Abstract

Objectives

To examine quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) around childbirth in facilities in Belgium during the COVID-19 pandemic and trends over time.

Design

A cross-sectional observational study.

Setting

Data of the Improving MAternal Newborn carE in the EURO region study in Belgium.

Participants

Women giving birth in a Belgian facility from 1 March 2020 to 1 May 2023 responded a validated online questionnaire based on 40 WHO standards-based quality measures organised in four domains: provision of care, experience of care, availability of resources and organisational changes related to COVID‐19.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Quantile regression analysis was performed to assess predictors of QMNC; trends over time were tested with the Mann‐Kendall test.

Results

897 women were included in the analysis, 67% (n=601) with spontaneous vaginal birth, 13.3% (n=119) with instrumental vaginal birth (IVB) and 19.7% (n=177) with caesarean section. We found overall high QMNC scores (median index scores>75) but also specific gaps in all domains of QMNC. On provision of care, 21.0% (n=166) of women who experienced labour reported inadequate pain relief, 64.7% (n=74) of women with an instrumental birth reported fundal pressure and 72.3% (n=86) reported that forceps or vacuum cup was used without their consent. On experience of care, 31.1% (n=279) reported unclear communication, 32.9% (n=295) reported that they were not involved in choices,11.5% (n=104) stated not being treated with dignity and 8.1% (n=73) experienced abuse. Related to resources, almost half of the women reported an inadequate number of healthcare professionals (46.2%, n=414). Multivariable analyses showed significantly lower QMNC scores for women with an IVB (−20.4 in the 50th percentile with p<0.001 and 95% CI (−25.2 to −15.5)). Over time, there was a significant increase in QMNC Score for ‘experience of care’ and ‘key organisational changes due to COVID-19’ (trend test p< 0.05).

Conclusions and relevance

Our study showed several gaps in QMNC in Belgium, underlying causes of these gaps should be explored to design appropriate interventions and policies.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Midwifery, Quality in health care, PUBLIC HEALTH, Maternal medicine

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

A strength of this study is the use of a validated data collection tool, based on WHO standards, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) around childbirth and comparison across countries.

The study covered the complete COVID-19 period and included a time trend analysis, showing how quality of care evolved over time during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The survey was only available online, which will exclude women facing digital poverty.

Women’s responses regarding the QMNC are highly coloured by individual expectations, culture and norms.

Background

Childbirth should be a positive experience, ensuring women and their babies reach their full potential for health and well-being.1 When analysing quality of maternity care worldwide, two extreme situations have been described: too little, too late (TLTL) and too much, too soon (TMTS).2 While TLTL identifies care with inadequate resources, below evidence-based standards or care withheld or unavailable until too late to help. TMTS identifies care characterised by over-medicalisation, including the use of non-evidence-based interventions or interventions not appropriate for the case.2 Typical examples of overused interventions during childbirth are caesarean sections, inductions or augmentation of labour, episiotomies and fundal pressure. Both TLTL and TMTS are costly for health systems and can be dangerous for women and newborns.3,5 In addition, the literature indicates that women, both in low-income and high-income countries (HICs), are often not adequately informed and are minimally involved in decision-making prior to conducting these interventions during childbirth.5,8 Also, other aspects of experience of care such as privacy, quality of communication, respect and dignity have been described as substandard both in low-income countries and HICs.9 10

In Belgium, the quality of maternal and newborn health has been mainly explored focusing on clinical outcomes and the provision of care.11 12 Similar to neighbouring European countries, maternal and newborn health outcomes (such as mortality and morbidity) are among the best in the world.11 13 14 Nevertheless, reports also show high rates of interventions (such as caesarean sections and episiotomies) with a high variation between hospitals.11 This unexplained variation suggests that interventions are not always performed based on evidence and might be the result of organisational policies and health providers’ preferences.11 One prepandemic study also showed women often experience a lack of involvement in the decision-making process during childbirth in Belgium, negatively affecting experience of care.15 However, more research using validated instruments is needed to capture both experience and provision of childbirth care in Belgium.

On 11 March 2020, the WHO declared the COVID-19 pandemic as a public health emergency of international concern, which was declared as ended on 5 May 2023. Globally, studies have shown that COVID–19 negatively impacted the provision and experience of maternal and newborn healthcare, especially in the first year of the pandemic.16,18 Rapidly implemented measures (such as stringent lockdown measures, curfews, isolation of suspected and confirmed cases) to control the pandemic negatively affected the availability, utilisation and quality of essential maternal and newborn health services.17 A systematic review showed maternal and fetal outcomes worsened globally during the COVID-19 pandemic, with an increase in maternal deaths, stillbirth, ruptured ectopic pregnancies and maternal depression.19 20 However, outcomes show considerable disparity between different settings within and across countries18,20 and changes over time are yet to be explored.

Improving MAternal Newborn carE in the EURO region (IMAgiNE EURO) is a multicountry project that started at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, exploring through online surveys the perspective of women and healthcare providers (HCPs) on the quality of maternal and newborn care (QMNC) at childbirth in hospital settings. Two validated questionnaires were developed for this project, containing 80 prioritised WHO quality measures (out of the of more than 300 suggested by the WHO Standards for improving the QMNC).21 This paper presents detailed survey findings on QMNC and trends over time, from the perspective of women who gave birth in Belgium during the COVID‐19 pandemic, between March 2020 and May 2023.

Methods

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted and reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines and the checklist can be found in online supplemental material 1.22 As the first aim, overall quality of care was explored according to the WHO Quality of Care Measures. As a secondary aim, trends over time were analysed for the different subdomains.

Data collection

The IMAgiNE EURO project involved an online survey for women, translated into 23 languages, actively disseminated by project partners across the WHO European Region, including Belgium. This paper presents only the data collected from Belgium. A structured online questionnaire was used to collect data, recorded with Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap V.8.5.21) via a centralised platform.23 The process of questionnaire development, validation and previous use has been reported elsewhere24 25 and details can found in online supplemental material 2. The study was registered at the US National Library of Medicine under NCT04847336. The questionnaire for women included 40 questions on one key indicator each, equally distributed in four domains: the three domains of the WHO Quality measures,21 namely, provision of care, experience of care and availability of human and physical resources, plus an additional domain on key organisational changes related to the COVID‐19 pandemic.25

Two versions of the questionnaire were available, one tailored for women who experienced labour and one for women who did not (eg, women with caesarean section before labour started). Each included the 40 WHO standard-based prioritised quality measure with 34 measures in common. Labour was defined according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines.26 Questions on individual characteristics of the participants (eg, socioeconomic background, parity) were included. As reported elsewhere,25 40 indicators contributed to a composite QMNC Index, ranging from 0 to 100 for each of the four domains, for a total score ranging from 0 to 400 points and higher scores indicating higher adherence to the WHO Standards.27 The online questionnaire was disseminated in Belgium by social media (Facebook and X) and by distributing leaflets in maternity wards, postnatal clinics and creches. The leaflet contained a QR code and link, bringing participants to the online questionnaire. Dissemination materials were available in Dutch, French and English. Around 90% of the Belgian population has Dutch or French as mother tongue, while English is the most spoken language by foreigners living in Belgium.28 The Dutch and French leaflet directed participants immediately to the online survey (in Dutch and French, respectively), while the English flyer opened a landing page where participants could choose from 23 languages.

