Abstract

Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) are a common finding in patients with surgically repaired congenital heart defects including transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA). While often asymptomatic, PVCs can sometimes lead to palpitations, dyspnea, and hemodynamic compromise, requiring therapeutic intervention. The arterial switch operation is the preferred treatment for D-TGA, but these patients have a 2% incidence of ventricular arrhythmias and 1% incidence of sudden cardiac death post-operatively. Though radio-frequency ablation is an effective option for treating outflow ventricular arrhythmias, little data is available on its use in the post-arterial switch D-TGA population. This case report describes a successful catheter ablation of frequent PVCs originating from the left ventricular summit region in a 9-year-old child with a history of arterial switch repair for D-TGA and frequent monomorphic PVCs, highlighting the challenges and considerations in managing ventricular arrhythmias in this complex anatomical setting.

Keywords: Premature ventricular complex (PVC), TGA, Ablation, Elecroanatomical mapping, ASO

Introduction

Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) aren’t an uncommon presentation in patients with structural heart disease, including those with a history of surgically repaired congenital heart diseases. While PVCs are often asymptomatic, in some cases they can lead to palpitations, dyspnea, and even hemodynamic compromise, necessitating therapeutic intervention [1].

Complete transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA) represents approximately 5–8% of congenital cardiac malformations but accounts for 25% of deaths from congenital heart disease in the first year of life [2]. The arterial switch operation is the intervention of choice for those patients when the anatomy and the left ventricular hemodynamics are favorable. Incidence of ventricular arrhythmia in those patients after arterial switch operation reaches 2% with incidence of sudden cardiac death 1%3.

While radio-frequency ablation has emerged as an effective treatment for outflow ventricular arrhythmia (VA), there is limited data on the approach and outcomes in the post-surgical TGA population.

This case report describes a successful catheter ablation of frequent PVCs originating from the left ventricle (LV) summit region in a child with a history of arterial switch operation (ASO) for D-TGA. The challenges and considerations in managing ventricular arrhythmias in such complex anatomical setting are discussed, providing insights that may guide the management of similar cases.

Case presentation

We report a 9-year-old male child, the third child of consanguineous marriage presenting with a 1-year history of palpitations, shortness of breath and frequent pre-syncopal episodes. The patient had undergone ASO, ASD closure and PDA division for D-TGA at the age of 45 days with uneventful postoperative course. Afterwards he had led a normal life till the onset of the presenting symptoms.

On presentation, he was physically well with a weight of 31 kg and height of 136 cm. Vital signs including oxygen saturation were unremarkable. There were no signs of heart failure.

