Abstract

Background

Japan is implementing awareness-raising of advance care planning for older adults; however, only 451 out of 1 741 municipalities were engaged in advance care planning awareness-raising activities among residents, according to a 2017 survey. This study examined advance care planning awareness-raising activities among community residents by local governments after the 2018 revision of the government guidelines, as well as utilization of the revised guidelines, issues in awareness-raising activities, and directions for future activities.

Methods

This cross-sectional questionnaire survey was conducted in prefectures and municipalities nationwide in 2022. Questions included the status, content, and issues of advance care planning awareness-raising activities for community residents. A multi-level logistic regression analysis was used to examine the characteristics of municipalities engaged in activities.

Results

Responses were received from 43 prefectures (response rate: 91.5%) and 912 municipalities (response rate: 53.1%). Of the municipalities, 63.6% (n = 580) reported “active” advance care planning awareness-raising. A high financial capability index and implementation of awareness-raising activities in the prefecture where the municipality was located were significantly associated with its awareness-raising activities. Municipalities engaged in awareness-raising activities reported experiencing issues related to the objectives, methods, and outcome evaluation of the activities.

Conclusions

Five-hundred eighty municipalities engaged in awareness-raising activities—a number that had increased significantly since the 2017 survey. Municipalities that could not engage in awareness-raising activities should receive financial support and other forms of support from prefectures. Furthermore, to ensure that municipalities clarify the purpose of awareness-raising and the desired outcomes, indices for quantitatively measuring results and achievements should be developed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12904-024-01635-9.

Keywords: Advance care planning, Awareness-raising activities, Cross-sectional survey, Financial capability index, Municipalities

Background

In Japan, the older adult population continues to increase. The number of adults aged 65 or over is predicted to reach 39.35 million, peaking by 2042 when the second baby-boomer cohort enters this age group [1]; as such, older adults’ medical and nursing care needs are expected to change significantly. The number of deaths is also showing an upward trend, with approximately 1.44 million deaths in 2021, an increase of 68 000 from the previous year [2]. The proportion of older adults requiring ambulance transportation is also steadily increasing [3]. However, unwanted ambulance transportation is conducted at the end-of-life stage because the patient’s wishes were unknown [4]. Supporting older adults’ medical and long-term care decision-making at the end of life is vital.

Within this context, the Japan Geriatrics Society published the “Recommendations for the Promotion of Advance Care Planning” in 2019, presenting clinical guidelines for correctly understanding and utilizing advance care planning (ACP) in Japan [5]. The ACP concept is indispensable as a decision-support process at the end of life for older adults in a super-aging society.

ACP establishes goals and preferences for future treatment and care that can be discussed, documented, and reviewed with families and healthcare providers [6–9]. Legal frameworks in the United States recognize advance directives, documents in which a person specifies what kinds of medical procedures or care they wish to receive (or refuse), should their decision-making capacity become impaired. In Japan, advance directives are not legally binding.

In Japan, following a 2006 incident regarding the removal of a ventilator, the “Guidelines on the decision-making process regarding medical treatment in end-of-life” were published in 2007 [10]. The revised guidelines published in 2018 incorporate the ACP concept and address the importance of providing appropriate information to patients and their families, as well as individual decision-making, based on thorough discussions with patients, families, and medical professionals.

However, after the publication of the guidelines, there has not been much progress in promoting ACP. An awareness survey conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in December 2017 showed that 75.5% of community residents did not know about ACP. Considering the proportion of respondents who stated that they have heard of ACP but do not know much about it (19.2%), more than 90% of Japanese citizens were unaware of ACP [11]. Furthermore, previous research showed that only 451 out of 1 741 municipalities (25.9%) were engaged in ACP awareness-raising activities among community residents and that local governments with lower (vs. higher) financial capability were less likely to engage in such activities [12].

