Abstract

Zeaxanthin is a high-value carotenoid, found naturally in fruits and vegetables, flowers, and microorganisms. Flavobacterium genus is widely known for the production of zeaxanthin in its free form. Nowadays, the production of zeaxanthin from bacteria is still noncompetitive with traditional methods. The study of different operational conditions to enhance carotenoid production, along with the development of better models, is critical to improve the optimization, prediction, and control of the bioprocess. In this work, the influence of dissolved oxygen concentration was studied on zeaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, and β-carotene production. It was found that 10% pO2 was the best condition for zeaxanthin production in a batch bioprocess, reaching a total carotenoid concentration of 3280 ± 88 μg/L, with 86% of zeaxanthin. To enhance carotenoid production, a fed-batch culture was performed. Although biomass and total carotenoid productivity were similar between batch and fed-batch processes, the total carotenoid concentration in the fed-batch was the highest (8.3 mg/L) but with lower zeaxanthin content and productivity. Two kinetic models were proposed based on a modified Monod and Luedeking–Piret model, as well as glucose, biomass, oxygen, and each carotenoid concentration mass balance. The binary model that considers oxygen in biomass growth and product formation presented a better fit to the experimental data.

Introduction

Carotenoids are a diverse group of pigments that present interesting biological activities, such as antioxidant,1 anti-inflammatory, enhancing immune response, and anticancer properties,2,3 and some present provitamin A activities.4 They are the most widely distributed pigments in nature, being present in plants, algae, fungi, yeast, and bacteria.5 Zeaxanthin (3,3′-dihidroxi-β-carotene) is a xanthophyll that plays important physiological roles.6 In humans, the 3R-3R’ isomer is fundamental for the prevention of age macular degeneration (AMD). The epidemiological evidence showed that the amount of zeaxanthin and lutein in the macular tissues is inversely related to AMD.7 Other studies have established an inverse relation between zeaxanthin consumption and the risk of developing cancer.8,9 These properties have increased the interest in the use of zeaxanthin as a food supplement due to humans not being capable of synthesizing it de novo.10 Currently, zeaxanthin is widely used as a colorant in animal feed to enhance meat and egg yolk coloration.11

The market of natural zeaxanthin is supplied by the flowers of Marigold (Tagetes erecta). However, plant extraction has disadvantages regarding biotechnological production with microorganisms, such as lower yields (0.3 mg/g), seasonal and land dependency, and high-water consumption demand.12,13 The product obtained from this process is an oleoresin composed of zeaxanthin dipalmitate, zeaxanthin, and lutein.14 Natural zeaxanthin can also be obtained from photosynthetic microorganisms, such as microalgae and cyanobacteria,15 and from non-photosynthetic bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi.5 Regarding bacteria, species of genera Flavobacterium, Chryseobacterium, Paracoccus, and Erythrobacter were reported as zeaxanthin producers.16−19 However, the development of industrial zeaxanthin production bioprocesses by wild-type bacterial strains is still not competitive.20

The first step in carotenoid biosynthesis involves condensation of two geranyl–geranyl pyrophosphates (GGPPs) to produce phytoene.21 After desaturation, cyclization, and hydroxylation steps, and through the formation of a variety of intermediate compounds, zeaxanthin is produced.22 The carotenoid profile of Flavobacterium sp. P8 is simple since it synthesizes principally the zeaxanthin isomer with biological activity (3R-3R′) in free form and the biosynthesis intermediates β-cryptoxanthin and β-carotene.23 However, for the bacterial production of zeaxanthin to be economically viable, culture yields must be improved.

In the aerobic bioprocess, oxygen is a key substrate for cellular metabolism. Dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration in the culture media depends on the oxygen transport rate (OTR) from gas to liquid phases, OTR into the cell, and oxygen uptake rate (OUR) for growth, maintenance, and product synthesis. Gas–liquid transfer depends on hydrodynamic conditions in a bioreactor.24 During bioreactor culture, variations in OTR must be applied to equilibrate OUR, maintaining enough DO for cell growth and metabolite production. For Flavobacterium, oxygen is required not only for cell growth and maintenance but also for desaturation, cyclization, and oxygenation of carotenoids.25 The complexity of biological processes due to multiple simultaneous interactions among microorganisms, substrates, and transferred and consumed oxygen, among others, results in the development of kinetic models that explain these interactions being a challenge. Usually, first-principles models are developed to describe the biochemical and physical phenomena based on mass and energy balances and transport phenomena. In particular, kinetic models in which carotenoids are the product of interest have been proposed for astaxanthin by Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous(26,27) and β-carotene by a recombinant strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae.28 The development of accurate models is crucial for process optimization, prediction, and control. New approaches, such as hybrid models, where experimental data are combined with kinetic models, have been proposed recently.29−31 Bangi et al. proposed a hybrid modeling approach for the production of β-carotene at a laboratory scale by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. However, in those models proposed, oxygen was not a variable studied because no influence was reported, or the operational conditions applied in bioreactors avoided limitations.

This work aimed to study the influence of DO on biomass growth and β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, and zeaxanthin production by Flavobacterium sp. P8,17 a promising zeaxanthin natural producer. Different operating strategies to improve zeaxanthin production were investigated. Besides, a phenomenological model for batch fermentation was proposed to describe cell growth, glucose consumption, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, zeaxanthin production, and oxygen transfer and consumption. The model parameters were estimated by using experimental data obtained from batch cultures at different oxygen concentration regimes. In addition, fed-batch culture was also studied to improve zeaxanthin and total carotenoid production. The proposed models were tested with the fed-batch data.

