Abstract

Background and Aims

Previous phylogenetic studies on the pharmaceutically significant genus Paris (Melanthiaceae) have consistently revealed substantial cytonuclear discordance, yet the underlying mechanism responsible for this phenomenon remains elusive. This study aims to reconstruct a robust nuclear backbone phylogeny and elucidate the potential evolutionarily complex events contributing to previously observed cytonuclear discordance within Paris.

Methods

Based on a comprehensive set of nuclear low-copy orthologous genes obtained from transcriptomic data, the intrageneric phylogeny of Paris, along with its phylogenetic relationships to allied genera, were inferred using coalescent and concatenated approaches. The analysis of gene tree discordance and reticulate evolution, in conjunction with an incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) simulation, was conducted to explore potential hybridization and ILS events in the evolutionary history of Paris and assess their contribution to the discordance of gene trees.

Key Results

The nuclear phylogeny unequivocally confirmed the monophyly of Paris and its sister relationship with Trillium, while widespread incongruences in gene trees were observed at the majority of internal nodes within Paris. The reticulate evolution analysis identified five instances of hybridization events in Paris, indicating that hybridization events might have occurred recurrently throughout the evolutionary history of Paris. In contrast, the ILS simulations revealed that only two internal nodes within section Euthyra experienced ILS events.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that the previously observed cytonuclear discordance in the phylogeny of Paris can primarily be attributed to recurrent hybridization events, with secondary contributions from infrequent ILS events. The recurrent hybridization events in the evolutionary history of Paris not only drove lineage diversification and speciation but also facilitated morphological innovation, and enhanced ecological adaptability. Therefore, artificial hybridization has great potential for breeding medicinal Paris species. These findings significantly contribute to our comprehensive understanding of the evolutionary complexity of this pharmaceutically significant plant lineage, thereby facilitating effective exploitation and conservation efforts.

Keywords: Hybridization, incomplete lineage sorting, lineage diversification, phylogenomics, speciation

INTRODUCTION

Plants possess three sets of genomes, i.e. a nuclear genome, a chloroplast genome and a mitochondrial genome (Qiu et al., 1999). During the integration of DNA sequences from nuclear and cytoplasmic (chloroplast and mitochondrial) genomes for phylogenetic analyses over the past few decades, significant discrepancies in phylogenetic relationships between nuclear and cytoplasmic datasets (referred to as ‘cytonuclear discordance’), particularly concerning tree topological incongruences, have been consistently observed across a wide range of angiosperm lineages (e.g. Smith and Sytsma, 1990; Brunsfeld et al., 1992; Soltis et al., 1996; McKinnon et al., 1999; Rokas et al., 2003; Acosta and Premoli, 2010; Sun et al., 2015). Recently, with the increasing application of genome-scale sequence data in unravelling historical phylogenetic uncertainties, a series of previously undiscovered cytonuclear discordances have been progressively revealed (e.g. Bruun-Lund et al., 2017; Morales-Briones et al., 2018; Stull et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022; Ding et al., 2023; Guo et al., 2023; Hu et al., 2023; Ji et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2023; Jia et al., 2024; Zhou et al., 2024). The prevalence of cytonuclear discordances in plant phylogenetics suggests the existence of distinct and potentially divergent evolutionary histories for nuclear and cytoplasmic genomes in relevant plant taxa (Folk et al., 2017, 2018; Koenen et al., 2020; Stull et al., 2020; Gardner et al., 2023; Guo et al., 2023; Hu et al., 2023).

The phylogenetic relationships inferred from cytoplasmic and nuclear genome data may exhibit incongruence as a result of various evolutionary processes. For instance, rapid radiative diversification in plant lineages with large effective population sizes may result in the stochastic inheritance of polymorphic ancestral genotypes in diverged descendants, a phenomenon known as incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), subsequently leading to cytonuclear discordances in phylogenetic relationships (Maddison, 1997; Joly, 2009; Sambatti et al., 2012; Salichos and Rokas, 2013; Mirarab et al., 2016). Additionally, unlike biparentally inherited nuclear genomes, uniparentally inherited cytoplasmic genomes typically lack recombination and segregation (Wendel and Doyle, 1998; Qiu et al., 1999). The process of hybridization and subsequent backcrossing likely results in cytoplasmic introgression, where the chloroplast or mitochondrial genomes of one parent (usually the maternal parent) become fixed in the hybrid progenies (Rieseberg et al., 1990; Wolfe and Elisens, 1995; Acosta and Premoli, 2010; Joly et al., 2012). The distinct evolutionary histories of cytoplasmic genomes in hybrid progenies likely contribute to different phylogenetic relationships between genes from the cytoplasmic and nuclear genomes (Rieseberg and Soltis, 1991; Soltis and Kuzoff, 1995; Tsitrone et al., 2003; Garcia et al., 2017; Stull et al., 2023). Due to the presence of similar topological conflicts resulting from both ILS and hybridization-induced cytoplasmic introgression, previous phylogenetic studies have encountered challenges in elucidating the underlying evolutionary events contributing to observed cytonuclear discordance (Duan et al., 2023; Stull et al., 2023).

The monocotyledonous genus Paris, currently classified within the family Melanthiaceae in the order Liliales (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, 1998), exhibits distinctive morphological characteristics. Among angiosperms, Paris species are distinguished by the emergence of a solitary flower from a whorl of net-veined (4–15) leaves at the apex of the stem, contrasting with its sister genus Trillium, which displays a trimerous condition (Linnaeus, 1753). In addition to its distinctive morphology, the genus Paris is unique among angiosperms due to its possession of large genomes: the minimum documented genome size in the genus (Paris bashanensis, 1C = 29.38 pg; Ji, 2021) significantly surpasses the average genome size observed in angiosperms (Leitch et al., 2010; Pellicer et al., 2014), and P. japonica, which holds the largest known eukaryotic genomes (1C = 148.88 pg; Pellicer et al., 2010; Dodsworth et al., 2015), belongs to this genus (Yang et al., 2019a). Paris also represents a plant lineage of significant pharmaceutical importance due to possessing diverse therapeutic properties. Within this genus, the majority of species with thick rhizomes have long been utilized as traditional medicinal herbs in China, the Himalayas and Northern Indochina for the treatment of various diseases (Cunningham et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019b; Ding et al., 2021; Ji, 2021). To date, more than 200 secondary metabolites, including steroidal saponins, phytoecdysones, flavonoids and triterpenoid saponins, have been isolated and identified from these medicinal Paris species (Ding et al., 2021; Ji, 2021). Among them, steroidal saponins are the predominant biologically active ingredients owing to their significant haemostatic (Gong et al., 2012; Qin et al., 2016, 2018), antimicrobial (Deng et al., 2008; Qin et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2019) and anti-tumour (Sun et al., 2007; Xie et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018b) properties. In China alone, around 92 commercial drugs and health products have been developed, utilizing the processed rhizomes of medicinal Paris species as their primary raw materials (Ji, 2021; Miao et al., 2024).

