Abstract

Background

This exploratory study applied Q methodology to identify the types of family caregivers of older adults in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic based on their perceptions of the caregiving role and explore each type’s characteristics.

Methods

Q statements were derived from in-depth interviews and a review of prior research. Q sorting was conducted using 39 P samples on a nine-point scale to determine Q distributions according to the degree of subjective agreeableness for each statement. In-depth interviews were conducted to determine why the subjects rated statements on either extreme.

Results

Four types of family caregivers were identified as a result of an analysis using the PC QUANAL program: caregiving-positive type (type I), caregiving-ambivalent type (type II), nursing home dependent type (type III), and caregiving conflict burnout type (type IV).

Conclusion

The study results can help develop interventions and strategies based on perceptions of caregiving and their associated characteristics to provide psychological support to family members of older adult care home residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, the following measures are recommended: continuous follow-up research on specific measures facilitating communication between nursing home staff and family caregivers in the event of a pandemic; development of tools for measuring burnout risk among family caregivers and practical interventions for those at high risk; efforts to improve the image of older adult care homes and change the conventional perceptions of caregiving.

Keywords: COVID-19, Family caregivers, Nursing homes, Emotions, Q sort

Background

In South Korea, the number of people aged 65 years and older, which accounted for 17.5% of the total population in September 2022, is expected to increase to 46.4% by 2070. In response to the rapid demographic shift toward an aging population, the Korean government introduced a long-term care insurance system in 2008; as of 2021, 4,057 senior care facilities were operating nationwide [1]. The criteria for admission to long-term care facilities in South Korea are based on the Elderly Long-Term Care Insurance Act, which classifies elderly individuals into five levels based on the extent of physical, mental, and cognitive support they require. Each level is assessed based on the individual’s ability to perform daily activities and their support needs. Level 1 is the most severe, while Level 5 is the least severe. The cognitive support level means the individual has mild dementia and is not included in the five levels. Levels 1–2 are for seniors with severe physical and mental conditions who need overall assistance with daily activities; Level 3 is for those who are partially independent but need significant assistance with daily activities. Therefore, long-term care facilities usually house individuals in the 1–3 category, while those in the 4–5 and cognitive support categories use home care services by default [2, 3]. With the introduction of long-term care insurance programs, families are increasingly caring for institutionalized seniors through caregiving visits instead of caring for them at home. Thus, family caregivers (FCs) are taking on new roles, including providing social and emotional support to the elders, procuring necessary goods, and supervising and managing care [4].

Caregiving perception refers to caregivers’ subjective caregiving experience as a cognitive and emotional response during the caregiving process [5]. It can be classified into negative caregiving burden and positive caregiving satisfaction [6, 7]. Caregiving positivity refers to positive feelings associated with caregiving, such as personal satisfaction, reward, joy, and finding meaning in the role of the caregiver [7]. Satisfaction [8] and benefits [9] entail personal growth and self-acceptance. Rewards [10] include various aspects of benefits gained from the caregiving experience, and achievement [5] refers to the improvement of the caregiver’s capabilities. The burden of caregiving can be categorized as economic, physical, emotional, and social [11]. Furthermore, these components are interrelated, with an increased burden in one area often leading to strain in other areas [12].

FCs experience caregiving burdens and satisfaction [13]. Previous studies on caregiving perceptions in South Korea examine the ambivalence of FCs who directly support older adults [14] and the subjectivity of caregiving among family members of older adults with dementia who use daycare centers and nursing homes [15]. However, there is a lack of research on perceptions of caregiving that focuses on the FCs of older adults living in long-term care facilities. Moreover, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, elderly care facilities in South Korea restricted visits in accordance with the social distancing policy from February 2020 [16], and non-contact visits were allowed for individuals who received vaccination [17]. Nevertheless, due to the emergence of different variants of the virus, the restrictions lasted for more than two years until the second half of 2022 [16]. From a physical perspective, measures such as disruptions to communal activities and restrictions on visitation due to the pandemic have been shown to have led to reduced physical activity and limited opportunities for exercise among institutionalized older adults, resulting in decreased muscle strength, weight loss, and poorer physical functioning [18]. Furthermore, when examining the impact of the pandemic on FCs, studies from the UK, the US, and the Netherlands show that during the pandemic, visitation restrictions, infection fears, and lack of information in care facilities significantly increased FCs’ distrust of elderly care facilities, psychological burden, stress, and anxiety. Consequently, there were significant changes in their caregiving perceptions, with them feeling more responsible than before and considering providing care themselves [19–21].

South Korea has experienced several epidemics of infectious diseases, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003, avian influenza in 2006, and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2015 [22]. During the MERS epidemic, visits were restricted at the discretion of elderly care facilities [23], but no relevant studies were found due to the short duration of the epidemic. As infectious diseases are increasingly entering the country due to business globalization, tourism, and climate change, the possibility of outbreaks is increasing, and epidemics will likely occur repeatedly due to changes in the social environment, which continues to have a serious impact [22]. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the perceptions of FCs of elderly care facility residents in the context of infectious disease outbreaks.

However, FCs have various reactions to the placement of an older adult in a facility: some are indifferent to the individual, while others are extremely supportive; some have a surveillance-like attitude toward the facility staff, making constant complaints and demands. Further, some enter into conflicts with the facility management staff, creating problems for the workers [24]. Most FCs report a decrease in burden and an improvement in quality of life after placing their elderly kin in a facility [25]. Nevertheless, when conflicts between FCs and nursing home staff arise and persist, it negatively affects FCs’ satisfaction with the nursing home [26]. In particular, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused new conflicts between FCs and elderly care facility staff. FCs’ trust in these facilities has decreased due to visitation restrictions and lack of communication [21]; FCs have expressed dissatisfaction with the management’s response to outbreaks in elderly care facilities [27]. In some cases, FCs perceived that the quality of care had degraded as the pandemic exacerbated staffing shortages in elderly care facilities [28], and poor communication between families and facilities during the pandemic led to mistrust and conflict due to a lack of information [29, 30]. The relationship between FCs and facility staff that deteriorates due to prolonged conflict is a critical issue, especially in the context of a pandemic, as it affects facility staff’s work stress, staff turnover, and the quality of care provided by the facility [31].

Therefore, this study explores the subjectivity and diversity of FCs’ caregiving perceptions to understand them better and provide effective caregiving services to older adult family members in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we identify the types of caregiving perceptions of FCs during the special circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, we hope to minimize emotional conflicts between elderly care facility staff and FCs and provide a basis for developing emotional interventions and strategies for each type. Thus, this study (1) assesses the perceptions of caregiving held by FCs of older adults placed in nursing homes and (2) classifies FCs based on the characteristics of their caregiving perceptions.

Methods

This exploratory study applied Q methodology to identify, categorize, analyze, and describe the subjectivity of caregiving perceptions of FCs in elderly care facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Q methodology is designed to analyze subjective perceptions scientifically and is used for systematically exploring and categorizing an individual’s views, attitudes, and beliefs. It is particularly suitable for exploring complex issues or eliciting multiple perspectives and types of perceptions [32]. This study systematically analyzed the perceptions of caregiving experienced by FCs of older adults placed in nursing facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the Q methodology was deemed the best methodology to understand these caregivers’ subjective perceptions specifically and elicit the complex perceptions that emerged during the pandemic.

