Abstract

The unknown boundary issue, between superior computational capability of deep neural networks (DNNs) and human cognitive ability, has becoming crucial and foundational theoretical problem in AI evolution. Undoubtedly, DNN-empowered AI capability is increasingly surpassing human intelligence in handling general intelligent tasks. However, the absence of DNN’s interpretability and recurrent erratic behavior remain incontrovertible facts. Inspired by perceptual characteristics of human vision on optical illusions, we propose a novel working capability analysis framework for DNNs through innovative cognitive response characteristics on visual illusion images, accompanied with fine adjustable sample image construction strategy. Our findings indicate that, although DNNs can infinitely approximate human-provided empirical standards in pattern classification, object detection and semantic segmentation, they are still unable to truly realize independent pattern memorization. All super cognitive abilities of DNNs purely come from their powerful sample classification performance on similar known scenes. Above discovery establishes a new foundation for advancing artificial general intelligence.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-80647-0.

Subject terms: Network models, Object vision, Perception

Introduction

The artificial intelligence (AI) capability exhibited by Deep neural networks (DNNs) is progressively surpassing the cognitive abilities of human brain, demonstrating remarkable performance in handling a diverse array of intricate and intellectually demanding tasks across various domains1–5. This achievement highlights the immense potential of machine learning and cognitive computing, ushering in significant transformations and possibilities across all areas of society6–9. However, with the continuous demonstration of remarkable intelligence by DNNs10–12, we are compelled to confront a fundamental theoretical question: Is there a unknown boundary between the capabilities of DNNs and the human brain? This issue involves multiple dimensions including technology, philosophy, and ethics13,14. Although interpretable technologies are emerging across various domains, including feature importance-based methods such as LIME and SHAP, and visualization-based techniques like Grad-CAM and t-SNE, deep neural network (DNN) models still face significant challenges in achieving transparency, reliability, and high generalization capabilities15,16. Existing interpretability frameworks primarily focus on local explanation and feature-level interpretability, concentrating on revealing the decision-making mechanism, feature importance and activation patterns of models17. However, these methods have not yet delved into the overall perceptual and cognitive capabilities of DNN models from the perspective of human visual perception, particularly when confronted with complex visual phenomena18. Especially when confronted with extensive and intricate data, even the cutting-edge DNN models utilizing learning techniques for deep feature patterns19–21, are unable to achieve unlimited perceptual capabilities22. Meanwhile, in recent years, visual illusions have been widely used to investigate the neural mechanisms of human visual perception23, providing a unique perspective on how the brain processes and interprets visual information. Even so, visual illusions have not yet been introduced into the DNN interpretability research framework. Visual illusions, as a specific visual phenomenon, involve the distortion, alteration, or substitution of reality, primarily arising from the perception of the human visual system on complex visual stimuli composed of various simple patterns24. These illusions may stem from a variety of factors at optical, neural, or cognitive levels. The perceptual characteristics of human vision on optical illusions, involving aspects such as shape, color, relative size and proportion, endow visual illusion images with unique and abundant research value, providing novel perspectives for exploring the workings of human visual system. Research suggests that human brain’s perception on visual illusion scenes is probably the result of independent memory for featural information about individual object alongside global information memory for the relations between different objects25. This characteristic makes visual illusion a powerful research tool, which can be used to explore the understanding capabilities of deep learning models and artificial intelligence systems regarding visual scenes, as well as whether DNNs possess similar perceptual characteristics and limitations as humans26.

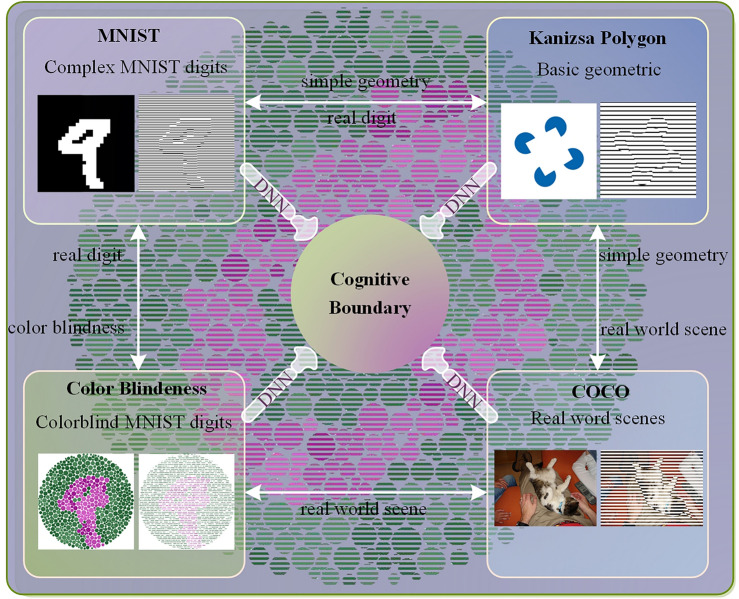

In this study, we propose a novel working capability analysis framework for DNNs (Fig. 1), called the cognitive response model with fine adjustable visual illusion scenes (CRVIS). The framework revolves around the unknown boundary issue of DNNs’ working capability, with the hypothesis that DNN performance may differ from human cognition in certain visual illusion scenes. It conducts a series of cognitive response studies to thoroughly analyze DNN performance across various visual illusion scenes. In particular, our groundbreaking efforts led to the development of a generation method tailored specifically for visual illusion scenes. By leveraging advanced techniques and incorporating key elements from classic visual illusion scenes, such as the Kanizsa figures, the Ehrenstein illusions, the Abutting line gratings and Color Blindness Ishihara plates, we establish adjustable strategies for generating sample images. This innovative model is designed to automate the process of generating scene images equipped with precise semantic labels, including MNIST-Abutting grating, Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating, ColorMNIST-Abutting grating and COCO-Abutting grating scene images. Our studies find that although the recognition ability of DNNs can be infinitely close to the level of human vision, it still has unknown boundary issues in pattern classification, target detection and semantic segmentation. Through extensive cognitive response studies on adjustable visual illusion images, we discover that the robust working performance of DNNs relies entirely on their sample classification ability on similar known scenes, failing to demonstrate a reliance on pattern learning ability achieved through independent memorization like humans. The above discoveries have hardly been reported before in other studies. This work not only expands new cognitive domains on unknown boundary problems between DNNs and human brain cognition, but also provides valuable insights and a robust empirical foundation for interpretable artificial intelligence research.

Figure 1.

CRVIS. This framework primarily contains generation methods for visual illusion scene images, deep neural networks for cognitive boundary detection and adjustable cognitive response processes. These scene images consist of MNIST-Abutting grating scene, Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating scene, ColorMNIST-Abutting grating scene and COCO-Abutting grating scene. The grating images include both horizontal and vertical gratings. White arrows illustrate the connections between different types of visual illusion scenes. Specifically, the DNN represented on the transparent arrow indicates the detection results on the corresponding scene images. The module in the middle serves as both the question and the conclusion, driving experimental research, while also deriving this conclusion from the detection results.

