Abstract

Therapeutic vaccination has the potential to boost immune responses and enhance viral control during chronic infections. However, many therapeutic vaccination approaches have fallen short of expectations, and effective boosting of antiviral T-cell responses is not always observed. To examine these issues, we studied the impact of therapeutic vaccination, using a murine model of chronic infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). Our results demonstrate that therapeutic vaccination using a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the LCMV GP33 CD8 T-cell epitope can be effective at accelerating viral control. However, mice with lower viral loads at the time of vaccination responded better to therapeutic vaccination than did those with high viral loads. Also, the proliferative potential of GP33-specific CD8 T cells from chronically infected mice was substantially lower than that of GP33-specific memory CD8 T cells from mice with immunity to LCMV, suggesting that poor T-cell expansion may be an important reason for suboptimal responses to therapeutic vaccination. Thus, our results highlight the potential positive effects of therapeutic vaccination on viral control during chronic infection but also provide evidence that a high viral load at the time of vaccination and the low proliferative potential of responding T cells are likely to limit the effectiveness of therapeutic vaccination.

The development of effective strategies to control chronic infections is an area of considerable current interest. While significant efforts are focused on developing preventive vaccines, there also exists a great need to develop strategies to boost immune responses and viral control in individuals who are already infected. Effective therapeutic vaccination would offer an attractive method of boosting immune responses and enhancing viral control during chronic viral infections. For example, during human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, potent CD8 T-cell responses are associated with an initial drop in viremia, and in some cases, with long-term control of viral replication (3, 25, 29). Therapeutic interventions that boost these T-cell responses and lower the viral load may not only improve disease-free survival but also decrease transmission of the virus. Furthermore, the principles of effective therapeutic vaccination may apply not only to chronic viral infections but also to persisting bacterial and parasitic infections and cancer. Thus, it is important to evaluate how to elicit the most successful immune responses following therapeutic intervention during chronic infection.

Several studies have examined the potential benefits of therapeutic vaccination during a variety of persistent infections (6, 9, 15, 18, 20, 22, 24, 28, 30, 31, 38, 40). On one hand, some reports have demonstrated enhanced immune responses following therapeutic vaccination. For example, the therapeutic vaccination of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques with poxvirus-expressed SIV antigens elicited significant T-cell responses when coupled with antiretroviral therapy, and this approach resulted in a more effective control of viremia when drug therapy was ceased (15, 38). In addition, promising results have been reported for the use of whole-SIV-loaded dendritic cells to boost immune responses and lower viral loads in infected, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)-treated macaques (24). On the other hand, the vaccination of SIV-infected animals that were not treated with HAART resulted in minimal boosting of T-cell responses (15). In addition, a variety of other studies have found a minimal efficacy of therapeutic vaccination during persistent infection (9, 22, 28, 40). While several different systems and methods of therapeutic vaccination have been used, the mechanistic basis for positive effects observed in some studies but not in others remains incompletely understood.

For this study, we used a murine model of chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection to begin to investigate factors that may impact the effectiveness of therapeutic intervention. Therapeutic vaccination with a recombinant vaccinia virus (rVV) expressing the LCMV GP33-41 CD8 T-cell epitope (VVGP33) accelerated viral control in chronically infected mice. However, the boosting of GP33-specific CD8 T-cell responses following therapeutic vaccination was poor compared to the robust reexpansion of memory CD8 T cells upon VVGP33 infection of mice with immunity to LCMV. For chronically infected animals, there was a trend toward better responses to therapeutic vaccination for mice with lower viral loads at the time of vaccination. In addition, the proliferative potential of the GP33-specific CD8 T cells from chronically infected mice was substantially lower than that of the GP33-specific population from mice with immunity to LCMV, suggesting that the poor in vivo T-cell expansion following therapeutic vaccination was likely a limitation of effective boosting of antiviral responses. Thus, therapeutic vaccination can enhance viral control during chronic LCMV infection. However, the effectiveness of therapeutic vaccination may be improved by lowering the prevaccination viral load or augmenting the proliferative potential of the responding T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and viruses.

Four- to 6-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. For the generation of acute infections, mice were infected intraperitoneally with 2 × 105 PFU of LCMV Armstrong (Arm) (1, 2, 43). LCMV Arm is cleared from all tissues during the first 1 to 2 weeks and results in the formation of functional and protective memory CD8 T cells (1, 2, 43). For the initiation of chronic infections, mice were infected with 2 × 106 PFU of LCMV clone 13 as described previously (1, 2, 43). LCMV clone 13 infection results in viremia for ∼3 months, with viral persistence in some tissues for life (1, 2, 43). The vaccinia virus recombinants VVGP33, expressing the GP33-41 epitope, and VVGP283, expressing the H-2Kd-restricted LCMV epitope GP283-292, have been described previously (14, 44). The GP283-292 epitope is not presented in C57BL/6 mice, and the VVGP283 virus is termed control VV in this study. LCMV-immune or chronically infected mice were infected intraperitoneally with 2 × 106 PFU of VV. Viral growth and plaque assays to determine viral titers have been described previously (1, 2, 43).

Lymphocyte isolation and analysis.

Lymphocytes were isolated from tissues and blood as previously described (43, 44). Livers were perfused with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline prior to removal for lymphocyte isolation. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I/peptide tetramers were generated and used as previously described (43, 44). All antibodies were obtained from BD Bioscience (San Diego, Calif.). Intracellular cytokine staining was performed as previously described (43, 44). Briefly, lymphocytes were stimulated with the indicated peptide in the presence of brefeldin A for 5 h at 37°C. The cells were washed, stained with surface antibodies for 30 min, washed two times, fixed, permeabilized, and stained for intracellular cytokines for 1 h. The cells were then washed three times and resuspended in 2% paraformaldehyde.

Adoptive transfers and CFSE and BrdU labeling.

