue). In GsAlr PLP-l-Ala, the rotation of carboxylate group is indicated by a dashed arrow.

The carboxylate groups of Ala in class B and PLP-Ala of GsAlr interacted with the backbone amide of Met320′ (Met312′ of GsAlr) and Arg139 (Arg136 of GsAlr). As previously mentioned, in the two Ala substrates in class B BsAlr, one carboxylate group of Ala is located closer to the O3A atom of PLP, whereas the other is closer to Tyr291′. By contrast, the one carboxyl oxygen of PLP-l-Ala in GsAlr is 3.6 Å and 3.7 Å away from the O3A atom of PLP and Tyr284′ (Tyr291′ of BsAlr), respectively (Fig. 3c). This suggests that the Ala group of the external aldimine can shift laterally between Tyr291′ and the O3A atom of PLP in BsAlr. Moreover, a carboxyl oxygen of the Ala substrate in another class B is located to form a hydrogen bond network with the hydroxyl group of Tyr272′, the O3A atom of PLP, and the amino group of Lys39 (Fig. 3c). Thus, our result suggests that the carboxylate group of the Ala substrate facilitates proton transfer between Tyr272′ and Lys39 without rotation of the Cα-C axis (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table S1 online). In GsAlr, the carboxylate group of Ala interacted with either Tyr265′ (Tyr272′ of BsAlr) in PLP-l-Ala or Lys39 in PLP-d-Ala (Fig. 3c), and it has been proposed that the Cα-C bond of Ala has to be rotated to transfer a proton between Tyr265′ and Lys39 (Fig. 3d)22.

Discussion

Alr is essential for bacterial cell wall synthesis and is an attractive target for antibacterial drug development. To understand its molecular mechanisms and structural dynamics, we determined the room-temperature structure of BsAlr using SFX. For structural mechanism analyses, we collected XFEL data of BsAlr in the presence of an l-Ala substrate. Our approach to divide the data into three datasets was to observe more structural variations in the active sites. However, this approach does not explain the structural variations in a time-dependent manner. Moreover, it has limitations in observing unstable intermediates that undergo fast structural transition. Nevertheless, when compared with the electron density maps from the entire dataset for the time period of 0 to 60 min, we clearly observed additional variations in the electron density maps from the three-datasets. This observation offers valuable insights into the dynamics of BsAlr during the reaction process, the accessibility and binding of a substrate, as inferred from the partial electron density map observed at the active site43.

The electron density maps for the PLP and Ala molecules were clearly divided into classes A and A′, whereas the corresponding electron density maps were conjugated, representing the external aldimine state in class B. Kinetic analysis of GsAlr (42% amino acid sequence identity with BsAlr) revealed a Vmax value of 2550 U/mg for l -to d-Ala conversion44, which suggests that the active site of the BsAlr crystal contains a mixture of l- and d-Ala. However, because various factors such as crystallization solution and diffusion rate could influence the kinetics of Ala binding to BsAlr in the crystal state, it would be difficult to apply enzyme kinetics information in solution to elucidate the ratio of the l- to d-Ala in the electron density maps obtained from the XFEL data. Thus, we simply modeled either l- or d-Ala in the active site in some reaction states. Throughout this study, we measured the distances between the modeled molecules in the analysis of the active site. However, our data shows that several states are mixed during the reaction step, indicating that the distances between molecules may not be accurate. Therefore, rather than focusing on distance values for the interactions between molecules, the relative arrangement and orientation of the molecules should be considered.

Based on the current structural analyses and previous mechanistic studies, we propose the following reaction mechanism for BsAlr. In the apo-state, the PLP molecule in BsAlr is covalently bonded to Lys39 residues, and water molecules occupy the Ala substrate-binding site. In the initial reaction stage, the l-Ala substrate accesses the substrate-binding site of BsAlr. The orientation of the Ala molecules differed significantly among the classified groups. For example, in class A, the amine group of l-Ala faces in the opposite direction of PLP, whereas in class A′, it is directed toward the pyridine ring of the PLP molecule, displaying a positional rearrangement (Fig. 1c, d). The orientation of the amine group of l-Ala and the distance between the l-Ala and PLP molecules suggest that the l-Ala in class A may represent the initial substrate entry into or product exit from the active site (Figs. 4, (1)-(2)). Although we did not observe the electron density of a Schiff base between the PLP and Lys39 in class A, we believe that the PLP should form a Schiff base as observed in the alanine bound structure of U1Alr16. We reason that this is because several reaction states are mixed in our experimental condition. After the change in the position of l-Ala occurs, the carboxylate group of Ala moves from the initial substrate-binding site to the PLP molecule, as observed in class A′. Accordingly, the amine group of class A′ Ala interacts with Tyr272′, placing the Cα atom of Ala in a closer proximity to the C4A atom of PLP. For class A′, the PLP did not form a Schiff base with either Lys39 or the substrate Ala. We speculate that this may represent states in which the amine group of the substrate Ala makes a nucleophilic attack to cleave the C-N bond between Lys39 and the PLP. Alternatively, the amine group of Lys39 makes a nucleophilic attack on the C-N bond between PLP and the substrate Ala. In this case, we do not exclude the possibility that the alanine observed in the electron density map could be d-Ala (Supplementary information).

