Abstract

As potential autocrine or paracrine factors, extracellular nucleotides are known to be important regulators of renal ion transporters by activating cell surface receptors and intracellular signaling pathways. We investigated the influence of extracellular adenine nucleotides on Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) activity in A6-NHE3 cells. This is a polarized cell line obtained by stable transfection of A6 cells with the cDNA encoding the rat isoform of NHE3, which is expressed on the apical membrane. Basolateral addition of the P2Y1 agonist, 2-Me-SADP, induced an inhibition of NHE3 activity, which was prevented by preincubation with selective P2Y1 antagonists, MRS 2179 (N6-methyl-2′-deoxyadenosine-3′,5′-bisphosphate) and MRS 2286 (2-[2-(2-chloro-6-methylamino-purin-9-yl)-ethyl]-propane-1,3-bisoxy(diammoniumphosphate)). NHE3 activity was also significantly inhibited by ATP and ATP-γ-S but not by UTP. 2-MeSADP induced a P2Y1 antagonist-sensitive increase in both [Ca2+]i and cAMP production. Pre-incubation with a PHC inhibitor, Calphostin C, or the calcium chelator BAPTA-AM, had no effect on the 2-MeSADP-dependent inhibition of NHE3 activity, whereas this inhibition was reversed by either incubation with the PKA inhibitor H89 or by mutation of two PKA target serines (S552 and S605) on NHE3. Pre-incubation of the A6-NHE3 cells with the synthetic peptide, Ht31, which prevents the binding between AKAPs and the regulatory PKA subunits RII, also prevented the 2-Me-SADP-induced inhibition of NHE3. We conclude that only the cAMP/PKA pathway is involved in the inhibition of NHE3 activity.

Keywords: P2Y receptors, A6 cells, Na+/H+ exchanger, ATP

Introduction

Mammalian systemic fluid volume is determined primarily by the balance between sodium absorption and renal excretion. Nucleotides, as a potential autocrine and/or paracrine factor, can modulate ion transport and fluid secretion by controlling several renal cell processes via interaction with specific membrane receptors (Chan et al., 1998). The P2 purinoceptors are divided into either ligand-gated cation channels (P2X) or G-protein-coupled receptors (P2Y) (Abbracchio & Burnstock 1994; Barnard, Burnstock & Webb, 1994). The P2Y receptors have been shown to function via two major signal transduction pathways: their stimulation can increase intracellular calcium concentration by stimulating phospholipase activity (Dubyak & El-Moatassim, 1993) and can either increase (Cote, Van Sande & Boeynaems, 1993; Post et al., 1998) or diminish (Dalziel & Westfall 1994; Harden, Boyer & Nicholas, 1995) cAMP production, depending on the tissue or cell type examined. Subtypes of P2Y receptors have been found in the kidney of different species (Yamada et al., 1996; Bouyer et al., 1998; Bailey et al., 2000). The use of renal epithelial cell models derived from different segments of the nephron such as MDCK (Simmons 1981; Post et al., 1998), A6 (Middleton et al., 1993; Nilius et al., 1995; Banderali et al., 1999), and mIMCD-H2 cells (McCoy et al., 1999; Boese et al., 2000) have provided useful models in which to study the cellular mechanisms by which the P2Y receptors regulate ion transport.

In the renal proximal tubule, the bulk of sodium absorption and as much as 50% of absorption are mediated by apical Na+/H+-exchange activity encoded by NHE3 (Amemiya et al., 1995; Biemesderfer et al., 1997) and fine tuning of its activity plays an important role in systemic salt and fluid homeostasis. While a number of hormones have been shown to modulate Na+ reabsorption through their regulation of the NHE3, the knowledge of the role of nucleotides in regulating NHE3 is still very limited. Considering the importance of apical NHE3 in renal Na+ and absorption, it is of interest to determine the role of P2-receptor activation in NHE3 activity.

To this end we used A6/C1 cells ( a distal nephron epithelial cell line derived from Xenopus laevis) heterologously transfected with wild-type rat NHE3. These cells, besides having an endogenous, basolateral XNHE, express the transfected NHE3 on the apical membrane that is inhibited by pharmacological activation of PKA and PHC (Di Sole et al., 1999). That study also demonstrated that adenosine inhibited the NHE3 activity via both the basolateral PKA-coupled A2A adenosine receptor and the apical PHC-coupled A1 receptor. In this study we provide evidence that in A6-NHE3 cell monolayers 2-MeSADP activates both signaling pathways, namely, an increase in intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP formation, but that only the cAMP cascade is involved in the 2-MeSADP-induced inhibition of the transepithelial Na+ absorption by NHE3.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

A6/C1 cells used for transfection are a subclone of A6–2F3 cells, functionally selected on the basis of high transepithelial resistance and responsiveness to aldosterone (Verrey, 1994). A6-NHE3 cells (subclone 6s) are A6/C1 cells stably expressing full-length rat NHE3 (Di Sole et al., 1999). A6/C1 cell lines were grown in 0.8× concentrated DMEM (Life Technologies, Gibco), containing 25 mm NaHCO3, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (ICN Biomedicals), 50 I.U./ml penicillin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin and 450 µg/ml hygromycin-B (final osmolarity: 220–250 mosmol/kg). Cells were incubated in a humidified 95% air-5% CO2 atmosphere at 28°C and subcultured weekly by trypsinization using a Ca2+-Mg2+-free salt solution containing 0.25% (w/v) trypsin and 2 mm EGTA. Cells generally reached confluency between 7 to 8 days after seeding when the culture medium was changed three times a week. Studies on A6/C1 cell lines were performed between passages 24 and 34.

NHE3 cDNA Constructs and Cell Transfection

The cDNAs subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector and encoding mutated forms of NHE3 containing a single substitution of an endogenous serine residue, with alanine in either position 552 or 605 of the amino-acid sequence of NHE3, were kindly provided by Dr. O.W. Moe (Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas). To allow experimental flexibility, both NHE3 constructs contained a C-terminal 6His tag. The functional properties of 6 His-tagged NHE3 constructs were indistinguishable from those of untagged NHE3 (Di Sole et al., 2001).

For transfection, cells were grown to 20–25% confluence in 35-mm tissue culture dishes. DNA was introduced into cells plated on culture dishes using FuGENE™ 6 (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) as recommended by the manufacturer, using 1.5 µg of the construct of interest together with 0.5 µg of the p3′SS∆LacI vector, which allowed us to select transfected cells on the basis of their resistance to hygromycin B (for details of the p3′SS∆LacI construct, see Di Sole et al., 1999). Clonal populations of transfected cell lines (obtained by ring cloning) were maintained in culture as described above and continuously exposed to hygromycin-B (450 µg/ml culture medium) during growth in order to maintain selection pressure. Cells used for experiments were routinely exposed for a 6- to 7- day time period to 1 µm dexamethasone known to accelerate maturation and differentiation (Preston et al., 1988). As determined in separate experiments (Di Sole et al., 2001), A6-NHE3 cells containing mutant forms of NHE3 were insensitive to cAMP-induced inactivation of apical NHE3 activity compared to A6/C1 cells expressing wild-type NHE3.

Intracellular pH Measurements

Intracellular pH (pHi) was examined in single A6 cells within a confluent monolayer by microspectrofluorometry as described previously (Montrose et al., 1987). Cells on collagen-coated Teflon filters (Millicell CM, 0.4 µm pore size; Millipore) were loaded with the acetoxymethyl derivative of BCECF (10 µm) for 60 min at room temperature. Cells on filters were then inserted into a chamber that allowed independent superfusion of the apical and basolateral compartments, as previously detailed (Montrose et al., 1987). Sequential excitation of the dye was carried out using band-pass filters 390–440 nm and 475–490 nm in front of a xenon lamp. The resultant fluorescent emissions (515–565) were corrected for cellular autofluorescence. During pHi measurements, cells were continuously perfused at a flow rate of 1 ml/min and data points were recorded at 6-sec intervals. Calibration of the BCECF excitation ratio was carried out with nigericin and isotonic KCl as described (Montrose & Murer, 1990).

Na+/H+ exchange activity was investigated by monitoring pHi recovery after an acid load by using the NH4Cl prepulse technique (Boron & DeWeer 1978). The rate of Na+-dependent alkalization was determined by linear regression analysis of 15 points taken at 4-sec intervals. A similar number of data points was collected in all recoveries examined. The use of nominally -free solutions minimized the likelihood that Na+-dependent transport was responsible for the observed pHi changes. Because the Na+-dependent pHi recovery was initiated always at a similar pHi, a change in ∆pHi/min following 2-MeSADP addition is expected to be most likely a consequence of 2-MeSADP-induced alterations of the transport process itself and not a consequence of different cellular acid loads (allosteric control of Na+/H+ exchange). Where it was possible, experiments were performed in the same monolayer such that control pHi recovery was performed first and then always compared to the pHi recovery after the treatment (see Fig. 1). This permitted the use of two-tailed, paired Student’s t-test analysis of the data.

