Abstract

Ovarian cancer continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality in women, with immune regulation playing a critical role in its progression and treatment response. This review explores the interplay between sex hormones, particularly estrogen and progesterone, and immune regulation in ovarian cancer. We delve into the mechanisms by which these hormones influence immune cell function, modulate immune checkpoints, and alter the tumor microenvironment. Key pathways involving estrogen and progesterone receptors are examined, highlighting their impact on tumor growth and immune evasion. The review also discusses the therapeutic implications of these interactions, including the potential for combining hormone-based therapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Personalized medicine approaches, leveraging biomarkers for predicting treatment response, are considered essential for optimizing patient outcomes. Finally, we address current research gaps and future directions, emphasizing the need for advanced research technologies and novel therapeutic strategies to improve the treatment of ovarian cancer through a better understanding of hormone-immune interactions.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, Sex hormones, Estrogen, Progesterone, Immune regulation

Introduction

Ovarian cancer ranks as the fifth leading cause of cancer fatalities in women and stands as the deadliest form of gynecological malignancies [1, 2]. According to recent global cancer statistics, around 295,000 new cases of ovarian cancer are diagnosed each year, resulting in more than 184,000 deaths [3, 4]. The high mortality rate is primarily due to most patients being diagnosed at an advanced stage, as early-stage ovarian cancer often presents with non-specific symptoms that are easily overlooked [5, 6]. The disease is usually detected when it has already spread beyond the ovaries, significantly complicating treatment and reducing survival rates. The treatment for ovarian cancer usually includes a combination of surgical intervention and chemotherapy [7, 8]. The initial step, surgical debulking, aims to remove the maximum amount of tumor mass. This is followed by platinum-based chemotherapy to address any remaining disease. Despite initial responses to chemotherapy, many patients experience recurrence, often with chemoresistant disease. This recurrence underscores the critical need for novel therapeutic strategies. Emerging treatments, such as targeted therapies and immunotherapies, offer new hope but come with their own set of challenges, including identifying appropriate patient populations and managing potential side effects [9–11]. The heterogeneity of ovarian cancer further complicates treatment, as different subtypes may respond differently to the same therapy.

The immune system plays a crucial role in both the progression of ovarian cancer and the response to its treatment. The tumor microenvironment, composed of various immune cells, stromal elements, and signaling molecules, significantly influences cancer behavior [12, 13]. Immune cells such as T lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells can either inhibit or promote tumor growth, depending on their activation state and the signals they receive from the tumor and its microenvironment [14, 15]. In ovarian cancer, a greater number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is associated with improved prognosis, indicating that a strong anti-tumor immune response can lead to more favorable clinical outcomes. On the other hand, the infiltration of immunosuppressive cells can hinder effective immune responses, thereby promoting tumor progression and metastasis [16–18]. Immune checkpoints, such as PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4, are crucial in regulating the immune response and often enable tumors to evade immunity [19–21]. Recent advances in immunotherapy involve treatments like immune checkpoint inhibitors and adoptive T cell therapy, has significantly advanced cancer treatment. However, these therapies have shown only modest efficacy in ovarian cancer compared other cancers.

Sex hormones, particularly estrogen and progesterone, play a key role in the development and progression of ovarian cancer [22–24]. These hormones bind to their respective receptors, ER and PR, acting as transcription factors to regulate gene expression. Estrogen and progesterone impact several cellular processes, which are essential in cancer development. The hormonal regulation of immune function is complex and context-dependent, often varying with hormone levels, receptor expression, and the tumor microenvironment. The interplay between sex hormones and immune regulation is particularly pertinent, given the hormonal sensitivity of the ovaries and the immune-rich environment of the peritoneal cavity where ovarian cancer typically spreads.

This review endeavors to delve into the complex dynamics between sex hormones and immune regulation in ovarian cancer, with a particular focus on how estrogen and progesterone shape immune responses within the tumor microenvironment. Our aim is to unravel the mechanisms by which these hormones impact tumor progression, immune evasion, and therapeutic outcomes. Discuss the mechanisms by which estrogen and progesterone affect immune cell function and distribution in ovarian cancer. Examine the impact of hormonal modulation on immune checkpoints and tumor-immune interactions. Evaluate the therapeutic implications of these interactions, including the potential for combining hormone-based therapies with immunotherapies. Highlight current research gaps and propose future directions for advancing our understanding of hormone-immune crosstalk in ovarian cancer.

Background on sex hormones and immune system

Overview of sex hormones

Estrogen and progesterone are key sex hormones that regulate various physiological processes, including reproductive functions, immune responses, and cellular growth, through their respective nuclear receptors: estrogen receptors (ER) and progesterone receptors (PR). These receptors act as transcription factors to modulate gene expression. Estrogen is mainly found in three types: estradiol (E2), estrone (E1), and estriol (E3). Estradiol is the strongest of the three [25–27]. Estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ, are expressed differently across tissues; ERα is primarily found in reproductive tissues, while ERβ has a broader distribution, including the immune system. When estrogen binds to these receptors, they form dimers, move to the nucleus, and bind to estrogen response elements (EREs) in DNA, thus regulating genes involved in cell growth, cell death, and differentiation [28, 29]. Progesterone plays a role in maintaining pregnancy and regulating the menstrual cycle. Progesterone receptors, PR-A and PR-B, differ in their N-terminal regions; PR-A generally represses other hormone receptors, while PR-B activates progesterone-responsive genes. Like estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors bind to PREs in DNA to regulate gene expression [30, 31]. The balance and interaction between PR isoforms are critical for normal reproductive functions and can affect cancer progression.