Materials and Methods

Microorganisms and Inoculum Culture Conditions

Flavobacterium sp. P8 strain was isolated from saltwater samples collected at King George Island in Antarctica.23 Stock cultures were maintained in 20% glycerol and stored at −80 °C. Biomass used for bioreactor inoculation was grown in 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks with 150 mL of an optimized culture medium17 of composition, including glucose (6 g/L), peptone (7 g/L), yeast extract (7 g/L), NaCl (15 g/L), urea (0.5 g/L), MgSO4.7H20 (3.4 g/L), CaCl2 (0.3 g/L), Na2HPO4 ·7H2O (0.2 g/L), micronutrient solutions of 133 μL/100 mL (composition: H3BO3 (12.8 g/L), LiSO4 (1.0 g/L), MnSO4 (3.2 g/L), CoCl2 (2.0 g/L), CuSO4 ·H2O (4.0 g/L), NiSO4 (2.5 g/L), (NH4)6Mo7O24 ·4H2O (2.8 g/L), and ZnSO4 (4.8 g/L)), initial pH 7, for 24 h at 20 °C in an orbital shaker at 200 rpm.

Flavobacterium sp. P8 Batch and Fed-Batch Cultures

Batch cultures were conducted in a 5 L Biostat A Plus Bioreactor (Sartorius, Germany) with 3 L of working volume, operating at 20 °C and pH 7 with an aeration rate of 1 vvm. The composition of the medium is described previously. The initial biomass concentration was approximately 0.2 g/L in all runs. To study the influence of DO, the agitation rate (N) was adjusted automatically to achieve the minimum levels of 5, 10, 20, and 40% pO2 (where pO2 represents DO expressed as a percentage of the oxygen saturation concentration) in each culture, employing a cascade control mechanism using a minimal agitation rate of 300 rpm. A controlled trial was conducted at a constant agitation rate (N = 300 rpm). All of the runs were duplicated. The pH was automatically regulated at 7 by the controlled addition of 2.5 M NaOH or H2SO4.

Fed-batch culture was performed in the same bioreactor and operational conditions as those for batch cultures. The initial glucose concentration was 30 g/L. A substrate pulse of 50 mL with 400 g/L glucose, 140 g/L peptone, and 140 g/L yeast extract was added to extend the production phase when glucose reached 10 g/L. Yeast extract and peptone were included to incorporate macro- and micronutrients. The agitation rate was regulated automatically to ensure a minimum DO of 10% pO2. Biomass was harvested by centrifugation at 4100 rpm, 15 min, 4 °C, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was washed with distilled water and stored at −80 °C until lyophilization (VirTis BenchTop 2K Freeze-Dryer, SP Industries Inc.).

Carotenoid Extraction

The carotenoid extraction was carried out with 0.05 g of lyophilized biomass and 1 mL aliquots of methanol in a ball mill MM 400 (Retsch) at 30 Hz for 1 min. Supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 1 min, and extractions were repeated until biomass bleaching. Samples were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), as described below.

Analytical Determinations

Cell growth was determined by optical density at 600 nm by using a Genesys 10S UV–vis (Thermo Scientific) spectrophotometer. The relationship between the optical density and dry cell weight was determined, and the biomass concentration was reported as grams of dry cells per liter of culture medium (g/L). Glucose concentration was determined by an HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), equipped with a refraction index detector and an Aminex HPX-87H column (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., USA), operating at 45 °C. The mobile phase used was 5 mM H2SO4 at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. Concentrations were determined by quantification using commercial standards. Samples were previously filtered through 0.2 μm PTFE syringe filters. Carotenoid quantification was carried out by HPLC, as described by Delgado-Pelayo and Hornero-Méndez.10 Briefly, the separation of carotenoids was carried out by a binary gradient. The separation was done in a BDS Hypersil C18 (150 mm × 3 mm i.d., 3 μm, Thermo Fisher Scientific; USA) fitted with a guard column of the same material (10 mm × 3 mm). The initial composition was 75% acetone and 25% deionized water, which increased linearly in 10 min to 95% acetone and 5% deionized water and held for 7 min. Finally, the mixture was increased to 100% acetone in 3 min and was maintained constant for 10 min. Initial conditions were reached within 5 min. The temperature of the column was kept at 25 °C. An injection volume of 10 μL and a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min were used. Detection was performed at 450 nm, and the online spectra were acquired in the 330–700 nm wavelength range with a resolution of 1.2 nm.

Proposed Kinetic Model

A dynamic model based on mass balances of the batch fermentation was used. The variables were biomass (X, g/L), glucose (S, g/L), β-carotene (mg/L), β-cryptoxanthin (mg/L), zeaxanthin (mg/L), and DO (CO2, mg/L). For microbial growth, two kinetic models were proposed. The first was a simple Monod model32 considering glucose as the substrate. However, as Flavobacterium sp. growth is typically aerobic, a binary substrate-modified model was proposed considering both glucose and oxygen as substrates.33Eqs 1 and 2 show the variation of biomass in the batch fermentation for the kinetic models proposed. The specific growth rate μ (h–1) is a function of μmax,S (maximum growth rate for the simple model, h–1) and S, KS,S (glucose saturation constant for the simple model, g/L):

| 1 |

For the binary model, the specific growth rate depends on μmax,B (the maximum growth rate for the binary model, h–1), S, KS,B (glucose saturation constant for the binary model, g/L), CO2, and KO2 (oxygen saturation constant, mg/L):

| 2 |

Glucose consumption is described by eq 3, where Y*X/S is defined as a model parameter and refers to the total biomass produced based on the total glucose consumed in a complex medium (gbiomass/gglucose), as other carbon sources are available due to the presence of peptone and yeast extract. This parameter depends on the media culture formulation and tends to be YX/S when glucose is the main carbon source.

| 3 |

To describe β-carotene formation, a modified Luedeking–Piret equation34 was proposed. A first-order term with respect to oxygen concentration was added to consider the β-carotene consumption to form β-cryptoxanthin (eq 4)

| 4 |

where α (mgβ–carotene/gbiomass) is the growth-associated β-carotene formation coefficient, β (mgβ–carotene/gbiomassh) is the non-growth-associated β-carotene formation coefficient, and k1 (L/mgO2t) is the specific rate constant for β-carotene transformation in β-cryptoxanthin.

