ABSTRACT

The reproductive tract of females lies at the core of humanity. The immensely complex process that leads to successful reproduction is miraculous yet invariably successful. Microorganisms have always been a cause for concern for their ability to infect this region, yet it is other, nonpathogenic microbial constituents now uncovered by sequencing technologies that offer hope for improving health. The universality of Lactobacillus species being associated with health is the basis for therapeutic opportunities, including through engineered strains. The manipulation of these and other beneficial constituents of the microbiota and their functionality, as well as their metabolites, forms the basis for new diagnostics and interventions. Within 20 years, we should see significant improvements in how cervicovaginal health is restored and maintained, thus providing relief to the countless women who suffer from microbiota-associated disorders.

SCOPE OF THIS REVIEW

In order to design and apply a therapeutic, there must be a vaginal disease or disorder in need of treatment or a condition influenced by the vaginal microbiota. There must also be a way for a new therapeutic agent to function through the microbiome. Those conditions include bacterial vaginosis (BV), aerobic vaginitis (AV), urinary tract infection, urethritis, cervicitis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, vulvodynia, endometriosis, and chorioamnitis. In addition, sexually transmitted infections are included, as arguably some may be prevented by vaginal microbes. Cancer is included, not only because of the association with viral infection, but also because microbial dysbiosis has been associated with cancers at other sites.

The size of this list demonstrates the enormity of not only the burden of disease among females but also the challenge of reviewing each satisfactorily and suggesting opportunities for novel approaches to prevention and treatment. Rather than provide exhaustive details of these conditions, I will refer the reader to appropriate articles for further insight and try to focus on the elements that offer an opportunity for intervention through microbial manipulation. Much of this will, by necessity, be conjecture, but hopefully reasoned and realistic.

THE CERVICOVAGINAL MICROBIOME AND ITS INFLUENCE ON HEALTH

Studies using various molecular methods over the past 15 years have provided insight into the array of microbes that can be detected in the vagina, vulva/labia, cervix, and uterus (1–18). The list is extensive, exceeding 250 bacterial species as well as yeast, Chlamydia, Archaea, viruses, and protozoa. Using statistical methodologies, attempts have been made to create groupings of bacterial species or genera into which the status of a given female might fall. In the first use of Illumina next-generation sequencing (NGS), we reported two major clusters (community state types [CSTs]) associated with a normal vaginal microbiota, one dominated by Lactobacillus iners and another by Lactobacillus crispatus (7). There were four CSTs strongly associated with BV, and these were dominated by Prevotella bivia, Gardnerella vaginalis, Lachnospiraceae, or a mixture of different species. This study of 132 subjects was more insightful than the one involving four phylum groups proposed from only 8 subjects (6), but there was still consistency in the findings of dominant lactobacilli or a mixed microbiota with depleted lactobacilli. Another study suggested one Lactobacillus grouping and three related to dysbiosis with the order Lachnospiraceae and genera Sneathia and Prevotella being dominant (19). Further studies in pregnant and nonpregnant HIV-negative women (8, 11) proposed five CST groupings: (i) Lactobacillus crispatus dominant; (ii) Lactobacillus gasseri dominant; (iii) L. iners dominant; (iv) Peptoniphilus, Prevotella, and Anaerococcus species and elevated Gardnerella or Ureaplasma abundances; and (v) Lactobacillus jensenii dominant. Despite issues with sampling, storage, processing, DNA extraction kits’ error rates from bias in samples, technical variation with PCR amplification, and the use of different primers and statistical methods (20–22), the creation of subgroups of microbiota is intended to help design better treatment strategies. But is it realistic?

The abject failure of industry to develop novel treatments for vaginal health in 40 or so years surely suggests that creating five to eight new ones is not likely to happen soon. In addition, simply identifying which organisms are present is inadequate information to devise new treatment strategies. Understanding how they got there and what they are doing is critically important. We performed the only transcriptomic study to date and showed that L. iners has the ability to adapt to the very different BV environment from that of a healthy vagina (23). Ideally, such a study should examine changes that occur to move the pendulum towards dysbiosis (Fig. 1). Ravel and others have performed such regular sampling over 16 weeks (9), but not using transcriptomics. Nevertheless, their findings and those of others (24–28) have shown that menstruation, sexual activity, spermicides, douching, and antibiotics can dramatically alter the species abundance. Thus, it is impossible to define a single composition associated with health. So, for all the impressive NGS studies that have been undertaken, the basic principle is the same as it was based on culture results 40 years ago, with a high presence of lactobacilli associated with health (29, 30). It remains to be seen whether women with one of the four species (L. crispatus, L. iners, Lactobacillus jensenii, Lactobacillus gasseri) are more protected against dysbiosis than women who do not harbor such species. To prove this, one would have to provide in vivo evidence that certain factors confer protective functions.

