Abstract

Loss of agr function, vancomycin exposure, and abnormal autolysis have been linked with both development of the GISA phenotype and low-level resistance in vitro to thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal proteins (tPMPs). We examined the potential in vitro interrelationships among these parameters in well-characterized, isogenic laboratory-derived and clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates. The laboratory-derived S. aureus strains included RN6607 (agrII-positive parent) and RN6607V (vancomycin-passaged variant; hetero-GISA), RN9120 (RN6607 agr::tetM; agr II knockout parent), RN9120V (vancomycin-passaged variant), and RN9120-GISA (vancomycin passaged, GISA). Two serial isolates from a vancomycin-treated patient with recalcitrant, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) endocarditis were also studied: A5937 (agrII-positive initial isolate) and A5940 (agrII-defective/hetero-GISA isolate obtained after prolonged vancomycin administration). In vitro tPMP susceptibility phenotypes were assessed after exposure of strains to either 1 or 2 μg/ml. Triton X-100- and vancomycin-induced lysis profiles were determined spectrophotometrically. For agrII-intact strain RN6607, vancomycin exposure in vitro was associated with modest increases in vancomycin MICs and reduced killing by tPMP, but no change in lysis profiles. In contrast, vancomycin exposure of agrII-negative RN9120 yielded a hetero-GISA phenotype and was associated with defects in lysis and reduced in vitro killing by tPMP. In the clinical isolates, loss of agrII function during prolonged vancomycin therapy was accompanied by emergence of the hetero-GISA phenotype and reduced tPMP killing, with no significant change in lysis profiles. An association was identified between loss of agrII function and the emergence of hetero-GISA phenotype during either in vitro or in vivo vancomycin exposure. In vitro, these events were associated with defective lysis and reduced susceptibility to tPMP. The precise mechanism(s) underlying these findings is the subject of current investigations.

Antimicrobial resistance complicates the treatment of intravascular infections and other infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus (8, 24, 38) and has been amplified by rising rates of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in both community-acquired and nosocomial infections (30). The efficacy of vancomycin, the treatment of choice for MRSA, has been limited by high rates of clinical failures (13, 38), and the emergence of both partial (GISA) (14, 16, 38) and complete (6) resistance in clinical isolates.

Although the instability of the GISA phenotype in the absence of glycopeptide selective pressure (16) has prevented its genetic characterization to date, it is thought to result from global metabolic changes affecting cell wall synthesis and structure (4, 14, 16, 36, 37, 39, 40). We have recently shown that emergence of the GISA phenotype (36, 37) is associated with (i) loss of function of the accessory gene regulator (agr), a global regulon which coordinately controls exoprotein, exotoxin, and adhesin expression in S. aureus (22, 26, 32, 34); (ii) agr II polymorphism; and (iii) decreased autolysis in vitro (5, 37, 39).

We have also recently demonstrated that one of the initially described GISA strains, HIP5936 (7), is moderately resistant in vitro to killing by endogenous host cationic peptides, termed thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal proteins (tPMPs) (29). Interestingly, stable, low-level PMP resistance in vitro has also been observed in a large proportion of S. aureus bloodstream isolates from patients with endovascular infections (2, 12, 42) and persistent MRSA bacteremia despite vancomycin therapy (13). These low-level tPMP-resistant isolates also exhibited diminished autolytic activity (45). Because of these interesting in vitro-in vivo correlations, we evaluated here the potential in vitro interrelationships among (i) GISA phenotype, (ii) reduced susceptibility to tPMP-1, (iii) loss of agr function, and (iv) abnormal lysis profiles by using well-characterized and genetically related laboratory and clinical strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Laboratory strains.

The salient features of the laboratory strains are summarized in Table 1. All laboratory strains used in the present study are derivatives of RN6607 (SA502A), a previously published methicillin-susceptible, agr group II prototype S. aureus strain (22, 26). RN9120 is a previously described (26) agr knockout (agr::tetM) of RN6607. Because prior studies in our laboratories indicated that emergence of hetero-GISA phenotype in vitro results from exposure to subinhibitory vancomycin concentrations (37), single colonies of RN6607 and RN9120 were grown for two consecutive cycles (12 to 14 h) in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD) containing 1 μg of vancomycin/ml, generating RN6607V and RN9120V, respectively. Resulting bacterial suspensions were then plated on BHI plates containing 1 μg of vancomycin/ml, and individual colonies were used in further testing. Stocks of each strain were stored at −70°C until thawed for subsequent experimentation. To amplify the vancomycin hetero-GISA phenotype selected in vitro, RN6607V and RN9120V were then serially passaged in BHI containing increasing vancomycin concentrations at increments of 1 μg/ml. RN6607V was unable to grow in the presence of vancomycin concentrations greater than 4 μg/ml. RN9120V was successfully passaged serially in BHI broth containing vancomycin at up to 10 μg/ml, yielding RN9120-GISA. The derivation of these strains in vitro has been previously described in detail (37).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strainsa

