Abstract

Lipid metabolism is critical for male reproduction in plants. Many lipid-metabolic genic male-sterility (GMS) genes function in the anther tapetal endoplasmic reticulum, while little is known about GMS genes involved in de novo fatty acid biosynthesis in the anther tapetal plastid. In this study, we identify a maize male-sterile mutant, enr1, with early tapetal degradation, defective anther cuticle, and pollen exine. Using genetic mapping, we clone a key GMS gene, ZmENR1, which encodes a plastid-localized enoyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) reductase. ZmENR1 interacts with β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase (ZmHAD1) to enhance the efficiency of de novo fatty acid biosynthesis. Furthermore, the ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex is regulated by a Maize Male Sterility 1 (ZmMS1)-mediated feedback repression loop to ensure anther cuticle and pollen exine formation by affecting the expression of cutin/wax- and sporopollenin-related genes. Intriguingly, homologous genes of ENR1 from rice and Arabidopsis also regulate male fertility, suggesting that the ENR1-mediated pathway likely represents a conserved regulatory mechanism underlying male reproduction in flowering plants.

Subject terms: Plant breeding, Pollen, Plant molecular biology

Authors identify a genic male sterility gene, ZmENR1, in maize and report that it encodes an enoyl carrier protein reductase that forms heterodimers with ZmHAD1 to ensure maize pollen and anther development through regulating lipid and ROS metabolism.

Introduction

The anther and pollen are essential for sexual reproduction and crop yield1. Anther, the male reproductive organ of flowering plants, is bilaterally symmetrical with two thecae each consisting of an abaxial (lower) and adaxial (upper) lobe. In each lobe/locule, the microspores (that later become pollen grains) are surrounded by somatic cell layers1. Pollen is the male gametophyte of flowering plants with a multi-layered cell wall2. Anther cuticle and pollen exine, covering the outermost layers of the anther epidermis and pollen wall, respectively, are two crucial lipid layers for the normal development of the anther and pollen3. The anther cuticle protects all inner anther layers and microspores4 and the pollen exine protects pollen during dispersal and participates in pollen–stigma interaction for successful fertilization5–8. Any defect of both layers generally results in genic (nuclear) male sterility (GMS)3.

Anther cuticle and pollen exine are primarily made of cutin/wax and sporopollenin, respectively4,9. Their chemical compositions are fatty acids and their derivatives10, which are synthesized mainly by the cooperation of various subcellular organelles in tapetum, including de novo fatty acid biosynthesis and modification in plastids11 and subsequent elongation and modification in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)3,12. These processes are controlled by several lipid-metabolic GMS genes. More than 80 lipid-metabolic GMS genes have been identified in plants3. Most of them are involved in the generation and transport of cutin/wax and sporopollenin precursors in anther tapetal ER3,6, whereas only ZmMs25/FAR111 in maize, together with its homologous genes AtMs213 in Arabidopsis and OsDPW14 in rice, participates in fatty acid modification in anther tapetal plastids. Thus, genes involved in de novo fatty acid biosynthesis in plastids regulating male fertility still need to be explored.

De novo fatty acid biosynthesis is a fundamental process of the plant life cycle15. In plants, de novo fatty acid biosynthesis is performed by fatty acid synthase (FAS), with acetyl-CoA being used as the starting unit and the malonyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) as the two-carbon elongator15. Plant FAS is an easily dissociable multi-subunit complex consisting of multiple monofunctional enzymes, including β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase (KAS), 3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase (KAR), β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase (HAD), and enoyl-ACP reductase (ENR), and the primary products of which are the saturated acyl-ACPs15. The generated 18:0-ACPs are desaturated by stromal Δ9 stearoyl-ACP desaturases (SAD), whereas some 16:0-ACPs that do not elongate to 18:0-ACPs, are released as free 16:0-ACPs. Acyl-ACP thioesterases further hydrolyze long-chain acyl groups to generate free fatty acids, which are catalyzed to CoA esters by the action of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases (LACS), and these CoA esters are exported to the ER or incorporated into phosphatidylcholine (PC) at the plastid envelope via the lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase16–18. Any defect in de novo fatty acid biosynthesis generally leads to lipid metabolic disorders, ultimately resulting in defective plant growth and development. In Arabidopsis, the kasI mutant is a T-DNA insertion that occurs in the 5-UTR of a KASI gene and exhibits retarded growth and impaired chloroplast division19. In rice, the kasI mutant (an amino acid substitution at A257V in a KASI gene) exhibits a short root phenotype and reduced fatty acid content20. The ospls4/hts1 mutant (an amino acid substitution at A254T in a KAR gene) exhibits premature leaf senescence and reduced chlorophyll content, plant height, and tiller number under normal growth conditions and a severe heat-sensitive phenotype21,22. The oszl16 mutant (a missense mutation at R164T in a HAD gene) displays abnormal chloroplast development23. Notably, these above-mentioned mutants are not loss-of-function mutants. They only cause a decrease in enzymatic activity levels. However, little is known about the de novo fatty acid synthesis genes in plants that specifically affect male fertility.

ENR functions in the final step of the elongation cycle in fatty acid synthesis. It catalyzes the reduction of trans-2-crotonyl-ACP (an enoyl-ACP) to butyryl-ACP (an acyl-ACP) in an NADH- or NADPH-dependent manner18, which then serves as the substrate for another round of synthesis until the saturated acyl-ACP is produced24. This process is essential for growth and development in different species. For example, ENR mutations impede the growth of Escherichia coli at high temperatures25. Overexpression of ENR increases lipid content in mature Brassica napus seeds26. The mutation of an amino acid substitution in MOD1 (Mosaic death1, an ENR homologous gene) impairs fatty acid biosynthesis and leads to mosaic death and semi-dwarfism in Arabidopsis27. Moreover, ENR, serving as the target of the antibacterial agent family diazoborane and triclosan (broad-spectrum antibacterial agents), participates in disease resistance in bacteria and Brassica napus28. Nevertheless, mutations of genes involved in de novo fatty acid biosynthesis can easily lead to early developmental abnormalities or even death in plants, so the functions of these genes are difficult to reveal by obtaining their loss-of-function mutants even though their functions have been validated by biochemical studies26–28.

Anther and pollen development is a dynamic fine-tuning regulatory process that involves the timely formation of lipid metabolic products such as cutin/wax and sporopollenin precursors3,9. For example, the biosynthesis of the sporopollenin precursor is precisely regulated by a series of transcription factors (TFs)29,30. In Arabidopsis, a regulatory cascade (AtDYT1-AtTDF1-AtAMS-AtMS188-AtMS1) activates sporopollenin-related GMS genes, ensuring step-wise tapetal development and exine formation31. In rice, the corresponding cascade (OsUDT1-OsTDF1-OsTDR-OsMS188-OsPTC1) also regulates GMS genes encoding ER-localized lipid metabolic enzymes to form pollen exine32. Recently, a key TF ZmMS1/ZmLBD30 has been reported as a negative regulator of pollen exine thickness to form a ZmMS1-driven feedback repression loop (ZmbHLH51-ZmMYB84-ZmMS7-ZmMS1) which regulates GMS genes encoding ER-localized sporopollenin-related enzymes and transporters to ensure pollen exine formation in maize33. However, it is unclear whether this feedback repression loop regulates genes involved in de novo fatty acid biosynthesis in plant anther plastids.

In this study, we identified and characterized a key maize GMS gene, ZmENR1, encoding an anther tapetum plastid-localized enoyl-ACP reductase. Loss of ZmENR1 function results in early tapetal degeneration, smoother anther cuticle, and thinner pollen exine. ZmENR1 interacts with ZmHAD1 to facilitate de novo fatty acid biosynthesis in anther tapetal plastids. The ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex is regulated by the ZmMS1-mediated feedback repression loop to ensure anther cuticle and pollen exine formation by affecting the expression of cutin/wax- and sporopollenin-related genes. Evolution analysis showed that the ENR family members display conserved and diverse functions in maize, rice, and Arabidopsis. These findings reveal a player in the regulation network underlying anther and pollen development in maize, deepening our understanding of ENR function in plant development across different flowering plants.

Results

ZmENR1 encodes a tapetum-specific enoyl-ACP reductase required for male fertility in maize

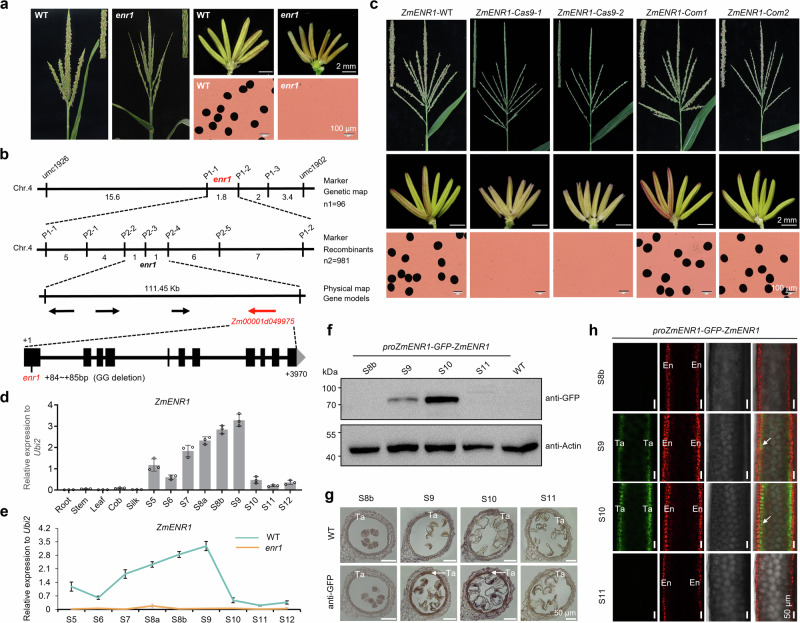

A complete male-sterility mutant enr1 was obtained by screening the mutant library of ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) of the maize inbred line Zheng58 in our laboratory. The enr1 mutant exhibited normal vegetative growth and female fertility, but fewer exerted smaller anthers compared with its wild type (WT), and failed to produce pollen grains upon maturity (Fig. 1a). Genetic analysis revealed that the male-sterility phenotype of the enr1 mutant is controlled by a recessive single gene (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Using a maize 60 K microarray analysis, the enr1 locus was primarily mapped to a 1.8-cM genetic region between markers P1−1 and P1-2 on chromosome 4 based on the maize B73 reference genome (RGV4.0) (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1b). Furthermore, it was narrowed down to a 111.45-kb interval between markers P2-2 and P2-4 containing four open reading frames (Fig. 1b). Among them, only Zm00001d049975 exhibited high expression levels during maize anther development based on RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data analysis of B73 anthers30,34 (Supplementary Fig. 1c). DNA sequencing showed that two guanines were deleted in the first exon of Zm00001d049975 in enr1 mutant compared with WT, resulting in a frame-shift mutation and premature stop codon (Fig. 1b). The requirement of Zm00001d049975 for male fertility was confirmed by the male-sterility phenotypes of its three knock-out lines generated using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1d, e), by genetic complementation of the enr1 mutant upon introducing Zm00001d049975 (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1e), and by the allelic tests between two CRISPR/Cas9 knock-out lines (ZmENR1-Cas9-1 and -2) and the enr1 mutant which exhibited a nearly 1:1 segregation ratio of male sterile to fertile F1 plants (Supplementary Fig. 1f). Zm00001d049975 was predicted to encode an enoyl-ACP reductase (hereafter termed ZmENR1) based on phylogenetic analysis and sequence alignment with other species (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). The 2-bp deletion of ZmENR1 is responsible for the male-sterility phenotype of the enr1 mutant.

