Abstract

Bisphenol A (BPA) is a chemical produced in large quantities for use primarily in the production of polycarbonate plastics, which has risks for human health. This study aimed to investigate BPA contents in canned fruit and vegetable samples using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). Furthermore, health risks were assessed for Iranian adults and children using Monte Carlo simulations. The mean concentration of BPA in canned samples of lentils, apricots, cherries, pineapples, eggplant stew, and green peas was 21.87, 4.52, 3.92, 1.86, 1.67 and 1.62 µg/kg, respectively. The level of BPA in the samples was within the standard level. The pH value in canned fruits varied from 3.6 to 4.7 (mean = 4.15) and in canned vegetables from 4.3 to 5.9 (mean = 5.21). The mean sugar content was 41.42% (ranged 38–48%), and the mean fat value was 24.234% (ranged 24.7–48%). The 95th percentile EDI values of BPA in canned fruit for adults and children were 6.12E-08, and 2.16E-07 mg/kg bw/day; and in canned vegetables were 1.78E-07, and 6.26E-07 mg/kg bw/day, respectively. The 95th percentile THQ values in canned fruit for adults and children were 1.48E-06 and 5.24E-06, and in canned vegetables were 3.56E-06 and 1.27E-05, respectively, and HQ was less than 1. According to the obtained results, it can be concluded that the contents of BPA in canned fruits and vegetables do not pose a safety concern for consumers in Iran.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-82758-0.

Keywords: Bisphenol A, Canned food, Fruit compote, Food safety, GC-MS

Subject terms: Environmental sciences, Chemistry

Introduction

Canned foods refer to products that undergo a canning process, including pretreatment, filling, sealing, and sterilizing the can. In fact, canning is a food preservation method, especially for perishable foods such as vegetables, fruits, and meat1,2. Canned products provide valuable nutrients such as carbohydrates, vitamins, proteins, and minerals. Despite the significant advantages of various packaging techniques, contact between food and packaging materials can cause chemical reactions and leakage of packaging material compounds into the food3,4. The inner coating of metal cans is made using epoxy resins (polymer coating) to prevent unwanted contact and reactions between the inner surface of the cans and food, and as a result, erosion and rust are prevented5,6.

Since the 1960s, bisphenol A [2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)propane; BPA] has been widely utilized in the manufacturing of polycarbonate plastics, epoxy resins, and stabilizer agents in polyvinyl chloride7. BPA is an artificial organic substance (generated by blending phenol and acetone) featuring two phenolic rings linked via a variously substituted carbon atom and also has two methyl functional groups8. The BPA migration process is usually physical and chemical. Physical migration occurs due to the release of residual BPA after the manufacturing process, while chemical migration occurs when BPA is released from the polymer surface as a result of hydrolysis9. BPA primarily leaches into canned food under acidic conditions, during high-temperature processing, and from incompletely polymerized epoxy resins6,8.

There is scientific evidence that BPA acts as an endocrine-disrupting exogenous chemical capable of altering hormones, mimicking the action of the hormone estrogen, and causing significant adverse effects on reproductive abilities. The ability of BPA to mimic estrogen is related to its hydroxyl groups in the para position10. Moreover, some research has shown that BPA exposure may increase the risk of certain diseases, including, obesity, autism, diminished antioxidant enzymes, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, and cancers11,12.

BPA is detected across various environmental media and both dietary and non-dietary exposure to BPA is possible. Nevertheless, the most common pathway of its exposure is the ingestion of food, which poses major hazards to vulnerable populations such as children and the elderly13. Public concerns and government regulations have motivated the development and manufacture of alternative materials to BPA, for example, BPS, BPF, BPB, and BPAF have been utilized as substitutes for polycarbonate plastic or resin. Currently, BPA is one of the most common xenoestrogens studied in food samples. However, there have been cases where other analog compounds have been found in higher amounts, indicating that manufacturing companies are gradually replacing BPA with other bisphenols in food packaging3,14,15. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that BPF and BPS have demonstrated estrogenic and/or antiandrogenic properties that are comparable to or even greater than those of BPA16. BPA attracts considerable attention because of its adverse health effects, its presence in a diverse range of food products, and its pervasive occurrence in the environment7. The EU Commission has fixed a maximum migration limit of 600 µg/kg for BPA in food products17. Also, on February 9, 2024, the European Commission issued a draft regulation to ban bisphenol A (BPA, CAS 80-05-7) and other bisphenols in food contact materials18. The proposal includes a 36-month transition period for varnishes, coatings, and equipment used in professional production before enforcing the BPA ban.

The maximum permissible concentration and the tolerable daily intake (TDI) of BPA were set at 50 µg/kg bw/day by the U.S. EPA19 and the EFSA20, respectively. Also, Health Canada recommended the provisional TDI of BPA at 25 µg/kg bw/day21.

Bisphenol analysis is often carried out by employing chromatographic techniques, such as Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC-MS)6, ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS)22, and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)23.

The presence of BPA in canned fruits and vegetables has been numerously documented worldwide, including in Belgian (Geens et al. analyzed BPA in 45 canned beverages and 21 canned food and stated the amount of BPA present in food items was dependent on the type of can and sterilisation conditions rather than the type of food)7, in Korea3,23, in Canada (Cao et al. analyzed BPA in 78 canned food products and stated concentrations of BPA in canned food products differed considerably among food types, but all were below the specific migration limit of 0.6 mg/kg set by the European Commission Directive for BPA in food or food simulants)24, in China (Cao et al. analyzed BPA in 151 canned product samples and stated canned products contributed significantly for BPA and BPF exposure to children and adult in China)25, the United States26–28, and in France (Bermeh et al. analyzed BPA in some food products and stated the ubiquitous presence of this contaminant in foods with a background level of contamination of less than 5 µg/kg in 85% of the 1498 analysed samples and high levels of contamination (up to 400 µg/kg) were found in some foods of animal origin)29.

However, information on BPA content in canned fruits and vegetables sold in Iran is not available, and on the other hand, consumption of these canned foods is high in Iran and the world. Thus, the present study aimed to (1) investigate BPA levels in some canned fruits and vegetables in Tehran, Iran, (2) evaluate some variables in canned fruits and vegetables concerning the BPA concentration, including the pH and the contents of fat and sugar, and (3) assess the health risks associated with exposure to BPA from the consumption of canned fruits and vegetables using Monte Carlo simulations method.

