Abstract

Background

Myogenic factor 6 (Myf6) plays an important role in muscle growth and differentiation. In aquatic animals and livestock, Myf6 contributes to improving meat quality and strengthening the accumulation of muscle flavor substances. However, studies on Myf6 gene polymorphisms in crustaceans have not been reported.

Results

In the current study, we characterized the Myf6 gene for Portunus trituberculatus to better understand its biological function. The full-length cDNA of Myf6 was 4,101 bp, with a 915 bp open reading frame encoding 304 amino acids. In addition, Myf6 included a conservative bHLH domain. Homology analysis showed that Myf6 shared the highest identity with Penaeus vannamei. Expression pattern analysis of Myf6 in fast- and slow-growing groups revealed that the expression level of the latter was significantly higher than that of the former (P < 0.05). qPCR studies revealed that Myf6 was expressed in various tissues with the highest level in muscle. Nineteen single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of Myf6 were identified and five of them were significantly associated with growth-related traits of P. trituberculatus (P < 0.05), including full carapace width, carapace length, body height, and body weight. The AG and GG genotypes of g.1,187,834 A > G exhibited superior growth-related traits than the AA genotype. In the combined genotypes of g.1,187,324 C > T and g.1,187,834 A > G, the average body weight of diplotype D5 (CT-GG) was higher than that of diplotype D1 (CC-AA), D2 (CC-AG), and D3 (CC-GG) in a cultivated population. A haploblock was generated by three significant SNPs (g.1187834 A > G, g.1188616 A > G, and g.1189024 C > A), containing four haplotypes (AAA, AAC, AGC, and GGC), among which GGC haplotype exhibited superior growth traits (full carapace width and body weight) than the AAA haplotype.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first report on Myf6 in crustaceans. The results of this study would contribute to elucidating multiple functions of the Myf6 gene in crustaceans and exploring the potential as a candidate gene in selective breeding programs of P. trituberculatus.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-024-11181-6.

Keywords: Portunus trituberculatus, Myf6, SNP, Growth-related traits, Association analysis

Background

Growth traits are a vital standard for the animal culture industry, especially for aquaculture, as they can directly affect yield [1, 2]. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms of growth regulation is of great importance for the genetic improvement of economic traits. However, growth traits are known to be quantitative traits and controlled by multiple genes, and the underlying physiological bases may involve complex regulatory networks of many interacting genes with different effects [3–5]. Nowadays, the association analysis between SNP loci detected within a candidate gene and the target trait is an effective strategy to elucidate the main genes affecting quantitative polygenic traits due to its advantages in specificity and accuracy [6–8]. Four SNPs in the 3′flanking and exon regions of the SIF gene showed significant association with growth traits (carapace length, body weight, etc.) in Portunus trituberculatus [9]. Six SNPs in the coding region of the LvMMD2 gene were significantly associated with body weight in Litopenaeus vannamei [10]. In addition, myostatin and its associations with growth traits in aquatic animals were investigated, such as Chlamys nobilis [11], Pagrus major [12], and Exopalaemon carinicauda [7].

Recently, the growth-related Myf6 gene was identified by a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of growth traits of 500 swimming crab individuals from three families in our laboratory (unpublished data). Nevertheless, association analysis between Myf6 polymorphisms and growth-related traits has not been reported in crustaceans. Myogenic determinant factor (MyoD), also known as myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs), is a family of genes that controls the proliferation and differentiation of muscle cells, which is closely related to the quantity and thickness of muscle fibers and has an extremely important impact on meat quality and unique flavor [13]. Nowadays, four members of the MyoD family have been found in mammals including Myf3, MyoG, Myf5, and Myf6, encoding four transcription factors with different functions, all of which contain a highly conserved basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) domain with myogenic potential [14–16]. Among them, Myf6 (Myogenic factor 6) is also known as MRF4 or herculin in different mammals [17]. The Myf6 gene is one of the leading regulatory genes for skeletal muscle development in vertebrates; At the late stage of skeletal muscle differentiation, its coding product can induce myoblasts to differentiate and fuse into myotubes, promote the formation of muscle fibers, and maintain muscle phenotype [18]. In Micropterus salmoides, the Myf6 gene was identified as directly related to skeletal muscle development and growth [19]. The cloning and expression of a Myf6 gene from zebrafish (Danio rerio) were reported, which showed conservation of linkage to Myf5 [20]. In addition, zebrafish Myf6 expression parallels the assembly of myosin protein into myofibrils. In Nubian goats, the expression of the Myf6 gene in the longissimus dorsi muscle was the highest, which provided insight into the role of the Myf6 gene in muscle differentiation [21].

The swimming crab (Portunus trituberculatus), the world’s most heavily fished crab species, is widely distributed in the eastern coasts of Asia and North Australia [22], with an annual world production of about 460,000 tons [23]. It is one of the most economically important marine aquaculture species, which has been widely cultivated in China due to its high nutritional value and fast growth [24]. However, the natural populations of P. trituberculatus have sharply declined due to overfishing and environmental deterioration in China [25]. In aquaculture, swimming crabs usually exhibit low growth rates, poor flesh quality, and weak disease resistance [26]. Among these problems, growth is a priority trait for genetic improvement as it directly affects yield [27]. Therefore, a study to initiate selective breeding programs of swimming crabs using candidate markers and genes for genetic improvement of growth-related traits is necessary.

In the present study, we characterized the Myf6 gene of P. trituberculatus, elucidated its expression pattern, and compared its expression differences in two extreme weight groups. Targeted resequencing was used to screen SNPs of Myf6 and a correlation analysis was carried out to examine the associated SNP loci with growth traits of P. trituberculatus. The results of this study will provide a theoretical basis for further functional studies and the application of Myf6 in the molecular marker-assisted breeding of P. trituberculatus.