Participants

Only women who gave birth in a Belgian facility between March 2020 and May 2023 were included in this study, corresponding to the period the pandemic was officially declared by WHO.29 Women needed to be 18 years or older to be eligible for participation. Women who gave birth multiple times during the described period could fill in the questionnaire for each childbirth. Women were able to select their preferred language from 28 languages available for completing the questionnaire and participated by actively clicking on the link or scanning the QR code to access the questionnaire. There were no exclusion criteria based on mode of birth, maternal complications or other obstetric characteristics.

Data analysis

A minimum required sample size of 300 women was calculated, based on preliminary data from other studies on the hypothesis of an average QMNC Index (our primary outcome and dependent variable) of 75%±7.5% (300±30 points, out of 400) and confidence level of 99.5%. Cases with >20% missing values and suspected duplicates, identified using date and place of birth, sociodemographic and obstetric data, were identified and the most recent record was retained. For the primary aim, we calculated absolute frequencies and percentages for sociodemographic variables and for each of the 40 key quality measures. The QMNC index was presented as median and IQR because not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test for normality p<0.05).

In addition, we performed a multivariable quantile regression analysis with the QMNC Index as the dependent variable and with trimester, maternal age, parity, education, type of facility, mode of birth and presence of an obstetrician/gynaecologist directly assisting childbirth as independent variables. Quantile regression was chosen instead of linear regression since the QMNC Index was not normally distributed and owing to evidence of heteroskedasticity.30 We conducted a multivariable quantile regression with robust SEs and we modelled the median, the 0.25th and 0.75th quantile, given statistical evidence of heteroskedasticity for parity, mode of birth, place of birth of the woman (Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test p< 0.05, H0: homoskedasticity). The categories with the highest frequency were used as reference. For our secondary aim, we assessed the hypothesis that the QMNC Index improved over time during the pandemic period.31 We first evaluated time trends by trimester for total QMNC Index and subsequently for the QMNC Index by domain. Time trends were tested with the Mann‐Kendall test. All the tests were two-tailed and a p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version V.14 (Stata Corporation) and R V.4.1.1.32

Anonymity in data collection during the survey phase was ensured by not collecting any information that could disclose participant identity, such as facility of birth or day of birth of the woman. Data transmission and storage were secured by encryption.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

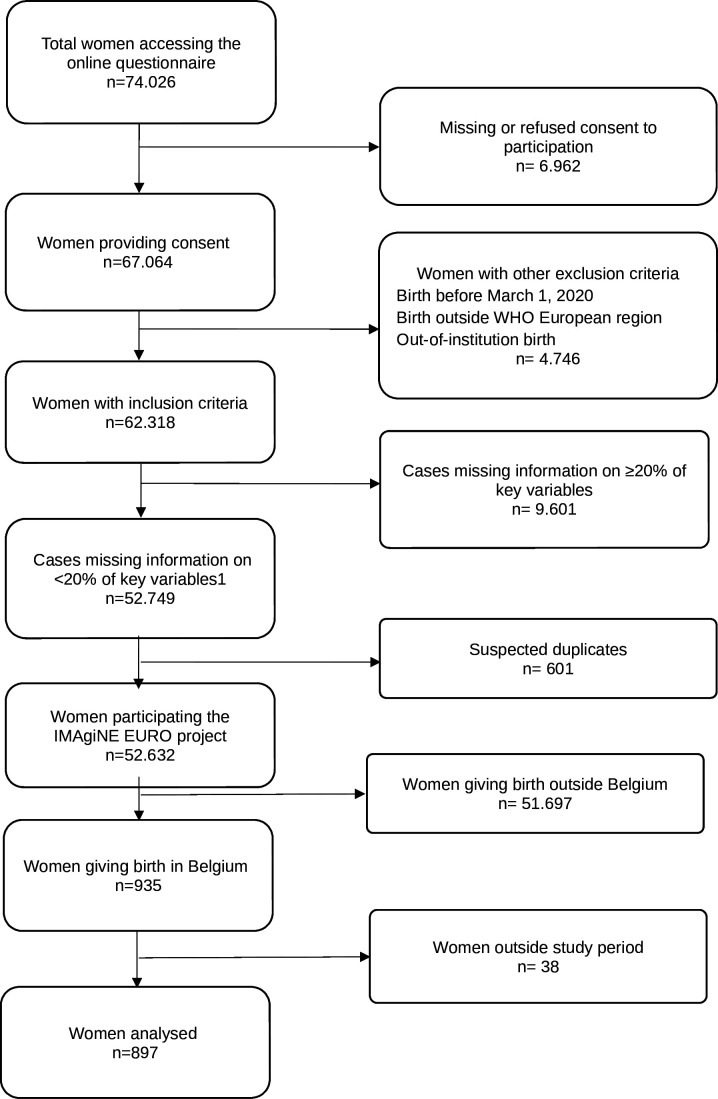

Of 74 026 women accessing the online questionnaire in all participating countries, 52 632 women fulfilled the inclusion criteria and responses from 897 women giving birth in Belgium were analysed after data cleaning (figure 1). The Dutch questionnaire was chosen by 83.8% (n=752) of women, the French questionnaire was chosen by 12.2% (n=109) of women, 1.7% (n=15) chose English, and the rest opted for one of the other available languages (table 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study sample of women. IMAgiNE EURO, Improving MAternal Newborn carE in the EURO region.

Table 1. Characteristics of responders (n=897).

| N | % | |

| Year of giving birth | ||

| 2020 | 313 | 34.9 |

| 2021 | 311 | 34.7 |

| 2022 | 178 | 19.8 |

| 2023 | 95 | 10.6 |

| Mother giving birth in the same country where she was born | ||

| Yes | 816 | 91.0 |

| No | 81 | 9.0 |

| Age range (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 21 | 2.3 |

| 25–30 | 298 | 33.2 |

| 31–35 | 436 | 48.6 |

| 36–39 | 107 | 11.9 |

| ≥40 | 35 | 3.9 |

| Educational level* | ||

| None | 0 | 0.0 |

| Elementary school | 6 | 0.7 |

| Junior high school | 94 | 10.5 |

| High school | 311 | 34.7 |

| University degree | 194 | 21.6 |

| Postgraduate degree/master/doctorate or higher | 292 | 32.6 |

| Birth mode | ||

| spontaneous vaginal birth | 601 | 67.0 |

| Instrumental vaginal birth | 119 | 13.3 |

| Caesarian section | 177 | 19.7 |

| Parity | ||

| 1 | 549 | 61.2 |

| >1 | 348 | 38.8 |

| Type of hospital | ||

| Public | 799 | 89.1 |

| Private | 98 | 10.9 |

| Type of healthcare providers who directly assisted birth | ||

| Midwife or nurse | 868 | 96.8 |

| A student (ie, before graduation) | 302 | 33.7 |

| Obstetrics registrar/medical resident (under postgraduation training) | 285 | 31.8 |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology doctor | 782 | 87.2 |

| I don't know (healthcare providers did not introduce themselves) | 33 | 3.7 |

| Other | 64 | 7.1 |

| Language in which questionnaire was filled | ||

| Dutch | 752 | 83.8 |

| French | 109 | 12.2 |

| English | 15 | 1.7 |

| Polish | 5 | 0.6 |

| German | 3 | 0.3 |

| Latvian | 3 | 0.3 |

| Swedish | 3 | 0.3 |

| Croatian | 2 | 0.2 |

| Greek | 2 | 0.2 |

| Portuguese | 2 | 0.2 |

| Italian | 1 | 0.1 |

| Other | ||

| Newborn admission to NICU | 102 | 11.4 |

| Maternal admission to ICU | 6 | 0.7 |

| Multiple births | 14 | 1.6 |

| Stillbirth | 6 | 0.7 |

Wording on education levels agreed among partners during the Delphi.