Fig. 4.

Potential reaction mechanism of Alr proposed on the basis of the BsAlr structures in the apo and reaction states; (1) an internal aldimine is formed in the apo state. (2) and (3) depict the active site of class A′, where the amine group of Ala is in close proximity to Tyr272′. (4) represents the active site of class B, where l-Ala forms an external aldimine with PLP. (5) and (6) illustrate the reaction process that occurs after the formation of a carbanion intermediate. The proposed mechanism only accounts for the reaction from l-Ala to d-Ala.

In class A′ and U1Alr16, the carboxylate groups of Ala substrates displayed varying interactions with Arg139 and Lys39, which were previously known to be involved in substrate recognition and proton transfer, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S8a-d)3,4,9. Furthermore, the orientation of an Ala substrates that belong to class A′ (Data II) Ala was found to be similar to that of class B Ala. This suggests that Arg139 and Lys39 may also play a role in arranging Ala substrate for the racemase reaction (Figs. 1b-e and 2a-c). Tyr272′ catalyzes the deprotonation of the amine of l-Ala (Figs. 4, (2)), which promotes interactions between the deprotonated amine group of l-Ala and the C4A atom of PLP to form an external aldimine (PLP-Ala), as observed in class B (Figs. 4, (3)). Furthermore, for the racemase reaction, protonation occurs at the Cα atom of the Ala substrate via the catalytic Lys3945. This observation is consistent with previous reports that the Ala substrate forms an external aldimine with PLP and proton transfer to Cα atom of Ala is partially rate limiting46. Our structure analysis results strongly support the previously proposed mechanism22.

For the continuous racemase reaction of BsAlr, the protonated Tyr272′ and deprotonated Lys39 residues require deprotonation and protonation, respectively. Watanabe et al. suggested that the proton of the catalytic Tyr obtained from l-Ala is transferred to the catalytic Lys22. In the crystal structure of GsAlr, the distance between catalytic Tyr and Lys was 6 Å, indicating that direct proton transfer may not be possible. Proton transfer from Tyr to Lys may occur while rotating the carboxylate group of Ala (Fig. 3d)22. It has been proposed that the protonation states of the catalytic Tyr and Lys are equilibrated by the solvent46. While this could be possible, we did not observe any water molecules near Tyr272′ and Lys39 in class B BsAlr. Moreover, in class B, the carboxylate group of Ala was located within 3.5 Å of both Tyr272′ and Lys39. Thus, our structure proposes the possibility that without the carboxylate group rotation of Ala, the proton extracted by Tyr272′ can be transferred directly to this carboxylate group of Ala and then sequentially to Lys39.

Time-resolved SFX analysis is a powerful tool for understanding the ultrafast dynamics of enzyme movement during catalysis. However, this approach has many limitations, such as the preparation of substrate or intermediate analogs and the instrument setup in the beamline. Although the method presented here does not provide ultrafast snapshots, such as time-dependent XFEL and limitations in observing specific reactions or intermediate states with a single conformation of the substrate and protein, it has the advantage of obtaining possible intermediate structures without intermediate analogs or a difficult beamline setup. Therefore, we believe that data collection for nanocrystals in the presence of the substrate using a fixed-target method can be extended to elucidate the reaction mechanisms of other enzymes. The l-Ala from class A′ not only showed an orientation distinct from that of the l-Ala from class A but also exhibited different interactions with amino acids surrounding the active site. Therefore, the different positions of Ala observed in the various reaction states in this study could aid the design of Alr-based antibacterial agents.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the beamline staff at NCI beamline (2021-1st-NCI-021) at PAL-XFEL for their assistance with data collection; and Global Science experimental Data hub Center (GSDC) at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information (KISTI) for computational support. This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the korea government (MEST, No. 2021R1A2C301335711, RS-2024-00440289, and RS-2024-00344154 to Y.C. and NRF-2021R1I1A1A01050838 to K.H.N.) and the BK21 program (Ministry of Education) to Y.C. and J.K.

Author contributions

J.K. carried out protein expression, purification, and structure determination with the help of J.P.; J.K. carried out data collection with the help of K.L., J.P. and W.K.C.; J.K. curated the collected data with the help of K.H.N. and Y.C.; Y.C. designed the research; J.K., K.H.N. and Y.C. wrote the manuscript.; Y.C. edited the manuscript with the help of K.H.N.

