Abstract

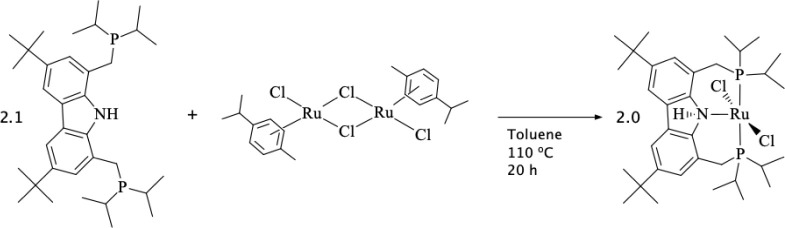

The five-coordinate complex [RuCl2(PNP)] (1) was synthesized from the binuclear [RuCl2(p-cym)]2 with a PNP-type ligand (PNP = 3,6-di-tert-butyl-1,8-bis(diisopropylphosphino)methyl)-9H-carbazole – (CbzdiphosiPr)H) in a toluene solution, within 20 h at 110 °C, producing a green solid, which was precipitated with a 1/1 mixture of n- pentane/HMDSO. The complex was characterized by NMR—1H, 13C, and 31P{1H}, mass spectroscopy—LIFDI, FTIR, UV/vis spectroscopy, and cyclic voltammetry, as well as a description of the optimized structure by DFT calculation. The reactivity of 1 was investigated in the presence of potassium triethylborohydride (KBEt3H, in THF solution of 1.0 mol L–1) and ammonium formate (NH4HCO2), producing an in situ hydride complex and a formate intermediate species coordinated to the ruthenium center. The complex 1, loaded with 0.08%, catalyzed the decomposition of ammonium formate (AF) into H2, CO2, and NH3 in THF solutions at 80 °C, with 94% of H2 and TOF = 206 h–1 (molar ratio [Ru]/AF = 1/1204). The catalytic activity increased remarkably for the decomposition of formic acid (FA) as a substrate to produce H2 and CO2. In the HMDSO solution at 80 °C, a conversion of 100% was obtained in relation to H2 and TOF = 3010 h–1 (molar ration [Ru]/FA/NEt3 = 1/1204/843). In an equimolar mixture of AF/FA in HMDSO solution at 80 °C, without additives, the complex 1 catalyzed the decomposition of both with 100% of H2 and TOF = 987 h–1 (molar ratio [Ru]/AF/FA= 1/602/602). Under the later conditions, as well as upon AF decomposition, carbamic acid [HO(C=O)NH2] was obtained as a coproduct of a secondary reaction between NH3 and CO2 (yield = 50% in relation to the amount of AF). A kinetic study for decomposing FA, in the range of 60–100 °C, provided ΔS‡ = −9.7 e.u, ΔG‡ = 13.35 kJ mol–1, and Ea = 64 kJ mol–1, suggesting that the mechanism is more associative than for the known complexes.

Introduction

The process of decomposition of formic acid (FA) with a heterogeneous catalyst has been known for over 100 years,1 but only in the 1960s, scientists investigated this reaction using homogeneous catalysts, which are more selective and prevent the formation of carbon monoxide (CO). In this context, FA can be decomposed following two pathways: a) a more spontaneous reaction producing CO2 + H2 (ΔG° = −38.3 kJ mol–1) and b) a less spontaneous reaction producing CO + H2O (ΔG° = −9.66 kJ mol–1).2

The second reaction is highly undesired, when a coordination compound is involved in the system as catalyst or precatalyst, since small amounts of CO can deactivate the catalytic species.2 Only in 2008, Beller3 and Laurenczy4 described independently the use of ruthenium complexes as catalysts for the dehydrogenation of FA without CO release. Two years later, Dupont and coworkers5 showed the use of [{RuCl2(p-cymene)}2] dissolved in the ionic liquid, without additional bases, to promote the decomposition of FA without CO with remarkable catalytic activity observed during recycles. Since then, many metal-based catalysts have been tested for this purpose: Fe,6,7 Co,8 Ru,9−11 Ir,12 Pd,13 Mo,14 Rh,15 and Ni.16

The decomposition products of FA (H2 + CO2) can be used directly in chemical processes or captured and recycled to regenerate it.17,18 The molecular hydrogen (H2) produced can also be exploited in a fuel cell,2 which is considered one of the most important sources of energy, besides being free of pollutant emissions. Alternatively, the catalytic decomposition of FA to generate syngas (a mixture of H2 and CO) is also a valuable strategy for energy conversion, since it can be used directly in internal combustion engines or converted to liquid fuels.19

Considering the catalytic decomposition of FA with ruthenium-based catalysts, a variety of ligand cases have been used successfully.20−23 These include sulfonated phosphins,24 α-diimines,9N-donor chelating ligands,25N-heterocyclic carbenes,16 and [PNP]-pincer ligands.11 Related to the last example, by combining a N-heterocycle with two phosphine donors, two classes of N-heterocyclic PNP ligands are known: (i) an uncharged protonated or tertiary PNP ligand and (ii) an anionic PNP pincer via deprotonation of the neutral ligand.26,27 The effect of PNP donor ligands coordinated to ruthenium with a NH and N-methylated moiety on the catalytic dehydrogenation of formic acid is documented in the currently literature.11 In all cases, the catalyst containing the N-Me portion was superior to the complex containing N–H.

Another interesting and efficient source of molecular hydrogen is ammonium formate (AF), since formates store H2 in chemical bonds using the concept of H2 carriers.28 Alkali metal formates can decompose to H2, carbonates (M2CO3), and bicarbonates (MHCO3) in the presence of water or methanol as solvent,29 and in the absence of water and an appropriate catalyst, they can produce H2, CO2, and NH3.30

Some examples of catalytic systems for the decomposition of AF are described in the literature using heterogeneous catalysts: Pd/C,28−31 Au3Pd1,32 Pd nanoparticles (Pd/CS-GO),33 and Au/TiO2.34 The results are relevant in the context of efficient generation of H2 from hydrogen-carrying organic molecules.