ICUintensive care unitNICUneonatal intensive care unit

Overall, most women (93.7%, n=841) were aged between 25 and 39 years and 54.2% (n=486) of women had university degree or higher. More than half of the women (61.2%, n=549) were primiparous (table 1). Frequencies of spontaneous vaginal birth (SVB) and instrumental vaginal birth (IVB) were 67.0% (n=601) and 13.3% (n=119), respectively, while frequencies for caesarean during labour, elective and emergency caesarean before labour were 8% (n=72), 3.1% (n=28) and 8.6% (n=77), respectively. Most women gave birth in a public hospital (89.1%, n=799). Almost all births were assisted by a midwife or nurse (96.8%, n=868) and 87.2% (n=782) of births were assisted by an obstetrics or gynaecology doctor. From all women, 11.4% (n=102) had a newborn admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit, 1.6% (n=14) had multiple births and 0.7% (n=6) had a stillbirth.

WHO-based quality measures

Key results for the domain of provision of care (table 2) were as follows: 21.0% (n=166) of women who experienced labour reported inadequate pain relief; 64.7% (n=77) of women with an IVB reported fundal pressure during childbirth; 35.8% (n=215) of women with SVB had an episiotomy; 4.6% (n=41) did not experience skin‐to‐skin contact with their newborn; 12.5% (n=112) reported no early breastfeeding; 10.9% (n=98) were not exclusively breastfeeding at discharge; 18.6% (n=167) reported inadequate breastfeeding support. From the women who underwent a caesarean section (n=177), 14.6% (n=26) reported inadequate pain relief after childbirth. Overall, one in three women reported they did not receive immediate attention when needed (29.2%, n=262).

Table 2. Results for WHO standards-based quality measures.

| Women experiencing labour | Women not experiencing labour | Overall (women experiencing labour and women not experiencing labour) | ||||

| N=792 | N=105 | N=897 | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Provision of care | ||||||

| 1. No pain relief during labour | 166 | 21 | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Mode of birth | – | – | ||||

| a. SVB | 601 | 75.9 | – | – | – | – |

| b. IVB | 119 | 15 | – | – | – | – |

| c. CS after labour | 72 | 9.1 | – | – | – | – |

| d. CS before labour | – | – | 28 | 26.7 | – | – |

| e. Elective caesarean | – | – | 77 | 73.3 | – | – |

| 3a. Episiotomy (in SVB) | 215/601 | 35.8 | – | – | – | – |

| 3b. Fundal pressure (in IVB) | 77/119 | 64.7 | – | – | – | – |

| 3c. No pain relief after caesarean | 9/72 | 12.5 | 17 | 16.2 | 26/177 | 14.6 |

| 4. No skin-to-skin contact | 23 | 2.9 | 18 | 17.1 | 41 | 4.6 |

| 5. No early breastfeeding | 84 | 10.6 | 28 | 26.7 | 112 | 12.5 |

| 6. Inadequate breastfeeding support | 149 | 18.8 | 18 | 17.1 | 167 | 18.6 |

| 7. No rooming-in | 71 | 9 | 13 | 12.4 | 84 | 9.4 |

| 8. Not allowed to stay with the baby as wished | 40 | 5.1 | 7 | 6.7 | 47 | 5.2 |

| 9. No exclusive breastfeeding at discharge | 83 | 10.5 | 15 | 14.3 | 98 | 10.9 |

| 10. No immediate attention when needed | 230 | 29 | 32 | 30.5 | 262 | 29.2 |

| Experience of care | ||||||

| 1a. No freedom of movements during labour | 189 | 23.9 | – | – | – | – |

| 1b. No consent requested for vaginal examination before prelabour caesarean | – | – | 21 | 20 | – | – |

| 2a. No choice of birth position (in SVB) | 276/601 | 45.9 | – | – | – | – |

| 2b. No consent requested (for IVB) | 86/119 | 72.3 | – | – | – | – |

| 2c. No information on newborn (after caesarean) | 16/72 | 22.2 | 16 | 15.2 | 32/172 | 18.1 |

| 3. No clear/effective communication from healthcare care provider (HCP) | 251 | 31.7 | 28 | 26.7 | 279 | 31.1 |

| 4. No involvement in choices | 260 | 32.8 | 35 | 33.3 | 295 | 32.9 |

| 5. Companionship not allowed | 74 | 9.3 | 10 | 9.5 | 84 | 9.4 |

| 6. Not treated with dignity | 88 | 11.1 | 16 | 15.2 | 104 | 11.6 |

| 7. No emotional support | 196 | 24.7 | 29 | 27.6 | 225 | 25.1 |

| 8. No privacy | 128 | 16.2 | 15 | 14.3 | 143 | 15.9 |

| 9. Abuse (physical/verbal/emotional) | 62 | 7.8 | 11 | 10.5 | 73 | 8.1 |

| 10. Informal payment | 11 | 1.4 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 1.3 |

| Availability of physical and human resources | ||||||

| 1. No timely care by HCPs at facility arrival | 71 | 9 | 11 | 10.5 | 82 | 9.1 |

| 2. No information on maternal danger signs | 343 | 43.3 | 51 | 48.6 | 394 | 43.9 |

| 3. No information on newborn danger signs | 442 | 55.8 | 55 | 52.4 | 497 | 55.4 |

| 4. Inadequate room comfort and equipment | 203 | 25.6 | 29 | 27.6 | 232 | 25.9 |

| 5. Inadequate number of women per rooms | 69 | 8.7 | 11 | 10.5 | 80 | 8.9 |

| 6. Inadequate room cleaning | 145 | 18.3 | 23 | 21.9 | 168 | 18.7 |

| 7. Inadequate bathroom | 134 | 16.9 | 16 | 15.2 | 150 | 16.7 |

| 8. Inadequate partner visiting hours | 320 | 40.4 | 46 | 43.8 | 366 | 40.8 |

| 9. Inadequate number of HCPs | 364 | 46 | 50 | 47.6 | 414 | 46.2 |

| 10. Inadequate HCP professionalism | 197 | 24.9 | 22 | 21 | 219 | 24.4 |

| Reorganisational changes due to COVID-19 | ||||||

| 1. Difficulties in attending routine antenatal Visits | 751 | 94.8 | 102 | 97.1 | 853 | 95.1 |

