Abstract

Purpose

Antiangiogenesis therapy has become a hot field in cancer research. Given that tumor blood vessels often express specific markers related to angiogenesis, the study of these heterogeneous molecules in different tumor vessels holds promise for advancing anti-angiogenic therapy. Previously using phage display technology, we identified a targeting peptide named GX1 homing to gastric cancer vessels for the first time. However, GX1 also showed some non-specific binding with normal gastric vessels, which can lead to toxic side effects on normal endothelial cells. Therefore, we urgently need to adopt new screening strategies to avoid non-specific binding to normal vessels and obtain gastric cancer vascular targeting peptides with higher specificity.

Methods

In this study, we designed a new strategy which combined “positive screening” in vivo and “negative screening” in vitro for the first time. An in vivo positive screening was conducted using tumor bearing nude mice to identify peptides that were specifically enriched within the vasculature of gastric cancer. Concurrently, an in vitro negative screening process was conducted on normal vasculature endothelial cells, including human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs), to eliminate peptides binding to normal vasculature. After four rounds of iterative screening, a targeting peptide specifically targeting gastric cancer vasculature was obtained. In addition, an in vitro co-culture model by culturing HUVEC in tumor conditioned medium (Co-HUVEC) was established to investigate the affinity of these peptides. The targeting peptide was labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) for competitive and inhibitory assays.

Results

Blood vessel density analysis confirmed redundant capillary vessels in the xenografts, indicating that the mouse model was suitable for positive screening. Following four rounds of panning, a significant enrichment for phages specifically binding to gastric cancer vasculature was observed, with minimal binding to normal endothelial cells. The peptide CNTGSPYEC exhibited the highest reproducibility. In vitro immunofluorescence staining confirmed that the peptide CNTGSPYEC could specifically enrich in Co-HUVECs while showing no binding to normal vascular endothelial cells. In vivo immunofluorescence staining revealed that the peptide CNTGSPYEC could only bind to vascular endothelial cells specifically in gastric cancer but show no non-specific binding with normal tissue. Competitive and inhibitory assay also verified the targeting characteristics of the peptide with the fluorescence intensity of 17.13. As the concentration increases, the competitive inhibition rate can be incrementally raised to 93% (p < 0.05). Endothelial tube formation assay indicated that the peptide could suppress neovascularization, with the microvessel count reducing by 40% (p < 0.05). Furthermore, Cell Counting Kit-8 assay (CCK8) showed that the targeting peptide could partly inhibit cell proliferation of Co-HUVEC (61.7%).

Conclusion

Our novel strategy of the combined in vitro and in vivo screening outperforms previous methods that relied solely on negative/positive screening. In vivo and in vitro test confirmed the high targeting characteristic of the new peptide. Therefore, the peptide CNTGSPYEC may be a potential candidate in diagnosis and anti-angiogenesis therapy of gastric cancer. Our further exploration employs it as a vehicle for mediating drug accumulation in gastric cancer tissue.

Keywords: Tumor vasculature targeting peptides, Gastric cancer, Vascular endothelial cell, Anti-angiogenesis therapy

Introduction

Angiogenesis and vasculature are critical for tumor growth, progression and metastasis [1]. The key to vascular-targeted therapy is to identify specific molecules within tumor vascular endothelial cells and use them as targeting agents to combat cancer, while sparing the normal vasculature from potential toxic side effects.

Although numerous studies have delved into the unique characteristics of tumor vessels compared to normal vessels [2–7], the identification of specific molecules within gastric cancer vascular endothelial cells remains a challenge. This is primarily due to the difficulties in isolating and culturing gastric cancer endothelial cells, as well as the low-level expression of tumor vascular heterogeneity molecules, which makes them challenging to detect, isolate, and purify using standard techniques [8, 9]. Recently, several technologies are available for the screening of vascular target molecules, among which the random phage display peptide library technology stands out. This technology integrates the binding activity of target molecules with the ease of phage amplification, resulting in an efficient, cost-effective, and highly feasible screening method [10–12].

In our prior research, we utilized phage display technology to identify a targeting peptide, GX1, that can specifically bind to gastric cancer vessels [13–15]. However, the efficacy in tumor targeting of GX1 is insufficient, and it also showed some non-specific binding to normal gastric vessels. Consequently, the current study was designed to improve the screening strategy.

Specifically, we established an in vivo model for positive screening and two in vitro cell line models for negative screening for the first time. Through an in vivo positive screening approach in tumor-bearing nude mice, we aim to obtain a specific binding peptide that accumulates within gastric cancer vasculature. Simultaneously, we will conduct an in vitro negative depletion screening on normal endothelial cells to eliminate peptides that bind to normal blood vessels. After four rounds of rigorous selection, we aim to achieve a targeting peptide that specifically targets gastric cancer vasculature. This study will provide potential drugs for gastric cancer vascular targeted therapy. So as to improve the prognosis of gastric cancer.

Method

Cell culture and establishment of tumor-endothelial cell co-culture model

Human gastric carcinoma cells (MKN45), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs) were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank (Shanghai, China) and cultured in M200 basal medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), low serum growth supplement (Cascade Biologics, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 10 mg/mL streptomycin. The cells were maintained in a CO2 incubator (Forma Scientific). Co-HUVECs were prepared using the method established Jaffe et al. [16]. The MKN45 and HUVEC cells were co-cultured in transwell plates with a pore diameter of 0.4 μm. Briefly, two cells were separated by semi-permeable membranes of transwell plate, where the upper and lower chambers were interlinked and thus HUVEC and MKN45 cells could interact with each other by secreted soluble factors, which simulates the tumor microenvironment.

