Abstract

Surface electromyography (sEMG) data has been extensively utilized in deep learning algorithms for hand movement classification. This paper aims to introduce a novel method for hand gesture classification using sEMG data, addressing accuracy challenges seen in previous studies. We propose a U-Net architecture incorporating a MobileNetV2 encoder, enhanced by a novel Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) and metaheuristic optimization for spatial feature extraction in hand gesture and motion recognition. Bayesian optimization is employed as the metaheuristic approach to optimize the BiLSTM model’s architecture. To address the non-stationarity of sEMG signals, we employ a windowing strategy for signal augmentation within deep learning architectures. The MobileNetV2 encoder and U-Net architecture extract relevant features from sEMG spectrogram images. Edge computing integration is leveraged to further enhance innovation by enabling real-time processing and decision-making closer to the data source. Six standard databases were utilized, achieving an average accuracy of 90.23% with our proposed model, showcasing a 3–4% average accuracy improvement and a 10% variance reduction. Notably, Mendeley Data, BioPatRec DB3, and BioPatRec DB1 surpassed advanced models in their respective domains with classification accuracies of 88.71%, 90.2%, and 88.6%, respectively. Experimental results underscore the significant enhancement in generalizability and gesture recognition robustness. This approach offers a fresh perspective on prosthetic management and human-machine interaction, emphasizing its efficacy in improving accuracy and reducing variance for enhanced prosthetic control and interaction with machines through edge computing integration.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-82676-1.

Keywords: Hand Gesture, Edge computing, sEMG, BiLSTM, Bayesian optimization, MobileNetV2, U-Net

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Neuroscience, Health care, Medical research, Biomedical engineering, Electrical and electronic engineering

Introduction

Electromyographic (EMG) signals are a biomedical signal widely used for measuring the electrical potential changes in muscles1,2. These signals are generated when muscles contract, producing surface EMG (sEMG) signals. Unlike other methods of receiving vital signals from the body, sEMG signals can be recorded non-invasively using surface electrodes, making them a valuable tool for diagnosing abnormalities. EMG signals are relatively easy to process, which makes it possible to identify specific muscle, muscle-nerve, or joint diseases3. The applications of electromyographic signals are diverse and wide-ranging. They include but are not limited to controlling objects4,5, virtual reality6, virtual keyboards7, robotic arms8, prostheses9–11, wheelchair control12,13, developing and controlling human-computer interfaces14, sports activities and care, ergonomics, biofeedback, sports medicine, and physiotherapy15. Neuroengineering has emerged as a promising approach for determining the intentionality behind voluntary upper limb movements. The development of future wearable hand robots is expected to incorporate sEMG-based motion intention detection technologies, thereby enabling intelligent user-controlled functional movement training. This approach presents distinct advantages in assisting stroke victims’ recovery by facilitating targeted rehabilitation16. The use of upper-limb prostheses17–19 and rehabilitation exoskeletons19–21 demonstrates the therapeutic significance of this technology, particularly for patients with limited mobility. In recent years, the availability of cost-effective sensor devices such as the Myo armband has spurred applied research in this domain, with high user compliance reported22. The early prediction of motion intention at the beginning of motion has not received sufficient attention in prior studies in comparison to other related areas of research. However, the ability to anticipate outcomes at an early stage is of great importance in many rehabilitative and assistive environments. In study23, it was suggested that the control of a prosthesis should commence predicting the user’s intention to move within 100 to 150 ms after the onset of sEMG activity. Additionally, another study24 demonstrated that the Gaussian mixture model (GMM) accurately predicted the forward and backward motion of the upper limbs 100ms before the initiation of motion.

To accurately anticipate the intention to move, one must have a deep understanding of the sEMG patterns both during rest and in the initial stages of movement. Nevertheless, the complex and fluctuating nature of these sEMG systems needs to be adequately considered. Our research paper introduces a novel hybrid deep learning methodology for classifying gestures and movements of the upper body, specifically the hands, using windowed surface electromyography (sEMG) signals. The duration of the windowing period plays a significant role in determining the speed at which the body’s skeletal system transitions from a resting state to selectively activating individual muscle units. To tackle the non-stationary challenge that arises from this phenomenon, we adopted an augmentation strategy whereby windowing and overlapping between consecutive sEMG signals were performed to increase the number of signals in the deep learning architecture. Furthermore, we generated a spectrogram from each windowed signal to be used as an input image for the deep learning network. The present study investigates the efficacy of U-Net architecture by utilizing spatial features and combining other convolutional neural networks. MobileNetV2 serves as the encoding component of our proposed paradigm. Furthermore, we introduce an improved version of the Bidirectional Long-Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) technique for retrieving temporal features. The use of hybrid models across multiple datasets enhances generalizability, which in turn improves movement and gesture detection and classification. The average accuracy of all sEMG signal types is satisfactory, even with a limited number of channels.

The data collected in this study are dependable and showcase computational efficiency. To bridge the gap between computational capabilities and data collection, edge computing25 was employed to support the sEMG processing of the movement. The placement of computing resources near the network’s edge offers several advantages, including enhanced application performance, reduced data transit expenses, and the ability to manage escalating public cloud expenses. As a result of this study, we have made significant contributions in the field, which include:

The proposed technique utilizes windowing of sEMG signals to accurately classify hand movements and gestures. This simplified approach facilitates rapid and precise identification with minimal computational complexity. Spatial characteristics are extracted using the U-Net framework and MobileNetV2 encoder, while a more sophisticated version of the Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) technique is employed to capture temporal features. Additionally, the sliding window strategy26,27, a commonly used method for data augmentation in EMG classification tasks, enhances the robustness and effectiveness of the classification model.

The approach efficiently and reliably assesses different motions using a rapid classification model. Refining the classification model highlights the synergistic impact of Bayesian optimization and BiLSTM. Bayesian optimization significantly improves the efficiency of hyperparameter tuning, ensuring an optimal configuration is reached with fewer iterations, while BiLSTM enriches the model’s sequence modeling capabilities, enabling it to capture intricate temporal dependencies within the data adeptly. Combining these techniques results in a more effective and tailored hand gesture and motion recognition classification model.

The proposed method’s application to sEMG analysis for gesture recognition can benefit a variety of classes. Through advanced techniques, deep learning can overcome the challenges associated with gesture recognition in the past. The revised model significantly strengthens the fundamental decision-making framework, with enhanced classification accuracy and streamlined computation serving as two indicators of system robustness.

We integrated edge computing into our research, marking a significant advancement that enables real-time processing and decision-making closer to the data source. This integration optimizes resources, reduces latency, and sets a new standard for efficient hand gesture classification and prosthetic management.

The proposed network combines U-Net, MobileNetV2, and BiLSTM, each chosen for its specific strengths in addressing the challenges of sEMG-based gesture recognition. U-Net was selected for its proven capability in spatial feature extraction, particularly in time-frequency domain problems like those arising from sEMG spectrograms. Its encoder-decoder structure effectively captures fine-grained spatial information, ensuring precise representation of gesture patterns. MobileNetV2 was integrated for its lightweight design and computational efficiency, making it highly suitable for real-time applications on edge computing platforms. Its depthwise separable convolutions provide a balance between performance and resource constraints. Furthermore, BiLSTM was employed to model the inherent temporal dependencies in sEMG signals, capturing both past and future contexts, which is crucial for distinguishing between similar gestures.

The paper’s substantive content is discussed in the following sections. "Related work" Section presents the literature review, while "Methodology" Sect. examines the suggested paradigm in greater detail. Datasets, results, and critical notes are presented in "Experiments" Sect., while "Discussion" Sect. contains the debate segment. Further research is suggested based on the findings of the inquiry.

