Abstract

Background

Short fiber-reinforced composites (SFRCs) are restorative materials for large cavities claimed to effectively resist crack propagation. This study aimed to compare the mechanical properties and physical characteristics of five commercially available SFRCS (Alert, Fibrafill Flow, Fibrafill Dentin, everX Flow, and everX Posterior) against a conventional particulate-filled composite (PFC, Essentia Universal).

Methods

The following characteristics were evaluated in accordance with ISO standards: flexural strength and modulus and fracture toughness. FTIR-spectrometry was used to calculate the degree of monomer conversion (DC%). The two-body wear test was performed in a ball-on-flat configuration using a chewing simulator with 15,000 cycles. A non-contact 3D optical profilometer was utilized to measure wear depth. The tensilometer method was used to quantify polymerization shrinkage-stress. Posterior composite crowns (n = 8) were made and quasi-statically loaded until fracture. The microstructure of the SFRCs were assessed using scanning electron microscopy. ANOVA was applied to statistically interpret the results, and then the post hoc Tukey’s analysis was performed.

Results

Among the evaluated composites, SFRC (everX Flow) had the lowermost wear depth (20.4 μm) and uppermost fracture toughness (2.8 MPa m1/2) values (p < 0.05). Fibrafill Flow (92 MPa) and Fibrafill Dentin (98 MPa) showed the lowest flexural strength values (p < 0.05). The used SFRCs exhibited equivalent values (p > 0.05) of shrinkage stress, except for everX Flow which had the highest value (5.3 MPa). everX Flow composite crowns presented significantly greater fracture resistance (3870 ± 260 N) (p < 0.05) than that of the other SFRCs tested.

Conclusion

Significant differences were found between the investigated characteristics of different commercially available SFRCs. It is noteworthy that certain SFRCs exhibited behavior comparable to that of conventional PFC, while others demonstrated superior performance.

Keywords: Composite resins, Polymerization, Physical characteristics

Introduction

Nowadays the direct use of particulate-filled or conventional composite (PFC) is a common conservative and economic approach to restore missing tooth structures. They benefit from having a natural shade, cost less than indirect cast gold and ceramic restorations, and can adhere to enamel and dentin through bonding procedures [1]. Patients’ and clinicians’ demands for natural esthetics have increased, which has resulted in the increased use of composites even in posterior teeth, where significant loading challenges arise during function [1–3]. Their application has expanded to include extra-coronal restorations as well as posterior intra-coronal restorations [2].

To withstand mechanical challenges during function, modification of filler particle morphology and size led to enhanced mechanical properties [1]. However, the literature shows that modern PFC composites still have drawbacks when used in large restorations due to their lack of toughness [4]. Owing to these limitations, there is ongoing debate regarding applying PFC composites in significant high load-bearing situations, like direct posterior restorations in weakened coronal cavities or core build-ups [5]. The demand to enhance restorative composite has resulted in growing interest into strengthening methods. Various methods have been proposed to maintain the residual enamel and dentin structures and enhance the lifespan of large composite restorations [5–7]. Among them the use of discontinuous or short fiber-reinforced composites (SFRCs) to replace dentin and conventional PFC to replace enamel, known as biomimetic restorative approach [8, 9]. High fracture toughness restorative materials are in high demand because they are less likely to fracture and be at risk for crack propagation. Many authors have stated that a SFRC has substantially improved mechanical features, especially in the context of fracture toughness than PFC composites [8–12]. According to literature, the mechanical characteristic that explains the brittle material´s resistance to the catastrophic flaws propagation under an applied load is fracture toughness, and hence, it reflects the material’s damage tolerance [13]. As a result, an essential factor in determining the durability of restorative dental materials is their fracture toughness [13].

Many manufacturers have developed SFRCs with the goal of overcoming the drawbacks of conventional PFC. Comparative investigations, however, revealed that industrial SFRCs have various characteristics, components, and enhancing capability [14, 15]. Several SFRC properties are highly impacted by different geometrical elements like fiber length, size, loading, alignment, and bonding to the polymer matrix [16]. Recent research has revealed that SFRCs that contains micrometre and millimetre scales fibers (everX Posterior and everX Flow; GC Corporation) had much greater fracture toughness and strengthening capabilities than other commercial dental composites [17–20].

A new type of SFRC (Fibrafill Flow & Fibrafill Dentin, ADM, Czech Republic) was launched in 2022 claiming to be a solution for PFC weakness and substitution of dentin, with the promise of unique mechanical properties, particularly fracture toughness. The choice of the appropriate materials to obtain the greatest results is frequently uncertain for clinicians due to the fast development of newer materials on the market. Consequently, laboratory or preclinical research helps to categorize these new materials’ mechanical and physical performance. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the mechanical properties and physical characteristics of five commercially available SFRCS (Alert, Fibrafill Flow, Fibrafill Dentin, everX Flow, and everX Posterior) against a conventional PFC (Essentia Universal, GC Corporation). The null hypothesis was that the material type will have no effect on the tested properties of SFRCs.

Materials and methods

Table 1 includes a list of conventional PFC and SFRCs employed in the study. All composites were handled in accordance with the manufacturers’ suggested procedures. This involved complying with the recommended application methods, including layer thickness and curing protocols. The methods for materials testing and sample size selection were consistent with those used in earlier studies [14, 15, 21].