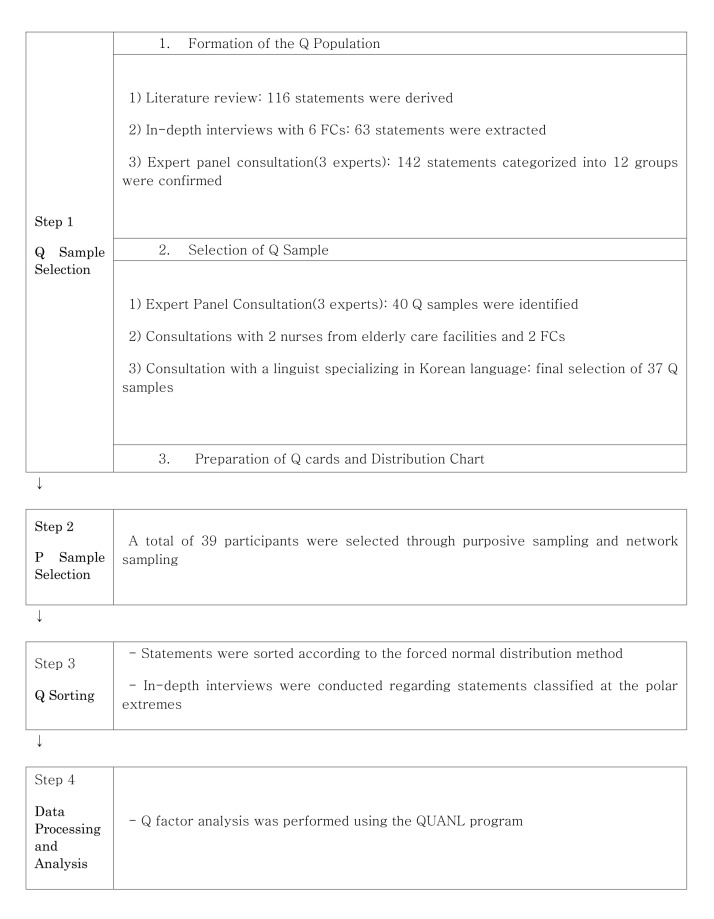

The procedure for this study is schematized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The process of this study

Q-sample selection: Constructing the Q-population and determining the Q-sample

In this study, Q statements were formed based on the data collected through a literature review and in-depth interviews on the caregiving perceptions of FCs whose older adult family members lived in care facilities.

The literature was reviewed using journals and dissertations provided by the Korea Education and Research Information Service and Google Scholar, with no restrictions on the field and year of publication. Domestic and foreign studies were extracted using the following search terms: elderly care facility, nursing facility, nursing home, family caregiver, family, care burden, care satisfaction, and experience. Studies on FCs’ experiences and perceptions of administrative aspects of nursing homes were excluded from the review, and the literature was limited to those whose themes were related to FCs’ experiences of caring for older adults, such as caregiving positivity and caregiving burden.

The following papers were included in the review: “Caregiving Burden and Care Satisfaction Instrument” [33], “Care Burden of Elderly Family Members in Nursing Facilities” [34], “Caregiving Affirmation Scale for Korean Elderly Family Caregivers” [5], “Family Members’ Experiences in Caring for Elderly People with Dementia in Long-term Care Hospitals” [35], “Family Involvement of Family Caregivers of Elders in Nursing Homes: A Phenomenological Study” [36], “A Study on the Conflict among Siblings Regarding the Long-Term Care of Elderly Parents” [37], “A Study on the Experience of a Mother-Daughter Relationship through the Process of Admission to Nursing Care Facilities” [38], and “A Qualitative Study on Caregivers’ Burden Experience for the Long-Term Care Qualified Elderly” [39].

To capture various perspectives [33, 40], in-depth interviews were conducted with six FCs (three men and three women), selected through network sampling, who had older adult family members in nursing facilities for at least one year and were their primary caregivers at the time of the interview. Relationships with the older adult residents varied, with three sons, one daughter-in-law, and two daughters. Before the interview, we found out the duration for which the older adults had lived in a nursing home, the basic status of their level of care and diagnosis, and the type of support before they entered the nursing home. The main interview questions were as follows: “What do you think about the difficulty of visiting elderly care facilities due to COVID-19?”; “What emotions do you feel when you think about your elderly loved one being in an elderly care facility?”; “How do you think your emotions have changed from the time before COVID-19 to the present day?” Additionally, the interviewees were asked to talk freely about their experiences and feelings as a family member of an older adult in an elderly care facility.

Q samples were extracted and organized in consultation with a panel of three experts with an average of 10 years each of clinical expertise and teaching and research experience. Two of the three experts had more than 15 years of experience caring for parents in their homes. We compared the 179 statements extracted from the literature and interviews, focusing on statements from the interviews, deleting redundant statements, and categorizing statements considered to belong to the same theme. Thus, we identified 12 categories and 142 statements. The categories, each identified from previous studies [7, 33–39, 41], were time burden, physical burden, social burden, economic burden, psychological burden, satisfaction, sense of personal growth, will to continue caregiving, relationship with the elderly care facility, family relationship, relationship between the older adult and caregiver, and environmental factors.

Subsequently, we selected the statements most representative of each category, yielding 40 Q samples. Moreover, we consulted with two nurses who had worked in elderly care facilities for more than three years and two FCs to check for statements that were ambiguous in meaning or inappropriate for the field. Finally, 37 Q samples were selected by checking for difficulties in understanding and refining the expression through consultation with a national literary expert.

P-sample selection

P sample is a set of research participants in Q methodology, and it is important to select people who can provide a range of opinions on a particular topic. P-sample is organized so that a few people can provide in-depth opinions, and the sample size focuses on capturing the rich diversity of views rather than seeking statistical representation [34].

The P sample of this study comprised 39 FCs. The selection criteria included individuals who had served as primary caregivers for their older adult family members in an elderly care facility for more than six months during the COVID-19 pandemic (since March 2020), understood the study’s purpose at the time of the interview, and agreed to participate. Furthermore, we limited the participants’ educational requirement to at least a high school diploma due to the necessity of understanding the research procedures. The sampling method was a combination of network and intentional sampling. To obtain a diverse sample, we did not limit the family relationship with the older adults, and we selected grandchildren and other relatives equivalent to primary caregivers based on the extent of their role as caregivers.

Q sorting

In Q-sorting, research participants categorize a given set of statements (Q-samples) according to a set of criteria; participants place each statement in an order based on the degree to which they agree or disagree with it. The result of Q-sorting is a quantification of each individual’s subjective perception, which is used to derive different perception types through statistical analysis [42].

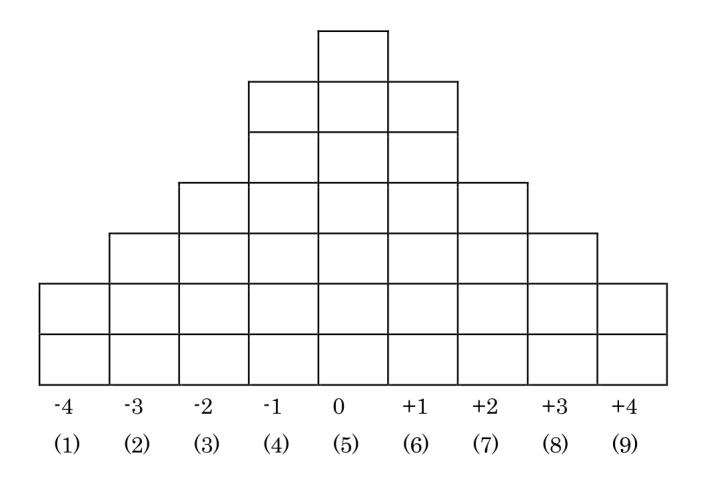

Q sorting was performed at locations selected by the participants. The study topic, purpose, Q sorting, and methods were explained, and informed consent was obtained prior to the study. An interview questionnaire was used to collect general information about the participant and the institutionalized older adults, and the participant was asked to read all 37 statements to obtain a general impression. Subsequently, the 37 statements were reread and divided into three groups: agree, neutral, and disagree; the cards categorized into the three groups were distributed on a nine-point Q distribution. The Q distribution chart was created and used as shown in Fig. 2, and Q cards were created so that statements could be placed in each column. For the 10 cards placed at the end of the spectrum (-4, -3, + 3, +4), we conducted in-depth interviews to explore why they were placed there. These interviews were recorded with informed consent. Data were collected from January to July 2022.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of the Q sample

Data analysis

The collected data were coded into a data file suitable for use with the PC QUANL program.

Coding was performed by scoring the statements in the Q sample distribution starting with 1 for the most disagreed with statement(-4), followed by 2(-3), 3(-2), 4(-1), 5(0), 6(+ 1), 7(+ 2), 8(+ 3), and 9(+ 4), and checking the number of the statement in which they were placed.

The analysis was performed using the PC QUANL program and the principal component factor analysis method. The eigenvalue, which represents the proportion of variance each factor can explain in the data, is considered significant when the factor is 1.0 or higher [40]. To determine the best number of factors, we repeated the analysis by varying the number of factors based on an eigenvalue of 1.0 or higher. Specifically, the results were calculated by selecting the factor with the highest interpretive power for the data, considering the explanatory power of each factor among the analysis results. The optimal number of factors was selected based on the point where the eigenvalue decreased sharply according to the scree plot to determine the appropriate number of factors [43].

The characteristics of each type were identified based on the standardized z-scores for the statements, general characteristics of the P samples, and statements with which they agreed or disagreed significantly differently from the other types. In-depth interviews were conducted to understand why the P samples selected the statements with which they strongly agreed or disagreed, and the naming of the types was finalized through discussions with five expert panelists based on the above analysis.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of S University (IRB NO: 2-1040781-A-N-012021051 h).