For adoptive transfer experiments, CD8 T cells were purified (>95% pure) from donor spleens by the use of MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, Calif.) as described previously (42-44). Donor populations were adoptively transferred by intravenous injection into the tail vein. Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl diester (CFSE) labeling and in vitro proliferation were performed as previously described (42-44). For bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling, mice were fed 0.8 mg/ml BrdU (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in their drinking water for 7 days. BrdU incorporation was determined by performing intracellular staining with fluorescein isothiocyanate-anti-BrdU (BD Bioscience, San Diego, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

Viral control following therapeutic vaccination.

To examine the effects of therapeutic vaccination during chronic infection, we used a mouse model of infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). The infection of C57BL/6 mice with LCMV clone 13 causes a chronic infection, with viremia peaking between 1 and 2 weeks postinfection (p.i.) (1, 42, 43). Viral replication in most tissues is controlled by ∼3 months p.i., but the virus persists in some tissues for life (1, 42, 43). In contrast to infection by LCMV clone 13, LCMV Armstrong infection is rapidly cleared during the first week of infection by the CD8 T-cell response (1, 42, 43). Since T cells respond to the same epitopes during acute and chronic LCMV infections, one can compare the ability of a therapeutic vaccine to boost responses in mice with immunity to LCMV (>30 days post-Armstrong infection) to that in chronically infected mice (∼30 days post-clone 13 infection).

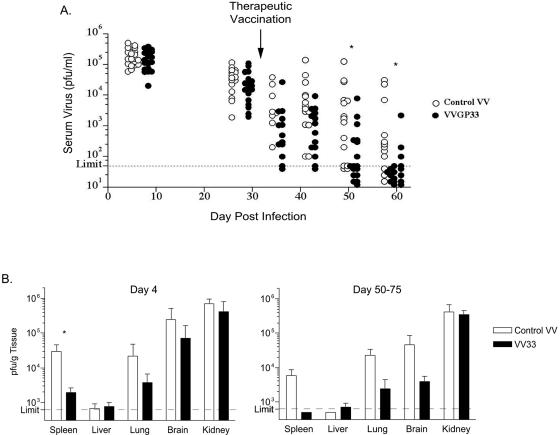

Approximately 1 month after LCMV clone 13 infection, when the viral loads were between ∼103 and 105 PFU/ml of serum, chronically infected mice were therapeutically vaccinated with an rVV expressing the minimal LCMV GP33-41 epitope (VVGP33). This approach targeted only the GP33-specific CD8 T-cell response in infected mice and was not expected to specifically stimulate other LCMV-specific B and T cells. As a control, an rVV expressing an irrelevant CD8 T-cell epitope was used. Changes in the viral load were monitored in chronically infected mice following therapeutic vaccination with either VVGP33 or the control VV (Fig. 1). VVGP33-vaccinated mice had lower viral loads at all time points postvaccination, and the majority of animals receiving the GP33-41-expressing vaccinia virus had controlled LCMV viremia by 1 month after therapeutic vaccination (∼2 months post-LCMV clone 13 infection), while the majority of control vaccinated mice remained viremic at this time point (Fig. 1A). This accelerated viral control following VVGP33 therapeutic vaccination compared to control vaccination was significant (P < 0.05) by 20 days postvaccination. Viral loads were also reduced in multiple tissues from vaccinated mice (including spleens, lungs, and brains) compared to those from the control vaccinated group both early and at later times postvaccination (Fig. 1B). It is interesting, however, that viral clearance from the kidney, a site where T-cell-mediated viral control is difficult (17), was marginally, if at all, impacted by therapeutic VVGP33 vaccination.

FIG. 1.

Enhanced viral control in therapeutically vaccinated mice. (A) C57BL/6 mice were infected with LCMV clone 13, resulting in chronic infection. Between days 30 and 35 p.i., when the viral titers in sera were between 2 × 103 and 2 × 105, mice were immunized with VV expressing the LCMV GP33-41 epitope (VVGP33; filled symbols) or with a control VV expressing an irrelevant epitope (control VV; open symbols). Viral titers in sera were monitored by a plaque assay at the indicated times postinfection. (B) Viral titers in the indicated tissues were determined by a plaque assay on day 4 and days 50 to 75 post-therapeutic vaccination. The data are representative of four independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between the control VV- and VVGP33-vaccinated groups are indicated (*).

Boosting of circulating CD8 T-cell responses by therapeutic vaccination.