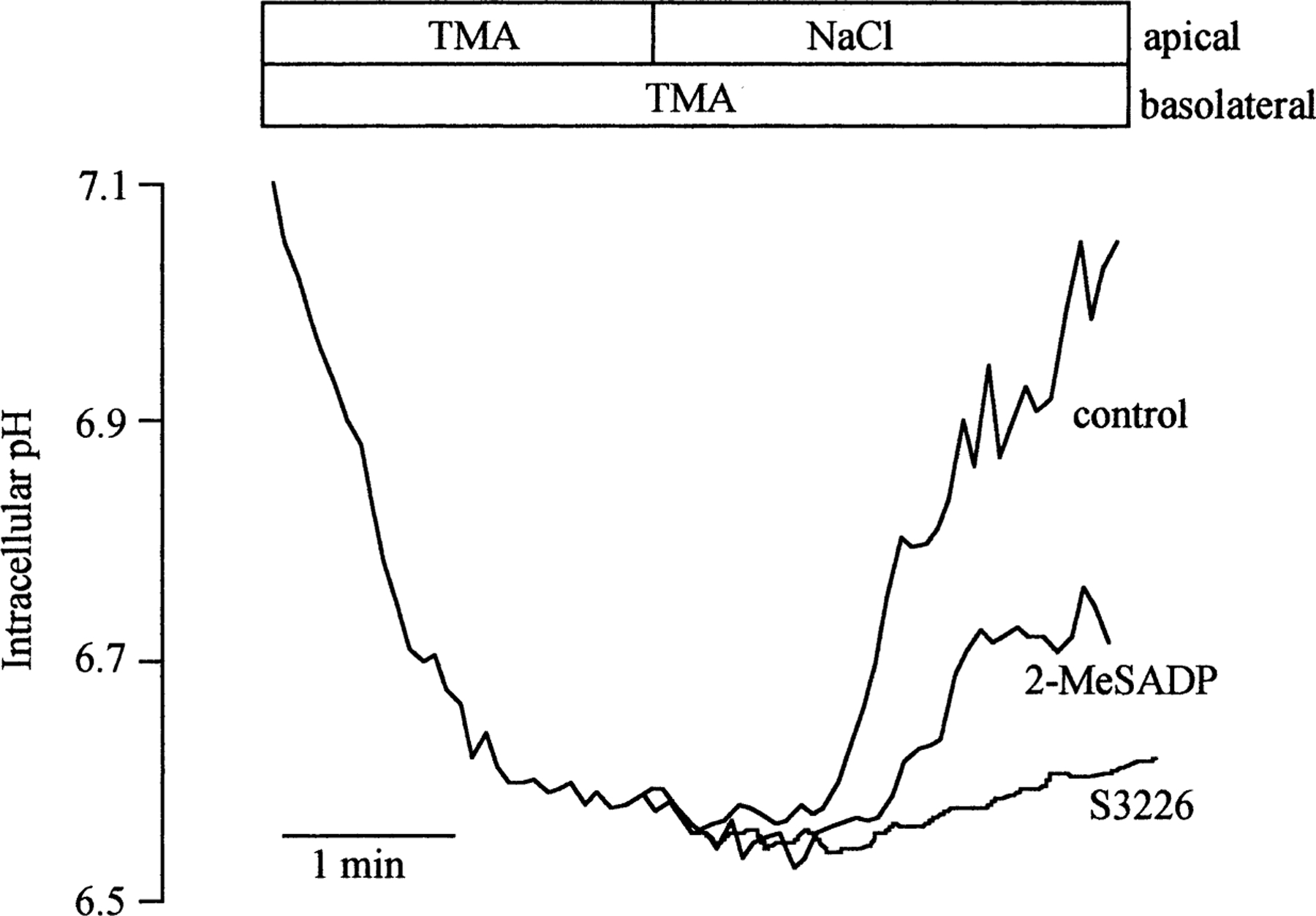

Fig. 1.

Representative traces depicting the effect of 2-MeSADP on NHE3 exchange activity in A6-NHE3 monolayers. NHE3 activity was assayed as the initial rate of apical Na+-dependent pHi recovery after intracellular acidification via superfusion with medium followed by Na+-free tetramethylammonium (TMA) Ringer before (control) and after 10 minutes of pre-incubation with either 10 nm 2-MeSADP or 10 µm of the NHE3-specific inhibitor, S3326 (see Methods). The ordinate is the pHi corresponding to the nigericin calibration performed as described in Methods.

All pHi measurements were performed at room temperature in HEPES-buffered media. Sodium medium contained (in mm) 110 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 0.5 MgSO4, HH2PO4, 5 glucose and 10 HEPES buffered with Tris to a final pH of 7.5. For cellular acidification we used a NH4Cl-solution identical to Na+ Ringer, plus 40 mm NH4Cl in addition. A sodium-free (TMA Ringer) was obtained by complete replacement of sodium with tetramethylammonium.

Measurements of [Ca2+]i

Cells were seeded at low density on glass coverslips and used the following day for microspectrofluorimetric measurements of cytoplasmic [Ca2+] with the dye Fura-2-AM as described previously (Reshkin et al., 2000). In the experiments in which we analyzed the polarity of the P2Y receptor localization, cells were seeded on collagen-coated polyethylene terephthalate (PET) cell membranes. Cells were loaded in tissue-culture medium with Fura-2-AM (5 µm) in the incubator for 45 min. Coverslips with dye-loaded cells were mounted into a chamber placed on the stage of an inverted microscope (Zeiss IM 35) and perfused at 25°C using a gravity-driven system at a rate of 1.5–2 ml/min. Emitted fluorescence from a single cell was measured in response to alternate pulses of excitation light (5 msec duration) at 340 nm and 380 nm using a computer-controlled four-place sliding filter holder manufactured in-house. The emitted fluorescence (510 nm) was focused on a photomultiplier tube, amplified digitally, converted and sampled on an IBM-compatible computer. All measurements were automatically corrected for background. The ratio of emitted light from the two excitation wavelengths (340/380) of Fura-2 provided a measure of cytoplasmic [Ca2+]i. The composition of the Ringer solution used in these experiments was (in mm): NaCl 101.4, MgSO4 0.5, Cacl2 1.4, KCl 5.4, NaHCO3 8, NaH2PO4 0.9, HEPES 1, glucose 5, (pH = 7.5). In the calcium-free Ringer, 1 µm EGTA was added.

Cyclic AMP Determination

Cells were plated in 12-well microculture plates and grown until reaching approximately 70% confluency. Prior to treatment of cells, growth medium was removed and cells were equilibrated for 30 min in Ringer. Unless otherwise indicated, the incubations with agonists were conducted for 10 min at 28°C in presence of the phosphodiesterase inhibitors 10 µm Rolipram plus 1 mm IBMX. The incubation medium was stopped and the cells were washed twice with a Ringer solution and 0.25 ml of a 5% trichloroacetic acid solution was added in order to extract cAMP. The subsequent steps were carried out as described by Gilman and Murad (1974). Intracellular cAMP was then determined using the cAMP [3H] assay system (Amersham TRH 432).

Data Presentation

Results are presented as mean ± se. Significant statistical differences between each group of measurements were taken as P<0.05, tested by one-way ANOVA or by paired Student’s t-test for data obtained on the same monolayer.

Materials

Fura-2-AM, BAPTA-AM, Forskolin, H-89, were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). 2-MeSADP, ATP-γ-S and UTP were purchased from Sigma RBI (Milan, Italy); Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) filters for cell culture were from Becton Dickinson Labware (USA). Teflon Millicell-CM filters were from Millipore (Eschborn, Germany). P2Y1 antagonists (MRS 2179 and MRS 2286) were synthesized as reported (Camaioni et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2000).

Results

2-MeSADP Effect on the NHE3 Activity

To determine whether extracellular nucleotides regulate NHE3 activity, we first analyzed the effect of the potent P2Y1 synthetic agonist, 2-MeSADP, in A6-NHE3 cell monolayers. We obtained the A6-NHE3 cells transfected with wild type NHE3 (rat isoform) (Di Sole et al., 1999). When grown on permeable filters, these cells display a polarized expression of the two Na+/H+ exchangers: the endogenous Na+/H+ exchanger (XNHE) on the basolateral membrane and the NHE3 isoform of the Na+/H+ exchanger on the apical membrane (Di Sole et al., 1999). That the apical pHi recovery in A6-NHE3 is due mainly to NHE3 activity is supported by two observations. First, the specific inhibitor of NHE3, S3226 (Schwark et al., 1998), strongly decreases only the apical pHi recovery (see Fig. 1). Second, the apical NHE3 is inhibited by PKA activation with Forskolin (−44.61 ± 3.18%, n = 13), while the endogenous, basolateral XNHE is stimulated by PKA activation with Forskolin (+30.24 ± 4.68%, n = 4) (Guerra et al., 1993; Di Sole et al., 1999).

