Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization recommends a cesarean delivery rate of 5–15%, which is thought to be within the range that can reduce infant morbidity and mortality. Various investigations have shown that those poor newborn outcomes are influenced by a variety of maternal and fetal factors and are more prevalent in emergencies than planned cesarean deliveries. Ethiopia is one of the five nations that account for 50% of all neonatal fatalities worldwide. Sub-Saharan African countries account for 38% of all infant deaths worldwide.

Aim

To know the determinants of adverse early neonatal outcomes after emergency cesarean delivery.

Method and material

A multicenter case-control study design would be carried out between November 2022 and January 2023. Using the consecutive method, a sample of 318 mother-newborn pairs was studied. Direct observation and face-to-face interviews were undertaken to gather the data using a semi-structured questionnaire. For both data input and analysis, Epi Data version 4.6 and Stata version 14 software were used. Both the crude and adjusted odds ratios were computed. The measure of significance was based on the adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval and a p-value of less than 0.05.

Results

Maternal age over 35, the presence of danger signs during pregnancy, and non-reassuring fetal heart rate were significantly associated with increased risk of adverse fetal outcomes following emergency cesarean section. Women aged over 35 were 3.6 times more likely to experience adverse fetal outcomes compared to younger women (AOR: 3.6, 95% CI: 1.1, 9.7). Women with danger signs during pregnancy were 3.5 times more likely to have adverse fetal outcomes compared to those without (AOR = 3.5, 95% CI: 2.4, 36). Similarly, cases with non-reassuring fetal heart rate were associated with a 5.2 times higher risk of adverse newborn outcomes (AOR = 5.2, 95% CI: 1.1, 26).

Conclusion

This study identified advanced maternal age (over 35 years old), pregnancy complications, and non-reassuring fetal heart rate as significant risk factors for adverse neonatal outcomes following emergency cesarean section.

Keywords: Cesarean delivery, Neonatal outcome, Adverse outcome, Ethiopia

Background

Neonatal mortality following cesarean delivery is three times greater than neonatal death following vaginal deliveries. Early neonatal outcomes following cesarean delivery are linked to preoperative and intraoperative fetal variables, the majority of which may be avoided [1].

The birth of a fetus through an anterior uterine wall incision made through surgery is known as cesarean delivery. A cesarean section is one of the most important forms of maternal health care and, depending on severity, has categories of emergency, urgent, scheduled, and elective [2, 3]. An emergency cesarean section was defined as one that required prompt delivery to reduce the risk to the pregnant woman or her infant. WHO recommends a cesarean delivery rate of 5–15%, which is thought to be within the range that can reduce infant morbidity and death [4]. A cesarean section is viewed as an indicator of a particular health care method (mode of delivery), not necessarily of perinatal outcome [5].

Various investigations have shown that these poor newborn outcomes are influenced by a variety of maternal and fetal factors and are more prevalent in emergencies than planned cesarean deliveries [6]. Around 2.6 million babies died worldwide in 2016, which equates to 7,000 neonatal fatalities every day [7]. In sub-Saharan Africa, 8.8% of all deliveries are through cesarean Sects. [8, 9], and sub-Saharan Africa had higher rates of newborn death following cesarean birth than the world standard [10]. Ethiopia is one of the five nations that account for 50% of all neonatal fatalities worldwide. Sub-Saharan African countries account for 38% of all infant deaths worldwide [7].

By ensuring access to quality healthcare services, including the ability to have a C-section, we can significantly reduce newborn mortality. C-sections can prevent 24% of these deaths [11–13]. However, multiple factors have been linked to poor newborn outcomes following cesarean sections, including parity, distance between institutions before interventions, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, anesthesia type, birth weight, and indications of cesarean procedures [7, 14–16]. Studies on the variables that affect the fetal outcome following an emergency cesarean surgery are few. The results of this study may be utilized as input by healthcare professionals and governmental organizations on the actions required to enhance the quality of treatment throughout pregnancy, labor, and delivery since these factors, which will be discovered, may be adjustable.

