ABSTRACT

Primary graft dysfunction (PGD) is the most common cause of early mortality following heart transplantation. Although PGD can affect both ventricles, isolated right ventricular dysfunction (RV‐PGD) is observed in nearly half of PGD patients. RV‐PGD requires specific medical management to support the preload, afterload, and function of the failing RV; however, the use of mechanical circulatory support of the RV (RV‐MCS) might be required when optimal medical therapy is insufficient in preventing forward failure and retrograde venous congestion. While RV‐MCS options provide the opportunity to prevent or to recover from circulatory shock states, MCS is associated with a significant risk of complications. As a result of recent developments in short‐term mechanical support devices, less invasive, percutaneous options for RV‐MCS are available. In this review, we discuss the available devices, their advantages and disadvantages, and reported outcomes in RV‐PGD.

Keywords: heart transplant, primary graft dysfunction, mechanical circulatory support

1. Background

Heart transplantation (HTx) remains the gold standard therapy for end‐stage heart failure. Although survival after HTx has improved over the last decades, primary graft dysfunction (PGD) remains the most common cause of early death with a mortality of up to 35% [1, 2, 3] within 30 days posttransplant. The reported prevalence of PGD ranges from 1% to 33%, depending on the definition used [1, 4, 5, 6, 7]. In the literature, PGD is defined as severe cardiac allograft dysfunction requiring inotropic and/or mechanical circulatory support (MCS) within the first 24 h after HTx in the absence of secondary causes of graft failure, such as pulmonary hypertension, acute rejection, or technical complications of HTx. PGD can affect both the left and right ventricle of the transplanted heart, however, in up to 45% of cases it manifests as monoventricle RV dysfunction [7].

A formal definition for right ventricular PGD (RV‐PGD) has been introduced by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplant (Table 1) [8].

TABLE 1.

Definition of right ventricular primary graft dysfunction according to International Society of Heart and Lung Transplant criteria.

| Right ventricular primary graft dysfunction, a diagnosis requires criteria (i) and (ii), or (iii) alone |

|

Abbreviations: PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVAD, right ventricular assist device; sPAP; systolic pulmonary arterial pressure.

In the modified criteria by Alam et al., a severity classification has been added where severe RV‐PGD denotes RVAD requirement, and moderate RV‐PGD entails escalation of inotropic therapy, or the inability to wean off inotropes [9].

Although earlier reviews have described the use of MCS in primary graft failure after HTx, they are focused either on left ventricular (LV) PGD or on RV failure due to variety of causes including myocardial infarction and postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock [3, 10, 11]. In this review, we describe the pathophysiology, the treatment options, and indications for MCS, specifically in RV‐PGD patients. We emphasize the rationale behind different RV‐MCS options and discuss their inherent properties. Additionally, an overview of relevant MCS studies which include isolated RV‐PGD is provided.

1.1. Risk Stratification

Various risk factors for the development of PGD have been reported, and can be divided into donor risk factors, recipient risk factors, and intraoperative risk factors [8]. According to a 2020 consensus statement by Copeland et al. acceptable donor criteria include age < 55 years, normal LV ejection fraction, no valvular heart disease, no wall‐motion abnormalities, no LV hypertrophy, normal coronary angiogram, and a maximum of 20% donor–recipient weight mismatch [12]. Furthermore, in the case of gender mismatch, a female donor should be 10% larger in height and weight. Importantly, failure to meet these criteria does not exclude initiation of the donor procedure. Major recipient‐related factors include increasing age, the presence of pulmonary arterial hypertension and worse pretransplant clinical condition (such as dependence on inotropic support, MCS, and mechanical ventilation). A scoring system, the RADIAL score, for the prediction of PGD has been developed and identifies 6 factors with similar weight, including 4 recipient‐related factors (right atrial pressure [RAP] > 10 mmHg, age > 60 years, diabetes, dependence on inotropic support), 1 donor‐related (age > 30 years) and 1 procedure‐related factor (allograft cold ischemia time > 240 min). Additional risk factors include catecholamine release after donor‐related brain stem death [13], donor hyperoxia [14, 15], and ischemia–reperfusion injury following static cold storage, cardioplegia, and mechanical handling [16, 17, 18]. Noteworthy however, Moayedi et al. recently retrospectively assessed the RADIAL score and found a poor association with severe PGD [19]. With regard to isolated RV‐PGD, recipient age > 60 years, diabetes mellitus, and preoperative inotrope dependence were also found to be independent predictors [4]. Furthermore, both recipient female sex and high bilirubin levels preoperatively are known to be associated with severe RV‐PGD [17]. In the last couple of years, the emergence of donation after circulatory death (DCD) HTx procedures has increased the number of heart transplants worldwide [20]. Although in this procedure the donor heart is not exposed to the catecholamine surge following brainstem death, the warm ischemia time is considerably longer [18] due to the agonal phase the donor heart endures before procurement and the asystolic warm ischemia (time from circulatory arrest up until delivery of cardioplegia) time may play an important role in predicting PGD [21]. Furthermore, in the DCD procedure the heart is also exposed to significant pulmonary vasoconstriction during withdrawal of life support which may adversely affect right ventricular function [21]. In one study, higher rates of PGD after DCD HTx have been reported compared with donation after brain death (DBD) procedures, however biventricular function at 1‐week post‐implantation did not differ [22]. In a 2021 cohort where DCD hearts were preserved with cold static storage after a period of normothermic regional prefusion (NRP) in the donor, no patients developed PGD and no MCS was required post transplantation [23]. Messer et al. compared NRP with direct procurement and perfusion (DPP), where no difference was seen in outcomes (including survival, cardiac performance, need for MCS, and rejection) [24]. In another recent study, 180 recipients were randomized to receive either a DCD or DBD heart allograft: no difference was seen in 6‐month survival [20] with the incidence of PGD low and comparable between the two groups.

