Abstract

Transgenic soybean [Glycine max(L.) Merrill] currently covers approximately 80% of the global crop area for this species, with the majority of transgenic plants being glyphosate resistant (Roundup Ready, GR or RR). However, there is significant concern regarding the potential effects of GM crops and their byproducts on soil microbial communities. During our research, we discovered a type of semiwild soybean that emerged due to genetic drift at a transgenic test site. Nevertheless, the ecological risk to soil rhizosphere microorganisms associated with planting semiwild soybean following genetic drift remains unclear. Therefore, we conducted a field experiment and collected soil samples at various stages of plant growth. Our results indicate that the species diversity of rhizosphere bacteria in transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean was also not significantly different from that observed in other types of soybean. Additionally, Basidiomycota had beneficial effects on rhizosphere fungi during the flowering and maturation stages in transgenic glyphosate-tolerant semiwild soybean. These findings provide valuable insights into how genetic drift in transgenic soybean may impact the soil microenvironment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-83676-x.

Keywords: Glyphosate resistance, Semiwild soybean, Microbial diversity, Microbial community structure

Subject terms: Biodiversity, Sequencing

In the context of agricultural production, the application of genetically modified crops has become an important means to improve crop yield, resist pests and reduce the use of chemical pesticides1–3. In particular, glyphosate-resistant soybean, as an outstanding representative genetically modified crop4, has been modified to tolerate the widely used herbicide glyphosate by modifying soybean genes for effective weed control while ensuring crop growth5,6. However, with the increasing popularity of such genetically modified crops, introducing glyphosate-resistant transgenic soybean into agricultural systems may lead to the flow of genes into wild soybeans via pollen, thereby increasing the degree of ecological risk caused by the formation of hybrid varieties under specific conditions7,8,9,10, which has gradually become a focus of scientific research and public discussion on the potential environmental impact. In addition, the impact of genetic drift of glyphosate-resistant transgenic soybean on the soil microbial community is an urgent problem in the field of agricultural science.

Soil microorganisms play a key role in maintaining the natural ecological balance11,12. They participate in the decomposition and recycling of soil organic matter13, affect the growth and development of plants14, and even influence the health and yield of crops15,16. Some studies have shown that the cultivation of GM crops does not affect soil microbial diversity or community structure17–20. The effects of multiresistant ScALDH21transgenic cotton on the soil microbial community have been studied, and the results revealed that the alpha and beta diversity indices of the soil microbiota were not different between two groups of transgenic and one group of nontransgenic cotton. The dominant clades of fungal and bacterial genera were equivalent at the phylum and genus levels in all three groups21. Lin et al. reported that there was no significant difference in the number of major soil microorganisms between tomatoes transformed with cucumber mosaic virus and wild-type tomatoes22. A 2-year field trial revealed no significant effects of GM high-methionine soybean on rhizosphere bacterial communities23. However, it has been argued that foreign gene products that are released from the residue of GM plants into the soil by root exudation may affect soil microbial communities24,25. Castaldini et al. reported differences in rhizospheric eubacterial communities associated with three lines of corn and a significantly lower level of mycorrhizal colonization in Bt176corn roots26. Kremer et al. reported that the prevalence of Pseudomonasamong the soil microorganisms of transgenic glyphosate-resistant soybean increased significantly compared with that of nontransgenic soybean27. Li Ning et al. reported that the amounts of ammoniated bacteria and nitrifying bacteria in the soil microorganisms of transgenic glyphosate-resistant soybean were much lower than those in nontransgenic soybean28. Therefore, an in-depth study on how the genetic drift of glyphosate-resistant transgenic soybean affects the structure and function of soil microorganisms may not only reveal the environmental effects of transgenic crops on agricultural production but also have important significance for evaluating the ecological safety of transgenic crops29–34.

This study aimed to explore the effects of the genetic drift of glyphosate-resistant transgenic soybean on soil microbial diversity and ecological function. Will the cultivation of glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean significantly affect the structure and diversity of soil microbial communities? We hypothesized that planting glyphosate-resistant semiwild-type soybean would have significant adverse effects on the overall community structure and diversity of soil microorganisms. Based on 16 S rRNA and ITS high-throughput sequencing technology, field experiments were conducted at different growth stages to study the effects of glyphosate-resistant semiwild-type soybean, the glyphosate-resistant soybean Hujiao 698, the cultivated soybean Dongnong 50 and wild soybean on the diversity and community structure of soil bacteria and fungi in farmland. The results support the development of more accurate environmental risk assessment models, providing a theoretical basis for the scientific assessment of the environmental risk of transgenic crops. In addition, this study explores sustainable development strategies for using transgenic technology in modern agriculture in order to provide a reference for the scientific planting and environmental protection of transgenic crops.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and molecular identification

The four soybean varieties used in this study were glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean (DT-1), glyphosate-resistant soybean variety Hujiao698 (HJ698), cultivated soybean variety Dongnong50 (D50) and wild soybean (WS-1). Fresh soybean leaves were placed in EP tubes, liquid nitrogen was added, and the samples were returned to the laboratory. DNA was extracted via the TaKaRa MiniBEST Universal Genomic DNA Extraction Kit Ver.5.0. The extracted genomic DNA was used as a template for PCR amplification. The primer pairs used to amplify the CP4-epsps gene (mCP4ES-F 5′-ACG GTG AYC GTC TTC CMG TTA C-3′ and mCP4ES-R 5′-GAA CAA GCA RGG CMG CAA CCA-3′) were added35. The results of electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel are shown in S1 (see Supplementary Materials), with “M” representing the marker, and showed that the glyphosate-resistant semi-wild soybean contained the EPSPS gene, validating its status as a genetically modified material.