Data availability

The coordinate and structure factors have been deposited with the PDB with accession codes 8ZPE (apo state of BsAlr), 8ZPF (reaction state of BsAlr, Data I), 8ZPG (reaction state of BsAlr, Data II), 8ZPH (reaction state of BsAlr, Data III), and 9JT7 (reaction state of BsAlr, 0–60 min).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ki Hyun Nam, Email: structure@kookmin.ac.kr.

Yunje Cho, Email: yunje@postech.ac.kr.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-83045-8.

References

- 1.Lam, H. et al. D-amino acids govern stationary phase cell wall remodeling in bacteria. Science325, 1552–1555. 10.1126/science.1178123 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh, C. T. Enzymes in the D-alanine branch of bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan assembly. J. Biol. Chem.264, 2393–2396. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)81624-1 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw, J. P., Petsko, G. A. & Ringe, D. Determination of the structure of alanine racemase from Bacillus stearothermophilus at 1.9-Å resolution. Biochemistry36, 1329–1342. 10.1021/bi961856c (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morollo, A. A., Petsko, G. A. & Ringe, D. Structure of a Michaelis complex analogue: propionate binds in the substrate carboxylate site of alanine racemase. Biochemistry38, 3293–3301. 10.1021/bi9822729 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambert, M. P. & Neuhaus, F. C. Mechanism of D-cycloserine action: alanine racemase from Escherichia coli W. J. Bacteriol.110, 978–987. 10.1128/jb.110.3.978-987.1972 (1972). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenn, T. D., Holyoak, T., Stamper, G. F. & Ringe, D. Effect of a Y265F mutant on the transamination-based cycloserine inactivation of alanine racemase. Biochemistry44, 5317–5327. 10.1021/bi047842l (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Chiara, C. et al. D-Cycloserine destruction by alanine racemase and the limit of irreversible inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol.16, 686–694. 10.1038/s41589-020-0498-9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson, A. C. The process of structure-based drug design. Chem. Biol.10, 787–797. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.09.002 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stamper, G. F., Morollo, A. A. & Ringe, D. Reaction of alanine racemase with 1-aminoethylphosphonic acid forms a stable external aldimine. Biochemistry37, 10438–10445. 10.1021/bi980692s (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noda, M., Matoba, Y., Kumagai, T. & Sugiyama, M. Structural evidence that alanine racemase from a D-cycloserine-producing microorganism exhibits resistance to its own product. J. Biol. Chem.279, 46153–46161. 10.1074/jbc.M404605200 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeMagueres, P. et al. The 1.9 A crystal structure of alanine racemase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis contains a conserved entryway into the active site. Biochemistry44, 1471–1481. 10.1021/bi0486583 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Au, K. et al. Structures of an alanine racemase from Bacillus anthracis (BA0252) in the presence and absence of (R)-1-aminoethylphosphonic acid (L-Ala-P). Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun.64, 327–333. 10.1107/S1744309108007252 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palani, K., Burley, S. K. & Swaminathan, S. Structure of alanine racemase from Oenococcus oeni with bound pyridoxal 5’-phosphate. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun.69, 15–19. 10.1107/S1744309112047276 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernardo-Garcia, N. et al. Cold-induced aldimine bond cleavage by Tris in Bacillus subtilis alanine racemase. Org. Biomol. Chem.17, 4350–4358. 10.1039/c9ob00223e (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeMagueres, P. et al. Crystal structure at 1.45 A resolution of alanine racemase from a pathogenic bacterium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, contains both internal and external aldimine forms. Biochemistry42, 14752–14761. 10.1021/bi030165v (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimizu-Ibuka, A. et al. Regulation of alanine racemase activity by carboxylates and the d-type substrate d-alanine. FEBS J.290, 2954–2967. 10.1111/febs.16745 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Priyadarshi, A. et al. Structural insights into the alanine racemase from Enterococcus faecalis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1794, 1030–1040. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.03.006 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Counago, R. M., Davlieva, M., Strych, U., Hill, R. E. & Krause, K. L. Biochemical and structural characterization of alanine racemase from Bacillus anthracis (Ames). BMC Struct. Biol.9, 53. 10.1186/1472-6807-9-53 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun, X. et al. Crystal structure of a thermostable alanine racemase from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis MB4 reveals the role of Gln360 in substrate selection. PLoS One. 10, e0133516. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133516 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong, H. et al. Structural features and kinetic characterization of alanine racemase from Bacillus pseudofirmus OF4. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.497, 139–145. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.02.041 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun, S. & Toney, M. D. Evidence for a two-base mechanism involving tyrosine-265 from arginine-219 mutants of alanine racemase. Biochemistry38, 4058–4065. 10.1021/bi982924t (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe, A. et al. Reaction mechanism of alanine racemase from Bacillus stearothermophilus: x-ray crystallographic studies of the enzyme bound with N-(5’-phosphopyridoxyl)alanine. J. Biol. Chem.277, 19166–19172. 10.1074/jbc.M201615200 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Major, D. T. & Gao, J. A combined quantum mechanical and molecular mechanical study of the reaction mechanism and α-amino acidity in alanine racemase. J. Am. Chem. Soc.128, 16345–16357. 10.1021/ja066334r (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapman, H. N. et al. Femtosecond X-ray protein nanocrystallography. Nature470, 73–77. 10.1038/nature09750 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fromme, P. XFELs open a new era in structural chemical biology. Nat. Chem. Biol.11, 895–899. 10.1038/nchembio.1968 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levantino, M., Yorke, B. A., Monteiro, D. C., Cammarata, M. & Pearson, A. R. Using synchrotrons and XFELs for time-resolved X-ray crystallography and solution scattering experiments on biomolecules. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol.35, 41–48. 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.07.017 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, J., Kim, Y., Park, J., Nam, K. H. & Cho, Y. Structural mechanism of Escherichia coli cyanase. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol.79, 1094–1108. 10.1107/S2059798323009609 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang, H. S. et al. Hard X-ray free-electron laser with femtosecond-scale timing jitter. Nat. Photonics. 11, 708–713. 10.1038/s41566-017-0029-8 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park, J., Kim, S., Nam, K. H., Kim, B. & Ko, I. S. Current status of the CXI beamline at the PAL-XFEL. J. Korean Phys. Soc.69, 1089–1093. 10.3938/jkps.69.1089 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim, J. et al. Focusing X-ray free-electron laser pulses using Kirkpatrick-Baez mirrors at the NCI hutch of the PAL-XFEL. J. Synchrotron Radiat.25, 289–292. 10.1107/S1600577517016186 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, D. et al. Nylon mesh-based sample holder for fixed-target serial femtosecond crystallography. Sci. Rep.9, 6971. 10.1038/s41598-019-43485-z (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mariani, V. et al. OnDA: online data analysis and feedback for serial X-ray imaging. J. Appl. Crystallogr.49, 1073–1080. 10.1107/s1600576716007469 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barty, A. et al. Cheetah: software for high-throughput reduction and analysis of serial femtosecond X-ray diffraction data. J. Appl. Crystallogr.47, 1118–1131. 10.1107/S1600576714007626 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White, T. A. Processing serial crystallography data with CrystFEL: a step-by-step guide. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol.75, 219–233. 10.1107/S205979831801238X (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Battye, T. G., Kontogiannis, L., Johnson, O., Powell, H. R. & Leslie, A. G. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr.67, 271–281. 10.1107/S0907444910048675 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gevorkov, Y. et al. XGANDALF - extended gradient descent algorithm for lattice finding. Acta Crystallogr. Found. Adv.75, 694–704. 10.1107/S2053273319010593 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr.40, 658–674. 10.1107/S0021889807021206 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr.60, 2126–2132. 10.1107/S0907444904019158 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liebschner, D. et al. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol.75, 861–877. 10.1107/S2059798319011471 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams, C. J. et al. More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 27. MolProbity, 293–315. 10.1002/pro.3330 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schrodinger, L. L. C. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8 (2015).

