Abstract

Background & Aim

We aimed in this study to investigate the relationship between Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT) use and the risk of heart failure in patients with prostate cancer. In this research, the negative or positive effects of ADT in the development of cardiovascular diseases or its exacerbation in people with prostate cancer have been investigated.

Materials and methods

For this research, we reviewed articles from PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases until February 2024. We extracted and screened titles, abstracts, and full texts of related articles. The quality of studies was assessed and extracted and analyzed data.

Result

A total of 9 studies comprising 189,045 patients were included in the meta-analysis, examining the association between androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and heart failure. The overall pooled hazard ratio (HR) was 1.299 (95% CI: 1.003–1.595), indicating a significantly increased risk of heart failure with ADT. Subgroup analyses revealed that the risk was stronger in Asian populations (pooled HR = 1.545, 95% CI: 1.180–1.910) compared to North American populations (pooled HR = 0.779, 95% CI: 0.421–1.138).

Conclusions

ADT has a significant relationship with cardiovascular disease. According to the analysis, ADT has increased the risk of heart failure in people with prostate cancer by 30%.

Keywords: Androgen deprivation therapy, Prostate cancer, Cardiovascular disease, heart failure

Introduction

Prostate cancer is recognized as the second most prevalent malignancy among men globally [1]. It is also one of the leading causes of cancer-associated death worldwide, with more than 350,000 cancer-related deaths annually [2–4]. The likelihood of developing prostate cancer increases as individuals grow older, with more than 85% of newly identified cases occurring in people aged over 60 [5, 6]. Active surveillance, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and surgery are among the treatment options for prostate cancer. Factors such as evidence of metastasis, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, tumor grade and stage, and the possibility of disease recurrence influence treatment decisions [7].

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), usually referred to as hormonal therapy, stands out as one of the most effective systemic treatments for prostate cancer. ADT is recommended for the management of metastatic prostate cancer. Moreover, ADT is frequently utilized as neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy in many cases of high-risk locally advanced and recurrent prostate cancers [2, 8]. The main goal of this treatment, whether through surgical or pharmacological means, is to decrease androgen levels to castration levels [9]. While orchiectomy is the surgical method of this treatment, pharmacological ADT involves the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists like leuprolide or GnRH antagonists like degarelix. Despite the survival benefits observed in men with prostate cancer receiving this treatment, some prior studies have indicated an elevated risk of cardiovascular events in patients undergoing ADT [9, 10].

The fact that cardiovascular incidents are a primary cause of death not related to cancer in males with prostate cancer is significant [11], there is a crucial need to investigate the predisposing factors of cardiovascular events in this patient population. While some studies have examined the association between ADT and cardiovascular events, there is a scarcity of research focusing on the potential association between this treatment and the increased incidence of heart failure [12]. The primary objective of the present study is to assess the impact of ADT on the occurrence of heart failure in individuals with prostate cancer. To the best of our knowledge, for the first time, this meta-analysis aimed to investigate the relationship between ADT and heart failure.

Methods

To examine the association between androgen deprivation therapy and the risk of heart failure in patients with prostate cancer, this extensive review and meta-analysis adhered to the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) [13]. For our methodology. The review’s research protocol was registered on the prospero.

Literature search

A comprehensive literature search was performed until April 23, 2024, across various databases including PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar to find relevant articles. The search strategy utilized three primary keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). One keyword set concentrated on androgen therapy, while the other two focused on prostate cancer and heart failure. These keywords were combined using the ‘AND’ operator, without publication date, type, or language restrictions. The search strategy was tailored to fit the query formats of each database (Table 1). To ensure thorough coverage, we also examined the reference lists of pertinent systematic reviews and included studies that met our criteria. Two reviewers independently carried out all process steps, resolving any discrepancies through discussion. Two independent reviewers evaluated each study’s title and abstract to determine their eligibility for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Studies that did not fulfill the established criteria were excluded from further consideration. The full texts of the remaining studies were screened, and those that met the eligibility requirements moved on to the data extraction phase.

Table 1.

