Abstract

Abscisic acid (ABA) is a crucial phytohormone that regulates plant growth and stress responses. While substantial knowledge exists about transcriptional regulation, the molecular mechanisms underlying ABA-triggered translational regulation remain unclear. Recent advances in deep sequencing of ribosome footprints (Ribo-seq) enable the mapping and quantification of mRNA translation efficiency. Additionally, RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) play essential roles in translational regulation by interacting with target RNA molecules, making the identification of binding sites via UV crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP) critical for understanding RBP function. Glycine-rich RNA-binding proteins (GRPs), a prominent class of RBPs in plants, are responsive to ABA. In this study, RNA-seq and Ribo-seq analyses were conducted on 3-day-old Col-0 and grp7grp8 seedlings of Arabidopsis thaliana, treated with either ABA or mock solutions. These analyses facilitated deep sequencing of total mRNA and mRNA fragments protected by translating ribosomes. Additionally, CLIP-seq analysis of pGRP7::GRP7-GFP grp7-1 identified RNA bound by GRP7. This multi-omics dataset allows for a comprehensive investigation of the plant’s response to ABA from various perspectives, providing a significant resource for studying ABA-regulated mRNA translation efficiency.

Subject terms: Plant hormones, Plant stress responses

Background & Summary

Abscisic acid (ABA) is a vital phytohormone that regulates plant development and responses to environmental stresses1. In the presence of ABA, the ABA receptors PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE1/ PYRABACTIN-LIKE/ REGULATORY COMPONENTS OF ABA RECEPTORS (PYR/PYL/RCAR) form a complex with PROTEIN PHOSPHATASE 2Cs (PP2Cs). This complex inhibits the phosphatase activity of PP2Cs, thereby activating SNF1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE 2 s (SnRK2s). Activated SnRK2s, in turn, stimulates ABRE-binding protein/ABRE-binding factor (AREB/ABF) transcription factors, leading to the enhanced transcription of ABA-responsive genes1,2. In addition to activating downstream transcriptional regulation, findings indicate that ABA also inhibits global protein translation3,4. However, the specific changes in mRNA translation efficiency regulated by ABA signaling, along with the underlying regulatory mechanisms, remain poorly understood. Thus, further investigation into the complex interplay between ABA signaling and translational regulation is crucial for a deeper understanding of how ABA governs plant responses to environmental cues.

Protein expression undergoes greater evolutionary constraints than mRNA levels, with translation efficiency playing a pivotal role in shaping protein levels during cellular adaptation to various stimuli5,6. Given the challenge of accurately monitoring translation compared to measuring mRNA levels, historical efforts in globally monitoring gene expression have primarily concentrated on measuring mRNA levels. However, translational control is an essential and regulated step in determining levels of protein expression6,7. This has changed with the development of Ribo-seq, a deep-sequencing-based tool enabling detailed measurement of translation globally and in vivo, was developed and first described in 20098. The sequencing of these ribosome-protected fragments is termed ribosome footprints9. This approach provides comprehensive insights into changes in mRNA translation efficiency, enabling researchers to explore the intricacies of post-transcriptional regulation and its influence on cellular protein expression. By quantifying the density of protected fragments on a specific transcript, researchers can estimate the rate of protein synthesis. Furthermore, identifying the locations of these protected fragments facilitates the empirical determination of the translated products, revealing new open reading frames (ORFs) and potentially prompting revisions in the annotation of known genes. Additionally, the pattern of ribosome footprints can be utilized to identify regulatory translation pauses and translated upstream open reading frames (uORFs)9–11. Understanding translation dynamics is essential for comprehending post-transcriptional regulation closely linked to cellular protein levels.

The regulation of translation involves a diverse spectrum of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that play significant roles in the complex process of protein synthesis12,13. Among the RBPs, glycine-rich RNA binding proteins (GRPs) are associated with abiotic stresses14. Notably, GRP7, which contains an N-terminal RNA recognition motif and a C-terminal glycine-rich domain, is linked to various biotic and abiotic stresses, including ABA treatment, temperature fluctuations, drought, and salinity14–16. GRP7 exerts multiple functions in RNA processing, such as alternative splicing of precursor mRNA, primary microRNA processing, and acting as a shuttle protein that facilitates mRNA export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm under cold stress15–18. Furthermore, GRP7 plays a crucial role in translation regulation. Elevated temperatures rapidly induce GRP7 condensates, and its liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) in the cytoplasm contributes to the formation of stress granules that sequester RNA and inhibit translation19. Additionally, GRP7 is implicated in innate immunity and interacts with various components of the translational machinery, including eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF4A1, eIF4A2, eIF4E), and ribosomal protein uS11z (uS11z)20. GRP8, another member of the GRP family, exhibits high sequence similarity to GRP7 and functional redundancy with it4,21. Double mutants for GRP7 and GRP8 display hypersensitivity to ABA during cotyledon greening, and GRP7 protein level decrease sharply upon ABA treatment4. However, whether and how GRP7 and GRP8 are involved in ABA-mediated translation regulation remains unclear.

In this study, we present RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data of 3-day-old seedlings of Col-0 and grp7grp8, treated with either 5 μM ABA or mock solution. These assays enabled us to generate a genome-wide transcriptome and translatome for association analysis. Additionally, we utilized CLIP-seq to identify the RNA targets of GRP7 under both ABA treatment and control conditions during early seedling development. Our findings provide a valuable dataset from Ribo-seq and CLIP-seq analyses, establishing a novel molecular link between ABA signaling and the regulation of translation, elucidating the interplay between GRP7 and ABA-mediated translational regulation.

Methods

Sample collection

Arabidopsis thaliana seeds of wild type Col-0, grp7grp8 double mutants4 and pGRP7::GRP7-GFP grp7-1 complementary line22 were first sterilized with 75% ethanol supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100. Subsequently, the seeds were sown onto plates containing half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium, adjusted to pH 5.7, and supplemented with 1% (w/v) sucrose and 0.8% (w/v) agar. The plates were then subjected to vernalization in the dark at 4 °C for three days, followed by growth under long-day conditions (16 hours of light/8 hours of darkness) at 22 °C for an additional three days in a light incubator. Thereafter, 3-day-old seedlings were transferred to filter paper moistened with 1/2 MS liquid medium containing 5 μM ABA or an equivalent volume of mock solution, and incubated under the same long-day conditions at 22 °C for 4 hours. The seedlings were then gently dried and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The samples were stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

Three-day-old seedlings of the Col-0 and grp7grp8 genotypes, treated with either 5 μM ABA or a mock solution, were harvested for RNA sequencing. RNA was isolated from these samples using the Quick RNA Isolation Kit (Huayueyang) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The extracted RNA samples were then sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform to generate transcriptomic data.