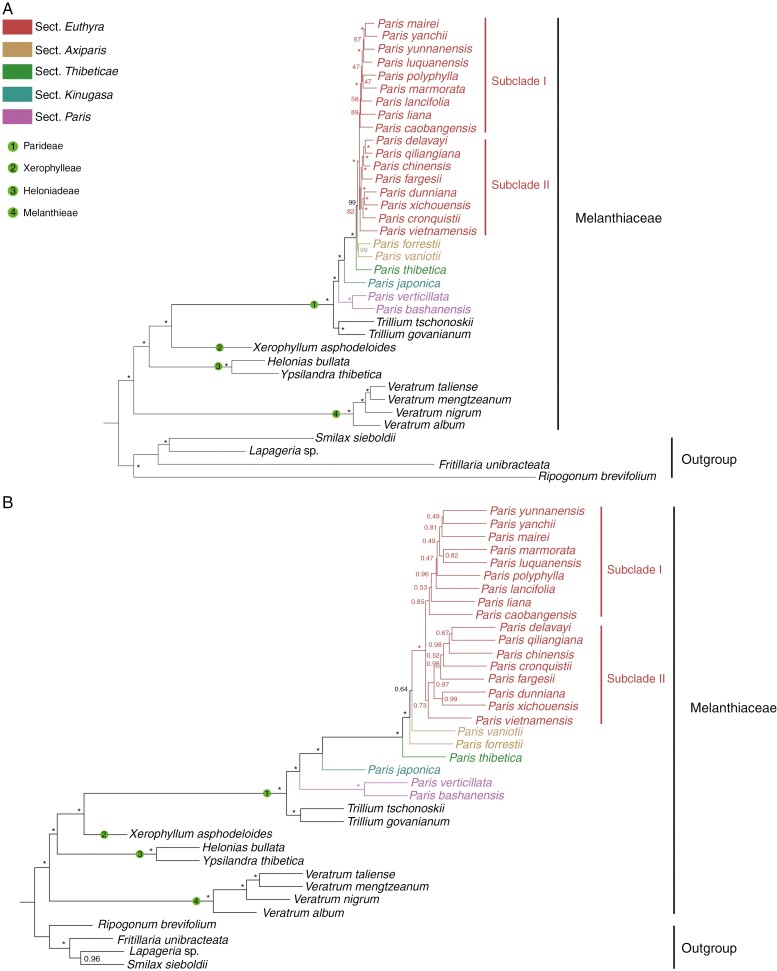

According to the latest and most comprehensive taxonomic revision by Ji (2021), the genus Paris comprises 26 species of rhizomatous herbaceous perennials with a wide geographic distribution across temperate and subtropical regions of Eurasia, with the majority of species occurring in China and the Himalayas (Li, 1998; Liang and Soukup, 2000; Ji, 2021; Miao et al., 2024). Based on integrating phylogenetic inferences and morphological characteristics, the extant classification recognizes five sections within this genus, namely, sect. Axiparis, sect. Euthyra, sect. Kinugasa, sect. Paris and sect. Thibeticae (Ji, 2021). Although previous molecular phylogenetic studies consistently resolved each section as monophyletic, significant incongruences between plastid and nuclear tree topologies were also observed (Fig. 1), suggesting that potential hybridization or ILS events might have occurred in the evolutionary history of Paris (Ji et al., 2006, 2019, 2022; Ji, 2021). Notably, previous phylogenetic analyses utilized either internal transcriptional spacers (ITS) or nuclear ribosomal DNA (nrDNA) arrays to infer nuclear phylogeny. Given the potential for rapid concerted evolution towards a single parental copy (gene conversion) in ITS and nrDNA arrays (Hillis et al., 1991; Wendel et al., 1995; Lim et al., 2000; Kovarik et al., 2005), analysing the sequence data poses challenges in elucidating the underlying mechanisms responsible for previously observed cytonuclear discordance in Paris phylogeny. Given the substantial economic significance of Paris, resolving this issue will not only enhance our comprehension of the evolutionary history of the genus but also facilitate a rational exploitation and utilization of medicinal Paris species.

Fig. 1.

(A) Phylogeny of Paris and allied genera within the family Melanthiaceae reconstructed by analyses of complete plastomes using the maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference methods; numbers above branches indicate maximum likelihood bootstrap percentages and Bayesian posterior probabilities. (B) Comparison of tree topologies recovered from analyses of nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences (left) and complete plastomes (right); numbers above branches indicated maximum likelihood bootstrap percentages and Bayesian posterior probabilities.

The objectives of the current study were to (1) reconstruct a robust nuclear backbone phylogeny of the genus Paris, and (2) infer potential evolutionary processes that might have contributed to previously observed cytonuclear discordance in this genus. To achieve these goals, we employed concatenated and coalescent approaches to recover intrageneric phylogenetic relationships of Paris, as well as its phylogenetic associations with allied genera within the family Melanthiaceae, by utilizing a comprehensive set of nuclear low-copy orthologous genes obtained from transcriptomic data. Additionally, we investigated the extent of discordance among nuclear gene trees to explore potential hybridization and ILS events in the evolutionary history of Paris, thereby evaluating their contribution to gene tree discordance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Taxonomic sampling, RNA sequencing and transcriptome assembly

To recover a robust nuclear backbone phylogeny of the genus Paris and elucidate its relationships with allied genera, our taxonomic sampling encompassed representatives from all five currently recognized sections within the genus, as well as representatives from other five Melanthiaceae genera. A total of 36 samples, representing 32 ingroup and four outgroup species, were included in the phylogenetic analysis. Among these, RNA sequencing was conducted for 26 Melanthiaceae species (22 Paris species, 1 Trillium species, 1 Ypsilandra species and 2 Veratrum species) in this study (Supplementary Data Table S1). The remaining transcriptome data of six ingroup (Melanthiaceae) and four outgroup species were obtained from the publicly available NCBI sequence read archive (SRA: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) and the one thousand plant transcriptome database (https://db.cngb.org/onekp) (Supplementary Data Table S2).

For those species newly sequenced in this study (Supplementary Data Table S1), living plants were collected from their natural habitats and subsequently cultivated under controlled greenhouse conditions. Four distinct tissue types (flowers, leaves, stems and underground rhizomes) were harvested from each individual plant and combined for RNA extraction. These materials were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen followed by cryogenic preservation at −80 °C until RNA extraction. For each sample, the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) was employed to extract total RNA from mixed tissues, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Subsequently, the AU-mRNAseq Library Prep Kit (Tecan, CA, USA) was utilized to prepare the RNA sequencing library according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Paired-end sequencing with a read length of 150 bp was conducted on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, yielding ~6 Gb of raw reads per sample.

The software Trimmomatic v0.39 (Bolger et al., 2014) was utilized to eliminate low-quality reads (Phred score < 20) and remove adaptors from the raw sequencing data, employing pre-set parameters. Next, reads from chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes were filtered using Bowtie 2 v2.5.1 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) by aligning them with the cytoplasmic genome sequences of Paris yunnanensis. De novo assembly of the filtered RNA sequencing reads into transcripts was performed using Trinity v2.5.1 (Grabherr et al., 2011; Haas et al., 2013), with default parameter settings. The quality assessment of the transcriptome assembly was conducted using Transrate v1.0.3 (Smith-Unna et al., 2016). The identification and translation of coding sequences from assembled transcripts were performed utilizing the online tool Transdecoder v5.3.0 (Haas et al., 2013), and coding sequences with a length <300 bp were excluded from subsequent analysis. Subsequently, cd-hit v4.7 (Li and Godzik, 2006) was applied to remove redundant transcripts with a parameter setting of -c 0.99-n 10.