Fig. 1. ZmENR1 is an anther tapetum-specific gene required for maize male fertility.

a Tassels, anthers, and pollen grains (stained by iodine-potassium iodide) of the WT and enr1 mutant. b Primary and fine mapping of enr1 locus on chromosome 4 and gene structure and DNA sequencing analysis of ZmENR1 in WT and enr1 mutant. c Functional complementation and gene-editing validation of the role of ZmENR1 in controlling male fertility in maize. The wild type (WT) is the genetic transformation line, maize hybrid Hi II. d ZmENR1 is expressed specifically in maize anthers based on quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis. Anther developmental stages are indicated as S5–S12. Data are the mean ± SD of the relative expression values normalized to the internal control ZmUbi2 from three biological replicates. e The transcription levels of ZmENR1 were significantly reduced in enr1 anthers compared to WT anthers as determined by qPCR analysis. Data are the mean ± SD (n = 3). f ZmENR1 expression in pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1 transgenic maize anthers during S8b–S11, as determined by western blot assays. Proteins from pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1 transgenic maize or WT anthers were detected using GFP- or actin-specific antibodies in western blot assays. g Immunohistochemical assay of ZmENR1-GFP signals in pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1 transgenic maize anthers during S8b–S11 using GFP antibody. h Confocal observation of the anther GFP signal of a pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1 transgenic maize line during S8b–S11. The merged channels of endothecium (En) chlorophyll autofluorescence (red) and GFP-ZmENR1 (green) are shown. In g and h, white arrows indicate positive signals. Ta, tapetum. In a, c, and f–h, each experiment was repeated three times independently. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Maize anther and pollen development can be divided into 14 stages (S1 to S14)1. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis revealed that ZmENR1 was highly expressed from anther developmental stage S7 to S9, with a peak at S9, while the expression abundance of ZmENR1 was not detected in enr1 anthers (Fig. 1d, e). Furthermore, western blotting and immunohistochemical assays showed that ZmENR1 was mainly accumulated in the anther tapetum at S9 and S10 (Fig. 1f, g). Moreover, GFP signals in maize pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1 anthers were also observed only in tapetal cells at S9 and S10 (Fig. 1h), in which chlorophyll autofluorescence served as an anther endothecium marker33,35. Collectively, ZmENR1 is expressed specifically in the tapetum and is required for male fertility in maize.

ZmENR1 controls pollen exine and anther cuticle development in maize

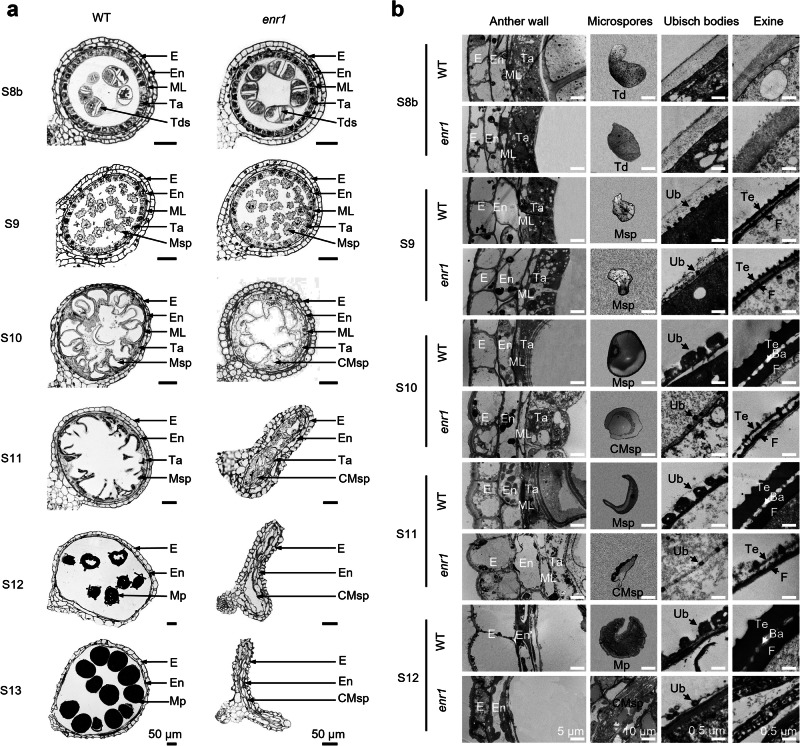

To investigate the cytological defects in the enr1 anther, we observed transverse sections of WT and enr1 anthers from S5 to S13. Based on the light microscopy of transverse sections, we observed that anther and microspore development were comparable between WT and enr1 anthers until S9 (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 3a). From S10 to S13, WT microspores underwent vacuolization, gradually accumulated starch, and eventually formed mature pollen grains. However, compared with WT, enr1 microspores could not be vacuolated normally, resulting in microspores with abnormal shape and size and abnormal tapetum degradation at S10 and S11. Eventually, enr1 microspores failed to accumulate starch and completely collapsed, with a withered locule at S12 and S13 (Fig. 2a). In addition, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observation showed that compared with the WT anther, the enr1 anther displayed similar phenotypes in terms of its outer and inner surfaces and microspores at S8b and S9, but no three-dimensional knitting cuticle, thinner outer and inner anther surfaces, smaller Ubisch bodies, and collapsed microspores from S10 to S13 (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Fig. 2. Transverse section and TEM observations of anther and pollen development in WT and enr1 mutant.

a Transverse section analysis of anthers in WT (Zheng 58) and enr1 from S8b to S13. b TEM analysis of anther wall, microspores, Ubisch bodies, and exine in WT and enr1 anthers from S8b to S12. In a and b, Ba baculua, CMsp collapsed microspore, E epidermis, En endothecium, F foot layer, ML middle layer, Mp mature pollen, Msp microspore, Ta tapetum, Td tetrad, Te tectum, Ub Ubisch body.

To gain more detailed insight into the abnormal anther and pollen development of the enr1 mutant, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observation was performed from S8b to S12 (Fig. 2b). Being consistent with the results of light microscopy and SEM observation as described above, no significant difference was observed between WT and enr1 anthers at S8b and S9. In WT, Ubisch bodies were formed from S9, tapetal cells started to degenerate from S10, and pollen exine was gradually formed and thickened from S9 to S12 (Fig. 2b). Compared with the WT anther, the enr1 anther exhibited an inflated and abnormal tapetum, unexpanded and collapsed microspores, smaller Ubisch bodies, and thinner pollen exine from S10 to S12 (Fig. 2b). Taken together, the enr1 mutation causes abnormal tapetal degeneration, smaller Ubisch bodies, a lack of three-dimensional knitting anther cuticle, and a thinner pollen exine, ultimately resulting in no pollen grain. Therefore, ZmENR1 controls pollen exine and anther cuticle development in maize.

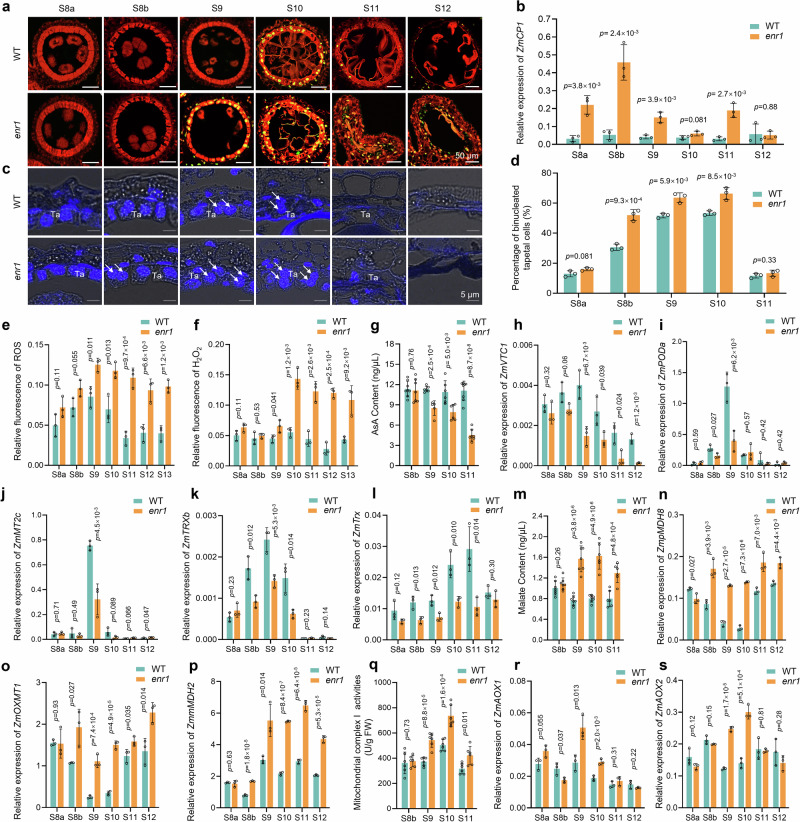

ZmENR1 ensures tapetal programmed cell death (PCD) by affecting ROS production in maize anthers

In plants, the degradation of the anther tapetum is a typical example of PCD, which is often assessed using a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay36,37. To investigate the detailed characteristic of enr1 tapetal PCD, we performed TUNEL assays in WT and enr1 anthers and observed that the TUNEL signals appeared earlier in enr1 anthers (at S9) than in WT (at S10) (Fig. 3a), in line with the upregulated expression of the maize PCD marker gene ZmCP1 (Cys protease 1)37,38 (Fig. 3b). In addition, proportions of binucleated cell positively correlate with tapetal PCD and degeneration33,39. Using 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining, we observed that the proportions of binucleated tapetal cells in enr1 anthers were significantly higher than those in WT anthers from S8b to S10 (Fig. 3c, d, Supplementary Fig. 4a). These findings indicated that loss of ZmENR1 function results in earlier tapetal PCD in maize anthers.

