ABSTRACT

Immigration is among the most pressing issues of our time. Important questions concern the psychological mechanisms that contribute to attitudes about immigration. Whereas much is known about adults’ immigration attitudes, the developmental antecedents of these attitudes are not well understood. Across three studies (N = 616), we examined US children's attitudes toward migrants by introducing them to two novel groups of people: one native to an island and the other migrants to the island. The migrants varied by (1) Migrant Status: migrants came from a resource‐poor island (fleers) or a resource‐rich island (pursuers); and (2) Acculturation Style: migrants assimilated to the native culture (assimilated) or retained their original cultural identity (separated). We studied a range of children's immigration attitudes: children's preferences, resource allocations, and perceptions of solidarity between groups (Experiment 1), children's conferral of voting power (Experiment 2a) and political representation (Experiment 2b), and children's beliefs about political representation when an equal government was not possible (Experiment 3). Overall, children showed a bias toward natives, but the degree of their bias depended on the type of migrant they were evaluating. Children generally favored Pursuers over Fleers, and Assimilated migrants over Separated migrants. In some cases, the intersection of these factors mattered: children expressed a specific preference for Separated Pursuers and a specific penalization of Separated Fleers. These studies reveal the early developmental roots of immigration attitudes, particularly as they relate to political power and the intersecting forces of migrant status and acculturation.

Keywords: acculturation, development, immigration, politics, status

1. Introduction

“It's our right as a sovereign nation to choose immigrants that we think are the likeliest to thrive and flourish and love us.” ‐ Donald J. Trump, 45th & 47th President of the United States of America.

Immigration remains an omnipresent global policy issue that continues to dominate national and international headlines. Today, more people than ever live in a country other than the one in which they were born. In 2020, the number of international migrants reached 281 million, with refugees accounting for 10% of this population (United Nations 2020). Over the last decade, 7 million Syrians, 6 million Venezuelans, and 6 million Palestinians have been expelled from their homeland. In 2022, in 1 month alone, 4 million Ukrainians fled their country. In light of increased attention to global migration and as governments experiment with new immigration policies, the global community has observed a steep rise in anti‐immigrant sentiment, with citizens across many countries becoming increasingly intolerant of migrants (Gallup 2020).

Summary

We explored the developmental antecedents of immigration attitudes by testing children's abstract reasoning about migrants in a fictional context.

We examined children's attitudes, resource allocations, and conferral of political power and representation to fictional groups who were depicted as natives or migrants.

Children evaluated island natives more favorably than island migrants, yet their attitudes varied in systematic ways depending on migrants’ origins and assimilation style.

Children showed a bias toward migrants who came from resource‐rich origins and migrants who assimilated into the natives’ culture.

A large swathe of research on the psychology of migrant attitudes in adults has focused on unpacking these negative attitudes toward immigrants. This series of inquiries, conducted across nations, reveals that the valence and strength of people's attitudes toward immigrants are impacted by a host of factors, such as threat sensitivity (Dinas and van Spanje 2011; Mustafaj et al. 2022), political ideology (Cohrs and Stelzl 2010; Saldaña, Cueva Chacón, and García‐Perdomo 2018), and media coverage of immigration (Eberl et al. 2018; Farris and Silber Mohamed 2018; Fryberg et al. 2012). These findings demonstrate that adults have deep‐rooted and complex beliefs about immigrants and that these attitudes are shaped by the sociocultural environment. However, it is unclear how and when in development these views about immigration take root—do young children have intuitions about whether immigrants should or should not have the same rights as native‐born people? How do these intuitions change with age? A developmental perspective serves as a powerful tool to understand the building blocks of immigration attitudes and helps constrain hypotheses about the kinds of inputs that are necessary to form these intuitions. We investigated children's immigration attitudes across a wide range of variables: children's preferences, resource allocations, and perceptions of solidarity between groups (Experiment 1), conferral of voting power (Experiment 2a), political representation (Experiment 2b), and beliefs about political representation when an equal government was not possible (Experiment 3). Through this research program, we uncover nuance in children's reasoning about immigration, highlighting the penalties and privileges afforded to different kinds of migrants.

1.1. The Psychology of Immigration Attitudes

Research on immigration attitudes is vast and spans different disciplines within the social sciences. Myriad factors influence people's immigration attitudes, such as person‐level (Espenshade and Hempstead 1996; Garand, Xu, and Davis 2017), regional (Markaki and Longhi 2013), and psychological factors (Chandler and Tsai 2001; Hainmueller and Hopkins 2014). Importantly, extant research finds that people's immigration attitudes can depend greatly on their perception of different aspects of the migrant groups (e.g., Berry 1980; Robertson 2019; Verkuyten 2005). Two important dimensions that have been found to powerfully shape adult intuitions are migrant status (e.g., whether a migrant is a refugee or voluntarily immigrating) and acculturation style (e.g., whether a migrant assimilates to the host culture or does not). Research with adults suggests that both dimensions affect the way host majorities (i.e., countries that take in migrants) perceive migrants and introduce a theoretically rich distinction for how to conceptualize different categories of migrants.

Migrant status refers to the legal status of migrants in a new country (Robertson 2019). Research on migrant status with adults has focused on the difference between immigrants (i.e., voluntary resettlement) and refugees (forced resettlement; Abdelaaty and Steele 2022; De Coninck 2020). For example, Dutch participants were more likely to support policies associated with cultural rights and public assistance for migrants they perceived as “involuntary” than “voluntary”; these authors found that involuntary immigrants elicited more feelings of sympathy from Dutch participants, and therefore higher support (Verkuyten, Mepham, and Kros 2018). Yet people's ostensible support for refugees over immigrants may be because refugees are perceived as more likely than immigrants to assimilate into the natives’ culture (e.g., Gieling, Thijs, and Verkuyten 2011).

Acculturation style refers to the relative degree to which migrants assimilate. Berry's acculturation model posits different strategies migrant groups might adopt in relation to a host culture, ranging from assimilation (a preference for the host culture without the maintenance of the heritage culture) to separation (a preference for the heritage culture without adopting the host culture; Berry 1980; Berry et al. 1997). Host majorities across several different countries often prefer migrants who assimilate (Van Oudenhoven, Prins, and Buunk 1998; Verkuyten 2005). For example, when fictional immigrant acculturation preferences were manipulated, Italian participants were more favorable to immigrants who desired contact with host populations than those who did not (Matera, Stefanile, and Brown 2011).

1.2. Children's Immigration Attitudes

The developmental antecedents of migrant attitudes have largely been underexamined, leaving open questions concerning the early roots of people's attitudes toward migrants. However, there are threads of relevant research that help to situate the current project within past developmental research.

Research on social categorization in children demonstrates just how early people can reason about social groups. In infancy, as early as 3 months old, children understand that social groups are meaningful markers of people's patterns of social affiliation (Liberman, Woodward, and Kinzler 2017) and preschool‐aged children pick up on group status (Heck, Shutts, and Kinzler 2022). Indeed, children even use social categories to make predictions and inferences about others’ preferences, traits, and behaviors, predicting for example that norms (but not individual psychological states) would generalize across social category membership (Essa et al. 2021; Kalish 2012; Kinzler and Dautel 2012; Nasie and Diesendruck 2020; Noyes and Dunham 2017). With age, children often increasingly endorse more nuanced and intersectional outgroup attitudes (Abrams et al. 2015; Nasie and Diesendruck 2020; Razpurker‐Apfeld et al. 2024; Santhanagopalan et al. 2021). For instance, older children are more likely to recognize that people are multifaceted and differ across dimensions of social category membership. Children's early and increasing sensitivity to different social groups raises questions about how children think about migrants as a social category, what nuanced inferences children may make about different types of migrants, and how this may develop with age. The current research thus extends prior work on children's early attitudes about intergroup relations.