Experimental design and sample collection

The field experiment was conducted at the transgenic test base of Northeast Agricultural University, Heilongjiang Province, China (45°74′ N, 126°73′ E). Isolation belts and fences were set up in the test area, and a specific individual was assigned to supervise. Three replicate plots for each of the four cultivars were established in a randomized design. A total of 48 samples (4 soybean varieties × 3 replications × 4 stages) were collected in this study. The rhizosphere soils of the four soybean varieties were sampled at the seedling (10 June), flowering (15 July), pod (25 August), and mature (30 September) stages. The samples were collected following the methods described by Babujia et al.36 and Lu et al.37. The soil adhering to the roots was removed, and the rhizosphere soil was collected in a plastic bag. The soil samples were placed in a cool place to air dry, ground, sieved, and then divided into two portions. One portion was used to quantify the soil microbial community, and the other was stored at −80 °C for DNA extraction.

Quantitative analysis of rhizosphere soil microorganisms

In this study, the plate culture method was used to quantify the bacteria and fungi in the rhizosphere soil. The calculation formula for determining the quantity of microorganisms was as follows:

Number of microorganisms per gram of soil = average number of colonies × dilution ratio/weight of the soil sample (%).

Test Method: First, 10 g of rhizosphere soil was weighed, and 100 mL of sterile water was added, followed by 15 min of oscillation. A total of 1 mL of the soil suspension was added to 9 mL of sterile water. Dilution ratios were 10−5, 10−6, and 10−7 for bacteria and 10−3, 10−4, and 10−5for fungi. Each diluted soil suspension was inoculated according to the mixed bacterial method, repeated five times. The bacteria were cultured at 28 °C for 48 h, and the fungi were cultured for 3 d. The colonies of bacteria and fungi at each dilution ratio were counted to quantify the bacteria and fungi. Bacteria were cultured on a beef extract peptone medium. Fungi were cultured on Martin’s medium, to which 0.3 mL of a 1% streptomycin solution was added for every 100 mL of medium in order to inhibit bacterial growth38.

DNA extraction and high-throughput sequencing analysis

A soil DNA extraction kit from Suzhou Keming Biotechnology Co., Ltd. was used in this study according to the kit instructions. A 250 mg soil sample was added to the tube, 750 µL of SL1 buffer and 150 µL of SX buffer were added, and the mixture was ground for 5 min before incubation for 13 min at 65 °C. Then, the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was added to a centrifuge tube containing SL3, mixed well, and incubated at −20 °C for 5 min. The mixture was subsequently centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was added to the Inhibitor Removal Column and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 2 min at room temperature. Next, 250 µL of SB buffer was added, and the mixture was mixed, transferred to a binding column, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 2 min at room temperature. After 700 µL of SW1 and SW2 were added for washing, 100 µL of eluent SE was added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 5 min and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min to elute the DNA.

Next-generation sequencing library preparation and Illumina MiSeq sequencing were performed at BGI (Shenzhen, China). PCR amplification of 16 S rRNA gene fragments was carried out with the primers 341 F (5′-ACT CCT ACG GGA GGC AGC AG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGA CTA CHV GGG TWT CTA AT −3′), as described by Ding et al.39. PCR amplification of the ITS region gene fragments was carried out with the primers its1 (5′-CTT GGT CAT TTA GAG GAA GTA A-3′) and its2 (5′-GCT GCG TTC TTC ATC GAT GC-3′), as described by Chen et al.40.

Bioinformatics analysis

The composition of the microbial communities in different soybean rhizosphere soil samples was analysed via the MISEQ PE300 sequencing platform. This included 16 treatment groups: seedling stage for D50 (AA), transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean (BA), HJ698 (CA), and wild soybean (DA); flowering stage for D50 (AB), transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean (BB), HJ698 (CB), and wild soybean (DB); pod stage for D50 (AC), transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean (BC), HJ698 (CC), and wild soybean (DC); and mature stage for D50 (AD), transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean (BD), HJ698 (CD), and wild soybean (DD). Each group had three independent biological replicates, resulting in a total of 48 libraries.

The filtered data were assembled into sequences using FLASH (v1.2.11) by merging paired-end reads based on their overlap, resulting in high-quality tags. OTUs were clustered at 97% similarity using UPARSE, and representative sequences for each OTU were obtained. Chimeric sequences generated by PCR amplification were removed from the representative OTU sequences using UCHIME (v4.2.40). After the OTU representative sequences were obtained, PyNAST software was used to align these sequences against the Greengenes database for taxonomic annotation. MUSCLE software was used to generate phylogenetic trees and standardize the OTU abundance information. The α and β diversity indices were conducted via QIIME software (V1.7.0) and R software (V3.4.1). The LEfSe online analysis platform was employed to estimate the impact of species abundance on differential effects and to identify species with significant differences between groups.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS (version 22.0, USA) was used to analyse the quantitative data for statistical significance at a confidence level of P < 0.05 or P < 0.01. The figures were generated via Origin (version 2021, USA) software.