Results

Cognitive response of DNNs on MNIST-Abutting grating scene images

Cognitive response studies of DNNs on MNIST-Abutting grating scenes under CRVIS models aim to analyze the pattern classification ability of DNNs on different unknown scenes and similar known scene images. To facilitate this analysis, it is crucial to generate high-quality visual scenes that accurately represent the MNIST-Abutting grating visual illusion. The MNIST-Abutting grating images generating network (Fig. 2a) comprises three layers, capable of accurately generating high-quality visual scenes with adjustable properties. In the first layer, standard MNIST images are modeled within the Unity platform based on information from MNIST standard binary files, with typical dimensions of 2828. Building upon the optimization of edge details, the network also supports the generation of high-resolution images at any given dimension, providing a foundational framework for creating larger visual scenes. Inspired by the LabelMe method27, the second layer employs an automated annotation technique to calculate label information about visual images, including gradients and rectangle vertices, which correspond to the dimensions of the generated images, ensuring precise mapping between image data and its associated labels. The final layer introduces an adjacent abutting grating generation algorithm, producing visual illusion images with adjustable sparsity levels, allowing for customization based on specific requirements or experimental conditions. In the grating generation process, the core logic utilizes modular arithmetic to compute the width and color of stripes for each pixel position . The calculation formulas for stripe width and color are defined as follows:

| 1 |

| 2 |

Where and denote the width and color of abutting black grating, while and refer to width and color of abutting white grating. This flexibility in generation supports the subsequent evaluation of model performance on Kanizsa Polygon images.

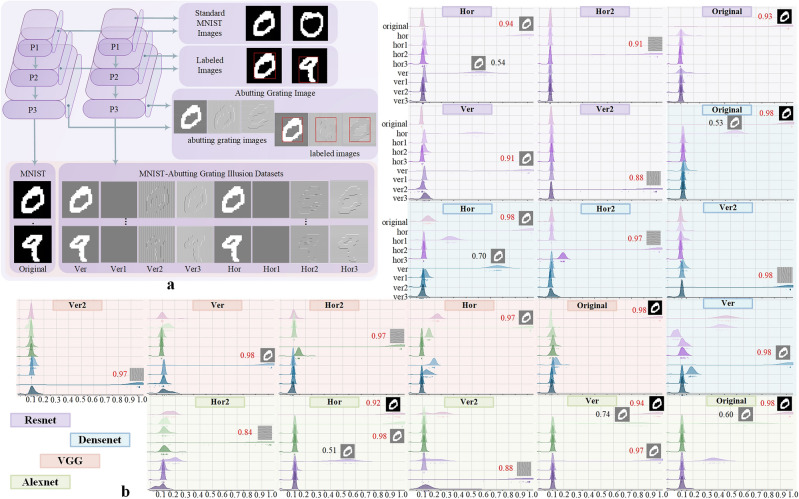

Figure 2.

Cognitive response experiments of DNNs on MNIST-Abutting grating scene images. (a) Overall architecture of scene image generation method for MNIST-Abutting grating visual illusion. The method operates through a systematic top-down inference process, encompassing three distinct stages: firstly, it generates standard MNIST images (P1); then, it automatically generates corresponding labels (P2); finally, utilizing this generated information, MNIST-Abutting grating label images (P3) is produced. (b) Ridgeline plots depicting the pattern classification performance of DNN models on MNIST-Abutting grating visual illusion images.

To assess the capability of deep neural networks (DNNs) in pattern classification, we select four traditional models. We pre-train AlexNet, VGG11, ResNet18 and DenseNet12 models on five types of training sets and conduct extensive classification experiments using adjustable test sets of visual illusion images. The training sets contain Original, Hor, Hor2, Ver and Ver2 scene images, while the test sets include Original, Hor, Hor1, Hor2, Hor3, Ver, Ver1, Ver2 and Ver3. Figure 2b illustrates the classification ability of models on test images, using Mean Accuracy (MA) across all epochs as evaluation metric. The ridgeline plots of classification performance demonstrate high accuracy on similar scene images with known pattern combinations. However, for different scene images with unknown pattern combinations, their accuracy drops to near-random levels. Here, “known patterns” refers to patterns that are the same as the foreground and background patterns in the training images, while “Unknown patterns” refers to patterns that differ from those in the training images. This is especially evident in the VGG11 model, which struggles to classify target digits accurately in different scene images consisting of unknown background patterns (Original, Hor and Ver). For example, VGG11 achieves high accuracy on Original scene images (MA = 0.98) when trained on Original training sets of visual illusion images, yet exhibits a drastic decline in performance to near-random levels when applied to similar scene images after training on Hor or Ver training sets. After training with Hor2 or Ver2 scene images, similar classification results can also be observed, with AlexNet, VGG11, ResNet18 and DenseNet121 models achieving high mean accuracy rates in recognizing target digits only in Hor2 (MA = 0.84, 0.97, 0.91, 0.97) or Ver2 (MA = 0.88, 0.97, 0.88, 0.98) images, while failing to recognize targets in different images with unknown grating sparsity. These findings indicate that, in achieving high-accuracy recognition, DNN models rely on the contextual relationship between foreground and background patterns in scene images, using these relationship weights to identify foreground objects. In particular, we innovatively discover that models lack the ability to independently memorize foreground or background patterns, which directly affects their ability to perceive the similar foreground objects across different scenes.

Cognitive response of DNNs on Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating scene images

Cognitive response studies of DNNs on Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating scenes under CRVIS models aim to analyze the semantic segmentation ability of DNNs on different unknown scenes and similar known scene images. This is supported by adjustable method for generating Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating visual illusion scenes with semantic labels (Fig. 3a). The Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating images generation network consists of three layers, with the first layer playing a critical role in the precise construction of standard visual illusion polygons using geometric modeling algorithm. In the process of generating standard Kanizsa Polygon, key parameters such as vertex coordinates and directed areas are meticulously controlled through precise trigonometric transformations. Specifically, the number of vertices and radius determine the shape and size of polygon. The vertex coordinates are calculated using cosine and sine functions to ensure the vertices are evenly distributed along a circle. This precise coordinate calculation not only guarantees the symmetry of the polygon but also allows for flexibility in adjusting the size and complexity of the polygon by modifying the radius and number of vertices. Additionally, the directed area is computed using the Incremental Area Formula, which accurately determines orientation and area. The formula also distinguishes between clockwise and counterclockwise vertex arrangements, further controlling the polygon’s geometric properties. In this way, the precise control of vertex positions and area not only defines the shape of polygon but also effectively creates the illusory contours seen in Kanizsa figures, generating a powerful visual illusion. Specifically, for each pixel position , the calculations for the vertex coordinates and directed area are as follows:

| 3 |

| 4 |

Where represents the center coordinates of polygon, and is the vertex index ranging from 0 to . This ensures the accurate generation of scene images across different dimensions, maintaining precision throughout the calculation process.

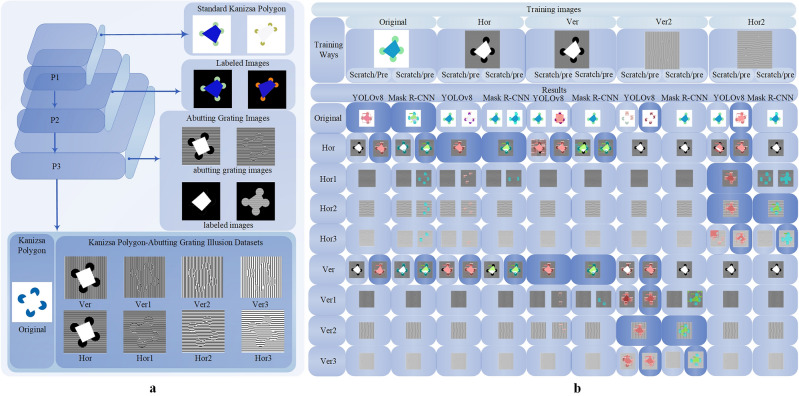

Figure 3.