To describe β-cryptoxanthin production, a first-order model with respect to oxygen and β-carotene concentrations was proposed (eq 5), where k2 (L/mgO2t) is the specific rate constant for β-cryptoxanthin transformation in zeaxanthin.

| 5 |

Finally, to describe zeaxanthin formation, a first-order model with respect to oxygen and β-cryptoxanthin concentrations was proposed (eq 6).

| 6 |

For the binary model, the variation of the DO concentration was based on oxygen mass balances. The term corresponding to OUR (qO2X) was expressed, taking into account cell growth and maintenance. The equations are presented in eqs 7–9, where mO2 is the oxygen consumption coefficient for maintenance (h–1) and YX/O is the yield of oxygen uptake for biomass production (gbiomass/mgO2).

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

where kLa is the volumetric oxygen mass transfer coefficient (h–1), K1 and K2 are constants, and N is the agitation rate (rpm). The values of K1 and K2 were estimated in previous work (data not shown) as 0.18 h–1rpm–1 and −33 h–1, respectively. In both cases, it was assumed that there was no nitrogen limitation.

Parameter Estimation

The parameters μmax,S, KS,S, μmax,B, KS,B, α, β, KO2, mO2, YX/O, k1, and k2 were considered unknown. The Y*X/S value was calculated based on previously experimental data, resulting in 1.0 gbiomass/gglucose for batch cultures. CO2* was considered as oxygen solubility at 20 °C and the salinity of the media culture as 8.3 mg/L. Maximum likelihood was used for parameter estimation; this must solve a nonlinear optimization problem, where the objective function is the sum of the squared differences between the prediction by the model and data. As a restriction of the problem, the set of equation models and the limit values of each parameter were used (limits are presented in Table S1). As the output variables had a different range of values, the objective function used adimensional values of each output variable, where each output variable took a value between 0 and 1.

The estimation problem was implemented and solved in Octave, using lsode for the numerical integration of the model and sequential quadratic programming (sqp) to solve the optimization problem. The variables were biomass (X, g/L), glucose (S, g/L), β-carotene (mg/L), β-cryptoxanthin (mg/L), zeaxanthin (mg/L), and oxygen concentration (CO2, mg/L). Since carotenoids are quantified in milligrams per gram and the predictive model uses carotenoids in milligrams per liter, the production (mg/L) was determined by multiplying the total carotenoid value in milligrams per gram by the corresponding biomass concentration (g/L) at each measurement interval. For parameter estimation, the value of each experimental measurement, including replicates, was employed as individual data without calculating the average for each condition, using 103 measurements for each output variable.

Statistical Analysis

To determine the statistical significance of data differences, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed via InfoStat/Estudiantil version 2019 software (p ≤ 0.05).

The goodness of the estimations was evaluated by root-mean-square error (RMSE) and normalized root-mean-sqaure error (NRMSE).

Results and Discussion

Effect of DO on Biomass Growth and Carotenoid Production

Different minimum pO2 values were set to study their effect on biomass growth and carotenoid production. Figure 1a,b shows the biomass and glucose consumption profiles, respectively. Runs were extended up to 72 h to determine the relationship between growth and product formation. A control run at a constant agitation rate at 300 rpm was carried out. In this condition, throughout almost the entire essay, the pO2 remained close to 0 (DO and N profiles are shown in Figure S1). This oxygen limitation resulted in lower biomass and slower glucose consumption rate, with respect to those with the DO control set. Biomass concentration achieved similar results for other conditions.

Figure 1.

(a) Biomass and (b) glucose profiles obtained for batch cultures of Flavobacterium sp. P8 at 20 °C, 1 vvm, and 300 rpm.