Table 1.

The composition of the utilized PFC and SFRCs

| Product | Manufacturer | Character | Composition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essentia Universal | GC Corp, Tokyo, Japan | Packable (PFC) | UDMA, BisEMA, BisGMA, TEGDMA, Bis-MEPP, Prepolymerized silica and barium glass 81 wt% | |||

| Alert | Jeneric/Pentron, Wallingford, CT, USA | Packable (SFRC) | Bis-GMA, UDMA, TEGDMA, THFMA.Silica and micrometer scale glass fiber 84 wt%, 62 vol% | |||

| Fibrafill Flow | ADM, Czech Republic | Flowable (SFRC) | Bis-EMA, Bis-GMA, UDMA, TEGDMA, HEMA. Silane treated silica particles (< 60 wt%) and fibers (< 10 wt%) | |||

| Fibrafill Dentin | ADM, | Packable (SFRC) | Bis-EMA, Bis-GMA, UDMA, TEGDMA, HEMA. Silane treated silica particles (< 80 wt%) and fibers (< 10 wt%) | |||

| everX Flow | GC Corp, | Flowable (SFRC) | Bis-EMA, TEGDMA, UDMA, micrometer scale glass fiber filler, Barium glass 70 wt%, 46 vol% | |||

| everX Posteior | GC Corp, | Packable (SFRC) | Bis-GMA, PMMA, TEGDMA, millimetre scale glass fiber filler, Barium glass 76 wt%, 57 vol% | |||

Bis-GMA bisphenol-A-glycidyl dimethacrylate, UDMA urethane dimethacrylate, TEGDMA triethylene glycol dimethacrylate, THFMA tetrahydrofurfuryl-2-methacrylate, Bis-EMA Ethoxylated bisphenol-A-dimethacrylate, Bis-MEPP Bis (p-methacryloxy (ethoxy)1–2 phenyl)-propane, HEMA 2 hydroxyethyl methacrylate, PMMA polymethylmethacrylate, wt% weight%, vol% volume percentage

Mechanical tests

Specimens of specific dimension (2 × 2 × 25 mm3) were prepared for three-point bending test from all evaluated composites. By using a half-split stainless steel mold and transparent Mylar sheets, bar-shaped specimens were prepared. Composite Light curing of composite was performed by a hand light-curing unit (Elipar TM S10, 3 M ESPE, Germany) for a duration of 20 s in five different parts through metal molds on both sides. The curing device’s light-tip was 1 mm away from the composite. The light’s intensity was 1600fmW/cm2, with a wavelength ranged from 400 to 480 nm (Marc Resin Calibrator, BlueLight Analytics Inc., Canada). Before testing, the specimens of each group (n = 8) were kept dry for two days in an incubator (37 °C). According to ISO 4049, a three-point bending test was performed (test span: 20 mm, crosshead speed: 1 mm/min, indenter: 2 mm diameter, load cell: 2500 N). Using a material-testing machine (model LRX, Lloyd Instruments Ltd, Fareham, England) all specimens were loaded, and PC-computer software was used to record the load-deflection curves (Nexygen 4.0, Lloyd Instruments Ltd, Fareham, England).

Flexural strength (ơf) as well as flexural modulus (Ef) were measured according to equations:

Where Fm is the load applied (N) at the maximum point of the load-extension curve, I is the length of span (20 mm), b is the test specimens’ width and h represents the test specimens’ thickness. S is the stiffness (N/m) S = F/d where d represents the deflection that corresponds to load F at a particular point along the straight-line portion of the trace.

To assess the fracture toughness, single-edge notched beam specimens of specific dimension (2.5 × 5 × 25 mm3) were manufactured using an adaptation of the ISO 20795-2 standard procedure (ASTM 2005). The use of a specially constructed stainless steel split mold allowed for force-free specimen removal. A precisely designed slot that extended to the mold’s midpoint was fabricated in the center, Enabling the potential for the crack length (x) to be precisely half of the height of the specimen to achieve optimization. Tested composites were placed into the mold over the glass slide and Mylar strips used for coverage. Before polymerization, a straight-edged steel blade was inserted into the prepared slot to create a sharp crack that located exactly in the center. Light polymerization was performed in the same manner as three-point bending specimens. Each specimen was additionally polymerized on both sides when it was removed from the mold. Specimens from each group (n = 6) were kept dry for two days (37 °C). In three-point bending mode, all specimens were loaded as previously mentioned using the universal testing machine. Then, by using the following Equation, fracture toughness was assessed:

Where P represents the highest load in Newton (N), L represents the length of span (20 mm), B represents thickness of specimen (mm), W is the test specimens’ width (depth) in mm. x represents a geometrical function dependent on a/W, and a represents the length of crack in mm.