| Strain | agr group/function | Comments | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RN6607b | II/+ | agr group II prototype laboratory strain | 22, 26 |

| RN6607V | II/+ | RN6607 grown in subinhibitory VAN; hetero-GISA | 37 |

| RN9120 | II/− (agr::tetM) | Isogenic agr knockout from strain RN6607 | 26 |

| RN9120V | II/− (agr::tetM) | RN9120 grown in subinhibitory VAN | 37 |

| RN9120-GISA | II/− (agr::tetM) | RN9120 serially passaged in VAN to GISA | 37 |

| A5937 | II/+ | Clinical MRSA, endocarditis (early, bloodstream) | 36 |

| A5940 | II/− | Clinical MRSA, endocarditis (late, aortic valve tissue); 50 days of VAN therapy; hetero-GISA | 36 |

A minus sign (−) indicates a loss of agr function as assessed by the loss of delta-hemolysin activity. VAN, vancomycin.

Referred to as strain SA502A in reference 15.

Clinical strains.

Clinical MRSA isolates A5937 and A5940 were obtained from cultures of a patient with aortic valve endocarditis who failed therapy with vancomycin. A5937 is the first bloodstream isolate from the patient and was obtained on 13 March 2000. A5940 is the isolate grown from valve tissue obtained at the time of aortic valve replacement performed on 3 May 2000 after 50 days of vancomycin therapy. These isolates were indistinguishable by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (27; data not shown). We have previously sequenced the entire agr locus of A5937 (GenBank accession no. AY082626) and A5940 (GenBank accession no. AY082625) and determined them to be agr group II (36). A5940 demonstrated complete loss of agr function, as evidenced by the absence of delta-hemolysin expression due to a nonsense mutation in agrA (36). Both isolates contained an identical nonsense mutation at agrB that likely truncates the AgrB protein by three amino acids (36). A5937 demonstrated levels of delta-hemolysin expression that were lower than that of RN6607, an agr group II wild-type strain (36).

All clinical strains in the present study were stored as either flash-frozen overnight growth suspensions in BHI broth in a dry ice-ethanol bath or as bacterial growth scraped from sheep blood agar plates and embedded in a BHI-agar vial by using a sterile 2-μl loop. Strains that were passaged in vancomycin in vitro (RN9120V, RN6607V, and RN9120-GISA) were grown overnight in BHI broth containing vancomycin at 1 μg/ml, flash frozen in dry ice-ethanol bath, and stored at −70°C.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

All antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed in accordance with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (formerly National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards) recommendations in Mueller-Hinton II agar (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD) with an inoculum of 104 CFU (31). Quality control of susceptibility testing was performed by using reference strains ATCC 33591 (MRSA), ATCC 25923 (methicillin-susceptible S. aureus [MSSA]), and ATCC 29213 (MSSA). As previously described, GISA was defined as any isolate with a vancomycin MIC that is >4 μg/ml and <16 μg/ml; hetero-GISA was defined as any isolate with a vancomycin MIC of ≤4 μg/ml but which exhibited subpopulations on population analysis that were able to grow in media containing >4 μg of vancomycin/ml (41).

Population analysis.

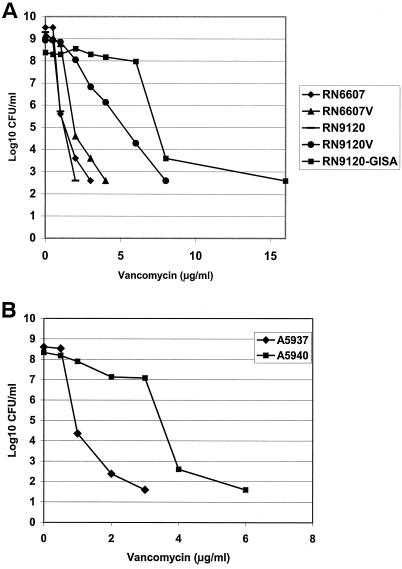

Vancomycin population analysis was performed as previously described (37). Briefly, a 109-CFU/ml suspension of bacteria was subjected to serial 10-fold dilutions (10−1 to 10−7), and 25 μl of each dilution was plated onto BHI agar containing vancomycin at 0 to 16 μg/ml. Colonies were counted after 48 h of growth at 35°C. To qualify as either a hetero-GISA or GISA isolate (depending on the vancomycin MIC) required substantial growth of subpopulations on plates containing vancomycin at ≥3 μg/ml, with eventual bacterial growth inhibition at higher vancomycin concentrations (41). Data represent the means of at least two separate assay runs. Population analyses for the five laboratory strains (Fig. 1A) have been published (37) and were included here (with permission) to provide a representative context for the newly performed lysis and platelet peptide susceptibility assays.

