Abstract

Although monotremes diverged from the therian mammal lineage approximately 187 million years ago, they retain various plesiomorphic and/or reptilian‐like anatomical and physiological characteristics. This study examined the morphology of juvenile and adult female reproductive tracts across various stages of the presumptive oestrous cycle, collected opportunistically from cadaver specimens submitted to wildlife hospitals during the breeding season. In adult females, ovaries had a convoluted cortex with follicles protruding from the ovarian surface. While protruding antral follicles were absent from the ovaries of juvenile echidnas, histological analysis identified early developing primordial and primary follicles embedded into the ovarian cortex. The infundibulum epithelial cells of the oviducts were secretory during the follicular phase but not at other stages, the ampulla region was secretory at all stages and is likely responsible for the mucoid layer deposited around the zona pellucida, and the isthmus region of the oviduct appeared to be responsible for initial deposition of the shell coat, as in marsupials. Female echidnas have two separate uteri, which never merge and enter separately into the urogenital sinus (UGS). This study confirmed that both uteri are functional and increase in glandular activity during the luteal phase. In the juvenile uteri, the endometrium was immature with minimal, small uterine glands. A muscular cervical region at the caudal extremity of each uterus, just before the cranial region of the UGS was defined by the absence of glandular tissue in all female echidnas, including the juveniles. There was no evidence of a definitive vaginal region. A clitoris was also detected that possessed a less developed but similar structural (homologous) anatomy to the male penis; urethral ducts while present did not appear to be patent.

Keywords: cervix, monotreme, ovarian follicles, reproductive tract, uterine glands

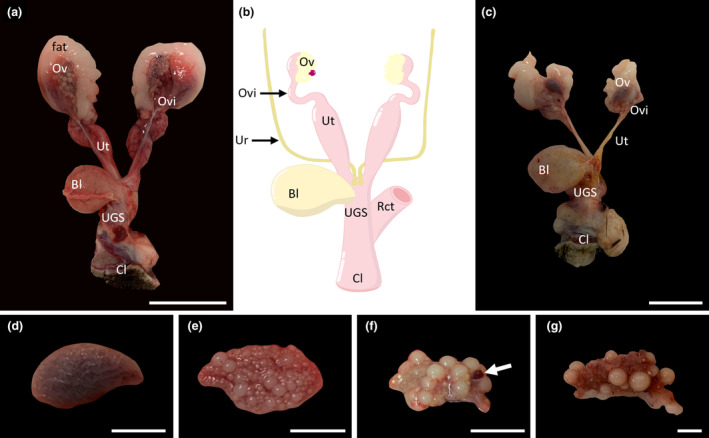

Here we examine for the first time the reproductive anatomy of the juvenile female echidna and the changes in morphology of the adult female echidna across oestrous. We confirmed the presence of two cervices and found no evidence for a vagina. In addition, we identified a small internal clitoris that possessed a similar anatomy to the male echidna penis. Bl, bladder; Cl, cloaca; Cx, cervix; Ov, ovary; Ovi, oviduct; Rct, rectum; UGS, urogenital sinus; Ur, ureter; Ut, uterus. Scale bar = 5 cm.

1. INTRODUCTION

The short‐beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) is one of five extant species of egg laying mammals belonging to the Monotremata, the other members consisting of the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) and three species of the long‐beaked echidna (Zaglossus attenboroughi, Z. bartoni and Z. bruijnii) found only in New Guinea. The short‐beaked echidna is common throughout a diverse range of terrestrial environments, spanning across Australia and the low‐lands of New Guinea (Flannery, 1995). Recent genomic analysis suggests that monotremes diverged from therian mammals around 187 million years ago (Zhou et al., 2021). Characterised as mammals by their capacity to produce milk from mammary gland patches and possession of hair, the monotremes have nevertheless retained and evolved unique anatomical and physiological characteristics that appear to be a mosaic of therian mammals and reptiles (Griffiths, 1979; Hughes & Hall, 1998; Tyndale‐Biscoe & Renfree, 1987).

The reproductive tract of monotremes is characterised by a single orifice, the cloaca, which is used for reproduction, urination and faecal excretion. Unlike therian mammals, monotremes are the only extant mammals that lay (leathery) eggs. Reproductive cyclicity in the echidna appears to be strongly seasonal with breeding typically commencing in June/July and terminating in October (Wallage et al., 2015). In a captive colony of echidnas in which mating and egg deposition was closely monitored, the gestation period was found to be 16–17 days followed by a 10 day egg incubation within a transiently formed pouch (Dutton‐Regester et al., 2021). The pouch young is suckled in the pouch for approximately 55 days before it is deposited in a nursery burrow after which it continues to be nourished by milk before being weaned at approximately 200 days (Rismiller & McKelvey, 2003).

Organogenesis of the monotreme Mullerian ducts have similarities in their morphogenesis but differ in their lack of fusion from therian mammals (Tyndale‐Biscoe & Renfree, 1987). In the majority of eutherians, the embryonic Mullerian ducts fuse together to different degrees giving rise to a diverse range of uterine morphologies; complete fusion of the caudal region of the Mullerian ducts results in a single vagina in the eutheria. In the case of marsupials, the medial migration of the ureters during organogenesis prevents the complete fusion of the uteri and presumptive vagina resulting in the formation of two lateral vaginae (Tyndale‐Biscoe & Renfree, 1987). While there is significant diversity in the morphology of the marsupial female reproductive tract (Tyndale‐Biscoe & Renfree, 1987), they are characterised by the possession of two separate uteri and cervices that open into a single vaginal cul‐de‐sac or vestibule, and which in turn receives two lateral vaginae that open into a urogenital sinus (Renfree & Shaw, 2018). A median vagina (birth canal) may also be present as a permanent or transient structure. Organogenesis of the monotreme reproductive tract shows no level of fusion, such that the Mullerian ducts develop and remain fully distinct with separate ostia opening into the urogenital sinus (Keibel, 1904).

Detailed characterisation and/or histological descriptions of the female monotreme reproductive tract are limited. In his monograph on the echidna, Griffiths (1968) refers to the drawing of Wood Jones (1923) and notes that the female possesses two large infundibular funnels at the start of the oviducts that enclose the ovaries. Although not illustrated by Wood Jones, Griffiths reports the anterior “Fallopian tube” as being convoluted and describes the posterior end of the oviduct as being differentiated to form uteri. However, no further differentiation of the remaining portion of the reproductive tract (e.g. cervix and vagina) is mentioned, except he notes that the uterus communicates “with a long median unpaired urogenital sinus at the level of the entrance of the ureters and of the neck of the bladder.” Apart from these early descriptions of the gross anatomy and line drawings (Augee, 2006; Griffiths, 1968), there is relatively limited and somewhat dated histological descriptions of the echidna ovary and reproductive tract. Some additional, historical characterisation has also been described for the platypus, which noted the presence of ovary, oviducts, uteri, urogenital sinus and clitoris (Home, 1802a; Home, 1802b; Owen, 1868). However, only the left ovary is functional in the platypus (Garde, 1930; Griffiths, 1979; Owen, 1868).

Given the oviparous nature of reproduction in monotremes, it is not surprising to find a significant literature base (although dated) on echidna oogenesis and the egg itself (Flynn & Hill, 1939; Griffiths, 1968; Hill & Hill, 1936). Griffiths (1968) described the echidna ovary as oval in shape and covered on its outer surface by a range of different size follicles; with a germinal epithelium that is thin and “thrown into folds”. These folds of epithelium contain what appear to be oogonia, possibly akin to primordial follicles. Flynn and Hill (1939) recognised three stages of oocyte development based on the relative size of the oocyte and changes in the morphology of the ooplasm, zona pellucida and follicular cell layers. By the time the follicle is mature, it is possible to differentiate two layers of follicular cells, the latter of which was thought to produce the precursor of follicular fluid (Griffiths, 1968). The production of follicular fluid is regarded by Griffiths (1968) as an essential mammalian characteristic as Sauropodian follicles lack follicular fluid.