Results

Quantitative analysis of rhizosphere soil microbial communities

The data presented in figure S2 demonstrates that the rhizosphere soil culturable bacteria and fungi counts of DT-1 during the seedling, pod, and mature stages of soybean growth did not significantly differ from those of D50, HJ698, and WS-1. However, at the flowering stage, the rhizosphere soil culturable bacteria count of DT-1 was significantly different from that of D50. Nevertheless, there was no significant difference in the rhizosphere soil culturable bacteria counts of DT-1 and WS-1. During the flowering stage, the rhizosphere soil culturable fungi count of DT-1 differed significantly from that of WS-1 and HJ698. However, there was no significant difference in the rhizosphere soil culturable fungi counts of DT-1 and D50 (see Supplementary Materials).

Effects of transgenic glyphosate-resistant semi-wild soybean on the compositions of the soil bacterial and Fungi communities

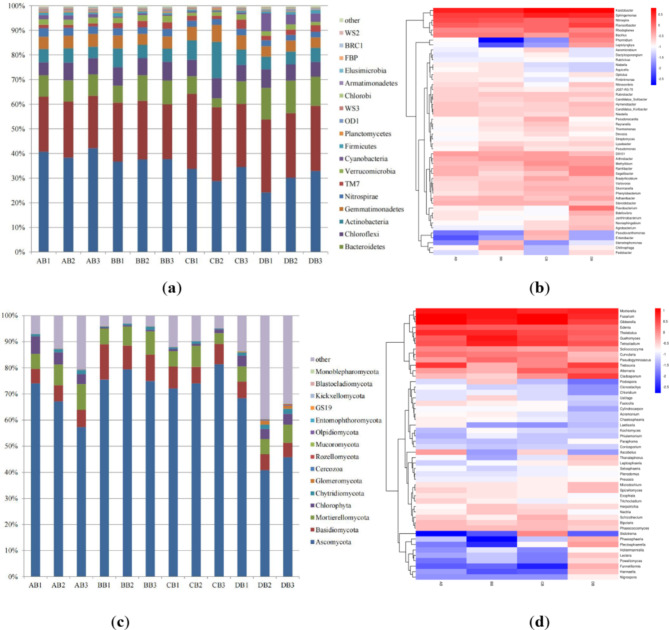

Bacterial and fungal community compositions at the flowering stage

The relative abundance at the phylum level of the bacteria and fungi in the rhizosphere soil of the different soybeans at the flowering stage are shown in Fig. 1a and c. Compared with those of D50, the relative abundances of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 increased from 22.11% and 8.68–23.31% and 8.98%, respectively, whereas those of Acidobacteria decreased from 40.39 to 37.34%. The relative abundances of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 increased from 66.17% and 6.08–76.58% and 10.93%, respectively, whereas that of Mortierellomycota decreased from 7.88 to 7.44%.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of the rhizosphere soil bacteria and fungi of DT-1 at the flowering stage. (a) Analysis of the rhizosphere soil bacterial composition at the phylum level; (b) Heatmap of the rhizosphere soil bacterial composition at the genus level; (c) Analysis of the rhizosphere soil fungal composition at the phylum level; (d) Heatmap of the rhizosphere soil fungal composition at the genus level.

Compared with those of HJ698, the relative abundances of Acidobacteria and Bacteroidetes in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 increased from 32.36% and 6.65–37.34% and 8.98%, respectively, whereas that of Proteobacteria decreased from 28.68 to 23.31%. The relative abundances of Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Mortierellomycota in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 increased from 75.83%, 7.51%, and 6.02–76.58%, 10.93%, and 7.44%, respectively.

Compared with that of WS-1, the relative abundance of Acidobacteria in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 increased from 29.08 to 37.34%, whereas those of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes decreased from 27.43% and 12.60–23.31% and 8.98%, respectively. The relative abundances of Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Mortierellomycota in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 increased from 51.64%, 6.00%, and 6.18–76.58%, 10.93%, and 7.44%, respectively.

The distribution of the bacterial and fungal community compositions at the genus level is illustrated in Fig. 1b and d. Compared with those of the other three soybeans, the abundances of the bacteria Steroidobacter, Lysobacter, Pseudomonas, Chitinophaga, Niabella, Stenotrophomonas, and Aquicella and the fungi Acremonium, Guehomyces, Herpotrichia, Nectria, Podospora, Pseudogymnoascus, Tetracladium, Ustilago, Kochiomyces, Chloridium, and Phialemonium were greater in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1.

In contrast, compared with those of the other three soybeans, the abundances of the bacteria Kaistobacter, Sphingomonas, Ramlibacter, Methylibium, Segetibacter, Bradyrhizobium, Hymenobacter, Phormidium, Novosphingobium, Agrobacterium, Janthinobacterium, Leptolyngbya, and Rubrivivax and the fungi Alternaria, Ascobolus, Bipolaris, Cladosporium, Hannaella, Phaeosphaeria, Plectosphaerella, Schizothecium, Setosphaeria, Thanatephorus, Trebouxia, Paraphoma, Coniosporium, and Nigrospora were lower in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1.