Overall architecture of generation method for Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating dataset and semantic segmentation results. (a) The generation method comprises a top-down generation process. Initially, the process generates standard Kanizsa Polygon images (P1). Subsequently, it automatically generates corresponding label data (P2). Finally, utilizing the generated information, it produces adjustable label images of visual illusion scenes (P3). This sequential generation process ensures the creation of standardized and comprehensive scene images dataset of Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating visual illusion. (b) This graph displays the segmentation results of YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN models under different training methods. The “Training Ways” row at the top lists various training image variants (Original, Hor, Ver, Ver2, Hor2) along with their respective training methods (Scratch/Pre, indicating training from scratch or using a pre-trained model). On the right, segmentation results of YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN are shown for various test image patterns, including Original, Hor, Hor1, Ver, Ver1, etc. Each cell image demonstrates the model’s segmentation performance on the input, highlighting how these models perform differently under complex visual phenomena. This structure provides a clear comparison of detection accuracy and robustness across different visual illusion images for each model.

In the second layer, semantic labels for standard Kanizsa Polygon images are produced through an automated annotation method, which is based on the accurate positioning of the polygon’s edges. Similar to MNIST-Abutting grating method, the Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating process integrates the abutting grating generation technique with adjustable sparsity levels. This flexibility in generation supports the subsequent evaluation of model performance on Kanizsa Polygon images, particularly in assessing the capability of deep neural networks (DNNs) in target detection and semantic segmentation, for which we select three state-of-the-art models.

This study evaluates the performance of YOLOv8, Mask R-CNN and SAM models across diverse visual patterns, using five different training datasets (Original, Hor, Hor2, Ver and Ver2) and assessing their segmentation capabilities on multiple test datasets (Original, Hor, Hor1, Hor2, Hor3, Ver, Ver1, Ver2 and Ver3). Specifically, the evaluation employs five key metrics: M-IoU, Dice coefficient, F1 score, Recall and Precision. The performance results are visually illustrated as shown in Fig. 3b, and the specific metric values are summarized in Table 1. From the segmentation results, it can be seen that the official pre-trained models are able to accurately identify targets only in simpler patterns like Original, Hor, and Ver images. Specifically, the SAM model exhibits exceptional segmentation accuracy, with M-IoU, Dice and F1 scores exceeding 0.99, alongside recall and precision rates around 0.98. YOLOv8, in comparison, performs significantly lower, achieving an M-IoU of just 0.24, and Dice and F1 scores of 0.35, with a recall rate of only 0.24. Mask R-CNN performs moderately better than YOLOv8, achieving an M-IoU of 0.56 and an F1 score of 0.65, positioning it as an intermediate performer between YOLOv8 and SAM. After fine-tuning with specific patterns (Hor or Ver), all models show considerable improvements in segmentation performance within these trained patterns. SAM continues to excel with M-IoU, Dice and F1 scores surpassing 0.98, demonstrating its robust generalization even across modified visual patterns. YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN also exhibit significant gains, with YOLOv8’s F1 score rising above 0.8 and Mask R-CNN maintaining an F1 score around 0.7. Notably, models fine-tuned on Hor2 achieve exceptionally high recognition accuracy (close to 0.99) for this specific pattern. However, these models struggle with recognition in sparse patterns like Ver2, indicating that despite the similarity in foreground targets between Hor2 and Ver2 patterns, the model still has limitations in the features learned from these known patterns. Similarly, models fine-tuned on Ver2 show high performance (close to 0.90) within the Ver2 test images, yet they exhibit limitations in generalizing to comparable, yet structurally different, patterns like Hor2. Qualitative analysis of segmentation outputs reveals that YOLOv8 captures finer details more effectively than Mask R-CNN, especially in complex pattern scenarios, and produces more accurate segmentation boundaries. This research reveals that while existing models perform efficiently on specific known patterns, they fail to demonstrate pattern learning abilities similar to human independent memorization when faced with unknown scenes containing known foreground objects.

Table 1.

The performance of three models (SAM, YOLOv8, Mask R-CNN) under different image pattern fine-tuning.

The metrics include M-IOU (mean intersection and merger ratio), dice coefficient, F1 score, recall and precision. Each model is represented by a different color, and their performance is evaluated across multiple datasets. Data with similar patterns are highlighted in yellow, emphasizing the segmentation and detection performance of each model under various conditions. Further experimental data and additional analyses are provided in the supplementary file ( Supplementary Information )

Cognitive response of DNNs on ColorMNIST-Abutting grating scene images

Cognitive response studies of DNNs on ColorMNIST-Abutting grating images under CRVIS models aim to analyze target detection ability of DNNs on different unknown scenes and similar known scenes. Leaving on classic characteristics of Abutting line gratings and Color Blindness Ishihara plates, the adjustable method for generating ColorMNIST-Abutting grating scene images with semantic labels, involves five layers (Fig. 4a). In the first layer, a comprehensive approach is adopted to construct scenes based on standard MNIST binary files and Ishihara color test plates. The process involves integrating numerical data from the MNIST dataset with elements related to color blindness perception, specifically derived from Ishihara color plates. This integration allows for the creation of MNIST and Color Blindness Ishihara scenes, where the numerical images are modified to reflect the visual distortions and challenges faced by individuals with various types of color blindness. By combining these two data sources, the resulting scenes not only represent digit recognition but also incorporate the nuanced visual perception differences encountered by people with color vision deficiencies, creating a more inclusive dataset for testing and analysis in the context of color blindness. The recursive process checks adjacent pixels for a pixel point , iterating and within the range . When a traversed pixel meets marking requirements, it is labeled, mathematically expressed as:

| 5 |

In the second layer focuses on recursive or iterative clustering to segment foreground digits from color-blind background. Employing the locally weighted integration technique allows for meticulous consideration of spatial relationships among neighboring pixels, effectively differentiating overlapping digits from complex backgrounds. Advanced algorithms like hierarchical clustering are used to classify pixels into foreground and background categories based on their features. In the third layer, new Color Blindness digital images are merged through a pixel fusion algorithm that extracts pixel features from labeling set and assigns them to corresponding positions in fusion image. Assuming represents the MNIST image, is the fusion image, denotes specific pixel in MNIST image, refers to the labeled sets of pixels, be the feature corresponding to pixel in labeled sets, and is the fusion function used to set pixel features, the image fusion process is mathematically expressed as follows:

| 6 |

This process ensures the accurate representation of color perception as experienced by individuals with color blindness. The fourth layer aligns edge pixel features of foreground digits in ColorMNIST images with the labeled foreground feature sets, utilizing edge detection and alignment algorithms to ensure precise coverage of digit edges, thus maintaining visual clarity in varying color perception scenes. In the fifth layer, the abutting grating generation technique creates grating images with adjustable sparsity levels, effectively simulating the applicability of Color Blindness digital images in experimental environments.

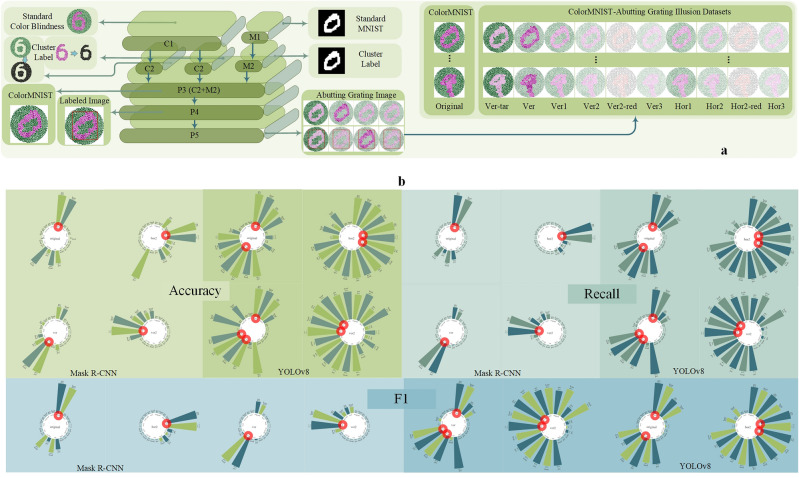

Figure 4.