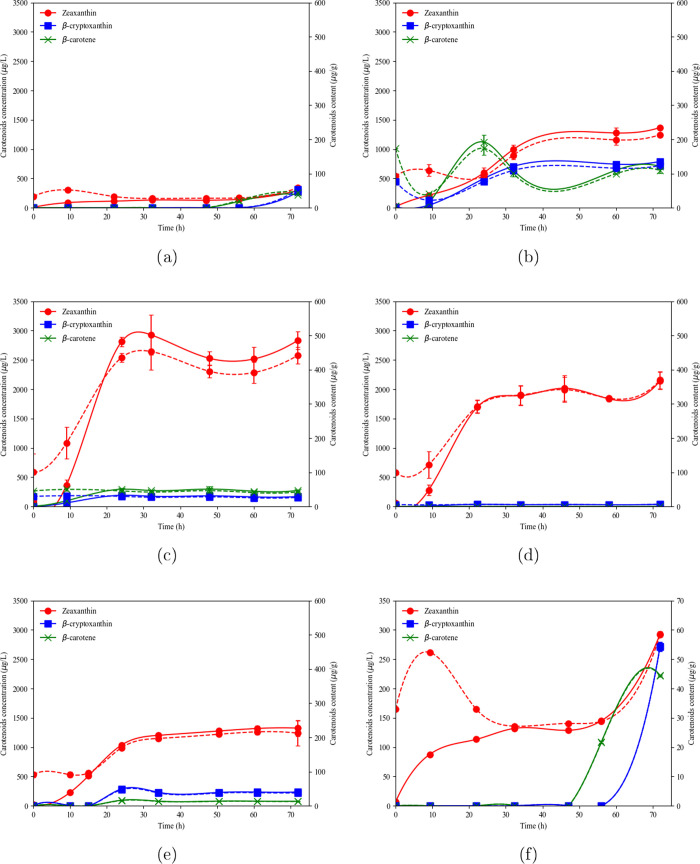

Regarding product formation, the carotenoid content and concentration profiles are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Zeaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, and β-carotene in dry biomass and zeaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin and β-carotene concentrations for batch cultures, at 20 °C, 1 vvm, and (a) constant agitation rate (N = 300 rpm), (b) 5% pO2, (c) 10% pO2, (d) 20% pO2, (e) 40% pO2, and (f) detailed constant agitation rate (N = 300 rpm) profile. Solid lines correspond to concentrations, and the dashed lines correspond to carotenoid contents, respectively.

Figure 2a,f shows the carotenoid profiles obtained at a constant agitation rate. An increase in carotenoid concentrations was observed in the early stages of bacterial culture. After 9 h of culture, the high oxygen demand due to the exponential cell growth caused oxygen limitation until 48 h. In this period, zeaxanthin concentration remained constant, and β-carotene and β-cryptoxanthin were not detected. Zeaxanthin content halved at 32 h, reaching approximately 25 μg/g. Once the stationary phase was reached and oxygen was raised, a significant increase in zeaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, and β-carotene was observed. The same trend was found for carotenoid contents. Therefore, oxygen transferred in this condition may not be enough to satisfy growth, maintenance, and carotenoid formation.

At 5% pO2, zeaxanthin and β-cryptoxanthin concentrations and contents increased during the experiment, reaching a maximum at 48 h of 1300 μg/L and 200 μg/g, and 735 μg/L and 120 μg/g, respectively, remaining constant until the end of the culture, as shown in Figure 2b. β-carotene content was the highest at 24 h and then dropped and stayed constant after 30 h. In the first 24 h, the culture had exponential growth, demanding a high oxygen concentration. However, the minimum DO setting was sufficient for biomass growth and β-carotene production. After 24 h, oxygen demand decreased due to the stationary growth phase achievement, and oxygen was available for hydroxylation of β-carotene to β-cryptoxanthin and zeaxanthin, reaching almost half of the total carotenoids (24% β-carotene, 28% β-cryptoxanthin, and 48% zeaxanthin). Zeaxanthin content presented a sharp increase until 24 h of culture at 10, 20, and 40% pO2, as shown in Figure 2c–e. The β-cryptoxanthin and β-carotene contents remained constant and low in all the conditions evaluated. Carotenoid concentration profiles were similar to carotenoid content profiles.

Table 1 summarizes the main results obtained. The highest total carotenoid content was achieved for 10% pO2, followed by 5% pO2. At 5% pO2, oxygen deficit for hydroxylation of β-carotene to β-cryptoxanthin, and the latest to zeaxanthin, could have caused the lower levels of this xanthophyll. The lowest zeaxanthin and total carotenoid contents (55 and 157 μg/g, respectively) were obtained for the experiment at a constant agitation rate (N = 300 rpm). This result confirmed that a minimal DO level is needed to produce carotenoids and the final conversion of β-carotene and β-cryptoxanthin to zeaxanthin. In zeaxanthin synthesis, the enzyme CrtZ is responsible for β-carotene and β-cryptoxanthin hydroxylation using molecular oxygen for hydroxylation.35 If molecular oxygen is not available enough, intermediate accumulation is observed, as happened at 5 and 10% pO2. On the other hand, 40% pO2 runs showed the lowest values of zeaxanthin and total carotenoids contents related to the other DO-controlled conditions (225 and 280 μg/g, respectively). High levels of DO in the broth could lead to oxidative stress due to the increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS). Carotenoid synthesis has been reported to increase in the presence of high levels of ROS as an adaptive strategy in bacteria, acting as scavengers of ROS and preventing oxidative damage to cell structures. However, the impact of increasing DO concentration on carotenoid metabolism cannot be easily predicted. In this study, Flavobacterium sp. P8 reached an optimal value for carotenoid production at low levels of DO, before subsequently decreasing. This result shows that oxygen availability could change metabolic routes in aerobic bioprocess, as it was demonstrated by other authors for different microorganisms and products.36 In this study, runs at high levels of DO (above 20% pO2) may induce metabolic changes associated with excessive peroxides and free radical production, causing undesirable products. Eventual secondary metabolite formation could decrease the yield of carotenoids. Although it is widely known that oxygen influences carotenogenesis in bacteria, there are few reports including quantitative results. These reports are mostly focused on optimization of agitation rates and air flow rates that favor pigment production instead of reaching the optimal value of DO for the bioprocess. Determining favorable conditions of DO in the culture is one of the most difficult tasks in the efficiency of an aerobic bioprocess. Masetto et al., reported that biomass growth was less sensitive to oxygen-dissolved concentration than carotenoid synthesis by Flavobacterium sp. (ATCC 21588). This is in accordance with the results obtained in this work. Biomass concentration and specific growth rate were considerably lower only at a constant agitation rate (300 rpm), and all conditions with DO concentration set presented similar results. However, significant differences were observed in carotenoid production under all conditions assayed, as well as in conversion percentage. Volumetric productivity of zeaxanthin and total carotenoids was maximum at 10% pO2. Thus, this condition was selected to study zeaxanthin and carotenoid production in fed-batch mode.