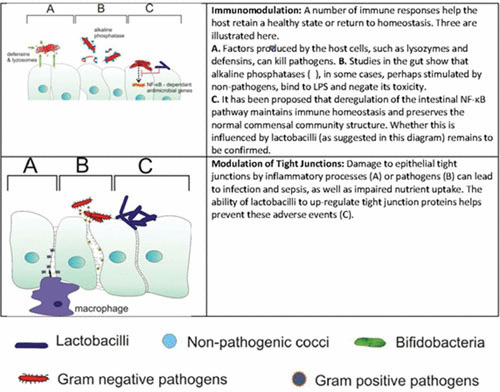

FIGURE 1a.

Different mechanisms by which beneficial microbes might influence vaginal health.

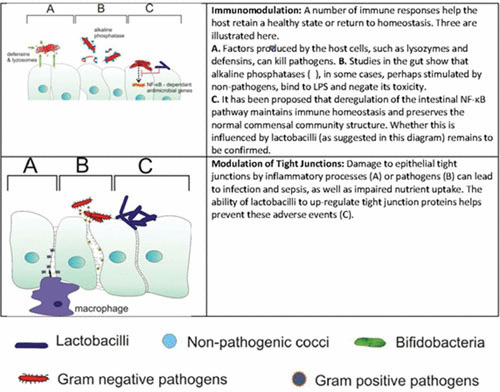

TARGETS FOR THERAPY: MECHANISMS WHEREBY LACTOBACILLI PROTECT THE HOST

One of the features of a microscopic analysis of a vaginal swab from a healthy woman is the number of epithelial cells with few adherent bacteria, mostly presumptive lactobacilli. If so few beneficial bacteria are “protecting” the host, how are they doing it? The theory that hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) produced by lactobacilli is the key defense mechanism (31) makes some sense, as this compound could inhibit the growth of pathogens. However, it has not been verified by a study measuring concentrations of H2O2 in the vagina. Therefore, the concentration required per milliliter of vaginal fluid or per surface area of epithelium is not known. Also, if it is protective, why do strains producing it, such as L. crispatus, become so apparently easy to displace when BV arises? Arguably, a more plausible protective mechanism, but also one that has not been proven in humans, is that biosurfactants produced by some strains of lactobacilli can cover cell surfaces and interfere with pathogen binding (32, 33) (Fig. 1). This process represents a thermodynamic effect, which has a good theoretical basis (34). Not only do the surface tensions of bacteria and host cells influence bacterial adhesion but so does also the suspending fluid. Thus, biosurfactants can alter the latter and make it less receptive to bacteria. Lactobacillus strains vary in the extent of biosurfactant production (35), but no studies have been done to determine if common vaginal isolates produce more than others. Efforts to purify biosurfactants and define their components and associated gene pathways have been limited, as have efforts to enhance their production. Industrialization of yeast-derived biosurfactants is being attempted (36), but not with vaginal applications in mind.

It is possible that bacteriocins or bacteriocin-like compounds are produced and help protect the host against pathogens, thereby leaving a relatively clear epithelial cell (37). But these compounds tend to have quite restricted target organisms, and it seems difficult to imagine that they control the wide range of BV and AV causative agents. Having said that, a recent study identified bacteriocin-like substances produced by vaginal lactobacilli that inhibited the growth of aerobic bacteria Klebsiella, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus faecalis and the yeast Candida parapsilosis as well as some Lactobacillus species (38). A strain of a somewhat rarer vaginal species, Lactobacillus pentosus, isolated from a healthy Nigerian woman, was found to contain a putative cluster of genes for biosynthesis of a cyclic bacteriocin precursor (39). It is not clear if such a strain would be more effective in African women than the four Lactobacillus species of the CSTs. No such association has been tested to date. While bacteriocins have been known for many years, few if any, and none for the vagina, have been developed as therapeutic agents. If this approach is to be effective, it may require a more targeted bacteriocin, such as directly against one pathogen. Group B streptococci would be one such target, given their prevalence, their danger to newborns, and the need to administer antibiotics in women at the time of delivery (40). An oral probiotic, Streptococcus salivarius, may be one option, given its bacteriocin activity against group B streptococci (41).

The possibility of controlling pathogenesis by coaggregating lactobacilli with pathogens and thereby tying up the latter’s ability to spread across surfaces, or by interfering with virulence expression such as production of toxins, has been considered (37) (Fig. 1). The latter concept suggests that a pathogen may not need to direct its energy to producing a toxin, if it can survive and colonize a surface. From a therapeutic point of view, the existence of a pathogen able to infect the host is not ideal, especially one such as S. aureus that can produce toxic shock toxin. But if the cocci are bound to lactobacilli, this potentially makes them less able to propagate and infect. In the case of Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14, cyclic dipeptides were identified to counter S. aureus toxins (42). Compounds such as these and quorum-sensing molecules, including coumarin, a natural plant phenolic compound, are being considered for antivirulence activity against a spectrum of pathogens (43).

