Abstract

Objectives:

In the United States, firearm injuries disproportionately occur in low-income communities and among racial and ethnic minority populations. Recognizing these patterns across social conditions is vital for effective public health interventions. Using timely and localized data, we examined the association between social vulnerability and firearm injuries in King County, Washington.

Methods:

For this ecological, cross-sectional study, we used health reporting areas (HRAs) (n = 61), a subcounty geography of King County. We obtained HRA-level counts of firearm injuries by using responses from King County emergency medical services (EMS) from 2019 through 2023. We measured HRA-level social vulnerability by using the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, categorized into tertiles (low, moderate, and high SVI). We used bivariate choropleth mapping to illustrate spatial associations between SVI and rates of firearm injuries per 10 000 residents. We used Bayesian spatial negative binomial regression to quantify the strength of these associations.

Results:

Bivariate choropleth mapping showed a correlation between SVI and rates of firearm injuries. In spatial models, HRAs categorized as high SVI had a 3 times higher rate of firearm injuries than HRAs categorized as low SVI (incidence rate ratio = 3.01; 95% credible interval, 2.02-4.47). Rates of firearm injuries were also higher in HRAs categorized as moderate versus low SVI (incidence rate ratio = 1.72; 95% credible interval, 1.23-2.40).

Conclusion:

In King County, areas with high social vulnerability had high rates of EMS responses to firearm injuries. SVI can help identify geographic areas for intervention and provide a framework for identifying upstream factors that might contribute to spatial disparities in firearm injuries.

Keywords: firearms, neighborhoods, health disparities, social determinants of health, injury, violence

Nationally, rates of fatal and nonfatal firearm injuries increased from 2019 through 2022, highlighting the continued magnitude of firearm injuries as a public health problem.1-3 Disparities in rates of fatal firearm injury by race and ethnicity are also evident. Among racial and ethnic groups, non-Hispanic Black people have the highest rates of firearm homicide. 2 The largest increase in firearm suicide rates from 2019 through 2022 was among American Indian or Alaska Native people, followed by non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic or Latino people. 3 Disparities are also present in King County, Washington, where deaths from firearm injury of all intents (ie, homicide, suicide, and unintentional) disproportionately affect non-Hispanic Black residents. From 2019 through 2021, the combined rate of firearm injury deaths per 100 000 population was 23.3 among non-Hispanic Black residents and 7.6 among non-Hispanic White residents. 4

Firearm injuries, both fatal and nonfatal, also cluster in urban areas.5-10 Such patterns might suggest that neighborhood-level factors, influenced by systemic inequities such as structural racism, contribute to both the prevalence of and disparities in firearm injuries. 11 Ecological studies have shown associations between firearm injuries and neighborhood-level characteristics, including poverty, neighborhood disadvantage, racial and ethnic composition, and social vulnerability.7,8,10,12 In understanding the impact of neighborhood characteristics on firearm injuries, these studies highlight the relevance of social disorganization theory. Social disorganization theory posits that neighborhoods with high social vulnerability—characterized by social conditions, including poverty and racial and ethnic segregation—experience structural disadvantages that prevent residents from establishing social cohesion and informal social control, leading to increased crime, violence, and firearm injuries.6,13 Incorporating area-based measures, such as social vulnerability indexes, into public health surveillance can enhance the monitoring of disparities and inform efforts to mitigate them. 14

We sought to examine the association between social vulnerability across areas in King County with firearm injuries treated by emergency medical services (EMS) providers. EMS data are timely and contain details on geographic location of the incident that caused the injury. In contrast, mortality data for firearm injury surveillance are not timely and lack details on injury location, and hospital data are often missing information on injury location.8,15,16 Guided by social disorganization theory, we hypothesized that areas with high social vulnerability would exhibit elevated rates of firearm injuries, reflecting the compounding effects of structural inequities. Our objectives were to explore the spatial distribution and strength of the association between social vulnerability and rates of firearm injuries.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

In this ecological study in King County, we used health reporting areas (HRAs) as the unit of analysis (n = 61). Public Health–Seattle and King County created HRAs, which are based on aggregations of blocks defined by the US Census Bureau for the 2020 US Census. 17 Where possible, HRAs correspond to neighborhoods in larger cities (eg, Seattle), smaller cities, or unincorporated areas of King County. We chose HRAs rather than other geographies (eg, census tracts, block groups) because HRAs better align with local administrative boundaries, making them more practical for King County policy makers and for communicating findings to the public.

