Abstract

This research presents an innovative approach for synthesizing 2-amino-4H-chromene derivatives, utilizing 30 mg of NS-doped graphene oxide quantum dots (GOQDs) as a catalyst in a one-pot, three-component reaction conducted in ethanol. The NS-doped GOQDs were synthesized using a cost-effective bottom-up method through the condensation of citric acid (CA) with thiourea and the reaction was carried out at 185 C, resulting in the elimination of water. The catalytic performance of the synthesized NS-doped GOQDs resulted in high product yields, achieving up to 98% for the 2-amino-4H-chromene derivatives from aromatic aldehydes, malononitrile, resorcinol, -naphthol, and dimedone. The reaction showcased rapid completion time (typically < 2 h), low-cost reagents, and easy work-up procedures. In addition, the study integrates experimental and theoretical analyses, including density functional theory (DFT) calculations, to investigate the electronic properties of the synthesized compounds. Calculated HOMO and LUMO energies indicate efficient charge transfer within the molecular structure. The FT-IR spectra of compound 4c were recorded in the range of 4000–500 cm, and vibrational frequencies were computed at the B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) level, correlating well with experimental data. Detailed analyses, including Mep surfaces, Mulliken population analysis, and Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis, provide further insights into the electronic distribution and reactivity of the compounds. Furthermore, comparative H and C NMR analyses of compound 4c reveal strong agreement between computational and experimental findings. This research not only validates the synthetic method but also emphasizes the dual experimental and computational approach in understanding the structural and electronic characteristics of the 4c compound.

Keywords: Multi-component reaction, Chromene, Graphene oxide, Electrophilicity index, NBO analysis, B3LYP/6-311+G(d, p)

Subject terms: Sustainability, Synthetic chemistry methodology, Reaction mechanisms, Computational chemistry, Density functional theory

Introduction

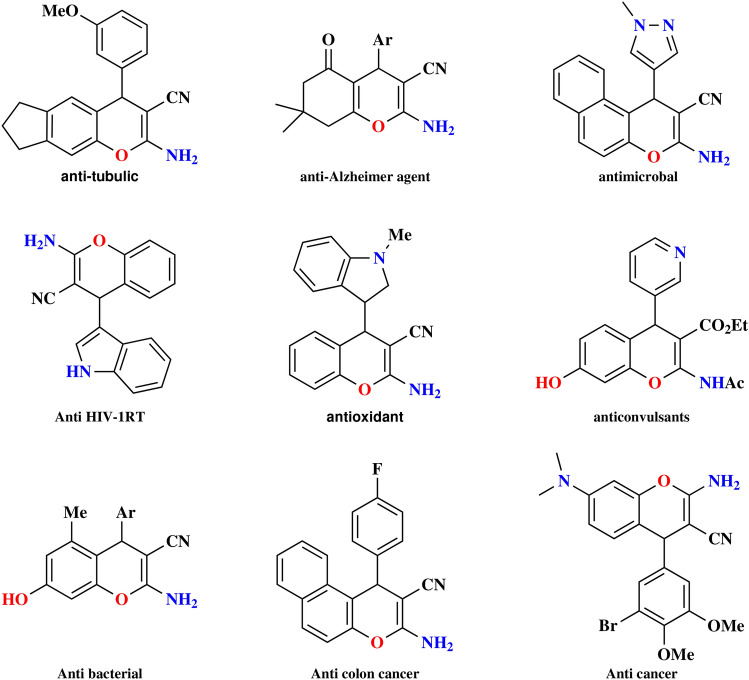

One-pot multi-component reactions are favored in chemistry for their efficiency and practicality compared to traditional multi-step syntheses1. Important reactions like the Ugi, Mannich, Hantsch, and Passerini reactions have contributed to the popularity of multi-component reactions (MCRs)2–5. This approach is widely used in organic chemistry to synthesize important heterocyclic compounds economically in a single step. Researchers focus on these reactions to design products efficiently, especially in the preparation of compounds possessing biological and pharmacological activity6–8. Oxygen-containing heterocyclic molecules like 4H-chromene moieties are essential in pharmaceuticals; the various pharmacological activities of this group of molecules, such as anticancer9, anti-tumor10, antioxidant11, antibacterial12, and antiviral13 properties of 2-amino-4H-chromene compounds have sparked significant interest among chemists and biologists, with Fig. 1 showcasing various biologically active examples. The extraction of these compounds from plants, which serve as natural sources of these valuable molecules, is of significant importance14,15. Therefore, Because of the wide range of applications for 2-amino-4H-chromens, numerous synthetic methods can be found in published literature, a straightforward approach to synthesizing substituted 2-amino-4H-chromenes is by conducting a three-component condensation reaction with reactants including malononitrile, aromatic aldehyde, , and an activated phenol in the presence of an essential catalyst, many catalysts have been used for this preparation, such as - nano powder16, @propyl-Pip17, TEOA18, hydrotalcite (HT)19 and nanocrystalline MgO20. Many existing methods face challenges, for instance, extended reaction times, the use of volatile or hazardous organic solvents, complex work-up procedures, additional energy requirements, and the need for large amounts of catalysts, resulting in difficulties in product separation and the inability to recycle the catalyst. Therefore, there is still a high demand for straightforward, adaptable, and eco-friendly methods to synthesize 2-amino-4H-chromenes under uncomplicated conditions.

Fig. 1.

Some biologically active examples of chromenes.

Nowadays, catalysts are essential in chemical reactions. Scientists are seeking catalysts that reduce pollution and toxicity while also being cost-effective21,22. It has been shown that GO can be used as a heterogeneous metal-free catalyst in organic reactions23. NS-doped-GOQDS is a carbocatalyst that is efficient, inexpensive, non-toxic, stable, and reusable. NS-doped-GOQDS, a carbocatalyst known for its efficiency, affordability, non-toxicity, stability, and reusability, emerges as a fully biocompatible green catalyst for organic synthesis. The development of metal-free catalysts, such as organocatalysts (OC) and carbocatalysts (CC), has significantly impacted catalysis by offering environmentally friendly alternatives. In a continuation of our previous work on synthesizing the NS-doped-GOQDS catalyst and its application in reactions, we introduce a novel method for producing dihydro-4H-chromenes. Our earlier research involved the synthesis of pyrazole and pyridine derivatives synthesized through four- and five-component reactions, respectively, utilizing GOQDs-NS-Doped as a catalyst24. Herein, we present a convenient approach for the efficient synthesis of innovative 2-amino-4H-chromenes using GOQDs-NS-Doped as a catalyst (Fig. 2). Additionally, a computational study was conducted, and the B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) method was employed to calculate the properties of the 4c derivative in its ground state.

Fig. 2.

Catalytic synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromenes using GOQDs-NS-Doped.

Experimental results and discussion

The green and nanocatalyst based on graphene oxide was characterized using various techniques. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded with a Spectrum 400 PerkinElmer FT-IR spectrophotometer. Material characterization was performed using X-ray powder diffraction (XRD, Bruker D8 advance, Cu Ka radiation), scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FE-SEM/STEM SU 9000), UV–Vis spectroscopy (Shimadzu UV-160A), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Rheometric Scientific STA 1500), and Brunauer–Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis (PHSCHINA PHS 1020 Porosity Analyzer). Reagent-grade chemicals were sourced from Merck for the synthesis of the compounds. The starting materials included benzaldehyde (, 99% purity), malononitrile (, 99% purity), resorcinol (, 99% purity), and -naphthol (, 99% purity). Characterization was carried out using FTIR spectroscopy (Spectrum 400 PerkinElmer FT-IR spectrophotometer) and NMR spectroscopy (Bruker Inova instrument, DMSO-d6). NMR spectra were acquired at varying frequencies: H (300 and 500 MHz) and C (75, 100, and 500 MHz).

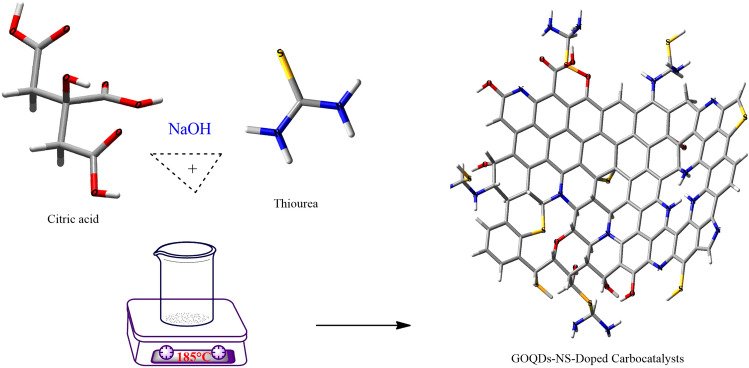

Preparation of (NS-doped-GOQDS)

The synthesis of the NS-doped-GOQDS catalyst, as depicted in Fig. 3, was conducted following the procedure detailed in our earlier publication24. Nitrogen-sulfur-doped graphene oxide quantum dots NS-doped-GOQDS were prepared using a one-pot synthesis method. Citric acid served as the carbon source, and thiourea acted as the nitrogen and sulfur source. The synthesis involved a two-step process. First, graphene oxide (GO) was prepared by pyrolyzing citric acid under controlled conditions, resulting in a black solid. This solid was then purified by washing, crumbling, and dissolving it in a NaOH solution. After neutralization, it was filtered, and dried to obtain pure graphene oxide (GO) powder. To synthesize the NS-doped-GOQDS, 30 mg of citric acid was heated until melted, at which point thiourea was added to the reaction mixture. The mixture was then heated and stirred for 30 minutes, yielding a black viscous product. This product was further purified through cooling, washing, crumbling, and dissolving in a NaOH solution, followed by neutralization, filtration, and drying. This final step yielded the NS-doped-GOQDS powder.

Fig. 3.

Preparation of GOQDs-NS-doped carbocatalysts.

General approach to 2-amino-4H-chromenes synthesis

A mixture containing 1 mmol of aldehydes, 1.1 mmol of various nucleophiles (resorcinol, -naphthol and dimedone), and 1 mmol of malononitrile, along with 30 mg of the catalyst, was placed in a flask and stirred at 40 C in EtOH for the specified time according to Table 1. The progress of the reaction was monitored using Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) with a solvent system of ethyl acetate/n-hexane (1:3). We used a water bath called a Stuart SW15D. It’s like a little heater with a stirrer that helps keep the temperature even. We put a thermometer right in the flask so we could watch the temperature all the time. We adjusted the water bath temperature as needed to keep it at 40 C. After reaction completion, as monitored by TLC, the heterogeneous GOQDs-NS-Doped catalyst was removed by filtration using filter paper. The reaction mixture was then cooled, leading to the formation of product crystals. These crystals were collected by filtration, recrystallized from ethanol, and then filtered again to isolate the purified product.

Table 1.