The action of lactobacilli on host cell surfaces has been considered for a number of reasons. The most primitive is to simply block the access of pathogens to the surface. Such a competitive-exclusion model would require high inoculum volumes to cover the vaginal epithelium and repeated application, which seem impractical. Rather than blocking access to the host epithelium, this might provide a surface to which pathogens adhere (coaggregate), and if their subsequent growth is not reduced, they might persist. Nevertheless, some groups continue to pursue this competitive-exclusion concept, with genes that aid adherence and inhibit G. vaginalis proposed as a means for candidate probiotic L. crispatus to improve vaginal health (44). The ability of lactobacilli to improve epithelial integrity by upregulating tight-junction proteins has been shown (45). The question is why this would be advantageous to the lactobacilli. In fact, it may not be important to lactobacilli but rather may be a by-product of the metabolites that they produce. An interesting study on intestinal cells showed that Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG could increase tight-junction proteins Zonula occludens-1, claudin-1, and occludin gene expression by utilizing polyamines (46). Polyamines are found in the vagina and can be used by Trichomonas to adhere and infect (47), so the potential exists for lactobacilli to compete for these compounds and improve epithelial integrity.

The nature of the vagina in reproductive-age women is such that different levels of inflammatory processes occur during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. The ability to maintain immune homeostasis requires more than microbial modulation, but certainly microbes can influence the process. Alternatively, the process can influence the microbes. For example, during menstruation, the bacterial diversity appears to increase, albeit with variations among individuals (48). The ability to influence mucosal immunity using vaccines, antibodies, and antigens has been successful, but in the urogenital tract, modulation affecting bacterial dysbiosis has not been attempted. One exception has been efforts to create a multisubunit vaccine that elicits antibody against uropathogenic E. coli (49). Studies in mice are encouraging, and the concept has great appeal, as this process would stimulate IgG and not eradicate the commensal lactobacilli as antibiotics do. Other vaccine approaches include using flagellin proteins from Pseudomonas aeruginosa to passively immunize against pyelonephritis (50). Immune modulation to prevent BV has not been attempted, and one study of patients receiving a quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine (HPV–6, –11, –16, and –18) surprisingly reported an increase in the management rate of Gardnerella/BV in women aged 50 years and older (51). If indeed vaccines increase the risk of BV, this requires closer investigation. A Hungarian vaccine comprising five inactivated strains of lactobacilli administered prophylactically to women was reported to prevent BV, but this approach seems more like a way to circumvent drug regulations requiring to deliver living bacteria than a true vaccine (52). Why would dead or inactivated lactobacilli be better at inducing a protective immune response than live lactobacilli? While one study has shown that heat-treated Lactobacillus paracasei NCC 2461 stabilizes interleukin-10 (IL–10) mRNA (53), IL-10 has not been shown to mediate vaginal protection against pathogens.

Aerobic vaginitis is more of an inflammatory disease than BV (54), so it would be interesting to test if vaccines against E. coli, streptococci, and staphylococci make an impact on this condition.

Overall, there is no clear path at present to enhance the vaginal mucosal immune parameters over the menstrual cycle, to reduce the recurrence of BV. Stimulation of anti-BV host defenses to the point of being effective without increasing inflammation and discharge will not be simple, but one case study using intravaginally administered L. rhamnosus GR-1 (1 × 109 cells in 1 ml once daily for 5 days) suggested that it may potentially work (45).

Can Targets Be Developed from Metabolomics Data?

While the cell surfaces per se of bacteria mediate activity in the host and the response can influence outcomes, the metabolic by-products are also important. The compounds that bacteria produce are clearly influenced by the organisms’ genomic capabilities, the nutrients available, the microbial milieu in which they live, and environmental factors such as pH, mucins, antimicrobials, hormones, host cells, and immune factors.

Studies of the metabolome of vaginal bacteria are relatively recent, using liquid and gas chromatography with mass spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and databases that can interpret the resultant spectra (55–57). These studies have identified lactic acid, acetic acid, glycerol, and other metabolites consistent with the known capacities of lactobacilli and other vaginal organisms. Our study (57) was the first to identify and verify metabolites associated with high diversity and clinical BV, specifically 2-hydroxyisovalerate and γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), but not succinate as others had previously reported (58). This provides a means to develop a diagnostic system to detect GHB in vaginal swabs. If combined with elevated pH, it would likely be an effective tool to identify patients requiring therapy.

For AV, no such studies have been undertaken, but given the nature of the aerobic organisms and infection, it should be feasible to identify levels of lipopolysaccharide or other inflammatory compounds in vaginal fluid.

Engineered Strains to Deliver Vaccines

The encouraging results from probiotic applications to various areas of the host have stimulated the search for ways to further enhance benefits. One way would be to engineer bacteria either to deliver specific factors that promote health or prevent disease or to increase the production of compounds known to provide benefits.

