Abstract

Background and Aims

Heterotrophic plants have long been a challenge for systematists, exemplified by the base of the orchid subfamily Epidendroideae, which contains numerous mycoheterotrophic species.

Methods

Here we address the utility of organellar genomes in resolving relationships at the epidendroid base, specifically employing models of heterotachy, or lineage-specific rate variation over time. We further conduct comparative analyses of plastid genome evolution in heterotrophs and structural variation in matK.

Key Results

We present the first complete plastid genomes (plastomes) of Wullschlaegelia, the sole genus of the tribe Wullschlaegelieae, revealing a highly reduced genome of 37 kb, which retains a fraction of the genes present in related autotrophs. Plastid phylogenomic analyses recovered a strongly supported clade composed exclusively of mycoheterotrophic species with long branches. We further analysed mitochondrial gene sets, which recovered similar relationships to those in other studies using nuclear data, but the placement of Wullschlaegelia remains uncertain. We conducted comparative plastome analyses among Wullschlaegelia and other heterotrophic orchids, revealing a suite of correlated substitutional and structural changes relative to autotrophic species. Lastly, we investigated evolutionary and structural variation in matK, which is retained in Wullschlaegelia and a few other ‘late stage’ heterotrophs and found evidence for structural conservation despite rapid substitution rates in both Wullschlaegelia and the leafless Gastrodia.

Conclusions

Our analyses reveal the limits of what the plastid genome can tell us on orchid relationships in this part of the tree, even when applying parameter-rich heterotachy models. Our study underscores the need for increased taxon sampling across all three genomes at the epidendroid base, and illustrates the need for further research on addressing heterotachy in phylogenomic analyses.

Keywords: Orchidaceae, Epidendroideae, herbarium, mycoheterotrophy, comparative genomics, plastid, mitochondrial, heterotachy, Wullschlaegelia calcarata, Triphora trianthophoros, Triphora aff. wagneri, Uleiorchis ulei

INTRODUCTION

Heterotrophic plants remain among the most challenging to place in systematic studies (e.g. Nickrent et al., 1998; Barkman et al., 2007; Merckx et al., 2009; Merckx and Freudenstein, 2010; McNeal et al., 2013; Lam et al., 2018). Yet they provide apt subjects for investigating the patterns, processes and limits of genome evolutionary dynamics (dePamphilis and Palmer, 1990; Wolfe et al., 1992; Barbrook et al., 2006; Westwood et al., 2010; Merckx, 2013a; Barrett et al., 2014; Logacheva et al., 2016; Wicke et al., 2016; Graham et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2018; Lyko and Wicke, 2021; Cai, 2023). These plants have experienced major shifts in nutritional strategies, either parasitizing other plants (parasitic plants) or fungi (mycoheterotrophs). They have experienced drastic changes to their morphology, ecology, physiology, genomes and, in some cases, reproductive features (Wolfe et al., 1992; Leake and Cameron, 2010; Bromham et al., 2013; Tsukaya, 2018; Wicke and Naumann, 2018; Cai, 2023).

There are several reasons why heterotrophs remain problematic from a systematics perspective. First, morphological reduction in these leafless species equates to a lack of informative characters for identification, species delimitation, phylogenetics, and identification of synapomorphies for their taxonomic placement. Second, many have experienced plastid and nuclear genomic losses due to relaxed selection on photosynthetic function. This means many loci that would otherwise carry phylogenetic signal are missing or modified, leaving a high proportion of missing data relative to autotrophic relatives. Third, heterotrophs have accelerated substitution rates to varying degrees, among all three genomes in some cases (plastid, mitochondrial and nuclear), exacerbating issues caused by heterotachy, or lineage-specific rate heterogeneity over time. Fourth, lateral gene transfer from host to parasite is a common phenomenon, specifically in the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes of parasitic plants, potentially confounding phylogenomic signal among parasites and their often distantly related hosts. Lastly, many heterotrophic plant species are rare or endangered, growing in remote habitats – this is especially true of mycoheterotrophs – which hinders research efforts due to the difficulty of obtaining material (e.g. dePamphilis et al., 1997; Nickrent and Musselman, 2004; Bidartondo, 2005; Merckx et al., 2009; Lemaire et al., 2011; Bromham et al., 2013; Merckx, 2013b; Yang et al., 2016; Barrett et al., 2018, 2020; Lam et al., 2018; Gomes et al., 2019; Timilsena et al., 2023).