1.2. Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of RV‐PGD remains elusive but postoperative myocardial edema is a common finding which may in turn lead to both RV diastolic dysfunction and coronary microcirculatory flow impairment [16]. Furthermore, the use of inotropic therapy itself may increase myocardial oxygen demand and calcium overload which may further exacerbate cardiac dysfunction [16, 17]. The association of RV‐PGD with other systemic inflammatory states occurring in the recipient resulting in concurrent vasoplegia and RV failure has yet to be elucidated. Peak right ventricular failure (highest RAP) occurs typically in the first 3 days following HTx with a median RV recovery time of 5 days (range 2–14 days) [17].

1.3. Treatment Options for RV‐PGD

1.3.1. Maximum Medical Therapy

In RV‐PGD, medical support is initially focused on the main principles of optimization of preload, improvement of RV contractility, and reduction of RV afterload. Monitoring of the preload with pressure modalities (e.g., a Swan Ganz catheter) and imaging techniques (echocardiography) is vital with interventions including the administration of vasopressors and/or diuretics. In cases of high pulmonary vascular resistance, inhaled nitric oxide or prostaglandins may be administered in combination with systemic pulmonary vasodilators. In the case of a high pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) lusitropes (vasoactive medication which causes ventricular relaxation, i.e., milrinone) may be administered to optimize LV diastolic function. The effect of positive pressure ventilation on the RV afterload must also be considered with the avoidance of high ventilatory pressures. Furthermore, hypoxia and hypercapnia should be corrected due to their pulmonary vasoconstrictive effects.

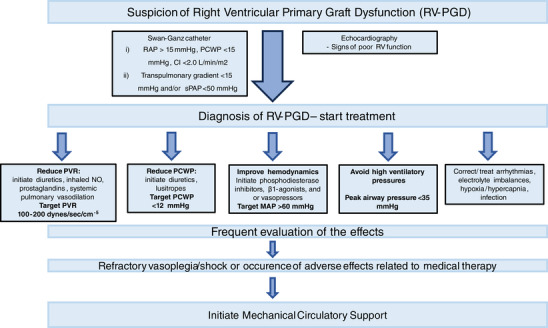

Enhanced RV contractility can be achieved by incorporating inotropes such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors and/or β1‐agonists. However, it is important to acknowledge that the effectiveness of inotropic agents is limited by the decreased chamber capacitance [16]. Additionally, inotropic therapy often leads to significant adverse effects, including arrhythmias, increased myocardial oxygen demand, diminished coronary perfusion leading to secondary myocardial ischemia, systemic hypotension, metabolic acidosis, calcium overload, as well as possible elevated pulmonary and systemic (microvascular) resistance [25, 26]. Furthermore, due to the development of tachyphylaxis, it may be necessary to administer consistently higher doses consequently amplifying the risk of adverse events. Persistent vasoplegia/shock, and/or the emergence of side effects related to medical therapy may prompt escalation to RV‐MCS. Although clinical parameters and hemodynamics might differ between patients, we propose an algorithm for the escalation of therapy to guide the clinical decision‐making in case of RV‐PGD (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Proposed algorithm for the initiation of right ventricular mechanical support. CI, cardiac index; MAP, mean arterial pressure; NO, nitric oxide; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RV, right ventricular; sPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure.

1.3.2. Mechanical Support

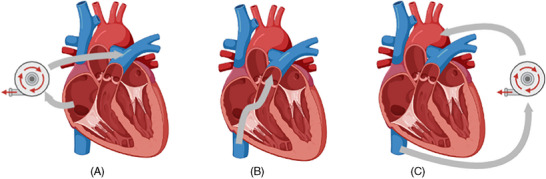

Options for mechanical RV support include devices that reduce RV preload and bypass the RV in either a right atrium to pulmonary artery (RA‐PA) configuration or a right atrium to systemic circulation configuration (RA‐Ao) (Figure 2) depending on the cannulation technique and the device itself.

FIGURE 2.