Data processing of RNA-seq data

Raw reads of RNA-seq were firstly filtered by fastp (v0.20.1)23 with parameter “--detect_adapter_for_pe” for adapters removing, low-quality bases trimming, and reads filtering. The obtained clean reads were subsequently aligned to the Arabidopsis thaliana reference genome (TAIR10) using STAR (v2.7.10)24 with default parameters. Quantification of reads that mapped to each gene was counted using featureCounts (v2.0.1)25 with the parameter “-p -P -B -C” for RNA-seq. The raw counts of RNA-seq were used as inputs for differentially expression analysis by DESeq2 (v1.26.0)26 and further normalized to FPKM (Fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads). FPKM values of gene expression were Z-scaled and clustered by k-means method and displayed using R package ComplexHeatmap (v2.4.3)27.

Deep sequencing of ribosome footprints (Ribo-seq)

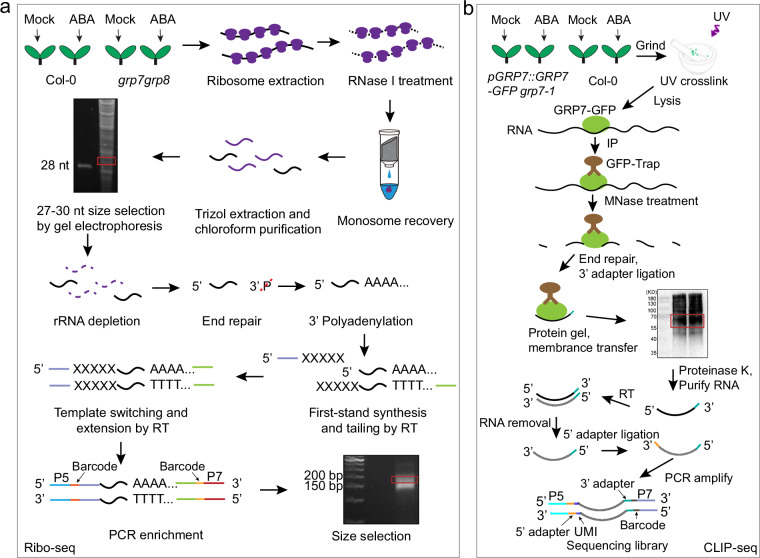

The overview of the library construction of Ribo-Seq28,29 is illustrated in Fig. 1a.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design and workflow of Ribo-seq and CLIP-seq. (a) The sequencing library construction protocol for Ribo-seq. (b) The sequencing library construction protocol for CLIP-seq. P5 and P7 were PCR primer, Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) was random sequence.

Sample lysis

The 3-day-old seedlings (0.2 g) of Col-0 and grp7grp8 with 5 μM ABA or mock were grounded in liquid nitrogen followed by resuspension in 600 μL ice-cold lysis buffer that was composed of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, with 1 mM DTT, 100 ug/mL cycloheximide (CHX) and 25 U/mL Turbo DNase added freshly. Clarifying the lysate by centrifugation for 10 min at 20,000 g under 4 °C, the soluble supernatant was recovered.

Partial RNA digestion

6 μL of RNase I (100 U/μL) was added to 600 μL lysate and incubated for 45 min at room temperature with gentle mixing. Digestion was stopped by the addition of 10 μL SUPERase-In RNase inhibitor (Invitrogen Cat# AM2694).

Isolation of ribosome-protected RNA fragments

Meanwhile, MicroSpin S-400 HR columns (GE Healthcare Cat# 275140-01) were equilibrated with 3 mL of polysome buffer, which was composed of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, with 1 mM DTT and 100 ug/mL CHX added freshly, by gravity flow and emptied by centrifugation at 600 g for 4 min. Then digested lysate was immediately loaded on the column and eluted from the column by centrifugation at 600 g for 2 min at 4 °C.

RNA extraction and size selection

The RNA was extracted from the flow-through using Trizol (Thermo Fisher, 15596018CN) and further purified by chloroform and isopropanol precipitation. The RNA was separated by electrophoresis for 65 min at 200 V using 15% denaturing urea-PAGE gel. The ribosome-protected RNA fragments (RPF) of between 27 nt to 30 nt was cut and eluted in 800 μL of RNA gel extraction buffer, which was composed of 300 mM sodium acetate pH 5.2, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.25% (w/v) SDS, overnight at room temperature with gentle mixing. Precipitate RNA by 800 μL isopropanol and 1 μL GlycoBlue with mixing. Resuspend size-selected RNA in 10 μL DEPC H2O and transfer to a clean RNase-free microfuge tube.

Remove of rRNA

The rRNA fragments were removed using the Ribo-off rRNA depletion kit (Plant) (Vazyme, N409). Purify RNA using the Zymo column cleanup-RNA Clean & Concentrator-5 columns (Cat R1016) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

3′ end dephosphorylation

The mRNAs were dephosphorylated by PNK mix (60 μL 5X PNK pH 6.5 buffer, 3 μL 0.1 M DTT, 5 μL RNase Inhibitor, 7 μL T4 PNK, add DEPC H2O to 300 μL) and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C with 1000 rpm shaking. Purify RNA using the Zymo column cleanup-RNA Clean & Concentrator-5 columns.

Library preparation

The RNA fragments were subjected into library generation using Smarter smRNA-Seq kit (Takara Cat# 635031) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The final library of approximately 180 bp was size-selected by gel electrophoresis for 90 min at 100 V using a 3% agarose gel. The constructed library was sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform.

Ribo-seq data processing

For Ribo-seq data analysis, we exclusively utilized the first sequencing reads (*_R1.fq.gz) and filtered by fastp (v0.20.1)23 with parameter “-a AAAAAAAAAA -f 3 -l 16”. The filtered reads were firstly aligned against the non-coding RNA sequences of A. thaliana downloaded from Ensembl Plants30 using bowtie231 to produce the unaligned reads. Subsequently, these unaligned reads were mapped to reference genome using STAR (v2.7.10)24 with parameters “--outFilterMismatchNmax 2 --outFilterMultimapNmax 1 --outFilterMatchNmin 14 --alignEndsType EndToEnd”. The number of reads that mapped to each gene was counted using featureCounts (v2.0.1)25 with default parameters. The processed raw counts were further normalized to RPKM (Reads per kilobase per million mapped reads) values and used as inputs for differentially expression analysis by DESeq2 (v1.26.0)26.

