Abstract

Background

Dairy productivity can be improved by controlling metabolic diseases in dairy cows such as milk fever. The aim of this study was to estimate the cumulative incidence of milk fever during four years (2019 to 2022) at an anonymous dairy farm in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi. For this study, the records of the diagnosis of milk fever in 7540 parturient cows during four years was used.

Results

The monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever over four years was 2.2% (95% confidence interval, CI: 1.9, 2.3%). It was highest in 2021 (3.41 ± 0.41%) while it was lowest (0.87 ± 0.20%) in 2022. Based on multivariate binary logistic regression analysis, the odds of the monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever was 4.12 (95% CI: 2.31, 7.34) times higher in 2021 than in 2022. Similarly, it was 4.30 (95% CI: 2.38, 7.78) times higher in winter than in autumn. On the other hand, the monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever was 0.07 (95% CI: 0.03, 0.16) and 0.41 (95% CI: 0.06, 0.33) times lower in lactations 2 and 3 than in lactation 7, respectively. Lastly, milk fever was significantly associated with subclinical ketosis (χ2 = 54.74; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

The monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever could be considered as low while further strengthening preventive measures would benefit the farm.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12917-024-04455-4.

Keywords: Calcium cyclers, Cumulative incidence, Milk fever, Risk factor

Introduction

Milk fever or clinical hypocalcemia is a metabolic disorder caused by the presence of low concentration (less than 1.4 mmol/L serum) of calcium in the blood and commonly occurs around calving. In general, milk fever occurs within the first 24 h after calving, which is also called periparturient hypocalcemia or periparturient paresis, because an elevated body temperature is typically not observed. The disease occurs when calcium in the blood leaves to support milk production faster than calcium that can be returned to the blood from the diet, skeletal calcium stores, and renal calcium retention. Under normal physiological condition, serum calcium concentration of an adult cow is maintained above 2.0 mmol/L [1]. However, due to the production of colostrum at calving, the demand of calcium increases leading to a sudden drop in blood calcium concentration to less than 1.4 mmol/L of serum causing clinical hypocalcemia (milk fever) [2–4]. In addition to clinical hypocalcemia, a significant number of parturient cows develop subclinical hypocalcemia when the calcium concentration ranges from 1.4 to 2 mmol/L of serum; such cows have no clinical symptoms of hypocalcemia and are considered subclinical hypocalcemia [5].

Milk fever is an economically important disease because it causes a decrease in milk yield and increases the susceptibility of cows to various diseases and abnormalities such as mastitis, retained fetal membranes, displaced abomasum, dystocia and ketosis [6, 7]. In addition, cows with clinical hypocalcemia (or with subclinical hypocalcemia) fail to mount an adequate immune response to infections and are therefore prone to various infectious agents while failure treat clinical hypocalcemia cases causes death of cows [2].

According to the result of a study conducted on 1426 cows [7], the effect of hypocalcemia on milk yield depends on parity. The result of this study indicated that hypocalcemia had no effect on milk yield in primiparous cows. However, the same study showed that multiparous cows suffering from hypocalcemia produced 2.19 kg/d less milk in early lactation compared to multiparous cows with normal serum concentration. Similarly, other studies reported that cows with milk fever produced less milk than non-affected cows during the first 4–6 weeks of lactation [8].

Hypocalcemia reduces smooth muscle contraction causing reduced motility of rumen and abomasum leading to the displacement abomasum and reduced feed intake, and reduced muscle contraction preventing effective teat closure leading to mastitis [3]. In addition, hypocalcemic cows cannot stand up because calcium is necessary for nerve and muscle function and such cows could remain recumbent and subsequently be culled [9].