One area of the plant tree of life that has been recalcitrant from a systematics perspective is the base of the epidendroid orchids (Orchidaceae, subfamily Epidendroideae), which contains several heterotrophic lineages. The orchids are a megadiverse clade of flowering plants, comprising ~10 % of all extant plant species, and nearly half of all leafless, mycoheterotrophic species (Dressler, 1993; Pridgeon et al., 2001–2014; Merckx and Freudenstein, 2010; Merckx, 2013a; World Flora Online, http://www.worldfloraonline.org, accessed 14 February, 2024). Over 80 % of orchid species belong to Epidendroideae (van den Berg et al., 2005; Chase et al., 2015; Freudenstein and Chase, 2015). While recent progress has been made in resolving the positions of some of the major lineages (i.e. tribes) at the epidendroid base, the placements of several taxa remain in question. Some of these early-diverging lineages, sometimes referred to as the ‘basal’ or ‘primitive’ Epidendroideae, comprise groups either completely (e.g. Gastrodieae, Wullschlaegelieae) or partially (e.g. Nervilieae, Triphoreae, Neottieae) composed of leafless, mycoheterotrophic species as currently circumscribed ( Merckx et al., 2013c; Chase et al., 2015). These orchids have been the subjects of taxonomic instability over the last century and a half, especially with respect to lineages containing heterotrophs. They were often lumped into repository taxa such as the ‘neottioids’, as they share features with both what we now recognize as subfamily Orchidoideae (e.g. terrestrial habits and mealy pollen) and the currently recognized subfamily Epidendroideae (e.g. incumbent anthers; Schlechter, 1926; Dressler and Dodson, 1960; Burns-Balogh and Funk, 1986). Phylogenetic analyses of morphological and molecular data over the last three decades have vastly improved our understanding of the taxonomic affinities of many of these taxa, yet lineages containing leafless species remain problematic (e.g. Burns-Balogh and Funk, 1986; Chase et al. 1994 ; Cameron et al., 1999; Freudenstein and Rasmussen, 1996; Freudenstein et al., 2004; Górniak et al., 2010; Freudenstein and Chase, 2015; Givnish et al., 2015; Li et al., 2019; Pérez-Escobar et al., 2021, 2024; Serna-Sánchez et al., 2021; Wong and Peakall, 2022; Zhang et al., 2023).

The concentration of fully mycoheterotrophic lineages at the epidendroid base provides ample opportunities to study genome evolutionary dynamics, particularly the patterns and processes of reductive evolution, in a phylo-comparative context. This is particularly true for the plastid genome (plastome), which, due to its high copy number and relative ease of sequencing and assembly, has seen an explosive increase in the amount of data produced in the last decade (e.g. Delannoy et al., 2011; Logacheva et al., 2011; Barrett and Davis, 2012; Barrett et al., 2014, 2020; Feng et al., 2016; Graham et al., 2017; Wen et al., 2022). This has led to the formulation of several related conceptual models of the process of reductive plastome evolution in heterotrophs, which focus on pseudogenization, physical gene loss, and structural modifications over time (Wicke et al., 2011, 2016; Barrett and Davis, 2012; Barrett et al., 2014; Graham et al., 2017). These models propose first the loss of genes involved in photosynthesis or the transcription of photosynthesis-related genes, for example those encoding NADPH dehydrogenase (ndh), photosystems I and II (psa and psb), plastid-encoded RNA polymerase (rpo), RuBisCO (rbcL), ATP synthase (atp) and cytochrome b6/f complex (pet). These losses are followed by (or in some cases concurrent with) ‘housekeeping’ genes with more basic organellar functions such as transcription, translation and intron processing [e.g. ribosomal proteins (rpl, rps), transfer RNAs (trn) and maturase K (matK)]. Graham et al. (2017) proposed a set of five genes that are hypothesized to be among the last to become pseudogenized or lost even among the most highly reduced plastomes, termed ‘core non-bioenergetic’ genes (accD, clpP, trnE, ycf1 and ycf2), thought to be among the most fundamental for plastid function.