A governmental expert committee report discussed how to engage in ACP awareness-raising activities at the end-of-life stage, emphasizing the necessity of ACP awareness-raising among community residents by municipalities through the distribution of leaflets and seminars [13]. Following the publication of the revised guidelines, “Guidelines on the decision-making process regarding medical treatment in end-of-life” [14], the government disseminated information involving local governments and related organizations. These activities included creating leaflets and organizing events for ACP awareness-raising and provided financial support to help prefectures and municipalities proceed with projects that include awareness-raising to community residents.

As Japan has become a long-lived society, it is becoming increasingly important to support older adults and enable them to live as they wish at the end-of-life stage. ACP is therefore essential in Japan, and it is predicted that the number of prefectures and municipalities that engage in ACP awareness-raising activities for community residents will increase. However, since the revised guidelines were published in 2018, no surveys targeting local governments in Japan have been conducted; therefore, the circumstances are unclear. Moreover, the role of prefectures in municipalities’ awareness-raising activities, content of activities conducted, and issues involved in these activities have not yet been clarified. The local government system in Japan consists of two levels: prefectures (n = 47) and the municipalities (n = 1718) that make up the prefectures. Prefectures are regional authorities that oversee municipalities and are responsible for broader regional administration. Municipalities are local public entities that maintain close connections with residents and manage the affairs that directly affect them. Although prefectures and municipalities form a two-tier structure, they do not have a hierarchical relationship [15].

This study investigated ACP awareness-raising activities among community residents in municipalities in Japan after the 2018 revision of the guidelines, the utilization of the revised guidelines, issues in awareness-raising activities, and directions for future activities.

Methods

Study design, setting, and participants

This cross-sectional study targeted departments overseeing home medical care in 47 prefectures in Japan and departments overseeing home medical care and long-term care cooperation promotion projects in 1 718 municipalities, including special wards.

A web-based survey was conducted in October 2022. Requests for completing the online survey URL were sent to prefectural departments through the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Health Policy Bureau, Regional Medical Care Planning Division. For the municipality survey, each prefecture sent a request for completing the survey with the online survey URL to all municipalities in their respective jurisdiction. Surveys were conducted by a representative working in a relevant department of long-term care in each prefecture and municipality.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the proposal was approved by the Tokyo Medical and Dental University Ethics Review Board (no. C2022-017). Informed consent was obtained from all participants by requesting them to click on a checkbox within the online platform.

Questionnaire

Survey items were developed based on a 2017 [12] survey and the governmental expert committee’s final report [13] by a research group that included medical and nursing researchers, physicians routinely involved in end-of-life and emergency care, and government policymakers.

Survey items included (1) local government name, status of ACP awareness-raising activities for residents (“Active,” “Inactive,” “Under consideration”), year of the start of awareness-raising activities, and reasons for not conducting awareness-raising activities (free-format comments); (2) status of project development regarding ACP awareness-raising, as of FY2022 (“Project developed,” “Project developed in the past but not developed this fiscal year,” “Project not developed”); (3) specific ACP awareness-raising activities; and (4) issues faced by local government in awareness-raising (free-format comments). Prefecture and municipality names were converted to IDs.

Statistical analysis

First, we stratified the data according to the status of ACP awareness-raising activities for community residents in the municipality. We then gathered municipality-level descriptive statistics from the Japanese government statistics portal site: financial capability index (FCI), total population, population density, percentage of population 65 years or older, average age, and percentage of deaths at home. The FCI indicates the financial strength of local governments and is the average of the figures obtained by dividing the standard financial revenue by the standard financial demand over the past three years. A higher FCI value indicates that more financial resources are available [15].

The following descriptive statistics were provided for municipalities engaged in awareness-raising activities: year of the start of awareness-raising activities, specific ACP awareness-raising activities, and status of guideline utilization (“Utilizing,” “Planning to utilize,” or “Not utilized”).