Beyond evidence about children's early social categorization, children also have intuitions about the rights and privileges that extend to owners and first‐arrivers on a piece of land. Children as young as 3 years old believe that people own objects within their territory, even when it was acquired unintentionally or unknowingly (Goulding and Friedman 2018). Other research with 9–12‐year‐olds reveals that children believe first‐arrivals own an island more than a second group of arrivals, even in situations where first‐arrivals leave and second‐arrivals come much later (Verkuyten, Sierksma, and Thijs 2015). Beliefs about ownership and territory may shape children's perceptions of newcomers in their attitudes about who deserves the privileges and resources associated with land, such that children might view established inhabitants as more entitled to these resources and privileges than newcomers. Despite children's early‐emerging beliefs about ownership and territory, children as young as age 3 also endorse strong fairness considerations (Engelmann and Tomasello 2019; Furby 1978; Rizzo et al. 2016). These findings raise questions about the interplay between ownership beliefs and fairness considerations, and how these considerations change with age.

Existing research that is more specifically focused on children's views about immigration, though limited, has typically explored children's attitudes about specific migrant groups. For example, 5–11‐year‐old US children make inferences about people from specific racial and migrant backgrounds: White American children believed that White and Black Americans were richer than Mexican immigrants and children were less likely to want Mexican or Chinese immigrant peers, with younger children generally endorsing stronger attitudes on some measures than older children (Brown 2011). In another study, Verkuyten, Thijs, and Sierksma (2014) found that 8–13‐year‐old Dutch children favored those immigrant peers who adopted Dutch culture compared to those who did not. These findings provide initial evidence that children may be selective in how they evaluate real‐world migrant groups. However, evaluations of groups in the real world are often highly context‐dependent and may vary on several different dimensions which may make children's exact inferences hard to pinpoint and understand with clarity. Furthermore, children may receive explicit messaging or overhear evaluations of specific groups from parents or other adults. Probing children's basic intuitions about migrants may thus require asking their beliefs about novel social groups.

Together, these findings leave several unresolved critical inquiries. First, the adult literature provides evidence that people's beliefs about abstract concepts (e.g., migrant status and assimilation) inform how they process and react to migrants. Yet there is limited research examining the conceptual foundations of these abstract immigration beliefs. That is, little is known about children's conceptual, abstract notions about immigration that do not rely on specific stereotypes. If children only knew of the migrant status and acculturation style of a novel group, would they have any intuitions about how those groups would or should be treated? Second, whereas previous work with children has typically focused on their preferences for specific migrant groups, critical open questions also concern how children's immigration cognition extends to other domains of social life, such as questions of resource entitlement or political power. In this research program, we pursue a comprehensive examination of children's immigration attitudes across a range of domains. By examining these questions across early and middle childhood, we can document the initial stages of these attitudes and track their progression with age.

1.3. Present Studies

Across all studies, we introduced 4–10‐year‐old children to a 2 × 2 between‐subjects factorial design in which we manipulated Migrant 1 Status : Fleer (migrants coming from a resource‐poor island) versus Pursuer (migrants coming from a resource‐rich island) as well as Acculturation Style : Assimilated (migrants adopted the natives’ culture) versus Separated (migrants retained their original cultural identity). Our main research question was how these factors would impact children's evaluations of novel groups of natives and migrants. One possibility is that children would show no bias toward either natives or migrants and that children only have preferences for specific real‐world migrant groups based on stereotypes or ingroup favoritism. Instead, we hypothesized that children would show an overall bias in favor of natives (see related research by Verkuyten, Sierksma, and Thijs 2015 on 9–12‐year‐olds’ bias toward first arrivals) and that this bias would emerge even earlier than has previously been examined. We made this prediction based on related work on ownership that suggests children by age 4 or 5 show fairly strong first‐possessor and object history biases (e.g., Friedman et al. 2013), and even nuanced attitudes about novel and real social groups (Heck, Shutts, and Kinzler 2022). In addition, we anticipated that the degree of children's preferences for natives would vary depending on the type of migrant they were evaluating. Specifically, based on the literature reviewed above, we hypothesized that children would not treat all migrants equivalently, which would provide insight into the conceptual building blocks of immigration attitudes that may go beyond a simple heuristic of preferring “native” to “foreigner.”

In addition to investigating if these dimensions matter to children, one additional advantage to the current studies is that we probed children's evaluations across a number of different important dependent variables. In Experiment 1, we examined children's attitudes across: (1) preferences between natives and migrants, (2) beliefs about resource entitlement between natives and migrants, and (3) perceptions of solidarity between natives and migrants. In Experiments 2a and 2b, we expanded our investigation of children's immigration attitudes by focusing on the consequential political arena, examining how children confer voting power and political representation to natives and migrants. In Experiment 3, we probed this further by asking children who should be and who would actually be elected to government with a choice between a member of the native or migrant group. Together, these studies document the emergence and development of children's immigration attitudes, with a focus on the independent and intersecting roles of migrant status and acculturation style.

2. Experiment 1

In Experiment 1, we examined a range of children's immigration attitudes: children's preferences, choice of leader, resource allocations, and perceptions of solidarity between natives and migrants. We introduced children to two novel groups of people living on an island: island natives and island migrants. Migrants varied on two dimensions between‐subjects: (1) Migrant Status: Fleer versus Pursuer and (2) Acculturation Style: Assimilated versus Separated. We predicted that children would prefer natives over migrants generally, but that children's endorsement of migrants may vary in relation to these two dimensions we manipulated.

2.1. Methods

The data and code that support the findings of all studies are available on OSF: https://osf.io/xzgcw. Studies were not pre‐registered. Experiments were approved by the university's IRB. The legal guardians of all participants provided written informed consent, and children provided verbal assent.

2.1.1. Participants

We recruited 224 children (112 girls, 112 boys) between the ages of 4 and 10 years old (M age = 89 months; SD = 24 months). Across studies, there were an equal number of participants in all four cells of our design (e.g., here 56 participants per cell). We chose this lower end (i.e., 4‐year‐olds) based on previous work on children's ownership beliefs and social group attitudes (Friedman et al. 2013; Friedman and Neary 2008; Heck, Shutts, and Kinzler 2022) to document just how early children display distinct attitudes toward migrants and how these attitudes look across early and middle childhood. Examining a wide age range is advantageous because children form strong social attitudes early in development, but the expression and sophistication of this understanding may develop substantially across early childhood. Participants were tested in a quiet room in the lab, at a preschool, or in a children's museum in the Northeastern US. Parents of participants had the option of providing demographic information at the end of the consent form. Race and ethnicity were provided for 75% of participants. Parents selected from a list of races (with the option to select multiple races), and could also input their own racial categories if none of them applied. Among those who reported this information 4% identified as Asian or Asian–American, 6% identified as Black/African American, 72% identified as European or European–American, 4% identified as Hawaiian, 2% identified as Hispanic/Latine, and 12% identified as something else. Gender information was provided for all participants; parents selected from a list of gender identities, with the option to input another gender identity if none of these options applied. Socioeconomic information was provided for 74% of participants, of whom 17% came from families earning between $15,000 and $49,999, 39% came from families earning between $50,000 and $99,999, 21% came from families earning between $100,000 and $150,000, and 23% came from families earning more than $150,000. Participants were compensated with a small toy or stickers, and parents were offered a $10 Amazon gift card.