The fate of matK is particularly puzzling among the so-called housekeeping genes, in that it has seemingly been lost in an idiosyncratic fashion among species with highly reduced plastomes (e.g. Freudenstein and Senyo, 2008; McNeal et al., 2009; Graham et al., 2017; Wen et al., 2022). Interestingly, some heterotrophs bear plastomes that have lost matK and retained or lost some Group IIA introns (e.g. Braukman et al., 2017; Wen et al., 2022; Barrett et al., 2024), calling into question the structure, function and evolutionary trajectory of matK in those taxa that retain it.

Great progress has been made in comparative organellar phylogenomics of mycoheterotrophic epidendroid orchids in the last decade, yet the major impediment moving forward is taxon sampling. While genera such as the leafless Corallorhiza, Bletia (Hexalectris), Epipogium, Gastrodia, and leafless members of Neottia have been the subjects of relatively intensive study (Barrett et al., 2014, 2018, 2020; Schelkunov et al., 2015; Feng et al., 2016; Wen et al., 2022; Shao et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2024), other lineages have had just a single representative complete plastome sequenced or no plastome sequenced at all (Supplementary Data Fig. S1). These include Aphyllorchis (Neottieae), Auxopus (Gastrodieae), Cephalanthera (Neottieae), Didymoplexiella (Gastrodieae), Didymoplexis (Gastrodieae), Stereosandra (Epipogiinae), Tropidia (Tropideae), Uleiorchis (Gastrodieae) and Wullschlaegelia (Wullschlaegelieae). Focusing on these lineages will both improve phylogenetic and taxonomic resolution at the base of Epidendroideae and provide a comparative framework for quantifying the degree and timing of drastic plastome modification.

Here we focus on the leafless Wullschlaegelia calcarata, investigating its phylogenetic placement based on organellar DNA as well as its trajectory of plastome evolution among the early-diverging epidendroid orchids (Supplementary Data Fig. S2). Wullschlaegelia consists of two species, broadly but sparsely distributed through Central America, the Caribbean and South America from Peru to Paraguay (Born et al., 1999). The two species differ primarily in trichome structure and flower resupination, and are the sole members of tribe Wullschlaegelieae, the phylogenetic affinity of which is poorly understood (Dressler, 1980; Born et al., 1999; Chase et al., 2015). We further sequenced the leafless Uleiorchis ulei (Gastrodieae) and two species of the leafy/reduced-leaved Triphora (Triphoreae), as only one partially complete plastid gene set exists for the latter early-diverging epidendroid genus (Serna-Sánchez et al., 2021). Triphora (Triphoreae) is a genus of ~25 New World species with reduced, bract-like leaves whose phylogenetic placement is uncertain (Chase et al., 2015; Freudenstein and Chase, 2015; https://wfoplantlist.org, last accessed 22 February, 2024). Uleiorchis is a genus native to Central and South America comprising four leafless, fully mycoheterotrophic species placed in Gastrodieae, representing the only members of this tribe native to the New World (Born et al., 1999; Chase et al., 2015; https://wfoplantlist.org, last accessed 22 February, 2024). Our specific aims were to (1) characterize the plastome structure of W. calcarata and compare plastome evolutionary dynamics among leafless, heterotrophic members of early-diverging Epidendroideae; (2) infer phylogenetic relationships based on organellar gene sets using heterotachy-specific models; and (3) investigate the retention of the matK gene in leafy and leafless epidendroids in terms of selective constraints and predicted protein structures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Material and DNA extraction