Immunosuppressed mice model with human tumor xenograft by subrenal capsule assay (SRCA)

Nude mice (4–6 weeks old, 16–20 g) were purchased from Zhuhai BesTest Bio-Tech Co., Ltd. (Guangdong, China). All animals were maintained within specific pathogen-free facilities at the Laboratory Animal Center of Nanfang Hospital. All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanfang Hospital (permit and approval number: 202105A028) and performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines of Nanfang Hospital.

Following the SRC method described by Bogden et al. [17], four-week-old female nude mice with an average weight of approximately 16 g were selected. The mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection, and under aseptic conditions, the kidney was isolated, the renal capsule was separated. Fresh gastric adenocarcinoma specimens resected surgically were washed several times with serum-free RPMI1640 (Gibco) culture medium to remove connective tissue and necrotic tissue. The tissue was then cut into 1 mm3 pieces and implanted into the subcapsular space of the mouse kidney. Seven days later, the transplanted tumors from the nude mice were dissected, fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde, routinely embedded in paraffin, and then sectioned and stained with HE. The tumor tissue was observed under a microscope to assess the angiogenesis.

Phage displayed peptide library and bacterial strain

The Ph.D.-C7C Phage Display Peptide Library Kit (New England Biolabs, Beverly, USA) was employed to screen for specific peptides that bind to the tumor vasculature in a nude mouse subcapsular human gastric cancer xenograft model. The phage display library contains random cyclic heptapeptides constrained at the N terminus of the minor coat protein (cpIII) of M13 phage. The library has a high titer of 2 × 1013 plaque-forming units (pfu) and a complexity of 1.2 × 109 individual clones. This represents the complete range of possible cyclic 9-mer peptide sequences, with a structural constraint imposed by a disulfide bond between two cysteine residues flanking the variable region. This constraint allows for a wide range of sequences with no obvious positional biases, as revealed by extensive sequencing of the naive library. Escherichia coli host strain ER2738 (A robust F+ strain with a rapid growth rate, New England Biolabs) was used for M13 phage propagation.

In vivo positive screening of phage peptide library with tumor bearing nude mice model

In vivo phage selection was performed as described with modifications [20]. Briefly, 5 mice were firstly anesthetized deeply using 70 mg/kg body weight of sodium phenobarbital and then injected intravenously (via tail vein) with 200 μl (1011 pfu) of the phage displayed peptide. After 6 min, the heart of the nude mouse was exposed, and puncture the left ventricle with a venous needle to inject preheated 50 mL RPMI1640 (Gibco), while cutting a small opening at the right auricle. The xenograft tumor and the control organs were removed and weighed. The cell pellet was eluted with 4 mL of 0.2 M Glycine–HCl (pH 2.2) for 10 min at 4 °C and then neutralized with 0.6 mL of 1 M Tris–HCl (pH 9.1), which represents the first round of eluted phages. Those eluted phages were set aside for in vitro screening purposes.

In vitro negative screening of phage peptide library with HUVECs and HMVECs

In vitro selection procedure was carried out according to the methods described by Ridgway et al. [18] and Poul et al. [19]. HUVEC (1 × 107) and HMVEC (1 × 107) were harvested using 2.5 mM EDTA solution. The HUVEC cells and phages of approximately 2 × 1011 pfu were blocked with 500 μL blocking buffer (BF), containing 5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma), and 0.1 M NaHCO3 for 30 min at room temperature. This step was repeated for subsequent cell blocking steps. The blocked phages were added to the blocked HUVEC cells and incubated gently for 1.5 h at 4 °C. The cells were then pelleted by centrifugation at 800 rpm for 5 min. The phages bound to the HUVEC cells were removed by centrifugation, and the resulting phage-containing supernatant was incubated with blocked HMVEC cells for another 1.5 h at 4 °C. Centrifuge the HMVEC and phage mixture at 800 rpm for 5 min to collect the supernatant with unbound HMVEC phages. For each (except for the last) round of in vitro selection, the unbound phages were infected with E. coli host strain ER2738, and propagated individually in 40 mL of LB medium containing 1 μg/mL tetracycline for 4–6 h at 37 °C. Cultures were then pooled and centrifuged. The amplified phage particles were purified using PEG-8000 (polyethylene glycol); 2 × 1011 pfu of the purified phages particles diluted in 200 μL of PBS were reinjected into tumor xenograft mice for another round of selection. Four rounds of positive and negative selection were performed as above. The final round of phages obtained without undergoing amplification are directly used to infect the host bacterium E. coli ER2738.

Sequence analysis of the selected phages and peptide synthesis

After the fourth round of panning, 20 phage clones were picked up randomly and their ssDNA were automatically sequenced with ABI Prism kit (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems, USA) by using sequencing primer ((-96 gIII,5´-HOCCC TCA TAG TTA GCG TAA CG-3´, provided in C7C kit, New England Biolabs.). BLAST (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/) and ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/) programs were using to determine the groups of related peptides [18]. Several selected phages were synthesized by GL Bio-chem (Shanghai) Ltd. Their sequence and structure were characterized by mass spectrometry, and their purity was confirmed to be 95% by analytical HPLC. A control peptide (CNKSPSGNC) was synthesized by phages randomly selected from the original phage peptide library, which were eliminated in the screening process without gastric cancer vascular targeting.