The first efforts to engineer lactic acid bacteria for this purpose came from the insertion of murine IL-2 into lactococci (59). This was a precursor for the creation of strains engineered with biological containment (60) designed to deliver IL-10 to treat inflammatory bowel disease (61). However, these efforts have so far failed to make a clinical impact.

For vaginal applications, Mercenier et al. (62) were the first to consider using lactobacilli to increase mucosal immunity against pathogens such as Chlamydia trachomatis, but these efforts fell by the wayside. With the intent of preventing HIV infection in women, Lee and others (63) engineered an L. jensenii strain that secreted 2D CD4, which recognized a conformation-dependent anti-CD4 antibody and bound HIV type 1 gp120. They have continued their research to express single-chain and single-domain antibodies in L. jensenii 1153-1128 to passively transfer these antibodies to the mucosa and through colonization of the lactobacilli provide protection at the vaginal site of HIV transmission (64). Using a different approach, we genetically modified L. reuteri RC-14 to produce HIV entry or fusion inhibitors fused to the native expression and secretion signals of BspA, Mlp, or Sep proteins capable of blocking the three main steps of HIV entry into human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (65). The expression cassettes were stably inserted into the chromosome, but funding for the project was not forthcoming, so progress was halted. It remains to be seen if these approaches will be sufficiently effective and affordable to warrant large-scale applications, especially to countries where sexual transmission of the virus is most prevalent.

A final recombination strategy is being considered by Israeli researchers following studies that showed that lactobacilli are important for sperm motility and conception (66). The idea is to inhibit this Lactobacillus function and presumably then make the sperm less mobile and more apt to not reach the egg (http://nocamels.com/2013/02/the-new-contraceptive-suppository-that-disables-sperm/). The challenges with this approach are many, including overcoming the sheer number and mobility of the sperm, covering the whole area that semen reaches, and taking into account the vaginal microbiota, which if colonized by Prevotella or Pseudomonas (67) may inhibit fertilization but if colonized by competing lactobacilli may not.

COMMUNITY PROBIOTICS

Given the success of fecal microbiota transplantation in curing Clostridium difficile infections (68), the concept of using a full microbiome from one person to reset the aberrant microbiome of another is being considered for niches other than the gut. The use of antibiotics to prepare the gut for entrance of a new microbiota has been important so far, and potentially it could also eradicate many vaginal organisms. On the other hand, if it led to recalcitrant biofilms, persister strains, and invasion of epithelial cells, as in the bladder (69, 70), this could perhaps reduce the ability of the implanted microbiota to fully take over.

Much research is needed to determine the ideal composition of a donor vaginal microbiota. While the proportion of species may be identifiable, it should be appreciated that these organisms were presumably arranged by early life factors, diet, hormones, and metabolic linkages. Some of these will inevitably differ in a recipient. Nevertheless, this approach will no doubt be tested. This may require a sponge to collect the microbiota from the donor or use a synthetically prepared microbial collection, similar to that designed by Allen-Vercoe for the gut (71). The latter has the advantage of being devoid of virulence factors and phage, but the potential disadvantage of not coming from the vagina per se, where metabolic interactions had been actively occurring just prior to transplant. Presumably, this real-time functionality is at the core of fecal microbiota transplant success.

It would be particularly interesting to assess whether microbiota transplants could reverse the risk of reproductive tract cancers. One mechanism might be to reduce viral shedding and enhance immune defenses in women with early abnormalities, for example, those associated with HPV infection. Another might be to reduce recurrence of BV and AV, conditions that may be associated with a higher risk of cancer. Further research is required to link dysbiosis with cancer and to assess how lactobacilli influence carcinogenesis of the reproductive tract.

SUMMARY

It does not seem that long ago that our work on beneficial bacteria in the female urogenital tract was met with disdain or disregard. Today, the level of interest in this area is astounding, crossing all parts of life from soil and plants to fish and animals and every part of the human body. A multibillion-dollar industry continues to expand, and consumers the world over, with the exception of Africa, are using probiotics to restore and maintain health.

Likewise, interest in the reproductive tract microbiome has also seen a resurgence, which is long overdue considering the relatively primitive diagnostic and treatment options that have been available to women. Dysbiosis in the tract is frequent and can be debilitating for the woman and influential in the fetus. Our level of understanding of these microbiotas has increased significantly with NGS technology, but it must continue, particularly using functional investigations, if we are to truly improve lifelong reproductive tract health. Therapeutic options will emerge from such research for diagnostics and for treatment and maintenance. The ability to manipulate the microbiome through probiotics, prebiotics, and bacterial metabolites would reduce our reliance on unnatural chemical drugs and empower women if they wish to self-manage their vaginal health. Currently, only the use of urine dipsticks for urinary tract infection and antifungals for vulvovaginal candidiasis are accessible over the counter. This is changing with access to probiotics, but further clinical studies are needed to align which composition is best for which subject. Such personalized care will be feasible, especially since only relatively few CSTs are present, and each woman will presumably fit one of them.