Optimization of catalyst for 2-amino-4H-chromenes reaction.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Solvent | Catalyst amount (mg) | Temperature (C) | Time (min) | Yield (%) | Ref |

| 1 |

@@ NHCO- adenine sulfonic acid |

Solvent-free | 40 | 110 | 120-170 | 90 | 28 |

| 2 | Tungstic acid-SBA-15 | 30 | 100 | 12 h | 86 | 29 | |

| 3 | MeCN | 0.1 mmol | reflux | 4 h | 83 | 30 | |

| 4 | [Choline][Ac] | [Choline][Ac] | - | rt | 120 | 70 | 31 |

| 5 | GO/-Fe2O3/CuL | Solvent free | 60 | 70 | 60 | 98 | 32 |

| 6 | Pd@GO | EtOH | 10 | 80 | 15 | 92 | 33 |

| 7 | Urea | EtOH/ | 10 mol% | rt | 720 | 73 | 34 |

| 8 | EtOH | 30 | 40 | 120 | 70 | This work | |

| 9 | EtOH | 30 | 40 | 30 | 82 | This work | |

| 10 | EtOH | 30 | 40 | 30 | 78 | This work | |

| 11 | EtOH | 30 | 40 | 45 | 70 | This work | |

| 12 | NS-doped-GOQDS | EtOH | 30 | 40 | 9 | 98 | This work |

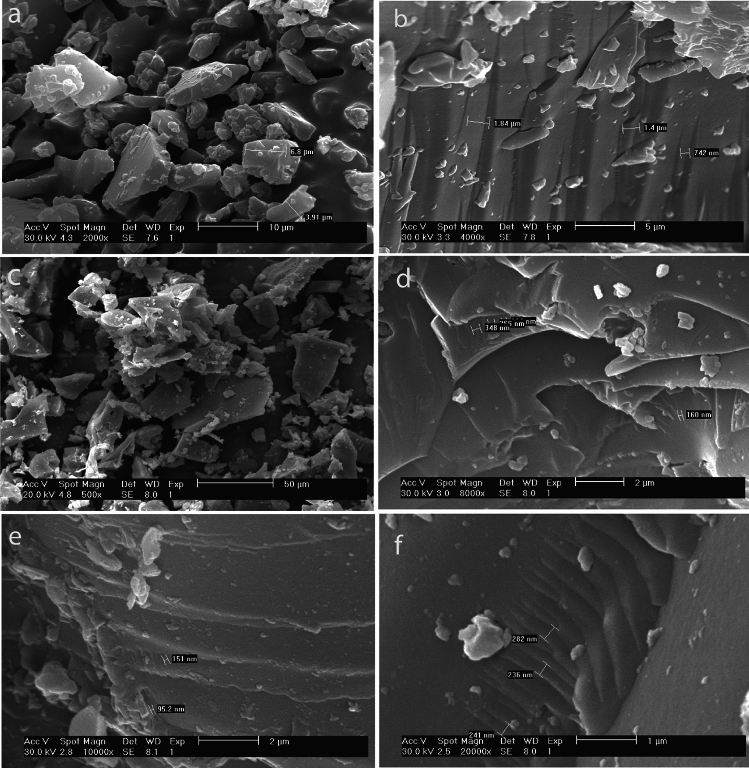

SEM measurement

Figure 4 presents scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of graphene oxide (GO), graphene quantum dots (GOQDs), and GOQDs-NS-doped structures. Figure 4a,b showcase the SEM images of GO, revealing its characteristic morphology. The SEM images of GOQDs-NS-doped structures (Fig. 4c–f) demonstrate distinct features. The material consists of separated sheets with defined edges (Fig. 4c), indicating a layered structure. Notably, the images reveal crumpled areas (Fig. 4c) and layered structures with lamellae (Fig. 4d–f). The thickness of these lamellae ranges from 95 nm to 348 nm. The increased layer thickness in GOQDs-NS-doped structures is attributed to interlayer interactions facilitated by the presence of oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur functional groups on the graphene oxide layers. These heteroatoms are primarily concentrated at the edges of the NS-doped GOQDs, resulting in thicker edges within the sheets.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of GO and GOQDs-NS-doped structures using SEM. Panels (a) and (b) show the characteristic amorphous structure of GO. Panels (c) through (f) illustrate the formation of a layered structure in the GOQDs-NS-doped.25.

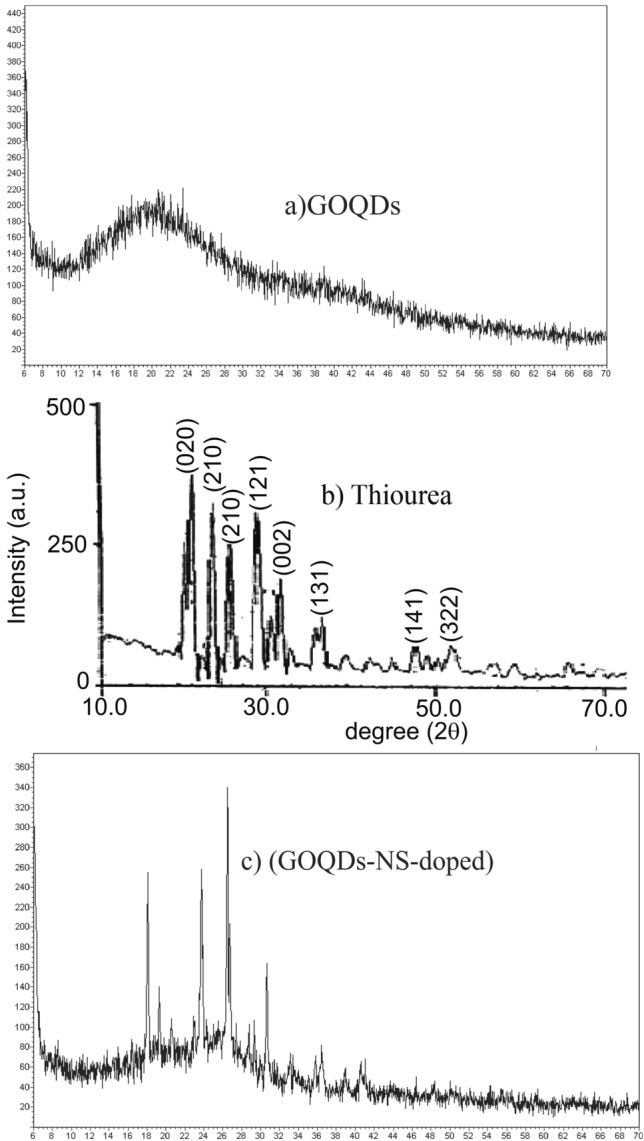

XRD analysis

The presence of thiourea within the GOQDs-NS-doped structure is suggested by XRD analysis. Figure 5a shows the SAXS pattern of GOQDs, exhibiting a broad peak at 2 = 22. The XRD pattern of thiourea is shown in Fig. 5b26, revealing characteristic peaks. Figure 5c demonstrates the XRD pattern of amorphous NS-doped GOQDs, exhibiting a peak at 2 = 26. Comparison of these patterns indicates the presence of thiourea within the NS-doped GOQDs structure.

Fig. 5.

XRD patterns of (a) amorphous GOQDs, (b) thiourea, and (c) NS-doped GOQDs.25.

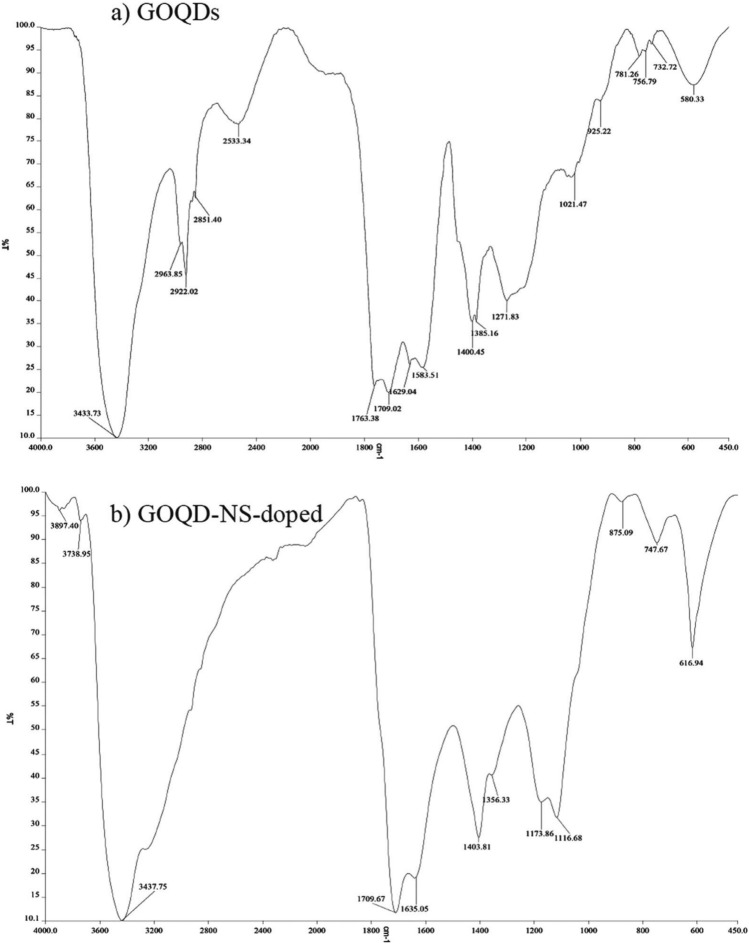

FT-IR analysis

The FTIR spectrum of Graphene Oxide Quantum Dots (GOQDs) exhibits a broad band around 3433 , indicative of hydrogen bonding associated with O-H stretching in water. Additionally, the C=O stretching is evidenced by peaks at 1709 and 1763 , which confirm the existence of carboxyl and carbonyl functional groups. Furthermore, C-O stretching bands characteristic of phenolic, alcohol, or ether groups occur at 1385 and 1021 , while a faint absorption at 1271 points to the presence of epoxy groups (as depicted in Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Spectra showing (a) (GOQDs) and (b) (NS-doped-GOQDs).25.

In the FTIR spectrum of nitrogen-sulfur-doped GOQDs, weak peaks appear at 3738 and 3897 , indicating the presence of free OH and NH groups on the surface. A broad peak in the range of 3200–3500 corresponds to O–H and NH stretching, suggesting that hydroxyl and amine groups are present in the NS-doped GOQDs. The peaks at 2927 and 3072 are attributed to spand sp C–H groups, respectively. Additionally, bands at 1709 , 1635 , and 1403 relate to C=O, C=N, and C–N functional groups. A resonance peak at 875 can be assigned to the bending vibration of OH groups from adsorbed water molecules on the graphene oxide. The peak at 1356 corresponds to the C–OH group, while the peaks at 1116 and 1173 indicate C–O–C and C–N–C stretching vibrations. Lastly, the peak at 747 reflects H–C–H bending (shown in Fig. 6b).

Thermogravimetric studies

Figure 7a,b) illustrate the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves for (GOQDs) and (NS-doped GOQDs). For GOQDs, two significant mass loss events occur at approximately 225 and 435 C, while for NS-doped GOQDs, these correspond to around 290 C and 410 C. The initial mass loss is associated with the oxidation of amorphous carbon, while the subsequent loss relates to the combustion of the carbon bonds in both GOQDs and NS-doped GOQDs. The structure of GOQDs, which contains a higher carbon content and fewer polar groups, leads to reduced interlayer spacing. Consequently, it melts at a lower temperature of 225 C and exhibits layer slipping at the higher temperature of 435 C due to the strong interactions between the graphene oxide layers. The TGA curve of GOQDs demonstrates a notable release of large exothermic heat resulting from carbon combustion. In contrast, NS-doped GOQDs exhibit an increased interlayer distance due to the functional groups’ presence. This results in a melting temperature of 290 C and a lower combustion temperature of 410 C, as the oxidation of carbon occurs more rapidly in the presence of heteroatoms.

Fig. 7.

TGA spectra for (a) GOQDs and (b) NS-doped GOQDs. 3.5 EDX analysis.25.

