Abstract

Background

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death in children and adolescents, with a significant concentration in low and middle-income countries. Previous research has identified disparities in cancer incidence and mortality based on a country’s level of development. The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region comprises of countries with heterogeneous income and development levels. This study aims to investigate whether discrepancies in cancer incidence and mortality among children and adolescents exist in countries within the MENA region.

Materials and methods

Data on cancer incidence and mortality were drawn from the Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) 2019 for all malignant neoplasms (including non-melanoma skin cancers). The analysis was restricted to children and adolescents aged less than 20 years. Mortality- to-Incidence ratios (MIR) were calculated as a proxy measure of survival for each cancer type and country and Spearman’s correlation coefficient measured the association between socio-demographic index (SDI), incidence rates, mortality rates, and MIR.

Results

In 2019, cancer incidence in the MENA region was 4.82/100,000 population, while mortality rate was 11.65/100,000 population. Cancer incidence and mortality was higher among males compared to females. A marked difference was observed in cancer-related mortality rates between low-income and high-income countries. MIR was higher in low-income countries, particularly for males and specific cancer types such as liver, colon and rectum, brain and central nervous system (CNS) cancers, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma among others. A negative correlation was observed between a country’s SDI and MIR (-0.797) and SDI and mortality rates (-0.547) indicating that higher SDI corresponds to lower MIR and lower mortality rates.

Conclusion

These findings highlight the need for evidence-based interventions to reduce cancer-related mortality and disease burden among children and adolescents, particularly in low-income countries within the region and for cancer types with the highest mortality rates. Additionally, efforts should focus on establishing registries to provide up-to-date national data on cancer incidence and mortality in countries within the region.

Keywords: Incidence, Mortality rate, Mortality-to-incidence ratio, Socio-demographic index, Childhood cancer, MENA region

Introduction

Globally, an estimated 429,000 children and adolescents below the age of 19 develop cancer each year [1]. Developing and less developed countries, owing to their substantial young populations, account for over 80% of these cases [2]. Alarmingly, the cure rate for childhood cancer drops to just 30% in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), compared to over 80% in high-income countries (HICs) [1]. Moreover, despite hosting more than two-thirds of the world’s population and a significant portion of cancer cases, LMICs contribute to just 6.2% of the global financial expenditures on cancer [3]. Recognizing this critical issue, the World Health Organization (WHO) has set a global survival target of 60% for all children with cancer, aiming to save one million additional lives by 2030 [4].

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is responsible for approximately 10% of all global pediatric cancer cases [5]. In fact, for children under age 15 cancer ranks as the second leading cause of death, in Jordan, Egypt, and Lebanon, while it stands as the third and fourth leading cause of death in Iran and Turkey [6]. Notably, the MENA region, especially its LMICs, bears a disproportionate cancer burden, exacerbated by political conflicts, and the additional challenge of a rapidly growing pediatric population [7, 8]. Despite similar sociocultural contexts, cancer incidence rates vary considerably among and within Arab nations [9].

Cancer registries are recognized as a crucial element for countries aiming to mitigate and manage the increasing burden of cancer. These registries are essential for collecting data that helps identify emerging trends and formulate effective health policies. In the MENA region, however, cancer registration is highly variable and faces numerous challenges [10]. Gulf nations like the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar have developed robust population-based cancer registries. However, countries like Syria, Yemen, and Iraq, which are affected by political instability and conflict, struggle with their cancer registration efforts [11]. Additionally, in Jordan and Lebanon, the large number of refugees makes it difficult to keep cancer registries up to date for everyone.

For some countries in the region healthcare systems have been adversely affected by political instability, conflicts, and forced displacements over the past two decades [12]. Disparities in cancer incidence may result from unequal access to healthcare facilities, limited surveillance and screening programs, inadequate healthcare infrastructure, and late diagnoses, all of which could affect the reporting and diagnosis of cancers. Other causes are linked to unsatisfactory control of risk factors, inadequate treatment services, financial constraints, and population growth [13, 14]. Addressing these issues and conducting cancer monitoring and research are crucial for developing effective national and regional cancer control programs in the MENA region to mitigate the disproportionate cancer burden [15, 16].

In this paper, we aim to present an overview of the trends in the cancer-related incidence and cancer-related mortality rates, as well as investigate the cancer-related survival rates of children and adolescents in different countries within the MENA region. Furthermore, we investigate the association between a country’s level of development and its cancer survival.

Materials and methods

Definition of MENA region countries

The MENA region comprises 21 countries. As of 2019, the GBD provides incidence and mortality rate data on the following countries within the MENA region – Afghanistan; Algeria; Bahrain; Egypt, Iran; Iraq; Jordan; Kuwait; Lebanon; Libya; Morocco; Oman; Qatar; Saudi Arabia; Sudan; Syria; Tunisia; Turkey; United Arab Emirates (UAE); Palestine; Yemen. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Countries within the MENA region. AFG: Afghanistan, ALG: Algeria, BAH: Bahrain, EGY: Egypt, IRN: Iran, IRQ: Iraq, JOR: Jordan, KUW: Kuwait, LBN: Lebanon, LBY: Libya, MOR: Morocco, OMN: Oman, PAL: Palestine, QAT: Qatar, SAU: Saudi Arabia, SUD: Sudan, SYR: Syria, TUN: Tunisia, TUR: Turkey, UAE: United Arab Emirates, YEM: Yemen

Data source

The data for this study were drawn from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study for the year 2019. GBD provides comprehensive estimates for the burden of 359 diseases and injuries and 84 risk factors across various parameters, including age, gender, region, and 204 countries and territories.

The present paper focused on analyzing cancer incidence and mortality patterns among children and adolescents in the MENA region countries. Therefore, our analysis was restricted to:

-

i.

All types of malignant neoplasms (including non-melanoma skin cancers), excluding benign neoplasms.

-

ii.

Population aged 0–19 years (children and adolescents as per WHO categorization [17])

-

iii.

Countries within the MENA region.