Therefore, milk fever is a disease of economic importance that affects dairy cows in different ways. It can reduce the productive life of a dairy cow by 3.4 years [10]. Furthermore, it causes severe economic losses that have been estimated at $334 per case per year [11]. This estimate of economic loss considers only the direct cost associated with the treatment of a clinical case and production loss incurred due to milk fever. In addition, as mentioned above, there are diseases and abnormalities that affect cows as a result of hypocalcemia negatively affecting the productivity of cows causing loss of milk production. For example, left-sided displacement of abomasum as the consequence of milk fever caused an estimated economic loss of $432.48 per cow in primiparous cows and $639.51 per cow in multiparous cows [12]. Therefore, dairy farms must adopt strategies for monitoring, treating and preventing hypocalcemia in their dairy cows.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) considers milk production one of the key factors for the country’s food security [13]. As the result, a good number of dairy farms have been established in the UAE during the last three decades. These farms play a significant role as sources of milk and other dairy products in the country. The herds of these farms have been established with a highly productive cows, which are prone to metabolic diseases such as milk fever. Thus, it can be hypothesized that milk fever could prevail in these dairy farms affecting the productivity of dairy cows. Therefore, it is timely to investigate the incidence of milk fever in the UAE so that scientific information is generated for future actions. This study was conducted to estimate the cumulative incidence of milk fever in a single dairy farm (herd size ≈ 3,800) in the UAE as a case study.

Materials and methods

Study design

The design of the study was retrospective longitudinal in which the data on the clinical diagnosis of milk fever in 7540 parturient cows were extracted and analyzed. Data were collected for four years (2019 to 2022) on daily basis longitudinally. Each parturient cow was examined for milk fever by the farm veterinarian, and cows with clinical signs of milk fever were classified positive for milk fever.

Setting of the study

The study was conducted on a dairy farm located outside of Al Ain city on Al Ain road. The cows were housed in purpose-built facilities with a cooling system that ensures the room temperature in the barn does not exceed 20ºC even if the outside temperature is high. The set-up of the investigated farm has been published previously [14]. The cows were milked four times a day for their comfort in a modern facility. The farm used the Dairy comp 305 Herd Management software and SAP ERP system. Feed was sourced globally depending on the quality, price, and availability. The dairy herd was fed on total mixed ration (TMR) four times a day while it routinely analyzed using near-infra-red (NIR) technology.

Study animals (participants)

The study was conducted on 7540 early parturient cows on one farm with a herd size of 3800 dairy cows over four years. Thus, all cows that calved between 2019 and 2022 were eligible for the study and were therefore included in the study. Most cows calved three times and thus tested three times. Data were collected from each of these 7540 cows at early parturition and then stored in soft copy format by the farm veterinarian. The research team extracted these data from the farm database and used them for this study after obtaining permission from the farm administration.

Prepartum management of study dry cows to prevent milk fever

The farm uses a combination of strategies to prevent the occurrence of milk fever. The main strategy was implementation of dietary cation-anion difference (DCAD) principle during the dry period. Thus, during prepartum dry cows were fed on rations with a negative DCAD. Additionally, the cows were injected with 1 L of 23% calcium gluconate solution subcutaneously immediately after parturition. On top of these, parturition cows were administered with one bolus of calcium orally on the second day of parturition.

For the treatment of milk fever, two protocols were followed by the farm depending on whether cow is in standing or recumbent position. Recumbent cases were administered with 500 mL of a 23% calcium gluconate solution intravenously, and then responding cows administered with two boli of calcium; the first bolus was given when the cow stands up and the second bolus 12 h after the first bolus. On the other hand, cows in standing position were administered only two boli of calcium orally; one immediately after calving and the second bolus 12 h after the first bolus.

Variables

The outcome variable was clinical hypocalcemia (milk fever). Season, year and number of lactations were considered as predictors. Milk fever was diagnosed based on clinical signs that include excitement, muscle tremor, head shaking, protrusion of the tongue, and teeth grinding. In advanced cases, sternal recumbency, depression of consciousness, lateral recumbency, decreased heart rate, and coma have been used to diagnose milk fever.

Data sources

The data source was the database of the study dairy farm. An electronic copy of the farm database was accessed and used for data extraction. The data on the milk fever were in 7540 cows over the four years (2019 to 2022) extracted and used for this study. All parturient cows were clinically examined for milk fever by a veterinarian during the first week of calving as part of the routine milk fever control program. Accordingly, cows were classified as positive or negative for milk fever based on presence or absence of clinical signs of milk fever. In addition to the diagnosis of milk fever, different variables such as number of lactations, season and year of diagnosis were collected for each cow.