We examined the characteristics of municipalities engaged in ACP awareness-raising activities for community residents by including the dependent variables, “Active” and “Inactive” (which includes “Inactive” and “Under consideration”). We conducted a bivariate analysis to examine municipalities’ relationship with FCI, total population, population density, percentage of the population aged 65 years or older, average age, and percentage of deaths at home.

Next, we confirmed the correlation between the independent variables and selected the variables to be included in the model for the multivariate analysis. “Percentage of population aged ≥ 65 years” and “Total population” or “FCI” were strongly correlated; therefore, we eliminated “Percentage of population aged ≥ 65 years” from the model. Municipality-level FCI, total population, population density, percentage of deaths at home, and the status of ACP awareness-raising activities in the prefecture where the municipality was located were set as independent variables. These variables were used in the multi-level logistic regression analysis. A data analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata version 16 (StataCorp LP. USA).

Finally, a qualitative descriptive analysis was performed regarding “Reasons for not conducting awareness-raising activities” and “Issues faced by local governments in awareness-raising.” The written descriptions were semantically separated, and respondents’ expressions were utilized and coded. The codes were based on similarities and differences and were sorted into subcategories, which were then interpreted and aggregated into broader generic categories. During the qualitative data analysis process, three authors (MK, NM, MT) with experience in qualitative research held several discussions to ensure the appropriateness of the analysis. To maintain consistency, there was a continuous back and forth crosschecking between the transcripts, codes, subcategories, and generic categories. Regarding “Issues faced by local governments in awareness raising,” the extracted categories were divided into “resources/inputs,” “activities,” and “outputs” themes using the logic model components [16]. To reach a consensus, the research group discussed the findings.

Results

We received responses from 43 of 47 prefectures (response rate: 91.5%) and 912 of 1 718 municipalities (response rate: 53.1%). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the municipalities and the status of ACP awareness-raising activities in the prefectures in which they were located. Regarding ACP awareness-raising among residents, municipalities that responded with “Active,” “Inactive,” and “Under consideration” accounted for 63.6% (n = 580), 25.1% (n = 103), and 11.2% (n = 229) of the total, respectively. Municipalities that used the ACP guidelines revised in 2018 accounted for 32.1% (n = 186) of the “Active” municipalities. The free-comment data analysis results extracted 234 codes as reasons for not conducting awareness-raising activities from the 29 subcategories (Additional file 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of target municipalities

| ACP awareness-raising activities for community residents | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active (n = 580) | Inactive (n = 103) | Under consideration (n = 229) | |||||||

| Median | 25–75 percentile | Median | 25–75 percentile | Median | 25–75 percentile | ||||

| Municipality characteristics | |||||||||

| Financial capability index | 0.59 | 0.39 | 0.82 | 0.39 | 0.26 | 0.66 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.56 |

| Total population | 47 886.5 | 16 988.0 | 116 083.0 | 17 638.0 | 6 610.0 | 46 530.0 | 19 922.0 | 9 682.0 | 42 700.0 |

| Population density | 425.1 | 114.1 | 1528.9 | 115.4 | 33.5 | 637.5 | 127.0 | 52.9 | 419.9 |

| Percentage of population aged ≥ 65 years | 31.9 | 27.4 | 37.5 | 35.8 | 29.3 | 41.2 | 36.8 | 30.9 | 41.5 |

| Average age | 49.2 | 46.6 | 52.4 | 51.7 | 47.8 | 54.5 | 51.8 | 48.6 | 54.5 |

| Percentage of deaths at home | 15.5 | 11.9 | 19.0 | 13.3 | 9.2 | 17.4 | 12.7 | 9.8 | 17.8 |

| Status of utilization of 2018 ACP guideline (n, %) | |||||||||

| Use | 186 | 32.1 | |||||||

| Non-use | 158 | 27.2 | |||||||

| Under consideration | 236 | 40.7 | |||||||

| Prefecture characteristics | |||||||||

| Awareness-raising activities for community residents in prefecture where municipality was located (n, %) | |||||||||

