Abstract

Despite recognition that spiritual concerns contribute to caregiver burden, little is known about spirituality, spiritual well-being, and spiritual distress in Parkinson’s disease caregivers. In this scoping review of the literature through October 2022, we searched PubMed, PsychINFO, Embase, and CINAHL. From an initial pool of 328 studies, 14 were included. Caregiver factors (e.g., depression, age) and patient factors (e.g., faith, motor function) affected caregiver spirituality and spiritual well-being. Caregivers experienced loss of meaning, existential guilt, and loneliness, and coped through acquiescence, cultural beliefs, prayer, and gratitude. Future research should focus on the specific spiritual needs of Parkinson’s disease caregivers and interventions to address them.

Keywords: Spirituality, Spiritual distress, Parkinson’s disease, Caregivers, Scoping review

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disease world-wide and the fastest growing neurological disorder in terms of prevalence, disability, and death (Doris et al., 2018). There is compelling evidence from systematic and scoping reviews of the literature that multiple factors lead to poor quality of life for Parkinson’s disease patients (Perepezko et al., 2023) and their caregivers (Martinez-Martin et al., 2012). Factors that contribute to caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease include disease-related symptoms (e.g., dyskinesias, cognitive impairment, apathy, neuropsychiatric symptoms), and caregiver-related factors (e.g., depression, anxiety, decreased social support, medical and psychiatric comorbidities) (Aamodt et al., 2023; Mosley et al., 2017). People with Parkinson’s disease experience multiple debilitating symptoms that are a leading cause for caregiver strain, and spiritual and existential distress among both patients and their caregivers. Recently, there has been an increasing interest and discussion on the role of religiosity and spirituality among persons with Parkinson’s disease. In a longitudinal study of older individuals in England and the United States, high religiosity in adulthood was associated with a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (Otaiku, 2022). These findings have prompted further discussion on the relationship between religiosity, spirituality, and Parkinson’s disease (Koenig, 2023; Paal et al., 2023), raising awareness on the importance of spiritual care for persons with Parkinson’s disease. The unmet needs of patients with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers can lead to loss of faith in both higher powers and in the healthcare system (Paal et al., 2020) as well as spiritual distress, loss of meaning, demoralization, and a sense of hopelessness (Kluger & Arnold, 2023).

With the goal to improve quality of life and reduce suffering, palliative care is an approach to Parkinson’s disease care that can address the psychosocial and spiritual needs of patients as well as their caregivers (Holloway & Kramer, 2022; Kluger et al., 2021). In 2009, a consensus conference report concluded that spiritual care was a fundamental part of palliative care (Puchalski et al., 2009). It was recommended that spiritual care not only be considered an integral part of patient-centered care, but also that spiritual distress be treated with the same urgency as any other medical problem (Puchalski et al., 2009). Though spirituality may encompass people’s religious beliefs and practices, it goes beyond religion (Balboni et al., 2022) as even those without religious affiliations may have spiritual needs. Spirituality is “a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity” that “is expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices” and enables people to find meaning, purpose, and transcendence (Balboni et al., 2022; Puchalski et al., 2014). Spirituality is particularly important in serious illness when people may struggle to understand reasons for their suffering or may find a sense of purpose and experience transcendence in the midst of suffering.

There is increasing evidence that participation in religious and spiritual communities is associated with protective health benefits (Balboni et al., 2022). For example, spirituality and religiosity are known to contribute to improved quality of life and coping among caregivers of patients with cancer (Delgado-Guay et al., 2013; Weaver & Flannelly, 2004). In a meta-synthesis of the literature on family caregivers of adult and elderly patients with cancer receiving palliative care, religious beliefs and faith in a higher power were found to provide caregivers with the means to cope with the disease and associated uncertainties (Bhasin & Bharadwaj, 2021). Among caregivers of hemodialysis patients in Iran, spiritual well-being was found to be inversely correlated with caregiver burden (Rafati et al., 2020). Although the spiritual needs of caregivers of persons with serious illnesses and others nearing end-of-life are well documented, (Benites et al., 2021; Murray et al., 2004), little is known about the spiritual needs of caregivers of persons with Parkinson’s disease.

Significance of this Review

Neurologists frequently have difficult life-altering discussions with patients and families. Adding spirituality to these discussions with the support of allied healthcare professionals such as chaplains or spiritual counselors can improve quality of life (Varon, 2022). Among patients with Parkinson’s disease, spiritual care is increasingly being recognized as being as important as physical and emotional care (Paal & Lorenzl, 2020) and numerous studies have explored different aspects of spirituality and the spiritual needs of Parkinson’s disease patients (Gao et al., 2022; Giaquinto et al., 2011; Hermanns, 2011; Hermanns et al., 2012; Prizer et al., 2020b; Redfern & Coles, 2015; Reynolds, 2017). However, despite the recognition that spiritual distress is an important component of caregiver burden and strain in Parkinson’s disease (Mosley et al., 2017), there is limited knowledge of spirituality and spiritual distress among Parkinson’s disease caregivers. This scoping review of the literature addresses this gap in knowledge and is the first study to synthesize the state of current knowledge on the topic. It provides an important foundation for understanding existing gaps in the literature and may offer guidance for future research as well as clinical care in settings that use a palliative care approach for Parkinson’s disease.

The objectives of this scoping review are to provide an evidence-based summary of the literature related to (a) factors associated with Parkinson’s disease caregiver spirituality, (b) spiritual distress in Parkinson’s disease caregivers, (c) instruments and measures used to assess Parkinson’s disease caregiver spirituality, and (d) strategies used by Parkinson’s disease caregivers to cope with spiritual questions and existential struggles.

Methods

A scoping review of the literature was determined to be the ideal method to summarize the literature by describing the concept of spirituality, identifying key factors of spiritual distress, and mapping available evidence to provide a foundation for future research (Munn et al., 2018). The steps used to conduct the scoping review and identify the gaps in the literature were consistent with those described by Arksey and O’Malley (2005). These steps included identifying the research questions, selecting studies, charting, and summarizing the results (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Relevant studies were identified based on the following research questions:

What factors are associated with spirituality among Parkinson’s disease caregivers?