Degree of monomer conversion

Fourier transform infrared-spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed using an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory (Spectrum One, Perkin-Elmer, Beaconsfield, Bucks, UK) for the quantification of carbon-carbon double bond conversion (DC%) both pre- and post-photoinitiation of the polymerization process. The assessment was conducted within a mold with dimensions of 1.5 mm in thickness and 4.5 mm in diameter, encompassing the analysis of PFC and SFRC composite materials. The initial step involved the measurement of the spectrum of the non-polymerized specimen. Subsequently, the composite underwent polymerization by employing a manual light-curing unit (Elipar TM S10), with irradiation conducted through an upper glass slide for a duration of 40 s. Following the irradiation process, the FTIR spectrum of the specimen was subjected to scanning. Then, DC% was measured from the aliphatic C = C peak at 1638 cm‾1 and normalized against the aromatic C = C peak at 1608 cm‾1 following this formula:

Where the C aliphatic is the absorption peak at 1638 cm–1 of the polymerized specimen, C aromatic the reference peak of the polymerized specimen. U aliphatic represents absorption peak at 1638 cm–1 of the unpolymerized specimen, and U aromatic is the reference peak of the unpolymerized specimen. Six trials were run for each SFRC composite.

Two-body wear

The two-body wear test was applied according to previous studies [14, 15] to demonstrate the wear resistance of each composite. Two polished (#4000-grit papers) specimens (20 mm length x 10 mm width x 3 mm depth) of each composite were prepared in acrylic resin block. All specimens were immersed in distilled water at a temperature of 37 °C for a period of 24 h prior to testing. The wear assessments were conducted through the utilization of a chewing simulator (CS-4.2, SD Mechatronik, Feldkirchen-Westerham, Germany), consisting of two distinct chambers designed to replicate vertical and horizontal masticatory movements sequentially, while operating within an aqueous environment. Each chamber composed of a lower sample holder for specimen insertion and an upper loading tip serving as the counteracting element to the specimens under examination. An upper antagonist, in the form of a steatite ball with a 6 mm diameter, was employed. For each chosen specimen, a total of 15,000 simulated chewing cycles were executed at a frequency of 1.5 Hz, employing a vertical load of 2 kg to emulate a chewing force of 20 N. Subsequent to the simulations, wear patterns were assessed via a 3D optical profilometer (ContourGT-I, Bruker Nano, Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA). The average wear depth (in µm) was calculated based on the examination of the deepest points among six profiles within each specimen, representing a comprehensive measure of wear resistance.

Shrinkage stress

For measuring the shrinkage stress of evaluated composites, rods made of unidirectional FRC (Fiber-reinforced composite) with a 4 mm diameter and 4 cm length were used. The flat surfaces of each FRC rod were roughened using a 180-grit silicon carbide sand-paper. Thereafter, two FRC rods were firmly connected to a universal testing device (model LRX), followed by the application of a composite layer (1.5 mm thick) between the FRC rods surfaces. The curing process entailed the positioning of the curing tips of two light units (specifically, Elipar TM S10) in close proximity to the composite specimen, exposing it to a 20-second curing cycle from both sides. Polymerization shrinkage forces were tracked for a duration of 3 min (at room temperature 22 °C). By dividing the shrinkage force by the FRC rod’s cross-section area, shrinkage stress was obtained. The plateau situated at the terminal segment of the shrinkage stress/time curve was used to determine the maximum shrinkage stress value. Six trials were run for each tested composite.

Crown loading test

To facilitate consistent crown construction, a clear template mold (Memosil 2, Heraeus Kulzer GmbH, Hanau, Germany) of a standard (Frasaco) mandibular molar crown contour was employed. A total of 48 composite crowns (n = 8/group) were made of PFC and SFRC materials. The composite pastes were filled into the clear mold, and then subjected to light curing. The crowns were sequentially built up and polymerized in the same mold. Crowns of each material (n = 8) were cured from various sides utilizing a hand-light curing unit (Elipar TMS 10) for 40 s per increment. The light source was positioned quite close to the composite surface (1–2 mm). All crowns were polished and stored dry for 48 h at 37 °C preparing them for testing. The quasi-static compressive fracture test of crowns was conducted using a universal testing device (model LRX) operating at a speed of 1 mm/min. The acquired data were subsequently processed and recorded using specialized PC software (Nexygen Lloyd Instruments Ltd.). Prior to subjecting the crown specimens to static loading, double-sided adhesive tape was employed to affix the crowns securely to the flat metal substrate of the testing apparatus (spherical Ø 5 mm). The applied load was recorded until crown fracture, marked by the load-extension curve final drop. The failure patterns exhibited by the loaded crowns were visually inspected and categorized into two prevalent fracture forms, namely, catastrophic crushing and cracking.

Microstructure analysis

For evaluating the microstructure of the investigated PFC and SFRC composites SEM and EDS (energy-dispersive spectroscopy) (GeminiSEM 450, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) were used. Polished specimens (n = 2, single-edge notched beam) from each group were kept dry in a desiccator for 24 h. After that, specimens were gold coated in a vacuum evaporator utilizing a sputter coater (BAL-TEC SCD 050 Sputter Coater, Balzers, Liechtenstein) prior to SEM and EDS inspection.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with 0.05 significance level was employed to statistically analyze the data with SPSS version 23 (SPSS, IBM Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). The results were primarily assessed using Levene’s test to evaluate equality of variances. Tukey HSD post hoc analysis was used to ascertain the variations between tested materials.