Estrogen and progesterone are primarily synthesized in the ovaries. Estrogen production begins with cholesterol and involves several enzymatic reactions, with aromatase being a crucial enzyme that converts androgens to estrogens. The hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis regulates estrogen production [32, 33]. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus causes the pituitary gland to release luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). These hormones then stimulate estrogen production in the ovarian follicles. The corpus luteum in the ovary primarily produces progesterone after ovulation. The luteal phase of the menstrual cycle features high progesterone levels, which are vital for preparing the endometrium for a possible pregnancy. If pregnancy does not occur, progesterone levels fall, leading to menstruation. During pregnancy, the placenta becomes progesterone.

Immune system components relevant to cancer

Adaptive immunity is a delayed and specific response that activates lymphocytes that target specific antigens presented by tumor cells [12, 34]. This arm of the immune system has memory capabilities, enabling a quicker and stronger response. The adaptive immune response is crucial for generating long-term immunity and effective tumor eradication. T cells are central to adaptive immunity and are categorized into various subsets. CD8 + cytotoxic T cells destroy tumors by identifying unique antigens shown by MHC class I molecules [35, 36]. These T cells release perforin and granzymes, which induce apoptosis in tumor cells. CD4 + helper T cells support by enhancing the activation and function of other immune cells. CD4 + helper T cells aid in the activation and function of various immune cells. They release cytokines that modulate the immune response. Tregs maintain immune homeostasis and prevent autoimmunity but can also suppress anti-tumor immune responses, facilitating tumor immune evasion [37–39].

NK cells are crucial parts of the innate immune system, able to identify and destroy tumor cells without previous sensitization [40, 41]. They identify stress-induced ligands on tumor cells and induce apoptosis through the release of cytotoxic granules. Additionally, NK cells produce cytokines that affect the adaptive immune response. Macrophages are versatile cells that can display either pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory characteristics. M1 macrophages enhance anti-tumor immunity by releasing inflammatory cytokines and presenting antigens to T cells. In contrast, M2 macrophages facilitate tumor growth and metastasis by promoting tissue remodeling, angiogenesis, and immune suppression [34, 42, 43]. They capture tumor antigens on MHC molecules to T cells, thus initiating an adaptive immune response.

Interaction between sex hormones and the immune system

Sex hormones, especially estrogen and progesterone, greatly influence immune cell function and distribution, causing sex-specific differences in immune responses. Estrogen and progesterone, via their respective receptors, influence the activity and behavior of various immune cells [44, 45]. This modulation shapes the immune landscape in both normal and pathological conditions, including cancer. Differences in immune responses between sexes are partly caused by the unique effects of these hormones [46, 47]. Women typically exhibit stronger immune responses than men, which can be attributed to higher levels of estrogen. This heightened immune reactivity can provide better surveillance against tumors but also increases susceptibility to autoimmune diseases [48, 49]. In ovarian cancer, the interaction between sex hormones and immune regulation is especially complex. The hormonal fluctuations associated with the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause can significantly impact the immune microenvironment of the ovaries, influencing tumor initiation, progression, and response to therapy [50, 51].

Estrogen, the predominant female sex hormone, plays a dual role in immune regulation. It boosts immune surveillance by facilitating the activation and proliferation of diverse immune cells, crucial for detecting and eliminating tumor cells. Estrogen also triggers the production of cytokines and chemokines, which attract immune cells to the tumor site, fostering an anti-tumor immune response. However, estrogen's effect is not exclusively beneficial. It can upregulate immune checkpoint molecules, inhibits T cell activity, allowing tumor cells to escape the immune system. This complexity underscores the importance of considering estrogen’s diverse effects when developing therapeutic strategies for ovarian cancer. Progesterone, another key female sex hormone, generally exerts immunosuppressive effects. Progesterone levels peak during the luteal phase, leading to a temporary reduction in immune activity. This immunosuppressive environment is necessary for pregnancy maintenance but can also facilitate tumor immune evasion. In ovarian cancer, elevated progesterone levels can enhance the differentiation of Tregs and M2 macrophages, both of which inhibit anti-tumor immunity. Progesterone can reduce the activity of cytotoxic T cells and NK cells, creating a microenvironment that supports tumor growth and progression.

The hormonal fluctuations experienced at various stages of a woman’s life significantly complicate the immune landscape in ovarian cancer. Throughout the menstrual cycle, fluctuating estrogen levels result in cyclical shifts in immune activity. Pregnancy, marked by elevated levels of both hormones, induces an immune tolerance state to safeguard the fetus, which can also dampen anti-tumor immunity. Menopause, marked by a decline in estrogen and progesterone, potentially affecting the progression and response of ovarian cancer to therapies. These differences in immune responses between sexes highlight the importance of personalized approaches in treating ovarian cancer. Therapeutic strategies must account for the hormonal status of patients to optimize treatment efficacy. For instance, hormone receptor antagonists or modulators could be combined with immunotherapies to counteract the immunosuppressive effects of estrogen and progesterone, enhancing the overall anti-tumor immune response [52, 53].