2.1.2. Procedure and Materials

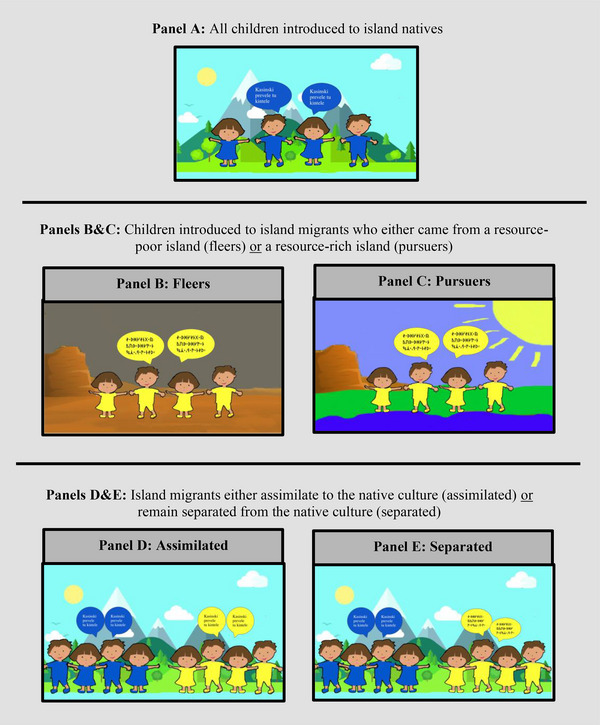

This experiment was conducted by a live experimenter in person. Participants were introduced to a story (a series of still images) about island natives (Grocks) and island migrants (Orops), names counterbalanced. In all conditions, natives lived on a resource‐rich island with plenty of water, sunshine, and food. Between‐subjects, migrants were described as having come from either a resource‐poor island (Fleers) or a resource‐rich island (Pursuers). Natives and migrants spoke their own respective languages and ate their own respective foods (e.g., “These are the Grocks. They speak Grock and eat Grock food”). Next, migrants were described as having left their home island to arrive at the natives’ island. After living on the island for a long time, the migrants either assimilated to the natives’ culture (i.e., adopted the natives’ food and language; Assimilated) or remained separated from the natives’ culture (i.e., retained their original distinct food and language; Separated). This 2 (Migrant status: Fleer vs. Pursuer) × 2 (Acculturation Style: Assimilated vs. Separated) between‐subjects factorial design resulted in four types of migrants: Assimilated Fleer, Separated Fleer, Assimilated Pursuer, and Separated Pursuer − see Figure 1. See Supporting Materials S3 for evidence that children believed resource scarcity was the primary reason Fleers migrated and that curiosity/exploration was the primary reason Pursuers migrated.

FIGURE 1.

2 × 2 factorial design introducing children to four types of migrants: Assimilated Fleers, Separated Fleers, Assimilated Pursuers, and Separated Pursuers.

After the story, participants answered six questions, broadly spanning three domains (in counterbalanced order).

Attitudes: “Who do you like more?” and “Who do you think is the leader?”

Resource Allocation: “There's not enough food on the island, who should get more of the food?” and “There's not enough schools on the island, who should get more of the spots in schools?”

Group Solidarity: “Do the Grocks like the Orops?” and “Do the Orops like the Grocks?”

For all questions, we gave children the explicit option of choosing one, the other, or not differentiating between the two groups. For the Attitudes and Resource Allocation questions, participants were given the option of picking either “the Grocks, the Orops, or both the same.” We offered the “both the same” option to avoid putting children in a position in which they only have the option to express a social bias. For the Group Solidarity questions, participants were given the option of responding “Yes”, No or “I don't know.” After each question, we asked participants to explain their choice. Full scripts for all experiments can be found on OSF.

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Analysis Plan

For each question, we first report children's overall rate of choosing natives or migrants, collapsing across conditions. Next, we constructed binomial logistic regressions with Migrant Status, Acculturation Style, and Age (in months), and their respective interactions, as predictors. Multiple comparisons were addressed using Benjamini‐Hochberg corrections. Next, we separately examined the responses of participants assigned to each condition using binomial exact tests, directly testing children's preferences for natives or migrants within each condition. For some of our measures, children chose the “both the same” option and were not counted as showing bias for either group and were thus excluded from our analyses. Importantly, we note that for each question, children's likelihood of choosing “both the same” did not vary by condition, ps > 0.345 and so any differences we observe in our varied conditions are not the result of differential attrition because of these exclusions.

2.2.2. Attitudes

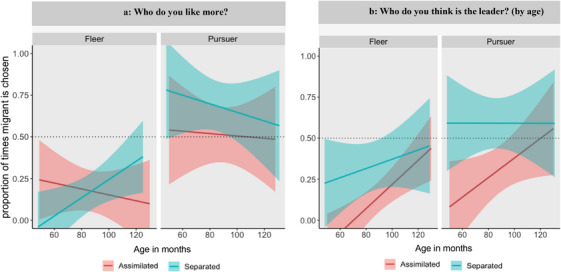

2.2.2.1. Liking

Collapsing across conditions, children liked natives more than migrants, Binomial Exact, p = 0.004. A binomial logistic regression revealed a significant interaction between Migrant Status and Acculturation Style, B = 7.129, SE = 3.438, p = 0.039, such that children showed a bias toward migrants when they were Separated Pursuers (as revealed by post‐hoc comparisons). Post hoc comparisons revealed that children were more likely to like migrants when they were either type of Pursuer than when they were either type of Fleer, ps < 0.003. We also observed an interaction between Acculturation Style and Age; younger children were more likely to favor migrants when they were Assimilated, B = 0.060, SE = 0.030, p = 0.043. Although we observed a marginal main effect of Acculturation Style (p = 0.051) and a marginal 3‐way interaction among Migrant Status, Acculturation Style, and Age (p = 0.054), these were no longer marginally significant when accounting for the significant interactions. No other main effects or interactions were significant, ps > 0.498. Next, we analyzed the responses of participants tested in each condition separately (n = 56 per condition). In line with the regression, in the Separated Pursuer condition, children liked migrants more than natives, Binomial Exact, p = 0.028. In the Assimilated Pursuer condition, children showed no preference, Binomial Exact, p = 1. In both the Assimilated Fleer and Separated Fleer conditions, binomial exact tests indicate that children liked natives more than migrants (i.e., Binomial Exacts, both ps < 0.001)—see Figure 2a.

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of times children chose the native or the migrant across the four conditions when asked who they liked more (2a; left) and who was the leader (2b; right).

2.2.2.2. Leader

Collapsing across conditions, children once again favored natives over migrants, Binomial Exact, p < 0.001. A binomial logistic regression revealed a main effect of Acculturation Style, B = 11.047, SE = 4.892, p = 0.024–children were more likely to choose migrants as leaders when they were Separated compared to Assimilated, and a main effect of Age, B = 0.107, SE = 0.042, p = 0.012–younger children were generally less likely to choose the migrants as leaders. A significant interaction between Acculturation Style and Age revealed that younger children were less likely to believe migrants were leaders when they Assimilated, B = −0.094, SE = 0.044, p = 0.034. Although we observed a marginal main effect of Migrant Status (p = 0.060) and marginal interaction between Migrant Status and Age (p = 0.087), these were no longer marginally significant when accounting for the significant interactions. No other main effects or interactions reached significance, ps > 0.172. As before, we then analyzed each condition separately. In the Separated Pursuer condition, children showed no bias toward either the natives or migrants, Binomial Exact, p = 0.291. Children did however show a native bias in the Separated Fleer, Assimilated Fleer, and Assimilated Pursuer conditions, Binomial Exacts, ps < 0.03–see Figure 2b.

2.2.3. Resource Distribution

Food . Collapsing across conditions, children generally did not show a bias toward either group, Binomial Exact, p = 0.697. However, a binomial logistic regression revealed an interaction between Migrant Status and Age, such that younger children were more likely to believe the migrants should have access to food when they were Pursuers, B = 0.050, SE = 0.025, p = 0.047. Although we observed a main effect of Migrant Status (p = 0.038), this was no longer significant when accounting for the interaction. No other main effects or interactions were significant, ps > 0.116.