What is the spiritual distress experienced by Parkinson’s disease caregivers?

What instruments or measures exist to assess Parkinson’s disease caregiver spirituality?

What strategies do Parkinson’s disease caregivers use to cope with spiritual or existential distress?

The Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018) checklist guided the development of this report.

Definition of Spirituality

A multidisciplinary Delphi panel completed a systematic review of spirituality in serious illness and health and defined spirituality as the process through which people find “ultimate meaning, purpose, transcendence and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred” (Balboni et al., 2022). Accordingly, the panel described spiritual needs, struggles, pain, and distress as being related to an individual’s spirituality and included spiritual concerns and questions. This definition was used to determine the keywords and search terms for the screening and analyses of articles in this scoping review. Because the included studies did not distinguish between the terms spiritual pain, spiritual distress, and spiritual struggles, the term “spiritual distress” is used to describe all three terms.

Data Sources and Searches

Literature searches were completed using four databases, PubMed, PsychINFO, Embase, and CINAHL, to capture all articles published through October 12, 2022. In all databases, search terms based on Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) descriptors combined with the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were:

(care partner OR caregiv* OR carer) AND (spiritual* OR existential OR religio* OR meaning OR transcend* OR sacred) AND parkinson*.

Two authors (KS and MM) completed the database searches and author KS consolidated the results.

Eligibility Criteria

We included full-text articles published in peer-reviewed journals that were written in English and reported on Parkinson’s disease caregivers’ spirituality or spiritual distress as per the definition (e.g., content related to existential questions, meaning-making, transcendence) or used measures to assess caregiver spirituality. We excluded articles that were unrelated to the research questions and did not report on Parkinson’s disease caregivers and/or aspects of spirituality. Additionally, to report on available peer-reviewed evidence we excluded dissertations, conference abstracts, editorials, letters to the editor, and study protocols.

Data Extraction and Categorization

After articles meeting the above inclusion criteria were identified during the initial search, authors KS and MM used a data charting approach for scoping reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) to summarize each remaining abstract’s key elements (e.g., citation, country of origin, aims, design, and results) on a spreadsheet. Author KS reviewed the spreadsheet and excluded abstracts that were unrelated to the research questions, Parkinson’s disease caregivers, and/or did not report on Parkinson’s disease caregivers’ spirituality or spiritual distress as per the definition. The full texts of remaining articles were reviewed by authors KS and SS. Articles of unclear significance were discussed and included in the analysis based on consensus. At this stage, articles were excluded if they did not address the research question (e.g., articles where the abstract referenced Parkinson’s disease caregiver spirituality but the results were reported only for patients, or where the results did not pertain to spirituality). The results of the remaining articles were then categorized based on the four research questions to facilitate a synthesis of results.