Before the interviews began, we explained in detail the study’s purpose and the nature of participation. We informed the participants that the interviews would be recorded, that the recordings would be anonymized and used only for the study, and that they would be stored for three years after the dissertation was written and subsequently destroyed. Furthermore, we explained that they could refuse to participate if they felt tired or wanted to withdraw their consent at any time during the interview. Individuals’ information was considered confidential, and identification codes were used to protect privacy.

Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, we wore masks during the interview, sat at a table at least two meters away from each other, and disinfected our hands. At the end of the interview, we thanked the participants and gave them a small gift.

Results

Formation of subjective frames of family caregiver’s perceptions of caregiving

A factor analysis of the subjectivity of FCs’ perceptions of caregiving for their older adult loved ones in long-term care facilities during COVID-19 revealed four types of factors. After analyzing different numbers of factors, four factors were found to be the most appropriate in terms of explanatory power, total variance, and correlation. The four types explained 48.77% of the total variance—31.65% for Type I, 7.27% for Type II, 5.73% for Type III, and 4.12% for Type IV (Table 1).

Table 1.

Eigenvalue, variance of types

| Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 | Type 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 12.34 | 2.84 | 2.23 | 1.61 |

| Variance (%) | 31.65 | 7.27 | 5.73 | 4.12 |

| Cumulative (%) | 31.65 | 38.92 | 44.65 | 48.77 |

Of the 37 Q statements, the one with a standardized score of + 1.00 or higher and strong agreement across all types was “33. I feel relieved that my elderly loved one is receiving 24-hour professional care in a nursing home.” The one with a standardized score of − 1.00 or less and weak agreement across all types was “9. I think it is socially shameful for one to place a family in a nursing home instead of caring for them” (Table 2).

Table 2.

Q statements and Z-scores according to type

| No | Q statements | Z-score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 | Type 4 | ||

| 1 | Since my elderly loved one was admitted to a nursing home, my quality of life has improved, as I now have more free time to do what I want in my daily life. | − 0.49 | 1.20 | 0.19 | -1.83 |

| 2 | Although my elderly loved one is in a nursing home, I feel the burden of having to spare time unexpectedly when an emergency arises. | − 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.44 |

| 3 | Although I have placed my elderly loved one in a nursing home, I feel the physical burden of fulfilling the role of a guardian. | -1.52 | − 0.47 | − 0.88 | − 0.42 |

| 4 | I feel less physically strained since I had my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home and stopped taking care of them myself. | 0.17 | 1.99 | 0.00 | 1.29 |

| 5 | It is more financially burdensome to bear the cost of nursing home care than I initially assumed. | -1.62 | 0.47 | 1.69 | − 0.86 |

| 6 | The financial burden of nursing home care has been significantly reduced due to government support. | 0.87 | 1.42 | − 0.07 | 1.74 |

| 7 | The occasional need for me to put important matters on the back burner to visit the nursing home is troubling. | -1.23 | -1.01 | − 0.05 | − 0.84 |

| 8 | I have taken an interest in government policies regarding the welfare of senior citizens since I had my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home. | 0.56 | 0.64 | 1.38 | − 0.14 |

| 9 | I think it is socially shameful for one to place a family in a nursing home instead of caring for them. | -1.45 | -2.14 | -1.85 | -1.51 |

| 10 | I often fail to pay attention to my elderly loved one in a nursing home due to my busy schedule, but I think that is inevitable. | − 0.16 | 0.98 | 1.29 | 0.98 |

| 11 | I am always worried about how my elderly loved one is doing, although not as gravely as when I was caring for them myself. | 1.42 | 1.12 | 0.12 | 0.46 |

| 12 | I am afraid my relative in a nursing home may think that the family abandoned them. | 0.24 | 0.41 | − 0.41 | − 0.72 |

| 13 | I am afraid that the family and I may fail to be by my elderly loved one’s side when they pass away. | 0.87 | − 0.46 | -1.47 | 1.31 |

| 14 | Though the physical stress has been alleviated since I had my elderly loved one in a nursing home, I experience more mental stress due to guilt. | -1.07 | − 0.39 | -1.62 | 0.26 |

| 15 | With uncertainty over how long my elderly loved one may have left, I feel gradually less interested in them as their time gets extended. | -1.10 | 0.64 | − 0.13 | − 0.37 |

| 16 | Sometimes I get sad while eating food as I think of my elderly loved one not being able to have their favorite food in a nursing home. | 0.83 | 0.1.17 | − 0.65 | 0.24 |

| 17 | I feel bad that my elderly loved one may be having their life meaninglessly prolonged by living in a nursing home. | − 0.14 | − 0.06 | -1.06 | 1.85 |

| 18 | It pains me that my elderly loved one’s human dignity may not be respected in a nursing home. | − 0.11 | − 0.82 | -1.05 | 0.03 |

| 19 | It is difficult to keep my elderly loved one in a nursing home instead of caring for them myself, but there is no viable alternative. | 0.84 | 1.75 | − 0.27 | 0.85 |

| 20 | I experience mixed feelings every time I visit my elderly loved one in a nursing home. | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.84 |

| 21 | I feel rewarded for being a caregiver, although I put my elderly loved one in a nursing home. | 0.46 | − 0.51 | 0.10 | -1.59 |

| 22 | The mental burden I carry becomes greater when I have not visited my elderly loved one in a nursing home for a long period. | 1.25 | 0.24 | − 0.68 | 1.60 |

| 23 | I am afraid that my elderly loved one’s condition may deteriorate in a nursing home while I am away. | 1.08 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.44 |

| 24 | I am afraid that my elderly loved one’s cognitive functions may decline in a nursing home while I am away and that they may become unable to recognize the family members. | 0.60 | − 0.55 | 1.25 | − 0.09 |

| 25 | If anything, not being able to see my elderly loved one as often as before their admission has eased my mind. | -1.58 | -1.76 | 0.23 | -1.29 |

| 26 | Since I placed my elderly loved one in a nursing home, I wonder what their life must have been like, not as a parent but as a human. | 0.93 | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.91 |

| 27 | I think the role of a guardian I need to play after placing my elderly loved one in a nursing home is what I am naturally supposed to do without the sense of obligation. | 1.39 | 0.56 | 0.16 | 0.38 |

| 28 | Although my elderly loved one lives in a nursing home now, I do not think my role has been removed; it has simply changed. | 1.42 | 0.13 | 1.85 | 0.04 |

| 29 | Having my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home and participating in their care as a guardian reminds me of how much I have grown as a person. | 0.15 | -1.83 | 0.07 | -1.43 |

| 30 | I am satisfied with a nursing home being able to do what the family cannot do for my elderly loved one. | 1.06 | − 0.49 | 1.29 | 0.47 |

| 31 | Though I have placed my elderly loved one in a nursing home, I keep an eye on how they treat her/him as I do not trust the facility. | -1.02 | − 0.41 | -2.38 | -1.23 |

| 32 | I tend not to voice my complaints to avoid conflict with a nursing home even when I am dissatisfied with the way they take care of my elderly loved one. | − 0.53 | − 0.47 | -1.34 | − 0.67 |

| 33 | I feel relieved that my elderly loved one is receiving 24-hour professional care in a nursing home. | 1.11 | 1.14 | 1.53 | 1.29 |

| 34 | Though my elderly loved one lives in a nursing home, there are times when I get distressed from being in a disagreement with another family member on how they should be cared for. | -1.35 | -1.12 | 0.47 | − 0.54 |

| 35 | I want to avoid acting as the primary guardian of my elderly loved one because there has been disagreement among family members on nursing home care. | -1.70 | -1.38 | − 0.03 | 0.18 |

| 36 | I feel at ease as all family members agree on having my elderly loved one in a nursing home. | 0.81 | − 0.99 | 0.12 | -1.15 |

| 37 | My relationship with my elderly loved one has improved since they got admitted to a nursing home, as we no longer clash every day. | − 0.51 | − 0.78 | 1.03 | − 0.92 |