Identification of low-copy nuclear orthologous genes

Orthology inference was performed using the pipeline developed by Yang and Smith (2014). Initially, an all-by-all screening of coding sequences was conducted by BLASTN v2.9.0 (Camacho et al., 2009) with the following parameter settings: max target seqs = 1000; evalue = 10. Subsequently, putative gene families were clustered using MCL v14-137 (Dongen, 2008), and clusters comprising <20 species were excluded by setting a hit fraction threshold set of 0.4. Retained homologue clusters were independently aligned using MAFFT v7.149b (Katoh and Standley, 2013), and poorly aligned regions (with >90 % missing data) in each matrix were removed using Phyx v1.3 (Brown et al., 2017), with a threshold setting at 0.1. Subsequently, RAxML v8.2.12 (Stamatakis, 2014) was employed to construct the homologous gene trees with the GTR + GAMMA model and 100 rapid bootstrap replicates. Based on phylogenetic tree topologies inferred from these analyses, TreeShrink v1.3.2 (Mai et al., 2018) was employed to detect and remove paralogous genes as well as multiple-copy orthologous genes among the 36 species, yielding a gene dataset with 528 low-copy orthologues for subsequent analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis

Both concatenated and coalescent methods were employed for phylogenetic analysis. The 528 low-copy orthologues were individually aligned using MAFFT v7.149b (Katoh and Standley, 2013), followed by concatenation into a super-matrix using PhyloSuite v1.2.2 (Zhang et al., 2020). Optimal partitioning schemes and sequence substitution models were determined using PartitionFinder v2.1.1 (Lanfear et al., 2017). Based on the concatenated super-matrix, IQ-TREE 2 v2.1.3 (Minh et al., 2020) was utilized to perform the maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis with 1000 ultrafast bootstrap (UFBS) replicates.

For the reconstruction of coalescent phylogeny, individual gene trees were reconstructed for each of the 528 low-copy orthologous genes using RAxML v8.2.11 (Stamatakis, 2014) with 1000 rapid bootstrap (BS) replicates and the GTR + GAMMA sequence substitution model. Each gene tree was rooted, and subsequently merged into a single file for inferring the coalescent phylogeny with ASTRAL-III v5.7 (Zhang et al., 2018a), and the local posterior probability (LPP) was employed to evaluate branch support. Additionally, the nodes displaying low support (BS values <10%) were collapsed for each gene tree using Newick v1.6.0 (Junier et al., 2010). The implementation of this collapsing strategy was based on empirical evidence, suggesting that the removal of nodes with BS values below this threshold value can enhance the accuracy of coalescent phylogeny; conversely, an excessive number of filtered nodes with BS values exceeding the threshold is likely to result in reduced accuracy (Zhang et al., 2018a).

Identification of gene tree discordance

The extent of discordance among gene trees was evaluated using Phyparts (Smith et al., 2015) by comparing the gene trees with the species tree inferred from coalescent phylogeny. To more accurately determine the proportion of low-copy orthologous genes that support or conflict with individual bipartitions within the species tree, a BS threshold of 50 was applied to filter poorly supported gene tree branches/nodes (i.e. exhibiting a BS value <50 %) in each gene tree, as branch/node support <50 % BS was regarded as uninformative (Smith et al., 2015). The results of Phyparts analysis were visualized with phypa-strpiecharts.py (https://github.com/mossmatters/phyloscripts).

Reticulate evolution analysis and ILS simulations

In order to mitigate computational resource constraints and expedite the analysis runtime, a subset consisting of 23 Paris species and 2 Trillium species was selected to infer potential hybridization and ILS events in the evolutionary history of Paris. Following the methodology outlined above in the section ‘Identification of low-copy nuclear orthologous genes’, a total of 1189 low-copy nuclear orthologous genes were identified among these species. Inferred from the dataset, the reticulate evolution analysis was conducted using the maximum pseudolikelihood estimation of phylogenetic networks algorithm (Yu and Nakhleh, 2015) implemented in PhyloNetworks v3.8.2 (Than et al., 2008). The maximum number of hybridizations was pre-set as five to determine the optimal hybridization number based on the lowest cross-validation error rate. Dendroscope v3.8.5 (Huson and Scornavacca, 2012) was employed to visualize the results of reticulate evolution analysis.

Concatenated and coalescent phylogenies were constructed using IQ-TREE 2 v2.1.3 (Minh et al., 2020) and ASTRAL-III v5.7 (Zhang et al., 2018a) based on the 1189 nuclear orthologous genes, to obtain branch length data for simulating ILS. The θ parameter of each node in the tree topologies was estimated by dividing the branch length inferred by IQ-TREE (mutation units) with that inferred by ASTRAL (coalescent units). Higher θ values indicate larger ancestral effective population sizes, suggesting increased likelihood of ILS during cladogenesis, thereby reflecting different levels of ILS for each node (Cai et al., 2021). Simulations of gene trees under the multispecies coalescent model were performed using the algorithm sim.coaltree.sp implemented in the R package Phybase v. 1.5 (Liu and Yu, 2010), generating a total of 100 000 gene trees per simulation. Topological frequencies for observed and simulated gene trees were calculated using ASTRAL-III v5.7.8 (Zhang et al., 2018a) with parameter -t8, followed by calculation of the correlation coefficient between them using the cor.test algorithm in the package. If the simulated gene trees under the ILS condition demonstrate a considerable agreement with the empirical gene trees, it is plausible to attribute the discordance in gene trees to ILS (Cai et al., 2021).

RESULTS

Transcriptome assembly

Based on the RNA-seq data newly generated in this study and those obtained from publicly available databases, the Trinity transcriptome assembly yielded a range of 38 419–537 146 transcripts per sample, with an average length spanning between 493 and 1228 bp. The N50 lengths of these transcripts ranged from 81 to 1825 bp, while the guanine and cytosine (GC) content exhibited a variation between 43.44 and 48.86 % (Supplementary Data Table S3).

Phylogenetic relationships

The orthology reference generated a dataset comprising 528 low-copy orthologous genes for phylogenetic analysis (the features of each individual gene matrix are displayed in Supplementary Data Table S4), based on the transcriptome assembly of 36 species sampled in this study. The monophyly of Paris, as well as the sister relationship between Paris and Trillium, was strongly supported by both the concatenated and coalescent phylogenies, with UFBS = 100 % and LPP = 1.00 (Fig. 2). Within the genus Paris, the concatenated phylogeny (Fig. 2A) strongly supported (UFBS > 95%) the monophyly of all five sections delineated by Ji (2021), indicating a successive divergence of sect. Paris, sect. Kinugasa, sect. Thibeticae, sect. Axiparis and sect. Euthyra with robust node support (UFBS > 95 %). Although two topologies exhibited identical relationships among sect. Paris, sect. Kinugasa and sect. Thibeticae with strong support, the coalescent phylogeny (Fig. 2B) recovered successive sister relationships among P. forrestii, P. vaniotii and sect. Euthyra; consequently, it failed to resolve the monophyly of sect. Axiparis. Additionally, both concatenated and coalescent phylogenies consistently grouped species of sect. Euthyra into two well-supported subclades (UFBS = 100 %, LPP = 1.00). Nevertheless, the majority of interspecific relationships within sect. Axiparis and sect. Euthyra exhibited low support in both concatenated and coalescent phylogenies (UFBS < 95 %, LPP < 0.90), indicating a lake of phylogenetic information in certain orthologous genes (Minh et al., 2013).

Fig. 2.

Concatenated (A) and coalescent (B) phylogenies of Paris and allied genera based on analysis of 528 nuclear orthologous genes obtained from transcriptome data. Numbers near the nodes represent UFBS and LPP values; asterisks indicate the full UFBS (100%) and LPP (1.00) values.

Gene tree discordance

Despite the consistent tree topologies observed between concatenated and coalescent phylogenies, the Phyparts analysis revealed a significant level of phylogenetic discordance among informative gene trees (Fig. 3). Specifically, the sister relationship between Paris and Trillium, as well as the monophyly of Paris, lacked support from the majority of informative gene trees (Fig. 3). Within the genus Paris, most informative gene trees did not provide support for the successive sister relationships of sect. Paris, sect. Kinugasa, sect. Thibeticae, sect. Axiparis and sect. Euthyra (Fig. 3). Furthermore, substantial incongruences in informative gene trees were observed at internal nodes within sect. Axiparis and sect. Euthyra (Fig. 3), particularly those with low support values in either concatenated or coalescent phylogenies (Fig. 2).