Markers of success will be the extent to which innovations are funded sufficiently to continue through human testing and the extent to which clinicians and regulators embrace this new microbiome paradigm.

FIGURE 1b.

Different mechanisms by which beneficial microbes might influence vaginal health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Our work is funded by a Vogue Team grant from CIHR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burton JP, Reid G. 2002. Evaluation of the bacterial vaginal flora of 20 postmenopausal women by direct (Nugent score) and molecular (polymerase chain reaction and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis) techniques. J Infect Dis 186:1770–1780. 10.1086/345761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinemann C, Reid G. 2005. Vaginal microbial diversity among postmenopausal women with and without hormone replacement therapy. Can J Microbiol 51:777–781. 10.1139/w05-070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thies FL, König W, König B. 2007. Rapid characterization of the normal and disturbed vaginal microbiota by application of 16S rRNA gene terminal RFLP fingerprinting. J Med Microbiol 56:755–761. 10.1099/jmm.0.46562-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown CJ, Wong M, Davis CC, Kanti A, Zhou X, Forney LJ. 2007. Preliminary characterization of the normal microbiota of the human vulva using cultivation-independent methods. J Med Microbiol 56:271–276. 10.1099/jmm.0.46607-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schellenberg J, Links MG, Hill JE, Dumonceaux TJ, Peters GA, Tyler S, Ball TB, Severini A, Plummer FA. 2009. Pyrosequencing of the chaperonin-60 universal target as a tool for determining microbial community composition. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:2889–2898. 10.1128/AEM.01640-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim TK, Thomas SM, Ho M, Sharma S, Reich CI, Frank JA, Yeater KM, Biggs DR, Nakamura N, Stumpf R, Leigh SR, Tapping RI, Blanke SR, Slauch JM, Gaskins HR, Weisbaum JS, Olsen GJ, Hoyer LL, Wilson BA. 2009. Heterogeneity of vaginal microbial communities within individuals. J Clin Microbiol 47:1181–1189. 10.1128/JCM.00854-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hummelen R, Fernandes AD, Macklaim JM, Dickson RJ, Changalucha J, Gloor GB, Reid G. 2010. Deep sequencing of the vaginal microbiota of women with HIV. PLoS One 5:e12078. 10.1371/journal.pone.0012078 [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SS, McCulle SL, Karlebach S, Gorle R, Russell J, Tacket CO, Brotman RM, Davis CC, Ault K, Peralta L, Forney LJ. 2011. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(Suppl 1):4680–4687. 10.1073/pnas.1002611107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gajer P, Brotman RM, Bai G, Sakamoto J, Schütte UM, Zhong X, Koenig SS, Fu L, Ma ZS, Zhou X, Abdo Z, Forney LJ, Ravel J. 2012. Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Sci Transl Med 4:132ra52. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wylie KM, Mihindukulasuriya KA, Zhou Y, Sodergren E, Storch GA, Weinstock GM. 2014. Metagenomic analysis of double-stranded DNA viruses in healthy adults. BMC Biol 12:71. 10.1186/s12915-014-0071-7 [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiGiulio DB, Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Costello EK, Lyell DJ, Robaczewska A, Sun CL, Goltsman DS, Wong RJ, Shaw G, Stevenson DK, Holmes SP, Relman DA. 2015. Temporal and spatial variation of the human microbiota during pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:11060–11065. 10.1073/pnas.1502875112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamames J, Abellán JJ, Pignatelli M, Camacho A, Moya A. 2010. Environmental distribution of prokaryotic taxa. BMC Microbiol 10:85. 10.1186/1471-2180-10-85 [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dridi B, Raoult D, Drancourt M. 2011. Archaea as emerging organisms in complex human microbiomes. Anaerobe 17:56–63. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirt RP, Sherrard J. 2015. Trichomonas vaginalis origins, molecular pathobiology and clinical considerations. Curr Opin Infect Dis 28:72–79. 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borgdorff H, Verwijs MC, Wit FW, Tsivtsivadze E, Ndayisaba GF, Verhelst R, Schuren FH, van de Wijgert JH. 2015. The impact of hormonal contraception and pregnancy on sexually transmitted infections and on cervicovaginal microbiota in African sex workers. Sex Transm Dis 42:143–152. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ling Z, Liu X, Chen X, Zhu H, Nelson KE, Xia Y, Li L, Xiang C. 2011. Diversity of cervicovaginal microbiota associated with female lower genital tract infections. Microb Ecol 61:704–714. 10.1007/s00248-011-9813-z [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng NN, Guo XC, Lv W, Chen XX, Feng GF. 2013. Characterization of the vaginal fungal flora in pregnant diabetic women by 18S rRNA sequencing. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 32:1031–1040. 