Materials and methods

Reagents

All chemicals were of analytical grade. BPA was supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (West Chester, PA; USA). Acetonitrile (CAS #: 75-05-8), n-hexane (CAS #: 110-54-3), magnesium sulfate (CAS #: 7487-88-9), sulfuric acid (CAS #: 7664-93-9), sodium chloride (NaCl) (CAS #: 7647-14-5), methylene blue (CAS #: 7220-79-3), Fehling’s solution (CAS #: 7758-99-8), potassium carbonate (CAS #: 584-08-7), sucrose (CAS #: 57-50-1), acetic anhydride (CAS #: 108-24-7), tetrachloroethylene (CAS #: 127-18-4), and isoamyl alcohol (CAS #: 123-51-3) were purchased from Merck Co., (Darmstadt, Germany).

Sample collection

In total, 96 samples (considering double sampling) including canned fruit (cherry, pineapple, and apricot) and canned vegetables (eggplant Stew, lentils, and green peas) were purchased from supermarkets of Tehran, Iran. All samples were canned in metal containers, with a volume of 350 g. Collected samples were divided into two groups based on their production time: 5–6 months and 11–12 months. These two groups were stored in two different conditions: environment temperature (25 °C) and refrigerator temperature (4 °C) for 1 month until analysis. Subsequently, the samples were labeled and transferred to the laboratory and kept at mentioned conditions until further analysis.

The color of the contents of stewed eggplant is dark brown, canned lentils are dark brown, canned peas are light green, canned cherries are dark red, canned pineapple is light yellow or golden, and canned apricots are orange or yellow.

Bisphenol A measurement

Sample preparation and derivatization

Initially, 2 g of the homogenized canned fruit and vegetable samples were added to 5 mL of acetonitrile and vortexed for 1 min, then 4 mL n-hexane was added and vortexed for 2 min. The mixture was ultrasonicated for 20 min with 4 cycles of 5 min each. Then, it was centrifuged at 3500 rev/s for 5 min and the n-hexane layer was removed. Finally, the mixture was filtered using folded filter paper, and then 4 mL n-hexane was added. The obtained mixture was transported to a vial, and 50 µL of MSTFA derivatives were added to it7,24,30,31. The vial was put in an oven at 50 °C for 1 h, then it was injected into the GC-MS.

Sample analysis

The analysis of samples was carried out using Gas Chromatography (Agilent 7890, Palo Alto, CA, USA) with a mass spectrometric detector (Agilent 5975), and equipped with a capillary column (HP5-MS; Column length: 30 m; internal diameter: 0.25 mm; film thickness: 0.25 μm). The GC-MS operating conditions were: the gas of carrier: helium (99.999%); rate of flow: 1 mL per minute; the mode of injection: splitless; the volume of injection: 2 µL. The temperature instructions of the oven were as follows: the temperature of the injector: 280 °C, the temperature initial: 100 °C with 1 min hold, ramp to 225 °C for 5 min at 20 °C/min, and then ramp to 325 °C at 35 °C/min and held for 1 min. Ultimately, the SIM (selected ion monitoring) mode was (with 212 m/z) utilized for the detector3,5,24.

The correlation coefficient (R2) of the curve was 0.991. The detection limits (LOD) and detection quantifications (LOQ) for bisphenol A were 0.1 and 0.35 ng/g, respectively. The relative standard deviation (RSD) was 8.9% and the recovery rate was 99.8%. Figure S1 displays the regression equation, while Fig. S2 presents the standard chromatogram.

Fat measurement

The fat content in the sample was measured according to the AACC method 30 − 10. First, samples were dried at 105 °C. Then, 4 g of dried sample was accurately weighed, placed onto a filter paper, and wrapped, then transported to a Soxhlet extractor with a flask containing n-hexane. The sample was extracted constantly for 3 h at 70 °C. The samples were put in an oven at 100 °C on a rotary and then transferred to a desiccator until cooled down. The fat content was measured by weighing32,33.

Sugar measurement

First, 25 g of sample with 6–10 mL of hydrochloric acid were added to a 100 mL volumetric flask and then placed in a water bath for 10 min at 70 °C. Then, the volumetric flask was cooled, a few drops of phenolphthalein were added to it and it was neutralized with 40% sodium hydroxide and 0.1 N sodium hydroxide to create a stable light pink color. Next, 5 mL of Fehling solution A and 5 mL of Fehling solution B were poured into the Erlenmeyer flask and mixed. Following that, a few glass balls, 3 to 4 drops of methylene blue, and about 20 mL of distilled water were added to the Erlenmeyer flask. The obtained solution was heated on a hot plate until it boiled for 2 min. Then was poured the neutralized solution into the burette and while boiling Fehling’s solution, slowly added the neutralized solution to the Erlenmeyer until it turned the brownish-red color of Cu2O. The consumption volume of was recorded34.

| 1 |

In Eq. 1., F is the Fehling factor; V is the volume of solution consumed in mL, and N is total sugars (sugar after hydrolysis) in grams per % gram.

pH measurement

For this purpose, 10 g of sample was added to 100 mL distilled water, then the pH of the mixture was examined utilizing an electronic pH meter (Hach, USA)34.

Risk assessment

Estimated daily intake (EDI) and target hazard quotient (THQ) were used to the estimation the health risk of BPA in canned fruits and vegetables. and calculated by the following equations35:

| 2 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

Where the estimated daily intake (EDI) is an estimate of the amount of BPA in canned fruit and vegetables that can be consumed daily over a lifetime without presenting an appreciable health risk, the target hazard quotient (THQ) is the ratio of the potential exposure to a substance and the level at which no adverse effects are expected36,37. C is the concentration of BPA in samples (µg/kg), and IR is the mean canned fruit and vegetables ingestion rate for consumers in Iran (1 g/person/day), which is according to the Study on Household Food of Consumption Patterns and Nutritional Status of I.R38–40. BW is body weight (70 kg for adults, and 20 kg for children)41, and The ingestion exposure frequency (EFi) is the number of days per year a person is exposed to the BPA is 350 days for both age groups)42, ED is exposure duration (years), AT is the average time lifespan (EF×ED) (adults and children are 25550 and 2190 days, respectively)43. Additionally, the 95th percentile risk values were provided to highlight notable risks44. The RfD is useful as a reference point from which to gauge the potential effects of the chemical at other doses (50 µg/kg/day for BPA)19. Based on the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) US Environmental Protection Agency, The oral Reference Dose (RfD) assumes that certain toxic effects, like cellular necrosis, have thresholds. It estimates the daily exposure for the general human population, including sensitive subgroups, that is unlikely to pose a significant risk of harmful effects over a lifetime, with an uncertainty of about an order of magnitude. The EDI values were compared to the fixed tolerable daily intake (TDI) of BPA which was recommended by the EFSA20. In April 2023, EFSA published a re-evaluation of the safety of BPA as used in FCMs, significantly reducing the tolerable daily intake (TDI) set in its previous assessment. In 2015, EFSA set a temporary tolerable daily intake (t-TDI) for BPA at 4 µg/kg body weight. By 2016, the European Commission directed EFSA to reassess BPA’s health risks in food, concluding that BPA is unlikely to pose a direct genotoxic hazard. The immune system was identified as the most sensitive, with a 57–73% probability that the lowest Benchmark Dose for other effects was lower than the reference point (RP). In 2023, based on all the new scientific evidence assessed, an uncertainty factor of 2 was added, resulting in a new TDI of 0.2 ng BPA/kg body weight per day. However, dietary exposures significantly exceeded this TDI, prompting concerns over BPA’s health impacts45. This study conducted a health risk assessment of BPA exposure by examining scenario (1) based on the EPA’s recommended oral Reference Dose and scenario (2) based on the EFSA’s recommended tolerable daily intake for the safety of BPA as used in food contact materials. A Monte Carlo simulation (Oracle@ Crystal Ball, Oracle Corporation, USA) was applied to conduct the uncertainty analysis. The simulation’s input parameters are shown in Table S1.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine the distribution of the study parameters. The results were evaluated by the Spearman Correlation. The significance level was considered p < 0.05. The Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to determine the significance between groups. The principal component analysis is a multivariate technique and is widely used in food contamination to find out the associations between contaminants and food products46,47. In this study, the Monte Carlo simulation was executed using the Oracle Crystal Ball. The trial numbers were set at 10,000 iterations.

Results and discussion

BPA concentrations in the canned fruit and vegetable samples

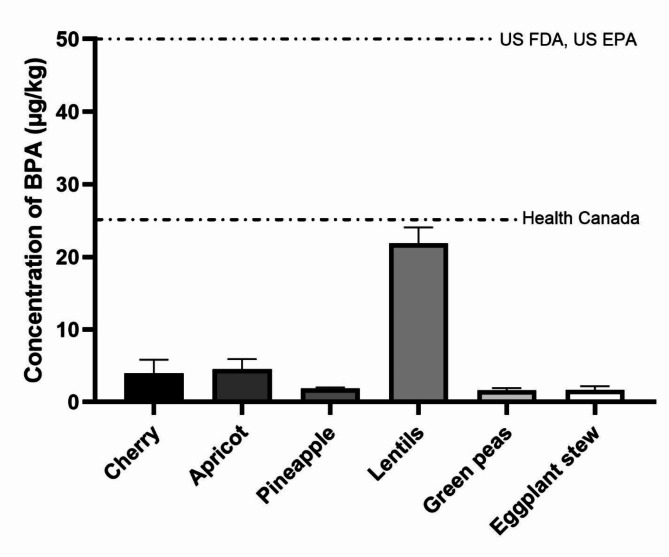

The concentrations of BPA in the selected canned fruit and vegetable samples with their corresponding sugar, fat, and pH values are presented in Table 1. BPA was detected in all samples (LOD = 0.1 µg/kg). The median concentration of BPA was 2.34 µg/kg and an average of 3.44 µg/kg. The concentration of BPA in the canned fruit ranged from 0.87 (cherry, 11–12 months, at 4 °C) to 9.70 µg/kg (cherry, 5–6 months, at 25 °C). The median concentration of BPA in canned vegetables was 2.04 µg/kg and an average of 8.38 µg/kg. The concentration of BPA in the canned vegetables ranged from 0.87 (green peas, 11–12 months, at 4 °C) to 28.35 µg/kg (lentils, 11–12 months, at 25 °C). Similarly to Cunha and Fernandes’s study, the mean concentration of BFA in canned fruits was less than those in canned vegetables, which may linked to employing electrolytic tinplate in fruit containers instead of epoxy films6. As shown in Fig. 1, the descending order of mean concentration of BPA in studied samples was as follows: lentils (21.87 µg/kg) > apricot (4.52 µg/kg) > cherry (3.92 µg/kg) > pineapple (1.86 µg/kg) > eggplant stew (1.67 µg/kg) > green peas (1.62 µg/kg). All samples with a production time of 8–9 months had higher BPA levels when stored at 25 °C compared to those kept at 4 °C, and these findings are in line with previous studies48,49. The results have shown that the amount of BPA in all samples was within the maximum allowable concentrations. However, this does not guarantee that individuals will not be exposed to health hazards, so assessing the health risks of exposure to BPA is necessary. The results of the statistical analysis indicated that there was no significant difference between the contents of BPA, pH, % sugar, % fat, storage conditions, and production time among the different types of studied canned samples (p > 0.005). In comparison, Geens et al. found a statistically significant correlation between the fat content of canned beverages and foods and the content of BPA (p = 0.004).

Table 1.

The contents of BPA, sugar, fat, and pH in the canned fruit and vegetable samples.

| Samples | Production time | Storage conditions | BPA (µg/kg) | Sugar % | Fat % | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cherry | 5–6 months | 25 °C | 2.39 | 38.4 | ND* | 3.6 |