Figure 1 shows a typical experiment in which the A6-NHE3 cell monolayers were acidified by NH4Cl prepulse, and the recovery was monitored in the presence of apical Na+ Ringer before and after the addition of 10 nm 2-MeSADP to the basolateral side of the monolayer. As can be seen, 10 nm 2-MeSADP significantly decreased the apical NHE3 activity (0.351 ± 0.026 vs. 0.227 ± 0.022ΔpHi/min; −32.60 ± 5.48%, n = 6, P<0.01). At 100 nm, the 2-MeSADP-dependent NHE3 inhibition was slightly higher than the inhibition observed at 10 nm (0.317 ± 0.024 vs. 0.198 ± 0.021 ∆pHi/min; n = 12, −39.41 ± 3.13%, P<0.001), while at 1 µm, the level of the inhibition was diminished but still significant (−26.09 ± 3.11%, n = 6, P<0.01). It is important to note that the 2-MeSADP effect on pHi recovery was completely reversible (data not shown). When added apically, 100 nm 2-MeSADP had no effect on the NHE3 activity (0.392 ± 0.055 vs. 0.365 ± 0.069 ∆pHi/min, n = 4, N.S.), suggesting that this P2Y receptor is basolateral.

Interestingly, the endogenous, basolateral XNHE was stimulated by basolateral 2-MeSADP pre-incubation (0.400 ± 0.033 vs. 0.490 ± 0.035 ∆pHi/min, +22.5 ± 6.3%, n = 4, P<0.02), underlining the different regulation of the two Na+/H+ exchangers.

We then tested the effect of other nucleotides on NHE3 activity: ATP, ATP-γ-S and UTP at 100 nm and 1 µm. ATP significantly inhibited NHE3 activity at both the concentrations tested (−25.89 ± 1.59, n = 3, P<0.01 and −24.03 ± 2.19%, n = 3, P<0.001 at 100 nm and 1 µm ATP, respectively). ATP-γ-S at 100 nm inhibited the NHE3 activity slightly but significantly (0.333 ± 0.021 vs. 0.255 ± 0.016 ∆pHi/min; n = 8; −21.65 ± 5.06%, P<0.01), while at 1 µm the inhibition was not significant (0.359 ± 0.032 vs. 0.346 ± 0.033 ∆pHi/min; n = 4; −3.9 ± 1.8%, N.S). Finally, UTP did not significantly affect NHE3 activity either at 100 nm or 1 µm.

To determine if the inhibitory action of basolateral 2-MeSADP was via a receptor-mediated mechanism, we examined the effect of the pre-treatment of the basolateral side of the monolayer with the selective P2Y1 antagonists MRS 2179 (Camaioni et al., 1998) and the more specific MRS 2286 (Brown et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2000). As shown in Fig. 2, both antagonists reversed the inhibitory action of 100 nm 2-MeSADP. However, they had no effect on the basal NHE3 activity (data not shown). These results suggest that the 2-MeSADP-dependent inhibition of the apical NHE3 occurred through P2Y1-like receptors localized on the basolateral membrane.

Fig. 2.

Effect of the P2Y1-selective antagonists MRS 2179 and MRS 2286 on 2-MeSADP-mediated inhibition of the NHE3. The P2Y1-selective antagonist MRS 2179 (1 µm) or MRS 2286 (1 µm) was added to the basolateral side of the monolayer 5 min before stimulation with 2-MeSADP (100 nm). Data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA test; ** indicates significant difference (P<0.01) compared to the control value.

We have previously shown in A6 monolayers that A2A adenosine receptors are also located on the basolateral surface (Casavola et al., 1996). Therefore, to verify that the inhibition induced by basolateral 2-MeSADP was not partially mediated by A2A adenosine receptors, we also tested the effect of the A2A-antagonist, CSC (1 µm), on the 2-MeSADP-dependent inhibition of NHE3. We found that CSC pretreatment had no effect on the inhibitory action of 2-MeSADP (0.297 ± 0.047 vs. 0.195 ± 0.037 ∆pHi/min; −36.43 ± 5.45%, n = 3, P<0.02), demonstrating that 2-MeSADP does not inhibit NHE3 via stimulation of A2A receptors.

2-MeSADP Effects on cAMP Production

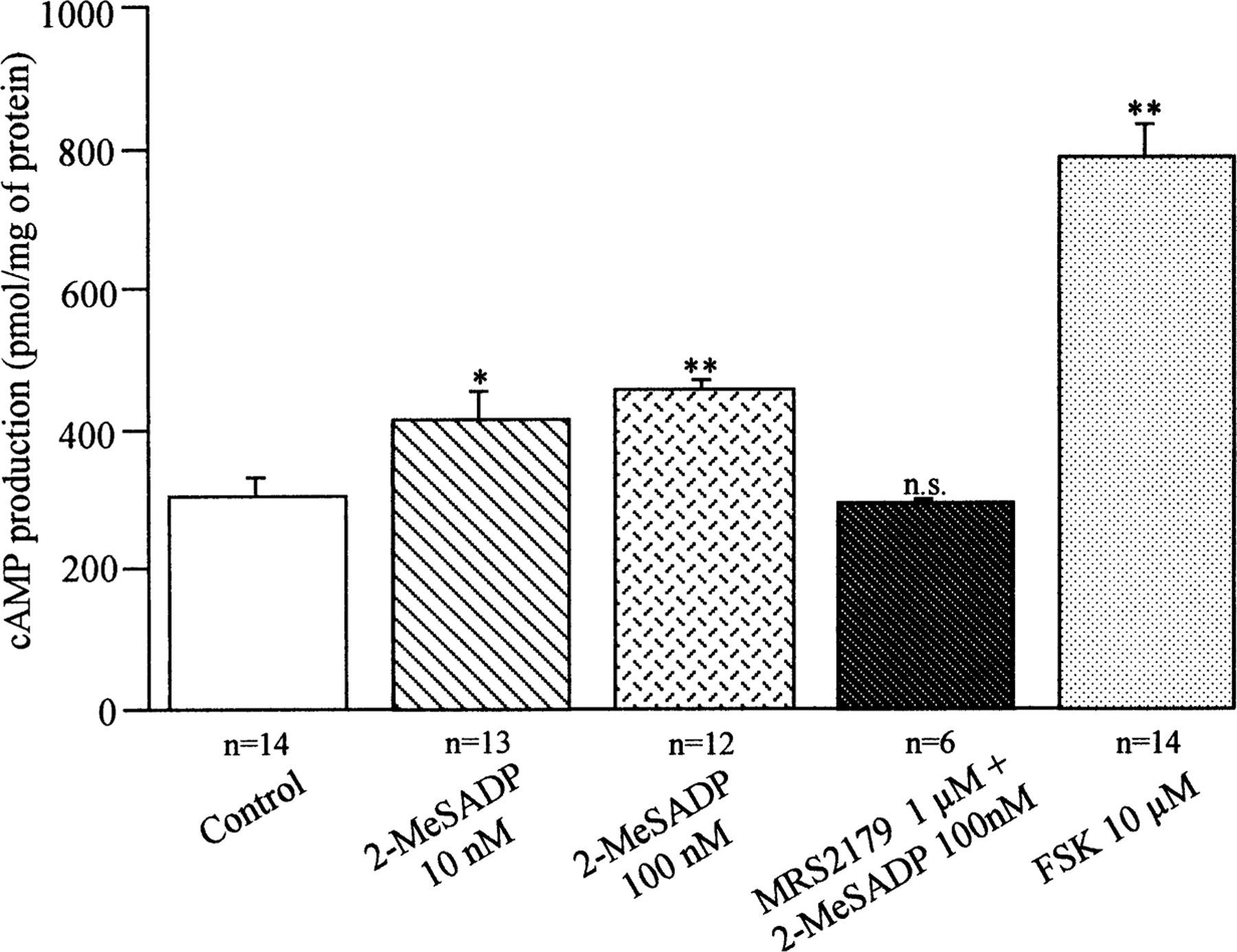

The 2-MeSADP-dependent inhibition of apical NHE3 and stimulation of basolateral XNHE suggests that it may exert its action through a cAMP/PKA-dependent mechanism. We then determined intracellular cAMP accumulation to decipher directly the involvement of adenyl cyclase in the action of 2-MeSADP. From the experiments shown in Fig. 3, it is evident that the level of cAMP rose already (P<0.05) at 10 nm 2-MeSADP and slightly but significantly more at 100 nm MeSADP (P<0.01). The P2Y1 antagonist, MRS 2179 (1 µm), while having no effect on basal cAMP levels (data not shown), prevented the 2-MeSADP-induced increase of cAMP levels. In a parallel series of experiments, we analyzed the effect of simultaneous addition of 2-MeSADP (100 nm) with a low Forskolin concentration (0.3 µm), and we found a synergistic effect of 2-MeSADP and Forskolin on stimulating cAMP production. Data pooled across 3 experiments were, in percentage of cAMP increase: FSK (0.3 µm), 46.67 ± 4.70%; 2-MeSADP, 39.97 ± 2.52 and FSK plus 2-MeSADP, 63.70 ± 1.46. All together, these data suggest that 2-MeSADP-mediated increase in cAMP production involves Gs α.