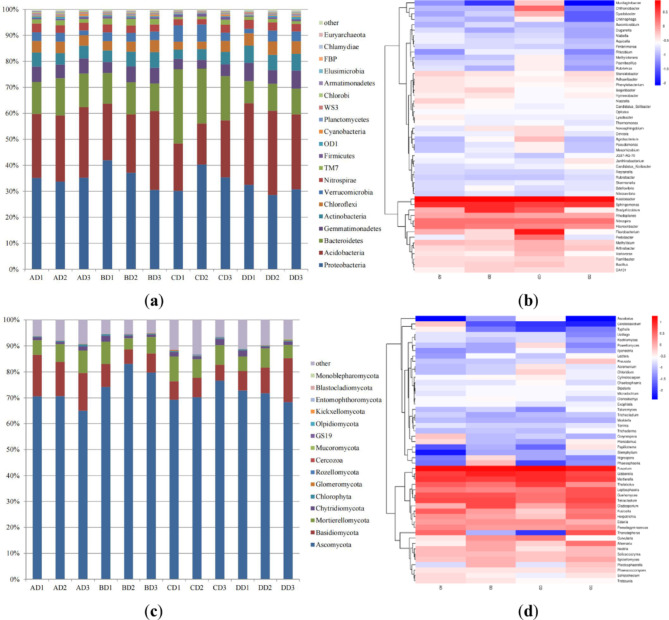

Bacterial and fungal community composition at the mature stage

The relative abundances at the phylum level of the rhizosphere bacteria and fungi in the different soybeans at the mature stage are shown in Fig. 2a and c.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the rhizosphere soil bacteria and fungi of DT-1 at the mature stage. (a) Analysis of the rhizosphere soil bacterial composition at the phylum level; (b) Heatmap of the rhizosphere soil bacterial composition at the genus level; (c) Analysis of the rhizosphere soil fungal composition at the phylum level; (d) Heatmap of the rhizosphere soil fungal composition at the genus level.

Compared with those of D50, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 increased from 34.70 to 36.54%, whereas those of Acidobacteria and Bacteroidetes decreased from 25.72% and 13.21–24.82% and 11.61%, respectively. The relative abundance of Ascomycota in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 increased from 68.73 to 79.00%, whereas those of Basidiomycota and Mortierellomycota decreased from 14.59% and 7.03–7.24% and 6.40%, respectively.

Compared with those of HJ698, the relative abundances of Proteobacteria and Acidobacteria in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 increased from 35.29% and 18.63–36.54% and 24.82%, respectively, whereas that of Bacteroidetes decreased from 22.23 to 11.61%. The relative abundances of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 increased from 72.05% and 6.90–79.00% and 7.24%, respectively, whereas that of Mortierellomycota decreased from 8.08 to 6.40%.

Compared with those of WS-1, the relative abundances of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 increased from 30.62% and 9.60–36.54% and 11.61%, respectively, whereas that of Acidobacteria decreased from 30.85 to 24.82%. The relative abundances of Ascomycota and Mortierellomycota in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 increased from 70.99% and 6.01–79.00% and 6.40%, respectively, whereas that of Basidiomycota decreased from 11.42 to 7.24%.

The distribution of the bacterial and fungal community compositions at the genus level is illustrated in Fig. 2b and d. Compared with those of the other three soybeans, the abundances of the bacteria Bradyrhizobium, Nitrospira, Rhodoplanes, DA101, Segetibacter, Hymenobacter, Dyadobacter, Bdellovibrio, and Aeromicrobium and the fungi Cladosporium, Clonostachys, Edenia, Gibberella, Guehomyces, Nectria, Nigrospora, Phaeosphaeria, Plectosphaerella, and Solicoccozyma were greater in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1.

In contrast, compared with those of the other three soybeans, the abundances of the bacteria Ramlibacter, Rubrobacter, and Duganella and the fungi Leptosphaeria, Preussia, Pseudogymnoascus, Toninia, Trichocladium, and Mrakiella were lower in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1.

In this study, the population of delayed Rhizobium associated with symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 soybean during the flowering period decreased compared to that of the other three soybeans. However, the population of Bradyrhizobium associated with symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the rhizosphere soil of DT-1 soybean at the mature stage increased compared to that of the other three soybeans.

Diversity of the bacterial and fungi community

Diversity of the bacterial community

The results of the bacterial diversity analysis are shown in Figs. 3 and 4a-d. The Shannon and Simpson diversity indices were used to evaluate microbial diversity41. Both indices indicated that the rhizosphere bacteria of DT-1 were similar to those of the other three soybeans at all stages. At the pod stage, the Shannon index of Hujiao 698 was significantly lower than that of wild soybean (p < 0.05), indicating a reduction in the species diversity of soil bacteria in the rhizosphere due to the root exudates of Hujiao 698. However, there was no significant difference in the Shannon index between the transgenic EPSPS-resistant semiwild soybean and wild soybean, suggesting that the decline in the species diversity of the soil bacteria in the rhizosphere was not caused by the EPSPS protein.