Analysis of translational efficiency

Genes with expression levels exceeding 1 RPKM in Ribo-seq and 1 FPKM in RNA-seq were kept for the calculation of translation efficiency (TrE). TrE was determined by comparing the transcription and translation rates of genes, calculated as the ratio of average RPKM values from Ribo-seq to FPKM values from RNA-seq. The formula is RPKM Ribo-seq/FPKM RNA-seq. To further explore the dynamics of translation, we utilized the Xtail package (v1.1.5)32 for calculating differential translation efficiencies across the dataset. The raw counts matrix obtained from RNA-seq and Ribo-seq were utilized as input for Xtail, with a significant threshold set at an adjusted p-value < 0.05 to determine differential translational efficiency.

Crosslinking and immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing (CLIP-seq)

The overview of the library construction of CLIP-Seq33,34 is illustrated in Fig. 1b.

UV-crosslinking

The 3-day-old seedlings (1 g) of Col-0 and pGRP7::GRP7-GFP grp7-1, treated with either 5 μM ABA or mock solution, were ground to powder using liquid nitrogen and then crosslinked twice at 600 mJ/cm2 in a UVP crosslinker (Analytik jena).

Immunoprecipitation

The powder was lysed by 1.5 mL ice-cold iCLIP lysis buffer that was composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL®CA-630, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and protease inhibitor added freshly. Clarifying the lysate by centrifugation for 15 min at 12000 rpm under 4 °C, the soluble supernatant was recovered. 45 μL of DNase I (NEB, M0303L) was added to 1.5 mL lysate and incubated for 5 min at 37 °C with 1000 rpm shaking. Place the lysate on ice for 5 minutes, then clarify it by centrifugation at 12000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4 °C. After centrifugation, recover the soluble supernatant. The RNA-protein complexes (RNP) were enriched from the lysate by immunoprecipitation using GFP-Trap beads (Lablead, GNM-25-1000) for 2 h at 4 °C with constant rotation. Collect the beads on the magnetic stand, discard the supernatant and wash the beads 2x with 1 mL cold Wash buffer (1x PBS, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.5% IGEPAL®CA-630), 2x with 1 mL cold High salt wash buffer (5x PBS, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.5% IGEPAL®CA-630) and 2x with 1 mL cold PNK buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5% IGEPAL®CA-630).

Partial RNA digestion

RNAs on beads were partially digested by micrococcal nuclease (2 × 10−5 U/μL, Takara, 2910 A) incubated for 10 min at 37 °C with 1000 rpm shaking. Wash the beads 2x with 1 mL cold PNK + EGTA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 20 mM EGTA, 0.5% IGEPAL®CA-630), 2x with 1 mL cold Wash buffer and 2x with 1 mL cold PNK buffer.

3′ end dephosphorylation and 3′ linker ligate RNA

The RNAs on beads were dephosphorylated by PNK mix (60 μL 5X PNK pH 6.5 buffer, 3 μL 0.1 M DTT, 5 μL RNase Inhibitor, 7 μL T4 PNK, 225 μL DEPC H2O) and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C with 1000 rpm shaking. Wash the beads 2x with 1 mL cold Wash buffer, 2x with 1 mL cold High salt wash buffer and 2x with 1 mL cold 1X Ligase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2). RNAs on beads were ligated 3’ RNA linker by 3’ ligation mix (3 μL 10X Ligase buffer, 0.3 μL 0.1 M ATP, 0.8 μL 100% DMSO, 9 μL 50% PEG8000, 0.4 μL RNase Inhibitor, 2.5 μL RNA Ligase high conc, 2.5 μL RNA adapters, 11.5 μL DEPC H2O) and flick to mix, and incubate for 75 min at room temperature. Wash the beads 2x with 1 mL cold Wash buffer, 2x with 1 mL cold High salt wash buffer and 2x with 1 mL cold PNK buffer. Elute into 5 μL 5X SDS loading buffer and 20 μL DEPC H2O for 10 min at 70 °C with 1200 rpm shaking.

SDS-PAGE and nitrocellulose transfer

Load 20 μL of the eluate onto a 4-12% NuPAGE BisTris polyacrylamide gel for electrophoresis. For better excision leave out at least one well between the two sample. Run for using MOPS SDS running buffer and subsequently blot onto nitrocellulose for 2 hours at 200 mA on ice. Cut lane from nitrocellulose from the RBP band to 20 kDa above it. Cut the membrane area into pieces and transfer them to a fresh 2 mL tube.

Proteinase K digestion and cleanup RNA

Add 200 μL Proteinase K mix (160 μL PK buffer and 40 μL Proteinase K), Digest for 20 min at 37 °C with 1200 rpm shaking. Add 200 μL fresh Urea/PK buffer (420 mg Urea in PK buffer to final volume of 1 mL) and incubate for 20 min at 37 °C with 1200 rpm shaking. Add 400 μL acid phenol: chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, v/v) and mix well, incubate for 5 min at 37 °C with 1200 rpm shaking. Spin briefly, transfer all except membrane slices to a fresh 2 mL tube, incubate for 5 min at 37 °C with 1200 rpm shaking. Centrifuge at 13000 g, 15 min, room temperature. Transfer 400 μL aqueous layer to new 15 mL tube. Purify RNA using the Zymo column cleanup-RNA Clean & Concentrator-5 columns (Cat R1016) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Reverse transcription

Mix 10 μL of RNA with 0.5 μL AR17 primer, heat at 65 °C for 2 min in a pre-heated PCR block, place immediately on ice. Add 10 μL reverse transcription mix (2 μL 10x AffinityScript Buffer, 2 μL 0.1 M DTT, 0.8 μL 25 mM dNTPs, 0.3 μL RNase Inhibitor, 0.9 μL AffinityScript Enzyme, 4 μL DEPC H2O) to each sample, mix well, incubate 55 °C, 45 min in a pre-heated PCR block.