In addition to the milk fever, data were collected on ketosis from the records each cow. Each parturient cow was tested for ketosis regularly after six days post parturition by the veterinarians of the farm. On the 6th after parturition blood samples were collected from the coccygeal veins for and the concentration of β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) was determined directly determined on-site using a handheld meter (PrecisionXceed, Abbott Diabetes Care Inc., Alameda, CA) that was previously validated for use in cows [6, 15]. The cows were classified based as negative when the BHB was less than 1.2mmol/L of blood, as having subclinical ketosis when the blood concentration of BHB was between 1.2 and 2.9mmol/L, as positive for clinical ketosis when the blood concentration of BHB was ≥ 3.0mmol/L [16, 17]. In addition, the cows were examined clinically for any clinical signs of ketosis such loss of appetite, rapid weight loss, licking inanimate objects, salivation, walking in circle, head pushing and related signs.

Sample size

A sample size calculation was not made. Data on the diagnosis of milk fever for all the cows that calved between 2019 and 2022 were used. Accordingly, 7540 cows calved between 2019 and 2022 were considered for data extraction. None of the parturient cows were excluded.

Qualitative variables

Most of the data in this study were qualitative data including the outcome variable. The outcome variable was either positive or negative. These qualitative variables were converted to quantitative values in the analysis. Similarly, independent variables such as season and year were also converted to numerical values for the purpose of data analysis.

Statistical analysis

Comparison of mean monthly cumulative incidence was performed using GraphPad Prism 8. Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis used to assess the association of mean monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever with potential risk factors was assessed using IBM SPSS version 28. The effect of confounding variables was controlled by multivariate logistic regression analysis. A P value < 0.05 or 95% confidence interval was used to define statistical significance.

Results

Characteristics of the study cows (study participants)

The data were collected from the records of 7540 fresh lactating cows during four years. One cow was examined four times because the average calving interval on the farm was about 12–13 months. The number of lactations of the tested cows ranged between 1 and 7. The majority (67.1%) of cows were at lactations 2 (n = 2819) and 3 (n = 2238). The number of examined cows decreased as the number of lactations increased. The number of lactating cows was only 141 in lactation 7, while in lactation 1 it was 2819. On the other hand, the number of lactating cows increased over the four years from 1707 in 2019 to 2066 in 2022. The average number of lactating cows per year it was 1885 during the study period. The average age at first calving (lactation 1) was 2 years. The highest lactation number was 7, and the average calving interval was 12 months. Thus, the age of examined cows was from 2 to 9 years, as observed from the records of each study cow. All tested cows were Holstein Friesian breed. Data extraction and their analysis according to the steps shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for data extraction and analysis for the estimation of the mean monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever at the study dairy farm