Materials and methods

Samples collection and DNA extraction

In our breeding program, a fast-growing swimming crab strain was cultivated using a combination of pedigree breeding and molecular markers (SSR and SNP) in the national swimming crab breeding farm (38°49′ N, 117°64′ E) in Huanghua, Hebei Province, China, resulting in a total of 100 families for selective breeding in 2020. In 2022, a total of 2000 fry samples of a full-sib family from the G3 generation of the above superior strain were randomly selected and placed in the same pond, which was controlled for being in the same developmental cycle and molt period. When sexually mature, 184 individuals were randomly selected as the experimental population in this study. After transporting them back to the laboratory, four growth-related traits were measured as phenotypic data, including full carapace width (FCW), carapace length (CL), body height (BH), and body weight (BW) as described by Liu et al. [28]. All individuals were then placed on ice, dissected for muscle tissue, and preserved in absolute ethyl alcohol at − 20℃. Genomic DNA was extracted from muscle tissue using a marine animal genomic DNA extraction kit (Tiangen, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration and integrity were monitored by a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis. Then, DNA samples were stored at − 20 °C until use.

Total RNA extraction

A total of 30 extremely light and heavy individuals from the full-sib family mentioned above were selected as the slow-growing group (n = 15, mean 78.20 ± 9.46 g) and fast-growing group (n = 15, mean 281.25 ± 20.98 g), respectively. Seven tissues (muscle, heart, testis, ovary, seminal vesicle, gill, and hepatopancreas) were collected and stored in liquid nitrogen for Myf6 gene expression analysis. Total RNA from the samples was isolated using a TRIzol reagent kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA quality and concentration were estimated by 1% agarose gel and NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA), respectively.

Sequence analysis of Myf6

The full-length genomic sequence and cDNA sequence of Myf6 were obtained from the published swimming crab genome (release version ASM1759143v1). Homologous sequences of the mammalian, teleost, and crustaceans were downloaded from the GenBank based on NCBI BLAST searches. The physical and biochemical properties of the encoded proteins were predicted using the ProtParam program (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/). The signal peptide was predicted by SignalP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). NCBI CD-Search program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) was used to predict the protein structural domains. Sequence multiplex analysis was performed using the DNAMAN 6.0 software, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 7.0 software according to the neighbor-joining (NJ) method [29].

Expression analysis of Myf6

After removing genomic DNA using DNase I (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania), extracted total RNA of all samples was diluted to 200 ng/µL, and then used as a template for cDNA synthesis using M-MLV first-strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). qRT-PCR was performed using the ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) to investigate the mRNA expression of Myf6 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was carried out in a final volume of 10 µL, comprising 5 µL 2×SG Green qPCR Mix, 0.2 µL of each primer, 1 µL template cDNA, and 3.6 µL deionized water. PCR amplification was done under the following conditions: initial denaturation of template DNA at 94 °C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. All assays for qPCR assays were performed in triplicate. The expression of the target gene that was relative to the internal reference gene β-actin was calculated based on the 2−ΔΔCT method [30].

SNP identification and genotyping

The full-length genomic sequence of Myf6 was sequenced for SNP identification. The primers used are presented in Table S1. The reaction mixtures of 12 µL contained 6 µL of SYBR qPCR SuperMix Plus (NovoStart, Suzhou, China), 1 µL (1 µM) of each forward and reverse primer, 1.8 µL template cDNA, 0.2 µL ROX Reference Dye, and 2 µL ddH2O. PCR program involved an initial denaturation step of 2 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing temperature (60 °C) for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s and an extension cycle of 5 min at 72 °C. All identified SNPs were aligned to the reference genome of the swimming crab (release version ASM1759143v1) using DNAStar software (http://www.dnastar.com). A nucleotide site with minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.05 was recognized as a putative SNP locus using HaploView 4.2 software (https://www.broadinstitute.org/haploview/haploview).

The obtained SNP loci were genotyped by Shanghai Biowing Applied Biotechnology Co. Ltd. using targeted resequencing by the protocol described by Chen et al. [31]. PopGene 32 software was used to calculate the number of effective alleles (Ne), observed heterozygosity (Ho), expected heterozygosity (He), and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Polymorphism information content (PIC) was calculated by PIC_CALC with the standard of low (PIC < 0.25), medium (0.25 < PIC < 0.5), and high polymorphisms (PIC > 0.5) [32]. Haplotype analysis among SNPs within Myf6 was performed using the Haploview 4.2 program [33]. The associations between SNPs and growth-related traits of P. trituberculatus were performed by TASSEL2.1 [34] with a general linear model (GLM). Benjamin Hochberg’s method was used to calculate the false discovery rate (FDR) for correcting the associated SNP with growth traits [35]. The associations between genotypes of SNPs in Myf6 and growth-related traits were performed using the GLM model of SPSS 22. Additionally, excluding individuals with less than 3 genotypes and those who have not been successfully genotyped. Significant differences among the means of different genotypes were tested using Duncan’s multiple range test in the GLM model with statistical significant (P < 0.05).

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA and t-test were performed using SPSS 22 software for multiple comparisons of relative mRNA expression levels at different tissues and extreme-growth individuals respectively. The results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Summary of growth traits