Results

Table 2 gives a summary of the average scores for the tested PFC and SFRCs in terms of fracture toughness, flexural strength, flexural modulus, and DC%. everX Flow significantly outperforms (p < 0.05) all other composites that were tested in this study in terms of fracture toughness, with a resulted value of (2.8 MPa m1/2) and flexural strength (147 MPa). In contrast, Essentia and Fibrafill composite demonstrated statistically the lowest values for fracture toughness (1.1 MPa m1/2) compared to the other evaluated composites (p < 0.05). Essentia showed the lowest DC% value (42.1) among all composites (p < 0.05). everX posterior presented the highest flexural modulus with a value of (12.6 GPa) and comparable DC% to Fibrafill Flow and Fibrafill dentin (54.5, 54.7 and 53.2 respectively). The average values for wear depth after 15,000 chewing simulation cycles were recorded for each material and are displayed in Table 2. The analysis revealed that everX Flow exhibited the least average depth of wear (20.4 μm), demonstrating a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05), whereas Fibrafill Dentin displayed the highest level of wear (35.2 μm) among other tested SFRCs. The highest shrinkage stress value was reported for everX Flow (5.3 MPa) whereas other SFRCs had equivalent results (p > 0.05) (Table 2)

Table 2.

Mean values with standard deviations of fracture toughness (FT), flexural strength (FS), flexural modulus (FM), degree of conversion (DC), wear depth (WD), and shrinkage stress (SS)

| Material | FT (MPa m1/2) |

FS (MPa) |

FM (GPa) |

DC (%) |

WD (µm) |

SS (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essentia U | 1.1 ± 0.1a | 121 ± 9ab | 12.9 ± 1.4c | 42.1 ± 1.9a | 24.5 ± 5ab | 2.5 ± 0.3a |

| Alert | 1.7 ± 0.4b | 118 ± 18ab | 9.9 ± 0.9bc | 61.8 ± 0.3c | 28.5 ± 2.4b | 3.7 ± 0.2b |

| Fibrafill Flow | 1.1 ± 0.07a | 92 ± 12a | 6.8 ± 0.3a | 54.7 ± 0.3b | 29.6 ± 1.6b | 3.5 ± 0.04b |

| Fibrafill Dentin | 1.2 ± 0.1a | 98 ± 9a | 9.5 ± 0.6b | 53.2 ± 0.6b | 35.3 ± 2.5bc | 3.2 ± 0.01b |

| everX Flow | 2.8 ± 0.4cd | 147 ± 23c | 9.0 ± 0.7b | 62.8 ± 0.3c | 20.4 ± 4.9a | 5.3 ± 0.6c |

| everX Posterior | 2.6 ± 0.4c | 120 ± 5ab | 12.6 ± 2.8c | 54.5 ± 1.5b | 30.7 ± 0.6b | 3.9 ± 0.2b |

Materials with the same superscript letter above the values were statistically similar (p > 0.05)

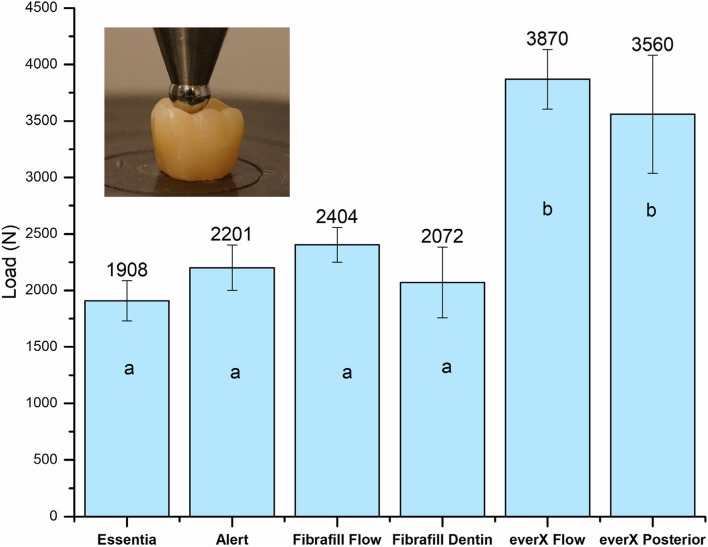

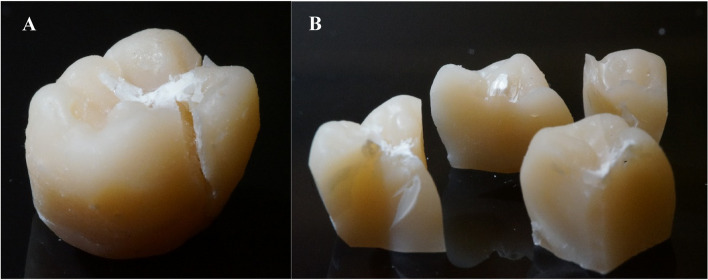

Crowns made of everX Flow (3870 ± 260 N) and everX Posterior (3560 ± 523 N) had significantly higher fracture resistance (Fig. 1) compared to all other investigated PFC and SFRCs (p < 0.05). In addition, crowns demonstrated mostly a cracking fracture pattern. While the crown specimens made from Essentia, Alert, Fibrafill Flow and Fibrafill Dentin showed mainly a catastrophic crushing fracture pattern (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Mean values of fracture resistance (N) and standard deviation (SD) of tested groups. The same letters inside the bars represent non-statistically significant differences (p > 0.05)

Fig. 2.