FIG. 1.

(A) Population analysis of MSSA laboratory strains. Strains: RN6607, agr group II wild-type parent; RN9120, agr group II knockout (agr::tetM derived from RN6607); RN6607V, RN6607 grown in vancomycin at 1 μg/ml; RN9120V, RN9120 grown in vancomycin at 1 μg/ml; RN9120-GISA, RN9120 serially passaged in increasing vancomycin concentrations of up to 10 μg/ml. (Reprinted from the Journal of Infectious Diseases [37] with permission of the publisher.) (B) Population analysis of serial clinical MRSA isolates from a patient with aortic valve endocarditis. Strains: A5937, initial bloodstream isolate; A5940, valve tissue isolate after 50 days of vancomycin therapy. In this and the subsequent figures, all data are presented as the means of at least two experimental runs. Standard error bars were not included to improve the clarity and presentation of these figures.

Triton-induced lysis.

Overnight (14- to 18-h) suspensions of bacterial cells were pelleted, washed twice with ice-cold sterile water, and grown to logarithmic phase (optical density at 630 nm [OD630] of ∼0.7) in fresh BHI broth. After another pelleting and washing step, the bacterial pellet was resuspended in Tris-HCl buffer (0.05 M; pH 7.2), with 0.05% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, to a final OD630 of 0.7. Flasks were incubated at 35°C with gentle agitation, hourly samples were obtained, and OD630 values were measured for 8 h. Autolysis was quantitated as a percentage of the initial OD630 remaining at each sampling time point. Data represent the means of three separate assays.

Vancomycin-induced lysis.

As a complement to Triton-induced lysis, the relative capacity of vancomycin to induce lysis over a 24-h exposure period was compared among the various study strains. For each strain, a 10-ml aliquot of BHI broth was inoculated from a fresh plate and cultured to log phase at 35°C with agitation until an OD630 of 0.7 was reached. Each strain was then added to fresh BHI containing a final vancomycin concentration of 50 μg/ml to achieve an initial inoculum of ∼107 CFU/ml. After we confirmed the equivalence of initial inocula, samples were incubated with agitation at 35°C for 24 h. Pilot studies demonstrated that most vancomycin-induced lysis occurred slowly and progressively over a 24-h period. Thus, aliquots were obtained at time zero and after 16, 18, and 24 h of vancomycin exposure, and OD630 values were measured. Lysis curves were then constructed comparing changes in OD630 over time. The data represent the means of three separate assays.

In vitro tPMP susceptibility profiles.

S. aureus susceptibility to tPMP was assayed in vitro as described previously (2, 12, 13), and the results are expressed as the percentage of the initial inoculum (103 CFU) surviving exposure to either 1 or 2 μg of tPMP specific activity/ml. For each isolate, tPMP susceptibility was expressed as the mean ± the standard deviation of results from two independent experimental assays performed on separate days. Preparation of tPMP, quality control and bioactivity of the preparation, and the quantitative in vitro assay methods for tPMP susceptibility phenotypes were as described in detail elsewhere (2, 12, 13). The tPMP susceptibility phenotypes were as previously defined: susceptible (<20% survival), intermediate-susceptible (21 to 50%), and resistant (>50% survival) (1, 2, 12, 13).

All lysis and tPMP susceptibility assays in vitro were performed by investigators who were located at a center separate from where the isolates were obtained and who were blinded as to the identities and microbiologic features of the isolates (N. Lucindo, M. R. Yeaman, and A. S. Bayer).

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility and population analyses.

The vancomycin MICs for the study strains are shown in Table 2. As expected, with passage in vancomycin, laboratory strains RN6607V and RN9120V exhibited modest (twofold) increases in vancomycin MICs compared to their respective parent strains, RN6607 and RN9120. With continued vancomycin passage, RN9120-GISA was derived, exhibiting a vancomycin MIC of 8 μg/ml. Vancomycin population analyses of these isogenic laboratory-derived strains (Fig. 1A and B) showed pronounced differences between the agrII-positive wild-type strain set versus the agrII-knockout strain set. Thus, only RN9120V and RN9120-GISA demonstrated substantial growth on agar containing ≥3 μg/ml, with the latter strain exhibiting the typical GISA phenotype.