Fig. 3.

Effect of 2-MeSADP and the P2Y1 antagonist MRS 2179 on cAMP production. The level of intracellular cAMP in A6-NHE3 cells was measured after cells were incubated for 10 min with the indicated 2-MeSADP concentrations or a pre-incubation with 1 µm MRS 2179 for 5 min before the addition of 100 nm 2-Me-SADP. Incubation with Forskolin (FSK) was used as a positive control. Data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA test; ** (P<0.01), * (P<0.05) indicate significant difference compared to the value for control cAMP production.

2-MeSADP Effects on Calcium Concentration

To determine the mechanisms underlying 2-Me-SADP-dependent alterations in cytosolic calcium levels, measurements of calcium were obtained microspectrofluorometrically in single cells as outlined in Methods. 2-MeSADP (10 nm) induced an increase in calcium level that corresponded to a mean increase in the ∆-fluorescence ratio of 0.63 ± 0.049 in 31 independent experiments (∆F = Fmax-effect after the agonist treatment — F resting condition). 2-MeSADP at concentrations 10- and 100-fold higher, respectively, induced almost the same increase in the ∆fluorescence (∆F = 0.615±0.087, at 100 nm, n = 5 and 0.50 ± 0.07 at 1 µm, n = 4). Importantly, in the absence of extracellular calcium (nominal calcium-free medium plus 10−6 m EGTA), 2-MeSADP still transiently increased intracellular calcium, (∆F = 0.37 ± 0.033, n = 5) indicating that 2-MeSADP, as in other cellular systems, releases Ca2+ from intracellular stores. It is of interest to note that measurements of intracellular calcium in A6-NHE3 cells seeded on permeable support indicate that 2-Me-SADP induces the increase of calcium only when added on the basolateral side of the monolayer (∆F = 0.48 ± 0.030, n = 5).

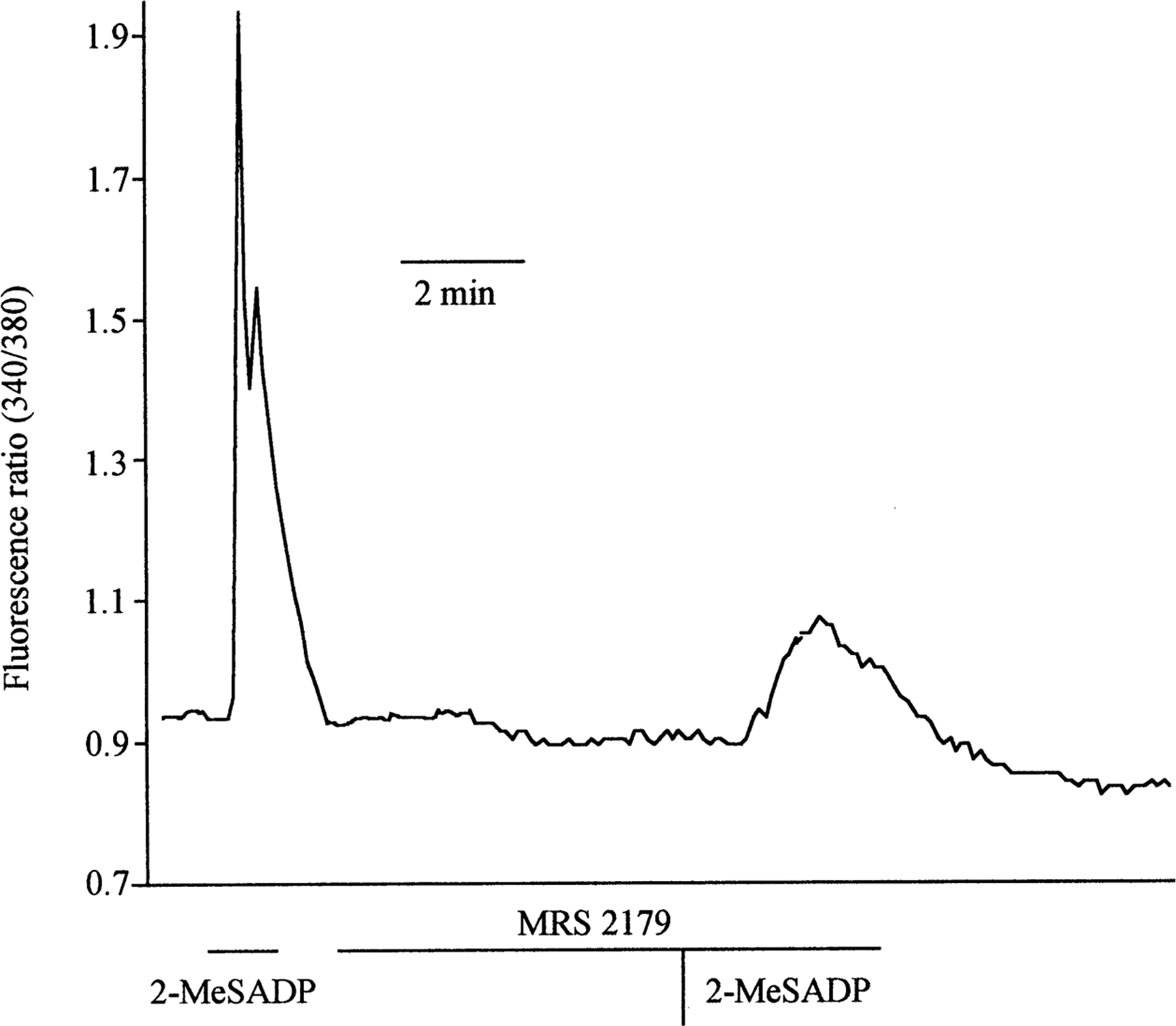

As seen in Fig. 4, a short pre-incubation (~5 min) with the specific P2Y1 receptor antagonist MRS 2179 (1 µm) significantly inhibited the calcium response induced by 100 nm 2-MeSADP (0.72 ± 0.13 vs. 0.17 ± 0.05, n = 4; −72.86 ± 7.94%, P<0.02 in absence and presence of MRS2179, respectively). In a parallel series of experiments we also tested the effect of 1 µm MRS 2286, another selective antagonist of the P2Y1 receptor, on the 2-MeSADP-dependent calcium response and found that also in this case the 2-Me-SADP-dependent increase was significantly inhibited (0.51 ± 0.08 vs. 0.13 ± 0.05, −79.33 ± 7.18% n = 6, P<0.001).

Fig. 4.

Representative trace showing 2-Me-SADP-dependent cytosolic calcium increase (fluorescence ratio): effect of the P2Y1 antagonist, MRS 2179. Cells were continuously perfused with Ringer solutions. At indicated times, cells were perfused with Ringer containing 100 nm 2-MeSADP, Ringer containing 1 µm MRS 2179 or both.

To determine whether G proteins were involved in this 2-MeSADP-dependent calcium release, we analyzed the calcium response to 2-MeSADP in the presence of the poorly hydrolyzable GDP analogue, GDPβs. A 2-hour pre-incubation with GDPβs (500 µm) completely prevented the calcium increase induced by 10 nm 2-MeSADP (−93.21 ± 2.33%, n = 5), indicating the involvement of G proteins in this effect.

We then tested the possibility whether UTP, GTP or ATP-γ-S induced a change in cellular cytoplasmic calcium levels and found that within a concentration range of 10 nm to 1 µm neither UTP nor GTP significantly affected cytoplasmic calcium levels. ATP-γ-S, however, at a concentration of 1 µm, induced an increase in calcium level that corresponded to a mean increase in the ∆F ratio of 0.58 ± 0.10, n = 4.