Table 1. Results Obtained for Culturing Flavobacterium sp. P8 in Batch Cultures at 20 °C, 1 vvm, and Different % pO2a.

| responses | 300 rpm | 5% | 10% | 20% | 40% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| biomass (g/L) | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | 6.2 ± 0.5 | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 6.0 ± 0.4 |

| glucose consumption (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| tf biomass (h) | 31 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| tf carotenoids (h) | 72 | 48 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| β-carotene (μg/L) | 222 ± 4 | 703 ± 36 | 275 ± 10 | nd | 91 ± 26 |

| β-cryptoxanthin (μg/L) | 284 ± 28 | 791 ± 10 | 171 ± 6 | 38 ± 6 | 239 ± 17 |

| zeaxanthin (μg/L) | 271 ± 47 | 1370 ± 10 | 2833 ± 108 | 2146 ± 130 | 1350 ± 137 |

| total carotenoids (μg/L) | 777 ± 7 | 2864 ± 46 | 3279 ± 124 | 2184 ± 135 | 1680 ± 180 |

| β-carotene (μg/g) | 44 ± 5 | 110 ± 6 | 43 ± 2 | nd | 15 ± 6 |

| β-crytpoxanthin (μg/g) | 57 ± 7 | 123 ± 2 | 27 ± 2 | 7 ± 1 | 40 ± 7 |

| zeaxanthin (μg/g) | 55 ± 8 | 214 ± 2 | 442 ± 17 | 370 ± 22 | 225 ± 44 |

| total carotenoids (μg/g) | 157 ± 47 | 447 ± 7 | 512 ± 20 | 377 ± 23 | 280 ± 56 |

| zeaxanthin/total carotenoids ratio (%) | 35 | 48 | 86 | 98 | 80 |

Each % pO2 condition was performed by duplicate. The results are presented as the mean of biological duplicates ± the difference between the highest and lowest values in a data set.

Parameter Estimation

Table 2 presents the values of the estimated parameters for the two models proposed.

Table 2. Values of the Estimated Parameters for the Single and Binary Substrate Modelsa.

| parameter | μmax,i (h–1) | KS,i (g/L) | KO2 (mg/L) | α (mg/g) | β (mg/gh–1) | mO2 (h–1) | k1 (L/mgO2t) | k2 (L/mgO2t) | YX/O (g/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| simple model | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.028 | 0.000042 | 0.089 | 0.050 | |||

| binary model | 0.27 | 0.30 | 2.32 | 0.16 | 0.0068 | 0.000086 | 0.090 | 0.050 | 1.34 |

For simple model i = S, for binary model i = B.

The μmax obtained in the binary model was slightly higher; however, the values for KS were very similar. The kinetic parameters obtained associated with β-carotene production (α and β) showed that its production is principally growth-associated, and they were comparable to those obtained previously by other authors.27,37 The kinetic constants for conversion of β-carotene to β-cryptoxanthin and its conversion to zeaxanthin (k1 and k2, respectively) were similar between the models.

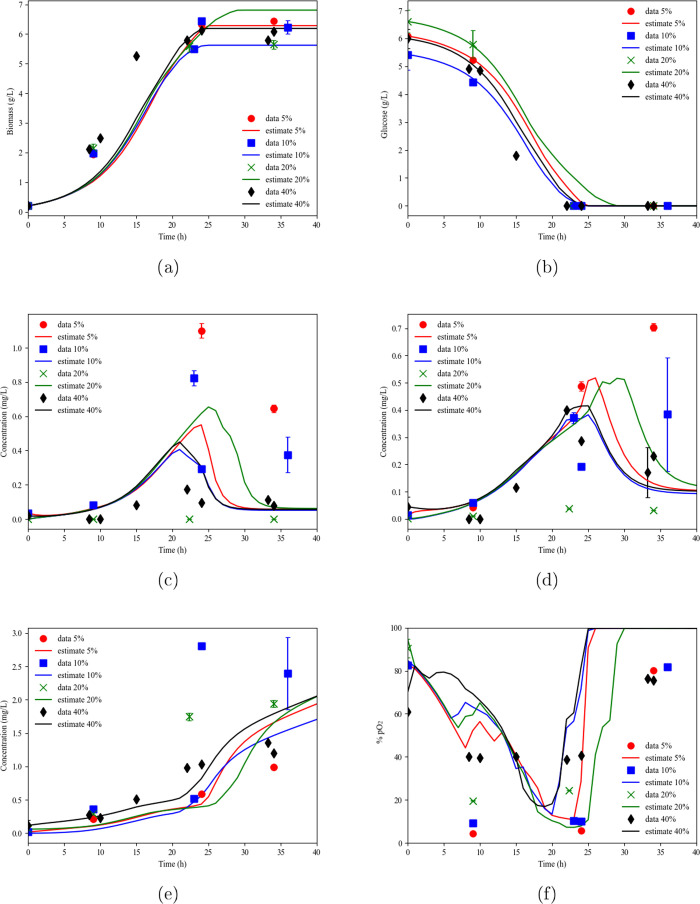

Table 3 presents the values of the RMSE and NRMSE of data points and estimates for each variable for the models tested. Better results were achieved for the binary model since RMSE and NRMSE, in most cases, were lower. Besides, Figure 3 presents the fitting of the binary substrate kinetic models, showing better adjustment of each carotenoid concentration. The simple model fitting is presented in Figure 2.

Table 3. Summary of the Model Parameters for Biomass, Glucose, β-Carotene, β-Crytpoxanthin, Zeaxanthin, and Dissolved Oxygen Concentration.

| simple model | binary model | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | S | β-carotene | β-cryptoxanthin | zeaxanthin | X | S | β-carotene | β-cryptoxanthin | zeaxanthin | CO2 | |

| RMSE | 1.20 | 0.70 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.92 | 0.53 | 0.20 | 0.094 | 0.63 | 2.76 |

| NRMSE | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.028 | 0.47 | 0.15 | 0.075 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.35 |

Figure 3.