Related work

The gesture and hand’s movement identification field has made considerable progress using sEMG signals. Integrating deep learning and other popular methodologies, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), has significantly expanded the scope of class analysis, enabling the analysis of a broader range of classes than previously possible. Previous studies that utilized sEMG signals to analyze hand motions and gestures employed a diverse range of deep structures, including CNNs27,28, Deep Belief Networks (DBNs)29,30, Transfer Learning (TL)31–34, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)35,36, and Adversarial Learning (AL)37,38. Gautam et al.39 developed a deep learning framework, the Low-Complex Movement Recognition-Net, specifically designed to recognize wrist and finger flexion, grasping and functional movements, and force patterns based on single channel sEMG recordings. The proposed model has shown an average classification accuracy improvement of 8.5%, surpassing both the Twin-Support Vector Machine and previous CNN-based models with an accuracy of 16.0%. Nasri et al.40 proposed a novel three-dimensional game controlled by sEMG using a deep learning-based architecture. The main objective of their study was to develop a 3D gaming experience that could be easily manipulated with inexpensive sEMG sensors, thereby enabling individuals with disabilities to access the game. The proposed deep learning model was developed using data from seven recorded movements captured using the Myo armband. The Convolutional Gated Recurrent Unit (Conv-GRU) architecture was utilized to classify gestures.

Similarly, Yu et al.41 proposed a transfer learning method that relies on CNNs to improve the overall ability of the target network to generalize. To evaluate the efficacy of their approach, the authors employed CapgMyo and NinaPro DB1 datasets. The model achieved a notable improvement in identification accuracy by employing a maximum of three iterations of a gesture. There was an 18.7% increase in accurately recognizing the original subject and an 8.7% increase in recognizing the original gesture. Su et al.42 proposed a deep multi-parallel CNN method to detect gestures using sEMG signals. The experimental results demonstrate that this approach outperforms five baseline machine learning methodologies, indicating the superiority of the recommended strategy. Another study by Tsinganos et al.43 employed Hilbert space-filling curves to represent sEMG signals in a way that enables the utilization of conventional image processing pipelines such as convolutional neural networks. The experimental results show that this methodology significantly improves the categorization accuracy. Tyacke et al.44 proposed a novel design for dilated efficient capsular neural networks using transfer learning. By utilizing only, the transient phase of the sEMG signals instead of the entirety of the signals, the size of the training samples can be reduced to just 20% of their original volume. The efficacy of this approach is confirmed by including varying amounts of individual training data. Furthermore, Xu et al.45 suggested a recurrent CNN that utilizes concatenated feature fusion was proposed. The experiments were conducted on three different NinaPro sEMG benchmark databases, namely DB4, DB2, and DB1. The model obtained impressive accuracies of 99.29%, 99.51%, and 88.87% for DB4, DB2, and DB1, respectively. In the study by Wang et al.46, two contemporary methods were developed and evaluated for representing images using traditional feature extraction techniques. Deformable convolutional networks were employed to detect hidden connections across channels using sparse multichannel sEMG data. The proposed methodologies were tested on the Ninapro-DB1 dataset, which consisted of three different sets of hand motions, each differing in kind and quantity. The deformable convolutional network outperformed normal CNNs by 4.9%, 2.6%, and 1.1%, respectively. In another study by Karnam et al.47, a hybrid architecture called EMGHandNet, which combined CNN and Bi-LSTM networks, was proposed. This design encoded the inter-channel and temporal correlations of sEMG signals to classify hand activity. Initially, CNN layers were utilized to extract profound characteristics from sEMG inputs. The Bi-LSTM was subsequently utilized to extract both forward and backward sequential information from these feature maps. Consequently, the proposed model developed a comprehensive understanding of both inter-channel and bidirectional temporal information. The proposed model was evaluated on multiple datasets, including UCI Gesture and NinaPro DB1, DB2, and DB4. The classification accuracy is as follows: UCI Gesture − 95.77%, NinaPro DB4–95.9%, NinaPro DB2–91.65%, and NinaPro DB1–98.33%. Ozdemir et al.48 aimed to enhance the identification accuracy of hand gestures using a dataset of 20 recorded motions, which consisted of sEMG and inertial information. The researchers evaluated several deep learning models, including the conventional Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), and Transformer models. The CNN and RNN models achieved test accuracy of over 95%, while the Transformer model exhibited comparatively lower accuracy of 71.6%. However, by improving the Transformer module’s performance, the identification accuracy was significantly increased from 71.86 to 98.96%. Another study by Fatayer et al.49 proposed a novel technique for detecting gestures by creating a fused map image to improve the spectrum information of the sparse sEMG signals. The authors suggested a data-centric strategy for addressing label noise, which involved refining misclassified samples and enhancing the CNN model. Accuracy rates for NinaPro DB3, DB7, and DB2 were 85.58%, 95.85%, and 95.50%, respectively. Liu et al.50 presented an effective approach for predicting dynamic hand gestures accurately and efficiently using a sEMG sensor. They utilized a wearable sEMG sensor to collect multi-channel sEMG signals during dynamic hand movements and proposed continuous wavelet transformation as a preprocessing technique to generate time-frequency maps from the collected data. To create a robust time-frequency map prediction model, they developed a deep residual attention network, which takes advantage of deep convolutional neural networks’ impressive ability to encode contextual features well. This residual attention network served as a crucial central node that extracted crucial spatial and channel information from multi-channel sEMG data for efficient feature representation. Also, Mahboob et al.51 showcased a 3D hand motion prediction application using sEMG signal and optical hand tracking data. They developed a transformer-encoder classifier module that forecasts 3D hand movements based on sEMG data, and created a test environment to collect, train, and predict three-dimensional hand movements within a realistic performance range. Li et al.52 proposed a deep network dubbed DeepTPA-Net for identifying hand gestures utilizing multi-channel sEMG data. DeepTPA-Net employed a ResNet50 network as an automated feature extractor for hand gesture detection. It also incorporated a new triple attention block connecting channel attention, temporal, and spatial units concurrently. The efficiency of DeepTPA-Net was assessed using five distinct benchmark sEMG hand gesture datasets.

Prabhavathy et al.53 suggested a method to extract local and global properties from sEMG signals to improve hand motion classification. They split their model into two segments to enhance gesture detection reliability, each extracting global and local data independently. These segments were then merged to form a unified model. Across five datasets, the recommended model had an average accuracy of 88.34%. Compared to models with the same number of parameters, this resulted in an average accuracy improvement of 9.96% and a decrease in variance of 50%. Moreover, the categorization accuracy rates were 88.6% for Mendeley Data, 91.0% for BioPatRec DB3, and 91.4% for BioPatRec DB1. Fang et al.54 have proposed a new system for accurately identifying hand motions. The system uses a multi-modality deep forest design integrating sEMG and acceleration signals. It consists of three steps: feature extraction from sEMG and acceleration signals, dimension reduction of features, and classification using a cascade structure deep forest. The system was tested using Ninapro DB7, which was more accurate than its competitors. Another study11 used sEMG to develop a multi-attention deep learning architecture with multi-view for hand gesture identification. The study tested the approach using Ninapro DB5, myoUp, and myo datasets. The study achieved high accuracy rates of 97.0%, 97.86%, and 99.27%, respectively. The study of early prediction of gesture pose of hand and motion intention during motion initiation has received less attention. However, it is more desirable to make predictions at an early stage in several assistive and rehabilitation scenarios. Patterns in the shortest possible timeframe can be detected using the sliding window technique with an overlapping windowing strategy26,27 to divide the sEMG signals into smaller pieces, aiming for real-time muscle activity and hand gesture pose classification. This paper examines the potential for significant underlying features to evaluate the unpredictability and dynamic nature of sEMG data acquired during various functional activities. The result is more accurate and consistent categorizations.

The field of hand gesture classification using sEMG signals has seen notable advancements, but several shortcomings persist in existing methodologies. Prior approaches often struggle with accuracy challenges due to the complexity and variability of hand movements, limiting their effectiveness in real-world applications. Additionally, many methods lack robustness when faced with non-stationary sEMG signals, which can introduce noise and inconsistencies in classification results. Furthermore, some techniques may not fully leverage the available data sources, leading to suboptimal performance in capturing the intricate patterns of hand gestures. Despite these limitations, various deep learning architectures, including CNNs, RNNs, and Transfer Learning, have been explored to improve classification accuracy. In our study, we propose a novel approach for hand gesture classification based on BiLSTM-Metaheuristic Optimization and Hybrid U-Net-MobileNetV2 Encoder Architecture. Our method addresses the shortcomings of previous techniques by leveraging the strengths of BiLSTM for capturing temporal dependencies in sEMG signals and metaheuristic optimization for refining model parameters. The integration of a Hybrid U-Net-MobileNetV2 Encoder Architecture enhances feature extraction from sEMG spectrogram images, enabling more comprehensive representation of hand gestures. By combining these components, our approach achieves superior accuracy in classifying hand gestures compared to existing methods. Moreover, our method demonstrates robustness to non-stationary sEMG signals, thanks to the optimized architecture and effective feature extraction process.