Method and material

Study area

East Gojjam Zone is one of thirteen administrative zones in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia. Its capital city, Debre Markos, is situated approximately 300 km northwest of the national capital, Addis Ababa. The zone encompasses eleven hospitals: ten primary hospitals (Lumame, Bechena, Mota, Yejube, Debre Elias, Debre Work, Shebel, Dejen, Mertolemaria, and Bibugn) and one specialized facility, Debre Markos Comprehensive Specialized Hospital.

Study design and period

A hospital-based case-control study was conducted at the eleven public hospitals in East Gojjam Zone from November to January 30, 2023.

Population

Source of population

all neonates delivered by emergency cesarean section at East Gojjam Zone Public Hospital.

Source of population

all neonates delivered by emergency cesarean section during study period at East Gojjam Zone Public Hospitals.

Sample size calculation and sampling technique

The required sample size for this investigation was calculated using a double population formula implemented in Epi Info statistical software version 3.7.2. Based on data from previous studies, the following parameters were used: Outcome in the unexposed group: 72.8%, power: 80%, ratio of exposed to unexposed participants: 1:1, odds ratio: 4.6, confidence level: 95% These parameters resulted in a calculated sample size of 160 participants who developed adverse neonatal outcomes and 160 who did not, for a total of 320 participants. To account for a potential 5% non-response rate, the final sample size was adjusted to 336 participants [1].

Sampling procedure

To achieve the required sample size within the study timeframe, a consecutive sampling technique was employed at the selected hospital. This method involved enrolling all eligible participants who met the inclusion criteria as they presented consecutively during the study period until the target sample size was reached (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

schematic presentation of the sampling procedure

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

neonates who were delivered by emergency cesarean delivery and stillbirths at cesarean delivery who had a positive fetal heartbeat preoperatively were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

neonates born via emergency cesarean section and presenting with one or more of the following: Grossly lethal congenital anomaly diagnosed pre- or postoperatively, Multiple pregnancies, Intrauterine fetal death diagnosed upon hospital admission, Maternal inability or refusal to provide medical history due to a medical disease or obstetric complication.

Study variable

Dependent variable

early neonatal outcome (adverse or good neonatal outcomes).

Independent variable

socio-demographic factors, obstetric factors, decision to different activity, indications for emergency cesarean section, procedure-related factors, Provider and resource factor.

Operation definitions

Early neonatal outcome

condition of a neonate in the first seven days after an emergency cesarean delivery, which can be good or adverse.

Adverse neonatal outcomes

stillbirth, low Apgar score (≤ 7), admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, early neonatal death.

Good/favorable early neonatal outcomes

good Apgar (> 7) at the first and fifth minutes, absence of admission to the neonatal intensive care unit.

Latent stage of labor is

the initial stage of labor characterized by cervical dilation typically progressing from 1 to 4 centimeters [17].

Active stage of labor begins

when the cervix dilates to 5 centimeters and continues until it reaches full dilation (10 centimeters) [17].

The second stage of labor begins

when the cervix is fully dilated at 10 centimeters and ends with the delivery of the baby.

Danger signs of pregnancy

is any symptom or change in the body that is reported by the pregnant woman herself, observed by a healthcare provider during a routine check-up, or identified through specific medical tests or examinations i.e. bleeding during pregnancy, severe headache, blurring of vision, epigastric pain, gush of fluid per vagina.

A non-reassuring fetal heart rate (NRFHR)

is characterized by abnormal changes in the baby’s heart rate, such as being too fast (180 beats per minute), too slow (< 100 beats per minute), or having irregular patterns.

Data collection procedure

Before data collection began, the mother’s willingness to participate was ascertained by verbal consent after she had been told of the study’s goals and benefits. The data was gathered by six experienced midwives who had received training in data collection. To prevent problems during collection, they were overseen by a qualified supervisor. Data collection was conducted through passive observation. Data collectors were trained to observe and record information without interfering with the standard care provided by healthcare professionals. However, on discharge, data collectors inform mothers to bring the neonate if they have a danger sign. Data Interviews were conducted with each participant and pertinent information was taken from medical records. In order to monitor the potential emergence of the other outcome variables during the first seven days, neonates who were admitted to the NICU, released from the maternity department, and who continued there due to maternal indication were tracked. Healthy newborns who had been discharged were monitored by data collectors assigned to them (midwives) until the seventh day of life. During the phone interview, the mother was asked questions about the newborn, such as whether it was nursing, sleeping well, and alert, and whether she had been told to bring it back if there was a problem. An organized English checklist with questions concerning maternal and neonatal problems was developed. The data included maternal socio-demographic variables, previous obstetric history, antenatal care, obstetric and medical complications, and indications of cesarean delivery. And intraoperative events like type of anesthesia and incision to delivery time. Data regarding neonatal status included sex, weight, and the first and fifth minutes. Apgar’s need for NICU admission for more than 24 h and the presence of death (stillbirth or early neonatal death).

