Abstract

The content of presleep thoughts have been assumed to influence sleep quality for a long time, e.g., insomnia has repeatedly been discussed to be associated with anxious thoughts before falling asleep. However, the phenomenon of recurring, voluntary fantasizing before sleep does not appear to be a common research topic. In the first stage of this study, we explored the frequency of presleep fantasizing on a sample of 281 volunteers. In the second stage, we analyzed the content of ca. 5000 fantasy descriptions found online to discover similar patterns. Our results showed that approximately 75% of the respondents fantasizes before sleep regularly and could describe three main topics during categorization (‘aims and ambitions’, thinking about a ‘calming’ scene, ‘fading away and death’). Based on our findings, presleep fantasizing is a common phenomenon. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate and categorize presleep fantasies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-83642-7.

Keywords: Sleep, Fantasy, Presleep fantasy, Presleep period

Subject terms: Circadian rhythms and sleep, Cognitive neuroscience

Introduction

Cognitive activity during the presleep period has been suggested to influence sleep quality and thus the contribution to insomnia for a long time1, however, the content of presleep thoughts remains on the periphery of this research field2,3. The shift of attention from the external world to our inner thoughts is something that we experience regularly, most of us tend to spend 50% of our time during the day with task-unrelated thoughts4.

Fantasizing and being occupied with our own personal thoughts are often introduced as a failure of executive control5, therefore many disadvantages can be highlighted like sleep difficulties6, worse performance and daytime functioning7. On the contrary, there is a more positive apprehension of the phenomenon. Because it is so common, some studies have suggested that it has a valuable function: depending on the associated feelings, fantasizing could contribute to attentional fluctuations, dishabituation (when a break from an ongoing task allows to enhance learning potential), thinking through future plans and enhanced creativity8. In this sense, while some studies consider it to be an interruption of an ongoing task, there is growing evidence showing that fantasizing facilitates adaption9 and can contribute to self-development. In summary, while fantasizing has been seen as both a cost and a benefit10, its function and value remain unclear. One possible explanation is that when a certain task or goal is considered too limited, the mind starts to explore something more advantageous11. However, it has also been suggested, that it would be important to distinguish between intentional and unintentional forms of this phenomenon12.

During the period of falling asleep, the perception of external stimuli is steadily reduced, allowing for voluntary presleep fantasizing. We can find two types of task-unrelated thoughts, based on whether the attentional shift is consciously or unconsciously controlled, presleep fantasizing can take the conscious form, attention deliberately shifts from the external to the internal world13. Why this phase could be meaningful in sleep research is shown by the many aspects sleep is linked to emotions. Stress can alter sleep through sleep fragmentation and increased sleep latency14. An other study showed, that a negative feedback provided on a test to participants, resulted in deteriorated sleep quality15. These results pointed to the extent of how emotions play a role in determining sleep aspects in otherwise healthy individuals. The connection is bidirectional: decreased sleep efficiency alters emotion regulation as well16. Although studies agree that there is a link between presleep cognitive activity and sleep quality, it is hard to compare the results of these studies due to the absence of presleep fantasies’ content descriptions17.

The power of presleep thoughts, and their influence on sleep quality is well known, mostly related to negative consequences: ruminative and anxious thoughts may contribute to poorer sleep quality18, repetitive thoughts of stressful events may lead to elevated arousal, delayed sleep onset and thus diminishing sleep19. On the other hand, the nature of presleep thoughts could be influenced to improve sleep quality, for example by listening to relaxing words before sleep: the processing of relaxing words could activate several other brain regions contributing to calmness20. Thus, we hypothesized, that a different character of conscious, voluntary fantasizing would help the transition to sleep. To analyze the content of presleep fantasies, we examined online platforms dedicated to sharing such information. In an article posted on Buzzfeed on the 14th of November, 2017., titled “34 Pre-Sleep Fantasies That Will Make You Say “I thought I Was The Only One”” (https://www.buzzfeed.com/annaborges/before-bed-fantasies), the author, Anna Borges asked the community to post these fantasies. The content of these fantasies was e.g., relationship, prize winning, or fantasies inspired by movies or celebs. Online platforms may help discover a wider range of presleep thoughts: anonymity encourages users to share sensitive information about themselves compared to the identifiable users21. In this study, our aim was to discover the prevalence of fantasizing before falling asleep and analyzing the content of these fantasies, for similar patterns to be uncovered. In the first stage, with an online questionnaire, we asked about the frequency of presleep fantasizing, in the second stage, we collected descriptions of presleep fantasies online.