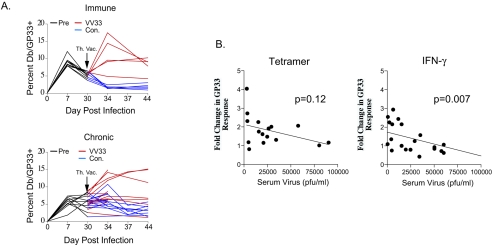

To investigate the relationship between the LCMV-specific CD8 T-cell response following therapeutic vaccination and viral control, we longitudinally monitored the Db/GP33-specific T-cell response in the blood of mice receiving therapeutic vaccination. In addition, we included a group of mice with immunity to LCMV Armstrong (at >30 days p.i.), containing memory CD8 T cells known to respond robustly to rechallenge (13, 44), for comparison. Indeed, in these mice with immunity to LCMV Armstrong, VVGP33 infection resulted in a substantial expansion of the Db/GP33-specific CD8 T-cell population in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, which peaked on day 4 p.i. (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the therapeutic vaccination of chronically infected mice resulted in a more variable and generally weaker expansion of the Db/GP33-specific CD8 T-cell population. While significant boosting was observed in some mice, in the majority of animals the responses were enhanced marginally, if at all (Fig. 2A). It should be noted that VVGP33 can stimulate both Db/GP33- and Kb/GP34-specific CD8 T-cell responses. However, the Kb/GP34-specific CD8 T-cell population is physically deleted during LCMV clone 13 infection (12, 43), and the Kb/GP34 tetramer-positive population remained below the limit of detection following VVGP33 vaccination in this study (data not shown). Vaccination with the control rVV resulted in no change or even a slight decrease in the frequency of Db/GP33-specific T cells (which may reflect the expansion of VV-specific cells) in both LCMV-immune mice and most chronically infected mice (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Effective boosting of circulating virus-specific CD8 T cells by therapeutic vaccination correlates with low viral load. (A) Mice with immunity to LCMV (>30 days post-LCMV Armstrong vaccination) and chronically infected mice (∼30 days post-LCMV clone 13 infection) were vaccinated with VVGP33, and changes in the numbers of Db/GP33 tetramer-positive CD8 T cells were monitored in the blood on days 0, 4, 7, and 14 post-therapeutic vaccination. The frequencies of Db/GP33 tetramer-positive CD8 T cells in the blood are shown for individual mice following infection with either VVGP33 (red lines) or a control VV (blue lines). (B) Changes in the GP33-specific CD8 T-cell responses in the blood of chronically infected mice, measured by MHC tetramer staining (left panel) or intracellular IFN-γ staining (right panel) at 4 to 7 days post-therapeutic vaccination, were plotted versus the viral load at the time of VVGP33 vaccination. Linear regression analysis revealed a significant correlation between improved responses, as measured by IFN-γ production, and a lower viral load at the time of vaccination. P values indicate the significance of the correlation.

Therapeutic vaccination boosts CD8 T-cell responses more effectively in the presence of low viral loads.

We next examined whether there was any relationship between the viral load at the time of therapeutic vaccination and the ability of GP33-specific CD8 T cells to respond. The change in the GP33-specific CD8 T-cell response in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of vaccinated mice was compared with the viral load in the serum at the time of vaccination (Fig. 2B). There was a trend for mice with lower viral loads at the time of therapeutic vaccination to respond more vigorously to VVGP33 when the GP33 response was measured by MHC tetramer staining. This correlation was stronger and became statistically significant when the GP33 response was measured by intracellular gamma interferon (IFN-γ) staining, suggesting a change in the functionality of the GP33-specific CD8 T cells following therapeutic vaccination (see below). Thus, therapeutic vaccination led to accelerated viral control in chronically infected mice, but the efficacy of this approach was improved when the viral load was low at the time of VVGP33 vaccination. To begin to understand why responses to therapeutic vaccination were poor when viral loads were high, in subsequent experiments we focused on groups of mice in which prevaccination viremia was above ∼104 PFU/ml in the serum.

Boosting of LCMV-specific CD8 T-cell numbers and function by therapeutic vaccination.

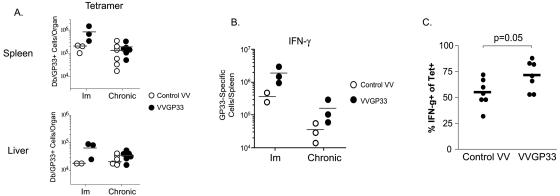

The absolute number of Db/GP33-specific CD8 T cells was quantified in the spleen and liver during the first week after therapeutic vaccination by MHC tetramer staining (Fig. 3A). While VVGP33 vaccination resulted in a substantial increase in the number of GP33-specific T cells in LCMV-immune mice, there was a relatively small increase in the total number of Db/GP33 tetramer-positive cells in the spleens or livers of chronically infected mice after vaccination (Fig. 3A). In contrast, an increase in the GP33-specific CD8 T-cell response following therapeutic vaccination was observed when it was quantified by intracellular staining for IFN-γ following peptide stimulation (Fig. 3B). Together with the relatively minimal change in the number of Db/GP33 tetramer-positive cells/spleen following VVGP33 vaccination (Fig. 3A) and the correlation data shown in Fig. 2B, these results suggest that therapeutic vaccination with VVGP33 improved the functional quality of the GP33-specific T-cell population in chronically infected mice. To test this possibility, we determined the percentage of Db/GP33 tetramer-positive cells that were capable of producing IFN-γ following GP33 peptide stimulation as a measure of the functionality of this CD8 T-cell population. An increase in the per cell function was indeed observed in therapeutically vaccinated mice compared to controls (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

GP33-specific CD8 T-cell numbers in the spleen and liver were only marginally increased following VVGP33 therapeutic vaccination. (A) The total number of Db/GP33 tetramer-positive CD8 T cells in the spleen or liver was determined 4 days after the infection of LCMV-immune or chronically infected mice with a control VV or VVGP33. The data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) The total number of GP33-specific CD8 T cells in the spleen was determined by intracellular IFN-γ staining 4 days after the infection of LCMV-immune (Im) or chronically infected mice with a control VV or VVGP33. (C) The level of functional exhaustion at 4 days post-VVGP33 infection of chronically infected mice was measured by determining the percentage of the MHC tetramer-positive CD8 T-cell population that could produce IFN-γ following 5 h of peptide stimulation. Horizontal bars indicate the averages for the groups.

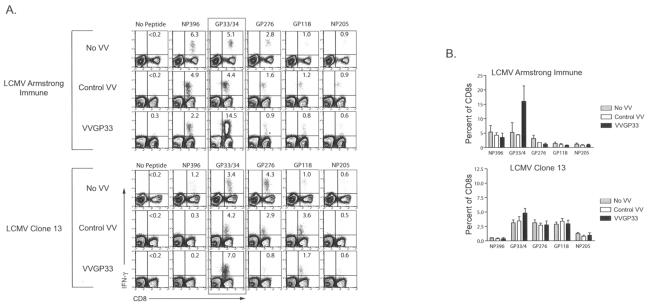

Boosting by therapeutic vaccination is highly specific for the targeted epitope.