Cleanup cDNA

Add 3.5 μL ExoSAP-IT to each sample and mix well, incubate for 15 min at 37 °C. Add 1 μL 0.5 M EDTA and mix well, and add 3 μL 1 M NaOH and mix well, incubate for 12 min at 70 °C, and add 3 μL 1 M HCl and mix well. MyONE Silane beads cleanup cDNA (Prepare beads: Magnetically separate 10 μL MyONE Silane beads per sample, remove supernatant; Wash 1x with 500 μL RLT buffer; Resuspend beads in 93 μL RLT buffer.

Bind RNA: Add beads in 93 μL RLT buffer to sample, mix; Add 111.6 μL 100% EtOH; Pipette mix, leave pipette tip in tube, pipette mix twice, for 5 min. Magnetically separate, remove supernatant; Add 1 mL 80% EtOH, pipette resuspend and move to new tube; After 30 s, magnetically separate, remove supernatant; Wash 2x with 80% EtOH; Spin briefly, magnetically separate, remove residual liquid with fine tip; Air-dry 5 min. Resuspend in 5 μL 5 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5. Let sit for 5 min, do not remove from beads.)

5′ linker ligate cDNA

On MyONE Silane beads, add 0.8 μL 5′ adapter and 1 μL 100% DMSO to 5 μL cDNA on beads, heat at 75 °C, 2 min, place immediately on ice. Add 12.8 μL ligation mix (2 μL 10x NEB RNA Ligase Buffer, 0.2 μL 0.1 M ATP, 9 μL 50% PEG8000, 0.5 μL RNA Ligase high conc, 1.1 μL H2O) to each sample, mix sample with pipette tip. Add another 1 μL RNA Ligase high conc to each sample, flick to mix, and incubate at room temperature overnight. MyONE Silane beads cleanup linker-ligated cDNA.

PCR amplify cDNA

Prepare PCR master mix (25 μL 2X seqAmp PCR Buffer, 12 μL Nuclease-Free H2O, 1 μL seqAmp DNA Polymerase) for all reactions, add 38 μL PCR master mix to each sample (10 μL), then add 1 μL of each Forward and Reverse primer, mix well. Run the plate with the following program in the PCR machine: 98°C 1 min, 5 cycles of: 98°C 10 s, 60°C 5 s, 68°C 10 s. qPCR quantitation: The 5 μL PCR sample was taken from the tube and prepared into a 15 μL qPCR mix. The final number of PCR cycles was determined according to the ct value of qPCR. Continue to run the plate in the PCR machine to final number of PCR cycles.

Cleanup library

The final library of approximately 150-200 bp was size-selected by gel electrophoresis for 90 min at 100 V using a 3% agarose gel. The constructed library was sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform.

CLIP-seq data processing

The initial processing of CLIP-seq was conducted using fastp (v0.20.1)23 with parameter “--adapter_sequence TGGAATTCTCGG --adapter_sequence_r2 GATCGTCGGACT” set for filtering raw reads. Then the resulting clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using STAR (v2.7.10)24 with no more than two mismatches, ensuring high accuracy in reads mapping24. To enhance the quality and reliability of the results, Picard (v2.23.3) was employed to remove duplicates among the mapped reads, thereby reducing potential bias introduced by PCR amplification or sequencing artifacts.

GRP7 binding site identification

The GRP7 binding sites were identified by performing CLIP-seq peak calling using CLIPper (v0.1.4)35 with default parameters. Then, bedtools36 was used to retain the peaks consistently observed across two biological replicates, ensuring robustness of results. Significant GRP7 binding sites were defined as those exclusively present in IP samples yet absent in negative controls. The identified GRP7 binding peaks were annotated against the Arabidopsis thaliana genome using the “annotatePeak” function in R package ChIPseeker (v1.26.2)37. Gene promoters were defined as regions 1.5 Kb upstream from the transcription start site (TSS). The GRP7-binding efficiency of a gene was determined by calculating the ratio of CLIP-seq CPM values (Counts per million) to mRNA-seq FPKM values.

RNA-immunoprecipitation-qPCR (RIP-qPCR)

The overview of the workflow of RIP-qPCR38 is illustrated in Fig. 2a. One gram of 3-day-old Col-0 and pGRP7::GRP7-GFP grp7-1 were treated with 5 μM ABA or mock for 4 hours and were UV-treat twice, each with the irradiation intensity at 600 mJ/cm2. The plant was ground to powder with liquid nitrogen, and solubilized with 2 mL of extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Igepal CA-630, 5 mM DTT, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, protease inhibitor, and 80 U/mL SUPERase-In RNase inhibitor). 100 μL supernatant was used as input. The RNA-GRP7-GFP complexes were enriched from the remaining supernatant by immunoprecipitation using GFP-trap beads for 2 h at 4 °C with constant rotation. The GFP-Trap beads were washed with washing buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Igepal CA-630, and 0.1% SDS) four times. To elute the protein–RNA complexes, the beads were incubated with 50 μL of RIP elution buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS and 80 U/mL RNase inhibitor) at room temperature for 10 min with rotation. The protein was degraded by proteinase K, and co-precipitated RNAs were eluted by 1 mL TRIzol of RNA extraction reagent. The RNA sample was incubated with DNase I and reverse-transcribed using cDNA synthesis kit (TIANGEN, KR116) for qPCR. In parallel, input samples were used for quantification. The primers used for qPCR are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Workflow and quality control of RIP-qPCR. (a) The workflow of RIP-qPCR. (b) Western blot analysis was utilized to assess the immunoprecipitation efficiency of GRP7-GFP in RIP experiments.

Table 1.

Primers used in RIP-qPCR assay.

| Name | Forward primer sequence (5′-3′) | Reverse primer sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| GRP7 | GCGACGTTATTGATTCCAAG | CGCATCCTTCATGGCTTT |

| HSPRO2 | GCGATGAAGCTTTACGCGAG | GTTCATCTCCGCACTTCCCA |

| CCL | GCTGAAGCATGCGAAGTAATC | CTGTCAACGGGCTCTGAAG |

| ASPG1 | TTTCTTTCTCTCCTCGCCGT | TGGTGAGTGAGGAACGAGTC |

| SVB2 | GTTCAAGACACCGACCACAC | CAGCCTCCTTGATTGCAACA |

| RHIP1 | ATTGGTGTCGCTGCTAGTCT | TAAAGCCGTCCTCTCAAGCA |

Data Records

The raw sequence data of RNA-seq, Ribo-seq, and CLIP-seq in this study were deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (https://bigd.big.ac.cn/gsa)39 in National Genomics Data Center40 under accession number CRA01279841 and also been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive under BioProject accession number PRJNA115722342.