Mechanical circulatory support options for RV support. (A) RA‐PA RV bypass with extracorporeal pump (CentriMag, TandemHeart, ProtekDuo), (B) RA‐PA RV bypass with axial pump (Impella RP), (C) RA‐Ao right ventricular bypass with extracorporeal pump (V‐A ECMO). In the RA‐PA configuration, right ventricular preload (right atrial pressure) is reduced, while the mean pulmonary arterial pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure increase. Consequently, perfusion of the pulmonary circulation is preserved. Left ventricular afterload remains unchanged and the left‐sided cardiac output increases. In the case of a RA‐Ao configuration, a decrease is seen in right atrial pressure, mean pulmonary artery pressure, pulmonary artery pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, but a significant increase occurs in left ventricular afterload. The left sided cardiac output decreases, but overall organ perfusion is maintained. Created with BioRender.com. Ao, aorta; PA, pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; RP, right peripheral; V‐A ECMO, veno‐arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The choice of device may depend on the setting of the implantation: if the RV‐MCS is indicated postbypass during the HTx itself, surgical cannulation may be preferred, cannulating the RA via cannulation of the femoral vein (either cut‐down or percutaneous cannulation) and the PA via a graft. In an emergency setting in the ICU posttransplant, an RA‐Ao configuration may be pragmatic due to ease of cannulation. If the patient is relatively stable and able to be transported to the catheterization lab, a percutaneous cannulation technique may be preferred, offering either an RA‐PA configuration or RA‐Ao depending on the device. Below, we describe the different RV‐MCS devices that may be used and the reported results in RV‐PGD (Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 2.

Mechanical circulatory support devices for right ventricular failure.

| Device | Cannulation | Maximum flow | Oxygenator possible | Systemic circulatory support | Anticoagulation | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CentriMag | Percutaneous of surgical | 10 L/min | Yes | No | Yes | |

| V‐A ECMO | Percutaneous or surgical | 5 L/min | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

| Tandem Heart | Percutaneous or surgical | 4 L/min | Yes | No | Yes | |

| ProtekDuo | Percutaneous (jugular) | 4 L/min | Yes | No | Yes |

|

| Impella RP | Percutaneous | 5 L/min | No | No | Yes |

|

Abbreviations: PA, pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium; RP, right peripheral; V‐A ECMO, veno‐arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

TABLE 3.

Overview of studies with heart transplantation patients requiring mechanical circulatory support for RV failure.

| Study | Design | Study population | Outcomes | Complications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CentriMag | Thomas et al. [27] | Retrospective | 34 HTx patients treated with CentriMag

|

Isolated RV‐PGD patients (n = 10):

|

Total population (n = 34)

|

| Bhama et al. [28] | Retrospective | 10 Htx patients with isolated RV‐PGD treated with CentriMag |

Weaned: 70% Early death: 40% Late death: 17% |

Bleeding: 40% Infection: 30% Arrhythmia: 40% |

|

| V‐A ECMO | Taghavi et al. [29] | Retrospective | 28 Htx patients with isolated RV‐PGD

|

Reduction in MPAP, RAP, PVRWeaned

|

Device related complications

|

| D'Allesandro et al. [30] | Retrospective | 394 HTx patients

|

Weaned from V‐A ECMO: 67% (n = 54) One‐year conditional survival: 94% (n = 54) |

Peripheral V‐A ECMO

|

|

| Marasco et al. [31] | Retrospective | 239 HTx patients

|

Weaned from V‐A ECMO: 86% (n = 39) | Peripheral V‐A ECMO

|

|

| Jung et al. [32] | Case series | 2 HTx patients with isolated RV‐PGD |

Weaned from V‐A ECMO: 100% Survival until discharge: 100% |

Transient foot drop (n = 1) | |

| Takeda et al. [33] | Retrospective | 597 HTx patients

|

Weaned from V‐A ECMO: 89% (n = 27) 30‐day mortality: 11% (n = 27) |

Major bleeding 30% Renal failure: 11% Sepsis: 7% |

|

| Tandem Heart | Kapur et al. [34] | Retrospective | 46 patients with RV failure treated with Tandem Heart (surgical or percutaneous)

|

Significant improvement in PAP, MAP, RAP, CI In‐hospital mortality: 57% (n = 46) |

Major bleeding: 44% Injury to pulmonary artery: 2 patients (surgical arm) |

| ProtekDuo | Carrozzini et al. [35] | Case series | 3 patients with RV‐PGD treated with ProtekDuo |

Significant improvements in MAP, CVP, venous saturation Weaned from ProtekDuo: 100% |