(a) Biomass, (b) glucose, (c) β-carotene, (d) β-crytpoxanthin, (e) zeaxanthin, and (f) % pO2 data and estimation as a function of time for the experiments at different DO, considering the binary substrate model.

The binary substrate model proved to be satisfactory for predicting the parameters associated with cellular growth, substrate consumption, and product formation in batch mode. In the upcoming sections, the goodness of fit of the model for predicting growth behavior, substrate consumption, and product formation in fed-batch mode was evaluated.

Fed-Batch Flavobacterium sp. P8 Culture

A fed-batch culture of Flavobacterium sp. P8 was performed with the aim to increase carotenoid production. The response profiles are shown in Figure 4. Previously, the batch experiments were conducted with a glucose concentration of 6 g/L, as the microorganism did not consume more than this amount during optimization experiments in shaken flasks, as reported elsewhere.17 In bioreactor batch cultures, glucose was completely consumed within the first 20 h, reaching the stationary growth phase. The highest glucose concentration that did not inhibit cell growth was determined previously as 30 g/L (data not shown); therefore, this was the initial sugar concentration selected for the fed-batch.

Figure 4.

(a) % pO2 profiles and stirring speed (N) vs time and (b) biomass, glucose, and carotenoid concentration profiles as a function of time for the culture of Flavobacterium sp. P8 in fed-batch mode at 20 °C and 10% pO2.

Flavobacterium sp. P8 was able to consume 60 g/L glucose and reached a biomass concentration of 15.5 ± 0.1 g/L at the end of the culture. The substrate pulse was added at 30 h of fermentation. After 60 h, biomass and carotenoid concentration remained constant, although glucose was not totally consumed until 72 h. Carotenoid production was growth-associated. The maximum total carotenoid concentration was 8.4 ± 0.2 mg/L at 60 h, and the composition of carotenoids in the extract was 25% zeaxanthin, 22% β-cryptoxanthin, and 54% β-carotene. The increase in the zeaxanthin concentration was attributed to biomass growth, as the zeaxanthin content remained constant (120 μg/g) throughout the experiment. However, β-cryptoxanthin and β-carotene were accumulated. The β-cryptoxanthin content increased from 21 ± 8 to 115 ± 1 μg/g and β-carotene from 18 ± 4 to 289 ± 6 μg/g.

Table 4 shows the results obtained in batch and fed-batch modes by Flavobacterium sp. P8. for 10% pO2. For the fed-batch culture, the results before and after the pulse of the substrates are presented. In the fed-batch culture, the biomass concentration increased 2.5 times compared to that obtained in batch culture. However, biomass growth was extended until 60 h in fed-batch culture, resulting in similar biomass productivity. In both operation modes, glucose was totally consumed. Total carotenoid contents did not present significant differences. These results could be caused by an exhaustion of nutrients that are needed for carotenoid synthesis. On the other hand, since carotenoids are immersed in the cell membrane, their accumulation capacity could be limited.12

Table 4. Results Obtained for Flavobacterium sp. P8 Cultures at 20 °C, 1 vvm, and 10% pO2 in Batch and Fed-Batch Cultures (before and after the Pulse).

| parameter | batch | fed-batch (0–30 h) | fed-batch (30–81 h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| biomass (g/L) | 6.2 ± 0.5 | 8.5 ± 0.1 | 15.5 ± 0.1 |

| initial glucose (g/L) | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 27.7 ± 0.1 | 33.0 ± 0.5 |

| tf biomass (h) | 24 | 60 | |

| tf carotenoids (h) | 24 | 60 | |

| β-carotene (μg/L) | 275 ± 10 | 1125 ± 48 | 4511 ± 193 |

| β-cryptoxanthin (μg/L) | 171 ± 6 | 679 ± 24 | 1685 ± 63 |

| zeaxanthin (μ/L) | 2833 ± 108 | 937 ± 40 | 2149 ± 99 |

| total carotenoids (μ/g/L) | 3279 ± 124 | 2740 ± 89 | 8346 ± 200 |

| β-carotene (μg/g) | 43 ± 2 | 132 ± 4 | 289 ± 6 |

| β-crytpoxanthin (μg/g) | 27 ± 2 | 80 ± 2 | 115 ± 1 |

| zeaxanthin (μg/g) | 442 ± 17 | 110 ± 5 | 131 ± 3 |

| total carotenoids (μg/g) | 512 ± 20 | 322 ± 10 | 536 ± 6 |

| zeaxanthin/total carotenoids ratio (%) | 86 | 34 | 26 |

| zeaxanthin productivity (μg/Lh) | 118 | 31 | 36 |

| total carotenoid productivity (μg/Lh) | 137 | 91 | 139 |

Prediction of Fed-Batch Production

The kinetic parameters estimated by the binary substrate model in batch fermentation were tested in fed-batch mode. The validation was performed using the parameters listed in Table 1 and the Y*X/S value based on experimental data, resulting in 0.5 g/g up to 30 h and 0.2 g/g for the rest of the culture. The obtained values of RMSE and NRMSE are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Summary of the Model Parameters for Biomass, Glucose, β-Carotene, β-Cryptoxanthin, Zeaxanthin, and Dissolved Oxygen Concentration in Fed-Batch Production Validation of the Binary Substrate Model.

| X | S | β-carotene | β-cryptoxanthin | zeaxanthin | CO2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 2.29 | 6.49 | 2.78 | 0.79 | 4.135 | 4.732 |

| NRMSE | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 2.06 | 0.63 |

Figure 5 presents fed-batch data and predictions for the binary model. The model obtained for batch cultures fits properly for biomass, glucose, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, and zeaxanthin production in the first stage of the fed-batch culture.