In vitro endothelial tube formation assay

Co-HUVEC cells were seeded at 2 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates, pre-coated with matrigel (BD Biosciences, New Jersey, USA), and treated with targeting peptide CNTGSPYEC and control peptide. After 24 h, tube formation was visualized using an inverted microscope.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

The cells coverslips and tissue sections were incubated with normal goat serum for 30 min. The slides were washed in PBS (pH = 7.2) thrice for 5 min each. The synthetic peptides labeled with Sulfo-Cyanine3 (Cy3) (red; Ex = 555 nm, Em = 570 nm) were incubated with cells coverslips and tissue sections overnight at 4°C [19]. Co-localization of the selected peptides with endothelial marker CD31 was performed to identify the binding ability of the peptides as described previously [20]. The cells coverslips and tissue sections were stained with anti-CD31 antibody followed by FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (green; Ex = 494 nm, Em = 520 nm). After washing three times with PBS (pH = 7.2), the cells coverslips and tissue sections were mounted with medium containing 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue; Ex = 364 nm, Em = 454 nm) and observed in the fluorescence microscope (Nikon EZ-C1, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Competitive and inhibitory assay

The cells in the different groups (HUVECS and Co-HUVECs) were cultured on coverslips and then fixed with PFA at 4 °C for 30 min. Different concentration unlabeled peptide (0, 50, 100, 150 and 200 μg/mL) diluted in PBS (pH = 7.2) were added onto the slips and incubated at 4 °C overnight. After being washed three times with PBS (pH = 7.2), the synthetic peptides labeled with Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC) were incubated with Co-HUVECs or HUVECs for 15 min. control peptides labeled with FITC were used as negative controls. Staining of nuclei was performed with DAPI and sections were mounted with nail polish. Fluorescent signals were detected using a confocal fluorescence microscope (Nikon EZ-C1, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Assay was used to analyze cell proliferation. In brief, 5 × 103 HUVECs and Co-HUVECs in each hole of the 96-well plate. After 8 h, control peptide or targeting peptide were added at the final concentration of 0, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100 μM, respectively. After treatment for 24 h, 10 μL CCK8 solution was added to each well. After incubation for 2 h, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Infinite M Nano, TECAN).

Statistics analysis

Immunofluorescence stain and Competitive and inhibitory assay were repeated more than three times. The staining intensity was evaluated by giving a mark according to the grade standard from our laboratory. All data were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Unpaired two-tailed t-test or one-way analysis of variances (ANOVA) was applied for statistical analysis by SPSS 29.0. A P value below 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