Methods

Study I

In study I, we assembled a questionnaire package as an assessment of sleep quality and the occurrence of presleep fantasies. The questionnaire package contained two questionnaires (short version of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index - PSQI & Glasgow Content of Thoughts Inventory - GCTI) and two extra questions about fantasizing and creating stories in the presleep period.

The survey was assembled in Google Forms and shared on social media platforms, on Facebook. Participants were instructed to read the items carefully and answer the first thing that come to their minds. They were informed that all of their answers would remain anonymous. Additionally, we asked three questions on demographics (age, gender, education). The answers were collected from the 1st of March to the 25th of March 2021.

Participants

Our questionnaire package was accessible through an online link and 281 participants (243 females and 38 males) completed the questionnaire form. The mean age was 33.91 years (SD = 13.14). According to the education, participants were classified as: 37% Master’s Degree, 19.5% Bachelor’s Degree, 32% High School Graduate and 11.5% less than High School.

During this study, all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Based on the official statement of the Regional Research Ethics Committee of the University of Pécs (9861 – PTE 2024) an Ethical Approval was not necessary for this study. Using this questionnaire was considered safe, as all data were collected anonymously. With completing the online questionnaire, applicants voluntarily took part in this study, and an informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)

To measure subjective sleep quality over a one-month period, we used the Hungarian version of PSQI22. PSQI is a widely accepted, self-rated questionnaire, which contains 19 self-reported items and 5 questions to be answered by roommate or bed partner. The global score consists of seven components: perceived sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, hypnotic medication use and daytime dysfunction. According to our interest we removed a few components: hypnotic medication use, daytime dysfunction and rating of bed partner/roommate, since these questions refer to the clinical aspects of sleep difficulties. Although daytime dysfunction and hypnotic medication use supposedly interfere with presleep cognitive activity, in this study, our interest was mainly focused on the other characteristics of sleep. Each component score was calculated from the item scores that range from zero to three (0 = no problem, 3 = severe problem).

Glasgow content of thoughts inventory (GCTI)

The 25-item self-report GCTI contains categories of presleep thoughts, which were collected from insomniac subjects to analyze the nature and intrusiveness of their thoughts. The questionnaire items represent these thoughts that insomniac people tend to revolve around prior to sleep. Every item should be answered on a 4-point scale (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = always)23. In the lack of the validated Hungarian version, the original GCTI was translated into Hungarian by our research team. Two extra questions were added as item 26 and item 27, reflecting to presleep fantasizing and creating stories (“In the past 7 days before sleep I was preoccupied with fantasizing”, “In the past 7 days before sleep I was preoccupied with creating stories”). Listing both of them might help discover different aspects of the presleep cognitive activity. Although these questions were listed at the end of the GCTI questionnaire, we would not include them as questionnaire scores, they were used to indicate the frequency of fantasizing and creating stories. To get a broader picture of presleep thoughts, two sets of the GCTI questionnaire were used indicating presleep thoughts of the past week and the past ten years.

Statistical analysis

To perform statistical analysis, we used IBM SPSS Statistics 25 software (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Descriptive statistics were used to analyse demographical data, the mean and standard deviations were calculated. For the correlational analysis, Spearman’s correlation was used.

Study II

The purpose of Study II was to analyze presleep fantasies shared in online forums and categorize them according to their contents. To our best knowledge, to date, no other study has found intersubject similarities regarding the content and motives in presleep thoughts.

The following search terms were used in Google search: “presleep fantasy”, “presleep thoughts”, “go-to fantasy”, “falling asleep fantasy”, “presleep period”. For the purpose of the analysis, we selected two online forums. Most of the reports were found on a Reddit forum, entitled “What is your go-to fantasy you think of before falling asleep” (https://www.reddit.com/r/AskReddit/comments/8z157b/what_is_your_goto_fantasy_you_think_of_before/). About 9500 reports were within this range. Since many of them were not related to the original question, a screening procedure was applied to remove unrelated reports. Therefore, 5090 fantasies remained in our data base. We also ignored those reports that were not considered a fantasy, such as planning the next day or a learnt method to help the transition to sleep, thus 4912 reports remained.

Another forum, titled “Do you ever create fantasy stories in your head before you go to sleep?” (https://forums.digitalspy.com/discussion/1829678/do-you-ever-create-fantasy-stories-in-your-head-before-you-go-to-sleep) involved 22 comments.