The search strategy of Pubmed, Scopus, and Google Scholar

| Search engine | Search strategy | Additional filters | Total results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pubmed | ((“heart“[MeSH Terms] OR “heart“[All Fields] OR “hearts“[All Fields] OR “heart s“[All Fields]) AND (“prostat“[All Fields] OR “prostate“[MeSH Terms] OR “prostate“[All Fields] OR “prostates“[All Fields] OR “prostatic“[All Fields] OR “prostatism“[MeSH Terms] OR “prostatism“[All Fields] OR “prostatitis“[MeSH Terms] OR “prostatitis“[All Fields]) AND (“androgen s“[All Fields] OR “androgene“[All Fields] OR “androgenes“[All Fields] OR “androgenic“[All Fields] OR “androgenicity“[All Fields] OR “androgenized“[All Fields] OR “androgenizing“[All Fields] OR “androgenous“[All Fields] OR “androgens“[Pharmacological Action] OR “androgens“[MeSH Terms] OR “androgens“[All Fields] OR “androgen“[All Fields] OR “virilism“[MeSH Terms] OR “virilism“[All Fields] OR “androgenization“[All Fields])) AND (fha[Filter]) |

February 12,2024 |

462 |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY ( heart ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( prostate ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( androgen )) |

February 12,2024 |

1442 |

| Scholar | allintitle: “heart” “prostate” “androgen” |

February 12,2024 |

30 |

Criteria for selecting studies

To be included in this meta-analysis, studies must meet the following criteria:

Study Design: Included cohort studies as the primary methodology.

Focus of Investigation: Investigated the association between androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and the risk of heart failure.

Investigations that used other types of methodology, were carried out on animals, or involved pathological conditions or other results were excluded. Review articles, commentaries, and editorials were also excluded.

Data extraction and Study quality assessment

Data extraction encompassed four categories: (1) study characteristics (such as authors, location, year, and study type), (2) patient-specific factors (including eligibility criteria for participants and age of prostate cancer), (3) study design (encompassing participant numbers, sampling method, and period), and (4) outcomes (such as heart failure incidence and androgen levels).

The two reviewers mentioned earlier utilized the critical assessment tools provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for cohort studies.

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, we employed STATA 13.1 software, developed by StataCorp LP based in College Station, TX, USA. Our findings were presented as hazard ratios (HR) with a 95% confidence interval, visually represented in a forest plot. We assessed the variability among the included studies using the I2 statistic [14]. and applied the random effects model in instances of notable heterogeneity (I2 > 50%) [15] Additionally, we carried out a sensitivity analysis by systematically excluding individual studies and re-performing the meta-analysis to ensure the robustness of our results. Lastly, we visually inspected funnel plot symmetry and conducted Egger’s regression analysis to examine the possibility of publication bias [16].

Results

Study selection

A comprehensive search was conducted on PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar to find relevant articles. Initially, 1934 articles were identified. After removing 499 duplicates, 1435 unique articles remained. These were screened based on their titles and abstracts, and 77 articles were selected for full-text review. Ultimately, 9 articles meeting the inclusion criteria were included in the systematic review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart

Baseline characteristics

This systematic review encompassed 9 articles involving a total population of 189,045 individuals diagnosed with prostate cancer undergoing Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT). The age range of patients was from a minimum of 65 to a maximum of 81 years. Studies were conducted in multiple countries, including the USA [17, 18], Taiwan [12, 19], Norway [20], South Korea [21, 22], Canada [23], and China [24]. All studies were cohort studies. The primary objective was to evaluate the risk of heart failure in this specific patient population (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the included studies

| Author/reference | Year | Country | Study design | Participants | Mean/median age | Intervention | Covariates adjusted for in HR | Heart failure definition | Study duration | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huei-Ting Tsai(17) | 2017 | USA | Cohort study | 9,772 | 66 | A population-based cohort study was conducted on 9,772 men aged 66 years or older diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer between 2002 and 2011. They received androgen deprivation therapy. | Age, marital status, registry region, PCa stage, comorbidities (Charlson index) | Identified using Medicare claims, based on primary discharge diagnosis or secondary diagnosis with outpatient record. | Median follow-up was 4.55 years. | 10/11 |

| Reina Haque(18) | 2017 | USA | Cohort study | 7,637 | Median: 55.93 | ADT was characterized as a GnRH analog (such as leuprolide, goserelin, or triporelin) with or without an oral antiandrogen (like flutamide, bicalutamide, or nilutamide for combined androgen blockade). Throughout the study duration, ADT antagonists (abarelix and degarelix) were not accessible in the KPSC formulary. | Age, race/ethnicity, Gleason score, PSA level, tumor stage, history of CVD, hypertension, diabetes, Charlson comorbidity score, CVD medications, and in sensitivity analyses, BMI and smoking. | Hospitalization with a primary diagnosis of heart failure using ICD-9/ICD-10 codes. | Follow-up period with an average of 3.4 years for ADT users and 5.3 years for non-users. | 10/11 |