Incidence and mortality rates for cancer (level 3 causes), from 1990 to 2019 were downloaded from the Global Health Data Exchange query tool (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool). Further details on the GBD’s calculation of incidence and mortality rates can be found elsewhere [18]. These rates are expressed per 100,000 populations and pertain only to incident cases of malignant neoplasms (including non-melanoma skin cancers) and exclude benign neoplasms. Additionally, data on Socio-Demographic index (SDI) for MENA region countries was obtained from GBD 2019 [19]. The SDI, developed by the GBD, is a composite indicator that measures a region’s development status and is strongly correlated with health outcomes. The SDI is based on three indices:

Total fertility rate under the age of 25.

Mean education for those ages 15 and older.

Lag distributed income per capita.

SDI is the geometric mean of abovementioned indicators. GBD calculates country-wise SDI and publishes it publicly. In this analysis, we have used SDI values published by GBD for MENA region countries.

Data analysis

To determine the leading type of cancer in the MENA region, ranks were calculated for all cancer types within the region. The mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) was calculated by dividing cancer-related mortality rates by cancer-related incidence rates. We explore the MIR, a valuable metric for revealing disparities among cancers and regions [15, 20]. Here MIR values are used as a proxy measure for survival rates, as many studies have demonstrated their close association with 5-year survival rates [21].

Changes in cancer-related incidence, mortality, and MIR from 1990 to 2019 were calculated using the following formula for percent change:

|

For Table 1; Fig. 2, and Fig. 3, MENA countries were categorized based on the World Bank’s 2022 classification into lower-income countries (LIC), lower-middle-income countries (LMIC), upper-middle-income countries (UMIC) and high-income countries (HIC) [22].

Table 1.

Incidence, mortality and mortality-to-incidence ratio (MIR) across MENA region countries, 1990–2019

| 1990 | 2019 | % Change during 1990–2019 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence (/100,000) |

Mortality (/100,000) |

MIR | Incidence (/100,000) |

Mortality (/100,000) |

MIR | Incidence (%) | Mortality (%) | MIR (%) | |

| Low-income economies | |||||||||

| Yemen | 13.72 | 5.86 | 0.43 | 11.64 | 4.81 | 0.41 | -15.18 | -17.86 | -3.04 |

| Afghanistan | 26.64 | 13.79 | 0.52 | 18.01 | 8.87 | 0.49 | -32.38 | -35.71 | -5.02 |

| Sudan | 22.07 | 9.47 | 0.43 | 16.35 | 6.36 | 0.39 | -25.92 | -32.8 | -9.32 |

| Syria | 22.13 | 8.25 | 0.37 | 18.79 | 5.61 | 0.3 | -15.12 | -31.99 | -19.84 |

| Lower middle-income economies | |||||||||

| Palestine | 20.35 | 7.02 | 0.35 | 16.21 | 4.65 | 0.29 | -20.37 | -33.72 | -16.81 |

| Egypt | 14.46 | 7.11 | 0.49 | 12.26 | 4.21 | 0.34 | -15.23 | -40.72 | -29.94 |

| Morocco | 7.7 | 3.62 | 0.47 | 8.8 | 2.82 | 0.32 | 14.27 | -22.04 | -31.7 |

| Algeria | 16.01 | 6.87 | 0.43 | 14.68 | 3.91 | 0.27 | -8.35 | -43.08 | -37.76 |

| Iran | 22.91 | 8.66 | 0.38 | 23.05 | 5.36 | 0.23 | 0.62 | -38.1 | -38.62 |

| Tunisia | 12.09 | 4.47 | 0.37 | 11.84 | 2.52 | 0.21 | -2.04 | -43.66 | -42.43 |

| Upper middle-income economies | |||||||||

| Iraq | 23.65 | 8.84 | 0.37 | 18.4 | 5.39 | 0.29 | -22.21 | -38.99 | -21.66 |

| Libya | 14.86 | 6.13 | 0.41 | 13.96 | 4.32 | 0.31 | -6.08 | -29.51 | -24.94 |

| Jordan | 16.58 | 5.47 | 0.33 | 19.25 | 4 | 0.21 | 16.13 | -26.92 | -36.97 |

| Turkey | 25.96 | 10.83 | 0.42 | 24.99 | 5.3 | 0.21 | -3.73 | -51.06 | -49.16 |

| Lebanon | 15.18 | 5.91 | 0.39 | 27.65 | 4.92 | 0.18 | 82.21 | -16.71 | -54.24 |

| High-income economies | |||||||||

| United Arab Emirates | 13.75 | 5.99 | 0.44 | 12.7 | 3.72 | 0.29 | -7.63 | -37.9 | -32.64 |

| Kuwait | 27.03 | 6.37 | 0.24 | 21.79 | 3.24 | 0.15 | -19.42 | -49.22 | -36.86 |

| Bahrain | 11.41 | 4.89 | 0.43 | 15.02 | 3.41 | 0.23 | 31.72 | -30.34 | -47.09 |

| Oman | 11.61 | 4.17 | 0.36 | 18.75 | 3.51 | 0.19 | 61.48 | -15.76 | -47.91 |

| Qatar | 12.31 | 4.75 | 0.39 | 18.18 | 3.16 | 0.17 | 47.59 | -33.35 | -54.81 |

| Saudi Arabia | 6.63 | 3.18 | 0.48 | 11.37 | 2.25 | 0.2 | 71.4 | -29.31 | -58.75 |

| MENA region | 18.79 | 7.86 | 0.42 | 16.59 | 5.04 | 0.3 | -11.71 | -35.9 | -27.27 |