To the best of our knowledge, in the last 24 years, only one example using a homogeneous Pd catalyst has been reported for this purpose.29 Many homogeneous catalysts could be adapted to investigate the dehydrogenation of ammonium formate. For example, Mellmann35 and Xu36 discuss homogeneous catalysts for the dehydrogenation of formic acid and discuss conditions and catalysts that could be applicable also to derivative salts such as ammonium formate. Here, we present a system that employs a homogeneous catalyst for this reaction, which, to our knowledge, is the first example that uses a ruthenium coordination complex.

This work describes the synthesis and characterization of the complex [RuCl2(PNP)](1), the chemical reactivity toward KBEt3H and NH4HCO2, and the application of 1 as a catalyst for the homogeneous decomposition of a mixture of FA, AF, and FA/AF.

Experimental Section

All manipulations were carried out under an inert atmosphere of dry argon (Argon 5.0, purchased from Messer Group GmbH and dried over Granusic granulated phosphorus pentoxide) using standard Schlenk techniques or by working in a glovebox. Solvents were dried according to literature procedures.37 The ligands (CbzdiphosiPr)H38 and [RuCl(H)(PPh3)3]39,40 were synthesized according to the literature. All other chemicals were purchased and used as received without further purification. NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Avance III (600 MHz) and Bruker Avance II (400 MHz) instruments. Chemical shifts (δ) are given in parts per million (ppm) and are referenced to residual proton or the carbon resonance solvent signals.41 H3PO4 (31P) was used as an external standard for the 31P{1H} NMR data. The following abbreviations were used: s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), m (multiplet), sept (septet), and br (broad signal). Mass spectra were acquired on a JEOL JMS-700 magnetic sector (LIFDI) spectrometer at the mass spectrometry facility of the Institute of Organic Chemistry, the University of Heidelberg. UV/vis spectroscopy was performed on a Varian instrument, model Cary 5000, in the range of 1500–220 nm, using a quartz cell with 1 cm of optical length, which was prepared for measurements under an argon atmosphere. FTIR-ATR spectroscopy was recorded in an Agilent Cary 630 instrument in the range of 400–4000 cm–1 by using solid-state samples. TGA was performed in a Mettler Toledo TGA2 instrument under a constant flow of a N2 atmosphere (50 mL/min), using a heating rate of 10 K/min from 30 to 600 °C. Cyclic voltammetry was carried out in a Potentiostat PAL Sens instrument, model EMStat3+Blue, with Bluetooth connection, inside the glovebox. The electrochemistry cell was built with a vase, containing a THF solution of [RuCl2(PNP)] (5 mmol L–1), HTBA as a support electrolyte (n-Bu4NPF6, 0.1 mol L–1), and three electrodes: a glassy carbon disc (WE), a Pt wire (CE), and a Ag wire (RE). The ground-state structure of [RuCl2(PNP)] was optimized by the density functional theory (DFT), using five different functionals, i.e., B3LYP, B3PW91, CAM-B3LYP, LC-wPBE, and PBE0. The basis sets used to build the molecular orbitals were LANL2DZ (Los Alamos National Laboratory 2 double-ζ) for ruthenium, 6-31G for carbon and hydrogen, and 6-31G(d,p) for the remaining atoms. The Hessian matrix was calculated for the optimized structures to verify the nature of the stationary state. All calculations were carried out using Gaussian09.42

Synthesis of [RuCl2(PNP)] (1)

Inside a glovebox, binuclear [RuCl2(p-cym)]2 (150 mg; 0.245 mmol) was added in a Schlenk tube with toluene (5 mL). The PNP-type ligand 3,6-di-tert-butyl-1,8-bis(diisopropylphosphino)methyl)-9H-carbazole – (CbzdiphosiPr)H (277 mg; 0.514 mmol) was added inside the Schlenk tube with an additional amount of toluene (5 mL). The Schlenk tube was closed, and outside the glovebox, the mixture was heated to 110 °C and stirred for 20 h. Afterward, the color changed from orange to green, and the temperature was cooled to room temperature. The solvent was pumped off under a vacuum until dry, and the crude green oil was dried under a vacuum for at least 1 h. The Schlenk tube was opened inside the glovebox, and the residue was washed with a mixture of n-pentane/hexamethyldisiloxane (HMDSO, 1/1 v/v), producing a green solid that was filtered into another Schlenk tube using a funnel. The remaining solution was pumped off, outside the glovebox, and dried under a vacuum for another 1 h. This procedure was repeated 3-fold or until no solid was observed after washing with the solvent mixture. Yield 80% (140 mg; 0.196 mmol). 1H NMR (600.1 MHz, C6D6, rt) δ 7.89 (s, 2H, HCarb), 7.35 (s br, 1H, HN), 7.23 (s, 2H, HCarb), 3.39 (d, JHH = 13.3 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.18 (dt, JHH = 13.4 Hz, JPH = 3.3 Hz 2H, CH2), 2.51–2.47 (m, 2H, CH(CH3)2), 2.13–2.08 (m, 2H, CH(CH3)2), 1.52 (vq, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H, CH(CH3)2), 1.45 (vq, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H, CH(CH3)2), 1.37 (s, 18H, C(CH3)3), 1.13–1.07 (m, 12H, CH(CH3)2). 13C NMR (150.9 MHz, C6D6, rt) δ (ppm): 148.8 (s, 2C, CCarb), 144.5 (t, JPH = 3.9 Hz, 2C, CCarb), 133.2 (s, 2C, CCarb), 126.0 (t, JPH = 2.5 Hz, 2C, CCarbH), 125.0 (s, 2C, CCarb), 115.2 (s, 2C, CCarbH), 34.9 (s, 2C, C(CH3)3), 31.8 (s, 6C, C(CH3)3), 26.0 (t, JPH = 5.9 Hz, 2C, CH2), 23.5 (t, JPH = 2.3 Hz, 2C, CH(CH3)2), 22.5 (t, JPH = 11.0 Hz, 2C, CH(CH3)2), 21.5 (s, 2C, CH(CH3)2), 20.6 (t, JPH = 10.0 Hz, 2C, CH(CH3)2), 19.5 (t, JPH = 2.1 Hz, 2C, CH(CH3)2), 16.4 (t, JPH = 2.2 Hz, 2C, CH(CH3)2). 31P{1H} NMR (242.9 MHz, C6D6, rt): δ (ppm): 66.0. 31P{1H} NMR (242.9 MHz, C6D6, rt) δ (ppm): 66.0. MS (LIFDI): m/z (%) calcd. for C34H55Cl2NP2Ru+ 710.7228, found 710.2271 (100) ([M]+). FTIR-ATR (cm–1): νP–C = 879; νC=C = 1460; νC–N = 1607; and νC-Hsp3 = 2952. UV/vis (THF solution, 0.5 × 10–3–3.1 × 10–5 mol L–1): λmax (nm), εmax [mol–1 L cm–1]; 418 (1335); 800 (1262). CV: Epa = −0.25; Epc = −0.44 V (ΔEp = 0.19 V); Ipa/Ipc = 1.01. ΔEp and Ipa/Ipc values of the [Fc]/Fc]+ couple under these conditions are 0.86 V and 0.83.