Firearm Injuries

We used HRA-level counts of firearm injuries in King County treated by EMS providers (referred to hereinafter as firearm injuries) from January 1, 2019, through December 31, 2023, as the outcome for our analysis. We included and combined both fatal injuries and nonfatal injuries of all intents. We identified firearm injuries in patients from electronic care reports by querying across 5 data entry fields: chief concern, EMS provider narrative, primary injury, injury details, and assessment of gunshot wound (details on firearm injury case definition are available in eSupplemental Methods).

Social Vulnerability Index

We used the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (CDC/ATSDR), a summary measure of social conditions, to measure HRA-level social vulnerability. 18 SVI is a composite, percentile rank–based index that quantifies the relative social vulnerability of geographic areas. SVI ranks geographic areas by using 16 sociodemographic variables derived from the 2016-2020 American Community Survey. 19 SVI is composed of 4 themes, which collectively form an overall social vulnerability score. These 4 themes are: (1) socioeconomic status, (2) household characteristics, (3) racial and ethnic minority status, and (4) housing type and transportation. SVI values represent percentile ranks on a scale from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate greater social vulnerability. CDC provided readily available county-level and census tract–level SVI scores. However, for this analysis, we calculated and ranked SVI values at the HRA level for King County, both overall and by theme (details are available in eSupplemental Methods). We used data from the 2016-2020 American Community Survey in accordance with the most recent CDC/ATSDR SVI. 18

Data Analysis

We categorized SVI values into tertiles (ie, equal thirds) for the overall measure and the 4 theme-specific domains. We conducted the main analysis in 3 steps. First, we calculated the mean rate per 10 000 residents of firearm injuries across SVI tertiles for each SVI measure. Second, we generated bivariate choropleth maps by using a tertile classification scheme to visualize the simultaneous spatial distribution of SVI and firearm injury rate. Third, we developed 5 models for each SVI measure to estimate the strength of the association between SVI and firearm injury. Because of the presence of overdispersion, we selected negative binomial models versus Poisson models. Spatial autocorrelation (ie, tendency of neighboring areas to exhibit similar characteristics) can bias results and lead to inaccurate inferences. We assessed spatial autocorrelation by calculating the global Moran’s I value across Pearson residuals for a negative binomial model. Given evidence of spatial autocorrelation, we used the approach from Bilal et al 20 by fitting Besag-York-Mollié (BYM) conditional autoregressive models for negative binomial outcomes from integrated nested Laplace approximations (INLA), a method designed to perform approximate Bayesian inference. 20 Spatial models such as BYM conditional autoregressive models can help mitigate bias from spatial autocorrelation, enhancing the robustness and accuracy of findings. For these spatial models, we included structured and unstructured HRA random effects, which account for neighboring HRAs being more similar than HRAs that are farther apart. We defined neighboring HRAs as those sharing contiguous boundaries (ie, queen contiguity). We excluded 1 HRA because it comprised an island and, thus, had no spatial neighbors. We present main results from spatial BYM models as incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% credible intervals (95% CrIs) across SVI tertiles (details on the BYM model are available in eSupplemental Methods).

We conducted 3 sets of supplemental analyses. First, to examine the robustness of our findings to variations in the spatial unit of analysis, we replicated BYM models using census tracts as an alternative unit. Second, to investigate potential variations in the association between overall SVI and firearm injuries across various factors, we replicated BYM models after stratifying the data by gender (female or male), age group (0-17, 18-24, 25-44, 45-64, ≥65 y), and transportation type to a medical facility as a proxy for injury severity (none or refused transport [low], basic life support [moderate], advanced life support [severe], died before EMS arrival [fatal]). Third, to examine which SVI components were most strongly associated with the study outcome, we calculated Spearman correlation coefficients between each of the 16 census variables used to calculate the SVI percentile ranks, treating them as continuous variables, and the rate of firearm injuries, with each at the HRA level. We used R version 4.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) for all analyses. We conducted bivariate choropleth mapping with the biscale package (version 1.0.0) and spatial analyses with the spdep (version 1.3.1) and INLA (version 24.1.14) packages (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

CDC determined the study was not human subjects research and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy (45 CFR part 46; 21 CFR part 56; 42 USC §241(d); 5 USC §552a; 44 USC §3501 et seq). Consequently, CDC determined that institutional review board approval was not required.