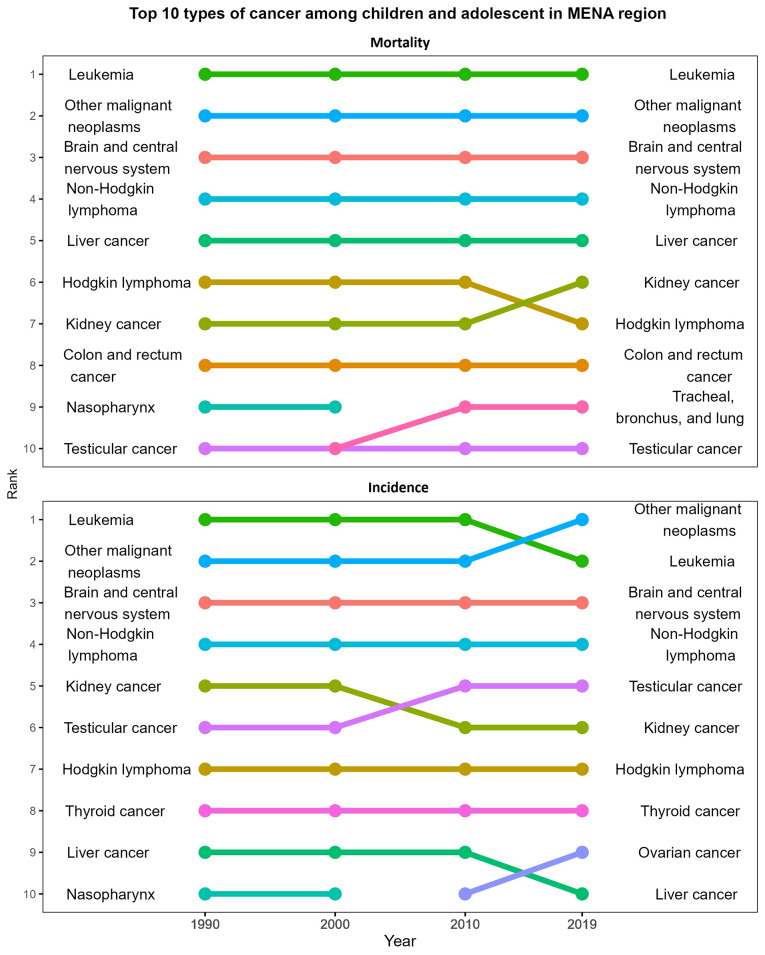

Fig. 2.

Type of cancers among children with the highest incidence and mortality rates in the MENA region, 1990–2019

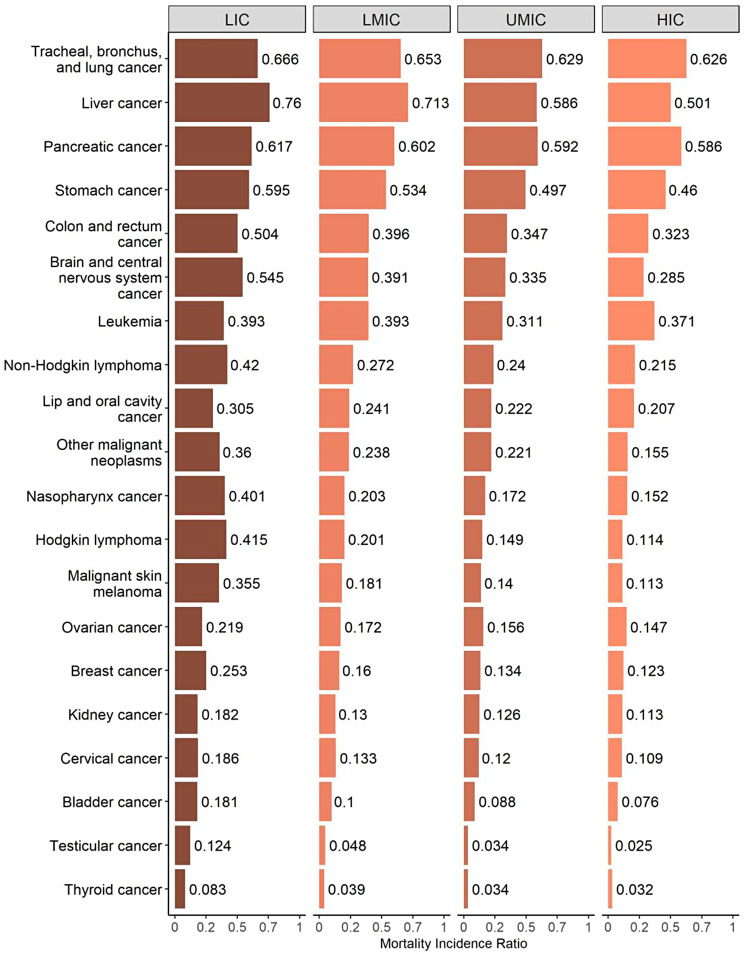

Fig. 3.

Gender and age differential in cancer-related Mortality-to-Incidence Ratio across MENA region countries, 2019. LIC: Low Income Countries, LMIC: Low-Middle Income Countries, UMIC: Upper-Middle Income Countries, HIC: High Income Countries

Shapiro Wilk test was performed to test the normality of the data on death rates, incidence rates, MIRs, and SDIs. Since data were not normally distributed, we used Spearman’s correlation to assess the association between SDIs and the different measures, considering p-values of < 0.05. Both empirical analyses and visualizations were performed using the R software [23].

Results

In 2019, cancer incidence in the MENA region was 11.65/100,000 population, while mortality rate was 4.82/100,000 population. The 0–1 year age group accounted for less than 9% of all cancer mortalities among those aged 0–19 years. The proportion of cancer cases increased with advancing age. The gender disparity is also evident in cancer incidence and mortalities. The share of cancer incidence and mortality was higher among males compared to females (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cancer mortality and incidence rates by age and gender in the MENA Region, 2019

| Incidence per 100,000 | Morality per 100,000 | |

|---|---|---|

| Rate (95% Uncertainty Interval)) | 11.65 (9.96,13.24) | 4.82 (4.04,5.47) |

| Distribution by age group in total incidence and mortality rate (%) | ||

| Less than 1 year | 10.28 | 8.77 |

| 1–4 | 20.72 | 17.26 |

| 5–9 | 22.26 | 24.69 |

| 10–14 | 20.31 | 22.50 |

| 15–19 | 26.43 | 26.78 |

| Share of children (0–9 years) | 53.26 | 50.72 |

| Share of adolescents (10–19 years) | 46.74 | 49.28 |

| Distribution by gender in total incidence and mortality rate (%) | ||

| Male | 54.38 | 55.45 |

| Female | 45.62 | 44.54 |

Leukemia, brain and CNS cancers, and other malignant1 cancers have consistently remained the top three types of cancer for both in terms of incidence and mortality among children and adolescents since 1990. The top 10 leading causes of cancer-related mortality have remained unchanged, with the only exception being the emergence of tracheal, bronchus and lung cancers, replacing nasopharynx cancer since 2000. Furthermore, since 2010, ovarian cancer has also appeared in the top 10 high incidence cancers (Fig. 2).