Mechanisms of hormonal regulation in ovarian cancer

Estrogen and estrogen receptors (ER)

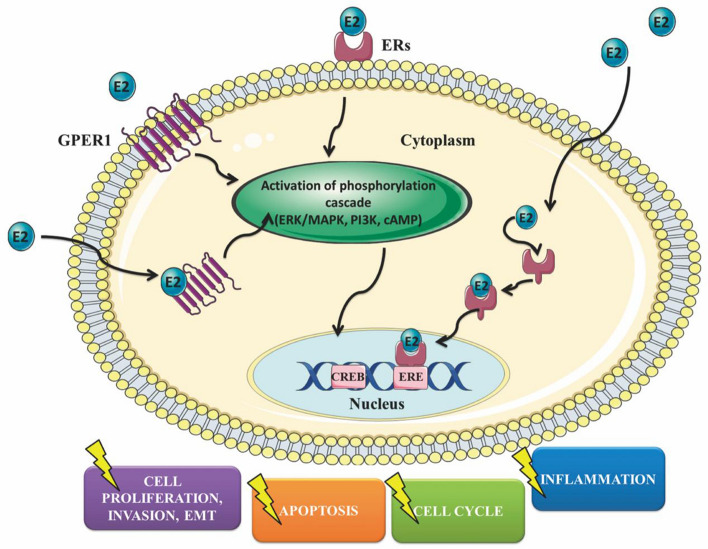

Estrogen, primarily in the form of estradiol (E2), plays a key role in regulating physiological processes such as reproductive functions and cellular proliferation. In ovarian cancer, estrogen signaling significantly influences tumor growth and immune modulation through its interaction with ERs (Fig. 1). Estrogen receptors have two main subtypes: ERα and ERβ. Each subtype has distinct expression patterns and functions in ovarian cancer. ERα is commonly linked to tumor growth and progression. ERα expression have been correlated with increased cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis in ovarian cancer. Conversely, ERβ is generally considered to have a more protective role, with studies suggesting that it may inhibit tumor growth and promote apoptosis. The balance between ERα and ERβ expression is critical in determining the overall impact of estrogen signaling on ovarian cancer development and progression.

Fig. 1.

Primary ways estrogen affects the behavior of ovarian cancer cells

Estrogen affects cells by binding to ERα and ERβ, which function as ligand-activated transcription factors. After binding estrogen, these receptors dimerize and relocate to the nucleus, where they attach to estrogen response elements (EREs) in the DNA. In ovarian cancer, estrogen signaling through ERα promotes tumor growth by increasing the expression of genes related to cell cycle progression and survival, such as cyclin D1 and Bcl-2 [54–56]. This pathway also elevates levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which stimulates the formation of new blood vessels and supports tumor development and spread.

Progesterone and progesterone receptors (PR)

Progesterone is a key sex hormone involved in regulating reproductive functions, including the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. Progesterone influences ovarian cancer through its binding to progesterone receptors (PRs), which function as ligand-activated transcription factors that control gene expression. There are two main isoforms of PR each contributing uniquely to ovarian cancer progression and immune regulation [57]. PR-A and PR-B are different forms produced by the same gene but differ in their N-terminal regions, leading to distinct functional profiles. PR-A mainly functions to inhibit other steroid hormone receptors, thereby modulating their activity. In contrast, PR-B acts as a strong activator of genes responsive to progesterone and is crucial for the complete range of progesterone's biological effects.

In ovarian cancer, the expression levels and balance between PR-A and PR-B can significantly influence tumor behavior. High levels of PR-B are linked to anti-tumor effects, such as inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis [58, 59]. Conversely, PR-A may contribute to tumor progression by repressing the anti-tumor activity of PR-B and other hormone receptors. The dynamic interplay between these isoforms and their downstream signaling pathways is crucial in determining the overall impact of progesterone signaling on ovarian cancer development and progression [60]. Progesterone exerts immunomodulatory effects that can influence ovarian cancer [61]. One of the primary effects of progesterone is the promotion of an immunosuppressive microenvironment, which facilitates tumor immune evasion and progression. Progesterone achieves this by modulating the behavior and function of various immune cells.

Crosstalk between ER and PR pathways

The crosstalk between ER and PR pathways is a critical aspect of hormone signaling in ovarian cancer, influencing both tumor progression and immune regulation. Estrogen and progesterone often exert opposing effects on cellular functions, and their receptors can interact in complex ways to modulate gene expression and cellular behavior. Estrogen and progesterone signaling pathways are interconnected through various molecular mechanisms. ER and PR are part of a larger group of nuclear receptors and can form homo- and heterodimers that attach to particular DNA sequences, controlling the expression of target genes [62, 63]. Estrogen primarily signals through ERα and ERβ, while progesterone signals through PR-A and PR-B. The balance between these receptor subtypes and their respective ligands determines the overall hormonal influence on ovarian cancer cells. Estrogen, acting through ERα, generally promotes cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and tumor growth by upregulating genes involved in these processes [64, 65]. In contrast, progesterone, particularly through PR-B, can inhibit estrogen-induced proliferation and promote apoptosis, exerting a protective effect against tumor progression. However, PR-A can inhibit the function of both ER and PR-B, complicating the hormonal regulation further. The dynamic interplay between these pathways can lead to varying outcomes depending on the comparative levels of ERα, ERβ, PR-A, and PR-B expression in the tumor microenvironment [66].