Cumulative incidence of milk fever on the studied dairy farm

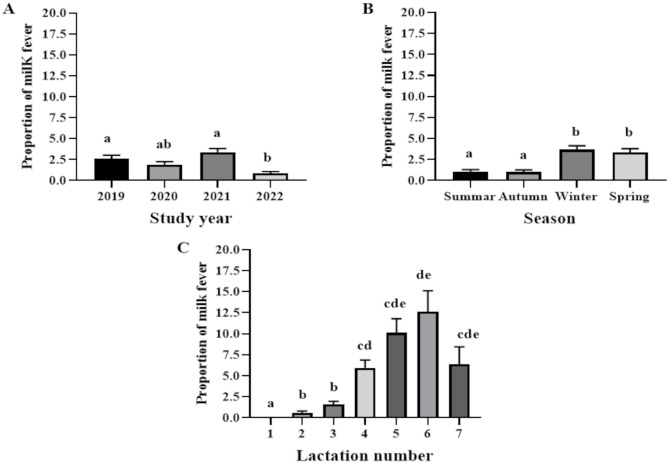

The four-year (2019 to 2022) monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever was 2.2% (95% confidence interval, CI: 1.9, 2.3%). Figure 2 shows the monthly cumulative incidences of milk fever in different years, seasons and lactation numbers. The mean ± SEM monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever was highest in 2021 [3.41 ± 0.41 (95% CI: 2.66, 4.30)] and it significantly different from those of the remaining years (Fig. 2A and Table 1). With regard to season, as presented in Fig. 2B, relatively higher monthly cumulative incidences were recorded in winter [3.67 ± 0.45 (95% CI: 2.83, 4.67)] and spring [3.36 ± 0.43 (95% CI: 2.57, 4.32)]. The monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever progressively increased from 0.0% in lactation 1 to 12.64 ± 2.46 in lactation 6 (Fig. 2C and Table 1) while it started to decrease in lactation 7.

Fig. 2.

The mean monthly cumulative incidence during different years, seasons and lactation numbers. Means with error bars labeled with different letters are significantly different while those with similar letters are not different

Table 1.

Association of the monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever with potential risk factors based on univariate logistic regression analysis

| Risk factors | Category | Total tested | No. positive | Mean (95% CI) | SEM* | Odd ratio (95% CI) | χ2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study year (n = 7540) | 2019 | 1707 | 45 | 2.64 (1.93, 3.51) | 0.39 | 3.08 (1.78, 5.34) | 32.86 | < 0.001 |

| 2020 | 1773 | 34 | 1.92 (1.33, 2.67) | 0.33 | 2.23 (1.25, 3.95) | |||

| 2021 | 1994 | 68 | 3.41 (2.66, 4.30) | 0.41 | 4.02 (2.38, 6.78) | |||

| 2022 | 2066 | 18 | 0.87 (0.52, 1.37) | 0.20 | 1 | |||

| Season (n = 7540) | Summer | 1944 | 21 | 1.08 (0.67, 1.65) | 0.23 | 1.04 (0.57, 1.91) | 53.32 | < 0.001 |

| Autumn | 2126 | 22 | 1.03 (0.65, 1.56) | 0.22 | 1 | |||

| Winter | 1716 | 63 | 3.67 (2.83, 4.67) | 0.45 | 3.65 (2.23, 5.95) | |||

| Spring | 1754 | 59 | 3.36 (2.57, 4.32) | 0.43 | 3.33 (2.03, 5.45) | |||

| Lactation stage (n = 7511) | Lactation 1 | 2819 | 0 | 0 (0, 0.13) | 0 | 0 | # | |

| Lactation 2 | 2238 | 14 | 0.63 (0.34, 1.05) | 0.17 | 0.09 (0.04, 0.22) | |||

| Lactation 3 | 1134 | 17 | 1.59 (0.88, 2.39) | 0.37 | 0.22 (0.1, 0.51) | |||

| Lactation 4 | 671 | 40 | 5.96 (4.29, 8.03) | 0.91 | 0.93 (0.44, 1.96) | |||

| Lactation 5 | 326 | 33 | 10.12 (7.07, 13.92) | 1.67 | 1.65 (0.77, 3.55) | |||

| Lactation 6 | 182 | 23 | 12.64 (8.18, 18.36) | 2.46 | 2.12 (0.95, 4.74) | |||

| Lactation 7 | 141 | 9 | 6.38 (2.96, 11.77) | 2.06 | 1 |

*Standard error of mean, # The SPSS could not calculate Fisher’s exact value

On the other hand, out of 165 positive cows during the four years, 13 were attacked twice, two three times, and one four times. Therefore, the cumulative incidence of calcium cyclers was 9.7% (16/165) in the study farm.