To examine whether therapeutic vaccination using VVGP33 influenced the responses of other LCMV-specific CD8 T-cell populations, we quantified four additional LCMV-specific CD8 T-cell responses by staining for intracellular IFN-γ following 5 h of peptide stimulation. VVGP33 vaccination induced an expansion of only the GP33-specific CD8 T cells, and VV infection (with control VV or VVGP33) did not substantially alter any other LCMV-specific CD8 T-cell response examined (Fig. 4A and B). In mice with immunity to LCMV Arm, a dramatic increase in the GP33-specific CD8 T-cell response was again observed following VVGP33 infection (Fig. 4A and B). In chronically infected mice, there was a modest increase in the frequency of GP33-specific IFN-γ-producing CD8 T cells in the VVGP33-vaccinated group compared to control vaccinated and unvaccinated mice (Fig. 4A and B).

FIG. 4.

Therapeutic vaccination with VVGP33 does not enhance responses to other epitopes. (A) Responses to five different LCMV epitopes in the spleen were determined on day 4 post-therapeutic vaccination by intracellular IFN-γ staining following 5 h of stimulation. The data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) The percentages of IFN-γ-producing CD8 T cells specific for each of the five LCMV peptides from panel A are summarized for multiple mice (n = 3 to 12 for each response).

Low proliferative potential limits response to therapeutic vaccination.

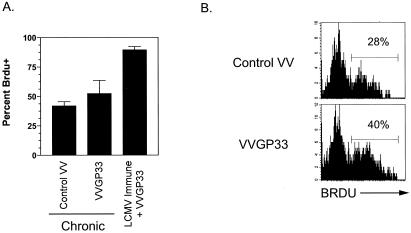

We next wanted to evaluate whether VVGP33 vaccination of clone 13-infected mice was capable of inducing T-cell proliferation. Chronically infected mice were fed BrdU in their drinking water and either vaccinated with the control rVV or given VVGP33. As controls, a group of mice with immunity to LCMV Arm were also fed BrdU and infected with VVGP33. One week later, the percentage of Db/GP33-specific T cells that had incorporated BrdU was measured (Fig. 5A and B). For LCMV-immune mice, the vast majority of Db/GP33 tetramer-positive cells incorporated BrdU following VVGP33 infection. In contrast, for chronically infected mice, there was only a marginal increase in the proliferation of Db/GP33-specific CD8 T cells following VVGP33 vaccination compared to the control vaccinated group (Fig. 5A and B).

FIG. 5.

Therapeutic vaccination results in only a modest increase in virus-specific CD8 T-cell division in vivo. (A) Chronically infected mice were infected with control VV or VVGP33 and also fed BrdU in their drinking water. After 7 days, the mice were sacrificed and the percentage of Db/GP33 tetramer-positive cells that had incorporated BrdU was determined. A group of control mice with immunity to LCMV Armstrong were also infected with VVGP33 and fed BrdU, and the turnover of Db/GP33 tetramer-positive CD8 T cells was determined for these mice on day 7 p.i. (n = 3/group) and is representative of two independent experiments. (B) An example of BrdU staining in chronically infected mice 7 days after control VV or VVGP33 vaccination. The levels of BrdU incorporation were not substantially different between control VV-infected and chronically infected mice that did not receive VV (data not shown).

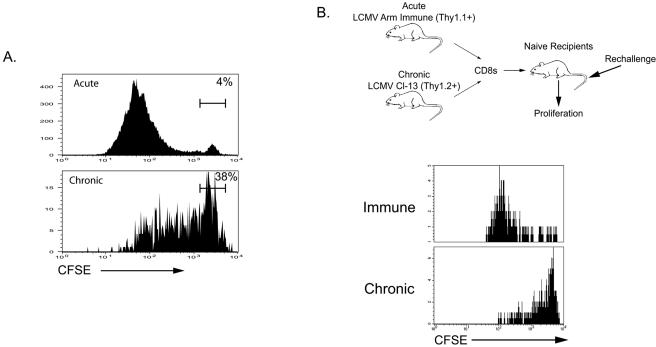

The BrdU labeling experiments suggested that a limited proliferative capacity may hinder the ability of virus-specific CD8 T cells to respond vigorously to therapeutic vaccination during chronic infection. However, it was also possible that the environment of the chronically infected mice prevented optimal responses to VVGP33 infection. To address this possibility, we performed two additional experiments. First, Db/GP33-specific CD8 T cells from LCMV-immune or chronically infected mice were labeled with CFSE and stimulated in vitro with the GP33 peptide. For these experiments, purified CD8 T cells were mixed with CD8-depleted splenocytes from naïve mice as antigen-presenting cells to provide similar stimulatory signals to both Db/GP33-specific CD8 T-cell populations. After 84 h, extensive proliferation was observed by the Db/GP33-specific memory CD8 T cells from LCMV-immune mice, but there was substantially less proliferation of Db/GP33-specific CD8 T cells from chronically infected mice (Fig. 6A). A much larger fraction of the Db/GP33-specific CD8 T cells from chronically infected mice remained undivided compared to that of memory CD8 T cells from immune mice (∼40% versus ∼5%), and T cells from chronically infected mice that did undergo division appeared to divide less than the Db/GP33-specific memory T-cell population from immune mice (Fig. 6A). Since in vitro cultures may not accurately reflect the dynamics of T-cell stimulation and expansion following viral infection in vivo, we next assessed the proliferative capacity in intact animals. We used an adoptive transfer system by which the responses of both populations of GP33-specific CD8 T cells could be tracked in the same host. CD8 T cells from mice with immunity to LCMV Arm (Thy1.1+) and from LCMV clone 13-infected mice (Thy1.2+) were purified and labeled with CFSE, and the two populations were mixed to obtain equal numbers of GP33-specific CD8 T cells. This mixture was then adoptively transferred to naïve recipients, and these mice were challenged with LCMV clone 13. The proliferation of each population of GP33-specific T cells (differentiated by Thy1.1 and Thy1.2 staining) was analyzed by the dilution of CFSE on day 2.5 p.i. This approach allowed a direct comparison of the proliferative potentials of LCMV Arm-derived and clone 13-derived CD8 T cells on a per cell basis in the same environment in vivo. As shown in Fig. 6B, virus-specific CD8 T cells from chronically infected mice had a severely decreased proliferative capacity following antigen reencounter in vivo. This was the case despite the vigorous proliferation of Arm-immune CD8 T cells in the same environment. Similarly, the adoptive transfer of clone 13-derived versus Arm-immune CD8 T cells back into chronically infected mice demonstrated that the Arm-immune CD8 T cells expanded more even when transferred into mice with ongoing chronic infections (data not shown). Interestingly, the defect in proliferative potential in the LCMV-specific CD8 T cells during chronic infection was more dramatic in vivo than in vitro in these experiments. Thus, the relatively poor response to therapeutic vaccination likely reflects, at least in part, intrinsic cell defects in the proliferative potential of virus-specific CD8 T cells generated during chronic LCMV infection.