The interaction between ER and PR pathways extends to ovarian cancer [67]. Estrogen and progesterone can adjust immune cell activity and positioning, affecting the body's overall response to the tumor. Estrogen signaling through ERα can upregulate immune checkpoint molecules, creating an immunosuppressive environment that enables tumor cells to avoid immune detection [68, 69]. Estrogen can also enhance the proliferation and activity of Tregs, which further suppress anti-tumor immunity [70, 71]. Progesterone, signaling through PR, also contributes to immune modulation by promoting the differentiation of Tregs and the transformation of macrophages into the M2 type [72]. These immunosuppressive cells create a tumor-promoting environment by inhibiting cytotoxic T cell activity and enhancing tissue remodeling and angiogenesis. The combined effects of estrogen and progesterone signaling can thus create a highly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment that supports tumor growth and metastasis.

Immune evasion mechanisms mediated by sex hormones

Hormonal modulation of immune checkpoints

The modulation of immune checkpoints by sex hormones is crucial in the immune evasion mechanisms of ovarian cancer. Immune checkpoints are vital regulators of immune responses [73, 74]. While they prevent autoimmunity, they also allow tumor cells to escape immune surveillance. Hormonal signaling, particularly through estrogen and progesterone, significantly influences the expression and regulation of these checkpoints, altering the immune landscape and affecting the efficacy of immunotherapies. PD-1 is an inhibitory receptor found on T cells, while its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, are present on tumor cells and various cells in the tumor microenvironment [75, 76]. When PD-1 interacts with PD-L1, it suppresses T cell activity, diminishing immune monitoring and allowing tumors to evade immune response. Likewise, CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4) functions as an immune checkpoint receptor. It vies with CD28 for binding to B7 molecules (CD80/CD86) on antigen-presenting cells, resulting in decreased T cell activation and growth [77, 78].

Estrogen has been found to increase the levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 in different cancers, including ovarian cancer. This increase happens via estrogen receptors, especially ERα, which directly attach to the promoters of the PD-1 and PD-L1 genes, boosting their transcription [79, 80]. The elevated levels of PD-L1 on tumor cells foster an immunosuppressive environment by blocking the activity of PD-1-expressing T cells, which aids in tumor immune evasion. Additionally, estrogen can affect CTLA-4 expression on T cells, further suppressing anti-tumor immune responses. This hormonal impact on immune checkpoints has important implications for treating ovarian cancer [81, 82].

Impact on cytokine and chemokine networks

Sex hormones, particularly estrogen and progesterone, significantly influence the cytokine and chemokine networks within the ovarian tumor microenvironment. These hormones influence the production and release of various cytokines and chemokines, which are crucial signaling molecules that coordinate immune responses, inflammation, and tumor progression. Estrogen and progesterone control the expression and secretion of these cytokines and chemokines by binding to their respective receptors, ER and PR, which act as transcription factors. Estrogen, through ERα and ERβ, can increase levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α [83–85]. Additionally, estrogen influences the production of chemokines like CCL2 and CXCL12, which recruit immune cells contributing to an immunosuppressive microenvironment [86, 87]. Progesterone, via its receptors PR-A and PR-B, typically has anti-inflammatory effects by reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increasing levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines [88, 89]. These cytokines inhibit the activity of cytotoxic T cells, enhancing tumor immune evasion. Progesterone also regulates the expression of chemokines, which draw Tregs into the tumor microenvironment, further suppressing anti-tumor immunity. The hormonal regulation of cytokine and chemokine networks has significant implications for tumor development and immune escape in ovarian cancer. Estrogen's upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines can create a chronic inflammatory environment that supports tumor proliferation and metastasis. These cytokines can activate STAT3, enhancing the expression of genes related to cell survival, growth, and the formation of new blood vessels.

Therapeutic implications and clinical considerations

Hormone-based therapies

Hormone-based therapies constitute a crucial field in ovarian cancer research, considering the substantial impact of sex hormones on tumor progression and immune regulation. Existing and emerging hormonal treatments are designed to alter the hormonal environment within the tumor, aiming to curb cancer growth and improve therapeutic efficacy. Moreover, there is growing interest in combining hormonal therapies with immunotherapies to leverage their complementary mechanisms of action.