Methodology

The proposed model aims to match current solutions for recognizing gestures and hand movements during motion analysis and prosthesis design using sEMG signals, while leveraging the benefits of edge computing. Our methodology is compared to the current state-of-the-art to streamline the computational process for use in regulatory devices. Incorporating edge computing (see Fig. 1) into our approach enables real-time processing and decision-making closer to the data source, enhancing efficiency and reducing latency.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the proposed method for gesture classification using sEMG signals on an edge computing platform.

This method involves two sequential steps: Time-distributed U-Nets or spatial feature extraction techniques to extract the temporal information, and then categorizing the extracted information. The integration of edge computing optimizes computational resources and sets a new standard for efficient hand gesture classification and prosthetic management. Bayesian optimization is credited for enhancing the efficiency of hyperparameter tuning, which leads to faster convergence to an optimal configuration. Moreover, BiLSTM enhances the model’s sequence modeling capabilities by capturing complex temporal dependencies. This is crucial in tasks like hand gesture and motion recognition, where the order and timing of movements matter.

Spectrogram generation through short-time fourier transform (STFT)

The windowing approach is a technique used to address non-stationarity in sEMG signals. In this approach, the signal is divided into overlapping windows, and a CNN process is applied to each window, resulting in a more accurate signal estimation. Using the windowing strategy is an effective method to combat the non-stationarity of sEMG signals. In this approach, long sEMG signals are divided into smaller segments or windows, each typically containing a limited number of samples of the signal. By varying the size and location of these windows, we can utilize different temporal and frequency features of the signal over time. This enables us to extract various temporal and frequency information from the signals and use them as input features for deep learning models. Thus, by adjusting the scale and location of the windows to cover different backgrounds of the signal better, we can manage the non-stationarity present in sEMG signals and enhance the accuracy and efficiency of deep learning models.

Additionally, the windowing approach reduces the number of features, making the signal more interpretable and easier to analyze. In our work, we have used the Short Time Fourier Transform (STFT) algorithm to generate spectrograms on windowed data. The signal x(t) is modified by the moving window function g(t) at time τ, which then alters the signal g(t). To the x(t) data within the window at discrete time intervals τ, a finite-time Fourier transform is applied. After modifying the window size along the time axis by a factor of τ, a Fourier transform can be applied. During Fourier transformation, the whole signal is transformed. STFT signals are captured within a certain time interval by two-dimensional time-frequency displays. By using the STFT method, it is possible to visualize the signal’s frequency characteristics as they change over time.

Algorithm 1 Computational steps for spectral analysis using the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT).

Algorithm 1.

Short Time Fourier Transform (STFT).

Algorithm 1 outlines a step-by-step process for implementing the STFT to analyze spectral the signals. Figure 2 shows three windowed signal samples, along with their spectrograms.

| 1 |

Fig. 2.

Three windowed signal samples (top row) and their corresponding spectrograms (bottom row).

If the window size remains constant, the frequency-time separation remains consistent over the whole frequency-time plane, regardless of the function g(t). Optimal selection of window size for the STFT approach becomes challenging when the signal contains both high- and low-frequency components. The number of windows may vary depending on accuracy levels.

Spatial feature extraction using MobileNetV2 and U-Net architectures

After the generation of windowed spectrograms of sEMG signals, The U-Net architecture is utilized to acquire spatial features. Figure 3 shows the process of extracting spatial features of a single spectrogram from a sequential temporal distribution. MobileNetV2 is used as an encoder within the U-Net architecture for this purpose. The spatial information extracted is used to categorize sEMG signals.

Fig. 3.

Graphical structures of MobileNetV2 and U-Net. The green elements represent the feature maps extracted by MobileNetV2, utilized by both the encoder and decoder components.

BiLSTM structure

Bayesian Optimization is an efficient method for finding the best hyperparameters for a model. It searches the hyperparameter space intelligently, leading to faster convergence to optimal configurations. When training deep learning models like LSTM or BiLSTM, tuning hyperparameters manually or using other optimization methods is common. However, this can be time-consuming and less effective in finding the best configurations. For tasks involving sEMG signal-based hand gesture recognition, the combination of BiLSTM and Bayesian Optimization is advantageous. This is particularly true when the data exhibits intricate temporal dependencies and complex sequential patterns. The bidirectional nature of BiLSTM and the smart exploration of hyperparameter space by Bayesian Optimization can contribute to improved model performance compared to using LSTM alone, especially in scenarios with limited or noisy data. Experimenting and validating this approach on specific datasets is essential to assess its efficacy for hand gesture recognition tasks. BiLSTM can capture both past and future dependencies in sequential data, which is beneficial in understanding the temporal dynamics of hand gestures. This is crucial in recognizing gestures where the order and timing of movements matter. While LSTM can capture past dependencies, it may not perform as well in tasks requiring future information consideration. The BiLSTM network incorporates three “gates” - the input gate (it), the forget gate (ft), and the output gate (ot) - to effectively control data flow. In order to effectively handle the deletion of a large volume of data at the last moment, we can employ the forget gate, denoted as ft:

| 2 |

The input gate or it regulates the quantity of data that requires immediate storage.

| 3 |

The current number of neurons that need to be sent to the next neuron is regulated by the output gate, ot.

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

The weight matrix is denoted as W(·), ht−1 represents the previous output of the network, ht represents the current final output of the network, and Ct represents the internal variable of the LSTM network that stores data up to the current instant. At this same time, the candidate state is denoted by the letter  . The input is represented by xt, the bias term is denoted as b(·), the logistic function is represented by σ(·), and the activation function is tanh(·).

. The input is represented by xt, the bias term is denoted as b(·), the logistic function is represented by σ(·), and the activation function is tanh(·).

| 8 |

| 9 |

At time t, a LSTM cell receives three inputs: the previous time’s result (ht−1), the current state of the cell (Ct−1), and the value of the network input (xt). The cell can perform its functions with the assistance of these three inputs. At any given moment, the cell produces two outputs: the ht output value and the current cell state, denoted as Ct.

BiLSTM hyperparameter optimization

The probability density function p(f(x)|x) for a hyperparameter optimization function f(x) assumes a normal distribution, given that a Gaussian distribution is assumed. Bayesian optimization uses Gaussian process regression to model the present N sets of test outcomes, denoted H = {xn, yn}Nn=1. Next, it calculates the posterior distribution of p(f(x)|x, H) for the function f(x) and takes yn as the observed value of f(xn). This process is repeated until the ideal hyperparameters for the LSTM neural network are discovered. As shown in Algorithm 2, a step-by-step procedure is provided for applying Bayesian optimization. Both the initial learning rate and the number of LSTM cells directly impact the network’s categorization performance.

Algorithm 2 Steps of the Bayesian optimization process for fine-tuning the BiLSTM architecture.

Algorithm 2.

Bayesian Learning with Bayesian LSTM (BILSTM).

Through Bayesian optimization, the BiLSTM network is capable of finding its ideal values for the initial learning rate and the number of hidden cells in the LSTM layer. Bayesian optimization often utilizes the Expected Improvement function (EIf), also known as (10), as its objective function. Adjusting the model’s hyperparameters can further enhance performance.

| 10 |

Bayesian optimization is a technique for optimally selecting machine learning model architectures. It relies on probabilistic models and can be particularly effective for complex models like BiLSTM networks. This technique involves selecting a set of hyperparameters iteratively, evaluating the model’s performance, updating a probabilistic model of the objective function, and then selecting the next set of hyperparameters to evaluate. As shown in Fig. 4, to enhance the accuracy of sEMG-based hand gesture recognition, Bayesian optimization was employed to fine-tune the key hyperparameters of the BiLSTM model, specifically the initial learning rate and the number of hidden neurons.

Fig. 4.

This process diagram illustrates the step-by-step process of optimizing BiLSTM hyperparameters.