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic characteristics of MRSA strains

| Strain | Vancomycin MIC (μg/ml) | tPMP susceptibility (mean % survival ± SD)a at:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 μg/ml | 1 μg/ml | ||

| RN6607 | 1 | 4.5 ± 0.7 (S) | 16 ± 1.4 (S) |

| RN6607V | 2 | 49 ± 0.7 (I) | 54 ± 4.2 (R) |

| RN9120 | 1 | 1.0 ± 0.5 (S) | 3.0 ± 1.4 (S) |

| RN9120V | 2 | 98 ± 13 (R) | 95 ± 11 (R) |

| RN9120-GISA | 8 | 93 ± 18 (R) | 89 ± 19 (R) |

| A5937 | 2 | 27 ± 4.7 (S) | 27 ± 5 (S) |

| A5940 (hetero-GISA) | 4 | 67 ± 16 (R) | 65 ± 20 (R) |

S, susceptibility; R, resistance; I, intermediate.

In the clinical MRSA strain set, the vancomycin MIC of S. aureus A5940 increased to 4 μg/ml versus 2 μg/ml in A5937, the original S. aureus bloodstream isolate. In population analyses, S. aureus A5940 exhibited a hetero-GISA phenotype (Fig. 1B).

Lysis profiles.

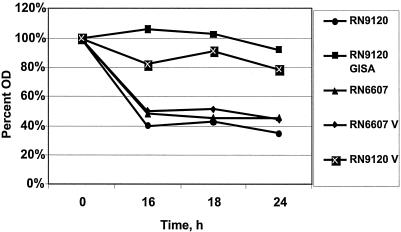

As shown in Fig. 2, parental strain RN6607 underwent substantial lysis by 16 h of vancomycin exposure. Passage of RN6607 (to derive RN6607V) did not impact vancomycin-induced lysis profiles. In contrast, in the RN9120 background, the vancomycin-passaged strains, RN9120V (hetero-GISA) and RN9120-GISA, demonstrated substantial reductions in vancomycin-induced lysis compared to the parental strain.

FIG. 2.

Lysis curves of laboratory strains in vancomycin at 50 μg/ml. The results give the OD of the bacterial suspension over time as a percentage of the OD at time zero.

Upon comparing the two clinical isolates, we found that there was only a modest diminution in vancomycin-induced lysis of strain A5940 compared to the index isolate, A5937 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Lysis curves of clinical MRSA strains A5937 (early infective endocarditis [IE]) and A5940 (late IE) in vancomycin at 50 μg/ml. The results denote the OD of the bacterial suspension over time as a percentage of the OD at time zero.

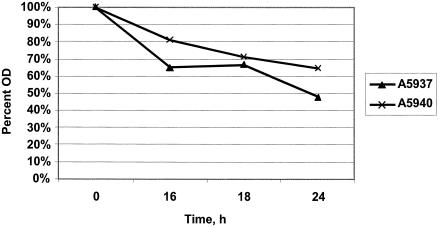

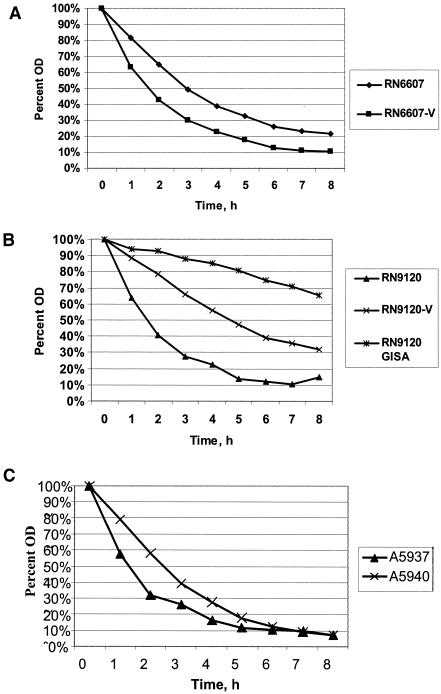

Triton-induced lysis profiles roughly paralleled those observed above with vancomycin. Thus, Triton lysis profiles did not differ substantially between strain RN6607 and RN6607V (Fig. 4A). In contrast, strains RN9120V (hetero-GISA) and RN9120-GISA were lysed more slowly and to a lesser extent than parental strain RN9120 (Fig. 4B). There were no substantive differences in Triton-induced lysis profiles between the two clinical strains (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Triton lysis curves of study strains. (A) RN6607 and RN6607V; (B) RN9120, RN9120V, and RN9120-GISA; (C) A5937 and A5940.

In vitro tPMP susceptibility assays.

Among the RN9120 strain set, vancomycin passage was associated with substantial reductions in tPMP-induced killing for both strains RN9120V (hetero-GISA) and RN9120-GISA (see Table 2). In comparison, RN6607V exhibited modest reductions in tPMP-induced killing compared to its parental strain, RN6607. Similarly, the clinical isolate, A5940 hetero-GISA, revealed reduced susceptibility to tPMP-induced killing compared to the index clinical isolate, A5937.