| Hui-Han Kao(12) | 2018 | Taiwan | Cohort study | 1244 | the mean age of the study cohort and comparison cohort was 73.3 and 67.2 years | - | age, urbanization level, geographic location, monthly income, and comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, valvular heart disease, and obesity | Heart failure was identified using ICD-9-CM codes 428.xx. | 1-year follow-up period | 10/11 |

| Rachel B. Forster(19) | 2022 | Norway | Cohort study | 30,923 |

Mean: 67.4 |

The ADT group included patients that received primary treatment with a leutenizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist (buserelin, leuprorelin, goserelin, triptorelin or histrelin) or LHRH antagonists (degarelix or abarelix) within the first year after diagnosis. The treatment group was compared to PCa patients that did not receive ADT within the first year. |

Age, cancer stage, year of diagnosis, education, comorbidity index, and CVD risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, MI, stroke). | Based on diagnostic codes from Norwegian registries. | follow-up: 2.9 years for CVD | 10/11 |

| Do Kyung Kim(20) | 2020 | Seoul, Korea | Cohort study | 61,722 |

Before propensity score matching: ADT (n = 31,579): 72.11 Non-ADT (n = 99,610): 63.73 After propensity score matching: ADT (n = 30,861): 71.87 Non-ADT (n = 30,861):71.87 |

- | Age, history of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and anti-thrombotic use. | identified using the relevant ICD-10 codes for heart failure within the HIRA database. |

● The ADT group had a mean follow-up duration of 3.67 ± 2.52 years. The non-ADT group had a mean follow-up duration of 4.50 ± 2.85 years. |

11/11 |

| Do Kyung Kim (21) | 2021 | Seoul, Korea | Cohort study | 49,090 |

Before exact matching: ADT: 74.57 Non-ADT: 68.82 After exact matching: ADT: 73.31 Non-ADT: 73.31 |

- |

Age History of hypertension Diabetes Dyslipidemia Atrial fibrillation Heart failure Chronic liver disease Chronic kidney disease Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Antithrombotic medication use |

identified using the relevant ICD-10 codes for heart failure within the HIRA database. | The mean follow-up duration for the matched cohort was approximately 3.24 years in the ADT group and 3.39 years in the non-ADT group. | 10/11 |

| Jui-Ming Liu(22) | 2020 | Taiwan | Cohort study | 4335 | median age: 73.0 | A real-world evidence study found that patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) who were treated with second-line hormonal therapy had a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). | diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stable angina, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, peripheral artery disease, and atrial fibrillation. Other covariates included the Charlson Comorbidity Index score, body mass index (BMI), and baseline laboratory results (e.g., creatinine, liver enzymes, hemoglobin, lipid levels). Additionally, the initial stage of prostate cancer (PC), Gleason score, and metastatic sites were considered | Heart failure (HF) in this study is defined as a clinical diagnosis of heart failure that requires hospitalization. | The mean follow-up period for patients receiving second-line hormonal therapy was 9.52 months. | 10/11 |

| Alice Dragomir(23) | 2023 | Canada | Cohort study | 10,785 | Mean for GnRh Antagonist user: 74.1 |

10,201 received a GnRH agonist and 584 received a GnRH Antagonist (degarelix) |

Age Prior cardiovascular disease (CVD) Prior curative treatment (radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy) Maximum androgen blockade) Hypertension Dyslipidemia Diabetes Renal disease Charlson comorbidity score (≥ 4 vs. < 4) Number of prior CVD events (≥ 2 vs. < 2) |

Heart failure (HF) in this study was defined by the following ICD-10 codes: I50 (Heart failure) o I97 (Postprocedural heart failure) o I11 (Hypertensive heart disease with heart failure) |

The study period spanned from January 2012 to December 31, 2016 | 10/11 |

|

Jeffrey Shi Kai Chan(24) “Medical castration” |

2023 | Hong-Kong, china | Cohort study | 6,944 | Median:75.9 | “Medical castration” | age, type of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), and arrhythmias), and use of medications or prior procedures (e.g., radiotherapy, chemotherapy, radical prostatectomy, androgen receptor signalling inhibitors, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, metformin, sulphonylurea | Heart failure (HF) is recorded as a comorbidity in the study based on ICD-9 codes | The median follow-up duration for patients was 3.3 years, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 1.5 to 6.7 years. | 10/11 |