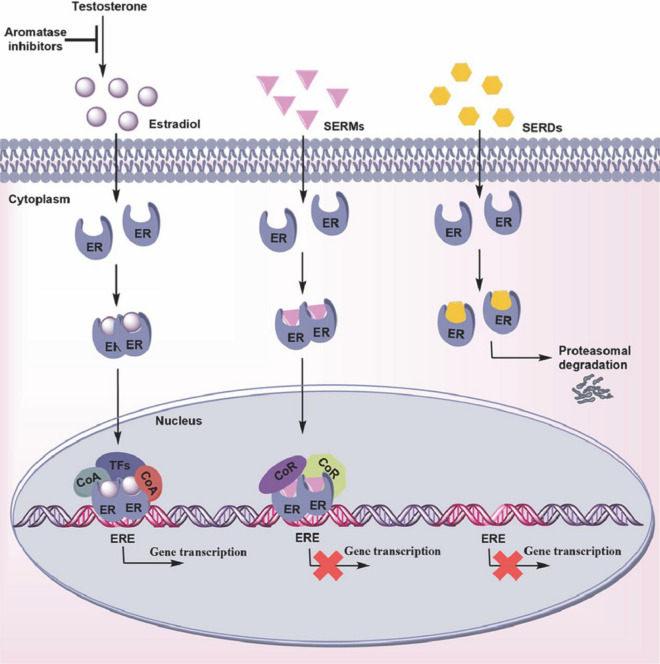

Current hormonal therapies for ovarian cancer primarily focus on targeting estrogen and progesterone pathways. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) like tamoxifen and selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) like fulvestrant are commonly used to block estrogen signaling [90, 91] (Fig. 2). These agents bind to estrogen receptors, preventing estrogen from promoting tumor cell proliferation and survival. Aromatase inhibitors letrozole, reduce the production of estrogen by inhibiting the enzyme aromatase [92, 93]. These therapies are particularly effective in patients with ER-positive ovarian tumors. Progesterone-based therapies involve the use of progestins or synthetic progesterone analogs, which can activate progesterone receptors to exert anti-proliferative effects on ovarian cancer cells. Megestrol acetate and medroxyprogesterone acetate are examples of progestins used in ovarian cancer treatment [94, 95]. Additionally, the development of selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs) offers the potential for more targeted therapeutic effects by selectively modulating PR activity. Emerging therapies are exploring novel targets within the hormone signaling pathways. For instance, dual inhibitors targeting both ER and PR pathways are being investigated to overcome resistance to single-agent therapies. Moreover, advancements in understanding the hormone action in ovarian cancer are driving the development of new agents that can more precisely modulate hormone receptor activity.

Fig. 2.

The effects of endocrine therapies on the estrogen receptor pathway. Endocrine therapies play a pivotal role in the treatment of hormone-sensitive ovarian cancer by targeting the estrogen receptor (ER) pathway. These therapies include aromatase inhibitors, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), and selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs), each of which employs a distinct mechanism to inhibit ER signaling

Combining hormonal therapies with immunotherapies holds promise for enhancing the treatment efficacy in ovarian cancer. Hormonal therapies can modulate the tumor microenvironment, potentially enhancing the effectiveness of immune-based treatments. For example, lowering estrogen levels or disrupting ER signaling with hormonal treatments can diminish the presence of immune checkpoint molecules like PD-L1, thereby boosting the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized cancer therapy by enhancing the immune system's ability to recognize and eliminate cancer cells. In ovarian cancer, ICIs that target PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 have demonstrated potential, though their effectiveness can vary. The impact of sex hormones, especially estrogen and progesterone, on the efficacy of these treatments is an area of ongoing research and clinical interest.

The efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in ovarian cancer has been investigated in numerous clinical trials. ICIs like pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and atezolizumab have shown antitumor activity in certain subsets of ovarian cancer patients [96, 97]. However, the overall response rates have been modest compared to other cancers like melanoma and lung cancer. One reason for this limited efficacy is the inherently immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment of ovarian cancer, characterized by high levels of Tregs, MDSCs, and immunosuppressive cytokines. Combination strategies are being investigated to improve the effectiveness of ICIs in ovarian cancer. These include combining ICIs with chemotherapy, targeted therapies, and other immunomodulatory agents. For example, combining pembrolizumab with bevacizumab (an anti-angiogenic agent) and chemotherapy has shown improved response rates in clinical trials. Additionally, research is focusing on identifying predictive biomarkers to identify patients who are most likely to respond to ICI therapy.

Sex hormones, particularly estrogen and progesterone, greatly affect the tumor microenvironment and how well ICIs work in ovarian cancer. Estrogen can alter the levels of immune checkpoint molecules like PD-1 and PD-L1 through its receptors, ERα and ERβ. Higher estrogen levels are linked to increased PD-L1 expression on both tumor and immune cells, which helps the tumor avoid immune detection and reduces the effectiveness of ICIs targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. Progesterone also influences the immune response to ICIs. By acting on its PR-A and PR-B receptors, progesterone strengthens the immunosuppressive environment by boosting the number and function of Tregs and M2 macrophages. These cells, which have elevated CTLA-4 levels, contribute to the reduced effectiveness of ICIs.

Conclusion

Sex hormones play a significant role in the immune regulation of ovarian cancer. These hormones influence the tumor microenvironment by modulating immune cell function and distribution, cytokine and chemokine production, and the expression of immune checkpoints. Estrogen, acting through its receptors ERα and ERβ, can enhance the immunosuppressive environment by upregulating PD-L1 expression and promoting the activity of Tregs. Progesterone, through its receptors PR-A and PR-B, further contributes to immune evasion by increasing Treg differentiation. The interplay between these hormonal pathways and immune regulation significantly impacts tumor growth, progression, and response to therapies.