Acute kidney failure: 100% Internal jugular vein thrombosis (n = 1) |

| Impella RP | Cheung et al. [36] | Retrospective | 18 patients with RV failure treated with Impella RP and RD

|

RV‐PGD patients (n = 3):

|

None reported in RV‐PGD patients |

| Anderson et al. [37] | Prospective | 12 patients with RV failure (Cohort B)

|

Significant improvement in CI and CVP 30‐day survival: 58% (n = 12) |

Major bleeding (67%) | |

| Monteagudo Vela et al. [38] | Retrospective | 7 patients with RV failure

|

Significant improvement in MAP Both RV‐PGD patients died |

RV‐PGD patients:

|

|

| Qureshi et al. [39] | Retrospective | 12 patients with RV failure

|

Significant improvement in CVPRV‐PGD patients (n = 5)

|

Major bleeding (n = 1) |

Abbreviations: CI, cardiac index; CVP, central venous pressure; HTx, heart transplantation; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MPAP, mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PAP, pulmonary arterial pressure; PGD, primary graft dysfunction; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RD, right direct; RP, right peripheral; RV, right ventricular; RVAD, right ventricular assist device; RV‐PGD, right ventricular primary graft dysfunction; V‐A ECMO, veno‐arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

2. Observations

2.1. CentriMag Pump as RVAD

The CentriMag (Levitronix, Waltham, MA, USA) is a surgically implanted extracorporeal centrifugal pump that can support either the left or right ventricle or offer biventricular support. In the right‐sided support system, the inflow cannula is placed either in the right atrium surgically or percutaneously via the femoral vein. The outflow cannula is placed in the pulmonary artery, leading to bypassing of the RV. The device has the potential of generating up to 10 L/min of continuous flow although such high flows are not required in the RVAD configuration [40]. In a study by Thomas et al., 38 patients with PGD were treated with the CentriMag [27] of which 10 patients required the CentriMag in the RVAD position. Six of those ten patients died on support; one patient died after retransplantation. Bleeding was the most common complication of MCS therapy (70%). In 2009, Bhama et al. retrospectively analyzed 29 patients, of which 10 patients suffered from RV‐PGD [28]. The weaning rate was high (70%), and early mortality was 40% in the total population. The most common adverse events were major bleeding (requiring reoperation), infection, and arrhythmia.

2.2. Veno‐Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (V‐A ECMO)

V‐A ECMO primarily provides partial or full systemic circulatory support by drainage of venous blood from the right atrium or caval vein(s) and providing flow to the aorta (RA‐Ao) using a continuous‐flow centrifugal pump [41]. Vascular access can either be obtained through peripheral cannulation (using either a surgical cut‐down or percutaneous approach) of the femoral vessels, or by a central surgical approach where the inflow cannula may be two‐stage via the RA, and the outflow cannula positioned in the ascending aorta. In both setups, V‐A ECMO can provide flow up to 5 L/min. Although commonly used in left‐sided heart failure and massive pulmonary embolism, the V‐A ECMO has progressively been used in isolated RV failure due to other causes.

Most commonly seen complications are limb ischemia (most commonly associated with peripheral configuration), bleeding, hemolysis, canula‐related thrombotic events, device‐related infections, and LV distention and subsequent pulmonary edema due to increased LV afterload [20].

In 2004, Taghavi et al. compared V‐A ECMO with a surgically implanted RV assist device (Medtronic Bio‐Medicus circuit) in RV failure occurring immediately after HTx [42]. Although the difference in overall survival was not statistically significant, V‐A ECMO seemed superior to the RV assist device with regard to graft survival (54% vs. 7%, respectively), weaning from support (77% vs. 13%), and the need for retransplantation (7% vs. 40%). With regard to complications, no difference was seen between the two groups in terms of device‐related complications, bleeding, sepsis/multiorgan failure, acute renal failure, and minor neurological deficits. However, the nonrandomized nature of this study and the excessive time span (19 years) allows for a considerable amount of bias and may limit accurate translation to current‐day practice.

In 2010, two retrospective studies reviewed the use of V‐A ECMO in PGD after HTx. In both studies, more than 200 patients were analyzed [30, 31]. Weaning rates were relatively high (67% and 87%, respectively) and conditional survival was similar compared to patients who did not develop RV‐PGD. However, it is unclear how many patients in these cohorts were diagnosed with isolated RV‐PGD.

In a small case series by Jung et al., two patients received V‐A ECMO after isolated RV failure following HTx [32]. Both patients survived and the duration of V‐A ECMO was 4 and 5 days and no significant complications were reported.

More recently, Takeda et al. retrospectively analyzed the use of V‐A ECMO versus a continuous flow ventricular assist device (CentriMag) in 44 PGD patients [33]. Baseline characteristics were similar in both groups and RV‐PGD was the indication for device support in 4 and 2 patients, respectively. In‐hospital mortality was 19% for V‐A ECMO (n = 27) versus 41% for CentriMag. Eighty‐nine percent were weaned from V‐A ECMO and the 3‐year posttransplant survival was 66%. V‐A ECMO was associated with a lower incidence of major bleeding and renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy.

2.3. Tandem Heart

The Tandem Heart (LivaNova, London, UK) is a surgically or percutaneously placed extracorporeal centrifugal pump where a 21 French inflow cannula is inserted in the right atrium, and an outflow cannula in the femoral artery. In 2013, Kapur et al. retrospectively reviewed data from 46 patients (including five HTx patients) with RV failure who received a Tandem Heart as temporary circulatory support (THRIVE registry) [34]. In approximately half of these patients, cannulation was achieved percutaneously. A significant improvement within 48 h was seen in mean‐, right atrial‐, and pulmonary artery systolic pressure and cardiac index (CI) increased. In‐hospital mortality was 57%. No significant difference was seen between the two approaches (surgical vs. percutaneous) in terms of hemodynamic improvements or device‐related complications. The most common complication was major bleeding (44%).