Sequence data were generated for nine orchid accessions: two accessions were field-collected (Triphora trianthophoros and T. aff. wagneri) and seven were from herbarium material (Wullschlaegelia calcarata, Uleiorchis ulei; Table 1). Approximately 0.1 g of fresh material was used for DNA extraction, and an ~1-cm2 section of tissue was sampled from herbarium specimens from the accompanying packets, so as not to damage the mounted specimens. Total DNAs were extracted with the CTAB method (Doyle and Doyle, 1987), modified to 1/10 volume, with an additional chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1 v:v) extraction for herbarium accessions. DNA quality was checked with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and double-stranded DNAs were quantified with the Qubit Broad Range Assay via fluorometry (Thermo Fisher). The degree of DNA fragmentation was visualized on a 1 % agarose gel.

Table 1.

Accessions included in the current study. Herbarium codes: NY, New York Botanical Garden; OS, Ohio State University Herbarium; IBUG, Herbário Instituto de Botánica Universidad de Guadalajara.

| Accession | Code | Collector | Number | Year/source | Locality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wullschlaegelia calcarata | |||||

| NY 2065198 | NY-1 | Vincent | 15 387 | 2011/herbarium | Rio Grande, Puerto Rico, USA |

| NY 2330843 | NY-2 | Howard | 11 766 | 1950/herbarium | Deux-Branches, Dominica |

| NY 170046 | NY-4 | Mori | 24 694 | 1997/herbarium | S.n., Puerto Rico, USA |

| NY 214336 | NY-6 | Luteyn | 5118 | 1977/herbarium | S.n., Puerto Rico, USA |

| NY 32866 | NY-7 | Proctor | 44 637 | 1988/herbarium | S.n., Puerto Rico, USA |

| NY 1528297 | NY-8 | Baker | 6796 | 1986/herbarium | Morona-Santiago, Ecuador |

| Uleiorchis ulei | |||||

| NY 4170293 | NY-10 | Mori | 21 644 | 1990/herbarium | Eaux-Claire, French Guiana |

| Triphora trianthophoros | |||||

| OS | n/a | Freudenstein | 3033 | 2016/fresh | Shelby Co., Ohio, USA |

| Triphora aff. wagneri | |||||

| IBUG | n/a | Carrillo-Reyes & Kennedy | 4381 | 2004/fresh | Mascota, Jalisco, Mexico |

Sequencing

Illumina libraries were generated with the sparQ DNA Frag and Library Kit (Quantabio, Beverly, MA, USA), with 20–50 ng as input per sample. Because all herbarium-derived extractions showed some evidence of DNA fragmentation, the enzymatic shearing time was reduced to 1 min from the recommended 14 min (as used for fresh tissue-derived samples). Adapters were ligated and barcodes (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) added via 12–14 PCR cycles. Libraries were run on 1 % agarose gels, quantified with the Qubit High Sensitivity Assay, pooled at equimolar ratios, and subjected to quantitative PCR and fragment size analysis on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The nine libraries were sequenced with 54 others from other projects on an Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) NextSeq2000 v3 reagent flow cell (200 cycles) to generate approximately one billion 2 × 100-bp paired-end reads.

Assembly, annotation and alignment of plastomes

Reads were quality- and adapter-trimmed with fastp (Chen et al., 2018). We also trimmed poly-X tails using a 16-bp sliding window as in Barrett et al. (2024) to remove low-complexity tails in reads, which are common in two-channel sequence data such as those from Illumina NextSeq, and degraded samples from historical DNA. We specified a minimum read length of 75 bp for both reads (fastp parameters: -w 16 --trim_poly_g --trim_poly_x -l 75 --cut_right). Cleaned read data were assembled in GetOrganelle v.1.7.7.0 (Jin et al., 2020) and NOVOPlasty v.4.3.4 (Dierckxsens et al., 2017), followed by comparison of the assemblies and annotation with GESeq (Tillich et al., 2017) as in Barrett et al. (2024). Annotations of coding, non-intron-containing DNA sequences (CDSs) were verified with the ORF-finder application in Geneious v.10 (https://www.geneious.com/), and in a few cases adjustments to the start and stop codons were made manually. Annotations were deposited under NCBI GenBank accession numbers PP796630 and PP812541–PP812547. Newly generated plastomes of W. calcarata and T. trianthophoros were aligned with Nervilia fordii (NCBI GenBank accession number ON515491) and Gastrodia elata (accession number MF163256) in Mauve v.2.3.1 (Darling et al., 2010) with default parameters via the plugin for Geneious, and MAFFT v.7.471 (Katoh and Standley, 2013) was chosen as the sequence aligner. Further, all six accessions of W. calcarata were separately aligned with MAFFT (with ‘-auto’ parameters) for downstream comparisons.