| 4 °C | 0.87 | 38 | ND | 3.7 | ||

| 11–12 months | 25 °C | 9.70 | 38 | ND | 3.6 | |

| 4 °C | 2.75 | 38.4 | ND | 3.9 | ||

| Apricot | 5–6 months | 25 °C | 8.08 | 42 | ND | 4.6 |

| 4 °C | 5.64 | 44 | ND | 4.5 | ||

| 11–12 months | 25 °C | 2.16 | 40 | ND | 4.6 | |

| 4 °C | 2.29 | 40 | ND | 4.7 | ||

| Pineapple | 5–6 months | 25 °C | 1.81 | 48 | ND | 4.2 |

| 4 °C | 1.17 | 47.50 | ND | 4.3 | ||

| 11–12 months | 25 °C | 2.62 | 46.50 | ND | 4.1 | |

| 4 °C | 1.85 | 48 | ND | 4.1 | ||

| Lentils | 5–6 months | 25 °C | 28.35 | ND | 32 | 5.6 |

| 4 °C | 23.41 | ND | 31.5 | 5.5 | ||

| 11–12 months | 25 °C | 11.27 | ND | 32.2 | 5.6 | |

| 4 °C | 24.46 | ND | 31.9 | 5.5 | ||

| Green peas | 5–6 months | 25 °C | 1.73 | ND | 25.3 | 5.9 |

| 4 °C | 0.87 | ND | 25 | 5.8 | ||

| 11–12 months | 25 °C | 1.53 | ND | 24.8 | 5.7 | |

| 4 °C | 2.36 | ND | 24.7 | 5.7 | ||

| Eggplant stew | 5–6 months | 25 °C | 3.37 | ND | 45.1 | 4.3 |

| 4 °C | 1.13 | ND | 45.5 | 4.4 | ||

| 11–12 months | 25 °C | 1.05 | ND | 44.9 | 4.3 | |

| 4 °C | 1.14 | ND | 48 | 4.3 |

*ND: not detectable.

Fig. 1.

The mean concentration of bisphenol A in the canned fruit and vegetable samples. United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA)19, United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA)50, and Health Canada (department of the Government of Canada)21.

The sugar contents in the canned fruits ranged from 38 to 48%, and the mean was 42.41%. The fat contents in the canned vegetables ranged from 24.7 to 48%, and the mean was 34.24%. The descending order of the mean of sugar in canned fruit samples was as follows: pineapple (47.5%) > apricot (41.5%) > cherry (38.2%), and the descending order of the mean of fat in canned vegetable samples was as follows: eggplant stew (45.87%) > lentils (31.90%) > green peas (24.95%). The pH value in the canned fruits ranged from 3.6 to 4.7 (mean = 4.15) and in the canned vegetables ranged from 4.3 to 5.9 (mean = 5.21). The increasing order of mean concentration of pH in studied samples was as follows: cherry (3.7) > pineapple (4.17) > eggplant stew (4.32) > apricot (4.6) > lentils (5.55) > green peas (5.77). Osman et al. reported pH in the canned fruits 3.2–3.8 and in the canned vegetables 2.3–6.68. As the pH increases, BPA migration into the food can accelerate because of the hydrolysis of lacquer51.

The concentration of BPA recorded in the present study compared with those reported in the previous literature are summarized in Table 2, including country, type and number of samples analyzed, mean and range concentrations of BPA, and analytical method. BPA levels in canned fruits found in our study (0.87–9.7 µg/kg) were in line with those reported for canned fruit by Cunha and Fernandes (< 0.3–10.2 µg/kg)6 and Geens et al. (< 0.02–8.1 µg/L)7. Our recorded amount of BPA in canned fruits was more than that reported by Kawamura et al. (< 5 µg/kg)30 and Bemrah et al. (0.105–2.13 µg/kg)29, while lower than those reported by Cao et al. (< LOD – 837 µg/kg)25, Lim et al. (3–54.56 µg/kg)23, and Osman et al. (5.57–233.78 µg/kg). In the study by Gregory et al., BPA levels in canned green beans ranged from 22 to 730 µg/kg, canned pineapple ranged from < 2 to 13 µg/kg, canned sliced peaches ranged from < 2 to 9.3 µg/kg, and canned peas ranged from 3 to 310 µg/kg26. In another study, the concentration of BPA recorded in canned fruits was 0.532 µg/kg, and in canned vegetables, it was 8.99 µg/kg27. Morgan and Clifton reported the amount of BPA in the peaches and Caesar salad was 6 and 1.4, respectively28. The concentration of BPA in canned vegetables in the present study (0.87–28.35 µg/kg) was similar to those reported by Choi et al. (< 1.74–32 µg/kg)3. The concentration of BPA in our study detected in canned vegetables was lower than that reported by Cao et al. (4.3–92 µg/kg)24, Cunha and Fernandes (< 0.3–265.6 µg/kg)6, and Cao et al. (< LOD – 102 µg/kg)25, whereas higher than those reported by Bemrah et al. (3–21.5 µg/kg)29 and Kawamura et al. (< 5–11 µg/kg)30. Multiple factors have been shown to have a role in the migration of BPA into canned food, including food composition (e.g. fat content), duration contact between food and can, temperature and pH values, the thickness of packaging material, and chemical properties and quantity of the migrating component14. Also, the type of packaging material can affect the migration of bisphenol. Geens et al. found BPA contents in foods packaged in PET and glass was less than in foods packaged in canned foods, indicating BPA levels before filling food into the container were minimal and the presence of BPA in food primarily originated from the inner lining of cans7. Other researchers have expressed that BPA migrates from the coating into the food, especially during the sterilization procedure, and after this process, BPA levels do not change throughout storage, even when the container is exposed to high temperatures or becomes damaged by denting52–54. Stojanović et al. reported that BPA concentration in canned meat products varied from 3.2 to 64.8 µg/kg following storage in military facilities and found no correlation between storage period and the contents of BPA. Additionally, high temperatures and acidic foods are the major factors that can contribute to the migration of BPA, while damaged cans play a lesser role55. Also, in another study, Goodson et al. analyzed the migration of BPA from can coatings—impacts of damage, storage conditions and heating, and it was found that 80–100% of the total BPA existing in the coating had migrated directly to foodstuffs after can processing by pilot plant filling with food or simulant, sealing and sterilization. This concentration wasn’t changed by prolonged storing (up to nine months) or can damage, indicating most migration was occurring during the step of can processing. There was no noticeable difference, in this respect, among the different foodstuffs or the food simulant. Analysis of control samples (foods fortified with 0.1 mg/ kg BPA and contained in Schott bottles) exhibited BPA was steady under both storage and processing. Experiments were also conducted to investigate the potential impacts, on BPA migration from can coatings, of heating or cooking foodstuffs in the can before to consumption. Cans of food were purchased and then the cans of food were heated. BPA was analyzed before and after the heating/cooking process. It was concluded from the consequences that there were no appreciable differences in the BPA level before and after heating or cooking54. Furthermore in another study, Errico et al. analyzed the migration of bisphenol A into canned tomatoes produced in Italy (dependence on storage and temperature conditions) and reported all the samples revealed migration concentrations lower than 0.4 µg/kg, while samples subjected to heating process and/or can’s damage by denting, revealed an increase (significant) in the migration concentrations. Anyhow, no sample contained BPA exceeding the EU limit for migration, set at 600 µg/kg of food49.