DISCUSSION

The isolation of clinical MRSA strains exhibiting decreased vancomycin susceptibility has now been well chronicled (5, 13, 14, 38, 41). The phenotypic and genotypic mechanisms responsible for the development of GISA remain incompletely defined but include (i) excess production of both abnormal muropeptide species and d-Ala-d-Ala residues, and thickened cell walls, which combine to negatively influence vancomycin activity; (ii) altered metabolic pathways (e.g., glutamine synthetase and l-glutamine d-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase); and (iii) defects in global regulator function (e.g., sigB, sarA, and/or agr) (3, 5, 16, 39). In addition, we and others have recently shown that GISA strains exhibit decreased autolysis in vitro (5, 37, 39). Since the agr global regulator positively regulates the expression of many murein hydrolases that are involved in autolysis, we hypothesized that defects in this operon might be involved in the development of an autolysis-deficient GISA phenotype (15).

The agr operon is involved in the coordinate regulation of a number of S. aureus virulence factors. S. aureus strains exhibit well-defined genetic polymorphisms within the agr locus. Four agr genotypes, groups I to IV, have been described to date (22, 32). Although data relating agr type and specific infections are sparse, Jarraud et al. have shown that specific agr genotype strains may be associated with particular infectious syndromes, with enterotoxin disease linked to agr group I, with endocarditis linked to agr groups I and II, with toxic shock syndrome linked to agr group III, and with exfoliative diseases linked to agr group IV (20). Recently, agr group III genotype strains have been overrepresented in strains from community-acquired MRSA infections, whereas nosocomially isolated MRSA strains in the United States are predominantly of agr group II (30, 37). Furthermore, our previous studies and those of other laboratories showed a correlation between induction of the GISA phenotype and autolytic deficiency, especially in the context of the agr genotype II (23, 37).

The genetic pathways through which agr impacts autolysis are multifactorial and not completely understood. On one hand, agr knockout mutants displayed reduced murein hydrolase activity and defective Triton-induced lysis, paralleling our current data (15). On the other hand, agr is a positive regulator of the two-component regulatory system, lrgAB, which is thought to function in the anti-holin pathway (mgrA[rat]-lytRS-lrgAB) that should theoretically would be expected to reduce murein hydrolase production and diminish lysis (18, 19). Thus, one would anticipate that loss of agr function might increase lysis via this pathway. In fact, we have previously shown that the agr group II knockout RN9120 strain derived from RN6607 exhibits an increased baseline autolysis profile compared to its parent (37). It is only after exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of vancomycin in vitro that RN9120 acquired an autolysis-deficient phenotype, whereas minimal changes in autolysis were seen in the wild type (37).

One potential explanation for this apparent paradox is that lrgAB gene products that ordinarily affect anti-holin activity may provide a holin-like function under selected physiologic conditions (17). In addition, it is conceivable that agr may impact murein hydrolase production both by the holin-antiholin pathways and more directly by the murein hydrolase structural genes. Finally, loss of agr function may simply be a marker for other, as-yet-undefined genetic defects that actually impact the autolytic pathways.

tPMPs are cationic staphylocidal peptides secreted by mammalian platelets in response to agonists present at sites of endovascular damage and infection (e.g., thrombin) (9, 10, 45, 46). Staphylococcal strains that exhibit stable, low-level in vitro resistance to killing by tPMPs appear to have a survival advantage in experimental endocarditis (9, 25, 28, 42). Moreover, human MRSA strains from patients with endocarditis and vascular device infections also tend to exhibit similar stable, low-level tPMP resistance in vitro (versus isolates from nonvascular infections) (2, 12, 42). Although the staphylocidal mechanisms of tPMPs involve target membrane permeabilization, defective autolysis impedes the ultimate extent of tPMP-induced staphylocidal effects (43). Further, exposure of tPMP-susceptible strains of S. aureus induces both a progressive increase in tPMP resistance and morphological changes in the cell wall of such strains very reminiscent of those observed with GISA strains (i.e., enhanced thickness) (45). Finally, we have recently confirmed an additional correlation among low-level tPMP resistance in vitro, loss of agr function, and persistent MRSA bacteremia (13). This finding suggested that S. aureus may use a common strategy to circumvent the actions of both antimicrobial peptides and glycopeptides. The results from the current investigation lend further support to this hypothesis. Both parental, laboratory-derived S. aureus strains (RN6607 and RN9120) and the initial clinical MRSA isolate (A5937) were (i) vancomycin susceptible, (ii) lysed by Triton and vancomycin, and (iii) tPMP susceptible. After vancomycin exposures in vitro or in vivo, their derivative strains demonstrated increases in vancomycin MICs and reductions in their in vitro susceptibilities to tPMP.