Results

Included Studies

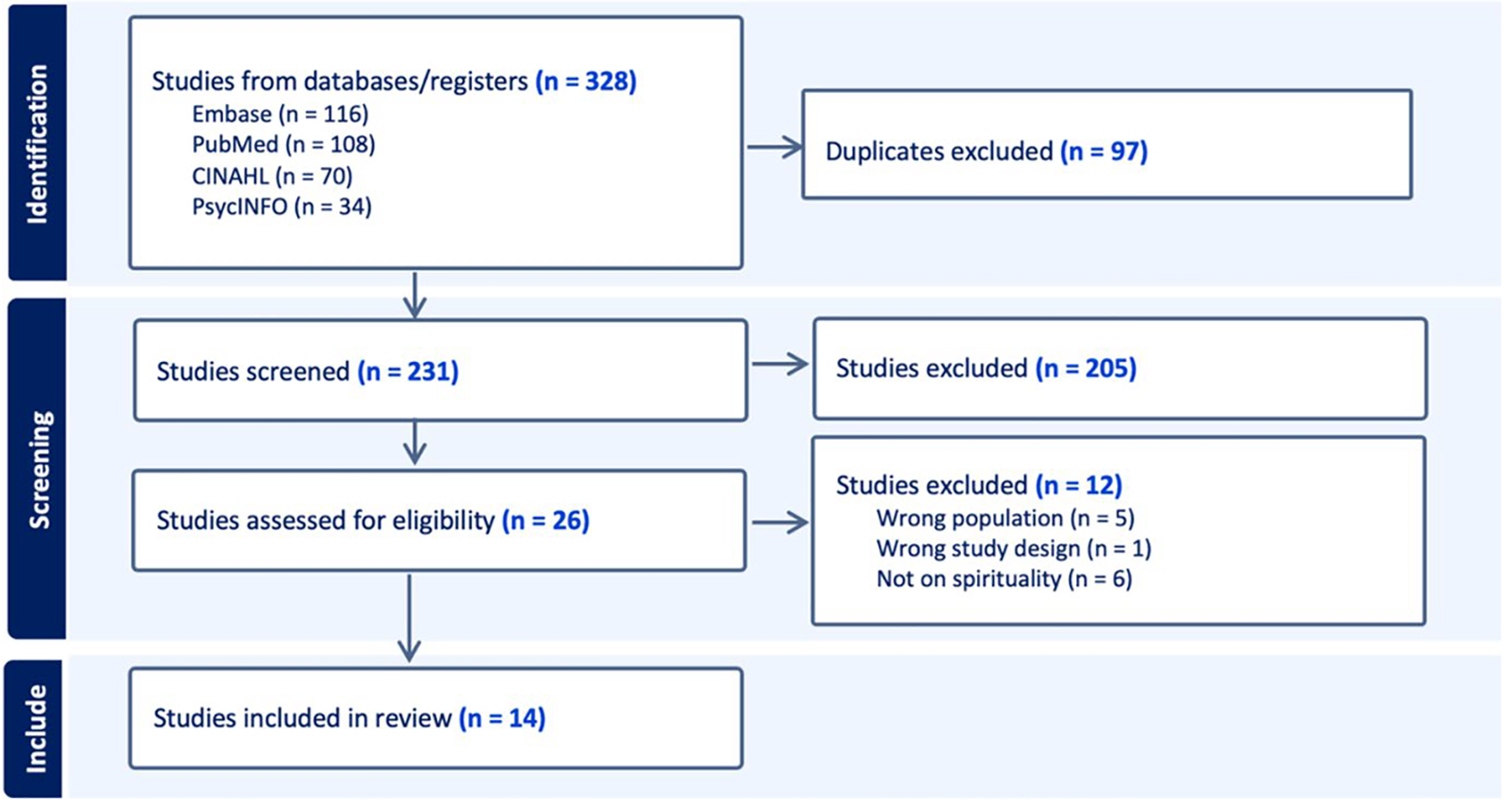

Studies that reported on Parkinson’s disease caregiver spirituality or spiritual distress through October 12, 2022, were extracted, and the initial search yielded 328 studies. After excluding 97 duplicates, the remaining 231 abstracts were screened, and 26 studies met the criteria for full text review. After excluding studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 14 studies were included in the descriptive analyses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart created using covidence, data screening, and extraction tool. (Veritas Health Innovation)

These studies were conducted in Brazil, India, Indonesia, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. The earliest study reporting on Parkinson’s disease caregiver spirituality was published in 2003 and over half of the studies (57%) were published between 2019 and 2022. Participants in the included studies were predominantly older (> 60 years of age) females with an age range of 31–85 years. Participants in studies conducted in the United States were predominantly White. A summary of studies included in this review is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies addressing spirituality among Parkinson’s disease caregivers

| Study | Country | Aims | Sample size | Design/measures | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abendroth, M (2015) | USA | Development and initial validation of the Caregiver Strain Risk Screen (CSRS) | n = 32 informal primary PD caregivers for pilot testing of items n = 217 PD caregivers for psychometric testing | Content validation and psychometric evaluation of Instrument development guided by theoretical conceptualization of caregiver strain risk in PD caregivers | Principal components analysis supported a 28-item instrument with 4 factors: self-preservation, nursing home consideration, coping through spirituality, and coping through formal support. Spirituality was a form of internal support that brought hope to caregivers. CSRS demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability in measuring the construct | |

| Bhasin SK and Bharadwaj IU (2021) | India | To describe the caregiving process of PD family caregivers and understand self identity, existential concerns, and varying demands of the role | n = 10 female PD caregivers (spouses, daughters, daughters-inlaw) | Qualitative Phenomenology research design using narrative | Six themes: (1) Becoming a caregiver; (2) Rising patienthood of one’s family member; (3) Experience of altered temporality; (4) Encountering meaninglessness; (5) Existing as a “Being For” and not a “Being With”; and (6) Self-preservation through brief moments of respite | |

| Bingham V and Habermann B (2006) (Bingham & Habermann, 2006) | USA | To describe whether spirituality assists persons with PD and their families in defining and managing the day-to-day experiences of the disease | Persons with PD and their families (n = 56) recruited from PD support groups in the southeastern US and from a movement disorder clinic | Qualitative study. A content analysis approach was used to interpret and analyze data for emerging themes and patterns of spirituality | The ways persons with PD and their families managed PD were influenced by belief and faith, purpose and meaning, prayer, the support of family and friends, and hope | |

| Bock M, Katz M, Sillau S, et al | USA | To describe the specific items most responsive to a PC intervention in Parkinson’s and Related Disorders (PDRD) and identify key correlates of improvement in patient and caregiver outcomes | Persons with PDRD (n = 210) and their caregivers (n = 175) from three academic medical centers | Nonblinded, randomized, pragmatic comparative effectiveness trial of outpatient integrated PC compared to standard care. Longitudinal regression models were used to analyze changes in subdomains of patient quality of life (QOL) and caregiver burden; Spearman correlations were used to evaluate key correlates of change scores in patient and caregiver outcomes | Positive change in numerous patient non-motor symptoms and grief correlated with improved patient QOL, reduced patient anxiety, and increased caregiver spirituality | |

| Carter JH, Lyons KS, Stewart BJ, Archbold PG, Scobee R | USA | To describe the difference in negative aspects of strain and modulators of strain in young and older PD spouse caregivers | Spouse caregivers of persons with early-stage PD (n = 65 (37 young, 28 old)) recruited through the Parkinson’s Spouse’s Project | A series of hierarchical multiple regressions were used to examine the contribution of age on both positive and negative aspects of the care situation for PD spouse caregivers | Young spouses (40–55) were found to be at greater risk for negative consequences of the care situation reporting significantly more strain from lack of personal resources, and lower levels of mutuality and rewards of meaning than older (>70) spouses | |

| Dekawaty A, Malini H, Fernandes F | Indonesia | To describe family caregiver experiences in caring for persons with PD | Family caregivers of persons with PD (N = 5) | Qualitative study. Data analyzed using the Colaizzi Descriptive Phenomenology approach | Four themes: (1) The ways in which the family members adapt; (2) The impact of the patient’s condition on the caregiver; (3) Support received in providing care; (4) The cultural and spiritual meanings the caregiver obtained when providing care | |

| Koljack CE, Miyasaki J, Prizer LP, et al | USA | To describe predictors of spiritual well-being in caregivers of PD patients | Persons with PD, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, multiple system atrophy, or Lewy body dementia with identified caregivers (n = 175 dyads recruited) | A cross-sectional analysis was performed. Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual well-being (FACIT-Sp) was used to measure caregiver spiritual wellbeing. Other measures used included those to assess patient QOL, symptom burden, global function, grief, and patient spiritual wellbeing, and caregiver mood, burden, and perceptions of patient QOL. Univariate correlation and multiple regression were used to determine associations between predictor variables and Caregiver FACIT-Sp | Patient faith, symptom burden, health-related QOL, depression, motor function, and grief were significant predictors of caregiver spiritual well-being. Predictive caregiver factors included caregiver depression and anxiety. These factors remained significant in combined models, suggesting that both patient and caregiver factors make independent contributions to caregiver spiritual well-being | |