FIG. 6.

Poor T-cell expansion following therapeutic vaccination of chronically infected mice is due to intrinsic cell defects in proliferative potential. (A) CD8 T cells were purified from mice with immunity to LCMV Arm (on day 180 p.i.) and LCMV clone 13-infected mice (on day 35 p.i.) by the use of magnet-associated cell sorter beads (>95% pure; data not shown). These cells were labeled with CFSE and mixed with CD8-depleted splenocytes from naïve mice. The GP33 peptide was added (0.2 μg/ml), and proliferation was assessed after 84 h by staining with CD8 and Db/GP33 tetramers. Similar division profiles were also observed for other LCMV-specific CD8 T-cell responses (data not shown). (B) CD8 T cells were purified from Thy1.1+ LCMV-immune mice (on day 130 p.i.) and from Thy1.2+ chronically infected mice (LCMV clone 13; day 40), labeled with CFSE, and mixed to contain equal numbers of Db/GP33 tetramer-positive CD8 T cells (∼105 of each). This mixture was adoptively transferred to naïve recipients, and these recipients were immediately infected with LCMV clone 13. The division of donor GP33-specific CD8 T cells was determined by CFSE dilution after 65 h. The plots were gated on Thy1.1+ (top) or Thy1.2+ (bottom) Db/GP33 tetramer-positive CD8 T cells from the spleen. Similar division profiles were observed for other LCMV epitopes and other tissues (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

While therapeutic vaccination holds promise for enhancing the control of chronic infections (4), the efficacy of this approach has been disappointing in many situations (9, 22, 28, 40). In this study, we have begun to examine the potential of therapeutic vaccination to alter the course of chronic infection and the possible limitations associated with poor responses to this type of therapeutic intervention. While our results demonstrate that therapeutic vaccination during chronic LCMV infection can enhance viral control, the level of T-cell boosting in most chronically infected mice was modest, suggesting that vigorous responses to therapeutic vaccination may not always be achieved. Indeed, a low proliferative potential of virus-specific CD8 T cells and a high viral load may both contribute to weak responses to therapeutic intervention. Thus, this study supports the promise of therapeutic vaccination as a useful tool to enhance antiviral responses but also suggests that we may need to overcome challenges associated with poor T-cell responses during chronic infections.

A critical finding of the present study is that therapeutic vaccination is more effective when the viral load is low. These data fit well with our current understanding of T-cell dysfunction during chronic infections (41). First, CD8 T-cell exhaustion during chronic infections occurs in a hierarchical manner, with CD8 T cells gradually losing different effector functions as the viral load increases (interleukin-2 [IL-2] is lost first, followed by ex vivo killing and the loss of tumor necrosis factor alpha and finally the loss of IFN-γ), and eventually virus-specific CD8 T cells may be physically deleted (12, 43). On the one hand, when the viral load is high and exhaustion and/or deletion is severe, therapeutic vaccination alone is unlikely to be highly beneficial. Indeed, the therapeutic vaccination of mice infected with LCMV in utero (LCMV carrier mice), which experienced life-long infection and possessed few, if any, LCMV-specific T cells, did not result in viral clearance or generate substantial LCMV-specific responses (40). Similarly poor results have been reported for the therapeutic vaccination of human hepatitis B virus (HBV) carriers, who are also often characterized by weak to undetectable antiviral responses (9). In these settings, central or peripheral tolerance and the deletion of virus-specific T cells may result in very few, if any, T cells that can be targeted or boosted by a therapeutic vaccine, and these observations suggest that it will be difficult to generate a de novo antiviral response in some cases. On the other hand, our data also suggest that at lower viral loads, when T-cell exhaustion/deletion is less extreme, therapeutic vaccination will be more effective. The clinical implications of this correlation between the viral load and the response to therapeutic vaccination are obvious. If the viral load can be lowered (e.g., by the use of antiviral drugs) and T-cell function thus improves, then the effectiveness of therapeutic vaccination may be enhanced. Indeed, studies with nonhuman primates support this idea since therapeutic vaccination is more effective following HAART-mediated control of SIV replication (15). In future studies, it will be important to more fully determine the impact of changes in the viral load on the effectiveness of therapeutic vaccination.