Fig. 3.

Concordances and conflicts between nuclear gene and species trees resulting from Phyparts analysis. Gene tree concordance and conflict numbers are displayed above and below each branch. Pie charts on the nodes represent the proportion of gene trees supporting the clade (blue), the main alternative bifurcation (green), the remaining alternative bifurcations (red), and with BS values <50% (grey).

Phylogenetic network analysis and ILS simulation

The phylogenetic network analysis (Fig. 4) revealed that five putative reticulate evolution events likely represent the optimal scheme, based on the log probability values of global optimum of the likelihood (Supplementary Data Table S5). The initial hybridization event involved P. japonica (γ = 0.731) and the stem lineage ancestor of Trillium and Paris (γ = 0.269). Following this crossing event, the resulting offspring (γ = 0.487) further interbred with the stem lineage ancestor of P. bashanensis and P. verticillata (γ = 0.513), leading to the emergence of the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of sect. Thibeticae, sect. Axiparis and sect. Euthyra. The third hybridization event occurred between P. yunnanensis (γ = 0.391) and the stem lineage ancestor of P. caobangensis and P. vietnamensis (γ = 0.609), resulting in the emergence of P. liana. Subsequently, the fourth hybridization event occurred between P. liana (γ = 0.339) and the stem ancestor of the clade comprising P. chinensis, P. delavayi and P. qiliangiana (γ = 0.661). Following this hybridization event, the offspring (γ = 0.713) subsequently mated with P. vaniotii (γ = 0.287), resulting in the occurrence of the stem lineage ancestor of P. dunniana and P. xichouensis.

Fig. 4.

Five putative reticulate evolution events revealed by phylogenetic network analysis.

Based on the tree topologies of concatenated and coalescent phylogenies, the estimated θ values for Paris ranged from 0.0022 (the ancestral branch of Paris) to 0.0491 (Fig. 5). Within the genus Paris, ancestral branches of the two clades corresponding to P. polyphylla + P. lancifolia (0.0478) and P. luquanensis + P. mairei + P. yanchii (0.0491) exhibited relatively higher levels of θ values, suggesting that the divergence of these species might have undergone ILS (Fig. 5). Based on this premise, we conducted simulations of 100 000 gene trees under the conditions of relatively high likelihood ILS with a θ value set at 0.0491, as well as relatively low likelihood or absent ILS by setting the θ value to 0.0022. The simulated gene trees under low likelihood or absent ILS condition exhibited a relatively lower level of concordance with the empirical gene trees (R2 = 0.723, P < 0.05), in contrast to the simulated gene trees under the strong ILS condition (R2 = 0.733, P < 0.05). This implies that, in additional to hybridization, the topological discordance of gene trees observed at the internal nodes within sect. Euthyra could partially contribute to ITS (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

ILS simulation analysis. (A) Estimated θ (theta) value for each internal branch of Paris. Warmer colours indicate higher θ and thus higher ILS level. Terminal branches are coloured grey due to lack of data to infer θ. (B, C) Correlation analyses of topology frequency of simulated and empirical gene trees; the P values were both <0.05. (B) Correlation of simulation with θ as 0.0022 and empirical observation. (C) Correlation of simulation with θ as 0.0491 and empirical observation.

DISCUSSION

Putative hybridization and ILS events in the evolutionary history of Paris

The Phyparts analysis (Fig. 3) revealed extensive conflicts among informative nuclear gene trees, indicating the complex evolutionary history of Paris. Specifically, a majority of informative gene trees did not support the monophyly of Paris as well as the successive sister relationships among sect. Paris, sect. Kinugasa, sect. Thibeticae, sect. Axiparis and sect. Euthyra, suggesting that the early diversification of Paris might have experienced hybridization or ILS events. The reticulate evolution analysis (Fig. 4) revealed that the early evolution of Paris potentially involved two ancient hybridization events, which likely contributed to the emergence of the MRCA of sect. Thibeticae, sect. Axipraris and sect. Euthyra. Notably, these three sections presumed to have originated from hybridization exhibit distinct transitional morphological characteristics between their congeneric parental lineages (i.e. sect. Paris and sect. Kinugasa). As depicted in Fig. 6, sect. Paris is characterized by possessing leaf-like sepals, rounded fruits and long and slender rhizomes in contrast to the showy white sepals, angular fruits and thick rhizomes observed in sect. Kinugasa. The presence of morphological intermediates, characterized by leaf-like sepals, angular fruits and thick rhizomes, provides morphological evidence supporting the hybrid origin of sect. Thibeticae, sect. Axipraris and sect. Euthyra as inferred from reticulate evolution analysis. The ancestral branch of Paris exhibited the lowest estimated θ value (0.0022) compared with the internal nodes within this genus, suggesting that such discrepancies in gene tree topologies cannot be attributed to ILS. Therefore, the observed cytonuclear discordances (Ji et al., 2006, 2019, 2022; Ji, 2021) and gene tree inconsistencies (this study) regarding the deep phylogenetic relationships of Paris are likely attributable to these hybridization events, which potentially occurred during the early diversification of this genus.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of rhizome, flower, fruit and seed morphology among the five section-level taxonomic units currently recognized in the genus Paris.

Notably, both the concatenated and coalescent phylogenies exhibited limited branch support for the majority of internal nodes within sect. Axiparis and sect. Euthyra (Fig. 2), accompanied by pronounced levels of gene tree discordance as revealed by Phyparts analysis (Fig. 3). The findings suggest that that the diversification of shallow branches in Paris might have involved certain evolutionary complex events. In line with this, the ILS simulation analysis (Fig. 5) showed that the divergence of P. luquanensis, P. mairei and P. polyphylla, as well as P. lancifolia and P. yanchii, might have experienced ILS. Additionally, the reticulate evolution analysis (Fig. 4) demonstrated the potential occurrence of three hybridization events during the diversification internal nodes within sect. Axiparis and sect. Euthyra. Collectively, the findings suggest that the observed cytonuclear discordances (Ji et al., 2006, 2019, 2022; Ji, 2021) and gene tree inconsistencies (this study) regarding the phylogenetic relationships of shallow branches in Paris are likely attributable to both hybridization-induced introgression of cytoplasmic genomes as well as stochastic inheritance of polymorphic ancestral genotypes associated with ILS events. Accordingly, the frequently observed cytonuclear discordance in the phylogeny of Paris can primarily be attributed to recurrent hybridization events, with secondary contributions from ILS events.

Within the genus Paris, the pharmaceutically important species P. yunnanensis exhibits significant intraspecific phenotypic variations (Li, 1998; Ji, 2021; Zhou et al., 2023). Based on both morphological and molecular evidence, a previous investigation has demonstrated that P. yunnanensis, as conventionally defined, encompasses two morphologically similar but genetically distinct lineages with non-overlapping distribution ranges; consequently, the identification and description of P. liana as a novel species were conducted (Ji et al., 2020). Our data revealed the potential hybrid origin of P. liana, which can be attributed to an interbreeding event between P. yunnanensis and the stem lineage ancestor of P. caobangensis and P. vietnamensis (Fig. 4). This finding provides robust evidence supporting the taxonomic treatment recognizing P. liana as an independent species. Notably, P. liana, along with P. yunnanensis, P. caobangensis and P. vietnamensis, is a diploid species exhibiting a chromosome number of 2n = 10 (Ji, 2021), indicating that the origin of P. liana did not involve any alteration in chromosome number or ploidy level, thus representing a plausible case of homoploid hybrid speciation.