Association between the cumulative incidence of milk fever and potential predictors

Tables 1 and 2 show the association of year, season and number of lactations with the mean monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever based on univariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analysis. Based on univariate logistic regression analysis, the odds of monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever were 3.08 (95% CI: 1.78, 5.34), 2.23 (95% CI: 1.25, 3.95) and 4.02 (95% CI: 2.38, 6.78) times higher in 2019, 2020 and 2021 than in 2022, respectively (Table 1). Similarly, univariate logistic regression analysis indicated that the odds of monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever were 3.7 (95% CI: 2.23, 5.95) and 3.3 (95% CI: 2.03, 5.45) times higher in winter and spring, than in autumn, respectively. On the other hand, the odds of means monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever were 0.09 (95% CI: 0.04, 0.22) and 0.22 (95% CI: 0.1, 0.51) times less in lactations 2 and 3, than in lactation 7, respectively (Table 1).

Table 2.

Association of the monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever with potential risk factors based on multivariate logistic regression analysis

| Risk factors | Category | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Wald test | DF | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study year | 31.231 | 3 | < 0.00 | ||

| 2019 | 2.13 (1.17, 3.89) | 6.090 | 1 | 0.014 | |

| 2020 | 1.44 (0.76, 2.76) | 1.241 | 1 | 0.265 | |

| 2021 | 4.12 (2.31, 7.34) | 23.146 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| 2022 | 1 | - | - | - | |

| Season | - | - | 37.139 | 3 | < 0.001 |

| Summer | 1.35 (0.68, 2.71) | 0.731 | 1 | 0.393 | |

| Autumn | 1 | - | - | - | |

| Winter | 4.30 (2.38, 7.78) | 23.202 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| Spring | 3.87 (2.13, 7.05) | 19.676 | 1 | 0.979 | |

| Lactation stage | - | - | 129.579 | 6 | < 0.001 |

| Lactation 1 | 0 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.979 | |

| Lactation 2 | 0.07 (0.03, 0.16) | 37.032 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| Lactation 3 | 0.41 (0.06, 0.33) | 20.478 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| Lactation 4 | 0.63 (0.29, 1.37) | 1.341 | 1 | 0.247 | |

| Lactation 5 | 0.98 (0.44, 2.18) | 0.002 | 1 | 0.964 | |

| Lactation 6 | 1.72 (0.75,3.94) | 1.661 | 1 | 0.198 | |

| Lactation 7 | 1 | - | - | - |

Table 2 shows the association of monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever with potential risk factors on the based on multivariate binary logistic regression analysis. Based on multivariate binary logistic regression analysis, the odds of the mean monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever was 4.12 (95% CI: 2.31, 7.34) times higher in 2021 than in 2022 (Table 2). Similarly, the monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever was 4.30 (95% CI: 2.38, 7.78) times higher in winter than in autumn. On the other hand, the odds of the means monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever in lactations 2 and 3 were 0.07 (95% CI: 0.03, 0.16) and 0.41 (95% CI: 0.06, 0.33) times less than in lactation 7, respectively.

Association between milk fever and subclinical ketosis

Table 3 shows the association between subclinical ketosis and milk fever based on cross-tabulation. The association between milk fever and subclinical ketosis was statistically significant (χ2 = 54.74; p < 0.001). As can be seen from Table 3, 30.88% of the 136 milk fever positive cows were also positive for subclinical ketosis.

Table 3.

The association between the milk fever and subclinical ketosis in freshly calved cows at the study farm

| Milk fever status | Total | Chi-square | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |||||

| Sub-clinical ketosis status | Negative | 6579 | 94 | 6673 | 54.74 | < 0.001 |

| Positive | 796 | 42 | 838 | |||

| Total | 7375 | 136 | 7511 | |||

Discussion

Retrospective data of four years (2019 to 2022) were used to estimate the cumulative incidence of milk fever in 7540 lactating cows on the study dairy farm. The associations between the cumulative incidence of milk fever and potential risk factors were evaluated. The four-year cumulative incidence of milk fever reported by this study was 2.2% and was within the range (0.0–10.0%) of previously estimated incidence [4]. Studies in the USA have suggested that the incidence of milk fever is about 5% in lactating cows each year, while the incidence of subclinical hypocalcemia is about 50% in older cows during the periparturient period [18]. According to the result of an earlier meta-analysis on the incidence of milk fever, the average incidence of milk fever was 3.45%, 6.17% and 3.5% for North America, Europe and Australia, respectively [4]; each of the them is higher than the cumulative incidence of milk fever on the dairy farm studied. The lower cumulative incidence on the study farm could be due to the prepartum feeding strategy of dry cows. The dry cows were fed on rations with a negative DCAD. Besides, the cows were feed on rations with low in calcium to prevent milk fever. Moreover, the cows were injected with 1 L of calcium borogluconate subcutaneously immediately after delivery and administered with one bolus of calcium orally on the second day of parturition.