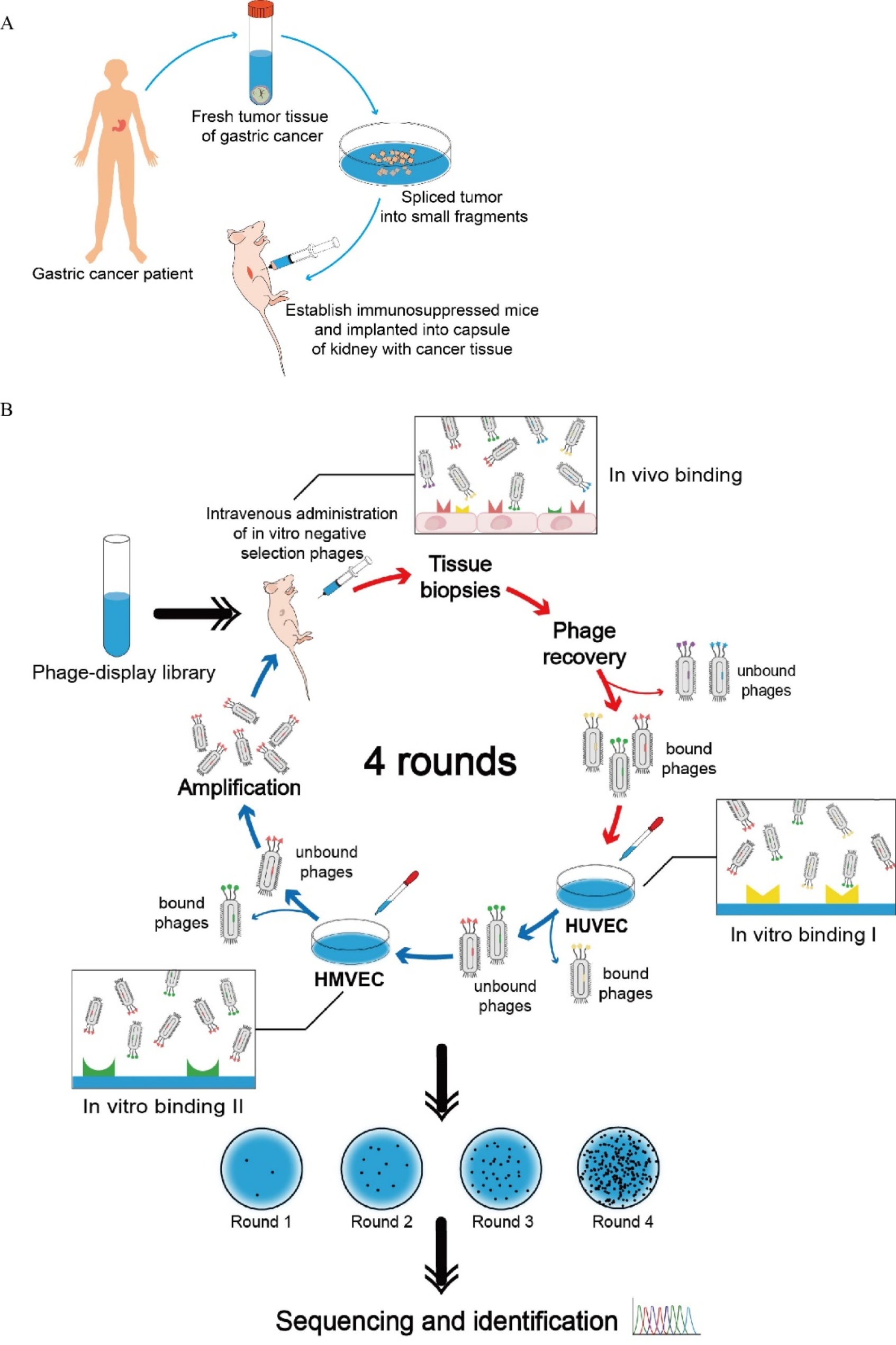

Combination of in vivo positive screening and in vitro negative screening

To identify gastric cancer vasculature-targeting peptides with higher specificity, we refined our screening strategy. The novel strategy of screening combined in vivo positive screening and in vitro negative screening for 4 rounds selection. In the procedure of positive screening, we used immunosuppressed mice model with human gastric cancer xenograft established by SRCA (Fig. 1A). Then the phages that specifically bind to gastric tumor vasculature were obtained for negative depletion screening. In the procedure of negative screening, C7C-phage displayed peptide library was applied successively on the HUVECs and the HMVECs (Fig. 1B). As a result, the phages that could bind to normal vasculature were removed. The unbound phages clones were proceeded to the following positive screening, rescued and amplified in E. coli ER2738 for the following round of screening.

Fig. 1.

Screening of targeting peptides from phage-display library

After four rounds of positive screening and negative screening, the number of phages recovered from was increased gradually. Finally, 20 phage clones selectively targeting to vasculature of gastric cancer without non-specific binding to normal gastric vascular endothelial cells were selected by the new screening strategy for sequencing. And the peptide CNTGSPYEC with the highest reproducibility was selected for subsequent verification.

(A) Technique of establishing immunosuppressed mice model with human gastric tumor xenograft by SRCA. (B) Workflow of phage-display-based screening in vivo and in vitro. Red arrows indicate the process of in vivo positive screening, while blue arrows indicate the process of in vitro negative screening. After 4 rounds of screening, target-bound phages were enriched and isolated.

In vitro binding ability of peptide to Co-HUVECs

To investigate specific molecules in gastric cancer vasculature endothelial cells, we commonly employ a co-culture method. As shown in Fig. 2A, the gastric cancer vasculature endothelial cells, compared with the normal endothelial cells, exhibited robust growth, forming vortex-like structures in certain areas.

Fig. 2.

Specific binding ability of peptide CNTGSPYEC to Co-HUVECs (Original magnification: 400×. Scale bar: 50 μm). PBS, Cy3-labeled control peptide and Cy3-labeled targeting peptide CNTGSPYEC were incubated with HUVECs and Co-HUVECs. Blue staining presented the location of the cell nucleus. Green staining showed CD31 expression, while red staining presented Cy3-labled peptide probe binding. (A) Morphology of HUVECs and Co-HUVECs under the light microscope. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of Co-HUVECs. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis of HUVECs

In vitro immunofluorescence analysis revealed that all cells were stained green with CD31, which is a biomarker for endothelial cells. Also, all cells were stained blue, which is indicative of nuclear localization. In the group of Co-HUVECs, the peptide CNTGSPYEC binding to Co-HUVECs was positively stained red, which was co-localized with CD31 at the surfaces and in the perinuclear cytoplasm of cells. In contrast, negative results were also obtained on Co-HUVECs if staining with control peptide or PBS instead of the targeting peptide CNTGSPYEC (Fig. 2B). In the case of the HUVECs group, the observed situation is distinct. Regardless of whether control peptide or targeting peptide CNTGSPYEC were used for staining, no light red positive staining was observed on the control HUVECs (Fig. 2C). These results showed that targeting peptide could only bind to gastric cancer endothelial cells but couldn’t have non-specific binding with normal vascular endothelial cells.