Cognitive response experiments of DNNs on ColorMNIST-Abutting grating scene images. (a) Overall architecture of visual illusion scenes generation method for ColorMNIST-Abutting grating. The method comprises five steps in a top-down inference manner. Initially, standard Color Blindness images (C1) and MNIST images (M1) are generated. Subsequently, clustering label pixels in images, considering both background and foreground patterns in Color Blindness (C2) and MNIST images (M2). Using this data, new Color Blindness images, referred to as ColorMNIST (P3), and corresponding label data (P4) are automatically generated. Finally, adjustable label images of ColorMNIST-Abutting grating visual illusion scenes are produced. (b) Radar chart representation of precision, recall and F1 score. The center represents training set, with rays for each test set labeled with metric values. Accurately segmented images are highlighted with red circles.

To comprehensively evaluate the working capability of DNN models in target detection, we evaluate both pre-trained and scratch-trained YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN models. These models are trained on ColorMNIST-Abutting Grating visual illusion datasets (Original, Ver, Ver2, Hor2), and their detection capabilities are depicted in (Fig. 4b). Performance metrics, including F1 score, precision, and recall, are used for accuracy evaluation. The radar charts reveal significant boundary detection issues across the models. Specifically, both pre-trained and scratch-trained Mask R-CNN models struggle to detect similar foreground digits in images with unknown background patterns. YOLOv8 models also exhibit limitations in detection across different scenes. For example, when trained on Original scene images, the pre-trained Mask R-CNN models demonstrate superior detection accuracy (precision = 94%, recall = 94%, F1 score = 94%) compared to the scratch-trained models (precision = 89%, recall = 89%, F1 score = 89%). In contrast, they fail to detect foreground digits accurately in different scene images. Similar detection results are observed after training with Hor2 or Ver2 scene images. For Hor2-trained models, both scratch-trained (precision = 90%, recall = 90%, F1 score = 90%) and pre-trained (precision = 93%, recall = 93%, F1 score = 93%) Mask R-CNN models detect only Ver2 images accurately, with low detection rates for others. YOLOv8, even scratch-trained models, achieve high accuracy on Hor2 (precision = 93%, recall = 93%, F1 score = 93%) and Hor2-red (precision = 97%, recall = 96%, F1 score = 97%) images, but lower accuracy on others. This experiment further confirms that the limitations in model detection stem from the lack of independent learning and memorization of foreground and background patterns. By adding color features for comparison, the study found that even with distinct color gradients, the boundary issues in detection capabilities remain unresolved, highlighting the importance of independent pattern memorization.

Cognitive response on mixed visual illusion scenes and COCO images

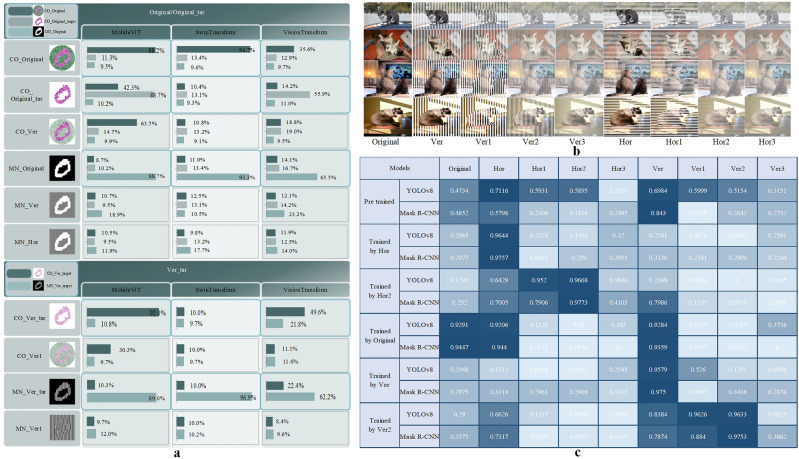

To further validate the performance of DNNs in classification ability boundaries, we introduce three advanced computer vision algorithms based on Transformer models, including Vision Transformer (ViT), Mobile Vision Transformer (MobileViT) and Swin Transformer. These pre-trained models are trained on five scene image sets, including Original MNIST images (MN_Original), Original Colorblind images (CO_Original) and Original Colorblind target images (CO_Original_target), to evaluate classification performance on different scenes with known foreground digit patterns. Additionally, vertical grating MNIST target images (MN_Ver_target) and vertical grating Colorblind target images (CO_Ver_target) sets are used for evaluating classification on different scenes with known foreground grating digit patterns. (Fig. 5a) shows the target classification results on test images, with average accuracy as the evaluation metric.

Figure 5.

Comparison of detection and segmentation performance of different models across various visual illusion scene images. (a) Presents the object detection accuracy of models such as MobileViT, SwinTransform and VisionTransform, with percentages indicating the classification accuracy of each model fine-tuned on different image patterns. (b) Examples of different image modes from the COCO dataset, highlighting variations in stripe width, transparency and overall visual complexity. These samples are valuable for assessing the ability of cognitive models to recognize patterns under challenging conditions. (c) Compares the segmentation performance of YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN on the COCO dataset, where color intensity represents segmentation accuracy-darker shades indicate higher accuracy, while lighter shades represent lower performance.

The bar charts of classification performance after training on MN_Original images show that all models (ViT, MobileViT, Swin Transformer) can correctly classify only similar images with known patterns (MN_Original), achieving average accuracies of 0.89, 0.93 and 0.66 respectively. For different images with the same or similar foreground digits (MN_Ver, MN_Hor, CO_Original, CO_Original_target, Co_Ver), the classification accuracies are at random levels. As well, although CO_Original, CO_Original_target and CO_Ver scene images have same foreground digits, models trained on CO_Original_target images could not recognize foreground digits in either CO_Original or Co_Ver images. The bar chart depicting classification accuracy after training on CO_Original scene images clearly shows that the performance of Swin Transformer model is consistent with the models trained on MN_Original, achieving high accuracy only in classifying CO_Original scene images (average accuracy = 0.95). Furthermore, after training on MN_Ver_target images, all models achieve average accuracies of 0.63, 0.89 and 0.97, respectively, with high classification performance on MN_Ver_target images but poor performance on other scene images. In particular, the Swin Transformer model even struggles to correctly classify foreground digits (average accuracy = 0.13) in similar images with known patterns. Moreover, after training on CO_Ver_target images, the MobileViT model achieves higher accuracy on similar images (CO_Ver_target), ViT model performs slightly worse, and Swin Transformer has random_level accuracy. These results further highlight the performance deficiencies of Swin Transformer model. In conclusion, even with the Swin Transformer models, boasting three billion parameters, or ViT model with 22 billion parameters, they still fail to recognize similar foreground objects in different scene images. These results not only further confirm the existence of boundary issues in classification performance, but also validate that DNN models lack an independent memory process for foreground patterns in scene images. This significant discovery provides us with a new way to solve the limitations of model performance.