The cumulative incidence of milk fever was related to the lactation number of cows and increased from 0.0% in the first lactation to 13.0% in the sixth lactation. Similarly, results from a study conducted on 1462 cows in the USA indicated that the prevalence of subclinical hypocalcemia increased from 25 to 54% as the lactation number increased from lactation 1 to lactation 5 [18]. Furthermore, a study conducted on 1380 lactating cows in 115 German herds reported milk fever prevalence of 1.4%, 5.7% and 16.1% at the 2nd, 3rd, and ≥ 4th lactations, respectively [7]. These authors did not find any cases of milk fever in 1st lactation cows similar to the observation of this study. Furthermore, the prevalence of subclinical hypocalcemia was 5.7%, 29%, 49.4% and 60.4% in cows with 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and ≥ 4th lactations, respectively [7]. Similar observations were published by other authors [6, 19, 20]. The failure of cows to maintain normal serum calcium concentration is caused by maladaptation of cows to calcium metabolism in response to increased calcium demand [7].

Cow’s calcium requirements increase due to colostrum production during periparturient period which exposes multiparous lactating cows to milk fever unless they adapt to compensatory mechanisms [21]. The mechanisms used by cows to overcome milk fever during periparturient period include (1) decreased urinary calcium excretion, (2) increased intestinal calcium absorption, and (3) upregulating release of calcium from bone tissues. Therefore, the higher frequency of milk fever in multiparous cows could be associated with reduced ability of multiparous cows to mobilize calcium from bones as the result of decrease in the number of active osteoclasts and osteoblasts [7]. Similarly, although the prevalence of hypocalcemia is usually low in primiparous cows [19], study conducted in primiparous cows in 115 German herds reported a relatively higher prevalence (5.7%) [7].

In the present study, 31% and 67% of the milk fever cases occurred on days 1 and 2 in milk (DIM), respectively, and almost all (162 of 165) cases occurred on days 1 and 2 of parturition. Several other researchers have reported higher incidence of hypocalcemia during the first 48 of parturition [7, 19, 20]. Because compensatory mechanisms to overcome hypocalcemia require at least 48 h to start functioning, milk fever is very likely to occur during the first 48 h of parturition [1]. The concentration of calcium in the blood of adult cows should be maintained between 8.5 and 10 mg/L [3]. This concentration decreases by 25% and 50% respectively in heifers and adult cows within 12–24 h after parturition provided the cows are not well managed with effective milk fever control measures [3]. In order to maintain normal calcium homeostasis, cows should replace calcium lost in milk using the three calcium replacing mechanisms listed above. Dairy cows are expected to undergo a state of lactational osteoporosis to mobilize 9–13% of calcium from bone in one month of lactation to replace the calcium lost in milk [3].

Bone calcium mobilization and renal tubular reabsorption of calcium are regulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH), while intestinal absorption of dietary calcium is stimulated by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, a hormone that is made from vitamin D in the kidneys in response to increased PTH in the blood. However, there are different factors that affect calcium homeostasis and thus predispose cows to hypocalcemia by interfering with its mobilization from bone, absorption from the intestine, and reabsorption from the kidneys. Metabolic alkalosis, hypomagnesemia and dietary cation-anion difference (DCAD) are the most important factors that affect calcium homeostasis.

Metabolic alkalosis blocks the cow’s responses to PTH by altering its receptors making the tissues less sensitive to PTH [22–25]] thereby preventing effecient mobilization of calcium from the bone. Furthermore, failure of kidneys to respond to PTH reduces glomerular and tubular reabsorption of calcium and the conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, leading ineffective absorption of dietary calcium from the intestine [3]. In addition, hypomagnesemia negatively affects the metabolism of calcium by reducing PTH secretion in response to hypocalcemia [26] and by reducing tissue sensitivity PTH [27].