Following maturation of the oocyte within the ovarian follicle (production of the 1st and 2nd polar bodies and formation of the germinal disc), the oocyte is ovulated and received into the infundibulum of the oviduct. At ovulation, the oocyte is 3–4 mm in diameter. Hill (1941) notes that the infundibular region of the oviduct contains a viscous fluid around the time of ovulation that aids in the transport of the oocyte. The infundibular region of the oviduct is considered to be the likely fertilisation site of the oocyte and the ampulla region where it is coated with a layer of albumen, outside of which a thin shell membrane is deposited. Hill and Hill (1936) and Hill (1941) described the formation of infundibular secretions and albumen layers associated with two epithelial cell types, ciliated non‐secretory and non‐ciliated secretory cells. The ampulla region of the oviduct consists of tall columnar epithelium, which assists with further deposition of the albumen layer. The upper two‐thirds of the ampulla secretes a dense layer of albumen, whereas the lower third a more fluid type of albumen is laid down over this dense layer (Griffiths, 1968). Hill (1941) also noted the presence of another secretion which she described as convoluted glands in the isthmus region of the oviduct and which she suggested may form the basal layer of the egg shell.

By the time the egg passes into uterus it starts to absorb nutritive fluid from the secretory epithelium and reaches its full intrauterine size (14–15 mm in diameter) (Flynn & Hill, 1939). Hill (1941, 1936) described the uterine fine glandular secretions of the platypus which subsequently liquify after being produced by apocrine secretion of uterine epithelium. The shell layers surrounding the oocyte after the commencement of cleavage are porous which enables the exchange of nutritive fluid from maternal uterine sections to the embryo (Frankenberg & Renfree, 2018; Hughes & Carrick, 1978). As pregnancy progresses, more shell layers are deposited in the uterus (Hughes & Carrick, 1978).

While the gross anatomy of the adult female echidna reproductive tract has been well described (reviewed in (Augee, 2006, Griffiths, 1968, Griffiths, 1979) along with historical investigations of ovarian, oviductal and uterine histology (Flynn & Hill, 1939; Griffiths, 1968; Hill & Gatenby, 1926)Hill, 1941, Hill & Hill, 1936), changes in the adult tract during the different stages of the reproductive cycle remain to be documented. Furthermore, no histological descriptions of the juvenile ovary and reproductive tract exist. Similarly, while the presence of a cervical region in echidnas has previously been proposed, but not confirmed (Grützner et al., 2008; Owen, 1868), no further descriptions of either the caudal reproductive tract or the female clitoris are known. Here we present a complete gross and histological description of the female short‐beaked echidna ovary and reproductive tract (adult and juvenile), using tissues collected opportunistically at different stages of their reproductive cycle.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1. Animals

Female echidna reproductive tracts used in this study were collected opportunistically during the breeding season (July–October) from injured echidnas brought into the Currumbin Wildlife Hospital (Currumbin, SE Queensland) and the RSPCA (Wacol, SE Queensland). These animals were severely injured (typically beak fractures from car trauma) and so required euthanasia for the purpose of animal welfare; no echidnas were killed for the purpose of sample collection. Whole reproductive tracts were collected from 8 adult females (average weight 3.99 ± 0.61 kg) and 5 juvenile females (average weight 1.94 ± 0.47 kg) (see Table 1). The tracts were photographed and the length of the tracts and size of the ovaries were determined based off these photographs where possible. The presence of newly ovulated follicles and corpora lutea on ovaries and evidence of any mammary gland activity were noted to define a presumptive stage of the reproductive cycle for each female.

TABLE 1.

Details of the females used in this study.

| Animal number | Stage | Month of euthanasia | Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 112116 | Juvenile | June | 2.5 |

| 70460 | Juvenile | July | 1.6 |

| 99126 | Juvenile | July | 2.3 |

| 103198 | Juvenile | July | NA |

| 1291498 | Juvenile | September | 1.4 |

| Average | 1.94 ± 0.47 | ||

| 99092 | Adult | July | 3.5 |

| 99251 | Adult | July | 4.9 |

| 114449 | Adult | July | 3.5 |

| 1287282 | Adult | August | 3.4 |

| 72951 | Adult | August | 5.0 |

| 1292196 | Adult | September | 3.7 |

| 102493 | Adult | October | 4.2 |

| 75235 | Adult | October | 3.6 |

| Average | 3.99 ± 0.61 |

After examination, reproductive tracts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) or 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF). Tissues fixed in 4% PFA were stored at 4°C overnight, then washed twice with gentle shaking in 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 20 minutes each before storing in 70% ethanol. Sampling of the echidnas conformed with the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Guidelines (2013) and was approved by the University of Queensland Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee (SAFS/317/20 CURRUMBIN/UNIMELB – ANFRA).

2.2. Histology

Gross morphology of each fixed tract was examined and photographed using either a stereomicroscope (Olympus SZX9, Olympus Corporation, Australia) and with the attached camera (Olympus DP25, Olympus Corporation, Australia) or with an iPhone 11 (Apple Inc., USA) before processing for histology. Reproductive tracts were then dissected into smaller sections, separating out the prospective tissue types: ovary, oviduct, uterus, and urogenital sinus (UGS). Tissues were processed for histology at the University of Melbourne Histology platform, embedded in paraffin and serially sectioned at 7 μm. Every second slide was stained with Haematoxylin & Eosin (H&E). Additional representative slides of each tissue type and stage were stained with Mallory's trichrome to further differentiate cellular structures such as epithelial, muscle and connective tissue microanatomy. Microanatomy of histological sections were analysed and captured using an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus Corporation) and Olympus DP70 camera (Olympus Corporation).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Morphology of the reproductive tract

Following removal of the two ovaries from their peritoneal attachment the most notable feature was the presence of a thick layer of surrounding intra‐abdominal adipose tissue apparent in all specimens examined. This gonadal adipose tissue typically occluded direct observation of the infundibular region of the oviduct, although it was possible to grossly observe in adult animals the distinctive convoluted region of oviduct (Figure 1a). There were two swollen vascularised presumptive uterine tubes and what appears to be the supporting mesometrium of the broad ligament (Figure 1a). The uterine tubes extended caudally and opened into the urogenital sinus just below the base of the bladder (Figure 1a). The female bladder emptied via a short urethra directly into the urogenital sinus which subsequently opened caudally in the cloaca which also received the rectum. The muscular cloaca opened externally and in some females, protruding cloacal glands were visible on the cloacal surface (data not shown). Two females had enlarged mammary glands containing mammary gland secretions (milk, data not shown) and what appeared to be a regressing corpus luteum on their ovaries, consistent with eutherian mammals in lactational anoestrus. The two juvenile reproductive tracts that could be measured ranged in length from 92.5 to 153.6 mm with the longest similar to the average length of the adult reproductive tracts (154.4 ± 2.83 mm). However, all juvenile reproductive tracts were underdeveloped with narrow diameter uteri and minimal evidence of vascularisation (Figure 1c).

FIGURE 1.

Overall morphology of the entire female echidna reproductive tract. (a) An adult female reproductive tract, showing well‐developed ovaries, oviducts, uteri, urogenital sinus (UGS) and cloaca. (b) Stylistic diagram of adult female reproductive tract highlighting the main reproductive structures and showing the position of the ureters and rectum relative to the tract. (c) Juvenile reproductive tract showing underdeveloped ovaries and narrow uterine tubes. (d) Morphology of an intact juvenile ovary, showing the smooth, convoluted structure of the ovary. (e) Morphology of an older juvenile showing multiple small and medium sized follicles. (f) Morphology of an intact adult ovary in the early luteal phase; white arrow identifies the location of a corpus luteum; (g): Morphology of an adult ovary in lactational anoestrus showing a reduced number of mature follicles and the convoluted cortex of the ovary. Bl, bladder; Cl, cloaca; Ov, ovary; Ovi, oviduct; Rct, rectum; UGS, urogenital sinus; Ur, ureter; Ut, uterus. Scale bars: (a) & (c) = 5 cm, (d–g) = 1 cm.