In the process of constructing COCO visual illusion images dataset, we selected the original images of the cat category from the COCO dataset as the base samples (Fig. 5b), and the dataset is referred to as COCO-Abutting grating scene images. Based on these original images, we applied stripe masking effects with different directions and intervals to generate multiple variants with occlusion effects. These stripe masks are mainly divided into two types: vertical stripes and horizontal stripes, labeled as the “Ver” series and the “Hor” series, respectively. In the vertical direction, we generated images with various densities and transparency levels, such as Ver, Ver1, Ver2, and Ver3. Similarly, for the horizontal direction, we generated Hor, Hor1, Hor2, and Hor3 images with different densities and transparency levels. To create the stripe patterns, we systematically adjusted the stripe width and transparency, achieving occlusion effects that ranged from prominent to subtle. This approach helps to build a diverse sample set in terms of visual occlusion intensity, providing more robust samples for model training. Additionally, to make the stripe effects more prominent, we chose a light blue background for the dataset, which enhances the visual contrast of the striped images. Through these steps, we created a diverse cat image dataset to allow the model to learn and perform effectively under different occlusion conditions.

In this cognitive response experiment, we evaluate the performance of two models, YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN, under various masking types and training conditions (Fig. 5c). By comparing the results across different models, we observe changes in model performance under different training data and occlusion conditions. For pre-trained models, YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN perform similarly on the original image, achieving high M-IoU and Dice coefficients. However, under horizontal and vertical stripe occlusions, their performances vary significantly. YOLOv8 maintains relatively high F1 scores and precision under lighter horizontal occlusions (Hor and Hor1), especially excelling in these conditions; however, its performance drops substantially under more severe occlusions (such as Ver2). Mask R-CNN shows more stability under higher-density occlusions (like Hor2 and Ver2), performing slightly worse than YOLOv8 under horizontal occlusions, but considerably better under vertical occlusions (such as Ver and Ver3). When trained on specific occlusion types (Hor, Hor2, Ver, Ver2), both models demonstrate enhanced performance. For the model trained on Hor data, YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN achieve extremely high performance under Hor occlusion, with M-IoU and Dice coefficients exceeding 0.96. Similarly, the model trained on Hor2 data shows a comparable trend, with Mask R-CNN achieving an F1 score as high as 0.98 under Hor2 occlusion, and YOLOv8 showing close precision and recall values. This indicates that training with similar occlusion data can improve model robustness in corresponding occlusion conditions. Moreover, models trained on the original data perform well under mild occlusion conditions (Hor and Ver), with both YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN reaching M-IoU values above 0.93. Additionally, when trained on Ver occlusion data, both models achieve their highest performance under vertical occlusions, with M-IoU exceeding 0.95, indicating that training on vertical occlusion data effectively enhances robustness under vertical occlusion conditions. Overall, YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN show different sensitivities to various occlusion types: YOLOv8 performs slightly better under horizontal occlusions, while Mask R-CNN excels under vertical occlusions. Additionally, training on occluded data specific to each direction effectively enhances model robustness in handling those specific occlusions, providing valuable insights for real-world applications where occlusion is a common challenge.

Discussion

This study delves into the unknown boundary issue presented by the working capability of deep neural networks (DNNs) when handling lots of complex tasks. By introducing pioneering cognitive response framework (CRVIS), we thoroughly analyze the performance of DNNs across adjustable visual datasets as well as various tasks such as pattern classification, object detection and semantic segmentation. Through response analysis, we aim to investigate underlying mechanisms of analyzable boundary issues in robustness and generalization capabilities of DNNs. We observed that DNNs demonstrate superior accuracy and reliability in processing similar images, composed of known foreground and background patterns. However, when dealing with dissimilar scene images, consisting of unknown patterns, the working performance of models sharply declines. This phenomenon is purely attributed to the occurrence of errors or misclassifications in models due to changes in foreground or background patterns, even in dissimilar images where foreground patterns remain the same. These results intuitively demonstrate that unknown boundaries exist within working capability of DNNs. These boundaries highlight challenges DNNs face when generalizing to dissimilar situations, reflecting our limited comprehension of working capability boundary. Meanwhile, viewed from foundational theoretical perspective, findings reveal that, although DNNs’ working capability infinitely approximates the perceptual level of humans in handling complex tasks, they still cannot fully emulate visual cognitive mechanisms of human brain. Specifically, they cannot realize the cognitive mechanism of independent pattern memorization, leading to poor or even failed performance in certain situations. This study contributes a novel, analyzable and adjustable experiment framework for exploring boundary issues in cognitive capabilities, essential for uncovering the similarities and differences between AI and human cognition. Additionally, these findings contribute valuable insights into further exploring how to bridge the gap between DNNs and human28. By accurately recognizing the specific constraints of DNNs in independent pattern memorization, researchers can expand new methods to enhance the cognitive abilities of AI systems.

The experimental results show that across a large number of cognitive tasks with adjustable visual illusion scenes, the AlexNet, VGG11, ResNet18, DenseNet121, YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN models, as well as the hyperparametric Vision Transformer (ViT), MobileViT, Swin Transform and SAM models, all exhibit consistent cognitive regularity. This regularity demonstrates that models can accurately recognize target objects only in similar known scenes, while failing to recognize images from unknown scenes. In particular, although unknown scenes contain the same foreground objects, the detection performance of DNNs is still significantly worse. This strongly supports the perspective that DNNs lack holistic independent memorization for foreground patterns in scene images. More recent research has primarily focused on improving models’ working performance by adjusting contextual classification weights between foreground and background patterns, without finding any significant evidence to confirm the importance of holistic independent pattern perception. Although the current evidence on the relationship between DNNs’ cognitive boundary and independent pattern memorization is limited, it is consistent with earlier holistic studies of Gestalt principles, suggesting that the existence of unknown boundary is closely related to the holistic independent perceptual memorization of foreground patterns. Future research could delve into the nature of this correlation, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of limitations that deep neural networks face in handling complex tasks. Such studies would contribute to the development of more effective methods to optimize model performance, thereby enhancing their applicability and robustness across various tasks.

Even so, this research framework conducts extensive performance analysis experiments of DNNs on simple visual illusion phenomena composed of MNIST digits or polygons. Such simplified scenes probably restrict the applicability range of conclusions, particularly in complex scenes. For visual illusion phenomena in complex scenes, generation methods for images with precise labels also appear to be more challenging. In simple scenes, only geometric shapes and basic visual illusion effects are typically considered. In complex scenes, additional factors and techniques, such as image segmentation, lighting simulation and object recognition, may be necessary for more accurate simulation of visual illusion scenes in real world. In this way, future research could employ labeled image datasets of complex visual illusion scenes closer to real world for deeper validation and reflection on analyzed conclusions. With such research, it will contribute to a better understanding of working performance of deep neural networks in dealing with complex visual illusion situations, and provide more reliable guidance and solutions for practical applications. Besides, our conclusions contribute valuable references and insights into the cognitive mechanisms and learning processes of DNN models, establishing a foundation to further explore and enhance cognitive capabilities of neural networks. Nevertheless, enhancing the cognitive capability of AI systems would require more intensive investigation of specific limitations of DNN modes in independent pattern memorization. This may involve designing new neural network architectures, optimizing modules specifically for independent pattern memorization, as well as considering the utilization of reinforcement learning techniques or meta-learning methods to further improve the model’s adaptability when confronted with unknown scenes. Additionally, it may be beneficial to explore graph-based networks, such as the approach described in the paper by N. Khaleghi et al., titled “Developing an efficient functional connectivity-based geometric deep network for automatic EEG-based visual decoding”29,30. Future research should also focus on how to apply the findings from the visual illusion datasets constructed in this study to real-world scenarios. Although experiments are conducted on specific datasets, these datasets reflect the complexities of real environments, including variations in lighting, occlusions, and background interference. These efforts enable us to realize smarter AI systems with human cognitive characteristics.