|

Jeffrey Shi Kai Chan(24) “Bilateral-orchiectomy” |

5,359 | “Bilateral-orchiectomy” | ||||||||

|

Jeffrey Shi Kai Chan(24) “Medical castration & Bilateral-orchiectomy” |

1,234 | “Medical castration & Bilateral-orchiectomy” |

Meta-analysis

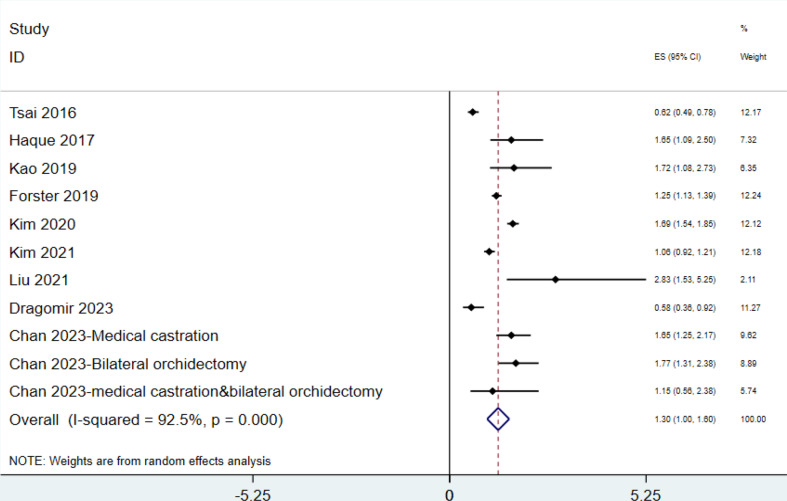

Our meta-analysis evaluated the relationship between androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and heart failure, incorporating data from nine studies with a combined total of 189,045 patients. Using a random-effects model, the overall pooled hazard ratio (HR) was 1.299 (95% CI: 1.003–1.595), showing a significantly elevated risk of heart failure in patients undergoing ADT. High heterogeneity was observed across studies (I² = 92.5%, p < 0.000, χ² = 134.21, df = 10), necessitating subgroup analyses. The study by Forster et al. (2019), conducted in Norway with 30,923 patients, reported a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.250 (95% CI: 1.130–1.390), indicating an increased risk of heart failure associated with ADT. This study was not entered in subgroup analysis, but its findings align with the overall meta-analysis, further supporting the link between ADT and cardiovascular risk (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Association of ADT and the risk of heart failure in patients with prostate cancer(total population)