Based on the reports of the abovementioned forums, the category system consisted of three main parts: (1) content-based categories, that were established during several meetings with our research team. Based on this, classification of each fantasy report was decided by two of the authors (ASZ and HAA), and inconsistencies, which occurred in 4% of all cases, were decided by a third independent investigator (EÁ), (2) commonly occurring words to detail the fantasy, that were selected by our team after reading through the fantasy descriptions carefully, and their occurrence was calculated using Excel spreadsheets and (3) analyzing the following characteristics: reality of the fantasy; presence of sensory modalities, memories; features of movies, series, books, videogames; temporal aspects: fantasy evolving over time or existing in the past only; playing a main or minor role and being lonely or having company in the fantasy.

The final collection of presleep fantasies contained 4934 reports using the two forums mentioned above. We assumed that commonalities of presleep fantasy content would occur which could provide the base to classification.

Data used in this study was collected from publicly available online platforms. For the protection of user privacy, our results did not contain any identifiable information about the users, and we have complied with the relevant terms and conditions of these platforms. Due to the use of anonymized, publicly available data, and the position of Reddit, that collection of data is not prohibited for academic purposes only (i.e. non-commercial), an ethical approval was not necessary, supported by the statement of the Regional Research Ethics Committee of the University of Pécs (9861 – PTE 2024). Previous studies analyzing online data have followed a similar approach.

Results

Study I

Pittsburgh sleep quality index and glasgow content of thoughts inventory

The mean score of the PSQI questionnaire was 4.199 ± 2.241. Values ranged between 1 and 12. A higher global score indicated poorer sleep quality.

GCTI was listed twice in the questionnaire package presenting the past seven days and the past ten years, respectively. A ten-year period was chosen subjectively, since we assumed this could indicate a relevant picture of sleep habits in the past. The mean score for GCTI showing the past seven days was 25.99 ± 12.25. Values ranged between 0 and 65. Based on the 42-point cut-off, by the GCTI, 24 people fit into the poor sleepers group. Regarding the past 10 years, results seemed similar with 31 individuals in the poor sleepers’ group, mean score was 28.61 ± 11.77.

Fantasizing/creating stories before sleep

Percentages of the extra two questions, respondents reporting fantasizing/creating stories before sleep are presented in Table 1. The majority of the respondents experienced presleep fantasizing on a regular basis.

Table 1.

Prevalence of fantasizing/creating stories during the past 7 days and 10 years.

| Fantasizing | Creating stories | |

|---|---|---|

| Always | 12.4% (12.5%) | 9.6% (9.9%) |

| Often | 21.7% (23.4%) | 12.8% (16.5%) |

| Sometimes | 38.8% (39.1%) | 23.5% (27.8%) |

| Never | 27.1% (25.0%) | 54.1% (45.8%) |

Note. Percentages inside parenthesis refers to the frequency of fantasizing in the last 10 years.

Although it is questionable whether our participants could provide a reliable answer of the past 10 years, we could not exclude the possibility, that we would gain valuable information. According to the results of the past 10 years, they were very similar to the percentages and GCTI scores listed above, therefore we can assume that frequency of fantasizing and creating stories did not change too much during the years.

Spearman correlation analysis

PSQI, GCTI questionnaire scores and fantasizing/creating stories were correlated. The correlation between GCTI and fantasizing/creating stories was significant and correlated positively (R = 0.321, p<0.001; R = 0.304, p<0.001), suggesting that a higher GCTI score coincides with a higher occurrence of presleep fantasizing and creating stories. There was no association between fantasizing/creating stories and PSQI scores.

Study II

Content based category system

Based on content, four main categories and several subcategories (25 in total) were established. Main categories were”: ‘aims and ambitions’, thinking about a ‘calming’ scene, ‘fading away and death’ and if the fantasy did not fit into any of these sections (mostly due to the absence of further details), an ‘other’ category was created. First, two authors (ASZ and HAA) inserted the fantasy reports in the category system. After merging, in the resulting two tables, 4% of all the categorization results were varying. Upon discussion, the differences affected poorly detailed fantasy reports, and their final category was decided by a third, independent author (EÁ). Distribution of the main categories is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Main categories of presleep thoughts based on content.

| Category | Number of presleep fantasies |

|---|---|

| Aims and ambitions | 4409 |

| Calming fantasies | 1039 |

| Fading away and death | 174 |

| Others | 382 |

Majority of the presleep fantasies belonged to the category ‘aims and ambitions’. People shared more or less fictitious wishes and goals like having superpowers, being another character, being able to change the past, monetary reward, love and relationships, sexual fantasy, being successful or meeting celebrities. Contrary to the calming fantasies, respondents here often detailed an exciting, developing storyline. This category mostly involved stories based on positive emotions, but a smaller part of them were negative, anxious or unpleasant fantasies. Some of the reports were not straightforward and not clear enough to understand the content, therefore we included them to more than one category, due to a possible overlap. Table 3. presents the list of subcategories, the prevalence and examples of the reports of ‘aims and ambitions’ category.