During the differentiation of effector T cells into memory T cells, the proliferative potential for antigen stimulation increases substantially (19, 42, 44). The ability to vigorously proliferate upon reinfection results in the generation of a large pool of secondary effector T cells and is central to providing optimal protective immunity (44). The development of a robust proliferative potential is often compromised during chronic infections (41, 42). In fact, individuals whose HIV-specific CD8 T cells retain a high proliferative potential tend to progress more slowly to disease (7, 16, 26), suggesting that during chronic infections in humans, a robust proliferative capacity of virus-specific CD8 T cells in response to antigen will be a key factor in maintaining or restoring effective antiviral immunity. Our findings of a poor proliferation of LCMV-specific CD8 T cells in response to therapeutic vaccination indicate that this may be a major reason why we did not observe a more effective boosting of antiviral responses. The same VVGP33 infection induced a robust reexpansion of memory CD8 T cells in mice with immunity to LCMV, demonstrating that this is a highly immunogenic vaccination approach. Furthermore, our adoptive transfer experiments comparing both memory CD8 T cells and CD8 T cells from chronically infected mice showed that the poor expansion of GP33-specific CD8 T cells from clone 13-infected mice is an intrinsic property of CD8 T cells generated during chronic infection. Memory T cells are known to exist in a unique state of the cell cycle, poised for rapid proliferation (21, 39). It will be important to determine whether CD8 T cells generated during a chronic infection can attain this cell cycle status or whether other defects exist in T-cell proliferation and/or survival upon antigen reencounter.

Our results demonstrate that providing antigen to chronically infected mice in the context of VV infection enhances viral control. While these data are encouraging for immunotherapy, they are also somewhat paradoxical. It is perhaps surprising that providing more antigen to a chronically infected animal has any beneficial impact, since too much antigen appears to drive T-cell dysfunction (43). Two possible mechanisms may account for these observations. First, it is possible that the level of GP33 peptide expressed by VVGP33 greatly exceeds the level of this epitope presented in vivo at approximately day 30 of chronic LCMV infection (i.e., when VVGP33 is given). In this scenario, GP33-specific CD8 T cells may respond poorly to the level of antigen presented endogenously but may produce antiviral cytokines and/or reactivate the lytic machinery in vivo in response to the higher levels of GP33 peptide produced by VVGP33 infection (i.e., therapeutic vaccination causes GP33-specific CD8 T cells during chronic infection to become more effector-like but does not result in dramatic expansion). A second possibility is that the cells presenting VV-expressed antigens may be more stimulatory than or provide qualitatively distinct signals compared to cells infected by LCMV during chronic infection. Chronic infections are often associated with immunosuppression, including defects in dendritic cell functions (11, 27, 33, 34, 36). In particular, LCMV is known to impair dendritic cell maturation and antigen-presenting/costimulatory functions (33, 34). It is possible that not only intrinsic T-cell characteristics but also these environmental factors impede optimal CD8 T-cell responses during chronic infections. Perhaps VVGP33 infection augments CD8 T-cell responses in part due to changes in inflammatory signals or changes in costimulation or antigen-presenting cell function that overcome the immunosuppressive environment. Future studies are necessary to fully examine these issues. It is important, however, that the control VV used for this study did not alter the course of chronic LCMV infection, demonstrating that the inflammatory signals associated with VV infection alone do not contribute to enhanced antiviral responses to chronic LCMV infection. Dendritic cell vaccination approaches have shown considerable promise in some therapeutic settings (23, 24), perhaps because these cells can present antigens in the optimal context for T cells generated during chronic infections. It will be important to determine whether different vaccination approaches that optimize either antigen levels, antigen presentation, or inflammatory signals can increase the effectiveness of therapeutic vaccination.

An important issue raised by this study is the need to determine the mechanism of the enhanced function of LCMV-specific CD8 T cells in chronically infected mice as a result of therapeutic vaccination. The increase in functionality of the GP33-specific CD8 T-cell population following VVGP33 infection may result from (i) the generation of a de novo anti-GP33 response from naïve CD8 T cells, (ii) preferential expansion of the more functional subset of the GP33-specific CD8 T-cell population, or (iii) a reversal of functional exhaustion. These scenarios are not mutually exclusive, and the contribution of each to the boosting of T-cell responses may depend on the nature of the chronic infection. For example, it is unlikely that naïve CD8 T cells contributed significantly to the responses observed in the present study since the thymus is heavily infected during chronic LCMV infection (2, 17; data not shown) and few LCMV-specific naïve T-cell precursors are likely to exist due to central tolerance mechanisms. However, during other chronic infections in which viral replication is more restricted, the generation of de novo responses to a therapeutic vaccine may be an important pathway for enhancing immunity. It is difficult to distinguish between the last two possibilities, i.e., the preferential boosting of a subset of CD8 T cells versus a partial reversal of functional exhaustion, based on the present study. The mechanistic distinction between these two possibilities, however, is profound and will have important implications, not only for designing effective immunotherapies but also for understanding CD8 T-cell differentiation during chronic infections. Distinguishing between these possible mechanisms and examining the reversibility of exhaustion are important goals of future studies.

In previous work, we demonstrated the beneficial effects of IL-2 therapy (5) and also characterized defects in CD8 T-cell responsiveness to IL-7 and IL-15 during chronic LCMV infection (42). These observations, together with the data presented in the present study, suggest that future efforts should be focused on combining immunotherapy and therapeutic vaccination. For example, if γ-chain cytokine therapy can enhance the proliferation and/or survival of antigen-specific T cells, the effects of combining this treatment with therapeutic vaccination may be highly beneficial. In addition, negative regulatory pathways including inhibitory receptors (8, 35) and regulatory T cells (10, 32, 37) may limit the responsiveness of T cells during chronic infections. By removing or temporarily blocking these pathways, we may also be able to improve responses to therapeutic vaccines.