| 2. Any barriers in accessing the facility | 770 | 97.2 | 105 | 100 | 875 | 97.5 |

| 3. Inadequate infographics | 137 | 17.3 | 21 | 20 | 158 | 17.6 |

| 4. Inadequate ward reorganisation | 116 | 14.6 | 17 | 16.2 | 133 | 18.7 |

| 5. Inadequate room reorganisation | 109 | 13.8 | 13 | 12.4 | 122 | 13.6 |

| 6. Lacking one functioning accessible handwashing station | 28 | 3.5 | 6 | 5.7 | 34 | 3.8 |

| 7. HCP not always using personal protective equipment | 59 | 7.4 | 7 | 6.7 | 66 | 7.4 |

| 8. Insufficient HCP number | 205 | 25.9 | 33 | 31.4 | 238 | 26.5 |

| 9. Communication inadequate to contain COVID | 191 | 24.1 | 24 | 22.9 | 215 | 24.0 |

| 10. Reduction in QMNC due to COVID-19 | 238 | 30.1 | 39 | 37.1 | 277 | 30.9 |

Notes:Indicators identified with letters (eg, 3a, 3b) were tailored to take into account different mode of birth (ie, spontaneous vaginal, instrumental vaginal, and caesarean section). These were calculated on subsamples (eg, 3a was calculated on spontaneous vaginal births; 3b was calculated on instrumental vaginal births). Indicator 6six in the ‘reorganizsational changes due to COVID-19’ domain was defined as: at least one functioning and accessible hand-washing station (near or inside the room where the mother was hospitalizedhospitalised) supplied with water and soap or with disinfectant alcohol solution.

CS, caesarean section; HCP, healthcare care provider; IVB, instrumental vaginal birth; PPE, personal protective equipment; QMNC, quality maternal and newborn care; SVB, spontaneous vaginal birth

For experience of care, 32.9% (n=295) women reported that they were not involved in choices and 72.3% (n=86) were not asked for consent prior to an IVB. Overall, 1 in 10 women stated that they were not treated with dignity (11.6%, n=104), while 8.1% (n=73) were exposed to physical, verbal or emotional abuse. Nearly one in four women (23.9%, n=189) reported no freedom of movement during labour and 15.9% (n=143) reported a lack of privacy while almost none (1.3%, n=12) reported they performed informal payments. One in three women (31.1%, n=279) mentioned that the communication with healthcare professionals was unclear or ineffective.

For availability of human and physical resources, about half of women (46.2%, n=414) observed that staff were inadequate in number, while around half of women reported they received inadequate information on maternal and newborn danger signs (43.9%, n=394 and 55.4%, n=497, respectively). Room comfort, cleaning and number of women per room were rated as ‘inadequate’ by 25.9% (n=232), 18.7% (n=168) and 8.9% (n=80) of women, respectively, while 24.4% (n=219) respondents judged staff professionalism as inadequate.

For reorganisational changes due to COVID‐19, around one in three women (30.9%, n=277) reported that COVID‐19 had led to a reduction in QMNC and a high percentage of women reported difficulties in attending routine antenatal checks and experienced barriers in accessing the facility (95.1%, n=853 and 97.5%, n=875, respectively). Regarding staff, 7.4% (n=66) women noted that healthcare personnel were not always using personal protective equipment, while for one in four women (24%, n=215) the communication did not contain their stress related to COVID‐19‐required procedures. Overall 17.6% (n=158) rated the infographics as inadequate and 3.8% noted a lack of handwashing stations (n=34).

Predictors of QMNC indexes

Multivariable analysis showed that when adjusting the QMNC Index for other variables, only minor differences among groups were observed, except for women who had an IVB (table 3). Significantly lower QMNC indexes were reported by women aged above 40 (−12 in the 75th percentile, p=0.027, 95% CI (−17.4 to −6.6)) and women who had an IVB (−23.1 in the 25th centile, p=0.009, 95% CI (−31.9 to −14.3); −20.4 in the 50th centile, p<0.001, 95% CI (−25.2 to −15.5); −20 in the 75th centile, p<0;001, 95% CI (−24.5 to −15.5)). Significantly higher QMNC Index was reported on selected centiles for women who were not born in Belgium (+12 in the 75th centile, p=0.004, 95% CI (7.8 to 16.2)), with a university degree (+9.4 in the 50th centile, p=0.042, 95% CI (4.8 to 14.1)) or postgraduate degree (+12 in the 50th percentile, p=0.013, 95% CI (7.2 to 16.9); +9 in the 75th percentile, p=0.02, 95% CI (5.1 to 12.9)) and who gave birth in a facility with private offers (+8.7 in the 50th percentile, p=0.046, 95% CI (4.4 to 13.1)).

Table 3. Multivariate analysis predictors QMNC Index.

| 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | ||||

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

| Study trimester | 1.55 (0.9 to 2.2) | 0.019 | 0.93 (0.4 to 1.5) | 0.102 | 0.5 (0.1 to 0.9) | 0.261 |

| Parity | ||||||

| >1 | −7.8 (−13.1 to −2.5) | 0.144 | −4.8 (−8.9 to −0.7) | 0.239 | 0.5 (−2.6 to 3.6) | 0.87 |

| 1 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Mother giving birth in the same country where she was born | ||||||

| No | 12.2 (3.1 to 21.4) | 0.182 | 11.3 (2.3 to 20.3) | 0.209 | 12 (7.8 to 16.2) | 0.004 |

| Yes | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Type of facility | ||||||

| Private | 12.6 (3.8 to 21.3) | 0.151 | 8.7 (4.4 to 13.1) | 0.046 | 8.5 (3.8 to 13.2) | 0.072 |

| Public | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Maternal age (years) | ||||||

| 18–24 | −7.1 (−39.5 to 25.4) | 0.827 | −0.4 (−18.6 to 17.8) | 0.984 | −1.5 (−17.5 to 14.5) | 0.925 |

| 25–30 | −12.1 (−18.3 to −5.8) | 0.055 | −4.6 (−9.6 to 0.3) | 0.352 | 1.5 (−2 to 5) | 0.669 |

| 31–35 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| 36–39 | 8.4 (−0.1 to 17) | 0.322 | 6.3 (0.6 to 12) | 0.267 | 1.5 (−2.2 to 5.2) | 0.687 |

| ≥40 | 7.6 (−0.2 to 15.4) | 0.333 | −5.7 (−12.9 to 1.4) | 0.424 | −12 (−17.4 to −6.6) | 0.027 |

| Maternal education | ||||||

| Elementary school | 4 (−43.7 to 51.6) | 0.934 | −22.8 (−55.2 to 9.6) | 0.482 | −3 (−27.2 to 21.2) | 0.901 |

| Junior high school | −15.7 (−29 to −2.4) | 0.240 | −11.7 (−19.4 to −3.9) | 0.132 | −8 (−17 to 1) | 0.374 |

| High school | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| University degree | 4.7 (−2.4 to 11.7) | 0.510 | 9.4 (4.8 to 14.1) | 0.042 | 5 (1.1 to 8.9) | 0.203 |

| Postgraduate degree/master/doctorate or higher | 10.2 (5 to 15.3) | 0.050 | 12 (7.2 to 16.9) | 0.013 | 9 (5.1 to 12.9) | 0.020 |

| Mode of birth | ||||||

| Spontaneous vaginal birth | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Instrumental vaginal birth | −23.1 (−31.9 to −14.3) | 0.009 | −20.4 (−25.2 to −15.5) | <0.001 | −20 (−24.5 to −15.5) | <0.001 |

| Caesarian section | −12.2 (−20.4 to −4.1) | 0.132 | −6.1 (−11.3 to −0.9) | 0.24 | −3 (−6.8 to 0.8) | 0.432 |

| Presence of an OB/GYN directly assisting childbirth | ||||||

| Yes | 17.2 (10.2 to 24.2) | 0.014 | 16.1 (8.8 to 23.4) | 0.028 | 9 (4.7 to 13.3) | 0.039 |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