Table 3.

Subcategories of category aims and ambitions, prevalence and examples.

| Category | Frequency | Example |

|---|---|---|

|

Being someone else Love, relationship |

1108 546 |

“It’s okay. My fantasy is being Tony Stark.” “So true it hurts. I imagine my ideal relationship” |

| Specific wish | 495 | “Playing football for my favorite team.” |

| Superpower | 473 | “Sometimes what I would do if I had superpowers” |

| Desires in general | 408 | “Being happy” |

| Sexual fantasy | 259 | “Porn. The acting is mind numbing which actually helps me fall asleep.” |

| Receiving an award or monetary reward | 230 | “Winning the lottery!” |

| Accomplishment, success | 197 | “Being an NBA player” |

| Aggression, violence | 191 | “I fantasize of me beating some annoying youngster to oblivion.” |

| Negative, unpleasant situation | 145 | “Getting rejected by everyone I like” |

| Meeting celebrities | 78 | “Usually, some kind of relationship involving my celebrity crush of the day.” |

| Being able to change the past | 80 | “That I will wake up the next morning ten years old again in 1993 with all of the knowledge I currently have.” |

| Powerful, influential position | 71 | “Being a God in another world. I love being a god.” |

| Plans for the future | 58 | “What the house my future family and I have will look like; I imagine it being very cozy!” |

| Freezing the moment | 35 | “I like to imagine all people on earth get paused, except for me. Then, I go explore.” |

| People reacting to the narrator’s funeral | 21 | “How would people react if I died.” |

| Meeting deceased people | 14 | “Seeing my dad one last time….” |

The second most frequent category was imaging a calming, relaxing situation. A calming situation appearing in the fantasy indicated an undisturbed, peaceful scene mainly associated with loneliness. It appeared in different forms, depending on whether it took place in an open (e.g. forest) or closed (e.g. cave) space, or involved a relaxation technique („I usually imagine with every exhale I’m sinking into the ground more and more and I feel myself becoming a part of the earth.”). Table 4. shows subcategories within the calming situations.

Table 4.

Subcategories of calming presleep fantasies.

| Category | Number of presleep fantasies |

|---|---|

| Open space | 313 |

| Relaxation | 189 |

| Isolation | 175 |

| Outside danger | 162 |

| Post apocalypse | 110 |

| Closed space | 43 |

| Survival | 28 |

| Last person on Earth | 19 |

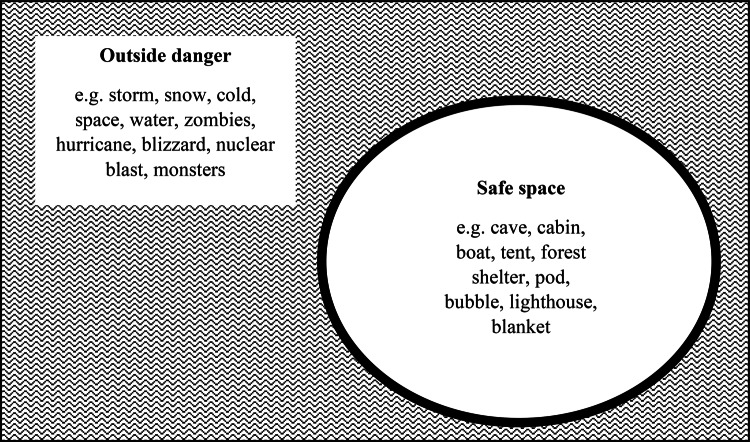

Based on commonalities, these categories could be divided into further sections: some respondents placed the relaxing fantasy in a post-apocalyptic situation, representing complete isolation (e.g., “Zombie outbreak starts and I gather the family and meet my loved ones at the bunker/armory.”). We created a subcategory, where loneliness is especially noted: ‘last person on Earth’ with the extinction of all other humans on the planet (e.g., “I would the last person on earth and hop on any car id like and drive alone on the freeways for hours at a time and have some fun alone.”). If the fantasy took place somewhere closed, it represented not only calmness but also safety (e.g., „My go-to fantasy for some reason has always been just me sipping on hot chocolate late at night in the O’Hare International Airport all alone. Usually, I think of soothing jazz music playing too.”), and it involved a class where a danger source also occurred (Fig. 1). Origin of the danger appeared in different forms: it could be a raging thunderstorm, dinosaurs, the space or a stormy sea. Manifestation of safety varied too: it appeared to be a cave, tent, space pod or submarine (e.g., “The veranda on a log cabin in the forest, by a lake. It’s raining. We have an outdoor heater burning, wrapped in blankets.”).