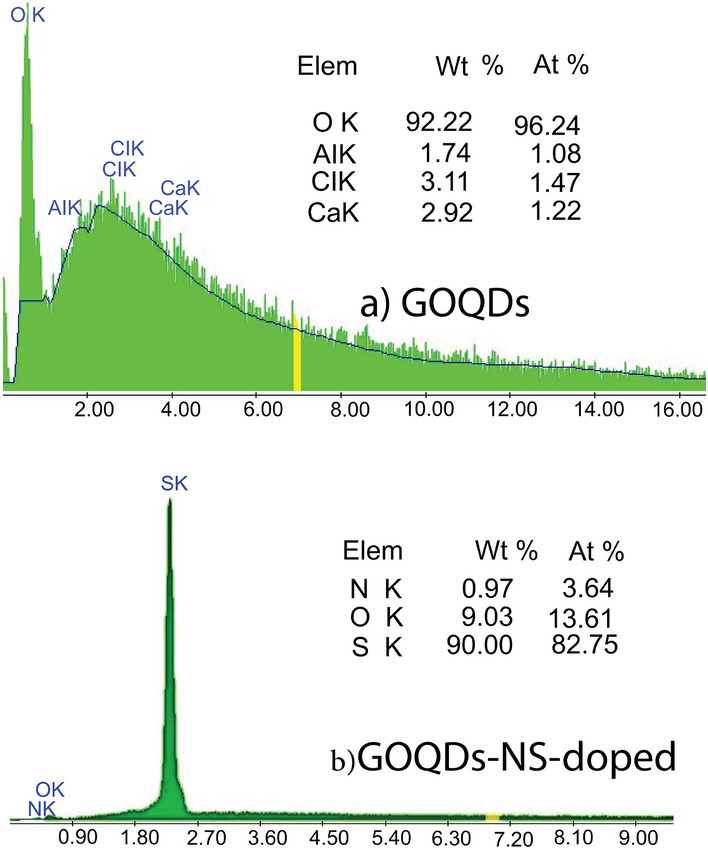

The elemental composition analyzed via EDX is presented in Fig. 8a,b. The analysis reveals the presence of oxygen, sulfur, and nitrogen on the surface of NS-doped GOQDs, with sulfur being particularly prominent in the EDX findings. It is important to note that while this technique can demonstrate the presence of these elements, it does not provide precise quantification of their amounts.

Fig. 8.

EDX spectra showing (a) GOQDs and (b) NS-doped GOQDs.25.

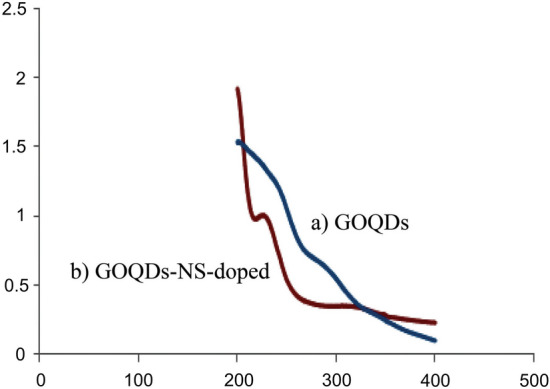

Ultraviolet (UV) measurement

The UV–Vis spectrum presented in Fig. 9 illustrates the characteristics of NS-doped GOQDs, and GOQDs, respectively shown as curves b and a. The GOQDs exhibit distinct absorption peaks around 240 nm and 300 nm, while the NS-doped GOQDs display a notable increase in absorbance at approximately 225 nm and 330 nm. This enhancement indicates the presence of unpaired electrons from nitrogen and sulfur, which are available for interactions.

Fig. 9.

UV-Vis absorption spectra of (a) GOQDs and (b) NS-doped-GOQDs.25.

BET analysis

The analysis performed using BET indicated that NS-doped GOQDs has a specific surface area of 16.482 . In comparison, the specific surface area of raw graphite powder with particle sizes under 20 m was only 7.65 m/g27. This demonstrates an increase of over twofold. Furthermore, the pore size distribution revealed that the enhancement in specific surface area primarily resulted from pores with diameters averaging 14.13 nm.

Reaction condition optimization for 2-amino-4H-chromene synthesis

In the assessment of the catalytic activity of GOQDs-NS-Doped, a one-pot synthesis of a multi-component reaction was chosen, involving malonitrile, aldehyde, active nucleophiles (such as resorcinol, -naphthol, and dimedone), to yield 2-amino 4H-chromenes. 4-Nitro benzaldehyde (1c) and resorcinol (3a) were specifically selected as model compounds for optimizing the reaction. Comparing the yield and time of the reaction catalyzed by GOQDs-NS-Doped with other catalysts) revealed significant improvements (Table 1). GOQDs-NS-Doped, serving as a heterogeneous basic catalyst, notably enhanced the yield under mild conditions. In contrast, catalysts like required reflux conditions for 4 hours to offer the product (Table 1, entry 3). Other catalysts, such as urea, [Choline][Ac], Tungstic acid-SBA-15, and GO/-, suffered from prolonged reaction times(Table 1, entries 1, 2, and 4). Additionally, Pd@GO (Table 1, entry 6) required higher temperatures of 80 C, while GOQDs-NS-Doped exhibited superiority in terms of reaction conditions, time, and yield. , -GO-Pd, -GO-Cu, and -GO- were explored as Lewis acidic and Brønsted acidic catalysts, with varying results. Notably, -GO-Cu and -GO-Pd improved yield and reduced reaction time (Table 1, entries 9 and 10). By incorporating nitrogen and sulfur into graphene oxide, the yield of the reaction was boosted to 98% in just 9 min while also lowering the required temperature to 40 C and demonstrating high reusability. This highlights the advantageous features of GOQDs-NS-Doped detailed in (Table 1, entry 12), making it a promising catalyst for further research and application.

In our investigation (Table 2, entries 1-6), we explored the impact of varying temperatures on the reaction. Starting at room temperature, we achieved a 60% yield after 45 minutes (Table 2, entry 1). Augmenting the temperature to 35 C significantly improved the production yield to 88% (Table 2, entry 2). The optimal outcome was observed at 40 C, where the yield soared to an impressive 98% (Table 2, entry 4). Interestingly, maintaining the temperature at 45 C did not influence the yield (Table 2, entry 5), but a further increase to 50 C saw a slight decrease to 95% yield (Table 2, entry 6). Next, we investigated the effect of catalyst loading from 0 mg to 35 mg (Table 2, entries 7–13). The absence of a catalyst resulted in no product formation even after 60 min (Table 2, entry 7). With catalyst loading increasing from 10 mg to 20 mg, the production yield improved from 40 to 80% (Table 2, entries 8-10). Moreover, the reaction time was reduced from 40 minutes to 15 min with the addition of the catalyst (Table 2, entries 8–11). Notably, at 30 mg of catalyst, the yield peaked at 98% (Table 2, entry 12), beyond which increasing the loading to 35 mg did not impact the yield (Table 2, entry 13). The influence of solvents on the reaction was also assessed (Table 2, entries 14-21). The use of ethanol as a green solvent led to a remarkable increase in yield. However, the addition of water to ethanol reduced the yield from 98 to 74% (Table 2, entry 15). Water used alone in the reaction yielded a lower percentage (Table 2, entry 16). Methanol yielded a 91% product. Aprotic solvents such as tetrahydrofuran, toluene, and dimethylformamide did not enhance the yield as effectively as alcohols (Table 2, entries 18, 19, and 21). Interestingly, conducting the reaction under solvent-free conditions did not significantly impact the yield (Table 2, entry 20).

Table 2.

Optimization of 2-amino-4H-chromenes reaction for 4c derivative.

| Entry | Catalyst | Solvent | (mg) | Temperature (C) | Time (min) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of temperature | ||||||

| 1 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 30 | rt | 45 | 60 |

| 2 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 30 | 30 | 30 | 78 |

| 3 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 30 | 35 | 15 | 88 |

| 4 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 30 | 40 | 30 | 98 |

| 5 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 30 | 45 | 30 | 98 |

| 6 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 30 | 50 | 30 | 95 |

| Effect of catalyst loading | ||||||

| 7 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 0 | 40 | 60 | NR |

| 8 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 10 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| 9 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 15 | 40 | 30 | 60 |

| 10 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 20 | 40 | 30 | 80 |

| 11 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 25 | 40 | 15 | 92 |

| 12 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 30 | 40 | 9 | 98 |

| 13 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 35 | 40 | 9 | 98 |

| Effect of solvent | ||||||

| 14 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | EtOH | 30 | 40 | 9 | 98 |

| 15 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | /EtOH (1:1) | 30 | 40 | 15 | 74 |

| 16 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | 30 | 40 | 80 | 35 | |

| 17 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | MeOH | 30 | 40 | 9 | 91 |

| 18 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | THF | 30 | 40 | 60 | 30 |

| 19 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | Toluene | 30 | 40 | 110 | 23 |

| 20 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | Solvent-free | 30 | 40 | 20 | 55 |

| 21 | GOQDs-NS-Doped | DMF | 30 | 40 | 15 | 70 |

Reaction conditions: 1 mmol of 4-Nitrobenzaldehyde, 1 mmol of malononitrile, 1.1 mmol of resorcinol, and varying weight amounts of NS-Doped-GOQDS catalyst.

Yields refer to isolated products.

Preparation of substituted 2-amino-4H-chromens in the presence of NS-Doped-GOQDS

Following optimization, the reaction’s scope and generality were investigated. Aromatic aldehydes bearing electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents at ortho-, meta-, or para-positions on the aromatic ring were successfully converted into 2-amino-4H-chromen derivatives with excellent yields as shown in Table 3. Notably, a wide range of functional groups, such as 4-nitro, remained stable under the reaction conditions, as evidenced by the successful transformations in the entries 3, 8, and 15 of Table 3. Moreover, aromatic aldehydes with methyl and methoxy groups as electron-donating substituents exhibited excellent performance, affording the desired products in yields of up to 90% as shown in Table 3 (refer to entries 7, 16, and 18). Additionally, halide groups like 4-Cl and 4-Br were efficiently converted into the desired products with high yields. Aromatic aldehydes with a combination of electron-withdrawing and electron-donating substituents showed promising results in the reaction. Notably, substituents with stronger electron-withdrawing characteristics demonstrated increased efficiency and reaction rates, showcasing enhanced electron withdrawal capabilities.

Table 3.

Synthesis and physical data of 2-amino-4H-chromenes 4a-r catalyzed by NS-Doped-GOQDS.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | Nucleophiles | Product | Time (min) | Yield (%) | Mp (C) | |

| Found | Reported | ||||||

| 1 | 1a | Resorcinol 3a | 4a | 15 | 95 | 235–236 | 234–23635 |

| 2 | 3- 1b | Resorcinol 3a | 4b | 12 | 94 | 169–170 | 170–17236 |

| 3 | 4- 1c | Resorcinol 3a | 4c | 9 | 98 | 211–213 | 212–21037 |

| 4 | 4- 1d | Resorcinol 3a | 4d | 12 | 96 | 160–162 | 160–16135 |

| 5 | 2,4- 1e | Resorcinol 3a | 4e | 15 | 92 | 254–256 | 256–25838 |

| 6 | 4- 1f | Resorcinol 3a | 4f | 15 | 91 | 224–226 | 223–22539 |

| 7 | 4- 1g | Resorcinol 3a | 4g | 20 | 90 | 183–186 | 184–18640 |

| 8 | 4- 1h | -Naphthol 3b | 4h | 12 | 97 | 184–186 | 185–18641 |

| 9 | 3- 1i | -Naphthol 3b | 4i | 13 | 90 | 234–236 | 232–23442 |

| 10 | 2- 1j | -Naphthol 3b | 4j | 12 | 92 | 278–280 | 258–26243 |

| 11 | 4- 1k | -Naphthol 3b | 4k | 10 | 96 | 209–211 | 210–21218 |

| 12 | 2,6- 1l | -Naphthol 3b | 4l | 25 | 85 | 206 | 205–20744 |

| 13 | 1m | Dimedone 3c | 4m | 10 | 95 | 222–225 | 224–22645 |

| 14 | 4- 1n | Dimedone 3c | 4n | 12 | 96 | 210–212 | 210–21246 |

| 15 | 4- 1o | Dimedone 3c | 4o | 8 | 97 | 181–183 | 180–18247 |

| 16 | 2- 1p | Dimedone 3c | 4p | 14 | 94 | 203–205 | 203–20748 |

| 17 | 4- 1q | Dimedone 3c | 4q | 13 | 92 | 200–204 | 201–20349 |

| 18 | 2- 1r | Dimedone 3c | 4r | 12 | 90 | 210–213 | 211–21350 |

Reaction condition: Benzaldehyde 1 mmol (151.0 mg), malononitrile 1 mmol (0.66 mg), resorcinol 1.1 mmol (0.121 mg), and 30 mg of NS-Doped-GOQDS catalyst at 40C.