Table 2.

Comparison of bisphenol A found in the current study with literature.

| Country | Sample | No. | Concentrations of BPA (µg/kg) | Method | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | |||||

| Iran | Canned fruit | 12 | 3.44 | 0.87–9.7 | GC/MS | Present study |

| Canned vegetable | 12 | 8.38 | 0.87–28.35 | |||

| Korea | Fruit | 12 | - | < 1.87–60.60 | LC–MS/MS | 3 |

| Vegetables | 11 | - | < 1.74–32 | |||

| Canada | Canned vegetable | 15 | 20 | 4.3–92 | GC–MS | 24 |

| Portugal | Canned fruits | 20 | 5.1 | < 0.3–10.2 | GC–MS | 6 |

| Canned vegetables | 19 | 67.5 | < 0.3–265.6 | |||

| China | Canned fruit | 20 | 60 | < LOD – 837 | UPLC–MS/MS | 25 |

| Canned vegetables | 10 | 18 | < LOD – 102 | |||

| Egypt | Vegetables and fruits | 60 | 51.53 | 5.57–233.78 | GC/MS/MS | 8 |

| Japan | Domestic canned fruit | 8 | 0 | < 5 | GC–MS | 30 |

| Imported canned fruit | 10 | 20 | < 5–200 | |||

| Domestic canned vegetable | 13 | 4.1 | < 5–11 | |||

| Imported canned vegetable | 18 | 35 | < 5–85 | |||

| Korea | Canned fruit | 9 | 8.6 | 3–54.56 | HPLC | 23 |

| Canned vegetable | 12 | 3.10 | 3–21.5 | |||

| France | Fruits | 74 | 0.47 | 0.105–2.13 | GC–MS/MS | 29 |

| Vegetables | 262 | 6.88 | 0.105–82.73 | |||

| Turkey | Olives | 4 | – | < 1–22 | UPLC–MS/MS | 22 |

| Canned vegetable oils | 4 | < 1 | < 1 | |||

In the recent decade, several studies have been conducted to remove bisphenol from the food matrix. Tapia-Orozco et al. reported an effective removal rate of 93.3% of BPA from canned liquid food with enzyme-based nanocomposites56. Also, the development of BPA-free cans can significantly reduce the amounts of BPA in canned food30. It has also been shown that biologically degrading BPA is also a promising method. Park and Chin reported that Bacillus subtilis P74 resulted in 97.2% degradation of 10 mg/L of BPA at 9 h57.

BPA can be released from the wall of cans into the food, in addition to this, BPA can also enter the food through the environment. When food cans are placed in high-temperature conditions, the release of BPA into the food can increase. The type of can, the pH of the food, the contact time of the food, the temperature of the environment, the amount of heating before consumption, are known to affect the release of BPA into the food58,59.

Health risk assessment

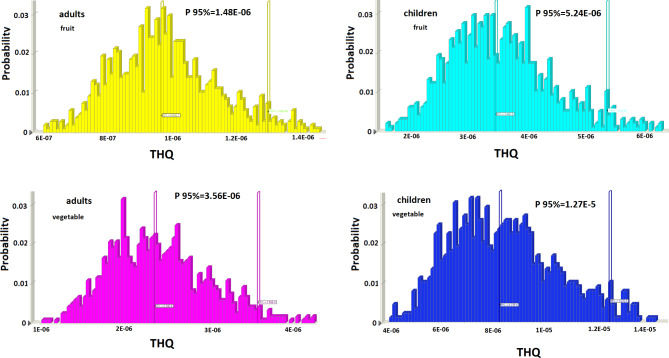

Table 3 presents the calculated estimated daily intake (EDI) of BPA exposure through consuming canned fruits and vegetables by Iranian children, and adults. Individuals can be exposed to BPA through diverse routes, with food recognized as the primary pathway of exposure. The 95th percentile EDI values of BPA in canned fruit for adults and children were 6.12E-08, and 2.16E-07 mg/kg bw/day, respectively. Also, the 95th percentile EDI values of BPA in canned vegetables for adults and children were 1.78E-07, and 6.26E-07 mg/kg bw/day, respectively (Table 3). EDI values for children, and adults were lower than the TDI value (0.002 µg/kg bw/day) of BPA set by the EFSA and at acceptable ranges45. Based on scenario (1), the 95th percentile THQ values in canned fruit for adults and children were 1.48E-06 and 5.24E-06; and in canned vegetables were 3.56E-06, and 1.27E-05, respectively (Fig. 2). THQ values for three age classes were less than 1 and acceptable. Based on scenario (2) for evalution the safety of BPA as used in food contact materials, the THQ values in canned fruit for adults and children were 9.82E-06 and 3.44E-05; and in canned vegetables were 2.396E-05, and 8.38E-05, respectively. Similar results are reported by previous research60,61. Based on the findings, the intake of BPA from canned fruits and vegetables in the population of Tehran, Iran is unlikely to cause human health complications. However, it is worth mentioning that since other dietary sources were not considered in the assessment, average daily intake may present an underestimate of actual exposure. Moreover, the potential synergistic impacts of BPA and other contaminants should not be ignored. Compared with other studies, Bemrah et al. reported that the range of 95th percentile EDI values of BPA in adults was 0.077–0.087 µg/kg bw/day and in children 0.119–0.141 µg/kg bw/day29. EDI and HI values in the study by Lim et al. were 1.509 mg/kg bw/d and HI = 0.0323. Cao et al. reported 95th percentile and 50th percentile of EDI in canned Vegetables were 67 and 9.1 ng/kg bw/day (range 4.3–92 ng/kg bw/day)24. In another study, EDI values of BPA in canned foods food for adults was 11 ng/kg bw/day30. Also, the mean EDI value reported by Choi et al., in yellow peaches was 2.45 ng/kg bw/day, and in mushrooms 0.09 ng/kg bw/day3.

Table 3.