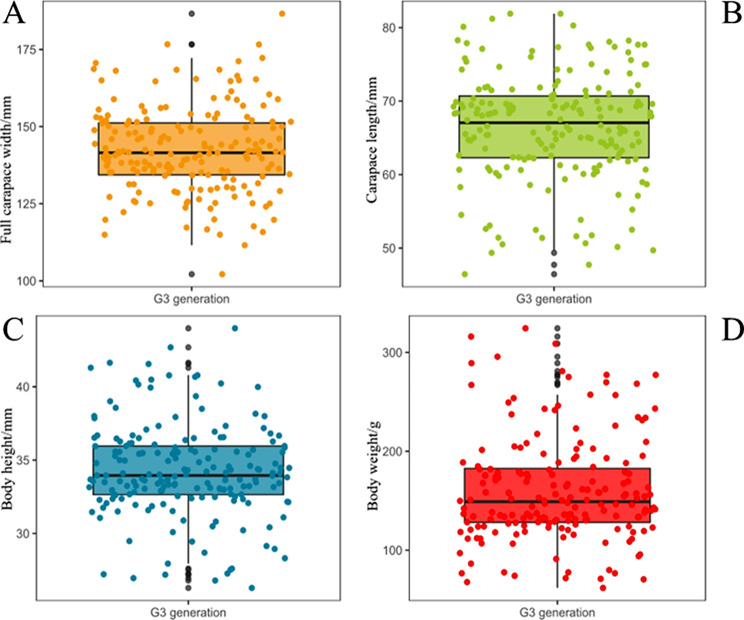

The G3 generation of 184 swimming crabs exhibited a continuous distribution of full carapace width, carapace length, body height, and body weight (Fig. 1). The mean full carapace width was 142.43 ± 13.92 mm with a coefficient of variation (CV) of 9.77%, the mean carapace length was 66.42 ± 7.32 mm with a CV of 11.03%, the mean body height was 34.26 ± 3.18 mm with a CV of 9.28%, and the mean body weight was 160.14 ± 52.89 mm with a CV of 33.03% (Table 1). The four traits exhibited wide phenotypic variation.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of four growth traits in the G3 generation of 184 swimming crabs. (A) Distribution of full carapace width; (B) Distribution of carapace length; (C) Distribution of body height; (D) Distribution of body weight

Table 1.

Summary of growth data for the swimming crab population (n = 184) used for the association analysis

| Traits | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| full carapace width/mm | 102.17 | 186.63 | 142.43 ± 13.92 | 9.77 |

| carapace length/mm | 46.45 | 81.90 | 66.42 ± 7.32 | 11.03 |

| body height/mm | 26.29 | 43.99 | 34.26 ± 3.18 | 9.28 |

| body weight/g | 61.84 | 324.48 | 160.14 ± 52.89 | 33.03 |

Note Min: minimum; Max: maximum; SD: standard deviation; CV: coefficient of variation

Molecular characterization of Myf6

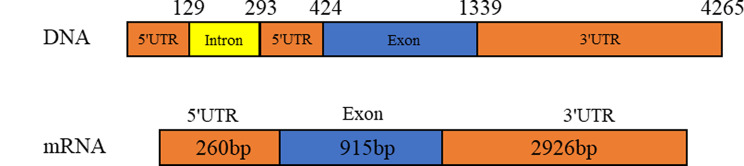

The structure of Myf6 was obtained by comparing genomic DNA with cDNA sequence by NCBI BLAST (Fig. 2). Myf6 gene is located on the 40th Chromosome of P. trituberculatus. The full-length cDNA is 4,101 bp including an open reading frame (ORF) of 915 bp, a 5′UTR of 260 bp, and a 3′UTR of 2,960 bp. The full-length genomic DNA of Myf6 is 4,329 bp, containing one exon (915 bp) and one intron (164 bp). The Myf6 ORF encodes 304 amino acid residues. The theoretical molecular weight and isoelectric point are 33,079.32 and 8.63, respectively; In terms of amino acid composition, the proportion of polar amino acids is higher than that of nonpolar amino acids, and the protein exhibits hydrophilicity. Conservative structure domain prediction showed that the Myf6 protein has a conservative bHLH domain (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Genomic structure and mRNA of Myf6 in swimming crab. The gene contains one exon and one intron. The 3′ and 5′ UTR (untranslated region, orange) and exon encoding the amino acid sequences (blue) are shown relative to their lengths in the cDNA sequences obtained

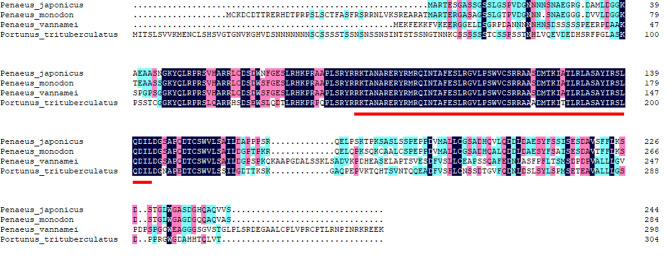

Fig. 3.

Multiple sequence alignments of the amino acid sequences for Myf6 among different crustaceans. The black indicates the same amino acid and the number on the right indicates the amino acid position of Myf6 in the different species. Different colors represent the degree of homology level. Black indicates 100% identity between species, pink indicates ≥ 75% identity, blue indicates ≥ 50% identity, and yellow indicates ≥ 33% identity. The red underline represents the conservative bHLH domain

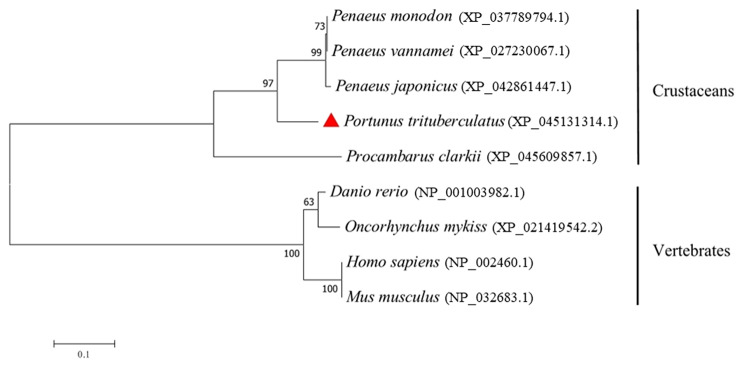

The homologous analysis demonstrated that the eight Myf6 amino acid sequences could be classified into two subgroups (Fig. 4). The Myf6 of P. trituberculatus first clustered with P. vannamei, P. japonicus, and P. monodon, and then with P. clarkia, clustering into a subgroup (crustaceans). Another subgroup included mammalian and teleost (vertebrates). These subgroups indicated that Myf6 shared a high identity with crustaceans and a low identity with vertebrates.