Phylogenetic analyses

Whole plastome sequences were downloaded from NCBI GenBank for representatives of all five orchid subfamilies (Supplementary Data Fig. S3) and supplemented with gene sets from Serna-Sánchez et al. (2021). The primary focus in the current study was on the base of the epidendroids, including early-diverging epidendroid tribes Neottieae, Sobralieae, Triphoreae, Wullschlaegelieae, Nervilieae, Gastrodieae and Tropidieae. Non-orchid monocot outgroup taxa included were Mapania palustris (Cyperaceae), Iris sanguinea (Iridaceae) and Agave americana (Agavaceae) (from Serna-Sánchez et al., 2021). As no complete plastome data were available for Xerorchis (Xerorchideae) or Diceratostele (Triphoreae, subtribe Diceratostelinae), we included the rbcL gene from Diceratostele gabonensis (GenBank accession number AF074148) and the matK, psaB and rbcL genes from Xerorchis amazonica (GenBank accession numbers AF074148, AF263688 and AF074244, respectively).

GenBank flat files for each plastome were processed with PhyloSuite v.1.2.3 (Zhang et al., 2020), and all CDSs and ribosomal RNA genes (rDNA) were extracted and imported into Geneious. Sequences for each gene were then combined and initially aligned with MAFFT to inspect completeness, annotation errors or aberrant features. Genes were then aligned with MACSE v2 (Ranwez et al., 2018), a codon-aware aligner, under default parameters, removing terminal stop codons for downstream analyses. Alignments were concatenated in Geneious and analysed via maximum likelihood with IQ-TREE 2 (Minh et al., 2020). Because plastomes from several fully mycoheterotrophic lineages were included, we used models that explicitly incorporate heterotachy, or lineage-specific rate variation over time, via the GHOST model (Crotty et al., 2020). GHOST is an edge-unlinked mixture model consisting of several user-defined site classes that has been shown to effectively model heterotachy and consistently outperforms partition-based models for heterotachously evolved sequences, especially if a priori partitioning schemes are improperly identified (Crotty, 2017, Crotty et al., 2020; Crotty and Holland, 2022; Liu et al., 2023). GHOST does not require a priori partitioning. We limited our sampling to 72 taxa, as the number of parameters increases dramatically relative to the number of characters for the GHOST model, possibly leading to issues with parameter estimation (Crotty et al., 2020). After substitution model tests on the concatenated data with ModelFinder using the ‘-mrate’ option in IQ-TREE 2 (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017), we identified the GTR (general time-reversible) class to be the best fit (-mrate G,R,H). We analysed the data under an unpartitioned GTR+Γ+I model, and then under four edge-unlinked GHOST models with different numbers of site classes, with each class having their own set of base frequencies, edge lengths and model parameters. We tested four site-class scenarios, with two to eight site classes specified, i.e. GTR+FO*{2,4,6,8}. Results from these models were compared using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and BIC weights (Burnham and Anderson, 2004).