Technical Validation

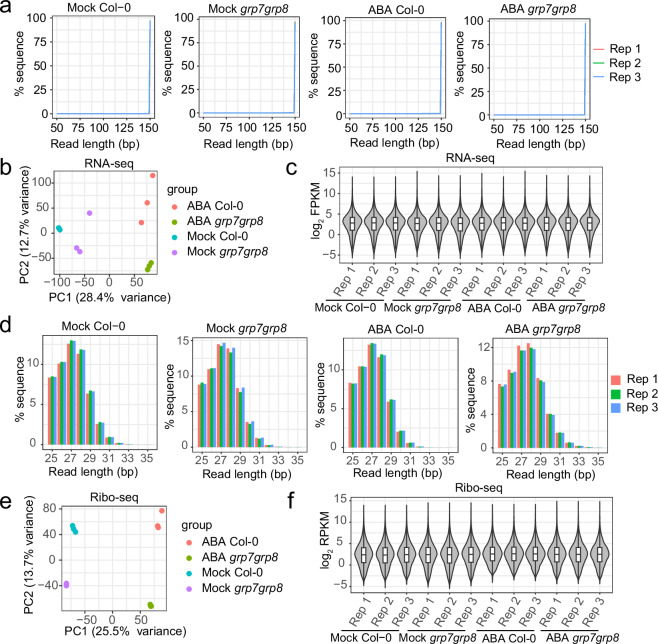

RNA-seq reads quality validation

A total of 12 RNA-Seq runs were conducted, with each sample yielding at least 11 million reads. After trimming the sequencing reads based on quality scores and nucleotide length, over 97.9% of the reads were retained, with almost all clean reads measuring 150 bp (Table 2, Fig. 3a), consistent with the sequencing protocol. This indicates high sequencing quality. The remaining reads were then used as input to generate sequencing quality control (QC) reports using FastQC to validate the quality of the reads.

Table 2.

Summary of the RNA-seq reads.

| Gene type | Condition | Replicate | Number of raw reads | Number of clean reads | Number of mapped reads | Percentage of mapped reads (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col-0 | Mock | 1 | 11,853,539 | 11,657,671 | 11,288,456 | 96.83 |

| 2 | 11,970,758 | 11,728,287 | 11,346,928 | 96.75 | ||

| 3 | 11,483,643 | 11,280,723 | 10,854,437 | 96.22 | ||

| ABA | 1 | 11,270,781 | 11,117,391 | 10,292,940 | 92.58 | |

| 2 | 11,423,784 | 11,261,007 | 10,671,491 | 94.76 | ||

| 3 | 11,463,794 | 11,326,890 | 10,539,262 | 93.05 | ||

| grp7grp8 | Mock | 1 | 11,376,537 | 11,206,438 | 10,332,340 | 92.20 |

| 2 | 12,224,333 | 12,023,968 | 11,618,924 | 96.63 | ||

| 3 | 11,394,860 | 11,215,903 | 10,897,650 | 97.16 | ||

| ABA | 1 | 11,530,883 | 11,302,005 | 10,936,857 | 96.77 | |

| 2 | 11,371,427 | 11,141,485 | 10,784,762 | 96.80 | ||

| 3 | 11,454,954 | 11,217,286 | 10,465,179 | 93.30 |

Fig. 3.

Reads quality and technical validation of RNA-seq and Ribo-seq samples of Col-0 and grp7grp8 with ABA or mock treatment. (a) Length distribution of clean reads from RNA-seq. (b) PCA plot of RNA-seq mapped reads of each gene. (c) Violin and box plot of the log2 FPKM of RNA-seq. (d) Length distribution of clean reads from Ribo-seq. (e) PCA plot of Ribo-seq mapped reads of each gene. (f) Violin and box plot of the log2 RPKM of Ribo-seq.

Assessment of RNA-seq data

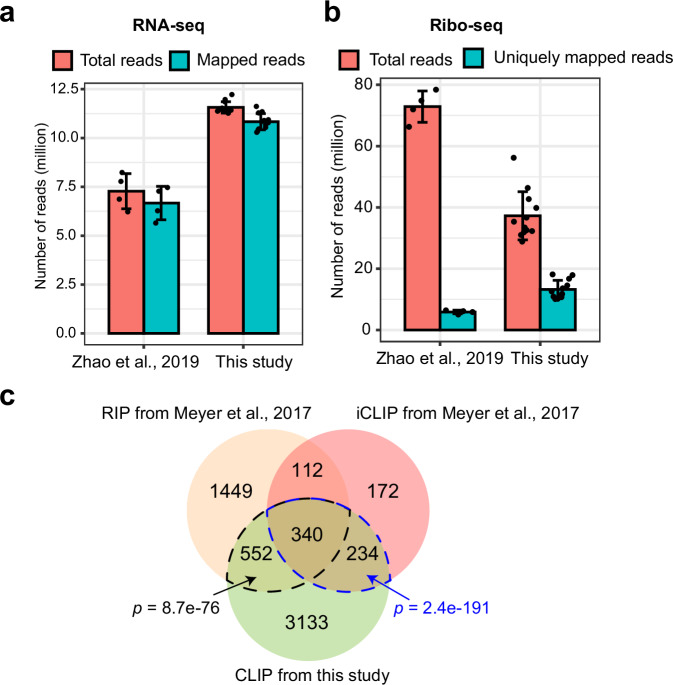

All clean reads were mapped to the TAIR10 reference genome, with each library yielding over 10 million mapped reads and achieving a mapping rate exceeding 92% (Table 2). This substantial dataset facilitates accurate gene expression analysis and surpasses the data volume of comparable published study34 (Fig. 4a). The number of mapped reads for each gene was counted using featureCounts and normalized to FPKM values. Each Col-0 or grp7grp8 sample included three biological replicates, with Pearson correlation coefficients among these replicates exceeding 0.98 (Table 3). The level of correlation is comparable to or higher than that reported in similar studies34,43,44, indicating robust reproducibility of our RNA-seq data. Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted in R using these normalized expression values, confirming the high reproducibility of the sequencing data and clearly distinguishing between different genotypes and treatments (Fig. 3b). The distribution of log2(FPKM) values ranged broadly from -5 to 15 across different samples (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 4.