The following steps outline the optimization process:

-

Initialization.

- We began by setting an initial search space for the hyperparameters. The learning rate was set within a range of [0.0001,0.01], and the number of hidden neurons was limited to values between 64 and 256.

- Random samples from this range were used to initialize the Gaussian process model, which serves as the surrogate model for Bayesian optimization.

-

Hyperparameter search using EI.

- Bayesian optimization utilized the EI acquisition function, which selects the hyperparameter values that are most likely to improve model performance based on previous iterations.

- At each iteration, EI evaluated combinations of the learning rate and hidden neurons, balancing exploration of new areas and exploitation of known high-performing regions. This balance ensures efficient and comprehensive coverage of the hyperparameter space.

-

Iterative process and convergence.

- The optimization process was conducted over 20 iterations, allowing the acquisition function to refine its search with each new evaluation of model performance.

- At each step, the acquisition function selected a new set of hyperparameters, which was then evaluated on a validation subset of the sEMG dataset. The process continued until the convergence criteria, defined as a lack of significant improvement over five consecutive iterations, was met.

-

Final configuration.

- After iterative adjustments, the Bayesian optimization process identified an optimal learning rate of 0.001 and 128 hidden neurons for the BiLSTM model, which provided a strong balance between training efficiency and accuracy.

Experiments

The validity of the assessment is intrinsically linked to the outcome of the study methodology implemented in the specific framework. After comprehensively evaluating the principal criteria, we present a summary of scrutinized datasets.

Dataset

Multiple sets of electromyogram signals were used to evaluate a method, with details of the databases provided below. Ninapro DB455 recorded muscle activity signals using 12 Cometa-activated single-differential wireless electrodes. Eight electrodes were distributed evenly down the forearm, aligned with the brachioradialis joint. Two electrodes were placed at the primary points of finger bending and straightening, and two electrodes were located on the prominent tendons of the biceps and triceps, the primary sites of movement. The database information is based on 52 gesture motions and a rest condition completed by ten individuals. The sEMG signals were collected at a frequency of 2 kHz, and each movement was repeated six times.

Thalmic Myo armbands collected muscle activity signals using 16 active single-differential wireless electrodes. The Ninapro DB5 database55 recorded these signals. The primary sensor was located at the humeral joint, while the first armband was worn near the elbow. The second armband was nearer to the hand and had a 22.5-degree inclination relative to the first. EEG and EM signals were sampled at 200 Hz. While one participant remained at rest, ten people executed 52 gesture motions. In each exercise, there were six repetitions.

The BioPatRec suite includes three databases: BioPatRec DB1, DB2, and DB356. BioPatRec DB1 and DB3 recorded ten hand gestures using four sEMG electrodes, while BioPatRec DB2 used eight sEMG electrodes to record 26 hand movements. The sEMG signals were recorded from subjects aged 20, 17, and 8. During the experiment, subjects rested for three seconds between repetitions, and a sampling rate of 2000 Hz was used. The contraction time percentage, which determines the length of the contraction, is set to 0.7 by default. There is a distance of 2 cm between the electrodes of the dipole, and over the proximal forearm region, electrodes are evenly distributed.

The Mendeley Data source48 contained four-channel sEMG recordings of ten unique hand motions. A BIOPAC MP36 device equipped with Ag/AgCl surface bipolar electrodes recorded data at a sampling frequency of 2000 Hz. Each subject performed hand motions ten times during five cycles, separated by a 30-second interval. A four-second interval between each set of hand movements during each cycle lasted 104 s. Detailed information about the datasets used is given in Table 1. During both the testing and training phases57,58, multiple trials address any disparities in data distribution between training and test sets. Trials 1, 3 and 6 from all ten people were compiled into the Ninapro DB4 dataset for training. A total of two trials were selected for testing.

Table 1.

Summary of datasets utilized in the study, including their key characteristics and specifications.

| Dataset | Sampling rate | Trails for training | Trails for testing | No. training | Number of sEMG channels | Intact subjects | No. gestures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mendeley data | 2000 Hz | 1,2,4 | 3,5 | 5 | 4 | 40 | 10 |

| BioPatRec DB1 | 2000 Hz | 1,3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 20 | 10 |

| BioPatRec DB2 | 2000 Hz | 1,3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 17 | 26 |

| BioPatRec DB3 | 2000 Hz | 1,3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 10 |

| NinaPro DB5 | 200 Hz | 1,3,4,6 | 2,5 | 6 | 16 | 10 | 53 |

| NinaPro DB4 | 2000 Hz | 1,3,4,6 | 2,5 | 6 | 12 | 10 | 53 |

Experimental setup

The computer system used a single Intel® CoreTM i5-8500 CPU with 16 GB of RAM, which satisfied the storage and computational requirements. An additional 16 GB of RAM was also included on a solid-state drive (SSD) as a backup. The U-Net extractor has 1,907,041 parameters in its temporal distribution, with output forms of 30, 64, 64, and 1. The BiLSTM architecture has 128 different output forms and 2,163,200 parameters. The dense layers have output forms and parameter counts of 32 and 2 and 4128 and 62, respectively. The spectrogram images were converted to JPG format and resized to 448 × 448 dimensions. The model’s ability to accurately classify gestures was assessed, revealing a total of 4,056,236 parameters. Experimental results demonstrate the model’s efficiency and speed. The study employed five cross-validation techniques.

Various detection algorithms can be developed based on the system’s ability to recognize gestures and movements. The provided data set allows for a direct comparison between the factors and labels and the display of a confusion matrix. Non-target classes of hand movement were used to estimate the target and classify the spectrogram images based on the integrated deep model structure. The initial learning rate for the Adam optimizer was set to 0.001, and the network was trained for 500 epochs. The n_fft value for STFT is set to 1024. This value is used as the window size for the Fourier transform to maintain the required accuracy and resolution in the analysis of sEMG signals. Additionally, the hop length value for STFT is set to 512. This value determines the overlap of the windows, helping to maintain a balance between temporal and frequency accuracy. The K-fold methodology was used in the data-splitting process to evaluate the model’s overall effectiveness, in addition to a confusion matrix in the categorizing process.

Evaluations

The following section summarizes the results of the classification phase, which involved recognizing gestures using sEMG data. The term ‘noise entrance’ or ‘noise level’ refers to the extent to which EMG signals are affected by external factors, such as electrical noise, motion artifacts, or other sources of interference. Essentially, a higher noise level indicates greater distortion or reduced reliability of the EMG signals for precise classification. This insight aids in evaluating the resilience and efficiency of classification models across varying degrees of noise interference. Table 2 presents the performance evaluation of different categories, including classification, moderate noise entrance, high noise entrance, and severe noise entrance, using a combined technique. For this study, a range of sEMG data was analyzed, representing a five-fold cross-validation. Based on the proposed methodology, there was a 5% increase in classification precision.

Table 2.

Comparison of gesture classification results based on sEMG data across different methods.

| Dataset | Method | ≈ 50–100 | ≈ 100–150 | ≈ 150–200 | ≈ 200–250 | ≈ 250–300 | ≈ 300–350 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Min | Max | Min | Max | Min | Max | Min | Max | Min | Max | ||

| Mendeley | CNN | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| U-Net with MobileNet V2 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.14 | |

| U-Net with MobileNet V2 and optBiLSTM | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | |

| NinaPro DB1 | U-Net | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| U-Net with MobileNet V2 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.10 | |

| U-Net with MobileNet V2 and optBiLSTM | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.10 | |

| NinaPro DB2 | CNN | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.13 |

| U-Net with MobileNet V2 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.12 | |

| U-Net with MobileNet V2 and optBiLSTM | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.11 | |

| BioPatRec DB1 | CNN | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 |

| U-Net with MobileNet V2 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.11 | |

| U-Net with MobileNet V2 and optBiLSTM | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.10 | |

| BioPatRec DB2 | CNN | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.15 |

| U-Net with MobileNet V2 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.14 | |

| U-Net with MobileNet V2 and optBiLSTM | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.14 | |

| BioPatRec DB3 | CNN | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| U-Net with MobileNet V2 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.15 | |

| U-Net with MobileNet V2 and optBiLSTM | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.14 | |

Significant values are in bold.