Fig. 1.

Schematic presentation of subcategory ‘outside danger’ belonging to the first-order category, ‘calming fantasies’. Note: This figure demonstrates examples of danger sources and safe place choices within the subcategory ‘outside danger’.

A less frequent, but separable topic included death-related thoughts and fading away. These fantasies were mostly short, straightforward thoughts, or could be more complex fantasies (e.g.,” (…) I just get this creeping cold down my spine and feel like death and think about how when we die there is nothing and everything is worthless and then I snap back to reality, and either do it again or pass out”). Interestingly, some of these death-related thoughts were not associated with negative feelings, but with peaceful ones (“I dream of a small asteroid the size of a bus speeding towards earth. it loses most of its size in the atmosphere and when its hits earth, it hits exactly me and only me. Everything I own and was eradicated in an instant and I felt nothing. The thought calms me.”).

If none of the categories mentioned above were suitable for the presleep thoughts, we put them into an ’other’ category. Most of these reports were too shortly defined to be understood (“Dogs. Literally just dogs or ants.”).

List of commonly occurring words describing presleep fantasies

Besides the categories, we also calculated the occurrence of a few selected words to describe a fantasy content. We selected words which are aligned with the content-based category system. Therefore, we reviewed the context of the inspected word, and removed it if the respondent did not use it in a certain meaning (e.g., ‘space’ can describe a location, that can be indefinite and the cosmic space too, which we were looking for). ‘Space’ was the most frequently occurring word, mostly to explain a relaxing, isolated situation far from everyone else. ‘Hero’ was also used commonly to express ambitions such as playing the main role in a heroic action, being able to get revenge or constructing an exciting storyline (“Being a Robin Hood type anti-hero in a superhero story where I save the world by robbing banks. It’s kinda lame but it’s fun to imagine.”). The word ‘fly’ appeared in different forms. It could be a part of a relaxing (e.g., “That my bed is flying through the night sky. As I drift closer and closer into sleep, I can actually start feeling the sensation of weightlessness and propulsion underneath me, it’s pretty awesome: )”) or a more thrilling fantasy (e.g. “For my entire life, I’ve always gone to sleep with the thought of being able to fly, swooping down and saving people from danger superman-style…”). Table 5. presents the most frequently occurring words.

Table 5.

Prevalence of the most commonly used words to describe presleep fantasies.

| Word | Prevalence |

|---|---|

| Space | 172 |

| Hero | 137 |

| Fly | 133 |

| Lotto/lottery | 129 |

| Apocalyp’ | 112 |

| Kill | 104 |

| Ship | 102 |

| Zombie | 101 |

| Surviving/survival | 96 |

| Forest | 74 |

| Planet | 74 |

| Dark | 68 |

| Mountain | 63 |

| Alone | 63 |

| Beach | 60 |

| Rain | 57 |

| Town | 54 |

| Island | 53 |

Category system based on commonalities

An additional thematic analysis was conducted to isolate the most common traits of fantasy reports as well: (1) whether the content could be real or fictional (2) sensory modalities involved (3) fantasy based on memories (4) fantasy based on movies, series, books or videogames (5) fantasy evolving over time (6) fantasy takes place in the company of others (7) whether the person describing the fantasy played the main role (Table 6).

Table 6.

Classification system of presleep fantasies based on commonalities.

| Category | Number of presleep fantasies | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Real | 2458 | Parts of the fantasy could occur in the real world. |

| Fictional | 2309 | Details of the fantasy could only happen in an imaginary world. |

| Sensory modalities | There are senses mentioned within the description of the fantasy. | |

| 1. Sound | 58 | Noises are highlighted in fantasy descriptions, usually linked to a peaceful scene. |

| 2. Touch | 130 | Respondents imagine something affecting their body. |

| 3. Smell | 12 | Smells are appearing in the fantasy. |

| Based on memories | 81 | Important components of the fantasy are memories, often from childhood. |

| Based on movies, series, books or videogames | 816 | Structure of the imaginary scene is taken from an existing story. |

| Fantasy evolves over time | 315 | Presleep fantasizing have been present for several years and respondents add further details to their fantasy. |

| Used to fantasize | 66 | Respondents usually remember presleep fantasies that are not present anymore. |

| Loneliness | 639 | Presleep fantasy revolves around only the respondent. |

| Company | 1655 | Other people are involved in the fantasy as well. |

| Main role | 4710 | Respondent is the central figure of the narrative. |

| Not part of the fantasy | 119 | Describer is not part of the fantasy storyline. |

Discussion

Presleep fantasizing might be a conscious effort to facilitate the process of falling asleep and a part of a normal routine. However, it has not been systematically investigated before, particularly, the content of those fantasies.