Catalysis

Decomposition of Ammonium Formate (AF) or Formic Acid (FA)

A standard experiment was carried out in a 50 mL three-way Schlenk tube, which allowed degassing the system with an argon atmosphere, adding or withdrawing chemicals, and releasing gases from the decomposition of AF or FA. Inside the glovebox, the Schlenk tube was loaded with AF (631 mg; 10 mmol), THF (10 mL), and a sample of [RuCl2(PNP)] (5.9 mg; 8.3 μmol; 0.08%) previously prepared in THF (1 mL). In the case of FA, the system was loaded with HMDSO (10 mL), FA (0.360 mL; 10 mmol), NEt3 (1.0 mL; 7.0 mmol), and the complex [RuCl2(PNP)] in the same amount as described in the decomposition of AF. Reactions were magnetically stirred in an oil bath at 80 °C, and the released gases were washed in two traps in the case of AF, one containing concentrated H2SO4 (100 mL) and other with NaOH (100 mL, 8 mol L–1). In the case of FA, the released gases were washed in a trap containing NaOH (100 mL, 8 mol L–1). The residual gas, hydrogen, was collected and measured in a 500 mL U-shaped graduated water column at atmospheric pressure. At the end of each run, the graduated water column was depressurized without allowing air to enter.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis, General Characterization, and Reactivity

The five-coordinate complex [RuCl2(PNP)] was synthesized from the well-known binuclear ruthenium precursor [RuCl2(p-cym)]2 in the presence of 2.1 eq. of the PNP ligand in toluene solution at 110 °C and 20 h {where PNP = 3,6-di-tert-butyl-1,8-bis(diisopropylphosphino)methyl)-9H-carbazole – (CbzdiphosiPr)H} (see Scheme 1). The 1H and 13C NMR (Figures S1 and S2) agree with the structure described in Scheme 1, which is supported by 2D NMR experiments, HSQC (heteronuclear single quantum coherence), and HMBC (heteronuclear multiple bond correlation) (see Figures S3 and S4, respectively). The 31P{1H} NMR data showed only a singlet signal at 66 ppm, consistent with similar complexes described in literature,43 when P atoms are coordinated trans to each other in a PNP moiety (Figure S5). FTIR-ATR spectroscopy provided the main stretching bands for PNP coordination in the metal center, such as νP–C = 879 cm–1; νC=C = 1460 cm–1; νC–N = 1607 cm–1; and νC-Hsp3 = 2952 cm–1 (Figure S6). Mass spectroscopy (LIFDI) calculated for C34H55Cl2NP2Ru+ 710.7228 m/z was found 710.2271 m/z (100) ([M]+) (Figure S7), validating the molecular formula and structure attributed in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Route and General Structure of [RuCl2(PNP)] (1).

Cyclic voltammetry (CV), which was swept anodically from −1.0 to 0.0 V, revealed an anodic peak potential (Epa) at −0.25 V and a cathodic peak potential (Epc) at −0.44 V, due to the Ru3+/Ru2+ redox pair. It corroborates the strong electron donating effect of the PNP ligand toward the Ru(II) center. The values observed for the potential variation (ΔEp) and Ipa/Ipc are lower than the values observed for the [Fc]/Fc]+ couple under the same conditions {where Fc = ferrocene}. A diffusion-controlled reversible process was confirmed by a linear relationship between current (I) versus the square root of the potential sweep rate (see Figure S8).

The UV/vis spectra (Figure S9) scanned from 1500 until 220 nm of [RuCl2(PNP)] in THF solution (0.5 × 10–3–3.1 × 10–5 mol L–1) showed three absorption bands in λmax = 418, 491, and 800 nm and molar coefficient (εmax) = 1335, 488, and 1262 mol–1 L cm–1, respectively.

In the presence of KBEt3H (10 equiv), complex 1 produces a monohydride complex, which showed a singlet signal with the chemical shift at 45 ppm in the 31P{1H} NMR spectra. The 1H NMR data presented a triplet centered at −9.25 ppm, due to the heteronuclear coupling between the hydride and the P atoms (JHP = 16.4 Hz). Then, the NMR tube was heated at 70 °C for 16 h, and the color changed from yellowish orange to yellow. The 31P{1H} and 1H NMR data also changed to a singlet signal at 85 ppm and a multiplet at −9.25 ppm, respectively, suggesting the in situ formation of a ruthenium dihydride complex containing a PNP ligand (see Figure S10). A boron adduct at 4.4 ppm was also observed in the 31P{1H} spectra. The reactivity of 1 in the presence of ammonium formate (AF) produces an in situ species observed at 69.8 ppm in the 31P{1H}, which unshielded the P atoms of the PNP ligand. This result agrees with a replacement of the chlorine ligand by a stronger σ-donor formate ion (−OCOH) (Figure S11).