In this study, we conducted a comparative analysis of the efficiency of various databases, including NinaPro DB1, BioPatRec DB1, BioPatRec DB2, and Mendeley Data. The window lengths analyzed ranged from 50 milliseconds to 300 milliseconds. Classification errors according to window sizes are presented in Table 2, while Table 3 provides examples of classification accuracy based on repeated K-fold cross-validations of hand movement and gesture recognition models under different settings. Due to the extracted features from sEMG signals, accuracy distributions are homogeneous. Our approach exhibits high stability and robustness when dealing with various motions and manual gestures. The method has a classification accuracy of 92% or higher and can detect subtle movements previously difficult to detect. Additionally, it provides a cost-effective and efficient method of analyzing sEMG signals.

Table 3.

Classification performance of hand movement and gesture recognition models under varying noise levels in EMG signals.

| Dataset | K-fold | Low noise level | Moderate noise level | High noise level | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | U-Net with MobileNet V2 | U-Net with MobileNet V2 and optBiLSTM | CNN | U-Net with MobileNet V2 | U-Net with MobileNet V2 and optBiLSTM | CNN | U-Net with MobileNet V2 | U-Net with MobileNet V2 and optBiLSTM | ||

| NinaPro DB1 | 5-fold (1) | 90.54 | 92.03 | 93.11 | 84.35 | 87.27 | 92.15 | 82.11 | 85.13 | 90.87 |

| 5-fold (2) | 90.48 | 92.34 | 92.85 | 84.76 | 87.21 | 91.98 | 82.36 | 85.24 | 91.23 | |

| 5-fold (3) | 90.24 | 92.14 | 92.88 | 84.90 | 87.45 | 92.13 | 82.44 | 84.11 | 90.90 | |

| 5-fold (4) | 91.25 | 91.85 | 92.70 | 28.28 | 87.73 | 92.10 | 82.67 | 84.06 | 90.81 | |

| 5-fold (5) | 90.32 | 91.47 | 93.02 | 85.18 | 86.82 | 92.22 | 82.02 | 85.23 | 90.73 | |

| NinaPro DB2 | 5-fold (1) | 88.45 | 89.68 | 91.45 | 85.66 | 86.65 | 90.11 | 82.94 | 86.30 | 89.36 |

| 5-fold (2) | 88.38 | 89.88 | 91.58 | 85.69 | 87.55 | 90.05 | 82.13 | 84.26 | 89.14 | |

| 5-fold (3) | 88.21 | 89.29 | 91.78 | 85.29 | 86.44 | 90.18 | 81.87 | 85.23 | 89.25 | |

| 5-fold (4) | 88.23 | 89.53 | 91.40 | 85.16 | 86.96 | 90.09 | 82.74 | 84.37 | 89.12 | |

| 5-fold (5) | 88.26 | 89.64 | 91.52 | 83.76 | 87.15 | 90.06 | 82.18 | 84.96 | 89.35 | |

| BioPatRec DB1 | 5-fold (1) | 87.63 | 89.42 | 90.78 | 84.03 | 86.25 | 89.46 | 82.05 | 84.16 | 88.52 |

| 5-fold (2) | 87.68 | 89.03 | 90.52 | 83.29 | 85.76 | 89.31 | 82.03 | 84.27 | 88.48 | |

| 5-fold (3) | 87.26 | 89.30 | 90.67 | 84.08 | 85.29 | 89.24 | 82.74 | 84.59 | 88.29 | |

| 5-fold (4) | 87.17 | 88.75 | 90.91 | 84.20 | 85.69 | 89.53 | 81.90 | 84.65 | 88.43 | |

| 5-fold (5) | 87.27 | 89.06 | 90.82 | 83.26 | 85.22 | 89.36 | 82.38 | 84.06 | 88.21 | |

| BioPatRec DB2 | 5-fold (1) | 86.76 | 87.16 | 90.12 | 83.75 | 86.44 | 89.03 | 83.01 | 84.58 | 87.84 |

| 5-fold (2) | 87.38 | 88.50 | 90.14 | 84.24 | 85.45 | 88.75 | 82.54 | 84.92 | 87.29 | |

| 5-fold (3) | 87.35 | 88.30 | 90.28 | 84.59 | 86.71 | 88.82 | 82.86 | 84.19 | 87.26 | |

| 5-fold (4) | 86.50 | 88.38 | 90.34 | 84.36 | 85.88 | 88.56 | 82.07 | 83.33 | 87.40 | |

| 5-fold (5) | 86.26 | 88.24 | 90.23 | 83.63 | 85.04 | 88.60 | 82.95 | 87.74 | 87.56 | |

| BioPatRec DB3 | 5-fold (1) | 86.63 | 87.28 | 89.26 | 84.06 | 85.09 | 87.80 | 82.45 | 84.32 | 86.96 |

| 5-fold (2) | 86.13 | 87.49 | 89.17 | 84.13 | 85.51 | 88.06 | 82.86 | 84.32 | 87.14 | |

| 5-fold (3) | 86.97 | 88.02 | 89.48 | 84.47 | 85.71 | 88.01 | 82.73 | 84.85 | 86.83 | |

| 5-fold (4) | 86.11 | 87.81 | 89.46 | 83.62 | 84.22 | 87.91 | 82.12 | 83.96 | 86.60 | |

| 5-fold (5) | 85.95 | 87.51 | 89.32 | 84.16 | 85.82 | 88.10 | 81.98 | 84.58 | 86.84 | |

| Mendeley data | 5-fold (1) | 86.74 | 87.66 | 90.35 | 84.60 | 86.27 | 89.03 | 82.28 | 84.27 | 87.95 |

| 5-fold (2) | 86.39 | 86.85 | 90.56 | 83.49 | 85.11 | 89.17 | 82.79 | 85.12 | 88.09 | |

| 5-fold (3) | 86.19 | 87.13 | 90.21 | 83.55 | 85.40 | 89.25 | 81.45 | 84.17 | 87.65 | |

| 5-fold (4) | 86.42 | 87.91 | 90.28 | 83.65 | 85.58 | 89.47 | 84.56 | 87.38 | 87.73 | |

| 5-fold (5) | 86.06 | 86.96 | 90.44 | 84.53 | 85.66 | 89.05 | 82.19 | 83.29 | 87.97 | |

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the findings of the tests conducted to validate the efficacy of our proposed strategy. The performance evaluation was conducted using K-fold cross-validation with a value of 5 for CV. This is done for five receptions, with each reception being an average of 5-fold repeated five times. These evaluations represent the performance of sEMG signals with disturbances across three distinct situations. Based on the results in Tables 2 and 3, the network has substantial generalization capability across multiple datasets. As the window size increased, the model’s efficacy increased.

It has been demonstrated to be effective across a variety of datasets. The accuracy of the similar methods compared in Table 2 decreases as noise levels increase. In contrast to the U-Net and U-Net with MobileNetV2, the U-Net with MobileNetV2 and optBiLSTM method exhibits less accuracy drop due to the extraction of combined features and the optBiLSTM method’s ability to make decisions. On the other hand, there is less dispersion between the accuracy of each noise increase stage. This study used a proposed approach to generate normalized confusion matrices for the BioPatRec DB1, BioPatRec DB3, and Mendeley datasets (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Sample confusion matrices generated from the analysis of datasets using the proposed approach: (A) BioPatRec DB1, (B) BioPatRec DB3, and (C) Mendeley.