In these two studies our aim was to investigate presleep fantasizing. In the first study, we assessed the occurrence of fantasizing before sleep in a sample of 281 participants. We found that approximately 75% of our sample fantasized or created stories before sleep regularly. Similar results were found in a study of more than 500 individuals, examining the link between cultural beliefs and sleep, where approximately 75% reported daydreaming before sleep, which was also found to be linked with longer sleep duration24. Among our results, there was a positive association between frequency of presleep fantasizing and the GCTI questionnaire score, which represents presleep thoughts insomniac subjects often experience. We did not have information about the contents of these fantasies, but previous studies showed that anxious and guilty characteristics of task-unrelated thoughts might facilitate insomnia in opposition to positive-vivid topics25. The vast majority of participants were women. Previous research has shown that ruminative coping strategies, as a response to stressful events, showed gender differences as early as in adolescence, with women generally more prone to developing depression26,27. This may be a possible explanation for the association between the severity of insomnia and the frequency of fantasizing: since our participants were mostly women, the nature of presleep thoughts may be ruminative.

In the second study, we analyzed almost 5000 presleep fantasy descriptions that were available online. Based on the similar features of them, we isolated distinctive categories. The most common theme of these fantasies was ‘aims and ambitions’, which was about a broad range of underlying desires and reaching more or less reasonable goals. This category contained fantasies that were generally more expressive in terms of storyline, mostly pointing towards personal fulfillment. They may be an imaginative expansion of the current life situation, with practical elements indicating problem solving and plans for the future. Previous research has shown that mental imagery of a desired scene can be beneficial if it contains real-life difficulties to be solved, not only the achievable award28. Romantic and sexual fantasies were reported commonly, which could benefit the relationship29, and were found to be acceptable, as a social norm, regardless of gender30. A lower subset of this category involved aggressive thoughts, which could be associated with rumination and lower well-being31, revenge fantasies might be even destructing32.

Based on our fantasy descriptions, the second most common category involved relaxing and peaceful scenes where they can feel safe and unharmed. This sort of fantasy descriptions referred to self–soothing directly (e.g., “Since I was a kid, I have had a hard time falling asleep (…) I imagine I’m falling into my bed, like you’re on your back in the pool and sink down to the bottom. But it is just darkness and I’m floating downward and I see the bed and the hole I made above me growing distant. That is when I enter my dreams.”) or indirectly, suggesting the contributing role to sleep quality.

In our sample, negative fantasies were illustrated less frequently, although smaller but not negligible fantasies were classified under the sub-theme ‘fading away and death’. This category included fantasies, in which death also illustrated peaceful content, and not necessarily just suicidal thoughts. This is supported by research findings that suicidal fantasies are associated with detailed suicidal dispositions rather than vague fantasies33.

Emotions associated with presleep thoughts might influence the development of insomnia, although only a few studies analyzed the quality of presleep cognitive activity. Most of the literature focuses on how anxiety, rumination and worry at bedtime lead to cognitive hyperarousal and have a negative impact on sleep. Thus, these ruminative thoughts are strongly associated with insomnia. Insomniac people tend to have worrisome thoughts before sleep, they are often concerned about their general mental state or even about the sleep process34. Presleep thoughts of insomniac people revolve around topics like trivial thoughts, bodily sensations and concerns about work, family and sleep35. Further discovery of these findings, influencing cognitive activity and transform thoughts to positive emotions, could be an efficient way to prevent or relieve symptoms of insomnia2.

Internet use before bedtime in adolescents is associated with poorer sleep quality36. The causal relationship between technology use and sleep problems has been shown in many studies, but the underlying mechanism is still uncertain37. Internet use might interfere with presleep cognition, influences the content of fantasies and therefore disturbs the normal process of falling asleep, this could be a new way to approach sleep difficulties.