Photographs of fracture patterns of the crown specimens. A Cracking fracture pattern; B Catastrophic crushing fracture pattern

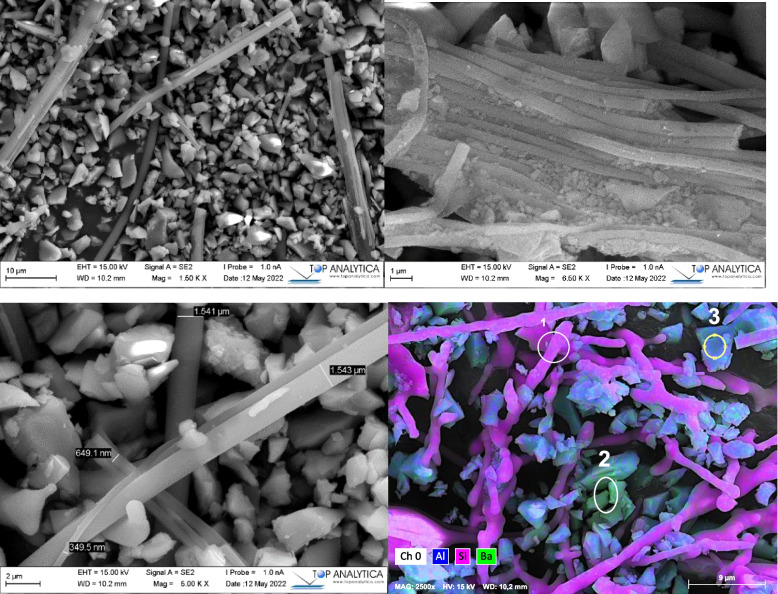

SEM analysis indicated various fiber aspect ratios (length/diameter of fibers) of each SFRC (Figs. 3 and 4) and thus offered a justification for the various toughening capacities of the tested SFRCs. Figure 4 with elemental mapping analysis revealed that Fibrafill composite has a submicron scale silica fiber.

Fig. 3.

SEM images of polished surface of tested PFC and SFRCs (magnification ×1000). A Essentia Universal; B Alert; C Fibrafill composite; D everX Flow; E everX Posterior

Fig. 4.

SEM images with an elemental mapping analysis showing the fiber, bundle, diameter, orientation and composition of Fibrafill composites

Discussion

In the literature, there are few studies comparing short fiber-reinforced restorative composites. In this study, five different commercially available SFRCs were investigated. They were all designed to be employed in high stress applications and were all made available to improve the posterior composite restorations’ ability to withstand fracture. However, our results showed distinct variations in the tested characteristics of SFRCs. Therefore, the hypothesis that material type has no effect on the SFRCs´ properties cannot be accepted. In this investigation, everX Flow (micrometer-scale SFRC) outperformed all other tested composites in terms of both fracture toughness (2.8 MPa m1/2) and flexural strength (147 MPa). This is consistent with earlier research that demonstrated the higher flexural properties and toughness of everX Flow [20, 21]. In dentistry, none of the recognized filling composite materials have displayed values of fracture toughness exceeding 2.6 MPa m1/2. As stated by Ilie and her colleagues, among direct filling materials, hybrid PFCs exhibited the highest fracture toughness, with an average measurement of 1.84 MPa m1/2 [22]. EverX Posterior (millimeter-scale SFRC) had quite high measured fracture toughness value (2.6 MPa m1/2), which is also consistent with other investigations that found it to have higher values than several commercially available hybrid and bulk-fill direct composites [23–25].

Short fibers promoted the material’s crack-resistance and helped to reduce the stress levels at low values in the crack tip, where cracks tend to grow in an improper manner. Consequently, it is possible to expect higher fracture toughness of SFRC materials. In his recent comprehensive review, Heintze et al., reported no connections among in-vivo clinical results and the flexural properties values of dental composites and only fracture toughness was connected with composites fracture in clinical set-up [26]. Additionally, a number of laboratory studies have shown a significant connection between fracture behavior of dental restorations and fracture toughness of the corresponding material [27, 28]. Particularly in biomimetic or bi-layered restorations made of an enamel-mimicking PFC veneer and a dentine-mimicking SFRC core, it was found that higher dentine-like fracture toughness in the SFRC resulted in a more naturally occurring fracture behavior [27–30].

Conversely and in line with our previous studies [14, 15], the fracture toughness of submicron scale SFRCs (both Fibrafill Flow and Fibrafill Dentin) and reduced aspect ratio SFRC (Alert) exhibited considerably reduced values when compared to those of everX Flow as well as everX Posterior (Table 1). To effectively reinforce polymers, a fiber must transmit stress from the polymer matrix to the fibers [16]. To successfully achieve this, it is imperative that the fibers possess a length equal to or exceeding the critical fiber length and exhibit an aspect ratio falling within the range of 30 to 94 [16]. The key variables that would increase or decrease the mechanical properties of SFRCs are the critical fiber length, aspect ratio and orientation of fibers as well as fibers´ loading [24]. Aspect ratio (l/d) is the ratio of fiber diameter to length and it has an influence on the fiber-reinforced material’s tensile strength and reinforcement effectiveness [16]. It is important to keep in mind that fibers and polymer matrix adhesion as well affects the critical fiber length (lc). Additionally, the composite can be adequately reinforced by using high aspect ratio fiber fillers of a minimum length. As we mentioned earlier, fiber-matrix bond must be enough to enable effective transfer of the stress to the stronger fiber, thereby fulfilling the essential function of fiber reinforcement. However, if adhesion is weak and there are gaps between the polymer matrix and fibers, these gaps may function as primary sites for the initiation of fractures within the matrix, thereby expediting the breakdown process of the material.