EDI values (mg/kg bw/day) of bisphenol A exposure through canned fruit and vegetable consumption by children and adults.

| Risk | Type | Age | RfD | 5% | 50% | 75% | 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THQ | Canned fruit | Adults | 50 µg/kg/day | 6.35E-7 | 9.76E-7 | 1.15E-6 | 1.30E-6 |

| Canned fruit | Children | 2.18E-6 | 3.43E-6 | 4.04E-6 | 5.36E-6 | ||

| Canned vegetable | Adults | 1.54E-6 | 2.34E-6 | 2.76E-6 | 3.56E-6 | ||

| Canned vegetable | Children | 5.50E-6 | 8.37E-6 | 9.89E-6 | 1.27E-5 | ||

| EDI(mg/kg bw/day) | Canned fruit | Adults | 3.75E-08 | 4.85E-08 | 5.35E-08 | 6.12E-08 | |

| Canned fruit | Children | 1.36E-07 | 1.71E-07 | 1.88E-07 | 2.16E-07 | ||

| Canned vegetable | Adults | 7.81E-8 | 1.21E-7 | 1.42E-7 | 1.78E-7 | ||

| Canned vegetable | Children | 2.79E-7 | 4.12E-7 | 4.80E-7 | 6.26E-7 |

Fig. 2.

The simulation results for probability THQ in canned vegetables and fruit.

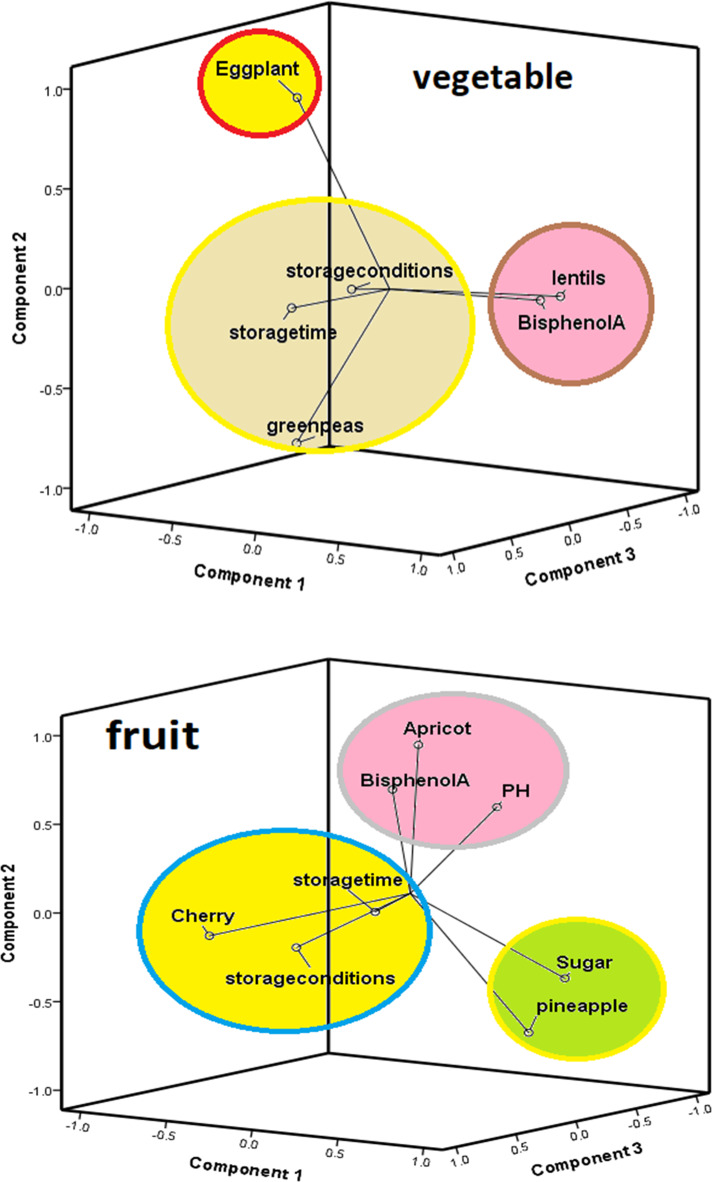

Analysis according to principle component analysis (PCA) outcomes

Principle Component Analysis (PCA) by intuitive visualization of data and results can be useful to present a very brief view of a specific purpose. The PCA analysis of BPA in canned fruit and vegetables is presented in Fig. 3. PCA was performed in order to clarify the general distribution patterns or similarities of BPA in canned food. As the Euclidean space is reduced, the samples show an upper correlation together. PCA extracted 96 samples including canned fruit (cherry, pineapple, and apricot) and canned vegetables (eggplant Stew, lentils, and green peas) for BPA. As can be observed, the samples were well divided into three main components that present the correlation between the amount of BPA in canned food.

Fig. 3.

Principal component analysis(PCA) of BPA concentrations in canned vegetables and fruit.

The PCA possessed of canned vegetables and fruit a satisfactory sum of proper values with component 1, component 2, and component 3 axes in canned fruit (37.1% for P1, 28.3% for P2, and 15.6% for P3) and in canned vegetables (40.3% for P1, 25% for P2 and 16.8% for P3). The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) results entail examining the variance accounted for by each principal component. Components that account for a high amount of variance contain substantial information, which is beneficial for dimensionality reduction. The parameter plot of canned fruit (Fig. 3) was primarily structured by the component 1 axis positively characterized by the sugar and canned pineapple, and negatively by the canned cherry. Also, the component 2 axis is positively characterized by the pH, BPA, and canned apricot, and negatively by the canned pineapple, the component 3 axis is positively characterized by the storage conditions. The parameter plot of canned vegetables (Fig. 3) was primarily structured by the component 1 axis positively characterized by the sugar and canned pineapple, and negatively by the canned cherry. Also, the component 2 axis is positively characterized by the pH, BPA, and canned apricot, and negatively by the canned pineapple, the component 3 axis is positively characterized by the storage conditions. An interesting perspective of the effect of the canned vegetable and fruit type, pH, sugar, storage time, and storage conditions on BPA is obtained by treating data using analysis of principal components (PCA). The results of PCA for BPA in canned fruits and vegetables were outstanding to evaluate intra- and inter-group similarities and differences. PCA analysis indicates that the contaminated BPA pattern in canned lentils, apricots, cherries, pineapples, eggplant stew, and green pea’s samples was easily distinguishable.