| Konstam V, Holmes W, Wilczenski F, Baliga S, Lester J, Priest R | USA | To describe finding meaning in general and finding meaning specific to caregiving as potentially important explanatory variables in predicting well-being in caregivers of persons with PD | Caregivers of persons with PD (n = 58) | Self-report questionnaires were used to assess wellbeing and meaning (general and specific). Pearson correlation and stepwise regression analysis were used to identify predictors of outcomes for Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist - Revised (MAACL-R) | Significant proportion of the variance of Positive affect and sensation seeking (PASS) and Dysphoria (DYS) related to well-being. Purpose and Existential Vacuum predicted 41.8% of the variance related to PASS and 30.8% of the variance related to DYS respectively. Meaning related specifically to caregiving did not explain any additional variance | |

| Lawson RA, Collerton D, Taylor JP, Burn DJ, Brittain KR | UK | To describe the subjective impact of cognitive impairment on persons with PD and theircaregivers | Persons with PD and their caregivers (n = 36). Persons with PD were from three groups: normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia | Qualitative study. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis. Themes were interpreted in consultation with Coping and Adaptation theory | Four themes: (1) Threats to identity and role; (2) Predeath grief and feelings of loss in caregiver; (3) Success and challenges to coping in persons with PD; (4) Problem-focused coping and finding meaning in caring. For caregivers, cognitive impairment had a greater emotional impact than the physical symptoms of PD | |

| Lopes Nunes SF, Alvarez AM, Alonso da Costa MFBN, Valcarenghi RV | Brazil | To describe the facilitator and inhibitory factors in the transition to the role of caregivers among elderly caregivers of persons with PD | Family caregivers of persons with PD who were enrolled in Association of Parkinson of Santa Catarina (n = 20) | Qualitative study. Based on the Family Transition Nursing Theory developed with elderly caregivers of elderly persons with PD. Used thematic analysis to analyze data | Facilitating factors of transition to the role of caregiver: (1)Previous experiences as caregiver, (2) Spirituality and religiosity, (3) Family support network and health services. Inhibiting factors of transition to the role of caregiver: (1) Emotional and physical health conditions, (2)Advanced age, (3) Personal life commitments, (4) Family financial burden, and (5) Inadequate family support | |

| Macchi ZA, Koljack CE, Miyasaki JM, et al | USA | To describe patient and caregiver predictors of caregiver burden in PD from a palliative care approach | Persons with PDRD (n = 175) and caregivers (n = 175) at three academic medical centers | Cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from PDRD patients and caregivers in a randomized, controlled trial of outpatient palliative care | Univariate models of caregiver characteristics showed significant caregiver predictors of burden. Predictors included meaning and peace subscores of Caregiver FACIT-Sp but not faith. (There was no significant association in the multivariate model.) | |

| Prizer LP, Kluger BM, Sillau S, et al | USA | To describe the association between spirituality and PD management | Persons with PDRD (n = 210) and caregivers (n = 175) at three academic medical centers | Cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from PDRD patients and caregivers in a randomized, controlled trial of outpatient palliative care | Higher patient spirituality was associated with less impairment in quality of life, lower anxiety, lower depression, fewer non-motor symptoms, reduced palliative symptoms, and less prolonged grief. Caregiver spirituality was positively correlated with patient spirituality | |

| Smith LJ, Shaw RL | UK | To describe family members’ lived experience of PD | Persons with PD (n = 4) and CP (n = 5) | Qualitative Study. Interpretative Phenomenological analysis to analyze data | Four themes: (1) It is more than just an illness: existential challenge of diagnosis; (2)Like a bird with a broken wing: need to adapt to increasing immobility; (3)Being together with PD: kinship within couples; and (4)Carpe Diem: significance of time and fractured future orientation created by diagnosis | |

| Trang, Ivan, Katz, Maya, Galifianakis, Nicholas, et al | USA | To describe predictors of general QOL in PDRD patients with high needs and advanced disease, and to compare patient ratings of general QOL to health-related QOL and general patient QOL as reported by caregivers | Persons with PDRD (n = 210) and caregivers (n = 175) at three academic medical centers | Cross-sectional Study. Analyses of baseline data from PDRD patients and caregivers in a randomized, controlled trial of outpatient palliative care conducted from 2015 to 2018 | Caregiver ratings of patient general QOL were associated with patient symptom burden, patient grief, patient global function, caregiver burden, and caregiver spiritual well-being | |

Presentation of Results

Results are presented based on the categories used for synthesis: (1) factors associated with caregiver spirituality and spiritual well-being, (2) spirituality and spiritual distress of caregivers, (3) instruments and measures used to assess caregiver spirituality, and (4) coping strategies for spiritual and existential distress. These data provide a description of the state of current knowledge on spirituality and spiritual distress in Parkinson’s disease caregivers.

Factors Associated with Caregiver Spirituality and Spiritual Well-being

Six studies reported on factors associated with caregiver spirituality and spiritual well-being in Parkinson’s disease and included patient- and caregiver-related factors.

Patient-Related Factors

Factors such as patient faith, symptom burden, motor function, health-related quality of life, depression, and grief were found to be significant predictors of caregiver spiritual well-being (Koljack et al., 2022). Caregivers’ ratings of the patient’s general quality of life were also associated with caregiver spiritual well-being (Trang et al., 2020). Patients’ struggles and suffering gave rise to a sense of meaninglessness and “feelings of betrayal towards God” among caregivers (Bhasin & Bharadwaj, 2021).

Caregiver-Related Factors

Caregiver-related factors included age, depression, anxiety, and caregiver burden. In a study that explored whether age is associated with spouse caregiver strain, three positive variables (e.g., mutuality, preparedness, and rewards of meaning) were assessed (Carter et al., 2010). A sample question for “rewards of meaning” included “Does caring for your spouse add meaning to your life?” Younger caregivers (40 to 55 years old) reported significantly lower rewards of meaning compared to older spouses (≥ 70 years old) (Carter et al., 2010). In another study, finding general meaning as opposed to finding meaning in caregiving was associated with wellbeing (Konstam et al., 2003).

Caregiver depression and anxiety were negatively associated with overall spiritual well-being (Koljack et al., 2022). Depression was correlated with powerlessness and existential vacuum defined as “lack of meaning and direction in life” (Konstam et al., 2003).