Figure 5.

Fitting of the experimental data to the binary substrate model for describing the fed-batch culture of Flavobacterium sp. P8 at 20 °C, 1 vvm, and 10% pO2.

After the addition of the substrate pulse (30 h), biomass estimation remained stable, in accordance with experimental values, β-carotene and β-crypoxanthin remained at low values, and zeaxanthin was overestimated. On the other hand, DO estimation did not fit the experimental data. This difference could be due to a different metabolic cellular state. The glucose feeding did not result in increasing biomass; however, it was fastly consumed for biomass maintenance or conversion into byproducts, with continuous oxygen consumption. The high concentration of glucose could induce a metabolic overflow that was not present in the batch culture, resulting in the lack of adjustment in the final stage.

In this work, the effect of different concentrations of DO on cultivation of Flavobacterium sp. P8 was studied in the bioreactor. It was determined that 10% pO2 favored the zeaxanthin and total carotenoid production in batch mode. The cultivation of Flavobacterium sp. P8 in fed-batch mode enabled an increase in total carotenoid concentration to 8346 ± 200 μg/L. However, this increase was caused by the accumulation of β-cryptoxanthin and β-carotene content in biomass and higher biomass concentration compared to batch cultivation.

A binary substrate model that considers oxygen consumption for growth and carotenoids was built with batch experimental data. The kinetic parameters were extended to fed-batch production to test the models' goodness. The binary model fitted better at the early stages of the culture, suggesting that oxygen and metabolic regimes should be considered to improve model accuracy. Further experiments must be carried out to improve the model fitting for fed-batch production.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Comisión Académica de Posgrado (CAP) for the postgraduate scholarship given to Eugenia Vila and the Instituto Antártico Uruguayo and Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica (CSIC) for their financial support (CSIC I + D 2014 219, CSIC INI 230).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.4c06892.