Statistics of sequencing data and results in this study and published data. (a) Number of total reads and mapped reads in RNA-seq libraries of Zhao et al.34 and this study. The statistic data is derived from Table S10 in Zhao et al.34. (b) Number of total reads and uniquely mapped reads in Ribo-seq libraries of Zhao et al.34 and this study. The statistic data is derived from Table S9 in Zhao et al.34. (c) Venn diagrams of GRP7 target genes identified through different methods. RIP-seq and iCLIP-seq results are derived from Table S2 and S4 in Meyer et al.22, respectively, while the CLIP-seq results are obtained from this study. Hypergeometric tests were used to calculate the p values for the enrichment of genes.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficient between different biological replicates of RNA-seq, Ribo-seq and CLIP-seq samples.

| Type | Samples | Samples group | Pearson correlation coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq | Mock Col-0 | rep1 vs. rep2 | 0.992 |

| rep1 vs. rep3 | 0.991 | ||

| rep2 vs. rep3 | 0.991 | ||

| Mock grp7grp8 | rep1 vs. rep2 | 0.988 | |

| rep1 vs. rep3 | 0.987 | ||

| rep2 vs. rep3 | 0.991 | ||

| ABA Col-0 | rep1 vs. rep2 | 0.986 | |

| rep1 vs. rep3 | 0.987 | ||

| rep2 vs. rep3 | 0.99 | ||

| ABA grp7grp8 | rep1 vs. rep2 | 0.992 | |

| rep1 vs. rep3 | 0.99 | ||

| rep2 vs. rep3 | 0.989 | ||

| Ribo-seq | Mock Col-0 | rep1 vs. rep2 | 0.984 |

| rep1 vs. rep3 | 0.983 | ||

| rep2 vs. rep3 | 0.983 | ||

| Mock grp7grp8 | rep1 vs. rep2 | 0.989 | |

| rep1 vs. rep3 | 0.987 | ||

| rep2 vs. rep3 | 0.987 | ||

| ABA Col-0 | rep1 vs. rep2 | 0.966 | |

| rep1 vs. rep3 | 0.967 | ||

| rep2 vs. rep3 | 0.97 | ||

| ABA grp7grp8 | rep1 vs. rep2 | 0.983 | |

| rep1 vs. rep3 | 0.983 | ||

| rep2 vs. rep3 | 0.982 | ||

| CLIP-seq | Mock pGRP7::GRP7-GFP grp7 | rep1 vs. rep2 | 0.847 |

| ABA pGRP7::GRP7-GFP grp7 | rep1 vs. rep2 | 0.887 |

Ribo-seq reads quality validation

In line with the transcriptome analysis, a total of 12 ribosome profiling libraries were constructed, with each library yielding an average of 37.26 million reads (Table 4). The raw sequencing data were initially filtered using fastp, which included trimming poly(A) adapters and filtering out low-quality and short reads. The first three nucleotides of Read 1, originating from the template-switching oligo, were also trimmed before mapping. The processed reads from each sample were then mapped to the non-coding RNA sequence in the TAIR10 genome, and any reads that aligned were removed. During this step, approximately 2.20% to 6.21% of the clean reads were filtered out (Table 4). The majority of the remaining clean reads (unaligned reads) fell within the 25–35 nt range, with 27 or 28 nt representing the largest proportion (Fig. 3d).

Table 4.

Summary of the Ribo-seq reads.

| Gene type | Condition | Replicate | Number of raw reads | Number of clean reads | After remove ncRNA | Uniquely mapped reads | Percentage of Uniquely mapped reads (%) | Mapped reads within CDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col-0 | Mock | 1 | 36,680,665 | 23,713,458 | 23,088,433 | 12,605,586 | 54.60 | 3,639,375 |

| 2 | 31,013,398 | 21,307,130 | 20,739,296 | 11,692,363 | 56.38 | 3,223,834 | ||

| 3 | 28,838,006 | 19,599,188 | 19,090,235 | 10,712,091 | 56.11 | 2,941,111 | ||

| ABA | 1 | 32,559,042 | 23,563,852 | 23,045,378 | 13,583,164 | 58.94 | 1,293,694 | |

| 2 | 39,828,919 | 28,784,444 | 28,110,183 | 16,714,091 | 59.46 | 1,579,503 | ||

| 3 | 42,711,145 | 30,857,713 | 30,117,546 | 17,905,645 | 59.45 | 1,684,943 | ||

| grp7grp8 | Mock | 1 | 46,342,962 | 30,062,441 | 29,115,084 | 14,516,651 | 49.86 | 5,302,471 |

| 2 | 56,190,279 | 36,740,995 | 35,665,597 | 18,137,651 | 50.85 | 6,280,516 | ||

| 3 | 35,340,688 | 23,791,037 | 23,070,432 | 11,767,806 | 51.01 | 4,062,081 | ||

| ABA | 1 | 33,426,634 | 23,182,728 | 21,811,662 | 10,905,432 | 50.00 | 2,861,028 | |

| 2 | 32,271,972 | 22,017,031 | 20,675,021 | 10,167,630 | 49.18 | 2,694,184 | ||

| 3 | 31,895,956 | 22,071,314 | 20,701,214 | 10,096,134 | 48.77 | 2,864,056 |

Assessment of Ribo-seq data

The remaining clean reads were aligned to the reference genome, with a significant fraction mapping to multiple genomic positions due to highly repetitive regions. Specifically, approximately 6.16 to 13.54 million reads (26.16% to 42.07% of the remaining clean reads) were mapped to multiple loci in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome, while 10.10 to 18.14 million reads (48.77% to 59.46% of the remaining clean reads) were uniquely mapped (Table 4). These results indicate that non-specific mapping accounted for a substantial portion of the total mapping reads in the Ribo-seq library. Each Ribo-seq library yielded over 10 million uniquely mapped reads. Notably, despite having fewer raw reads than published studies34, our libraries demonstrated a higher number of uniquely mapped reads, highlighting their quality (Fig. 4b). For each Ribo-seq sample, three biological replicates were established, with Pearson correlation coefficients exceeding 0.96 among the replicates. This level of correlation is comparable to or higher than that reported in similar studies34,43,44 (Table 3), indicating strong reproducibility of our Ribo-seq data. PCA confirmed high reproducibility among biological replicates and successfully distinguished between different genotypes and treatments (Fig. 3e). The distribution of log2(RPKM) values ranged broadly from -5 to 15 across the samples (Fig. 3f).