In 1990, Kuwait and Afghanistan reported the highest cancer incidence rates (27.0/100,000 and 26.6/100,000) respectively. However, by 2019, Lebanon and Turkey had surpassed them, reporting the highest cancer incidence rates in the region (Table 1). Between 1990 and 2019, cancer incidence increased significantly among children and adolescents in Lebanon (82%), Saudi Arabia (71%), Oman (61%), Qatar (47%), Bahrain (32%), Jordan (16%), Morocco (14%), and Iran (0.6%). Conversely, some countries experienced a decline in cancer incidence during the same period, including Afghanistan (-32%%), Sudan (-26%), Iraq (-22%), Palestine (-20%), Kuwait (-19%), Yemen (-15%), Egypt (-15%), Algeria (-8%), UAE (-8%), Libya (-6%), Turkey (-4%), and Tunisia (-2%).

In 1990, Afghanistan and Turkey had the highest cancer-related mortality rates, with 14 and 11 deaths per 100,000 populations, respectively. However, over the years, mortality rates due to cancer decreased across all countries in the MENA region. Nevertheless, Afghanistan still had the highest cancer-related mortality (8.87 per 100,000) in 2019, followed by Sudan (6.36 per 100,000). The countries that showed the most substantial decline in cancer-related mortality rates between 1990 and 2019 were Turkey (-51%), Kuwait (-49%), Tunisia (-43%), Algeria (-43%) and Egypt (-41%).

Similarly, MIR declined across all countries in the MENA region during this period. A high MIR suggests poor survival rates. In 2019, countries with the highest MIRs were Afghanistan (0.49), Yemen (0.41), Sudan (0.39), Egypt (0.34), Morocco (0.32), Libya (0.31), and Syria (0.30).

Gender disparities in MIRs were observed across all income categories, with males having higher MIRs than females, indicating that females had better cancer-related survival rates than males (Fig. 3). This gender difference was most pronounced in LMICs. Across all income groups, MIRs increased with age, with the lowest rates in the 0–1-year age group and the highest in the 15 to 19-year age group. The absolute difference in MIR between LICs and HICs was highest in the 10 to 14-year age group (0.236), followed by the 15 to 19-year age group (0.225), 5 to 9-year age group (0.177), 1 to 4-year age group (0.174) and lowest in the 0 to 1 year age group (0.141).

Differences in MIR were also apparent when considering specific cancer types by income groups (Fig. 4). The largest difference in MIR between LMICs and HMICs was observed for Hodgkin lymphoma (0.301), followed by liver cancer (0.259), nasopharynx cancer (0.249), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (0.205). Conversely, the difference in MIR between LMICs and HMICs in MIR was smallest for tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer.

Fig. 4.

Cancer-related Mortality-to-Incidence Ratio by type of cancer across MENA region countries, 2019. LIC: Low Income Countries, LMIS: Low-Middle Income Countries, UMIC: Upper-Middle Income Countries, HIC: High Income Countries

Association between the socio-demographic index and MIR, incidence rates, and mortality rates in different countries within the MENA region

There was a significant negative association between SDI and MIR of all cancers combined, with a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r) = − 0.796; p < 0.001 (Fig. 5; Table 3). This negative relationship held true across all countries, indicating that higher SDI values are linked to lower MIRs. Countries with lower SDIs, such as Yemen, Afghanistan, Sudan, Syria, and Iran tended to have higher MIR. However, it is important to note that the UAE stood out as an outlier in this pattern. Despite having similar SDI levels to other countries, the UAE showed higher MIR values. Similarly, Afghanistan showed notably higher MIRs compared to other countries with similar SDI values. Similarly, a negative association exists between SDI and cancer-related death rates (-0.547), and this association was statistically significant. Interestingly, the association between SDI and incidence was not strong and not statistically significant.

Fig. 5.

Socio-demographic index and cancer-related Mortality, Incidence and MIR- across MENA region countries, 1990–2019. AFG: Afghanistan, ALG: Algeria, BAH: Bahrain, EGY: Egypt, IRN: Iran, IRQ: Iraq, JOR: Jordan, KUW: Kuwait, LBN: Lebanon, LBY: Libya, MOR: Morocco, OMN: Oman, PAL: Palestine, QAT: Qatar, SAU: Saudi Arabia, SUD: Sudan, SYR: Syria, TUN: Tunisia, TUR: Turkey, UAE: United Arab Emirates, YEM: Yemen

Table 3.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between SDI and cancer mortality rate, incidence, and MIR

| Correlation coefficient | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| SDI*MIR | -0.796 | < 0.001 |

| SDI*Mortality rate | -0.547 | < 0.001 |

| SDI*Incidence Rate | -0.023 | 0.552 |

Discussion

Leukemia, other malignant cancers, brain and CNS cancers, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma remain the top leading cancer types in both cancer incidence and mortality among children and adolescents in the region since 1990. Research from around the world suggests that leukemia is the most common cancer among children [24–26]. Data from the MENA countries also indicate an upward trend in the incidence of childhood Leukemia [27, 28]. Due to advancements in treatment strategies, the survival rate has risen to as high as 90% in the HICs [29]. Evidence from the Middle East also suggests that with proper treatment, remission rates can reach up to 96% [8]. Yet, Leukemia is the most prevalent cancer among children [25, 30] with higher mortality and relapse rate clustered in developing countries [31]. In response to this, WHO has launched the Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer program with the aim of increasing overall survival rates for six major childhood cancers including leukemia [32].

Between 1990 and 2019, the incidence of cancer increased in several middle and high-income countries in the region including Morocco, Jordan, Lebanon, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. Other studies also suggest an increasing trend in childhood cancer incidence in countries with higher Human Development Index [26] or higher income [25]. Lebanon, in particular had the highest incidence rate in the region, and experienced an 82% increase in cancer incidence between 1990 and 2019. Another study has also highlighted that cancer incidence in Lebanon is increasing for all age groups by 4–5% annually [33].