2.4. ProtekDuo

More recently, single canulation techniques as a method of bypassing the right ventricle have been developed. The ProtekDuo (LivaNova, London, UK) is a 29 French dual‐lumen cannula device implanted through the jugular vein with the inflow located in the right atrium or ventricle, and the outflow in the pulmonary artery [35]. The cannula is connected to an extracorporeal pump which can provide a flow up to 4 L/min. If required, an oxygenator may be utilized in the circuit. One clear advantage of the ProtekDuo over other implanted devices is the possibility of early mobilization of the patient, enabling quicker recovery.

In 2021, Carrozzini et al. published a case series of patients supported with a ProtekDuo cannula which included three patients with RV‐PGD following HTx [35]. In these patients, systemic systolic and diastolic blood pressure increased substantially after ProtekDuo implantation, and central venous pressure (CVP) decreased significantly. ProtekDuo support time ranged from 4 to 12 days and all patients were successfully weaned. All patients developed acute kidney injury, possibly due to the critical patient condition before implantation, and one device‐related complication was reported (internal jugular vein thrombosis).

2.5. Impella RP

The Impella Right Peripheral (RP) (Abiomed, Danvers, MA, USA) is a percutaneously implanted micro axial single lumen pump (22 French) positioned in the inferior vena cava (inflow) and extending into the pulmonary artery (outflow), directly bypassing the right atrium and right ventricle. It can provide flow up to 5 L/min [37].

One of the first studies with the Impella for RV failure by Cheung et al. included patients who received either the Impella RP or Impella right direct (RD, surgically implanted) [36]. The study included 18 critically ill patients of whom the etiology of RV failure was predominantly RV infarction; only three patients had RV failure following HTx. In these patients, CI increased and CVP decreased after the initiation of Impella support. Of the three transplanted patients, two were successfully weaned, and one patient died of multiorgan failure. Hemolysis occurred in two patients in the total population. Today, the Impella RD is no longer in clinical use.

The RECOVER RIGHT study prospectively analyzed 30 patients with RV failure treated with the Impella RP [37]. The study was divided into two cohorts, where Cohort B consisted of 12 non‐LVAD patients, including five patients with isolated RV‐PGD. Thirty‐day survival in this cohort was 58%; survival of the RV‐PGD patients was not mentioned. CI increased and CVP decreased in nearly all patients. The most common complication was major bleeding (67%) and consisted mostly of chest or mediastinal reexploration, tamponade, or hemothorax.

In 2020, Monteagudo Vela et al. reported their initial experience with Impella RP in 7 patients (two patients post‐HTx) where a 30‐day survival rate of 58% was reported, with a significant improvement in systolic blood pressure and decrease in CVP. Both post‐HTx patients died in‐hospital (multiorgan failure and cerebral hemorrhage) [38]. A multicenter study with 12 patients (5 after HTx) performed by Qureshi et al. reported a reduction in CVP and a discharge survival rate of 83% [39].

2.6. Weaning

The appropriate timing and manner of RV‐MCS weaning plays a crucial role in the success of the RV support, however, no standardized protocols for weaning from RV‐MCS have been proposed or investigated. In the RECOVER RIGHT study, stepwise flow reduction has been used to wean from Impella RP [37]. There is growing data on different weaning strategies from VA‐ECMO however the reported strategies are most often evaluated in patients with left ventricle or biventricular failure [43]. The data on weaning from other RV support devices is scarce and future research is needed to improve the weaning strategies and guide the timing of MCS explantation in the clinical setting of RV‐PGD. Recent reviews by Randhawa et al. and Carnicelli et al. propose an approach to weaning temporary MCS [44, 45]. The important aspects of appropriate device weaning include the timing and the mode of weaning. In order to choose the right moment for device weaning, the readiness to wean should be assessed on a regular basis. As a general consideration, shock states should be recompensated at the time of weaning, guided by end‐organ function parameters in addition to general parameters such as normalized lactate levels. Inflammatory states should be stabilized as seen in the normalization or reduction of vasopressor doses and a decrease in inflammatory markers. Fluid balance should be normalized, with the removal of excessive extravascular fluid and edema, including extravascular lung water by either forced diuresis or hemofiltration. Ventilation parameters should be stabilized and as low as possible with adequate oxygenation and ventilation to ensure optimal RV afterload.