Yields refer to isolated products

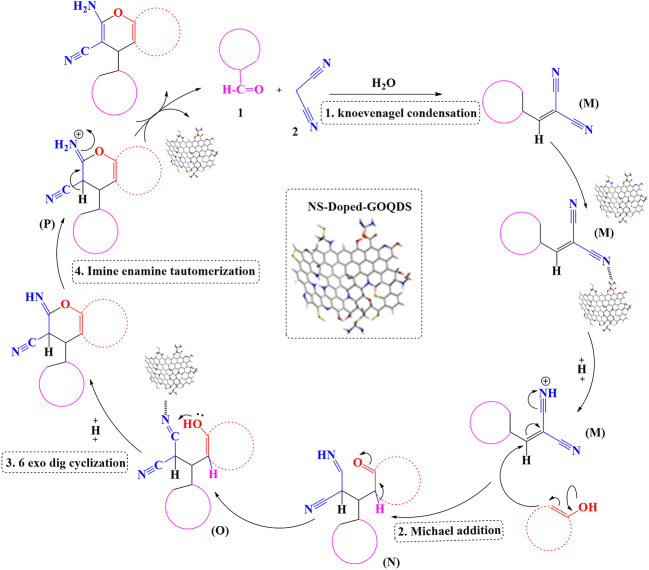

Proposed mechanism of GOQDs-NS-Doped catalyzed 2-amino-4H-chromenes synthesis

The mechanism of preparation of 2-amino-4H-chromenes catalyzed by GOQDs-NS-Doped was demonstrated in Fig. 10. It begins with malononitrile (2), an active methylene compound, undergoing tautomerization in the presence of the catalyst. This allows for a Knoevenagel condensation with an aldehyde derivatives 1 in ethanol, producing arylidene malononitrile M in high yield. The condensation process involves the elimination of water. Subsequently, compound 3 undergoes ortho C-alkylation with M, forming compound N. Compound N then undergoes tautomerization to yield O. The hydroxyl group of O participates in a nucleophilic addition reaction with the cyano (CN) group, leading to an intramolecular cyclization, resulting in the formation of 2-imino-chromene P. Finally, intramolecular proton transfer within P generates the substituted 2-amino-4H-chromene 4. The GOQDs-NS-Doped catalyst plays a crucial role in facilitating the tautomerization of malononitrile, enabling the Knoevenagel condensation. The reaction proceeds through a series of well-defined steps involving nucleophilic addition, cyclization, and proton transfer.

Fig. 10.

The proposed mechanism for the synthesis of 2-amino 4H-chromenes catalyzed by NS-Doped-GOQDS.

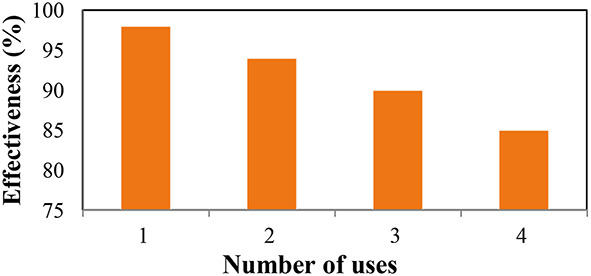

Recycling of the catalyst

The recovery and reusability of each catalyst play a key role in reducing the overall cost of the product. A carefully optimized model reaction was conducted to investigate the catalyst’s reusability. Upon completion of the reaction, the mixture was cooled to room temperature, and the product was separated through filtration using filter paper. The product was washed with ethanol and water multiple times, dried under vacuum, and subsequently reintroduced for further use. Figure 11. demonstrates that the catalyst maintained its activity even after being reused four times in the reaction, indicating minimal loss of effectiveness.

Fig. 11.

Re-usability of GOQDs-NS-Doped catalyst.

Selected spectroscopic data

2-Amino-7-hydroxy-4-phenyl-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile C16H12N2O2 (4a):

yield 98 (%), m.p 235–236 C, H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz): H (ppm) 4.57 (s, 1H), 6.36 (s, 1H), 6.44 (s, 1H), 6.80 (s, 3H), 7.13 (s, 3H), 7.26 (s, 2H), 9.64 (s, 1H); C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz): C (ppm) 37.60, 67.0, 102.8, 112.9, 114.3, 121.1, 127.2, 127.9, 129.1, 130.4, 146.9, 149.5, 160.6, 166.8. ; IR (KBr ): 3698, 3589, 3496, 2192, 1651, 1500, 1150, 850.

2-Amino-7-hydroxy-4-(3-nitrophenyl)-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile C16H11N3O4 (4b):

yield 94 (%) m.p 169–170 C, H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz): H (ppm) 4.94 (s, 1H), 6.48 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.52 (dd, J = 1.8 Hz, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (s, 2H), 7.62 (m, 2H), 8.05 (s, 1H), 8.10 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 9.79 (s, 1H); C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz), C (ppm) 39.85, 66.88, 102.84, 113.05, 113.11, 120.88, 122.25, 122.32, 130.11, 130.46, 134.75, 148.43, 149.03, 149.43, 163.70, 166.12.; IR (KBr, ): 3740, 3505, 3414, 2195, 1656, 1400, 1294, 1150, 847.

2-Amino-7-hydroxy-4-(4-nitrophenyl)-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile C16H11N3O4 (4c):

yield 95 (%), m.p 210–213 C , H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz): H (ppm) 4.88 (s, 1H), 6.47 (s, 1H), 6.51 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (s, 2H), 7.48 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 8.19 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 9.08 (s, 1H); C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz), C (ppm): 38.50, 74.20, 102.90, 112.83, 113.15, 120.74, 124.46, 129.15, 130.40, 146.85, 149.47, 1546.23, 161.12, 165.40.; IR (KBr, ): 3793, 3688, 3596, 2186, 1651, 1512, 1418, 1344, 1162, 1109, 850, 797.

2-Amino-4-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-hydroxy-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile C16H11Cl2N2O2 (4d):

yield 93 (%), m.p 160–162 C, H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): H (ppm) 4.67 (s, 1H), 6.33 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (dd, J = 1.8 Hz, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.77 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (s, 2H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 9.76 (s, 1H), C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz), C (ppm) 38.5 68.37, 102.76, 112.92, 113.63, 120.95, 129.01, 129.70, 130.33, 131.71, 149.34, 162.82, 166.70.; IR (KBr, ): 3701, 3527, 3414, 2189, 1651, 1503, 1462, 1153, 1106, 859, 800.

2-amino-4-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-7-hydroxy-4H-chromene-3- carbonitrile C16H11Cl2N2O2 (4e):

yield 92 (%), m.p 254–256 C.; H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz): H (ppm) 5.15 (s, 1H), 6.43 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.49 (dd, J = 2.1 Hz, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.72 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (s, 2H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (dd, J = 1.8 Hz, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 9.78 (s, 1H).; C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz): C (ppm) 37.39, 68.93, 102.71, 112.32, 113.01, 120.66, 128.54, 129.58, 129.73, 132.63, 132.79, 133.21, 142.32, 149.55, 164.82, 168.91.; IR (KBr, ): 3710, 3547, 3469, 2189, 1506, 1506, 1465, 1156, 1103, 809, 856.

2-Amino-4-(4-bromophenyl)-7-hydroxy-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile C16H11BrN2O2 (4f):

yield 91 (%) ; m.p 224–226 C; H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): H (ppm) 4.62 (s, 1H), 6.37 (s, 1H), 6.46 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.88(s, 2H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 9.70 (s, 1H).; C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): C (ppm) 40.1, 66.70, 102.8, 113.1, 113.7, 120.3, 130.4, 132.0, 146.3, 149.4, 162.7, 166.8.; IR (KBr, ): 3693, 3508, 3417, 2189, 1648, 1503, 1165, 797.

2-Amino-7-hydroxy-4-(p-tolyl)-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile C17H14N2O2 (4g):

yield 90 (%) m.p 183–186 C , H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz): H (ppm) 2.27 (s, 3H), 4.58 (s, 1H), 6.42 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (dd, J = 1.8 Hz, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (m, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.87 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H). 9.68 (s, 1H),C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz): C (ppm) 21.01, 69.90, 102.66, 112.89, 113.98, 121.13, 127.77, 129.23, 129.56, 136.13, 143.93, 149.24, 163.42, 166.60.; IR (KBr, ): 3699, 3577, 3408, 2192, 1648, 1509, 1465, 1159, 1115, 859, 812.

3-Amino-1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-benzo[f]chromene-2-carbonitrile C20H13N3O3 (4h):

yield 97 (%), m.p: 185–186 H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): H (ppm) 8.13–8.11 (d, J=8.45 Hz, 2H,), 7.97–7.95 (d, J=9 Hz, 2H), 7.91(d, J=7.45 Hz, 2H), 7.74–7.72 (m, 2H), 7.66 (d, J=8.25 Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.34 (m, 6H), 7.12 (s, 2H), 5.54 (s, 1H), C NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): C (ppm) 37.71, 66.61, 116.86, 114.43, 122.55, 120.19, 125.94, 123.32, 128.55, 127.36, 145.93, 130.8, 129.22, 134.56, 131.43, 136.67, 145.18, 166.91.; IR (KBr, ): 3548, 3450, 3329, 2189, 1656, 1582, 1517, 1416, 1339, 1228, 821.

3-Amino-1-(3-nitrophenyl)-1H-benzo[f]chromene-2-carbonitrile, C20H13N3O3 (4i):

yield 90 (%), m.p:234–236 IR (KBr): H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): H (ppm) 8.07 (s, 1H), 8.03–8.01 (d, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.98–7.96 (d, J=8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.92–7.91 (d, J=7.6Hz, 1H), 7.87–7.85 (d, J=8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.67–7.66 (d, J=7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.58–7.55 (m, 1H), 7.46–7.37 (m, 3H), 7.15 (s, 2H), 5.62 (s, 1H). C NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): C (ppm) 37.33, 66.99, 114.51, 116.80, 147.99, 120.11, 121.38, 121.87, 123.46, 125.11, 127.30, 128.59, 129.92, 130.41, 130.80, 133.65, 146.91, 147.89, 167.61.; IR (KBr, ): 3542, 3444, 3393, 2867, 2183, 1659,1589, 1527, 1403,1342, 1219, 813.

3-Amino-1-(2-nitrophenyl)-1H-benzo[f]chromene-2-carbonitrile C20H13N3O3 (4j):

yield 92 (%) m.p:278–280 H NMR ( DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): H (ppm) 8.01–7.93 (m, 2H), 7.75–7.73 (d, J= 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.51–7.35 (m, 5H), 7.14 (s, 2H), 7.01 (d, J=7.75, 1H), 6.11 (s, 1H).; C NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): C (ppm): 33.30, 69.17, 113.53, 116.80, 119.64, 122.67, 124.71, 125.17, 127.66, 128.20, 128.72, 130.84, 130.06, 134.22, 139.13, 147.47, 147.55, 166.77.; IR (KBr, ): 3505, 3402, 3187, 2186, 1656, 1598, 1514, 1403, 1342, 1228, 815.

3-Amino-1-(4-chlorophenyl)-1H-benzo[f] chromene-2-carbonitrile, C20H13ClN2O (4k):

yield 96 (%), m.p: 209–211 ; H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): H (ppm) 7.96–7.91 (m, 2H), 7.82 (d, J= 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.48–7.41 (m, 2H), 7.36–7.31 (m, 3H), 7.23–7.21 (m, 2H), 7.03 (s, 2H), 5.37 (s, 1H) C NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): C (ppm) 37.33, 66.9, 114.5, 116.8, 120.1, 121.8, 123.4, 125.1, 127.3, 128.5, 129.9, 130.4, 130.8, 133.6, 146, 147.9, 166.0.; IR (KBr, cm−1): 3533, 3358, 3127, 2934, 2213, 1641, 1585, 1480, 1413, 1363, 1086, 818, 615.