Data processing and analysis

After being checked, coded, and put into Epi Data version 4.6, the data was exported to Stata IC14 for analysis. The socio-demographic, obstetric, professional, resource and decision-to-different-time activity characteristics of the participants were presented using descriptive statistics. The adverse neonatal outcomes would initially be determined; then, the results would be dichotomized into yes or no, depending on the outcomes. Finally, binary logistic regression was fitted to determine factors of adverse fetal outcomes.

Results

Socio-demographic factor

A total of 318 participants were involved in this study, with a response rate of 94.6%. The mean age of mothers who participated was 28 ± 5. Moreover, 90.6% of mothers with adverse neonatal outcomes and 91.8% of mothers with favorable neonatal outcomes were married. Thirty-eight (23.9%) mothers with adverse neonatal outcomes and thirty-one (19.5%) mothers with favorable neonatal outcomes have a diploma and above the level of education. 63.5% of mothers with adverse neonatal outcomes and 70.4% of mothers with favorable neonatal outcomes were living in urban areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Result of socio-demographic factor adverse newborn outcomes after emergency cesarean section at East Gojjam Zone public hospital, 2023

| Variables | Categories | Adverse neonatal outcomes n(%) | Favorable neonatal outcomes n(%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | primary Hospital | 13(8.2) | 17 (10.7) | 0.44 |

| Referral Hospital | 146(91.8) | 142(89.3) | ||

| Age | < 20 | 1(0.6) | 7(4.4) | 0.038 |

| 20–24 | 35(22) | 38(23.4) | ||

| 25–29 | 71(44.7) | 58(36.5) | ||

| 30–35 | 35(22) | 47(29.6) | ||

| ≥35 | 17(10.7) | 9(5.7) | ||

| Marital status | single | 4(2.5) | 3(1.9) | 0.52 |

| married | 144(90.6) | 146(91.8) | ||

| divorced | 7(4.4) | 9 (5.7) | ||

| widowed | 4 (2.5) | 1(0.6) | ||

| Level of education | cannot read and write | 30 (18.9) | 30(18.9) | 0.72 |

| read and write | 11 (6.9) | 18(11.3) | ||

| elementary | 33(20.8) | 29 (18.2) | ||

| high school | 35 (22) | 37(23.3) | ||

| preparatory | 12 (7.5) | 14(8.8) | ||

| diploma and above | 38 (23.9) | 31(19.5) | ||

| Occupation | housewife | 74 (46.5) | 7(4.4) | 0.18 |

| government employee | 29 (18.2) | 21(13.2) | ||

| daily labor | 7 (4.4) | 11(69.2) | ||

| farmer | 36 (22.6) | 32(20.1) | ||

| merchant | 11 (6.9) | 21(13.2) | ||

| Student | 2 (1.3) | 0(0) | ||

| Residence | urban | 101 (63.5) | 112(70.4) | 0.19 |

| rural | 58 (36.5) | 47(29.6) |

Obstetrics-related factor

Among mothers undergoing emergency cesarean sections, 79 (49.7%) with adverse neonatal outcomes and 91 (57.2%) with favorable neonatal outcomes were in the latent first stage of labor. Conversely, 19.5% of mothers with adverse neonatal outcomes and 10.7% with favorable neonatal outcomes were in the second stage of labor. In forty-six (28.9%) adverse and fifty-two (32.7%) favorable neonatal outcomes, an emergency cesarean section was done during the nighttime. 94.3% of mothers with adverse neonatal outcomes and 96.2% of mothers with favorable neonatal outcomes have antenatal follow-up during the pregnancy period. 59.1% of mothers with adverse and 61.6% of mothers with favorable neonatal outcomes were counseled for birth preparedness and complication readiness during pregnancy time. 9.5% of mothers with adverse and 3.8% of mothers with favorable neonatal outcomes have obstetric complications during pregnancy. One hundred thirty-three (83.6%) mothers with adverse neonatal outcomes and one hundred thirty-seven (86.2%) mothers with favorable neonatal outcomes were term gestational age (Table 2).