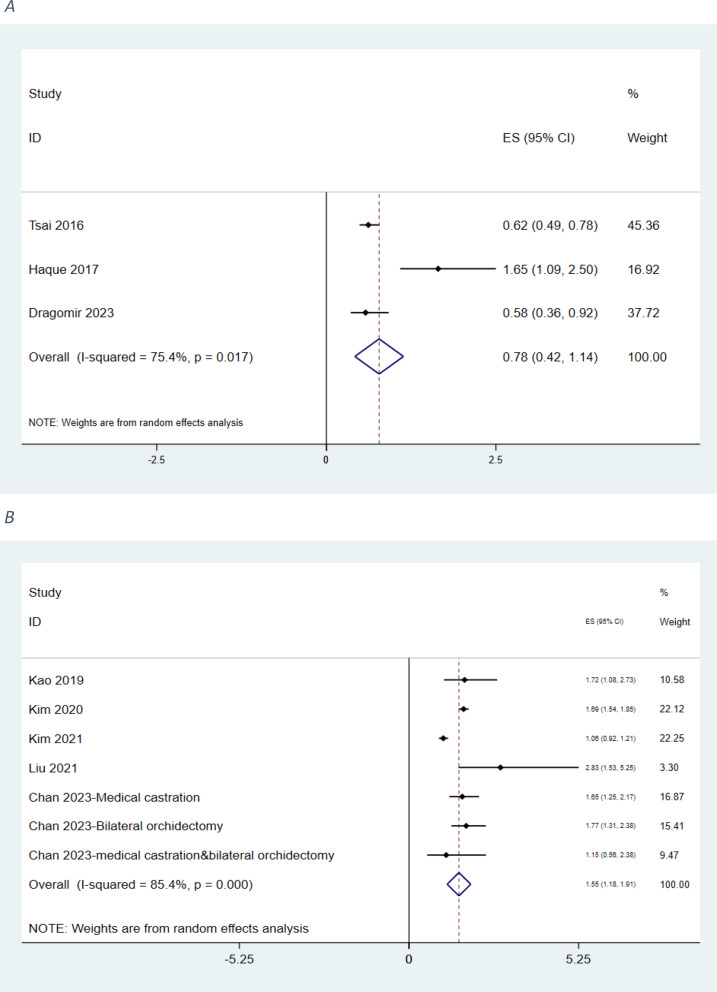

Subgroup analysis: North America and Asia region

The North American subgroup analysis included three studies involving 28,194 patients. Tsai 2016 (n = 9,772) reported an HR of 0.620 (95% CI: 0.490–0.780), Dragomir 2023 (n = 10,785) showed an HR of 0.580 (95% CI: 0.360–0.920), and Haque 2017 (n = 7,637) demonstrated an HR of 1.650 (95% CI: 1.090–2.500). The pooled HR for North American studies was 0.779 (95% CI: 0.421–1.138), with moderate-to-high heterogeneity (I² = 75.4%, p = 0.017), though lower than that of the overall analysis. (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Association of ADT and the risk of heart failure in patients with prostate cancer (A: North-America; B:Asia)

The Asian subgroup analysis included five studies comprising 129,928 patients. Kao 2019 (n = 1,244) reported an HR of 1.720 (95% CI: 1.080–2.730), Kim 2020 (n = 61,722) an HR of 1.690 (95% CI: 1.540–1.850), and Kim 2021 (n = 49,090) an HR of 1.060 (95% CI: 0.923–1.210). Liu 2021 (n = 4,335) demonstrated the highest HR in this subgroup at 2.830 (95% CI: 1.530–5.250). Chan 2023 presented three analyses: medical castration (n = 6,944; HR = 1.650, 95% CI: 1.250–2.170), bilateral orchiectomy (n = 5,359; HR = 1.770, 95% CI: 1.310–2.380), and combined therapy (n = 1,234; HR = 1.150, 95% CI: 0.560–2.380). The pooled HR for Asian studies was 1.545 (95% CI: 1.180–1.910), with high heterogeneity (I² = 85.4%, p < 0.000, χ² = 41.05, df = 6) and a significant subgroup effect (z = 8.30, p < 0.000) (Fig. 3B).

These regional differences may reflect geographic or ethnic variations in ADT-related cardiovascular risk. HRs from the 11 included studies (2016–2023) ranged from 0.58 (Dragomir 2023) to 2.83 (Liu 2021). Protective effects were observed in three studies: Dragomir 2023 (HR = 0.58), Tsai 2016 (HR = 0.62), and Kim 2021 (HR = 1.06). Other studies reported increased risks, with Liu 2021 showing the highest HR (2.83), followed by Chan 2023 (Bilateral Orchiectomy, HR = 1.77) and Kao 2019 (HR = 1.72).