Targeted therapies that modulate estrogen and progesterone signaling have the potential to transform the treatment landscape. Hormone-based therapies, such as SERMs and SERDs, and aromatase inhibitors, can reduce estrogen levels or block its receptor activity, thereby diminishing the immunosuppressive effects of estrogen. Similarly, therapies targeting progesterone receptors can mitigate the tumor-promoting effects of progesterone. Combining hormonal therapies with ICIs represents a promising strategy to enhance treatment efficacy. By reducing the hormonal-driven immunosuppression, these combination therapies can improve the immune system's capacity to detect and target tumor cells. Clinical trials investigating these combinations are underway, potentially providing new hope for patients with hormone-sensitive. Moreover, advances in research technologies, particularly multi-omics and single-cell analysis, are providing deeper insights into the intricate relationships between sex hormones and the immune system. Integrating genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data can reveal new biomarkers and pathways that drive hormone-immune interactions in ovarian cancer.

The importance of continued research in this interdisciplinary field cannot be overstated. The complex interplay between sex hormones and immune regulation in ovarian cancer presents both challenges and opportunities for advancing cancer treatment. Continued investigation into the molecular mechanisms underlying these interactions is essential for developing novel therapies that can effectively target hormone-driven immune evasion. Collaboration across disciplines, including oncology, immunology, endocrinology, and bioinformatics, is crucial for accelerating progress in this field. Combining insights from these different fields can enhance our understanding of ovarian cancer biology and lead to the creation of novel treatment strategies. Furthermore, translating research findings into clinical practice requires robust clinical trials and real-world studies to validate the efficacy and safety of new treatments. Engaging patients in clinical research and incorporating their experiences and outcomes into the development of personalized therapies is vital for achieving meaningful advancements in cancer care.

In summary, the impact of sex hormones on immune regulation in ovarian cancer is a key research area with important clinical consequences. By leveraging advances in research technologies and adopting personalized medicine approaches, we can improve the understanding and treatment of this complex disease. Continued interdisciplinary research efforts will be essential for developing targeted therapies that can enhance patient outcomes and ultimately, reduce the burden of ovarian cancer.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Guangdong Medical Science and Technology Research Foundation (202252714418515).

Author contributions

Qiong Xu concepted the manuscript. Rui Zhao and Wenqin Lian wrote the main manuscript text and Wenqin Lian prepared Figs. 1, 2. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rui Zhao and Wenqin Lian have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Wenqin Lian, Email: lianwenqin1991@yeah.net.

Qiong Xu, Email: xuqiong-fy@163.com.