Signal Transduction Mechanisms Involved in 2-MeSADP-dependent Inhibition of NHE3

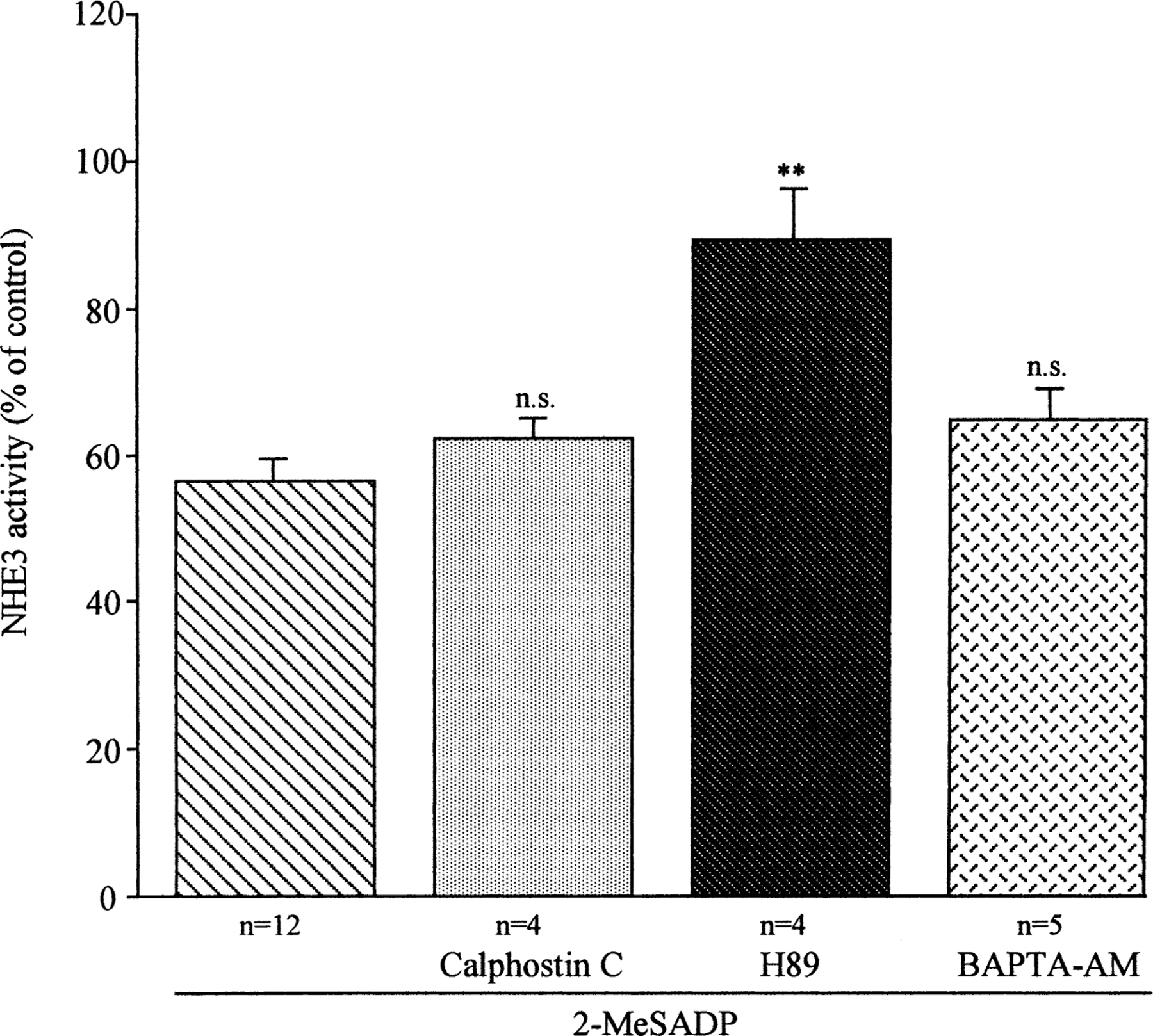

Since the data reported above support the notion that the effect of 2-MeSADP on the NHE3 activity could be mediated via a PHC and/or PKA pathway, we next analyzed the effect of pharmacological activation of the PKA and PHC pathways on NHE3 activity. As previously reported (Di Sole et al., 1999), both TPA (100 nm) and FSK (10 µm) inhibited the NHE3 activity (−36.87 ± 5.02, n = 4, and −44.61 ± 3.18%, n = 13, for TPA and FSK, respectively) and these effects were comparable to the inhibition induced by 10 nm 2-MeSADP. Therefore, to distinguish the involvement of PKA or PHC in the transduction of the 2-MeSADP signal to NHE3, we analyzed the effect of selective inhibitors of PKA (H89) and PHC (Calphostin C). Moreover, in another series of experiments to test whether the increase of calcium induced by 2-MeSADP could directly or indirectly regulate the apical NHE3 activity, we treated the cell monolayers with the intracellular calcium chelator, 5, 5’-dimethyl BAPTA-AM for 1 hour prior to 2-MeSADP addition. As shown in Fig. 5, only pre-incubation with H89 completely prevented 2-MeSADP-mediated inhibition of NHE3 activity. Calphostin C, on the other hand, did not alter significantly the 2-MeSADP-dependent inhibition. Pre-treatment with BAPTA-AM, while completely abrogating the intracellular calcium increase (data not shown), had no effect on the inhibitory action of 2-MeSADP. All together, these data suggest that it is the cAMP/PKA pathway that transduces the 2-MeSADP-dependent regulation of NHE3 independently of 2-MeSADP-induction of intracellular calcium and PHC. None of these treatments had any effect on the basal NHE3 activity (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Effect of the pharmacological activation/inhibition of several regulatory pathways on 2-MeSADP-dependent regulation of NHE3 activity. Measurements of initial rate of pHi recovery, induced by superfusion of Na+ medium to acid-loaded cells first in the absence (control) and then in the presence of the indicated agents, were performed as described in Fig. 1. Cell monolayers were exposed to 100 nm basolateral 2-MeSADP minus or plus indicated agents at both the apical and basolateral side at the following concentrations: Calphostin C (10 nm), H89 (1 µm), and BAPTA-AM (20 µm). Values were analyzed with one-way ANOVA test; ** indicates significant difference (P<0.01) compared to the average of pHi recovery in presence of only 2-MeSADP.

Since Post (1998) demonstrated that ATP in MDCK increases cAMP via an indomethacin-sensitive pathway, we pre-treated A6-NHE3 monolayers with indomethacin (10 µm), a cyclooxygenase inhibitor, to determine if the increase of cAMP levels is dependent on prostaglandin formation. We found that a 15-min pre-incubation of indomethacin did not prevent the 2-MeSADP-induced inhibition on NHE3 activity (0.263 ± 0.010 vs. 0.176 ± 0.008 ∆pHi/min, −31.72 ± 1.19% P<0.001, n = 3), supporting the notion that 2-MeSADP-dependent inhibition of NHE3 occurred via an indomethacin-independent pathway.