Table 2.

Result of obstetrics related factors of newborn outcomes after emergency cesarean section at East Gojjam Zone public hospital, 2023

| Variables | Categories | Adverse neonatal outcomes n (%) | Favorable neonatal Outcomes n (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage of labor | latent | 79(49.7) | 91(57.2) | 0.08 |

| active | 49(30.8) | 51(32.1) | ||

| second | 31(19.5) | 17 (10.7) | ||

| Working time | day | 113(71.1) | 107(67.3) | 0.45 |

| Night | 46(28.9) | 52(32.7) | ||

| Parity | Prim Para | 63(39.6) | 60(37.7) | 0.43 |

| Multi para | 96(60.4) | 99(62.2) | ||

| ANC | yes | 150(94.3) | 153(96.2) | 0.42 |

| no | 9(5.7) | 6(3.7) | ||

| Number of ANC contact | one | 4(2.5) | 3(1.9) | 0.30 |

| two | 25(15.7) | 30(18.9) | ||

| three | 43(27.1) | 30 (18.9) | ||

| four and above | 79(49.7) | 90 (56.6) | ||

| BPCR counseled | Yes | 94(59.1) | 98(61.6) | 0.6 |

| no | 65(40.9) | 61(38.4) | ||

| Danger sign/obstetric complication | yes | 31(19.5) | 6(3.8) | 0.00 |

| no | 128(80.5) | 153(96.2) | ||

| Type of obstetric complication | Antepartum hemorrhage | 13(35.1) | 11(29.7) | 0.15 |

| Pregnancy Induced Hypertension | 11(18.9) | 1(2.7) | ||

| Premature rupture of membrane | 7(2.7) | 0(0) | ||

| Gestational Age | term | 133(83.6) | 137(86.2) | 0.25 |

| post term | 26(16.4) | 22(13.8) | ||

| Referral | yes | 116(72.9) | 94(59.1) | 0.09 |

| no | 43(27.1) | 65(40.9) | ||

| History of emergency CS | yes | 24((15.1) | 48(30.2) | 0.01 |

| no | 135(84.9) | 111(69.8) | ||

| Immediate consent accepted | yes | 137(86.2) | 148(93.1) | 0.04 |

| no | 22(13.9) | 11(6.9) |

ANC: Antenatal care, BPCR: Birth preparedness complication readiness, CS: Cesarean section

Resource and professional-related factors

Obstetrician-gynecologists performed emergency cesarean sections in 34 (21.4%) cases with adverse neonatal outcomes and 43 (27%) cases with favorable outcomes. MSc in clinical midwifery students conducted the procedure in 28.3% of cases with adverse neonatal outcomes and 27.7% of cases with favorable outcomes. The majority of cases, both adverse (45.3%) and favorable (46.5%) neonatal outcomes, received anesthesia from a BSc student (Table 3).

Table 3.

Result of resource and professional related determinant factors of newborn outcomes after emergency cesarean section at east Gojjam Zone public hospital, 2023

| Variables | Categories /Level | Adverse Neonatal outcomes | Favorable Neonatal Outcomes | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free functional OR table present while the women arrive OR | Yes | 125(78.6) | 139(87.4) | 0.04 |

| No | 34 (21.4 | 20(12.6) | ||

| OR material available while the women arrive at the OR | Yes | 131(82.4) | 141(88.7) | 0.11 |

| No | 28 (17.6) | 18(11.3) | ||

| Surgeon | Oby-Gyn specialist | 34 (21.4) | 43(27) | 0.18 |

| IESO | 50(31.4) | 55(34.6) | ||

| MSc in clinical midwifery | 30 (18.9) | 17(10.7) | ||

| MSc in clinical midwifery student | 45(28.3) | 44(27.7) | ||

| Anesthetist | MSc holder | 12(7.5) | 12(7.5) | 0.46 |

| BSc holder | 61 (38.4) | 66(41.5) | ||

| BSc student | 72(45.3) | 74(46.5) | ||

| level 5 holder | 14(8.8) | 7(4.4) | ||

| Midwifery | MSc/MPH Holder | 10 (6.3) | 18(11.3) | 0.06 |

| BSc holder | 134(84.3) | 117(73.6) | ||

| level IV holder | 15(9.4) | 24(15.1) |

OR: operation Table, OBY-GYN obstetrician and gynecologist, IESO: Integrated emergency surgeon officer