Guess values and limits of estimated parameters (Table S1); agitation rate and % pO2, profiles for the conditions studied: (a) constant agitation rate (N = 300 rpm), (b) 5% pO2, (c) 10% pO2, (d) 20% pO2, and (e) 40% pO2 (Figure S1); and (a) biomass, (b) glucose, (c) β-carotene, (d) β-cryptoxanthin, and (e) zeaxanthin, data and estimation as a function of time for the experiments at different DO, considering the single substrate model (Figure S2) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kabir M. T.; et al. Therapeutic promise of carotenoids as antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents in neurodegenerative disorders. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 146, 112610 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argirion I.; Arthur A. E.; Zarins K. R.; Bellile E.; Amlani L.; Taylor J. M.; Wolf G. T.; McHugh J.; Nguyen A.; Mondul A. M.; Rozek L. S. The University of Michigan Head and Neck SPORE Program, Pretreatment diet, serum carotenoids and tocopherols influence tumor immune response in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 4644–4644. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2020-4644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ávila Román J.; García-Gil S.; Rodríguez-Luna A.; Motilva V.; Talero E. Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Effects of Microalgal Carotenoids. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 531. 10.3390/md19100531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino A.; Maoka T.; Yasui H. Preventive Effects of β-Cryptoxanthin, a Potent Antioxidant and Provitamin A Carotenoid, on Lifestyle-Related Diseases—A Central Focus on Its Effects on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD).. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 43. 10.3390/antiox11010043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Liu Z.; Sun J.; Xue C.; Mao X. Biotechnological production of zeaxanthin by microorganisms. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2018, 71, 225–234. 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Britton G. Structure and properties of carotenoids in relation to function. FASEB J. 1995, 9, 1551–1558. 10.1096/fasebj.9.15.8529834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller S. M. Associations Between Intermediate Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Lutein and Zeaxanthin in the Carotenoids in Age-Related Eye Disease Study (CAREDS): Ancillary Study of the Women’s Health Initiative. Archives of Ophthalmology 2006, 124, 1151. 10.1001/archopht.124.8.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. H.; Kristal A. R.; Stanford J. L. Fruit and Vegetable Intakes and Prostate Cancer Risk. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2000, 92, 61–68. 10.1093/jnci/92.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino H.; Murakoshi M.; Tokuda H.; Satomi Y. Cancer prevention by carotenoids. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2009, 483, 165–168. 10.1016/j.abb.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Pelayo R.; Hornero-Méndez D. Identification and Quantitative Analysis of Carotenoids and Their Esters from Sarsaparilla (Smilax aspera L.) Berries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 8225–8232. 10.1021/jf302719g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H.; Kim J.; Kim J.; Lee D.; Lee S.; Kil D. Effect of feeding duration of diets containing corn distillers dried grains with solubles on productive performance, egg quality, and lutein and zeaxanthin concentrations of egg yolk in laying hens. Poultry Science 2016, 95, 2366–2371. 10.3382/ps/pew127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram S.; Mitra M.; Shah F.; Tirkey S. R.; Mishra S. Bacteria as an alternate biofactory for carotenoid production: A review of its applications, opportunities and challenges. Journal of Functional Foods 2020, 67, 103867 10.1016/j.jff.2020.103867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z.; Wang X.; Gao S.; Li D.; Zhou J. Production of Natural Pigments Using Microorganisms. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 9243–9254. 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c02222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete-Bolaños J. L.; Rangel-Cruz C. L.; Jiménez-Islas H.; Botello-Alvarez E.; Rico-Martínez R. Pre-treatment effects on the extraction efficiency of xanthophylls from marigold flower (Tagetes erecta) using hexane. Food Research International 2005, 38, 159–165. 10.1016/j.foodres.2004.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdon L.; Jensen A. A.; Kavanagh J. M.; McClure D. D. Microalgal production of zeaxanthin. Algal Research 2021, 55, 102266 10.1016/j.algal.2021.102266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi C.; Singhal R. S. Modelling and optimization of zeaxanthin production by Paracoccus zeaxanthinifaciens ATCC 21588 using hybrid genetic algorithm techniques. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2016, 8, 228–235. 10.1016/j.bcab.2016.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vila E.; Hornero-Méndez D.; Lareo C.; Saravia V. Biotechnological production of zeaxanthin by an Antarctic Flavobacterium: Evaluation of culture conditions. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 319, 54–60. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2020.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradel P.; Calisto N.; Navarro L.; Barriga A.; Vera N.; Aranda C.; Simpfendorfer R.; Valdés N.; Corsini G.; Tello M.; González A. R. Carotenoid Cocktail Produced by An Antarctic Soil Flavobacterium with Biotechnological Potential. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2419. 10.3390/microorganisms9122419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niero H.; Da Silva M. A. C.; De Felicio R.; Trivella D. B. B.; Lima A. O. D. S. Carotenoids produced by the deep-sea bacterium Erythrobacter citreus LAMA 915: detection and proposal of their biosynthetic pathway. Folia Microbiologica 2021, 66, 441–456. 10.1007/s12223-021-00858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.; Sandmann G.; Chen F.; Huang J. Enhanced coproduction of cell-bound zeaxanthin and secreted exopolysaccharides by Sphingobium sp. via metabolic engineering and optimized fermentation. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2019, 67, 12228–12236. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b05342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasamontes L.; Hug D.; Tessier M.; Hohmann H.-P.; Schierle J.; Van Loon A. P. Isolation and characterization of the carotenoid biosynthesis genes of Flavobacterium sp. strain R1534. Gene 1997, 185, 35–41. 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00624-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton G.; Lockley W. J. S.; Patel N. J.; Goodwin T. W.; Englert G. Use of deuterium labelling to elucidate the stereochemistry of the initial step of the cyclization reaction in zeaxanthin biosynthesis in a Flavobacterium. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1977, 655. 10.1039/c39770000655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vila E.; Hornero-Méndez D.; Azziz G.; Lareo C.; Saravia V. Carotenoids from heterotrophic bacteria isolated from Fildes Peninsula, King George Island, Antarctica. Biotechnology Reports 2019, 21, e00306 10.1016/j.btre.2019.e00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ochoa F.; Gomez E. Bioreactor scale-up and oxygen transfer rate in microbial processes: An overview. Biotechnology Advances 2009, 27, 153–176. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masetto A.; Flores-Cotera L. B.; Díaz C.; Langley E.; Sanchez S. Application of a complete factorial design for the production of zeaxanthin by Flavobacterium sp. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2001, 92, 55–58. 10.1016/S1389-1723(01)80199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.-S.; Wu J.-Y. Modeling of Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous growth on glucose and overflow metabolism in batch and fed-batch cultures for astaxanthin production. Biotechnology and bioengineering 2008, 101, 996–1004. 10.1002/bit.21978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Flores C.; Ramírez-Cordova J.; Pelayo-Ortiz C.; Femat R.; Herrera-López E. Batch and fed-batch modeling of carotenoids production by Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous using Yucca fillifera date juice as substrate. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2010, 53, 131–136. 10.1016/j.bej.2010.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ordoñez M. C.; Raftery J. P.; Jaladi T.; Chen X.; Kao K.; Karim M. N. Modelling of batch kinetics of aerobic carotenoid production using Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2016, 114, 226–236. 10.1016/j.bej.2016.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bangi M. S. F.; Kao K.; Kwon J. S.-I. Physics-informed neural networks for hybrid modeling of lab-scale batch fermentation for β-carotene production using Saccharomyces cerevisiae.. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 179, 415–423. 10.1016/j.cherd.2022.01.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shah P.; Sheriff M. Z.; Bangi M. S. F.; Kravaris C.; Kwon J. S.-I.; Botre C.; Hirota J. Deep neural network-based hybrid modeling and experimental validation for an industry-scale fermentation process: Identification of time-varying dependencies among parameters. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 441, 135643 10.1016/j.cej.2022.135643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shah P.; Sheriff M. Z.; Bangi M. S. F.; Kravaris C.; Kwon J. S.-I.; Botre C.; Hirota J. Multi-rate observer design and optimal control to maximize productivity of an industry-scale fermentation process. AIChE J. 2023, 69, e17946 10.1002/aic.17946. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monod J. THE GROWTH OF BACTERIAL CULTURES. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1949, 3, 371–394. 10.1146/annurev.mi.03.100149.002103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bader F. G. Analysis of double-substrate limited growth. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1978, 20, 183–202. 10.1002/bit.260200203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luedeking R.; Piret E. L. A kinetic study of the lactic acid fermentation. Batch process at controlled pH. Journal of Biochemical and Microbiological Technology and Engineering 1959, 1, 393–412. 10.1002/jbmte.390010406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín J. F.; Gudiña E.; Barredo J. L. Conversion of β-carotene into astaxanthin: Two separate enzymes or a bifunctional hydroxylase-ketolase protein?. Microb. Cell Factor. 2008, 7, 3. 10.1186/1475-2859-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ochoa F.; Gomez E.; Santos V. E. Fluid dynamic conditions and oxygen availability effects on microbial cultures in STBR: An overview. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2020, 164, 107803 10.1016/j.bej.2020.107803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra R.; Chaudhuri S.; Dutta D. Modelling the growth kinetics of Kocuria marina DAGII as a function of single and binary substrate during batch production of β-Cryptoxanthin.. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 40, 99–113. 10.1007/s00449-016-1678-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.