The economic loss due to milk fever was previously estimated by various researchers [3, 11, 12, 28] and it is directly related to the number of cases per year. In this study, the economic loss due to milk fever was expected to be relatively high in 2021, while it was expected to be in 2022 depending on the number of cases. It has been documented that the economic losses due to milk fever are significant and 60–70% of untreated cases of milk fever die, accounting for 8% of the total economic loss due to milk fever [29]. In addition, milk fever can lead to premature culling, treatment costs, and reduced milk production in later lactations, leading to economic loss [30]. In addition to its direct effects, milk fever also indirectly causes economic losses by increasing susceptibility to other diseases such as retained placenta, ketosis, displaced abomasum, endometritis, and mastitis [31]. A significant association was observed between subclinical ketosis and milk fever. Hypoglycemia is known to cause decreased muscle energy and muscle weakness without directly affecting blood calcium concentration. However, it is not clear whether subclinical ketosis predisposes cows to clinical hypocalcemia even though it affects blood calcium concentration. The observation of an association between subclinical ketosis and milk fever in lactating cows could also be a coincidence since fresh lactating cows are susceptible to both ketosis and milk fever due to the excretion of glucose and calcium into colostrum and milk.

The study has a limitation as it was conducted in a single farm. It was conducted as student’s senior project for a fulfillment of the degree of Bachler of Veterinary Medicine. It could not be expanded because of time limitation. Nevertheless, the layout and feeding system of dairy farms in the UAE have similarities, and hence the result of the study could serve as preliminary result for further studies on the milk fever in the UAE.

In conclusion, the monthly cumulative incidence of milk fever was relatively low in studied dairy farm compared to the cumulative incidences documented in the literature. It is recommended to implement control and preventive measures in order to reduce the incidence of milk fever.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the management and owners of the study dairy farm for allowing for providing them all-rounded support during the study including access to dairy records for data extraction.

Author contributions

S.A.A. and B.B. analyzed the data and interpreted the analysis. A.Z., A.A. and T.M. entered and edited the data. B.A.D. reviewed the manuscript. G.A. conceptualized and lead the study and drafted manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by the United Arab Emirates University through its SURE PLUS Program. The grant reference number was SURE Plus G00003868.

Data availability

Data are provided within the manuscript as a supplementary file.

Declarations

Animal ethics and consent to participate declarations

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from administration of the farm.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Martín-Tereso J, Martens H. Calcium and magnesium physiology and nutrition in relation to the prevention of milk fever and tetany (dietary management of macrominerals in preventing disease). Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2014;30:643–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimura K, Reinhardt TA, Goff JP. Parturition and hypocalcemia blunts calcium signals in immune cells of dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 2006;89:2588–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goff JP. The monitoring, prevention, and treatment of milk fever and subclinical hypocalcemia in dairy cows. Vet J. 2008;176:50–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeGaris PJ, Lean IJ. Milk fever in dairy cows: a review of pathophysiology and control principles. Vet J. 2008;176:58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilhelm AL, Maquivar MG, Bas S, Brick TA, Weiss WP, Bothe H, et al. Effect of serum calcium status at calving on survival, health, and performance of postpartum holstein cows and calves under certified organic management. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100:3059–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinhardt TA, Lippolis JD, McCluskey BJ, Goff JP, Horst RL. Prevalence of subclinical hypocalcemia in dairy herds. Vet J. 2011;188:122–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venjakob PL, Borchardt S, Heuwieser W. Hypocalcemia—cow-level prevalence and preventive strategies in German dairy herds. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100:9258–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajala-Schultz PJ, Gröhn YT, McCulloch CE, Guard CL. Effects of clinical mastitis on milk yield in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 1999;82:1213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevenson JS, Call EP. Reproductive disorders in the periparturient dairy cow. J Dairy Sci. 1988;71:2572–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Payne JM. Outlok on milk fever. Outlook Agric Outlook Agric. 1968;5:266–72. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guard C. fresh cow problems are costly: culling hurts the most - Page 100 in Proc. 1994 Annu. Conf. Vet., Cornell Univ., Ithaca, NY. 1996.