The reticulate evolution analysis (Fig. 4) also revealed subsequent intercrossing events between P. liana and the stem lineage ancestor of P. chinensis, P. delavayi and P. qiliangiana, followed by additional intercrossing between their hybrid progeny and P. vaniotii, resulting in the emergence of the stem lineage ancestor of P. dunniana and P. xichouensis. Therefore, the inability of the coalescent phylogeny to resolve sect. Axiparis as monophyletic can be attributed to the hybridization event between P. vaniotii (sect. Axiparis) and species belonging to sect. Euthyra. Similarly, all the species involved in the two hybridization events are diploid with identical chromosome number (2n = 10), indicating that the origin of the common ancestor of P. dunniana and P. xichouensis also did not undergo polyploidization.

Evolutionary significance of recurrent hybridization in Paris

Hybridization has gained widespread recognition as a prominent evolutionary force driving lineage diversification and speciation in plants (Soltis and Soltis, 2009; Stull et al., 2023). Consistent with this viewpoint, our reticulate evolution analysis (Fig. 4) revealed that two ancient hybridization events likely gave rise to the MRCA of sect. Thibeticae, sect. Axiparis and sect. Euthyra, ultimately leading to the emergence of three out of the five currently recognized section-level lineages within the genus Paris. Among these three section-level taxonomic units potentially derived from hybridization, sect. Euthyra exhibits the highest species richness within the genus Paris, encompassing 17 out of 26 currently recognized species. Within the sect. Euthyra, the reticulate evolution analysis also demonstrated that three species (P. dunniana, P. liana and P. xichouensis) might have originated through three hybridization events (Fig. 4). Collectively, the findings suggest that hybridization might have played a significant role in the formation of reticulate lineages and species diversity within the genus Paris.

According to the large genome constraint hypothesis, plant lineages with larger genomes are expected to exhibit a diminished rate of species diversification (Knight et al., 2005; Suda et al., 2005). Despite the larger genome sizes observed in Paris species compared with most angiosperms (Pellicer et al., 2014; Ji, 2021), a previous study has demonstrated an increased rate of speciation in Paris (especially within sect. Euthyra) around the Miocene/Pliocene boundary, challenging the theoretical prediction that large genome sizes may constrain plant speciation (Ji et al., 2019; Ji, 2021). Considering the pivotal role of recurrent hybridization events in driving lineages diversification and promoting species diversity within the genus Paris, it is plausible to hypothesize that the constraining effects imposed by large genome sizes on lineage diversification and speciation could be counterbalanced by the creative evolutionary force of hybridization. Consequently, the possession of large genomes did not significantly impede the evolutionary diversification of this genus.

The recurrent hybridization events within the genus Paris might have acted as a pivotal evolutionary driving force, not only generating morphological innovations in taxa derived from hybridization but also facilitating their ecological adaptabilities. Specifically, the three sections (i.e. sect. Thibeticae, sect. Axipraris and sect. Euthyra) that might have originated from hybridization exhibit distinct seed morphologies compared with their congeneric parental lineages. As illustrated in Fig. 6, seeds of sect. Axiparis and sect. Thibeticae are partially enveloped by a spongy or juicy aril, while seeds of sect. Euthyra are completely enclosed within a succulent sarcotesta. The seed morphologies of these reticulate lineages are more conducive to avian dispersal than those (seeds lacking a thick outer covering) of their parental lineages (Ji, 2021). Additionally, all species belonging to these lineages derived from hybridization are exclusively confined to subtropical and tropical regions of China, the Himalayas and northern Indochina (Ji, 2021). The distribution pattern of these reticulate lineages exhibits a stronger preference for low-latitude regions compared with their congeneric parental lineages (i.e. sect. Paris and sect. Kinugasa), which primarily occur in the temperate areas of East Asia and Europe (Hara, 1969; Li, 1998; Ji, 2021). Furthermore, within sect. Euthyra, the three presumed hybridization-derived species (i.e. P. dunniana, P. liana and P. xichouensis) not only exhibit distinct morphological (Supplementary Data Table S6) and phenological (Supplementary Data Table S7) variations but also demonstrate limited geographic overlap in their parental lineage distribution ranges (Supplementary Data Table S8). The findings provide robust support for the theoretical prediction that interbreeding between diverged lineages is likely to give rise to offspring exhibiting novel phenotypic traits and ecological adaptabilities through the combination of diverse gene pools, which may empower hybrid progenies to effectively exploit ecological niches unexplored by their parental lineages (Payseur and Rieseberg, 2016; Meier et al., 2017).

Phylogenetic implications

The concatenated phylogenetic analysis of 528 low-copy nuclear orthologous genes recovered five successively divergent clades within Paris with robust branch support (Fig. 2A), corresponding precisely to the five section-level taxonomic units delineated by Ji (2021). Although the coalescent phylogeny (Fig. 2B) failed to resolve sect. Axiparis as monophyletic, it exhibited similar tree topology in terms of inter-sectional relationships with the concatenated phylogeny. Notably, the inter-sectional relationships recovered in this study exhibit perfect consistency with those inferred from plastome phylogeny (Fig. 1A), while diverging from those obtained through phylogenetic analysis of nuclear nrDNA arrays (Fig. 1B). As revealed by the reticulate evolution analysis (Fig. 4), the early evolution of Paris might have experienced two ancient hybridization events, which potentially led to the gene conversion of nrDNA arrays inherited from the stem lineage ancestor of Trillium and Paris in the MRCA of sect. Thibeticae, sect. Axipraris and sect. Euthyra. This could explain the discrepancies observed between plastome and nrDNA phylogenies regarding the deep relationships of Paris. Although the plastome phylogeny robustly supports the monophyly of Paris, the nrDNA phylogeny reveals that the clade comprising sect. Thibeticae, sect. Axipraris and sect. Euthyra is sister to the clade consisting of Trillium, sect. Paris and sect. Kinugasa (Fig. 1).

The genus Paris exhibits a significant degree of variability in leaf, flower, fruit and seed morphologies, which have been extensively utilized for taxonomic investigations (Li, 1998; Ji, 2021). Inferring from the prominent morphological heterogeneity of the genus, Takhtajan (1982) divided it into three separate genera, namely Daiswa (= sect. Axiparis + sect. Euthyra + sect. Thibeticae), Kinugasa (= the monotypic sect. Kinugasa) and Paris s.s. (= sect. Paris). The occurrence of the MRCA of sect. Thibeticae, sect. Axipraris and sect. Euthyra appears to have resulted from two ancient hybridization events potentially involving the MRCA of Paris and Trillium, sect. Kinugasa and the stem lineage ancestor of sect. Paris, as indicated by our reticulate analysis (Fig. 4). The findings suggest the taxonomic treatment proposed by Takhtajan (1982) to recognize Daiswa as a separate genus hold some degree of validity. Nevertheless, both concatenated and coalescent phylogenetic analyses of a set of 528 low-copy nuclear orthologous genes derived from transcriptome sequencing data consistently demonstrated the monophyletic nature of Paris and revealed its sister relationship with Trillium (Fig. 2), aligning with previous phylogenetic investigations (Ji et al., 2006, 2019; Huang et al., 2016). The findings provide additional empirical evidence supporting the taxonomic circumscription of Paris as a distinctive genus (Hara, 1969; Li, 1998; Ji, 2021).

Our phylotranscriptomic analyses reconstructed robust inter-sectional relationships within Paris. However, the interspecific relationships within sect. Axiparis and sect. Euthyra remain unsolved due to low support for the majority of their internal nodes in both concatenated and coalescent phylogenies. The reticulate analysis and ILS simulation suggest that the evolution of the two sections might have experienced recurrent hybridization and ILS events. Given the inferred evolutionary complexity, it is imperative to utilize genomic data and employ synteny-based phylogenomic reconstruction in order to elucidate the inter-specific relationships of sect. Axiparis and sect. Euthyra in future studies.