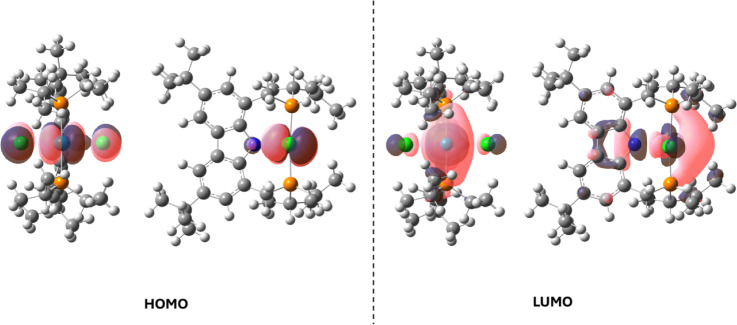

Five different functionals were used to optimize the structure of 1 by DFT calculations (see Table S1 and Figure S12). In general, the HOMO and LUMO orbitals obtained from the different functionals were quite similar. The functional base B3PW91 was chosen to describe the optimized structure because it represented intermediate values among the functionals used (Figure 1). The HOMO orbital is in the Cl–Ru–Cl moiety, while the LUMO orbital is positioned toward the carbazole ring, the halogen groups, and the sixth vacant site position. This latter result agrees with the remarkable catalytic activity of 1 in the decomposition of AF and FA, suggesting that an open site position is available for substrates in the core sphere of the complex. It is important to mention that the bulky PNP ligand forces a nearly linear angle to the Cl–Ru–Cl bonds (178°, see Table S1), which could allow a coordination of small species in the sixth position of the open site in an octahedral environment. A nucleophilic attack of the formate anion at the sixth position, from the deprotonation of FA or directly from the AF salt, could initiate the decomposition reaction, producing H2 and CO2 in the case of FA or H2, CO2, and NH3 in the case of AF.

Figure 1.

HOMO and LUMO orbitals of the optimized structure of 1, using the B3PW91 functional in THF. LANL2DZ basis for ruthenium, 6-31G for carbon and hydrogen, and 6-31G(d,p) for the remaining atoms.

Catalysis

The complex [RuCl2(PNP)] (1) catalyzed the decomposition of formic acid (FA) and ammonium formate (AF), separately or in a mixture of both. In a typical experiment for decomposing FA, 1 was loaded with 0.08%, and the released gases passed through a solution of NaOH (100 mL, 8 mol L–1) to absorb CO2 (Figure S13). In the case of AF decomposition, the gases also passed through a commercial H2SO4 solution trap (100 mL, 95–98%) to capture NH3. The remaining gas was identified as H2 by volumetric analysis and in the presence of a hydrogen acceptor (cyclohexene), which was hydrogenated to cyclohexane in the presence of the known complex [RuCl(H)(PPh3)3] as a catalyst in methanol solution (see Figure S14). Scheme 2 illustrates the production of H2 from AF and its use in the cyclohexene hydrogenation reaction.

Scheme 2. Production of H2 from AF and Its Use in the Cyclohexene Hydrogenation Reaction.

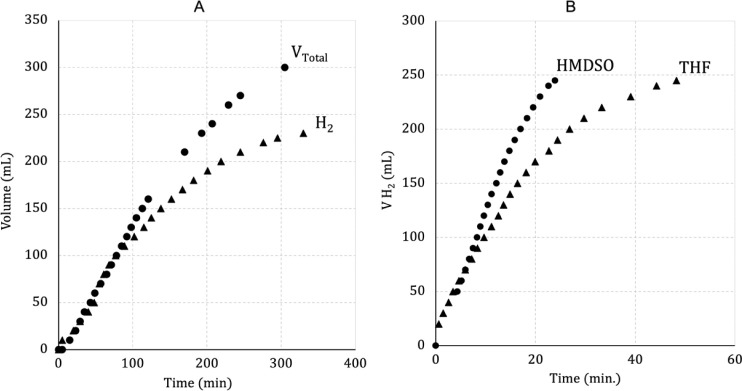

The decomposition reaction of AF (10 mmol) produced 94% H2 (230 mL) in THF solution within 330 min at 80 °C. It represents a turnover number (TON) of 1132 and a turnover frequency (TOF) of 206 h–1 in the pseudo-first order reaction with kobs = 3.4 × 10–2 min.–1. H2 was used in a parallel reaction, loaded with the complex [RuCl(H)(PPh3)3] (10 μmol), cyclohexene (5 mmol), and methanol (3 mL) (Figure S14). The H2 atmosphere was maintained for 20 h at 60 °C, and the hydrogenation reaction was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure S15). Therefore, cyclohexane was obtained in 7.4% yield, and no hydroformylation product was observed. It suggests, at least under these conditions, that the decomposition of AF does not produce carbon monoxide. However, a side reaction was observed as a polymerization of THF, producing a white rubber identified as poly-THF with 15% yield. This protocol was repeated for FA decomposition, and a similar amount of cyclohexane without coproducts was observed.