OB/GYN, obstetrician/gynaecologist

Trends over time for QMNC indexes

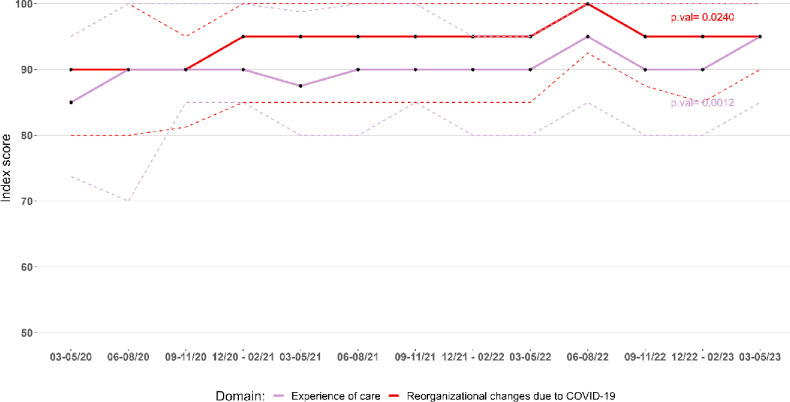

The median QMNC Index scores for each domain (experience of care, provision of care, availability of physical and human resources, key organisational changes related to the COVID-19 pandemic) varied between 75 and 100, depending on the study period (see online supplemental material 3). For the QMNC Index of experience of care and key organisational changes related to the COVID‐19 pandemic, a steady increase over time was observed. Experience of care increased from a median score of 85 points in the first study trimester to 95 points at study end, and key organisational changes related to the COVID‐19 pandemic evolved from a median score of 90 points in the first trimester to 95 points at study end (trend test p<0.05) (figure 2). The QMNC indexes in the domains of provision of care and availability of human and physical resources did not show any significant trend over time (see online supplemental material 3).

Figure 2. Lineplot showing the experiences of care and reorganisational changes due to COVID-19 indexes by study trimester. Figure shows the median (full line) and IQR (dotted line); the p values are obtained with Mann‐Kendall test for monotonic trend (H0: no monotonic trend).

Discussion

This is the first study exploring the perceived QMNC care at birth facilities in Belgium during COVID-19, using a set of 40 quality measures based on WHO Standards. Many of the quality measures explored, such as those related to the high rate of early breastfeeding, skin-to-skin contact, privacy and timely care, suggest high QMNC in Belgium. This is in line with the literature showing high satisfaction with maternity care in Belgium and high rankings of maternal and newborn health outcomes in Europe.1433,35 However, gaps in QMNC were also reported in our study for each domain: provision of care (eg, no pain relief after caesarean and inadequate breastfeeding support); experience of care (lack of consent request and involvement in choices); availability of resources (inadequate number of HCPs and HCP professionalism) and reorganisational changes (barriers in accessing the facility and reduction in QMNC due to COVID-19). Reports showed an improved trend over time in the domains of reorganisational changes due to COVID-19 and experience of care suggesting that the impact of COVID-19 was most severe in the first months of the pandemic.

Some study findings are of particular concern. In the domain of provision of care, the results showed that 64.6% of women with an IVB are subjected to fundal pressure. This is surprising, since both WHO and the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) do not recommend this practice, given its safety is yet unproven.36 37 Also, national guidelines state that ‘there are no medically validated indications for the application of fundal pressure, the traumatic experience of patients, their families and the occurrence of rare but serious complications are reasons for discontinuing its use’.38 More research will be needed to explore the underlying reasons for the high rates of fundal pressure in this study and how adherence to national and international guidelines can be improved. Similarly, the number of women who underwent episiotomy was high (35.8%), indicating this might still be performed without clear indication. In 2018, the WHO advised against routine or liberal use of episiotomy for normal childbirth1 and several expert groups refer to ≤5% as an acceptable rate.39 40

In the immediate postpartum period, we observed shortcomings in provision of care: a relative high proportion of women with a caesarean did not receive any pain relief and breastfeeding support seem inadequate. While quality of childbirth care is often evaluated by internal audits and registry data, the (immediate) postpartum care is often receiving less attention. Maternity wards might need more close feedback and audit mechanisms of women and their families to improve quality of (immediate) postpartum care and identify specific breaches in their organisation.41 42 Especially since there has been a continuing tendency in Belgium to improve efficiency and close smaller maternity units, which might have affected quality of care in a negative way.43 44

With respect to experience of care, a high proportion of women state involvement in decisions was limited, communication was inadequate and consent was not requested before performing interventions. Women with an IVB also reported lower QMNC scores. In addition, 11.6% of women reported she did not feel treated with dignity and 8.1% reported a form of abuse. Lack of communication and autonomy during childbirth is a serious concern and should be tackled to improve women’s experience. A recent review by Olde Loohuis et al found that communication skills can be enhanced by training and using additional communication tools, however, the importance of an enabling environment cannot be underestimated.45 The healthcare system in which health providers operate undoubtedly impacts the ability to effectively communicate and respect women’s choices. Enabling factors can include a non-excessive workload (allowing time to communicate), availability of adequate space and resources and a work atmosphere where teamwork, empathy and good communication are the norm.45 More research into these environmental factors and providers’ perspectives is highly needed in the Belgian context to tackle these shortcomings in childbirth care.

Related to the availability of human resources (inadequate number of HCPs and HCP professionalism) and reorganisational changes (barriers in accessing the facility and reduction in QMNC due to COVID-19), our study shows similar results as neighbouring countries. These findings confirm the numerous studies highlighting the indirect effects of COVID-19 on QMNC.2046,51 A study from the UK showed how mitigation measures caused social isolation of women and delays in care,49 while global reports show overall higher levels of fear and stress among both health providers and women.46 48

Our findings also showed that for the domains of experience of care and key organisational changes due to COVID-19 the QMNC indexes increased over time, which can be explained by several factors, including a better organisation of care over time, downscaling of restrictions and better anticipation of women on mitigation measures. Unfortunately, the lack of previous studies investigating comprehensively maternal perceptions of the QMNC (with the same WHO Quality measures used in this study) make it impossible to further assess to which extend the study findings may be associated with the pandemic. The IMAgiNE EURO study will perform other rounds of data collection, which will allow us to explore if quality gaps persist beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations and strengths

Limitations and strengths of the multicountry IMAgiNE EURO survey have been described elsewhere and are mainly related to the sampling method and recruitment of participants.5 All women needed to access internet for completing the survey, which will exclude women with limited digital skills or internet access. Specifically for Belgium we observed that our study sample is highly comparable to the overall population (based on national registry data of women giving birth in Belgium) but a slightly higher proportion of younger (<25) and primiparous women was observed.11 12 This difference might be related to the recruitment by social media, which might be more accessible to the younger population. In addition, only data from women was collected in this study. Data from health providers is needed, as well as qualitative data from women, to understand the underlying mechanisms causing the different gaps in quality of care in Belgium.