Schools . Collapsing across conditions, children favored an equal distribution of schools, Binomial Exact, p = 1. A binomial logistic regression did not reveal significant main effects or interactions, ps > 0.253.

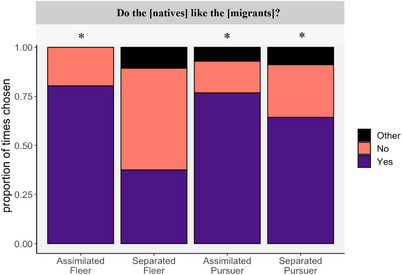

2.2.4. Group Solidarity

Do the (migrants) like the (natives)? Collapsing across conditions, children overwhelmingly believed the migrants liked the natives (i.e., 75% of children responded “Yes”), Binomial Exact, p < 0.001. A binomial logistic regression did not reveal significant main effects or interactions, ps > 0.073. An analysis of each condition separately revealed that children believed the migrants liked the natives across conditions, ps < 0.007.

Do the (natives) like the (migrants)? Children also generally believed the natives liked the migrants, Binomial Exact, p < 0.001 and a binomial logistic regression did not reveal significant main effects or interactions, ps > 0.141, but post hoc pairwise comparisons indicate that children were least likely to believe natives liked Separated Fleers, ps < 0.008. Indeed, looking more closely at each condition, Separated Fleers represented the only migrant condition in which children were equally split between “Yes” and “No,” Binomial Exact, p = 0.322– see Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of times children chose “Yes,” “No” or “Other” when asked whether the natives liked the migrants. Children believed natives liked the migrants in all conditions except when migrants were Separated Fleers. Typographical marks indicate significant binomial exact tests between natives and migrants.

2.2.5. Explanation Coding

We coded children's explanations for general themes (see Supporting Materials S2 for more details). Overall, children provided pro‐native responses 21% of the time, equality‐oriented responses 7% of the time, pro‐migrant responses 5% of the time, and non‐substantive responses 67% of the time. A further examination of children's pro‐native responses revealed four pro‐native themes: (1) natives as saviors; (2) natives as owning the island; (3) natives as having more than the migrants; and (4) natives as being nice.

2.3. Discussion

Overall, across a range of measures, children showed a bias in favor of natives. This both replicates and extends past work, showing that a native bias comes online in early childhood (earlier than has previously been documented) and extends across different domains. Furthermore, this study depicted important nuance in children's beliefs about migrants, discovering that immigration beliefs were influenced by migrant status; children generally favored Pursuers over Fleers, with younger children showing a stronger bias on some measures. Younger children also liked Assimilated migrants more than older children (though they were less likely to believe they were leaders). The intersection of migrant status and acculturation style was also notable—with participants favoring Separated Pursuers and penalizing Separated Fleers. These differential reactions based on intersecting identities highlight children's variable expectations about how migrants should act based on the migrants’ identities.

3. Experiments 2a and 2b

We extended our examination of children's immigration attitudes by focusing on consequential domains of public life: political power (Experiment 2a) and political representation (Experiment 2b). Political leaders wield enormous power to enact laws and governance that not only affect every individual in a society but can also alter deep‐rooted foundational structures that uphold a society. Children's proto‐political attitudes can form the foundation from which adult political behaviors and beliefs can be traced (Heck et al. 2021; Patterson et al. 2019). Thus, in Experiment 2a, we assessed children's attitudes about migrants’ political power across three voting scenarios (Equal, Majority‐Native, and Majority‐Migrant). In Experiment 2b, we investigated children's beliefs about how much political representation migrants should have and actually do have in government. Critically, in this study, we included the option of an equally representative government, which though idealistic, allowed us to better capture children's holistic immigration attitudes.

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants

We recruited 168 children (84 girls, 84 boys) between the ages of 4 and 10 years old (M age = 87 months; SD = 25 months) to participate in this study over Zoom. Race and ethnicity were provided for 60% of participants, of whom 9% identified as Asian or Asian–American, 9% identified as Black or African American, 61% identified as European or European–American, 6% identified as Hispanic/Latine, 1% identified as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 13% identified as mixed race, and 1% identified as something else. Socioeconomic information was provided by 55% of participants, of whom 1% came from families earning less than $15,000, 23% came from families earning between $15,000 and 74,999, 19% came from families earning between $75,000 and $99,999, 23% came from families earning between $100,000 and $149,999, and 34% came from families earning more than $150,000. Participants were compensated with a $5 Amazon gift card.

3.1.2. Procedure and Materials

This experiment was conducted over Zoom. Participants were first introduced to the same between‐subjects story as in Experiment 1 (Migrant Status: Fleer vs. Pursuer) × 2 (Acculturation Style: Assimilated vs. Separated). Then, participants were introduced to the Voting Power task (Experiment 2a) and the Political Representation Task (Experiment 2b) in a randomized order.

In the Voting Power task, participants were presented with four islanders who were voting on a snack (popcorn or chips). In all cases, the natives and migrants had different snack preferences (e.g., the natives wanted popcorn and the migrants wanted chips). The snack paired with each group was counterbalanced such that natives wanted the popcorn for half the trials, and chips for the other half of the trials. Children were introduced to three voting scenarios: (1) Equal: two natives want snack A and two migrants want snack B; (2) Majority‐Native: three natives want snack A and one migrant wants snack B; (3) Majority‐Migrant: one native wants snack A and three migrants want snack B. Children were told that the four islanders could choose only one snack for all of the islanders to share and were asked what they thought should happen, with a binary choice between the native‐preferred snack and the migrant‐preferred snack. We implemented a binary response to impose a realistic constraint on children's voting choices, more closely mirroring real‐world choices.

In the Political Representation task participants were presented with an election scenario in which the islanders were getting ready to elect a new government. Children were presented with five options for the new 12‐person government: Large‐Majority‐Native (10 natives, 2 migrants), Slight‐Majority‐Native (8 natives, 4 migrants), Equal (6 natives, 6 migrants), Slight‐Majority‐Migrant (4 natives, 8 migrants), and Large‐Majority‐Migrant (2 natives, 10 migrants). We provided the option of an Equal government to examine children's responses void of realistic constraints. These options were counterbalanced such that half of the participants saw the Majority‐Native government on the left, and the other half of the participants saw the Majority‐Migrant government on the left. Participants selected which government they thought should and would actually be elected, in counterbalanced order.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Voting Power (Experiment 2a)

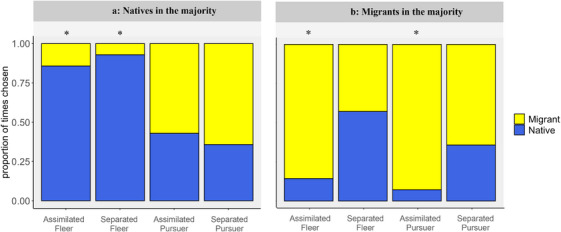

In the Equal Scenario (i.e., two natives want snack A and two migrants want snack B), children were equally likely to choose natives or migrants (not different from chance, p = 0.410). Otherwise, children favored whichever group had majority status, Binomial Exact, ps < 0.044. Evaluating the whole sample (N = 168), we constructed a binomial logistic regression with Migrant Status, Acculturation Style, and Scenario (Equal, Majority‐Native, and Majority‐Migrant). We pursued post hoc analyses using emmeans (note multiple comparisons were addressed using Benjamini‐Hochberg corrections). We end with binomial exact tests. We did not include Age as a predictor in the main model due to power considerations (12 between‐subjects conditions); separate age analyses revealed no significant age effects, ps > 0.42.