Results

From 2019 through 2023, 3467 firearm injuries (15.3 per 10 000 residents) were treated by King County EMS providers across 61 HRAs. Among the HRAs, the number of injuries ranged from 5-177, with an overall mean of 56.8 injuries during the 5-year study period. Half of these incidents (49.9%) occurred in 13 of 61 HRAs (21.3%). We also present the characteristics of the 61 HRAs according to the 16 sociodemographic variables grouped by the 4 themes (eTable 1).

HRAs with higher overall SVI values had a higher frequency of firearm injuries than HRAs with lower overall SVI values (Table 1). The mean rate of firearm injuries per 10 000 residents was 28.5 in HRAs characterized by high SVI, followed by 12.5 in HRAs characterized by moderate SVI, and 6.4 in HRAs characterized by low SVI. We also observed a pattern of increasing firearm injury rates as SVI increased for each of the 4 SVI themes. Although the rate of firearm injuries per 10 000 residents increased from 2.2 in 2019 (n = 503) to 3.8 in 2023 (n = 865), the association between SVI and firearm injuries remained consistent over time.

Table 1.

Distribution of responses by emergency medical services for firearm injuries, by 2020 Social Vulnerability Index themes across health reporting areas (n = 61), King County, Washington, 2019-2023 a

| Level of Social Vulnerability Index, overall and by theme | Total injuries, no. (%) (n = 3467) | Rate per 10 000 residents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (range) | ||