CLIP-seq reads quality validation

A total of 8 CLIP-Seq libraries were constructed, each yielding approximately 21 to 32 million raw reads. After quality control using fastp, we obtained over 20 million reads for each immunoprecipitated (IP) sample (pGRP7::GRP7-GFP grp7-1) and between 5 and 13 million reads for each control sample (Col-0) (Table 5). The length of the clean reads ranges from 15 bp to 150 bp, with the majority falling between 20 bp and 80 bp (Fig. 5a). The remaining reads were analyzed using FastQC to assess read quality.

Table 5.

Summary of the CLIP-seq reads.

| Gene type | Condition | Replicate | Number of raw reads | Number of clean reads | Number of mapped reads | Percentage of mapped reads (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pGRP7::GRP7-GFP grp7-1 | Mock | 1 | 28,649,269 | 22,609,323 | 5,981,799 | 26.46 |

| 2 | 32,064,065 | 27,653,738 | 7,460,803 | 26.98 | ||

| ABA | 1 | 26,400,749 | 22,247,502 | 5,917,161 | 26.60 | |

| 2 | 24,888,071 | 20,469,515 | 5,277,851 | 25.78 | ||

| Col-0 | Mock | 1 | 21,904,509 | 6,940,377 | 1,371,640 | 19.76 |

| 2 | 26,094,680 | 5,111,750 | 1,000,950 | 19.58 | ||

| ABA | 1 | 26,725,733 | 12,828,783 | 1,868,005 | 14.56 | |

| 2 | 22,517,618 | 13,068,141 | 2,044,487 | 15.64 |

Fig. 5.

Reads quality and technical validation of CLIP-seq of Col-0 and pGRP7::GRP7-GFP grp7-1 with ABA or mock treatment. (a) Length distribution of clean reads from CLIP-seq. (b) IGV genome browser tracks show significant CLIP crosslink sites on GRP7 target transcripts. GLYCINE-RICH RNA-BINDING PROTEIN 7 (GRP7), SVB-LIKE (SVB2), ORTHOLOG OF SUGAR BEET HS1 PRO-1 2 (HSPRO2), ASPARTIC PROTEASE IN GUARD CELL 1 (ASPG1) and CCR-LIKE (CCL). (c) RIP-qPCR analysis of CLIP targets that are showed in (b) in pGRP7::GRP7-GFP grp7-1 and Col-0 under ABA or mock treatment. The levels in the GFP-trap precipitate are presented relative to the levels in the input. The values represent the means ± SD of three replicates. Student’s t test: ns, no significant; **, p < 0.01; ****, p < 0.0001. RHIP1 as unbound transcripts serve as negative control.

Assessment of CLIP-seq data

The mapping of clean reads to the TAIR10 reference genome yielding a mapping rate of 14.56% to 26.98% (Table 5). High pearson correlation coefficients of CPM values indicate strong reproducibility between replicates (Table 3). A previous study outlined the binding landscape of GRP7 using RIP-seq and iCLIP-seq methods to identify GRP7 target genes22. In our research, we employed CLIP-seq and identified a larger number of GRP7 target genes, with significant overlap with those identified in the previous study (Fig. 4c). The BAM files from the CLIP-seq data were converted to bigwig format using bamCoverage and visualized with the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV)45, highlighting significant binding peaks in IP samples (pGRP7::GRP7-GFP grp7-1) compared to control samples (Col-0) (Fig. 5b). Notable genes such as GRP7 (AT2G21660)4, SMALLER TRICHOMES WITH VARIABLE BRANCHES-LIKE (SVB2, AT1G09310)46, and ASPARTIC PROTEASE IN GUARD CELL 1 (ASPG1, AT3G18490)47, which are involved in ABA response, were identified, along with the circadian clock-regulated CCR-LIKE (CCL, AT3G26740)48 and ORTHOLOG OF SUGAR BEET HS1 PRO-1 2 (HSPRO2, AT2G40000)49, linked to basal disease resistance (Fig. 5b). RIP-qPCR assays confirmed that GRP7 binds to the mRNAs of GRP7, SVB2, ASPG1, CCL, and HSPRO2 under both ABA and mock treatments, while the negative control RGS1-HXK1 INTERACTING PROTEIN 1 (RHIP1, AT4G26410)50, which encodes a protein to have a 3-stranded helical structure that is required for some glucose-regulated gene expression, showed no enrichment (Fig. 5c). Western blot analysis reveals that the GRP7-GFP fusion protein exhibits a high level of immunoprecipitation efficiency (Fig. 2b). The overall reads quality, mapping rates, and binding efficiency underscore the high quality of our CLIP-seq libraries.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Wenfeng Qian (Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, the Chinese Academy of Science) for supporting Ribo-seq analysis. We thank Professors Dorothee Staiger (Bielefeld University, Germany) and Yiliang Ding (John Innes Centre, UK) for providing pGRP7::GRP7-GFP grp7-1 complementary line. This work is supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation Outstanding Youth Project (JQ23026), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1201500), and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA24010204).

Author contributions

J.X. conceived and supervised the study. J.Z. performed the experiments; Y.-X. X. performed bio-informatics analysis. J.X., J.Z. and Y.-X.X. wrote the manuscript.

Code availability

Code used for all processing and analysis is available at Github (https://github.com/yx-xu/GRP7-mediate-translational-regulation).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jing Zhang, Yongxin Xu.

References

- 1.Chen, K. et al. Abscisic acid dynamics, signaling, and functions in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol62, 25–54 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng, L. M., MELCHER, K., THE, B. T. & XU, H. E. Abscisic acid perception and signaling: structural mechanisms and applications. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica35, 567–584 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo, J. et al. Involvement of Arabidopsis RACK1 in Protein Translation and Its Regulation by Abscisic Acid. Plant Physiol.155, 370–383 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang, J. et al. Unveiling the regulatory role of GRP7 in ABA signal-mediated mRNA translation efficiency regulation. Preprint at 10.1101/2024.01.12.575370 (2024).