- 42.Wu, D. et al. Residues Asp164 and Glu165 at the substrate entryway function potently in substrate orientation of alanine racemase from E. coli: Enzymatic characterization with crystal structure analysis. Protein Sci.17, 1066–1076. 10.1110/ps.08349590 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watanabe, A. et al. Role of lysine 39 of alanine racemase from Bacillus stearothermophilus that binds pyridoxal 5’-phosphate. Chemical rescue studies of Lys39 → Ala mutant. J. Biol. Chem.274, 4189–4194. 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4189 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Im, H. et al. The crystal structure of alanine racemase from Streptococcus pneumoniae, a target for structure-based drug design. BMC Microbiol.11, 116. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-116 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ondrechen, M. J., Briggs, J. M. & McCammon, J. A. A model for enzyme-substrate interaction in alanine racemase. J. Am. Chem. Soc.123, 2830–2834. 10.1021/ja0029679 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spies, M. A., Woodward, J. J., Watnik, M. R. & Toney, M. D. Alanine racemase free energy profiles from global analyses of progress curves. J. Am. Chem. Soc.126, 7464–7475. 10.1021/ja049579h (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The coordinate and structure factors have been deposited with the PDB with accession codes 8ZPE (apo state of BsAlr), 8ZPF (reaction state of BsAlr, Data I), 8ZPG (reaction state of BsAlr, Data II), 8ZPH (reaction state of BsAlr, Data III), and 9JT7 (reaction state of BsAlr, 0–60 min).