Abstract

Fibrinogen (FBG) has been discovered to be associated with cognitive impairment (CI) and dementia. However, the exact correlation between FBG levels and CI after acute ischemic stroke (AIS) remains uncertain. Plasma FBG levels were measured in 398 patients with AIS who underwent comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation. To assess the correlation of FBG with global cognitive function, physical status, anxiety, depression, and psychiatric symptoms. Multifactorial logistic regression was used to analyze risk factors for CI. Constructed and plotted a nomogram graph to visualize the CI prediction model. The model was further evaluated for discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility. The results indicate that plasma FBG levels are significantly elevated in patients with CI compared to those with non-cognitive impairment (NCI). Analysis of the overall population reveals that elevated FBG levels are correlated with both reduced cognitive function and decreased activity status. After adjusting for other influencing factors, high FBG levels were identified as a risk factor for the incidence of CI. We developed an intuitive and valid predictive model for CI, demonstrating its suitability for clinical application. In conclusion, our study demonstrates that plasma FBG serves as a potential biomarker of CI following AIS, offering a novel perspective for the identification of CI.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-83907-1.

Keywords: Acute ischemic stroke, Fibrinogen, Cognitive impairment, Dementia

Subject terms: Cognitive ageing, Cognitive neuroscience, Diseases of the nervous system

Introduction

Cognitive impairment (CI) is the main neurological deficit that persists after stroke1. CI not only exerts a profound impact on the quality of life for individuals but also notably curtails their effective lifespan, causing tremendous psychological pressure and economic burden to patients, their families, and society2. Therefore, identifying reliable biomarkers and potential pathological mechanisms to predict CI and developing targeted interventions to reduce its occurrence are imperative.

The pathogenesis of CI remains incompletely elucidated, with research indicating its primary associations with advanced age, female, low educational attainment, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia3. Additionally, factors such as cerebrovascular injury, cerebral neurodegeneration, inflammatory response, and genetic predispositions have been implicated4. Fibrinogen (FBG), an intravascular protein intricately entwined in the processes of coagulation and inflammation5, assumes a pivotal role. Elevated intravascular FBG levels have the potential to modulate vascular reactivity and compromise endothelial cell integrity6. Upon leakage through the compromised blood-brain barrier (BBB) and subsequent deposition into the central nervous system (CNS), FBG instigates neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration7,8. Moreover, the molecular structure of FBG contains receptors and protein-binding sites that orchestrate signaling cascades involved in a multitude of processes contributing to CNS neurodegeneration, including microglia activation5. Microglia-associated neuroinflammation play crucial roles in CNS injury and disease progression. Polarization of microglia to an activated M1 phenotype9, activation of AIM2 inflammasome-mediated inflammation and apoptosis10, and phagocytosis of synapses and neurons11 all contribute to a decline in cognitive function after stroke. The correlation between elevated FBG concentrations and the onset of vascular dementia has been substantiated in prospective studies spanning an average follow-up duration of up to 17 years12,13. Additionally, in cohorts characterized by atherosclerosis but lacking cardiovascular problem at baseline, a relationship with cognitive recession was observed over a 5 years follow-up period14. Consequently, FBG levels emerge as a promising candidate biomarker for cognitive decline subsequent to stroke.

In this study, we investigated the correlation between plasma FBG levels and both cognitive performance and daily activity status, while identifying factors influencing the development of CI after stroke. Additionally, we developed a intuitive and effective nomogram based on the identified CI-related factors.

Methods

Study design and participants

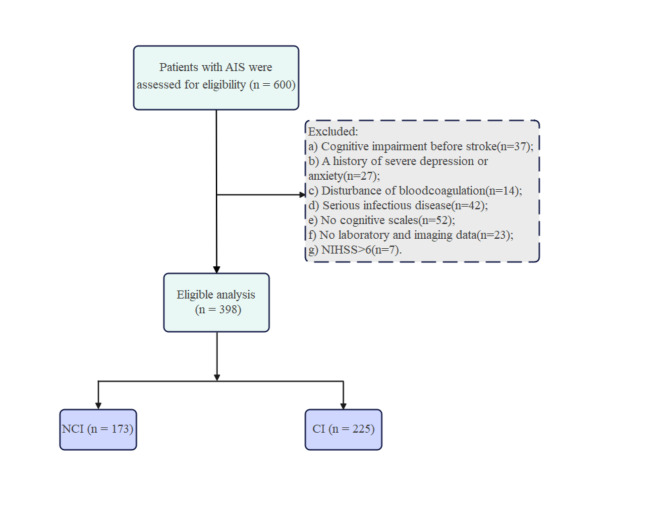

Patients diagnosed with AIS were recruited from the Department of Neurology at the First Hospital of Jilin University. Inclusion criteria comprised the following: (a) fulfillment of the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for AIS15 and age between 50 and 80 years; (b) presentation of focal neurological deficits along with newly infarcted lesions detected via brain magnetic resonance (MR) diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI); (c) conservative medical treatment rather than reperfusion therapy (e.g., thrombolysis and thrombectomy); and (d) capability to collaborate in administering pertinent assessments and cognitive scales. The exclusion criteria were defined as follows: (a) cognitive impairment before stroke (n = 37), (b) history of severe depression or anxiety (n = 27), (c) disturbance of blood coagulation (n = 14), (d) serious infectious disease (n = 42), and (e) invalid cognitive function scales (n = 52), (f) invalid laboratory and imaging data (n = 23), and (g) an National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of > 6 (n = 7). The final analysis included 398 patients (Fig. 1). Prior to enrollment, written informed consent was obtained from all patients and their caregivers, with informed written consent additionally acquired from all participants. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participants recruitment. AIS, Acute ischemic stroke; CI, cognitive impairment; NCI, no-cognitive impairment; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale.

Cognitive and psychological assessments

On days 7–14 after the AIS symptoms and emotions were relatively stable, all included patients underwent cognitive-psychological assessment by a psychometrically qualified evaluator in a quiet environment with no uninvolved persons present. Global cognitive function was assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), with a total score of 30. The MMSE can comprehensively assesses patient orientation, memory, calculation and attention, language, writing, and structural abilities. The MoCA can also be used to assess several aspects of patients’ visuospatial and executive abilities, naming, abstraction, and delayed recollection. The MoCA is more complex than the MMSE and allows for a better judgment of the degree of CI in patients with different levels of education. Consistent with the MMSE scores, lower MoCA scores represent more severe cognitive performance. With an education level of less than 12 years, subjects were given an additional 1 point to their total MoCA score, and the final study subjects were categorized into CI (MoCA < 22) and NCI (MoCA ≥ 22) group16.

Activities of Daily Living (ADL) were used to assess self-care skills. The Hamilton Anxiety rating scale (HAMA) and Hamilton Depression rating scale (HAMD) were used to assess anxiety and depression. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) was used to assess psychobehavioral symptoms.

Data collection

Comprehensive clinical data, encompassing age, sex, level of education, body mass index (BMI) and pertinent medical history were collected during hospitalization. Cerebral infarction was classified based on its etiology using the globally recognized Trial of Org 10,172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria, which encompass large artery atherosclerosis (LAA), cardiogenic embolism (CE), small artery occlusion (SAO), other causes (OD), and unexplained categories (UND)17. The severity of neurological deficits was evaluated using the NIHSS18.

Blood samples were obtained within 24 h of AIS onset to assess FBG, fasting blood glucose, diverse lipid profiles and homocysteine levels. Patients exhibiting hypersensitive C-reactive protein levels exceeding 10.0 mg/L were excluded from the analysis to mitigate the confounding effect of acute inflammation on FBG measurements.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were depicted as frequencies (percentages), while continuous variables, failing to adhere to normal distribution, were represented as medians (interquartile range [IQR]). In the univariate analysis, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with CI and NCI, as deemed appropriate. Dose-response relationships between plasma FBG and cognitive function as well as activity status were analyzed using restricted cubic splines (RCS). Multivariate logistic regression was applied to identify factors associated with CI. A nomogram was constructed based on CI correlates, and the model was evaluated for discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility.

Statistical analyses were conducted using R software version 4.3.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed p < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of participants

The study comprised 398 patients, among whom 225 (56.5%) were diagnosed with CI after stroke. The mean age and education level were 62.3 ± 7.67 years and 10.2 ± 3.78 years, respectively. Among the common risk factors for cerebrovascular disease, the number of participants with a history of hypertension and smoking was high (256 [64.3%] and 199 [50%], respectively). Patients with CI were adequately matched with those having NCI concerning BMI, history of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, smoking, and drinking (all p > 0.05). Participants who were female, older, had higher NIHSS scores, lower education level and previous history of stroke was found to be more prevalent in the CI group (p < 0.05). The FBG levels were significantly higher in the CI group compared to the NCI group (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics between CI and NCI groups.

| Variables | NCI(n = 173) | CI(n = 225) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Agea (years) | 60 (54, 67) | 63 (58, 69) | 0.001** |

| Femaleb, n (%) | 43 (24.9) | 79 (35.1) | 0.028* |

| BMIc(kg/m2) | 25.12 ± 3.27 | 24.77 ± 2.95 | 0.292 |

| Education levela (years) | 12 (9, 15) | 9 (6, 12) | < 0.001*** |

| Medical historyb, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 102 (59.0) | 154 (68.4) | 0.05 |

| Diabetes | 52 (30.1) | 71 (31.6) | 0.749 |

| CVD | 34 (19.7) | 36 (16.0) | 0.343 |

| History of stroke | 36 (20.8) | 68 (30.2) | 0.034* |

| History of smoking | 89 (51.4) | 110 (48.9) | 0.613 |

| History of drinking | 78 (45.1) | 96 (42.7) | 0.629 |

| Clinical characteristicsa | |||

| NIHSS (score) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 4) | < 0.001*** |

| Stroke etiologyb, n(%) | 0.125 | ||

| LAA | 65 (37.6) | 110 (48.9) | |

| CE | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.4) | |

| SAO | 64 (37.0) | 64 (28.4) | |

| OD | 32 (18.5) | 36 (16.0) | |

| UND | 9 (5.2) | 14 (6.2) | |

| Laboratory characteristicsa | |||

| Fasting blood glucose (mmol/L) | 5.51 (4.95, 6.67) | 5.61 (5.05, 6.93) | 0.693 |

| HbA1C (%) | 6.0 (5.6, 7.0) | 6.1 (5.7, 7.6) | 0.181 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.57 (3.89, 5.25) | 4.46 (3.75, 5.25) | 0.583 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.56 (1.20, 2.18) | 1.58 (1.19, 1.98) | 0.640 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.00 (0.89, 1.17) | 1.00 (0.88, 1.15) | 0.713 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.80 (2.37, 3.32) | 2.73 (2.26, 3.32) | 0.356 |

| Homocysteine (ųmol/L) | 12.60 (10.35, 15.60) | 12.80 (10.65, 16.47) | 0.288 |

| FBG (g/L) | 2.83 (2.38, 3.23) | 2.99 (2.58, 3.46) | 0.001** |

Variablesa, median (IQR); Variablesb, n (%); Variablesc, mean ± SD. BMI, Body Mass Index; CVD, Cardiovascular disease; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; LAA, Large artery atherosclerosis; CE, Cardiogenic embolism; SAO, Small artery occlusion; OD, Other definite; UND, Unidentified; HbA1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C, High-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FBG, Fibrinogen.

* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

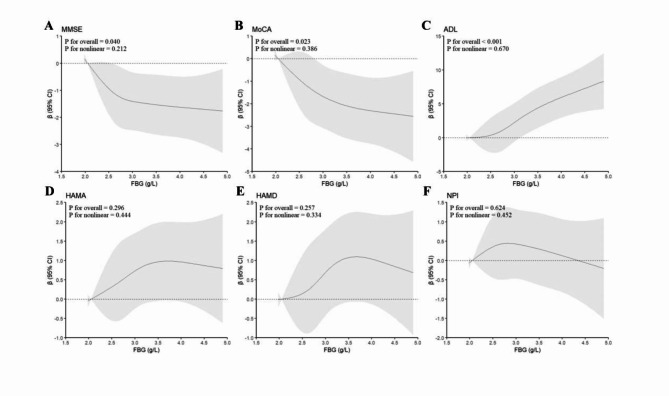

Association between FBG and neuropsychological assessments

Plasma FBG was analyzed for its correlation with cognitive function, mood state, and daily living ability using RCS. The analysis revealed a significant dose-response relationship between FBG levels and MMSE (Fig. 2A, p for overall = 0.040, p for nonlinear = 0.212), MoCA (Fig. 2B, p for overall = 0.023, p for nonlinear = 0.386), and ADL (Fig. 2C, p for overall < 0.001, p for nonlinear = 0.670) scores, indicating that higher plasma FBG levels were associated with poorer cognitive function and reduced ability to perform activities of daily living. However, no significant relationship was observed between FBG levels and HAMA, HAMD, or NPI scores (Fig. 2D–F).

Fig. 2.

Restricted cubic spline curves for cognitive scores and status of activity by FBG. FBG, fibrinogen; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety scale; HAMD, Hamilton Depression scale; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

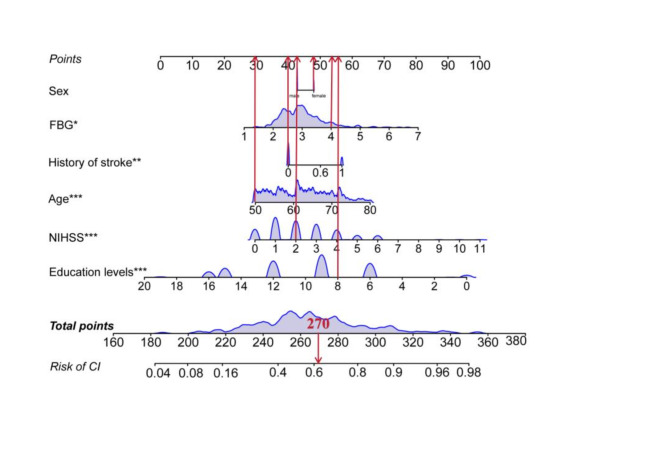

Factors selection, development and performance of the nomogram model

Multivariate logistic regression was employed to explore the factors influencing CI (Table 2). After adjusting for other covariates, FBG, age, education level, NIHSS score, and stroke history were identified as independent predictors of CI. Although sex was not an independent predictor, it was included as a basic demographic characteristic. Consequently, these six variables were ultimately incorporated into the construction of the nomogram (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of cognitive impairment (CI).

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FBG (g/L) | 1.405 | 1.010–1.955 | 0.044* |

| Age (years) | 1.056 | 1.024–1.089 | 0.001** |

| Female | 1.195 | 0.638–2.240 | 0.578 |

| Education levels (years) | 0.798 | 0.742–0.858 | < 0.001*** |

| NIHSS (score) | 1.316 | 1.135–1.525 | < 0.001*** |

| Hypertension | 1.551 | 0.959–2.509 | 0.074 |

| Diabetes | 1.225 | 0.735–2.041 | 0.437 |

| CVD | 0.567 | 0.302–1.066 | 0.078 |

| History of stroke | 1.917 | 1.131–3.250 | 0.016* |

| History of smoking | 0.773 | 0.454–1.318 | 0.345 |

| History of drinking | 1.189 | 0.679–2.083 | 0.545 |

FBG, fibrinogen; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; CVD, Cardiovascular disease.

* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Fig. 3.

A nomogram plot predicting the probability of CI occurrence. The nomogram is plotted by sex, age, education levels, NIHSS, FBG and history of stroke six variables. Each parameter has a corresponding score value, and the individual scores are summed to obtain the total score, which gives the probability of risk of CI. The graph shows an example of a 50 year old woman with NIHSS = 2, Education levels (years) = 8, FBG = 4 g/L, without history of strike, the risk of this patient developing CI is 0.62. CI, cognitive impairment; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; FBG, fibrinogen. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The model’s performance was evaluated in terms of discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility. Receiver operating characteristic curve demonstrated good discrimination between CI and NCI (Fig. 4A). Internal validation was conducted on 1000 samples using bootstrapping, and calibration curves were used to assess the accuracy of the nomogram. As shown in Fig. 4B, the model’s predictions were closely aligned with the ideal model, indicating strong consistency. Furthermore, decision curve analysis confirmed the model’s good clinical utility (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

The discrimination, calibration and clinical utility of the nomogram. The ROC curve for the prediction model shows an AUC of 0.760 (95% CI = 0.714–0.807) (A). Calibration curve predicting the probability of CI in patients with mild AIS (B). Clinical utility was assessed using clinical decision curves (C). AIS, Acute ischemic stroke; CI, cognitive impairment; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses among participants without hypertension. Our results found that FBG levels were higher in the CI group (2.97 ± 0.64) than in the NCI (2.76 ± 0.57) group (Fig. S1). Further investigation indicated a pronounced dose-response relationship between FBG levels and cognitive scores on the MMSE (Fig. S2A, p for overall = 0.044, p for nonlinear = 0.513), MoCA (Fig. S2B, p for overall = 0.047, p for nonlinear = 0.846), and ADL (Fig. S2C, p for overall = 0.004, p for nonlinear = 0.069) scales. However, no significant correlation was observed between FBG levels and the HAMA, HAMD, or NPI. Multivariable regression analysis identified FBG, age, education level, NIHSS score, and history of stroke as independent predictors of CI (Table S1). These results align with the analysis of the entire study population.

Discussion

In a study involving patients aged > 50 years with AIS, we investigated the relationship between plasma FBG levels and CI. We observed higher plasma FBG levels in the CI group than in the NCI group during the acute phase of AIS. Intriguingly, FBG remained an independent predictor of CI after adjusting for multiple covariates. Further analysis indicated that elevated FBG levels may be linked to poorer cognitive function and daily activity performance. Using the identified CI indicators, we developed an intuitive, validated model with strong differentiation and calibration, making it suitable for clinical application.

Epidemiological research has consistently revealed a robust correlation between elevated FBG levels and CI, with FBG emerging as a significant prognostic marker for cognitive decline and dementia. For instance, a pivotal study within the Aspirin for Asymptomatic Atherosclerosis (AAA) Trial in central Scotland demonstrated that increased circulating FBG levels are predictive of subsequent cognitive performance decline and are associated with age-related cognitive deterioration across various domains, including general cognitive function14. Building on these findings, another investigation indicated that elevated plasma FBG levels are linked to reduced attention performance in individuals with mild cognitive impairment, irrespective of Apolipoprotein E genotype or vascular risk factors19. Additionally, a meta-analysis further supports the notion that high plasma FBG levels could be a potential risk factor for all-cause dementia and vascular dementia, particularly among individuals under 80 years of age20. Drawing from the aforementioned research, our study revealed a strong correlation between elevated FBG levels and CI following AIS. Moreover, our in-depth analysis suggests that these heightened FBG levels are predictive of diminished cognitive performance and reduced mobility.

Various mechanisms may elucidate the involvement of FBG in CI after AIS. Firstly, FBG-related plaques, characterized by high erosion and instability, are susceptible to microembolism, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, and subsequent post-stroke dementia21. During stroke, FBG levels surge as reactive proteins in the acute inflammatory phase. Plasma FBG, which normally cannot cross the BBB, infiltrates the CNS following stroke-induced BBB disruption22, leading to neuronal injury, neuroinflammation, and immune cell infiltration23,24. Additionally, leaked FBG from the vasculature binds to Aβ42, activating microglia and culminating in neurodegeneration and cognitive decline within the CNS25. Also, FBG binding to macrophage receptors induces the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, as well as the release of reactive oxygen species, processes closely linked to BBB disruption and brain damage8. Moreover, FBG also modulates TGF-β receptor signaling in astrocytes, triggering astrocytic secretion of TGF-β, which impedes synaptic growth and results in cognitive dysfunction26. Post-stroke, the increased release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, notably interleukin-6, may stimulate elevated FBG expression27. What’s more, elevated FBG concentrations can activate endothelial matrix metalloproteinase-9, contributing to enhanced vascular remodeling and permeability28. Lastly, as a constituent of the perivascular extracellular matrix, FBG has the capacity to enhance BBB permeability through direct interaction with brain endothelial cells6. In essence, FBG leakage due to BBB destruction after stroke amplifies the inflammatory response and oxidative stress, further exacerbating BBB destruction and neuronal damage after ischemia, ultimately leading to cognitive decline.

FBG serves as a valuable parameter for the sensitive detection of vascular abnormalities causally linked to the onset of cerebrovascular disease. Elevated FBG levels are firmly established to correlate with incident arterial diseases in the elderly population. Elevated FBG levels augment plasma viscosity, promote platelet aggregation, and trigger hemostasis activation, thereby fostering the formation of arteriolosclerotic plaques and fostering a prothrombotic state within the circulatory system29. Furthermore, FBG serves as an acute-phase reactant protein intricately involved in inflammatory responses. Nonetheless, the extent to which their association with CI stems from their involvement in coagulation or inflammation remains contentious.

Pharmacologically or genetically reduced FBG levels decrease neurovascular pathology and inflammatory responses in mice30, improve prognosis after stroke, reduce neurological damage, and improve patients’ quality of life31–33. The administration of the FBG-Aβ interaction inhibitor RU-505 in dementia mice results in alleviation of vascular lesions, suppression of neuroinflammation, and enhancement of cognition34. Our observations suggest that reducing FBG levels may potentially ameliorate cognitive function following stroke. However, contrasting evidence from other studies indicates that the use of FBG antagonists in patients with AIS may elevate the risk of bleeding events, including symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage35,36. Therefore, carefully monitoring and controlling FBG levels and other coagulation parameters throughout the treatment is needed32. Nonetheless, Gupta et al.37 observed elevated plasma FBG levels in dementia patients compared to controls in a cohort study, albeit without reaching statistical significance. Borroni and his colleagues38 reported no statistically significant variances in plasma FBG levels between patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and age-matched control subjects. The heterogeneity observed in the aforementioned studies could stem from variations in sample selection, sample size, and duration of follow-up. Overall, comprehensive exploration and validation are warranted to elucidate the effects and underlying mechanisms of FBG on cognitive impairment.

However, there are some limitations to this study. Firstly, study’s generalizability is limited by the exclusion of younger patients and the inadequate sample size, potentially limiting its applicability in guiding clinical practice. Secondly, our study had a limited number of confounding factors included, overlooking the potential impact of factors such as medication use, sleep quality, and social support on CI. Thirdly, due to some limitations, we only assessed the overall levels of FBG, rather than distinguishing between the different subunits (α, β, γ) of FBG. This limitation restricts our understanding of the more precise mechanisms by which FBG affects post-stroke neuroinflammation and BBB disruption. In addition, patients were assessed only once with FBG levels and neuropsychological scales, which did not allow for dynamic observation of the correlation between FBG changes and cognitive function. In conclusion, in future studies, we will expand the sample size, enrich the inclusion population, and comprehensively collect clinical information from patients to further explore the specific mechanisms by which FBG affects CI.

Conclusion

The present study indicates an association between elevated FBG levels and the incidence of CI among AIS patients. Elevated plasma FBG levels are linked to poorer cognitive function and reduced activity. Additionally, when combined with other common clinical indicators, plasma FBG can more effectively predict the onset of CI. Altering the constituents of coagulation and blood viscosity, including FBG, could potentially offer benefits in the prevention and management of cognitive dysfunction. Additional research is warranted to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms underpinning the relationship between elevated FBG levels and the risk of CI.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (https://www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Author contributions

Chunxiao Wei: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization, Validation. Weijie Zhai: Data curation. Panpan Zhao: Validation. Li Sun: Writing - review & editing, Validation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82071442), and the Jilin Provincial Department of Finance (JLSWSRCZX2021-004).

Data availability

Te datasets used and/or analyze during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

6. References

- 1.Swartz, R. H. et al. Post-stroke depression, obstructive sleep apnea, and cognitive impairment: rationale for, and barriers to, routine screening. Int. J. Stroke11(5), 509–518. 10.1177/1747493016641968 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mijajlovic, M. D. et al. Post-stroke dementia—a comprehensive review. Bmc Med.15, 11. 10.1186/s12916-017-0779-7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Aam, S. et al.Post-stroke cognitive impairment-impact of follow-up time and stroke subtype on severity and cognitive profile: the Nor-COAST study. Front. Neurol.11, 699. 10.3389/fneur.2020.00699 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng, Y. W. et al. The contribution of vascular risk factors in neurodegenerative disorders: from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther.12(1), 91. 10.1186/s13195-020-00658-7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davalos, D. & Akassoglou, K. Fibrinogen as a key regulator of inflammation in disease. Semin. Immunopathol.34(1), 43–62. 10.1007/s00281-011-0290-8 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lominadze, D., Dean, W. L., Tyagi, S. C. & Roberts, A. M. Mechanisms of fibrinogen-induced microvascular dysfunction during cardiovascular disease. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.)198(1), 1–13. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02037.x (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zlokovic, B. V. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron57(2), 178–201. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petersen, M. A., Ryu, J. K. & Akassoglou, K. Fibrinogen in neurological diseases: mechanisms, imaging and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.19(5), 283–301. 10.1038/nrn.2018.13 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang, W. et al. Kellerin alleviates cognitive impairment in mice after ischemic stroke by multiple mechanisms. Phytother. Res.34(9), 2258–2274. 10.1002/ptr.6676 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim, H. et al. AIM2 inflammasome contributes to brain injury and chronic post-stroke cognitive impairment in mice. Brain Behav. Immun.87, 765–776. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.011 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen, D. V., Hanson, J. E. & Sheng, M. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell. Biol.217(2), 459–472. 10.1083/jcb.201709069 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallacher, J. et al. Is sticky blood bad for the brain? Hemostatic and inflammatory systems and dementia in the Caerphilly prospective study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.30(3), 599–604. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.197368 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Oijen, M., Witteman, J. C., Hofman, A., Koudstaal, P. J. & Breteler, M. M. Fibrinogen is associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Stroke36(12), 2637–2641. 10.1161/01.STR.0000189721.31432.26 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marioni, R. E. et al. Peripheral levels of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, and plasma viscosity predict future cognitive decline in individuals without dementia. Psychosom. Med.71(8), 901–906. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b1e538 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroke–1989. Recommendations on stroke prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Report of the WHO Task Force on Stroke and other Cerebrovascular disorders. Stroke20(10), 1407–1431. 10.1161/01.str.20.10.1407 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Liu, J. H. et al. Elevated blood neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in older adults with cognitive impairment. Arch. Gerontol. Geriat.88, 104041. 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104041 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Adams, H. P. Jr. et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke24(1), 35–41. 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyden, P. et al. Improved reliability of the NIH Stroke Scale using video training. NINDS TPA Stroke Study Group. Stroke25(11), 2220–2226. 10.1161/01.str.25.11.2220 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pyun, J. M., Ryoo, N., Park, Y. H. & Kim, S. Fibrinogen levels and cognitive profile differences in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord.49(5), 489–496. 10.1159/000510420 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou, Z. et al. Fibrinogen and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.112, 353–360. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.02.022 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei, C. C. et al. Association between fibrinogen and leukoaraiosis in patients with ischemic stroke and atrial fibrillation. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis.26(11), 2630–2637. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.06.027 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Adams, R. A., Passino, M., Sachs, B. D., Nuriel, T. & Akassoglou, K. Fibrin mechanisms and functions in nervous system pathology. Mol. Interv.4(3), 163–176. 10.1124/mi.4.3.6 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood, H. Fibrinogen links vascular pathology to cognitive decline. Nat. Rev. Neurol.15(4), 187. 10.1038/s41582-019-0154-8 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merlini, M. et al. Fibrinogen induces microglia-mediated spine elimination and cognitive impairment in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Neuron101(6), 1099–108e6. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.014 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortes-Canteli, M., Mattei, L., Richards, A. T., Norris, E. H. & Strickland, S. Fibrin deposited in the Alzheimer’s disease brain promotes neuronal degeneration. Neurobiol. Aging36(2), 608–617. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.10.030 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schachtrup, C. et al. Fibrinogen triggers astrocyte scar formation by promoting the availability of active TGF-beta after vascular damage. J. Neurosci.30(17), 5843–5854. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0137-10.2010 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armulik, A. et al. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature468(7323), 557–561. 10.1038/nature09522 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muradashvili, N., Tyagi, N., Tyagi, R., Munjal, C. & Lominadze, D. Fibrinogen alters mouse brain endothelial cell layer integrity affecting vascular endothelial cadherin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.413(4), 509–514. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.133 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, S. J. et al. Association of fibrinogen level with early neurological deterioration among acute ischemic stroke patients with diabetes. BMC Neurol.17 (1), 101. 10.1186/s12883-017-0865-7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahn, H. J., Chen, Z. L., Zamolodchikov, D., Norris, E. H. & Strickland, S. Interactions of beta-amyloid peptide with fibrinogen and coagulation factor XII may contribute to Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Opin. Hematol.24(5), 427–431. 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000368 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atkinson, R. P. Ancrod in the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. Drugs54(Suppl 3), 100–108. 10.2165/00003495-199700543-00014 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen, J., Sun, D., Liu, M., Zhang, S. & Ren, C. Defibrinogen therapy for acute ischemic stroke: 1332 consecutive cases. Sci. Rep.8(1), 9489. 10.1038/s41598-018-27856-6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo, Y. et al. Meta-analysis of defibrase in treatment of acute cerebral infarction. Chin. Med. J. (Engl).119(8), 662–668 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahn, H. J. et al. A novel abeta-fibrinogen interaction inhibitor rescues altered thrombosis and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease mice. J. Exp. Med.211(6), 1049–1062. 10.1084/jem.20131751 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hao, Z. et al. Fibrinogen depleting agents for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.2012(3), CD000091. 10.1002/14651858.CD000091.pub2 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Levy, D. E. et al. Ancrod in acute ischemic stroke: results of 500 subjects beginning treatment within 6 hours of stroke onset in the ancrod stroke program. Stroke40(12), 3796–3803. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.565119 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta, A. et al. Coagulation and inflammatory markers in Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia. Int. J. Clin. Pract.59(1), 52–57. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00143.x (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borroni, B. et al. Peripheral blood abnormalities in Alzheimer disease: evidence for early endothelial dysfunction. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord.16(3), 150–155. 10.1097/00002093-200207000-00004 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Te datasets used and/or analyze during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.