10.1007/s10096-013-1847-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell CM, Haick A, Nkwopara E, Garcia R, Rendi M, Agnew K, Fredricks DN, Eschenbach D. 2015. Colonization of the upper genital tract by vaginal bacterial species in nonpregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 212:611.e1–611.e9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muzny CA, Sunesara IR, Kumar R, Mena LA, Griswold ME, Martin DH, Lefkowitz EJ, Schwebke JR, Swiatlo E. 2013. Characterization of the vaginal microbiota among sexual risk behavior groups of women with bacterial vaginosis. PLoS One 8:e80254. 10.1371/journal.pone.0080254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Bella JM, Bao Y, Gloor GB, Burton JP, Reid G. 2013. High throughput sequencing methods and analysis for microbiome research. J Microbiol Methods 95:401–414. 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandes AD, Reid JN, Macklaim JM, McMurrough TA, Edgell DR, Gloor GB. 2014. Unifying the analysis of high-throughput sequencing datasets: characterizing RNA-seq, 16S rRNA gene sequencing and selective growth experiments by compositional data analysis. Microbiome 2:15. 10.1186/2049-2618-2-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooks JP, Edwards DJ, Harwich MD II, Rivera MC, Fettweis JM, Serrano MG, Reris RA, Sheth NU, Huang B, Girerd P, Vaginal Microbiome Consortium, Strauss JF III, Jefferson KK, Buck GA. 2015. The truth about metagenomics: quantifying and counteracting bias in 16S rRNA studies. BMC Microbiol 15:66. 10.1186/s12866-015-0351-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macklaim JM, Fernandes AD, Di Bella JM, Hammond JA, Reid G, Gloor GB. 2013. Comparative meta-RNA-seq of the vaginal microbiota and differential expression by Lactobacillus iners in health and dysbiosis. Microbiome 1:12. 10.1186/2049-2618-1-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGroarty JA, Reid G, Bruce AW. 1994. The influence of nonoxynol-9-containing spermicides on urogenital infection. J Urol 152:831–833. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reid G, Bruce AW, Cook RL, Llano M. 1990. Effect on urogenital flora of antibiotic therapy for urinary tract infection. Scand J Infect Dis 22:43–47. 10.3109/00365549009023118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravel J, Gajer P, Fu L, Mauck CK, Koenig SS, Sakamoto J, Motsinger-Reif AA, Doncel GF, Zeichner SL. 2012. Twice-daily application of HIV microbicides alter the vaginal microbiota. MBio 3:e00370-12. 10.1128/mBio.00370-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown JM, Hess KL, Brown S, Murphy C, Waldman AL, Hezareh M. 2013. Intravaginal practices and risk of bacterial vaginosis and candidiasis infection among a cohort of women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 121:773–780. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31828786f8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayer BT, Srinivasan S, Fiedler TL, Marrazzo JM, Fredricks DN, Schiffer JT. 2015. Rapid and profound shifts in the vaginal microbiota following antibiotic treatment for bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis 212:793–802. 10.1093/infdis/jiv079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Louvois J, Hurley R, Stanley VC. 1975. Microbial flora of the lower genital tract during pregnancy: relationship to morbidity. J Clin Pathol 28:731–735. 10.1136/jcp.28.9.731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruce AW, Chadwick P, Hassan A, VanCott GF. 1973. Recurrent urethritis in women. Can Med Assoc J 108:973–976. [PubMed] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schellenberg JJ, Dumonceaux TJ, Hill JE, Kimani J, Jaoko W, Wachihi C, Mungai JN, Lane M, Fowke KR, Ball TB, Plummer FA. 2012. Selection, phenotyping and identification of acid and hydrogen peroxide producing bacteria from vaginal samples of Canadian and East African women. PLoS One 7:e41217. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Velraeds MM, van der Mei HC, Reid G, Busscher HJ. 1997. Inhibition of initial adhesion of uropathogenic Enterococcus faecalis to solid substrata by an adsorbed biosurfactant layer from Lactobacillus acidophilus. Urology 49:790–794. 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Velraeds MM, van de Belt-Gritter B, van der Mei HC, Reid G, Busscher HJ. 1998. Interference in initial adhesion of uropathogenic bacteria and yeasts to silicone rubber by a Lactobacillus acidophilus biosurfactant. J Med Microbiol 47:1081–1085. 10.1099/00222615-47-12-1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Absolom DR, Lamberti FV, Policova Z, Zingg W, van Oss CJ, Neumann AW. 1983. Surface thermodynamics of bacterial adhesion. Appl Environ Microbiol 46:90–97. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velraeds MMC, van der Mei HC, Reid G, Busscher HJ. 1996. Physicochemical and biochemical characterization of biosurfactants released from Lactobacillus strains. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 8:51–61. 10.1016/S0927-7765(96)01297-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roelants SL, Ciesielska K, De Maeseneire SL, Moens H, Everaert B, Verweire S, Denon Q, Vanlerberghe B, Van Bogaert IN, Van der Meeren P, Devreese B, Soetaert W. 2016. Towards the industrialization of new biosurfactants: biotechnological opportunities for the lactone esterase gene from Starmerella bombicola. Biotechnol Bioeng 113:550–559. 