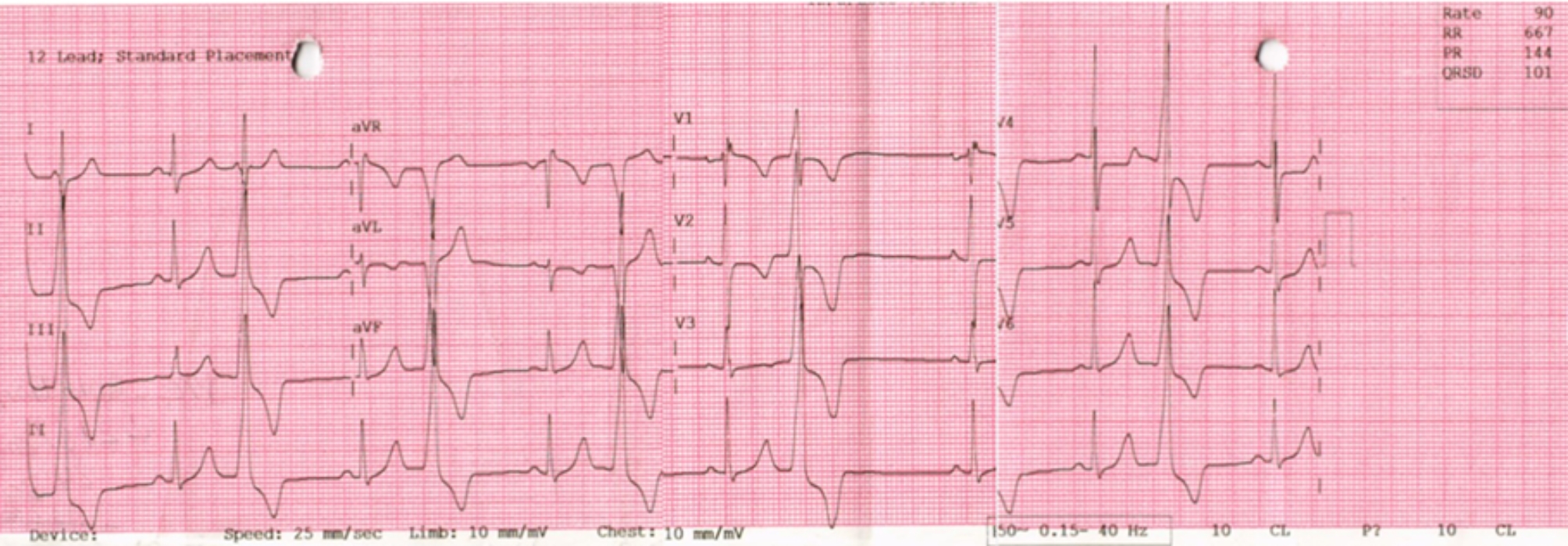

ECG revealed sinus rhythm with frequent monomorphic PVCs displaying a right bundle branch block pattern with inferior axis, a QS pattern in lead I. It was a noteworthy that the maximum deflection index “MDI” was 64% in the pericardial leads(Fig. 1). Ambulatory Holter confirmed the significant burden of the PVCs representing 31% of the total QRS count through 24 h with couplets, triplets and non-sustained VT.

Fig. 1.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a sinus rhythm with frequent monomorphic PVCs (bigeminy)

In order to exclude coronary osteal kink or stenosis which is reported as one of the long-term complications of ASO and might provide an explanation for the emerging complaint, CT heart was done refuting any compromise affecting the coronaries. It also illustrated the position of the re-implanted coronaries in relation to the left ventricle outflow tract (LVOT).

After confirming normal Biventricular function and absences of myocardial fibrosis by CMR, A diagnosis of idiopathic outflow PVCs was adopted with a possible origin from the LV summit area given the ECG criteria.

Due to poor response to medical treatment, an electrophysiology study and catheter ablation were decided after counseling the patient’s family.

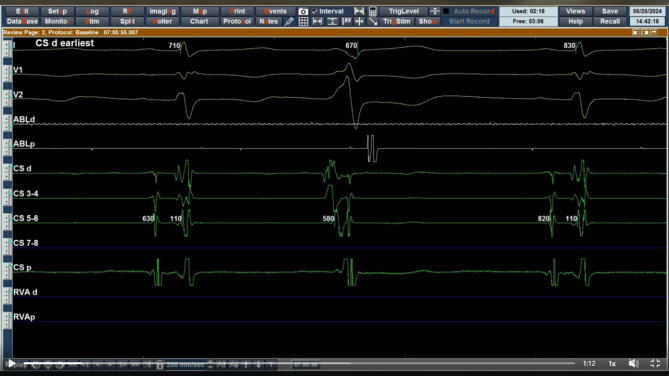

The procedure was done under general anesthesia. Ultrasound guided vascular accesses were obtained. A decapolar catheter was inserted deeply inside the coronary sinus through a 6 F left femoral venous sheath. Importantly, the earliest ventricular activation was observed at the distal CS supporting more the presumed LV summit origin of the PVCs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Intracardiac electrocardiogram showing earliest activation during PVC at CS distal (speed 200 mm/sec)

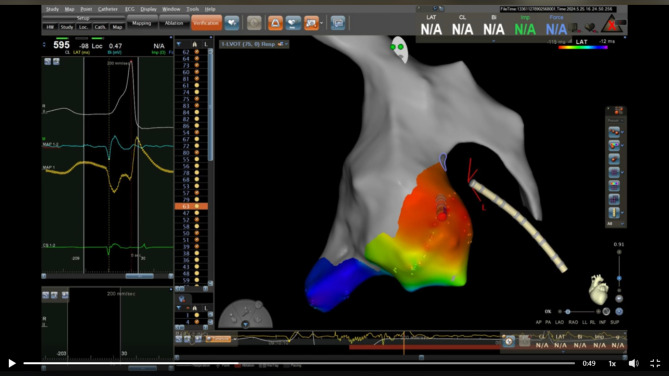

Based on the previously mentioned observations, we started with mapping of LVOT via retrograde approach using an irrigated bidirectional contact force catheter “Ezz-Steer Nav; Biosense Webster; Diamond bar, CA” guided by a 3D mapping system “CARTO® 3 System Version 6 Biosense Webster; Diamond Bar, CA” through an 8 F right femoral arterial sheath after angioraphic confirmation that it could securely accommodate an 8 F sheath.