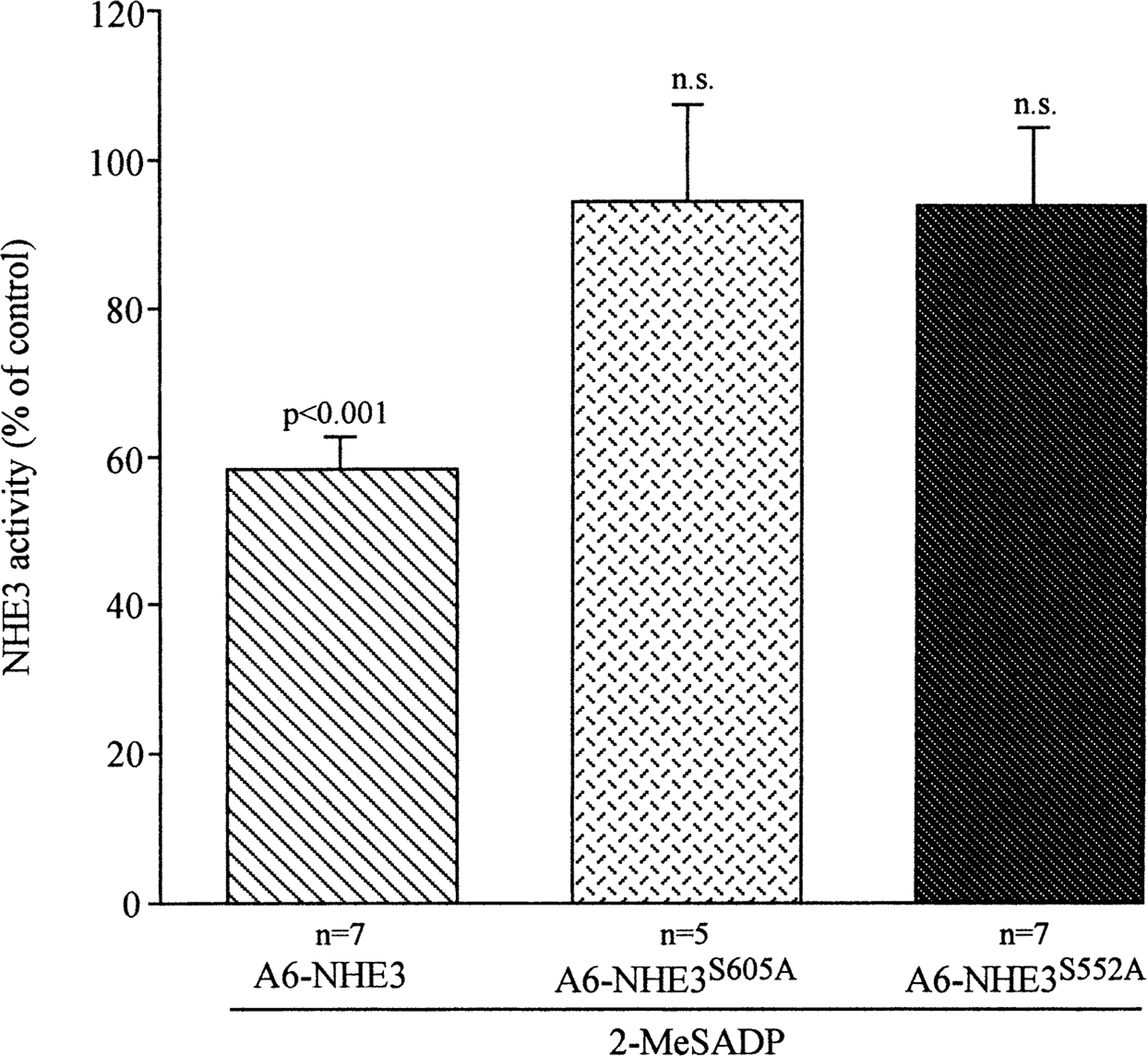

These data suggest that basolateral 2-MeSADP binding to its P2Y receptor inhibited Na+/H+ exchange via the adenylate cyclase/PKA pathway. To obtain additional proof that 2-MeSADP inhibits NHE3 activity by a cAMP/PKA dependent mechanism, we analyzed the effect of 2-MeSADP (100 nm) on NHE3 activity in A6 cells transfected with the mutant NHE3, in which the serines 552 or 605 were mutated to alanines (Di Sole et al., 2001). Previous studies, in fact, have demonstrated that these two serines are PKA phosphorylation substrates in rat NHE3 and are necessary for its PKA-dependent regulation (Zhao et al., 1999). As shown in Fig. 6, we found that both the Ser552 and Ser605 mutations completely reversed the 2-MeSADP inhibitory effect on NHE3 activity.

Fig. 6.

Effect of the mutation of PKA substrate serines 552 and 605 to alanine on 2-MeSADP-dependent regulation of NHE3 activity. Measurements of the initial rate of pHi recovery induced by superfusion of Na+ medium of acid-loaded cells were performed first in the absence (control) and then in presence of 100 nm basolateral 2-MeSADP, as described in Fig. 1. Measurements were conducted in A6 cells transfected with either wild-type NHE3 (A6-NHE3), NHE3 with serine 605 mutated to alanine (A6-NHE3S605A) or NHE3 with serine 552 mutated to alanine (A6-NHE3S552A). Values are means ± se of the indicated number of experiments and analyzed by Student’s t-test for paired data of pHi recoveries in the same monolayer before and after 2-MeSADP (100 nm) treatment.

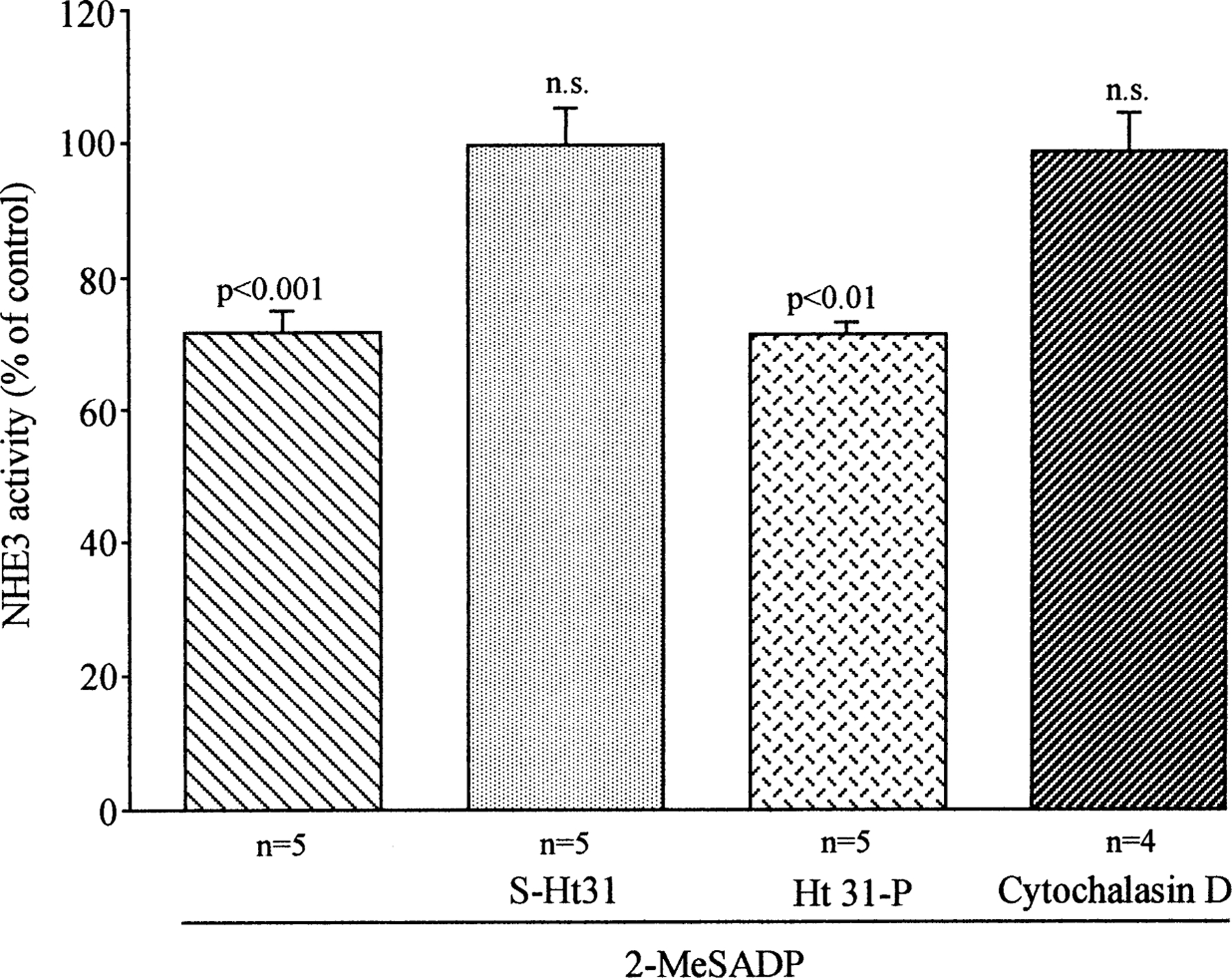

Recent work has demonstrated that A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) play a fundamental role in governing the cellular compartmentalization of subpopulations of PKA in order to localize it in proximity of the target substrate. This appears to be due to the binding of the regulatory PKA subunits RII to the AKAPs at a specific amino-acid consensus sequence that can be blocked by the synthetic peptide S-Ht31 (as reviewed by Colledge & Scott, 1999). As shown in Fig. 7, 60 min of pre-incubation with the membrane-permeable peptide, S-Ht31 coupled to stearate residues, completely prevented the inhibitory effect of 2-MeSADP on NHE3 activity, but was not effective on the basal NHE3 activity. In contrast, pre-incubation with the inactive control peptide Ht31-P, containing prolines at positions 502 and 507 (Hlussmann et al., 1999), failed to prevent the action of 2-MeSADP. These results support the hypothesis that the targeting of PKA to subcellular compartments via AKAPs is necessary for 2-MeSADP inhibitory action on NHE3 activity.

Fig. 7.

Effect of pre-incubation with the synthetic peptide S-Ht31, its inactive control, Ht31-P, or cytochalasin D on 2-MeSADP-dependent regulation of NHE3 activity. In the experiments in which the effect of S-Ht31 was analyzed, the A6-NHE3 monolayers were pre-incubated for one hour with either the active peptide, S-Ht31 (100 µm) or with the inactive form, Ht31-P (100 µm). Afterwards, the effect of 2-MeSADP (100 nm) on NHE3 activity was analyzed as above. For cytochalasin D, after measuring the pHi recovery in control conditions (without 2-Me-SADP), the same monolayers were incubated for 30 min with 2 µm cytochalasin D, and recovery in the presence of 2-MeSADP (100 nm) was measured. Each column represents the mean ± SE of the indicated number of experiments as analyzed with Student’s t-test for paired data in comparison with untreated, control cells.

Members of the cytoskeleton-associated ERM family (ezrin, radixin, moesin) have been identified as AKAPs (Dransfield et al., 1997). Ezrin, besides being an RII-binding protein, is known to bind to both NHERF, a protein involved in regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger (Weinman et al., 1995) and filamentous actin. Therefore, it is interesting to note that 30 min of pre-incubation with 2 µm cytochalasin D, known to induce depolymerization of actin filaments, did not influence significantly the basal NHE3 activity (0.232 ± 0.044 vs. 0.200 ± 0.042, n = 3, N.S.) but prevented the inhibitory action of 2-MeSADP (Fig. 7). These observations imply that 2-MeSADP action on NHE3 activity requires an intact cytoskel etal organization. However, more details functional analysis and morphological studies are necessary to clarify the precise mechanism underlying this action.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to determine the role of ATP in regulating NHE3 activity in a model of renal polarized cells. The NHE3 isoform is regulated by a variety of hormones because of its fundamental role in renal Na+ and HCO3− absorption but, until now, few studies have determined the cellular mechanism by which P2Y receptor activation influences NHE3 activity.