3-Amino-1-(2,6-dichlorophenyl)-1H-benzo[f] chromene-2-carbonitrile C20H12Cl2N2O (4l):

yield 85 (%), m.p: 217–219 H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): H (ppm): 7.95-7.91 (m, 2H), 7.63 (d, J=6.85 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J=8 Hz, 1H), 7.45–7.38 (m, 2H), 7.29–7.22 (m, 3H), 7.08 (s, 2H), 6.15 (s, 1H).; C NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): C (ppm) 37.30, 68.18, 114.60, 117.8, 121.20, 121.78, 123.34, 12660., 127.13, 128.45, 129.89, 131.30, 130.70, 133.23, 146.12, 147.80, 167.02.; IR (KBr, ): 3548, 3418, 3392, 2919, 2186, 1659, 1588, 1514, 1400, 1231, 769.

2-Amino-7,7-dimethyl-5-oxo-4-phenyl-5,6,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile C18H18N2O2 (4m):

yield 95 (%), m.p: 221–223C H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz): H (ppm) 7.31–7.21 (m, 3H), 7.21–7.07 (m, 2H), 6.98 (s, 2H), 4.15 (s, 1H), 2.49 (s, 2H), 2.23 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 2.07 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 1.01 (s, 3H), 0.93 (s, 3H).; C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz): C (ppm) 26.79, 28.39, 31.80, 35.57, 49.96, 68.29, 112.73, 119.72, 126.56, 127.14, 128.32, 144.74, 158.48, 162.49, 195.64.; IR (KBr, ): 3580, 3520, 3332, 2870, 2175, 1410, 1240, 780.

2-Amino-4-(4-chlorophenyl)-7,7-dimethyl-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile C18H17ClN2O2 (4n):

yield 96 (%), m.p: 210–213c H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz): H (ppm) 7.33 (d, J = 8.0 1Hz, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (s, 2H), 4.20 (s, 1H), 2.49 (s, 2H), 2.23 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 2.09 C 13 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 1.01 (s, 3H), 0.93 (s, 3H).; C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz): C (ppm) 195.56, 162.54, 158.48,143.68, 131.09, 129.07, 128.23, 119.48, 112.33, 57.80, 49.92, 35.10, 31.72, 28.27, 26.83.; IR (KBr, ): 3580, 3450, 3323, 2880, 2123, 1520, 1300, 770.

2-Amino-7,7-dimethyl-4-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile C18H17N3O4 (4o):

yield 97 (%), m.p: 180–182C H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz): H (ppm) 8.15 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.43 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (s, 2H), 4.35 (s, 1H), 2.52 (s, 2H), 2.24 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 2.09 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 1.02 (s, 3H), 0.94 (s, 3H).; C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz): C (ppm) 195.65, 163.07, 158.55, 152.22, 146.22, 128.56, 123.60, 119.25, 111.69, 57.00, 49.82, 35.63, 31.75, 28.19, 26.89.; IR (KBr, ): 3487, 3456, 3341, 2878, 2166, 1490, 1356, 787.

2-Amino-4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-7,7-dimethyl-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile C19H20N2O3 (4p):

yield 94 (%), m.p: 203–207C H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz): H (ppm) 7.14 (m, 1H), 7.03–6.89 (m, 3H), 6.79 (s, 2H), 4.48 (s, 1H), 3.73 (s, 3H), 2.48 (d, J = 13.5 Hz, 1H), 2.23 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H), 2.05 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 0.95.; C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz): C (ppm) 195.49, 13 (s, 3H). 163.02, 158.95, 156.79, 132.12, 128.51, 127.75, 120.28, 119.77, 111.86, 111.43, 57.38, 55.56, 50.01, 31.70, 30.30, 28.56, 26.51.; IR (KBr, ): 3470, 3453, 3351, 2872, 2200, 1807, 1532, 764.

2-Amino-4-(4-bromophenyl)-7,7-dimethyl-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile C18H17BrN2O2 (4q):

yield 92 (%), m.p: 201–203C H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz): H (ppm) 7.47 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.03 (s, 2H), 4.17 (s, 1H), 2.49 (s, 2H), 2.23 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 2.09 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 1.02 (s, 3H), 0.93 (s, 3H). C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz): C (ppm) 195.60, 162.57, 158.45, 144.12, 131.15, 129.47, 119.56, 119.48, 112.23, 57.68, 49.91, 35.16, 31.74, 28.26, 26.83. IR (KBr, ): 34770, 3460, 3363, 2830, 2185, 1610, 1476, 783.

2-Amino-7,7-dimethyl-5-oxo-4-(o-tolyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4-H-Chromene-3-carbonitrile C19H20N2O2 (4r):

yield 90 (%), m.p: 211–213C H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz): H (ppm) 7.16–6.97 (m, 3H), 6.94 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (s, 2H), 4.47 (s, 1H), 2.46 (s, 3H), 2.23 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 2.06 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 1.03 (s, 2H), 0.95 (s, 3H).; C NMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz): C (ppm) 195.70, 162.45, 158.26, 143.53, 134.74, 129.86, 127.25, 126.33, 126.15, 119.69, 113.45, 58.28, 49.92, 31.81, 30.92, 28.39, 26.76, 19.03.; IR (KBr, ): 3493, 3420, 2896, 2220, 1598, 1798, 1446, 774.

Computational studies on the derivative 4c

The focus of the study shifted towards utilizing DFT calculations to investigate the physicochemical properties of compound 4c due to promising experimental results. Since the compound 4c has the highest yield among all of our derivatives, DFT studies are presented only for this one. DFT methods are well-known for their reliability, cost-effectiveness, and widespread use in various chemical applications. These methods are beneficial for determining electrophilicity index and spectral data. Among the different DFT methods available, the B3LYP functional51–53 was chosen for its direct approach and improved computational accuracy without a sign of increasing computing time. This method has been proven to reveal important about systems in previous studies. The Gaussian 09 package was used to perform all the geometry optimizations and frequency calculations for the desired product 4c at the B3LYP functional and the 6-311+G(d,p) basis set. We performed computational studies to determine the physicochemical properties of 4c, such as its structure, NMR and FT-IR spectra, NBO charge distribution, thermodynamics, and electrophilicity index.

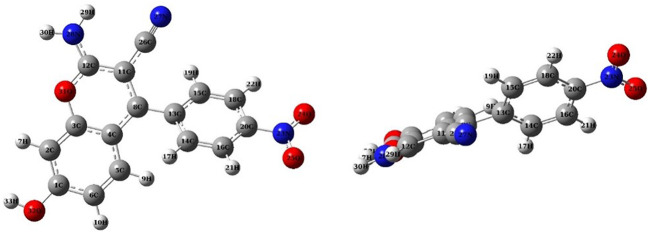

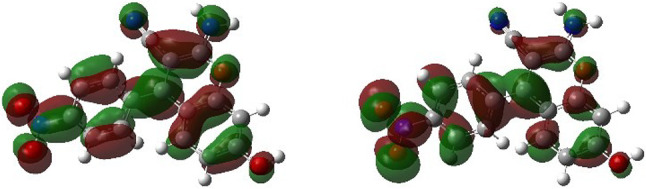

Electronic properties of 4c

The optimized structure and molecular properties of compound 4c have been investigated and characterized in Fig. 12 and Table 4. The dipole moment of 4c is reported to be 21.45 Debye, indicating its significant dipolar characteristics. The obtained electronic data includes the energies of the HOMO and LUMO, and . The HOMO represents the electron-donating capability of the molecule, while the LUMO signifies its ability to accept electrons. These orbitals play crucial roles in the chemical reactivity of the compound.

Fig. 12.

Optimized geometry of 4c: Frontal view/ side view.

Table 4.

The electronic data of 4c.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Energy (Hartree) | − 1081.06 |

| D (Deby) | 21.45 |

| (ev) | − 0.1661 |

| (ev) | − 0.1170 |

| Eg (ev) | 0.0491 |

| Point group | C1 |

| Ionization potential | 0.1170 |

| Electron affinity | 0.1170 |

| Chemical potential () (ev) | 0.1416 |

| Chemical Hardness () (ev) | 0.0246 |

| Electrophilicity () (ev) | 0.4059 |

| Polarizability () | 621.33 |

For 4c, as shown in Fig. 13, Point group C1 indicates a high level of asymmetry in the molecule, and the and values are − 0.1661 eV and − 0.1170 eV, respectively, with a calculated band gap (Eg) between them of 0.0491 eV. As the HOMO energy level increases and approaches the energy level of the LUMO, the molecular ionization potential decreases. Additionally, as the energy level of the LUMO orbital decreases, the electron affinity of the molecule increases. Moreover, the chemical hardness is another calculated parameter that increases with the increase in the energy difference of the HOMO and LUMO orbitals. Additionally, the Global Electrophilicity Index (GEI) is mentioned as a metric that reflects the molecule’s electron-accepting capacity. This index is fundamental in understanding various aspects of the molecule, such as its structure, reactivity, and toxicity. In 1999, Parr and colleagues defined the GEI (u)54 as a parameter used to predict and analyze properties like aromaticity, Lewis acidity55, and dynamics of molecules. This index serves as a valuable tool in studying the reactivity and behavior of chemical compounds. The Global Electrophilicity Index (GEI), chemical potential, and Chemical hardness are calculated by equations (1), (2), and (3), respectively. According to the rules and laws of quantum mechanics, the ionization potential and electron affinity of molecular orbitals have inverse relationships with the energy levels of the frontier molecular orbitals Table 4.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

Fig. 13.

Frontier orbitals (HOMO and LUMO) for 4c calculated at B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory.

Thermodynamic parameters of 4c derivative

Frequency calculations were performed to determine the standard molar energy (E), enthalpy (H), entropy (S), Gibbs free energy (G), and molar heat capacity (Cv) for the 4c derivative. The results are presented in Table 5. According to these results, the negative values of relative energy, Gibbs free energy, and enthalpy for the chromene derivative indicate that 4c is stable in the gas phase.

Table 5.

Quantum molecular descriptors for the molecule 4c.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Relative energy (E) ((kcal/mol) | − 678643.425 |

| Standard enthalpies (H) (kcal/mol) | − 678642.957 |

| Entropies (S) (cal/molK) | 0.285799 |

| Gibbs free energy (G) (kcal/mol) | − 678454.529 |

| molar heat capacity (Cv) (cal/molK) | 0.147157 |

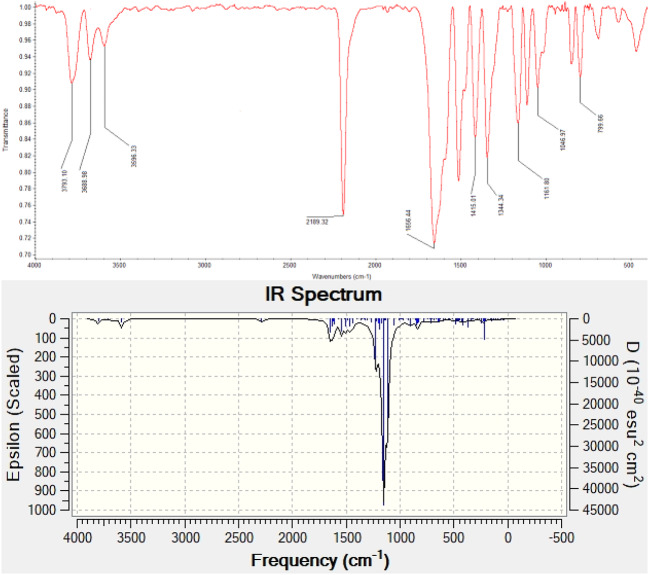

Vibrational analysis of 4c

The structure of the synthesized chromone, 2-amino-7-hydroxy-4-(4-nitrophenyl)-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile (4c), was experimentally confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy. To further support the structural assignment, theoretical vibrational frequencies were calculated using the B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory. A potential energy distribution (PED) analysis56 was then performed using the VEDA 4 program to gain a deeper understanding of the vibrational modes. The PED for each normal mode is follow as below equation:

| 4 |

where represents the force constant, is the normalized amplitude of the corresponding element (i, k), and is the eigenvalue associated with the vibrational frequency of element k. Only PED contributions exceeding 40% for each observed frequency were included in this study. The observed frequencies, along with the assignments of various vibrational modes, calculated frequencies, and PED values, are presented in Table 6. The important peaks of this compound related to , C–N, and OH bonds are as follows: The peak at 2186 indicates the stretching frequency of the C–N bond, while the peaks at 3596 and 3688 represent the symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of the N–H group in Additionally, the peak at 1630 corresponds to the H–N–H bending vibration. The absorption at 3793 corresponds to the stretching bond of the phenolic OH bond. In aromatic compounds, C–H stretching frequencies appear in the range of 3100-3000 . In the compound 4c, the C–H stretching vibrations are predicted at 3193- 3226 for DFT- B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory. Additionally, the paired stretching absorptions of the C=C bonds in the aromatic ring appear at around 1587 and 1487 , and an absorption at 1651 indicates the presence of a vinyl C=C double bond, as clearly seen in Fig. 14. In the computational calculation, the stretching vibrations of the N–H bonds are predicted at 3587 and 3709 , the C–N bond at 2285 , the OH bond at 3802 , and the C=C bonds for aromatic and vinyl at 1547 and 1650 , respectively. The observed and calculated frequencies are in good agreement, and the PED analysis indicates that these modes are pure.