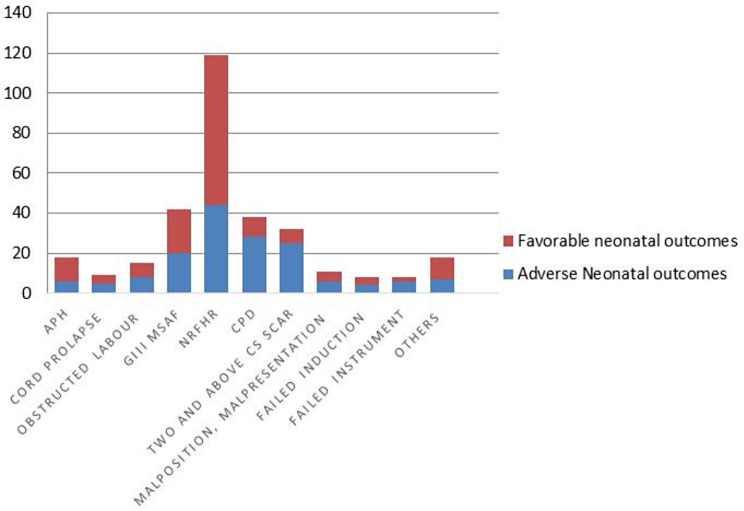

Indication of emergency cesarean section

Non-reassuring fetal heart rate was the most common indication for an emergency cesarean section, accounting for 37.4% of cases. Other significant indications included meconium-stained amniotic fluid (GIII) at 13.2%, cephalopelvic disproportion at 11.9%, and a history of two or more previous cesarean sections in labor at 10.2% (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Indication of emergency cesarean section at East Gojjam zone public Hospital 2023. APH: Antepartum Hemorrhage, NRFHR: Non-reassuring Fetal Heart rate, GIII MSAF, Grade III Meconium Stained Amniotic Fluid, CPD: Cephalo-pelvic Disproportion

Determinant of adverse neonatal outcome after emergency cesarean section at East Gojjam zone public hospital

The bivariate logistic regression analysis showed that stage of labour, a danger sign during pregnancy, the mother being referred from another facility, immediate consent accepting, indication, and decision-to-delivery of emergency cesarean section were determinant factors of adverse fetal outcome after emergency cesarean section. After adjustment for a possible effect of confounding.

Variables: maternal age above 35, danger sign during pregnancy, and indication of non-reassuring fetal heart rate were significantly and positively associated with adverse fetal outcomes after emergency cesarean section. Maternal age above 35 years old has 3.6 times more chances of developing adverse fetal outcomes compared to counter-one (AOR = 3.6, 95%CI: 1.1, 9.7). The danger sign during pregnancy is 3.5 times more adverse to the fetal outcome as compared to those who don’t have the danger sign (AOR = 3.5, 95%CI: 2.4, 36). An indication of NRFHR was 5.2 times more adverse newborn outcome compared to counter one (AOR = 5.2, 95%CI: 1.1, 26) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of determinant factors of newborn outcomes after emergency cesarean section at east Gojjam Zone public hospital December-January, 2023

| Variable | Adverse outcomes (n = 159) | Favorable outcomes (n = 159) | COR(95%CI) | AOR(95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of mother | ||||