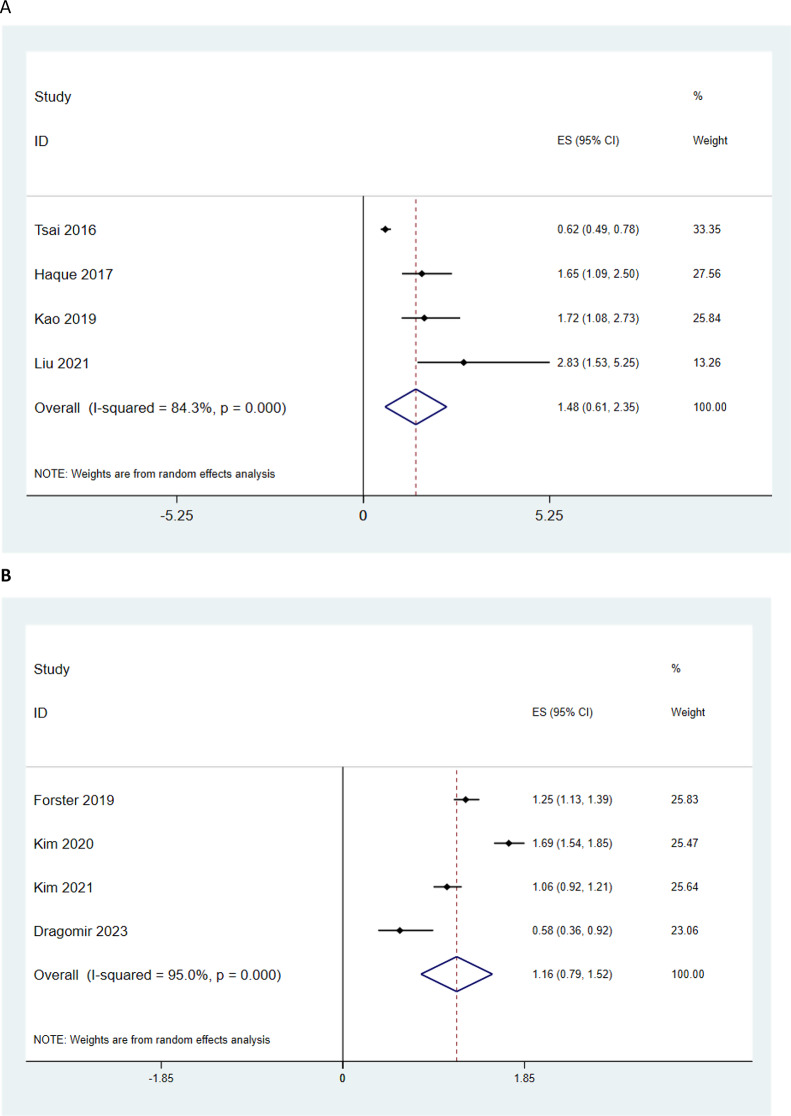

We also analyzed the data based on type of androgen deprivation therapy (For GNRI agonists and GNRH antagonists or GNRH agonists but the results were not significant (Fig. 4A and B).

Fig. 4.

Association of ADT type and the risk of heart failure in patients with prostate cancer (A: GNRI agonists; B: GNRH antagonists or GNRH agonists)

Publication bias

Publication bias was assessed using Begg’s and Egger’s tests. For the overall analysis, significant publication bias was detected, with Begg’s test yielding an adjusted Kendall’s score of -41 (z = -3.19, p = 0.001) and Egger’s test showing a bias coefficient of -3.024 (p = 0.002). In subgroup analyses, no evidence of publication bias was found in the North American subgroup (Begg’s test: z = -0.52, p = 0.602; Egger’s test: bias coefficient = -5.120, p = 0.526). However, significant bias was observed in the Asian subgroup, where Begg’s test indicated a z-score of -2.55 (p = 0.011), and Egger’s test revealed a bias coefficient of -4.225 (p = 0.005). These findings suggest that smaller studies in the Asian subgroup were more likely to report extreme hazard ratios, potentially inflating the pooled estimate.

Discussion

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is a widely accepted treatment approach for patients with metastatic prostate cancer (PC), as well as for those with locally advanced or recurrent disease. However, despite its established efficacy, concerns regarding systemic side effects and, in particular, cardiac complications have been raised [9, 25–27]. Our meta-analysis of nine cohort studies comprising 189,045 patients with PC reveals that ADT is associated with a significant 30% increased risk of heart failure.

Circulating androgen levels have been associated with the development of cardiovascular diseases. Research has shown that in older men, decreased testosterone levels may contribute to the onset of these conditions [28, 29]. Additionally, studies confirm the inverse relationship between free testosterone levels and heart failure in this demographic [29, 30]. The primary objective of androgen deprivation therapy is to reduce androgen levels to castration levels, raising significant concerns about the cardiovascular consequences of this treatment modality [9]. Despite a significant body of research investigating the association between ADT and cardiovascular events, a notable knowledge gap persists regarding the potential link between ADT and the elevated risk of heart failure [12].

Several studies have confirmed the relationship between ADT and an elevated risk of heart failure. A matched cohort study conducted by Kao et al. [12] compared patients with prostate cancer who received ADT with those who did not. The one-year follow-up results showed that heart failure occurred significantly more frequently in patients treated with ADT. Furthermore, A study published by Haque et al. in 2017 followed up on 7,637 patients with localized prostate cancer who underwent active surveillance. Of these patients, approximately 30% (2,170 patients) received ADT. The follow-up analysis revealed that, in patients without a history of cardiovascular disease, ADT significantly increased the risk of heart failure. Moreover, the study found that patients with a history of cardiovascular disease were at increased risk of arrhythmia and conduction disorders [18].

These findings align with our meta-analysis; however, some studies have reported results that contradict our conclusions. For instance, two studies by Kim et al., published in consecutive years, yielded outcomes that differ from ours. In their 2021 study, 131,189 patients with prostate cancer were divided into ADT and non-ADT groups. Contrary to our findings, the authors discovered that ADT did not increase cardiovascular risks and was associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular diseases, cardiovascular interventions, and cerebrovascular diseases [20]. In their 2022 study, the researchers found no link between ADT and the need for cardiovascular interventions in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease, according to their study’s results [21].