There are limitations of our studies that should be considered. Controversies of terminology makes it difficult to compare findings. In the literature we found several terms (such as mind wandering, daydreaming or fantasy) to the occurrence of task-unrelated thoughts that are disengaged from the external stimuli. They are often used as synonyms, and it is not clear if there is any difference between them38. In the last decade, the word “mind wandering” started to appear more frequently in scientific papers, slowly replacing “daydreaming” and “fantasy”39. In this article we refer to the above-mentioned phenomena as a collective term, “fantasy”, as a more conscious form of thoughts, as opposed to mind wandering which reflects a more spontaneous drift of thoughts. Future research should also focus on using a consistent terminology. In Study II, we collected presleep fantasy descriptions and it was not part of the original question whether the fantasizing is common so it could be possible that people’s fantasies alter depending on external factors such as a stressful day, which we unfortunately could not assess. This would be avoidable with supplementary questionnaires. It is also complicated to separate presleep fantasies, since they mostly overlap in topic, therefore it is difficult to choose the right category for them. In this study, three individuals of our research team evaluated independently the content of the fantasies, however, future studies would be able to strengthen the category system.

We hypothesized that positive thoughts may contribute to a better sleep quality, so a future direction could be to instruct patients to actively fantasize about a particular content, which is strengthened by the result of no association between the PSQI score and the frequency of presleep fantasizing. However, this assumption needs to be confirmed by future studies, as other studies on fantasy analysis are scarce.

In conclusion, we found that cognitive activity before sleep in a form of fantasizing seems to be a common phenomenon. As the results of Study II suggest, a categorization spreadsheet could be created based on the similar fantasy patterns of different people, it would be practical to assess the relationship between different categories and sleep quality. It may be important to distinguish between positivity-filled and negative fantasies that may contribute to insomnia, as this aspect is rarely addressed in insomnia studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

JJ, ASz, GD, RH and ASz were involved in developing the hypothesis and study design. ASz, GD and ÁA assembled the questionnaire packages and summarized the results. ASz, EÁ and AHA evaluated the fantasy descriptions and their categorization. ASz wrote the main manuscript body. JJ, NK, RH, ASz, BD and DG revised the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

During this study, all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Based on the official statement of the Regional Research Ethics Committee of the University of Pécs (9861 – PTE 2024) an Ethical Approval was not necessary for this study. Using this questionnaire was considered safe, as all data were collected anonymously. With completing the online questionnaire, applicants voluntarily took part in this study, and an informed consent was obtained from all participants. Regarding Study II, data was collected from publicly available online platforms. For the protection of user privacy, our results did not contain any identifiable information about the users, and we have complied with the relevant terms and conditions of these platforms. Due to the use of anonymized, publicly available data, and the position of Reddit, that collection of data is not prohibited for academic purposes only (i.e. non-commercial), an ethical approval was not necessary, supported by the statement of the Regional Research Ethics Committee of the University of Pécs (9861 – PTE 2024). Previous studies analyzing online data have followed a similar approach.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lichstein, K. L. & Rosenthal, T. L. Insomniacs’ perceptions of cognitive versus somatic determinants of sleep disturbance. J. Abnorm. Psychol.89, 105–107 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemyre, A., Belzile, F., Landry, M., Bastien, C. H. & Beaudoin, L. P. Pre-sleep cognitive activity in adults: A systematic review. Sleep. Med. Rev.50, 1–13 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wuyts, J. et al. The influence of pre-sleep cognitive arousal on sleep onset processes. Int. J. Psychophysiol.83, 8–15 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMillan, R., Kaufman, S. B. & Singer, J. L. Ode to positive constructive daydreaming. Front. Psychol.0, 626 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kane, M. J. & McVay, J. C. What mind wandering reveals about executive-control abilities and failures. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci.21, 348–354 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carciofo, R., Du, F., Song, N. & Zhang, K. Mind wandering, sleep quality, affect and chronotype: An exploratory study. PLoS One. 9, e91285 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindquist, S. I. & McLean, J. P. Daydreaming and its correlates in an educational environment. Learn. Individ Differ.21, 158–167 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schooler, J. W. et al. Meta-awareness, perceptual decoupling and the wandering mind. Trends Cogn. Sci.15, 319–326 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baars, B. J. Spontaneous repetitive thoughts can be adaptive: Postscript on mind wandering. Psychol. Bull.136, 208–210 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mooneyham, B. W. & Schooler, J. W. The costs and benefits of mind-wandering: A review. Can. J. Exp. Psychol.67, 11–18 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shepherd, J. Why does the mind wander? Neurosci. Conscious. (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Seli, P., Risko, E. F., Smilek, D. & Schacter, D. L. Mind-wandering with and without intention. Trends Cogn. Sci.20, 605–617 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giambra, L. M. A Laboratory method for investigating influences on switching attention to task-unrelated imagery and thought. Conscious. Cogn.4, 1–21 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, E. J. & Dimsdale, J. E. The effect of psychosocial stress on sleep: A review of polysomnographic evidence. Behav. Sleep. Med.5, 256–278 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vandekerckhove, M. et al. The role of presleep negative emotion in sleep physiology. Psychophysiology48, 1738–1744 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fairholme, C. P., & Manber, R. Sleep emotions, and emotion regulation. In sleep and affect 45–61 (Elsevier, 10.1016/B978-0-12-417188-6.00003-7. (2015).