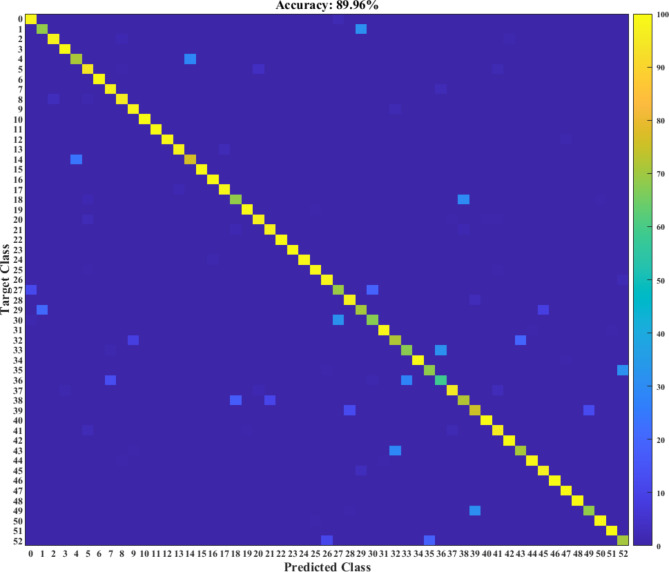

The suggested architecture achieved accuracy values of 92.40%, 91.48%, and 90.54%, respectively, for hand gestures ranging from 0 to 9. The validation process resulted in an average classification accuracy of 90.70% across all ten gestures, with the best-performing class achieving an accuracy rate of 95.00%. These statistics show that the majority of gestures were accurately predicted. To improve the accuracy and performance of classifying 26, 53, and 53 hand gestures and movements in the BioPatRec DB2, Ninapro DB4, and Ninapro DB5, respectively, the U-Net with MobileNet V2 and optimized BiLSTM were fine-tuned. These databases include a range of simple to complex gestures and movements that can be useful for research, development, and testing of robotics systems with various classes of movements. The proposed model accurately classifies hand gestures by comparing the features of a gesture to those of a known gesture. Figures 6, 7 and 8 illustrate the confusion matrices for the BioPatRec DB2, Ninapro DB4, and Ninapro DB5 using the proposed model for the remaining three databases.

Fig. 6.

Normalized confusion matrices showing two random results obtained from applying the proposed algorithm to BioPatRec DB2 data.

Fig. 7.

Normalized confusion matrix illustrating the results of applying the proposed structure to the Ninapro DB1 dataset.

Fig. 8.

Normalized confusion matrix showcasing the classification performance of the proposed structure on the Ninapro DB2 dataset.

Discussion

According to the proposed model, Tables 2 and 3 show that increasing the window size and using a hybrid design in learning can improve both the average accuracy and accuracy across different scenarios. The superior performance of the proposed model in the 250-300ms window compared to the 300-350ms window can be attributed to the combination of better signal quality, reduced noise, finer temporal resolution, effective data augmentation through overlapping windows, and the specific sensitivity of the deep learning architectures used. The accuracy can improve by around 3% with the hybrid architectures. Additionally, the window size can increase the reported accuracy by 1-2%. This can be explained by the fact that a larger window size can incorporate more information into the model during each time step. This helps in distinguishing between different motions. To increase the volume of data being fed to the model, we maintained a constant skip step of 32 instead of modifying it to accommodate the increase in window size. As the model is exposed to a larger and more diverse set of training data samples, it learns more about the underlying data representations.

The proposed model has an increased skip step, which helps reduce the number of data samples required to train the model. This results in enhanced model generalizability by mitigating the overfitting problem to the training dataset. The term “generalization” refers to the model’s ability to generate reliable predictions for data instances it has not seen before. This is achieved by training the model using many samples and evaluating it using entirely new data. Therefore, the system is expected to exhibit enhanced proficiency in accurately recognizing the inherent patterns associated with various motions, leading to superior performance when presented with novel test data. This study employs tiny windows with less overlap to enhance the clarity and distinctiveness of the surface sEMG signal. This approach facilitates the seamless integration of the proposed network with prosthetic devices in real time while minimizing delays. Tables 2 and 3 show a positive correlation between the increase in window size and the corresponding rise in average accuracy across all datasets. Precision increases by around 6–8% with every increase in window size, peaking at 92% with appropriate window size and overlap. Our research study found that 200–300 millisecond intervals with a 20% overlap yielded the most consistent and dependable outcomes. The characteristics of stationary sEMG signals were less pronounced than the influence exerted by the window size employed. Furthermore, minimal variation in accuracy was seen across several hand motion datasets in the presence of substantial background noise. The observed phenomenon might be attributed to the exceptional accuracy of the classifications seen across K-fold replications.

To address the concern of classification errors in hand gestures for different surface EMG signal datasets, we modified the duration of each window to approximately 200–300 milliseconds. We investigated two different levels of overlap: 20% and 50%. Generally, an interval between 200 and 250 milliseconds is considered a minor duration, whereas an interval between 250 and 300 milliseconds is considered lengthy. Moreover, low overlaps were defined as those falling within 10–20%, whereas big overlaps were defined as those falling within 20–40%.

The metrics of F1-score, precision, specificity, and sensitivity are presented in Fig. 9. We found that increasing the window length to a substantial length, often between 250 and 300 milliseconds and having a significant overlap between consecutive windows, was more effective. This decreased computing complexity necessitates balancing achieving a satisfactory classification accuracy and managing the overlap between consecutive windows. Using the optimal performance of previous studies, we established the appropriate window size for the sEMG signal to provide a fair comparison. All other variables were kept constant as in the previous experiments, as shown in Table 4. Our model outperformed the most advanced models on the Mendeley, BioPatRec DB3, and BioPatRec DB1 datasets.

Fig. 9.

Comprehensive evaluation of hand gesture recognition performance using metrics such as F1-score, precision, specificity, and sensitivity. Results are presented for varying window lengths and overlap conditions: (a) short window length with low overlap, (b) short window length with high overlap, (c) long window length with low overlap, and (d) long window length with high overlap.

Table 4.

Comparison of classification model accuracy rates, presented as percentage values. Bold values indicate the highest accuracy achieved for each dataset.

| Method | Mendeley data |

BioPatRec DB3 | BioPatRec DB2 | BioPatRec DB1 |

NinaPro DB5 |

NinaPro DB4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLF-CNN26 | 88.6 | 91.0 | 90.5 | 91.4 | 87.2 | 82.2 |

| EMGHandNet47 | - | - | 83.9 | - | - | 89.5 |

| Attention sEMG58 | - | - | - | - | 87.0 | 73.0 |

| HVPN59 | - | - | - | - | 87.1 | 67.0 |

| Multi-View CNN38 | - | 50.5 | 94.0 | 78.2 | 90.0 | 54.3 |

| SE-CNN Attention60 | - | - | - | - | 87.4 | 77.6 |

| ContraNet61 | 76.6 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Our model | 88.71 | 90.2 | 90.8 | 91.4 | 90.33 | 89.73 |

Compared to other models that used only the lowest number of parameters, our model achieved competitive classification accuracy for Mendeley, BioPatRec DB2, NinaPro DB5, and NinaPro DB4. While the suggested model may not have been the most accurate for all databases, it performed well and could compete well against other models with fewer parameters.

In this research, we tested our model’s ability to adapt to different datasets by computing the mean accuracy and variance of various structures on both the BioPatRec DB1 and DB3 databases. Our findings, presented in Table 5, demonstrate that our model outperforms existing architectures with an equivalent number of parameters and exhibits exceptional performance in various collection scenarios with a high level of stability. While classic feature extraction techniques consolidate multiple statistical features into a unified feature vector to enhance the extraction of relevant data from EMG signals, these techniques often increase computing complexity and hardware expenditures. To overcome these obstacles, advanced deep learning strategies have been developed to extract valuable characteristics and identify EMG patterns automatically.

Table 5.

Comparison of the proposed approach with similar models across various datasets, highlighting differences in computational complexity, variance, and accuracy.

For an optimal approach, a technique that can acquire comprehensive knowledge of each channel, extract distinctive characteristics for each one, and adapt to the idiosyncrasies of sEMG readings would be required. Moreover, the limited number of variables creates a disparity between the model’s absolute classification performance and that of the state of the art, especially when dealing with larger databases such as Ninapro DB5 and DB4. In this study, challenges in sEMG signal analysis and gesture recognition are identified, notably including channel-specific variability and noise interference in sEMG data. These challenges are addressed through the application of advanced signal processing techniques and multi-branch deep learning models.

Furthermore, adapting the methodology to accommodate larger datasets such as Ninapro DB5 and DB4 necessitates the implementation of strategies like data augmentation and transfer learning to uphold robust performance. Maintaining a balance in the number of variables is crucial to preserve model simplicity while ensuring classification accuracy, a task achieved through feature selection and algorithm optimization methods. Thus, the challenges and corresponding solutions are delineated as follows:

Interpreting and noise separation challenge: sEMG data may contain various types of noise, which can make it difficult to discern primary patterns. A solution can involve using signal filters or data preprocessing techniques to eliminate noise.