Some studies have attempted to refine their analyses by distinguishing between different types of ADT methods (e.g., medical vs. surgical) [24], medications (e.g., GnRH agonists vs. antagonists) [23], or treatment strategies (e.g., intermittent vs. continuous) [17] For instance, Dragomir et al. found that GnRH antagonists were linked to a lower risk of heart failure in patients with a history of cardiovascular disease compared to GnRH agonists. Among patients without prior cardiovascular disease, the GnRH antagonist was associated with a lower risk of ischemic heart disease but a higher risk of arrhythmia [23]. Another study by Tsai et al. reported that intermittent androgen deprivation therapy was linked to a lower risk of heart failure compared to continuous androgen deprivation therapy, leading the authors to consider intermittent therapy a safer option for elderly patients with prostate cancer [17].

In a recent study, Chan et al. explored the relationship between underlying diseases and the risk of significant cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with prostate cancer undergoing ADT. The study revealed that patients with prostate cancer receiving ADT and a history of heart failure, myocardial infarction, or arrhythmia were significantly more likely to have significant cardiovascular comorbidities [24].

While the importance of examining systemic complications related to ADT in prostate cancer patients has gained increasing recognition, a critical knowledge gap persists regarding the relationship between ADT and heart failure. To address this gap, we conducted this meta-analysis. Notwithstanding, further high-quality research is essential to fully understand the impact of ADT on heart failure risk in prostate cancer patients, particularly in identifying high-risk subgroups and developing targeted interventions to reduce this risk.

Based on the meta-analysis that was conducted on nine studies, the following results were obtained in the two regions of Asia and North America:

Asia subgroup analysis.

In Asian studies, a stronger relationship between androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and increased risk of heart failure was observed. Several studies such as Kao (2019) and Liu (2021) have reported a significant increase in risk. Different treatment methods, such as medical drugs or bilateral orchiectomy, showed similar results.

North American subgroup analysis.

In North American studies, conflicting results have been reported regarding the effect of ADT on heart failure. Some studies, such as Tsai (2016) and Dragomir (2023), have indicated a protective effect, while studies such as Haque (2017) have shown an increased risk. These inconsistencies may be related to methodological differences or study population characteristics.

According to the data and results of the meta-analysis, further studies are needed in both Asia and North America, but the reasons and priorities are different for each region. The need for additional studies in Asia is more important due to high heterogeneity, higher relative risk, and publication bias (EGGERs test and Beggs test). Also in North America, due to contradictory HR (protective effect in Tsai 2016, Dragomir 2023 in contrast to harmful effect in Haque 2017) and limited sample size, additional studies are needed.

Conclusion

ADT is associated with an increased risk of heart failure, with the magnitude of this risk appearing greater in Asian populations compared to North American populations. These regional differences may reflect underlying geographic, ethnic, or healthcare-related factors influencing cardiovascular outcomes. The presence of publication bias, particularly in the Asian subgroup, highlights the need for cautious interpretation of these findings and underscores the importance of conducting large-scale, methodologically thorough studies to better understand the cardiovascular risks associated with ADT.

Author contributions

A.A.K screen, writing, table; R.P screen, writing, table; A.S.S screen, writing, table; SH.T search, screen, writing, table; M.M screen, table; R.K screen, table, quality assessment; R.D writing, table; M.V writing, table; M.SH table; S.S screen, table; N.D mentor; M.N analysis; revision: M.M-F.B.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Amir Alinejad Khorram, Reyhaneh Pourasgharian and Ali Samadi Shams contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Niloofar Deravi, Email: niloofarderavi@sbmu.ac.ir.