We have used A6-NHE3-cell monolayers as a model to study the mechanism of P2Y action on NHE3 activity for a number og reasons. Firstyl, in A6-cells the presence of P2Y receptors has been demonstrated by different laboratories (Nilius et al., 1995; Mori et al., 1996; Banderali et al., 1999). In addition, when transfected into A6 cells, the rat NHE3 has the same pattern of response to PKA and PHC activation as has been shown in the proximal tubule (Di Sole et al., 1999), and these A6-NHE3 cells form a polarized monolayer with high transepithelial resistance, which exibits an amiloride-sensitive sodium transport and a chloride secretion mediated by CFTR (Bagorda et al., 2002).

The results of the present study demonstrate that 2-MeSADP caused a consistent inhibition of NHE3 activity only when added on the basolateral side of a confluent and tight monolayer (1300 ± 190 Ω × cm2, n = 10). The inhibitory effect of 2-MeSADP was maximal at 100 nm (~40%) and was almost completely reversed by the pretreatment with either MRS 2179, which was demonstrated to be a competitive antagonist at turkey and human P2Y1 receptors (Camaioni et al., 1998) or MRS 2286, which was demonstrated to be an antagonist at turkey P2Y1 receptors (Kim et al., 2000).

P2Y receptors have been shown to function via two signal transduction pathways: their stimulation can increase intracellular calcium concentration by stimulating phospholipase C activity (Dubyak and El-Moatassim, 1993) and can either increase (Cote et al., 1993; Henning et al., 1993; Post et al., 1998) or diminish (Dalziel & Westfall, 1994; Harden et al., 1995) cAMP production, depending on the tissue or cell type examined. We observed that, in A6-NHE3 cells, 2-MeSADP was able to stimulate cAMP production and an intracellular calcium increase at the same concentration (100 nm) at which it inhibited NHE3 activity. The 2-MeSADP-dependent stimulation of both second messengers was inhibited by pretreatment with P2Y1-specific antagonists. We therefore examined the possibility that 2-MeSADP-dependent regulation of NHE3 activity could be transduced either by the cAMP/PKA or the Ca2+/PHC pathway or both.

Several strategies were employed to demonstrate that the 2-MeSADP inhibitory action on NHE3 activity is mediated by a cAMP/PKA-dependent mechanism: 1) We showed that 2-MeSADP was able to induce a small but significant increase in cAMP levels and that it acts synergistically with submaximal forskolin stimulation. 2) The 2-MeSADP-dependent inhibition of NHE3 activity was completely reversed by H89, a specific PKA inhibitor. In contrast, neither the PHC inhibitor calphostin C nor the intracellular calcium chelator, BAPTA-AM, prevented the 2-Me-SADP effect. Thus, it could be concluded that the calcium increase subsequent to 2-MeSADP stimulation is not responsible for the NHE3 inhibition. Furthermore, we can also exclude the possibility that the calcium increase stimulates adenylate cyclase by interacting with calmodulin, leading to activation of PHC, as has been observed in other cellular systems (Fagan et al., 1996). 3) Mutation of either of the PKA phosphorylation target serines, Ser552 or Ser605, to alanine (Zhao et al., 1999) abrogated the 2-MeSADP-dependent inhibition of NHE3 activity. 4) Incubation with S-Ht31, a peptide that blocks the interaction of PKA with A-kinase - anchoring proteins (AKAPs) (Lester, Langeberg & Scott, 1997, Hlussmann et al. 1999), but not the inactive peptide, Ht31-P, blocked the 2-MeSADP-dependent inhibition of NHE3 activity.

This last result, together with the observations that pre-incubation with cytocalasin D, a fungal metabolite that disturbs F-actin polymerization, prevented the inhibitory action of 2-MeSADP, suggests that also in our cell model, as it has been demonstrated recently in PS120 (Weinman, Minkoff & Shenolikar, 2000), the regulation of NHE3 by PKA could require the formation of a multiprotein complex. Studies on protein-protein interaction in OH cells (Lamprecht, Weinman & Yun, 1998) and in A6-NHE3 cells (Bagorda et al., 2002) have shown that NHERF (NHE regulatory factor) binds to both NHE3 and ezrin. Ezrin interacts with filamentous actin and has been shown to directly bind to PKA (Dransfield et al., 1997). Therefore, the binding of NHERF to ezrin could represent a link between NHE3 and PKA, functioning to localize PKA in the vicinity of the cytoplasmic domain of NHE3 (Yun et al., 1998).

Previous studies in A6 cells have indicated that ATP and UTP stimulate chloride efflux by interacting with P2Y2-like receptors (Banderali et al., 1999). Because in the A6-NHE3 cells UTP was unable to regulate NHE3 activity, while both ATP and ATP-γ-S inhibited its activity, our idea is that P2Y2 receptor activation is not involved in NHE3 regulation by 2-MeSADP. Inside the P2Y family, the P2Y1 and P2Y11 receptors are specifically activated by adenine nucleotides (Communi et al., 1997) and, in the present study, a number of different lines of evidence are consistent with the hypothesis that the 2-MeSADP effect on NHE3 activity could be mediated through a P2Y1 -and/or P2Y11-like receptor. The P2Y11 subtype is, in fact, the only one having the property of activating both the phosphoinositide and the cAMP pathways (Communi, Robaye & Boeynaems, 1999; Zambon et al., 2001).

In conclusion, we demonstrated that purinoceptor activation induces an inhibition of sodium reabsorption mediated by NHE3, by a cAMP/PKA-induced mechanism. It is known that in cystic fibrosis (CF) tissues chloride secretion is lacking while there is sodium hyperabsorption, and that purinergic agonists are able to successfully correct chloride-secretion defects in various CF cells (Schwiebert & Hishore, 2001). Where expressed, NHE3 represents one of the major sodium reabsorption mechanisms and, in this context, the reduction of sodium absorption via NHE3 by purinergic agonist stimulation could represent a useful tool to relieve sodium hyperabsorption.

Acknowledgments

We thank Teresa Fanelli for technical assistance. We also thank Dr. E. Klussmann of the Research Institute for Molecular Pharmacology, Berlin Free University, for the kind gift of the S-Ht31 and Ht31-P peptides. The research was funded by Telethon-Italy (Grant n. E. 1125).

Abbreviations:

- ATP-γ-S

Adenosine 5′-O-(3-Thiotriphosphate) tetralithium

- 2-MeSADP

2-Methylthioadenosine diphosphate trisodium

- CSC

8-(3-Chlorostyryl)caffeine

- MRS 2179

N6-methyl-2′-deoxyadenosine 3′, 5′-bisphosphate

- MRS 2286

2-[2-(2-Chloro-6-methylamino-purin-9-yl)-ethyl]-propane-1,3 bisoxy(diammoniumphosphate)

- S3226

{3-[2-(3-guanidino-2-methyl-3-oxo-propenyl)-5-methyl-phenyl]-N-isopropylidene-2-methyl-acrylamide dihydrochloride}