| Active | 395 | 71.8 | 134 | 64.1 | 51 | 53.7 | |||

| Inactive | 125 | 22.7 | 49 | 23.4 | 33 | 34.7 | |||

| Under consideration | 30 | 5.5 | 26 | 12.4 | 11 | 11.6 | |||

Note. ACP: advanced care planning

First, the status of ACP awareness-raising activities for community residents was divided into “Active” and “Inactive,” and their associations with the characteristics of municipalities were investigated. The results showed significant associations for each (p < .001; Additional file 2). Second, after confirming that there is no multicollinearity, we conducted a multi-level logistic regression analysis with municipality factors, including FCI, total population, population density, and percentage of deaths at home, while awareness-raising activities in the prefecture (prefecture factor) were used as independent variables. The results demonstrated that municipalities with a higher FCI (adjusted odds ratio: 2.78, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.40–5.51) and where the prefecture that municipality was located engaged in ACP awareness-raising activities for community residents (adjusted odds ratio: 1.90, 95% CI: 1.25–2.90) were significantly associated with ACP awareness-raising activities for community residents (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of municipalities’ awareness-raising activities: a multi-level logistic regression analysis

| AOR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Municipality factors | ||

| Financial capability index | 2.78 | 1.40–5.51 |

| Total population | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 |

| Population density | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 |

| Percentage of deaths at home (%) | 1.03 | 1.00–1.07 |

| Prefecture factor | ||

| Awareness-raising activities for community residents in prefecture where municipality was located | 1.90 | 1.25–2.90 |

Note. AOR: adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

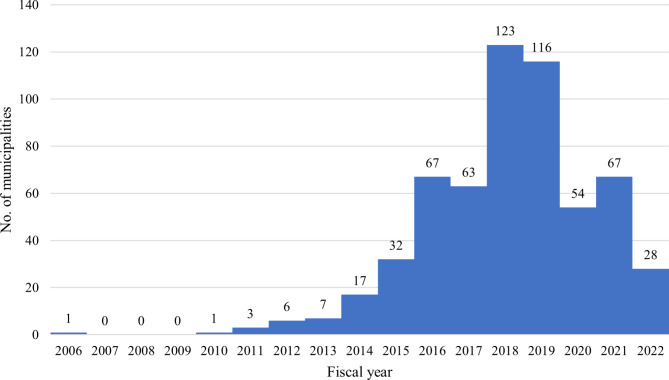

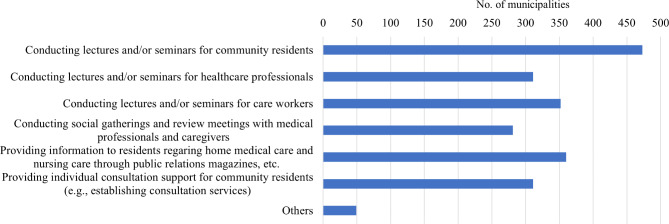

Figure 1 shows the starting year of awareness-raising activities in each municipality. The earliest year of awareness-raising activities was 2006, and the highest number of municipalities (n = 121) started these activities in 2018, when the ACP guidelines were revised. Municipalities that began their activities after 2018 accounted for 66.8% (n = 384) of the total. Regarding the activity contents, “conducting lectures and seminars for residents” was the highest at 81.5% (n = 473), followed by “providing information to resident regarding home medical care and nursing care through public relations magazines, and so on” at 62.1% (n = 360) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Fiscal year of start of awareness-raising activities (year; n = 580)

Fig. 2.

Awareness-raising method in municipalities engaged in awareness-raising activities (n = 580)

Regarding the free-response data analysis results, 56 subcategories and 10 categories were extracted from 796 codes for the issues faced by municipalities in ACP awareness-raising for community residents (Table 3). The extracted categories were classified into three themes: “resources/inputs,” “activities,” and “outputs,” and the results for the categories were as follows: for “resources/inputs,” (1) medical and nursing care service provision system, (2) system for awareness-raising in municipalities, and (3) characteristics of local residents; for “activities,” (4) knowing the target population (5) awareness-raising methods for residents, (6) lecture and workshop planning, (7) creation and utilization of media, (8) awareness-raising to related organizations and people, and (9) individual decision-making support; and for “outputs,” (10) evaluation of activities.