The regression revealed a significant main effect of Scenario, B = 3.584, SE = 1.080, p < 0.001; children were less likely to choose the migrants when the natives were in the majority compared to both other scenarios, ps < 0.012. We also observed an interaction between Acculturation Style and Scenario, B = −2.380, SE = 1.216, p = 0.050; when migrants were in the majority compared to when migrants were equal or in the minority, children showed a stronger bias in favor of migrants who assimilated, ps < 0.017. Although we observed a main effect of Acculturation Style (p = 0.026), this was no longer significant when accounting for the interaction. No other main effects or interactions were significant, ps > 0.108.

Native‐Majority Scenario . Binomial exact tests for each condition (n = 42 per condition) generally confirm the trends in Migrant Status and Acculturation Style noted above, offering additional insight. Children chose natives over both types of Fleers (ps < 0.013), but were equally split between natives and both types of Pursuers (ps > 0.424)—see Figure 4a. Migrant‐majority scenario . Binomial exact tests for each condition (n = 42 per condition) revealed that children adhered to the migrant‐majority for both types of Assimilated migrants (ps < 0.013), but were equally split between preferring natives and migrants for both types of Separated migrants (ps > 0.424)—see Figure 4b.

FIGURE 4.

Proportion of times children chose to side with the native(s) or migrant(s) when natives were in the majority (4a; left) and when migrants were in the majority (4b; right). Typographical marks indicate significant binomial exact tests between natives and migrants.

3.2.2. Political Representation (Experiment 2b)

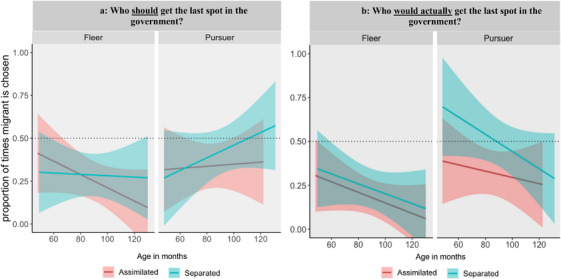

Overall, 64% of children believed an Equal government should be elected and 50% of children believed an Equal government would actually be elected. However, children were also more likely to believe a Majority‐Native government should be chosen than a Majority‐Migrant government, Binomial Exacts, p = 0.013 (should) and p < 0.001 (would actually). With our full sample (N = 168), we constructed an ordinal logistic regression with Migrant Status, Acculturation Style, Age, and Question (and their interactions) as our main predictors in children's choice of a government (large‐majority native, slight‐majority native, equal, slight‐majority migrant, and large‐majority migrant). We observed a 4‐way interaction, B = −0.071, SE = 0.036, p = 0.044. With age, children were more likely to elect the migrant into government when they were Separated Pursuers. Post hoc pairwise comparisons additionally reveal that children generally preferred to elect migrants who were Pursuers over Fleers, p < 0.001, and migrants who Assimilated than those who Separated, p = 0.043. Notably, children were least likely to believe migrants should and would actually be elected into government when they were Separated Fleers, ps < 0.037. Indeed, binomial exact tests within each condition, indicate that children showed the strongest native‐majority bias in the Separated Fleer condition, Binomial Exact, ps < 0.001. Note that the significant 2‐way interaction between Question and Migrant Status, and 3‐way interaction between these variables and Age, were no longer significant when accounting for the 4‐way interaction. No other main effects or interactions were significant, ps > 0.055.

3.3. Discussion

Overall, children showed a preference for natives in their conferral of voting power. Interestingly, children's choices varied based on which group had majority status. When natives were in the majority (i.e., where we might expect a preference for natives), children showed a native bias when migrants were Fleers, but not when migrants were Pursuers. This finding resembles a similar pattern found in Experiment 1, where children showed a general preference for Pursuers over Fleers. On the other hand, when migrants were in the majority (i.e., where we might expect a preference for migrants), children were most likely to show a pro‐migrant bias for Assimilated migrants, compared to Separated migrants. Children were least likely to show a pro‐migrant bias when migrants were Separated Fleers and even showed some evidence of favoring Separated Pursuers. When neither group was in the majority, children did not show a bias toward natives nor migrants.

In line with our resource allocation results from the previous study, children's beliefs about political representation tended toward endorsing an equal government. Children's general preference for an equal government may be explained by an early proclivity toward fair and equitable outcomes (Blake et al. 2015; McAuliffe et al. 2017; Shaw and Olson 2014). However, as they have on many of our measures, children treated Separated Fleers as less preferred. When deciding who should and who would actually be elected to the government, children were more likely to favor a native‐majority government when migrants were Separated Fleers, highlighting the penalty conferred upon migrants coming from resource‐poor islands who do not assimilate. Children also showed signs of favoring Separated Pursuers, believing they should be elected into government, and this observation increased with age.

Experiment 2b relied on a stylized paradigm aimed to elicit children's broader attitudes about political representation and revealed that children showed an affinity toward an equally representative government. That said, we also observed initial indications of children's selectivity in who they would elect to govern: children were more likely to elect a majority‐native government than a majority‐migrant government, and children were less likely to elect Separated Fleers and more likely to elect Separated Pursuers into government. In Experiment 3, we further probed these findings by exploring a more realistic scenario in which a perfectly equal government was not possible.

4. Experiment 3

Experiment 2b explored children's holistic and abstract immigration attitudes void of real‐world constraints, whereas Experiment 3 explored whether adding these real‐world constraints alters children's responses. Children were presented with a binary choice between electing an island native or an island migrant. Children were asked who should and who would actually be elected to the government.

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. Participants

We tested 224 children (111 girls, 113 boys) between the ages of 4 and 10 years old (M age = 89 months; SD = 24 months) over Zoom. Race and ethnicity were provided for 71% of participants, of whom 8% identified as Asian or Asian–American, 9% identified as Black/African American, 56% identified as European or European–American, 5% identified as Hispanic/Latine, 16% identified as mixed‐race, and 4% identified as something else. Socioeconomic information was provided for 71% of participants, of whom 2% came from families earning less than $15,000, 9% came from families earning between $15,000 and $49,999, 41% came from families earning between $50,000 and $99,999, 26% came from families earning between $100,000 and $150,000, and 22% came from families earning more than $150,000. Participants were compensated with a $5 Amazon gift card.

4.1.2. Procedure

This experiment was conducted over Zoom. As in Experiments 1 and 2, children were first introduced to the same story in a 2 (Migrant Status: Fleer vs. Pursuer) × 2 (Acculturation Style: Assimilated vs. Separated) between‐subjects design. Next, participants were introduced to the island's current government, which was comprised of an equal number of natives and migrants. Children were told that there was an impending election with the option of electing either a native or migrant into the last spot in the government. Children were asked who should and who would actually be elected to the position (order of questions counterbalanced). After children made their choice, we randomly assigned children to a newly elected government which was either majority‐native or majority‐migrant. We asked children whether it was fair for those in the minority to complain with a binary choice of “Yes” or “No,” followed by the degree to which it was fair or unfair (e.g., is it kind of [un]fair or really [un]fair for them to complain)?

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Election Trial

When asked who should and who would actually be elected into the government, children showed a bias in favor of natives, selecting natives into the government 69% of the time and selecting migrants into the government 31% of the time (above chance, p < 0.001). On our whole sample (N = 224), we constructed a binomial logistic regression with Migrant Status, Acculturation Style, Age (in months), and Question (and their interactions) as our main predictors. We observed a significant interaction between Migrant Status and Age. Younger children were more likely to elect migrants into government when they were Pursuers, B = 0.040, SE = 0.019, p = 0.042. Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that children were more likely to elect migrants when they were Separated Pursuers compared to all other migrant types, ps = 0.034, a pattern of findings that was stronger when deciding who would actually be elected into government. No other main effects or interactions were significant, ps > 0.067. Next, we examined each condition separately (n = 56 per condition for each question). Children showed a preference to elect natives in all conditions (ps < .022), except in the Separated Pursuer condition (not different from chance, Binomial Exact, p = 0.350 and p = 0.894, for who should and would actually be elected, respectively)—see Figures 5a and b. As a secondary question of interest, we asked children how fair it would be for the minority group to complain (n = 28 per unique condition). Regardless of whether children were considering a native‐majority or migrant‐majority government, children (67%) largely believed that it was unfair for the group in the minority to complain (above chance, Binomial Exact p < 0.001).