Fig. 3. ZmENR1 ensures tapetal PCD by affecting ROS production in maize anthers.

a Detection of tapetal PCD by TUNEL assay in WT and enr1 from S8a to S12. Each experiment was repeated three times independently. b Expression pattern changes of ZmCP1 in enr1 and WT from S8a to S12 by qPCR analysis. c Binucleated tapetal cell observation of WT and enr1 from S8a to S12 by DAPI staining. White arrows indicate the binucleated tapetal cells. Ta, tapetum. Three independent experiments were conducted. d Percentages of binucleated tapetal cells in WT and enr1 from S8a to S11. e, f Relative quantification of ROS (e) and H2O2 (f) levels in WT and enr1 from S8a to S13 by H2DCF–DA and ROSGreen H2O2 staining, respectively. g Changes in AsA content between WT and enr1 from S8b to S11. Data are the mean ± SD (n = 5–8). h Expression pattern changes of ZmVTC1 between WT and enr1 from S8a to S12. i–l Expression pattern changes in ZmPODa (i), ZmMT2c (j), ZmTRXb (k), and ZmTrx (l) in enr1 and WT from S8a to S12 by qPCR. m Changes of malate concentration between WT and enr1 from S8b to S11. Data are the mean ± SD (n = 6 or 7). n–p Expression pattern changes in ZmpMDH8 (n), ZmOXMT1 (o), and ZmmMDH2 (p) in enr1 and WT from S8a to S12 as determined by qPCR. q Changes in the Complex I activity between WT and enr1 from S8b to S11. Data are the mean ± SD (n = 6). r and s Expression pattern changes of ZmAOX1 (r) and ZmAOX2 (s) in enr1 and WT from S8a to S12 by qPCR. Data in b, d–f, h–l, n–p, r, and s are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Data in b and d–s, the significant levels of P determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis is critical for cell survival and growth during anther development, and excessive ROS accumulation causes PCD and damage to macromolecules, DNA, and proteins40. To investigate the reason for the abnormal tapetal PCD observed in enr1 anthers, we measured the contents of ROS and H2O2 in WT and enr1 anthers from S8a to S13 and observed that the ROS content was significantly higher in enr1 anthers than in WT from S9 to S13 (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 4b). Similarly, the H2O2 content in enr1 anthers was significantly higher than in WT anthers from S9to S13, although there was no significant difference at S8a and S8b (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Fig. 4c). Additionally, nitrotetrazolium blue chloride (NBT) staining showed that O2- was mainly produced in the anther tapetum and microspores, and its level in enr1 anthers was higher than in WT anthers from S8a to S10 (Supplementary Fig. 4d). L-ascorbic acid (AsA) plays an essential role in ROS homeostasis41. We measured the contents of AsA in WT and enr1 anthers from S8b to S11 and observed that the AsA content significantly decreased in enr1 anthers at S9 and S10 (Fig. 3g), in line with the down-regulated expression of the AsA biosynthesis pathway gene ZmVTC1 (VITAMIN C DEFECTIVE 1) (Fig. 3h)41. Furthermore, four genes (ZmPODa, ZmMT2c, ZmTRXb, and ZmTrx)33,35 involved in ROS scavenging were down-regulated in enr1 anthers at S9 and/or S10 (Fig. 3i–l), being largely consistent with the excessive ROS, H2O2, and O2- accumulation in enr1 anthers (Fig. 3e, f). Therefore, loss of ZmENR1 function results in excessive ROS and H2O2 accumulation in maize anthers, which explains the earlier tapetal PCD in enr1 anthers.

AtMOD1 also encodes an enoyl-ACP reductase27. A pathway of ROS production was clarified in Arabidopsis mod mutant: plastid NADH is oxidized by plastid-localized malate dehydrogenase (pMDH) to produce malate which is exported in exchange for oxaloacetate via Oxo-glutarate/malate transporter1 (OXMT1) and imported into the mitochondrion. Such malate would then be oxidized by mitochondrion-localized MDH (mMDH) to produce NADH which serves as a substrate for Complex I, ultimately leading to ROS production42,43 (Supplementary Fig. 4e). To investigate the reason for excessive ROS in enr1 anthers, we measured the malate content in WT and enr1 anthers from S8b to S11 and observed that the malate contents were significantly higher in enr1 anthers from S9 to S11 (Fig. 3m). Similarly, qPCR analysis showed that the transcript levels of ZmpMDH8, ZmpMDH13, ZmmMDH2, ZmmMDH3, and ZmOXMT1, the orthologs of AtpMDH, AtmMDH, and AtOXMT143, respectively, were significantly upregulated in enr1 anthers from S8b or S9 to S12 (Fig.3n–p, Supplementary Fig. 4f, g). We next analyzed the mitochondrial Complex I activities in enr1 mutant and observed that the Complex I activities were significantly enhanced in enr1 anthers at S9 and S10 (Fig.3q). Accumulation of signaling molecules such as ROS and H2O2 can strongly induce the expression of AOX genes which serve as mitochondrial stress markers and vital players in PCD and ROS regulation in plants44. We then examined the transcript levels of AOX (alternative oxidase) family genes using qPCR44. As expected, the expressions of ZmAOX1 and ZmAOX2 were upregulated in enr1 anthers at S9 and S10 (Fig.3r, s). These results indicate that the activated malate pathways cause excessive ROS accumulation in the mitochondria of enr1 anthers.

In addition, plasma membrane-localized NADPH oxidase encoded by AtRBOHD and AtRBOHF are involved in ROS burst45. To test whether the higher ROS levels in the enr1 mutant occur along with changes in ZmRBOH2 and ZmRBOH3 (homologous to AtRBOHD and AtRBOHF in Arabidopsis)45 transcription, we examined their transcript levels by qPCR in WT and enr1 (Supplementary Fig. 4h, i). qPCR results showed that the transcript levels of ZmRBOH2 and ZmRBOH3 were unchanged in enr1 mutants compared to WT (Supplementary Fig. 4h, i), suggesting that excessive ROS in enr1 mutant is not produced by plasma membrane-localized NADPH oxidase. Collectively, ZmENR1 ensures tapetal normal PCD mainly by affecting the malate-mediated pathways for ROS production in mitochondria of maize anthers.

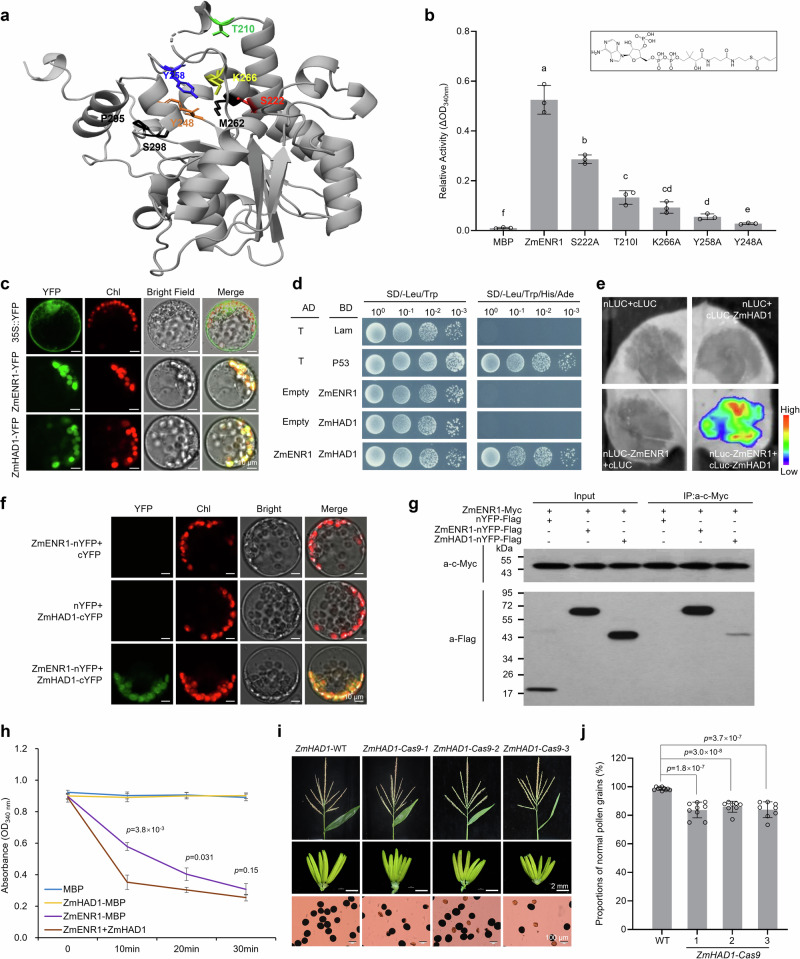

The interaction of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 enhances the catalytic activity of ZmENR1

ZmENR1 was annotated as a putative enoyl-ACP reductase (Supplementary Fig. 2). Homology modeling of ZmENR1 revealed that its putative three-dimensional structure has an active center containing three key amino acids (Y248, Y258, and K266) (Fig. 4a), implying that these three residues play crucial roles in the catalytic activity of ZmENR1. Moreover, compared with AtMOD127 and BnENR46, five conserved amino acids (T210, S222, M262, P295, and S298) were identified in ZmENR1 with potential catalytic activities (Fig. 4a). In addition, the ENR1 protein in plants can catalyze the conversion of crotonyl-CoA to butyryl-CoA in an NADH-dependent manner47. To test the catalytic activity of ZmENR1, we performed a series of enzyme activity experiments by purifying recombinant proteins of ZmENR1-MBP and its eight variants (T210I, S222A, Y248A, Y258A, M262A, K266A, P295A, and S298A) (Supplementary Fig. 5a) and by using crotonyl-CoA and NADH as primary substrates. As a result, the catalytic activities of three variants (M262A, P295A, and S298A) were comparable with that of ZmENR1 (Supplementary Fig. 5b), while those of five variants (T210I, S222A, Y248A, Y258A, and K266A) were significantly down-regulated (Fig. 4b), indicating that these five amino acid sites (TSYYK) in the enoyl-ACP reductase domain (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 2b) are essential for the enzyme activity of ZmENR1.

Fig. 4. Key amino acid sites of ZmENR1 and its interaction with ZmHAD1 to enhance the catalytic activity of ZmENR1.

a The simulated three-dimensional structure of ZmENR1 protein. The amino acids in generated variant proteins are shown in different colors. b The enzymatic activities of ZmENR1 protein are reduced in five single amino acid substitution variants compared with ZmENR1. MBP was used as a negative control. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences determined by one-way ANOVA at P < 0.05. c Both ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 proteins are localized in the plastids in maize protoplasts. A maize protoplast expressing empty 35S-YFP vector was used as a negative control. Chlorophyll autofluorescence (red) identifies the plastids. d Protein interaction between ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 was determined by Y2H assay. pGADT7-T and pGBKT7-lam were used as a negative control, while pGADT7-T and pGBKT7-P53 were used as a positive control. e LCI analysis shows that ZmENR1 interacted with ZmHAD1 in tobacco leaves. Luciferase activity is depicted with false color from low (blue) to high (red). nLUC, N-terminal half of the firefly luciferase; cLUC, C-terminal half of firefly luciferase. f BiFC analysis demonstrates the interaction between ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 in maize protoplasts. Protein name-n and -c indicate nYFP and cYFP fusions, respectively. g Co-IP assay shows the interaction between ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1. The nYFP-FLAG was used as a negative control. h Co-incubation of ZmHAD1 with ZmENR1 promoted the enzyme activity of ZmENR1. MBP was used as a negative control. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). i Tassels, anthers, and pollen grains (stained with 1% I2-KI) of WT and the three CRISPR/Cas9 knock-out lines at the mature pollen stage. j The reduced proportions of normal pollen grains compared with WT (Hi II) were observed in the three CRISPR/Cas9 knock-out lines at S13. Data are mean ± SD (n = 8–10). In c–g and i, each experiment was repeated three times independently. In b, h and j, the significant levels of P are determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Previous studies have shown that several monofunctional enzymes of type II FAS interact with each other48. ZmENR1 was located in the plastid (Fig. 4c) and is among the monofunctional enzymes of FAS (Supplementary Fig. 5d). To determine the interaction partners of ZmENR1, we used an immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry (IP-MS) assay to screen its interactors and obtained 56 proteins (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Among the identified putative ZmENR1 interactors, proteins such as ADP/ATP carrier protein 1 (ADT1) that facilitates ADP to synthesize ATP; Luminal-binding protein 3, which is likely involved in assembling multimeric protein complexes; and Photosystem II CP47 reaction center protein, which binds chlorophyll and supports light-induced photochemical processes, were not further investigated because their functions do not directly relate to de novo fatty acid biosynthesis. We selected the identified β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase (HAD1), a monofunctional FAS enzyme involved in the de novo fatty acid biosynthesis pathway (Supplementary Fig. 5d) for further investigation. Similar to ZmENR1, ZmHAD1 was also localized in the plastid (Fig. 4c). Next, we performed a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) (Fig. 4d), Luciferase complementary imaging (LCI) in tobacco leaf cells (Fig. 4e), bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) (Fig. 4f), and coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays (Fig. 4g) in maize protoplasts and observed that ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 could interact and form heterodimers. In addition, using the same methods, we observed that ZmENR1 itself could interact and form homodimers (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Fig. 5e–g).