Increased caregiver spirituality was correlated with decreased caregiver burden (Bock et al., 2022) and was associated with higher patient quality of life (Bock et al., 2022) and higher patient spirituality (Prizer et al., 2020a). Decreased meaning and peace were significant predictors of increased burden (Macchi et al., 2020).

Spirituality and Spiritual Distress of Caregivers

The spiritual distress experienced by Parkinson’s disease caregivers include loss of meaning, feeling powerless, and difficulty with understanding the reason for suffering. As a result of witnessing patient suffering caregivers experienced an existential vacuum, defined as including “meaninglessness, and unending questions towards the future” (Bhasin & Bharadwaj, 2021, p.6). They also experienced a loss of shared meaning, existential guilt and loneliness (Bhasin & Bharadwaj, 2021). Meaninglessness and powerlessness in the face of uncertainty led to feelings of being “broken” and having to live “the nightmare” (Smith & Shaw, 2017). Some caregivers struggled to understand why a benevolent God would allow such suffering to exist (Bhasin & Bharadwaj, 2021).

Instruments and Measures to Assess Caregiver Spirituality

The most commonly used measure to assess caregiver spirituality was the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-being (FACIT-Sp). This 12-item scale consists of three subscales: sense of meaning, peace, and role of faith in managing serious illness. Other measures included the Finding Meaning through Caregiving Scale (FMTC); Life Attitude Profile-Revised (LAP-R); and the Multiple Affect Adjective Check List-R (MACCL-R). The Caregiver Strain Risk Screen (CSRS) for Parkinson’s disease was the only scale that targeted Parkinson’s disease caregivers. During the initial validation of CSRS for Parkinson’s disease, a factor on coping through spirituality was included that reflected the ability to draw strength from an internal belief system (Abendroth, 2015).

Coping Strategies for Spiritual and Existential Distress

The coping strategies used by Parkinson’s disease caregivers to address their spiritual and existential distress included resignation and acquiescence, cultural beliefs, gratitude, focusing on the positive, and religious beliefs and prayer (Bhasin & Bharadwaj, 2021; Bingham & Habermann, 2006; Dekawaty et al., 2019; Lawson et al., 2018; Nunes et al., 2019).

Female caregivers coped with distress by resigning to their “fate” and accepting their struggles (Bhasin & Bharadwaj, 2021; Dekawaty et al., 2019). This sense of acquiescence, or reluctant or passive acceptance, was predominant in studies conducted in Asian countries where cultural beliefs also provided a way to cope (Bhasin & Bharadwaj, 2021; Dekawaty et al., 2019). These beliefs included (a) caring for the elderly as a way to atone for sins (Dekawaty et al., 2019), and (b) caregiving by daughters, wives, and daughters-in-law as an act of selflessness and devotion (Bhasin & Bharadwaj, 2021).

Positive reframing and gratitude enabled caregivers to cope with their struggles. Caregivers were grateful that their patient’s health was not as bad as others with worse symptoms (Bingham & Habermann, 2006; Dekawaty et al., 2019). Those who found meaning in caregiving experienced personal growth and resilience (Lawson et al., 2018).

Religious beliefs and prayer were dominant coping strategies used by Parkinson’s disease caregivers. Belief and faith in God enabled caregivers to accept (Dekawaty et al., 2019; Nunes et al., 2019) that which was “given by God” (Dekawaty et al., 2019, p.320). Prayers for continued health and strength to handle difficulties (Bingham & Habermann, 2006; Dekawaty et al., 2019) helped caregivers cope as did the belief that God would bless and respond to pleas for help (Bhasin & Bharadwaj, 2021).

Discussion

Spirituality can help patients and caregivers cope with serious medical illnesses and has been increasingly recognized as an essential component of interdisciplinary palliative care (Bock et al., 2022). Among seriously ill patients, 71%–99% view spirituality as important and there is strong evidence for the beneficial association between spirituality and measures of well-being and quality of life (Balboni et al., 2022). Although several studies have explored predictors of spiritual well-being in persons living with Parkinson’s disease (Prizer et al., 2020), less is known about spirituality, spiritual distress, or the spiritual well-being of Parkinson’s disease caregivers. In this scoping review, we summarize the current state of knowledge on spirituality in Parkinson’s disease caregivers based on 14 peer-reviewed publications and provide an evidence-based summary of the (1) factors associated with caregiver spirituality, (2) spiritual distress in Parkinson’s disease caregivers, (3) instruments designed to measure caregiver spirituality, and 4) relevant coping strategies for spiritual and existential distress.

First, spiritual well-being among Parkinson’s disease caregivers is associated with several patient-level factors, including motor and non-motor symptom burden and health-related quality of life (Koljack et al., 2022). Not surprisingly, caregiver perceptions of poor patient quality of life are associated with low levels of caregiver spiritual well-being (Trang et al., 2020). With regard to caregiver-level factors, older caregivers found their caregiving duties more meaningful than younger caregivers (Carter et al., 2010), and increased levels of Parkinson’s disease caregiver spirituality have been linked to reduced caregiver burden (Bock et al., 2022) and improved patient outcomes (Prizer et al., 2020). These data highlight the intricate relationship between patient and caregiver outcomes in Parkinson’s disease. Although patient needs are often prioritized, it is also important for chaplains, spiritual counselors, or other trained healthcare professionals to assess and address the spiritual needs of Parkinson’s disease caregivers in clinical settings.

Parkinson’s disease caregivers also experienced spiritual distress, such as meaninglessness, powerlessness, loneliness, and existential guilt (Bhasin & Bharadwaj, 2021; Smith & Shaw, 2017). Because only two studies reported on Parkinson’s disease caregiver’s spiritual distress, more research is needed to understand their specific spiritual needs. Furthermore, because caregiver spirituality can contribute to caregiver burden and other negative caregiver outcomes, interventions are needed to address these issues.