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of Myf6 genes by the neighbor-joining method among different species

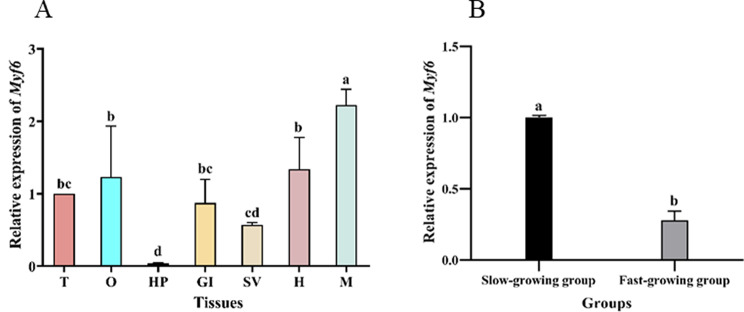

Expression pattern of Myf6

The expression pattern of Myf6 mRNA was detected by qRT-PCR (Fig. 5A). The mRNA expression level of Myf6 was highest in muscle, followed by the heart and ovary. Testis, gill, and seminal vesicle showed lower expression levels. However, the lowest level of Myf6 mRNA was detected in the hepatopancreas. Moreover, the mRNA expression level of Myf6 in muscle tissue of the slow-growing group was significantly higher than that in the fast-growing group (P < 0.05, Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

mRNA expression levels of the Myf6 gene in different tissues (A) and different extreme weight groups (B). T: Testis; O: Ovary; HP: Hepatopancreas; GI: Gill; SV: Seminal vesicle; H: Heart; M: muscle. Bars with different superscripts represent significant differences (P < 0.05)

Polymorphisms of Myf6

After sequencing and sequence alignment, a total of 19 SNP loci were identified (Table 2), including two in introns, five in exons, one in 5′UTR, and eleven in 3′UTR. Among these loci, g.1,188,432 C > T, g.1,188,630 C > T, and g.1,188,720 T > C are synonymous SNPs, and g.1,187,971 C > T that turns Serine into Phenylalanine and g.1,188,616 A > G that turns Asparagine into Serine are non-synonymous SNPs. PopGene 32 software was used to calculate genetic diversity parameters of the identified SNPs with 184 swimming crab individuals. The observed (Ho) and the expected heterozygosity (He) ranged from 0.0054 to 0.6630 (mean: 0.2222) and 0.0054 to 0.4966 (mean: 0.2017), respectively. According to PIC determination criteria, 14 SNPs showed low polymorphism (PIC < 0.25), and 5 SNPs were moderately polymorphic (0.25 < PIC < 0.5). The chi-squared test showed that 14 SNPs fit with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) (P > 0.05) and 5 SNPs deviated significantly from HWE at P < 0.01 levels.

Table 2.

Genetic diversity parameters based on SNP polymorphisms in Myf6 of P. Trituberculatus

| SNP site | Position | Ho | He | HWE | PIC | Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g.1,185,530 G > A | 3’UTR | 0.0241 | 0.0355 | 0.0000 | 0.3682 | |

| g.1,185,597 C > T | 3’UTR | 0.1687 | 0.2119 | 0.0085 | 0.3502 | |

| g.1,185,889 T > C | 3’UTR | 0.0598 | 0.0580 | 0.6760 | 0.3401 | |

| g.1,186,308 C > T | 3’UTR | 0.6576 | 0.4957 | 0.0000 | 0.2720 | |

| g.1,186,400 T > A | 3’UTR | 0.1630 | 0.1498 | 0.2286 | 0.2621 | |

| g.1,186,578 G > C | 3’UTR | 0.0054 | 0.0054 | 0.9705 | 0.2461 | |

| g.1,186,868 A > G | 3’UTR | 0.6630 | 0.4867 | 0.0000 | 0.1664 | |

| g.1,186,958 G > A | 3’UTR | 0.1739 | 0.1588 | 0.1964 | 0.1462 | |

| g.1,187,324 C > T | 3’UTR | 0.0508 | 0.0496 | 0.7285 | 0.1392 | |

| g.1,187,771 T > G | 3’UTR | 0.3187 | 0.3367 | 0.4695 | 0.0905 | |

| g.1,187,834 A > G | 3’UTR | 0.6359 | 0.4996 | 0.0002 | 0.0839 | |

| g.1,187,971 C > T | Exon | 0.0109 | 0.0108 | 0.9409 | 0.0704 | M |

| g.1,188,432 C > T | Exon | 0.2474 | 0.2321 | 0.5161 | 0.0565 | S |

| g.1,188,616 A > G | Exon | 0.3261 | 0.3750 | 0.0768 | 0.0476 | M |

| g.1,188,630 C > T | Exon | 0.0217 | 0.0215 | 0.8815 | 0.0347 | S |

| g.1,188,720 T > C | Exon | 0.3152 | 0.3341 | 0.4442 | 0.0215 | S |

| g.1,188,803 C > T | 5’UTR | 0.0109 | 0.0108 | 0.9409 | 0.0099 | |

| g.1,188,919 C > T | Intron | 0.2935 | 0.2873 | 0.7718 | 0.0099 | |

| g.1,189,024 C > A | Intron | 0.0761 | 0.0732 | 0.5916 | 0.0060 |

Ho: observed heterozygosity, He: expected heterozygosity, HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, PIC: Polymorphism information content, M: non-synonymous locus, S: synonymous locus

Association analysis between SNPs and growth-related traits

Association analysis indicated five SNPs associated with growth traits of P. trituberculatus (P < 0.05, FDR < 0.05), and the details were listed in Table 3. The four growth traits in the CT genotype of g.1,187,324 C > T were significantly larger than those in the CC genotype (P < 0.05). At the g.1,187,834 A > G locus, the AA and GG genotypes showed significant differences in all of the growth traits measured, while no differences were observed between the AG and GG genotypes. At the g.1,188,616 A > G locus, the AG and GG genotypes showed significant differences in FCW traits, with GG exhibiting superior traits. Similarly, the FCW trait for the TT genotype was superior to the CC and CT genotypes at the g.1,188,919 C > T locus. When the CC genotype was compared with the AC genotype at the g.1,189,024 C > A locus, only FCW and BW traits were significantly different (P < 0.05). Also, g.1,187,324 C > T and g.1,187,834 A > G showed high phenotypic variance explained (PVE) and effect values among the four growth-related traits (Table S2).

Table 3.