When the optimal conditions are met, weaning trials can be performed under inotropic support to avoid distension due to volume and/or pressure overload of the fragile RV when RV‐MCS flows are reduced. It is recommended to perform RV‐MCS weaning trials with adequate monitoring in place, including a Swan Ganz catheter and echocardiography. The most commonly monitored hemodynamic parameters during weaning include mean arterial and pulmonary pressures (MAP and mPAP respectively), RAP, PCWP, cardiac output, and/or index. Echocardiographic evaluation consists of evaluation of signs of recovery including assessment of tricuspid valve systolic excursion (TAPSE), RV free wall motion, observation of tricuspid valve function, observation of position of the intraventricular septum, and measurement of volumetric RV parameters in combination with an estimation of filling pressures.

When deciding to remove the RV‐MCS a risk‐benefit assessment should be performed, taking into consideration any possible adverse effects of the RV‐MCS and/or cannulation and the assessment of success of weaning. It is recommended to have a backup plan in place in the case that the RV subsequently fails again after removal of the RV‐MCS.

3. Conclusions

RV‐PGD following HTx is not uncommon and carries significant morbidity and mortality. First‐line treatment consists of optimal medical therapy (OMT) to improve RV contractility while attention is given to optimize pre and afterload conditions for the RV. If OMT proves to be inadequate, circulatory shock can ensue with subsequent organ failure due to forward failure and retrograde venous congestion. In this case, the RV cannot recover its function without the initiation of mechanical support. By bypassing the right ventricle in either an RA‐PA or RA‐Ao configuration, a significant reduction in RV preload can be achieved, allowing time and conditions for the RV to recover while organ perfusion is maintained. As demonstrated by the studies discussed in this review, RV‐MCS allows for significant improvements in CVP, MAP, and cardiac output.

Although there is increasing evidence for instigation of RV‐MCS, the studies discussed in this review are limited by design. No randomized controlled trials have been performed comparing RV‐MCS versus OMT alone and due to ethical considerations it is unlikely that these will be performed in the future. Furthermore, studies with RV failure only are lacking and most conclusions have to be drawn from the evaluation of a mixed population with biventricular failure and a variety of indications for RV support, including non‐HTx. Although the case series mentioned seems promising, publication bias cannot be neglected. Definite conclusions with regard to improved survival are difficult to make. Nevertheless, it has to be taken into account that mortality in PGD patients is high a priori, and general mortality in these case series would likely be even higher if no MCS had been instigated. In the end, MCS may remain as the only salvage option to allow for any chance of recovery.

Several factors, such as patients’ characteristics and clinical profile, should be taken into account when considering mechanical support of a failing RV after HTx. Careful patient selection is key to determining those who will benefit from device therapy, however, currently, there is not enough data to propose such a clinical profile. Moreover, the timing of initiation of MCS remains difficult. Current practice is to support the patient with inotropes, vasopressors, and pulmonary vasodilators, due to their availability and rapid action, and to escalate the doses and/or add additional vasoactive agents when the initial strategy fails. However, given the detrimental effects of those agents on the myocardium, including but not limited to increased (coronary) oxygen demand, early MCS should be considered at the moment of escalation of medication to prevent further RV deterioration [31]. The choice of MCS type should be patient‐tailored, however, at current time it is largely center‐bound and limited by both logistical and financial considerations.

Patients’ hemodynamic and metabolic status should be monitored closely for early recognition of RV‐PGD as well as progression despite medical therapy to ensure timely introduction of MCS. Moreover, even lower threshold for implantation of RV‐MCS immediately after HTx might seem reasonable in selected cases, for example, in patients with multiple risk factors for RV‐PGD.

The efficacy of MCS is presently limited by frequent complications. Bleeding, infection, hemolysis, and thromboembolic complications are commonly reported and contribute to overall morbidity and mortality. However, there is a learning curve associated with the use of these devices, and with growing experience, the incidence of adverse events should decline. Additionally, the appropriate choice of device and cannulation technique can reduce the number of complications. Percutaneous cannulation via the jugular vein may be superior to femoral access when it comes to infection, bleeding, possibility of patient mobilization, and patient comfort. The duration of device therapy correlates also with the number of complications, therefore, prolonged duration should be avoided unless strictly necessary. Close monitoring of the RV with appropriate hemodynamic parameters and regular echocardiography during support on RV‐MCS is warranted. This will aid the timely weaning of RV‐MCS when other conditions, such as control of inflammation and optimization of fluid balance have been met.

3.1. Future Perspectives

As previously mentioned, data from randomized controlled trials is lacking. Unfortunately, due to the complex characteristics and clinical profile of the RV‐PGD population requiring mechanical support, patient recruitment for trials poses a substantial challenge.

Therefore, studies prospectively comparing MCS versus OMT alone will most likely not be performed. Proper patient selection, the risk profile for onset and progression of RV‐PGD, ideal timing of MCS initiation, optimal duration of support, and weaning strategies should be further investigated through observational studies in order to improve the efficacy of device therapy in this clinical setting. Next to optimizing the clinical use of current devices, new technical developments may improve the safety and the outcomes of patients supported with MCS.