Table 3.

Issues faced by municipalities in ACP awareness-raising (n = 580, code = 796)

| Theme | Category | Subcategory | Number of codes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Resources/ Input |

1) Medical and nursing care service provision system | Shortage of medical and nursing personnel | 11 |

| Lack of resources in home healthcare | 50 | ||

| Coordinating system with medical institutions and medical associations | 23 | ||

| Coordinating system between medical institutions | 6 | ||

| Lack of 24-hour medical institutions and nursing care service offices | 10 | ||

| Coordinating system between medical institutions and long-term care service institutions | 14 | ||

| Coordinating system with other municipalities | 2 | ||

| Home-based end-of-life care delivery system | 10 | ||

| Individual consultation response system | 7 | ||

| 2) System for awareness-raising in municipalities | Lack of time | 12 | |

| Lack of manpower | 41 | ||

| Large burden of coordinating with related institutions | 2 | ||

| Project continuity is difficult | 3 | ||

| Securing financial resources for awareness-raising is difficult | 5 | ||

| Limitations of implementation at municipality-level | 7 | ||

| Creating mechanisms for raising awareness | 12 | ||

| 3) Characteristics of local residents | Insufficient and varied awareness of and interest in end-of-life care among residents | 36 | |

| Obtaining residents’ understanding | 7 | ||

| Residents’ resistance to end-of-life topics | 29 | ||

| Few people wishing to die at home | 6 | ||

| Activities | 4) Knowing the target population | Determining resident needs | 23 |

| Determining the status of support of medical and nursing care services | 11 | ||

| Determining whether awareness-raising is progressing | 5 | ||

| Issues related to awareness-raising are unclear | 4 | ||

| 5) Awareness-raising methods for residents | Content and methods of dissemination to residents | 102 | |

| Desire to see good examples of activities | 8 | ||

| Selection of awareness-raising targets | 6 | ||

| Timing of awareness-raising for residents | 13 | ||

| Ideal ways of explaining to residents | 15 | ||

| Consideration of dissemination content | 33 | ||

| Lack of dissemination to residents | 39 | ||

| Promotion of awareness of individual help desks | 5 | ||

| Promotion of utilization of at-home courses | 4 | ||

| Securing participants for seminars and lectures | 7 | ||

| Dissemination of long-term care insurance system and local home medical services | 2 | ||

| 6) Lecture and workshop planning | Selection of lecture themes and content | 6 | |

| Selection of lecturers | 16 | ||

| Implementation of interactive workshops | 5 | ||

| Securing means of transportation to venues | 2 | ||

| 7) Creation and utilization of media | Promotion of distribution and utilization of created media | 23 | |

| Creation of explanatory materials and media for residents | 7 | ||

| 8) Awareness-raising to related organizations and people | Adjustment and collaboration with related institutions | 46 | |

| Awareness-raising activities for medical professionals and caregivers | 15 | ||

| Few training sessions | 6 | ||

| Low consciousness and awareness of medical professionals and caregivers | 12 | ||

| Lack of knowledge, experience, and skills among organizers | 25 | ||

| 9) Individual decision-making support | Individual response for cases with complicated family relationships | 2 | |

| Individual response for cases with financial problems | 2 | ||

| Timing of individual support | 2 | ||

| Respect people’s wishes | 8 | ||

| Decision-making support for people with impaired judgment | 3 | ||

| Response when intention changes | 2 | ||

| Care that respects the patient’s wishes after loss of decision-making ability | 2 | ||

| Response when there are differences between the patient’s and their family’s opinions | 5 | ||