Because plastid genomes in heterotrophic lineages are known to display rampant gene loss (i.e. missing data) and accelerated substitution rates, we conducted a separate set of analyses on mitochondrial gene data, which are expected to be affected less by such phenomena (e.g. Lin et al., 2022). As a basis for our sampling, we used the mitochondrial gene sequences from Li et al. (2019), which included gene sets from 73 orchid species across all five subfamilies, and two non-orchid monocot outgroups, Phoenix dactylifera (Arecaceae) and Allium cepa (Amaryllidaceae). To generate gene sets from our newly sequenced accessions, we mapped reads to each mitochondrial CDS from Liparis bootanensis (Epidendroideae, Malaxideae), which was selected due to being among the most complete taxa from Li et al. (2019) in terms of mitochondrial gene sequence representation. Read pairs were mapped iteratively ten times in Geneious under stringent parameters (high-medium sensitivity), and the resulting consensus was trimmed to the reference sequence CDS and exon boundaries. The minimum coverage depth cutoff was set to 10×, and positions below this value were treated as missing data. We included both species of Triphora, one accession of W. calcarata, the single sequenced accession of U. ulei, and an accession of Degranvillea dermaptera from an earlier study (Barrett et al., 2024) (Table 2). Resulting consensus sequences were combined by gene with the other orchid sequences, and alignment and phylogenetic analyses were conducted as above for plastid gene sets.

Table 2.

Overview of Illumina read data, assembled plastome length and coverage depth.

| Sample | Species | Reads (raw) | Reads (clean) | Plastome length (bp) | Plastome coverage (×) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NY-1 | Wullschlaegelia calcarata | 43 875 847 | 29 301 433 | 36 750 | 311.48 |

| NY-2 | Wullschlaegelia calcarata | 13 915 236 | 8 216 646 | 36 981 | 231.46 |

| NY-4 | Wullschlaegelia calcarata | 14 833 826 | 11 322 549 | 37 030 | 102.52 |

| NY-6 | Wullschlaegelia calcarata | 11 724 187 | 4 103 884 | 36 994 | 28.41 |

| NY-7 | Wullschlaegelia calcarata | 57 833 295 | 36 116 597 | 37 012 | 348.55 |

| NY-8 | Wullschlaegelia calcarata | 6 682 462 | 4 986 439 | 37 008 | 113.2 |

| NY-10 | Uleiorchis ulei | 7 149 550 | 2 687 650 | n/a | 0.3* |

| n/a | Triphora trianthophoros | 4 127 125 | 3 899 084 | 151 899 | 64.4 |

| n/a | Triphora aff. wagneri | 9 125 423 | 8 491 076 | 153 852 | 115.5 |

*Coverage depth for U. ulei mapped to the plastome of Nervilia fordii (NCBI GenBank accession number ON515491).

We further conducted topology tests for the plastid and mitochondrial trees resulting from the optimal GHOST models (see below) in IQ-TREE 2 using the Shimodaira–Hasegawa (SH) test (Shimodaira and Hasegawa, 1999) and the approximately unbiased (AU) test (Shimodaira, 2002). We used a single constraint on the topologies for both trees, to match an early-diverging epidendroid clade recovered in Pérez-Escobar et al. (2024) based on nuclear gene coalescent analysis (i.e. a forced clade of Gastrodieae + Wullschlaegelieae). Analyses were conducted for constrained and unconstrained trees for both organellar datasets. Values of P < 0.05 were interpreted as significant evidence to reject the constrained topology. We further compared constrained trees with unconstrained trees from all analyses with the BIC and BIC weights. Lastly, we compared the relative root-to-tip branch lengths among heterotrophs and autotrophs for both plastid and mitochondrial trees, as well as the amount of missing data for each dataset via Wilcoxon rank sum tests in R (R Core Team, 2024).