Conclusion

The main objective of the current study was to investigate BPA contents in canned fruit and vegetable samples distributed in Tehran, Iran. BPA was found in 100% of samples. The mean concentration of BPA in canned fruit samples (ranging from 0.87 to 9.7 µg/kg) was higher than that in canned vegetable samples (ranging from 0.87 to 28.35 µg/kg). The amount of BPA in all samples was within the maximum acceptable limit. PCA indicated a close and distinctive link between the classification of our samples based on their BPA levels in the canned fruit and vegetable samples. The results of the human health risks assessment of BPA exposure through canned fruit and vegetables indicate that EDI values were less than 4 µg/kg bw/day and HQ values were less than 1, which are acceptable. The major study limitation was the high cost of the tests, which restricted the sample collection from other provinces of Iran. According to the findings of risk evaluations, it has been concluded that consuming canned fruits and vegetables does not pose a significant health risk to consumers. Nevertheless, it is important to consider the potential effects of chronic exposure to bisphenol A from daily human diet.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Nabi Shariatifar: Design of study, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Methodology, Validation. Reza Hazrati -Raziabad and Majid Arabamerei: Writing- Original draft, Design of study, Methodology. Parisa Sadighara: Writing- Reviewing and Editing. Gholamreza Jahed khaniki and and Ramin Aslani: Data curation, Visualization, Investigation, Software, Validation, Methodology.

Funding

No financial funds were used in this article.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical review

This study does not involve any human or animal testing.

Consent for publication

All authors approve the final version for publication.

Consent to participate

All authors confirmed their Participation.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zheng, J., Tian, L. & Bayen, S. Chemical contaminants in canned food and can-packaged food: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.63, 2687–2718 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shariatifar, N. et al. Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk assessment of lead in traditional and industrial canned black olives from Iran. Nutrire47, 26 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi, S. J. et al. Concentrations of bisphenols in canned foods and their risk assessment in Korea. J. Food Prot.81, 903–916 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson*, B. & Grounds, P. Bisphenol A in canned foods in New Zealand: An exposure assessment. Food Addit. Contam.22, 65–72 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodson, A., Summerfield, W. & Cooper, I. Survey of bisphenol A and bisphenol F in canned foods. Food Addit. Contam.19, 796–802 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunha, S. & Fernandes, J. Assessment of bisphenol A and bisphenol B in canned vegetables and fruits by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry after QuEChERS and dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction. Food Control33, 549–555 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geens, T., Apelbaum, T. Z., Goeyens, L., Neels, H. & Covaci, A. Intake of bisphenol A from canned beverages and foods on the Belgian market. Food Addit. Contam.27, 1627–1637 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osman, M. A., Mahmoud, G. I., Elgammal, M. H. & Hasan, R. S. Studying of bisphenol A levels in some canned food, feed and baby bottles in Egyptian markets. Fresenius Environ. Bull.27, 9374–9381 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hao, P. P. Determination of bisphenol A in barreled drinking water by a SPE–LC–MS method. J. Environ. Sci. Health A55, 697–703 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vilarinho, F., Sendón, R., Van der Kellen, A., Vaz, M. & Silva, A. S. Bisphenol A in food as a result of its migration from food packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol.91, 33–65 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rochester, J. R. Bisphenol A and human health: A review of the literature. Reprod. Toxicol.42, 132–155 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baluka, S. A. & Rumbeiha, W. K. Bisphenol A and food safety: Lessons from developed to developing countries. Food Chem. Toxicol.92, 58–63 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao, K. et al. Development of an immunoaffinity column for the highly sensitive analysis of bisphenol A in 14 kinds of foodstuffs using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B. 1080, 50–58 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russo, G., Barbato, F., Mita, D. G. & Grumetto, L. Occurrence of Bisphenol A and its analogues in some foodstuff marketed in Europe. Food Chem. Toxicol.131, 110575 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vázquez-Loureiro, P. et al. Investigation of migrants from can coatings: Occurrence in canned foodstuffs and exposure assessment. Food Packag Shelf Life40, 101183 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen, D. et al. Bisphenol analogues other than BPA: Environmental occurrence, human exposure, and toxicity—A review. Environ. Sci. Tech.50, 5438–5453 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Commission directive 2004/19/EC of 1 march 2004 amending directive 2002/72/EC relating to plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with foodstuffs. Official J. Eur. Union71, 8–21 (2004).

- 18.vom Frederick, S. S. et al. The conflict between regulatory agencies over the 20,000-Fold lowering of the tolerable daily intake (TDI) for bisphenol A (BPA) by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Environ. Health Perspect.132, 045001. 10.1289/EHP13812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.EPA. (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency) Bisphenol A Action Plan. https://www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/bisphenol-bpa-summary (2010).

- 20.EFSA. Opinion of the scientific panel on food additives, flavourings, processing aids and materials in contact with food (AFC) on a request from the commission related to Butylbenzylphthalate (BBzP) for use in food contact materials. EFSA J.241, 1–14 (2005).