| Outputs | 10) Evaluation of activities | Setting of evaluation indicators | 13 |

| Methods of activities and outcome evaluation | 24 |

Note. ACP: advanced care planning

Discussion

Municipalities in Japan that implemented ACP awareness-raising activities for residents accounted for 63.6% (n = 580) of the total. The number and percentage of municipalities implementing awareness-raising have increased significantly, compared to those in the survey conducted prior to the publication of the 2018 revised guidelines (n = 451, 36.4%) [12]. To our knowledge, this was the first study to investigate ACP awareness-raising activities in municipalities after the 2018 revision of the guidelines. Many municipalities started activities in 2018–2019; this indicates that the revised guidelines [14] and activities of related organizations, such as the government and academic societies, contributed to the promotion of awareness-raising activities in municipalities.

The results of the multi-level analysis show that characteristics of municipalities engaged in awareness-raising activities included high FCI, consistent with a previous study [12], as well as being located in prefectures that were conducting awareness-raising. These findings are novel, as they demonstrate that prefectures played an important role in municipalities’ ACP awareness-raising activities. Under Japan’s Local Autonomy Act, prefectures are positioned as wide-area local governments that include municipalities in Japan [15]. The cooperation between the prefecture and municipality, with the prefecture government using its size and access to expertise to complement and coordinate with the municipal governments that do not have a system in place to address awareness, will contribute to ACP awareness-raising activities for residents in a municipality. Furthermore, municipalities face many challenges in implementing ACP awareness-raising activities. According to the umbrella review of the barriers to ACP implementation in healthcare, these include a lack of time to discuss ACP, insufficient organizational support for ACP implementation, and a shortage of staff [17]. These findings suggest that the barriers preventing local governments from promoting ACP awareness-raising among residents may stem not only from a lack of manpower within municipalities but also from inadequate systems to support ACP implementation in healthcare.

Notably, this study clarified the issues of “resources/inputs,” “activities,” and “outputs,” in promoting ACP awareness-raising for community residents. Municipalities had many problems related to “activities,” such as not knowing the target population and awareness-raising methods for residents when municipalities promote these activities. Awareness-raising is a process that seeks to inform and educate people about a topic or issue, with the intention of influencing their attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs toward the achievement of a defined purpose or goal. Knowing the target population is vital for designing an effective campaign, and the first step is to conduct a situation analysis, which is done through baseline data collection [18]. Our results suggest that most municipalities are in the initial stages of ACP awareness-raising.

The governmental expert committee’s final report in March 2018 [13] emphasizes the need for municipalities to disseminate and raise ACP awareness for residents through leaflets and conducting seminars; however, it does not indicate the purpose and methods of awareness-raising. Furthermore, the 2018 revised guidelines provide an ideal decision-making process for medical and nursing care in end-of-life care [14]. However, these guidelines do not state clearly how municipalities should promote ACP awareness and dissemination among residents. Therefore, municipalities that adopted the 2018 revised ACP guidelines accounted for only 32.1% of active municipalities. As many municipalities face challenges in knowing the target population and how to promote ACP awareness-raising, they may need support from the national and prefectural governments, such as information about the methods of a situation analysis and pioneering cases of other municipalities. ACP must also be disseminated to all Japanese citizens, and indicators developed to recognize ACP and quantitatively measure the outcomes of these activities in a nationwide survey. In countries such as Canada and the United Kingdom (UK), various initiatives have created ACP resources and processes to engage the public directly through community-oriented approaches [19–21]. Local governments in Japan also need to consider ACP strategies that truly engage with residents on the community level rather than merely distributing leaflets and conducting seminars.