Conclusion

While the evidence overall suggests high QMNC in Belgium, our findings also highlighted several gaps in care. These gaps include inadequate and/or unclear communication from HCPs, lack of involvement in choices, inadequate staff number, frequent use of fundal pressure and inadequate pain management. These reported gaps in care should be analysed more in depth from a health system-based perspective to identify underlying causes and design appropriate interventions and policies. We also found that women’s experience of QMNC improved during the study period, but further research is needed to gain knowledge on QMNC beyond the pandemic and trends over time.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Health, Rome, Italy, in collaboration with the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS ‘Burlo Garofolo’, Trieste, Italy. We would like to thank all women who took their time to respond to this survey. We thank our colleagues from the Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Ghent University, the involved maternity hospitals and others who helped in the dissemination of the invitation to participate in the survey. Special thanks to the IMAgiNE EURO study group for their contribution to the development of this project and support for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by Italian Ministry of Health.

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-086937).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants. The IRCCS ‘Burlo Garofolo’ Trieste (IRB‐BURLO 05/2020 on 15 July 2020) and the Commission Medical Ethics, UZ Ghent (THE-2023-0075). The study was conducted according to General Data Protection Regulation requirements. Participation in the online survey was voluntary and anonymous. Prior to participation, women were informed of the objectives and methods of the study, including their rights in declining participation, and each participant provided consent before responding to the questionnaire. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Data availability free text: Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Collaborators: IMAgiNE EURO Study Group Austria: Martina König-Bachmann (Health University of Applied Sciences, Innsbruck, Austria), Christoph Zenzmaier (Health University of Applied Sciences, Innsbruck, Austria), Simon Imola (University of Applied Sciences Burgenland, Pinkafeld, Austria), Elisabeth D'Costa (Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria). Belgium: Anna Galle (UCVV, University Center Nursery and Midwifery at Ghent University.), Silke D’Hauwers (UCVV, University Center Nursery and Midwifery at Ghent University.). Bosnia-Herzegovina: Amira Ćerimagić (NGO Baby Steps, Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina). Cyprus: Ourania Kolokotroni (Cyprus University of Technology School of Health Sciences), Eleni Hadjigeorgiou (Cyprus University of Technology School of Health Sciences), Maria Karanikola (Cyprus University of Technology School of Health Sciences), Nicos Middleton (Cyprus University of Technology School of Health Sciences), Ioli Orphanide Eteocleous (Birth Forward NGO). Croatia: Daniela Drandić (Roda – Parents in Action, Zagreb, Croatia), Magdalena Kurbanović (Faculty of Health Studies, University of Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia). Czech Republic: Lenka Laubrova Zirovnicka (Association For Freestanding Birth Centres and Alongside Midwifery Units (APODAC)), Miloslava Kramná (Healthy Parenting Association (APERIO)). France: Rozée Virginie (Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Research Unit, Institut National d’Études Démographiques (INED), Aubervilliers, France), Elise de La Rochebrochard (Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Research Unit, Institut National d’Études Démographiques (INED), Aubervilliers, France), Kristina Löfgren (Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative (IHAB)). France. Germany: Céline Miani (Department of Epidemiology and International Public Health, School of Public Health, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld, Germany.), Stephanie Batram-Zantvoort (Department of Epidemiology and International Public Health, School of Public Health, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld, Germany.). Greece: Antigoni Sarantaki (Department of Midwifery, School of Health and Care Sciences, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece.), Dimitra Metallinou (Department of Midwifery, School of Health and Care Sciences, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece.), Aikaterini Lykeridou (Department of Midwifery, School of Health and Care Sciences, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece.). Israel: Ilana Chertok (Ohio University, School of Nursing, Athens, Ohio, USA: Ruppin Academic Center, Department of Nursing, Emek Hefer, Israel.), Rada Artzi-Medvedik (Ohio University, School of Nursing, Athens, Ohio, USA). Italy: Marzia Lazzerini (Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy), Emanuelle Pessa Valente (Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy), Ilaria Mariani (Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy), Arianna Bomben (Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy), Stefano Delle Vedove (Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy), Sandra Morano (University of Milano Bicocca, Italy.), Antonella Nespoli (University of Milano Bicocca, Italy.), Simona Fumagalli (University of Milano Bicocca, Italy.). Latvia: Elizabete Pumpure (Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Rīga Stradiņš University, Rīga, Latvia: Riga East Clinical University Hospital, Rīga, Latvia), Dace Rezeberga (Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Rīga Stradiņš University, Rīga, Latvia: Riga East Clinical University Hospital, Rīga, Latvia: Riga Maternity Hospital, Rīga, Latvia), Dārta Jakovicka (Rīga Stradiņš University, Rīga, Latvia,:Children's Clinical University Hospital, Rīga, Latvia.), Gita Jansone-Šantare (Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Rīga Stradiņš University, Rīga, Latvia), Anna Šibalova (Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Rīga Stradiņš University, Rīga, Latvia,), Elīna Voitehoviča (Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Rīga Stradiņš University, Rīga, Latvia), Dārta Krēsliņa (Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Rīga Stradiņš University, Rīga, Latvia,). Lithuania: Alina Liepinaitienė (Faculty of Natural Sciences, Department of Environmental Sciences, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania: Kauno kolegija Higher Education Institution, Kaunas, Lithuania: Republican Siauliai County Hospital, Siauliai, Lithuania), Andželika Kondrakova (Kauno kolegija Higher Education Institution, Kaunas, Lithuania), Marija Mizgaitienė (Kaunas Hospital of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania), Simona Juciūtė (Hospital of Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Kauno klinikos, Kaunas, Lithuania.). Luxembourg: Maryse Arendt1, Barbara Tasch (Beruffsverband vun de Laktatiounsberoderinnen zu Lëtzebuerg asbl (Professional association of the Lactation Consultants in Luxembourg), Luxembourg, Luxembourg: Neonatal intensive care unit, KannerKlinik, Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg, Luxembourg, Luxembourg.). Netherlands: Enrico Lopriore (Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands), Thomas Van den Akker (1 Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands: Athena Institute, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, Netherlands.). Norway: Ingvild Hersoug Nedberg (Department of health and care sciences, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Norway), Sigrun Kongslien (Department of health and care sciences, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Norway), Eline Skirnisdottir Vik (Department of health and caring sciences, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Norway.). Poland: Barbara Baranowska (Department of Midwifery, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw, Poland), Urszula Tataj-Puzyna (Department of Midwifery, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw, Poland), Beata Szlendak (Department of Midwifery, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw, Poland), Paulina Pawlicka (Division of Intercultural Psychology and Gender Psychology, University of Gdańsk, Gdańsk, Poland.). Portugal: Raquel Costa (EPIUnit - Instituto de Saúde Pública, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal: Laboratório para a Investigação Integrativa e Translacional em Saúde Populacional (ITR), Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal:Lusófona University, HEI‐Lab: Digital Human‐Environment Interaction Labs, Portugal), Catarina Barata (Instituto de Ciências Sociais,. Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal and Associação Portuguesa pelos Direitos da Mulher na Gravidez e Parto, Portugal), Teresa Santos (Universidade Europeia, Lisboa, Portugal: Plataforma CatólicaMed/Centro de Investigação Interdisciplinar em Saúde (CIIS) da Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon, Portugal) Heloísa Dias (Regional Health Administration of the Algarve, (ARS - Algarve, IP), Portugal), Tiago Miguel Pinto (Lusófona University, HEI‐Lab: Digital Human‐Environment Interaction Labs, Portugal), Sofia Marques (Institute of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Lusíada University, Porto, Portugal,: CIPD—Psychology for Development Research Centre, Lusíada University, Porto, Portugal), Ana Meireles (Institute of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Lusíada University, Porto, Portugal,:CIPD—Psychology for Development Research Centre, Lusíada University, Porto, Portugal), Joana Oliveira (Institute of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Lusíada University, Porto, Portugal: CIPD—Psychology for Development Research Centre, Lusíada University, Porto, Portugal), Mariana Pereira (CIPD—Psychology for Development Research Centre, Lusíada University, Porto, Portugal), Maria Arminda Nunes (Associação Portuguesa dos Enfermeiros Obstetras, Portugal: Nursing School of Porto, Porto, Portugal.). Romania: Marina Ruxandra Otelea (University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, Bucharest, Romania: SAMAS Association, Bucharest, Romania). Serbia :Jelena Radetić (Centar za mame, Belgrade, Serbia), Jovana Ružičić (Centar za mame, Belgrade, Serbia). Slovenia: Zalka Drglin (National Institute of Public Health, Ljubljana, Slovenia), Anja Bohinec (National Institute of Public Health, Ljubljana, Slovenia). Spain: Serena Brigidi (Institute of Research (VHIR), Vall d’Hebron University Foundation. Maternal and Fetal Medicine Research Group Medical Anthropology Research Center - MARC - Rovira i Virgili University, Tarragona, Spain. Department of Anthropology, Philosophy, and Social Work - Rovira i Virgili University, Tarragona, Spain. President of Observatory of Obstetric Violence in Spain), Alejandra Oliden (Nurse, La casa de Isis Birth Centre - Orba, Alicante, Spain Member of Observatory of Obstetric Violence in Spain – OVO), Lara Martín Castañeda (Institute of Research (VHIR), Vall d’Hebron University Foundation. Maternal and Fetal Medicine Research Group Medical Anthropology Research Center - MARC - Rovira i Virgili University, Tarragona, Spain. Department of Anthropology, Philosophy, and Social Work - Rovira i Virgili University, Tarragona, Spain. President of Observatory of Obstetric Violence in Spain – OVO: Nurse, La casa de Isis Birth Centre - Orba, Alicante, Spain Member of Observatory of Obstetric Violence in Spain – OVO.). Sweden: Helen Elden (Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden: Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Region Västra Götaland, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden), Karolina Linden (Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden), Mehreen Zaigham (Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Institution of Clinical Sciences Lund, Lund University, Lund and Skåne University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden). Switzerland: Claire de Labrusse (School of Health Sciences (HESAV), HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Lausanne, Switzerland), Alessia Abderhalden-Zellweger (School of Health Sciences (HESAV), HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Lausanne, Switzerland), Anouck Pfund (School of Health Sciences (HESAV), HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Lausanne, Switzerland), Harriet Thorn (School of Health Sciences (HESAV), HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Lausanne, Switzerland), Susanne Grylka (Institute of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Health Sciences, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences), Michael Gemperle (Institute of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Health Sciences, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences), Antonia Mueller (Institute of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Health Sciences, ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences)