- 12.Liang D, Arnold LM, Stowe CJ, Harmon RJ, Bewley JM. Estimating US dairy clinical disease costs with a stochastic simulation model. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100:1472–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UAE. National Food Security. Strategy 2051 - The United Arab Emirates Government’s second Annual Meetings. November 2018. Accessed 27 Jul 2023.

- 14.Ameni G, Bayissa B, Zewude A, Degefa BA, Mohteshamuddin K, Kalaiah G et al. Retrospective study on bovine clinical mastitis and associated milk loss during the month of its peak occurrence at the National Dairy Farm in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Pineda A, Cardoso FC. Technical note: validation of a handheld meter for measuring β-hydroxybutyrate concentrations in plasma and serum from dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2015;98:8818–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oetzel GR. Monitoring and testing dairy herds for metabolic disease. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2004;20:651–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McArt JAA, Nydam DV, Oetzel GR, Overton TR, Ospina PA. Elevated non-esterified fatty acids and β-hydroxybutyrate and their association with transition dairy cow performance. Vet J. 2013;198:560–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horst R, Jesse G, Brain M. Prevalence of subclinical hypocalcemia in U.S. dairy Operations. Agri Res Service. 2003.

- 19.Miltenburg CL. September. Management of Peripartum Dairy Cows for Metabolic Health and Immune Function. Doctoral Theses: Guelph, Ontario, Canada 2015; 2015.

- 20.Gild C, Alpert N, Straten MV. The Inf luence of Subclinical Hypocalcemia on Production and Reproduction parameters in Israeli dairy herds. Isr J Vet Med. 2015;70.

- 21.Klingbeil M. Investigation of influence factors on yield, quality and calcium content of first colostrum in Holstein. Doctoral thesis. Ruminant and Swine Clinic, Faculty of Veterinary Medicin, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany. 2015. Accessed 28 Jul 2023.

- 22.Gaynor PJ, Mueller FJ, Miller JK, Ramsey N, Goff JP, Horst RL. Parturient hypocalcemia in jersey cows fed alfalfa haylage-based diets with different cation to anion ratios. J Dairy Sci. 1989;72:2525–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leclerc H, Block E. Effects of reducing Dietary Cation-Anion Balance for Prepartum dairy cows with specific reference to Hypocalcemic Parturient Paresis. Can J Anim Sci. 1989;69:411–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goff JP, Horst RL, Mueller FJ, Miller JK, Kiess GA, Dowlen HH. Addition of chloride to a prepartal diet high in cations increases 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D response to hypocalcemia preventing milk fever. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:3863–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillippo M, Reid GW, Nevison IM. Parturient hypocalcaemia in dairy cows: effects of dietary acidity on plasma minerals and calciotrophic hormones. Res Vet Sci. 1994;56:303–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Littledike ET, Horst RL. Vitamin D3 toxicity in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 1982;65:749–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rude RK. Magnesium deficiency: a cause of heterogeneous disease in humans. J Bone Min Res. 1998;13:749–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kossaibati MA, Esslemont RJ. The costs of production diseases in dairy herds in England. Vet J. 1997;154:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNeill DM, Roche JR, Stockdale CR, McLachlan BP. Nutritional strategies for the prevention of hypocalcaemia at calving for dairy cows in pasture-based systems. Aust J Agric Res. 2002;53:755–70. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan A, Muhammad Hassan M, Khan A, Chaudhry M, Hussain A. Descriptive epidemiology and Seasonal Variation in prevalence of milk fever in KPK (Pakistan). GV. 2015;14:472–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oetzel GR, Miller BE. Effect of oral calcium bolus supplementation on early-lactation health and milk yield in commercial dairy herds. J Dairy Sci. 2012;95:7051–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are provided within the manuscript as a supplementary file.