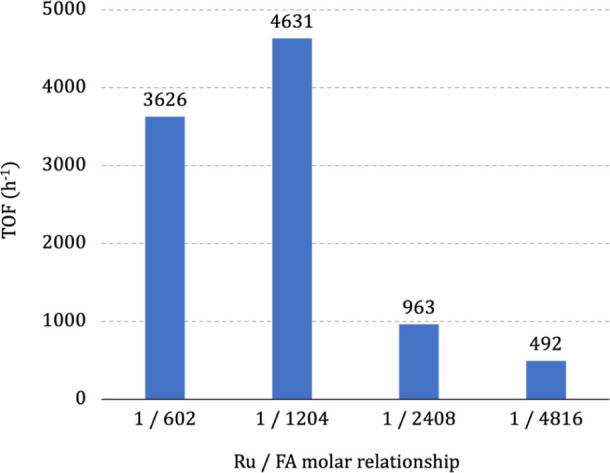

Varying the catalyst loading from 0.02 to 0.16% at 90 °C showed the best molar ratio for Ru/FA = 1/1204 or 0.08% of the ruthenium complex (Figure 2), which produced H2 at the rate of 4631 h–1. The amount of NEt3 was kept constant at 7 mmol in each catalytic run.

Figure 2.

Variation of catalyst loading at 90 °C for FA decomposition in the presence of NEt3 (7 mmol) in HMDSO solution (10 mL) containing THF (1 mL).

The catalytic activity of 1 in the decomposition of FA increases, reaching a maximum at the molar ratio 1/1204, and then decreases rapidly, due to the large amount of substrate (Figure 2). The best molar ratio for Ru/FA = 1/1204 or 0.08% of the ruthenium complex, producing 100% of H2 at a rate of 4631 h–1. With a high amount of FA, the complex becomes insoluble under the reaction conditions, reducing its catalytic activity. Therefore, as observed in Figure 2, only 10% of H2 was obtained at a 1/4816 catalyst/substrate molar ratio.

Table 1 summarizes the results for the decomposition of FA and AF using [RuCl2(PNP)] as a catalyst.

Table 1. Decomposition of FA and/or AF Using [RuCl2(PNP)] as a Catalysta.

| Entry | Substratea | Solvent | Base | Temp. (°C) | Time (h) | Volume (mL) | YH2 (%) | TON | TOF (h–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AFb | THF | --- | 80 | 5.0 | 300 | --- | --- | --- |

| 2 | AFb | THF | --- | 80 | 5.5 | 230 | 94 | 1132 | 206 |

| 3 | AFb | CH3OH | --- | 80 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | AFb | HMDSO* | --- | 80 | 5.3 | 160 | 66 | 786 | 149 |

| 5 | FAc | --- | NEt3 | 60 | 3.0 | 20 | 4 | 48 | 16 |

| 6 | FAc | HMDSO* | NEt3 | 80 | 0.4 | 245 | 100 | 1204 | 3010 |

| 7 | FAc | THF | NEt3 | 80 | 0.8 | 245 | 100 | 1204 | 1505 |

| 8 | FA/AFd | --- | --- | 60 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | FA/AFe | HMDSO* | --- | 80 | 1.2 | 245 | 100 | 1204 | 987 |

AF = ammonium formate. FA = formic acid. * 10 mL of HMDSO containing 1 mL of THF.

Molar ratio: Ru/AF = 1/1204.

Molar ratio: Ru/FA/base = 1/1204/843.

Molar ratio: Ru/FA/AF = 1/1204/120.

Molar ratio: Ru/FA/AF = 1/602/602.

The total amount of gases from the decomposition of AF in THF without traps (entry 1, Table 1) was slightly higher when compared to the reaction with a NaOH and H2SO4 trap (entry 2, Table 1), suggesting that CO2 and NH3 might be dissolved in the graduated water column, which was used to measure the amount of gases (Figures 3A and S14). It is important to mention that the maximum amount of H2 that could be generated in this protocol is 245 mL at room temperature (25 °C) and 1 atm. To avoid the THF polymerization reaction, methanol was used as a solvent, but in this case, the production of gases was not observed (entry 3). As a consequence of this, hexamethyldisiloxane (HMDSO) was chosen as a solvent, and 66% of H2 was obtained (entry 4) without polymers. When entries 2 and 4 are compared, it is evident that THF is the best solvent for AF decomposition, even though a secondary THF polymerization reaction is present.

Figure 3.

(A) Performance of the complex [RuCl2(PNP)] in the decomposition of AF with and without CO2 and NH3 traps. (B) Effect of the solvent on the catalytic performance of [RuCl2(PNP)] in the decomposition FA.

In this study, decomposition of FA without a solvent (entry 5) produced a small amount of H2, due to the low solubility of 1 in FA, and did not work without NEt3. To increase the catalytic activity of 1, HMDSO was added as a solvent (entry 6), producing 100% H2 in 24 min at a rate of 3010 h–1.

The TOF decreases by half in the THF solution (entry 7), due to the THF polymerization reaction (Figure 3B). The attempt to promote the decomposition of FA/AF without a solvent did not work due to the low solubility of the complex in the reaction medium (entry 8). However, in the presence of HMDSO as a solvent, an equimolar mixture of FA/AF was decomposed, and 100% H2 was obtained under mild conditions (entry 9).

In this last reaction, when the system was cooled at room temperature, a white solid was obtained in the reaction flask, which was filtered off and washed with HMDSO (3 × 5 mL), and dried in an air atmosphere. The physicochemical characterization of this white compound suggests the formation of carbamic acid, which can be obtained from the parallel reaction between CO2 + NH3 (see Figures S16 – S19).

The temperature dependence on the performance of 1 in FA decomposition showed an increase in the rate with increasing temperature in the range of 60–100 °C. Table 2 summarizes the kinetic results for 50% FA conversion.

Table 2. Kinectic Parameter for 50% FA Conversion Using [RuCl2(PNP)] as a Catalystabc.

| Entry | Temp (°C) | Time (h) | TON | TOF (h–1) | kobs × 10–2 (min.–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | 0.81 | 590 | 728 | 6.85 |

| 2 | 70 | 0.77 | 590 | 766 | 11.05 |

| 3 | 75 | 0.35 | 590 | 1685 | 22.34 |

| 4 | 80 | 0.21 | 590 | 2809 | 39.47 |

| 5 | 90 | 0.10 | 590 | 5900 | 50.89 |

| 6 | 100 | 0.09 | 590 | 6555 | 70.83 |

Solvent = HMDSO (10 mL) containing THF (1 mL).