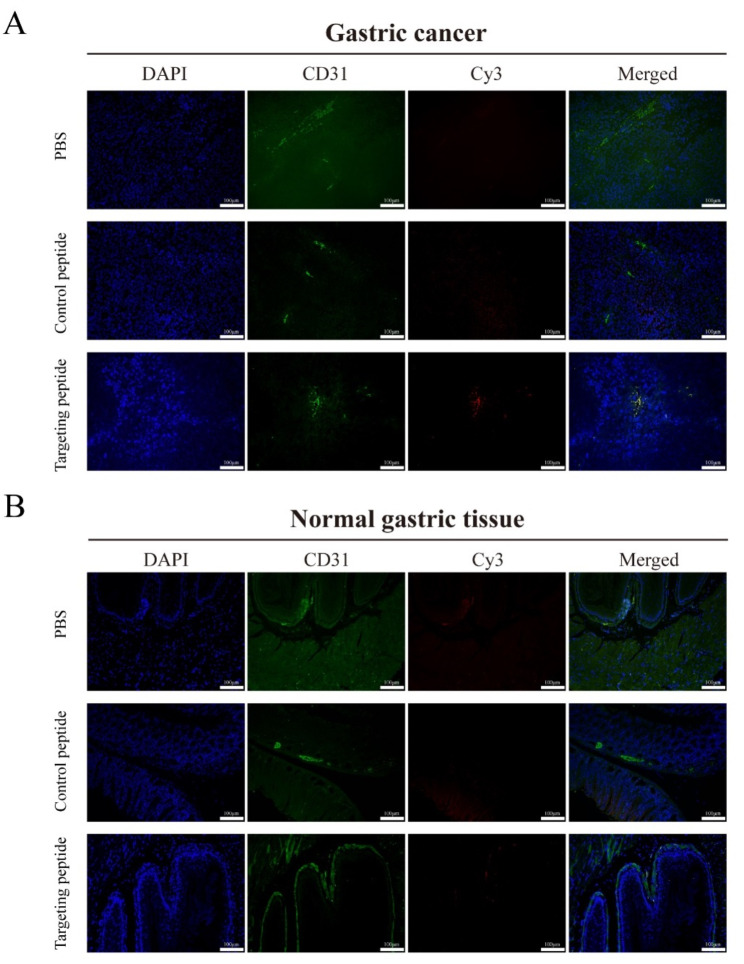

In vivo binding ability of peptide to gastric cancer vasculature

To directly observe the binding affinity, specificity and binding site of the peptide on normal gastric tissue and gastric cancer, in vivo immunofluorescence analysis was performed. As a positive control, CD31 (in green), a biomarker for endothelial cells, can be displayed in vasculature of normal gastric tissue and gastric cancer and DAPI (in blue) can be exhibited at the cellular nuclear location. Meanwhile, Cy3-labeled targeting peptide (in red) was found to be stained only in the gastric cancer vasculature, which was co-localized with CD31, indicating that the peptide targeted to the vasculature of gastric cancer. In contrast, Cy3-labeled control peptide staining could not be seen in vasculature of gastric cancer (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Binding ability of peptide CNTGSPYEC to vascular endothelial cells in normal gastric tissue and gastric cancer (Original magnification: 200×. Scale bar: 100 μm). PBS, Cy3-labeled control peptide and Cy3-labeled targeting peptide CNTGSPYEC were incubated with normal gastric tissue and gastric cancer respectively. Blue is DAPI staining. Green staining showed CD31 expression, while red staining presented Cy3-labled peptide probe binding. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of gastric cancer. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of normal gastric tissue

However, in the normal gastric tissue, neither Cy3-labeled targeting peptide nor Cy3-labeled control peptide staining was observed. No similar co-localized phenomenon was observed in these merged images. The results indicated that the targeting peptide selectively accumulated in gastric cancer vasculature.

The results of the competitive and inhibitory assay

Competitive and inhibitory assay was carried to further validate the specific binding of targeting peptide to Co-HUVECs. Compared with the FITC-labeled control peptide, the FITC-labeled targeting peptide showed significantly higher fluorescence intensity at the initial concentration in binding to the vascular endothelial of gastric cancer. The binding of the FITC-labeled targeting peptide CNTGSPYEC to the Co-HUVECs was inhibited by free targeting peptide (Fig. 4A). The fluorescence intensity of the FITC-labeled targeting peptide exhibited a gradually decreasing trend ranging from 17.13 to 1.2, as the concentration of the free targeting peptide increases from 0 μg/mL to 200 μg/mL (Fig. 4B). When the unlabeled free peptide CNTGSPYEC concentration reached more than 100 μg/mL, significant inhibition occurred. The competitive inhibition rate incrementally raised to 93% (Fig. 4C). However, the fluorescence intensity of the FITC-labeled control peptide does not decrease regardless of the concentration of the free control peptide added.

Fig. 4.

The competitive and inhibitory results on Co-HUVECs. (A) Different concentrations of the free targeting peptide CNTGSPYEC were pre-incubated with Co-HUVECs to competitively inhibit the binding of FITC-labeled targeting peptide (in green) to the cells (Original magnification: 400×. Scale bar: 50 μm). (B) The fluorescence intensity of FITC-labeled targeting peptide in the cells decreased from 17.13 to 1.2 with increasing concentrations of FITC-unlabeled free peptide CNTGSPYEC. (C) Comparable data were obtained in three independent experiments, and the average inhibition rates at different peptide concentration were shown. All experiments were performed with n = 5 per group, and data are presented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. (the targeting peptide group was compared with the control peptide group; the targeting peptide group was compared with 0 μg/mL group treated with targeting peptide)