- 5.Yuan, S., Zhou, G. & Xu, G. Translation machinery: the basis of translational control. Journal of Genetics and Genomics51, 367–378 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodnina, M. V. The ribosome in action: Tuning of translational efficiency and protein folding. Protein Science25, 1390–1406 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu, Y., Beyer, A. & Aebersold, R. On the Dependency of Cellular Protein Levels on mRNA Abundance. Cell165, 535–550 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingolia, N. T., Ghaemmaghami, S., Newman, J. R. S. & Weissman, J. S. Genome-Wide Analysis in Vivo of Translation with Nucleotide Resolution Using Ribosome Profiling. Science324, 218–223 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ingolia, N. T., Brar, G. A., Rouskin, S., McGeachy, A. M. & Weissman, J. S. The ribosome profiling strategy for monitoring translation in vivo by deep sequencing of ribosome-protected mRNA fragments. Nat Protoc7, 1534–1550 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brar, G. A. & Weissman, J. S. Ribosome profiling reveals the what, when, where and how of protein synthesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol16, 651–664 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu, Q. et al. Ribo-uORF: a comprehensive data resource of upstream open reading frames (uORFs) based on ribosome profiling. Nucleic Acids Research51, D248–D261 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burd, C. G. & Dreyfuss, G. Conserved Structures and Diversity of Functions of RNA-Binding Proteins. Science265, 615–621 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho, J. J. D. et al. A network of RNA-binding proteins controls translation efficiency to activate anaerobic metabolism. Nat Commun11, 2677 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma, L. et al. Roles of Plant Glycine-Rich RNA-Binding Proteins in Development and Stress Responses. IJMS22, 5849 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, J. S. et al. Glycine-rich RNA-binding protein7 affects abiotic stress responses by regulating stomata opening and closing in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal55, 455–466 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, J. Y. et al. Glycine-rich RNA-binding proteins are functionally conserved in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa during cold adaptation process. Journal of Experimental Botany61, 2317–2325 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao, J. et al. AtJAC1 Regulates Nuclear Accumulation of GRP7, Influencing RNA Processing of FLC Antisense Transcripts and Flowering Time in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol.169, 2102–2117 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Streitner, C. et al. An hnRNP-like RNA-binding protein affects alternative splicing by in vivo interaction with transcripts in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Research40, 11240–11255 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu, F. et al. Phase separation of GRP7 facilitated by FERONIA-mediated phosphorylation inhibits mRNA translation to modulate plant temperature resilience. Molecular Plant17, 460–477 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicaise, V. et al. Pseudomonas HopU1 modulates plant immune receptor levels by blocking the interaction of their mRNAs with GRP7. EMBO J32, 701–712 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmal, C., Reimann, P. & Staiger, D. A Circadian Clock-Regulated Toggle Switch Explains AtGRP7 and AtGRP8 Oscillations in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Comput Biol9, e1002986 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer, K. et al. Adaptation of iCLIP to plants determines the binding landscape of the clock-regulated RNA-binding protein AtGRP7. Genome Biol18, 204 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics34, i884–i890 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics30, 923–930 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq. 2. Genome Biol15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu, Z., Eils, R. & Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics32, 2847–2849 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calviello, L. et al. Detecting actively translated open reading frames in ribosome profiling data. Nat Methods13, 165–170 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang, Y. et al. OsNSUN2-Mediated 5-Methylcytosine mRNA Modification Enhances Rice Adaptation to High Temperature. Developmental Cell53, 272–286.e7 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunningham, F. et al. Ensembl 2022. Nucleic Acids Research50, D988–D995 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao, Z., Zou, Q., Liu, Y. & Yang, X. Genome-wide assessment of differential translations with ribosome profiling data. Nat Commun7, 11194 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Nostrand, E. L. et al. Robust transcriptome-wide discovery of RNA-binding protein binding sites with enhanced CLIP (eCLIP). Nat Methods13, 508–514 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao, T. et al. Impact of poly(A)-tail G-content on Arabidopsis PAB binding and their role in enhancing translational efficiency. Genome Biol20, 189 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovci, M. T. et al. Rbfox proteins regulate alternative mRNA splicing through evolutionarily conserved RNA bridges. Nat Struct Mol Biol20, 1434–1442 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics26, 841–842 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu, G., Wang, L.-G., Han, Y. & He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: an R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology16, 284–287 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong, J. et al. ALBA proteins confer thermotolerance through stabilizing HSF messenger RNAs in cytoplasmic granules. Nat. Plants8, 778–791 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen, T. et al. The Genome Sequence Archive Family: Toward Explosive Data Growth and Diverse Data Types. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics19, 578–583 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.CNCB-NGDC Members and Partners. et al. Database Resources of the National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation in 2022. Nucleic Acids Research50, D27–D38 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Genomics Data Centerhttps://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA020137 (2024).

- 42.NCBI Sequence Read Archivehttps://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP530528 (2024).

- 43.Xiang, Y. et al. Pervasive downstream RNA hairpins dynamically dictate start-codon selection. Nature621, 423–430 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu, G. et al. Global translational reprogramming is a fundamental layer of immune regulation in plants. Nature545, 487–490 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robinson, J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol29, 24–26 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hussain, S. et al. Involvement of ABA Responsive SVB Genes in the Regulation of Trichome Formation in Arabidopsis. IJMS22, 6790 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yao, X., Xiong, W., Ye, T. & Wu, Y. Overexpression of the aspartic protease ASPG1 gene confers drought avoidance in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany63, 2579–2593 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lidder, P., Gutiérrez, R. A., Salomé, P. A., McClung, C. R. & Green, P. J. Circadian Control of Messenger RNA Stability. Association with a Sequence-Specific Messenger RNA Decay Pathway. Plant Physiology138, 2374–2385 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murray, S. L., Ingle, R. A., Petersen, L. N. & Denby, K. J. Basal Resistance Against Pseudomonas syringae in Arabidopsis Involves WRKY53 and a Protein with Homology to a Nematode Resistance Protein. MPMI20, 1431–1438 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang, J.-P., Tunc-Ozdemir, M., Chang, Y. & Jones, A. M. Cooperative control between AtRGS1 and AtHXK1 in a WD40-repeat protein pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- NCBI Sequence Read Archivehttps://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP530528 (2024).

Data Availability Statement

Code used for all processing and analysis is available at Github (https://github.com/yx-xu/GRP7-mediate-translational-regulation).