| Overall vulnerability | |||

| Low | 496 (14.3) | 6.4 (3.3) | 4.6 (2.4-12.7) |

| Moderate | 1000 (28.9) | 12.5 (9.5) | 10.3 (4.0-43.9) |

| High | 1971 (56.9) | 28.5 (12.7) | 27.4 (5.9-62.2) |

| Theme 1: socioeconomic status | |||

| Low | 491 (14.2) | 6.0 (2.9) | 4.6 (2.4-12.0) |

| Moderate | 898 (25.9) | 11.3 (6.0) | 10.5 (4.1-24.7) |

| High | 2078 (59.9) | 30.2 (12.3) | 29.2 (11.4-62.2) |

| Theme 2: household characteristics | |||

| Low | 709 (20.4) | 8.6 (8.9) | 5.6 (2.4-43.9) |

| Moderate | 896 (25.8) | 13.2 (13.6) | 8.6 (3.3-62.2) |

| High | 1862 (53.7) | 25.5 (10.6) | 24.9 (7.8-46.1) |

| Theme 3: racial and ethnic minority status | |||

| Low | 589 (17.0) | 7.6 (3.9) | 6.1 (2.4-16.2) |

| Moderate | 955 (27.5) | 12.2 (10.3) | 8.5 (2.7-43.9) |

| High | 1923 (55.5) | 27.5 (13.8) | 27.4 (4.5-62.2) |

| Theme 4: housing type and transportation | |||

| Low | 547 (15.8) | 7.3 (3.8) | 6.1 (2.4-14.7) |

| Moderate | 1168 (33.7) | 14.9 (11.5) | 11.0 (3.1-46.1) |

| High | 1752 (50.5) | 25.1 (15.0) | 24.1 (4.7-62.2) |

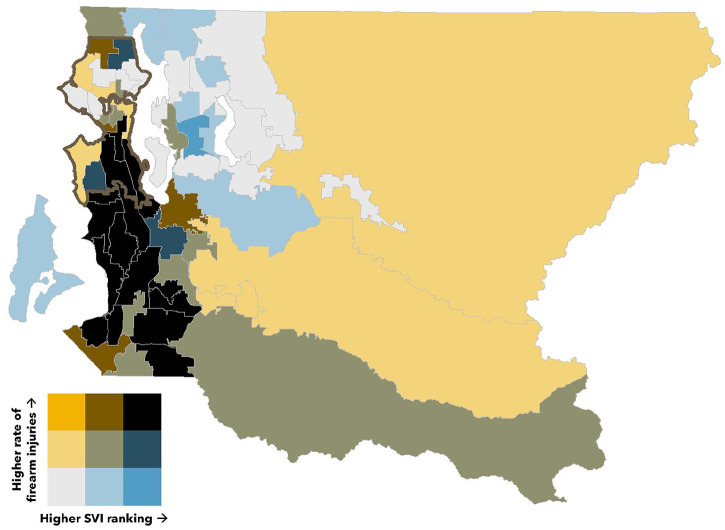

When we examined the correlation between overall SVI measure and firearm injury in HRAs, 16 of 61 HRAs (26.2%) were characterized by both high SVI and high firearm injury rates, which appeared to cluster in the southern part of Seattle and neighboring areas to the south (Figure). Conversely, 13 of 61 HRAs (21.3%) were characterized by both low SVI and low firearm injury rates, which appeared to cluster in the northern part of Seattle and neighboring areas to the east. In addition, 9 of 61 HRAs (14.8%) were characterized by both moderate SVI and moderate firearm injury rates. One HRA was characterized by both high SVI and low firearm injury rates, and no HRAs were characterized by both low SVI and high firearm injury rates. Patterns were similar across each SVI theme (eFigure in the Supplement).

Figure.

Bivariate spatial distribution of responses by emergency medical services (EMS) for firearm injuries and the overall 2020 Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) across health reporting areas (n = 61) in King County, Washington, 2019-2023. Firearm injuries are based on EMS responses per 10 000 residents. The outlined region represents the city of Seattle.

In spatial BYM models, the overall SVI measure was associated with a higher incidence of firearm injury. The strength of this association was most pronounced in HRAs characterized as having high SVI versus low SVI (Table 2). Compared with HRAs characterized as low SVI, HRAs characterized as high SVI had an incidence rate that was 3 times higher (IRR = 3.01; 95% CrI, 2.02-4.47). HRAs with moderate SVI had a 72% increased incidence rate of firearm injuries (IRR = 1.72; 95% CrI, 1.23-2.40). Across SVI themes, socioeconomic status had the strongest association between SVI and firearm injuries, which was particularly evident when comparing high versus low SVI (IRR = 3.48; 95% CrI, 2.38-5.07). We also observed positive associations across the remaining SVI themes, including household characteristics, racial and ethnic minority status, and housing type and transportation. Results were consistent when census tracts were used as the unit of analysis (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Table 2.

Incidence rate ratios of responses by emergency medical services for firearm injuries, by 2020 Social Vulnerability Index across health reporting areas, King County, Washington, 2019-2023 a

| Level of Social Vulnerability Index, overall and by theme | Incidence rate ratio b (95% CrI) |

|---|---|

| Overall vulnerability | |

| Low | 1 [Reference] |

| Moderate | 1.72 (1.23-2.40) |

| High | 3.01 (2.02-4.47) |

| Theme 1: socioeconomic status | |

| Low | 1 [Reference] |

| Moderate | 1.60 (1.14-2.25) |

| High | 3.48 (2.38-5.07) |

| Theme 2: household characteristics | |

| Low | 1 [Reference] |

| Moderate | 1.35 (0.90-2.02) |

| High | 2.08 (1.22-3.51) |

| Theme 3: racial and ethnic minority status | |

| Low | 1 [Reference] |

| Moderate | 1.55 (1.10-2.20) |

| High | 2.49 (1.64-3.76) |

| Theme 4: housing type and transportation | |

| Low | 1 [Reference] |

| Moderate | 1.49 (1.04-2.14) |

| High | 2.32 (1.59-3.37) |

Abbreviation: CrI, credible interval.

Sixteen sociodemographic variables derived from the 2016-2020 American Community Survey 19 were grouped into 4 themes, which collectively formed the overall Social Vulnerability Index 18 score.

Incidence rate ratios were derived from spatial Besag-York-Mollié conditional autoregressive negative binomial models. One health reporting area was excluded from spatial analyses because of the absence of neighboring observations, which precluded application of spatial dependence measures.

When data were stratified by sex, age categories, and injury severity, positive associations between the overall SVI measure and firearm injury rates across HRAs persisted in spatial models (eTable 3 in the Supplement). However, the magnitude of associations varied by groups. Specifically, associations were stronger among male patients (vs female patients) treated, people who were aged <45 (vs ≥45) years, and people who had nonfatal severe (vs nonfatal low, nonfatal moderate, or fatal) injuries.