Interestingly, though cancer incidence rates were higher in LICs, it has declined over time. It is important to consider that a lower reported incidence of cancer in low-income settings may not necessarily indicate a lower number of new cases. In such settings, cancer cases might be underreported due to factors such as limited disease awareness, restricted access to healthcare facilities, insufficient or inadequate cancer screenings, and incomplete registrations [34]. For example, consistent armed conflicts have halted cancer registration in Syria, Yemen, and Libya [10]. In the past decade, Libya has experienced two civil wars, leading to ongoing conflicts between factions vying for military and political power. This environment has not only imposed the challenges of disrupted cancer care on Libyan patients but has also resulted in internal displacement and migration to neighboring or distant countries. Accurately assessing the true cancer burden in Libya is hence challenging, with fluctuating demographics and incomplete cancer patient records resulting in skewed epidemiological estimates [35–37]. Similar effects have been observed in conflict regions such as Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Palestine [38–42]. On the other hand, the increase in cancer incidence in HICs could be attributable to the adequate reporting and diagnosis of cancer cases in these countries due to their advanced healthcare infrastructure [43]. It is worth noting here that Lebanon has maintained a National Cancer Register since 1998. Consequently, the observed rise in cancer incidence rates within the country may partially reflect the registry’s effectiveness in capturing cases that might have previously gone unrecorded or unnoticed. However, these numbers could be inflated relative to the Lebanese population due to cancer cases coming from neighboring countries Syria and Iraq [44].

Children and adolescents have distinct cancer types, biological traits, responses to treatment, and long-term outcomes compared to adults [45–47]. Causes of childhood cancer may range from genetic, inherited, to environmental risk factors [48, 49]. However, the results on causal associations for childhood cancers largely remain inconsistent [26, 50].

Although cancer mortality among children and adolescents decreased in countries across the region between 1991 and 2019, a significant disparity in cancer mortality remains between LICs and HICs. LICs continue to experience higher rates of cancer-related deaths compared to HICs. Additionally, the findings reveal a negative linear relationship between the SDI and MIRs. This relationship underscores the critical role that socio-economic factors play in cancer outcomes. In 1990, when MENA countries shared similar levels of income and development, there was little disparity in MIR values between these countries. However, by 2019, as countries like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, and Oman experienced economic growth, the gap between them widened significantly. The magnitude of this difference is illustrated with MIRs ranging from 0.49 in Yemen to 0.15 in Kuwait in 2019, compared to 0.52 in Afghanistan to 0.24 in Kuwait in 1990.

HICs have witnessed substantial improvements in childhood cancer survival rates due to advancements in medical care. Some specific cancers now boast survival rates as high as 90% [51]. However, it is crucial to note that the majority of children diagnosed with cancer reside in low- and middle-income countries and only about 20–30% of these children survive, in stark contrast to survival rates exceeding 80% in high-income nations [32]. HICs have the capacity to allocate more resources to their healthcare systems, allowing them to offer free or subsidized population-based cancer screening and treatment programs to their residents. Whereas, LICs struggle with multiple challenges, including political instability, malnutrition, and communicable diseases which restrict their ability to provide such resources. For example, a study conducted in the Arab region, revealed a correlation between the availability of radiotherapy machines and a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, as well as its political stability [52].

Interestingly, within HICs, the UAE and Saudi Arabia show higher MIRs compared to other countries from the same economic stratum. These countries possess the resources and capacity to advance their healthcare infrastructure, raising concerns about the relatively lower cancer survival rates. It is worth noting that, beyond resource scarcity, social barriers, and lack of awareness among the population hinder early cancer detection.

The data also reveals significant gender disparities in cancer survival, with males consistently exhibiting higher MIR across all countries. These disparities are most noticeable in LMICs and can be attributed to various factors, including limited healthcare access, differences in early detection and awareness, potential biological influences, and variations in healthcare utilization patterns. Prior research has consistently shown that males are more susceptible to cancer than females [50]. Addressing these gender disparities in cancer survival requires multifaceted strategies, including gender-sensitive healthcare services, and enhanced awareness campaigns targeting males. Additionally, fostering a cultural shift that encourages both genders to prioritize health and engage with healthcare systems is crucial in mitigating gender-based inequities in cancer outcomes.

MIRs were also notably higher in adolescents aged 15–19 compared to younger children across the various income levels. Adolescents show significantly lower survival rates than younger children for many types of cancer [53], a difference attributed to multiple factors. One critical factor is the longer delay in diagnosis, which is influenced by patient and referral delays [54, 55]. For instance, adolescents tend to delay seeking medical attention, as the detection of symptomatic diseases largely depends on self-reporting rather than parental reporting, which is more common in younger children. This delay may be influenced by the unique psychosocial characteristics of adolescents, who might be more hesitant to address symptoms [56, 57].

Additionally, referral delays also contribute, as physicians take longer to refer adolescent patients to specialists, such as oncologists or surgeons, who are equipped to diagnose cancer. Another contributing factor is the lower participation rate of adolescents in clinical trials compared to younger patients [58–61].

Evidence indicates that clinical trial participation is associated with better survival outcomes in pediatric and adolescent cancer patients [61, 62], underscoring the importance of addressing this disparity. Treatment adherence is another challenge for adolescents, as they tend to show poorer compliance with treatment regimens [53]. Biological differences and age-specific treatment regimens further contribute to this adolescent gap in cancer care outcomes [63].

Different survival rates for the same types of cancer between countries could also be indicative of differences in early diagnosis and treatment based on income level. It is a proven fact that early detection and prompt initiation of treatment significantly improve cancer patients’ chances of survival [64]. Delays in diagnosis and treatment are often associated with lower parental education levels and individual socioeconomic status [65]. Therefore, even within countries with high national incomes, certain population subgroups such as migrants and expatriates, may have lower income levels, thereby increasing their vulnerability to healthcare disparities. Gulf countries are particularly susceptible to such health inequalities due to the substantial influx of expatriate populations with lower socioeconomic status. An in-depth understanding of the determinants contributing to delays in diagnosis and treatment is essential for customized and tailor-made policies that ensure equal access to early healthcare services for all residents, regardless of their origin or socioeconomic status.