- 17.Wicklow, A. & Espie, C. A. Intrusive thoughts and their relationship to actigraphic measurement of sleep: Towards a cognitive model of insomnia. Behav. Res. Ther.38, 679–693 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guastella, A. J. & Moulds, M. L. The impact of rumination on sleep quality following a stressful life event. Pers. Individ Dif. 42, 1151–1162 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morin, C. M., Rodrigue, S. & Ivers, H. Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosom. Med.65, 259–267 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck, J., Loretz, E. & Rasch, B. Exposure to relaxing words during sleep promotes slow-wave sleep and subjective sleep quality. Sleep44, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Peddinti, S. T., Ross, K. W. & Cappos, J. ‘On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog’: A twitter case study of anonymity in social networks. In Proceedings of the second ACM conference on Online social networks 83–93 doi: (2014). 10.1145/2660460.2660467

- 22.Takács, J., Bódizs, R., Ujma, P. P. & Horváth, K. Reliability and validity of the Hungarian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-HUN): Comparing psychiatric patients with control subjects. Sleep. Breath. 1045–1051. 10.1007/s11325-016-1347-7 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Harvey, K. J. & Espie, C. A. Development and preliminary validation of the Glasgow Content of thoughts Inventory (GCTI): A new measure for the assessment of pre-sleep cognitive activity. Br. J. Clin. Psychol.43, 409–420 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arslan, S. Cultural beliefs affecting sleep duration. Sleep. Biol. Rhythms. 13, 287–296 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Starker, S. & Hasenfeld, R. Daydream styles and sleep disturbance. J. Nerv. Ment Dis.163, 391–400 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jose, P. E. & Brown, I. When does the gender difference in rumination begin? Gender and age differences in the use of rumination by adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc.37, 180–192 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mezulis, A. H., Abramson, L. Y. & Hyde, J. S. Domain specificity of gender differences in rumination. J. Cogn. Psychother.16, 421–434 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oettingen, G. & Psychology, K. R. S. and P. & undefined. The power of prospection: Mental contrasting and behavior change. Wiley Online Library10, 591–604. (2016).

- 29.Birnbaum, G. E., Kanat-Maymon, Y., Mizrahi, M., Recanati, M. & Orr, R. What fantasies can do to your relationship: The effects of sexual fantasies on couple interactions. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull.45, 461–476 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Busch, T. M. Perceived acceptability of sexual and romantic fantasizing. Sex. Cult.24, 848–862 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poon, K. T. & Wong, W. Y. Stuck on the train of ruminative thoughts: The effect of aggressive fantasy on subjective well-being. J. Interpers. Violence. 36, 6390–6410 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lillie, M. & Strelan, P. Careful what you wish for: Fantasizing about revenge increases justice dissatisfaction in the chronically powerless. Pers. Individ. Dif.. 94, 290–294 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crabb, P. B. The material culture of suicidal fantasies. J. Psychol.139, 211–220 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fichten, C. S. et al. Role of thoughts during nocturnal awake times in the insomnia experience of older adults. Cogn. Therapy Res.25, 665–692 Preprint at (2001). 10.1023/A:1012963121729

- 35.Watts, F. N., Coyle, K. & East, M. P. The contribution of worry to insomnia. Br. J. Clin. Psychol.33, 211–220 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Geurts, S. M., Bogt, T., van der Rijst, T. F. M., Koning, I. M. & V. G. & Social media use and adolescents’ sleep: A longitudinal study on the protective role of parental rules regarding internet use before sleep. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 1–13 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gradisar, M. et al. The sleep and technology use of Americans: Findings from the National Sleep Foundation’s 2011 Sleep in America Poll. J. Clin. Sleep Med.9, 1291–1299 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christoff, K. Undirected thought: Neural determinants and correlates. Brain Res.1428, 51–59 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Callard, F., Smallwood, J., Golchert, J. & Margulies, D. S. The era of the wandering mind? Twenty-first century research on self-generated mental activity. Front. Psychol.4, 891 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.