It was reported that the aspect ratio of everX Flow is approximately 30, primarily attributable to the presence of microglass fibers measuring 6 μm in diameter with length ranging from 200 to 300 μm [18, 19]. While everX Posterior has thicker fiber diameter (17 μm) and longer fibers, 300–1500 above the level of required aspect ratio critical fiber length [22, 23]. Consequently, it is predictable that adding short fiber fillers to a polymer matrix improves the material’s fracture toughness. On the other hand, Alert had a fiber diameter of 7 μm (Fig. 3) and length of 20–60 μm, whereas Fibrafill composites have fibers with a diameter in the micro/submicron scale (0.3–1.5 μm) with a length ranged from 10 to 50 μm, which is significantly less than the acquired aspect ratio and the critical fiber length (Figs. 3 and 4). This demonstrated that various microstructural characteristics as well as fiber aspect ratios (length and diameter) may vary in terms of wear and physical characteristics. This also explained why the commercial SFRCs had different values for fracture toughness.

Fibrafill Flow demonstrated the lowest flexural strength and modulus values of the examined SFRCs that can be attributed to the low level of filler load. Filler loading is of great importance and a thoroughly studied factor affecting the mechanical efficiency of dental composites. Both weight fraction and volume fraction can be used to describe filler loading, however, the latter is more important in terms of mechanical behavior. According to earlier research, filler loading and flexural performance are positively correlated [31, 32]. The filler loading threshold for composites with greatest toughness value of 55% by volume, according to Kim et al., [32]. However, everX Flow in this investigation, demonstrated improved mechanical values compared to other PFC and SFRCs with high volume filler loading. Our research showed that there is no direct correlation between the volumetric concentration of fillers and the parameters of material’s fracture resistance (toughness and strength). Other factors besides filler loading may be responsible for the differences in mechanical parameters between the investigated SFRCs. Among these SFRC composites, there might be variations in the filler particles’ and matrix’ adherence. Monomer structures and filler system of the resin matrix also affect the restorative materials´ mechanical properties.

Interestingly, the impregnation of submicron scale fibers into dimethacrylate dental resins has been shown to have dual impact: strengthening because of homogeneous fiber mixing and distribution, but weakening if the thin fibers aggregate in a mixing process to form bundles [33]. According to research by Vidotti and colleagues [34], when a small portion of the thin fibers in resin matrix began to bundle, generating mechanical weak sites that resulted in decreased mechanical characteristics [34]. It’s possible that the bundling of submicron scale fiber in this investigation also had a weakening impact. In a SEM picture, a fiber bundle in the Fibrafill SFRC is clearly visible (Fig. 4).

Of all the PFC and SFRCs tested, everX Flow exhibited the highest shrinking stress ratios. Polymerization shrinkage stress magnitude was found to depend on the reaction strength, volumetric shrinkage, material´s stiffness, and its capacity to flow [35]. everX Flow might have a high stiffness as a result to greater cross-linking density and higher DC%, that eventually leads to a high shrinking stress. On the other hand, because the material can only shrink perpendicular to the direction of the fibers, they may possess the capacity to regulate the shrinkage and the resultant stress occurring along the cavity walls because of their random orientation [25, 36]. In line with this, recent study showed that SRFCs are able to decrease the crack formation induced by shrinkage stress in MOD cavities compared to conventional PFC composites [37]. According to Tsujimoto and colleagues, cuspal deflection measurement for bulk fill composites ranged from 8 to 20 μm and maximum cuspal deflections apparent with everX Flow (12 μm) are within acceptable limits and raise no concerns for good clinical functionality [38]. In addition, a study by Jantarat et al., showed that cuspal deflection or displacement in the range of 40–50 μm can be well tolerated in teeth [39]. It should be emphasized that shrinkage stresses cannot be determined in clinical conditions. Our method has some limitations like rigidity of the system and inadequate imitation of cavity.

The occlusal contacts and clinical performance of dental composites can be impacted by their wear behavior over time. In the current investigation, a two-body impact-sliding wear test was chosen because owing to its utility and extensive adoption in the field [14, 20]. In order to mimic direct contact between the specimen and its opposing, the chewing simulation setup used, in addition to the vertical load, extra lateral movement of the specimen holder. Therefore, fatigue and abrasive wear types were mimicked within the same chewing simulation assembly. everX Flow had the lowest wear depth values (20.4 μm) in our investigation. Therefore, adding microfiber filler did not make the SFRC wear worse. These results give an indication that everX Flow might be utilized without coverage in a wide range of clinical applications. However, we must remember that the manufacturer recommends using micro- and millimeter size SFRCs (with exception to Alert) as a bulk basis or core but not as a surface restoration. They instructed to use a surface layer (1–2 mm) of conventional PFC composite for aesthetic purposes. Interestingly, the tested highly-filled SFRC (Fibrafill Dentin) had much higher wear depth values than the lower-filled SFRC (Fibrafill Flow), which was produced using a similar filler-fiber/silane manufacturing technique. This could be attributed to the matrix elastic deformation, which provides some shock-absorbing capability for the flowable composite [40].