Adapting to channel-specific characteristics challenge: Since sEMG features may vary across channels, finding and extracting features that are suitable for each channel’s characteristics poses a challenge. A solution could involve using multi-branch deep networks, with each branch dedicated to analyzing and extracting features specific to a channel.

Transferability challenge to larger datasets: The transferability of a model to larger datasets is crucial, as the model may exhibit unstable performance when faced with new data. A solution may include increasing diversity in the training data, employing transfer learning techniques, or adapting the model to new data.

Trade-off between number of variables and algorithm performance: Selecting an appropriate number of variables can be challenging, as a large number of variables may hinder the model’s generalizability and increase complexity. A solution could involve feature selection techniques, analyzing feature importance, and using optimization algorithms to reduce the effects of unnecessary variables.

Edge computing: Considering the existing challenges in analyzing sEMG signals and recognizing movements, particularly the channel-specific variations and noise interferences in sEMG data, the integration of Edge Computing has emerged as a pivotal solution. This technology enables real-time processing and decision-making closer to the data source, thereby reducing response time and enhancing processing speed. Furthermore, this integration facilitates the execution of deep learning models for sEMG data processing, including the utilization of advanced signal processing techniques and multi-branch deep learning models. Consequently, the integration of edge computing improves the efficiency and accuracy of movement detection and sEMG signal classification while addressing the challenges associated with data analysis.

Limitations and real-world applicability

While the proposed method demonstrates strong accuracy and robustness in controlled settings, several limitations may impact its performance in real-world applications. Acknowledging these potential challenges and providing strategies to address them are essential for effective deployment beyond the lab.

One significant limitation arises from the inherent variability in sEMG signals across different users and environmental conditions. Factors such as muscle structure, skin properties, and electrode positioning can introduce inconsistencies that affect the accuracy of gesture classification. These variations may be particularly pronounced in diverse populations, leading to a potential decline in model performance when deployed in real-world scenarios with a wide range of users. To mitigate this issue, adaptive calibration techniques and transfer learning approaches could be explored. For instance, transfer learning enables the model to leverage data from similar users to fine-tune its performance for new individuals, reducing the need for extensive retraining. Adaptive calibration, which dynamically adjusts the model based on each user’s unique sEMG signal patterns, also offers a promising avenue for enhancing robustness across diverse conditions.

The integration of edge computing facilitates real-time processing and reduces latency, a critical factor for applications in assistive technologies and prosthetic control. However, real-world environments often impose hardware constraints that can limit performance compared to the controlled lab conditions where the model was originally tested. Portable devices, such as wearables and mobile processors, may have limited memory, processing power, and battery life, which could restrict the model’s computational capacity and, consequently, its classification accuracy. To address these constraints, future work could investigate the use of lightweight neural network architectures, such as pruning or quantization techniques, which streamline the model while maintaining a reasonable level of accuracy. These optimizations could help ensure that the model remains efficient and functional in resource-constrained settings.

In real-world environments, the presence of environmental noise and other external factors, such as user movement or perspiration, may further affect signal quality and, in turn, model performance. While the current model performs well under controlled conditions, real-world usage would likely require additional preprocessing or noise-reduction techniques to maintain stability. Employing real-time signal filtering or implementing a feedback mechanism that informs users when signal quality drops could help manage these issues.

While the method proposed shows promise in gesture classification, several enhancements would facilitate its application in diverse real-world scenarios. Future work could focus on incorporating adaptive learning frameworks that allow the model to update its parameters over time as it gathers data from specific users, improving personalization and accuracy. Additionally, developing user-friendly interfaces and testing the model in broader contexts with real users can provide valuable insights to fine-tune the system for practical deployment. The integration of Bayesian optimization with metaheuristic algorithms presents an exciting direction for future work. Techniques such as the Interactive Fuzzy Bayesian Search Algorithm63 and the Bayesian Interactive Search Algorithm64 have demonstrated enhanced performance in solving complex optimization problems by combining the exploratory capabilities of metaheuristics with the probabilistic precision of Bayesian methods. Applying such hybrid approaches to optimize deep learning architectures, like the BiLSTM in this study, could further improve global search capabilities and robustness in dynamic environments. Additionally, we plan to explore advanced multi-channel and multi-sensor fusion techniques65,66 to improve motion detection accuracy and address current challenges in future research.

Additionally, although the components of the proposed model were chosen to meet the specific performance needs of this study, other deep learning modules could also be considered. For example, transformers, with their self-attention mechanisms, have the potential to enhance temporal modeling by effectively capturing long-range dependencies. Similarly, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) could be advantageous in representing the interrelationships between spatial and temporal features, particularly when working with data that exhibits graph-like structures. Additionally, lightweight CNN architectures, such as EfficientNet, offer opportunities to further reduce computational complexity while maintaining high accuracy. These alternatives present promising avenues for future research to refine and extend the proposed approach.

Notably, sEMG signals are inherently subject-dependent, as they are influenced by individual physiological and anatomical differences, such as muscle size, composition, skin impedance, and fat distribution. Furthermore, variations in electrode placement, even within the same subject, can alter signal characteristics. These factors create significant challenges for developing generalized models that perform consistently across a wide range of users.

In this study, while the proposed model demonstrated robust performance across multiple datasets, it is important to recognize the potential impact of subject variability. Models trained on data from a limited number of users may struggle to generalize effectively when applied to new individuals with different physiological attributes. To address this challenge, several strategies can be employed:

Transfer Learning: Leveraging pre-trained models and fine-tuning them on data from new subjects can help adapt the model to individual-specific characteristics, reducing the need for extensive retraining.

Adaptive Calibration: Real-time calibration methods can dynamically adjust the model parameters based on feedback from a specific user’s signals, improving performance during deployment.

Data Augmentation: Simulating variability in training data through techniques such as adding noise, altering electrode positioning, or generating synthetic sEMG signals can enhance the model’s robustness against subject-related differences.

Conclusion

In this paper, we introduce a novel approach by combining the BiLSTM model with a MobileNetV2 encoder and U-Net architecture to enhance motion recognition using sEMG signals. To tackle the challenge of non-stationarity and simplify the augmentation process for increasing signal diversity in the deep learning framework, our model incorporates windowing and overlapping techniques between consecutive sEMG signals. While the architecture can extract features from the entire sEMG signal, feature extraction is limited to a specific section. Additionally, spectrograms generated from each signal frame are inputted into the deep learning network. Leveraging all dimensions of the surface EMG signal, our approach significantly improves categorization accuracy across various datasets. We evaluate our method on five sEMG benchmark datasets, including Mendeley Data, BioPatRec DB3, BioPatRec DB2, BioPatRec DB1, NinaPro DB4, and NinaPro DB5. Our proposed model, characterized by a reduced number of parameters, achieves comparable classification accuracy to existing models on BioPatRec DB2, NinaPro DB4, and NinaPro DB5. Notably, our framework outperforms existing models on Mendeley Data, BioPatRec DB3, and BioPatRec DB1. Demonstrating exceptional performance across multiple datasets, our proposed architecture excels in identifying gestures from sEMG signals. Furthermore, its ability to generalize to diverse sEMG data further underscores its practical utility. Moreover, the incorporation of edge computing into our framework significantly enhances real-time processing efficiency and decision-making closer to the data source, ensuring faster convergence to an optimal configuration and enhancing overall system responsiveness.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Khosro Rezaee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review and Editing.Safoura Farsi Khavari: Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft.Mojtaba Ansari: Investigation, Resources, Software, Visualization.Fatemeh Zare: Validation, Writing – Review and Editing.Mohammad Hossein Alizadeh Roknabadi: Writing – Review and Editing.

Data availability

We, hereby declare that the data and materials associated with this work are available and can be provided upon request. Moreover, the data utilized in the experiments are accessible via the supplemental file. The dataset is sourced from Ninapro DB455, Ninapro DB555, BioPatRec DB1, DB2, and DB356, and Mendeley Data source48.