The detailed activation mapping revealed that the earliest site of ventricular activation was located superior to the left coronary cusp, directly opposite the expected original position of the left main coronary artery in normal population. The signal at this site was found to precede the PVCs on the surface electrocardiography of by 37 milliseconds (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

Intracardiac electrocardiogram (speed 200 mm/sec) showing earliest activation during PVC on ablation catheter at site of ablation

Fig. 4.

Three-dimensional (3D) activation mapping of Aortic root and LVOT showing the earliest activation during PVC above left sided aortic cusp opposite to LV summit

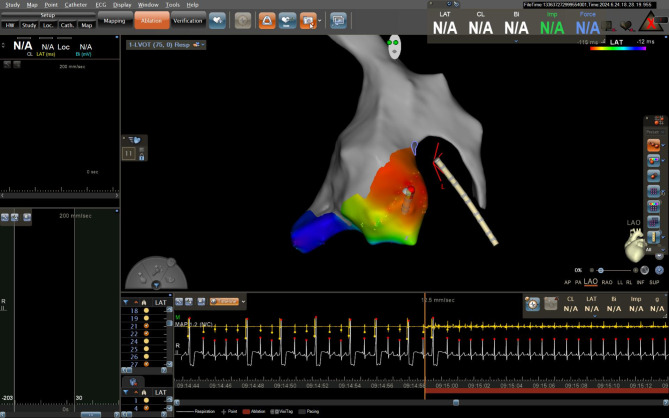

Prior to radio-frequency energy application and in order to confirm a safe distance between the presumed earliest activation area and the site of the re-implanted coronaries, an aortography using a pigtail catheter was done to delineate the re-implanted coronary anatomy and precise position (Fig. 5). Consequently, application of RF energy at 35 watts at the site of the earliest activation led to prompt termination of the PVCs. Waiting time for 30 min was applied with no recurrence of the PVCs (Figs. 6 and 7).

Fig. 5.

A Angiography of aortic root (LAO fluoroscopic view). B X-ray image of RF ablation catheter at site of ablation (LAO fluoroscopic view)

Fig. 6.

Start of ablation with immediate disappearance of PVCs

Fig. 7.

ECG post ablation after 30 min (speed 50 mm/sec)

Discussion

Sustained VA after ASO for D-TGA is a rare but potentially a life-threatening complication. To the best of our knowledge, they are usually related to ischemia, late myocardial infarction from surgery-related coronary stenosis/kinking, closure of a ventricular septal defect, or surgical scars at the aortic root. However, in the absence of these substrates the mechanism underlying the VAs is quite elusive [4].

Comprehensive imaging modalities can provide invaluable assistance in identifying the mechanism of the arrhythmia and guiding the optimal ablation approach, Furthermore, multidisciplinary discussions with pediatric cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons are crucial providing indispensable insights into the complex patient anatomy, previous surgical approaches, and the typical locations of surgical anastomoses.

In our case LV summit origin was suspected as PVCs having an RBBB pattern, a QS pattern in lead I, and MDI of 64% in the precordial leads. Additionally, the earliest ventricular activation during PVCs was at distal CS increased the possibility of LV summit source. This was confirmed by 3D mapping showing the earliest ventricular activation was above left sided aortic cusp opposite the presumed location of the LV summit. Targeting this region during ablation resulted in immediate disappearance of the PVCs.

It is well recognized that the LV summit can be accessed through various approaches, including the left coronary cusp, the LV myocardium beneath the left coronary cusp, the distal coronary sinus, the great cardiac vein, as well as via an epicardial approach with its limitations. Pre-procedural CT imaging not only excludes coronary abnormalities, but also provides critical information regarding the precise location of the re-implanted coronary arteries in relation to the sinotubular junction (STJ). This knowledge, combined with complementary aortography, allowed us to safely target an area that would typically be avoided due to the proximity of the left main coronary ostium.

As previously mentioned, there is a paucity of data regarding ablation of outflow VAs in patients with ASO for D-TGA. Ablation within the aortic root has been previously reported, Krisai and colleagues described a case of VT ablation in a 17-year-old male patient, where successful targeting was achieved from the left coronary cusp and additional ablation from below LCC and from inside the great cardiac vein. In contrast to the current case, their patient had evidence of scar tissue in the aortic root region below the left coronary cusp on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging [5].