In our analysis of Spearman correlations between rates of firearm injuries and the 16 census variables used to generate SVI, variables that had the strongest associations with rates of firearm injuries were in the socioeconomic status theme (eTable 4 in the Supplement). The variables included no health insurance (ρ = 0.81), no high school diploma (ρ = 0.81), housing cost burden (ρ = 0.80), and below poverty level (ρ = 0.76). Variables with the weakest associations with rates of firearm injuries were in the housing type and transportation theme, which included multiunit housing (ρ = 0.26) and group quarters (ρ = 0.18). Among variables in the household characteristics theme, we found weak associations for age composition, including ≥65 years (ρ = 0.00) and ≤17 years (ρ = –0.04).

Discussion

In this ecological study, we observed spatial disparities in firearm injury rates across HRAs in King County. Specifically, we found an association between high SVI level and elevated rates of firearm injuries. These associations persisted even after accounting for spatial autocorrelation in regression models.

In King County, the use of HRAs as the level of analysis is practical for policy-making and tailored interventions. In addition, HRAs facilitate effective communication with residents, because these geographic units often represent cohesive communities with shared characteristics and concerns. However, acknowledgment of the modifiable areal unit problem is important, as different results might arise based on the scale of geographic units used. 21 Nevertheless, our supplemental analyses using census tracts were consistent with HRA-level findings, validating the use of HRAs.

Our findings align with previous research highlighting the influence of socioeconomic factors on community-level rates of firearm injuries,7,8,12 including studies on the association between SVI and firearm injury rates.10,22 Notable geographic variations exist in how individual SVI components are associated with firearm injuries. In one study, for example, authors merged census tract–level data from Baltimore, Maryland; Chicago, Illinois; Los Angeles, California; New York, New York; and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to estimate the association between SVI and pediatric firearm injuries. They found that “no vehicle” was among the factors most strongly associated with shooting incidents. 10 However, in King County, associations were markedly stronger among variables in the socioeconomic status theme of SVI, with “no vehicle” (in the housing type and transportation theme) playing a less prominent role. In summary, firearm injury risks vary nationwide, indicating limitations in the generalizability of community-level risk data. Consequently, the use of SVI in localized geographic areas might provide more meaningful insights than aggregating data across multiple cities or at the national level. Such localized analyses can better capture diverse contextual influences that shape the association between SVI and firearm injuries, guiding more effective and tailored interventions in specific regions.

Although this cross-sectional study cannot draw causal conclusions, our findings suggest that investigations of structural factors associated with the area-level socioeconomic composition might aid firearm injury prevention efforts in King County. For example, historic redlining, a racially discriminatory mortgage lending practice, is a manifestation of structural racism. Theoretical frameworks suggest that historic redlining has led to present-day racial residential segregation and neighborhood disinvestment and has facilitated income inequality by creating unequal opportunities for homeownership and wealth accumulation, all of which have disproportionately affected non-Hispanic Black residents and other racial and ethnic minority populations.23-25 These factors have been linked to racial and ethnic health disparities, including disparities in firearm injuries.23-25 In a Boston-based study, poverty, poor educational attainment, and the need for public services were shown to be important mediators in the causal pathway between historic redlining and firearm injuries at the census-tract level. 26 The recognition of socioeconomic factors as modifiable highlights their importance as areas for strategic intervention.

Neighborhood disinvestment is another modifiable socioeconomic factor, affecting communities on a broad scale. For example, remediation of abandoned and vacant properties has shown efficacy in reducing firearm violence and injury outcomes.27-29 Such place-based interventions are considered low cost and scalable, making them suitable for widespread implementation and adaptability across various contexts.

Despite being relatively underused for public health surveillance, EMS data provide a timely depiction of the geographic distribution of firearm injuries. By using incident location rather than patient residence or treatment location, we can provide a more accurate basis for tailored place-based interventions to reduce firearm injuries. In addition, information from 9-1-1 responses in King County is typically received within 2 hours of the finalized patient care records from EMS providers, and aggregated data are publicly available monthly. This timeliness facilitated our ability to include data up to 2023. Furthermore, EMS data can identify a broad spectrum of patients with firearm injuries, including those who called 9-1-1 but did not seek hospital treatment. Relying solely on hospital-based data might overlook these cases.