Molar ratio Ru/FA/NEt3 = 1/1204/843.

[Ru] loaded = 0.08% related to FA.

It is interesting to note that at 100 °C, the catalytic performance of 1 was 10-fold faster than the performance at 60 °C. The kobs values on the temperature range described in Table 2 were used in the Arrhenius and Eyring plots (Figure 4), providing the activation energy as Ea = 64.0 kJ mol–1.

Figure 4.

Arrhenius and Eyring plot at the temperature range of 60–100 °C, due to the catalyst performance of 1 in the decomposition of FA.

This result fits well with results previously reported; Dupont and coworkers5 observed Ea = 69.1 kJ mol–1 using [{RuCl2(p-cymene)}2] dissolved in the ionic liquid for decomposing FA, while Singh and coworkers25 reported Ea = 87.9 kJ mol–1, using a half-sandwich cationic complex [(η6-C6H6)Ru(κ2-NpyNHMe-8-AmQ)Cl]+ as a catalyst.

From the Eyring plot, the activation entropy was obtained as ΔS‡ = −9.7 e.u., showing a transition state slightly lower entropic than the initial state. Care must be taken when interpreting the mechanism for reactions that have ΔS‡ between −10 and +10 e.u. because solvent reorganization can also contribute, especially for polar solvents and charged metal complexes.44 However, HMDSO is a very nonpolar solvent, and the target complex 1 is a neutral metal complex. It suggests, in the case of FA decomposition catalyzed by 1, a mechanism toward a concerted pathway. The activation variation enthalpy corroborates this idea, ΔH‡ = 61.0 kJ mol–1, which is low in the case of some coordination ligands in the core sphere of 1. The activation Gibbs variation energy was obtained as ΔG‡ = 13.35 kJ mol–1, suggesting nonspontaneous reactions.

In an attempt to promote FA decomposition without NEt3, the in situ complex [RuH2(PNP)] (2) generated from 1 was applied in an HMDSO solution with KBEt3H (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Performance of [RuH2(PNP)] (2) on the FA decomposition, started with NEt3 (triangle) and started without NEt3 (circle).

The catalytic performance of 2 on the FA decomposition showed total conversion within 0.41 h at 90 °C and TOF = 2938 h–1, while complex 1, under the same conditions, achieved total conversion in 0.26 h and TOF = 4631 h–1. In other words, complex 1 is almost twice as fast as 2. However, as mentioned above, complex 1 does not act as a catalyst for FA decomposition without NEt3, and it must be added at the beginning of the reaction.

In contrast, complex 2 started the reaction without NEt3 (Figure 5, circle), producing H2 up to a maximum: 60 mL or 24% of H2; TON = 289; TOF = 1926 h–1. Then, NEt3 (7.0 mmol) was added to the system, and the reaction restarted, producing a further amount of H2: 210 mL or 85% of H2, TON = 1032; TOF = 782 h–1. These results suggest that NEt3 participates herein as a cocatalyst on FA decomposition and plays a significant role in the process of H2 production from FA.

Conclusion

The complex [RuCl2(PNP)] (1) has been synthesized from the well-known binuclear precursor [RuCl2(p-cym)]2 and characterized as a five-coordinate coordination complex. Complex 1 catalyzed the decomposition of formic acid (FA) and ammonium formate (AF), separately or in a mixture of both. FA and AF decomposition produced H2 + CO2 and H2 + CO2 + NH3, respectively. H2 was identified by volumetric analysis in the presence of a hydrogen acceptor (cyclohexene). A concomitantly catalyzed THF polymerization reaction was observed in the decomposition of AF. A white solid, identified as carbamic acid, was also observed in the AF decomposition or in the decomposition of the FA/AF mixture due to the reaction between NH3 + CO2. In the case of FA decomposition catalyzed by 1, a kinetic study suggests a more associative mechanism than the mechanism catalyzed by other complexes under similar conditions. THF was found to be the best solvent for AF decomposition, while HMDSO was the best solvent for 1-catalyzed FA decomposition. The complex [Ru(H)2(PNP)] (2), prepared in situ, catalyzed the decomposition of FA but gave rise to a catalytic activity two times lower than that of 1. In contrast, 2 initiated FA decomposition without a base, while 1 needed the Brønsted–Lowry base from the beginning. NEt3 plays a significant role in the process of producing H2 from the decomposition of FA, and therefore must participate herein as a cocatalyst of the reaction.

Acknowledgments

Bogado, A.L acknowledges the financial support from the German Academic Exchange Service – DAAD (Research Stays for University Academics and Scientists, 2023/57681226) and Prof. Lutz H. Gade for hosting at the University of Heidelberg and for fruitful discussions about this work. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development – CNPq (Grants 404435/2021-1) and the Minas Gerais State Research Support Foundation – FAPEMIG (Grants APQ-00372-22). dos Santos, L da S. acknowledges Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - CAPES for the doctoral scholarship. We gratefully acknowledge the funding of the article processing charge by CAPES.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.4c09025.