Maury and colleagues have also reported a case of sustained outflow monomorphic VT in a 15-year-old boy post ASO with the successful ablation site in the non-coronary sinus of Valsalva, where post-systolic, fractionated potentials were identified during sinus rhythm [6].

Furthermore, Bhaskaran and colleagues described a 30-year-old man with sustained outflow VT that was successfully ablated at the junction of the left and non-coronary cusp, also in an area of fractionated electrograms [7]. Although the presence of late and fractionated potentials in these cases supported surgical scar-mediated reentry as the underlying mechanism, imaging studies did not reveal any scar tissue. Consequently, the possibility of idiopathic or triggered outflow tract VT could not be definitively excluded.

Moreover, Dalili and his companions reported PVCs ablation in 3 patients who had ASO for D-TGA. In 2 of them the ablation was done at Neopulmonary- old aortic root suture line, suggesting that the PVCs may have been related to surgical suture lines [8].

Regarding the mechanism of VA In the present case, the preserved biventricular function and absence of myocardial scarring favored a focal mechanism. However another plausible explanation is that substrate could be related to the coronary button sutures, yet this hypothesis is partially refuted by the absence of any discernible myocardial scarring on the patient’s cardiac MRI, normal voltage mapping and the absence of fractionated or late potentials at the successful ablation site.

Ultimately, the precise electrophysiological mechanism and the relative contributions of the PVCs whether idiopathic against being scar-related or micro-reentrant processes required careful integration of the available anatomical, electrophysiological, and imaging data is essential to develop a comprehensive understanding of the arrhythmia mechanism and guide the most effective therapeutic approach.

Conclusion

In this case report, we describe a successful catheter ablation of PVCs originating from the LV summit region in a child with a history of ASO for D-TGA. This report highlights the importance of a comprehensive, multimodality and multidisciplinary approach in the evaluation and management of VAs in patients with complex congenital heart disease and prior surgical interventions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ASD

Atrial septal defect

- CMR

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging

- CS

Coronary sinus

- CT

Computed tomography

- CT

ECG Electrocardiogram

- GCV

Great cardiac vein

- LV

Left ventricle

- LVOT

Left ventricle outflow tract

- MDI

Maximum deflection index

- PDA

Patent ductus arteriosus

- PVC

Premature ventricular complex

- RV

Right ventricle

- TGA

Transposition of the great arteries

- VA

Ventricular arrhythmia

- VT

Ventricular tachycardia

Author contributions

OK and MA provided the concept of the manuscript. MA and EA wrote the manuscript. AN, EA and ME revised the manuscript. All authors cared for the patient and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethic approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Koester C, Ibrahim AM, Cancel M, Labedi MR. The ubiquitous premature ventricular complex. Cureus. 2020;12(1):e6585. 10.7759/cureus.6585. PMID: 32051798; PMCID: PMC7001138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alakhfash AA, Tamimi OR, Al-Khattabi AM, Najm HK. Treatment options for transposition of the great arteries with ventricular septal defect complicated by pulmonary vascular obstructive disease. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2009;21(3):187–90. 10.1016/j.jsha.2009.06.008. Epub 2009 Aug 5. PMID: 23960571; PMCID: PMC3727366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(14):e91–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khairy P, Clair M, Fernandes SM. Cardiovascular outcomes after the arterial switch operation for d-transposition of the great arteries. Circulation. 2013;127:331–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krisai P, Vlachos K, Tafer N, Cochet H, Iriart X, Sacher F. Ventricular tachycardia in a patient with repaired d-transposition of the great arteries. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2020;7(1):26–9. 10.1016/j.hrcr.2020.10.006. PMID: 33505850; PMCID: PMC7813791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maury P, Hascoët S, Mondoly P, Acar P. French Reflection Group for Congenital/Pediatric Electrophysiology. Monomorphic sustained ventricular tachycardia late after arterial switch for d-transposition of the great arteries: ablation in the sinus of valsalva. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:e174113–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhaskaran A, Campbell T, Trivic I, Tanous DJ, Kumar S. Left ventricular outflow tract ventricular tachycardia late post-arterial switch for d-transposition of the great arteries. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019;5:1096–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalili M, Kargarfard M, Tabib A, Fathollahi MS, Brugada P. Ventricular tachycardia ablation in children. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2023;23(4):99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.