- TPA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

References

- Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G 1994. Purinoceptors: are there families of P2X and P2Y purinoceptors? Pharmacol. Ther 64:445–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amemiya M, LoAng J, Lötscher M, Haissling B, Alpern RJ, Moe OW 1995. Expression of NHE3 in the apical membrane of rat renal proximal tubule and thick ascending limb. Kidney Intern 48:1206–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagorda A, Guerra L, Di Sole F, Helmle-Holb C, Cardone RA, Fanelli T, Reshkin SJ, Gisler SM, Murer H, Casavola V 2002. Reciprocal PKA regulatory interactions between CFTR and NHE3 in a renal polarized epithelial cell model. J. Biol. Chem 277:21480–21488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banderali U, Brochiero E, Lindenthal S, Raschi C, Bogliolo S, Ehrenfeld J 1999. Control of apical membrane chloride permeability in the renal A6 cell line by nucleotides. J. Physiol 519:737–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard EA, Burnstock G, Webb TE 1994. G protein-coupled receptors for ATP and other nucleotides: a new receptor family. Trends Physiol. Sci 15:67–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MA, Imbert-Teboul M, Turner C, Marsy S, Sral H, Burnstock G, Unwin RJ 2000. Axial distribution and characterization of basolateral P2Y receptors along the rat renal tubule. Kidney Intern 58:1893–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biemesderfer D, Rutherford PA, Nagy T, Pizzonia JH, Abu-Alfa AH, Aronson PS 1997. Monoclonal antibodies for high resolution localization of NHE3 in adult and neonatal rat kidney. Am. J. Physiol 273:F289–F299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boese SH, Glanville M, Aziz O, Gray MA, Simmons NL 2000. Calcium and cAMP-activated chloride conductances mediate chloride secretion in a mouse renal inner medullary collecting duct cell line. J. Physiol 523:325–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boron WF, DeWeer P 1978. Intracellular pH transients in squid giant axons caused by CO2, NH3 and metabolic inhibitors. J. Gen. Physiol 67:91–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer P, Paulais M, Cougnon M, Hulin P, Anagnostopoulos T, Planelles G 1998. Extracellular ATP raises intracellular calcium and activates basolateral chloride conductance in Necturus proximal tubule. J. Physiol 510:535–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SG, Hing BF, Him YC, Burnstock G, Jacobson HA 2000. Activity of novel adenine nucleotide derivatives as agonists and antagonists at recombinant rat P2X receptors. Drug Devel. Res 49:253–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camaioni E, Boyer JL, Mohanram A, Harden TH, Jacobson HA 1998. Deoxyadenosine-bisphosphate derivatives as potent antagonists at P2Y1 receptors. J. Med. Chem 41:183–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casavola V, Guerra L, Reshkin SJ, Jacobson HA, Verrey F, Murer H 1996. Effect of adenosine on Na+- and Cl−-currents in A6 monolayers. Receptor localization and messenger involvement. J. Membrane Biol 151:237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CM, Unwin RJ, Burnstock G 1998. Potential functional roles of extracellular ATP in kidney and urinary tract. Exp. Nephrol 6:200–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colledge M, Scott JD 1999. AKAPs: from structure to function. Cell Biology 9:216–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Communi D, Govaerts C, Parmentier M, Boeynaems JM 1997. Cloning of a human purinergic P2Y receptor coupled to phospholipase C and adenylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem 272:31969–31973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Communi D, Robaye B, Boeynaems JM 1999. Pharmacological characterization of the human P2Y11 receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol 126:1199–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote S, Van Sande J, Boeynaems JM 1993. Enhancement of endothelial cAMP accumulation by adenine nucleotides: role of methylxanthine-sensitive sites. Am. J. Physiol 264:H1498–H1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalziel HH, Westfall DP 1994. Receptors for adenine nucleotides: subclassification, distribution, and molecular characterization. Pharmacol. Rev 46:449–466 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Sole F, Cerull R, Moe OW, Burckdardt G, Helmle-Holb C 2001. Molecular mechanism of NHE3 inactivation by A1 and A2 adenosine receptor activation in A6 renal epithelial cells. FASEB J 15:A144 [Google Scholar]

- Di Sole F, Casavola V, Mastroberardino L, Verrey F, Moe OW, Burckhardt G, Murer H, Helmle-Holb C 1999. Adenosine inhibits thr tranfected Na-H exchanger NHE3 in Xenopus laevis renal epithelial cells (A6/C1). J. Physiol 515: 829–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dransfield DT, Bradford AJ, Smith J, Martin M, Roy C, Mangeat PH, Goldering JR 1997. Ezrin is a cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase anchoring protein. EMBO J 16:35–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubyak GR, El-Moatassim C 1993. Signal transduction via P2-purinergic receptors for extracellular ATP and other nucleotides. Am. J. Physiol 265:C577–C606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan HA, Mahey R, Cooper MF 1996. Functional co-localization of tranfected Ca2+-stimulatable adenylyl cyclases with capacitive Ca2+ entry sites. J. Biol. Chem 271:12438–12444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman AG, Murad F 1974. Assay of cyclic nucleotides by receptor protein binding displacement. Methods Enzymol 38:49–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra L, Casavola V, Vilella S, Verrey F, Hemle-Holb C, Murer H 1993. Vasopressin dependent control of basolateral Na/H exchange in highly differentiated A6-cell monolayers. J. Membrane Biol 135:209–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden TH, Boyer JL, Nicholas RA 1995. P2 purinoceptors: subtype-associated signaling responses and structure. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 35:541–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning RH, Duin M, den Hertog A, Nelemans A 1993. Characterization of P2-purinoceptor-mediated cAMP formation in mouse C2C12 myotubes. Br. J. Pharmacol 110:133–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Him Y, Rodriguez C, Jang S, Nandanan E, Adams M, Harden TH, Boyer JL, Jacobson HA 2000. Acyclic analogues of deoxyadenosine 3’,5’-bisphosphates as P2Y1 receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem 43:746–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlussmann E, Maric H, Wiesner B, Beyermann M, Rosenthal W 1999. Protein kinase A anchoring proteins are required for vasopressin-mediated translocation of aquaporin-2 into cell membranes of renal principal cells. J. Biol. Chem 274:4934–4938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamprecht G, Weinman EJ, Yun CHC 1998. The role of NHERF and E3HARP in the cAMP-mediated inhibition of NHE3. J. Biol. Chem 273:29972–29978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester LB, Langeberg LH, Scott JD 1997. Anchoring of protein kinase A facilitates hormone-mediated insulin secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14942–14947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy DE, Taylor AL, Hudlow BA, Harlson H, Slattery MJ, Schwiebert LM, Schwiebert EM, Stanton B 1999. Nucleotides regulate NaCl transport in mIMCD-H2 cells via P2X and P2Y purinergic receptors. Am. J. Physiol 277:F552–F559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton JP, Mangen AW, Basavappa S, Fitz G 1993. Nucleotide receptors regulate membrane ion transport in renal epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol 264:F867–F873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montrose MH, Friedrich T, Murer H 1987. Measurements of intracellular pH in single LLC-PH1 cells: Recovery from an acid load via basolsteral Na+/H+ exchange. J. Membrane Biol 97:63–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montrose MH, Murer H 1990. Regulation of intracellular pH by cultured opossum kidney cells. Am. J. Physiol 259:C110–C120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M, Nishizaki T, Hawahara H, Okada Y 1996. ATP-activated cation conductance in a Xenopus renal epithelial cell line. J. Physiol 491:281–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Sehrer J, Henke S, Droogmans G 1995. Ca2+ release and activation of K+ and Cl currents by extracellular ATP in distal nephron epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol 38:C376–C384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post SR, Rump LC, Zambon A, Hughes RJ, Buda MD, Jacobson JP, Hao CC, Insel PA 1998. ATP activates cAMP production via multiple purinergic receptors in MDCK-D1 epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem 273:23093–23097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston AS, Muller J, Handler JS 1988. Dexamethasone accelerates differentation of A6 epithelia and increases response to vasopressin. Am. J. Physiol 255:C661–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reshkin SJ, Guerra L, Bagorda A, Debellis L, Cardone R, Li AH, Jacobson HA, Casavola V 2000. Activation of A3 adenosine receptor induces calcium entry and chloride secretion in A6 cells. J. Membrane Biol 178:103–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwark JR, Jansen HW, Lang HJ, Hrick W, Burckhardt G, Hropot M 1998. S3226, a novel inhibitor of Na+/H+ exchanger subtype 3 in various cell types. Pfluegers Arch.-Eur. J. Physiol 436:797–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwiebert EM, Hishore BH 2001. Extracellular nucleotide signaling along the renal epithelium. Am. J. Physiol 280:F945–F963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons NL 1981. Identification of a purine (P2) linked to ion transport in a cultured renal (MDCK) epithelium. Br. J. Pharmacol 73:379–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrey F 1994. Antidiuretic hormone action in A6 cells. Effect on apical Cl− and Na+ conductances and synergism with aldosterone for NaCl reabsorption. J. Membrane Biol 138:65–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinman EJ, Steplock D, Wang Y, Shenolikar S 1995. Characterization of a protein cofactor that mediates protein kinase A regulation of the renal brush border membranes. J. Clin. Invest 95:2143–2149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinman EJ, Minkoff C, Shenolikar S 2000. Signal complex regulation of renal transport proteins: NHERF and regulation of NHE3 by PKA. Am. J. Physiol 279:F393–F399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Seki G, Taniguchi S, Uwatoko S, Suzuki H, Hurokawa H 1996. Mechanism of [Ca2+]i increase by extracellular ATP in isolated rabbit renal proximal tubules. Am. J. Physiol 270:C1096–C1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun CHC, Lamprecht G, Forster DV, Sidor A 1998. NHE3 kinase A regulatory protein E3HARP binds the epithelial brush border Na/H exchanger NHE3 and the cytoskeletal protein ezrin. J. Biol. Chem 273:25856–25863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambon AC, Bruton LL, Barrett HE, Hughes RJ, Torres RJ, Insel PA 2001. Cloning, expression, signaling mechanisms, and membrane targeting of P2Y(11) receptors in Madin Darby canine kidney cells. Mol. Pharmacol 60:26–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Wiederkehr R, Fan L, Collazo RL, Crowder LA, Moe OW 1999. Acute inhibition of Na/H exchanger NHE3 by cAMP. Role of protein kinase A and NHE-3 phosphoserines 552 and 605. J. Biol. Chem 274:3978–3987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]