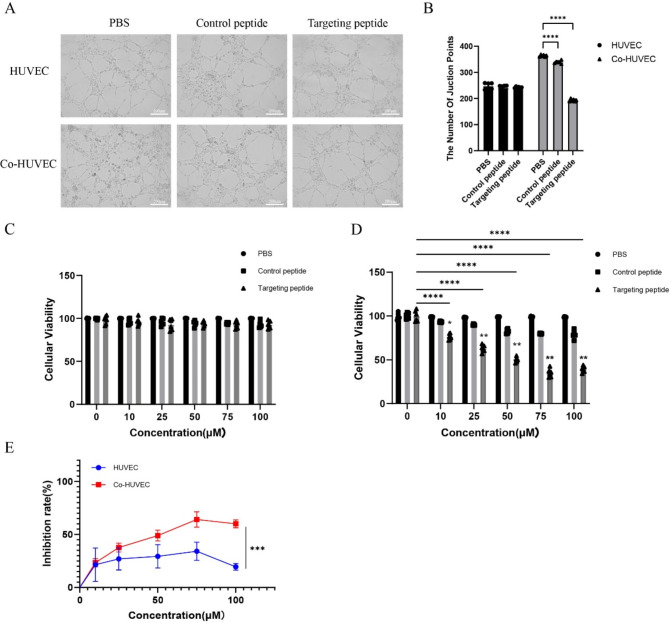

In vitro anti-angiogenesis effects of the targeting peptide

Endothelial tube formation assay demonstrated that both HUVECs and Co-HUVECs without treatment started to aggregate, turned fascicular and formed obvious and long tubular structures on matrigel substrates. The addition of both control peptide and targeting peptide did not significantly impacted the tube formation of HUVECs. However, in the gastric cancer vascular endothelial cell group, the control peptide showed little anti-angiogenesis effect, where cells formed disconnected tube analogs but they had the trends to be connected. In contrast, the treated groups containing the targeting peptide showed obvious anti-angiogenesis effect, where little formation of cellular network was in sight (Fig. 5A, B). The targeting peptide could suppress microtubule formation with the microvessel count reducing by 40%. This suggests that the targeting peptide possesses the ability to inhibit the formation of blood vessels in gastric cancer.

Fig. 5.

In vitro anti-angiogenesis evaluation of the targeting peptide. (A) Representative images of HUVEC and Co-HUVEC tube formation after incubation with the control peptide and the targeting peptide CNTGSPYEC for 24 h (Original magnification: 100×. Scale bar: 200 μm). (B) Number of microvessels. Compared with the PBS group of Co-HUVEC: ****p < 0.0001. Cell viability of (C) HUVEC (n = 6) and (D) Co-HUVEC (n = 6). Compared with 0 μM group treated with the same treatment: ****p < 0.0001. Compared with the same concentration of Control peptide group: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. (E) The targeting peptide CNTGSPYEC had a greater inhibitory effect on Co-HUVEC than HUVEC(n = 6). Compared with the same concentration of HUVEC group: ***p < 0.001

The results of the CCK8 assay are consistent with those of endothelial tube formation assay. the peptide CNTGSPYEC could reproducibly suppress the proliferation of Co-HUVEC. The inhibition was in dose-dependent manner. Differences in the relative cell number between cells treated with peptide CNTGSPYEC and the control peptide were non-significant for HUVEC (Fig. 5C), and were significant at concentrations of 10, 25, 50, 75 and 100 μM for Co-HUVEC (p < 0.01) (Fig. 5D). In addition, the targeting peptide CNTGSPYEC-induced inhibitory effects were more obvious in Co-HUVEC than in the HUVEC, with the inhibition rate increasing to 61.7% (Fig. 5E).

Discussion

The growth and metastasis of malignant tumors depends on an adequate blood supply, which can be achieved by the recruitment of vessels to establish microcirculation in tumors [21]. Tumor neovasculaturehas been demonstrated to be a promising therapeutic target for cancer therapy. Tumor blood vessels are more genetically stable than cancer cell so that they rarely induce drug resistance. Furthermore, tumor blood vessels have a set of molecules and markers distinguished from the normal blood vessels, which provides the possibility for specific tumor vasculature-targeting therapy. On the other hand, tumor microenvironment plays a unique role to govern angiogenesis and regulates the expression of marker proteins in tumor blood vessels [22, 23]. Even tumors from different organs or growth sites express different vascular zip codes, which is the basis of in vivo phage library screening [24–27].

The technique of phage display library provides us a powerful tool to obtain the specific binding peptides through a selection with desired binding properties [10, 28], which will lead to the delineation of a ligand-receptor-based map of the microvasculature in human cancer [6]. Screening phage libraries have yielded a series of peptides that are home to tumor, vascular vessels, and other targets. The novel peptide sequences could be used for targeting devices to concentrate drugs to the vasculatures in tumor. In our early research, we took the lead in employing phage display peptide library technology. Through in vivo screening, we initially obtained a cyclic nonapeptide that could enrich in gastric cancer vasculature, which was named GX1 [13, 15]. Further in vitro and in vivo experiments confirmed that the GX1 peptide could specifically accumulate in the endothelium of human gastric cancer vessels. However, we also found that GX1 exhibited some non-specific binding and proliferation inhibition to normal vasculature endothelial cells. The inhibition rate of GX1 on these side effects compromised the safety and efficacy of GX1 as a targeting molecule for subsequent targeted therapy of gastric cancer vasculature [11, 13, 14].

Therefore, we combined in vivo positive screening approach and in vitro negative depletion screening method to pre-deplete the phage library of irrelevant phages, thereby facilitating the acquisition of targeting phages. The evaluation of the screening results primarily relied on two parameters: binding efficiency and selection intensity. Binding efficiency was expressed as the ratio of the output phage number to the input phage number, called the output/input (O/I) ratio [29]. Selection intensity measures the impact of various experimental factors on the binding between the peptides displayed by the phages and the target in the screening. In general, the higher the selection intensity, the higher the proportion of positive clones, but the binding efficiency may decrease. We ensured a high binding efficiency in the first round of screening, and then gradually increase the selection intensity in subsequent rounds. Additionally, through multiple rounds of selection and amplification, the number of positively binding phage clones that specifically interact with the target would increase with each round, while non-specifically bound phages would be gradually eliminated. Our results demonstrated that the peptide CNTGSPYEC can specifically bind gastric cancer blood vessels with a competitive inhibition rate of 93%. According to some previous studies, Askoxylakis et al. [30] screened a peptide named p160 that targeted to neuroblastoma cells, and binding of the 125I-labeled p160 was inhibited up to 95% by the unlabeled peptide at a competitor concentration of 10− 4 mol/L. Besides, Zitzmann et al. [31] identified a new peptide FROP-1 binding to a variety of tumor cells such as thyroid and mammary carcinoma cells. The interaction between FROP-1 and thyroid cancer cells could be inhibited by more than 92% by the unlabeled peptide itself and this binding could also be inhibited by the unlabeled FROP-1 on the breast cancer cells. These studies provide some evidence for the specificity of the peptide CNTGSPYEC. Meanwhile, compared with the previously screened targeting peptides, peptide CNTGSPYEC could better inhibit the proliferation and tube-forming ability of gastric cancer vascular endothelial cells, and had less inhibitory effect on normal vascular endothelial cells. The peptide CNTGSPYEC may be a potential candidate in diagnosis and anti-angiogenesis therapy of gastric cancer.

Compared with in vitro screening, in vivo screening can better simulate the tumor microenvironment and the actual drug administration process. However, preliminary experimental results indicate that it is challenging to prevent the non-specific binding of the screened short peptides to normal blood vessels when using in vivo screening alone. The strategy of combining in vitro and in vivo screening uses normal vascular endothelial cells HUVEC and HMVEC as a pre-elimination phage library. This helps to exclude negative molecules that are unrelated to the screening target, thereby reducing the proportion of non-specific negative binding phages. Moreover, the co-culture model for endothelial cells can serve as an effective interim technique for studying the molecular heterogeneity of tumor microvascular endothelial cells. A recent study suggested that co-culturing cancer cells with vascular endothelial cells can replicate the conditions found in solid tumor masses [29]. Based on these findings, an in vitro model was developed to co-culture HUVECs with MKN45 to study the heterogeneous molecules present. Our study identified that Co-HUVECs exhibited accelerated proliferation without any changes in their adhesive capacity. This finding underscores the efficacy of our model in mimicking the regulation of endothelial cell properties by the tumor microenvironment.

Conclusions

In conclusion, A 9-mer cyclic peptide (CNTGSPYEC) targeting gastric cancer was identified using a novel strategy that combined both in vivo and in vitro screening of phage display. We present the application of phage display technology for screening and identifying specific peptides in endothelial cells of gastric cancer. To get around a technical challenge associated with isolating endothelial cells from gastric cancer, we refined the screening approach by utilizing phage display peptide libraries to identify short peptides that selectively accumulated in the vasculature of gastric cancer within tumor-bearing nude mice. Concurrently, an in vitro negative depletion strategy targeting normal vascular endothelial cells was applied to eliminate peptides that exhibited non-specific binding to normal blood vessels.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- CCK-8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- Co-HUVEC

A co-culture model by culturing HUVEC in tumor-conditioned medium

- Cy3

Sulfo-Cyanine3

- FBS

Heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum

- FITC

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- HMVEC

Human microvascular endothelial cell

- HPLC

High Performance Liquid Chromatography

- HUVEC

Human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- SRCA

Subrenal Capsule Assay

Author contributions

Y.Z., S.W., L.Z., B.C., and B.L. designed the experiments. Y.Z. and S.W. interpreted and wrote the manuscript. L.Z. collected data, processed statistical data, and performed the experiment. H.W. analyzed and interpreted the data. L.W., R.S. and S.C. partly contributed to the experiment. Y.Z. and B.C. wrote, reviewed, and revised the paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972895), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81101821) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (10451001002004732).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animals were maintained within specific pathogen-free facilities at the Laboratory Animal Center of Nanfang Hospital. All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanfang Hospital (permit and approval number: 202105A028) and performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines of Nanfang Hospital.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yan-ting Zhang, Sheng-hui Wang and Li Zhao contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Bao-feng Li, Email: w841671871@i.smu.edu.cn.