Our paper also explored variations in cancer survival across different types of cancers. Notably, the differences in MIR were more pronounced for certain cancers, including liver cancer, Hodgkin lymphomas, and malignant melanomas, and less so for leukemia. This may be because, while delays in diagnosis have been associated with poor outcomes in some solid tumors [66], prompt diagnosis plays a less critical role in leukemia, a disseminated disease involving the blood, where early detection does not necessarily equate to a localized neoplasm. Studies on pediatric acute leukemia have shown no significant link between delay intervals and event-free survival [67–69]. Also, treatment options are more advanced in HICs, allowing for complex surgeries—like hepatic resection and liver transplantation for liver cancer [70]—and greater access to targeted therapies or immunotherapies with reduced financial strain on patients, which enhances treatment adherence and survival rates.

Acknowledging the emerging burden of cancer, a few countries in the region have initiated diverse strategies to address this challenge and prevent exposure to specific cancer-causing agents in the region. While some small-scale studies have delved into the study of risk factors and the diagnosis and treatment of childhood cancer in the region, most have focused on childhood leukemia [8, 12, 65]. Nevertheless, there remains much to study regarding public awareness on early childhood cancer, barriers to accessing healthcare, and the evaluation of cancer screening and treatment programs in the region. The lack of national and regional spending on research and development, and the unavailability of up-to-date cancer registry data are imperative in the effort to reduce the cancer burden in the region [10, 16]. Many countries in the region lack a national guideline for cancer control policies [71].

Clinical and public health implications

The persistent high incidence and mortality rates of leukemia, brain cancers, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma highlight an urgent need for improved early detection and treatment strategies. The disparities in cancer mortality rates between HICs and LICs reveal that socio-economic factors play a significant role in health outcomes, necessitating targeted public health interventions to address these inequities. In particular, the higher MIRs observed in HICs such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia, despite their advanced healthcare infrastructure, call for an examination of healthcare access, awareness, and cultural attitudes towards early diagnosis and treatment seeking, and treatment adherence. Furthermore, the higher MIRs in adolescents highlight the need for age-appropriate health education and support mechanisms that encourage timely healthcare engagement. Finally, the lack of comprehensive cancer registries and national guidelines across the region indicates a pressing need for coordinated efforts to enhance data collection, increase public awareness about childhood cancer, and establish evidence-based cancer control policies, ultimately aiming to mitigate the current cancer burden in the MENA region.

Limitations

A limitation of the present study is the inability to present actual survival rates; instead, we used MIRs as proxy measures for survival rates. However, prior research suggests MIRs are a fairly accurate predictor of 5-year survival rates [21, 72]. Moreover, current findings relied on GBD estimations because of the lack of accurate data on cancer incidence and mortality rates in the region. While several countries in the region have population-based cancer registries, comprehensive documentation of all malignancies and cancer mortality data remains either scarce or incomplete [10]. While it is well-established that both genetic and environmental factors strongly influence cancer incidence and mortality [50, 73], one limitation of the current study is the inability to evaluate this relationship due to data unavailability. Despite these limitations, the present study establishes a baseline understanding of childhood cancer in the region, providing a foundation for more in-depth clinical epidemiological investigations aimed at uncovering the underlying cause of cancer among children and adolescents.

Conclusion

This study highlights the complex interplay of socio-economic, healthcare, and demographic factors influencing cancer incidence and mortality among children and adolescents in the MENA region. The data underscore an urgent need for targeted interventions to bridge survival disparities across income levels and reduce the rising cancer burden. Incidence rates of childhood cancers, particularly leukemia, have notably increased in several middle- and high-income MENA countries. While improvements in diagnosis and reporting infrastructure in high-income countries contribute to these observed trends, underreporting and limited access to diagnostic facilities in low-income settings likely obscure the true incidence rates, especially in regions impacted by political instability. The presence of significant gender- and age-based disparities in cancer outcomes further emphasizes the need for comprehensive public health strategies that prioritize early detection, equitable healthcare access, and robust cancer registry systems.

The survival gaps among adolescents, often related to diagnostic delays, low clinical trial participation, and suboptimal treatment adherence, reflect an age-specific vulnerability within cancer care that requires age-appropriate resources and support systems. Moreover, disparities in MIRs between high-income countries in the region, such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia, signal that economic status alone does not guarantee optimal cancer outcomes, and underline the importance of dismantling social barriers to healthcare utilization. The region’s scarce national cancer control policies, insufficient research funding, and lack of up-to-date registry data further compound these challenges, impeding efforts to monitor and mitigate the cancer burden.

The need for robust, region-wide strategies is clear. National cancer guidelines, increased investment in research, and more accurate cancer registries are essential to understanding and addressing the region’s unique challenges. Such efforts could improve early detection, increase public awareness, and ultimately narrow the survival gaps that weigh on children and adolescents with cancer in the MENA region.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- MENA

Middle East and North Africa

- WHO

World Health Organization

- UAE

United Arab Emirates

- LMIC

Low-Middle income country

- HIC

High income country

- LIC

Low-income country

- GBD

Global Burden of Disease

- SDI

Socio demographic index

- MIR

Mortality incidence ratio

Author contributions

“BS, AS and RZ conceptualized the study, AS conducted the analysis, BS, AS and RZ interpreted the results. AS wrote the initial draft, BS, AS and RZ read, reviewed, and finalized the final manuscript”.

Funding

No funding was used for this study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent statement

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Other uncategorized cancers.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lam CG, Howard SC, Bouffet E, Pritchard-Jones K. Science and health for all children with cancer. Science. 2019;363:1182–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White Y, Castle VP, Haig A. Pediatric oncology in developing countries: challenges and solutions. J Pediatr. 2013;162:1090–1. 1091.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goss PE, Lee BL, Badovinac-Crnjevic T, Strasser-Weippl K, Chavarri-Guerra Y, St Louis J, et al. Planning cancer control in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:391–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. CureAll framework: WHO global initiative for childhood cancer: increasing access, advancing quality, saving lives. World Health Organization; 2021.