PGD carries a poor prognosis and remains the most common cause of in‐hospital death after HTx. In nearly half of patients, PGD manifests as RV failure only. As a bridge towards recovery, MCS is more frequently applied and immediate hemodynamic improvements have been reported. Multiple devices varying in mechanism of action, level of support provided, as well as safety profiles are available to mechanically support the RV. Although no randomized studies have been performed, the results from case series and observational studies are promising and warrant further research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- 1. Quader M., Hawkins R. B., Mehaffey J. H., et al., “Primary Graft Dysfunction After Heart Transplantation: Outcomes and Resource Utilization,” Journal of Cardiac Surgery 34 (2019): 1519–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lund L. H., Edwards L. B., Kucheryavaya A. Y., et al., “The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirtieth Official Adult Heart Transplant Report ‐ 2013; Focus Theme: Age,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 32 (2013): 951–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aleksova N., Buchan T. A., Foroutan F., et al., “Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Graft Dysfunction Early After Heart Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Journal of Cardiac Failure 29 (2023): 290–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Segovia J., Coso M. D. G., Barcel J. M., et al., “RADIAL: A Novel Primary Graft Failure Risk Score in Heart Transplantation,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 30 (2011): 644–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ibrahim M., Hendry P., Masters R., et al., “Management of Acute Severe Perioperative Failure of Cardiac Allografts: A Single‐Centre Experience With a Review of the Literature,” Canadian Journal of Cardiology 23 (2007): 363–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aubert S., Leprince P., Bonnet N., et al., “Institutional Report—Assisted Circulation: Limited Mechanical Circulatory Support Following Orthotopic Heart Transplantation,” Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery 5 (2006): 88–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cosío Carmena M. D. G., Gómez Bueno M., Almenar L., et al., “Primary Graft Failure After Heart Transplantation: Characteristics in a Contemporary Cohort and Performance of the Radial Risk Score,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 32 (2013): 1187–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kobashigawa J., Zuckermann A., Macdonald P., et al., “Report From a Consensus Conference on Primary Graft Dysfunction After Cardiac Transplantation,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 33 (2014): 327–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alam A., Milligan G. P., and Joseph S. M., “Reconsidering the Diagnostic Criteria of Right Ventricular Primary Graft Dysfunction: Reconsidering RV‐PGD Diagnosis,” Journal of Cardiac Failure 26 (2020): 985–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alam A., Baran D. A., Doshi H., et al., “Safety and Efficacy of ProtekDuo Right Ventricular Assist Device: A Systemic Review,” Artificial Organs 47 (2023): 1094–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kapur N. K., Esposito M. L., Bader Y., et al., “Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices for Acute Right Ventricular Failure,” Circulation 136 (2017): 314–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Copeland H., Hayanga J. W. A., Neyrinck A., et al., “Donor Heart and Lung Procurement: A Consensus Statement,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 39 (2020): 501–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yeh T., Wechsler A. S., Graham L., et al., “Central Sympathetic Blockade Ameliorates Brain Death‐Induced Cardiotoxicity and Associated Changes in Myocardial Gene Expression,” Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 124 (2002): 1087–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Copeland H., Knezevic I., Baran D. A., et al., “Donor Heart Selection: Evidence‐Based Guidelines for Providers,” The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kransdorf E. P., Rushakoff J. A., Han J., et al., “Donor Hyperoxia Is a Novel Risk Factor for Severe Cardiac Primary Graft Dysfunction,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 42 (2023): 617–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lim H. S., Ranasinghe A., Quinn D., Chue C. D., and Mascaro J., “Pathophysiology of Severe Primary Graft Dysfunction in Orthotopic Heart Transplantation,” Clinical Transplantation (2021): 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kaveevorayan P., Tokavanich N., Kittipibul V., et al., “Primary Isolated Right Ventricular Failure After Heart Transplantation: Prevalence, Right Ventricular Characteristics, and Outcomes,” Scientific Reports 13 (2023): 394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singh S. S. A., Dalzell J. R., Berry C., and Al‐Attar N., “Primary Graft Dysfunction After Heart Transplantation: A Thorn Amongst the Roses,” Heart Failure Reviews 24 (2019): 805–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moayedi Y., Truby L. K., Foroutan F., et al., “The International Consortium on Primary Graft Dysfunction: Redefining Clinical Risk Factors in the Contemporary Era of Heart Transplantation,” Journal of Cardiac Failure 30 (2024): 805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schroder J. N., Patel C. B., DeVore A. D., et al., “Transplantation Outcomes With Donor Hearts After Circulatory Death,” New England Journal of Medicine 388 (2023): 2121–2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joshi Y., Scheuer S., Chew H., et al., “Heart Transplantation From DCD Donors in Australia: Lessons Learned From the First 74 Cases,” Transplantation 107 (2023): 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chew H. C., Iyer A., Connellan M., et al., “Outcomes of Donation After Circulatory Death Heart Transplantation in Australia,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 73 (2019): 1447–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoffman J. R. H., McMaster W. G., Rali A. S., et al., “Early US Experience With Cardiac Donation After Circulatory Death (DCD) Using Normothermic