The restorations in this study were designed to evaluate the failure mode and load-bearing capacity of a mandibular first molar restored using a direct approach for composite crown fabrication. This restorative design mimicked a scenario of significant loss of tooth structure. The results of the current investigation show that the crowns made of micrometer and millimeter scale SFRCs had the highest load-bearing capacity values. This observation can be clarified by the relatively high fracture toughness of everX Flow and everX Posterior when compared to other tested SFRCs. According to the literature, glass fibers can absorb stress from the polymer matrix, improving fracture behavior and load-bearing capacity values [8–10]. In contrast, the fracture characteristics observed in the crown specimens of Alert or Fibrafill composites primarily manifested as catastrophic crushing-like fracture. These observations suggest the dissemination of median-radial crack originating from the point of load application and extending throughout the whole thickness of the crown.

A limitation of this study is the use of a quasi-static compressive fracture test instead of applying cyclic loading to determine maximal load-bearing capacity. In clinical situations, stresses on teeth and dental restorations are generally low and repetitive rather than isolated and impact-driven. However, according to the literature, the fracture resistance under static loading is typically much higher than the functional occlusal load [5, 18, 21]. Therefore, this method remains valid for comparing restorative materials and different cavity designs. Additionally, since there is a linear relationship between fatigue and static loading, compressive static testing provides valuable insights into fracture behavior and load-bearing capacity [41].

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this comparison research, it is feasible to draw the conclusion that significant differences exist among the investigated characteristics of different commercially available SFRCs. It is noteworthy that certain SFRCs exhibited behavior comparable to that of conventional PFC, while others demonstrated superior performance.

Acknowledgements

This study belongs to the research activity of BioCity Turku Biomaterials Research Program (www.biomaterials.utu.fi).

Authors’ contributions

Study design, L.L. and S.G.; collection of data, S.G.; and M.F.; and F.K.; data analysis/interpretation, S.G., E.S. and L.L.; writing-original draft preparation, S.G. and M.F. and F.K.; writing-review and editing, L.L. and P.V.