In summary, this study is not only an insight into the cognitive capability of deep neural networks (DNNs), but also a significant revelation of challenges that artificial intelligence systems confront when dealing with complex cognitive tasks. This contributes to advancing the field of artificial intelligence, thereby achieving more intelligent and interpretable AI systems.

Methods

Experiments design

This study proposes a novel framework for analyzing the cognitive capability of deep neural networks (CRVIS), aiming to explore the unknown boundary issue between DNN and human cognitive ability. Innovatively departing from the perspective of visual illusions, this framework breaks through traditional approaches to interpretable boundary research, investigating the simulation and cognitive situation of DNN on human brain vision. The study found that there is indeed a boundary situation in target classification, target detection and target segmentation capabilities of DNN models. Furthermore, we discovered that the fundamental reason for this phenomenon is that DNNs cannot independently memorize foreground object patterns in scene images in the same way as humans.

Data collection and preprocessing

The study introduces an intelligent generation method capable of creating visual illusion images based on the properties and principles of classic visual phenomena, such as Kanizsa figures, Ehrenstein illusions, and Abutting line gratings. This method generates standardized image datasets of visual illusion scenes, including MNIST-Abutting grating, Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating, ColorMNIST-Abutting grating, and COCO-Abutting grating images. The MNIST-Abutting grating visual illusion dataset consists of nine types of scene images: original MNIST images (Original), background vertical grating scene images (Ver), fully vertical grating scene images with a sparsity level of one (Ver1), fully vertical grating scene images with a sparsity level of two (Ver2), fully vertical grating scene images with a sparsity level of three (Ver3), background horizontal grating scene images (Hor), fully horizontal grating scene images with a sparsity level of one (Hor1), fully horizontal grating scene images with a sparsity level of two (Hor2), fully horizontal grating scene images with a sparsity level of three (Hor3). The Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating and ColorMNIST-Abutting grating visual illusion scene dataset contain the same patterns of images, including Original, Ver, Hor, Ver1, Ver2, Ver3, Hor1, Hor2, Hor3. Among them, the training set consists of Original, Hor, Hor2, Ver and Ver2, while the test set includes all pattern images. The ColorMNIST-Abutting grating dataset is divided into eleven patterns: original pattern images (Original), background grating pattern images (Ver, Hor), foreground grating pattern images (Ver-tar), and fully grating pattern images (Ver1, Ver2, Ver3, Hor1, Hor2, Hor3). Additionally, this dataset includes ver2-red and Hor2-red patterns, which refer to fully vertical or horizontal grating scene images containing a color blindness test plate with black-red color scheme. In this dataset, the training set includes the patterns of Original, Ver-tar, Hor2 and Ver2. The MNIST-Abutting grating dataset includes a total of 126,000 images, evenly split into 63,000 images for training and 63,000 images for testing. The Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating dataset consists of 48,150 images. The ColorMNIST-Abutting grating dataset comprises 42,850 images, with 28,000 images allocated for training and 14,850 images for testing. Finally, the COCO-Abutting grating dataset consists of 37,026 images.

MNIST-Abutting grating visual illusion images

The image preprocessing process for AlexNet, VGG11, ResNet18, and DenseNet121 includes several essential steps to ensure optimal input for these convolutional neural network architectures. First, images are resized to a standardized size of 224 224 pixels, to meet the input requirements of the models. Next, pixel values are normalized, or by scaling them from the range of 0-255 to a range of 0–1, or by applying mean subtraction and division by standard deviation, ensuring consistent data distribution. Additionally, color space conversion from BGR to RGB may be performed to align with the expected input format. Data augmentation techniques such as random cropping, rotation, flipping, and color jittering are employed to increase the diversity of the training dataset, thereby enhancing the models’ robustness and generalization capabilities. Finally, the processed images are converted into PyTorch Tensor format and batched for efficient training, facilitating smooth model optimization and performance.

Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating visual illusion image

The image preprocessing process for YOLOv8, Mask R-CNN and SAM involves several key steps to ensure compatibility with model requirements. First, input images are resized to specified size of 640 640 pixels to maintain consistency across dataset. Next, pixel values are normalized from range of 0–255 to 0–1 by dividing by 255, and color space conversion from BGR to RGB is performed to align with training data. Additionally, data augmentation techniques, such as random cropping, rotation, flipping and color jittering, are applied to enhance the diversity of training dataset and improve model robustness.

Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating visual illusion image

The image preprocessing process for YOLOv8, Mask R-CNN, and SAM involves several key steps to ensure compatibility with model requirements. First, input images are resized to specified size of 640 640 pixels to maintain consistency across dataset. Next, pixel values are normalized from range of 0–255 to 0–1 by dividing by 255, and color space conversion from BGR to RGB is performed to align with training data. Additionally, data augmentation techniques, such as random cropping, rotation, flipping and color jittering, are applied to enhance the diversity of training dataset and improve model robustness.

ColorMNIST-Abutting grating visual illusion image

The image preprocessing process for Vision Transformer (ViT), Mobile Vision Transformer (MobileViT), and Swin Transformer involves several standardized steps to prepare the input data. Initially, images are resized to a fixed dimension of 224224 pixels. Next, pixel values are normalized, from a range of 0-255 to 0-1. Color space conversion from BGR to RGB may also be performed to match the training data format. To enhance the diversity of training dataset, data augmentation techniques are applied. Finally, the processed images are converted into PyTorch Tensor format and batched together for efficient training.

Cognitive response experimental methods for DNNs

In this study, thorough consideration is given to model selection, with ten representative deep neural network models chosen from the current cutting-edge technologies in the field of deep learning. These models include traditional convolutional neural networks such as AlexNet, VGG11, ResNet18 and DenseNet121, as well as state-of-the-art object detection and segmentation models like YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN. Additionally, attention-based Transformer models such as Vision Transformer (ViT), Mobile Vision Transformer (MobileViT), and Swin Transformer are included. AlexNet, VGG11, ResNet18, and DenseNet121 are significant convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures in the field of deep learning, promoting the advancement of image classification technology. AlexNet, one of the earliest deep learning models, marked a new era in computer vision with its depth and complexity. VGG11 is known for its simplicity and uniform convolutional layer depth, enhancing model performance by increasing network depth. ResNet18 introduces the concept of residual connections, effectively alleviating the vanishing gradient problem in deep networks, enabling the training of much deeper networks. DenseNet121 is suitable for resource-constrained environments through efficient feature utilization and fewer parameters. This experiment aims to evaluate the performance of these four models on visual illusion dataset, providing reference points for selecting appropriate deep learning models. YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN are powerful tools in the field of object detection and segmentation, demonstrating the application potential of deep learning across different tasks. Mask R-CNN employs a two-stage detection process, first generating candidate regions and then classifying and regressing bounding boxes. YOLOv8 uses a single-stage process that directly maps the input image to bounding boxes and class probabilities. YOLOv8 is known for its real-time and efficient performance for fast processing scenes, while Mask R-CNN provides high accuracy and fine-grained segmentation capabilities, suitable for tasks that require precise segmentation. This enables to compare two different detection and segmentation strategies, assessing their performance on visual illusion dataset and offering a comprehensive perspective for research in the field of object detection and segmentation. Vision Transformer (ViT), Mobile Vision Transformer (MobileViT), and Swin Transformer demonstrate different design ideas from traditional CNNs, representing revolutionary applications of the emerging Transformer architecture in computer vision, further expanding the boundaries of deep learning. ViT model achieves remarkable classification performance by segmenting images into small patches and treating them as sequence data. MobileViT optimizes the application efficiency by combining the strengths of Transformers and lightweight convolutional networks. Swin Transformer employs a hierarchical structure and sliding window mechanism to maintain low computational complexity. They demonstrate the potential of Transformer architectures in computer vision and provide new directions for future research and development. Additionally, the Segment Anything Model (SAM) enhances segmentation performance by enabling efficient segmentation across diverse image contexts.