Bei Chen, Email: 3170020043@i.smu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bagley RG. Commentary on Folkman: tumor angiogenesis factor. Cancer Res. 2016;76(7):1673–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorrell JM, Baber MA, Caplan AI. A self-assembled fibroblast-endothelial cell co-culture system that supports in vitro vasculogenesis by both human umbilical vein endothelial cells and human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Cells Tissues Organs. 2007;186(3):157–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park HJ, Zhang Y, Georgescu SP, Johnson KL, Galper JB. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells and human dermal microvascular endothelial cells offer new insights into the relationship between lipid metabolism and angiogenesis. Stem Cell Reviews Rep. 2006;2(2):93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staton CA, Stribbling SM, Tazzyman S, Hughes R, Brown NJ, Lewis CE. Current methods for assaying angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Int J Exp Pathol. 2010;85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Hiratsuka S. Vasculogenensis, angiogenesis and special features of tumor blood vessels. Front Biosci. 2011;16:1413–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Onofrio N, Caraglia M, Grimaldi A, Marfella R, Servillo L, Paolisso G, Balestrieri ML. Vascular-homing peptides for targeted drug delivery and molecular imaging: meeting the clinical challenges. Biochim Biophys Acta-Rev Cancer. 2014;1846(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bock KD, Cauwenberghs S, Carmeliet P. Vessel abnormalization: another hallmark of cancer? Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21(1):73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachetti T, Morbidelli L. Endothelial cells in culture: a model for studying vascular functions. Pharmacol Res. 2000;42(1):9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohga N, Ishikawa S, Maishi N, Akiyama K, Hida Y, Kawamoto T, Sadamoto Y, Osawa T, Yamamoto K, Kondoh M. Heterogeneity of tumor endothelial cells: comparison between tumor endothelial cells isolated from high- and low-metastatic tumors. Am J Pathol. 2012;180(3):1294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saw PE, Song EW. Phage display screening of therapeutic peptide for cancer targeting and therapy. Protein Cell. 2019;10(11):787–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen B, Jin HF, Wu KC. Potential role of vascular targeted therapy to combat against tumor. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6(7):719–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vadevoo MP, Gurung S, Khan F, Haque ME, Gunassekaran GR, Chi LH, Permpoon U, Lee B. Peptide-based targeted therapeutics and apoptosis imaging probes for cancer therapy. Arch Pharm Res. 2019;42(2):150–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen B, Cao SS, Zhang YQ, Wang X, Liu J, Hui XL, Wan Y, Du WQ, Wang L, Wu KC, et al. A novel peptide (GX1) homing to gastric cancer vasculature inhibits angiogenesis and cooperates with TNF alpha in anti-tumor therapy. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui XL, Han Y, Liang SH, Liu ZG, Liu JT, Hong L, Zhao L, He L, Cao SS, Chen B, et al. Specific targeting of the vasculature of gastric cancer by a new tumor-homing peptide CGNSNPKSC. J Control Release. 2008;131(2):86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhi M, Wu KC, Dong L, Hao ZM, Deng TZ, Hong L, Liang SH, Zhao PT, Qiao TD, Wang Y, et al. Characterization of a specific phage-displayed peptide binding to vasculature of human gastric cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3(12):1232–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaffe EA, Nachman RL, Becker CG, Minick CR. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Investig. 1973;52(11):2745–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bogden AE, Cobb WR. The subrenal capsule assay (SRCA). Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1986;22(9):1033–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao J, Zhao P, Miao XH, Zhao LJ, Xue LJ. ZHONG TIAN QI: phage display selection on whole cells yields a small peptide specific for HCV receptor human CD81. Cell Res. 2003;13(6):p473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wender PA, Mitchell DJ, Pattabiraman K, Pelkey ET, Steinman L, Rothbard JB. The design, synthesis, and evaluation of molecules that enable or enhance cellular uptake: peptoid molecular transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(24):13003–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laakkonen P, Porkka K, Hoffman JA, Ruoslahti E. A tumor-homing peptide with a targeting specificity related to lymphatic vessels. Nat Med. 2002;8(7):751–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhong WL, Yang WD, Qin Y, Gu WG, Xue YY, Tang YH, Xu HW, Wang HZ, Zhang C, Wang CH, et al. 6-Gingerol stabilized the p-VEGFR2/VE-cadherin/-catenin/actin complex promotes microvessel normalization and suppresses tumor progression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jain RK. Normalizing tumor microenvironment to treat cancer: bench to bedside to biomarkers. J Clin Oncol Official J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2013;31(17):2205–U2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Tumor angiogenesis: molecular pathways and therapeutic targets. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1359–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li XB, Schluesener HJ, Xu SQ. Molecular addresses of tumors: selection by in vivo phage display. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2006;54(3):177–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sachie H. Vasculogenensis, angiogenesis and special features of tumor blood vessels. Front Biosci. 2011;16(1):1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teesalu T, Sugahara KN, Ruoslahti E. Mapping of vascular zip codes by phage display. In: Methods in Enzymology: Protein Engineering for Therapeutics, Vol 203, Pt B. Volume 503, edn. Edited by Wittrup KD, Verdine GL. San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press Inc; 2012: 35–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Nicolini A, Carpi A. Immune manipulation of advanced breast cancer: an interpretative model of the relationship between immune system and tumor cell biology. Med Res Rev. 2009;29(3):436–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joyce JA, Laakkonen P, Bernasconi M, Bergers G, Ruoslahti E, Hanahan D. Stage-specific vascular markers revealed by phage display in a mouse model of pancreatic islet tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(5):393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JW, Shin DH, Roh JL. Development of an < i > in vitro cell-sheet cancer model for chemotherapeutic screening. Theranostics. 2018;8(14):3964–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rana S, Nissen F, Lindner T, Altmann A, Mier W, Debus J, Haberkorn U, Askoxylakis V. Screening of a novel peptide targeting the proteoglycan-like region of human carbonic anhydrase IX. Mol Imaging. 2013;12(8):12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zitzmann S, Krämer S, Mier W, Hebling U, Altmann A, Rother A, Berndorff D, Eisenhut M, Haberkorn U. Identification and evaluation of a new tumor cell-binding peptide, FROP-1. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(6):965–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.