Importantly, there is a need for a standardized validated tool to assess spirituality and the spiritual needs in Parkinson’s disease caregivers. Although included studies measured caregiver spirituality using one of four instruments, few metrics have been validated in Parkinson’s disease patients or caregivers. The FACIT-Sp, for example, is the most commonly used outcome metric in Parkinson’s disease studies (Prizer et al., 2020, Koljack et al., 2022, Macchi et al., 2020) but was initially designed for persons with cancer (Peterman et al., 2002). In addition, the initial CSRS was a 28-item instrument that included questions on coping through spirituality (Abendroth et al., 2015). Although this instrument was internally validated among 217 Parkinson’s disease caregivers, spirituality was removed during factor analysis, and questions assessing daily joy, thankfulness, faith community, comfort through God, and nonbelief were omitted from the final 10-item instrument (Abendroth, 2016). Thus, additional work is needed to ensure that existing metrics reliably measure the spiritual needs of Parkinson’s disease caregivers.

Lastly, several studies discussed coping strategies for poor spiritual wellbeing among Parkinson’s disease caregivers, which include a combination of religious (e.g., belief in God, prayer) and non-religious (e.g., acceptance, gratitude) approaches. Religious strategies such as praying to a higher power were most commonly used by Parkinson’s disease caregivers and emphasize the importance of individualizing psychosocial support for patients and families based on their religious affiliations and preferences. A few studies reported that Parkinson’s disease caregivers used positive reframing and gratitude as coping strategies. Rewards of caregiving and gratitude are well documented in other diseases (Anderson & White, 2018; Bauer et al., 2013; Doris et al., 2018). Though reduction in suffering has been integral to improving quality of life, there is also a need to enhance the positive aspects of life. A recent framework to support positivity in palliative care includes strategies to assess and promote positive outcomes such as gratitude, contentment, transcendence, and meaning (Kluger & Arnold, 2023) and could be used to enhance spiritual well-being. To this end, Parkinson’s disease teams should establish relationships with and provide referrals to community spiritual providers and serve as advocates for spiritual and religious support throughout the Parkinson’s disease course (Richardson, 2014). Neurologists would benefit from including chaplains and spiritual counselors as core members of their team to address the spiritual needs of patients and caregivers. These professionals have expertise in an array of areas and actively listen, assist with finding purpose, encourage self-care, and explore faith and values (Massey et al., 2015). Chaplains and spiritual counselors have been increasingly integrated into neuropalliative care clinics and often meet separately with patients and caregivers to determine their spiritual needs. They can also meet with patients and care partners together to discuss spiritual intimacy and changes in the spousal relationship following Parkinson’s disease diagnosis, which also contributes to overall well-being.(Holland et al., 2016).

Limitations

The 14 studies included in this scoping review have important limitations, including variable study designs and inconsistent outcome metrics that have not been validated in Parkinson’s disease caregivers. Parkinson’s disease caregiver spirituality and spiritual well-being was the primary aim of only a few studies. The central focus of other studies was caregiver burden, strain, and the caregiving process. In this scoping review we report on studies from only five countries and recognize that there are many geographical and socio-cultural variations that have not been captured and remain unknown. The predominance of female caregivers in the reported studies is consistent with data from epidemiologic studies demonstrating a higher prevalence of Parkinson’s disease among men (Zirra et al., 2023) and hence, more female caregivers. However, it is possible that the spiritual distress experienced by male caregivers may be different from that of female caregivers reported in these studies. In addition, the majority of existing data were obtained from patients and caregivers who receive routine care. Because many patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease no longer attend outpatient neurology visits, the spiritual needs of their caregivers are largely unknown.

Future Directions

Few studies have explored spirituality in Parkinson’s disease caregivers or the relevant contribution of patient-related factors, such as non-motor symptoms, or caregiver-related factors to spiritual distress. Further research is needed to understand the spiritual distress and needs (e.g., making sense of illness or understanding the purpose and meaning of caregiving) and coping strategies (e.g., gratitude, positive reframing) that are most important and helpful to Parkinson’s disease caregivers. Future studies are also needed to validate spirituality outcome measures and develop interventions to address and improve spiritual distress and promote spiritual well-being among Parkinson’s disease caregivers.

Knowledge of specific spiritual needs, coping strategies that matter most to caregivers, and validated spirituality outcome measures will be foundational to providing holistic caregiver support. Further research should determine whether the spiritual distress of Parkinson’s disease caregivers differ from caregivers of patients with other disease processes, such as cancer and end-stage heart failure, which may inform future Parkinson’s disease-specific interventions. Support group interventions for patients and families of those with neurodegenerative illnesses can also enhance meaning making (Paal et al., 2020). Parkinson’s disease clinics can learn from the documented success of interventions to address the spiritual needs of patients and caregivers in other illnesses. Spirituality-based interventions for caregivers of patients with other life-limiting illnesses such as dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, congestive heart failure, and advanced cancer have resulted in a decrease in caregiver burden and improvements in overall enjoyment of life (Bormann et al., 2009). Prior interventions have also provided opportunities for reflection and support (Steinhauser et al., 2016), and meaning-making interventions in patients with cancer are reported to improve self-esteem, optimism, and meaning (Henry et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2006).

Conclusions

Spiritual care is an important component of palliative care for Parkinson’s disease, and it is important that the spiritual needs of both patients and caregivers are addressed with the support of chaplains and spiritual counselors. Because spiritual distress among Parkinson’s disease caregivers contributes to caregiver burden and influences patient outcomes, spirituality is an important topic that requires further study and intervention.

Funding

Author BK received funding related to this work from the National Institute of Aging (K02AG062745). Author MM received funding during Summer 2022 to work on this research study from the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry’s Basic Science, Clinical, and Translational Science Summer Research program. Other authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval This is a Scoping Review of the Literature and hence no ethical approval is required.