Contributor Information

Anna Galle, Email: anna.galle@ugent.be.

Helga Berghman, Email: Helga.berghman@ugent.be.

Silke D’Hauwers, Email: silke.dhauwers@ugent.be.

Nele Vaerewijck, Email: nele.vaerewijck@ugent.be.

Emanuelle Pessa Valente, Email: emanuelle.pessavalente@burlo.trieste.it.

Ilaria Mariani, Email: ilaria.mariani@burlo.trieste.it.

Arianna Bomben, Email: arianna.bomben@burlo.trieste.it.

Stefano delle Vedove, Email: stefano.dellevedove@gmail.com.

Marzia Lazzerini, Email: marzia.lazzerini@burlo.trieste.it.

the IMAgiNE EURO Study Group, Email: urp@burlo.trieste.it.

the IMAgiNE EURO Study Group:

Martina König-Bachmann, Christoph Zenzmaier, Simon Imola, Elisabeth D'Costa, Anna Galle, Silke D’Hauwers, Ourania Kolokotroni, Eleni Hadjigeorgiou, Maria Karanikola, Nicos Middleton, Ioli Orphanide Eteocleous, Lenka Laubrova Zirovnicka, Miloslava Kramná, Rozée Virginie, Elise de La Rochebrochard, Antigoni Sarantaki Kristina, Dimitra Metallinou, Aikaterini Lykeridou, Marzia Lazzerini, Emanuelle Pessa Valente, Ilaria Mariani, Arianna Bomben, Stefano Delle Vedove, Sandra Morano, Antonella Nespoli, Simona Fumagalli, Elizabete Pumpure, Dace Rezeberga, Dārta Jakovicka, Gita Jansone-Šantare, Anna Šibalova, Elīna Voitehoviča, Dārta Krēsliņa, Alina Liepinaitienė, Andželika Kondrakova, Marija Mizgaitienė, Simona Juciūtė, Maryse Arendt, Barbara Tasch, Enrico Lopriore, Thomas Van den Akker, Barbara Baranowska, Urszula Tataj-Puzyna, Beata Szlendak, Paulina Pawlicka, Raquel Costa, Catarina Barata, Teresa Santos, Heloísa Dias, Tiago Miguel Pinto, Sofia Marques, Ana Meireles, Joana Oliveira, Mariana Pereira, Maria Arminda Nunes, Marina Ruxandra Otelea, Zalka Drglin, Anja Bohinec, Serena Brigidi, Alejandra Oliden, Lara Martín Castañeda, Helen Elden, Karolina Linden, Mehreen Zaigham, Claire de Labrusse, Alessia Abderhalden-Zellweger, Anouck Pfund, Harriet Thorn, Susanne Grylka, Michael Gemperle, and Antonia Mueller

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO recommendations. intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. :200. [PubMed]