Implications for the breeding of medicinal Paris

Over the past decades, the pharmaceutical industry has exclusively relied on naturally sourced rhizomes of medicinal Paris species as a raw material, and the natural propagation and population growth rate of Paris species is generally characterized by a notably sluggish pace (Li, 1998; He et al., 2006; Li et al., 2015). The pharmaceutical industry’s substantial demand for and consumption of raw materials (~3 000 000 kg per year) have inevitably led to the overexploitation of natural populations of medicinal Paris species due to extensive wild collection of their rhizomes (Huang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015; Cunningham et al., 2018; Ji, 2021). To tackle the scarcity of raw materials in the pharmaceutical industry, the commercial cultivation of medicinal Paris species has been implemented in China and the Himalayas since the early 21st century (Li et al., 2015; Cunningham et al., 2018; Ji, 2021). The present cultivation process for medicinal Paris species typically spans a minimum duration of 7 years, encompassing various stages ranging from sowing to rhizome harvesting (He et al., 2006; Li et al., 2015; Ji, 2021). The prolonged growth period and low rhizome yield are widely recognized as a significant bottleneck that hinders the commercial cultivation of medicinal Paris species (Li et al., 2015; Ji, 2021). Therefore, it is imperative to abbreviate the cultivation cycle of medicinal Paris by selectively breeding superior cultivars exhibiting a higher population growth rate and increased rhizome biomass.

Notably, among Paris species with a thick rhizome, P. dunniana, P. liana and P. xichouensis exhibit significantly greater plant heights and higher rhizome biomasses (Ji, 2021). Our data suggest that the origins of these three species are likely an outcome of hybridization, indicating that hybridization between Paris species can confer parental advantages or induce heterosis. Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of achieving interspecific outcrossing through artificial pollination between most Paris species with thick rhizomes and similar flowering phenology (Li, 1998; Li et al., 2015). The findings imply that artificially mediated interspecific hybridization can be an effective strategy for breeding medicinal Paris cultivars with increased rhizome yield and improved medicinal quality, thus promoting progress in the commercial cultivation of medicinal Paris.

Conclusions

Based on a comprehensive transcriptomic dataset, this study reconstructed robust inter-sectional relationships for the monocotyledonous genus Paris, thereby providing additional empirical evidence to resolve the long-standing disputes regarding the taxonomic circumscription and subgeneric classification of the genus. Based on the observed discordance among gene trees, analysis of reticulate evolution and ILS simulations, our findings suggest that hybridization events may have recurrently occurred throughout the evolutionary history of Paris, while only certain shallow nodes experienced ILS events. Therefore, the observed phylogenetic incongruences between plastid and nuclear sequence data in previous studies on Paris (Ji et al., 2006, 2019, 2022) can primarily be attributed to extensive cytoplasmic introgression resulting from these hybridization events, and secondarily to stochastic inheritance of polymorphic ancestral genotypes associated with ILS events. Our findings also indicate that hybridization might have played a pivotal role in driving lineage diversification and speciation within the genus Paris and concurrently led to morphological innovation and enhanced ecological adaptability. Considering the advantageous impacts of hybridization on the evolutionary trajectory of this genus, it is plausible to employ artificially mediated inter- or intraspecific intercrossing for breeding cultivars of medicinal Paris with improved rhizome yield and enhanced medicinal quality. The present study will significantly contribute to our comprehensive understanding of the evolutionary complexity of this pharmaceutically significant plant lineage, thereby facilitating the effective exploration and conservation of medicinal Paris species.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Annals of Botany online and consist of the following. Table S1: information on the plant samples collected for RNA sequencing in this study. Table S2: information on transcriptome data obtained from publicly available databases. Table S3: summary of the transcriptome assembly. Table S4: sequence characteristics of 528 orthologous genes obtained from transcriptome data. Table S5: optimal scheme for reticulation evolutionary analysis. Table S6: morphological characteristics of the three presumed hybridization-derived species and their parental lineages. Table S7: habitats and phenology of the three presumed hybridization-derived species and their parental lineages. Table S8: geographic distribution of the three presumed hybridization-derived species and their parental lineages.

ACKNOWLDEGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Chengjin Yang, Guohua Zhou, Qiliang Gan, Zhangming Wang, Qiuping Tan and Yulong Li, for their help in sample collection.

Contributor Information

Nian Zhou, State Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Natural Medicines, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China; Kunming College of Life Science, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China; CAS Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China.

Ke Miao, State Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Natural Medicines, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China; Kunming College of Life Science, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China; CAS Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China.

Luxiao Hou, State Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Natural Medicines, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China; Kunming College of Life Science, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China; CAS Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China.

Haiyang Liu, State Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Natural Medicines, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China.

Jiahui Chen, CAS Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China.

Yunheng Ji, State Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Natural Medicines, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China; CAS Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650201, China.

FUNDING

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31872673, 32370395) and the Yunnan Revitalization Talent Support Program ‘Top Team’ Project (202305AT350001).

DATA AVAILABILITY

The RNA-seq data generated in this study are available in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) database (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA018292) under the accession number CRA012960.

LITERATURE CITED

- Acosta MC, Premoli AC.. 2010. Evidence of chloroplast capture in South American Nothofagus (subgenus Nothofagus, Nothofagaceae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 54: 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. 1998. An ordinal classification for the families of flowering plants. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 85: 531–553. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B.. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30: 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JW, Walker JF, Smith SA.. 2017. Phyx: phylogenetic tools for unix. Bioinformatics 33: 1886–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunsfeld SJ, Soltis DE, Soltis PS.. 1992. Evolutionary patterns and processes in Salix sect. Longifoliae: evidence from chloroplast DNA. Systematic Botany 17: 239–256. [Google Scholar]

- Bruun-Lund S, Clement WL, Kjellberg F, Ronsted N.. 2017. First plastid phylogenomic study reveals potential cyto-nuclear discordance in the evolutionary history of Ficus L. (Moraceae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 109: 93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai LM, Xi ZX, Lemmon EM, et al. 2021. The perfect storm: gene tree estimation error, incomplete lineage sorting, and ancient gene flow explain the most recalcitrant ancient angiosperm clade, Malpighiales. Systematic Biology 70: 491–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, et al. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10: 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Ye K, Zhang B, et al. 2019. Paris saponin II inhibits colorectal carcinogenesis by regulating mitochondrial fission and NF-kappaB pathway. Pharmacological Research 139: 273–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong Y, Liu X, Kang L, et al. 2012. Pennogenin tetraglycoside stimulates secretion-dependent activation of rat platelets: evidence for critical roles of adenosine diphosphate receptor signal pathways. Thrombosis Research 129: e209–e216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AB, Brinckmann JA, Bi YF, Pei SJ, Schippmann U, Luo P.. 2018. Paris in the spring: a review of the trade, conservation and opportunities in the shift from wild harvest to cultivation of Paris polyphylla (Trilliaceae). Journal of Ethnopharmacology 222: 208–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng D, Lauren DR, Cooney JM, et al. 2008. Antifungal saponins from Paris polyphylla Smith. Planta Medica 74: 1397–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding YG, Zhao YL, Zhang J, Zuo ZT, Zhang QZ, Wang YZ.. 2021. The traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological properties of Paris L. (Liliaceae): a review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 278: 114293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding YM, Pang XX, Cao Y, et al. 2023. Genome structure-based Juglandaceae phylogenies contradict alignment-based phylogenies and substitution rates vary with DNA repair genes. Nature Communications 14: 617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodsworth S, Leitch AR, Leitch IJ.. 2015. Genome size diversity in angiosperms and its influence on gene space. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 35: 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dongen SV. 2008. Graph clustering via a discrete uncoupling process. SIAM Journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications 30: 121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Duan L, Fu L, Chen HF.. 2023. Phylogenomic cytonuclear discordance and evolutionary histories of plants and animals. Science China Life Sciences 66: 2946–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folk RA, Mandel JR, Freudenstein JV.. 2017. Ancestral gene flow and parallel organellar genome capture result in extreme phylogenomic discord in a lineage of angiosperms. Systematic Biology 66: 320–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folk RA, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Guralnick R.. 2018. New prospects in the detection and comparative analysis of hybridization in the tree of life. American Journal of Botany 105: 364–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia N, Folk RA, Meerow AW, et al. 2017. Deep reticulation and incomplete lineage sorting obscure the diploid phylogeny of rain-lilies and allies (Amaryllidaceae tribe Hippeastreae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 111: 231–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EM, Bruun-Lund S, Niissalo M, et al. 2023. Echoes of ancient introgression punctuate stable genomic lineages in the evolution of figs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 120: e2222035120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, et al. 2011. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology 29: 644–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, Luo Y, Gao LM, et al. 2023. Phylogenomics and the flowering plant tree of life. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 65: 299–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, et al. 2013. Transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature Protocols 8: 1494–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara H. 1969. Variation in Paris polyphylla Smith, with reference to other Asiatic species. Journal of the Faculty of Science, University of Tokyo, Section III 10: 141–180. [Google Scholar]