Table 6.

Assignments, experimental, DFT-B3LYP-6311+G(d,p) and PED (%) calculated ir frequencies of compound 4c.

| Assignments | Frequencies () experimental | Theoretical | (%PED) |

|---|---|---|---|

| O–H sym.stretching | 3793 | 3802 | 100% |

| C–N sym.stretching | 2186 | 2285 | 89% |

| N–H sym.stretching | 3596 | 3587 | 48% |

| N–H asym.stretching | 3688 | 3709 | 52% |

| Aromatic C–H asym.stretching | 3197 | 3201 | 92% |

| Aromatic C–H sym.stretching | 3180 | 3192 | 99% |

| H–N–H in-plane-bending(scissoring) | 1630 | 1630 | 45% |

| H–O–C in-plane-bending(rocking) | 1109 | 1187 | 41% |

| H–C–C–C torsion | 850 | 850 | 61% |

| O–C–O–N Out-of-plane bending(wagging) | 680 | 688 | 63% |

| O–N–C in-plane-bending(rocking) | 530 | 537 | 49% |

The largest P.E.D. contributions are reported.

Fig. 14.

Both the experimental (FT-IR) spectrum (shown in the top portion) and the calculated spectrum (shown in the bottom portion) for the compound labeled 4c.

The experimental and computational study of 4c consists of H NMR and C NMR spectra

The successful determination of a molecule’s NMR spectra based on its ground state geometry using the DFT/GIAO method highlights the reliability and precision of quantum chemical calculations in predicting NMR properties. By accurately modeling the molecular structure and its interactions, DFT calculations can offer valuable insights into the chemical shifts observed in NMR spectra. This demonstrates the utility of computational methods in elucidating the relationship between molecular properties and experimental observations in spectroscopy57. The discrepancy between experimental and computed chemical shift values (Table 7) can be influenced by factors such as intermolecular hydrogen bonding and solvent effects. Specifically, the computational recording of OH (H33) and N–H (H29, H30) proton signals at a lower chemical shift compared to the experimental spectra may be attributed to hydrogen bonding interactions involving these functional groups with other molecules within the same compound or with solvent molecules (such as DMSO). This interaction can enhance proton mobility, leading to an increase in the observed chemical shift. In the computational state, H7 is recorded at 6.60 ppm, while in the experimental state, it is observed in the range of 6.47 ppm, appearing as a single signal in both the experimental and computational states. For H10, in the experimental state, it is displayed as a doublet at 6.51 and 6.54 ppm, whereas in the computational state, it appears as a singlet at a chemical shift of 6.90 ppm. On the aromatic ring, H17 and H19 exhibit a doublet with peaks at 7.58 and 7.48 ppm in the experimental state, respectively. In the computational state, these peaks are seen at 7.48 and 7.57 ppm, respectively. H9 appears as a doublet at 6.81 and 6.84 ppm in the experimental state, while in the computational chemical shift, it is observed at 7.82 ppm. For H21 and H22 in the experimental state, a doublet is observed at chemical shifts of 8.19 and 8.21 ppm, respectively. In contrast, in the theoretical state, they are predicted at 8.01 and 8.18 ppm. Overall, these findings suggest a strong experimental and computational data agreement. These key findings from the C-NMR the spectra match the experimental data . The CN carbon is observed at approximately 123.6 ppm in the experimental state and at 124.4 ppm in the computational state. The carbon connected to OH (Ar, C–OH) appears around 161.1 ppm in the experimental state and at 165.4 ppm in the computational state. Additionally, the carbon linked to is detected at 165.4 ppm in the experimental state and at 168.3 ppm in the computational state.

Table 7.

The H-NMR and C-NMR chemical shifts of compound 4c were determined experimentally and calculated utilizing the B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) theoretical approach for purposes of comparison.

| Atom | Theoretical chemical shift/ppm | Experimental chemical shift/ppm | | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H33 | 5.06 | 9.08 | 4.02 |

| H29 | 5.51 | 7.03 | 1.52 |

| H30 | 5.41 | 7.03 | 1.62 |

| H7 | 6.60 | 6.47 | 0.13 |

| H10 | 6.90 | 6.51 | 0.39 |

| H10 | 6.90 | 6.54 | 0.36 |

| H17 | 7.57 | 7.48 | 0.12 |

| H19 | 7.48 | 7.58 | 0.1 |

| H9 | 7.82 | 6.81 | 1.01 |

| H9 | 7.82 | 6.84 | 0.98 |

| H21 | 8.01 | 8.19 | 0.18 |

| H22 | 8.18 | 8.21 | 0.03 |

| C11 (C-CN) | 79.4 | 74.2 | 3.2 |

| C26 (CN) | 123.6 | 124.4 | 0.8 |

| C1 (C-OH) | 165.4 | 161.1 | 4.3 |

| C12 (C-) | 168.3 | 165.4 | 2.9 |

Figure 12 for the atom numbering.

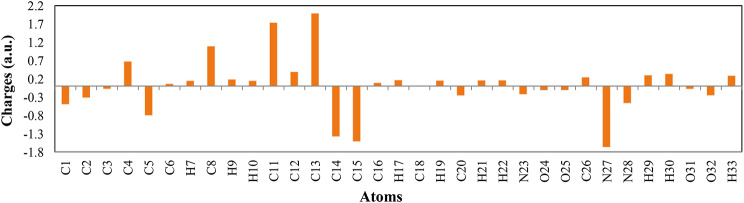

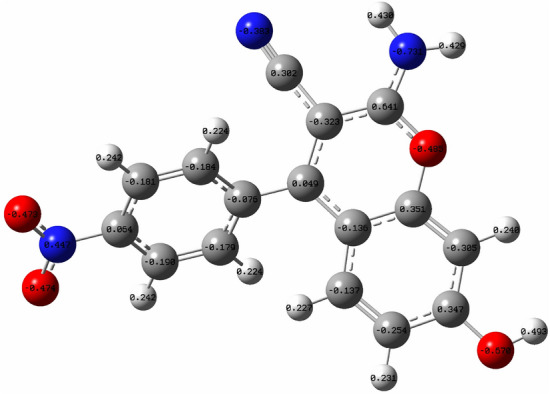

Mulliken charge analysis, (MEP) surface and NBO charge distribution

The Mulliken atomic charges reveal the electronic charge distribution in the molecule, influencing its dipole moment, polarizability, and reactivity. C13, located in the central ring, shows a high positive charge due to its position in an electron-poor region, electron-withdrawing effects from nearby groups, and neighboring pi-bonds potentially delocalizing electrons away from it. As seen in Fig. 15, C13 is para to an group, which is strongly electron-withdrawing and meta-directing for electrophilic aromatic substitution. The group pulls electrons from the ring through inductive and resonance effects, creating electron deficiency particularly at ortho and para positions. This results in C13’s partial positive charge. The molecule’s structure, with multiple electron-withdrawing groups, enhances this effect, making C13 notably electron-deficient according to the Mulliken analysis.

Fig. 15.

The Mulliken atomic charges of 4c.

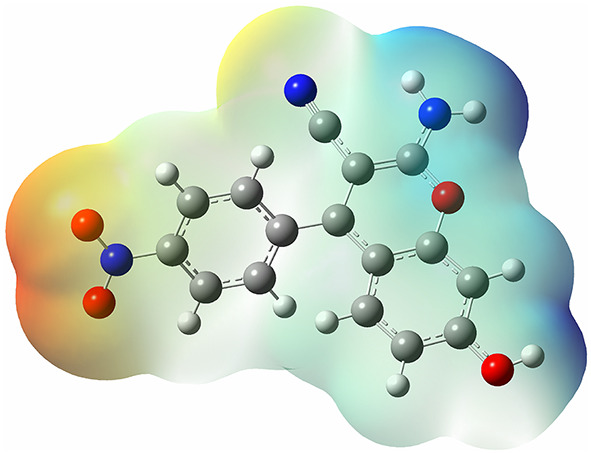

The MEP surface represents the molecular electrostatic potential as a powerful visualization tool commonly utilized to map a molecule’s reactivity towards nucleophilic and electrophilic attacks during chemical reactions. By representing the distribution of electrostatic potential around a molecule, the MEP surface provides valuable insights into the regions of positive and negative charge density, which in turn indicate sites favorable for nucleophilic or electrophilic interactions58,59.

As depicted in Fig. 16, various parts of molecule 4c are color-coded in green, yellow, blue, and light red, indicating a lack of significant electrophilic and nucleophilic characteristics in these areas. The dark blue regions of the molecule correspond to hydrogen atoms attached to nitrogen and oxygen atoms, which are highly electronegative and exhibit the strongest electrophilic properties in the molecule. Conversely, bright red areas around the O24 and O25 atoms display notable nucleophilic behavior.

Fig. 16.

The molecular surfaces of 4c molecule were analyzed for computed Molecular electrostatic potentials, defined according to the electronic density’s 0.0004 electrons/b3 contour. Color representation is as follows: blue indicates regions more positive than 0.010 atomic units (a.u.); green represents values between 0.010 and 0 a.u.; yellow indicates values between 0 and − 0.010 a.u.; and red indicates regions more negative than − 0.010 a.u.

To validate the findings from the Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) calculations, Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) studies were conducted. Atomic charges in molecules play a crucial role in understanding phenomena such as charge transfer and electronegativity equalization during chemical reactions60. NBO atomic charges influence the electronic structure, molecular polarizability and dipole moment. In the NBO calculations displayed in Fig. 17, atoms H29, H30, H33, and H7, identified as blue and electrophilic in the MEP map, exhibit predominantly high positive electric charges. Moreover, oxygen atoms in the molecule, identified as nucleophilic regions based on their electrostatic potential, display negative charges in the NBO analysis. Notably, all nitrogen atoms in the molecule, except N23 in the nitro group, exhibit negative electric charges. The positive charge on the nitrogen atom in (N23) is attributed to the higher electronegativity of the surrounding oxygen atoms compared to nitrogen, resulting in the nitrogen atom carrying a less negative charge in relative to its oxygen counterparts.

Fig. 17.

NBO charge distribution of compound 4c.