Fig. 3.

Effects of different soybean growth stages on the soil bacterial Shannon index. (a) seedling, (b) flowering, (c) pod, (d) mature.

Fig. 4.

Effects of soybean growth stages on the soil bacterial Simpson index. (a) seedling, (b) flowering, (c) pod, (d) mature.

Diversity of the fungi community

The results of the fungal diversity analysis are shown in Figs. 5 and 6a-d. There was no significant difference between the Shannon index of the transgenic semiwild soybean and those of Dongnong 50 and Hujiao 698 at the flowering stage (p > 0.05), but the Shannon index of the transgenic semiwild soybean significantly decreased compared with that of wild soybean (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in the Simpson index of fungi in the rhizosphere soil of the transgenic herbicide-resistant semiwild soybean at the flowering stage compared with that of Hujiao 698, but it was significantly lower (p < 0.05) than those of Dongnong 50 and wild soybean.

Fig. 5.

Effects of different soybean growth stages on the soil fungal Shannon index. (a) seedling, (b) flowering, (c) pod, (d) mature.

Fig. 6.

Effects of soybean growth stages on the soil fungal Simpson index. (a) seedling, (b) flowering, (c) pod, (d) mature.

LEfSe analyses of the bacterial and fungi communities

LEfSe analysis of the bacterial community

The results of the linear discriminant analysis of the bacterial community are shown in Fig. 7a-c. Figure 7a shows that, Rhizobiaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Pseudonocardiaceae, Dyadobacter and Novosphingobium were more prominent in DT-1 than in D50. As depicted in Fig. 7b, Proteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Pseudonocardiaceae, Sinobacteraceae, Solitalea and DA101 were prominent in DT-1 than in HJ698. As depicted in Fig. 7c, Chitinophaga and Dyadobacter were more predominant in DT-1 than in WS-1.

Fig. 7.

Cladograms of line discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analyses based on bacterial community composition in different soybeans. AD: D50; BD: DT-1; CD: HJ698; DD: WS-1.

LEfSe analysis of the fungal community

The results of the linear discriminant analysis of the fungal community are shown in Fig. 8a-c. Figure 8a shows that, Glomerellales, Capnodiales, Chaetomiaceae, Phaeosphaeriaceae and Cantharellales fam incertae sedis were more prominent in DT-1 than in D50. As depicted in Fig. 8b, Basidiomycota, Glomerellales, Phaeosphaeriaceae, Nectria and Schizothecium were more prominent in DT-1 than in HJ698. As depicted in Fig. 8c, Trichosphaeriales, Hypocreales, Cantharellales fam incertae sedis, Phaeosphaeriaceae and Curvularia were more predominant in DT-1 than in WS-1.

Fig. 8.

Cladograms of line discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analyses based on fungal community composition in the different soybeans. AD: D50; BD: DT-1; CD: HJ698; DD: WS-1.

Discussion

The insertion of foreign genes in transgenic crops has the potential to alter both the composition and quantity of root exudates42, and the exudates released from the roots of these plants may consequently impact the abundance of soil microbial communities43. The hybrid offspring formed after the genetic drift of the glyphosate-tolerant transgenic soybean gene contained the glyphosate tolerance gene, and its secretions caused microbial changes, which can reflect the impact of transgenic crops on the soil ecological environment. These results indicated that DT-1 produced by genetic drift had no effect on rhizosphere soil bacteria or fungi. However, some results have shown a significant increase in the total bacterial biomass in soil with transgenic soybean, in contrast to that in soil cultivated with nontransgenic soybean44.

This study revealed that the species diversity of fungi in the rhizosphere soil of transgenic herbicide-resistant semiwild soybean plants was significantly lower than that in the rhizosphere soil of wild soybean plants at the flowering stage of soybean growth. However, there was no significant difference in the species diversity of fungi in the rhizosphere soil of the transgenic herbicide-resistant semiwild soybean compared with those of the other three soybeans at the other growth stages, which indicates that the species diversity of fungi in the rhizosphere soil of the transgenic herbicide-resistant semiwild soybean has temporal specificity and does not affect the soil environment. Most studies have consistently demonstrated that there are no significant differences in the diversities of bacterial communities between transgenic glyphosate-resistant soybeans and nontransgenic soybeans at various stages45,46. One study reported that GR significantly increased the abundance and diversity of the soil rhizospheric bacterial community at the pod stage47. The glyphosate-tolerant soybean affecting the phylogenetic diversity of rhizosphere bacterial communities together with a significant difference in the relative abundances of some rhizosphere bacteria at different classification levels compared with those of the control cultivar48.