Therapeutic vaccination is a promising and potentially powerful approach to improving the immune control of chronic infections. The data presented in this study demonstrate that vaccinating chronically infected mice can augment viral control, but they also point to a high viral load and a low T-cell proliferative potential as two factors that may limit robust responses to therapeutic interventions. By testing different antigen delivery systems (other viral vectors, DNA, virus-like particles, dendritic cells, etc.) and also combining therapeutic vaccination with other immunotherapies, it should be possible to overcome these current challenges and improve the effectiveness of this approach.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lena Blinder, Safronia Jenkins, Bogna Konieczny, and Patryce Mahar for their technical assistance.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant AI30048 to R.A.) and the Cancer Research Institute (E.J.W.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed, R., and M. B. Oldstone. 1988. Organ-specific selection of viral variants during chronic infection. J. Exp. Med. 167:1719-1724. (Erratum, 168:457.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed, R., A. Salmi, L. D. Butler, J. M. Chiller, and M. B. Oldstone. 1984. Selection of genetic variants of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in spleens of persistently infected mice. Role in suppression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and viral persistence. J. Exp. Med. 160:521-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen, T. M., D. H. O'Connor, P. Jing, J. L. Dzuris, B. R. Mothe, T. U. Vogel, E. Dunphy, M. E. Liebl, C. Emerson, N. Wilson, K. J. Kunstman, X. Wang, D. B. Allison, A. L. Hughes, R. C. Desrosiers, J. D. Altman, S. M. Wolinsky, A. Sette, and D. I. Watkins. 2000. Tat-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes select for SIV escape variants during resolution of primary viraemia. Nature 407:386-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Autran, B., G. Carcelain, B. Combadiere, and P. Debre. 2004. Therapeutic vaccines for chronic infections. Science 305:205-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blattman, J. N., J. M. Grayson, E. J. Wherry, S. M. Kaech, K. A. Smith, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Therapeutic use of IL-2 to enhance antiviral T-cell responses in vivo. Nat. Med. 9:540-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bocher, W. O., B. Dekel, W. Schwerin, M. Geissler, S. Hoffmann, A. Rohwer, F. Arditti, A. Cooper, H. Bernhard, A. Berrebi, S. Rose-John, Y. Shaul, P. R. Galle, H. F. Lohr, and Y. Reisner. 2001. Induction of strong hepatitis B virus (HBV) specific T helper cell and cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses by therapeutic vaccination in the trimera mouse model of chronic HBV infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:2071-2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenchley, J. M., N. J. Karandikar, M. R. Betts, D. R. Ambrozak, B. J. Hill, L. E. Crotty, J. P. Casazza, J. Kuruppu, S. A. Migueles, M. Connors, M. Roederer, D. C. Douek, and R. A. Koup. 2003. Expression of CD57 defines replicative senescence and antigen-induced apoptotic death of CD8+ T cells. Blood 101:2711-2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, L. 2004. Co-inhibitory molecules of the B7-CD28 family in the control of T-cell immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:336-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dikici, B., A. G. Kalayci, F. Ozgenc, M. Bosnak, M. Davutoglu, A. Ece, T. Ozkan, T. Ozeke, R. V. Yagci, and K. Haspolat. 2003. Therapeutic vaccination in the immunotolerant phase of children with chronic hepatitis B infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 22:345-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dittmer, U., H. He, R. J. Messer, S. Schimmer, A. R. Olbrich, C. Ohlen, P. D. Greenberg, I. M. Stromnes, M. Iwashiro, S. Sakaguchi, L. H. Evans, K. E. Peterson, G. Yang, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2004. Functional impairment of CD8(+) T cells by regulatory T cells during persistent retroviral infection. Immunity 20:293-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douek, D. C., L. J. Picker, and R. A. Koup. 2003. T cell dynamics in HIV-1 infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:265-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuller, M. J., and A. J. Zajac. 2003. Ablation of CD8 and CD4 T cell responses by high viral loads. J. Immunol. 170:477-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grayson, J. M., L. E. Harrington, J. G. Lanier, E. J. Wherry, and R. Ahmed. 2002. Differential sensitivity of naive and memory CD8(+) T cells to apoptosis in vivo. J. Immunol. 169:3760-3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrington, L. E., R. van der Most, J. L. Whitton, and R. Ahmed. 2002. Recombinant vaccinia virus-induced T-cell immunity: quantitation of the response to the virus vector and the foreign epitope. J. Virol. 76:3329-3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hel, Z., D. Venzon, M. Poudyal, W. P. Tsai, L. Giuliani, R. Woodward, C. Chougnet, G. Shearer, J. D. Altman, D. Watkins, N. Bischofberger, A. Abimiku, P. Markham, J. Tartaglia, and G. Franchini. 2000. Viremia control following antiretroviral treatment and therapeutic immunization during primary SIV251 infection of macaques. Nat. Med. 6:1140-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyasere, C., J. C. Tilton, A. J. Johnson, S. Younes, B. Yassine-Diab, R. P. Sekaly, W. W. Kwok, S. A. Migueles, A. C. Laborico, W. L. Shupert, C. W. Hallahan, R. T. Davey, Jr., M. Dybul, S. Vogel, J. Metcalf, and M. Connors. 2003. Diminished proliferation of human immunodeficiency virus-specific CD4+ T cells is associated with diminished interleukin-2 (IL-2) production and is recovered by exogenous IL-2. J. Virol. 77:10900-10909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jamieson, B. D., L. D. Butler, and R. Ahmed. 1987. Effective clearance of a persistent viral infection requires cooperation between virus-specific Lyt2+ T cells and nonspecific bone marrow-derived cells. J. Virol. 61:3930-3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung, M. C., N. Gruner, R. Zachoval, W. Schraut, T. Gerlach, H. Diepolder, C. A. Schirren, M. Page, J. Bailey, E. Birtles, E. Whitehead, J. Trojan, S. Zeuzem, and G. R. Pape. 2002. Immunological monitoring during therapeutic vaccination as a prerequisite for the design of new effective therapies: induction of a vaccine-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferative response in chronic hepatitis B carriers. Vaccine 20:3598-3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaech, S. M., S. Hemby, E. Kersh, and R. Ahmed. 