FIGURE 5.

Proportion of times children chose the native or migrant by age for who should (5a; left) and would actually (5b; right) be elected to the government.

4.3. Discussion

Children demonstrated a bias in favor of natives in their choice of who should and would be elected to the government. Of note, this native bias was again selective: children were equally likely to select a native or a migrant when the migrants were Separated Pursuers. These findings highlight the uniquely favorable attitudes children have about resource‐rich migrants, particularly those who remain separated from the natives’ culture. The current findings demonstrate that when realistic constraints are added to a voting scenario, children show a bias in favor of natives, continue to favor some migrant groups over others (i.e., Separated Pursuers) and show increasing age‐related sensitivity to who does and who should hold power.

5. General Discussion

Across three studies, we present the first comprehensive examination of children's intuitive, abstract immigration attitudes. Children were presented with a task involving two groups of people: one native to the island and the other migrants to the island, of which the latter also varied on critical dimensions of migrant status and acculturation style. We elicited children's immigration attitudes across a range of social dimensions: children's preferences, resource allocations, and perceptions of solidarity between groups (Experiment 1), children's conferral of voting power (Experiment 2a) and political representation (Experiment 2b), and children's beliefs about political representation when an equal government was not possible (Experiment 3). Overall, children displayed beliefs about immigration, which were present early in development. Moreover, children's attitudes reflected considerations of both migrant status and acculturation style.

First, consistent with past work, we found that children showed a bias in favor of natives. Past theorizing has suggested that children may be using a first‐possession heuristic, believing that native people “own” an island more than a later group of arrivals (see related work by Verkuyten, Sierksma, and Thijs 2015 on children's first arrival = owner bias). Our explanation coding in Experiment 1 corroborates this possibility, with children saying that natives “own” the island more than migrants. Our work also extends this past work by demonstrating that the bias in favor of natives extends to a range of different domains, including children's preferences, conferral of voting power, and political representation. Nevertheless, we also observed boundaries in children's native bias. Although children generally preferred natives, believed natives were better leaders, and readily elected natives into political office, they did not show a native bias when considering how certain resources (e.g., access to schools) should be distributed. Children may be more willing to privilege natives for domains that are not seen as basic needs or rights (see Rizzo et al. 2016 for related findings on children's consideration of “needs”).

Critically, the relative degree of children's native bias varied depending on the type of migrant being evaluated. Children generally favored Pursuers over Fleers and Assimilated migrants over Separated migrants. Children's preference for Pursuers may be explained by a preference for wealthy targets (Shutts et al. 2016). Indeed by nature, concepts of voluntary and involuntary migration are intimately tied to economic status in that involuntary migrants are typically associated with fleeing, refugee status, and/or coming from resource‐poor regions, whereas voluntary migrants are typically associated with economic migrants coming from relatively more resource‐rich regions in pursuit of opportunity (Cortes 2004; De Coninck 2020). Therefore, if we want to understand real‐world attitudes toward these different migrants, it makes sense to start with cases in which these categories track with one another. Still, we note that the resource‐rich migrants in our study did not fit the conventional mold of “wealth”; they were only rich in that they had plenty of access to basic goods, such as food and water. Further, our results suggest that children extend these social preferences to groups even after they had left their well‐resourced homelands, providing new information about how children use past history of wealth in forming their social evaluations. Additionally, children's preference for Assimilated migrants over Separated migrants may be driven by an expectation that migrants adopt the host culture as a sign of respect (Maisonneuve and Testé 2007; Van Oudenhoven, Prins, and Buunk 1998), because migrants “owe” the natives (Ariely 2012; Kunovich 2009), or because children see migrants as lower status than natives, thus expecting the (ostensibly) lower‐status migrants to conform to the (ostensibly) higher status host culture.

Moreover, the intersection of migrant status and acculturation style affected children's evaluations, which is something that cannot be neatly explained by children merely tracking the wealth of the migrants. In some cases, children preferred those migrants who did not assimilate (e.g., Separated Pursuers were more liked and were believed to be better leaders), and in other cases children penalized migrants who did not assimilate (e.g., Separated Fleers were conferred less voting power and political representation, and children believed there would be less intergroup group solidarity between natives and these kinds of migrants). There are a few interpretations for why these migrants are treated so differently. As noted, children may believe that migrants “owe” the natives and this belief could be especially strong for fleers (compared to pursuers) who may be perceived as being more indebted to the natives. Relatedly, fleers may be perceived as lower status than pursuers, and children may expect lower‐status groups to conform to a greater extent than higher‐status groups. The same behavior (e.g., separation) may be interpreted differently based on the migrant's identity: separation may be interpreted positively when enacted by a higher‐status group compared to when it is enacted by a lower‐status group. Future research should aim to further delineate these possibilities and to examine children's intersectional beliefs about different behaviors from different migrant groups.

Overall, these attitudes remained relatively stable across our sample of 4–10‐year‐olds. Children's precocious attention to migrants may be a product of a basic attention to ownership, first‐possession, and ingroup cues that are further shaped into more nuanced attitudes by explicit or passive messaging in children's local environment (media, home, and school environments). Indeed, changing demographics in the United States also mean many young children have more direct exposure to migrant classmates (Suarez‐Orozco, Qin, and Amthor 2008). Despite the relatively stable effects across ages, we did observe some notable age‐related changes. Compared to older children, younger children at times showed a stronger preference for Pursuers and Assimilated migrants. Younger children may be using independent cues of migrant status and assimilation, considerations that with age may become more intersectional, leading to increasingly nuanced and calibrated responses to different kinds of migrants. On the other hand, it is also possible that as with other social attitude domains, older children may tend to prioritize equality, particularly on explicit measures (as seen, though open questions concern whether younger and older children may look similar on implicit measures). Our explanation coding in Experiment 1 offers initial insight into the kinds of considerations children may think through with increasing age, including seeing natives as “saviors” or as being “nicer.” These findings raise exciting future areas of inquiry regarding both the basic processes from which children's migrant attitudes originate, as well as the multiple layers of social and cultural learning involved in their evolving migrant attitudes.

In situating these findings within existing literature, we found that children show surprisingly nuanced attitudes about migrants. Children could have had no systematic intuitions about different kinds of migrants, seeing the four migrant types as undifferentiated from one another, or they might have simply and systematically preferred the natives on all measures. Yet, we demonstrate that children are selective about when they do or do not privilege migrants, both in comparison to natives but also in comparison to other migrant groups. This selectivity is based on dual and intersecting considerations of where migrants come from and whether they assimilate to the natives’ culture. Further, beyond examining children's preferences and trait evaluations, these findings extend to other important domains of life (i.e., political power), thus capturing a broader spectrum of children's immigration cognition.