Importantly, in both the agrII knockout background strains, RN9120V and RN9120-GISA, and the clinical strain A5940 obtained from valvular tissue (in which an agrII-defective genotype evolved following prolonged vancomycin therapy) a hetero-GISA or GISA phenotype was documented by in vitro population analysis. However, only in strains RN9120V and RN9120-GISA were significant lysis defects and reduced susceptibility to low levels of tPMP associated with vancomycin exposure. In contrast, neither strain RN6607V nor clinical MRSA A5940 exhibited substantially decreased autolytic or vancomycin-lytic profiles despite modest increases in tPMP resistance after vancomycin exposure. These observations suggest that vancomycin exposure may induce specific phenotypic adaptations that are dependent, at least in part, on agr genotype and/or phenotype status. Thus, the loss of agr function seems to be necessary, but not sufficient, to induce the hetero-GISA or GISA phenotypes. After loss of agr function, full expression of the GISA phenotype appears to require serial exposures to subinhibitory vancomycin concentrations.

The development of low-level tPMP resistance in vitro roughly paralleled the evolution of the hetero-GISA or GISA phenotypes during or after vancomycin exposures. However, moderate tPMP resistance also developed in strain RN6607V, without development of the full GISA phenotype. Finally, only in the setting of an initially agrII-defective parental genotype and serial vancomycin exposures did all of the following three phenotypes concomitantly emerge: hetero-GISA or GISA, low-level tPMP resistance, and defective autolysis and vancomycin lysis. Since the relationship between GISA, hetero-GISA, and tPMP resistance appears to be complex, defining the tPMP susceptibilities in a larger collection of clinical GISA isolates would be of interest. Our prediction would be that many of these strains would exhibit reduced susceptibility to tPMP and an autolysis-deficient phenotype. Of interest, we recently studied 21 MRSA isolates from patients with persistent MRSA bacteremia (many of which demonstrated relative tPMP resistance) and found no correlation between the latter phenotype and GISA/hetero-GISA (13).

Collectively, our data suggest the following: (i) serial vancomycin exposure, particularly at subinhibitory concentrations, is associated with hetero-GISA or GISA phenotypes; (ii) neither the agrII-defective genotype nor the hetero-GISA/GISA phenotypes are independently associated with defects in autolysis or vancomycin lysis; (iii) increasing resistance to tPMP can be associated with both the hetero-GISA/GISA phenotypes, as well as defects in lysis; and (iv) the loss of agr function may prove advantageous for S. aureus survival in vivo, a finding consistent with previous investigations (13, 34, 44). It is worth emphasizing that the laboratory strains used in this investigation were MSSA. Thus, although the GISA phenotype strains isolated from clinical infections have been almost exclusively MRSA, our data confirm prior investigations that any S. aureus strain, given the appropriate agr genotype and phenotype and a threshold duration of vancomycin exposure, may be capable of developing the GISA phenotype (35).