|

< 20 20–24 25–29 30–35 > 35 |

1(0.6) 35(22) 71(44.7) 35(22) 17(10.7) |

7(4.4) 38(23.4) 58(36.5) 47(29.6) 9(5.7) |

1 6.4(0.75, 55) 8.5(1.2, 71.6) 5.2(0.6, 44) 1.3(1.3, 124) |

1 4.1(0.45, 37) 7.1(0.8,61) 4.5(0.5, 20) 3.6(1.1, 9.7) |

| Stage of labour Latent | ||||

|

First stage Active first stage Second stage |

79(49.7) 49(30.8) 31(19.5) |

91(57.2) 51(32.1) 17(10.7) |

1 0.9(0.55, 1.4) 0.5(0.24, 0.92) |

1 0.75(0.4, 1.4) 0.6(0.25,1.6) |

| Danger sign | ||||

|

Yes No |

31(19.5) 128(80.5) |

6(3.8) 153(96.2) |

6.2(2.5, 15.2) 1 |

3.5(2.4, 36) 1 |

| Referred from another facility | ||||

|

Yes No |

116(72.9) 43(27.1) |

94(59.1) 65(40.9) |

1.8(1.2, 2.9) 1 |

1.6(0.9,2.7) 1 |

| History emergency cesarean section | ||||

|

Yes No |

24(15.1) 133(84.9) |

48(30.2) 111(69.8) |

0.4(0.24, 0.71) 1 |

0.5(0.2, 1.1) 1 |

| Consent accepted immediately for ECS | ||||

|

Yes No |

137(86.2) 22(13.9) |

148(93.1) 11(6.9) |

1 2.2(1.1, 4.6) |

1 1.4(0.6,3.6) |

| Indication of ECS | ||||

|

APH Cord prolapse Obstructed labour GIII MSAF NRFHR CPD Two scars in labour Others |

6(3.7) 5(3.4) 8(5) 20(12.6) 44(27.7) 28(17.6) 25(15.7) 23(14.5) |

12(7.6) 4(2.5) 7(4.4) 22(13.8) 75(47.2) 10(6.3) 7(4.4) 22(13.8) |

1 0.4(0.8, 2.1) 0.4(0.11, 1.8) 0.6(0.17, 1.7) 0.8(1.3, 2.4) 0.2(0.05, 0.6) 0.14(0.04, 0.5) 0.5(0.15, 1.5) |

1 4.2(0.49, 2.7) 3.6()0.52,25 3.2(0.6,17) 5.2(1.1–26) 1.5(0.24,9.4) 1.2(0.2,8) 2.9(0.55,15) |

| Decision-to-delivery time | ||||

|

≤ 30 min > 30 min |

37(23.3) 122(76.7) |

27(17) 132(83) |

1 1.5(0.85, 2.6) |

1 1.7(0.87, 3.3) |

ECS: Emergency Cesarean Section, APH: Antepartum Hemorrhage, NRFHR: Non-reassuring Fetal Heart rate, GIII MSAF, Grade III Meconium Stained Amniotic Fluid, CPD: Cephalo-pelvic Disproportion

Discussion

Emergency cesarean section carries adverse newborn outcomes. Knowing factors influencing birth results in addition to cesarean delivery can help to prevent unfavorable newborn outcomes since cesarean delivery is more likely to be associated with an elevated risk for respiratory problems and depression at birth [18]. On the other hand, the quality of medical care, timely management, and clear indication of an emergency cesarean section are crucial to reducing the overall mortality and morbidity of newborns. Advanced maternal age (35 years), the occurrence of danger signs during pregnancy, and the presence of non-reassuring fetal heart rate (NRFH) were identified as risk factors for adverse neonatal outcomes following emergency cesarean delivery.

There have been reports of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), low birth weight (LBW), stillbirth, and intrauterine fetal death (IUFD) among newborns born to advanced maternal-age women [19, 20]. This study found that maternal age above 35 years old significantly affected newborn outcomes after emergency cesarean section. A consistent finding was reported from Israel, Belgium, and the United Kingdom [19–23]. This consistency may be due to age-related uterine changes that can interfere with embryo implantation and subsequent fetal development. Additionally, older women are more susceptible to pre-existing health conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, or autoimmune diseases, which can increase pregnancy complications.

WHO encourages health services to work together with women, their families, and the larger community to provide accurate and understandable information on the danger signs of pregnancy complications any woman can experience. They further suggest that everybody involved be aware of where to go for medical attention in an emergency. This study found that women who have obstetric complications during pregnancy significantly affected newborn outcomes after emergency cesarean delivery. A consistent report was observed from Ethiopia: Jimma and Arbaminch, Nigeria [24–26]. This consistency may be due to similarities in maternal awareness and health-seeking behavior as well as economic constraints to detect and manage at the primary healthcare level. In addition, conditions like preeclampsia or placental abruption can restrict oxygen and nutrient flow to the fetus, leading to growth restrictions, stillbirth, or neonatal death.