- 5.Rodriguez-Galindo C, Friedrich P, Alcasabas P, Antillon F, Banavali S, Castillo L, et al. Toward the cure of all children with Cancer through Collaborative efforts: Pediatric Oncology as a global challenge. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3065–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mojen LK, Rassouli M, Eshghi P, Sari AA, Karimooi MH. Palliative Care for Children with Cancer in the Middle East: a comparative study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:379–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Znaor A, Eser S, Anton-Culver H, Fadhil I, Ryzhov A, Silverman BG, et al. Cancer surveillance in northern Africa, and central and western Asia: challenges and strategies in support of developing cancer registries. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Mulla NA, Chandra P, Khattab M, Madanat F, Vossough P, Torfa E, et al. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the Middle East and neighboring countries: a prospective multi-institutional international collaborative study (CALLME1) by the Middle East Childhood Cancer Alliance (MECCA). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:1403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salim EI, Moore MA, Al-Lawati JA, Al-Sayyad J, Bazawir A, Bener A, et al. Cancer epidemiology and control in the arab world - past, present and future. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdul-Sater Z, Shamseddine A, Taher A, Fouad F, Abu-Sitta G, Fadhil I, et al. Cancer Registration in the Middle East, North Africa, and Turkey: Scope and challenges. JCO Glob Oncol. 2021;7:1101–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdul-Sater Z, Mukherji D, Adib SM, Shamseddine A, Abu-Sitta G, Fadhil I, et al. Cancer registration in the Middle East, North Africa, and Turkey (MENAT) region: a tale of conflict, challenges, and opportunities. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1050168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Hadad SA, Al-Jadiry MF, Al-Darraji AF, Al-Saeed RM, Al-Badr SF, Ghali HH. Reality of pediatric cancer in Iraq. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(Suppl 2):S154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magrath I, Steliarova-Foucher E, Epelman S, Ribeiro RC, Harif M, Li C-K, et al. Paediatric cancer in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e104–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah SC, Kayamba V, Peek RM, Heimburger D. Cancer Control in Low- and Middle-Income countries: is it time to consider screening? J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Arnold LD, Barnoya J, Gharzouzi EN, Benson P, Colditz GA. A training programme to build cancer research capacity in low- and middle-income countries: findings from Guatemala. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamadeh R, Borgan S, Sibai A. Cancer Research in the Arab World: a review of publications from seven countries between 2000–2013. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2017;17:e147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.World Health Organization. Adolescent health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1. Accessed 5 Nov 2024.

- 18.Force LM, Abdollahpour I, Advani SM, Agius D, Ahmadian E, Alahdab F, et al. The global burden of childhood and adolescent cancer in 2017: an analysis of the global burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1211–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. (GBD 2019) Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) 1950–2019. Seattle, United States of America: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). 2020. 10.6069/D8QB-JK35

- 20.Chen W-J, Huang C-Y, Huang Y-H, Wang S-C, Hsieh T-Y, Chen S-L, et al. Correlations between mortality-to-incidence ratios and Health Care disparities in Testicular Cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;17:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi E, Lee S, Nhung BC, Suh M, Park B, Jun JK, et al. Cancer mortality-to-incidence ratio as an indicator of cancer management outcomes in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries. Epidemiol Health. 2017;39:e2017006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2022. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 5 Feb 2023.

- 23.R Core Team. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miranda-Filho A, Piñeros M, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Monnereau A, Bray F. Epidemiological patterns of leukaemia in 184 countries: a population-based study. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5:e14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Y, Deng Y, Wei B, Xiang D, Hu J, Zhao P, et al. Global, regional, and national childhood cancer burden, 1990–2019: an analysis based on the global burden of Disease Study 2019. J Adv Res. 2022;40:233–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang J, Chan SC, Ngai CH, Lok V, Zhang L, Lucero-Prisno DE, et al. Global incidence, mortality and temporal trends of cancer in children: a joinpoint regression analysis. Cancer Med. 2023;12:1903–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.AL-Hashimi MMY. Incidence of Childhood Leukemia in Iraq, 2000–2019. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2021;22:3663–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jastaniah W, Essa MF, Ballourah W, Abosoudah I, Al Daama S, Algiraigri AH et al. Incidence trends of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Saudi Arabia: increasing incidence or competing risks? Cancer Epidemiol. 2020;67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Pui CH, Yang JJ, Hunger SP, Pieters R, Schrappe M, Biondi A, et al. Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Progress through collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2938–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnston WT, Erdmann F, Newton R, Steliarova-Foucher E, Schüz J, Roman E. Childhood cancer: estimating regional and global incidence. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021;71(Pt B):101662. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Abdelmabood S, Fouda AE, Boujettif F, Mansour A. Treatment outcomes of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a middle-income developing country: high mortalities, early relapses, and poor survival. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2020;96:108–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. WHO Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer: an overview. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/a-future-for-children/booklet-global-initiative-for-childhood-cancer-2-november-2020.pdf?sfvrsn=3ec028f2_1. Accessed 6 Nov 2024.