Comparative analyses of plastomes

Representative species of Epidendroideae were tested for significantly relaxed or intensified selection using RELAX in HyPhy v.2.5.48 (Kosakovsky Pond et al., 2005; Wertheim et al., 2015). Included were seven fully mycoheterotrophic taxa [Aphyllorchis montana (GenBank accession number KU551262), Didymoplexis pallens (ON515488), Epipogium aphyllum (KJ772292), Epipogium roseum (KJ772291), Gastrodia elata (MN026874), Pogoniopsis schenkii (OP425397) and W. calcarata] and six leafy autotrophs [Dendrobium acinaciforme (LC636124), Holcoglossum flavescens (MK442925), N. fordii (ON515491), Sobralia callosa (KM032623), Spiranthes sinensis (OM314917) and T. trianthophoros]. Analyses were restricted to genes present and putatively functional in Wullschlaegelia. The analyses were repeated specifying only Wullschlaegelia as the test branch, to further investigate evidence for relaxed or intensified selection in that taxon. The resulting .json files from RELAX were visualized in HyPhy Vision (http://vision.hyphy.org/).

Coevol v.1.5 (Lartillot and Poujol, 2011) was used to identify correlations among substitution rates and several features of the plastome. We compared the same species as above in the RELAX analyses. Coevol models pairwise correlations among substitution rates and continuous traits using Bayesian Monte Carlo methods under a Brownian diffusion process, while controlling for phylogenetic relationships and multiple comparisons among other traits. Coevol estimates GC content, dS and dN, which are the synonymous and non-synonymous substitution rates, respectively. We included several plastome features, calculated as in Barrett et al. (2018, 2024), including: Length, the length in base pairs of the plastome; CDS, the number of putatively functional protein coding genes; IR-L, the length of the inverted repeat in base pairs; tRNA, the number of putatively functional transfer RNA genes; RTT, the root-to-tip branch lengths under the best-fit GHOST heterotachy model; Rep-20, the proportion of the plastome composed of dispersed repeats >20 bp in length; Msat, microsatellite density, or the proportion of the plastome characterized by microsatellite DNA; and DCJ, the double-cut-and-join distance, or the number of structural inversions in the plastome. We further conducted phylogenetic principal components analysis among plastome features, which accounts for phylogenetic non-independence among samples (Revell, 2009). Analysis was conducted with phytools v.2 in R (Revell, 2012, 2023), under a Brownian motion model and using the correlation matrix.

Comparative analyses of matK

We recorded the presence or absence of matK among a broad representative sample of publicly available mycoheterotrophic orchid plastomes, the presence of genes containing Group IIA introns, and whether they have retained or lost their introns. Genes with Group IIA introns are clpP (intron 1), trnA-UGC, trnI-GAU, trnK-UUU, trnV-UAC, atpF, rpl2 and the 3ʹ portion of rps12 (the intron between exons two and three). In addition to the RELAX analyses above, we conducted two additional tests in HyPhy to test for positive selection in matK, with the same defined foreground branches as above for RELAX: (1) aBSREL (adaptive branch-site REL test for episodic diversification; Smith et al., 2015) and (2) BUSTED (branch-site unrestricted statistical test for episodic diversification; Murrell et al., 2015).

Predicted amino acid sequences of matK were analysed for nine orchid species, with representative green, leafy species [Epipactis helleborine (GenBank accession number MH590351), Sobralia callosa (KM032623), Nervilia fordii (ON515491) and Holcoglossum amesianum (MK442924)] and fully mycoheterotrophic species [Aphyllorchis montana KU551262, Corallorhiza involuta (MG874038), Bletia (Hexalectris) warnockii (MK726073), Gastrodia elata (MF163256) and Wullschlaegelia calcarata] plus a non-monocot as a more phylogenetically distant reference taxon [Magnolia odora (AF123470)]. Each amino acid sequence was subjected to structural analysis via the Phyre2 server in batch mode, which compares tertiary protein structures using the PSIPRED Protein Structure Server (McGuffin et al., 2000; Buchan and Jones, 2019) and hidden Markov models (Kelley et al., 2015). The top-scoring structural model for each species was extracted for visualization and comparative analyses via the Dali web server (Holm, 2022). Dali calculates a z-score statistic for pairwise comparisons of structural similarity, with scores >20 indicating definitive homology. Dali was further used to construct a pairwise similarity matrix, a dendrogram based on average linkage for structural similarity, and a correspondence analysis based on z-scores. The predicted α-helix and β-sheet annotations were then added to the sequences in Geneious, which were aligned in MAFFT under the BLOSUM62 scoring matrix and ‘-auto’ parameters to compare structural conservation and variation.