Fetal heart rate patterns that are unsettling (NRFHRP) indicate fetal conciliation or a declining capacity to withstand the strain of childbirth. NRFHRP largely accounts for about half of the stillbirths that occur globally since fetal hypoxia and non-reassuring fetal conditions might result from disturbances in maternal oxygenation, uterine blood flow, placental transfer, or fetal gas transport. This study found that NRFHR is a determinant factor for adverse newborn outcomes. A consistent report was seen by India [27] but a contrary finding was reported in Tanzania and the United States of America [28, 29]. This controversial report may be the result of the heterogeneity of factors contributing to NRFHR in utero. Some factors, such as uterine hyperstimulation and aortocaval compression, cause reversible NRFHR, which is transient and does not affect the Apgar score in the first minute. Other factors, such as umbilical cord compression and placental abruption, cause irreversible NRFHR, which may affect the Apgar score in the first minute.

Strength of study

The study employed a multicenter design, encompassing three representative hospitals to enhance generalizability of the findings. By incorporating an equal proportion of neonates with favorable and unfavorable outcomes, the study aimed to control for confounding factors while identifying determinants associated with adverse neonatal outcomes following emergency cesarean delivery.

Limitation

While the multicenter design, encompassing three representative hospitals, enhanced generalizability, the variation in hospital levels, including primary and comprehensive facilities, could introduce heterogeneity in emergency cesarean delivery setups and neonatal care, which may impact the study’s findings.

Conclusion

This study found that determinant factors of newborns after emergency cesarean section were advanced maternal age, pregnancy-related complications during pregnancy, and intrapartum fetal condition. Maternal age above 35, danger sign during pregnancy, and non-reassuring fetal heart rate were the determinants of adverse newborn outcomes after emergency cesarean section. Therefore, efforts should be made to improve maternal awareness on complications of birth outcomes after advanced maternal age and complications during pregnancy, as well as efforts should be made to improve the quality of intrapartum care services since newborn outcomes are affected by non-reassuring fetal conditions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participant and data collectors as well as supervisors for their dedication to data collection in an organized manner.

Abbreviations and Acronym

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- APH

Antepartum hemorrhage

- ANC

Antenatal care

- BPCR

Birth Preparedness Complication readiness

- CS

Cesarean Section

- ECS

Emergency Cesarean Section

- IESO

Integrated Emergency Surgeon Officer

- MSc

Master of Science

- NICU

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- NRFHR

Non-reassuring Fetal Heart Rate

- OR

Operation Room

Author contributions

Beyene sisay Damtew: wrote the main manuscript text and figure all others co-authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The data sets used and analyzed during this study was available from corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participants

All method was conducted according the ethical standards of the declaration Helsinki. The study was conducted under the Ethiopian Health Research Ethics Guidelines. Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Gondar’s Ethical Review Committee with Ref-MIDW/30/2015 E.C. A formal letter of administrative and case team manager approval was obtained from the three hospitals. Informed consent was taken from each of the study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Elias S, Wolde Z, Tantu T, Gunta M, Zewudu D. Determinants of early neonatal outcomes after emergency cesarean delivery at Hawassa University comprehensive specialised hospital, Hawassa, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3):e0263837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Neill KM, Greenberg SL, Cherian M, Gillies RD, Daniels KM, Roy N, et al. Bellwether procedures for monitoring and planning essential surgical care in low-and middle-income countries: caesarean delivery, laparotomy, and treatment of open fractures. World J Surg. 2016;40(11):2611–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucas D, Yentis S, Kinsella S, Holdcroft A, May A, Wee M, et al. Urgency of caesarean section: a new classification. J R Soc Med. 2000;93(7):346–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNFPA WU. AMDD. Monitoring emergency obstetric care: a handbook. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foumane P, Mando E, Mboudou ET, Sama JD, Pisoh WD, Minkande JZ. Outcome of cesarean delivery in women with excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014;2014.