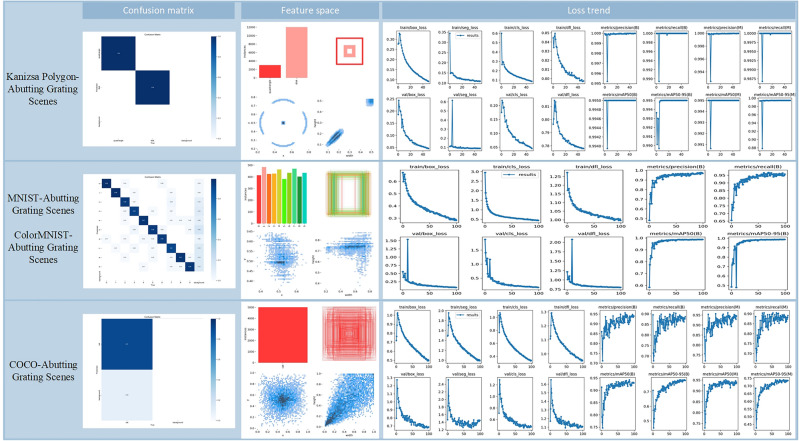

To demonstrate the training performance of models on different datasets, we present the training results of YOLOv8, including confusion matrices, feature space distributions and loss function trends (Fig. 6). Specifically, the confusion matrix reveals the accuracy in classifying various categories, as well as the patterns of misclassification, aiding in the analysis of model biases and sources of errors. The feature space distribution plot illustrates how samples from different categories are distributed in the high-dimensional feature space, providing a visual aid to understand the model’s ability to separate and distinguish between categories. The loss trend graph reflects the changes in the loss functions during training process, including classification loss, localization loss and other auxiliary loss terms, thereby revealing the progress and stability of model’s optimization. These metrics enable a comprehensive evaluation of the performance of models in handling visual illusion data and provide valuable insights for further optimization of training strategies.

Figure 6.

Training performance of YOLOv8 models on Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating, ColorMNIST-Abutting grating and COCO-Abutting grating visual illusion images. The confusion matrix reflects the classification accuracy, with the Kanizsa dataset showing the best performance and COCO dataset displaying more misclassifications. The feature space plots show the distribution of samples from different categories, where the Kanizsa dataset exhibits clear separability, while the COCO dataset has more dispersed distributions. The loss trend graphs illustrate the changes in loss functions during training, indicating smooth convergence on simpler tasks and slower, more fluctuating convergence on more complex tasks.

Cognitive response on MNIST-Abutting grating scene images

We select four traditional convolutional neural networks, including AlexNet, VGG11, ResNet18 and DenseNet121. Specifically, AlexNet is a deep convolutional neural network composed of five convolutional layers, three max pooling layers, two normalization layers, two fully connected layers, and one SoftMax layer. Each convolutional layer utilizes convolutional filters and the ReLU activation function to extract features, while the max pooling layers reduce the dimensionality of feature maps and enhance the model’s robustness. The fully connected layers flatten the feature maps into one-dimensional vectors and learn complex relationships, ultimately producing a probability distribution for each class through the SoftMax layer to complete multi-class classification tasks. VGG11 is a deep convolutional neural network with a structure that includes eleven layers, consisting of eight convolutional layers and three fully connected layers. Its design philosophy is to use multiple small convolutional kernels (33) for feature extraction, stacking several convolutional layers to increase network depth. Each convolutional layer is followed by a ReLU activation function to enhance non-linear expressiveness. ResNet18 is a deep convolutional neural network that employs a residual learning framework, consisting of eighteen layers, including sixteen convolutional layers and two fully connected layers. The key innovation of ResNet18 lies in the introduction of residual connections, allowing the network to directly learn the residual between the input and output, thereby effectively alleviating training difficulties associated with deep networks. DenseNet121 is a deep convolutional neural network known for its distinctive dense connectivity architecture. The model comprises one hundred twenty-one layers, including up to one hundred seven convolutional layers. A key feature of DenseNet121 is that each layer is directly connected to all preceding layers, facilitating more efficient feature propagation and reuse within the network, which significantly enhances model performance and training efficiency.

Cognitive response on Kanizsa Polygon-Abutting grating scene images

YOLOv8, as a real-time object detection model, can quickly identify and locate various visual elements in visual illusion scenes. Mask R-CNN has fine segmentation capabilities that generate high-quality masks for each object, which is crucial for processing visual illusion images as it accurately distinguishes between different regions and shapes. Additionally, the Segment Anything Model enables precise delineation of complex patterns in visual illusions. The architecture of YOLOv8 consists of backbone network, feature aggregation neck, and head for bounding box prediction and classification. The backbone network usually employs an efficient convolutional neural network (CNN) for feature extraction. The neck utilizes the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) to aggregate features from different scales, while the head produces the final predictions. During fine-tuning phase, pre-trained weights are used for transfer learning to accelerate convergence process and enhance the generalization capabilities. Weights are initialized using a zero-mean Gaussian distribution (with a standard deviation of 0.01), while biases are initialized to zero. The loss function comprises composite losses, including bounding box regression loss, confidence loss, and classification loss, to comprehensively evaluate model performance. The model utilizes the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.01. The dimensions of convolutional kernels are 3 3 and 1 1, with stride set to 1. Mask R-CNN is a region-based deep learning framework designed for object detection and instance segmentation tasks. Its architecture comprises several core components. First, the Backbone is used to extract image features, using FPN (Feature Pyramid Network). Next, the Region Proposal Network (RPN) generates candidate object regions and evaluates foreground and background of each region. Subsequently, the RoIAlign technique precisely aligns the features of these candidate regions, preserving spatial information. Finally, the model utilizes a classification head and bounding box regression head for object classification and bounding box prediction, along with a mask branch that generates binary segmentation masks for each instance, enabling accurate segmentation of the objects. In the fine-tuning training phase, the initial learning rate is set to 0.005, with momentum parameter configured at 0.9 and weight decay set to 1e-4 to avoid overfitting. The loss function comprises composite losses, including region proposal classification loss, bounding box regression loss, and mask loss. The optimizer used is SGD, which often performs better as basic optimizer. The dimensions of convolutional kernels are 3 3 and 1 1, with the stride set to 1. Additionally, Batch Normalization and data augmentation strategies are employed during training. SAM (Segment Anything Model) is a segmentation model proposed by Meta that breaks traditional boundaries by training on over 1 billion masks across 11 million images. Its architecture consists of three main components: an image encoder, a prompt encoder, and a mask decoder. The image encoder employs a Vision Transformer (ViT) pre-trained with MAE, which is suitable for processing high-resolution inputs. The prompt encoder processes two types of prompts: sparse (points, boxes, text) and dense (masks), utilizing positional encodings and convolutional embeddings for representation. The lightweight mask decoder predicts segmentation masks based on embeddings from both the image and prompt encoders, with all embeddings updated by decoder blocks that utilize self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms. In the fine-tuning training phase, SAM utilizes the Self-Adaptive Moment Estimation optimizer, which combines the advantages of Adam and RMSprop, allowing for dynamic adjustment of the learning rate to enhance convergence. The loss function is a linear combination of Focal Loss and Dice Loss, where Focal Loss addresses class imbalance issues, while Dice Loss measures the overlap between predicted masks and ground truth masks. The initial learning rate is set to 0.001, with convolutional kernel dimensions of 2 2 and 1 1, and the stride set to 2.