Analysis of Subjective Frames on Family Caregiver’s Perceptions of Caregiving

Type I: Caregiving-positive type

Of the 39 FCs in the P sample, 21 were categorized as Type I (age range: 28–64 years, mean age: 50.5 years). Regarding the relationship with the older adults, 13 FCs were daughters or sons, and the remaining 8 were spouses, daughters-in-law, or grandchildren. Regarding at-home care, 16 of the 21 FCs had supported their older adult loved ones at home prior to placing them in a nursing facility. The length of stay in the nursing home ranged from six months to ten years (an average of four years). Regarding the levels of care, 10 residents were in Levels 1 or 2 care, and 11 were in Levels 3 or 4 care (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factor weights and characteristics of participants

| Type (n) | ID | Gender | Age (yr.) | Relationship with elderly | Elderly’s gender | Long-term care benefits (grade) | Duration of stay (m) | Factor weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | F | 53 | daughter | F | 2 | 6 | 2.23 |

| (n = 21) | 33 | M | 61 | son | F | 3 | 66 | 2.21 |

| 5 | M | 50 | son | F | 4 | 28 | 1.80 | |

| 3 | F | 56 | daughter-in-law | F | 4 | 7 | 1.59 | |

| 14 | M | 49 | son | F | 4 | 30 | 1.35 | |

| 28 | F | 36 | granddaughter | M | 4 | 18 | 1.20 | |

| 16 | M | 33 | grandson | F | 2 | 72 | 1.15 | |

| 18 | M | 64 | son | F | 1 | 84 | 1.10 | |

| 34 | F | 54 | daughter-in-law | F | 2 | 114 | 1.06 | |

| 7 | F | 51 | daughter-in-law | F | 3 | 48 | 0.95 | |

| 12 | F | 47 | daughter-in-law | F | 1 | 6 | 0.94 | |

| 8 | M | 60 | son | F | 3 | 41 | 0.91 | |

| 15 | F | 48 | daughter-in-law | F | 4 | 28 | 0.84 | |

| 24 | M | 61 | son | F | 4 | 120 | 0.84 | |

| 26 | F | 56 | daughter | F | 2 | 72 | 0.78 | |

| 19 | F | 54 | daughter-in-law | F | 4 | 36 | 0.67 | |

| 2 | F | 52 | daughter | F | 1 | 96 | 0.62 | |

| 37 | M | 52 | son | F | 1 | 12 | 0.61 | |

| 31 | M | 28 | son | M | 1 | 84 | 0.57 | |

| 13 | F | 37 | daughter | F | 4 | 18 | 0.51 | |

| 30 | F | 59 | spouse | M | 1 | 84 | 0.50 | |

| 2 | 39 | F | 33 | granddaughter | F | 2 | 28 | 1.17 |

| (n = 8) | 21 | F | 27 | granddaughter | F | 4 | 60 | 0.99 |

| 11 | M | 45 | son | F | 1 | 180 | 0.94 | |

| 25 | F | 55 | daughter | F | 3 | 30 | 0.69 | |

| 27 | F | 40 | daughter | F | 4 | 36 | 0.68 | |

| 32 | F | 52 | daughter-in-law | F | 4 | 180 | 0.68 | |

| 29 | F | 60 | spouse | M | 4 | 18 | 0.48 | |

| 35 | M | 56 | son | F | 2 | 114 | 0.45 | |

| 3 | 36 | F | 53 | daughter-in-law | F | 1 | 12 | 0.89 |

| (n = 3) | 22 | F | 28 | granddaughter | F | 4 | 24 | 0.81 |

| 9 | F | 22 | granddaughter | F | 3 | 30 | 0.39 | |

| 4 | 38 | M | 39 | nephew | F | 2 | 18 | 1.59 |

| (n = 7) | 23 | F | 58 | daughter | F | 3 | 72 | 1.21 |

| 4 | F | 48 | daughter-in-law | F | 1 | 84 | 0.99 | |

| 17 | F | 25 | granddaughter | F | 2 | 10 | 0.69 | |

| 6 | M | 25 | son | M | 3 | 22 | 0.67 | |

| 1 | F | 57 | daughter | F | 1 | 96 | 0.65 | |

| 20 | F | 57 | daughter | F | 4 | 36 | 0.40 |

Type I strongly agreed with the following statements: “11. I am always worried about how my elderly loved one is doing, although not as gravely as when I was caring for them myself” (Z = 1.42). “28. Although my elderly loved one lives in a nursing home now, I do not think my role has been removed; it has simply changed” (Z = 1.42) (Table 2). The statements with which Type 1 agreed with more strongly than the other types were (Z diff ≥ + 1. 00): “36. I feel at ease as all family members agree on having my elderly loved one in a nursing home” (Z diff = 1.49). 29. “Having my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home and participating in their care as a guardian reminds me of how much I have grown as a person” (Z diff = 1.21) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Z-score differences by type

| Type | No | Q Statements | Z-Score | Average | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | I feel at ease as all family members agree on having my elderly loved one in a nursing home. | 0.82 | − 0.67 | 1.49 |

| 29 | Having my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home and participating in their care as a guardian reminds me of how much I have grown as a person. | 0.15 | -1.07 | 1.21 | |

| 5 | It is more financially burdensome to bear the cost of nursing home care than I initially assumed. | -1.62 | 0.43 | -2.05 | |

| 35 | I want to avoid acting as the primary guardian of my elderly loved one because there has been disagreement among family members on nursing home care. | -1.70 | − 0.41 | -1.30 | |

| 10 | I often fail to pay attention to my elderly loved one in a nursing home due to my busy schedule, but I think that is inevitable. | − 0.16 | 1.08 | -1.24 | |

| 2 | 1 | Since my elderly loved one was admitted to a nursing home, my quality of life has improved, as I now have more free time to do what I want in my daily life. | 1.20 | − 0.71 | 1.92 |

| 4 | I feel less physically strained since I had my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home and stopped taking care of them myself. | 1.99 | 0.49 | 1.50 | |

| 19 | It is difficult to keep my elderly loved one in a nursing home instead of caring for them myself, but there is no viable alternative. | 1.75 | 0.47 | 1.28 | |

| 30 | I am satisfied with a nursing home being able to do what the family cannot do for my elderly loved one. | − 0.49 | 0.94 | -1.43 | |

| 29 | Having my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home and participating in their care as a guardian reminds me of how much I have grown as a person. | -1.83 | − 0.41 | -1.42 | |

| 3 | 5 | It is more financially burdensome to bear the cost of nursing home care than I initially assumed. | 1.70 | − 0.67 | 2.37 |

| 25 | If anything, not being able to see my elderly loved one as often as before their admission has eased my mind. | 0.23 | -1.54 | 1.77 | |

| 37 | My relationship with my elderly loved one has improved since they got admitted to a nursing home, as we no longer clash every day. | 1.03 | − 0.74 | 1.77 | |

| 13 | I am afraid that the family and I may fail to be by my elderly loved one’s side when they pass away. | -1.47 | 0.57 | -2.04 | |

| 22 | The mental burden I carry becomes greater when I have not visited my elderly loved one in a nursing home for a long period. | − 0.68 | 1.03 | -1.71 | |

| 17 | I feel bad that my elderly loved one may be having their life meaninglessly prolonged by living in a nursing home. | -1.07 | 0.55 | -1.62 | |

| 31 | Though I have placed my family in a nursing home, I keep an eye on how they treat them as I do not trust the facility. | -2.38 | − 0.89 | -1.49 | |

| 4 | 17 | I feel bad that my elderly loved one may be having her/his life meaninglessly prolonged by living in a nursing home. | 1.85 | − 0.42 | 2.27 |

| 13 | I am afraid that the family and I may fail to be by my elderly loved one’s side when they pass away. | 1.31 | − 0.35 | 1.66 | |

| 1 | Since my elderly loved one was admitted to a nursing home, my quality of life has improved, as I now have more free time to do what I want in my daily life. | -1.83 | 0.30 | -2.13 | |

| 21 | I feel rewarded for being a caregiver, although I put my elderly loved one in a nursing home. | -1.59 | 0.02 | -1.61 | |

| 36 | I feel at ease as all family members agree on having my elderly loved one in a nursing home. | -1.15 | − 0.02 | -1.13 |

Nevertheless, statements eliciting strong disagreement were as follows: “35. I want to avoid acting as the primary guardian of my elderly loved one because there has been disagreement among family members on nursing home care” (Z=-1.70) and “5. It is more financially burdensome to bear the cost of nursing home care than I initially assumed” (Z=-1. 62) (Table 2). The same statements elicited stronger disagreement (Z diff≤-1.00) than other types: “5. It is more financially burdensome to bear the cost of nursing home care than I initially assumed” (Z diff=-2.05) and “35. I want to avoid acting as the primary guardian of my elderly loved one because there has been disagreement among family members on nursing home care” (Z diff=-1.30) (Table 4).