Many questions remain unanswered, including questions about the role of the agr genotype in the emergence of the GISA phenotype during vancomycin exposures. Although we found a preponderance of agr group II in GISA from the United States, agr nongroup II strains clearly can also be readily passaged in vitro to a GISA phenotype (e.g., MRSA COL, agr group I [37]). Other topics of interest include (i) the precise physiologic and genetic linkages among defects in lysis, loss of agr function, and increasing resistance to host defense peptides; (ii) the biochemical mechanisms involved in the association between loss of agr function and defective lysis profiles; and (iii) the effect of the GISA phenotype and vancomycin exposures upon virulence (11, 21, 33). These and other key issues are now being investigated in ongoing studies in our laboratories.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants RO1-AI-39108 (A.S.B.), RO1-AI-48031 (M.R.Y.), RO1-AI-14372 (R.P.N.), and RO1-AI-59111 (V.G.F.) from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayer, A. S., R. Prasad, J. Chandra, A. Koul, M. Smriti, A. Varma, R. A. Skurray, N. Firth, M. H. Brown, S. P. Koo, and M. R. Yeaman. 2000. In vitro resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to thrombin-induced platelets microbicidal protein is associated with alterations in cytoplasmic membrane fluidity. Infect. Immun. 68:3548-3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayer, A. S., D. Cheng, M. R. Yeaman, G. Ralph Corey, R. S. McClelland, L. J. Harrel, and V. G. Fowler. 1998. In vitro resistance to thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal protein among clinical bacteremic isolates of Staphylococcus aureus correlates with an endovascular infectious source. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:3169-3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bischoff, M., J. M. Entenza, and P. Giachino. 2001. Influence of a functional sigB operon on the global regulators sar and agr in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 183:5171-5179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bischoff, M., and B. Berger-Bachi. 2001. Teicoplanin stress-selected mutations increasing σB activity in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1714-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle-Vavra, S., R. B. Carey, and R. S. Daum. 2001. Development of vancomycin and lysostaphin resistance in a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:617-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Staphylococcus aureus resistant to vancomycin—United States, 2002. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51:565-567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Climo, M. W., R. L. Patron, and G. L. Archer. 1999. Combinations of vancomycin and β-lactams are synergistic against staphylococci with reduced susceptibilities to vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1747-1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denny, A. E., L. R. Peterson, D. N. Gerding, and W. H. Hall. 1979. Serious staphylococcal infections with strains tolerant to bactericidal antibiotics. Arch. Intern. Med. 139:1026-1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhawan, V. K., A. S. Bayer, and M. R. Yeaman. 1998. In vitro resistance to thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal proteins associated with enhanced progression and hematogenous dissemination in experimental Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Infect. Immun. 66:3476-3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhawan, V. K., A. S. Bayer, and M. R. Yeaman. 1999. Influence of in vitro susceptibility phenotype against thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal protein on treatment and prophylaxis outcomes of experimental Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis J. Infect. Dis. 180:1561-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ena, J., R. W. Dick, R. N. Jones, and R. P. Wenzel. 1993. The epidemiology of intravenous vancomycin usage in a university hospital: a 10-year study. JAMA 269:598-602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler, V. G., L. M. McIntyre, M. R. Yeaman, G. E. Peterson, L. B. Reller, G. R. Corey, D. Wray, and A. S. Bayer. 2000. In vitro resistance to thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal protein in isolates of Staphylococcus aureus from endocarditis patients correlates with an intravascular device source. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1251-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowler, V. G., Jr., G. Sakoulas, L. M. McIntyre, V. G. Meka, R. D. Arbeit, C. H. Cabell, M. E. Stryjewski, G. M. Eliopoulos, L. B. Reller, G. R. Corey, T. Jones, N. Lucindo, M. R. Yeaman, and A. S. Bayer. 2004. Persistent bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection is associated with agr dysfunction and low-level in vitro resistance to thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal protein. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1140-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fridkin, S. K., J. Hageman, L. K. McDougal, J. Mohammed, W. R. Jarvis, T. M. Perl, and F. C. Tenover. 2003. Epidemiological and microbiological characterization of infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin, United States, 1997-2001. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:429-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujimoto, D. F., and K. W. Bayles. 1998. Opposing roles of the Staphylococcus aureus virulence regulators, agr and sar, in Triton X-100- and penicillin-induced autolysis. J. Bacteriol. 180:3724-3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geisel, R., F. J. Schmitz, A. C. Fluit, and H. Labischinski. 2001. Emergence, mechanism, and clinical implications of reduced glycopeptide susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:685-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graschopf, A., and U. Blasi. 1999. Molecular function of the dual-start motif in the lambda S holin. Mol. Microbiol. 33:560-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groicher, K. H., B. A. Firek, D. F. Fujimoto, and K. W. Bayles. 2000. The Staphylococcus aureus lrgAB operon modulates murein hydrolase activity and penicillin tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 182:1794-1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingavale, S. S., W. van Wamel, and A. L. Cheung. 2003. Characterization of Rat, an autolysis regulator in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1451-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarraud, S., C. Mougel, J. Thioulouse, G. Lina, H. Meugnier, F. Forey, X. Nesme, J. Etienne, and F. Vandenesch. 2002. Relationships between Staphylococcus aureus genetic background, virulence factors, agr groups (alleles), and human disease. Infect. Immun. 70:631-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarvis, W. R. 1998. Epidemiology, appropriateness, and cost of vancomycin use. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:1200-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji, G., R. Beavis, and R. P. Novick. 