Genotypes of the Myf6 SNPs in swimming crab population and their associations with growth traits

| SNPs | Genotype | Number | Body weight (g) | Carapace length (mm) | Full carapace width (mm) | Body height (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g.1,187,324 C > T | CC | 168 | 154.63 ± 48.94a | 65.75 ± 7.15a | 141.19 ± 13.52a | 33.93 ± 3.01a |

| CT | 9 | 200.58 ± 75.91b | 72.30 ± 7.04b | 151.90 ± 14.18b | 36.99 ± 3.36b | |

| g.1,187,834 A > G | AA | 31 | 141.04 ± 60.41a | 63.10 ± 9.10a | 136.19 ± 15.82a | 33.02 ± 3.96a |

| AG | 117 | 161.85 ± 44.96ab | 67.03 ± 6.03b | 143.69 ± 12.07b | 34.44 ± 2.64b | |

| GG | 36 | 171.0 ± 66.51b | 67.27 ± 8.88b | 142.43 ± 13.96b | 34.73 ± 3.86b | |

| g.1,188,616 A > G | AA | 16 | 166.95 ± 69.01 | 67.27 ± 8.90 | 142.85 ± 17.61ab | 34.63 ± 3.80 |

| AG | 60 | 150.12 ± 57.33 | 64.87 ± 7.46 | 139.03 ± 14.68a | 33.61 ± 3.58 | |

| GG | 108 | 164.70 ± 47.40 | 67.15 ± 6.95 | 144.25 ± 12.68b | 34.56 ± 2.82 | |

| g.1,188,919 C > T | CC | 116 | 162.08 ± 47.18 | 66.95 ± 6.95 | 143.44 ± 12.75a | 34.40 ± 2.85 |

| CT | 58 | 152.43 ± 57.24 | 65.21 ± 7.33 | 139.67 ± 14.64a | 33.83 ± 3.52 | |

| TT | 10 | 182.34 ± 83.75 | 67.17 ± 11.18 | 146.70 ± 21.07b | 35.10 ± 4.69 | |

| g.1,189,024 C > A | AC | 14 | 133.01 ± 24.25a | 65.64 ± 5.95 | 134.15 ± 7.54a | 32.91 ± 2.26 |

| CC | 170 | 162.37 ± 54.17b | 66.47 ± 7.46 | 143.11 ± 14.16b | 34.37 ± 3.23 |

Note Mean values with the different letters within a column are significantly different (P < 0.05)

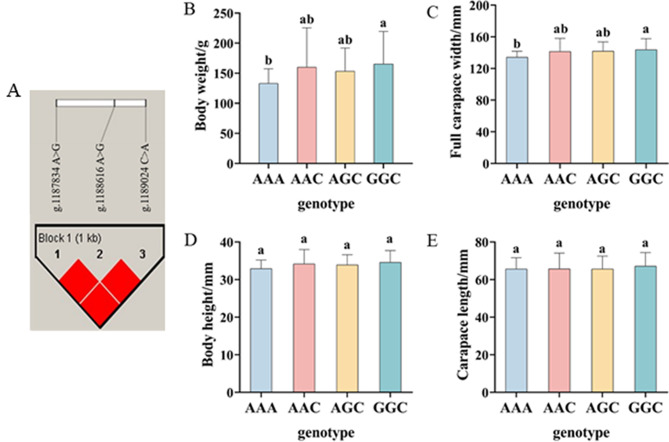

Association analyses were further performed between combined genotypes of two loci (g.1187324 C > T and g.1187834 A > G) and four growth-related traits of P. trituberculatus, and five diplotypes (D1-D5) were formed (Table 4). For the mean values of all growth traits, D5 > D4 > D2 > D3 > D1. In growth traits of BW, CL, and BH, D5 was significantly higher than D1, D2, and D3 (P < 0.05). D5 was significantly higher than D1 (P < 0.05) only in the FCW trait. The results suggested that D5 was the genotype with the best performance and D1 was the worst among the five diplotypes. In addition, haplotype analysis was carried out in the five significant SNPs, which detected one haplotype block including g.1,187,834 A > G, g.1,188,616 A > G, and g.1,189,024 C > A (Fig. 6A). Four haplotypes (AAA, AAC, AGC, and GGC) in Block 1 were found by conducting haplotype association analysis for four growth traits of P. trituberculatus. The GGC haplotype had a greater average BW (165.34 ± 53.98 g) and FCW (143.69 ± 13.93 mm) than those in the AAA haplotype (BW: 133.01 ± 24.25 g, FCW: 134.15 ± 7.54 mm; P < 0.05) (Fig. 6B and C). However, differences among the four haplotypes were not significant in CL and BH traits (Fig. 6D and E).

Table 4.

Association of diplotype of g.1,187,324 C > T and g.1,187,834 A > G with growth traits in P. Trituberculatus

| Diplotype | Genotype | Number | Body weight (g) | Carapace length (mm) | Full carapace width (mm) | Body height (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | CC | AA | 31 | 141.04 ± 60.41a | 63.10 ± 9.10a | 136.19 ± 15.82a | 33.02 ± 3.96a |

| D2 | CC | AG | 109 | 158.82 ± 41.93a | 66.68 ± 5.93b | 142.98 ± 11.81ab | 34.27 ± 2.53b |

| D3 | CC | GG | 28 | 153.35 ± 58.72a | 65.08 ± 8.48ab | 139.80 ± 15.82ab | 33.59 ± 3.38ab |

| D4 | CT | AG | 4 | 181.13 ± 91.17ab | 70.20 ± 7.45bc | 151.68 ± 17.21ab | 36.32 ± 4.25bc |

| D5 | CT | GG | 5 | 216.14 ± 67.89b | 73.98 ± 7.05c | 152.07 ± 13.42b | 37.54 ± 2.87c |

Note Mean values with the different letters within a column are significantly different (P < 0.05)

Fig. 6.

Linkage disequilibrium analysis for the three SNPs in Myf6 significantly associated with growth traits of swimming crab. A represents the haploblock structure of the three SNPs. B, C, D, and E represent the growth traits of different genotypes, respectively. Bars with different superscripts indicate significant difference (P < 0.05)

Discussion

SNP markers potentially controlling the growth traits always occur within candidate genes, so investigating the association between polymorphism in candidate genes and the growth traits is an effective method to identify SNPs that affect quantitative polygenic traits [36, 37]. A large number of candidate genes have been identified to obtain SNP loci related to the growth of aquatic animals, such as the growth hormone (GH) in Oreochromis niloticus [38], myosin heavy chains (MyHCs) in Patinopecten yessoensis [39], and myostatin in Exopalaemon carinicauda [7]. As an important growth-related gene, Myf6 affects the growth and differentiation of muscle and exerts pivotal roles in improving the meat production and meat quality of aquatic animals [40–42]. Therefore, it is of great significance to study the function and genetic variation of the Myf6 gene and to screen SNP loci for molecular marker-assisted breeding in aquaculture.