The polarity of a bond is directly influenced by the electronegativity of the atoms involved in the bond formation. For instance, in the sigma bond (C12–N28), the calculated polarity values of = 0.6373 (sp) + 0.7706 (sp) reveal that the electron density concentration around atom N28 is higher than that around atom C12 due to the nitrogen’s higher electronegativity relative to carbon. Based bond polarity, another significant result of these calculations is the determination of bond occupancy, representing the number of bonding electrons between the nuclei of the atoms in the bond. It is anticipated that bond occupancy in pi bonds may decrease notably in resonance structures compared to sigma bonds (as observed in entry 1 and 2 of the Table 8). In chemical reactions, as bonds between molecules become more effective and powerful, they tend to be more stable and exhibit more negative energy. Based on the data provided in entry 4 of the table, in molecule C4, the sigma bond (C1–O32) displays the lowest energy level of − 23.16342 atomic units (a.u.), indicating high stability. This bond also exhibits a notable occupancy factor of 0.99731, ranking third after the N23–O24 and N23–O25 bonds in terms of occupancy. Among carbon-carbon bonds, the sigma bond C15–C18 (entry 28) exhibits the highest occupancy factor of 0.98806, while the sigma bond C14–C16 has the lowest bond energy of − 21.31549 in entry 25.

Table 8.

NBO Calculations for determining polarizability coefficients and hybridization of atoms in the molecule 4c.

| Entry | Occupancy (a.u.) |

Bond (A-B) |

Energy (a.u.) |

NBO | S (%) (A) |

S (%) (B) |

P (%) (A) |

P (%) (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.98751 | (C1–C2) | − 0.74149 | 0.7064(sp)+0.7078(sp) | 37.51 | 35.00 | 62.45 | 64.95 |

| 2 | 0.82876 | (C1–C2) | − 0.28633 | 0.6961(sp)+0.7179(sp) | – | – | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 0.98722 | (C1–C6) | -1.48836 | 0.7128(sp)+0.7014(sp) | 37.11 | 33.74 | 62.76 | 66.21 |

| 4 | 0.99731 | (C1–O32) | 23.18934 | 0.5769(sp)+0.8168(sp) | 25.11 | 35.02 | 74.67 | 64.90 |

| 5 | 0.98560 | (C2–C3) | − 1.42291 | 0.7013(sp)+0.7128(sp) | 34.99 | 38.56 | 64.96 | 61.41 |

| 6 | 0.98694 | (C2–H7) | − 0.53786 | 0.7866(sp)+0.6174(sp) | 30.01 | 99.95 | 69.96 | 0.05 |

| 7 | 0.98568 | (C3–C4) | − 0.88036 | 0.7059(sp)+0.7083(sp) | 38.89 | 31.44 | 61.07 | 68.51 |

| 8 | 0.81620 | (C3–C4) | − 5.25953 | 0.7165(sp)+0.6976(sp) | – | 0.01 | 99.97 | 99.94 |

| 9 | 0.99419 | (C3–O31) | − 1.10011 | 0.5524(sp)+0.8336(sp) | 22.28 | 33.43 | 77.47 | 66.52 |

| 10 | 0.98208 | (C4–C5) | − 0.70536 | 0.7217(sp)+0.6922(sp) | 34.56 | 34.55 | 65.41 | 65.41 |

| 11 | 0.98237 | (C4–C8) | − 0.77381 | 0.7084(sp)+0.7058(sp) | 33.91 | 32.99 | 66.06 | 66.97 |

| 12 | 0.98684 | (C5–C6) | − 1.28362 | 0.7059(sp)+0.7083(sp) | 36.39 | 36.76 | 63.57 | 63.20 |

| 13 | 0.86360 | (C5–C6) | − 0.36178 | 0.7113(sp)+0.7029(sp) | – | – | 99.95 | 99.94 |

| 14 | 0.98799 | (C5–H9) | − 0.53452 | 0.7847(sp)+0.6199(s) | 28.98 | 99.95 | 70.97 | 0.05 |

| 15 | 0.98854 | (C6–H10) | − 0.53368 | 0.7844(sp)+0.6203(s) | 29.58 | 99.95 | 70.38 | 0.05 |

| 16 | 0.97878 | (C8–C11) | − 0.70328 | 0.6969(sp)+0.7172(sp) | 31.44 | 36.29 | 68.52 | 63.69 |

| 17 | 0.82418 | (C8C11) | − 0.28941 | 0.7123(sp)+0.7019(sp) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 99.95 | 99.99 |

| 18 | 0.98561 | (C8–C13) | − 0.74520 | 0.7109(sp)+0.7032(sp) | 35.50 | 32.96 | 64.47 | 67.01 |

| 19 | 0.98324 | (C11–C12) | − 0.76434 | 0.7112(sp)+0.7030(sp) | 32.42 | 42.02 | 67.53 | 57.95 |

| 20 | 0.98766 | (C11–C26) | − 0.75798 | 0.7172(sp)+0.6968(sp) | 31.24 | 53.14 | 68.71 | 46.83 |

| 21 | 0.99430 | (C12–N28) | − 0.94235 | 0.6373(sp)+0.7706(sp) | 32.32 | 38.94 | 67.60 | 61.00 |

| 22 | 0.99433 | (C12–O31) | − 1.01954 | 0.5662(sp)+0.8243(sp) | 25.33 | 33.03 | 74.44 | 66.90 |

| 23 | 0.98537 | (C13–C14) | − 0.69849 | 0.7168(sp)+0.6972(sp) | 33.61 | 35.10 | 66.36 | 64.85 |

| 24 | 0.98576 | (C13–C15) | − 0.69912 | 0.7152(sp)+0.6989(sp) | 33.40 | 34.99 | 66.56 | 64.97 |

| 25 | 0.98736 | (C14–C16) | − 0.97206 | 0.7040(sp)+0.7102(sp) | 35.96 | 36.92 | 63.99 | 63.04 |

| 26 | 0.88554 | (C14–C16) | − 21.31549 | 0.7247(sp)+0.6891(sp) | 0.05 | 0.01 | 99.90 | 99.91 |

| 27 | 0.98896 | (C14–H17) | − 1.41904 | 0.7834(sp)+0.6215(s) | 28.76 | 99.96 | 71.19 | 0.04 |

| 28 | 0.98806 | (C15–C18) | − 0.72875 | 0.7061(sp)+0.7081(sp) | 36.17 | 36.77 | 63.79 | 63.19 |

| 29 | 0.88265 | (C15–C18) | − 0.34385 | 0.7254(sp)+0.6883(sp) | 0.06 | 0.02 | 99.88 | 99.91 |

| 30 | 0.98849 | (C15–H19) | − 3.43203 | 0.7833(sp)+0.6217(s) | 28.76 | 99.96 | 71.19 | 0.04 |

| 31 | 0.98687 | (C16–C20) | − 0.74667 | 0.6980(sp)+0.7161(sp) | 33.75 | 37.43 | 66.21 | 62.53 |

| 32 | 0.98782 | (C16–H21) | − 0.53373 | 0.7880(sp)+0.6156(s) | 29.38 | 99.95 | 70.58 | 0.05 |

| 33 | 0.98684 | (C18–C20) | − 0.86970 | 0.6974(sp)+0.7162(sp) | 33.79 | 37.44 | 66.16 | 62.53 |

| 34 | 0.98780 | (C18–H22) | − 4.12443 | 0.7880(sp)+0.6157(s) | 29.42 | 99.95 | 70.54 | 0.05 |

| 35 | 0.99482 | (C20–N23) | − 0.85720 | 0.6093(sp)+0.7929(sp) | 25.02 | 38.08 | 74.86 | 61.88 |

| 36 | 0.99782 | (N23–O24) | − 1.05763 | 0.7018(sp)+0.7124(sp) | 30.85 | 23.75 | 69.02 | 76.11 |

| 37 | 0.83854 | (N23–O24) | − 0.44006 | 0.6641(sp)+0.7477(sp) | – | – | 99.94 | 99.98 |

| 38 | 0.99783 | (N23–O25) | − 1.06307 | 0.7018(sp)+0.7124(sp) | 30.84 | 23.75 | 69.02 | 76.11 |

| 39 | 0.99665 | (C26–N27) | − 1.07240 | 0.6527(sp)+0.7578(sp) | 46.96 | 47.06 | 53.02 | 52.57 |

| 40 | 0.99087 | (C26–N27) | − 0.36768 | 0.6770(sp)+0.7359(sp) | 0.18 | 0.04 | 99.76 | 99.65 |

| 41 | 0.98751 | (C26–N27) | − 0.36532 | 0.6516(sp)+0.7587(sp) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 99.89 | 99.68 |

| 42 | 0.99231 | (N28–H29) | − 0.70789 | 0.8459(sp)+0.5333(s) | 30.71 | 99.93 | 69.25 | 0.07 |

| 43 | 0.99346 | (N28–H30) | − 0.71818 | 0.8463(sp)+0.5327(s) | 30.22 | 99.94 | 69.74 | 0.06 |

| 44 | 0.99355 | (O32–H33) | − 0.46545 | 0.8656(sp)+0.5007(s) | 21.43 | 99.87 | 78.48 | 0.13 |

Furthermore, the NBO calculations provide insights into the contributions of s and p orbitals from atoms participating in bond formation. For example, in the sigma bond (C15–H19), atom C15 contributes 28.76 and 71.19 in s and p orbitals, respectively, while H19 contributes 99.96 in s orbitals with negligible contribution (0.04) in p orbitals, as indicated in entry 30. Notably, there is no p orbital contribution from atom H19 in its bond with C15.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have devised a novel and effective synthetic approach for producing 2-amino-4H-chromene and its derivatives by reacting aldehydes, malononitrile, and various nucleophiles, such as resorcinol, -naphthol and dimedone, with a GOQDs-NS-Doped Catalyst. The GOQDs-NS-Doped, a nano-material known for its high surface area and reusability, exhibited exceptional catalytic efficiency, resulting in high yields of the 2-amino-4H-chromene compounds in a short time frame using ethanol as the solvent. the catalyst could be utilized again for up to four cycles without a significant loss in its catalytic activity. This approach presents clear advantages over traditional methods for synthesizing these compounds. In addition, the theoretical calculations supported the experimental results. The synthesized 4c derivative underwent detailed analysis using the DFT method. Extensive structural studies, including electronic characterizations also the HOMO and LUMO energies were determined and NMR and IR data analysis for the synthesized compound 4c were conducted, all at the B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory.”

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Urmia University and K. N. Toosi University of Technology.

Author contributions

P.B. designed and conducted the experimental work, synthesized 2-amino-4H-chromene derivatives from resorcinol. P.B. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and contributed to all subsequent revisions. Sh.R. provided overall project supervision and access to lab facilities. A.P.M. oversaw the manuscript writing and editing process, ensuring clarity and conciseness. A.B. provided the computational data and analysis, reviewed and edited the computational section of the manuscript. A.G. synthesized 2-amino-4H-chromene derivatives from -naphthol, and provided the spectral data. Z.A. synthesized 2-amino-4H-chromene derivatives from dimedone, and provided the spectral data. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nandi, S. et al. One-pot multicomponent reaction: A highly versatile strategy for the construction of valuable nitrogen-containing heterocycles. ChemistrySelect7, e202201901 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ugi, I., Fetzer, U., Eholzer, U., Knupfer, H. & Offermann, K. Isonitrile syntheses. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.4, 472–484 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Passerini, M. & Simone, L. Sopra gli sonitriles (I). Compound of p-isonitrileazobenzene with acetone and acetic acid. Gazz. Chim. Ital.51, 126–129 (1921).