The maturation of soybeans influences the composition of key microorganism communities in soil49. The results of this study indicate that Proteobacteria was found to be advantageous over different types of soybeans during maturity. This is consistent with the findings of Nie et al. and Wang et al.50,51These results indicated that Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria and Actinobacteria are the predominant phyla. Compared with that in nontransgenic soybean, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria in transgenic glyphosate-resistant soybean was lower by 5.28% at the mature stage51. However, our experiment revealed that the transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean presented a greater abundance of Proteobacteria compared to other soybeans. The abundance of Bradyrhizobium associated with symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean decreased during the flowering stage but increased during the maturity stage compared to those in the other soybeans. Rhizobacteria have the ability to establish symbiotic nodules specifically with leguminous plants, and the slow-growing root nodule bacteria in soybeans serve as nitrogen-fixing symbionts. Therefore, compared with nontransgenic soybeans, transgenic herbicide-resistant semiwild-type soybean with root nodules exhibit increased nitrogen fixation52. Legume‒rhizobia symbiosis enables biological nitrogen fixation to improve crop production for sustainable agriculture53.

At present, there are few reports on the diversity of fungi in the rhizosphere soil of transgenic glyphosate-resistant soybean. This study provides basic data on the diversity of rhizosphere fungi in transgenic soybeans. There was no significant difference in the microbial abundance of transgenic cotton compared with that of nontransgenic cotton in studies by Qi and others54. The flowering stage represents the most vigorous period of soybean plant growth and has the greatest effect on soil microorganisms55. This study revealed that at the flowering stage of soybean growth, the genetic diversity of fungi in the rhizosphere soil of transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean was significantly lower than that in the rhizosphere soil of wild soybean. The sequencing results revealed that during different periods of soybean growth, the rhizosphere fungi of the rhizosphere soil of the transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean were dominated by Basidiomycota over those of the cultivated Dongnong 50 and wild soybeans. Therefore, the predominant phylum associated with the rhizosphere fungi of genetically modified glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean is Basidiomycota.

Conclusion

This study investigated the impact of transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean on the root zone soil microbial community through detailed field experiments and high-throughput sequencing technology. The results revealed that the bacterial and fungal populations in the rhizosphere soil of the transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean at the seedling, pod, and mature stages were not significantly different from those in the rhizosphere soil of the other soybeans. However, the fungal species diversity in the rhizosphere soil of the transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean was significantly lower than that in the rhizosphere soil of the wild soybean at the flowering stage. Additionally, the abundance of Proteobacteria was greater in the mature stage of transgenic glyphosate-resistant semiwild soybean than in other soybeans, whereas the number of nitrogen-fixing root nodules associated with soybeans decreased in the flowering stage and increased in the mature stage. These findings provide a new perspective for understanding the impact of transgenic soybean genetic drift on the soil microenvironment and provide important scientific evidence for future assessments of the environmental risk of transgenic crops.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.D., L.X. and W.D.; methodology, J.S.D. and F.Y.G.; data processing, J.S.D. and L.X.; investigation, J.S.D.; resources, W.D. and J.S.D.; writing original draft preparation, F.Y.G. and J.S.D.; writing review and editing, F.Y.G.; supervision, L.X. and W.D.; funding acquisition, J.S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Harbin University Young Doctor Scientific Research Foundation (Grant No. HUDF2021110) and Heilongjiang Province postdoctoral funding (Grant No. LBH-Z20005).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information with the primary accession code PRJNA1186822, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. Other data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary materials files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Approval for plant experiments