- He J, Zhang S, Wang H, Chen C, Chen S.. 2006. Advances in studies on and uses of Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Trilliaceae). Acta Botanica Yunnanica 28: 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis DM, Moritz C, Porter CA, Baker RJ.. 1991. Evidence for biased gene conversion in concerted evolution of ribosomal DNA. Science 251: 308–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu HY, Sun PC, Yang YZ, Ma JX, Liu JQ.. 2023. Genome-scale angiosperm phylogenies based on nuclear, plastome, and mitochondrial datasets. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 65: 1479–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LQ, Xiao PG, Wang YY.. 2012. Investigation on resources of rare and endangered medicinal plants in China. Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Li X, Yang Z, Yang C, Yang J, Ji Y.. 2016. Analysis of complete chloroplast genome sequences improves phylogenetic resolution of Paris (Melanthiaceae). Frontiers in Plant Science 7: 1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson DH, Scornavacca C.. 2012. Dendroscope 3: an interactive tool for rooted phylogenetic trees and networks. Systematic Biology 61: 1061–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y. 2021. A monograph of Paris (Melanthiaceae). Beijing and Singapore: Science Press and Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y, Fritsch PW, Li H, Xiao T, Zhou Z.. 2006. Phylogeny and classification of Paris (Melanthiaceae) inferred from DNA sequence data. Annals of Botany 98: 245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y, Yang L, Chase MW, et al. 2019. Plastome phylogenomics, biogeography, and clade diversification of Paris (Melanthiaceae). BMC Plant Biology 19: 543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y, Liu C, Yang J, Jin L, Yang Z, Yang JB.. 2020. Ultra-barcoding discovers a cryptic species in Paris yunnanensis (Melanthiaceae), a medicinally important plant. Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y, Yang J, Landis JB, et al. 2022. Genome skimming contributes to clarifying species limits in Paris section Axiparis (Melanthiaceae). Frontiers in Plant Science 13: 832034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y, Landis JB, Yang J, et al. 2023. Phylogeny and evolution of Asparagaceae subfamily Nolinoideae: new insights from plastid phylogenomics. Annals of Botany 131: 301–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Wang S, Hu J, Miao K, Huang Y, Ji Y.. 2024. Plastid phylogenomics and fossil evidence provide new insights into the evolutionary complexity of the ‘woody clade’ in Saxifragales. BMC Plant Biology 24: 277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly S. 2012. JML: testing hybridization from species trees. Molecular Ecology Resources 12: 179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly S, McLenachan PA, Lockhart PJ.. 2009. A statistical approach for distinguishing hybridization and incomplete lineage sorting. American Naturalist 174: E54–E70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junier T, Zdobnov EM.. 2010. The Newick utilities: high-throughput phylogenetic tree processing in the UNIX shell. Bioinformatics 26: 1669–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM.. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight CA, Molinari NA, Petrov DA.. 2005. The large genome constraint hypothesis: evolution, ecology and phenotype. Annals of Botany 95: 177–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen EJM, Ojeda DI, Steeves R, et al. 2020. Large-scale genomic sequence data resolve the deepest divergences in the legume phylogeny and support a near-simultaneous evolutionary origin of all six subfamilies. New Phytologist 225: 1355–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovarik A, Pires JC, Leitch AR, et al. 2005. Rapid concerted evolution of nuclear ribosomal DNA in two Tragopogon allopolyploids of recent and recurrent origin. Genetics 169: 931–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfear R, Frandsen PB, Wright AM, Senfeld T, Calcott B.. 2017. PartitionFinder 2: new methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Molecular Biology and Evolution 34: 772–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL.. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods 9: 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch IJ, Beaulieu JM, Chase MW, Leitch AR, Fay MF.. 2010. Genome size dynamics and evolution in monocots. Journal of Botany 2010: 862516. [Google Scholar]

- Li H. 1998. The genus Paris (Trilliaceae). Beijing: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Godzik A.. 2006. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22: 1658–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HI, Bao SU, Zhao YZ, Yu MY.. 2015. An assessment on the rarely medical Paris plants in China with exploring the future development of its plantation. Journal of West China Forestry Science 44: 1–7 + 15. [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhang Y, Ruhsam M, et al. 2022. Seeing through the hedge: phylogenomics of Thuja (Cupressaceae) reveals prominent incomplete lineage sorting and ancient introgression for Tertiary relict flora. Cladistics 38: 187–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang SY, Soukup VG.. 2000. Paris L. In: Wu ZY, Raven PH. ed. Flora of China. Beijing and St Louis: Science Press and Missouri Botanical Garden Press, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lim KY, Kovarik A, Matyasek R, Bezdek M, Lichtenstein CP, Leitch AR.. 2000. Gene conversion of ribosomal DNA in is associated with undermethylated, decondensed and probably active gene units. Chromosoma 109: 161–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnaeus C. 1753. Species plantarum. Stockholm: Salvius. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Yu LL.. 2010. Phybase: an R package for species tree analysis. Bioinformatics 26: 962–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP. 1997. Gene trees in species trees. Systematic Biology 46: 523–536. [Google Scholar]

- Mai U, Mirarab S.. 2018. TreeShrink: fast and accurate detection of outlier long branches in collections of phylogenetic trees. BMC Genomics 19: 272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon GE, Steane DA, Potts BM, Vaillancourt RE.. 1999. Incongruence between chloroplast and species phylogenies in Eucalyptus subgenus Monocalyptus (Myrtaceae). American Journal of Botany 86: 1038–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier JI, Marques DA, Mwaiko S, Wagner CE, Excoffier L, Seehausen O.. 2017. Ancient hybridization fuels rapid cichlid fish adaptive radiations. Nature Communications 8: 14363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao K, Wang T, Tang L, Hou L, Ji Y.. 2024. Establishing the first reference library for utilizing high-throughput sequencing technologies in identifying medicinal and endangered Paris species (Melanthiaceae). Industrial Crops and Products 218: 118871. [Google Scholar]