P sample 10, with the highest factor weight of 2.23 in Type I, was a 53-year-old woman whose mother had been in a nursing home for six months. The statement with which she most strongly agreed was as follows: “11. I am always worried about how my elderly loved one is doing, although not as gravely as when I was caring for them myself.” Her reason for choosing it was the following: “I worry because I don’t know what will happen at any time.” The statement with which she strongly disagreed was “25. If anything, not being able to see my elderly loved one as often as before their admission has eased my mind.” The reason given was as follows: “I suppose it’s understandable to feel that way, but now I know that I don’t.”

Based on the statements with which Type I agreed or disagreed and the in-depth interview data, Type I FCs do not perceive their caregiving responsibilities as a burden but as a natural part of being a family member of an older person. Furthermore, they experience rewards and growth in their caregiving role. They have a strong bond with their older adult loved ones and accept that they have caregiving roles and responsibilities, although the facility provides basic care. Additionally, Type I FCs are cooperative and conflict-free. Although they are extremely concerned about their older adult loved ones and their lives are busy, they always pay attention to their elderly kin, even when visiting is restricted for a long time (e.g., during the COVID-19 pandemic). Thus, Type I was called the “caregiving-positive type” because they actively accepted the role of caregiver in a family-like manner.

Type II: Caregiving-ambivalent type

Those categorized as Type II included 8 of the 39 FCs in the P sample (age range: 27–60 years, mean age: 46 years). Regarding relationships, four were daughters or sons, and the other four were spouses, daughters-in-law, or granddaughters. Further, six of the eight were direct caregivers at home before entering the facility. The length of stay in nursing homes ranged from 1.5 to 15 years (an average of 6.5 years). Regarding levels of care, three residents were in Levels 1 or 2 care, and five were in Levels 3 or 4 care (Table 3).

Type II strongly agreed with the following statements: “4. I feel less physically strained since I had my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home and stopped taking care of them myself” (Z = 1.99). “19. It is difficult to keep my elderly loved one in a nursing home instead of caring for them myself, but there is no viable alternative” (Z = 1.75) (Table 2). The statements Type II strongly agreed with compared to other types (Z diff ≥ + 1. 00) were the following: “1. Since my elderly loved one was admitted to a nursing home, my quality of life has improved, as I now have more free time to do what I want in my daily life” (Z diff = 1.92) and “4. I feel less physically strained since I had my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home and stopped taking care of them myself” (Z diff = 1.50) (Table 4).

However, statements they strongly disagreed with were the following: “9. I think it is socially shameful for one to place a family in a nursing home instead of caring for them” (Z=-2.14). “29. Having my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home and participating in their care as a guardian reminds me of how much I have grown as a person” (Z=-1. 83) (Table 2). The statements they strongly disagreed with compared to other types were (Z diff≤-1.00) as follows: “30. I am satisfied with a nursing home being able to do what the family cannot do for my elderly loved one” (Z diff=-1.43) and “29. Having my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home and participating in their care as a guardian reminds me of how much I have grown as a person” (Z diff=-1.42) (Table 4).

P sample 39, with the highest factor weight of 1.17 in Type II, was a 33-year-old woman whose grandmother had been in a nursing home for 2 years and 4 months. She strongly agreed with the following statement: “4. I feel less physically strained since I had my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home and stopped taking care of them myself.” Her reason for choosing it was as follows: “She’s diabetic, so sometimes she falls down, and I have to take care of her injections, keep changing her diapers, bathe her, and have someone stay with her at home; it’s hard for family members to go anywhere and work or anything like that, and now that she’s in the nursing home, I don’t have that burden.” She strongly disagreed with the following statement: “9. I think it is socially shameful for one to place a family in a nursing home instead of caring for them” She commented, “In a way, I think it’s okay because we can’t provide everything, but if it’s a place that’s a little bit better or that takes care of her properly, I think it’s better to send her there than not to take care of her properly.”

Based on the statements Type II agreed or disagreed with and in-depth interview data, Type II was more likely than other types to feel they were relieved of a burden by placing the older adults in a nursing home, but they were less likely to be satisfied with and trust the facility. They were also less likely to accept their role as caregivers and admitted to losing interest in the older adults in their busy lives. Compared to other types of caregivers, they had a more matter-of-fact approach, believed there was nothing to be ashamed of, had no realistic alternatives, and did not feel rewarded or experience personal growth due to caregiving. In particular, their distrust and dissatisfaction seemed to be influenced by visitation and movement restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, Type II was called the “caregiving-ambivalent type” based on the duality of feeling relieved and dissatisfied due to visitation restrictions.

Type III: Nursing home dependent type

Type III included 3 of the 39 participants in the P sample (age range: 22–53 years, mean age: 34.3 years). Among them, two were granddaughters, and one was a daughter-in-law, and all three had direct caregiving experience caring for elders prior to entering the facility. The mean length of stay in nursing homes was one year and ten months. Regarding levels of care, their older adult loved ones received Levels 1, 3, and 4 care (Table 3).

Type III strongly agreed with the following statements: “28. Although my elderly loved one lives in a nursing home now, I do not think my role has been removed; it has simply changed” (Z = 1.85) and “5. It is more financially burdensome to bear the cost of nursing home care than I initially assumed” (Z = 1.69) (Table 2). The statements Type III strongly agreed with compared to the other types (Z diff ≥ + 1. 00) were as follows: “5. It is more financially burdensome to bear the cost of nursing home care than I initially assumed” (Z diff = 2.37), “25. If anything, not being able to see my elderly loved one as often as before their admission has eased my mind” (Z diff = 1.77), and “37. My relationship with my elderly loved one has improved since they were admitted to a nursing home, as we no longer clash every day” (Z diff = 1.77) (Table 4).

Nevertheless, they strongly disagreed with the following statements: “31. Although I have placed my elderly loved one in a nursing home, I keep an eye on how they treat my elderly loved one as I do not trust the facility” (Z=-2.38) and “9. I think it is socially shameful for one to place a family in a nursing home instead of caring for them” (Z=-1. 85) (Table 2). The statements that were strongly disagreed with compared to other types (Z diff≤-1.00) were the following: “13. I am afraid that the family and I may fail to be by my elderly loved one’s side when they pass away” (Z diff=-2.04) and “22. The mental burden I carry becomes greater when I have not visited my elderly loved one in a nursing home for a long period” (Z diff=-1.71) (Table 4).

P sample 36, with the highest factor weight of 0.89 in Type III, was a 53-year-old woman whose mother-in-law had been in a nursing home for a year. She strongly agreed with the following statement: “8. I have taken an interest in government policies regarding the welfare of senior citizens since I had my elderly loved one admitted to a nursing home.” She said, “I wasn’t interested in it, but then I became interested because they said that the amount of money is determined according to the level of dementia.” She strongly disagreed with the following statement: “31. Although I have placed my elderly loved one in a nursing home, I keep an eye on how they treat them as I do not trust the facility.” The reason for choosing it was as follows: “I trust the nursing home because my mother was there… I trust it, so I don’t worry if I can’t visit her much these days.”

Based on the statements agreed and disagreed with and data from the in-depth interviews, Type III, a group comprising daughters-in-law and granddaughters, was found to be less resistant and less burdened than other types regarding the difficulty of visiting the older adults due to the pandemic and decline of interest in the older adult loved one due to their busy lives. Moreover, they were more satisfied and trustful of elderly care facilities than other types. They left their older adult loved ones completely to the care facilities, and although they showed an accepting attitude toward their role as caregivers, they were less worried about the older adult residents than other types and felt more comfortable with not meeting them for long periods. Thus, Type III was called the “nursing home dependent type” because they were comfortable with the visitation restrictions.

Type IV: Caregiving conflict burnout type

Type IV included 7 of the 39 individuals in the P sample (age range: 25–58 years, mean age: 44.1 years). Here, three of the seven were daughters or sons, and the remaining four were spouses, daughters-in-law, granddaughters, or nieces and nephews. Only three of the seven subjects had direct experience caring for older adults prior to admission. The average length of stay was 48.2 months. Regarding levels of care, four older adult residents were in Levels 1 and 2 care, and three were in Levels 3 and 4 care (Table 3).