References

- 1.Cho KR, Shih IM. Ovarian cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:287–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konstantinopoulos PA, Matulonis UA. Clinical and translational advances in ovarian cancer therapy. Nat Cancer. 2023;4(9):1239–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenhauer EA. Real-world evidence in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_8):61–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barua A, Bahr JM. Ovarian cancer: applications of chickens to humans. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2022;10:241–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colombo N, et al. ESMO-ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours and recurrent disease†. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(5):672–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jayson GC, et al. Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2014;384(9951):1376–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SI, Kim JW. Role of surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. ESMO Open. 2021;6(3): 100149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorgensen K, et al. Minimally invasive interval debulking surgery for advanced ovarian cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2023;172:130–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang C, et al. Immunotherapy for ovarian cancer: adjuvant, combination, and neoadjuvant. Front Immunol. 2020;11: 577869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morand S, et al. Ovarian cancer immunotherapy and personalized medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(12):6532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lheureux S, Braunstein M, Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian cancer: evolution of management in the era of precision medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(4):280–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang Y, Wang C, Zhou S. Targeting tumor microenvironment in ovarian cancer: premise and promise. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020;1873(2): 188361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoutrop E, et al. Molecular, cellular and systemic aspects of epithelial ovarian cancer and its tumor microenvironment. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;86(Pt 3):207–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan Z, et al. Ovarian cancer treatment and natural killer cell-based immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1308143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, et al. Human iPSC-derived natural killer cells engineered with chimeric antigen receptors enhance anti-tumor activity. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23(2):181-192.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curiel TJ, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10(9):942–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mondal T, et al. Characterizing the regulatory Fas (CD95) epitope critical for agonist antibody targeting and CAR-T bystander function in ovarian cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2023;30(11):2408–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks ZRC, et al. Interferon-ε is a tumour suppressor and restricts ovarian cancer. Nature. 2023;620(7976):1063–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao L, et al. Strategies to synergize PD-1/PD-L1 targeted cancer immunotherapies to enhance antitumor responses in ovarian cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023;215: 115724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higuchi T, et al. CTLA-4 blockade synergizes therapeutically with PARP inhibition in BRCA1-deficient ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3(11):1257–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duraiswamy J, et al. Dual blockade of PD-1 and CTLA-4 combined with tumor vaccine effectively restores T-cell rejection function in tumors. Cancer Res. 2013;73(12):3591–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho SM. Estrogen, progesterone and epithelial ovarian cancer. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeon SY, Hwang KA, Choi KC. Effect of steroid hormones, estrogen and progesterone, on epithelial mesenchymal transition in ovarian cancer development. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;158:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fournier A, et al. Use of menopausal hormone therapy and ovarian cancer risk in a French cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2023;115(6):671–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimizu Y, Yanaihara T. Estrogen: estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), estriol (E3) and estetrol (4). Nihon Rinsho. 1999;57:252–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tulchinsky D, et al. Plasma estrone, estradiol, estriol, progesterone, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone in human pregnancy. I. Normal pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;112(8):1095–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, et al. Trimester-specific, gender-specific, and low-dose effects associated with non-monotonic relationships of bisphenol A on estrone, 17β-estradiol and estriol. Environ Int. 2020;134: 105304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klinge CM. Estrogen receptor interaction with estrogen response elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(14):2905–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gruber CJ, et al. Anatomy of the estrogen response element. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15(2):73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garg D, et al. Progesterone-mediated non-classical signaling. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28(9):656–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamian V, et al. Non-consensus progesterone response elements mediate the progesterone-regulated endometrial expression of the uteroferrin gene. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;46(4):439–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oyola MG, Handa RJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axes: sex differences in regulation of stress responsivity. Stress. 2017;20(5):476–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cutolo M, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical and gonadal functions in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;992:107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding L, et al. PARP inhibition elicits STING-dependent antitumor immunity in Brca1-deficient ovarian cancer. Cell Rep. 2018;25(11):2972-2980.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chovatiya N, et al. Inability of ovarian cancers to upregulate their MHC-class I surface expression marks their aggressiveness and increased susceptibility to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2022;71(12):2929–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lulu AM, et al. Characteristics of immune memory and effector activity to cancer-expressed MHC class I phosphopeptides differ in healthy donors and ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Res. 2021;9(11):1327–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vinay DS, et al. Immune evasion in cancer: mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35(Suppl):S185-s198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaurio RA, et al. TGF-β-mediated silencing of genomic organizer SATB1 promotes Tfh cell differentiation and formation of intra-tumoral tertiary lymphoid structures. Immunity. 2022;55(1):115-128.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toker A, et al. Regulatory T cells in ovarian cancer are characterized by a highly activated phenotype distinct from that in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(22):5685–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raja R, et al. PP4 inhibition sensitizes ovarian cancer to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity via STAT1 activation and inflammatory signaling. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10(12): e005026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wan C, et al. Enhanced efficacy of simultaneous PD-1 and PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2021;81(1):158–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duraiswamy J, et al. Myeloid antigen-presenting cell niches sustain antitumor T cells and license PD-1 blockade via CD28 costimulation. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(12):1623-1642.e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pawłowska A, et al. Clinical and Prognostic Value of Antigen-Presenting Cells with PD-L1/PD-L2 Expression in Ovarian Cancer Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ysrraelit MC, Correale J. Impact of sex hormones on immune function and multiple sclerosis development. Immunology. 2019;156(1):9–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dunn SE, Perry WA, Klein SL. Mechanisms and consequences of sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2024;20(1):37–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cortes CJ, De Miguel Z. Precision exercise medicine: sex specific differences in immune and CNS responses to physical activity. Brain Plast. 2022;8(1):65–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scott SC, et al. Sex-specific differences in immunogenomic features of response to immune checkpoint blockade. Front Oncol. 2022;12: 945798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park HJ, Choi JM. Sex-specific regulation of immune responses by PPARs. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49(8): e364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta M, et al. Genetic and hormonal mechanisms underlying sex-specific immune responses in tuberculosis. Trends Immunol. 2022;43(8):640–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wardhani K, et al. Systemic immunological responses are dependent on sex and ovarian hormone presence following acute inhaled woodsmoke exposure. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2024;21(1):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiong SP, et al. PD-L1 expression, morphology, and molecular characteristic of a subset of aggressive uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor and a literature review. J Ovarian Res. 2023;16(1):102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chou J, et al. Transcription-associated cyclin-dependent kinases as targets and biomarkers for cancer therapy. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(3):351–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perez-Lanzon M, et al. New hormone receptor-positive breast cancer mouse cell line mimicking the immune microenvironment of anti-PD-1 resistant mammary carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11(6): e007117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen C, et al. Leptin stimulates ovarian cancer cell growth and inhibits apoptosis by increasing cyclin D1 and Mcl-1 expression via the activation of the MEK/ERK1/2 and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Int J Oncol. 2013;42(3):1113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rzeski W, et al. Betulinic acid decreases expression of bcl-2 and cyclin D1, inhibits proliferation, migration and induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2006;374(1):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aguirre D, et al. Bcl-2 and CCND1/CDK4 expression levels predict the cellular effects of mTOR inhibitors in human ovarian carcinoma. Apoptosis. 2004;9(6):797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sletten ET, et al. Significance of progesterone receptors (PR-A and PR-B) expression as predictors for relapse after successful therapy of endometrial hyperplasia: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2019;126(7):936–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mauro LJ, et al. Progesterone receptors promote quiescence and ovarian cancer cell phenotypes via DREAM in p53-mutant fallopian tube models. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(7):1929–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diep CH, Mauro LJ, Lange CA. Navigating a plethora of progesterone receptors: comments on the safety/risk of progesterone supplementation in women with a history of breast cancer or at high-risk for developing breast cancer. Steroids. 2023;200: 109329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jongen V, et al. Expression of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta and progesterone receptor-A and -B in a large cohort of patients with endometrioid endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(3):537–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mukherjee K, Syed V, Ho SM. Estrogen-induced loss of progesterone receptor expression in normal and malignant ovarian surface epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2005;24(27):4388–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tong D. Selective estrogen receptor modulators contribute to prostate cancer treatment by regulating the tumor immune microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10(4): e002944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Piperigkou Z, Karamanos NK. Estrogen receptor-mediated targeting of the extracellular matrix network in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;62:116–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reid SE, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts rewire the estrogen receptor response in luminal breast cancer, enabling estrogen independence. Oncogene. 2024;43(15):1113–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bado I, et al. Estrogen receptors in breast and bone: from virtue of remodeling to vileness of metastasis. Oncogene. 2017;36(32):4527–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chakraborty B, et al. Estrogen receptor signaling in the immune system. Endocr Rev. 2023;44(1):117–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Si S, et al. Identifying causality, genetic correlation, priority and pathways of large-scale complex exposures of breast and ovarian cancers. Br J Cancer. 2021;125(11):1570–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu CJ, et al. Loss of LECT2 promotes ovarian cancer progression by inducing cancer invasiveness and facilitating an immunosuppressive environment. Oncogene. 2024;43(7):511–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Flies DB, et al. Immune checkpoint blockade reveals the stimulatory capacity of tumor-associated CD103(+) dendritic cells in late-stage ovarian cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(8): e1185583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ishikawa A, et al. Estrogen regulates sex-specific localization of regulatory T cells in adipose tissue of obese female mice. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4): e0230885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Offner H, Vandenbark AA. Congruent effects of estrogen and T-cell receptor peptide therapy on regulatory T cells in EAE and MS. Int Rev Immunol. 2005;24(5–6):447–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aryanpour R, et al. Progesterone therapy induces an M1 to M2 switch in microglia phenotype and suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome in a cuprizone-induced demyelination mouse model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;51:131–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu L, et al. Expression of programmed death-1 (PD-1) and its ligand PD-L1 is upregulated in endometriosis and promoted by 17beta-estradiol. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2019;35(3):251–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodriguez-Lara V, et al. Role of sex and sex hormones in PD-L1 expression in NSCLC: clinical and therapeutic implications. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1210297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karami S, et al. Evaluating the possible association between PD-1 (Rs11568821, Rs2227981, Rs2227982) and PD-L1 (Rs4143815, Rs2890658) polymorphisms and susceptibility to breast cancer in a sample of Southeast Iranian women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21(10):3115–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Asano Y, et al. Prediction of treatment responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer by analysis of immune checkpoint protein expression. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bagbudar S, et al. Prognostic implications of immune infiltrates in the breast cancer microenvironment: the role of expressions of CTLA-4, PD-1, and LAG-3. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2022;30(2):99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li D, et al. Association of CTLA-4 gene polymorphisms with sporadic breast cancer risk and clinical features in Han women of northeast China. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;364(1–2):283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang W, Chen L, Sun P. ERRα expression in ovarian cancer and promotes ovarian cancer cells migration in vitro. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;305(6):1525–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schüler-Toprak S, et al. Role of estrogen receptor β, G-protein coupled estrogen receptor and estrogen-related receptors in endometrial and ovarian cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(10):2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cunat S, Hoffmann P, Pujol P. Estrogens and epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94(1):25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schüler-Toprak S, et al. Estrogen receptor β is associated with expression of cancer associated genes and survival in ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jiang X, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depression is associated with estrogen receptor-α/SIRT1/NF-κB signaling pathway in old female mice. Neurochem Int. 2021;148: 105097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stanojević S, et al. The involvement of estrogen receptors α and β in the in vitro effects of 17β-estradiol on secretory profile of peritoneal macrophages from naturally menopausal female and middle-aged male rats. Exp Gerontol. 2018;113:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bodine PV, Harris HA, Komm BS. Suppression of ligand-dependent estrogen receptor activity by bone-resorbing cytokines in human osteoblasts. Endocrinology. 1999;140(6):2439–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.He M, et al. Estrogen receptor α promotes lung cancer cell invasion via increase of and cross-talk with infiltrated macrophages through the CCL2/CCR2/MMP9 and CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling pathways. Mol Oncol. 2020;14(8):1779–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Potter SM, et al. Systemic chemokine levels in breast cancer patients and their relationship with circulating menstrual hormones. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115(2):279–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nejatbakhsh Samimi L, et al. The impact of 17β-estradiol and progesterone therapy on peripheral blood mononuclear cells of asthmatic patients. Mol Biol Rep. 2021;48(1):297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kabel AM, et al. The promising effect of linagliptin and/or indole-3-carbinol on experimentally-induced polycystic ovarian syndrome. Chem Biol Interact. 2017;273:190–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Patel HK, Bihani T. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) and selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) in cancer treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;186:1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Prossnitz ER, Barton M. The G protein-coupled oestrogen receptor GPER in health and disease: an update. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023;19(7):407–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Augusto TV, et al. Acquired resistance to aromatase inhibitors: where we stand! Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(5):R283-r301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu T, Huang Y, Lin H. Estrogen disorders: interpreting the abnormal regulation of aromatase in granulosa cells (review). Int J Mol Med. 2021;47(5):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schacter L, et al. Megestrol acetate: clinical experience. Cancer Treat Rev. 1989;16(1):49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Markman M, et al. Phase I trial of paclitaxel plus megestrol acetate in patients with paclitaxel-refractory ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(11):4201–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zsiros E, et al. Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab in combination with bevacizumab and oral metronomic cyclophosphamide in the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer: a phase 2 nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(1):78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hamanishi J, et al. Nivolumab versus gemcitabine or pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer: open-label, randomized trial in Japan (NINJA). J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(33):3671–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.