Funding

The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors PV & ES consults for Stick Tech - Member of the GC Group in R&D and training. Other Authors declare to have no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Josic U, D’Alessandro C, Miletic V, Maravic T, Mazzitelli C, Jacimovic J, Sorrentino R, Zarone F, Mancuso E, Delgado AH, Breschi L, Mazzoni A. Clinical longevity of direct and indirect posterior resin composite restorations: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent Mater. 2023;39:1085–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demarco FF, Cenci MS, Montagner AF, de Lima VP, Correa MB, Moraes RR, Opdam NJM. Longevity of composite restorations is definitely not only about materials. Dent Mater. 2023;39:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bresser RA, Hofsteenge JW, Wieringa TH, Braun PG, Cune MS, Özcan M, Gresnigt MMM. Clinical longevity of intracoronal restorations made of gold, lithium disilicate, leucite, and indirect resin composite: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2023;27:4877–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdel-Maksoud HB, Eid BM, Hamdy M, Abdelaal HM. Optimizing fracture resistance of endodontically treated maxillary premolars restored with preheated thermos-viscous composite post-thermocycling, a comparative study. Part I. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forster A, Braunitzer G, Tóth M, Szabó BP, Fráter M. In Vitro Fracture Resistance of Adhesively restored molar teeth with different MOD cavity dimensions. J Prosthodont. 2019;28:e325–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaleh B, Kashfi M, Feizi, Mohazzab B, Shakhsi, Niaee M, Vafaee F, Fakhri P, Golbedaghi R, Fausto R. Experimental characterization and finite element investigation of SiO2 nanoparticles reinforced dental resin composite. Sci Rep. 2024;14:7794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naguib G, Maghrabi AA, Mira AI, Mously HA, Hajjaj M, Hamed MT. Influence of inorganic nanoparticles on dental materials’ mechanical properties. A narrative review. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23:897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aram A, Hong H, Song C, Bass M, Platt JA, Chutinan S. Physical properties and Clinical Performance of Short Fiber Reinforced Resin-based composite in posterior dentition: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Oper Dent. 2023;48:E119–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alshabib A, Jurado CA, Tsujimoto A. Short fiber-reinforced resin-based composites (SFRCs); current status and future perspectives. Dent Mater J. 2022;41:647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mangoush E, Garoushi S, Lassila L, Vallittu PK, Säilynoja E. Effect of Fiber reinforcement type on the performance of large posterior restorations: a review of in Vitro studies. Polym (Basel). 2021;13:3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thadathil Varghese J, Cho K, Raju, Farrar P, Prentice L, Prusty BG. Effect of silane coupling agent and concentration on fracture toughness and water sorption behaviour of fibre-reinforced dental composites. Dent Mater. 2023;39:362–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alshabib A, Algamaiah H, Silikas N, Watts DC. Material behavior of resin composites with and without fibers after extended water storage. Dent Mater J. 2021;40:557–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiu J, Belli R, Lohbauer U. Thickness influence of veneering composites on fiber-reinforced systems. Dent Mater. 2021;37:477–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lassila L, Keulemans F, Vallittu PK, Garoushi S. Characterization of restorative short-fiber reinforced dental composites. Dent Mater J. 2020;39:992–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garoushi S, Vallittu PK, Lassila L. Mechanical Properties and wear of five commercial Fibre-Reinforced filling materials. Chin J Dent Res. 2017;20:137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bijelic-Donova J, Garoushi S, Lassila LV, Rocca GT, Vallittu PK. Crack propagation and toughening mechanism of bilayered short-fiber reinforced resin composite structure -evaluation up to six months storage in water. Dent Mater J. 2022;41:580–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiu J, Belli R, Lohbauer U. Rising R-curves in particulate/fiber-reinforced resin composite layered systems. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2020;103:103537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fráter M, Sáry T, Vincze-Bandi E, Volom A, Braunitzer G, Szabó PB, Garoushi S, Forster A. Fracture behavior of Short Fiber-Reinforced Direct restorations in large MOD cavities. Polym (Basel). 2021, 13, 2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Attik N, Colon P, Gauthier R, Chevalier C, Grosgogeat B, Abouelleil H. Comparison of physical and biological properties of a flowable fiber reinforced and bulk filling composites. Dent Mater. 2022;38:e19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lassila L, Säilynoja E, Prinssi R, Vallittu P, Garoushi S. Characterization of a new fiber-reinforced flowable composite. Odontology. 2019;107:342–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lassila L, Keulemans F, Säilynoja E, Vallittu PK, Garoushi S. Mechanical properties and fracture behavior of flowable fiber reinforced composite restorations. Dent Mater. 2018;34:598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ilie N, Hickel R, Valceanu AS, Huth KC. ,.Fracture toughness of dental restorative materials. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16:489–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lassila L, Garoushi S, Vallittu PK, Säilynoja E. Mechanical properties of fiber reinforced restorative composite with two distinguished fiber length distribution. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2016;60:331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bijelic-Donova J, Garoushi S, Lassila LV, Keulemans F, Vallittu PK. Mechanical and structural characterization of discontinuous fiber-reinforced dental resin composite. J Dent. 2016;52:70–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garoushi S, Säilynoja E, Vallittu P, Lassila L. Physical properties and depth of cure of a new short fiber reinforced composite. Dent Mater. 2013;29:835–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heintze SD, Ilie N, Hickel R, Reis A, Loguercio A, Rousson V. Laboratory mechanical parameters of composite resins and their relation to fractures and wear in clinical trials-A systematic review. Dent Mater. 2017;33:101–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fráter M, Sáry T, Jókai B, Braunitzer G, Säilynoja E, Vallittu PK, Lassila L, Garoushi S. Fatigue behavior of endodontically treated premolars restored with different fiber-reinforced designs. Dent Mater. 2021;37:391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michelotto, Tempesta R, Saratti CM, Rocca GT, Pasqualini D, Alovisi M, Baldi A, Comba A, Scotti N. Effect of different fiber-reinforced solutions on fracture strength and pattern of endodontically treated molars. Int J Prosthodont. 2023;36:603–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magne P, Milani T, Short-fiber Reinforced MOD. Restorations of molars with severely undermined cusps. J Adhes Dent. 2023;25:99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alshetiwi DSD, Muttlib NAA, El-Damanhoury HM, Alawi R, Rahman NA, Elsahn NA, Karobari MI. Evaluation of mechanical properties of anatomically customized fiber posts using E-glass short fiber-reinforced composite to restore weakened endodontically treated premolars. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24:323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lohbauer U, Frankenberger R, Krämer N, Petschelt A. Strength and fatigue performance versus filler fraction of different types of direct dental restoratives. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2006;76:114–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim KH, Ong JL, Okuno O. The effect of filler loading and morophology on the mechanical properties of contemporary composites. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87:642–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L, Yu Q, Wang Y, Li H. BisGMA/TEGDMA dental composite containing high aspect-ratio hydroxyapatite nanofibers. Dent Mater. 2011;27:1187–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vidotti HA, Manso AP, Leung V, do Valle AL, Ko F, Carvalho RM. Flexural properties of experimental nanofiber reinforced composite are affected by resin composition and nanofiber/resin ratio. Dent Mater. 2015;31:1132–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szczesio-Wlodarczyk A, Garoushi S, Vallittu P, Bociong K, Lassila L. Polymerization shrinkage stress of contemporary dental composites: comparison of two measurement methods. Dent Mater J. 2024;43:155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garoushi S, Vallittu PK, Watts DC, Lassila LV. Polymerization shrinkage of experimental short glass fiber-reinforced composite with semi-inter penetrating polymer network matrix. Dent Mater. 2008;24:211–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Néma V, Sáry T, Szántó FL, Szabó B, Braunitzer G, Lassila L, Garoushi S, Lempel E, Fráter M. Crack propensity of different direct restorative procedures in deep MOD cavities. Clin Oral Investig. 2023;27:2003–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsujimoto A, Jurado CA, Barkmeier WW, Sayed ME, Takamizawa T, Latta MA, Miyazaki M, Garcia-Godoy F. Effect of layering techniques on polymerization shrinkage stress of high- and low-viscosity bulk-fill resins. Oper Dent. 2020;45:655–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jantarat J, Palamara JE, Messer HH. An investigation of cuspal deformation and delayed recovery after occlusal loading. J Dent. 2001;29:363–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lazaridou D, Belli R, Petschelt A, Lohbauer U. Are resin composites suitable replacements for amalgam? A study of two-body wear. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19:1485–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garoushi S, Lassila LV, Tezvergil A, Vallittu PK. Static and fatigue compression test for particulate filler composite resin with fiber-reinforced composite substructure. Dent Mater. 2007;23:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.