Regional Perfusion,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 40 (2021): 1408–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Messer S., Page A., Axell R., et al., “Outcome After Heart Transplantation From Donation After Circulatory‐Determined Death Donors,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 36 (2017): 1311–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Overgaard C. B. and Džavík V., “Inotropes and Vasopressors: Review of Physiology and Clinical Use in Cardiovascular Disease,” Circulation 118 (2008): 1047–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harjola V. P., Mebazaa A., Čelutkiene J., et al., “Contemporary Management of Acute Right Ventricular Failure: A Statement From the Heart Failure Association and the Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function of the European Society of Cardiology,” European Journal of Heart Failure 18 (2016): 226–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thomas H. L., Dronavalli V. B., Parameshwar J., Bonser R. S., and Banner N. R., “Incidence and Outcome of Levitronix CentriMag Support as Rescue Therapy for Early Cardiac Allograft Failure: A United Kingdom National Study,” European Journal of Cardio‐thoracic Surgery 40 (2011): 1348–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bhama J. K., Kormos R. L., Toyoda Y., Teuteberg J. J., McCurry K. R., and Siegenthaler M. P., “Clinical Experience Using the Levitronix CentriMag System for Temporary Right Ventricular Mechanical Circulatory Support,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 28 (2009): 971–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taghavi S., Zuckermann A., Ankersmit J., et al., “Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Is Superior to Right Ventricular Assist Device for Acute Right Ventricular Failure After Heart Transplantation,” Annals of Thoracic Surgery 78 (2004): 1644–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. D'Alessandro C., Aubert S., Golmard J. L., et al., “Extra‐Corporeal Membrane Oxygenation Temporary Support for Early Graft Failure after Cardiac Transplantation,” European Journal of Cardio‐thoracic Surgery 37 (2010): 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marasco S. F., Vale M., Pellegrino V., et al., “Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Primary Graft Failure After Heart Transplantation,” Annals of Thoracic Surgery 90 (2010): 1541–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jung J. S., Son H. S., Lee S. H., Lee K. H., Son K. H., and Sun K., “Successful Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Right Heart Failure after Heart Transplantation ‐ 2 Case Reports and Literature Review,” Transplantation Proceedings 45 (2013): 3147–3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Takeda K., Li B., Garan A. R., et al., “Improved Outcomes From Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Versus Ventricular Assist Device Temporary Support of Primary Graft Dysfunction in Heart Transplant,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 36 (2017): 650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kapur N. K., Paruchuri V., Jagannathan A., et al., “Mechanical Circulatory Support for Right Ventricular Failure,” JACC Heart Failure 1 (2013): 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carrozzini M., Merlanti B., Olivieri G. M., et al., “Percutaneous RVAD with the Protek Duo for Severe Right Ventricular Primary Graft Dysfunction after Heart Transplant,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 40 (2021): 580–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cheung A. W., White C. W., Davis M. K., and Freed D. H., “Short‐Term Mechanical Circulatory Support for Recovery From Acute Right Ventricular Failure: Clinical Outcomes,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 33 (2014): 794–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Anderson M. B., Goldstein J., Milano C., et al., “Benefits of a Novel Percutaneous Ventricular Assist Device for Right Heart Failure: The Prospective RECOVER RIGHT Study of the Impella RP Device,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 34 (2015): 1549–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Monteagudo‐Vela M., Simon A., and Panoulas V., “Initial Experience With Impella RP in a Quaternary Transplant Center,” Artificial Organs 44 (2020): 473–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Qureshi A. M., Turner M. E., O'Neill W., et al., “Percutaneous Impella RP Use for Refractory Right Heart Failure in Adolescents and Young Adults—A Multicenter U.S. Experience,” Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 96 (2020): 376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. De Robertis F., Birks E. J., Rogers P., Dreyfus G., Pepper J. R., and Khaghani A., “Clinical Performance With the Levitronix Centrimag Short‐Term Ventricular Assist Device,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 25 (2006): 181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Keebler M. E., Haddad E. V., Choi C. W., et al., “Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Cardiogenic Shock,” JACC: Heart Failure 6 (2018): 503–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Taghavi S., Zuckermann A., Ankersmit J., et al., “Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Is Superior to Right Ventricular Assist Device for Acute Right Ventricular Failure after Heart Transplantation,” Annals of Thoracic Surgery 78 (2004): 1644–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hermens J. A. J., Meuwese C. L., Szymanski M. K., Gianoli M., van Dijk D., and Donker D. W., “Patient‐Centered Weaning From Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: ‘A Practice‐Oriented Narrative Review of Literature’,” Perfusion 38 (2023). 1349–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Carnicelli A. P., van D. S., Gage A., et al., “Pragmatic Approach to Temporary Mechanical Circulatory Support in Acute Right Ventricular Failure,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 43 (2024): 1894–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Randhawa V. K., Al‐Fares A., Tong M. Z. Y., et al., “A Pragmatic Approach to Weaning Temporary Mechanical Circulatory Support: A State‐of‐the‐Art Review,” JACC: Heart Failure 9 (2021): 664–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.