It has been reported that the deletion of the Myf6 gene inhibited the formation of muscle fibers in mice, leading to abnormal development and death at birth [43]. In this study, the Myf6 gene was widely expressed in various tissues of P. trituberculatus, but its expression level was highest in muscle. This phenomenon commonly occurs in livestock and fish [42, 44, 45]. However, the expression level of the Myf6 gene in the slow-growing group was significantly higher than that in the fast-growing group (P < 0.05). A similar result was found in Cyprinus carpio that the Myf6 gene expressed weaker in larger-size fish (500 g) than in smaller-size ones (50 ~ 60 g, 120 ~ 130 g; P < 0.01) [40]. The findings indicated the negative regulation of the Myf6 gene on the growth of aquatic animals. This phenomenon may be attributed to the regulation of Myf6 gene expression. In a fast-growing group, there may be a mechanism or signaling pathway that can downregulate the expression of the Myf6 gene. This regulation is aimed at balancing muscle growth with other biological processes such as energy metabolism and cell proliferation, ensuring the growth and development of the organism. Additionally, the genetic redundancy may also be the explanation [46]. There may be other genes with similar functions to the Myf6 gene in the fast-growing group, whose increased expression compensates for the downregulation of the original gene expression. This redundancy makes the expression of the Myf6 gene less important in the fast-growing group. To more accurately explain this phenomenon, it is necessary to further explore the regulatory mechanism of Myf6 gene expression through methods such as gene knockout, expression profile analysis, and protein-protein interaction research.

Association studies between polymorphism in the Myf6 gene and the growth traits of aquatic animals have been conducted. In O. niloticus, one significant SNP (G137T) in Myf6 exon1 was found to be associated with multiple growth traits (P < 0.05) [47]. However, no significant differences were observed between SNP loci of the Myf6 gene and the growth traits of Takifugu rubripes due to insufficient sample size [48]. To date, the characterization of the Myf6 gene in crustaceans has not been reported. This study first identified SNPs in the Myf6 gene and investigated their association with growth traits in P. trituberculatus, which can aid in the identification of growth-related SNPs. Results indicated that g.1,187,324 C > T and g.1,187,834 A > G in 3’UTR of the Myf6 gene showed significant association with four growth traits of P. trituberculatus, suggesting multigenic effect and pleiotropism.

It has been shown that 3′UTR contains plenty of regulatory elements related to mRNA stability, translation, localization, and mediation of protein-protein interactions, leading to a dominant role in the regulation of gene expression and affecting individual phenotypes by affecting the binding of target genes to miRNA [49–51]. Previous studies in fish species, such as Pangasianodon hypophthalmus [52] and Hypophthalmichthys nobilis [53], have identified SNPs in the 3′UTR of growth-related genes that are significantly associated with growth traits. These studies indicated that mutations in the 3′UTR of candidate genes have important effects on the growth traits of aquatic animals.

Association studies suggest interactions between growth-related SNPs, emphasizing the need for haplotype analysis to improve the power and robustness of association studies [54]. The haplotypes H1/H4 and H1/H5 in the GHRH gene of Ictalurus punctatus show the highest body mass and body length, aiding marker-assisted breeding of growth traits of I. punctatus [55]. In H. nobilis, the CC-CC-GG genotype of the FST gene is associated with higher body weight, indicating its potential in breeding programs [56]. This study identified haplotype GGC of three SNPs (g.1187834 A > G, g.1188616 A > G, and g.1189024 C > A) as superior for BW and FCW traits in P. trituberculatus. It is noteworthy that AG and GG genotypes of g.1,187,834 A > G were found in 83% of high-weight crabs. The high PVE and effect values reveal that g.1,187,834 A > G locus has a positive impact on the growth traits of P. trituberculatus. Moreover, the diplotype CT-GG composed of g.1,187,324 C > T and g.1,187,834 A > G was significantly better than other diplotypes in the phenotype values of BW, BH, and CL traits of P. trituberculatus, emphasizing its important significance in the marker-assisted selection of P. trituberculatus.

Conclusion

In this study, we first characterized the Myf6 gene in crustaceans and performed the association analysis between the polymorphism of Myf6 and the growth traits of P. trituberculatus. Expression analysis revealed high expression of Myf6 in muscle. g.1,187,834 A > G locus located in the 3′UTR region of Myf6 was identified, which showed significant association with four growth-related traits of P. trituberculatus. The diplotype D5 (CT-GG) is composed of g.1,187,324 C > T and g.1,187,834 A > G and the GGC haplotype is composed of g.1,187,834 A > G, g.1,188,616 A > G, and g.1,189,024 C > A exhibited superior growth traits. These results suggested that Myf6 might play an important regulatory role in the growth of P. trituberculatus. As a growth-related marker, however, g. 1,187,834 A > g is identified by a single population and cannot be directly used for molecular marker-assisted breeding. More families (e.g. hybrid, full-sibling, and half-sibling families) and sample sizes should be used to verify its effectiveness. Collectively, this study not only provides new insights into understanding the regulatory mechanism of growth but also provides candidate markers for the genetic improvement of P. trituberculatus. Hence, Myf6 may have great potential in swimming crab breeding programs and merit further research.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Baohua Duan and Weibiao Liu: Writing-original draft, Formal analysis, Investigation. Chen Zhang: Data curation, Formal analysis. Tongxu Kang: Data curation, Formal analysis. Haifu Wan: Methodology. Shumei Mu and Yueqiang Guan: Validation. Zejian Li, Yang Tian and Yuqin Ren: Resources. Xianjiang Kang: Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing-review & editing.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (C2016201249); Hebei Natural Science Foundation (C2022201042); Science and Technology Innovation Project of Modern Seed Industry (21326307D); Hebei Province innovation ability Enhancement Plan Project (225676109 H); Institute of Life Science and Green Development (Hebei University), and Innovation Center for Bioengineering and Biotechnology of Hebei Province.