In the “Resources/ Input,” the results show that the construction of the “comprehensive community care system including a medical and nursing care service provision system,” which is the external environment that surrounds ACP, is an important issue. Further, “characteristics of local residents” were extracted. The ACP concept has gradually become known in Japan, and approximately 70% of Japanese adults have a positive attitude toward participating in ACP [22]. As Japan is a high-context culture with a communication style that relies on context rather than words, there is a tendency to avoid stating one’s wishes explicitly [23, 24]; family-centered decision-making is emphasized. Moreover, some fear that stating personal opinions would burden their family [25]. Our result indicates the difficulty of promoting ACP awareness among Japanese people, considering these characteristics. Therefore, it may be necessary for the municipal government to not only inform residents but also implement measures to support decision-making by those close to them, such as their family doctor.

This study has several limitations. First, 912 municipalities participated in this survey; using all 1 718 municipalities as the denominator, the response rate was 53.1%, which was lower than that of the 2017 survey. This could be owing to the eighth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan at the time of this study. In addition, the results of comparing the characteristics of the included municipalities with those of municipalities nationwide showed that the studied municipalities had slightly larger populations and population densities (Additional file 3). Therefore, the number of municipalities engaged in awareness-raising activities could have been underestimated. The results suggested the possibility of many municipalities engaging in awareness-raising activities through trial and error. However, the study did not collect data on implementation methods or target groups for these activities. It is essential to clarify these details in future studies. This will require the development of indices to quantitatively measure results and achievements. Moreover, it is important to determine whether there have been any changes in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among residents, patients, and caregivers in areas where ACP awareness-raising activities have been implemented.

Conclusions

This study was the first nationwide survey in Japan to investigate the status of ACP awareness-raising activities for community residents in municipalities since the revision of the ACP guidelines in 2018. The number of municipalities engaged in awareness-raising activities increased significantly from 2018. This study demonstrated that prefectures and FCI played an important role in municipal activities. Municipalities that did not engage in awareness-raising activities should continue to be provided with financial support from the national government, as well as support from prefectures. Further, the government must clarify the objective and expected outcomes of awareness-raising and provide indicators to quantitatively measure results and performance.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Additional file 1: Table SI. Reasons for not conducting ACP awareness-raising activities (n = 103, code = 234)

Supplementary Material 2: Additional file 2: Table SII. Characteristics of municipalities’ awareness-raising activities for community residents: a bivariate analysis

Supplementary Material 3: Additional file 3: Table SIII. Comparison of this study and nationwide municipalities

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACP

Advance care planning

- FCI

Financial capability index

Author contributions

MK, NM, KH, TS, RI, and NT: study concept and design; MK and NM: data acquisition; MK, NM, and MT: data analysis and interpretation; MK and NM: manuscript preparation; MK, NM, MT, KH, TS, RI, and NT: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (grant nos. 22CA2028 and 23IA1005) and JSPS KAKENHI (grant no. JP20H04011). The funders did not contribute to the study design, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The requirement for informed consent was waived because providing a response was considered consent, and the study protocol was approved by the Tokyo Medical and Dental University Ethics Review Board (no. C2022-017).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.National Institute of Population and Social Security Research in Japan (IPSS). Population Projections for Japan: 2016 to 2065. https://www.ipss.go.jp/pp-zenkoku/e/zenkoku_e2017/pp_zenkoku2017e_gaiyou.html. Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

- 2.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Vital statistics of Japan 2021. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/geppo/nengai21/dl/gaikyouR3.pdf (in Japanese). Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

- 3.Fire and Disaster Management Agency. Current status of emergency rescue. 2022. https://www.fdma.go.jp/publication/rescue/post-4.html (in Japanese). Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