Mahdyieh Naziri, Email: nazirimahdyieh@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen J, Zhang D, Yan W, Yang D, Shen B. Translational bioinformatics for diagnostic and prognostic prediction of prostate cancer in the next-generation sequencing era. BioMed research international. 2013;2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Dy GW, Gore JL, Forouzanfar MH, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C. Global burden of urologic cancers, 1990–2013. Eur Urol. 2017;71(3):437–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong MC, Goggins WB, Wang HH, Fung FD, Leung C, Wong SY, et al. Global incidence and mortality for prostate cancer: analysis of temporal patterns and trends in 36 countries. Eur Urol. 2016;70(5):862–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crawford ED. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. Urology. 2003;62(6):3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Bach C, Pisipati S, Daneshwar D, Wright M, Rowe E, Gillatt D, et al. The status of surgery in the management of high-risk prostate cancer. Nat Reviews Urol. 2014;11(6):342–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahinian VB, Kuo Y-F, Gilbert SM. Reimbursement policy and androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(19):1822–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu J-R, Duncan MS, Morgans AK, Brown JD, Meijers WC, Freiberg MS, et al. Cardiovascular effects of androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer: contemporary meta-analyses. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(3):e55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Kim J, Freeman K, Ayala A, Mullen M, Sun Z, Rhee JW. Cardiovascular impact of androgen deprivation therapy: from basic biology to clinical practice. Curr Oncol Rep. 2023;25(9):965–77. 10.1007/s11912-023-01424-2. Epub 2023 Jun 5. PMID: 37273124; PMCID: PMC10474986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Sturgeon KM, Deng L, Bluethmann SM, Zhou S, Trifiletti DM, Jiang C, et al. A population-based study of cardiovascular disease mortality risk in US cancer patients. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(48):3889–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kao HH, Kao LT, Li IH, Pan KT, Shih JH, Chou YC, et al. Androgen Deprivation Therapy Use Increases the Risk of Heart Failure in Patients With Prostate Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;59(3):335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group* t. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(2):105–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sterne JA, Harbord RM. Funnel plots in meta-analysis. stata J. 2004;4(2):127–41. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai H-T, Pfeiffer RM, Philips GK, Barac A, Fu AZ, Penson DF, et al. Risks of serious toxicities from intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation therapy for advanced prostate cancer: a population based study. J Urol. 2017;197(5):1251–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haque R, UlcickasYood M, Xu X, Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Tsai H-T, Keating NL, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk and androgen deprivation therapy in patients with localised prostate cancer: a prospective cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(8):1233–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forster RB, Engeland A, Kvåle R, Hjellvik V, Bjørge T. Association between medical androgen deprivation therapy and long-term cardiovascular disease and all‐cause mortality in nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2022;151(7):1109–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DK, Lee HS, Park J-Y, Kim JW, Ha JS, Kim JH, et al. Does androgen-deprivation therapy increase the risk of ischemic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in patients with prostate cancer? A nationwide population-based cohort study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2021;147:1217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim DK, Lee HS, Park J-Y, Kim JW, Hah YS, Ha JS, et al. editors. Risk of cardiovascular intervention after androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer patients with a prior history of ischemic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations; 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu JM, Lin CC, Chen MF, Liu KL, Lin CF, Chen TH, et al. Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events among second-line hormonal therapy for metastatic castration‐resistant prostate cancer: A real‐world evidence study. Prostate. 2021;81(3):194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dragomir A, Touma N, Hu J, Perreault S, Aprikian AG. Androgen deprivation therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with prostate cancer based on existence of cardiovascular risk. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21(2):163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan JSK, Lee YHA, Hui JMH, Liu K, Dee EC, Ng K, et al. Long-term prognostic impact of cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy: a population‐based competing risk analysis. Int J Cancer. 2023;153(4):756–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duivenvoorden WC, Margel D, Subramony Gayathri V, Duceppe E, Yousef S, Naeim M, et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone exacerbates cardiovascular disease in the presence of low or castrate testosterone levels. Basic Translational Sci. 2024;9(3):364–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gómez Rivas J, Fernandez L, Abad-Lopez P, Moreno-Sierra J. Androgen deprivation therapy in localized prostate cancer. Current status and future trends. Actas Urol Esp (Engl Ed). 2023;47(7):398–407. English, Spanish. 10.1016/j.acuroe.2022.08.009. Epub 2022 Aug 5. PMID: 37667894. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Reiss AB, Gulkarov S, Pinkhasov A, Sheehan KM, Srivastava A, De Leon J, et al. Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer: Focus on Cognitive Function and Mood. Medicina. 2023;60(1):77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder PJ, Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Matsumoto AM, Stephens-Shields AJ, Cauley JA, et al. Lessons from the testosterone trials. Endocr Rev. 2018;39(3):369–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Njoroge JN, Tressel W, Biggs ML, Matsumoto AM, Smith NL, Rosenberg E, et al. Circulating androgen concentrations and risk of incident heart failure in older men: the cardiovascular Health study. J Am Heart Association. 2022;11(21):e026953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao D, Guallar E, Ballantyne CM, Post WS, Ouyang P, Vaidya D, et al. Sex hormones and incident heart failure in men and postmenopausal women: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J Clin Endocrinol Metabolism. 2020;105(10):e3798–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript.