Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide with abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) and renal artery stenosis (RAS) standing out as significant contributors to the vascular pathology spectrum. While these conditions have traditionally been approached as distinct entities, emerging evidence suggests a compelling interdependent relationship between AAA and RAS, challenging the conventional siloed understanding. The confluence of AAA and RAS represents a complex interplay within the cardiovascular system, one that is often overlooked in clinical practice and research. Here, we reveal a bidirectional consequential impact between these two diseases. The location of the AAA sac was investigated for its specific influence on the risk of RAS development. Although studies have shown a higher coincidence between the suprarenal AAA and RAS, our findings demonstrated that the presence of a suprarenal AAA correlated with the lowest risk of RAS development among the three investigated AAA locations. Notably, we also highlighted that the pre-existence of stenosis in the renal artery poses an elevated risk for the formation of suprarenal AAA, assessed by an increased wall shear stress gradient on the aortic wall. Our findings prompt a paradigm shift in the understanding and treatment of AAA and RAS in clinical practice.

Subject terms: Biomedical engineering, Cardiovascular diseases

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is defined as the localised dilation of the abdominal aorta with a diameter greater than 30 mm1. Among the two types of AAA, namely saccular and fusiform, the fusiform variant emerges as the more prevalent type2, characterised by its spindle shape with a central bulge. While the exact pathophysiology of AAA remains unclear, changes in wall shear stress (WSS) and WSS gradient have been the most widely studied parameters and indicators of AAA formation3. Specifically, non-uniformity in WSS has been identified as the main driving factor that damages endothelial cells and promotes inflammatory cell adhesion, culminating in vessel dilation and AAA formation4. Continued enlargement of the AAA sac can lead to potential rupture and internal bleeding which have been reported to have high mortality rates of 65 to 85%. Apart from the risk of rupture, renal failure has been highlighted to be a separate complication of AAA development5. While the manifestation of AAA is largely asymptomatic, AAA presents a serious health problem, necessitating greater attention and a more dependable predictor.

There are three morphological classes of AAA depending on the distance between the superior apex of the AAA bulge and the renal arteries6. They are namely: (1) suprarenal AAA which extends above the renal arteries, (2) juxtarenal AAA formed directly below the horizontal axis of the renal arteries and (3) infrarenal AAA which are typically ≥ 10 mm distal to the renal arteries7. Amongst these three types of AAAs, the infrarenal class is the most common, constituting approximately 80% of all cases. Following closely is the juxtarenal presentation, accounting for approximately 18%, while suprarenal AAA exhibits the lowest prevalence at around 2%8.

Renal artery stenosis (RAS) is defined as the narrowing of one or both renal arteries. Similar to other arterial diseases, the development of RAS and the consequent renal failure is associated with changes in hemodynamics, characterised by phenomena like regions of flow recirculation and low WSS9. Accounting for up to 90% of RAS cases, atherosclerotic RAS primarily affects the proximal third of the renal arteries, approximately 1 to 2 cm distal to the renal-aorta bifurcation10,11. The atherosclerotic plaque impairs blood flow to the kidneys which consequently leads to chronic renal failure and renovascular hypertension12. Thus far, it is difficult to determine the true prevalence of RAS as they are often incidental findings when patients are screened for other peripheral arterial diseases or coronary heart diseases13,14.

Interestingly, the initiation and advancement of both diseases are impacted by comparable triggers, including abnormal hemodynamic flow profiles and biomechanical factors such as alterations of the WSS. Furthermore, given the physical proximity of these two diseases, this suggests a potential for mutual influence. Several observational studies have identified the concomitant occurrence of AAA and RAS15,16. These findings have hinted that the presence of AAA may affect the hemodynamic profile in renal arteries which results in consequent RAS formation and vice versa. Specifically, it appears that the location of the aneurysm sac has a bearing on the development of RAS. Studzińska et al. found that the presence of RAS was more common in suprarenal AAA patients as compared to infrarenal AAA patients17, suggesting a possible mechanism between the proximity of the AAA sac to the renal arteries and RAS development. Furthermore, Javadzadegan et al. showed that a superior location of the aneurysm sac relative to the renal arteries has a greater and more detrimental impact on the flow dynamics within the renal arteries as compared to the inferiorly located aneurysm18. Despite these observations, the developmental connection between these two diseases is hitherto unknown and there has been no study to date which conclusively demonstrated the correlation between AAA location and RAS development.

Here, we employ computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to scrutinise the influence of fusiform AAA sac positions on renal artery hemodynamics and explore the potential reciprocal relationship between AAA and RAS. Surprisingly, we observed that an increased proximity of AAA to the renal arteries correlates with a reduced risk of RAS formation, with the suprarenal AAA model exhibiting the lowest risk of RAS development among all the AAA models. Furthermore, we show that the dynamics are intricately interlinked, as the presence of an initial RAS seems to augment the risk of aneurysm development. Collectively, our study adds to current understanding of the interconnected relationship between AAA and RAS, offering insights that could shape future approaches to cardiovascular disease diagnosis and treatment.

Methodology

Geometric model generation

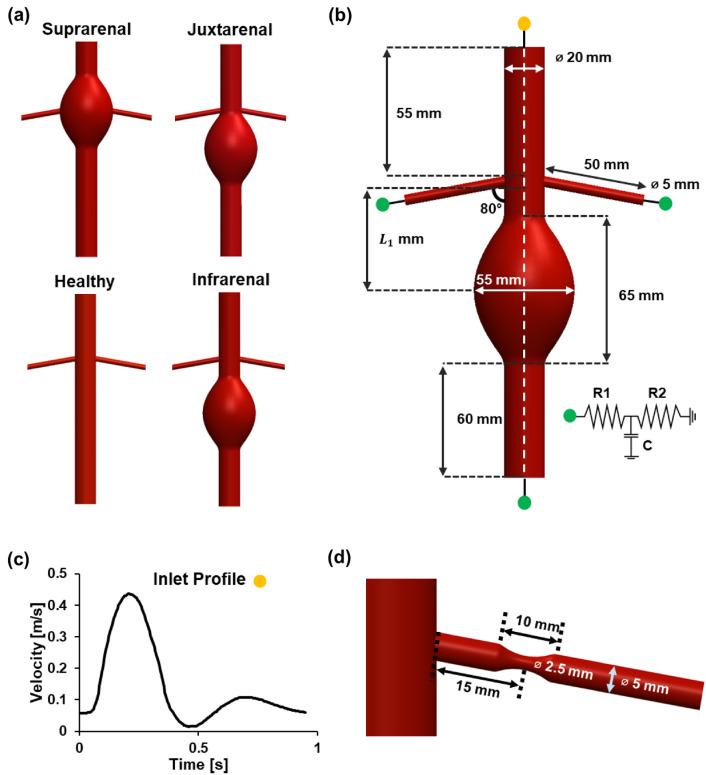

The catalogue of models utilised in this project was constructed using a computer-aided design software (Dassault Systèmes SOLIDWORKS Corp, MA, USA), capturing physiologically representative dimensions. A total of five models were constructed for this study. Three types of aneurysm case study models were created: (1) infrarenal AAA, (2) juxtarenal AAA and (3) suprarenal AAA, in addition to a fourth “healthy” abdominal aorta model which serves as a baseline for quantitative comparison (Fig. 1a). The implementation of vasoconstricted regions in both renal arteries of the healthy model constitutes the fifth “stenosed” model (Fig. 1d). All geometries constructed were idealised, three-dimensional models with simplified geometry to provide consistency and standardisation given the parametric nature of this study. Across all models, the healthy segments of the aorta were structured to be 20 mm19 in diameter and the height of each model was kept constant at 200 mm. The abdominal aortic sac was modelled to be axisymmetric with an axial length of 65 mm and a maximum aneurysmal diameter of 55 mm which is the lower threshold value for surgical intervention20 (Fig. 1b). The distance between the central core of the aneurysmal sac to the entrance of the renal arteries, L1 was varied for each of the AAA models (Table 1). The renal arteries measured 50 mm lengthwise21 with a diameter of 5 mm and an angle of 80° extending from the central (aortic) axis18,22. Stenosed regions in the renal artery were modelled as 10 mm sections featuring reductions in internal diameter along the renal artery axis23, with a maximum reduction of 50% at the stenosis apex that was situated 15 mm from the entrance of the renal artery, resembling the common proximal renal artery stenosis that occurs within one-third of the renal artery length from the entrance10,24.

Fig. 1.

Geometry of the simulated models and the corresponding boundary conditions. (a) Symmetric models of infrarenal, juxtarenal and suprarenal AAA were used for the simulations. A healthy abdominal aorta model was designed as a control for the comparative study. (b) Infrarenal AAA model with dimensions used for construction and applied boundary conditions indicated by green and yellow labels. Velocity Boundary condition was established with a velocity inlet (yellow) and 3-element Windkessel outlets (green). (c) The inlet boundary condition was characterised by a velocity waveform mimicking the pulsatile flow nature in the abdominal aorta. (d) Close-up view of the renal artery in the stenosis model with dimensions used for model construction.

Table 1.

distance of respective AAA models.

| Model | |

|---|---|

| Infrarenal | 52.5 mm |

| Juxtarenal | 32.5 mm |

| Suprarenal | 0 mm |

Mesh generation

Adaptive meshing was applied for the meshing of all models using ANSYS 2021 R2 (ANSYS Inc., PA, USA). Due to the geometric complexity, tetrahedral meshing was used to generate unstructured linear mesh across the computational domain. As the region of interest (ROI) lies in the vicinity of the bifurcation point, the element size for the aorta and renal artery regions was set at a ratio of 1:2 and a growth rate of 1.1 to attain refined meshes within the ROI. To attain a better resolution of the WSS, inflation consisting of 10 layers was applied to all models. The first layer height was defined to be 0.04 mm and 0.024 mm for the aorta and renal arteries respectively. Further refinements along the bifurcation region were performed to capture the curvature of the renal arterial entrance and generate a smooth transition zone between aortic and renal artery walls.

Governing equations

The CFD simulations were performed using ANSYS FLUENT (2021 R2, ANSYS Inc., PA, USA). Blood was assumed to be incompressible with a density of = 1050 kg/m3 and Newtonian with a constant viscosity = 0.0035 Pa·s. The fluid dynamics obey the continuity and unsteady momentum equations with the inclusion of gravity as the body force term.

| 1 |

| 2 |

Due to the turbulent nature of this study, the k-ω SST model was used to capture both the behavior of the mainstream fluid and the near-wall boundary layers25. The governing equations were solved using the SIMPLE solver with a combination of first- and second-order discretisation techniques. The convergence criterion was set to 10–6. A total of six cycles (T = 0.95 s per cycle) were run in each simulation to ensure flow stabilization. The resultant data for analysis was extracted from the final simulation cycle.

Boundary conditions

The inlet velocity profile was extracted from Alastruey et al.26 (Fig. 1c). The three-element Windkessel model was coupled to the models at each outlet to mimic the downstream conditions. Windkessel parameters were iteratively calculated using the method from Xiao et. al27. The mean pressure was then calculated from the desired diastolic () and systolic () pressures, which was used to estimate the net peripheral resistance (). Total compliance, was estimated using the empirical time constant τ = 1.79 s28

| 3 |

where is mean pressure and is average flow rate at the inlet. The proximal resistance of the aorta and renal arteries was estimated using the wave speed value , which was empirically formulated by Reymond et al.29:

| 4 |

where represents the vessel diameter in mm, is the diastolic luminal area of each vessel and is blood density. The distal resistance for each vessel was calculated by combining the flow rate ratio to each vessel and the following total resistance formula:

| 5 |

The total compliance was decomposed into (total arterial conduit compliance) and (total arterial peripheral). The Windkessel compliance C of each vessel was calculated from the total arterial compliance:

| 6 |

After each iteration, the new systolic pressure and diastolic pressure obtained from the simulation were used to adjust the value of and using the algorithm mentioned in Xiao et al27. A total of four iterations were performed for each model to obtain the inlet pressure within the desired range of 121/78 mmHg26. The finalised values of the Windkessel parameters for each model are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Windkessel parameters of abdominal aortic outlet and renal artery outlets.

| Abdominal Aorta outlet | Renal outlet | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rp [× 108 Pa s/m3] | Rd [× 108 Pa s/m3] | C [× 10–8 m3/Pa] | Rp [× 108 Pa s/m3] | Rd[× 108 Pa s/m3] | C [× 10–8 m3/Pa] | |

| Healthy | 0.181 | 5.8867 | 0.2479 | 4.3885 | 6.5338 | 0.2232 |

| Stenosis | 5.508 | 0.2647 | 5.8563 | 0.2489 | ||

| Infrarenal | 5.8988 | 0.2567 | 6.5601 | 0.2308 | ||

| Juxtarenal | 5.9261 | 0.2598 | 6.6092 | 0.2329 | ||

| Suprarenal | 5.9048 | 0.2592 | 6.5709 | 0.2329 | ||

Mesh and temporal independent study

To perform mesh sensitivity analysis, 3 mesh sizes were generated as M1 (fine), M2 (average) and M3 (coarse) with a decreasing number of corresponding tetrahedral elements. The element size was reduced by a constant refinement ratio = 1.7 for all cases. The respective maximal WSS values of the renal artery (f1, f2, f3) were obtained after running steady simulations using a maximal inlet flow rate (8.5 L/min). To determine which mesh to use for the subsequent simulations, Richardson extrapolation was adopted30,31. First, the order of convergence was determined by:

| 7 |

The continuum solution at grid spacing h = 0, the exact solution , was extrapolated using the following formula:

| 8 |

The relative error (ε) between solutions and the grid convergence index (GCI) were then defined as:

| 9 |

where is the factor of safety, which has the value 1.25 for the case of three meshes29. and were calculated using the above equations, which were then used to calculate the asymptotic range (AR):

| 10 |

A valid Richardson extrapolation result should have f1, f2 and f3 within the AR. Therefore, an AR close to unity was used to validate the generated meshes. Results of the mesh independence study are plotted in Fig. S1. For temporal independent study, a series of time-steps ranging from 0.01 s down to 0.001 s was used for the simulation of each geometric model. The area- and time-averaged wall shear stress of the renal arteries were used to establish time-step convergence curves (Fig. S2). A time step of 0.005 s was eventually selected for all models for subsequent data analysis.

Hemodynamic quantities

ANSYS CFD-post (version 21.0, ANSYS Inc., PA, USA) was used for flow visualisation and data analysis. Stenosis occurs in regions of low WSS which promotes the onset of atherosclerosis. Two WSS-based risk factors—(1) oscillating shear index (OSI) and (2) relative residence time (RRT)—were used to assess the risk of atherosclerosis32–34, which are derived from the time-averaged WSS (TAWSS):

| 11 |

In which, is the WSS vector defined at a specific point r in space at timepoint t, calculated by taking the shear component of the traction vector. The susceptible regions can be identified using the following parameters:

1. Oscillating Shear Index (OSI):

| 12 |

2. Relative Residence Time (RRT):

| 13 |

where represents the cardiac cycle of 0.95 s used in our simulations.

OSI and RRT are metrics derived from TAWSS. TAWSS is the time-averaged value of the WSS vector magnitude, however it lacks information about the temporal variation of flow direction. Therefore, it has been insinuated in several studies to be a less robust predictor of stenosis development. In contrast, the tandem evaluation of OSI and RRT was shown to be a more reliable predictor. The coincident OSI characterizes flow pulsatility and quantifies the oscillations of fluid velocity about a mean value close to zero25 whereas RRT is related to the time-mean of shear rate and inversely proportional to TAWSS for a non-oscillating flow. In most cases, increased risk of atherosclerosis has been shown to be associated with high OSI and high RRT35–37.

We further analysed the localisation of Dean vortices in the renal arteries. The swirling property of blood has been shown to exhibit atheroprotective effects, as it enhances oxygen transfer and mitigates flow stagnation38. The strength of vortices was quantified using helicity, which is defined as the absolute value of the dot product of the velocity and vorticity vectors which signifies the swirling effect along the blood flow direction:

| 14 |

| 15 |

The spatial gradient of WSS on the aortic wall was calculated, extending 10 mm around the circumference of the renal entrance. This computation was undertaken to quantify the risk of AAA development. High TAWSS and TAWSSG (TAWSS gradient) were considered to be a common hemodynamic factor inducing vascular aneurysm4,32.

| 16 |

Results

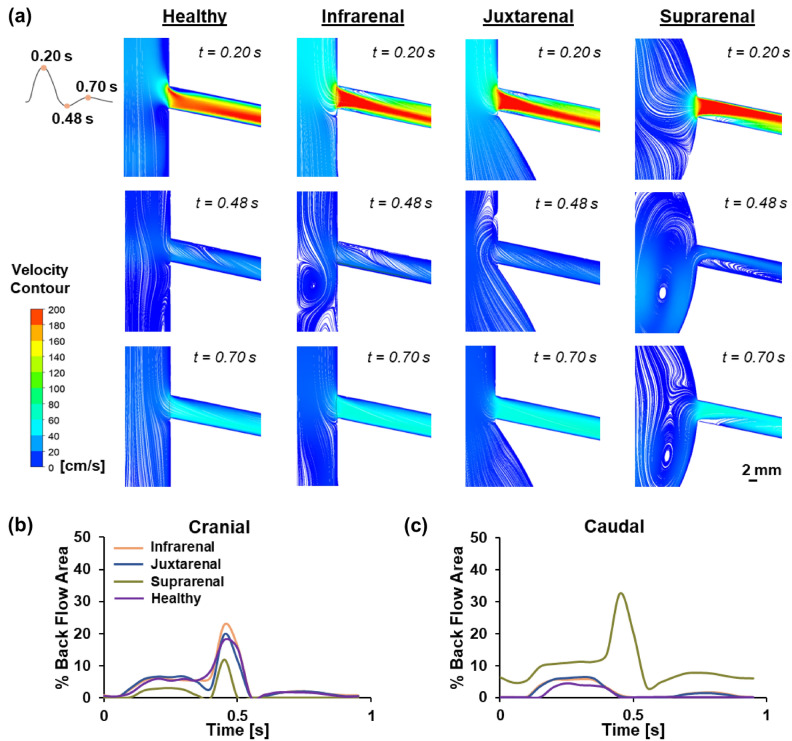

Backflow is typically associated with stenosis formation, and quantifying backflow allows for the determination of regions in the blood vessel more susceptible to stenosis. Visualising the locations of backflow in the respective AAA models was achieved by plotting velocity flow streamlines (Fig. 2a). Three timepoints were selected for comparative analysis, namely (1) peak systole, (2) end systole and (3) mid diastole (0.20 s, 0.48 s and 0.70 s respectively). Quantification of the percentage backflow area (BFA) with time was performed for both the cranial (Fig. 2b) and caudal (Fig. 2c) sides of the renal artery across the different AAA models. In the healthy model, backflow and recirculation were observed during systole along both the cranial and caudal sides of the renal artery, plateauing at peak systole with a BFA of 5.9% and 4.5% respectively. Approaching end systole, BFA continued to increase and peaked at 18.1% on the cranial side. On the other hand, backflow was observed to dissipate in the caudal side of the artery. Backflow on the cranial side of the renal artery diminished with time and reappeared as it approached peak diastole, reaching a peak BFA of 1.6%. However, no backflow was observed in caudal side.

Fig. 2.

Assessment of backflow in AAA models. (a) Velocity flow profiles of the healthy and three AAA models across 3 timepoints (0.20 s, 0.48 s and 0.70 s). (b) Percentage backflow area (BFA) on the cranial side of the renal artery. (c) Percentage backflow area (BFA) on the caudal side of the renal artery.

In the infrarenal AAA model, backflow and recirculation were observed during systole along both cranial and caudal sides of the renal artery, plateauing at peak systole with a BFA of 6.1% and 5.6% respectively. Approaching end systole, BFA continued to increase and peaked at 22.8% on the cranial side. On the other hand, backflow was observed to dissipate in the caudal side of the artery. Backflow on the cranial side of the renal artery diminished with time and reappeared as it approached peak diastole, reaching a peak BFA of 2.0%. Concomitantly, a peak BFA of 1.6% was observed on the caudal side of the artery. The juxtarenal AAA model showed a comparable trend to the infrarenal AAA model, featuring backflow and recirculation on both cranial and caudal sides of the renal artery during systole, plateauing at peak systole with a BFA of 6.7% and 6.4% respectively. BFA on the cranial side exhibited a slight decrease before gradually increasing and reaching a peak of 19.9% as it approached end systole, coinciding with the dissipation of backflow on the caudal side. Backflow on the cranial side subsequently decayed sharply as it approached diastole, but reemerged with a BFA of 2.1% at peak diastole. The backflow generation at peak diastole was also observed on the caudal side of the artery, where the BFA reached a maximum of 1.4%.

On the contrary, the suprarenal AAA model exhibited a distinct pattern characterised by the presence of higher backflow on the caudal side as compared to the cranial side of the renal artery. Additionally, in the suprarenal AAA model, there is a notably longer recirculation length which extends downstream from the entrance of the renal artery, up to a length of 10 mm. This results in a consistently higher BFA in the caudal region of the renal artery in the suprarenal AAA model. Similar to the other two AAA models, at peak systole, the suprarenal AAA model showed a BFA which plateaued at approximately 3.0% and 11.2% on the cranial and caudal side of the renal artery respectively. Backflow on the cranial side of the renal artery was observed to subsequently decrease with time, displaying a reversal and reaching a peak of 11.8% at end-systole. Interestingly, on the caudal side of the renal artery, the backflow was observed to gradually increase with time and the BFA peaked at 32.6% at end systole. Approaching diastole, backflow was observed to be diminished in both the cranial and caudal regions. However, a reversal was observed only in the caudal region of the renal artery with a BFA of approximately 7.7% at peak diastole.

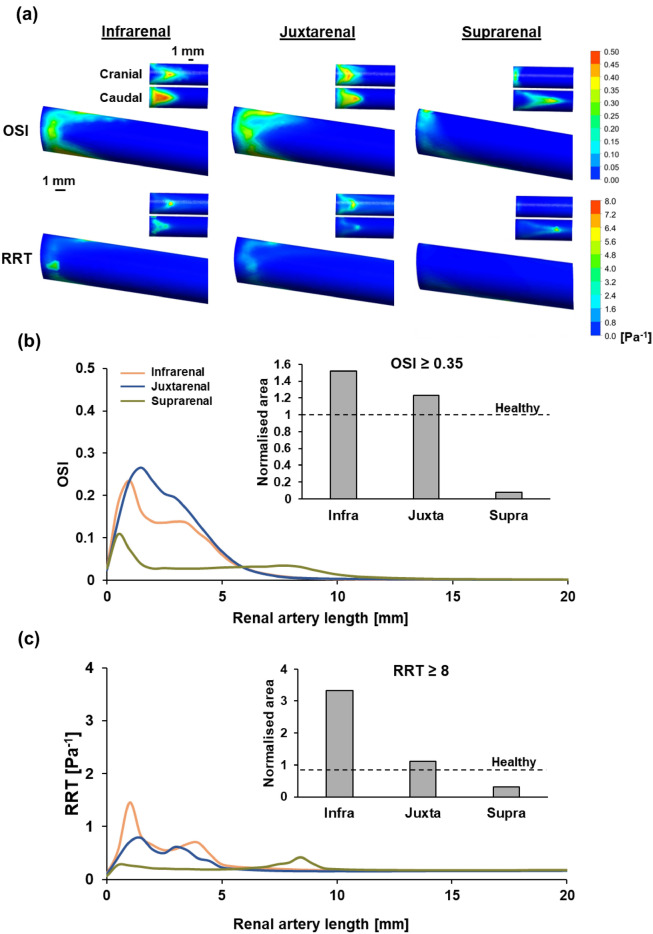

Surface plots of the renal artery were utilised for qualitative analysis, emphasising regions along the circumference of the artery characterised by elevated levels of two stenosis risk indicators: (1) OSI and (2) RRT. Both the cranial and caudal regions of the renal artery in each case were highlighted to facilitate clear identification of high-risk areas (Fig. 3a). Infrarenal and juxtarenal AAA models exhibited high levels of OSI and RRT, distributed across the entrance of the renal artery and focused in both the cranial and caudal regions of the renal artery. It is crucial to emphasise the marked difference in OSI magnitude noted between these two cases, with the infrarenal AAA model exhibiting concentrated regions with higher OSI magnitude despite displaying a lower overall surface inflicted with elevated OSI. This trend is further evident in the analysis of RRT, where a similar pattern was observed for the infrarenal AAA model, revealing a focused region with higher RRT levels found on the cranial side of the arterial wall despite having a visibly smaller area of elevated RRT levels when compared with the juxtarenal AAA model. On the contrary, the suprarenal AAA model exhibited lower OSI and RRT levels when compared with the former two models. Heightened OSI and RRT regions were primarily concentrated in the caudal region of the artery. Congruent with the extended recirculation length observed from the velocity streamlines of the suprarenal AAA model, the areas with heightened OSI and RRT were observed to extend further downstream of the renal artery as compared to the other two AAA models.

Fig. 3.

Quantification of stenosis risk in different AAA models based on OSI and RRT. (a) Surface plots of the renal artery for all AAA models illustrating regions of high OSI and RRT. Insets provide closer examination of the cranial and caudal parts of the renal artery. (b) Circumferential averaged OSI with normalised area of renal artery having OSI > 0.35 across all models. (c) Circumferential averaged RRT with normalised area of renal artery having RRT > 8 Pa−1 across all models.

Quantitative analysis of OSI and RRT was done using two approaches: (1) circumferential average measured across the length of the renal artery and (2) normalised area of the renal artery that exceeds the known thresholds of OSI and RRT. Employing both of these methodologies served to emphasise the specific regions along the length of the renal artery prone to high stenosis risk and allowed for a more distinct differentiation of the actual stenosis risk between each AAA model.

In all three models, the circumferential averaged OSI was notably elevated near the entrance of the renal artery within the initial 2.5 mm. The juxtarenal AAA model exhibited the highest OSI circumferential average, peaking at 0.26, followed by infrarenal AAA with a peak of 0.24, and suprarenal AAA with a peak of 0.11. In the case of juxtarenal and infrarenal AAA, this was succeeded by a gradual decrease to 0 at a distance of 8 mm downstream. Conversely, in the suprarenal AAA model, a similar decrease was observed, but the OSI circumferential average plateaued at around 0.03 for up to 8 mm downstream before gradually diminishing to 0 (Fig. 3b).

Elevated levels of RRT were also evident near the entrance of the renal artery within the initial 5 mm, specifically in the cases of infrarenal and juxtarenal AAA. In the infrarenal AAA, two distinct peaks were identified at 0.98 mm and 3.95 mm downstream of the renal artery entrance, with values of 1.44 and 0.69 Pa−1 respectively. Similarly, the juxtarenal AAA model exhibited two distinct peaks at 1.47 mm and 2.96 mm downstream of the renal artery entrance, with values of 0.79 and 0.62 Pa−1 respectively. In both instances, the circumferential averaged RRT gradually diminished after the initial 5 mm of the renal artery, reaching a value of approximately 0.20 Pa−1. On the other hand, in the suprarenal AAA model, there was low circumferential averaged RRT observed within the initial 5 mm of the renal artery, stabilising at an average of approximately 0.20 Pa−1. This value gradually increased after the 5 mm mark and reached a peak of 0.41 Pa−1 at 8.4 mm downstream of the renal artery entrance, followed by a gradual decrease back to a value of 0.20 Pa−1 (Fig. 3c).

Establishing a definitive hierarchy of risk levels between models remains challenging, especially between infrarenal and juxtarenal AAA models. Therefore, we implemented thresholds to improve the resolution between models. The thresholds set were an OSI exceeding 0.35 and a RRT value surpassing 8 Pa−1. Exceeding these established thresholds implied a higher risk of RAS formation. These threshold values were derived from prior literature that investigated the risks associated with stenosis development37,39,40. The total area of the renal artery in all AAA models which exceeds the respective thresholds for these indicators was quantified and normalised with the healthy model representative (Fig. 3b,c insets). Overall, we observed a consistent trend between these two risk indicators, revealing that the infrarenal AAA exhibited the highest risk of stenosis formation amongst the 3 models. The risk was also observed to decrease with increased proximity to the renal artery (Normalised area with OSI ≥ 0.35—Infrarenal AAA: 1.52 vs Juxtarenal AAA: 1.23 vs Suprarenal AAA: 0.077) (Normalised area with RRT ≥ 8: Infrarenal: 3.33 vs Juxtarenal: 1.10 vs Suprarenal: 0.32). It is worth noting that the suprarenal AAA revealed an even lower risk of stenosis development as compared to the healthy model.

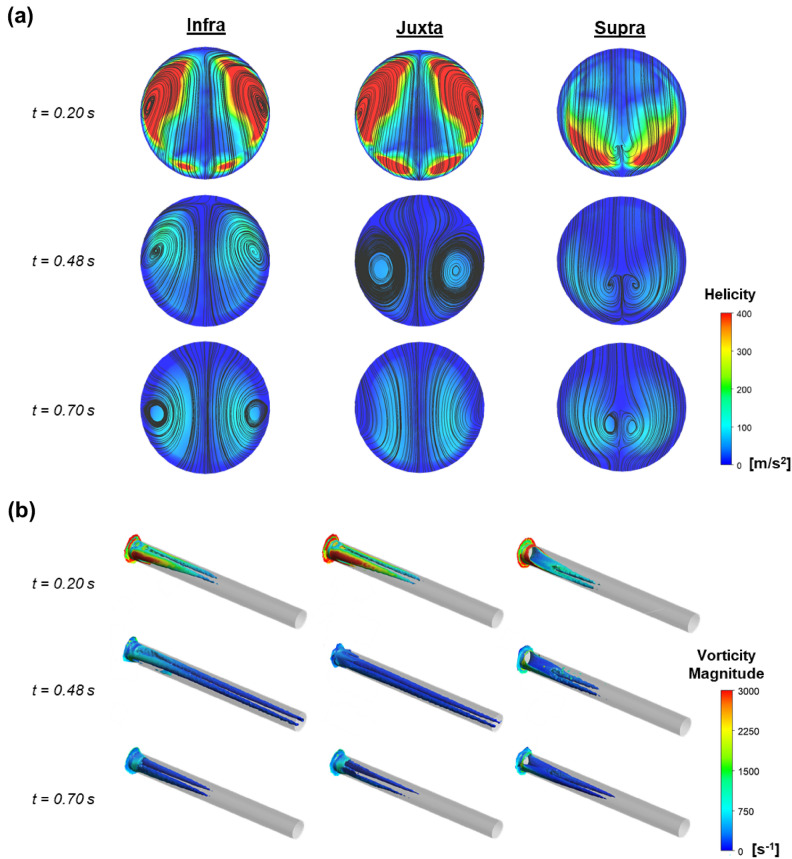

Extensive literature has confirmed that the flow in curved regions (i.e. bifurcations) experiences a blend of centrifugal forces induced by sudden change in direction and adverse pressure gradients, often resulting in secondary flow motions. The secondary flow behaviour manifests as vortical projections, mainly referred to as helical flow. These secondary flows significantly impact WSS and the exposure time of blood-borne particles, therefore it is closely associated with the development of cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis. In our case, it has bearing on the development of RAS.

The complex dynamics of helical blood flow across the different AAA models and the magnitude of vorticity downstream of the renal artery were visualised. The cross-sectional flow streamline displaying high spirality aligned with regions characterised by high helicity (Fig. 4a). The relationship between regions exhibiting heightened helicity and the regions with high vorticity within the renal artery was investigated. Our findings confirmed a consistent correlation between regions displaying high helicity and the presence of elevated vorticity across the renal artery downstream (Fig. 4b). Specifically, in both the infrarenal and juxtarenal AAA models, we observed that areas with prominent helicity were predominantly concentrated along the ventral and dorsal regions of the renal artery. Notably, these regions shifted caudally with time, indicating a sustained influence on the flow dynamics. In contrast, the suprarenal AAA model revealed regions demonstrating heightened spirality and high vorticity that were primarily located at the caudal region of the renal artery. These regions of high helicity maintained their position over time, highlighting a distinct pattern in the helical flow dynamics specific to suprarenal AAA.

Fig. 4.

Comparing regions of renal helical flow between AAA models across 3 different timepoints. (a) Cross-sectional view of velocity streamlines showing regions of high helicity. (b) Peripheral view of the renal artery showing the propagation of vorticity downstream of the vessel branch.

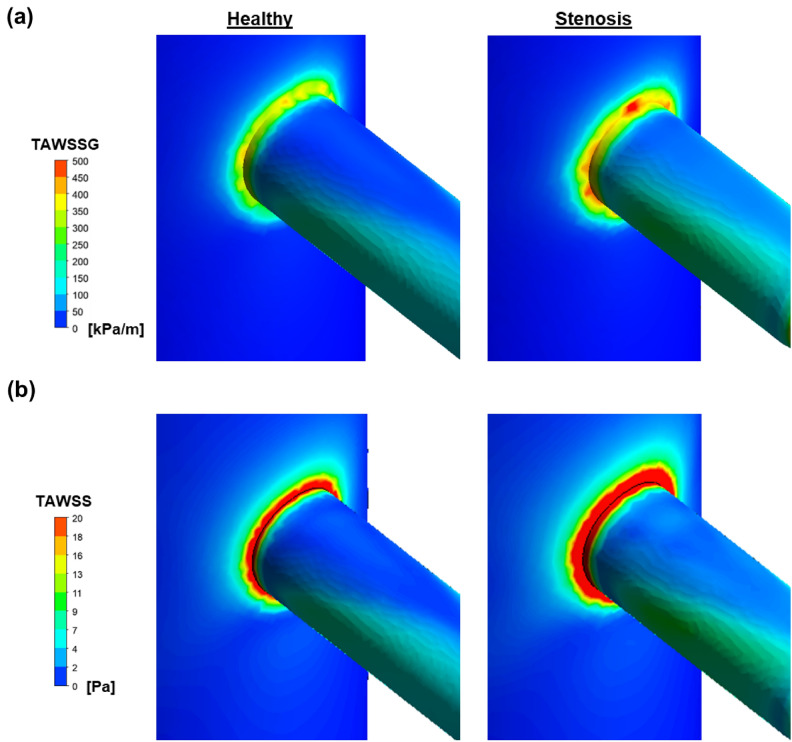

The infrequent occurrence of suprarenal AAA cases compared to other AAA cases, coupled with the notable prevalence of RAS in suprarenal AAA patients, prompts consideration of the possibility of initial RAS development preceding the formation of suprarenal AAA. In this segment of our study, we sought to investigate the distinctions between a healthy model and a stenosis model in relation to AAA risk development. Our approach involved employing TAWSS and its gradient (TAWSSG) as quantitative measures to assess differences in AAA risk.

Our findings revealed that the pre-existing presence of stenosis in the renal artery resulted in an elevation of both TAWSS and TAWSSG on the aortic wall surrounding the circumference of the renal artery. Specifically, TAWSSG showed a corresponding rise of 35.0% (Fig. 5a) while TAWSS exhibited a significant increase of 34.3% (Fig. 5b). Collectively, these demonstrate the increased risk in AAA development after renal artery stenosis. Specifically, the consistent elevation of both TAWSS and TAWSSG along the circumference of the renal artery suggests a possible predisposition toward suprarenal AAA formation.

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of TAWSS and TAWSSG on the aortic wall in both healthy and renal artery stenosis model. (a) TAWSSG comparison between healthy and stenosis model. (b) TAWSS comparison between healthy and stenosis model.

Discussion

The susceptibility of branching vessels in the circulation to stenosis onset has long been acknowledged, owing to the significant hemodynamic alterations occurring in these areas41. These alterations act as triggers and propagators in the atherosclerotic cascade42. Notably, recirculation zones are commonly found in these branching regions within blood vessels and they have been recognised for their role in promoting flow stasis, often associated with endothelial dysfunction43, atheroma formation, and thrombosis44. The initial part of our study focused on visualising these recirculation zones and quantifying the BFA in each AAA model to highlight the localisation of backflow and assess the severity of stenosis risk. Our results revealed that regions exhibiting a high BFA in the infra and juxtarenal AAA models were predominantly situated on the cranial side of the renal artery. This is expected due to the change in flow direction accompanied by impingement into the caudal vessel wall and flow detachment in the cranial region. Conversely, in the suprarenal AAA model, the areas with high BFA were primarily on the caudal side of the renal artery, likely induced by the bulged aortic wall at the entrance of the renal artery directly affecting blood flow into the artery.

Arterial blood flow exhibits a pulsatile nature45 owing to the transitions between systole and diastole. Consequently, endothelial cells undergo a constant shift between backward flow and forward flow during this dynamic period. Intriguingly, the modification of endothelial cells has been reported to not be solely attributed to such changes but also to an additional rotational motion of blood in the three dimensional space46. The rapidly reorienting shear stress places a unique burden on the endothelial cells, producing an area of non-elongated cells47, compromising cell internal fluidity, and modifying adhesion to neighbouring cells to increase local permeability48 to lipoprotein infiltration. This suggests that while the quantification of backflow area was able to give us an indication of where stenosis might occur, it was insufficient to arrive at a conclusive statement of stenosis risk between AAA models. Therefore, this prompted the use of more robust metrics for the assessment of stenosis risk (i.e. OSI and RRT). A vast majority of CFD studies of atherosclerotic lesions utilise the OSI and RRT measurands as hemodynamic indicators for stenosis risk profiling33. A comprehensive correlation between these two metrics has been established in literature49,50. Ensuring alignment between results derived from OSI and RRT was crucial in our study to validate findings: heightened OSI and RRT levels are associated with an increased atherosclerotic plaque formation. The use of TAWSS as a lone metric for stenosis was omitted in our study due to inconsistencies revealed in literature. Low TAWSS was shown to not necessarily guarantee an indication of high stenosis risk as seen from previous studies51,52.

The application of circumferential averages for both OSI and RRT unveiled areas along the renal artery prone to stenosis development across all AAA models, consistent with regions experiencing recirculation along the artery. However, the amalgamation of both high and low peaks in the measurement of circumferential averages can introduce ambiguity, complicating the accurate comparison and identification of the higher stenosis risk AAA model between cases. Therefore, the use of known thresholds for OSI and RRT were applied to establish the hierarchy of stenosis risk between AAA models. Consistent with previous studies, our findings demonstrated a notable correlation between OSI and RRT. This correlation revealed a distinct pattern where the risk of stenosis decreased with the proximity of the AAA sac to the renal artery.

Low and oscillatory shear stress have significant physiological implications and areas experiencing such flow are deemed to be more susceptible to lesion formation. An increase in oscillatory shear induces a dose-dependent attenuation of endothelial function in humans. This flow profile can reduce nitric oxide production53, trigger the synthesis of proinflammatory mediators, and recruit circulating monocytes, ultimately resulting in impaired flow-regulated vasorelaxation54,55. Moreover, it can lead to the reversal of the endothelium’s antiapoptotic, antiproliferative, and antioxidative functions. When endothelial cells are exposed to oscillatory flow, they lose the ability to align with the flow, undergo cytoskeletal remodeling, and exhibit increased permeability of intercellular gaps, facilitating macromolecule uptake between cells and contributing to vascular dysfunction. Pro-inflammatory mediators, adhesion molecule expression, and fatty streak formation significantly increase in regions corresponding to oscillatory shear exposure.

Although the areas exhibiting elevated OSI and RRT provided consistent insights into the differences in RAS risk among the models, the consideration of BFA introduced discrepancies between these established metrics. The presence of an extended recirculation length and notably high BFA in the caudal region of the supra AAA suggested a heightened risk of stenosis development. However, this contradicted the findings from our evaluation using OSI and RRT, which indicated that suprarenal AAA had the lowest risk of RAS formation. This apparent discrepancy highlights the intricate nature of the relationship between hemodynamic factors and stenosis development across various AAA models. Moreover, it underscores the necessity of identifying a primary metric or combination of metrics for quantifying stenosis risk and suggests the potential involvement of distinct mitigating factors.

Swirling blood flow is a widely acknowledged physiological phenomenon in blood vessels56–59. This helical movement of blood has demonstrated positive effects within the circulatory system through enhanced development of vortices in the blood circulation38. Specifically, this motion of blood has been identified as beneficial to alleviating flow disturbances and even reducing recirculation flow length. Furthermore, it has been observed to decrease the stagnation of low-density lipoprotein and impede the deposition of materials, thereby contributing to a reduction in the risks associated with stenosis development60. Remarkably, the presence of high vorticity across the renal artery of the suprarenal AAA model coincided with the recirculation zone and areas of elevated OSI and RRT, primarily located in the caudal region of the artery. This correlation offers a potential explanation for the lower risk of RAS observed in the suprarenal AAA model based on our used metrics. Conversely, in the infrarenal and juxta AAA models, where vortices were mainly concentrated along the ventral and dorsal regions of the renal artery, the mitigating effect of helical flow on stenosis development in the cranial and caudal regions may have been less pronounced.

Separately, regions of bifurcation have a propensity to promote downstream stenosis formation, flow impingement at the site of arteriolar bifurcations can also result in flow acceleration, subjecting neighbouring endothelial cells at the artery entrance to heightened frictional forces. The interaction of various hemodynamic factors, which includes elevated WSS coupled with heightened WSSG values has the potential to trigger degenerative alterations in the arterial wall, leading to the formation of aneurysms24,61. Specifically, the presence of high WSS and high WSSG has been previously observed to induce a unique gene expression in endothelial cells32. It was observed that there was an increased level of apoptosis and proliferation of these cells which resulted in a heightened turnover rate62,63. The increased turnover rate could potentially be a driving factor towards aneurysm initiation. The constant rearrangement of endothelial cells creates temporary gaps across the endothelium and disrupts the ability of these cells to maintain the smooth muscle quiescence needed for the wall integrity. This causes the endothelium to be more susceptible to mechanical damage. The increased WSS and WSSG resulting from nearby stenosis imply a more deleterious effect on the endothelium, potentially fostering the development of an AAA.

Though our study presents valuable insights, it also possesses certain limitations. Firstly, the geometric structures employed in our simulations were simplified straight tubes, devoid of any curvatures that may better mimic the physiological conditions of these vessels. However, due to the parametric nature of our investigation and the uniformity maintained across all models, the absence of curvatures is unlikely to significantly impact the comparative conclusions drawn from our findings. Secondly, the arterial walls were assumed to be rigid and blood was assumed to be a Newtonian fluid. The lack of wall compliance may have bearing on the overall calculations and therefore the absolute values derived from this study may not be directly applicable to real patient scenarios64. While it is known that blood is non-Newtonian, the use of a Newtonian fluid was reported to be acceptable for simulations65 with vessel diameters larger than 0.5 mm and experiencing high shear rates.

It is intriguing to see that the suprarenal AAA has the lowest risk of stenosis across all cases including the healthy model. Coupled with the low incidence of suprarenal AAA cases, this may suggest that the formation of a suprarenal AAA may potentially act as a compensatory mechanism by the body to counteract the hemodynamic changes induced by an initial stenosis formation. It may also be a consequence of initial infrarenal or juxta AAA formation which led to the manifestation of a stenosis and subsequent formation of an extended AAA. As the healthy model has a basal level of stenosis risk, future studies can look into whether angle of the renal artery relative to the aorta may have a bearing on RAS formation.

To the best of our knowledge, our study represents the first endeavour to comprehend the influence of physiological AAA locations on the development of RAS. Notably, our results revealed that the level of stenosis risk decreased with the increasing proximity of the AAA sac to the renal arteries, with the suprarenal AAA model displaying the lowest RAS risk. Given that the infrarenal AAA is the most prevalent form of AAA found in the human body and it actually has the highest risk of RAS development, it is important to identify the origin of this disease for early intervention. Furthermore, it was revealed that the pre-existence of a stenosis in the renal artery resulted in a higher tendency to generate a suprarenal AAA due to the weakening of the aortic walls along the circumference of the bifurcation zone between the abdominal aorta and the renal artery. This novel insight may reshape our understanding of the intricate relationships between AAA and RAS, prompting further exploration and investigation in the field.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the High-Performance Computing (HPC) centre from NUS IT for providing the use of ANSYS computational fluid dynamics software. This research was supported by the Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE) University Research Committee Tier 2 grant MOE-T2EP50121-0015.

Author contributions

J.Q.L., T.D.H., T.Y.S., J.H.G. and L.K. performed experiments; J.Q.L., T.D.H, T.Y.S, J.H.G and L.K. processed and analysed data; J.Q.L., T.D.H. and K.S.T. interpreted results of experiments; J.Q.L., T.D.H. and K.S.T. prepared figures; J.Q.L. and K.S.T. drafted the manuscript; J.Q.L., T.D.H. and K.S.T. edited and revised manuscript; J.Q.L, T.D.H. and K.S.T. did the conception and design of research; K.S.T. approved the final version of manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The author(s) have declared no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jiaqi Lim and Hung Dong Truong.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-83622-x.

References

- 1.Sakalihasan, N., Limet, R. & Defawe, O. D. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. The Lancet365, 1577–1589 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durojaye, M., Adeniyi, T. & Alagbe, O. Multiple saccular aneurysms of the abdominal aorta: A case report and short review of risk factors for rupture on CT scan. Ann. Ibadan Postgrad. Med.18, 178–180 (2020). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arzani, A. & Shadden, S. C. Characterizations and correlations of wall shear stress in aneurysmal flow. J. Biomech. Eng.138, 014503 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanweer, O., Wilson, T. A., Metaxa, E., Riina, H. A. & Meng, H. A comparative review of the hemodynamics and pathogenesis of cerebral and abdominal aortic aneurysms: Lessons to learn from each other. J. Cerebrovasc. Endovasc. Neurosurg.16, 335–349 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagiwara, S. et al. High incidence of renal failure in patients with aortic aneurysms. Nephrol. Dialys. Transplant.22, 1361–1368 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albrecht, T. et al. Pre-operative classification of abdominal aortic aneurysms with spiral CT: The axial source images revisited. Clin. Radiol.52, 659–665 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel, C. & Cohan, R. CT of abdominal aortic aneurysms. AJR. Am. J. Roentgenol.163, 17–29 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Budden, J. & Hollier, L. H. Management of aneurysms that involve the juxtarenal or suprarenal aorta. Surg. Clin. North Am.69, 837–844 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bokhari, S. W. & Faxon, D. P. Current advances in the diagnosis and treatment of renal artery stenosis. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med.5, 204–215 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lao, D., Parasher, P. S., Cho, K. C. & Yeghiazarians, Y. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 649–657 (Elsevier). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Kaatee, R. et al. Atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: ostial or truncal?. Radiology199, 637–640 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoepe, R., McQuillan, S., Valsan, D. & Teehan, G. Atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Hypertension: from basic research to clinical practice, 209–213 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Endo, M. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for renal artery stenosis and chronic kidney disease in Japanese patients with peripheral arterial disease. Hypertens. Res.33, 911–915 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aboyans, V. et al. Renal artery stenosis in patients with peripheral artery disease: Prevalence, risk factors and long-term prognosis. Eur. J. Vascul. Endovasc. Surg.53, 380–385 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olin, J., Melia, M., Young, J., Graor, R. & Risius, B. Prevalence of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis in patients with atherosclerosis elsewhere. Am. J. Med.88, 46N-51N (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonen, K., Gonen, T. & Gumus, B. Renal artery stenosis and abdominal aorta aneurysm in patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Eye27, 735–741 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Studzińska, D. et al. Infrarenal versus suprarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms: comparison of associated aneurysms and renal artery stenosis. Ann. Vascul. Surg.58, 248–254 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Javadzadegan, A., Simmons, A., Behnia, M. & Barber, T. Computational modelling of abdominal aortic aneurysms: Effect of suprarenal vs infrarenal positions. Eur. J. Mech.-B/Fluids61, 112–124 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gameraddin, M. Normal abdominal aorta diameter on abdominal sonography in healthy asymptomatic adults: impact of age and gender. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci.12, 186–191 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Algabri, Y., Rookkapan, S. & Chatpun, S. in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 012003 (IOP Publishing).

- 21.Schönherr, E. et al. Retrospective morphometric study of the suitability of renal arteries for renal denervation according to the Symplicity HTN2 trial criteria. BMJ Open6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Lauder, L. et al. Renal artery anatomy assessed by quantitative analysis of selective renal angiography in 1000 patients with hypertension. EuroIntervention14, 121 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakamiya, T. et al. Renal autotransplantation in a patient with resistant renal artery stenosis. J. Med. Cases7, 226–229 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metaxa, E. et al. Characterization of critical hemodynamics contributing to aneurysmal remodeling at the basilar terminus in a rabbit model. Stroke41, 1774–1782 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung, E. C., Lee, G.-H., Shim, E. B. & Ha, H. Assessing the impact of turbulent kinetic energy boundary conditions on turbulent flow simulations using computational fluid dynamics. Sci. Rep.13, 14638 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alastruey, J., Parker, K. H. & Sherwin, S. J. In 11th international conference on pressure surges. 401–443 (Virtual PiE Led t/a BHR Group Lisbon, Portugal).

- 27.Xiao, N., Alastruey, J. & Alberto Figueroa, C. A systematic comparison between 1‐D and 3‐D hemodynamics in compliant arterial models. Int. J. Numer. Methods Biomed. Eng.30, 204–231 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Simon, A. C. et al. An evaluation of large arteries compliance in man. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol.237, H550–H554 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reymond, P., Merenda, F., Perren, F., Rufenacht, D. & Stergiopulos, N. Validation of a one-dimensional model of the systemic arterial tree. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol.297, H208–H222 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Celik, I. B., Ghia, U., Roache, P. J. & Freitas, C. J. Procedure for estimation and reporting of uncertainty due to discretization in CFD applications. J. Fluids Eng.-Trans. ASME130 (2008).

- 31.Roache, P. J. Quantification of uncertainty in computational fluid dynamics. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech.29, 123–160 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dolan, J. M., Meng, H., Sim, F. J. & Kolega, J. Differential gene expression by endothelial cells under positive and negative streamwise gradients of high wall shear stress. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol.305, C854–C866 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ku, D. N., Giddens, D. P., Zarins, C. K. & Glagov, S. Pulsatile flow and atherosclerosis in the human carotid bifurcation. Positive correlation between plaque location and low oscillating shear stress. Arteriosclerosis5, 293–302 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Himburg, H. A. et al. Spatial comparison between wall shear stress measures and porcine arterial endothelial permeability. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol.286, H1916–H1922 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuchs, A., Berg, N. & Prahl Wittberg, L. Stenosis indicators applied to patient-specific renal arteries without and with stenosis. Fluids4, 26 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zarins, C. K. et al. Carotid bifurcation atherosclerosis. Quantitative correlation of plaque localization with flow velocity profiles and wall shear stress. Circ. Res.53, 502–514 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kashyap, V., Arora, B. & Bhattacharjee, S. A computational study of branch-wise curvature in idealized coronary artery bifurcations. Appl. Eng. Sci.4, 100027 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ha, H., Choi, W., Park, H. & Lee, S. J. Effect of swirling blood flow on vortex formation at post-stenosis. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H: J. Eng. Med.229, 175–183 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hou, J. et al. An in vivo data-based computational study on sitting-induced hemodynamic changes in the external iliac artery. J. Biomech. Eng.144, 021007 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ascuitto, R., Ross-Ascuitto, N., Guillot, M. & Celestin, C. Computational fluid dynamics characterization of pulsatile flow in central and Sano shunts connected to the pulmonary arteries: importance of graft angulation on shear stress-induced, platelet-mediated thrombosis. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg.25, 414–421 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakazawa, G. et al. Pathological findings at bifurcation lesions: the impact of flow distribution on atherosclerosis and arterial healing after stent implantation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.55, 1679–1687 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Traub, O. & Berk, B. C. Laminar shear stress: Mechanisms by which endothelial cells transduce an atheroprotective force. Arterioscleros. Thrombos. Vascul. Biol.18, 677–685 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gimbrone, M. A. Jr. & García-Cardeña, G. Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Circ. Res.118, 620–636 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Javadzadegan, A. et al. Flow recirculation zone length and shear rate are differentially affected by stenosis severity in human coronary arteries. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol.304, H559–H566 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peterson, L. H. The dynamics of pulsatile blood flow. Circ. Res.2, 127–139 (1954). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohamied, Y., Sherwin, S. J. & Weinberg, P. D. Understanding the fluid mechanics behind transverse wall shear stress. J. Biomech.50, 102–109 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, C., Baker, B. M., Chen, C. S. & Schwartz, M. A. Endothelial cell sensing of flow direction. Arterioscleros. Thrombos. Vasc. Biol.33, 2130–2136 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sei, Y. J., Ahn, S. I., Virtue, T., Kim, T. & Kim, Y. Detection of frequency-dependent endothelial response to oscillatory shear stress using a microfluidic transcellular monitor. Sci. Rep.7, 10019 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knight, J. et al. Choosing the optimal wall shear parameter for the prediction of plaque location—A patient-specific computational study in human right coronary arteries. Atherosclerosis211, 445–450 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rikhtegar, F. et al. Choosing the optimal wall shear parameter for the prediction of plaque location—A patient-specific computational study in human left coronary arteries. Atherosclerosis221, 432–437 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoi, Y., Zhou, Y.-Q., Zhang, X., Henkelman, R. M. & Steinman, D. A. Correlation between local hemodynamics and lesion distribution in a novel aortic regurgitation murine model of atherosclerosis. Ann. Biomed. Eng.39, 1414–1422 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang, C. et al. Flow patterns and wall shear stress distribution in human internal carotid arteries: The geometric effect on the risk for stenoses. J. Biomech.45, 83–89 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ziegler, T., Bouzourene, K., Harrison, V. J., Brunner, H. R. & Hayoz, D. Influence of oscillatory and unidirectional flow environments on the expression of endothelin and nitric oxide synthase in cultured endothelial cells. Arterioscleros. Thrombos. Vasc. Biol.18, 686–692 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou, J., Li, Y.-S. & Chien, S. Shear stress–initiated signaling and its regulation of endothelial function. Arterioscleros. Thrombos. Vasc. Biol.34, 2191–2198 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang, H. et al. Low shear stress induces inflammatory response via CX3CR1/NF-κB signal pathway in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Tissue Cell82, 102043 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stonebridge, P. & Brophy, C. Spiral laminar flow in arteries?. The Lancet338, 1360–1361 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stonebridge, P., Hoskins, P., Allan, P. & Belch, J. Spiral laminar flow in vivo. Clin. Sci. (London, England: 1979)91, 17–21 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Morbiducci, U. et al. In vivo quantification of helical blood flow in human aorta by time-resolved three-dimensional cine phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging. Ann. Biomed. Eng.37, 516–531 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caro, C. G. et al. Non-planar curvature and branching of arteries and non-planar-type flow. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci.452, 185–197 (1996).

- 60.Liu, X. et al. A numerical study on the flow of blood and the transport of LDL in the human aorta: The physiological significance of the helical flow in the aortic arch. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol.297, H163–H170 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meng, H. et al. A model system for mapping vascular responses to complex hemodynamics at arterial bifurcations in vivo. Neurosurgery59, 1094 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dolan, J. M., Meng, H., Singh, S., Paluch, R. & Kolega, J. High fluid shear stress and spatial shear stress gradients affect endothelial proliferation, survival, and alignment. Ann. Biomed. Eng.39, 1620–1631 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kolega, J. et al. Cellular and molecular responses of the basilar terminus to hemodynamics during intracranial aneurysm initiation in a rabbit model. J. Vasc. Res.48, 429–442 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pons, R. et al. Fluid–structure interaction simulations outperform computational fluid dynamics in the description of thoracic aorta haemodynamics and in the differentiation of progressive dilation in Marfan syndrome patients. R. Soc. Open Sci.7, 191752 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McDonald, D. A. Blood flow in arteries. (1974).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.