- Minh BQ, Nguyen MAT, von Haeseler A.. 2013. Ultrafast approximation for phylogenetic bootstrap. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 1188–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, et al. 2020. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Molecular Biology and Evolution 37: 1530–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirarab S, Bayzid MS, Warnow T.. 2016. Evaluating summary methods for multilocus species tree estimation in the presence of incomplete lineage sorting. Systematic Biology 65: 366–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Briones DF, Liston A, Tank DC.. 2018. Phylogenomic analyses reveal a deep history of hybridization and polyploidy in the Neotropical genus Lachemilla (Rosaceae). New Phytologist 218: 1668–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payseur BA, Rieseberg LH.. 2016. A genomic perspective on hybridization and speciation. Molecular Ecology 25: 2337–2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicer J, Fay MF, Leitch IJ.. 2010. The largest eukaryotic genome of them all? Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 164: 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pellicer J, Kelly LJ, Leitch IJ, Zomlefer WB, Fay MF.. 2014. A universe of dwarfs and giants: genome size and chromosome evolution in the monocot family Melanthiaceae. New Phytologist 201: 1484–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin XJ, Sun DJ, Ni W, et al. 2012. Steroidal saponins with antimicrobial activity from stems and leaves of Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Steroids 77: 1242–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin XJ, Yu MY, Ni W, et al. 2016. Steroidal saponins from stems and leaves of Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Phytochemistry 121: 20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin XJ, Ni W, Chen CX, Liu HY.. 2018. Seeing the light: shifting from wild rhizomes to extraction of active ingredients from above-ground parts of Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 224: 134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu YL, Lee J, Bernasconi-Quadroni F, et al. 1999. The earliest angiosperms: evidence from mitochondrial, plastid and nuclear genomes. Nature 402: 404–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Soltis DE.. 1991. Phylogenetic consequences of cytoplasmic gene flow in plants. American Journal of Botany 5: 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Beckstrom-Sternberg S, Doan K.. 1990. Helianthus annuus ssp. texanus has chloroplast DNA and nuclear ribosomal RNA genes of Helianthus debilis ssp. cucumerifolius. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 87: 593–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokas A, Williams BL, King N, Carroll SB.. 2003. Genome-scale approaches to resolving incongruence in molecular phylogenies. Nature 425: 798–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salichos L, Rokas A.. 2013. Inferring ancient divergences requires genes with strong phylogenetic signals. Nature 497: 327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambatti JB, Strasburg JL, Ortiz-Barrientos D, Baack EJ, Rieseberg LH.. 2012. Reconciling extremely strong barriers with high levels of gene exchange in annual sunflowers. Evolution 66: 1459–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RL, Sytsma KJ.. 1990. Evolution of Populus nigra (Sect. Aigeiros): introgressive hybridization and the chloroplast contribution of Populus alba (Sect. Populus). American Journal of Botany 77: 1176–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SA, Moore MJ, Brown JW, Yang Y.. 2015. Analysis of phylogenomic datasets reveals conflict, concordance, and gene duplications with examples from animals and plants. BMC Evolutionary Biology 15: 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Unna R, Boursnell C, Patro R, Hibberd JM, Kelly S.. 2016. TransRate: reference-free quality assessment of de novo transcriptome assemblies. Genome Research 26: 1134–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis DE, Kuzoff RK.. 1995. Discordance between nuclear and chloroplast phylogenies in the Heuchera group (Saxifragaceae). Evolution 49: 727–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis PS, Soltis DE.. 2009. The role of hybridization in plant speciation. Annual Review of Plant Biology 60: 561–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis DE, Johnson LA, Looney C.. 1996. Discordance between ITS and chloroplast topologies in the Boykinia group (Saxifragaceae). Systematic Botany 21: 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30: 1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull GW, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Gitzendanner MA, Smith SA.. 2020. Nuclear phylogenomic analyses of asterids conflict with plastome trees and support novel relationships among major lineages. American Journal of Botany 107: 790–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull GW, Pham KK, Soltis PS, Soltis DE.. 2023. Deep reticulation: the long legacy of hybridization in vascular plant evolution. Plant Journal 114: 743–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda J, Kyncl T, Jarolímová V.. 2005. Genome size variation in Macaronesian angiosperms: forty percent of the Canarian endemic flora completed. Plant Systematics and Evolution 252: 215–238. [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Liu BR, Hu WJ, Yu LX, Qian XP.. 2007. In vitro anticancer activity of aqueous extracts and ethanol extracts of fifteen traditional Chinese medicines on human digestive tumor cell lines. Phytotherapy Research 21: 1102–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Zhu X, Burleigh JG, Chen Z.. 2015. Deep phylogenetic incongruence in the angiosperm clade Rosidae. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 83: 156–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takhtajan A. 1982. A revision of Daiswa (Trilliaceae). Brittonia 35: 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Than C, Ruths D, Nakhleh L.. 2008. PhyloNet: a software package for analyzing and reconstructing reticulate evolutionary relationships. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsitrone A, Kirkpatrick M, Levin DA.. 2003. A model for chloroplast capture. Evolution 57: 1776–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Xie DF, Price M, et al. 2021. Backbone phylogeny and evolution of Apioideae (Apiaceae): new insights from phylogenomic analyses of plastome data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 161: 107183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF, Doyle JJ.. 1998. Phylogenetic incongruence: window into genome history and molecular evolution. In: Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Doyle JJ. eds. Molecular systematics of plants II . Boston: Springer, 265–296. [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF, Schnabel A, Seelanan T.. 1995. An unusual ribosomal DNA-sequence from Gossypium gossypioides reveals ancient, cryptic, intergenomic introgression. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 4: 298–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe AD, Elisens WJ.. 1995. Evidence of chloroplast capture and pollen-mediated gene flow in Penstemon sect. Peltanthera (Scrophulariaceae). Systematic Botany 20: 395–412. [Google Scholar]

- Xie ZZ, Li MM, Deng PF, et al. 2017. Paris saponin-induced autophagy promotes breast cancer cell apoptosis via the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Chemico-Biological Interactions 264: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Smith SA. 2014. Orthology inference in nonmodel organisms using transcriptomes and low-coverage genomes: improving accuracy and matrix occupancy for phylogenomics. Molecular Biology and Evolution 31: 3081–3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Yang Z, Liu C, et al. 2019a. Chloroplast phylogenomic analysis provides insights into the evolution of the largest eukaryotic genome holder, Paris japonica (Melanthiaceae). BMC Plant Biology 19: 293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Yang L, Liu C, et al. 2019b. Transcriptome analyses of Paris polyphylla var. chinensis, Ypsilandra thibetica, and Polygonatum kingianum characterize their steroidal saponin biosynthesis pathway. Fitoterapia 135: 52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Nakhleh L.. 2015. A maximum pseudo-likelihood approach for phylogenetic networks. BMC Genomics 16: S10. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2164-16-S10-S10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Niu Y, You Y, et al. 2023. Integrated phylogenomic analyses unveil reticulate evolution in Parthenocissus (Vitaceae), highlighting speciation dynamics in the Himalayan-Hengduan Mountains. New Phytologist 238: 888–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Rabiee M, Sayyari E, Mirarab S.. 2018a. ASTRAL-III: polynomial time species tree reconstruction from partially resolved gene trees. BMC Bioinformatics 19: 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Li K, Sun C, et al. 2018b. Anti-cancer effects of Paris polyphylla ethanol extract by inducing cancer cell apoptosis and cycle arrest in prostate cancer cells. Current Urology 11: 144–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Gao F, Jakovlic I, et al. 2020. PhyloSuite: an integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Molecular Ecology Resources 20: 348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N, Tang L, Xie P, et al. 2023. Genome skimming as an efficient tool for authenticating commercial products of the pharmaceutically important Paris yunnanensis (Melanthiaceae). BMC Plant Biology 23: 344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N, Miao K, Liu C, et al. 2024. Historical biogeography, and evolutionary diversification of Lilium (Liliaceae): new insights from plastome phylogenomics. Plant Diversity 46: 219–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq data generated in this study are available in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) database (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA018292) under the accession number CRA012960.