Data availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the Additional Files. The genotypes and phenotypes are available in Supplementary Data Sheets S1 and S2.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethical Committee of Hebei University Experimental Animal Center (SYXK2022-009). To ease pain and facilitate handling, the experimental samples were placed on ice for dissection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Baohua Duan and Weibiao Liu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Zhou Y, Fu HC, Wang YY, Huang HZ. Genome-wide association study reveals growth-related SNPs and candidate genes in mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi). Aquaculture. 2022;550:737879. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao JC, He ZH, Chen XY, Huang YY, Xie JJ, Qin X, Ni ZT, Sun CB. Growth trait gene analysis of kuruma shrimp (Marsupenaeus japonicus) by transcriptome study. Comp Biochem Physiol Part D. 2021;40:100874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang QC, Yu Y, Zhang Q, Zhang XJ, Yuan JB, Huang H, Xiang JH, Li FH. A novel candidate gene associated with body weight in the pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Front Genet. 2019;10:520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou ZX, Han KH, Wu YD, Bai HQ, Ke QZ, Pu F, Wang YL, Xu P. Genome-wide association study of growth and body-shape-related traits in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) using ddRAD sequencing. Mar Biotechnol. 2019;21:655–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yue GH, Ma KY, Xia JH. Status of conventional and molecular breeding of salinity-tolerant tilapia. Rev Aquacult. 2023;16(1):271–86. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang K, Han M, Liu YX, Lin XH, Liu XM, Zhu H, He Y, Zhang QQ, Liu JX. Whole-genome resequencing from bulked-segregant analysis reveals gene set based association analyses for the Vibrio anguillarum resistance of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019;88:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang JJ, Li JT, Ge QQ, Li J. A potential negative regulation of myostatin in muscle growth during the intermolt stage in Exopalaemon carinicauda. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2021;314:113902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hua JX, Zhong CY, Chen WH, Fu JJ, Wang J, Wang QC, Zhu GY, Li Y, Tao YF, Zhang MY, Dong YL, Lu SQ, Liu WT, Qiang J. Single nucleotide polymorphism SNP19140160 A > C is a potential breeding locus for fast-growth largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). BMC Genomics. 2024;25:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan BH, Kang TX, Wan HF, Mu SM, Guan YQ, Liu WB, Li ZJ, Tian Y, Ren YQ, Kang XJ. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the SIF gene and their association with growth traits in swimming crab (Portunus Trituberculatus). Aquacult Rep. 2023;33:101792. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang QC, Yu Y, Zhang Q, Luo Z, Zhang XJ, Xiang JH, Li FH. The polymorphism of LvMMD2 and its association with growth traits in Litopenaeus vannamei. Mar Biotechnol. 2020;22:564–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan SG, Xu YH, Liu BS, He WY, Zhang B, Su JQ, Yu DH. Molecular characterization and expression analysis of the myostatin gene and its association with growth traits in noble scallop (Chlamys Nobilis). Comp Biochem Physiol Part B. 2017;212:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sawayama E. Polymorphisms and haplotypes of the myostatin gene associated with growth in juvenile red sea bream Pagrus major. Aquacult Res. 2020;51(10):4238–44. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu GW, Chen JM, Wang SQ, Cheng ZB, Wu YJ, Rong H, Jia JJ, Fan YY. The polymorphisms of myogenic determinant factor Myf6 gene and its association with production traits of domestic animal. Acta Ecologae Animalis Domastici. 2013;34(04):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun T, Bober E, Busechhausen-Denker G, Kohtz S, Grzeschik HK, Arnold HH, Kotz S. Differential expression of myogenic determination genes in muscle cells: possible autoactivation by the MYF gene products. EMBO. 1989;8(12):3617–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naidu PS, Ludolph DC, To RQ, Hinterberger TJ, Konieczny SF. Myogenin and MEF2 function synergistically to activate the MRF4 promoter during myogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(5):2707–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cupelli L, Renault B, Leblanc-Straceski J, Banks A, Ward D, Kucherlapati RS, Krauter K. Assignment of the human myogenic factors 5 and 6 (MYF5, Myf6) gene cluster to 12q21 by in situ hybridization and physical mapping of the locus between D12S350 and D12S106. Cytogenet Genome Res. 1996;72(2–3):250–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun T, Bober E, Winter B, Rosenthal N, Arnold HH. Myf-6, a new member of the human gene family of myogenic determination factors: evidence for a gene cluster on chromosome 12. EMBO. 1990;9(3):821–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yun K, Wold B. Skeletal muscle determination and differentiation: story of a core regulatory network and its context. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8(6):877–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han W, Qi M, Ye K, He QW, Yekefenhazi D, Xu DD, Han F, Li WB. Genome-wide association study for growth traits with 1066 individuals in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Front Mol Biosci. 2024;11:1443522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinits Y, Osborn DPS, Carvajal JJ. Mrf4 (myf6) is dynamically expressed in differentiated zebrafish skeletal muscle. Gene Expr Patterns. 2007;7:738–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song Y, Zhang SB, Shen YJ. Clong and tissue expression of Myf6 gene in nubian goat. China Anim Husb Veterinary Med. 2021;48:4084–93. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu M, Ge SS, Bhandar S, Fan CL, Jiao Y, Gai CL, Wang YH, Liu HJ. Genome characterization and comparative analysis among three swimming crab species. Front Mar Sci. 2022;9:895119. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Global capture production 1950–2019. 2021.