Type IV strongly agreed with the following statements: “17. I feel bad that my elderly loved one may be having their life meaninglessly prolonged by living in a nursing home” (Z = 1.85) and “5. It is more financially burdensome to bear the cost of nursing home care than I initially assumed” (Z = 1.69) (Table 2). The statements they strongly agreed with compared to other types (Z diff ≥ + 1. 00) were as follows: “17. I feel bad that my elderly loved one may be having their life meaninglessly prolonged by living in a nursing home” (Z diff = 2.27) and “13. I am afraid that the family and I may fail to be by my elderly loved one’s side when they pass away” (Z diff = 1.66) (Table 4).

Nonetheless, they strongly disagreed with the following statements: “1. Since my elderly loved one was admitted to a nursing home, my quality of life has improved, as I now have more free time to do what I want in my daily life” (Z=-1.83) and “21. I feel rewarded for being a caregiver, although I put my elderly loved one in a nursing home” (Z=-1.59) (Table 2). The statements that they strongly disagreed with compared to other types (Z diff≤-1.00) were also the abovementioned statements: 1 (Z diff=-2.13) and 21 (Z diff=-1.61) (Table 4).

P sample 38, with the highest factor weight of 1.59 in Type IV, was a 39-year-old man whose aunt had been in a nursing home for 1.5 years. Although he was her nephew, he was the primary caregiver because the resident’s biological children refused to take on that role. The statement that subject 38 strongly agreed with was the following: “17. I feel bad that my elderly loved one may be having their life meaninglessly prolonged by living in a nursing home.” The reason for selecting it was as follows: “I’ve heard many elderly people around me say that once you enter a nursing home, you can’t get out until you die, so that’s where this thought comes from.” The statement that was strongly disagreed with was “36. I feel at ease as all family members agree on having my elderly loved one in a nursing home.” The reason for this response was as follows: “Her children are turning away… and oh dear, her nephew is the main caregiver.”

Based on the statements agreed or disagreed with and the in-depth interview data, Type IV caregivers tended to perceive older adult residents’ lives in nursing homes as a meaningless prolongation of life compared to other types of caregivers. In particular, they had poor family relationships, did not feel that the time burden of caregiving was reduced after entering a nursing home, and suffered from emotional distress. Rather than feeling rewarded or growing in their role as caregivers, they expected older adults to continue to deteriorate and were skeptical of government policies. Thus, Type IV was named “Caregiving conflict burnout type” to reflect their helplessness due to family conflicts and emotional burdens. Depending on the subjective situation and relationship with the older adults, the results show that some people are skeptical about older adults living in nursing facilities and their role as caregivers.

Discussion

This study found that caregiving perceptions of FCs of older adults in nursing homes can be classified into four types: caregiving-positive, caregiving-ambivalent, nursing home dependent, and caregiving conflict burnout. In this section, we analyze our findings in light of the related literature and compare them with previous studies to identify the direction of future research.

Type I – Caregiving positive type FCs with 31.65% explanatory power of the total explanatory variables can be considered the type that best explains the subjective structure of dependency perceptions of FCs in elderly care facilities in the COVID-19 situation. Compared to other types of subjects, Type I subjects had more positive attitudes toward statements related to family relationships, such as no conflict and good cooperation among family members, which is similar to the results of a previous study [44] that found that the higher the level of social support from family, relatives, and friends, the lower the burden of caregiving. The relatively low levels of conflict and cooperation in their families may have contributed to their ability to share caregiving responsibilities during difficult periods and be more accepting of situations that may be perceived as burdensome. Family relationships have been shown to be positively related to trust in elderly care facilities in which older adults are enrolled [45]. Therefore, it is expected that improving family relationships among FCs will lead to greater trust in staff and a reduction in caregiving burden.

Specifically, Type I agreed more strongly than other types with the “23. I am afraid that my elderly loved one’s condition may deteriorate in a nursing home while I am away,” a statement with which all types strongly agreed. This suggests that people tend to feel somewhat more worried and attached to their older adult loved ones owing to prolonged visitation restrictions because of COVID-19. In situations where visitation was restricted due to COVID-19, it would be beneficial to reduce the caregiving burden on FCs by allowing regular telephone consultations and video calls to ease their worries and increase their trust.

Type II – Caregiving-ambivalent type FCs acknowledged being relieved of some physical and time burdens due to the COVID-19 visitation restrictions. Furthermore, they were less likely to accept their role as caregivers and were less satisfied with nursing homes than other types of caregivers, suggesting that their trust in nursing homes had been diminished by long-term visitation restrictions. A study [46] on the change in caregiver burden before and after receiving long-term care insurance for older adults found that caregiver burden decreased in the following order: physical, social, emotional, and economic. Moreover, 85.4% of caregivers experienced an improvement in their quality of life, 84.7% a reduction in physical burden, and 92.1% a decrease in psychological burden after the introduction of long-term care services [47]. However, according to a previous study on the awareness of and preference for elderly care facilities [48], the response that parents would use elderly care facilities is significantly lower than interest in the facility. The reason given for not using elderly care facilities was as follows: “I don’t have a great impression of elderly care facility.” Additionally, a 2014 study on preferences for long-term care services for older adults by generation [49] showed that the preference for elderly care facilities was 45.8% among people in their 30s and 40s, 39.6% among those in their 50s and 60s, and 9.7% among those in their 70s and 80s, indicating a sharp decline with increasing age. As the negative perception of elderly care facilities is not disappearing, it is necessary to improve the image thereof by promoting the fact that there are cases where the burden of support is reduced by placing older adults in facilities.

Furthermore, Type II caregivers were less likely than other types to agree with the statement that they were satisfied with their elderly care facility. The in-depth interviews also indicated that visitation restrictions caused a decrease in satisfaction. Thus, Type II was more affected by the long-term visitation restrictions imposed by COVID-19. As in the case of Type I, the more restricted the visitations, the more helpful it would be to encourage telephonic or online communication between FCs and older adults and their care staff.

Type III - Nursing home dependent type FCs seem to have more modern caregiving values than other types, as they accept the role of a caregiver but feel financially dependent and have little emotional burden. Moreover, this type is highly affected by COVID-19, as it is characterized by being comfortable with visitation restrictions due to COVID-19.

A study [50] on the experiences of FCs of institutionalized older adults found that they felt relieved and grateful for the services provided by professionals such as Type III. The statements caregivers in Type III agreed with more or less than other types showed that they experienced less emotional distress than other types and trusted the care facility staff. Although they could not visit for a long time due to COVID-19, they felt comfortable and thought their relationship with the older adult had improved. This is similar to the finding that greater trust and a positive image of the elderly care facility reduce the burden of caregiving [44].

FCs may feel guilty and relieved when their loved one enters a long-term care facility because they are responsible for monitoring and evaluating the quality of care in the facility [51]. Thus, FC trust in long-term care facilities is crucial. A study on FCs’ trust in long-term care facilities found that approximately two-thirds of caregivers had a high level of trust in long-term care facilities, whereas the remaining one-third had a low level of trust [52]. One study found that FCs lost trust in facilities and staff due to the COVID-19 visitation ban, and the relationship between facility staff and FCs was disrupted [53]. Therefore, although they show a somewhat indifferent attitude, it is reasonable to assume that Type III caregivers trust elderly care facilities and delegate their caregiving roles.

Type IV – The caregiving conflict burnout type FCs were characterized by emotional and temporal caregiving burdens that were more severe than in the other types, with more family conflict than in the other types; one of the subjects reported seeking psychiatric treatment for family conflict related to elder care. From this perspective, it is unlikely that their emotional caregiving burden is entirely due to the prolonged visitation restrictions caused by COVID-19. Thus, they do not appear to be highly affected by COVID-19.

Type IV FCs responded more negatively to statements about family relationships and time burden reduction than other types, consistent with previous research [54] that found an inverse relationship between family cohesion and caregiving burden. Furthermore, FCs with poor family relationships often have poor communication among family members, and the resulting dissonance affects the facility and creates challenges for the staff caring for older adults [24]. Thus, FCs’ family relationships significantly affect the quality of life of older adults and the caregiver’s satisfaction.