- 2.Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M, et al. Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. The Lancet. 2016;388:2176–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seijmonsbergen-Schermers AE, van den Akker T, Rydahl E, et al. Variations in use of childbirth interventions in 13 high-income countries: A multinational cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2020;17:e1003103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maaløe N, Kujabi ML, Nathan NO, et al. Inconsistent definitions of labour progress and over-medicalisation cause unnecessary harm during birth. BMJ. 2023;383:e076515. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-076515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazzerini M, Covi B, Mariani I, et al. Quality of facility-based maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth during the COVID-19 pandemic: online survey investigating maternal perspectives in 12 countries of the WHO European Region. Lancet Reg Health Eur . 2022;13:100268. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simionescu AA, Horobeţ A, Marin E, et al. Who indicates caesarean section? A cross-sectional survey in a tertiary level maternity on patients and doctors’ profiles at childbirth. Obstet Ginecol. 2021;2:62. doi: 10.26416/ObsGin.69.2.2021.4977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otelea MR, Simionescu AA, Mariani I, et al. Womenʼs assessment of the quality of hospital‐based perinatal care by mode of birth in Romania during the covid ‐19 pandemic: Results from the imagine euro study. Intl J Gynecology & Obste . 2022;159:126–36. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Labrusse C, Abderhalden-Zellweger A, Mariani I, et al. Quality of maternal and newborn care in Switzerland during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study based on WHO quality standards. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;159 Suppl 1:70–84. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazzerini M, Covi B, Mariani I, et al. Quality of facility-based maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth during the COVID-19 pandemic: online survey investigating maternal perspectives in 12 countries of the WHO European Region. 2022. Available. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Shakibazadeh E, Namadian M, Bohren MA, et al. Respectful care during childbirth in health facilities globally: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BJOG. 2018;125:932–42. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goemaes R, Fomenko L, Laubach M, et al. Perinatale gezondheid in vlaanderen: jaar 2021. 2022

- 12.Elizaveta F. Perinatale gezondheid in vlaanderen jaar. 2022

- 13.EUROPEAN perinatal health report

- 14.Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division. [29-Feb-2024]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240068759 Available. Accessed.

- 15.Deherder E, Delbaere I, Macedo A, et al. Women’s view on shared decision making and autonomy in childbirth: cohort study of Belgian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:551. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-04890-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galle A, Semaan A, Huysmans E, et al. A double-edged sword-telemedicine for maternal care during COVID-19: findings from a global mixed-methods study of healthcare providers. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6:e004575. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Semaan A, Dey T, Kikula A, et al. “Separated during the first hours”—Postnatal care for women and newborns during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods cross-sectional study from a global online survey of maternal and newborn healthcare providers. PLOS Glob Public Health . 2022;2:e0000214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Curtis M, Villani L, Polo A. Increase of stillbirth and decrease of late preterm infants during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021;106:456. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e759–72. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Townsend R, Chmielewska B, Barratt I, et al. Global changes in maternity care provision during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinMed. 2021;37:100947. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.STANDARDS for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities

- 22.STROBE - Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology. [20-Feb-2024]. https://www.strobe-statement.org Available. Accessed.

- 23.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazzerini M, Mariani I, Semenzato C, et al. Association between maternal satisfaction and other indicators of quality of care at childbirth: a cross-sectional study based on the WHO standards. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e037063. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazzerini M, Argentini G, Mariani I, et al. WHO standards-based tool to measure women’s views on the quality of care around the time of childbirth at facility level in the WHO European region: development and validation in Italy. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e048195. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blix E, Huitfeldt AS, Øian P, et al. Recommendations | Intrapartum care | Guidance | NICE. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2012;3:147–53. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn health care in health facilities

- 28.Top languages in Belgium · Explore which languages are spoken in Belgium. https://www.languageknowledge.eu/countries/belgium Available.

- 29.Lenharo M. WHO declares end to COVID-19’s emergency phase. Nature New Biol. 2023 doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-01559-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams R. Heteroskedasticity

- 31.WHO chief declares end to COVID-19 as a global health emergency | UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/05/1136367 Available.

- 32.The Stata Blog. 2013. https://blog.stata.com/2013 Available.

- 33.Kuipers Y, De Bock V, Van de Craen N, et al. “Naming and faming” maternity care providers: A mixed-methods study. Midwifery. 2024;130 doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2023.103912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galle A, Van Parys A-S, Roelens K, et al. Expectations and satisfaction with antenatal care among pregnant women with a focus on vulnerable groups: a descriptive study in Ghent. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:112. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0266-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christiaens W, Gouwy A, Bracke P. Does a referral from home to hospital affect satisfaction with childbirth? A cross-national comparison. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright A, Nassar AH, Visser G, et al. FIGO good clinical practice paper: management of the second stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet . 2021;152:172–81. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.WHO labour care guide user’s manual

- 38.Richtlijn voor goede klinische praktijk bij laag risico bevallingen kce reports 139a

- 39.Kalis V, Rusavy Z, Prka M. Episiotomy. Childb Trauma. 2016:69–99. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4471-6711-2_6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.State of maternity care in the u.s.: the leapfrog group 2023 report on trends in c-sections, early elective deliveries, and episiotomies report highlights. 2023

- 41.Nijagal MA, Wissig S, Stowell C, et al. Standardized outcome measures for pregnancy and childbirth, an ICHOM proposal. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:953. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3732-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Depla AL, Lamain-de Ruiter M, Laureij LT, et al. Patient-Reported Outcome and Experience Measures in Perinatal Care to Guide Clinical Practice: Prospective Observational Study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:e37725. doi: 10.2196/37725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cuellar AE, Gertler PJ. How The Expansion Of Hospital Systems Has Affected Consumers. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:213–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The Effect of Hospital Size and Teaching Status on Patient Experiences with Hospital Care: A Multilevel Analysis on JSTOR. [29-Feb-2024]. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40221409 Available. Accessed. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Olde Loohuis KM, de Kok BC, Bruner W, et al. Strategies to improve interpersonal communication along the continuum of maternal and newborn care: A scoping review and narrative synthesis. PLOS Glob Public Health . 2023;3:e0002449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asefa A, Semaan A, Delvaux T, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on the provision of respectful maternity care: Findings from a global survey of health workers. Women Birth. 2022;35:378–86. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lalor J, Ayers S, Celleja Agius J, et al. Balancing restrictions and access to maternity care for women and birthing partners during the COVID-19 pandemic: the psychosocial impact of suboptimal care. BJOG. 2021;128:1720–5. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Semaan A, Audet C, Huysmans E, et al. Voices from the frontline: findings from a thematic analysis of a rapid online global survey of maternal and newborn health professionals facing the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e002967. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones IHM, Thompson A, Dunlop CL, et al. Midwives’ and maternity support workers’ perceptions of the impact of the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic on respectful maternity care in a diverse region of the UK: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e064731. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-064731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flaherty SJ, Delaney H, Matvienko-Sikar K, et al. Maternity care during COVID-19: a qualitative evidence synthesis of women’s and maternity care providers’ views and experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:438. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-04724-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vasilevski V, Sweet L, Bradfield Z, et al. Receiving maternity care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences of women’s partners and support persons. Women Birth. 2022;35:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]