2002. Molecular and functional profiling of memory CD8 T cell differentiation. Cell 111:837-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keadle, T. L., K. A. Laycock, J. L. Morris, D. A. Leib, L. A. Morrison, J. S. Pepose, and P. M. Stuart. 2002. Therapeutic vaccination with vhs(−) herpes simplex virus reduces the severity of recurrent herpetic stromal keratitis in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2361-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latner, D. R., S. M. Kaech, and R. Ahmed. 2004. Enhanced expression of cell cycle regulatory genes in virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells. J. Virol. 78:10953-10959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindenburg, C. E., I. Stolte, M. W. Langendam, F. Miedema, I. G. Williams, R. Colebunders, J. N. Weber, M. Fisher, and R. A. Coutinho. 2002. Long-term follow-up: no effect of therapeutic vaccination with HIV-1 p17/p24:Ty virus-like particles on HIV-1 disease progression. Vaccine 20:2343-2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu, W., L. C. Arraes, W. T. Ferreira, and J. M. Andrieu. 2004. Therapeutic dendritic-cell vaccine for chronic HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 10:1359-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu, W., X. Wu, Y. Lu, W. Guo, and J. M. Andrieu. 2003. Therapeutic dendritic-cell vaccine for simian AIDS. Nat. Med. 9:27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matano, T., R. Shibata, C. Siemon, M. Connors, H. C. Lane, and M. A. Martin. 1998. Administration of an anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody interferes with the clearance of chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus during primary infections of rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 72:164-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Migueles, S. A., A. C. Laborico, W. L. Shupert, M. S. Sabbaghian, R. Rabin, C. W. Hallahan, D. Van Baarle, S. Kostense, F. Miedema, M. McLaughlin, L. Ehler, J. Metcalf, S. Liu, and M. Connors. 2002. HIV-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation is coupled to perforin expression and is maintained in nonprogressors. Nat. Immunol. 3:1061-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naniche, D., and M. B. Oldstone. 2000. Generalized immunosuppression: how viruses undermine the immune response. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 57:1399-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nevens, F., T. Roskams, H. Van Vlierberghe, Y. Horsmans, D. Sprengers, A. Elewaut, V. Desmet, G. Leroux-Roels, E. Quinaux, E. Depla, S. Dincq, C. Vander Stichele, G. Maertens, and F. Hulstaert. 2003. A pilot study of therapeutic vaccination with envelope protein E1 in 35 patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 38:1289-1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oxenius, A., D. A. Price, A. Trkola, C. Edwards, E. Gostick, H. T. Zhang, P. J. Easterbrook, T. Tun, A. Johnson, A. Waters, E. C. Holmes, and R. E. Phillips. 2004. Loss of viral control in early HIV-1 infection is temporally associated with sequential escape from CD8+ T cell responses and decrease in HIV-1-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell frequencies. J. Infect. Dis. 190:713-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pancholi, P., D. H. Lee, Q. Liu, C. Tackney, P. Taylor, M. Perkus, L. Andrus, B. Brotman, and A. M. Prince. 2001. DNA prime/canarypox boost-based immunotherapy of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in a chimpanzee. Hepatology 33:448-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richards, C. M., R. Case, T. R. Hirst, T. J. Hill, and N. A. Williams. 2003. Protection against recurrent ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 disease after therapeutic vaccination of latently infected mice. J. Virol. 77:6692-6699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakaguchi, S. 2004. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory T cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22:531-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sevilla, N., S. Kunz, A. Holz, H. Lewicki, D. Homann, H. Yamada, K. P. Campbell, J. C. de La Torre, and M. B. Oldstone. 2000. Immunosuppression and resultant viral persistence by specific viral targeting of dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 192:1249-1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sevilla, N., D. B. McGavern, C. Teng, S. Kunz, and M. B. Oldstone. 2004. Viral targeting of hematopoietic progenitors and inhibition of DC maturation as a dual strategy for immune subversion. J. Clin. Investig. 113:737-745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharpe, A. H., and G. J. Freeman. 2002. The B7-CD28 superfamily. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:116-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slifka, M. K., D. Homann, A. Tishon, R. Pagarigan, and M. B. Oldstone. 2003. Measles virus infection results in suppression of both innate and adaptive immune responses to secondary bacterial infection. J. Clin. Investig. 111:805-810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suvas, S., U. Kumaraguru, C. D. Pack, S. Lee, and B. T. Rouse. 2003. CD4+CD25+ T cells regulate virus-specific primary and memory CD8+ T cell responses. J. Exp. Med. 198:889-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tryniszewska, E., J. Nacsa, M. G. Lewis, P. Silvera, D. Montefiori, D. Venzon, Z. Hel, R. W. Parks, M. Moniuszko, J. Tartaglia, K. A. Smith, and G. Franchini. 2002. Vaccination of macaques with long-standing SIVmac251 infection lowers the viral set point after cessation of antiretroviral therapy. J. Immunol. 169:5347-5357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veiga-Fernandes, H., and B. Rocha. 2004. High expression of active CDK6 in the cytoplasm of CD8 memory cells favors rapid division. Nat. Immunol. 5:31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.von Herrath, M. G., D. P. Berger, D. Homann, T. Tishon, A. Sette, and M. B. Oldstone. 2000. Vaccination to treat persistent viral infection. Virology 268:411-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wherry, E. J., and R. Ahmed. 2004. Memory CD8 T-cell differentiation during viral infection. J. Virol. 78:5535-5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wherry, E. J., D. L. Barber, S. M. Kaech, J. N. Blattman, and R. Ahmed. 2004. Antigen-independent memory CD8 T cells do not develop during chronic viral infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:16004-16009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wherry, E. J., J. N. Blattman, K. Murali-Krishna, R. van der Most, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J. Virol. 77:4911-4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wherry, E. J., V. Teichgraber, T. C. Becker, D. Masopust, S. M. Kaech, R. Antia, U. H. von Andrian, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Nat. Immunol. 4:225-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]