Limitations

Several limitations are worth noting. First, SVI documents contemporary social and economic conditions in communities and might not directly address or capture root causes of disparities compared with specific policies or interventions. Second, SVI assigns equal weight to variables, yet we found evidence that certain variables appeared more relevant in the context of firearm injuries than others, such as those in the socioeconomic status theme. SVI also assumes homogeneity in racial and ethnic minority communities through a single “racial and ethnic minority” variable. In King County, 47.9% of the population identifies as belonging to a racial or ethnic minority group, with the largest share identifying as non-Hispanic Asian (21.0%), followed by Hispanic or Latino (11.2%) and non-Hispanic Black (6.8%). 30 Combining the composition of people who identify outside of non-Hispanic White masks variations in firearm injury rates across these communities and implicitly assumes uniformity across community-level risk factors, including structural factors. Future analyses should consider disaggregating data by specific racial and ethnic categories to capture data on patterns of firearm injury and differentiate risk factors more fully.

Third, our study was not designed to disaggregate firearm injuries by intent, preventing us from distinguishing among fatal and nonfatal assault, suicide, and unintentional injuries. Therefore, we could not determine whether differences existed in SVI based on injury intent. Understanding these differences could provide insights into how structural factors might influence types of firearm injuries. Fourth, this investigation captured firearm injuries only when EMS was involved, thus potentially excluding scenarios in which it was immediately apparent that a person died from a firearm injury, cases in which patients were directly transported to an emergency department or other health care facility without EMS involvement, and incidents with low-severity injuries managed through self-treatment. Therefore, our findings might not fully represent the entire spectrum of firearm injuries. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of firearm injuries, future research can combine EMS data with other sources such as emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and death records. Such linkages can provide a more nuanced understanding of the broader landscape of firearm injuries. Fifth, the temporal misalignment between SVI (derived from the 2016-2020 American Community Survey 19 ) and our firearm injury data (2019-2023) limited our ability to capture data on recent changes in social vulnerability. Although the SVI aggregates data during a 5-year period, demographic shifts during the COVID-19 pandemic could have influenced the analysis. However, the rank-based nature of the SVI helps mitigate the effect of these shifts by focusing on relative vulnerability.

Conclusions

Our findings support community-level strategies that address upstream determinants of social vulnerability, especially those influencing socioeconomic factors. In addition, our analysis provides a framework for other local public health jurisdictions to replicate and tailor interventions to their specific contexts.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-phr-10.1177_00333549241301714 for Spatial Analysis of Social Vulnerability and Firearm Injury EMS Encounters in King County, Washington, 2019-2023 by Precious Esie, Jennifer Liu, Karyn Brownson, Amy J. Poel, Myduc Ta and Aley Joseph Pallickaparambil in Public Health Reports®

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Daniel Casey, MPH, Public Health–Seattle and King County, who provided technical support on the Social Vulnerability Index calculation across King County health reporting areas.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusion in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ORCID iDs: Precious Esie, PhD, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8583-2513

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8583-2513

Jennifer Liu, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7177-9758

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7177-9758

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online. The authors have provided these supplemental materials to give readers additional information about their work. These materials have not been edited or formatted by Public Health Reports’s scientific editors and, thus, may not conform to the guidelines of the AMA Manual of Style, 11th Edition.

References

- 1. Zwald ML, Van Dyke ME, Chen MS, et al. Emergency department visits for firearm injuries before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January–December 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(13):333-337. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7213a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kegler SR, Simon TR, Sumner SA. Notes from the field: firearm homicide rates, by race and ethnicity—United States, 2019-2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(42):1149-1150. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7242a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaczkowski W, Kegler SR, Chen MS, Zwald ML, Stone DM, Sumner SA. Notes from the field: firearm suicide rates, by race and ethnicity—United States, 2019-2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(48):1307-1308. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7248a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Public Health–Seattle & King County. Firearms-related deaths, King County. 2023. Accessed December 1, 2023. https://kingcounty.gov/en/legacy/depts/health/data/community-health-indicators/washington-state-vital-statistics-death.aspx?shortname=Firearms-related%20deaths