- 4.Mannich, C. & Krösche, W. Ueber ein kondensationsprodukt aus formaldehyd, ammoniak und antipyrin. Arch. Pharm.250, 647–667 (1912). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hantzsch, A. Ueber die synthese pyridinartiger verbindungen aus acetessigäther und aldehydammoniak. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem.215, 1–82 (1882). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arora, P., Arora, V., Lamba, H. & Wadhwa, D. Importance of heterocyclic chemistry: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res.3, 2947 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ou, J. et al. Heterocyclic-modified imidazoquinoline derivatives: Selective TLR7 agonist regulates tumor microenvironment against melanoma. J. Med. Chem.67, 3321–3338 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh, A., Debnath, R., Chawla, V. & Chawla, P. A. Heterocyclic compounds as xanthine oxidase inhibitors for the management of hyperuricemia: synthetic strategies, structure–activity relationship and molecular docking studies (2018–2024). RSC Med. Chem. (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Oliveira-Pinto, S. et al. Unravelling the anticancer potential of functionalized chromeno[2,3-b]pyridines for breast cancer treatment. Bioorg. Chem.100, 103942 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okasha, R. M. et al. Design of new benzo[h]chromene derivatives: Antitumor activities and structure-activity relationships of the 2,3-positions and fused rings at the 2,3-positions. Molecules22, 479 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson, T. A. et al. Synthesis, antioxidant, dna interaction, electrochemical, and spectroscopic properties of chromene-based schiff bases: Experimental and theoretical approach. J. Mol. Struct.1307, 138020 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agrawal, N., Goswami, R. & Pathak, S. Synthetic methods for various chromeno-fused heterocycles and their potential as antimicrobial agents. Med. Chem.20, 115–129 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nongthombam, G. S., Barman, D. & Iyer, P. K. Through-space charge-transfer-based aggregation-induced emission and thermally activated delayed fluorescence in fused 2H-chromene coumarin congener generating ROS for antiviral (SARS-CoV-2) approach. ACS Appl. Bio Mater.7, 1899–1909 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pratap, R. & Ram, V. J. Natural and synthetic chromenes, fused chromenes, and versatility of dihydrobenzo[h]chromenes in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev.114, 10476–10526 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benny, A. T. et al. Chromone, a privileged scaffold in drug discovery: Developments in the synthesis and bioactivity. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem.22, 1030–1063 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghashang, M. ZnAl2O4-Bi2O3 composite nano-powder as an efficient catalyst for the multi-component, one-pot, aqueous media preparation of novel 4H-chromene-3-carbonitriles. Res. Chem. Intermed.42, 4191–4205 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pourhasan, B. & Mohammadi-Nejad, A. Piperazine-functionalized nickel ferrite nanoparticles as efficient and reusable catalysts for the solvent-free synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromenes. J. Chin. Chem. Soc.66, 1356–1362 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel, A. S., Tala, S. D., Nariya, P. B., Ladva, K. D. & Kapuriya, N. P. Triethanolamine-catalyzed expeditious and greener synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromenes. J. Chin. Chem. Soc.66, 247–252 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kale, S. R., Kahandal, S. S., Burange, A. S., Gawande, M. B. & Jayaram, R. V. A benign synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromene in aqueous medium using hydrotalcite (HT) as a heterogeneous base catalyst. Catal. Sci. Technol.3, 2050–2056 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Safari, J., Zarnegar, Z. & Heydarian, M. Practical, ecofriendly, and highly efficient synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromenes using nanocrystalline mgo as a reusable heterogeneous catalyst in aqueous media. J. Taibah Univ. Sci.7, 17–25 (2013). [Google Scholar]

-

21.Payamifar, S., Abdouss, M. & Poursattar Marjani, A. The recent development of

-cyclodextrin-based catalysts system in suzuki coupling reactions. Appl. Organomet. Chem.38, e7458 (2024). [Google Scholar]

-cyclodextrin-based catalysts system in suzuki coupling reactions. Appl. Organomet. Chem.38, e7458 (2024). [Google Scholar] -

22.Payamifar, S. & Poursattar Marjani, A. A new

-cyclodextrin-based nickel as green and water-soluble supramolecular catalysts for aqueous suzuki reaction. Sci. Rep.13, 21279 (2023).

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-cyclodextrin-based nickel as green and water-soluble supramolecular catalysts for aqueous suzuki reaction. Sci. Rep.13, 21279 (2023).

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - 23.Sengupta, D., Ghosh, S. & Basu, B. Advances and prospects of graphene oxide (go) as heterogeneous’ carbocatalyst. Curr. Org. Chem.21, 834–854 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rostamizadeh, S., Zamiri, B., Mahkam, M. & Azar Aghbelagh, P. B. Goqds and goqds-ns-doped carbocatalysts: A concise study on production and use in one-pot green mcrs. Curr. Org. Synth.20, 788–811 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Reprinted from Current Organic Synthesis, Vol 20, Rostamizadeh, S., Zamiri, B., Mahkam, M. & Azar Aghbelagh, P. B., Goqds and goqds-ns-doped carbocatalysts: A concise study on production and use in one-pot green mcrs., 788–811, Copyright (2023), with permission from Bentham Science Publishers. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Madhurambal, G. & Mariappan, M. Growth and characterization of urea-thiourea non-linear optical organic mixed crystal. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys.48, 264–270 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fouda, A. N., El Shazly, M. D. & Almaqwashi, A. A. Facile and scalable green synthesis of n-doped graphene/cnts nanocomposites via ball milling. Ain Shams Eng. J.12, 1017–1024 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadri, Z., Behbahani, F. K. & Keshmirizadeh, E. One-pot multicomponent synthesis of 2,6-diamino-4-arylpyridine-3,5-dicarbonitriles using prepared nanomagnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@(CH2)3NHCO-adenine sulfonic acid. Inorg. Nano-Met. Chem. 1–10 (2022).

- 29.Kundu, S. K., Mondal, J. & Bhaumik, A. Tungstic acid functionalized mesoporous SBA-15: A novel heterogeneous catalyst for facile one-pot synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromenes in aqueous medium. Dalton Trans.42, 10515–10524 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eshghi, H., Damavandi, S. & Zohuri, G. Efficient one-pot synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromenes catalyzed by ferric hydrogen sulfate and Zr-based catalysts of FI. Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Nano-Met. Chem.41, 1067–1073 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu, A., Li, Q., Feng, W., Fan, D. & Li, L. Biocompatible ionic liquid promote one-pot synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromenes under ambient conditions. Catal. Lett.151, 720–733 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcano, D. C. et al. Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano4, 4806–4814 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akocak, S. et al. One-pot three-component synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromene derivatives by using monodisperse Pd nanomaterials anchored graphene oxide as highly efficient and recyclable catalyst. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects11, 25–31 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brahmachari, G. & Banerjee, B. Facile and one-pot access to diverse and densely functionalized 2-amino-3-cyano-4H-pyrans and pyran-annulated heterocyclic scaffolds via an eco-friendly multicomponent reaction at room temperature using urea as a novel organo-catalyst. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng.2, 411–422 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chehab, S. et al. Catalytic performance of cadmium pyrophosphate in the knoevenagel condensation and one-pot multi-component reaction of chromene derivatives. J. Chem. Sci.135, 95 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tahmassebi, D., Blevins, J. E. & Gerardot, S. S. Zn (L-proline)2 as an efficient and reusable catalyst for the multi-component synthesis of pyran-annulated heterocyclic compounds. Appl. Organomet. Chem.33, e4807 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heydari, R., Mansouri, A., Shahrekipour, F. & Shahraki, R. Imidazole/cyanuric acid as an efficient catalyst for the synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromenes in aqueous media at ambient temperature. Lett. Org. Chem.15, 302–306 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fareghi-Alamdari, R., Zekri, N. & Mansouri, F. Enhancement of catalytic activity in the synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromene derivatives using both copper-and cobalt-incorporated magnetic ferrite nanoparticles. Res. Chem. Intermed.43, 6537–6551 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohamadpour, F. Ethylene glycol as a reusable and biodegradable solvent for the synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromenes. Org. Prep. Proced. Int.56, 169–174 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaikh, M. A., Farooqui, M. & Abed, S. Novel task-specific ionic liquid [Et2NH(CH2)2CO2H][AcO] as a robust catalyst for the efficient synthesis of some pyran-annulated scaffolds under solvent-free conditions. Res. Chem. Intermed.45, 1595–1617 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heravi, M. M., Baghernejad, B. & Oskooie, H. A. A novel and efficient catalyst to one-pot synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromenes by methanesulfonic acid. J. Chin. Chem. Soc.55, 659–662 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kafi-Ahmadi, L., Poursattar Marjani, A. & Nozad, E. Ultrasonic-assisted preparation of Co3O4 and Eu-doped Co3O4 nanocatalysts and their application for solvent-free synthesis of 2-amino-4H-benzochromenes under microwave irradiation. Appl. Organomet. Chem.35, e6271 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patra, A. & Mahapatra, T. Aliquat 336 catalysed three-component condensation in an aqueous media: A synthesis of 1H-and 4H-benzochromenes. J. Chem. Res.2008, 405–408 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Azizi Amiri, M. et al. Copper-amine complex immobilized on nano nay zeolite as a recyclable nanocatalyst for the environmentally friendly synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromenes. Appl. Organomet. Chem.36, e6886 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohamadpour, F. et al. 9-mesityl-10-methylacridinium perchlorate (Mes-Acr-Me+ClO4-) as a novel metal-free donor-acceptor (d–a) photocatalyst: visible-light-induced access to tetrahydrobenzo[b]pyran scaffolds through a single-electron transfer (set) pathway. Res. Chem. Intermediat. 1–15 (2024).

- 46.Shaikh, S. A. et al. Bimetallic CoCeO2 oxide nanoparticles: An efficient and reusable heterogeneous catalyst for the preparation of 2-amino-3-cyano-4H-pyran derivatives. J. Heterocycl. Chem.60, 1004–1013 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Momenpour Surchani, M. et al. A green, facile, and efficient synthesis of 4H-benzo[b]pyrans using 2,2’-bipyridine as a recyclable organocatalyst. In Organic Preparations and Procedures International 1–7 (2023).

- 48.Maleki, A., Ghalavand, R. & Haji, R. F. Synthesis and characterization of the novel diamine-functionalized Fe3O4@SiO2 nanocatalyst and its application for one-pot three-component synthesis of chromenes. Appl. Organomet. Chem.32, e3916 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamoradi, T. et al. Synthesis of Eu(III) fabricated spinel ferrite based surface modified hybrid nanocomposite: Study of catalytic activity towards the facile synthesis of tetrahydrobenzo[b]pyrans. J. Mol. Struct.1219, 128598 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mohamadpour, F. Synthesis of tetrahydrobenzo[b]pyrans promoted by sodium stearate as a lewis base-surfactant combined catalyst in an aqueous micellar medium. Org. Prep. Proced. Int.55, 345–350 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu, X. & Goddard, W. A. I. The X3LYP extended density functional for accurate descriptions of nonbond interactions, spin states, and thermochemical properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.101, 2673–2677 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. Density functionals with broad applicability in chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res.41, 157–167 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ataei, S., Nemati-Kande, E. & Bahrami, A. Quantum dft studies on the drug delivery of favipiravir using pristine and functionalized chitosan nanoparticles. Sci. Rep.13, 21984 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parr, R. G., Szentpály, L. V. & Liu, S. Electrophilicity index. J. Am. Chem. Soc.121, 1922–1924 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jupp, A. R., Johnstone, T. C. & Stephan, D. W. The global electrophilicity index as a metric for lewis acidity. Dalton Trans.47, 7029–7035 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jamróz, M. H. Vibrational energy distribution analysis (veda): scopes and limitations. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.114, 220–230 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolff, S. K. & Ziegler, T. Calculation of dft-giao nmr shifts with the inclusion of spin-orbit coupling. J. Chem. Phys.109, 895–905 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lakshminarayanan, S. et al. Molecular electrostatic potential (mep) surface analysis of chemo sensors: An extra supporting hand for strength, selectivity & non-traditional interactions. J. Photochem. Photobiol.6, 100022 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharma, D. & Tiwari, S. N. Comparative computational analysis of electronic structure, mep surface and vibrational assignments of a nematic liquid crystal: 4-n-methyl-4-cyanobiphenyl. J. Mol. Liq.214, 128–135 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Govindarajan, M. & Karabacak, M. Spectroscopic properties, nlo, homo-lumo and nbo analysis of 2,5-lutidine. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.96, 421–435 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.