We have permission to collect wild soybean. The experiment complied with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. The transgenic soybean Hujiao 698 and the cultivated soybean Dongnong 50 were provided by the Pesticide Research Laboratory of Northeast Agricultural University. The glyphosate-resistant semiwild and wild soybeans were collected from the field. All materials were stored in the Pesticide Research Laboratory of Northeast Agricultural University.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brookes, G. Genetically modified (GM) Crop Use 1996–2020: Environmental impacts Associated with Pesticide Use CHANGE. GM Crops Food. 13 (1), 262–289. 10.1080/21645698.2022.2118497 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raman, R. The impact of genetically modified (GM) crops in modern agriculture: a review. GM Crops Food. 8 (4), 195–208. 10.1080/21645698.2017.1413522 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, J. A. et al. Genetically Engineered crops: importance of Diversified Integrated Pest Management for Agricultural sustainability. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.7, 24. 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00024 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonny, S. Genetically modified herbicide-tolerant crops, weeds, and herbicides: overview and impact. Environ. Manage.57 (1), 31–48. 10.1007/s0026701505897 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nandula, V. K. Herbicide resistance traits in maize and soybean: current Status and Future Outlook. Plants8, 337. 10.3390/plants8090337 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chauhan, B. S. et al. Emerging challenges and Opportunities for Education and Research in Weed Science. Front. Plant. Sci.8, 1537. 10.3389/fpls.2017.01537 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang, R. et al. Fitness and Rhizobacteria of F2, F3 hybrids of herbicide-tolerant transgenic soybean and wild soybean. Plants11, 3184. 10.3390/plants11223184 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang, R. et al. Fitness and hard seededness of F2 and F3 descendants of hybridization between herbicide-resistant Glycine max and G. Soja. Plants12, 3671. 10.3390/plants12213671 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shao, Z., Huang, L., Zhang, Y., Qiang, S. & Song, X. Transgene was silenced in hybrids between transgenic herbicide-resistant crops and their wild relatives utilizing alien chromosomes. Plants (Basel). 11 (23), 3187. 10.3390/plants11233187 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu, L. et al. Fitness and ecological risk of hybrid progenies of wild and herbicide-tolerant soybeans with EPSPS Gene. Front. Plant. Sci.13, 922215. 10.3389/fpls.2022.922215 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aqeel, M. et al. Plant-soil-microbe interactions in maintaining ecosystem stability and coordinated turnover under changing environmental conditions. Chemosphere318, 137924. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.137924 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang, J. L. et al. Balanced fertilization over four decades has sustained soil microbial communities and improved soil fertility and rice productivity in red paddy soil. Sci. Total Environ.793, 148664. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148664 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumann, K. et al. Soil microbial diversity affects soil organic matter decomposition in a silty grassland soil. Biogeochemistry114, 201–212. 10.1007/s10533-012-9800-6 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacoby, R., Peukert, M., Succurro, A., Koprivova, A. & Kopriva, S. The role of Soil microorganisms in Plant Mineral Nutrition-current knowledge and future directions. Front. Plant. Sci.8, 1617. 10.3389/fpls.2017.01617 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tahat, M. M., Alananbeh, K. A., Othman, Y. I. & Leskovar, D. Soil Health and sustainable agriculture. Sustainability12, 4859. 10.3390/su12124859 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah, K. K. et al. Role of soil microbes in sustainable crop production and soil health: a review. Agricultural Sci. Technol.13 (2), 109–118. 10.15547/ast.2021.02.019 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta, A. et al. Linking Soil Microbial Diversity to Modern Agriculture practices: a review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 3141. 10.3390/ijerph19053141 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lebedev, V., Lebedeva, T., Tikhonova, E. & Shestibratov, K. Assessing impacts of Transgenic Plants on Soil using functional indicators: twenty years of Research and perspectives. Plants (Basel). 11 (18), 2439. 10.3390/plants11182439 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang, J., Chapman, S. J., Ye, Q. F. & Yao, H. Y. Limited effect of planting transgenic rice on the soil microbiome studied by continuous 13CO2 labeling combined with high-throughput sequencing. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.103 (10), 4217–4227. 10.1007/s00253-019-09751-w (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang, H. et al. Effect of vegetation of transgenic bt rice lines and their straw amendment on soil enzymes respiration functional diversity and community structure of soil microorganisms under field conditions. J. Environ. Sci. (China). 24 (7), 1259–1269. 10.1016/s1001-0742(11)60939-x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang, Q. et al. Effects of multi-resistant ScALDH21 transgenic cotton on soil microbial communities. Front. Microbiomes. 2, 1248384. 10.3389/frmbi.2023.1248384 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin, C. H. & Pan, T. M. PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis to assess the effects of a genetically modified cucumber mosaic virus-resistant tomato plant on soil microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.76 (10), 3370–3373. 10.1128/AEM.00018-10 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang, J. et al. A 2-year field trial reveals no significant effects of GM high-methionine soybean on the rhizosphere bacterial communities. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.34 (8), 113. 10.1007/s11274-018-2495-7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan, Z. J. et al. Do genetically modified plants affect adversely on soil microbial communities? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ.235, 289–305. 10.1016/j.agee.2016.10.026 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hannula, S. E., De Boer, W. & Van Veen, J. A. Do genetic modifications in crops affect soil fungi? A review. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 50, 433–446. 10.1007/s00374-014-0895-x (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castaldini, M. et al. Impact of Bt corn on rhizospheric and soil eubacterial communities and on beneficial mycorrhizal symbiosis in experimental microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.71 (11), 6719–6729. 10.1128/AEM.71.11.6719-6729.2005 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kremer, J. R., Means, E. N. & Kim, S. Glyphosate affects soybean root exudation and rhizosphere micro-organisms. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem.85 (15), 1165–1174. 10.1080/03067310500273146 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, N. & Wang, H. Y. Effect of RRS on nitrogen transition and related bacteria in rhizosphere soil. J. Northeast Agricultural Univ. (English Edition). 14 (4), 333–336 (2007). https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:DBYN 0.2007-04-012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsatsakis, A. M. et al. Environmental impacts of genetically modified plants: a review. Environ. Res.156, 818–833. 10.1016/j.envres.2017.03.011 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agarwal, A. V. & Singh, R. P. Assessment of the Environmental and Health Impacts of genetically modified crops. Policy Issues Genetically Modified Crops. 335–354. 10.1016/B978-0-12-820780-2.00015-7 (2021).

- 31.Dale, P. J. The environmental impact of genetically modified (GM) crops: a review. J. Agricultural Sci.138 (3), 245–248. 10.1017/S0021859602001971 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sohn, S. I. et al. A review of the unintentional release of feral genetically modified rapeseed into the Environment. Biology (Basel). 10 (12), 1264. 10.3390/biology10121264 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanvido, O., Romeis, J. & Bigler, F. Ecological impacts of genetically modified crops: ten years of field research and commercial cultivation. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol.107, 235–278. 10.1007/10.2007.048 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jha, A. K., Chakraborty, S., Kumari, K. & Bauddh, K. Ecological consequences of genetically modified crops on Soil Biodiversity. Ecol. Practical Appl. Sustainable Agric. 89–106. 10.1007/978-981-15-3372-3_5 (2022).