A structural model study of burnout among FCs of older adults with dementia found that stress, burden, role conflict, depression, and coping ability were important variables among the factors affecting FC burnout and that family support had a significant effect on depression [55]. Type IV FCs can be considered a group at high risk of burnout, as they have a high burden of caregiving, poor family relationships, and low acceptance of their role as caregivers. Visitation restrictions due to COVID-19 may have increased their emotional burden of caregiving, which, in turn, may have increased their risk of burnout. Burnout is considered a significant factor that worsens the physical and mental health of caregivers and negatively affects the quality of care. Additionally, emergencies such as a pandemic can significantly increase existing caregiving burdens, and FCs are at increased risk of burnout as they experience additional stress, difficulty accessing resources, and social isolation due to the pandemic [56]. Considering these findings, a tool could be developed to assess the risk of burnout among FCs of older adult residents in long-term care facilities based on factors such as family relationships and provide high-risk FCs with help, such as specialized counseling at the national or administrative level, self-help group programs, and substitute caregiver services in case of emergencies. This tool may help reduce and prevent burnout. In particular, during situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic, when face-to-face visits are difficult, it is important to maintain the usual level of communication using the Internet to minimize the disruption in the FC-facility relationship.

The FCs of all four types in this study exhibited relief that their elders received professional care around the clock but were worried that their condition would deteriorate when visitation was restricted. They saw the older adult resident as a person, not merely a parent, and experienced a range of emotions during visits.

FCs of institutionalized older adults are not merely visitors but are important to the quality of life, health, and positive adjustment of older adult residents in nursing homes [36]. Even before COVID-19, visitation restrictions in nursing homes were a sensitive issue, and FCs were distrustful and dissatisfied with most nursing homes that provided limited visitation hours due to operational policies [57]. FCs face emotional burdens such as guilt for placing an older adult family member in a facility. Nonetheless, research has shown that FCs alleviate emotional burdens by interacting with the older adults in the facility through visits and providing snacks [58]. Thus, prolonged visitation restrictions due to the pandemic may be a significant event in changing FCs’ perceptions of caregiving.

International research on the experiences of older adults and their FCs in long-term care facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that, although visitation restrictions were intended to protect vulnerable older adults from infection, the social restrictions led to negative experiences, including anxiety, sadness, and fear [59]. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, measures have been implemented at the national level to allow FCs to communicate with institutionalized older adults through non-face-to-face visits and video calls. However, according to most FCs interviewed in this study, even with these measures, communication was disappointingly inadequate and limited because of the operational policies of the facilityVideo calls have been illustrated to have positive effects on facility satisfaction, depression, and self-efficacy among institutionalized older adults [18]. Thus, administrative structures should be established to facilitate video calls and non-face-to-face visits during infectious disease outbreaks to meet the needs of FCs.

The ideas that all four types of FCs disagreed with in this study are that they do not retain their dissatisfaction and talk to the facility and that they believe it is not socially inappropriate to place an older adult in a facility. Previous research [35] found that FCs keep their complaints to themselves for fear of causing harm to their older adult loved ones, which contradicts the findings of this study. A 2009 study [60] on generational differences in attitudes toward elder care found that older adult residents, the more the FCs viewed elderly care as a family obligation, which also contradicts the results of this study. Additionally, from the perspective of Koreans, who have historically valued Confucianism, family support is not a social issue but a duty that families should take for granted. Thus, placing an older adult family member in a facility is a difficult decision [61]. Comparing our results with those of a previous study, the perception of supporting older adults has changed with time. A 2019 study found that in 2006, 67.3% of people believed the family should be responsible for supporting elderly individuals. Nonetheless, this number decreased to 32.6% in 2016—newer generations expect the government and society to fulfill the role previously played by families [62].

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Owing to COVID-19, it was difficult to recruit interviewees to reflect the composition of the Q population. Therefore, subjects could not be recruited from a wide range of related fields, and we conducted in-depth interviews with only six FCs. Moreover, the participants were sampled through purposive and network sampling and needed to understand the Q classification method to enable data collection. Thus, the study was conducted on FCs with a high school diploma or higher who live in the metropolitan area. Therefore, the results of this study should be generalized and interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

This study attempted to identify changes and diversity in the dependency perceptions of FCs of older adults placed in care facilities due to the long-term restrictions on visitation owing to the COVID-19 pandemic and use them for preparing concrete measures to reduce the dependency burden and support FCs in the event of an emergency such as a pandemic. By identifying four distinct types of FCs, this study underscores the need to maintain trust between FCs and care facilities during crises, such as pandemics. The findings highlight that caregivers’ perceptions vary according to individual circumstances and environments, even when faced with similar situations.

For health care professionals, particularly nurses who work with older adult residents and their FCs, this study offers important insights into their practice. Given the central role of FCs in the caregiving process, these findings could improve the support provided to older adults and their FCs.

Based on the results of this study, we make the following recommendations. First, follow-up research should be conducted on the satisfaction and feasibility of specific interventions to facilitate communication between facility staff and FCs when infectious disease outbreaks restrict visits for extended periods. Second, statements related to caregiving burden can be particularly useful in the development of tools to assess burnout risk among FCs in long-term care facilities. Third, practical support systems for high-risk caregivers, such as counseling and substitute caregiving, should be established. Additionally, efforts to improve the public perception of elderly care facilities are necessary.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Study design, J.K., and S.H.; data collection and analysis, J.K.; drafting the manuscript, J.K.; revising the article critically, J.K., and S.H.; and writing the final version of the manuscript, J.K., and S.H. All authors have agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors have no funding to disclose.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the 1st author. The data are not publicly available due to respondents’ privacy.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sahmyook University (IRB NO: 2-1040781-A-N-012021051 h). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the start of the study. All methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations in the Ethical Declarations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.National Statistical Office. 2022 Statistics on the Elderly [Internet]. Seoul; National Statistical Office; 2022[cited 2022 October 11]. http://kostat.go.kr/assist/synap/preview/skin/miri.html?fn=d38f7102669631428173144&rs=/assist/synap/preview

- 2.National Health Insurance Service. Long-term care insurance for the elderly law. Seoul (KR): National Health Insurance Service; 2023[cited 2024. September 10]. Avaialble from: file:///Users/johnsmacbookpro/Downloads/2024_Booklet_for_the_Introduction_of_National_Health_Insurance_System%20.pdf.

- 3.Kim JH, Lee HS, Choi YS. Current status and challenges of long-term care system for the elderly. Seoul (KR): Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puurveen G, Baumbusch J, Gandhi P. From family involvement to family inclusion in nursing home settings: A critical interpretive synthesis. J Fam Nurs. 2018;24(1):60–85. 10.1177/1074840718754314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawton MP, Moss M, Kleban MH, Glicksman A, Rovine MA. Two-factor model of caregiving appraisal and psychological well-being. J Gerontol. 1991;46(4):181–9. 10.1093/geronj/46.4.P181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto N, Ishigaki K, Kuniyoshi M, Kawahara N, Hasegawa K, Hayashi K, Suhgishita C. Impact of the positive appraisal of care on quality of life, purpose in life, and will continue care among Japanese family caregivers of elderly: Analysis by Kinship type. Jpn J Public Health. 2002;49(7):660–71. 10.11236/jph.49.7_660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang YS. Study on the development of the ‘caregiving affirmation scale’ for Korean caregivers for the aged. J Korean Gerontol Soc. 2012;32(2):415–29. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawton MP, Kleban MH, Moss M, Rovine M, Glicksman A. Measuring caregiving appraisal. J Appl Gerontol. 1989;44(3):61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer BJ. Gain in caregiving experience: Where are we? What next? Gerontologist. 1997;37(2):218–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Picot SJ, Youngblut J, Zeller R. Development and testing of a measure of perceived caregiver rewards in adults. J Nurs Meas. 1997;5(1):33–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong S. The impact of the long-term care insurance on the burden of elderly caregiving. [dissertation]. Seoul: Han Young Theological University; 2010.

- 12.Kim H. Study on the burden of caregiving for family caregivers of frail elderly: A comparison between elder caregivers and general caregivers. J Welf Aged. 2007;(37):49–66.

- 13.Miyasaka K, Fujita K, Tabuch Y. A study on the positive appraisal toward caregiving of the family members who care for elderly people with dementia. Jpn Acad Gerontol Nurs. 2014;18(2):58–66. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SY, Kim BH, Jung Y, Kim SR, Cho JH, Jin KO. A study on ambivalence in caregivers of the aged. J Korean Soc Sci Study Subj. 2012;(24):193–204.

- 15.Hong MH. Subjectivity of care by family with dementia. [master’s thesis]. Gunsan: Kunsan National University; 2017. 99p.