- 21.Zheng, X. et al. Hydrophobic graphene nanosheets decorated by monodispersed superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanocrystals as synergistic electromagnetic wave absorbers. J. Mater. Chem. C3, 4452–4463 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toptancı, İ. Risk assessment of bisphenol related compounds in canned convenience foods, olives, olive oil, and canned soft drinks in Turkey. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res.30, 54177–54192 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim, D. S., Kwack, S. J., Kim, K. B., Kim, H. S. & Lee, B. M. Risk assessment of bisphenol A migrated from canned foods in Korea. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A72, 1327–1335 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao, X. L., Corriveau, J. & Popovic, S. Bisphenol A in canned food products from Canadian markets. J. Food Prot.73, 1085–1089 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao, P. et al. Exposure to bisphenol A and its substitutes, bisphenol F and bisphenol S from canned foods and beverages on Chinese market. Food Control120, 107502 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noonan, G. O., Ackerman, L. K. & Begley, T. H. Concentration of bisphenol A in highly consumed canned foods on the US market. J. Agric. Food Chem.59, 7178–7185 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao, C. & Kannan, K. Concentrations and profiles of bisphenol A and other bisphenol analogues in foodstuffs from the United States and their implications for human exposure. J. Agric. Food Chem.61, 4655–4662 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan, M. K. & Clifton, M. S. Dietary exposures and intake doses to bisphenol A and triclosan in 188 duplicate-single solid food items consumed by US adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health18, 4387 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bemrah, N. et al. Assessment of dietary exposure to bisphenol A in the French population with a special focus on risk characterisation for pregnant French women. Food Chem. Toxicol.72, 90–97 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawamura, Y., Etoh, M., Hirakawa, Y., Abe, Y. & Mutsuga, M. Bisphenol A in domestic and imported canned foods in Japan. Food Addit. Contam. A31, 330–340 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao, C. & Kannan, K. A survey of bisphenol A and other bisphenol analogues in foodstuffs from nine cities in China. Food Addit. Contam. A31, 319–329 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Castro, M. L. & Priego-Capote, F. Soxhlet extraction: Past and present panacea. J. Chromatogr. A1217, 2383–2389 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patrignani, M., Conforti, P. A. & Lupano, C. E. Lipid oxidation in biscuits: Comparison of different lipid extraction methods. J. Food Meas. Charact.9, 104–109 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pirkhah, N. & Hosseini, S. A. Development of the best–worst method (BWM) as a novel technique for ranking fruit juice products. J. Food Sci. Technol.59, 4740–4747 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shahsavari, S. et al. Analysis of polychlorinated biphenyls in cream and ice cream using modified QuEChERS extraction and GC-QqQ‐MS/MS method: A risk assessment study. Int. J. Dairy. Technol.75, 448–459 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aslani, R. et al. Potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in bottled water (mineral and drinking) distributed in different seasons in Tehran, Iran: A health risk assessment study. Int. J. Environ. Res.18, 1–13 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kia, S. A., Aslani, R., Khaniki, G. J., Shariatifar, N. & Molaee-Aghaee, E. Determination and health risk assessment of heavy metals in chicken meat and edible giblets in Tehran, Iran. J. Trace Elem. Min.7, 100117 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalantari, N. National report of the comprehensive study on household food consumption patterns and nutritional status of IR Iran. Nutrition Research Group, National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute, Shaheed Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Health (2015).

- 39.Mohammadi, F. V., Qajarbeygi, P., Shariatifar, N., Mahmoudi, R. & Arabameri, M. Measurement of polychlorinated biphenyls in different high consumption canned foods, using the QuEChERS/GC-MS method. Food Chem: X20, 100957 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samimi, P. et al. Determination and risk assessment of aflatoxin B1 in the kernel of imported raw hazelnuts from Eastern Azerbaijan Province of Iran. Sci. Rep.14, 6864 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khanniri, E. et al. Determination of heavy metals in municipal water network of Tehran, Iran: A health risk assessment with a focus on carcinogenicity. Int. J. Cancer Manag. (2023).

- 42.Karimi, F. et al. Probabilistic health risk assessment and concentration of trace elements in meat, egg, and milk of Iran. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 1–12 (2021).

- 43.Shariatifar, N., Rezaei, M., Sani, M. A., Alimohammadi, M. & Arabameri, M. Assessment of Rice marketed in Iran with emphasis on toxic and essential elements; effect of different cooking methods. Biol. Trace Elem. Res.1–11 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Khalili, F. et al. The analysis and probabilistic health risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in cereal products. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1–11 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, E. et al. Re‐evaluation of the risks to public health related to the presence of bisphenol A (BPA) in foodstuffs. EFSA J.21, e06857 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Škrbić, B. D., Marinković, V. B. & Spaić, S. Assessing the impact of combustion and thermal decomposition properties of locally available biomass on the emissions of BTEX compounds by chemometric approach. Fuel282, 118824 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heydarieh, A. et al. Determination of magnesium, calcium and sulphate ion impurities in commercial edible salt. J. Chem. Health Risks10, 93–102 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ucheana, I. A., Ihedioha, J. N., Njoku, J. B. C., Abugu, H. O. & Ekere, N. R. Migration of bisphenol A from epoxy-can malt drink under various storage conditions and evaluation of its health risk. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 1–20 (2022).

- 49.Errico, S. et al. Migration of bisphenol A into canned tomatoes produced in Italy: Dependence on temperature and storage conditions. Food Chem.160, 157–164 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.FDA. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). Update on Bisphenol A (BPA) for use in food contact applications. Updated. November (2014). https://www.fda.gov/food/food-packaging-other-substances-come-contact-food-information-consumers/bisphenol-bpa-use-food-contact-application.

- 51.Bingol, M., Konar, N., Poyrazoğlu, E. S. & Artik, N. Influence of storage conditions on bisphenol A in polycarbonate carboys of water. Eur. Int. J. Sci. Technol.7, 107–123 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Munguia-Lopez, E., Gerardo-Lugo, S., Peralta, E., Bolumen, S. & Soto-Valdez, H. Migration of bisphenol A (BPA) from can coatings into a fatty-food simulant and tuna fish. Food Addit. Contam.22, 892–898 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sajiki, J. et al. Bisphenol A (BPA) and its source in foods in Japanese markets. Food Addit. Contam.24, 103–112 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goodson, A., Robin, H., Summerfield, W. & Cooper*, I. Migration of bisphenol A from can coatings—effects of damage, storage conditions and heating. Food Addit. Contam.21, 1015–1026 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stojanović, B. et al. Influence of a storage conditions on migration of bisphenol A from epoxy–phenolic coating to canned meat products. J. Serb. Chem. Soc.84, 377–389 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tapia-Orozco, N., Meléndez-Saavedra, F., Figueroa, M., Gimeno, M. & García-Arrazola, R. Removal of bisphenol A in canned liquid food by enzyme-based nanocomposites. Appl. Nanosci.8, 427–434 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park, Y. K. & Chin, Y. W. Degradation of Bisphenol A by Bacillus subtilis P74 isolated from traditional fermented soybean Foods. Microorganisms11, 2132 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khalili Sadrabad, E. et al. Bisphenol a release from food and beverage containers - A review. Food Sci. Nutr.11, 3718–3728 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Munguia-Lopez, E. M. & Soto-Valdez, H. Effect of heat processing and storage time on migration of bisphenol A (BPA) and bisphenol A – diglycidyl ether (BADGE) to aqueous food simulant from Mexican can coatings. J. Agric. Food Chem.49, 3666–3671 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akhbarizadeh, R., Moore, F., Monteiro, C., Fernandes, J. O. & Cunha, S. C. Occurrence, trophic transfer, and health risk assessment of bisphenol analogues in seafood from the Persian Gulf. Mar. Pollut. Bull.154, 111036 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diao, P. et al. Phenolic endocrine-disrupting compounds in the Pearl River Estuary: Occurrence, bioaccumulation and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ.584, 1100–1107 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.