- 35.Jin, L. et al. Proteomics analysis reveals that foreign cp4-epsps gene regulates the levels of shikimate and branched pathways in genetically modified soybean line H06-698. GM Crops Food. 12 (1), 497–508. 10.1080/21645698.2021.2000320 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babujia, L. C. et al. Impact of long-term cropping of glyphosate-resistant transgenic soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] On soil microbiome. Transgenic Res.25 (4), 425–440. 10.1007/s11248-016-9938-4 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu, G. H. et al. Effects of an EPSPS-transgenic soybean line ZUTS31 on root-associated bacterial communities during field growth. PLoS One. 13 (2), e0192008. 10.1371/journal.pone.0192008 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ranganayaki, N., Tilak, K. V., Manoharachary, C. & Mukerji, K. G. Methods and techniques for isolation enumeration and characterization of rhizosphere microorganisms. Microb. Activity Rhizoshere. 17–38. 10.1007/3-540-29420-1_2 (2006).

- 39.Ding, C., Adrian, L., Peng, Y. & He, J. 16S rRNA gene-based primer pair showed high specificity and quantification accuracy in detecting freshwater Brocadiales anammox bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol.96 (3), fiaa013. 10.1093/femsec/fiaa013 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Chen, L. Z., Li, Y. L. & Yu, Y. L. Soil bacterial and fungal community successions under the stress of chlorpyrifos application and molecular characterization of chlorpyrifos-degrading isolates using ERIC-PCR. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 15 (4), 322–332. 10.1631/jzus.B1300175 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou, H. et al. Rapid Effect of Nitrogen Supply for Soybean at the beginning flowering stage on biomass and sucrose metabolism. Sci. Rep.9 (1), 15530. 10.1038/s41598-019-52043-6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu, J. et al. Impact of transgenic wheat with wheat yellow mosaic virus resistance on microbial community diversity and enzyme activity in rhizosphere soil. PLoS One. 9 (6), e98394. 10.1371/journal.pone.0098394 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tao, J. et al. Maize growth responses to soil microbes and soil properties after fertilization with different green manures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.101 (3), 1289–1299. 10.1007/s00253-016-7938-1 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vilvert, R. M., Aguiar, D., Gimenes, R. M. T. & Alberton, O. Residual effect of transgenic soybean in soil microbiota. Afr. J. Agric. Res.9 (30), 2369–2376. 10.5897/AJAR2013.8264 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang, M. et al. Impact of a G2-EPSPS & GAT dual transgenic glyphosate-resistant soybean line on the Soil Microbial Community under Field conditions affected by glyphosate application. Microbes Environ.35 (4), ME20056. 10.1264/jsme2.ME20056 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Souza, R. A. et al. Impact of the ahas transgene and of herbicides associated with the soybean crop on soil microbial communities. Transgenic Res.22 (5), 877–892. 10.1007/s11248-013-9691-x (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen, B. et al. Effects of glyphosate-resistant transgenic soybean on soil rhizospheric bacteria and rhizobia. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao. 29 (9), 2988–2996. 10.13287/j.1001-9332.201809.002 (2018). Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu, G. H. et al. Impact of a glyphosate-tolerant soybean line on the Rhizobacteria revealed by Illumina MiSeq. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.27 (3), 561–572. 10.4014/jmb.1609.09008 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei, W. et al. Long-term fertilization coupled with rhizobium inoculation promotes soybean yield and alters soil bacterial community composition. Front. Microbiol.14, 1161983. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1161983 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nie, Y., Wang, D. Q., Zhao, G., Yu, S. & Wang, H. Y. Effects of Betaine Aldehyde dehydrogenase-transgenic soybean on phosphatase activities and Rhizospheric Bacterial Community of the saline-alkali soil. Biomed. Res. Int.2016, 4904087. 10.1155/2016/4904087 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang, L., Li, Z., Liu, R., Li, L. & Wang, W. Bacterial diversity in soybean Rhizosphere Soil at Seedling and mature stages. Pol. J. Microbiol.68 (2), 281–284. 10.33073/pjm-2019-023 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bünger, W. et al. Root Nodule Rhizobia from undomesticated shrubs of the Dry Woodlands of Southern Africa can Nodulate Angolan Teak Pterocarpus angolensis an important source of timber. Front. Microbiol.12, 611704. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.611704 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang, Z. et al. A small heat shock protein GmHSP17.9 from nodule confers symbiotic nitrogen fixation and seed yield in soybean. Plant. Biotechnol. J.20 (1), 103–115. 10.1111/pbi.13698 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qi, X. et al. Assessing Fungal Population in Soil planted with Cry1Ac and CPTI Transgenic Cotton and its conventional parental line using 18S and ITS rDNA sequences over Four Seasons. Front. Plant. Sci.7, 1023. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01023 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He, X., Wu, C., Tan, H., Deng, X. & Li, Y. Impact of combined exposure to Glyphosate and Diquat on Microbial Community structure and diversity in Lateritic Paddy Soil. Sustainability15, 8497. 10.3390/su15118497 (2023). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information with the primary accession code PRJNA1186822, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. Other data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary materials files.