A physicochemical characterization of [RuCl2(PNP), including NMR (1H, 13C, 1H–13C HSQC, 1H–13C HMBC, and 31P{1H}), FTIR-ATR, mass spectroscopy (LIFDI), cyclic voltammetry, and UV/vis data; a detailed description of the reactivity of the [RuCl2(PNP)] complex with KBEt3H and NH4HCO2, which was accompanied by 1H and 31P{1H} NMR experiments, suggesting an in situ preparation of [RuCl(H)(PNP)], [RuH2(PNP)], and [RuCl(OCOH)(PNP)] complexes; lastly, the DFT results of the target complex, as well as the catalysis gadgets, and characterization of carbamic acid are presented in detail (PDF)

The Article Processing Charge for the publication of this research was funded by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - CAPES (ROR identifier: 00x0ma614).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Sabatier P.; Maille A. Sur la decomposition catalytique de l’acide formique. Compt. Rendus 1911, 152, 1212–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Piola L.; Fernández-Salas J. A.; Nahra F.; Poater A.; Cavallo L.; Nolan S. P. Ruthenium-Catalysed Decomposition of Formic Acid: Fuel Cell and Catalytic Applications. Mol. Catal. 2017, 440, 184–189. 10.1016/j.mcat.2017.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loges B.; Boddien A.; Junge H.; Beller M. Controlled Generation of Hydrogen from Formic Acid Amine Adducts at Room Temperature and Application in H-2/O-2 Fuel Cells. Angew. Chem. 2008, 47 (21), 3962–3965. 10.1002/anie.200705972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellay C.; Dyson P. J.; Laurenczy G. A Viable Hydrogen-Storage System Based On Selective Formic Acid Decomposition with a Ruthenium Catalyst. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47 (21), 3966–3968. 10.1002/anie.200800320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholten J. D.; Prechtl M. H. G.; Dupont J. Decomposition of Formic Acid Catalyzed by a Phosphine-Free Ruthenium Complex in a Task-Specific Ionic Liquid. ChemCatchem 2010, 2 (10), 1265–1270. 10.1002/cctc.201000119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mellone I.; Gorgas N.; Bertini F.; Peruzzini M.; Kirchner K.; Gonsalvi L. Selective Formic Acid Dehydrogenation Catalyzed by Fe-PNP Pincer Complexes Based on the 2,6-Diaminopyridine Scaffold. Organometallics 2016, 35 (19), 3344–3349. 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Sun H.; Zuo Z.; Li X.; Xu W.; Langer R.; Fuhr O.; Fenske D. Activation of CO2, CS2, and Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid Catalyzed by Iron(II) Hydride Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016 (33), 5205–5214. 10.1002/ejic.201600642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W.; Wei Z.; Spannenberg A.; Jiao H.; Junge K.; Junge H.; Beller M. Cobalt-Catalyzed Aqueous Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid. Chem. - Eur. J. 2019, 25 (36), 8459–8464. 10.1002/chem.201805612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan C.; Zhang D. D.; Pan Y.; Iguchi M.; Ajitha M. J.; Hu J.; Li H.; Yao C.; Huang M. H.; Min S.; Zheng J.; Himeda Y.; Kawanami H.; Huang K. W. Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid Catalyzed by a Ruthenium Complex with an N,N′-Diimine Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56 (1), 438–445. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b02334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatsa A.; Mishra A.; Padhi S. K. Monitoring of Catalytic Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid by a Ruthenium (II) Complex through Manometry. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 144, 109898–109906. 10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agapova A.; Alberico E.; Kammer A.; Junge H.; Beller M. Catalytic Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid with Ruthenium-PNP-Pincer Complexes: Comparing N-Methylated and NH-Ligands. ChemCatchem 2019, 11 (7), 1910–1914. 10.1002/cctc.201801897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. H.; Ertem M. Z.; Xu S.; Onishi N.; Manaka Y.; Suna Y.; Kambayashi H.; Muckerman J. T.; Fujita E.; Himeda Y. Highly Robust Hydrogen Generation by Bioinspired Ir Complexes for Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid in Water: Experimental and Theoretical Mechanistic Investigations at Different PH. ACS Catal. 2015, 5 (9), 5496–5504. 10.1021/acscatal.5b01090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lentz N.; Streit Y.; Knörr P.; Albrecht M. Sterically and Electronically Flexible Pyridylidene Amine Dinitrogen Ligands at Palladium: Hemilabile Cis/Trans Coordination and Application in Dehydrogenation Catalysis. Chem. - Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202202672 10.1002/chem.202202672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary M. C.; Parkin G. Dehydrogenation, disproportionation and transfer hydrogenation reactions of formic acid catalyzed by molybdenum hydride compounds. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6 (3), 1859. 10.1039/C4SC03128H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Lu S. M.; Wu J.; Li C.; Xiao J. Iodide-Promoted Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid on a Rhodium Complex. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016 (4), 490–496. 10.1002/ejic.201501061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlivan P. J.; Loo A.; Shlian D. G.; Martinez J.; Parkin G. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes of Nickel, Palladium, and Iridium Derived from Nitron: Synthesis, Structures, and Catalytic Properties. Organometallics 2021, 40 (2), 166–183. 10.1021/acs.organomet.0c00679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behr A.; Nowakowski K.. Catalytic Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide to Formic Acid. In Advances in Inorganic Chemistry, Aresta M.; van Eldik R. Eds.; Academic Press, 2014; Vol. 66, pp. 223–258. [Google Scholar]