References

- Abendroth M (2015). Development and initial validation of a Parkinson’s disease caregiver strain risk screen. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 23(1), 4–21. 10.1891/1061-3749.23.1.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abendroth M (2016). Psychometric testing and modification of the Parkinson’s disease caregiver strain risk screen. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 24(2), 281–295. 10.1891/1061-3749.24.2.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aamodt WW; Kluger BM, Mirham M, Job SE, Mosley PE, & Seshadri S (2023). Caregiver burden in Parkinson disease: A Scoping Review of the Literature from 2017–2022. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 10.1177/08919887231195219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EW, & White KM (2018). “It has changed my life”: An exploration of caregiver experiences in serious illness. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 35(2), 266–274. https://doi: 10.1177/1049909117701895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, & O’Malley L (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balboni TA, VanderWeele TJ, Doan-Soares SD, Long KNG, Ferrell BR, Fitchett G, Koenig HG, Bain PA, Puchalski C, Steinhauser KE, Sulmasy DP, & Koh HK (2022). Spirituality in Serious Illness and Health. Journal of the American Medical Association, 328(2), 184–197. 10.1001/jama.2022.11086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Sterzinger L, Koepke F, & Spiessl H (2013). Rewards of caregiving and coping strategies of caregivers of patients with mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 64(2), 185–188. 10.1176/appi.ps.001212012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benites AC, Rodin G, Leite ACAB, Nascimento LC, & Dos Santos MA 2021). The experience of spirituality in family caregivers of adult and elderly cancer patients receiving palliative care: A meta-synthesis. European Journal of Cancer Care, 30(4), e13424. 10.1111/ecc.13424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhasin SK, & Bharadwaj IU (2021). Perceptions and meanings of living with Parkinson’s disease: An account of caregivers lived experiences. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health & Well-being, 16(1), 1967263. 10.1080/17482631.2021.1967263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham V, & Habermann B (2006). The influence of spirituality on family management of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 38(6), 422–427. 10.1097/01376517-200612000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock M, Katz M, Sillau S, Adjepong K, Yaffe K, Ayele R, Macchi ZA, Pantilat S, Miyasaki JM, & Kluger B (2022). What’s in the sauce? The specific benefits of palliative care for Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management, 63(6), 1031–1040. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann J, Warren KA, Regalbuto L, Glaser D, Kelly A, Schnack J, & Hinton L (2009). A spiritually based caregiver intervention with telephone delivery for family caregivers of veterans with dementia. Family & Community Health, 345–353. 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181b91fd6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JH, Lyons KS, Stewart BJ, Archbold PG, & Scobee R (2010). Does age make a difference in caregiver strain? Comparison of young versus older caregivers in early-stage Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders, 25(6), 724–730. 10.1002/mds.22888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekawaty A, Malini H, & Fernandes F (2019). Family experiences as a caregiver for patients with Parkinson’s disease: A qualitative study. Journal of Research in Nursing, 24(5), 317–327. 10.1177/1744987118816361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Guay MO, Parsons HA, Hui D, Cruz M. G. D. l., Thorney S, & Bruera E (2013). Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain among caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 30(5), 455–461. 10.1177/1049909112458030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doris S, Cheng S-T, & Wang J (2018). Unravelling positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: An integrative review of research literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 79, 1–26. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey ER, Elbaz A, Nichols E, Abd-Allah F, Abdelalim A, Adsuar JC, Ansha MG, Brayne C, Choi JYJ, Collado-Mateo D, Dahodwala N, Do HP, Edessa D, Endres M, Fereshtehnejad SM, Foreman KJ, Gankpe FG, Gupta R, Hankey GJ, Collabora G. P. s. D. (2018). Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurology, 17(11), 939–953. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30295-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Wang Q, Wu Q, Weng Y, Lu H, & Xu J (2022). Spiritual care for the management of Parkinson’s disease: Where we are and how far can we go. Psychogeriatrics, 22(4), 521–529. 10.1111/psyg.12834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaquinto S, Bruti L, Dall’Armi V, Palma E, & Spiridigliozzi C (2011). Religious and spiritual beliefs in outpatients suffering from Parkinson Disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(9), 916–922. 10.1002/gps.2624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry M, Cohen SR, Lee V, Sauthier P, Provencher D, Drouin P, Gauthier P, Gotlieb W, Lau S, & Drummond N (2010). The Meaning-Making intervention (MMi) appears to increase meaning in life in advanced ovarian cancer: A randomized controlled pilot study. Psycho-Oncology, 19(12), 1340–1347. 10.1002/pon.1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanns M (2011). Weathering the storm: Living with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Christian Nursing, 28(2), 76–82. 10.1097/cnj.0b013e31820b8d9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanns M, Deal B, & Haas B (2012). Biopsychosocial and spiritual aspects of Parkinson disease: An integrative review. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 44(4), 194–205. 10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182527593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland KJ, Lee JW, Marshak HH, & Martin LR (2016). Spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and physical/psychological well-being: Spiritual meaning as a mediator. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 8(3), 218. 10.1037/rel0000062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway RG, & Kramer NM (2022). Advancing the neuropalliative care Approach- A call to action. Journal of the American Medical Association Neurology. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.3418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger BM, & Arnold RM (2023). The total enjoyment of life: A framework for exploring and supporting the positive in palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 10.1089/jpm.2023.0321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger BM, Dolhun R, Sumrall M, Hall K, & Okun MS (2021). Palliative care and Parkinson’s disease: Time to move beyond cancer. Movement Disorders. 10.1002/mds.28556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger BM, Hudson P, Hanson LC, Bužgovà R, Creutzfeldt CJ, Gursahani R, Sumrall M, White C, Oliver DJ, & Pantilat SZ (2023). Palliative care to support the needs of adults with neurological disease. The Lancet Neurology, 22(7), 619–631. 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00129-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG (2023). A Response to the Paal et al. Rejoinder: Religiosity and risk of Parkinson’s Disease in England and the USA. Journal of Religion and Health, 62 (2), 10.1007/s10943-022-01734-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koljack CE, Miyasaki J, Prizer LP, Katz M, Galifianakis N, Sillau SH, & Kluger BM (2022). Predictors of spiritual well-being in family caregivers for individuals with Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 25(4), 606–613. 