- 4.Sugiura M, Ohira S, Tanaka T. DNAR order in end-of-life cancer patients and the actual state of emergency transportation. J Jpn Assoc Acute Med. 2018;29:125–31. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Japan Geriatrics Society Subcommittee on End-of-Life Issues, Kuzuya M, Aita K, Yoko K, Tomohiro K, Mitsunori N, et al. Japan geriatrics society recommendations for the promotion of advance care planning: end-of-life issues subcommittee consensus statement. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20(11):1024–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, van Delden JJ, Drickamer MA, Droger M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e543–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, Hanson LC, Meier DE, Pantilat SZ et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:821 – 32.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Miyashita J, Shimizu S, Shiraishi R, Mori M, Okawa K, Aita K, et al. Culturally adapted consensus definition and action guideline: Japan’s advance care planning. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;64:602–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chikada A, Takenouchi S, Nin K, Mori M. Definition and recommended cultural considerations for advance care planning in Japan: a systematic review. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2021;8:628–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Guidelines on the decision-making process for end-of-life care. 2007. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2007/05/dl/s0521-11a.pdf (in Japanese). Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

- 11.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The 2017 survey on attitudes toward medical care in the final stage of life (Finalized). 2017. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-10801000-Iseikyoku-Soumuka/0000200749.pdf (in Japanese). Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

- 12.Kashiwagi M, Tamiya N. Awareness-raising activities for community residents about decision-making regarding end-of-life care: a nationwide survey in Japan municipalities. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20:72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Special committee on the way of dissemination and awareness of medical care in the last stage of life. Report on the State of Dissemination and Awareness of Medical Care and Care in the Last Stage of Life. 2018. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-10801000-Iseikyoku-Soumuka/0000200748.pdf (in Japanese). Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

- 14.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Guideline on the decision-making process regarding medical treatment in end-of-life. 2018. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/04-Houdouhappyou-10802000-Iseikyoku-Shidouka/0000197701.pdf (in Japanese). Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

- 15.Local Self-government Law. 2023. https://elaws.e-gov.go.jp/document?lawid=322AC0000000067 (in Japanese). Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

- 16.W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Logic model development guide. 2003. https://hmstrust.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/LogicModel-Kellog-Fdn.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

- 17.Poveda-Moral S, Flco Pegueroles A, Ballesteros-Silva MP, Bosch-Alcaraz A. Barriers to advance care planning implementation in health care. An umbrella review with implications for evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2021;18:254–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sayers R. Principles of awareness raising for information literacy: a case study. Communication and Information, UNESCO. 2006. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000147637. Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

- 19.Matthiesen M, Froggatt K, Owen E, Ashton JR. End-of-life conversations and care: an asset-based model for community engagement. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4:306–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter RZ, Siden E, Husband A, Barwich D, Soheilipour S, Kryworuchko J, et al. Community-led, peer-facilitated Advance Care Planning workshops prompt increased Advance Care Planning behaviors among public attendees. PEC Innov. 2023;3:100199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biondo PD, King S, Minhas B, Fassbender K, Simon JE. How to increase public participation in advance care planning: findings from a World Café to elicit community group perspectives. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Omomo M, Tsuruwaka M. Factors promoting ACP and factors hindering ACP. An analysis of the care process and specific support of home care nurses for elderly people living alone. J Jpn Assoc Bioeth. 2018;28:11–21. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumura S, Bito S, Liu H, Kahn K, Fukuhara S, Kagawa-Singer M, et al. Acculturation of attitudes toward end-of-life care: a cross-cultural survey of Japanese americans and Japanese. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:531–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyashita J, Kohno A, Cheng SY, Hsu SH, Yamamoto Y, Shimizu S, et al. Patients’ preferences and factors influencing initial advance care planning discussions’ timing: a cross-cultural mixed-methods study. Palliat Med. 2020;34:906–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimada C, Hirayama R, Wakui T, Nakazato K, Obuchi S, Ishizaki T, et al. Reconsidering long-term care in the end-of-life context in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(Suppl 1):132–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Additional file 1: Table SI. Reasons for not conducting ACP awareness-raising activities (n = 103, code = 234)

Supplementary Material 2: Additional file 2: Table SII. Characteristics of municipalities’ awareness-raising activities for community residents: a bivariate analysis

Supplementary Material 3: Additional file 3: Table SIII. Comparison of this study and nationwide municipalities

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.