Declarations

Consent for publication

All authors have reviewed and consented to the submission and publication of this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tuncer, T., Dogan, S. & Subasi, A. Surface EMG signal classification using ternary pattern and discrete wavelet transform based feature extraction for hand movement recognition. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 58, 101872 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokri, C., Bamdad, M. & Abolghasemi, V. Muscle force estimation from lower limb EMG signals using novel optimised machine learning techniques. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput.60 (3), 683–699 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai, Y. et al. MSEva: a musculoskeletal rehabilitation evaluation system based on EMG signals. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw.19 (1), 1–23 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang, N. et al. Loading Recognition for Lumbar Exoskeleton Based on Multi-channel Surface Electromyography from Low Back muscles. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Bicer, Y. et al. User training with error augmentation for sEMG-based gesture classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil Eng. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Orozco-Mora, C. E., Oceguera-Cuevas, D., Fuentes-Aguilar, R. Q. & Hernandez-Melgarejo, G. Stress level estimation based on physiological signals for virtual reality applications. IEEE Access.10, 68755–68767 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahim, M. A. & Shin, J. Hand movement activity-based character input system on a virtual keyboard. Electronics9 (5), 774 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laksono, P. W. et al. Mapping three electromyography signals generated by human elbow and shoulder movements to two degree of freedom upper-limb robot control. Robotics9 (4), 83 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleming, A. et al. Myoelectric control of robotic lower limb prostheses: a review of electromyography interfaces, control paradigms, challenges and future directions. J. Neural Eng.18 (4), 041004 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Souza, J. O. et al. Investigation of different approaches to real-time control of prosthetic hands with electromyography signals. IEEE Sens. J.21 (18), 20674–20684 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lv, X. et al. Gesture recognition based on sEMG using multi-attention mechanism for remote control. Neural Comput. Appl.35 (19), 13839–13849 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iqbal, H., Zheng, J., Chai, R. & Chandrasekaran, S. Electric powered wheelchair control using user-independent classification methods based on surface electromyography signals. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput.62 (1), 167–182 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Aubidy, K. M. & Abdulghani, M. M. Towards Intelligent Control of Electric Wheelchairs for Physically Challenged People. Advanced Systems for Biomedical Applications. :225 – 60. (2021).

- 14.Teng, G. et al. Design and development of human computer interface using electrooculogram with deep learning. Artif. Intell. Med.102, 101765 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eraslan, U., Kitis, A., Demirkan, A. F. & Ozcan, R. H. Effect of electromyographic biofeedback training on functional status in zone I-III flexor tendon injuries: a randomized controlled trial. Physiother. Theory Pract.39 (8), 1563–1573 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park, S. et al. User-driven functional movement training with a wearable hand robot after stroke. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng.28 (10), 2265–2275 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fatimah, B., Singh, P., Singhal, A. & Pachori, R. B. Hand movement recognition from sEMG signals using Fourier decomposition method. Biocybernetics Biomedical Eng.41 (2), 690–703 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amanpreet, K. Machine learning-based novel approach to classify the shoulder motion of upper limb amputees. Biocybernetics Biomedical Eng.39 (3), 857–867 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaudet, G., Raison, M. & Achiche, S. Classification of upper limb phantom movements in transhumeral amputees using electromyographic and kinematic features. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell.68, 153–164 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordleeva, S. Y. et al. Real-time EEG–EMG human–machine interface-based control system for a lower-limb exoskeleton. IEEE Access.8, 84070–84081 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.De la Cruz-Sánchez, B. A., Arias-Montiel, M. & Lugo-González, E. EMG-controlled hand exoskeleton for assisted bilateral rehabilitation. Biocybernetics Biomedical Eng.42 (2), 596–614 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park, S. et al. Multimodal sensing and interaction for a robotic hand orthosis. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett.4 (2), 315–322 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simão, M., Neto, P. & Gibaru, O. EMG-based online classification of gestures with recurrent neural networks. Pattern Recognit. Lett.128, 45–51 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young, A. J., Smith, L. H., Rouse, E. J. & Hargrove, L. J. Classification of simultaneous movements using surface EMG pattern recognition. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng.60 (5), 1250–1258 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vitale, A., Donati, E., Germann, R. & Magno, M. Neuromorphic edge computing for biomedical applications: gesture classification using emg signals. IEEE Sens. J.22 (20), 19490–19499 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong, B. et al. A Global and local feature fused CNN architecture for the sEMG-based hand gesture recognition. Comput. Biol. Med.166, 107497 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding, Z. et al. sEMG-based gesture recognition with convolution neural networks. Sustainability10 (6), 1865 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allard, U. C. et al. A convolutional neural network for robotic arm guidance using sEMG based frequency-features. In2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). Oct 9 (pp. 2464–2470). (2016).

- 29.Shim, H. M. et al. EMG pattern classification by split and merge deep belief network. Symmetry8 (12), 148 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su, Y., Sun, S., Ozturk, Y. & Tian, M. Measurement of upper limb muscle fatigue using deep belief networks. J. Mech. Med. Biology. 16 (08), 1640032 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Côté-Allard, U. et al. Transfer learning for sEMG hand gestures recognition using convolutional neural networks. In IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC) 2017 Oct 5 (pp. 1663–1668). (2017).

- 32.Du, Y., Jin, W., Wei, W., Hu, Y. & Geng, W. Surface EMG-based inter-session gesture recognition enhanced by deep domain adaptation. Sensors17 (3), 458 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suri, K. & Gupta, R. Transfer learning for semg-based hand gesture classification using deep learning in a master-slave architecture. In2018 3rd International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I) 2018 Oct 10 (pp. 178–183).

- 34.Côté-Allard, U. et al. Deep learning for electromyographic hand gesture signal classification using transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng.27 (4), 760–771 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu, Y. et al. A novel attention-based hybrid CNN-RNN architecture for sEMG-based gesture recognition. PloS One. 13 (10), e0206049 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ashraf, H. et al. Optimizing the performance of convolutional neural network for enhanced gesture recognition using sEMG. Sci. Rep.14 (1), 2020 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu, Y. et al. SEMG-based gesture recognition with embedded virtual hand poses and adversarial learning. IEEE Access.7, 104108–104120 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei, W. et al. Surface-electromyography-based gesture recognition by multi-view deep learning. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng.66 (10), 2964–2973 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gautam, A. et al. Locomo-net: a low-complex deep learning framework for sEMG-based hand movement recognition for prosthetic control. IEEE J. Translational Eng. Health Med.8, 1–2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nasri, N., Orts-Escolano, S. & Cazorla, M. An semg-controlled 3d game for rehabilitation therapies: real-time time hand gesture recognition using deep learning techniques. Sensors20 (22), 6451 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu, Z., Zhao, J., Wang, Y., He, L. & Wang, S. Surface EMG-based instantaneous hand gesture recognition using convolutional neural network with the transfer learning method. Sensors21 (7), 2540 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su, Z., Liu, H., Qian, J., Zhang, Z. & Zhang, L. Hand gesture recognition based on sEMG signal and convolutional neural network. Int. J. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell.35 (11), 2151012 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsinganos, P., Cornelis, B., Cornelis, J., Jansen, B. & Skodras, A. Hilbert sEMG data scanning for hand gesture recognition based on deep learning. Neural Comput. Appl.33, 2645–2666 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tyacke, E. et al. Hand gesture recognition via transient sEMG using transfer learning of dilated efficient CapsNet: towards generalization for neurorobotics. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett.7 (4), 9216–9223 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu, P., Li, F. & Wang, H. A novel concatenate feature fusion RCNN architecture for sEMG-based hand gesture recognition. PloS One. 17 (1), e0262810 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, H., Zhang, Y., Liu, C. & Liu, H. sEMG based hand gesture recognition with deformable convolutional network. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybernet.13 (6), 1729–1738 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karnam, N. K., Dubey, S. R., Turlapaty, A. C., Gokaraju, B. & EMGHandNet: A hybrid CNN and Bi-LSTM architecture for hand activity classification using surface EMG signals. Biocybernetics Biomedical Eng.42 (1), 325–340 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ozdemir, M. A., Kisa, D. H., Guren, O. & Akan, A. Dataset for multi-channel surface electromyography (sEMG) signals of hand gestures. Data Brief.41, 107921 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]