These findings raise several lines of open enquiry. First, whether children's choices reveal a pro‐native, or anti‐migrant bias (or both) remains unclear. For example, in Experiment 2b, children elected natives into government more often than Separated Fleers, which could reflect a pro‐native bias, anti‐migrant bias, or both. Relatedly, we find initial evidence that children's preferences for Separated Pursuers is in some cases commensurate with, or even trumps, their preferences for natives, leaving open questions concerning the circumstances under which children will or will not favor migrants over natives. Third, though we find evidence that migrant status and acculturation style drive children's attitudes toward migrants, it remains an open question what specifically about these constructs informed children's migrant attitudes. For example, children's sensitivity to migrant status may be a product of their sensitivity to wealth, luck, and even their belief in a just world; children may confer fewer privileges to fleers because they perceive fleers as unlucky due to their more destitute state, or as deserving of their destitution (Furnham 1985; Rubin and Peplau 1975; Shutts et al. 2016; Sigelman 2013). One might explore children's intuitions about different kind of fleers—for example, adults often view economic refugees who flee for better opportunities less favorably than refugees who flee persecution, despite both often coming from lower socioeconomic backgrounds (e.g., Wyszynski, Guerra, and Bierwiaczonek 2020). Relatedly, there may be important distinctions between first‐possessors, prior‐possessors, and current‐possessors, distinctions that are not well clarified in the current and previous literature; particularly given that in the real world, first‐possessors (e.g., indigenous people) do not generally reap the same benefits as current‐possessors. A more intentional examination of what specific factors children attend to will help paint a more comprehensive picture of the role of migrant status and acculturation style on children's immigration attitudes.

Future work might examine more closely the boundary conditions of children's differential evaluations of migrants. For example, asymmetries might rely on the relative ratio of migrants and natives, or the length of time that migrants have lived on the natives’ land. Relatedly, future work might explore a deeper understanding of the nuances within migrant status (e.g., reluctant migration) and acculturation (e.g., integrated acculturation) as well as explore relevant factors beyond migrant status and acculturation. Our analyses highlight potentially relevant factors that additional research might investigate further. First, we find preliminary evidence that demographic factors (e.g., political orientation, parent education, and socioeconomic status) influence children's developing immigration attitudes; children from families with less formal education, less wealth, and whose parents identified as conservative, were more likely to favor natives (see Supporting Materials S1). Second, an examination of children's explanations revealed factors (e.g., perceptions of a native savior complex, or native ownership over the land) that may be relevant in forming children's construal of migrants see Supporting Materials S2). Additional research may also explore immigration attitudes in children across different cultural contexts beyond a US sample, including countries in which the level of migration as well as political rhetoric surrounding immigration is different from the U.S. Such extensions involving a more diverse participant pool could provide insight into how the conceptual building blocks of immigration attitudes, even at an abstract level, may be informed by local cultural contexts.

Not all migrants are perceived as equal in children's eyes. Children confer more privileges upon some migrants over others. We find that children engage in dual considerations of both where a migrant comes from, and whether migrants assimilate. Indeed, these patterns emerge both in children's general attitudes, as well as in the specific, highly consequential domain of politics. Together, these findings offer novel insights into children's immigration attitudes and into the role of migrant status and acculturation on children's developing immigration cognition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Disclosure

These findings have been presented at the Society of Personality and Social Psychology (SPSP) conference and Cognitive Development Society (CDS) conference. Experiments were not pre‐registered.

Supporting information

Supporting‐Information

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Science Foundation grant 1941648, awarded to K.D.K. We thank Sahil Suresh (Cornell University) for assisting with the stimuli creation. We thank Molly Gibian for her testing support and the Development of Social Cognition lab for their thoughtful feedback on the project. Finally, we thank the families who participated in this study.

Funding: This research was supported by an NSF grant 1941648, awarded to K.D.K.

Endnotes

We use the superordinate category “migrant” (of which “immigrant” is a subordinate category) to capture a more inclusive spectrum of people, including (but not limited to) refugees.

Data Availability Statement

The data and code that support the findings of this study are available on OSF: https://osf.io/xzgcw.

References

- Abdelaaty, L. , and Steele L. G.. 2022. “Explaining Attitudes Toward Refugees and Immigrants in Europe.” Political Studies 70, no. 1: 110–130. 10.1177/0032321720950217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, D. , Van de Vyver J., Pelletier J., and Cameron L.. 2015. “Children's Prosocial Behavioural Intentions Towards Outgroup Members.” British Journal of Developmental Psychology 33, no. 3: 277–294. 10.1111/bjdp.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariely, G. 2012. “Do Those Who Identify With Their Nation Always Dislike Immigrants?: An Examination of Citizenship Policy Effects.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 18, no. 2: 242–261. 10.1080/13537113.2012.680862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J. W. 1980. “Acculturation as Varieties of Adaptation.” Acculturation: Theory, Models and Some New Findings 9: 25. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J. W. , Poortinga Y. H., Pandey J., Segall M. H., and Kâğıtçıbaşı Ç.. 1997. Handbook of Cross‐Cultural Psychology: Social Behavior and Applications. John Berry. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, P. R. , McAuliffe K., Corbit J., et al. 2015. “The Ontogeny of Fairness in Seven Societies.” Nature 528, no. 7581: Article 7581. 10.1038/nature15703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. S. 2011. “American Elementary School Children's Attitudes About Immigrants, Immigration, and Being an American.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 32, no. 3: 109–117. 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, C. R. , and Tsai Y.. 2001. “Social Factors Influencing Immigration Attitudes: An Analysis of Data From the General Social Survey.” Social Science Journal 38, no. 2: 177–188. 10.1016/S0362-3319(01)00106-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohrs, J. C. , and Stelzl M.. 2010. “How Ideological Attitudes Predict Host Society Members' Attitudes Toward Immigrants: Exploring Cross‐National Differences.” Journal of Social Issues 66, no. 4: 673–694. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01670.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, K. E. 2004. “Are Refugees Different from Economic Immigrants? Some Empirical Evidence on the Heterogeneity of Immigrant Groups in the United States.” Review of Economics and Statistics 86, no. 2: 465–480. [Google Scholar]

- De Coninck, D. 2020. “Migrant Categorizations and European Public Opinion: Diverging Attitudes Towards Immigrants and Refugees.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46, no. 9: 1667–1686. 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1694406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinas, E. , and van Spanje J.. 2011. “Crime Story: The Role of Crime and Immigration in the Anti‐Immigration Vote.” Electoral Studies 30, no. 4: 658–671. 10.1016/j.electstud.2011.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl, J.‐M. , Meltzer C. E., Heidenreich T., et al. 2018. “The European Media Discourse on Immigration and Its Effects: A Literature Review.” Annals of the International Communication Association 42, no. 3: 207–223. 10.1080/23808985.2018.1497452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann, J. M. , and Tomasello M.. 2019. “Children's Sense of Fairness as Equal Respect.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 23, no. 6: 454–463. 10.1016/j.tics.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espenshade, T. J. , and Hempstead K.. 1996. “Contemporary American Attitudes Toward U.S. Immigration.” International Migration Review 30: 535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essa, F. , Weinsdörfer A., Shilo R., Diesendruck G., and Rakoczy H.. 2021. “Children Explain In‐and Out‐Group Behavior Differently.” Social Development 30, no. 3: 684–696. [Google Scholar]