Juvenile ovaries (Figure 1d,e) were smaller than those of the adult with an average length of 21.75 ± 1.92 mm and width of 12.25 ± 1.64 mm (n = 2 females) and their smooth convoluted surface contained no obvious protruding follicles in the youngest juveniles (Figure 1d) and only small‐medium sized follicles in the older juveniles (Figure 1e). Mature adult ovaries were larger on average but had a larger variation in length with an average length and width of 22.83 ± 5.43 mm and 12.67 ± 1.07 (n = 3 females), respectively. Adult ovaries showed evidence of large follicles protruding from the surface (Figure 1f,g). In the ovaries which had large developing follicles (3–4 mm diameter; e.g. Figure 1f,g) it was possible to observe what appeared to be “yolk” accumulation and vascularisation of the follicular surface. There was a noticeable reduction of protruding, mature follicles, resulting in a visible ovarian cortex, in the females which were lactating, consistent with anoestrus (Figure 1g).

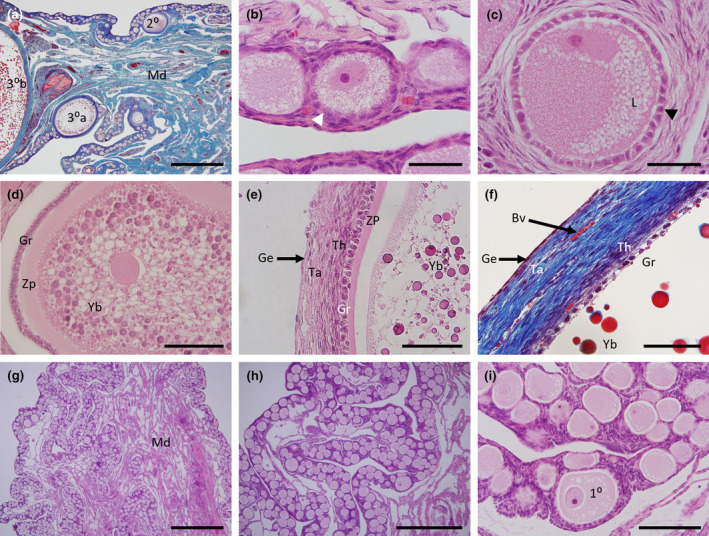

3.2. Ovarian histology

The main body of the ovary consists of a medullary region composed of connective (collagen) tissue which is well vascularised. Surrounding this is a narrow band of cortical tissue containing follicles of different stages of development (Figure 2a). Primordial follicles were surrounded by flattened follicular cells (Figure 2b), while primary follicles were surrounded by cuboidal follicular cells (Figure 2c). These smaller follicular stages were all observed to have multiple lipid vacuoles within their ooplasm (Figure 2b,c). Secondary follicles had a layer of granulosa and thecal cells, a central eosinophilic core and a well‐defined zona pellucida (Figure 2d). Lipid vacuoles observed in primordial and primary follicles increased in size and number in the secondary follicles, which now also contained multiple, distinct yolk bodies (Figure 2d). Tertiary follicles were significantly larger overall, had a zona pellucida that measured approximately 2.9 μm thick and an outer layer of vascularised membrane propria, one cell layer of cuboidal granulosa cells and flattened layers of thecal cells (Figure 2e,f). The structure of the outermost tissue layer surrounding the ovary is consistent with a connective tissue tunica albuginea interspersed with blood vessels surrounded by an outer single layer of germinal epithelium or visceral peritoneum (Figure 2e,f).

FIGURE 2.

Histology of the echidna ovary and follicles. (a) Mallory's stained section of an adult female ovary showing the medulla (blue) with extensive blood vessels (red) and the narrow, convoluted ovarian cortex region containing multiple follicles at different stages of development. Note the presence of an early tertiary follicle (30a) and a partial section of a mature tertiary follicle (30b) on the far left. (b) H&E high power section of primordial follicles. (c) H&E high power section of a primary follicle with cuboidal granulosa cells and multiple lipid vacuoles within the follicle. (d) H&E section of a secondary follicle with numerous lipid bodies (white) and yolk bodies of varying sizes (dark pink). (e) H&E high power section of a mature tertiary follicle showing a layer of cuboidal granulosa cells and flattened thecal cells. (f) Mallory's stained high power section of a mature tertiary follicle showing the same structures as in (e) with the granulosa and thecal cell layers (purple) and surrounding connective tissue (blue) interspersed with red blood vessels and an external germinal epithelium (purple). (g) Low power H&E section of a juvenile ovary showing the medulla surrounded by the convoluted ovarian cortex. (h) H&E section of a juvenile ovary showing abundant follicles within the cortex. (i) High power image of (h) showing morphology of primordial and primary follicles. 10, Primary follicle; 20, Secondary follicle; 30a, Developing tertiary follicle; 30b, Mature tertiary follicle; Ge, Germinal epithelium; Gr, Granulosa cell layer; L, Lipid globules; Md, Medulla region; Ta, Tunica albuginea; Th, Thecal cell layer; Yb, Yolk bodies; Zp, Zona pellucida. Scale bars (a) & (g) = 1 mm, (b), (c) & (i) = 100 μm, (d) = 200 μm, (e) & (f) = 20 μm, (h) = 500 μm.

The microanatomy of the juvenile echidna (Figure 2g–i) was composed of a highly convoluted cortical layer comprised of primordial and primary follicles with no follicles found in the medulla region. There was no evidence of secondary or tertiary follicles in the juvenile ovary (Figure 2g–i).

Two adults had large mature haemorrhagic follicles (Figure 1f). When examined histologically, this structure contained luteal cells interspersed with blood filled spaces, consistent with the later stage of formation of a mature corpus luteum (Figure 3a,b). All adult ovaries examined in this study irrespective of presumptive stage of the reproductive cycle showed evidence of follicles of different stages undergoing atresia (Figure 3c–f). In the earlier stage follicles, the zona pellucida underwent fragmentation and the follicular cells invaded (Figure 3c,d). In later stage atretic follicles, it was possible to observe remnants of granulosa and lipid tissue (Figure 3e,f).

FIGURE 3.

Histology of the corpora lutea and atretic follicles. (a) Section of a whole, mature corpora lutea. (b): High power image of (a) showing large round luteal cells packed densely with blood vessels. (c) Low power image showing size of an atretic early phase follicle. (d) High power image of (c) showing the pale pink staining convoluted fragmentation of the zona pellucida and invasion of the remnant follicular cells. (e) Atretic later phase follicle. (f) High power image of (e) showing remnants of the yolk bodies and granulosa cells. Af, atretic follicle; Fc, follicle cells; Zp, Zona pellucida. Scale bars: (a) & (c) = 1 mm, (b), (d) & (e) = 500 μm, (f) = 100 μm.

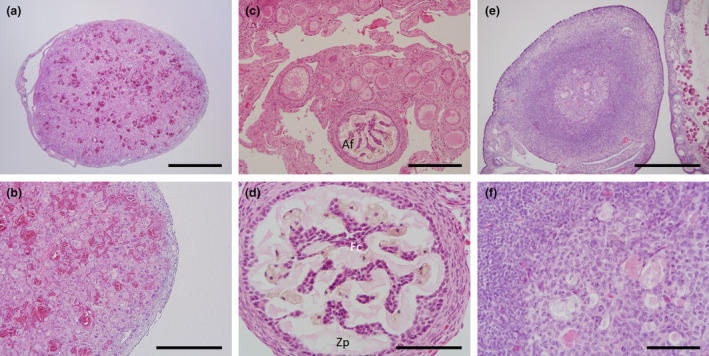

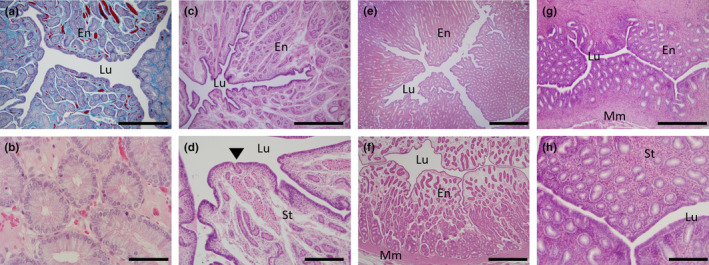

3.3. Oviductal histology

The adult echidna oviduct (Figure 1a) is composed of three distinct sections; the infundibulum (including fimbria), the ampulla and the isthmus. The infundibulum was composed of a large lumen with a simple layer of ciliated, columnar epithelial cells surrounded by extensive connective tissue (Figure 4a,b). The ampulla region was identified by a more defined muscularis with a highly convoluted epithelial layer composed of ciliated and non‐ciliated simple columnar secretory cells, with basophilic nuclei and a heavily vascularised lamina propria (Figure 4c–f). In the lactating females the epithelial cytoplasm of both the infundibulum and ampulla was noticeably reduced relative to the other females examined (e.g. Figure 4b lactating versus Figure 4d,f, non‐lactating). In females in which a corpus luteum had been observed in the ovary (luteal phase), the columnar epithelial cells of both the infundibulum and ampulla had an extended cytoplasm that was composed of large vacuoles (e.g. ampulla Figure 4d). The isthmus region had a reduced epithelial layer folding and thickened muscularis layer (Figure 4g). In addition, presumed shell glands were present surrounding the luminal epithelia near the utero‐tubal junction (Figure 4g,h); these glands had small, circular, basal nuclei with faintly staining cytoplasm consisting of multiple granules (Figure 4h).

FIGURE 4.

Histology of the adult oviduct. (a) H&E section of the three cross‐sections of the oviductal infundibulum region. (b) H&E high power image of the infundibulum showing the ciliated epithelium. (c) H&E transverse section of the ampulla region. (d) H&E high power image of the infundibulum epithelia from a recently ovulated female showing numerous secretory non‐ciliated goblet cells (pale staining) interspersed among the ciliated epithelial cells. (e) Mallory's stained sagittal section of the ampulla showing the high degree of vascularization (red) within the connective tissue (blue). (f) H&E high power image of the ampulla region with basal columnar, ciliated epithelium with no secretory vacuoles. (g) H&E section of the isthmus region with the appearance of the presumed shell glands; and thickened muscularis layer. (h) H&E high power image of a shell gland from the isthmus region. Bv, blood vessel; Lu, lumen; Mu, muscularis layer; Sg, shell glands. Scale bars: (a), (c), (e) & (f) = 1 mm, (b), (d), (f) & (h) = 50 μm.

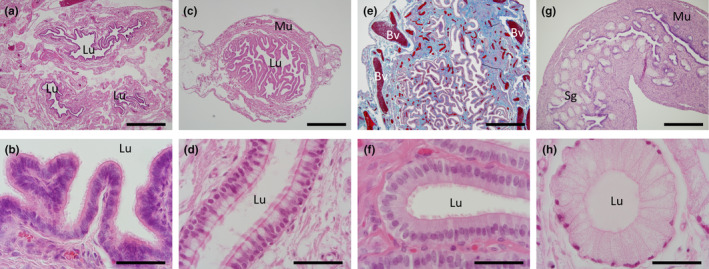

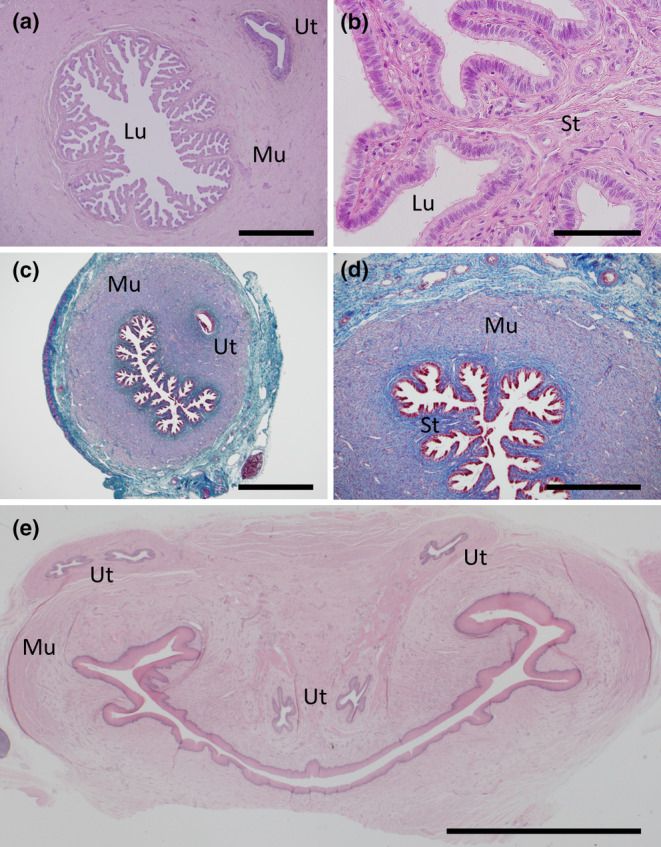

3.4. Uterine histology

Compared to that of the oviduct the uterus was characterised by the presence of distinctive uterine glands composed of simple columnar epithelium within the vascularised endometrial stroma (Figure 5), in addition to a well‐defined and thickened myometrium (Figure 5f,g). All cycling females examined had numerous endometrial glands dispersed evenly throughout the stroma (Figure 5a,b). In contrast, the endometrium of the lactating females had a greatly reduced number of overall smaller sized uterine glands that had a reduced height columnar epithelium relative to cycling females and which were diffusely dispersed throughout the stroma (Figure 5c,d). One of the two females with a corpus luteum present had an increased number of densely packed uterine glands compared to all other females examined (Figure 5e); the other female had tightly packed glands close to the myometrium that became more diffusely spread out throughout the stroma as they approached the lumen and evidence of uterine oedema (Figure 5f). Juvenile uteri were similar to the adults but with a greatly reduced overall diameter, fewer, smaller, uterine glands and a thickened myometrial layer (Figure 5g,h). In addition, the stromal cells of the juveniles surrounding the uterine glands were small and tightly packed (Figure 5h). In all echidnas examined, there were no discernible differences between the two sides of the uteri in either volume or the number of glands.

FIGURE 5.

Histology of the uterus. (a) Transverse section of a Mallory's stained uterus from an adult female showing the extent of the vascularization (red) in the stroma (blue) amidst the endometrial glands (purple); (b) H&E high power image of (a) showing the numerous enlarged uterine glands. (c) Transverse section of uterus from a lactating female with widely dispersed uterine glands. (d) High power image of (c) highlighting the small uterine glands relative to (b), arrowhead indicates a uterine gland exiting into the lumen. (e) Transverse section of uterus from a recently ovulated female with an active corpus luteum. (f) Transverse section of uterus from a female with a presumed inactive corpus luteum. (g) Transverse section of a juvenile echidna uterus. (h) High power image of (g) showing small uterine glands and densely packed stromal nuclei. En, endometrium; Lu, lumen; Mm, myometrium; St, endometrial stroma. Scale bars: (a), (c), & (g) = 500 μm, (e) & (f) = 1 mm, (b) = 20 μm and (d) & (h) = 200 μm.

3.5. Transition from the uterus to the urogenital sinus

A transition zone between the uterus and UGS was observed in both adult and juvenile females at the distal caudal region of each uterine tube and is preliminarily defined here as a cervical region (Figure 6). The lumen in this region remained highly branched and was lined by simple columnar epithelial cells, many of which were ciliated but endometrial glands were absent in all females examined and the endometrial stroma reduced; the bulk of the cervix was myometrial tissue surrounded by connective tissue (Figure 6). Soon after the cervices entered into the urogenital sinus, the ureters were also observed to migrate to enter into the urogenital sinus (Figure 6e).

FIGURE 6.

Histology of the cervix. (a) H&E transverse section of an adult cervix showing the highly branched nature with no endometrial glands and the close proximity of the ureters. (b) H&E high power image of (a). (c) Mallory's stained transverse section of a juvenile cervix. (d) Mallory's high power image of (c) highlighting the minimal stroma present (dark blue) surrounded by an extensive muscularis (purple) and the surrounding connective tissue (light blue). (e) H&E transverse section of the upper urogenital sinus just after the merging of the left and right sides of the reproductive tract and the path of the left and right ureters just before their entry into the urogenital sinus. Lu, lumen; Mu, muscularis; St, stroma; Ut, ureter. Scale bars: (a), (c) = 1 mm, (b) = 100 μm, (d) = 500 μm, (e) = 5 mm.

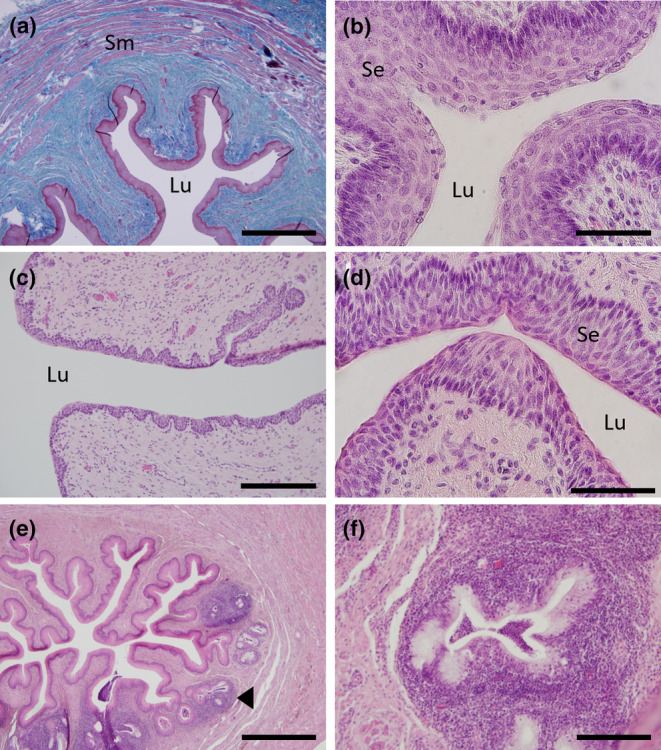

3.6. Urogenital sinus histology

The urogenital sinus was surrounded by a submucosal connective tissue that was encased in well‐developed muscularis of longitudinal and circular muscle which was observed in all females (Figure 7a). The epithelia surrounding the lumen of the branched urogenital sinus was formed by multiple layers of stratified squamous epithelia (Figure 7b). Juvenile females and some adult females had fewer layers of epithelia surrounding the lumen of the UGS compared to other females but this did not appear to correspond to the stage of the cycle (Figure 7c,d). Just prior to the merging of the urogenital sinus with the rectum to form the cloaca, the branching of the urogenital sinus increased with evidence of lymph nodes and glandular tissue, likely accessory glands, within the stroma of the caudal side of the UGS (Figure 7e,f).

FIGURE 7.

Histology of the urogenital sinus (UGS). (a) Mallory's stained transverse section of the UGS showing the thickened stratified epithelium (red‐purple) surrounded by the sub‐mucosal connective tissue (blue) and the outer layers of smooth muscle (purple interspersed with blue). (b) H&E high power section of the UGS showing the thick layers of stratified squamous keratinized epithelium surrounding the urogenital sinus lumen. (c) H&E section of UGS from a female in lactational anoestrus showing the thinner layer of stratified squamous epithelium surrounding the lumen. (d) H&E higher magnification of the UGS epithelia of an early luteal phase female. (e) H&E transverse section of the UGS just above the rectum merging to form the cloaca. (f) H&E high magnification of the glandular structures in (e). Sm, smooth muscle; Se, stratified epithelium; Lu, lumen, black arrowhead indicates location of one of the glandular structures. Scale bars: (a) & (e) = 1 mm, (b) & (c) = 200 μm, (d) = 20 μm and (f) = 100 μm.

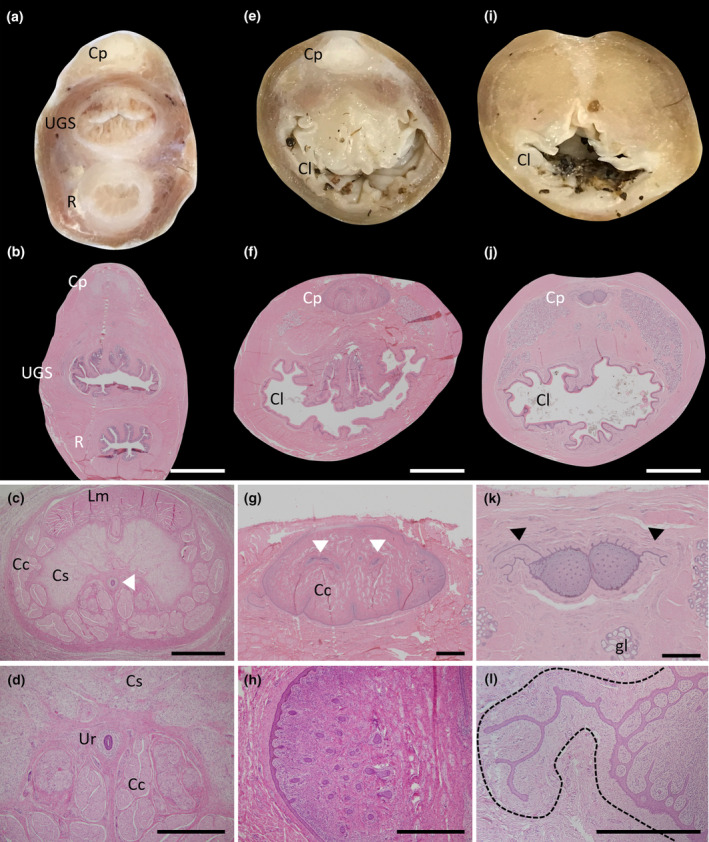

3.7. Clitoris and cloacal morphology

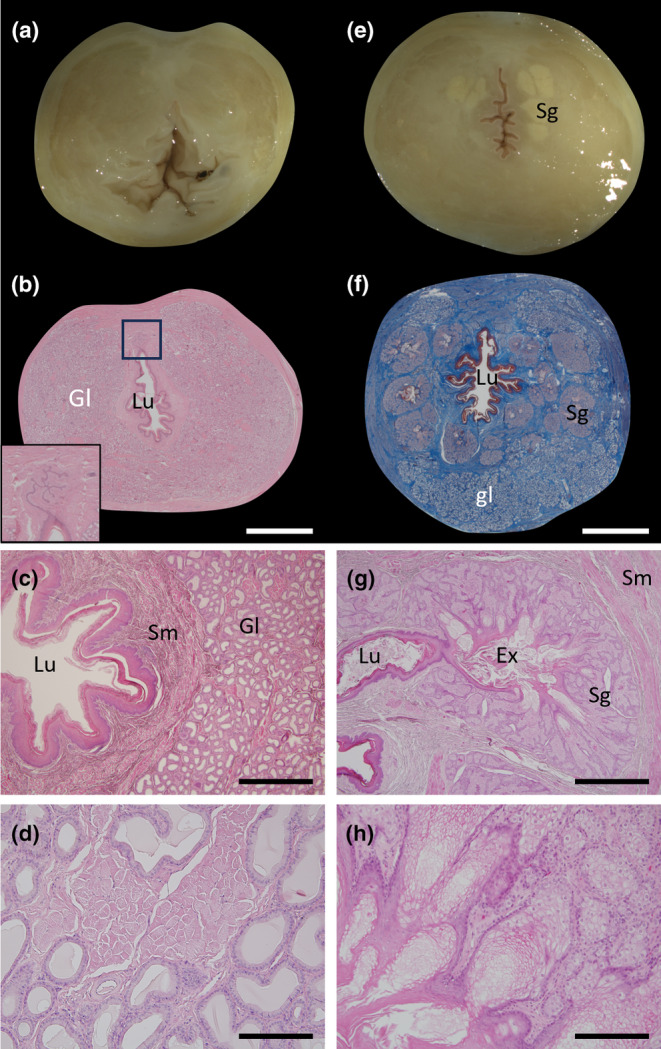

While performing the gross dissections of the female tract, a small phallus‐like structure was observed cranial to the UGS and rectum, just before they merge to form the cloaca (Figure 8a,e,i). It was possible to histologically confirm this structure as a clitoris with phallus‐like morphology (Figure 8). At its cranial end it was composed of a levator muscle on the ventral side, a corpus cavernosum, a corpus spongiosum and single urethral tube (Figure 8c,d). Caudally, the clitoral urethra bifurcated twice in close succession (Figure 8g) and each branch migrated out to each of the four glans at the tip of the clitoris and underwent further divisions to radiate out to the epithelium (Figure 8h). However, only 2 of the clitorides examined showed a patent urethra for part of its length. The majority of the urethral tube remained solid tissue (Figure 8g,h). At the caudal tip of the clitoris, the solid urethral tissue was observed merging with the external epithelium and continuing beyond, forming thin “tendrils” out into the surrounding tissue. It appeared the clitoris was enclosed in an additional tissue layer that surrounded both the central clitoris and around these tendril projections (Figure 8l), close to the glandular tissue of the cloaca (Figure 8k,l). Once the clitoris itself was no longer visible, these urethral “tendrils” could be observed directly connecting with the tip of the cloacal lumen (inset, Figure 9b).

FIGURE 8.

Morphology of the female clitoris. (a) Fixed section of the tract just above the merging of the rectum and UGS to form the cloaca showing the location of the clitoris. (b) H&E section of a similar area as (a). (c) Higher power section of the clitoral from (b). (d) High power image of the patent urethra. (e) Fixed section of the tract after the rectum and UGS have merged to form the cloaca. (f) H&E section of a similar area as (e). (g) Higher power section of the clitoris in (f) showing the branching of the urethra to each side (white arrowheads) and the radiation of the ducts on each edge. (h) High power image of the solid urethral duct radiations (dark purple). (i) Fixed section of the tract at the termination of the clitoris. (j) H&E section of a similar area to (i). (k) Higher power image of the clitoris in (j) showing the continual radiation of the solid urethral ducts (solid purple dots) and what appears to be the continued growth of the urethra into the tissue that immediately surrounds the clitoris (black arrowheads). (l) High power image of one of the urethral extensions into the tissue encasing the clitoris (defined by the black dotted line). Cp, clitoris (phallus‐like); Cl, cloaca; Cc, corpus cavernosum; Cs, corpus spongiosum; Gl, glandular tissue; Lm, levator muscle; R, rectum; UGS, urogenital sinus. Scale bars: (b), (f) & (j) = 5 mm, (c), (g) & (k) = 1 mm, (d), (h) & (l) = 500 μm.

FIGURE 9.

Morphology of the female cloaca. (a) Fixed section of the cloaca just after the clitoris head has terminated. (b) H&E section of the cloaca in a similar area to (a) with extensive glandular tissue surrounding the cloacal lumen and the connection of the clitoral urethral extensions with the lumen of the cloaca (inset). (c) Higher power image of (b) showing the cloacal opening and the surrounding glandular tissue. (d) High power image of the glandular tissue. (e) Fixed section of the cloaca near to its terminal region with the pale coloured, discrete sebaceous glands visible. (f) Mallory's stained section of the cloaca in a similar area to (e) showing the keratinized epithelium (dark red), discrete sebaceous glands (pale purple) and glandular tissue below within the connective tissue (blue). (g) H&E higher power section of one of the sebaceous glands from (f) showing the central collection area of exudate and its connection with the lumen of the cloaca. (h) High power image of the sebaceous glandular tissue in (g). Ex, exudate; Gl, glandular tissue; Lu, lumen; Sg, sebaceous gland; Sm, smooth muscle. Scale bars: (b) & (f) = 5 mm, (c) & (g) = 1 mm and (d) & (h) = 200 μm.

As the intestine and the urogenital sinus merged to form the cloaca, glandular tissue began to appear on the ventral side of the cloaca either side of the caudal end of the clitoris (Figure 8f). This glandular tissue consisted of a simple columnar epithelium with basophilic nuclei (Figure 9d). The proportion of glandular tissue present in the tube continued to increase (Figure 8j) until the caudal end of the clitoris disappeared, the cloaca epithelial lining had undergone extensive keratinisation and the glands comprised the majority of the tube (Figure 9b,c). The exception was the tissue immediately surrounding the cloacal epithelium which was comprised of a layer of connective tissue followed by a layer of smooth muscle bundles (Figure 9b,c). Closer to the exit of the cloaca, in addition to the above glandular tissue, discrete sebaceous‐like, branched alveolar exocrine glands appeared surrounding the cloaca (Figure 9e,f). Each alveolus within the gland was encapsulated by a thin connective tissue layer which contained a peripheral layer of cuboidal cells with spherical nuclei. These cells surrounded the pale‐staining secretory cells which emptied into the central glandular lumen that connected directly with the cloacal lumen (Figure 9g,h). At least some of these discrete sebaceous glands were observed to be directly connected to the external surface of the cloaca (data not shown).

4. DISCUSSION

Echidnas have two functional ovaries, oviducts and uteri, which enter into the UGS and then open into the cloaca (Griffiths, 1968; Griffiths, 1979; Grützner et al., 2008; Temple‐Smith & Grant, 2001; Wood Jones, 1923). The present study described the histology of all these regions in detail across different presumptive stages of the oestrous cycle and confirmed the presence of a cervix. In addition, this study identified for the first time the presence of a clitoris with very similar (homologous) morphology to the adult male penis (albeit significantly smaller) (Fenelon et al., 2021), as well as extensive glandular tissue together with discrete glands within the cloaca. Juvenile female reproductive tracts were also examined for the first time and had many of the same structures as seen in the adults but with underdeveloped ovaries and uteri with reduced numbers of uterine glands.

4.1. Anatomical homology of the echidna ovary to other species

All follicles were confined to the cortex region of the ovary. Adult ovaries had multiple large, spherical protruding follicles, which extended past the surface of the ovarian cortex. Multiple white spots could also be seen in some ovaries which were presumed to be atretic follicles (Flynn & Hill, 1939; Garde, 1930). All ovaries also had significant periovarian adipose tissue deposition. In the female echidna, reproduction is demanding and successful reproduction in captivity is improved by giving increased nutrition during the breeding season (Wallage et al., 2015). These captive echidnas also have a significant increase in body adipose tissue accumulation in the breeding season where most of this accumulation is in the abdominal region (Dutton‐Regester et al., 2024). In humans and mice, this periovarian adipose tissue is important for ovarian function but the exact mechanisms are unknown (Szyrisko & Grzeskiak, 2024).

Monotreme ovarian follicles have been previously defined as first, second and third phase follicles (Flynn & Hill, 1939) and are similar to primordial, primary, secondary and tertiary follicles of therian mammals respectively. Previously, the identification of first phase follicles were not distinguishable between what we would now identify as a primordial follicle (oocyte with a single layer of flattened follicular cells) and a primary follicle (oocyte with a single layer of cuboidal follicular cells). In the echidna, these stages resemble those of other mammals except for the presence of numerous lipid vacuoles. Secondary follicles were identified by their distinct zona pellucida, increased size, increased lipid vacuoles and the beginnings of “yolk body” formation. Third phase (tertiary) follicles were identified by their greatly increased size, the presence of a distinct thecal cell layer and numerous yolk bodies. Flynn and Hill (1939) further characterised third phase follicles into two sub‐phases based on size and level of yolk development; lipid vacuoles make up the cortical fatty zone surrounding the core of the oocyte in developing and mature follicles. Surrounding the cortical fatty zone were distinct yolk‐bodies observed from developing secondary to mature tertiary follicles. The yolk in the echidna ovum is at least partly homologous to the yolk of birds and reptiles (Frankenberg & Renfree, 2018), but further compositional analysis is required. In oviparous species, yolk is composed of three major yolk proteins; vitellogenin‐1 (VTG1), VTG2 and VTG3. In contrast, monotremes have only one functional vitellogenin gene (VTG2) with a partial sequence of VTG1 and no evidence for VTG3 (Zhou et al., 2021). Marsupials are the only other mammals to retain a vitellogenin gene (VTG2) but this is non‐functional with no evidence for any remnant VTG in eutherian mammals (Frankenberg & Renfree, 2018; Zhou et al., 2021).

In the juvenile ovaries, only small protruding follicles were present in some females and the most immature animals had no protruding follicles present with only a convoluted cortex visible. Histological analyses indicated only primordial and primary follicles were present at these stages. This is somewhat similar to 3‐month‐old juvenile chicken ovaries in which the ovarian cortex is convoluted, but there is an absence of protruding follicles (Mfoundou et al., 2021). The relatively thin convoluted cortex structure of the adults contained all follicle stages. Consistent with previous reports, the echidna ovarian medulla was composed predominantly of smooth muscle fibre bundles and collagen (Hill & Gatenby, 1926). Echidnas normally only ovulate one egg at a time (Griffiths, 1968) and while multiple eggs and up to three pouch young have been observed, these do not appear to survive to weaning (Dutton‐Regester et al., 2021; Keeley & Johnston, 2019). In many of the adult ovaries, atretic follicles were observed from all phases of follicular growth and distinct corpora lutea were observed in two females with structures consistent with what had previously been observed in platypus (Garde, 1930).

4.2. Oviduct anatomy and physiology

In adult echidna females there was a gradual transition along the length of the oviduct from an infundibulum region to the ampulla and the isthmus, consistent with previous reports (Hill, 1941; Hill & Hill, 1936). The number of folds of the convoluted luminal epithelium of the echidna oviduct increased from the infundibulum to ampulla, before reducing in the isthmus, while the muscularis layer increased in thickness from the ampulla to isthmus, similar to that seen in other mammals (Seraj et al., 2024). In some adult females, there were vacuoles in the epithelium of the infundibulum which appeared to depend on the stage of the oestrous cycle, with other adult females having a greatly reduced epithelial cell height. These observation are consistent with a previous report that secretory cells only exist in the infundibulum in preparation for ovulation and are inactivated and regress once the oocyte is ovulated (Hill, 1941); we propose that the production of these secretions aid in oocyte transport.

In the ampulla, the cytoplasm of the secretory cells was enlarged when compared to other epithelial cells along the reproductive tract consistent with this as the major source of secretory proteins in the oviduct. The ampulla is also the region in the monotremes where the mucoid or albumen layer is deposited on the zona pellucida before the addition of the shell layers (Hill, 1941, Hill & Hill, 1936). Additional post‐ovulatory layers are secreted by the oviduct and or uterus in all vertebrates except teleosts and most eutherians (Lombardi, 1998). In many species, this consists of either albumen, mucins or glycoproteins and are thought to have roles, depending on species, in fertilization, preventing polyspermy, immune protection, physical protection and/or nutrition (Menkhorst & Selwood, 2008). In monotremes, spermatozoa have been observed trapped in this layer suggesting it has a similar function to marsupials (Frankenberg & Renfree, 2018; Griffiths, 1968).

In the isthmus, no cilia were observed, instead distinct oviductal glands with columnar epithelium were present with granular secretions present in their cytoplasm. These findings support earlier conclusions that these oviductal glands are responsible for the initial basal layer of the shell and are homologous to the marsupial shell coat (Hill, 1941; Menkhorst & Selwood, 2008). In marsupials, shell coat deposition occurs at the end of the isthmus in the utero‐tubal region (Tyndale‐Biscoe & Renfree, 1987) and are thought to be modified uterine glands that have migrated into the isthmus (Frankenberg & Renfree, 2018; Menkhorst & Selwood, 2008). However, unlike marsupials, monotremes continue shell deposition while the embryo continues to develop in the uterus (Hill & Hill, 1936).

4.3. Uterine anatomy

Despite their oviparous reproductive strategy, monotremes produce significant amounts of maternal uterine secretions that are transferred across the porous egg shell in order to help nourish and support the growth of the embryo (Frankenberg & Renfree, 2018). The female with an active CL observed in this study had extensive uterine gland formation, consistent with an increase in maternal uterine secretions during pregnancy. In contrast, the lactational anoestrous female had a noticeable decrease in the size and number of uterine glands consistent with a regressed corpora lutea and a decrease in ovarian activity. Interestingly, one female had an apparent active CL but there were a reduced number of glands in her uterus, potentially indicative of a failed pregnancy. Similar to marsupials, the monotremes have complete separation of their oviducts and uteri but there appeared to be no difference in the proportion of uterine gland tissue present between the two sides. Unfortunately, no later stages of pregnancy were available for this study, but it is likely that there would be an increase in uterine glands on the gravid side due to the additional nutritional requirements of the fetus for its development as seen in monovular marsupials (Laird et al., 2016; Renfree, 1973a; Renfree, 1973b; Tyndale‐Biscoe & Renfree, 1987).

4.4. Transitional region – The cervix

The presence of a cervix had not been confirmed or previously defined in the echidna. Until this study, it was unclear to what degree the echidna possessed a ‘traditional’ mammalian cervix (Grützner et al., 2008; Owen, 1868). In the current study, a cervix‐like structure was identified towards the end of the uterine tube before it entered the UGS. The cellular structure of this tissue resembled the microanatomy of the uterus with simple columnar epithelium that was extensively branched but cilia were also present on many of the cells and no glandular tissue was present. The cervical stroma was also greatly reduced relative to the uterus and had a thickened layer of circular smooth muscle. In the koala, mucin‐producing cells are present in the cervical epithelium, similar to those found in the infundibulum (Pagliarani et al., 2023). No distinct secretory cells were detected in this study, but this may be due to the stages examined as no echidnas in late pregnancy were observed, which is when cervical secretions would be of benefit in preparation for egg transport. Cervices entered directly into the singular UGS.

4.5. Urogenital sinus anatomy

Identifying characteristics of mammalian vaginae, such as a predominance of longitudinal muscle bundles, was not observed in the echidna UGS. However, there were a greater number of circular muscle fibres after the cervix. The female in early luteal phase had a thinner stratified squamous epithelium of the UGS lumen than the follicular phase female. Only one animal showed a considerable difference in structure, so it is unclear whether this difference was related to ovarian activity or was variation associated with the individual female.

4.6. Clitoris and cloacal anatomy

In the adult male echidna, the penis, when not in use, is retracted into the preputial sheath which lies closely opposed to the ventral body wall, just above the opening of the cloaca (Fenelon et al., 2021). Although the phallus‐like clitoris found in female echidnas in this study was significantly smaller than that found in the male, the internal morphology was almost identical or homologous. This included the possession of a levator muscle, a corpus spongiosum, a corpus cavernosum and a urethra that divided into four distinct branches that then radiated out. In contrast to the male, the female urethrae did not appear patent and did not exit via the clitoris. There was no evidence that the clitoris could be everted to the outside of the body as in the male, but it did appear to have the potential to connect directly with the glandular tissue of the cloaca via epithelial extensions branching out from the terminal end of the clitoris. It is unknown to what extent the corpus cavernosum‐like tissue could fill with blood and become erect, as in the male, or whether this urethra was connected to the UGS. Previously a “heart‐shaped clitoris” has been observed in the platypus and was described as similar in overall morphology to the adult male penis but no further details were reported (Owen, 1868).

Consistent with previous reports, there were secretory exocrine glands located in the cloaca wall of the echidna (Allen, 1982; Russell, 1985). These are likely to be scent glands as olfactory signals are thought to be important for echidna reproductive and social behaviours and echidnas are known to scent mark, including engaging in cloaca “wiping” behaviour (Beard et al., 1992; Buchtova et al., 2008).

5. CONCLUSIONS

All echidna samples in this study were obtained within the usual breeding season of this species. Considerable differences between female echidna uterine histology were observed which reinforces the close functional relationship between ovarian activity and steroid hormone production on the physiological response of the reproductive tract in this species. Unfortunately, no mid‐late pregnancy stages were available, which limited interpretations into how the uteri change in response to pregnancy. It would be interesting to examine adult female echidna reproductive tracts outside of their breeding season to determine the extent to which the reproductive tract undergoes seasonal anoestrus. Regardless, this study highlights the importance of the monotremes as model organisms to examine in detail the evolutionary transition in mammals from a presumably purely oviparous common ancestor to the purely viviparous reproductive strategy seen today.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jane C. Fenelon, Marilyn B. Renfree and Stephen D. Johnston conceived and designed the project, Stephen D. Johnston led the acquisition of samples; Stephanie B. Ferrier and Jane C. Fenelon performed research, Stephanie B. Ferrier, Jane C. Fenelon, Marilyn B. Renfree and Stephen D. Johnston analysed and interpreted the data; Stephanie B. Ferrier and Jane C. Fenelon wrote the first draft. All authors substantively revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Funding for this project was provided by the Australian Research Council (ARC) through the ARC Linkage Grant (LP160101728) administered through the University of Melbourne in collaboration with the University of Queensland.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the veterinary staff at the Royal Society Protection and Care of Animals Wildlife Hospital (RSPCA, Queensland) and Currumbin Wildlife Hospital who provided support for sample collection. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Fenelon, J.C. , Ferrier, S.B. , Johnston, S.D. & Renfree, M.B. (2025) Observations on the reproductive morphology of the female short‐beaked echidna, Tachyglossus aculeatus . Journal of Anatomy, 246, 120–133. Available from: 10.1111/joa.14142

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Allen NT (1982) A study of the hormonal control, chemical constituents, and functional significance of the paracloacal glands in Trichosurus vulpecula (including comparisons with other marsupials).). Perth, Australia: University of Western Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Augee, M.L. (2006) Echidna: extradordinary egg‐laying mammal. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, L.A. , Grigg, G.C. & Augee, M.L. (1992) Reproduction by echidnas in a cold climate. In: Augee, M.L. (Ed.) Platypus and echidnas. Mosman, New South Wales, Australia: The Royal Zoological Society of NSW, Sydney, pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Buchtova, M. , Handrigan, G.R. , Tucker, A.S. , Lozanoff, S. , Town, L. , Fu, K. et al. (2008) Initiation and patterning of the snake dentition are dependent on Sonic hedgehog signaling. Developmental Biology, 319, 132–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton‐Regester, K. , Keeley, T. , Fenelon, J.C. , Roser, A. , Meer, H. , Hill, A. et al. (2021) Plasma progesterone secretion during gestation of the captive short‐beaked echidna. Reproduction, 162, 267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton‐Regester, K. , Roser, A. , Meer, H. , Hill, A. , Pyne, M. , Al‐Najjar, A. et al. (2024) Body fat and circulating leptin levels in the captive short‐beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus). Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 194, 457–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenelon, J.C. , McElrea, C. , Shaw, G. , Evans, A.R. , Pyne, M. , Johnston, S.D. et al. (2021) The unique penile morphology of the short‐beaked echidna, Tachyglossus aculeatus . Sexual Development, 15, 262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, T. (1995) Mammals of New Guinea. Chatswood, NSW: Reed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, T.T. & Hill, J.P. (1939) The development of the Monotremata – part IV. Growth of the ovarian ovum, maturation, fertilisation, and early cleavage. The Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 24, 445–622. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg, S. & Renfree, M.B. (2018) Conceptus coats of marsupials and monotremes. In: Litscher, E.S. & Wassarman, P.M. (Eds.) Extracellular matrix and egg coats. Cambridge: Academic Press, pp. 357–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garde, M.L. (1930) The ovary of Ornithorhynchus, with special reference to follicular atresia. Journal of Anatomy, 64, 422–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, M. (1968) Echidnas. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, M. (1979) The biology of the monotremes. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grützner, F. , Nixon, B. & Jones, R.C. (2008) Reproductive biology in egg‐laying mammals. Sexual Development, 2, 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.J. (1941) The development of the Monotremata – part V. Further observations on the histology and secretory activities of the oviduct prior to and during gestation. The Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 25, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.J. & Hill, J.P. (1936) The development of the Monotremata – part I. The histology of the oviduct during gestation. Part II. The structure of the egg‐shell. The Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 21, 413–477. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J.P. & Gatenby, J.B. (1926) The corpus luteum of the Monotremata. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 96, 715–763. [Google Scholar]

- Home, E. (1802a) A description of the anatomy of the Ornithorhynchus paradoxus . Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 92, 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Home, E. (1802b) XI. Description of the anatomy of the Ornithorhynchus hystrix . Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 92, 348–364. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, R.L. & Carrick, F.N. (1978) Reproduction in female monotremes. The Australian Zoologist, 20, 233–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, R.L. & Hall, L.S. (1998) Early development and embryology of the platypus. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 353, 1101–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley, T. & Johnston, S.D. (2019) Assessment and management of reproduction in Australian monotremes and marsupials. In: Current therapy in medicine of Australian mammals. Clayton South, Victoria, Australia: CSIRO Publishing, pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Keibel, F. (1904) Zur Entwickelungsgeschichte des Urogenitalapparates von Echidna aculeata var. typica . Denkschriften der Medicinisch‐Naturwissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft zu Jena, 6, 151–206. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, M.K. , Hearn, C.M. , Shaw, G. & Renfree, M.B. (2016) Uterine morphology during diapause and early pregnancy in the tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii). Journal of Anatomy, 229, 459–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, J. (1998) Comparative vertebrate reproduction. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Menkhorst, E. & Selwood, L. (2008) Vertebrate extracellular preovulatory and postovulatory egg coats. Biology of Reproduction, 79, 790–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mfoundou, J.D.L. , Guo, Y.J. , Liu, M.M. , Ran, X.R. , Fu, D.H. , Yan, Z.Q. et al. (2021) The morphological and histological study of chicken left ovary during growth and development among Hy‐line brown layers of different ages. Poultry Science, 100, 101191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Guidelines (2013) Australian code for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes. National Health and Medical Research Council, NHMRC (Ed). Canberra, ACT: Australian Government. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, R. (1868) On the anatomy of vertebrates. London: Spottiswoode and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarani, S. , Palmieri, C. , McGowen, M. , Carrick, F. , Boyd, J. & Johnston, S.D. (2023) Anatomy of the female koala reproductive tract. Biology, 12, 1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfree, M.B. (1973a) The composition of fetal fluids of the marsupial Macropus eugenii . Developmental Biology, 33, 62–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfree, M.B. (1973b) Proteins in the uterine secretions of the marsupial Macropus eugenii . Developmental Biology, 32, 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfree, M.B. & Shaw, G. (2018) Comparative mammalian female reproduction: overview. In: Skinner, M.K. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of reproduction. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, pp. 609–616. [Google Scholar]

- Rismiller, P.D. & McKelvey, M.W. (2003) Body mass, age and sexual maturity in short‐beaked echidnas, Tachyglossus aculeatus . Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 136, 851–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, E.M. (1985) The prototherians: order Monotremata. In: Brown, R.E. & MacDonald, D.W. (Eds.) Social odours in mammals. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seraj, H. , Nazari, M.A. , Atai, A.A. , Amanpour, S. & Azadi, M. (2024) A review: biomechanical aspects of the fallopian tube relevant to its function in fertility. Reproductive Sciences, 31, 1456–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyrisko, W. & Grzeskiak, M. (2024) Periovarian adipose tissue – an impact on ovarian functions. Physiological Research, 73, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple‐Smith, P. & Grant, T. (2001) Uncertain breeding: a short history of reproduction in monotremes. Reproduction, Fertility and Development, 13, 487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyndale‐Biscoe, C.H. & Renfree, M.B. (1987) Reproductive physiology of marsupials. Cambridge: Cambridge University. [Google Scholar]

- Wallage, A. , Clarke, L. , Thomas, L. , Pyne, M. , Beard, L. , Ferguson, A. et al. (2015) Advances in the captive breeding and reproductive biology of the short‐beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus). Australian Journal of Zoology, 63, 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Wood Jones, F. (1923) The mammals of South Australia. Adelaide: R.E.E. Rogers, Goverment Printer. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. , Shearwin‐Whyatt, L. , Li, J. , Song, Z. , Hayakawa, T. , Stevens, D. et al. (2021) Platypus and echidna genomes reveal mammalian biology and evolution. Nature, 592, 756–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.