Cognitive response on ColorMNIST-Abutting grating scene images

The Vision Transformer, Mobile Vision Transformer and Swin Transformer models have powerful feature extraction capabilities and multi-scale processing abilities. By utilizing self-attention mechanisms, they capture both local and global features in Color Blindness images, thereby addressing the visual challenges faced by color-blind users. The Vision Transformer (ViT) is a deep learning model based on the Transformer architecture that effectively learns global information and long-range dependencies among pixels in images through self-attention mechanisms. The architecture of ViT consists of three main components: the Embedding layer, the Transformer Encoder, and the MLP Head. The Embedding layer transforms input image into a sequence of tokens. Transformer Encoder is the core of ViT, responsible for handling input token sequences and producing a representation vector rich in information. This component is composed of multiple stacked Transformer Blocks, each consisting of a self-attention mechanism and a feed-forward neural network. The self-attention mechanism captures long-distance dependencies in input sequence, the latter enhances the representation ability of model. MLP Head serves as the output layer, converting the output of Transformer Encoder into final prediction, consisting of a fully connected layer and a softmax layer for classification or regression tasks. In the fine-tuning training phase, ViT model employs SGD as optimizer, with initial learning rate and learning rate factor set to 0.01, and momentum parameter set to 0.9. The loss function used is cross-entropy loss, and the dimensions of convolutional kernel are chosen as 3 3, with stride set to 2. MobileViT is a lightweight vision model based on ViT architecture, combining the strengths of CNN and transformer. Its architecture consists of convolutional layers, MobileViT Block, global pooling layers and fully connected layers. MobileViT Block extracts local features through n n convolutional layers, adjusts channel dimensions with 1 1 convolutional layers, and employs a transformer module with an “unfold-transformer-fold” mechanism for global feature extraction. This module utilizes grouped self-attention to reduce computational complexity while preserving the ability to capture global information. Finally, residual connections merge the original feature maps with the feature maps processed by the transformer, yielding the final output feature map. In the fine-tuning training phase, the model utilizes the Cross Entropy Loss function, employs the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0002, and utilizes convolutional kernels of sizes 33 and 11 with a stride of 1. Swin Transformer is a hierarchical Transformer architecture designed for visual domain, effectively enhancing feature extraction capabilities through the introduction of a hierarchical structure and window-based self-attention mechanism. Swin Transformer consists of multiple Swin Transformer Blocks, each containing window self-attention, shifting window mechanism, and multi-layer perceptron (MLP) layer. The window self-attention computes self-attention within local windows, with the window size dynamically adjustable to improve computational efficiency. The shifting window mechanism allows for the adjustment of window positions between different layers, enhancing information flow. The MLP layer further processes features, including fully connected layers and activation functions, thereby improving the expression ability of model. In the fine-tuning training phase, the Swin Transformer model utilizes AdamW as optimizer, with initial learning rate set to 0.01 and weight decay of 0.05. The dimension of convolution kernel is 3 3, and the strides used for different feature layers are 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 respectively, to adapt to varying downsampling requirements and multi-scale target detection characteristics (Supplementary Information).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62272201) and the Qing Lan Project of Jiangsu Province (Zhenping Xie).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: T.L., Z.X., R.L. Methodology: T.L., Z.X., R.L. Investigation: T.L., Z.X. Visualization: T.L., Z.X. Supervision T.L., Z.X. Writing (original draft): T.L., Z.X. Writing (review and editing): T.L., Z.X. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Data availibility

The datasets used in this study are entirely generated by ourselves. We confirm that we strictly adhered to all relevant ethical standards and data usage agreements during the generation and utilization of the data. The generated raw experimental dataset will be publicly available at Zenodo repository https://zenodo.org/records/10986135.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Silver, D. et al. A general reinforcement learning algorithm that masters chess, shogi, and go through self-play. Science362, 1140–1144 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin, X. et al. All-optical machine learning using diffractive deep neural networks. Science361, 1004–1008 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li, Y. et al. Competition-level code generation with alphacode. Science378, 1092–1097 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidhuber, J. Deep learning in neural networks: An overview. Neural Netw.61, 85–117 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silver, D. et al. Mastering the game of go without human knowledge. Nature550, 354–359 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Mousavi, S. M. & Beroza, G. C. Deep-learning seismology. Science377, eabm4470 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Onen, M. et al. Nanosecond protonic programmable resistors for analog deep learning. Science377, 539–543 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carleo, G. & Troyer, M. Solving the quantum many-body problem with artificial neural networks. Science355, 602–606 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mi, X., Zou, B., Zou, F. & Hu, J. Permutation-based identification of important biomarkers for complex diseases via machine learning models. Nat. Commun.12, 3008 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wetzstein, G. et al. Inference in artificial intelligence with deep optics and photonics. Nature588, 39–47 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, G., Scherr, F. & Maass, W. A data-based large-scale model for primary visual cortex enables brain-like robust and versatile visual processing. Sci. Adv.8, eabq7592 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Yu, F. et al. Brain-inspired multimodal hybrid neural network for robot place recognition. Sci. Robot.8, eabm6996 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Peterson, J. C., Bourgin, D. D., Agrawal, M., Reichman, D. & Griffiths, T. L. Using large-scale experiments and machine learning to discover theories of human decision-making. Science372, 1209–1214 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavin, A. et al. Technology readiness levels for machine learning systems. Nat. Commun.13, 6039 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amann, J. et al. Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: A multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak.20, 1–9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell.1, 206–215 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang, H. et al. Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature620, 47–60 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alif, M. A. R. & Hussain, M. Yolov1 to yolov10: A comprehensive review of yolo variants and their application in the agricultural domain. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.10139 (2024).

- 19.He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P. & Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. 2961–2969 (2017).

- 20.Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 10012–10022 (2021).

- 21.Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 4015–4026 (2023).

- 22.Schyns, P. G., Snoek, L. & Daube, C. Degrees of algorithmic equivalence between the brain and its dnn models. Trends Cognit. Sci.26, 1090–1102 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez-Villa, A., Martin, A., Vazquez-Corral, J. & Bertalmío, M. Convolutional neural networks can be deceived by visual illusions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 12309–12317 (2019).

- 24.Todorović, D. What are visual illusions?. Perception49, 1128–1199 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ben-Shalom, A. & Ganel, T. Object representations in visual memory: Evidence from visual illusions. J. Vis.12, 15–15 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adriano, A., Rinaldi, L. & Girelli, L. Visual illusions as a tool to hijack numerical perception: Disentangling nonsymbolic number from its continuous visual properties. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform.47, 423 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torralba, A., Russell, B. C. & Yuen, J. Labelme: Online image annotation and applications. Proc. IEEE98, 1467–1484 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charpentier, M. J. et al. Same father, same face: Deep learning reveals selection for signaling kinship in a wild primate. Sci. Adv.6, eaba3274 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Khaleghi, N., Rezaii, T. Y., Beheshti, S. & Meshgini, S. Developing an efficient functional connectivity-based geometric deep network for automatic EEG-based visual decoding. Biomed. Signal Process. Control80, 104221 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, T., Wang, F. & Xie, Z. Space topology change mostly attracts human attention: An implicit feedback VR driving system. In 2023 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW). 853–854 (IEEE, 2023).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are entirely generated by ourselves. We confirm that we strictly adhered to all relevant ethical standards and data usage agreements during the generation and utilization of the data. The generated raw experimental dataset will be publicly available at Zenodo repository https://zenodo.org/records/10986135.