1997. Bacterial interference caused by autoinducing peptide variants. Science 276:2027-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koehl, J. L., A. Muthaiyan, R. K. Jayaswal, K. Ehlert, H. Labischinski, and B. J. Wilkinson. 2004. Cell wall composition and decreased autolytic activity and lysostaphin susceptibility of glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3749-3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korzeniowski, O., and M. A. Sande. 1982. Combination antimicrobial therapy for Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in patients addicted to parenteral rugs and in nonaddicts: a prospective study. Ann. Intern. Med. 97:496-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kupferwasser, L. I., M. R. Yeaman, S. M. Shapiro, C. C. Nast, and A. S. Bayer. 2002. In vitro susceptibility to thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal protein is associated with reduced disease progression and complication rates in experimental Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Circulation 105:746-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyon, G. J., P. Mayville, T. W. Muir, and Richard P. Novick. 2000. Rational design of a global inhibitor of the virulence response in Staphylococcus aureus, based in part on localization of the site of inhibition to the receptor-histidine kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:13330-13335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maslow, J., A. M. Slutsky, and R. D. Arbeit. 1993. The application of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to molecular epidemiology, p. 563-572. In D. H. Persing, T. F. Smith, F. C. Tenover, and J. White (ed.), Diagnostic molecular epidemiology: principles and applications. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 28.Mercier, R. C., M. J. Rybak, A. S. Bayer, and M. R. Yeaman. 2000. Influence of platelets and platelet microbicidal protein susceptibility on the fate of Staphylococcus aureus in an in vitro model of infective endocarditis. Infect. Immun. 68:4699-4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercier, R. C., R. M. Dietz, J. Mazzola, A. S. Bayer, and M. R. Yeaman. 2004. Beneficial effects of thrombin-stimulated platelets alone and in combination with vancomycin or nafcillin in an in vitro model of infective endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2551-2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naimi, T. S., K. H. LeDell, K. Como-Sabetti, S. M. Borchardt, D. J. Boxrud, J. Etienne, S. K. Johnson, F. Vandenesch, S. Fridkin, C. O'Boyle, R. N. Danila, and R. Lynfield. 2003. Comparison of community- and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. JAMA 290:2976-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility testing for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 32.Novick, R. P. 2000. Pathogenicity factors and their regulation, p. 392-407. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 33.Pallares, R., R. Dick, R. P. Wenzel, J. R. Adams, and M. D. Nettleman. 1993. Trends in antimicrobial utilization at a tertiary teaching hospital during a 15-year period (1978-1992). Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 14:376-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peacock, S. J., T. J. Foster, B. J. Cameron, and A. R. Berendt. 1999. Bacterial fibronectin-binding proteins and endothelial cell surface fibronectin mediate adherence of Staphylococcus aureus to resting human endothelial cells. Microbiol. 145:3477-3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfeltz, R. F., V. K. Singh, J. L. Schmidt, M. A. Batten, C. R. Baranyk, M. J. Nadakavukaren, R. K. Jayasway, and B. J. Wilkinson. 2000. Characterization of passage-selected vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains of diverse parental backgrounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:294-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakoulas, G., G. M. Eliopoulos, R. C. Moellering, Jr., C. Wennersten, L Venkataraman, R. P. Novick, and H. S. Gold. 2002. Accessory gene regulator (agr) locus in geographically diverse Staphylococcus aureus isolates with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1492-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakoulas, G., G. M. Eliopoulos, R. C. Moellering, Jr., R. P. Novick, L. Venkataraman, C. Wennersten, P. C. DeGirolami, M. J. Schwaber, and H. S. Gold. 2003. Staphylococcus aureus accessory gene regulator (agr) group II: is there a relationship to the development of intermediate-level glycopeptide resistance? J. Infect. Dis. 187:929-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakoulas, G., P. A. Moise-Broder. J. Schentag, A. Forrest, R. C. Moellering, Jr., and G. M. Eliopoulos. 2004. Relationship of MIC and bactericidal activity to efficacy of vancomycin for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2398-2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sieradzki, K., and A. Tomasz. 1998. Inhibition of cell wall turnover and autolysis by vancomycin in a highly vancomycin-resistant mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 179:2557-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh, V. K., J. L. Schmidt, R. K. Jayaswal, and B. J. Wilkinson. 2003. Impact of sigB mutation on Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin resistance varies with parental background and method of assessment. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 21:256-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tenover, F. C., J. W. Biddle, and M. V. Lancaster. 2001. Increased resistance to vancomycin and other glycopeptides in Staphylococcus aureus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:327-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu, T., M. R. Yeaman, and A. S. Bayer. 1994. In vitro resistance to platelet microbicidal protein correlates with endocarditis source among bacteremic staphylococcal and streptococcal isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:729-732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiong, Y.-Q., M. R. Yeaman, and A. S. Bayer. 1999. In vitro microbicidal activities of thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal protein-1 and human neutrophil defensin-1 on Staphylococcus aureus are substantially influenced by pretreatment with antibiotics differing in mechanisms of action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1111-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yarwood, J. M., J. K. McCormick, M. L. Paustian, V. Kapur, and P. M. Schlievert. 2002. Repression of the Staphylococcus aureus accessory gene regulator in serum and in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 184:1095-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeaman, M. R., A. S. Bayer, S. P. Koo, W. Foss, and P. M. Sullam. 1998. Platelet microbicidal proteins and neutrophil defensin disrupt the Staphylococcus aureus cytoplasmic membrane by distinct mechanisms of action. J. Clin. Investig. 101:178-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeaman, M. R., Y.-Q. Tang, A. J. Shen, A. S. Bayer, and M. E. Selsted. 1997. Purification and in vitro activities of rabbit platelet microbicidal proteins. Infect. Immun. 65:1023-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]