- 16.Park JS. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the physical condition of elderly residents in nursing homes. Korean J Gerontol. 2021;41(3):211–28. 10.21300/kjgs.2021.41.3.211. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park SY, Kim HJ, Lee KH. Impact of COVID-19 variants on visitation policies in elderly care facilities. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2022;26(3):189–98. 10.12345/jkgs.2022.189-198. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee MJ, Byun SH. The effect of a video call on the facility satisfaction of the elderly in the long-term facilities banned from visiting due to COVID-19. J Humanit Soc Sci 21. 2021;12(1):2431–46. 10.22143/HSS21.12.1.172. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giebel C, Hanna K, Cannon J, Marlow P, Tetlow H, Mason S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 related social support service closures on people with dementia and unpaid carers: A qualitative study. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(7):1281–8. 10.1080/13607863.2021.1925182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savla J, Roberto KA, Blieszner R, McCann BR, Hoyt E, Knight AL. Dementia Caregiving During the Stay-at-Home Phase of COVID-19 Pandemic. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76(4). 10.1093/geronb/gbaa129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Verbeek H, Gerritsen DL, Backhaus R, de Boer BS, Koopmans RTCM, Hamers JPH. Allowing Visitors Back in the Nursing Home During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Dutch National Study Into the Experiences of Nursing Home Residents, Family, and Staff. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(7):900–e9043. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin SM, Ju CB. Infectious disease and public health policy. J Soc Sci. 2017;24(3):99–118. 10.46415/jss.2017.09.24.3.99. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin AR. Due to the spread of MERS, single workers in long term care facilities can’t even date. Financial News[Internet]. 2015 6 4 [cited 2022 10 3]; Society. [2p].https://www.fnnews.com/news/201506141418340982

- 24.Oh JJ. Care worker’s experience on families of the elderly in nursing homes. Korean Acad Care Manag. 2011;6:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L, Xu X. Effect Evaluation of the Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) System on the Health Care of the Elderly: A Review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:863–75. 10.2147/JMDH.S270454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shippee TP, Ng W, Roberts AR, Bowblis JR. Family Satisfaction With Nursing Home Care: Findings and Implications From Two State Comparison. J Appl Gerontol. 2020;39(4):385–92. 10.1177/0733464818790381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajasekaran RB, Hughes D, King D, Ang J, Theivendran K, Reilly P. Impact of COVID-19 on Care Home Admissions and Deaths in the Elderly Population. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12(5):1049–56. 10.1007/s41999-021-00521-w. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaugler JE, Mitchell LL. Reimagining Dementia Family Caregiving during and after COVID-19. J Aging Soc Policy. 2021;33(4–5):539–57. 10.1080/08959420.2021.1928328.34278980 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinvani L, Warner-Cohen J, Strunk A, Halper B, Van Houten A, Mulry CM, Kalnins K, Kozikowski A. Family Perspectives on Telehealth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Methods Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(9):2355–63. 10.1111/jgs.17230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fazio S, Pace D, Flinner J, Kallmyer B. The COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on People Living with Dementia, Family Caregivers, and Associated Services: A Comprehensive Review. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(10):1553–66. 10.1002/alz.12399. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallego-Alberto L, Losada A, Vara C, Olazarán J, Muñiz R, Pillemer K. Psychosocial Predictors of Anxiety in Nursing Home Staff. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41(4):282–92. 10.1080/07317115.2017.1370056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Churruca K, Ludlow K, Wu W, et al. A scoping review of Q-methodology in healthcare research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):125. 10.1186/s12874-021-01309-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakurai N. The moderation effects of positive appraisal on the burden of family caregivers of older people. Jpn J Psychol. 1999;70(3):203–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim EJ. Development of the care burden scale for family of elderly in nursing facilities. [dissertation]. Jinju: Gyeongsang National University; 2020. 73p.

- 35.Suh EK, Kim HR. Family members’ experience in caring for elderly with dementia in long-term care hospitals. J Korean Gerontol Nurs. 2020;22(4):335–47. 10.17079/jkgn.2020.22.4.335. [Google Scholar]

- 36.You SY, Tak YR. Family involvement of family caregivers of elders in nursing home: A phenomenological study. Korean Soc Welness. 2018;13(2):365–77. 10.21097/ksw.2018.05.13.2.365. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoo HJ. A study on the conflict among siblings regarding the long-term care of older parents. Korean J Fam Soc Work. 2013;40:63–91. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seo SH, Kim MJ. Study on the experience of mother-daughter relationship through the process of admission to nursing care facilities. J Korean Contents Assoc. 2018;18(12):161–72. 10.5392/JKCA2018.18.12.161. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seomun JH, Jung YJ. Factors related to the caregiving burden of ingormal caregivers. J Inst Soc Sci. 2011;22(4):3–30. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watts S, Stenner P, Doing. Q methodology: theory, method and interpretation. Qual Res Psychol. 2012;2(1):67–91. 10.1080/14780887.2011.595017. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim EJ, Sung KM. An integrated review on main caregiver’s burden of elderly in Korean nursing home. J Digit Converg. 2019;17(6):267–77. 10.14400/JDC.2019.17.6.267. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Younas A, Maddigan J, Moore JE, et al. Designing and Conducting Q Methodology in Implementation Research: A Methodological Discussion. Glob Implement Res Appl. 2024;4:125–38. 10.1007/s43477-023-00113-3. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaiser HF. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):141–51. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho KS, Seo YH. Influencing factors on supporters’ burden for the senile dementia elderly living in the facilities. Korean J 21st Century Soc Welf. 2012;9(2):209–29. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee HJ, Lee YJ. Exploring the relationship between trust and image of elderly care facilities recognized by a main caregiver in an elderly care facility. Korean J Fam Welf. 2021;26(3):401–24. 10.13049/kfwa.2021.26.3.2. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mo SH, Choi SY. Changes in caregiving burden of families agter using long-term care service. J Crit Soc Welf. 2013;(40):7–31.

- 47.Kim CW. A study on the social aspects of the performance of the national long-term care insurance. Korean J Soc Welf Res. 2013;34:273–96. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shin HS, Chu YC, Youn CY. A study on the awareness & preference about the elderly care facilities. J Korean Inst Rural Archit. 2009;11(4):51–8. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park CH. Comparative analysis on awarness of the married on supporting the elderly and the preference regarding the long-term care service type by generation[master’s thesis]. Gyeongju: Uiduk University; 2014Jun. Korean.

- 50.An HL. A study on experience of the caregivers of the elderly at long-term care facilities. Korean J Care Manag. 2021;4061–89. 10.22589/kaocm.2021.40.61.

- 51.Seiger Cronfalk B, Ternestedt BM, Norberg A. Being a close family member of a person with dementia living in a nursing home. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(21–22):3519–28. 10.1111/jocn.13718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boogaard JA, Werner P, Zisberg A, van der Steen JT. Examining trust in health professionals among family caregivers of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(12):2466–71. 10.1111/ggi.13107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giebel C, Hanna K, Marlow P, Cannon J, Tetlow H, Shenton J, Faulkner T, Rajagopal M, Mason S, Gabbay M. Guilt, tears and burnout-Impact of UK care home restrictions on the mental well-being of staff, families and residents. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(7):2191–202. 10.1111/jan.15181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee HK, Cho CB, Lee H. A study on caregiver/s burden and family cohesion among family primary caregivers. Fam Cult. 2018;30(2):78–104. 10.21478/family.30.2.201806.003. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joo KB. Constructing on primary caregiver’s burn out model of the senile dementia elderly. [dissertation]. Seoul: Kyung Hee University; 2009. 103p.

- 56.Caregiver Burnout: What It Is, Symptoms & Prevention. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed September 3. 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9225-caregiver-burnout

- 57.Kang HJ, Hur JS. A quallitative study on the experiences of primary caregivers of the elderly using long-term care insurance for the elderly: Focused on long-term care facility. Korean Acad Care Manag. 2022;43:57–93. 10.22589/kaocm.2022.43.57. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Inoue S. Assessment and treatment approaches for families of nursing home residents with ambivalence. Hum Reat Stud. 2010;12:11–26. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paananen J, Rannikko J, Harju M, Pirhonen J. The impact of Covid-19-related distancing on the well-being of nursing home residents and their family members: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2021;3:100031. 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2021.100031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seok JE. The differences and determinants in the perception on old-age support across generations in Korea. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2009;29(1):163–91. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee YJ, Kim JH, Kim KB. An ethnography on stigma of families having old people admitted to nursing home in Korea. J Korean Gerontol Soc. 2010;30(3):1005–20. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Park CH. Analysis on the influence factors of elderly care perception. J Korea Contents Assoc. 2019;19(3):328–35. 10.5392/JKCA.2019.19.03.328. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the 1st author. The data are not publicly available due to respondents’ privacy.