10.1002/bit.25815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reid G, Younes JA, Van der Mei HC, Gloor GB, Knight R, Busscher HJ. 2011. Microbiota restoration: natural and supplemented recovery of human microbial communities. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:27–38. 10.1038/nrmicro2473 [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stoyancheva G, Marzotto M, Dellaglio F, Torriani S. 2014. Bacteriocin production and gene sequencing analysis from vaginal Lactobacillus strains. Arch Microbiol 196:645–653. 10.1007/s00203-014-1003-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anukam KC, Macklaim JM, Gloor GB, Reid G, Boekhorst J, Renckens B, van Hijum SA, Siezen RJ. 2013. Genome sequence of Lactobacillus pentosus KCA1: vaginal isolate from a healthy premenopausal woman. PLoS One 8:e59239. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ, Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2010. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease--revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 59(RR-10):1–36. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patras KA, Wescombe PA, Rösler B, Hale JD, Tagg JR, Doran KS. 2015. Streptococcus salivarius K12 limits group B Streptococcus vaginal colonization. Infect Immun 83:3438–3444. 10.1128/IAI.00409-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J, Wang W, Xu SX, Magarvey NA, McCormick JK. 2011. Lactobacillus reuteri-produced cyclic dipeptides quench agr-mediated expression of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 in staphylococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:3360–3365. 10.1073/pnas.1017431108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gutiérrez-Barranquero JA, Reen FJ, McCarthy RR, O’Gara F. 2015. Deciphering the role of coumarin as a novel quorum sensing inhibitor suppressing virulence phenotypes in bacterial pathogens. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:3303–3316. 10.1007/s00253-015-6436-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ojala T, Kankainen M, Castro J, Cerca N, Edelman S, Westerlund-Wikström B, Paulin L, Holm L, Auvinen P. 2014. Comparative genomics of Lactobacillus crispatus suggests novel mechanisms for the competitive exclusion of Gardnerella vaginalis. BMC Genomics 15:1070. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirjavainen PK, Laine RM, Carter D, Hammond J-A, Reid G. 2008. Expression of anti-microbial defense factors in vaginal mucosa following exposure to Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1. Int J Probiotics 3:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orlando A, Linsalata M, Notarnicola M, Tutino V, Russo F. 2014. Lactobacillus GG restoration of the gliadin induced epithelial barrier disruption: the role of cellular polyamines. BMC Microbiol 14:19. 10.1186/1471-2180-14-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia AF, Benchimol M, Alderete JF. 2005. Trichomonas vaginalis polyamine metabolism is linked to host cell adherence and cytotoxicity. Infect Immun 73:2602–2610. 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2602-2610.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hickey RJ, Abdo Z, Zhou X, Nemeth K, Hansmann M, Osborn TW III, Wang F, Forney LJ. 2013. Effects of tampons and menses on the composition and diversity of vaginal microbial communities over time. BJOG 120:695–704, discussion 704–706. 10.1111/1471-0528.12151 [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mobley HL, Alteri CJ. 2015. Development of a vaccine against Escherichia coli urinary tract infections. Pathogens 5(1).pii:E1 10.3390/pathogens5010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabharwal N, Chhibber S, Harjai K. 2016. Divalent flagellin immunotherapy provides homologous and heterologous protection in experimental urinary tract infections in mice. Int J Med Microbiol 306:29–37. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harrison C, Britt H, Garland S, Conway L, Stein A, Pirotta M, Fairley C. 2014. Decreased management of genital warts in young women in Australian general practice post introduction of national HPV vaccination program: results from a nationally representative cross-sectional general practice study. PLoS One 9:e105967. 10.1371/journal.pone.0105967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lazar E, Varga R. 2011. Gynevac-a vaccine, containing lactobacillus for therapy and prevention of bacterial vaginosis and related diseases. Akush Ginekol (Sofiia) 50:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Demont A, Hacini-Rachinel F, Doucet-Ladevèze R, Ngom-Bru C, Mercenier A, Prioult G, Blanchard C. 2016. Live and heat-treated probiotics differently modulate IL10 mRNA stabilization and microRNA expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol 137:1264–7.e1, 10. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.033 [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Donders GG, Vereecken A, Bosmans E, Dekeersmaecker A, Salembier G, Spitz B. 2002. Definition of a type of abnormal vaginal flora that is distinct from bacterial vaginosis: aerobic vaginitis. BJOG 109:34–43. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.00432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gajer P, Brotman RM, Bai G, Sakamoto J, Schütte UM, Zhong X, Koenig SS, Fu L, Ma ZS, Zhou X, Abdo Z, Forney LJ, Ravel J. 2012. Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Sci Transl Med 4:132ra52. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yeoman CJ, Thomas SM, Miller ME, Ulanov AV, Torralba M, Lucas S, Gillis M, Cregger M, Gomez A, Ho M, Leigh SR, Stumpf R, Creedon DJ, Smith MA, Weisbaum JS, Nelson KE, Wilson BA, White BA. 2013. A multi-omic systems-based approach reveals metabolic markers of bacterial vaginosis and insight into the disease. PLoS One 8:e56111. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McMillan A, Rulisa S, Sumarah M, Macklaim JM, Renaud J, Bisanz JE, Gloor GB, Reid G. 2015. A multi-platform metabolomics approach identifies highly specific biomarkers of bacterial diversity in the vagina of pregnant and non-pregnant women. Sci Rep 5:14174. 10.1038/srep14174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Srinivasan S, Morgan MT, Fiedler TL, Djukovic D, Hoffman NG, Raftery D, Marrazzo JM, Fredricks DN. 2015. Metabolic signatures of bacterial vaginosis. mBio 6:e00204–e00215. 10.1128/mBio.00204-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steidler L, Wells JM, Raeymaekers A, Vandekerckhove J, Fiers W, Remaut E. 1995. Secretion of biologically active murine interleukin-2 by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:1627–1629. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steidler L, Neirynck S, Huyghebaert N, Snoeck V, Vermeire A, Goddeeris B, Cox E, Remon JP, Remaut E. 2003. Biological containment of genetically modified Lactococcus lactis for intestinal delivery of human interleukin 10. Nat Biotechnol 21:785–789. 10.1038/nbt840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vandenbroucke K, Hans W, Van Huysse J, Neirynck S, Demetter P, Remaut E, Rottiers P, Steidler L. 2004. Active delivery of trefoil factors by genetically modified Lactococcus lactis prevents and heals acute colitis in mice. Gastroenterology 127:502–513. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mercenier A, Müller-Alouf H, Grangette C. 2000. Lactic acid bacteria as live vaccines. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2:17–25 [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chang TL, Chang CH, Simpson DA, Xu Q, Martin PK, Lagenaur LA, Schoolnik GK, Ho DD, Hillier SL, Holodniy M, Lewicki JA, Lee PP. 2003. Inhibition of HIV infectivity by a natural human isolate of Lactobacillus jensenii engineered to express functional two-domain CD4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:11672–11677. 10.1073/pnas.1934747100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marcobal A, Liu X, Zhang W, Dimitrov A, Jia L, Lee PP, Fouts T, Parks TP, Lagenaur LA. 2016. Expression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1neutralizing antibody fragments using human vaginal Lactobacillus. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 32:964–971. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu JJ, Reid G, Jiang Y, Turner MS, Tsai CC. 2007. Activity of HIV entry and fusion inhibitors expressed by the human vaginal colonizing probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14. Cell Microbiol 9:120–130. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00772.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barbonetti A, Vassallo MR, Cinque B, Filipponi S, Mastromarino P, Cifone MG, Francavilla S, Francavilla F. 2013. Soluble products of Escherichia coli induce mitochondrial dysfunction-related sperm membrane lipid peroxidation which is prevented by lactobacilli. PLoS One 8:e83136. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weng SL, Chiu CM, Lin FM, Huang WC, Liang C, Yang T, Yang TL, Liu CY, Wu WY, Chang YA, Chang TH, Huang HD. 2014. Bacterial communities in semen from men of infertile couples: metagenomic sequencing reveals relationships of seminal microbiota to semen quality. PLoS One 9:e110152. 10.1371/journal.pone.0110152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fuentes S, van Nood E, Tims S, Heikamp-de Jong I, ter Braak CJ, Keller JJ, Zoetendal EG, de Vos WM. 2014. Reset of a critically disturbed microbial ecosystem: faecal transplant in recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. ISME J 8:1621–1633. 10.1038/ismej.2014.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Anderson GG, Palermo JJ, Schilling JD, Roth R, Heuser J, Hultgren SJ. 2003. Intracellular bacterial biofilm-like pods in urinary tract infections. Science 301:105–107. 10.1126/science.1084550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goneau LW, Hannan TJ, MacPhee RA, Schwartz DJ, Macklaim JM, Gloor GB, Razvi H, Reid G, Hultgren SJ, Burton JP. 2015. Subinhibitory antibiotic therapy alters recurrent urinary tract infection pathogenesis through modulation of bacterial virulence and host immunity. mBio 6:e00356–e15. 10.1128/mBio.00356-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petrof EO, Gloor GB, Vanner SJ, Weese SJ, Carter D, Daigneault MC, Brown EM, Schroeter K, Allen-Vercoe E. 2013. Stool substitute transplant therapy for the eradication of Clostridium difficile infection: ‘RePOOPulating’ the gut. Microbiome 1:3. 10.1186/2049-2618-1-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]