- 24.Lv JJ, Gao BQ, Liu P, Li J, Meng XL. Linkage mapping aided by de novo genome and transcriptome assembly in Portunus Trituberculatus: applications in growth-related QTL and gene identification. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lv JJ, Liu P, Gao BQ, Wang Y, Wang Z, Chen P, Li J. Transcriptome analysis of the Portunus trituberculatus: De novo assembly, growth-related gene identification and marker discovery. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao BQ, Liu P, Li J, Wang QY, Li XP. Genetic diversity of different populations and improved growth in the F1 hybrids in the swimming crab (Portunus Trituberculatus). Genet Mol Res. 2014;13(4):10454–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guan WZ, Qiu GF, Liu F. Transcriptome analysis of the growth performance of hybrid mandarin fish after food conversion. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0240308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L, Li J, Liu P. Identification of quantitative trait loci for growth-related traits in the swimming crab Portunus Trituberculatus. Aquacult Res. 2015;46:850–60. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method - a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4(4):406–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ren XY, Yu X, Gao BQ, Li J, Liu P. iTRAQ-based identification of differentially expressed proteins related to growth in the swimming crab, Portunus Trituberculatus. Aquacult Res. 2017;48(6):3257–67. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen K, Zhou YX, Li K, Qi LX, Zhang QF, Wang MC, Xiao JH. A novel three-round multiplex PCR for SNP genotyping with next generation sequencing. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2016;408:4371–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen QY, Yu WM, Hao RJ, Yang JM, Yang CY, Deng YW, Liao YS. Molecular characterization and SNPs association with growth-related traits of myosin heavy chains from the pearl oyster Pinctada fucata martensii. Aquacult Res. 2022;53(7):2874–85. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradbury PJ, Zhang Z, Kroon DE, Casstevens TM, Ramdoss Y, Buckler ES. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(19):2633–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benjamini YH, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate-a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc: Ser B (Methodol). 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran TTH, Nguyen HT, Le BTN, Tran PH, Nguyen SV, Kim OTP. Characterization of single nucleotide polymorphism in IGF1 and IGF1R genes associated with growth traits in striped catfish (Pangasianodon Hypophthalmus Sauvage, 1878). Aquaculture. 2021;538:736542. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen YB, Ma KY, Zhu Q, Xu XY, Li JL. Transcriptomic analysis reveals growth-related genes in juvenile grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idella. Aquacult Fish. 2022;7(6):610–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaser S, Dias M, Lago A, Neto R, Hilsdorf A. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the growth hormone gene of Oreochromis niloticus and their association with growth performance. Aquacult Res. 2017;48(12):5835–45. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang YM, Zhou LQ, Yu T, Zheng YX, Wu B, Liu ZH, Sun XJ. Molecular characterization of myosin heavy chain and its involvement in muscle growth and development in the Yesso scallop Patinopecten Yessoensis. Aquaculture. 2023;563:739027. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin YQ, Ji H, Zheng YC, Qiu X, Wang SX, Liu MQ. Cloning and expression analysis of Myf-6 gene of carp (Cyprinus carpio). Acta Agric Boreali-Occident Sin. 2010;19(09):16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li HH, Xu YQ, Liu XY, Liu ZX, Wang KZ, Chu WY, Zhang JS, Ding ZK. Molecular cloning of myogenic regulatory factor 4 gene (mrf4) and its expression in adult and embryonic mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi). J Hunan Agricultural Univ (Natural Sciences). 2013;39(06):631–5. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang YP, Shao F, Zheng HM, Lu XY, Xu JR, Gu ZL. Cloning and tissue expression analyses of MRF4 gene in Trachidermus fasciatus. J Nanjing Norm Univ Nat Sci Ed. 2013;36(03):108–15. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bober E, Lyons GE, Braun T, Cossu G, Buckingham M, Arnold HH. The muscle regulatory gene, Myf-6, has a biphasic pattern of expression during early mouse development. J Cell Biol. 1991;113(6):1255–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao T, Shi LG, Zhou HL, Zhang LL, Hou GY. Expression of Myf4 and Myf6 in different tissues of Wuzhishan Pig. Genomics Appl Biol. 2012;31(5):436–40. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi B, Sun RR, Liu XZ, Zhang ZR, Xu YJ, Jiang Y, Wang B. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression profile of Myf5 and Myf6 during growth and development in the Seriola lalandi. J Ocean Univ China. 2021;20(06):1597–605. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gatherer D. Gene knockouts and murine development: (gene knockout/gene targeting/Mus/mammalian embryology/genetic redundancy). Dev Growth Differ. 1993;35(4):365–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zou GW, Zhu YY, Liang HW, Li Z. Association of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and myogenic factor 6 genes with growth traits in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquacult Int. 2015;23:1217–25. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu HL. Heritability estimating of growth traits and SNPs analysis of three candidate genes in Takifugu rubripes. Dalian Ocean University, Thesis for the Degree of Master (In Chinese). 2015.

- 49.Baev V, Daskalova E, Minkov I. Computational identification of novel microRNA homologs in the chimpanzee genome. Comput Biol Chem. 2009;33(1):62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andreassen R, Lunner S, Hoyheim B. Targeted SNP discovery in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) genes using a 3’UTR-primed SNP detection approach. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mayr C. What are 3′UTRs doing ? Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Jiang LS, Ruan ZH, Lu ZQ, Li YF, Luo YY, Zhang XQ, Liu WS. 20. Novel SNPs in the 3′UTR region of GHRb gene associated with growth traits in striped catfish (Pangasianodon Hypophthalmus), a valuable aquaculture species. Fishes. 2022;7(5):230. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang JR, Yu XM, Chen G, Zhang YF, Tong JG. Molecular characterization of slc5a6a and its association with growth and body conformation in bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis). Aquacult Rep. 2022;27:101394. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang SY, Li X, Chen XH, Pan JL, Wang MH, Zhong LQ, Qin Q, Bian WJ. Significant associations between prolactin gene polymorphisms and growth traits in the channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus Rafinesque, 1818) core breeding population. Meta Gene. 2019;19:32–6. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang SY, Zhong LQ, Qin Q, Wang MH, Pan JL, Chen XH, Bian WJ. Three SNPs polymorphism of growth hormone-releasing hormone gene (GHRH) and association analysis with growth traits in channel catfish. Acta Hydrobiol Sin. 2016;40(5):886–93. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pang MX, Tong JG, Yu XM, Fu BD, Zhou Y. Molecular cloning, expression pattern of follistatin gene and association analysis with growth traits in bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis). Comp Biochem Physiol Part B. 2018;218:44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the Additional Files. The genotypes and phenotypes are available in Supplementary Data Sheets S1 and S2.