To test whether this interaction of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 can enhance lipid metabolic efficiency catalyzed by ZmENR1, we measured the catalytic activity of the ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex and observed that ZmHAD1 could improve the catalytic efficiency of ZmENR1 in catalyzing the conversion of crotonyl-CoA and NADH to butyryl-CoA (Fig. 4h). To investigate whether ZmHAD1 also functions in maize male fertility, we generated three knock-out homozygous mutants of ZmHAD1 (ZmHAD1-Cas9-1, -2, and -3) via CRISPR/Cas9 technology. These three knock-out lines exhibited normal vegetative growth and female fertility but partial male sterility with ~18% of aborted pollen grains (Fig. 4i, j), suggesting that ZmHAD1 partially regulates maize male fertility. Additionally, transcription levels of ZmHAD1 did not change in enr1 anthers from S6 to S10 (Supplementary Fig. 5h), implying that the male sterility of enr1 is not dependent on the ZmHAD1. Taken together, the interaction of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 enhances the catalytic activity of ZmENR1 to facilitate lipid synthesis in plastids for anther and pollen development.

The ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex is regulated by ZmMS1-mediated feedback repression loop

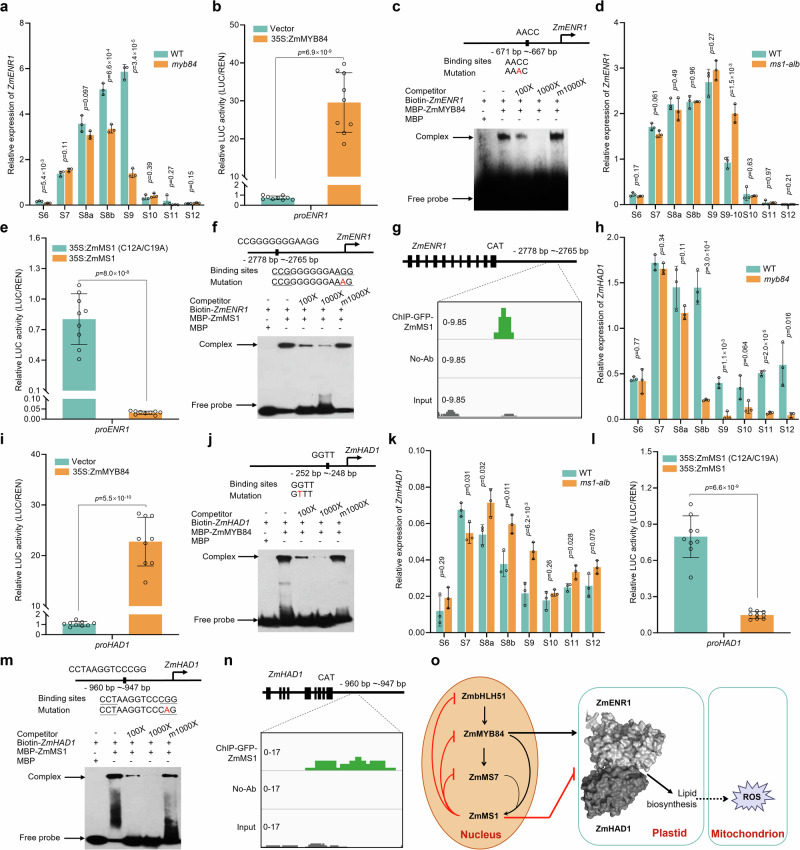

To understand how the transcriptions of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 are induced during anther development, we analyzed anther RNA-seq data of the maize inbred line B73 and observed that the expression patterns of four TF genes (ZmbHLH51, ZmMYB84, ZmMs7, and ZmMs1) overlapped with those of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 from S6 to S10 (Supplementary Fig. 6a). This result was confirmed by qPCR analysis (Supplementary Fig. 6b). All these four TFs are indispensable for male fertility in maize and form a ZmMS1-driven feedback repression loop (ZmbHLH51-ZmMYB84-ZmMS7-ZmMS1), which modulates the lipid metabolic genes to ensure tapetal development and pollen exine formation33. Thus, we hypothesize that the ZmMS1-driven feedback repression loop may regulate the expression of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1.

To test this hypothesis, we first analyzed transcription levels of ZmENR1 in bhlh51 by qPCR and observed that ZmENR1 was down-regulated in bhlh51 anthers from S8a to S10 (Supplementary Fig. 6c), but ZmbHLH51 did not activate the ZmENR1 promoter in a transient dual-luciferase reporter (TDLR) assay (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Next, qPCR analysis revealed that ZmENR1 transcript was significantly down-regulated in myb84 anthers at S8b and S9 (Fig. 5a). TDLR and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) showed that ZmMYB84 bound to and activated the promoter of ZmENR1 (Fig. 5b, c). However, both qPCR and TDLR assays revealed that ZmENR1 was not directly activated by ZmMS7 (Supplementary Fig. 6e, f). Because ZmENR1 was upregulated in ms1-alb compared with WT anthers from S9 to 10 (Fig. 5d), we inferred that ZmMS1 may suppress ZmENR1. The TDLR assay showed that ZmMS1 significantly suppressed the promoter activity of ZmENR1 (Fig. 5e). Moreover, EMSA and chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-seq) data analyses showed that ZmMS1 bound to the promoter of ZmENR1 (Fig. 5f, g), indicating that ZmMS1 directly inhibits ZmENR1 transcription.

Fig. 5. ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex is regulated by ZmMS1-mediated feedback repression loop.

a qPCR analysis of the transcription levels of ZmENR1 in myb84 anthers compared with WT anthers from S6 to S12. n = 3. b ZmENR1 promoter activity was activated by ZmMYB84 through transient dual-luciferase reporter (TDLR) assay in maize protoplasts. n = 9. c EMSA analysis of ZmMYB84 binding to the promoter of ZmENR1. d qPCR analysis of the transcription levels of ZmENR1 in ms1-alb anthers compared with WT anthers from S6 to S12. n = 3. e Transcriptional repression of the ZmENR1 gene by ZmMS1 through TDLR assay in maize protoplasts. n = 9. f EMSA analysis of ZmMS1 binding to the promoter of ZmENR1. g ChIP-seq peak showing the enrichment of ZmMS1 in the promoter region of ZmENR1. h qPCR analysis of the transcription levels of ZmHAD1 in myb84 anthers compared with WT anthers from S6 to S12. n = 3. i ZmHAD1 promoter activity was activated by ZmMYB84 through TDLR assay in maize protoplasts. n = 9. j EMSA analysis of ZmMYB84 binding to the promoter of ZmHAD1. k qPCR analysis of the transcription levels of ZmHAD1 in ms1-alb anthers compared with WT anthers from S6 to S12. n = 3. l Transcriptional repression of the ZmHAD1 gene by ZmMS1 through TDLR assay in maize protoplasts. n = 9. m EMSA analysis of ZmMS1 binding to the promoter of ZmHAD1. n ChIP-seq peak showing the enrichment of ZmMS1 in the promoter region of ZmHAD1. o The ZmMS1-driven feedback repression loop regulates the ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex which controls lipid biosynthesis and ROS accumulation. In c, f, j, m, each experiment was repeated three times independently. Data in a, b, d, e, h, i, k, and l are the mean ± SD. The significant levels of P determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Similarly, to test whether ZmHAD1 is directly regulated by a ZmMS1-driven feedback repression loop, we performed qPCR, TDLR, EMSA, and ChIP-seq analyses and observed that ZmbHLH51 and ZmMS7 did not activate the promoter of ZmHAD1 (Supplementary Fig. 6g–j), ZmMYB84 bound to and activated the promoter of ZmHAD1 (Fig. 5h–j), and ZmMS1 inhibited ZmHAD1 transcription (Fig. 5k–n). Furthermore, transcription levels of ZmbHLH51, ZmMYB84, ZmMs7, and ZmMs1 were comparable between WT and enr1 anthers from S6 to S12 (Supplementary Fig. 6k–n), indicating that the enr1 mutation has no impact on the expression of these four TF genes. Collectively, the ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex is regulated by the ZmMS1-mediated feedback repression loop to promote lipid biosynthesis and control ROS production (Fig. 5o).

A working model of the ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex to ensure tapetal cell PCD, pollen exine, and anther cuticle development

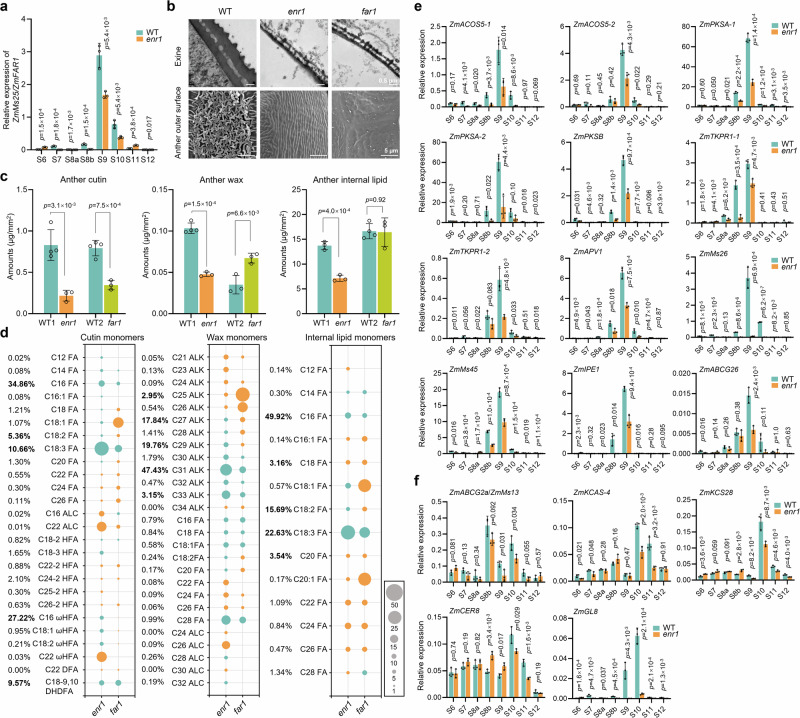

Compared with a large number of GMS genes encoding proteins in ER, fewer GMS genes encoding proteins in plastids have been reported in plants3. ZmFAR1 is the only GMS gene reported to be located in maize plastids, and its encoded protein is involved in fatty acid modification after de novo fatty acid biosynthesis11 (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Because ZmFAR1 and ZmENR1 have the same location and are involved in lipid metabolism in plastids, a correlation likely exists between them. To test this hypothesis, qPCR analysis was performed and showed that ZmFAR1 was down-regulated in enr1 anthers at S9 and S10 (Fig. 6a), implying that the expression of ZmFAR1 is dependent on ZmENR1. To determine whether ZmENR1 and ZmFAR1 have comparable effects on the formation of the anther cuticle and pollen exine, we performed TEM and SEM observations of WT, enr1, and far1 anthers at S12, and observed that the pollen exine of enr1 and far1 was comparable and obviously thinner than that of WT (Fig. 6b). Both mutant anthers exhibited a defective anther cuticle compared with WT, while the anther cuticle of far1 was smoother than that of enr1 (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6. Comparison of lipid contents between enr1 and far1 anthers and the role of ZmENR1 in affecting expression of sporopollenin- and cutin/wax-related genes.

a Expression pattern changes of ZmMs25/ZmFAR1 between WT and enr1 anthers from S6 to S12 by qPCR analysis. n = 3. b TEM observation of pollen exine and SEM observation of anther outer surface in WT, enr1, and far1 mutants at S12. c Comparison of anther cutin, wax, and internal lipid amounts in WT, enr1, and far1 mutants at S13. The turquoise columns represent the amounts of cutin, wax, and internal lipid monomers in wild-type (WT1 and WT2) anthers. The orange and green columns correspond to these components in enr1 and far1, respectively. n = 3 or 4. d Comparison of cutin, wax, and internal lipid monomers per unit surface area in WT, enr1, and far1 anthers at S13. The orange and turquoise circles represent the increase and decrease of the cutin, wax, and internal lipid monomers, respectively. The size of the circles represents the change magnitude of the increase or decrease. e Expression pattern changes of 12 sporopollenin-related genes between WT and enr1 anthers from S6 to S12 by qPCR analysis. n = 3. f Expression pattern changes of five cutin- and wax-related genes between WT and enr1 from S6 to S12 by qPCR analysis. n = 3. Data in a, c, e, and f are mean ± SD. The significant levels of P determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To investigate the reason for this different phenotype, the contents of cutin, wax, and internal lipids as well as their monomers in WT, enr1, and far1 anthers at S13 were analyzed by gaschromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). As a result, the cutin contents in enr1 and far1 anthers were significantly lower than those in WT, while the wax content significantly decreased in enr1 but increased in far1 compared with WT. The internal lipid content was significantly lower in enr1 but comparable in far1 compared with WT (Fig. 6c). These differences were primarily due to alterations in the amounts of monomers (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Fig. 7). Specifically, the levels of the main monomers of cutin (C16 FA, C18:3 FA, and C18-9,10 DHDFA, accounting for 55.09%) significantly decreased in enr1 and far1 anthers. The levels of the main monomers of wax (C27 ALK, C28 ALK, and C29 ALK, accounting for 39.01%) significantly decreased in enr1 but increased in far1 anthers (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Data 1). Therefore, ZmENR1 and ZmFAR1 have different effects on lipid metabolism in anthers, although both are lipid-metabolic GMS genes encoding proteins localized in plastids.

The abnormally thin pollen exine and smooth anther cuticle in the enr1 mutant (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 3b) imply that sporopollenin and cutin/wax metabolic pathways may be disrupted in enr1 anthers. To confirm this, transcription levels of 12 sporopollenin-related genes (ZmACOS5-1/-2, ZmPKSB, ZmPKSA-1/-2, ZmTKPR1-1/-2, ZmMs26, ZmMs45, ZmIPE1, ZmAPV1, and ZmABCG26) and five cutin/wax-related genes (ZmABCG2a/ZmMs13, ZmKCAS-4, ZmKCS28, ZmCER8, and ZmGL8) were compared between WT and enr1 anthers from S6 to S12 by qPCR analysis. As a result, these 12 sporopollenin-related genes were significantly down-regulated in enr1 anthers at S9 (Fig. 6e), and these five cutin/wax-related genes were significantly down-regulated in enr1 anthers at S10 (Fig. 6f), suggesting that ZmENR1 is required for anther cuticle and pollen exine formation through affecting transcription of sporopollenin- and cutin/wax-related genes.

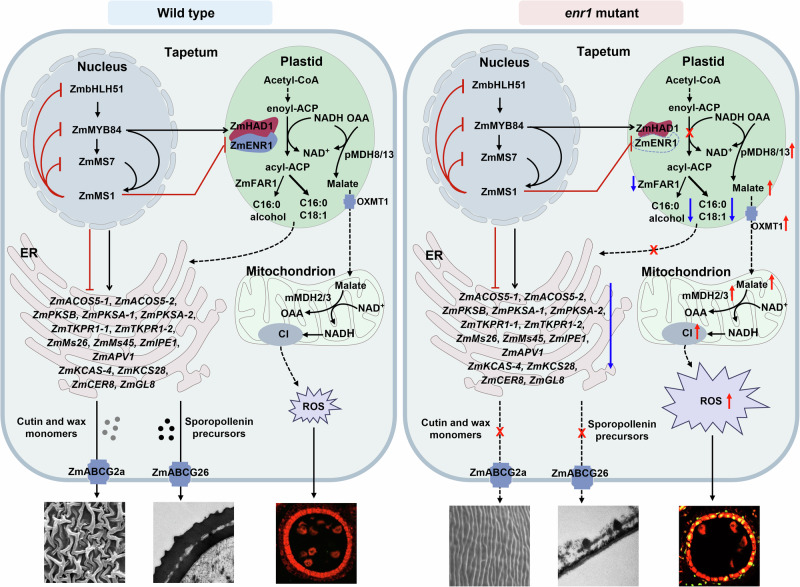

A recent report showed that a ZmMS1-driven feedback repression loop (ZmbHLH51-ZmMYB84-ZmMS7-ZmMS1) modulates a series of ER-localized lipid metabolic enzymes to ensure pollen exine development33. Taken together with these results obtained here and reported previously, a working model was proposed to elucidate the molecular mechanism of ZmENR1 mediating maize anther and pollen development (Fig. 7). In WT, the ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex is regulated by the ZmMS1-mediated feedback repression loop to promote de novo fatty acid biosynthesis and ultimately lead to the production of C16:0 (palmitic acid), C18:1 (oleic acid), and C16:0 alcohol in tapetal plastids. The derived C16:0, C18:1, and C16:0 alcohol are exported from the plastid to ER. Cutin/wax and sporopollenin precursors are synthesized and assembled by ER-localized lipid metabolic enzymes regulated by the ZmMS1-mediated feedback repression loop and then transported by ZmABCG26 and ZmABCG2a to form the pollen exine and anther cuticle, respectively. Plastid NADH is consumed by ZmENR1 to produce less malate, accumulate less ROS in the mitochondrion, and maintain normal PCD in anther tapetum. However, the loss of ZmENR1 function blocks de novo fatty acid biosynthesis and causes a decrease in the rates of C16:0, C18:1, and C16:0 alcohol synthesis in plastids, and fewer lipid raw materials flow to ER for lipid synthesis. Meanwhile, genes encoding plastid- and mitochondrion-localized ROS production-related proteins, malate content, and Complex I activities are significantly upregulated to accumulate excessive ROS, resulting in earlier tapetal cell PCD in enr1 anthers. Moreover, expression levels of cutin/wax-related genes are reduced in enr1 anthers, ultimately resulting in a greatly thin pollen exine and anther cuticle.

Fig. 7. A working model of ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex to ensure tapetal cell PCD, anther cuticle development, and pollen exine formation in maize.

In WT, the ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex is regulated by the ZmMS1-mediated feedback repression loop to promote de novo fatty acid biosynthesis and ultimately lead to the production of C16:0 (palmitic acid), C18:1 (oleic acid), and C16:0 alcohol in the tapetal plastid. The derived C16:0, C18:1, and C16:0 alcohol are exported from the plastid to ER. Cutin/wax and sporopollenin precursors are synthesized and assembled by ER-localized lipid metabolic enzymes regulated by the ZmMS1-mediated feedback repression loop and then transported by ZmABCG26 and ZmABCG2a to form pollen exine and anther cuticle, respectively. Plastid NADH is consumed by ZmENR1 to produce fewer malate, accumulate less ROS in the mitochondrion, and maintain normal PCD in anther tapetum. However, loss-of-function of ZmENR1 blocks de novo fatty acid biosynthesis and causes the decrease of the levels of C16:0, C18:1, and C16:0 alcohol synthesis in plastids, and fewer lipid raw materials flow to ER for lipid synthesis. Meanwhile, genes encoding plastid- and mitochondrion-localized ROS production-related proteins, malate content, and Complex I (CI) activities are significantly upregulated to accumulate excessive ROS, resulting in earlier tapetal cell PCD in enr1 anthers. Moreover, expression levels of cutin/wax-related genes are reduced in enr1 anthers, ultimately resulting in greatly thin pollen exine and anther cuticle.

Evolution and function of ZmENRs and their orthologs in flowering plants

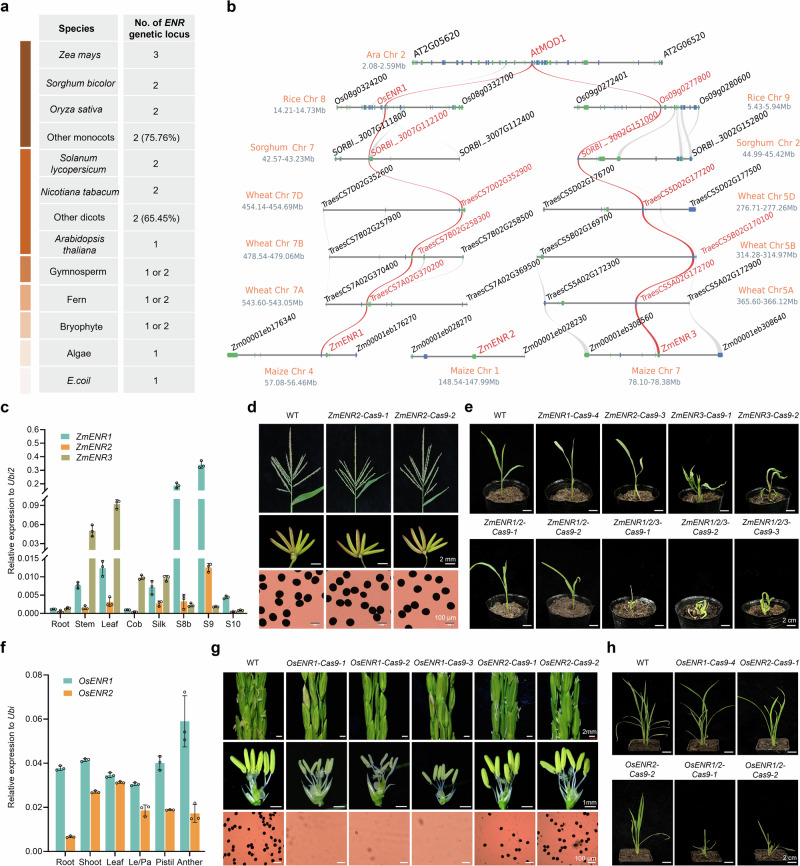

To investigate the evolutionary relationship of ENR family members, we generated a maximum likelihood tree of 258 ENR homologous genes from 127 species (Supplementary Fig. 8), which were all nuclear genes encoding plastid-localized ENR proteins, except for E. coli ENR localized in the cytoplasm. This high-resolution phylogenetic tree revealed that ENRs are divided into eight distinct classes from lower to higher plants and in bacteria, including E.coli, algae, bryophytes, ferns, gymnosperms, early angiosperms, dicots (angiosperms), and monocots (angiosperms) (Supplementary Fig. 8). Notably, only one ENR gene was identified in the E.coli and algae genomes (Fig. 8a, Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Data 2), while one or two copies appeared in bryophytes, ferns, and gymnosperms. In angiosperms, 65.45% of dicots and 75.76% of monocots had two ENR loci (Fig. 8a, Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Data 2). Distinctively, Arabidopsis (eudicot) only has one ENR gene, whereas maize (monocot) has three ENRs (Fig. 8a, Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Data 2). These results indicate that the duplication and loss of ENR genes occur during plant evolution.

Fig. 8. Evolution and function of ZmENR1 and its orthologs in flowering plants.

a Gene copy numbers of ENR orthologs from lower plants to higher plants. b Microsynteny analysis of ZmENR1 loci and their orthologs among four monocots and one eudicot. Genes shown in red indicate ZmENR1, paralogues, and orthologs. Genes flanking ZmENR1 and their orthologs are shown in black. At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Os, Oryza sativa; Sb, Sorghum bicolor; Ta, Triticum aestivum; Zm, Zea mays. c Expression patterns of ZmENR1, ZmENR2, and ZmENR3 genes in various tissues based on qPCR analysis. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). d Tassels, anthers, and pollen grains (stained with 1% I2-KI) of WT and two CRISPR/Cas9 knock-out lines of ZmENR2 (ZmENR2-Cas9-1 and -2) in mature pollen phase. e Phenotypic analysis of WT, the single knock-out lines (ZmENR1-Cas9-4 and ZmENR2-Cas9-3), the two double-mutant lines (ZmENR1/2-Cas9-1 and 2), and the three triple-mutant lines (ZmENR1/2/3-Cas9-1, 2, and 3) in T0 seedling phase. f Expression patterns of OsENR1 and OsENR2 genes in various tissues based on qPCR analysis. Le, lemma; Pa, palea. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). g Spikelets, anthers, and pollen grains (stained by I2-KI) of WT (Nipponbare), three CRISPR/Cas9 knock-out lines of OsENR1 (OsENR1-Cas9-1, -2, and -3), and two CRISPR/Cas9 knock-out lines of OsENR2 (OsENR2-Cas9-1 and -2) in mature pollen phase. h Phenotypic analysis of WT, the single knock-out lines (OsENR1-Cas9-4, OsENR2-Cas9-1 and 2) and the two double-mutant lines (OsENR1/2-Cas9-1 and 2) in T0 seedling phase. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To investigate genome collinearity of the ZmENR1, 2, and 3 loci and their orthologs, we performed microsynteny analysis among four monocots and one eudicot and observed that ZmENR1 and ZmENR3, rather than ZmENR2, exhibit collinearity with their orthologs in monocots such as rice, sorghum, and wheat. All these orthologs exhibit synteny with the single locus AtMOD1 in Arabidopsis (Fig. 8b). This result implies that ZmENR2 is a newly occurring site during maize evolution. Using qPCR analysis, we observed that the ZmENR2 transcript was detected in anthers at S8b and S9, while the ZmENR3 transcript was mainly detected in stem, leaf, cob, and silk (Fig. 8c). Furthermore, ZmENR2 and ZmENR3 are located in plastids (Supplementary Fig. 10a). To investigate whether ZmENR2 controls male fertility as ZmENR1 (Supplementary Fig. 10b), we generated two mutants of ZmENR2 (ZmENR2-Cas9-1 and -2) and observed that both mutants exhibited normal vegetative growth and male fertility (Fig. 8d, Supplementary Fig. 10c, d). We further generated two single knock-out lines (ZmENR3-Cas9-1 and -2), two double knock-out lines (ZmENR1/2-Cas9-1 and -2), and three triple-mutant lines (ZmENR1/2/3-Cas9-1, -2, and -3) (Supplementary Fig. 10e–g). Both double mutants exhibited normal vegetative growth during the T0 seedling phase, being largely consistent with the single knock-out T0 lines of ZmENR1 (ZmENR1-Cas9-4) and ZmENR2 (ZmENR2-Cas9-3) (Fig. 8e, Supplementary Fig. 10h), whereas all the zmenr3 and three triple-gene mutants displayed multiple morphological defects in T0 seedling phase, showing curly leaves and dwarfism (Fig. 8e). Subsequently, these aberrant zmenr3 and triple mutants progressively die. These results indicate that ZmENR3 is indispensable in maize vegetative developmental processes.

To investigate whether the function of ENRs is conserved in regulating flowering plant development, we first used qPCR to examine the transcript levels of OsENR1 and OsENR2. OsENR1 was highly expressed in all detected tissues, especially in anther, while high transcript levels of OsENR2 were detected in shoots and leaves (Fig. 8f). Furthermore, four single knock-out lines of OsENR1 (OsENR1-Cas9-1, -2, -3, and -4), two single knock-out lines of OsENR2 (OsENR2-Cas9-1 and -2) and two double knock-out lines (OsENR1/2-Cas9-1 and -2) were generated in rice via the CRISPR/Cas9 technology (Fig. 8g, h, Supplementary Fig. 10i, j). All osenr1 mutants exhibited normal vegetative growth and female fertility but complete male sterility with smaller anthers and no visible pollen grains (Fig. 8g, Supplementary Fig. 10k). Both osenr2 mutants exhibited normal vegetative growth and male fertility (Fig. 8g, Supplementary Fig. 10k). Notably, two double mutant lines (OsENR1/2-Cas9-1 and -2) exhibited multiple morphological defects in T0 seedling phase, including curly leaves, dwarfism, and gradual death (Fig. 8h), similar to the triple-mutants of ZmENR1/2/3. AtMOD1, as the orthologous gene of maize ZmENRs and rice OsENRs, has leaky mutants exhibiting multiple abnormal phenotypes such as curly leaves, distorted siliques, premature senescence of primary inflorescences, and dwarfism27, which are comparable with zmenr1/2/3 and osenr1/2 but different from zmenr1 or osenr1 single mutants. Therefore, ENR family members exhibit conserved functions in different plant species during evolution, and the duplicated members in rice and maize play redundant roles in controlling vegetative growth. However, being different from the solo AtMOD1, which has to control vegetative and reproductive development in Arabidopsis, only ZmENR1 and OsENR1 are essential for controlling male fertility in maize and rice, respectively.

Discussion

Anther cuticle and pollen exine development are controlled by genetic and physicochemical processes4,9. Lipid-metabolic GMS genes and their regulated TFs synthesize cutin/wax and sporopollenin precursors through the cooperation of various subcellular organelles in the plant anther tapetum, including de novo fatty acid biosynthesis in plastids and fatty acid elongation and modification in ER3. Nevertheless, little is known about GMS genes involved in de novo fatty acid biosynthesis in plastids relative to the fact that many GMS genes have reported function in ER. A possible reason is that de novo fatty acid biosynthesis is essential to all living organisms, and the loss of FAS gene function in the de novo biosynthetic pathway may thus cause the death of plants27. Here, we report that the key GMS gene ZmENR1, encoding an anther tapetum plastid-localized enoyl-ACP reductase, positively controls anther cuticle and pollen exine development and is required for proper ROS and H2O2 production in mitochondria and timely degradation of tapetal cells in maize (Figs. 1–3). In the context of anther and pollen development, the ZmMS1-mediated feedback repression loop mainly regulates GMS gene function in ER with peak expression at S933. We further observed that the plastid-localized ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex is regulated by the ZmMS1-mediated feedback repression loop to facilitate de novo fatty acid biosynthesis in the anther (Fig. 5). Twelve sporopollenin-related genes and five cutin/wax-related genes, whose encoding proteins are localized in ER, are down-regulated in enr1 anthers mainly at S9 and S10, respectively (Fig. 6). Collectively, our findings reveal that the ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex localized in the tapetal plastid regulated by TFs localized in the tapetal nucleus controls anther cuticle and pollen exine development by regulating ROS homeostasis in tapetal mitochondria and lipid metabolism in tapetal ER (Fig. 7), providing insights into the genetic regulation network underlying maize male reproduction through the cross-talk among various subcellular organelles in the anther tapetum.

PCD is a fundamental process of the plant life cycle. Timely PCD and degeneration of anther tapetum provide nutrients for the development of pollen wall. Premature or delayed anther tapetal PCD generally results in male sterility36,37. In the field of plant male reproduction, anther tapetal PCD has attracted immense research interest from scientists. Many GMS genes affecting PCD in anther tapetum have been identified in plants, including OsTDF132, OsUGE136, ZmMs133, and ZmMs3335. However, although these genes affect tapetal PCD by changing ROS levels in anthers, the locations where ROS are produced in the anther tapetum have not yet been revealed. Plastid-localized ZmENR1 can promote tapetal PCD by regulating the level of ROS production in mitochondria, revolutionizing our understanding of the mechanism of anther tapetal PCD. This advance provided insights into the molecular mechanism of tapetal PCD in plants.

Eight conserved amino acids that may endow ZmENR1 with the conserved enoyl-ACP reductase activity are identified in the functional domain of ZmENR1, of which five (TSYYK) are indispensable for ZmENR1 activity (Fig. 4). Meanwhile, ZmENR1 can form homodimers by itself and heterodimers with ZmHAD1 (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 5). Multienzyme association results in higher metabolic efficiency49,50, implying that the interaction of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 may enhance the efficiency of de novo fatty acid biosynthesis. In maize, the apparent thickening and rapid formation of the anther cuticle and pollen exine occur at the anther developmental stage S10, which typically takes approximately two days51. Previous studies also demonstrated that exine formation can be completed rapidly, even within a few hours9,52, which requires the rapid biosynthesis of lipid metabolism in plastids and the ER. We observed that the ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex enhances the accumulation of fatty acyl-CoAs more efficiently than ZmENR1 alone (Fig. 4), which may lead to more lipid materials rapidly flowing from plastids to the ER, rapidly synthesizing cutin/wax and sporopollenin precursors in the ER. Thus, the ZmENR1/ZmHAD1 complex is essential for anther cuticle and pollen exine formation. However, ZmHAD1 knock-out lines exhibit partial male sterility with aborted pollen grains (Fig. 4), implying that the function redundancy of ZmHAD1 may exist in maize or because ZmENR1 cannot perform its full activity in the absence of ZmHAD1. As expected, a paralogous gene (ZmHAD2, Zm00001d049351) of ZmHAD1 is observed in the maize B73 reference genome (RGV4.0). Further studies are required to elucidate the role of ZmHAD2 on anther and pollen development in the future.

ZmFAR111 is the identified GMS gene involved in fatty acid modification after de novo fatty acid biosynthesis, encoding an enzyme that has the same location as ZmENR1, and both of them are involved in lipid metabolism in maize. Their mutants exhibit similarly abnormal pollen exine phenotypes but distinct defective anther cuticle phenotypes (Fig. 6). The reason for this phenotypic difference is that ZmENR1 and ZmFAR1 function at different steps of the lipid metabolism pathway and synthesize different products. ZmENR1 is located upstream of ZmFAR1 in the lipid metabolism pathway in plastids and is essential for all fatty acid-based metabolites, while ZmFAR1 is only required for fatty alcohols in select biomolecules. The lipidomic analysis showed that mutations of both genes lead to the accumulation of different intermediate lipid products. For example, the levels of C16 ωHFA, C27 ALK, C29 ALK, and C18:2 FA significantly decreased in enr1 but increased in far1 anthers (Fig. 6). These lipid compositions are the common substrates for the biosynthesis of anther cutin/wax monomers and sporopollenin precursors53. In addition, partial functional redundancy may exist between ZmENR1 and ZmENR2 as ZmENR2 exhibits high expression levels at S9 similar to ZmENR1 (Fig. 8), in which ZmENR2 may provide the partial reductase activity and reduce the impact of enr1 mutation on anther cuticle formation. Although four paralogous genes of ZmFAR1 exist in maize plastids, only ZmFAR1 exhibits high expression levels at S911. The positions of ZmENR1 and ZmFAR1 in the lipid metabolism pathway and their paralog redundancy profiles make them play different roles in anther cuticle formation. Our findings reveal that the genes involved in the lipid metabolism pathway in plastids have discrepant effects on the formation of the anther cuticle. However, the detailed molecular mechanisms of ZmENR1 and ZmFAR1 in regulating anther cuticle formation via lipid metabolism await further studies.

Evolvability and polyploidization are parts of the evolutionary history of all natural plant species, which has tended to promote gene duplication54. One ENR gene exists in E. coli and algae, while more than one copy appears during the evolution from most aquatic plants to terrestrial plants (Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Data 2), suggesting that the number of ENR genes (nuclear genes encoding plastid-localized ENR proteins) increases with the evolution of plants. Plant evolution leads to polyploidization and gene duplication, subsequently tending to diploidization, which explains why the vast majority of higher plants (accounting for 63.2%) contain two ENR genes. However, because of a harsh environment likely caused by a meteor hit during the Cretaceous-Palaeogene, gene duplication events are particularly rich54, by which a few higher plants (accounting for 14.4%), such as maize, duplicate multiple ENR genes to adapt to extreme-changing environments of the planet (Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Data 2). These findings suggest that the number of ENR genes in plant species may positively correlate with the severity of the environment surrounding plants. Gene duplication relaxes the selection on duplicated paralogous genes, causing the gene loss of these redundant genes54. Thus, some species (accounting for 22.4%), such as Arabidopsis, only retain a single ENR gene (Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. 9), which is probably due to gene loss upon gene duplication. During plant evolution, the increased numbers of genes are expected to promote the occurrence of new morphotypes for natural diversifying selection and adaptive radiation55,56. Additionally, three ZmENRs and two OsENRs exhibited tissue-specific expression patterns and corresponded to different biological functions, indicating that the ENR duplication contributes to gene functional differentiation, thereby promoting precise regulation of plant growth and development processes. ZmENR1 and OsENR1 are only required for anther and pollen development, suggesting that the ENR duplication allows for better regulation of lipid metabolism in the reproductive tissues of these plant species.

Here, ZmENR1 and OsENR1 regulate male fertility but their mutations have no impact on vegetative growth and female fertility (Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. 10), while the Arabidopsis MOD1 mutant (the AtENR missense mutant) exhibits multiple abnormal phenotypes in vegetative and reproductive development27, and a null mutation would likely be lethal, implying that ENR1 is a newly evolved gene in higher plants such as maize and rice to specifically regulate male fertility. Redundant gene copies may shield any one paralog and/or ortholog from its mutation-mediated adverse defects and preserve its original function54. Multiple morphological defects of the triple-mutant lines (ZmENR1/2/3-Cas9-1, -2, and -3) and the double mutants (OsENR1/2-Cas9-1 and -2) also reflect the original function of ENR in regulating vegetative growth and female development as Arabidopsis MOD1. Our results on the functions of ENR members in maize and rice further indicate that fatty acids are essential for all organisms, and simultaneous mutations in all ENR members involved in de novo fatty acids biosynthesis will be lethal. Overall, our results reveal that the key genes involved in de novo fatty acid synthesis in maize and rice are essential for male reproduction and vegetative growth, providing insights into the lipid metabolism regulation in male reproductive and vegetative organs of different flowering plants.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The maize inbred line B73, the parental lines (Hi A and B) of hybrid Hi II, and mutants ms1-alb and ms7-6007 and their WT sibling were originally obtained from the Maize Genetics Cooperation Stock Center (http://maizecoop.cropsci.uiuc.edu). The maize inbred lines Zheng 58 and Xiang 249 used in this study are maintained by the Research Institute of Biology and Agriculture, University of Science and Technology Beijing. The maize mutants bhlh51 and myb84 were generated previously and maintained in our laboratory30,33,57. Seeds of the rice cultivar Nipponbare were obtained from WIMIbio (http://www.wimibio.com/).

Maize hybrid Hi II, inbred Xiang 249, and rice (Nipponbare) were used to produce transgenic lines. For maize transformation, the constructs were transfected into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105. Ears harvested 10–12 days after pollination were sterilized in 50% commercial bleach containing 5.25% sodium hypochlorite for 20 min and washed thrice with sterile water. Immature zygotic embryos, around 1.8 mm (1.5–2.0 mm) in size, were isolated from maize kernels and placed in 1 mL of the liquid medium (about 100 embryos in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube), followed by 3–4 washes with the same medium. Then, 1 mL of Agrobacterium suspension was added to the 1.5 mL tube, and inoculation was performed for 10 min before embryos were transferred onto the cocultivation medium for 3 days. After cocultivation, embryos were sequentially transferred to the resting medium, selective medium, and regeneration medium to generate regenerated plantlets with roots and shoots. Finally, plantlets were transferred to the greenhouse. Rice transformation was performed by Weimi Bio-Tech. Transgenic maize lines were produced in this study including ZmENR1-Cas9-1 to ZmENR1-Cas9-4, pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1 (#1, #2, and #3), ZmENR1-Com-1 (pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1#1/enr1) to ZmENR1-Com-3 (pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1#3/enr1), ZmHAD1-Cas9-1 to ZmHAD1-Cas9-3, ZmENR2-Cas9-1 and ZmENR2-Cas9-2, ZmENR3-Cas9-1 and ZmENR3-Cas9-2, ZmENR1/2-Cas9-1 and ZmENR1/2-Cas9-2, and ZmENR1/2/3-Cas9-1 to ZmENR1/2/3-Cas9-3. The generated transgenic rice lines generated in this study were OsENR1-Cas9-1 to OsENR1-Cas9-4, OsENR2-Cas9-1 and OsENR2-Cas9-2, and OsENR1/2-Cas9-1 and OsENR1/2-Cas9-2.

The T0 transgenic maize and rice plants were grown in a greenhouse under long-day conditions (16 h / 8 h (day/night) at 26 °C / 22 °C). Other maize and rice plants were grown in the experimental stations of the University of Science and Technology Beijing in Beijing (40°30′N, 116°37′E) and in Sanya, Hainan province (18°37′N, 109°21′E) under natural conditions.

Phenotype observation

Morphological characteristics of maize and rice whole plants and maize tassels were photographed using a Canon EOS 700D digital camera (Canon, Tokyo, Japan). A Nikon SMZ1500 stereomicroscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to image anthers. Images of the pollen grains stained with 1% I2–KI solution were captured using a BX-53F microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Genetic analysis and map-based cloning

For genetic analysis, the enr1 mutant was crossed to the maize inbred line B73 to obtain F1 hybrid seeds, and then an F2 mapping population was generated by self-crossing F1 individuals. The genetic analysis, primary mapping, and fine mapping of the enr1 locus were performed according to the method described previously57,58. The enr1 locus was narrowed down to the markers P2-2 and P2-4. Four genes are located within this region. The putative candidate gene ZmENR1 was located by comparing DNA sequence differences of four genes between WT and the enr1 mutant. All primers used for gene mapping are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

To identify orthologs and paralogs of ZmENR1, the protein sequence of ZmENR1 was used to perform BLAST searches from the databases Ensembl Plants (https://plants.ensembl.org/index.html), National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Phytozome (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html), and maize genome (https://www.maizegdb.org/). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA 11 with 1,000 bootstraps59. Multiple sequence alignments and the analysis of the conserved domain in ENRs were performed using the CLUSTALX program and SMART, respectively.

Plasmid construction and plant transformation

For the mutagenesis of ZmENR1, a CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid was constructed by introducing two guide RNAs with 19-bp fragments in the ZmENR1 coding region (5’- GCTGCTGGTGTGCAGATGG -3’ and 5’- TCAGTCCTAGAAACCCGTG-3’) into pBUE41160. The CRISPR/Cas9 knock-out lines of ZmENR2 (Zm00001d030591), ZmENR3 (Zm00001d019926), ZmENR1/2, ZmENR1/2/3, and ZmHAD1 (Zm00001d010180) were generated using the same method. Instead of pBUE411, the plasmid pHUE411 was used to generate the OsENR1 (Os08g0327400) and OsENR2 (Os09g0277800) knock-out lines. For functional complementation, a 4827-bp fragment, including a 3000 bp upstream promoter, a 1110 bp coding sequence of ZmENR1, and a 717 bp GFP coding sequence, was cloned into the binary vector pBCXUN by homologous recombination, resulting in the construct pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1. The generated constructs were transformed into maize or rice according to the previous procedures34. The presence of transgenes was examined by genomic PCR using Bar gene-specific primers. Primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

The various maize tissues, including root, stem, leaf, cob, silk, and anthers at different stages, were ground into fine powders in liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). The total RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase I (abm, Canada) to remove DNA contamination. Two micrograms of total RNA were used to synthesize cDNA using 5X All-In-One RT MasterMix (abm, Canada). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on a QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR system (ABI, USA) using a TB GreenTM Premix EX TagTM (TakaRa, Japan). ZmUbi2 (Zm00001d05383) was used as the reference gene. Primers used for quantitative real-time PCR are listed in Supplementary Data 3. Each sample had three biological replicates, each with three technical replicates. Data were calculated with the 2-ΔΔCt method, and quantitative results were presented as means ± SD.

Western blotting and immunohistochemical assay

Fresh maize anthers of WT and the pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1 transgenic maize line from S8b to S11 were ground in liquid nitrogen and dissolved in RIPA buffers to extract total proteins. Each RIPA buffer contained 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.8), 2 mM EDTA, a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.5% NP-40. Total proteins were then collected from the RIPA buffer and separated by SDS–PAGE. The mouse anti-GFP antibody (diluted 1:1000 in non-fat milk) and the goat-anti-mouse conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (diluted 1:10000) were respectively used as the primary antibody and secondary antibody to detect ZmENR1-GFP. The protein of the WT anther was used as a negative control. The loading control, which is the actin protein detected with the anti-Actin antibody (Abmart, Cat. No: M20009, dilution, 1:5000), was used as described previously59.

For the immunohistochemical assay, the fresh anthers of WT and pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1 transgenic maize line from S8b to S11 were infiltrated in a 3.7% FAA solution (Coolabor, China) overnight, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and embedded using paraffin (Sigma, USA) at 60 °C for 3 days. The anther samples were cut into 8 mm sections by a Leica RM2265 rotary microtome, dewaxed in xylene twice, and dehydrated in a gradient ethanol series (100, 95, 85, 70, and 50% in 0.85% NaCl). After washing with 1xPBS, the mouse anti-GFP antibody with immunofluorescence labeling (diluted 1:200 in PBS) and the goat anti-mouse conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (diluted 1:500) were used as the primary antibody and secondary antibody, respectively, to incubate samples. ZmENR1-GFP signals of anther samples were captured with a confocal scanner microscope (TCS-SP8, Leica).

Spatiotemporal expression analysis

Under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (TCS-SP8, Leica, Japan), the GFP fluorescence from anthers of a pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1 transgenic maize line was visualized as described previously33. Chlorophyll autofluorescence was used as an anther endothecium marker.

Cytological analysis and microscopy

Fresh anthers of WT and enr1 from S5 to S13 were immersed in FAA solution (Coolabor, China) for semi-thin transverse section and SEM analyses or 3.5% glutaraldehyde solution for TEM analysis. For semi-thin transverse section assays, anthers were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (50, 60, 70, 85, 95, and 100%, all v/v), embedded in graded Spurr resin (1:3, 1:1, and 3:1 (v/v) resin/ethanol), and polymerized at 70 °C for 3 days. Samples were then cut into 2 μm sections using a Leica RM2265 rotary microtome. These sections were stained with 0.1% (w/v) toluidine blue (Sigma-Aldrich, Castle Hill, Australia) for 5 min and observed with an Olympus BX-53 microscope. For SEM and TEM analyses, all procedures were performed as described previously34.

TUNEL assay

Anthers of WT and enr1 embedded in paraffin (Sigma, USA) were used for TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick-End Labeling) analysis. The subsequent procedures were performed as described previously61. Nick-end-labeled nuclear DNA fragments in the WT and enr1 were visualized with a Dead End Fluorometric TUNEL Kit (DeadEndTM Fluorometric TUNEL System, Promega). TUNEL signals were observed and photographed using a fluorescence confocal scanner microscope (TCS-SP8, Leica).

Tapetal cell DAPI staining

Paraffin-embedded anthers of WT and enr1 were treated as in a TUNEL assay. After fixation and staining using a 1 μg/mL DAPI (Sigma, USA) solution for 5 min in the dark, the samples were washed using 1xPBS twice (5 min each)38. Fluorescence was observed with a confocal laser-scanning microscope (TCS-SP8, Leica, Japan).

NBT staining

Fresh anthers of WT and enr1 from S8a to S12 were immersed in 10 mM potassium-citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and vacuum-infiltrated for 15 min, then exchanged with 0.5 mM NBT solution and incubated for 3 h at room temperature. The stained anthers were washed with 70% (v/v) ethanol thrice and immersed in FAA solution (Coolabor, China) overnight. Then, anthers of WT and enr1 were embedded in paraffin (Sigma, USA). The subsequent procedures were performed as described previously61. The signals were observed and photographed using an Olympus BX-53 microscope.

Measurement of ROS and H2O2 content assay

The collected fresh anthers of WT and enr1 were washed using PBS with 0.2% tween-20 for 5 min, then stained with H2DCF-DA (Sigma-Aldrich) or ROSGreen (Sigma-Aldrich) as described previously62,63. After washing twice with PBS, fluorescence was observed under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (TCS-SP8, Leica, Japan). The relative fluorescence intensities of ROS and H2O2 were quantified using the ImageJ software35.

Measurement of AsA and malate content assay

For the detection of AsA, anthers at various developmental stages were collected, and the AsA concentration was measured using an Ascorbic Acid Assay Kit (Abcam, Cat. No: ab65656) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For malate detection, anthers at various developmental stages were collected, and then the malate concentration was measured using a Malate Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No: MAK067) following the manufacturer’s instructions. All experiments contain six or nine biologically independent samples.

Mitochondrial complex I activity assay

For the detection of complex I activity, fresh anthers at various developmental stages were collected. The activity of the complex I was assessed by colorimetry using commercial kits (Abbkine, Cat. No: KTB1850, Wuhan, China) following manufacturer instructions. All experiments contain six or nine biologically independent samples.

Protein purification and enzymatic analysis

The CDSs of ZmENR1, the eight variants of ZmENR1 (T210I, S222A, Y248A, Y258A, M262, K266, P295, and S298), and ZmHAD1 were cloned and inserted into the pMCSG7 vector. Plasmids were transformed into a Transetta (DE3) Chemically Competent Cell. Recombinant proteins were induced using isopropylthio-b-galactoside overnight at 16°C and purified with a Mag-Beads MBP fusion protein purification kit (NEB, UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

For the enoyl-ACP reductase assay, crotonyl-CoA was used as a substrate, and the activity of enoyl-ACP reductase was measured by tracking the decrease of absorbance at 340 nm due to NADH oxidation47. The standard reaction mixture was prepared as described below: 10 μg recombinant proteins, 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.2), 150 μM crotonyl-CoA, and 150 μM NADH in a total volume of 800 μL.

IP-MS assay

Fresh anthers of WT and pZmENR1-GFP-ZmENR1 transgenic maize lines (three biological replicates, respectively) were collected Chloroplasts were isolated and extracted using a chloroplast isolation kit (product code CP-011; Invent) following manufacturer instructions. Then, isolated chloroplasts were ground in liquid nitrogen and dissolved in RIPA buffers to extract total protein. The RIPA buffer contains 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.8), 2 mM EDTA, a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.5% NP-40. The total protein was then collected from the RIPA buffer and separated by SDS–PAGE. The protein bands were excised to perform in-gel trypsin digestion and peptide extraction as described previously64. Then the digested proteins were performed by a LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer that was coupled to a nano Acquity UPLC system and further analyzed by tandemmass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The mass data were performed using MaxQuant software (v1.6.0.16). The parameters were set up as follows: full trypsin (KR) cleavage with 4 missed cleavage was performed. The peptide mass tolerance was 10 ppm (main search) and 20 ppm (precursor). Mass tolerance was 20 ppm for MS/MS. The search data of peptide and protein were filtered by 1% false discovery rate (FDR). Based on different sequence coverage in different samples, different abundant proteins were screened in the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database (https://www.uniprot.org/).

Subcellular localization

The CDSs of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 were cloned and inserted into the pUC19 vector65 by homologous recombination, resulting in the constructs ZmENR1-YFP and ZmHAD1-YFP, respectively. The constructs were transformed into maize protoplasts and YFP fluorescence in protoplasts was visualized under a confocal scanner microscope (TCS-SP8, Leica). The pUC19 vector containing the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) alone served as a negative control. Chlorophyll autofluorescence was used as a plastid marker. Primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

Y2H assay

Protein–protein interactions were checked using the matchmaker GAL4 Two-Hybrid System (Clontech)59. The CDSs of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 were cloned and fused into pGADT7 and pGBKT7 vectors, respectively. The constructs were then co-transformed into the yeast strain AH109 and developed on a DDO medium (SD/-Trp/-Leu) (Clontech, Cat. No: 630317) at 28°C for 3–5 days. The transformed yeasts were washed and resuspended with ddH2O to OD = 1.0 and then spotted onto a QDO medium (SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade) (Clontech, Cat. No: 630323). After growing at 28°C for 3–5 days, growths of yeast spots were observed to identify interactions. All primers for plasmid construction are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

LCI assay

The CDSs of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 were cloned and recombined into pCAMBIA1300-35S-nLUC and pCAMBIA1300-35S-cLUC, respectively. Then, the recombinant constructs were transformed into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404, followed by incubation, propagation, and resuspension in the activation buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, and 200 µM acetosyringone) to OD600 = 1. The desired Agrobacterium combinations were mixed in the dark for 3 h and infiltrated into fully expanded N. benthamiana leaves as described previously66. D-luciferin solution (Promega, Cat. No: E1602) was sprayed onto the leaves of N. benthamiana to detect luciferase activity. Images were captured with a low-light cooled CCD imaging apparatus (NightOWL II LB983 with Indigo software). Primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

BiFC assay

The CDSs of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 were fused with the N-terminal (nYFP: 1–155 aa) and C-terminal (cYFP: 156–239 aa) fragments of YFP, respectively. These fusion constructs were then recombined into the pUC19-35S vector65. Recombinant constructs were co-transformed into the maize protoplasts. The empty pUC19-35S vectors with N- and C-terminals were used as the negative control. YFP fluorescence was observed using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP8) as described previously67. Primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

Co-IP assay

The coding sequences of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 were cloned and recombined into the KpnI/BstbI-digested 35S-Ω-Flag vector and the SacI/SmaI-digested 35S-Ω-Myc vector34, respectively. The vector 35S-Ω-nYFP-Flag was used as a negative control. The constructs in various combinations were co-transformed into maize protoplasts and incubated at 28°C for 12 h in darkness. Protein isolation, immunoprecipitation with anti-cMyc affinity gel (E6654, Sigma-Aldrich), and western blot analysis were performed as described previously34. Primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

TDLR assay

The promoter regions of ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 (3000 bp upstream of the ATG start codon) were cloned from maize (B73) and recombined into the KpnI/BamHI-digested pEASY-LUC vector, respectively resulting in proZmENR1: LUC and proZmHAD1: LUC, which were used as reporters. To generate effector plasmids, the CDSs of ZmbHLH51 (Zm00001d053895), ZmMYB84 (Zm00001d025664), ZmMs7 (Zm00001d020680), and ZmMs1 (Zm00001d036435) were inserted into the pRTBD vector. The proAtUbiquitin3: REN plasmid was used as an internal control. Recombinant constructs in various combinations were co-transformed into the maize protoplasts and relative LUC activity (LUC/REN) was measured as described previously34. Primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

EMSA

Biotin-labeled ZmENR1 and ZmHAD1 promoter probes were obtained through the annealing of the antisense and sense primer pairs. The 5′ end of sense primers was labeled with biotin. The standard reaction mixture is described as follows: 800 ng recombinant proteins, 2 μL 5×binding buffer (GS005, Beyotime), 0.02 pmoL of the biotin-labeled promoter probes, and an appropriate aliquot of ddH2O in a total volume of 10 μL. To test the specificity of the DNA–protein interaction, excess core motif-mutated probes were added as competitors in separate reactions. The compound products were reacted at 25°C for 30 min, separated on 6% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels under non-denaturing conditions, transferred onto positively charged nylon membranes (GE Healthcare), and crosslinked with ultraviolet light as described previously34. The signals were detected using a LightShift™ Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (ECL; Thermo Fisher, USA). The purified MBP protein was used as a negative control. Primers used in the assay are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

Analysis of anther cutin, wax, and internal lipids