10.1089/jpm.2020.0797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstam V, Holmes W, Wilczenski F, Baliga S, Lester J, & Priest R (2003). Meaning in the lives of caregivers of individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 10(1), 17–25. 10.1023/A:1022849628975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson RA, Collerton D, Taylor J-P, Burn DJ, & Brittain KR (2018). Coping with cognitive impairment in people with Parkinson’s disease and their carers: A qualitative study. Parkinson’s Disease. 10.1155/2018/1362053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V, Cohen SR, Edgar L, Laizner AM, & Gagnon AJ (2006). Meaning-Making intervention during breast or colorectal cancer treatment improves self-esteem, optimism, and self-efficacy. Social Science & Medicine, 62(12), 3133–3145. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macchi ZA, Koljack CE, Miyasaki JM, Katz M, Galifianakis N, Prizer LP, Sillau SH, & Kluger BM (2020). Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease: A palliative care approach. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 9(Suppl 1), S24–S33. 10.21037/apm.2019.10.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, & Forjaz MJ (2012). Quality of life and burden in caregivers for patients with Parkinson’s disease: Concepts, assessment and related factors. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 12(2), 221–230. 10.1586/erp.11.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey K, Barnes MJ, Villines D, Goldstein JD, Pierson ALH, Scherer C, Laan BV, & Summerfelt WT (2015). What do I do? Developing a taxonomy of chaplaincy activities and interventions for spiritual care in intensive care unit palliative care. BMC Palliative Care, 14, 1–8. 10.1186/s12904-015-0008-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosley PE, Moodie R, & Dissanayaka N (2017). Caregiver burden in Parkinson disease: A critical review of recent literature. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry & Neurology, 30(5), 235–252. 10.1177/0891988717720302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, & Aromataris E (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 1–7. 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Worth A, & Benton TF (2004). Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: A prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliative Medicine, 18(1), 39–45. 10.1191/0269216304pm837oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes SFL, Alvarez AM, Costa M. F. B. N. A. d., & Valcarenghi RV (2019). Determining factors in the situational transition of family members who care of elderly people with Parkinson’s disease. Texto & Contexto Enfermagem, 28. 10.1590/1980-265x-tce-2017-0438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otaiku AI (2022). Religiosity and risk of Parkinson’s disease in England and the USA. Journal of Religion and Health, 62 (2), 10.1007/s10943-022-01603-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paal P, Martinez SA, Lorenzl S, & Goldzweig G (2023). A rejoinder to Otaiku: Religiosity and risk of Parkinson’s disease in England and the USA-the health determinants of spirituality, religiosity and the need for state-of-the-art research. Journal of Religion and Health, 62 (2), 10.1007/s10943-022-01726-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paal P, Lex KM, Brandstotter C, Weck C, & Lorenzl S (2020). Spiritual care as an integrated approach to palliative care for patients with neurodegenerative diseases and their caregivers: A literature review. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 9(4), 2303–2313. 10.21037/apm.2020.03.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paal P, & Lorenzl S (2020). Patients with Parkinson’s disease need spiritual care. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 9(2), 144–148. 10.21037/apm.2019.11.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepezko K, Hinkle JT, Forbes EJ, Pontone GM, Mills KA, & Gallo JJ (2023). The impact of caregiving on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 38(1), e5870. 10.1002/gps.5870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, & Cella D (2002). Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-Spiritual well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24(1), 49–58. 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prizer LP, Kluger BM, Sillau S, Katz M, Galifianakis N, & Miyasaki JM (2020a). Correlates of spiritual wellbeing in persons living with Parkinson disease. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 9(Suppl 1), S16–S23. 10.21037/apm.2019.09.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prizer LP, Kluger BM, Sillau S, Katz M, Galifianakis NB, & Miyasaki JM (2020b). The presence of a caregiver is associated with patient outcomes in patients with Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonisms. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 78, 61–65. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, Otis-Green S, Baird P, Bull J, Chochinov H, Handzo G, Nelson-Becker H, Prince-Paul M, Pugliese K, & Sulmasy D (2009). Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 12(10), 885–904. 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchalski CM, Vitillo R, Hull SK, & Reller N (2014). Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(6), 642–656. 10.1089/jpm.2014.9427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafati F, Mashayekhi F, & Dastyar N (2020). Caregiver burden and spiritual well-being in caregivers of hemodialysis patients. Journal of Religion & Health, 59(6), 3084–3096. 10.1007/s10943-019-00939-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern C, & Coles A (2015). Parkinson’s Disease, religion, and spirituality. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice, 2(4), 341–346. 10.1002/mdc3.12206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds D (2017). Spirituality as a coping mechanism for individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Christian Nursing, 34(3), 190–194. 10.1097/CNJ.0000000000000392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson P (2014). Spirituality, religion, and palliative care. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 3(3), 150–159. 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2014.07.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LJ, & Shaw RL (2017). Learning to live with Parkinson’s disease in the family unit: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of well-being. Medicine Health Care & Philosophy, 20(1), 13–21. 10.1007/s11019-016-9716-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser KE, Olsen A, Johnson KS, Sanders LL, Olsen M, Ammarell N, & Grossoehme D (2016). The feasibility and acceptability of a chaplain-led intervention for caregivers of seriously ill patients: A caregiver outlook pilot study. Palliative & Supportive Care, 14(5), 456–467. 10.1017/S1478951515001248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trang I, Katz M, Galifianakis N, Fairclough D, Sillau SH, Miyasaki J, & Kluger BM (2020). Predictors of general and health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders including caregiver perspectives. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 77, 5–10. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MD, Horsley T, & Weeks L (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varon B, Gurin I, & Mandel S (2022). Is there a place for spirituality in Neurology? [Special Report]. Practical Neurology, 69–73. https://practicalneurology.com/articles/2022-sept/is-there-a-place-for-spirituality-in-neurology [Google Scholar]

- Weaver AJ, & Flannelly KJ (2004). The role of religion/spirituality for cancer patients and their caregivers. Southern Medical Journal, 97(12), 1210–1214. 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146492.27650.1C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirra A, Rao SC, Bestwick J, Rajalingam R, Marras C, Blauwendraat C, Mata IF, & Noyce AJ (2023). Gender differences in the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice, 10(1), 86–93. 10.1002/mdc3.13584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]