- 5. Braga AA, Papachristos AV, Hureau DM. The concentration and stability of gun violence at micro places in Boston, 1980-2008. J Quant Criminol. 2010;26(1):33-53. doi: 10.1007/s10940-009-9082-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Magee LA. Community-level social processes and firearm shooting events: a multilevel analysis. J Urban Health. 2020;97(2):296-305. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00424-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zebib L, Stoler J, Zakrison TL. Geo-demographics of gunshot wound injuries in Miami-Dade County, 2002-2012. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):174. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4086-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dalve K, Gause E, Mills B, Floyd AS, Rivara FP, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Neighborhood disadvantage and firearm injury: does shooting location matter? Inj Epidemiol. 2021;8(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s40621-021-00304-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beard JH, Morrison CN, Jacoby SF, et al. Quantifying disparities in urban firearm violence by race and place in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: a cartographic study. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):371-373. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Polcari AM, Hoefer LE, Callier KM, et al. Social vulnerability index is strongly associated with urban pediatric firearm violence: an analysis of five major US cities. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;95(3):411-418. doi: 10.1097/ta.0000000000003896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jacoby SF, Dong B, Beard JH, Wiebe DJ, Morrison CN. The enduring impact of historical and structural racism on urban violence in Philadelphia. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:87-95. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Magee LA, Ray B, Huynh P, O’Donnell D, Ranney ML. Dual public health crises: the overlap of drug overdose and firearm injury in Indianapolis, Indiana, 2018-2020. Inj Epidemiol. 2022;9(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s40621-022-00383-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sampson RJ, Groves WB. Community structure and crime: testing social-disorganization theory. Am J Sociol. 1989;94(4):774-802. doi.org/10.1086/229068 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV. Race/ethnicity, gender, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: a comparison of area-based socioeconomic measures—the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1655-1671. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.10.1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mercy JA, Ikeda R, Powell KE. Firearm-related injury surveillance: an overview of progress and the challenges ahead. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15(3 suppl 1):S6-S16. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00060-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mills B, Hajat A, Rivara F, Nurius P, Matsueda R, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Firearm assault injuries by residence and injury occurrence location. Inj Prev. 2019;25(suppl 1):i12-i15. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2018-043129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Public Health–Seattle & King County. Geographical definitions. 2024. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://kingcounty.gov/en/legacy/depts/health/data/community-health-indicators/definitions.aspx

- 18. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. CDC SVI documentation 2020. 2022. Accessed December 1, 2023. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/documentation/SVI_documentation_2020.html

- 19. US Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2016-2020 5-year data release. 2022. Accessed December 1, 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2021/acs-5-year.html

- 20. Bilal U, Tabb LP, Barber S, Diez Roux AV. Spatial inequities in COVID-19 testing, positivity, confirmed cases, and mortality in 3 U.S. cities: an ecological study. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(7):936-944. doi: 10.7326/M20-3936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fotheringham AS, Wong DW. The modifiable areal unit problem in multivariate statistical analysis. Environ Plann A Econ Space. 1991;23(7):1025-1044. doi: 10.1068/a231025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Van Dyke ME, Chen MS, Sheppard M, et al. County-level social vulnerability and emergency department visits for firearm injuries—10 U.S. jurisdictions, January 1, 2018–December 31, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(27):873-877. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7127a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Swope CB, Hernández D, Cushing LJ. The relationship of historical redlining with present-day neighborhood environmental and health outcomes: a scoping review and conceptual model. J Urban Health. 2022;99(6):959-983. doi: 10.1007/s11524-022-00665-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee EK, Donley G, Ciesielski TH, et al. Health outcomes in redlined versus non-redlined neighborhoods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2022;294:114696. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krieger N, Wye GV, Huynh M, et al. Structural racism, historical redlining, and risk of preterm birth in New York City, 2013-2017. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(7):1046-1053. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2020.305656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Poulson M, Neufeld MY, Dechert T, Allee L, Kenzik KM. Historic redlining, structural racism, and firearm violence: a structural equation modeling approach. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2021;3:100052. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moyer R, MacDonald JM, Ridgeway G, Branas CC. Effect of remediating blighted vacant land on shootings: a citywide cluster randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 2018;109(1):140-144. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kondo MC, Keene D, Hohl BC, MacDonald JM, Branas CC. A difference-in-differences study of the effects of a new abandoned building remediation strategy on safety. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0129582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Branas CC, Kondo MC, Murphy SM, South EC, Polsky D, MacDonald JM. Urban blight remediation as a cost-beneficial solution to firearm violence. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(12):2158-2164. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2016.303434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Public Health–Seattle & King County. King County population by age and race, 2022. Accessed September 1, 2023. https://tableaupub.kingcounty.gov/t/Public/views/KingCountypopulation/Demographics

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-phr-10.1177_00333549241301714 for Spatial Analysis of Social Vulnerability and Firearm Injury EMS Encounters in King County, Washington, 2019-2023 by Precious Esie, Jennifer Liu, Karyn Brownson, Amy J. Poel, Myduc Ta and Aley Joseph Pallickaparambil in Public Health Reports®