- Farris, E. M. , and Silber Mohamed H.. 2018. “Picturing Immigration: How the Media Criminalizes Immigrants.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 6, no. 4: 814–824. 10.1080/21565503.2018.1484375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, O. , and Neary K. R.. 2008. “Determining Who Owns What: Do Children Infer Ownership From First Possession?” Cognition 107, no. 3: 829–849. 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, O. , Van de Vondervoort J. W., Defeyter M. A., and Neary K. R.. 2013. “First Possession, History, and Young Children's Ownership Judgments.” Child Development 84, no. 5: 1519–1525. 10.1111/cdev.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryberg, S. A. , Stephens N. M., Covarrubias R., et al. 2012. “How the Media Frames the Immigration Debate: The Critical Role of Location and Politics.” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 12, no. 1: 96–112. 10.1111/j.1530-2415.2011.01259.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furby, L. 1978. “Possession in Humans: An Exploratory Study of Its Meaning and Motivation.” Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 6, no. 1: 49–65. 10.2224/sbp.1978.6.1.49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, A. 1985. “Just World Beliefs in an Unjust Society: A Cross Cultural Comparison.” European Journal of Social Psychology 15, no. 3: 363–366. 10.1002/ejsp.2420150310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup . 2020. World Grows Less Accepting of Migrants . Gallup.Com. https://news.gallup.com/poll/320678/world‐grows‐less‐accepting‐migrants.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Garand, J. C. , Xu P., and Davis B. C.. 2017. “Immigration Attitudes and Support for the Welfare State in the American Mass Public.” American Journal of Political Science 61, no. 1: 146–162. 10.1111/ajps.12233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gieling, M. , Thijs J., and Verkuyten M.. 2011. “Voluntary and Involuntary Immigrants and Adolescents' Endorsement of Multiculturalism.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 35, no. 2: 259–267. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, B. W. , and Friedman O.. 2018. “The Development of Territory‐Based Inferences of Ownership.” Cognition 177: 142–149. 10.1016/j.cognition.2018.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainmueller, J. , and Hopkins D. J.. 2014. “Public Attitudes Toward Immigration.” Annual Review of Political Science 17, no. 1: 225–249. 10.1146/annurev-polisci-102512-194818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heck, I. A. , Santhanagopalan R., Cimpian A., and Kinzler K. D.. 2021. “Understanding the Developmental Roots of Gender Gaps in Politics.” Psychological Inquiry 32, no. 2: 53–71. 10.1080/1047840X.2021.1930741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heck, I. A. , Shutts K., and Kinzler K. D.. 2022. “Children's Thinking About Group‐Based Social Hierarchies.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 26, no. 7: 593–606. 10.1016/j.tics.2022.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalish, C. W. 2012. “Generalizing Norms and Preferences Within Social Categories and Individuals.” Developmental Psychology 48, no. 4: 1133–1143. 10.1037/a0026344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler, K. D. , and Dautel J. B.. 2012. “Children's Essentialist Reasoning About Language and Race.” Developmental Science 15, no. 1: 131–138. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunovich, R. M. 2009. “The Sources and Consequences of National Identification.” American Sociological Review 74, no. 4: 573–593. 10.1177/000312240907400404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman, Z. , Woodward A. L., and Kinzler K. D.. 2017. “The Origins of Social Categorization.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21, no. 7: 556–568. 10.1016/j.tics.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve, C. , and Testé B.. 2007. “Acculturation Preferences of a Host Community: The Effects of Immigrant Acculturation Strategies on Evaluations and Impression Formation.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 31, no. 6: 669–688. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markaki, Y. , and Longhi S.. 2013. “What Determines Attitudes to Immigration in European Countries? An Analysis at the Regional Level.” Migration Studies 1, no. 3: 311–337. 10.1093/migration/mnt015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matera, C. , Stefanile C., and Brown R.. 2011. “The Role of Immigrant Acculturation Preferences and Generational Status in Determining Majority Intergroup Attitudes.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47, no. 4: 776–785. 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe, K. , Blake P. R., Steinbeis N., and Warneken F.. 2017. “The Developmental Foundations of Human Fairness.” Nature Human Behaviour 1, no. 2: 0042. 10.1038/s41562-016-0042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafaj, M. , Madrigal G., Roden J., and Ploger G. W.. 2022. “Physiological Threat Sensitivity Predicts Anti‐Immigrant Attitudes.” Politics and the Life Sciences 41, no. 1: 15–27. 10.1017/pls.2021.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasie, M. , and Diesendruck G.. 2020. “What Children Want to Know About In‐ and Out‐Groups, and How Knowledge Affects Their Intergroup Attitudes.” Social Development 29, no. 2: 443–460. 10.1111/sode.12408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes, A. , and Dunham Y.. 2017. “Mutual Intentions as a Causal Framework for Social Groups.” Cognition 162: 133–142. 10.1016/j.cognition.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, M. M. , Bigler R. S., Pahlke E., et al. 2019. “Toward a Developmental Science of Politics.” Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 84, no. 3: 7–185. 10.1111/mono.12410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razpurker‐Apfeld, I. , Shamoa‐Nir L., Taylor L. K., and Dautel J. B.. 2024. “Children's Bias Beyond Group Boundaries: Perceived Differences, Outgroup Attitudes and Prosocial Behaviour.” European Journal of Social Psychology 54, no. 4: 1002–1014. 10.1002/ejsp.3065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, M. T. , Elenbaas L., Cooley S., and Killen M.. 2016. “Children's Recognition of Fairness and Others' Welfare in a Resource Allocation Task: Age Related Changes.” Developmental Psychology 52, no. 8: 1307–1317. 10.1037/dev0000134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, S. 2019. “Status‐Making: Rethinking Migrant Categorization.” Journal of Sociology 55, no. 2: 219–233. 10.1177/1440783318791761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, Z. , and Peplau L. A.. 1975. “Who Believes in a Just World?” Journal of Social Issues 31, no. 3: 65–89. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1975.tb00997.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, M. , Cueva Chacón M., L., and García‐Perdomo V.. 2018. “When Gaps Become Huuuuge: Donald Trump and Beliefs About Immigration.” Mass Communication and Society 21, no. 6: 785–813. 10.1080/15205436.2018.1504304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santhanagopalan, R. , DeJesus J. M., Moorthy R. S., and Kinzler K. D.. 2021. “Nationality Cognition in India: Social Category Information Impacts Children's Judgments of People and Their National Identity.” Cognitive Development 57: 100990. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2020.100990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, A. , and Olson K.. 2014. “Fairness as Partiality Aversion: The Development of Procedural Justice.” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 119: 40–53. 10.1016/j.jecp.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutts, K. , Brey E. L., Dornbusch L. A., Slywotzky N., and Olson K. R.. 2016. “Children Use Wealth Cues to Evaluate Others.” PLoS ONE 11, no. 3: e0149360. 10.1371/journal.pone.0149360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman, C. K. 2013. “Age Differences in Perceptions of Rich and Poor People: Is It Skill or Luck?” Social Development 22, no. 1: 1–18. 10.1111/sode.12000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez‐Orozco, C. , Qin D. B., and Amthor R. F.. 2008. “Adolescents From Immigrant Families: Relationships and Adaptation in school.” In Adolescents at School: Perspectives on Youth, Identity, and Education, edited by Sadowski M., 2nd ed., 51–69. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations International Organization for Migration . 2020. “World Migration Report 2020.” International Organization for Migration (IOM). https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf.

- Van Oudenhoven, J. P. , Prins K. S., and Buunk B. P.. 1998. “Attitudes of Minority and Majority Members Towards Adaptation of Immigrants.” European Journal of Social Psychology 28, no. 6: 995–1013. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten, M. 2005. “Ethnic Group Identification and Group Evaluation among Minority and Majority Groups: Testing the Multiculturalism Hypothesis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88, no. 1: 121–138. 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten, M. , Mepham K., and Kros M.. 2018. “Public Attitudes Towards Support for Migrants: The Importance of Perceived Voluntary and Involuntary Migration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41, no. 5: 901–918. 10.1080/01419870.2017.1367021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten, M. , Sierksma J., and Thijs J.. 2015. “First Arrival and Owning the Land: How Children Reason About Ownership of Territory.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 41: 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten, M. , Thijs J., and Sierksma J.. 2014. “Majority Children's Evaluation of Acculturation Preferences of Immigrant and Emigrant Peers.” Child Development 85, no. 1: 176–191. 10.1111/cdev.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyszynski, M. C. , Guerra R., and Bierwiaczonek K.. 2020. “Good Refugees, Bad Migrants? Intergroup Helping Orientations Toward Refugees, Migrants, and Economic Migrants in Germany.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 50, no. 10: 607–618. 10.1111/jasp.12699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting‐Information

Data Availability Statement

The data and code that support the findings of this study are available on OSF: https://osf.io/xzgcw.