- 6.Shenoy H, Shenoy S, Remash K. Determinants of primary vs previous caesarean delivery in a tertiary care institution in Kerala, India. Int J Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;3(5):229–36. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hug L, Alexander M, You D, Alkema L. National, regional, and global levels and trends in neonatal mortality between 1990 and 2017, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2019;7(6):e710–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah A, Fawole B, M’imunya JM, Amokrane F, Nafiou I, Wolomby J-J, et al. Cesarean delivery outcomes from the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Africa. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;107(3):191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavallaro FL, Cresswell JA, França GV, Victora CG, Barros AJ, Ronsmans C. Trends in caesarean delivery by country and wealth quintile: cross-sectional surveys in southern Asia and sub-saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:914–D22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison MS, Goldenberg RL. Cesarean section in sub-saharan Africa. Maternal Health Neonatology Perinatol. 2016;2(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darteh EKM, Doku DT, Esia-Donkoh K. Reproductive Health decision making among Ghanaian women. Reproductive Health. 2014;11(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Organization WH. World Health statistics 2016 [OP]: Monitoring Health for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). World Health Organization; 2016.

- 13.You D, Hug L, Ejdemyr S, Idele P, Hogan D, Mathers C, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in under-5 mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2275–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Algert CS, Bowen JR, Giles WB, Knoblanche GE, Lain SJ, Roberts CL. Regional block versus general anaesthesia for caesarean section and neonatal outcomes: a population-based study. BMC Med. 2009;7(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mundhra R, Agarwal M. Fetal outcome in meconium stained deliveries. J Clin Diagn Research: JCDR. 2013;7(12):2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wylie BJ, Gilbert S, Landon MB, Spong CY, Rouse DJ, Leveno KJ, et al. Comparison of transverse and vertical skin incision for emergency cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(6):1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofmeyr GJ, Bernitz S, Bonet M, Bucagu M, Dao B, Downe S, et al. WHO next-generation partograph: revolutionary steps towards individualised labour care. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;128(10):1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liston FA, Allen VM, O’Connell CM, Jangaard KA. Neonatal outcomes with caesarean delivery at term. Archives Disease Childhood-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93(3):F176–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenny LC, Lavender T, McNamee R, O’Neill SM, Mills T, Khashan AS. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcome: evidence from a large contemporary cohort. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e56583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delbaere I, Verstraelen H, Goetgeluk S, Martens G, De Backer G, Temmerman M. Pregnancy outcome in primiparae of advanced maternal age. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reproductive Biology. 2007;135(1):41–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leader J, Bajwa A, Lanes A, Hua X, White RR, Rybak N, et al. The effect of very advanced maternal age on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2018;40(9):1208–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schimmel MS, Bromiker R, Hammerman C, Chertman L, Ioscovich A, Granovsky-Grisaru S, et al. The effects of maternal age and parity on maternal and neonatal outcome. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291:793–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lean SC, Derricott H, Jones RL, Heazell AE. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10):e0186287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chufamo N, Segni H, Alemayehu YK. Incidence, contributing factors and outcomes of antepartum hemorrhage in Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. Univers J Public Health. 2015;3(4):153–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gebremeskel F, Gultie T, Kejela G, Hailu D, Workneh Y. Determinants of adverse birth outcome among mothers who gave birth at hospitals in Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia: a facility based case control study. Qual Prim Care. 2017;25(5):259–66. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doctor HV, Findley SE, Cometto G, Afenyadu GY. Awareness of critical danger signs of pregnancy and delivery, preparations for delivery, and utilization of skilled birth attendants in Nigeria. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(1):152–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jadhav CA, Tirankar V, Gavandi P. Study of early perinatal outcome in lower segment caesarean section in severe foetal distress at tertiary care centre. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2020;9(3):1259–68. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirani BA, Mchome BL, Mazuguni NS, Mahande MJ. The decision delivery interval in emergency caesarean section and its associated maternal and fetal outcomes at a referral hospital in northern Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qureshey EJ, Mendez-Figueroa H, Wiley RL, Bhalwal AB, Chauhan SP. Cesarean delivery at term for non-reassuring fetal heart rate tracing: risk factors and predictability. J Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(25):6714–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analyzed during this study was available from corresponding author.