- Appel A. M.; Bercaw J. E.; Bocarsly A. B.; Dobbek H.; DuBois D. L.; Dupuis M.; Ferry J. G.; Fujita E.; Hille R.; Kenis P. J. A.; et al. Frontiers, Opportunities, and Challenges in Biochemical and Chemical Catalysis of CO 2 Fixation. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113 (8), 6621–6658. 10.1021/cr300463y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irfan R. M.; Wang T.; Jiang D.; Yue Q.; Zhang L.; Cao H.; Pan Y.; Du P. Homogeneous Molecular Iron Catalysts for Direct Photocatalytic Conversion of Formic Acid to Syngas (CO+H2). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (35), 14818–14824. 10.1002/anie.202002757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushwaha S.; Parthiban J.; Singh S. K. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Formic Acid/Formate Dehydrogenation and Carbon Dioxide/(Bi)Carbonate Hydrogenation in Water. Organometallics 2023, 42 (21), 3066–3076. 10.1021/acs.organomet.3c00286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frenklah A.; Treigerman Z.; Sasson Y.; Kozuch S. Formic Acid Dehydrogenation by Ruthenium Catalyst – Computational and Kinetic Analysis with the Energy Span Model. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 2019 (2–3), 591–597. 10.1002/ejoc.201801226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eppinger J.; Huang K. W. Formic Acid as a Hydrogen Energy Carrier. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 188–195. 10.1021/acsenergylett.6b00574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sordakis K.; Tang C.; Vogt L. K.; Junge H.; Dyson P. J.; Beller M.; Laurenczy G. Homogeneous Catalysis for Sustainable Hydrogen Storage in Formic Acid and Alcohols. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 372–433. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan W.; Fellay C.; Dyson P. J.; Laurenczy G. Influence of Water-Soluble Sulfonated Phosphine Ligands on Ruthenium Catalyzed Generation of Hydrogen from Formic Acid. J. Coord. Chem. 2010, 63 (14–16), 2685–2694. 10.1080/00958972.2010.492470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patra S.; Awasthi M. K.; Rai R. K.; Deka H.; Mobin S. M.; Singh S. K. Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid Catalyzed by Water-Soluble Ruthenium Complexes: X-Ray Crystal Structure of a Diruthenium Complex. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 2019 (7), 1046–1053. 10.1002/ejic.201801501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merz L. S.; Ballmann J.; Gade L. H. Phosphines and N-Heterocycles Joining Forces: An Emerging Structural Motif in PNP-Pincer Chemistry. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 2020 (21), 2023–2042. 10.1002/ejic.202000206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans G.; Karhu A. J.; Boddaert H.; Tanweer S.; Wunderlin D.; Bezuidenhout D. I. LNL-Carbazole Pincer Ligand: More than the Sum of Its Parts. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123 (13), 8781–8858. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.3c00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y. J.; Kwon Y.; Kim Y.; Sohn H.; Nam S. W.; Kim J.; Autrey T.; Yoon C. W.; Jo Y. S.; Jeong H. Development of an Autothermal Formate-Based Hydrogen Generator: From Optimization of Formate Dehydrogenation Conditions to Thermal Integration with Fuel Cells. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8 (26), 9846–9856. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c02775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrololná Z.; Červený L. Ammonium Formate Decomposition Using Palladium Catalyst. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2000, 26 (5), 489–497. 10.1163/156856700X00480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. P.; Zhang J.; Dai X. H.; Wang X.; Zhang S. Y. Formic Acid–Ammonium Formate Mixture: A New System with Extremely High Dehydrogenation Activity and Capacity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41 (47), 22059–22066. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z.; Mukhtar A.; Ludwig T.; Akhade S. A.; Kang S. Y.; Wood B.; Grubel K.; Engelhard M.; Autrey T.; Lin H. Efficient Pd on Carbon Catalyst for Ammonium Formate Dehydrogenation: Effect of Surface Oxygen Functional Groups. Appl. Catal., B 2023, 321, 122015–122027. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2022.122015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X. T.; Zhang J.; Chi J. C.; Li Z. H.; Liu Y. C.; Liu X. R.; Zhang S. Y. Efficient Dehydrogenation of a Formic Acid-Ammonium Formate Mixture over Au 3 Pd 1 Catalyst. RSC Adv. 2019, 9 (11), 5995–6002. 10.1039/C8RA09534E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anouar A.; Katir N.; El Kadib A.; Primo A.; García H. Palladium Supported on Porous Chitosan–Graphene Oxide Aerogels as Highly Efficient Catalysts for Hydrogen Generation from Formate. Molecules 2019, 24 (18), 3290. 10.3390/molecules24183290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar M.; Ferri D.; Elsener M.; Van Bokhoven J. A.; Kröcher O. Promotion of Ammonium Formate and Formic Acid Decomposition over Au/TiO2 by Support Basicity under SCR-Relevant Conditions. ACS Catal. 2015, 5 (8), 4772–4782. 10.1021/acscatal.5b01057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mellmann D.; Sponholz P.; Junge H.; Beller M. Formic Acid as a Hydrogen Storage Material – Development of Homogeneous Catalysts for Selective Hydrogen Release. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45 (14), 3954–3988. 10.1039/C5CS00618J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R.; Lu W.; Toan S.; Zhou Z.; Russell C. K.; Sun Z.; Sun Z. Thermocatalytic Formic Acid Dehydrogenation: Recent Advances and Emerging Trends. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9 (43), 24241–24260. 10.1039/D1TA05910F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armarego W. L. F.; Chai C. L. L.. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals, 6th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, 2009; pp. 717–743. [Google Scholar]

- Plundrich G. T.; Wadepohl H.; Gade L. H. Synthesis and Reactivity of Group 4 Metal Benzyl Complexes Supported by Carbazolide-Based PNP Pincer Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55 (1), 353–365. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallman P. S.; Stephenson T A.; Wilkinson G.. Inorganic Syntheses, Volume 12 Inorganic Syntheses; Wiley, 2007, 12, 237–240. [Google Scholar]

- Schunn R.; Wonchoba E.; Wilkinson G. Inorganic Syntheses, Volume 13. Inorg. Synth. 1972, 13, 131–134. 10.1002/9780470132449.ch26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb H. E.; Kotlyar V.; Nudelman A. NMR Chemical Shifts of Common Laboratory Solvents as Trace Impurities. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62 (21), 7512–7515. 10.1021/jo971176v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H., et al. Gaussian 09, Revision B.01; Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016.

- Xu Y.; Rettenmeier C. A.; Plundrich G. T.; Wadepohl H.; Enders M.; Gade L. H. Borane-Bridged Ruthenium Complex Bearing a PNP Ligand: Synthesis and Structural Characterization. Organometallics 2015, 34 (20), 5113–5118. 10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood J. D.Inorganic and Organometallic Reaction Mechanisms, 2nd ed.; WILEY-VCH Verlag: New York, 1997; pp. 13–15. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.