- 33.Shamseddine A, Saleh A, Charafeddine M, Seoud M, Mukherji D, Temraz S et al. Cancer trends in Lebanon: a review of incidence rates for the period of 2003–2008 and projections until 2018. Popul Health Metr. 2014;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Ward ZJ, Yeh JM, Bhakta N, Frazier AL, Atun R. Estimating the total incidence of global childhood cancer: a simulation-based analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:483–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zarmouh A, Almalti A, Alzedam A, Hamad M, Elmughrabi H, Alnajjar L et al. Cancer incidence in the middle region of Libya: data from the cancer epidemiology study in Misurata. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2022;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Ismail F, Elsayed AG, Garawani I, El, Abdelsameea E. Cancer incidence in the Tobruk area, eastern Libya: first results from Tobruk Medical Centre. Epidemiol Health. 2021;43:e2021050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erashdi M, Al-Ani A, Mansour A, Al-Hussaini M. Libyan cancer patients at King Hussein Cancer Center for more than a decade, the current situation, and a future vision. Front Oncol. 2023;12:1025757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saab R, Jeha S, Khalifeh H, Zahreddine L, Bayram L, Merabi Z, et al. Displaced children with cancer in Lebanon: a sustained response to an unprecedented crisis. Cancer. 2018;124:1464–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devi S. Cancer drugs run short in the Gaza Strip. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alwan N, Kerr D. Cancer control in war-torn Iraq. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:291–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mansour R, Amarin JZ, Al-Ani A, Al-Hussaini M, Mansour A. Palestinian patients with Cancer at King Hussein Cancer Center. Front Oncol. 2022;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Sahloul E, Salem R, Alrez W, Alkarim T, Sukari A, Maziak W, et al. Cancer Care at Times of Crisis and War: the Syrian example. J Glob Oncol. 2016;3:338–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends - an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Basbous M, Al-Jadiry M, Belgaumi A, Sultan I, Al-Haddad A, Jeha S et al. Childhood cancer care in the Middle East, North Africa, and West/Central Asia: a snapshot across five countries from the POEM network. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021;71(Pt B):101727. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Norris RE, Adamson PC. Challenges and opportunities in childhood cancer drug development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:776–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gajjar A, Packer RJ, Foreman NK, Cohen K, Haas-Kogan D, Merchant TE. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2013 blueprint for research: central nervous system tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1022–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pui CH, Carroll WL, Meshinchi S, Arceci RJ. Biology, risk stratification, and therapy of pediatric acute leukemias: an update. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:551–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spycher BD, Lupatsch JE, Zwahlen M, Röösli M, Niggli F, Grotzer MA, et al. Background ionizing radiation and the risk of childhood cancer: a census-based nationwide cohort study. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:622–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuhlen M, Taeubner J, Brozou T, Wieczorek D, Siebert R, Borkhardt A. Family-based germline sequencing in children with cancer. Oncogene. 2019;38:1367–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spector LG, Pankratz N, Marcotte EL. Genetic and nongenetic risk factors for childhood cancer. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62:11–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hudson MM, Link MP, Simone JV. Milestones in the curability of pediatric cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2391–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mousa AG, Bishr MK, Mula-Hussain L, Zaghloul MS. Is economic status the main determinant of radiation therapy availability? The arab world as an example of developing countries. Radiother Oncol. 2019;140:182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Desandes E. Survival from adolescent cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:609–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Veneroni L, Mariani L, Lo Vullo S, Favini F, Catania S, de Pava MV, et al. Symptom interval in pediatric patients with solid tumors: adolescents are at greater risk of late diagnosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:605–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dang-Tan T, Trottier H, Mery LS, Morrison HI, Barr RD, Greenberg ML, et al. Determinants of delays in treatment initiation in children and adolescents diagnosed with leukemia or lymphoma in Canada. Int J Cancer. 2009;126:1936–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morgan S, Davies S, Palmer S, Plaster M. Sex, drugs, and Rock ‘n’ roll: caring for adolescents and young adults with Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4825–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abrams AN, Hazen EP, Penson RT. Psychosocial issues in adolescents with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:622–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aristizabal P, Winestone LE, Umaretiya P, Bona K. Disparities in Pediatric Oncology: the 21st Century Opportunity to improve outcomes for children and adolescents with Cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educational Book. 2021;41:e315-e326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Barrett NJ, Rodriguez EM, Iachan R, Hyslop T, Ingraham KL, Le GM, et al. Factors associated with biomedical research participation within community-based samples across 3 National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers. Cancer. 2020;126:1077–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aristizabal P, Singer J, Cooper R, Wells KJ, Nodora J, Milburn M, et al. Participation in pediatric oncology research protocols: Racial/ethnic, language and age-based disparities. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1337–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, Camitta BM, Gaynon PS, Winick NJ, et al. Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005: a report from the children’s oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1663–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Winestone LE, Getz KD, Rao P, Li Y, Hall M, Huang Y-SV, et al. Disparities in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML) clinical trial enrollment. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60:2190–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bleyer A. The adolescent and young adult gap in cancer care and outcome. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2005;35:182–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dang-Tan T, Franco EL. Diagnosis delays in childhood cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:703–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abdelkhalek E, Sherief L, Kamal N, Soliman R. Factors associated with delayed cancer diagnosis in Egyptian children. Clin Med Insights Pediatr. 2014;8:39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Röllig C, Kramer M, Schliemann C, Mikesch JH, Steffen B, Krämer A, et al. Does time from diagnosis to treatment affect the prognosis of patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia? Blood. 2020;136:823–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baker JM, To T, Beyene J, Zagorski B, Greenberg ML, Sung L. Influence of length of time to diagnosis and treatment on the survival of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a population-based study. Leuk Res. 2014;38:204–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gupta S, Gibson P, Pole JD, Sutradhar R, Sung L, Guttmann A. Predictors of diagnostic interval and associations with outcome in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:957–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lopez-Garcia YK, Valdez-Carrizales M, Nuñez-Zuno JA, Apodaca-Chávez E, Rangel-Patiño J, Demichelis-Gómez R. Are delays in diagnosis and treatment of acute leukemia in a middle-income country associated with poor outcomes? A retrospective cohort study. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2024;46:366–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Su CC, Chen BS, Chen HH, Sung WW, Wang CC, Tsai MC. Improved trends in the mortality-to-incidence ratios for Liver Cancer in Countries with High Development Index and Health expenditures. Healthcare. 2023;11:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rahim HFA, Sibai A, Khader Y, Hwalla N, Fadhil I, Alsiyabi H, et al. Non-communicable diseases in the arab world. Lancet. 2014;383:356–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Asadzadeh Vostakolaei F, Karim-Kos HE, Janssen-Heijnen MLG, Visser O, Verbeek ALM, Kiemeney LALM. The validity of the mortality to incidence ratio as a proxy for site-specific cancer survival. Eur J Public Health. 2010;21:573–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wiemels J. Perspectives on the causes of childhood leukemia. Chem Biol Interact. 2012;196:59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.