Datasets are available at Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.10786936) and commands used are available via GitHub (https://github.com/barrettlab/2024_Wullschlaegelia_Epi_base/wiki/Commands-used-in-Wullschlaegelia-Epidendroid-base-MS).

RESULTS

Plastome structure

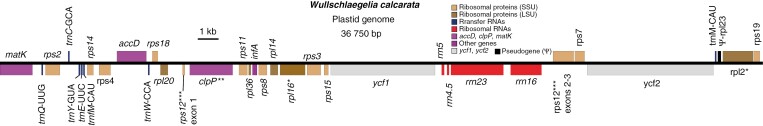

We assembled complete plastomes for six accessions of W. calcarata and a single accession for each of two species of Triphora (Table 2). Assemblies of U. ulei were unsuccessful with both GetOrganelle and NOVOPlasty. To investigate the latter, we mapped reads iteratively in Geneious to the plastomes of G. elata and Sobralia callosa and found that reads mapped only to portions of the 16S and 26S rRNA genes, with a few mapping to the 3ʹ end of accD and the rps12 second intron. Plastomes of W. calcarata ranged from 36 750 to 37 030 bp in length, with each having 22 CDSs, all 4 rRNA genes (rDNA), and 7 transfer RNA genes (tRNA; Fig. 1; Table 3). Four CDSs retain their introns, including 3ʹrps12. Most retained CDSs encode ribosomal protein subunits, with the addition of accD, clpP, matK, ycf1 and ycf2. A truncated fragment of the rpl23 gene was also detected and annotated. The inverted repeat region (IR) is lacking in W. calcarata, and nearly half of the plastome corresponds to genes found in the IR in other species (Fig. 1). The region corresponding to the large single copy (LSC) is greatly reduced relative to leafy taxa, and no remnants of the small single copy region (SSC) were detected. GC content in all six sequenced plastomes ranges from 34.0 to 34.1 %.

Fig. 1.

Plastome map of Wullschlaegelia calcarata accession NYBG Vincent #15 387 (Rio Grande, Puerto Rico, USA). *Gene contains one intron; **gene contains two introns (i.e. clpP); ***gene contains two cis-spliced exons and one trans-spliced exon (i.e. rps12).

Table 3.

Retained, putatively functional genes in Wullschlaegelia calcarata, separated by basic functional groups.

| Gene class | Genes retained in Wullschlaegelia calcarata |

|---|---|

| Photosynthesis | – |

| ATP synthesis | – |

| Transcription, translation | infA, rpl2*, rpl14, rpl16*, rpl20, rpl36, rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7, rps8, rps11, rps12***, rps14, rps15, rps18, rps19 |

| Ribosomal RNA | rrn4.5, rrn5, rrn16, rrn23 |

| Transfer RNA | trnC-GCA, trnE-UUC, trnfM-CAU, trnM-CAU, trnQ-UUG, trnW-CCA, trnY-GUA |

| Other | accD, clpP**, matK, ycf1, ycf2 |

–, No genes detected; *, contains one intron; **, contains two introns (i.e. clpP); ***, contains two cis-spliced and one trans-spliced exon (i.e. rps12).

Plastomes for T. trianthophoros and T. aff. wagneri are 151 899 and 153 825 bp in length, respectively. Notably, the IR region in both species is expanded into the region corresponding to the SSC, with IR lengths of 34 335 bp for T. trianthophoros and 35 212 bp for T. aff. wagneri. Both of these plastomes encode nearly all genes typically found in leafy, photosynthetic angiosperms, with the exception of NADPH dehydrogenase (ndh genes). A truncated pseudogene was detected for ndhB in the IR, which retains most of the 5ʹ exon and the intron, but is missing ~470 bp at the end of the 3ʹ exon. GC content for both plastomes is 36.5 %.

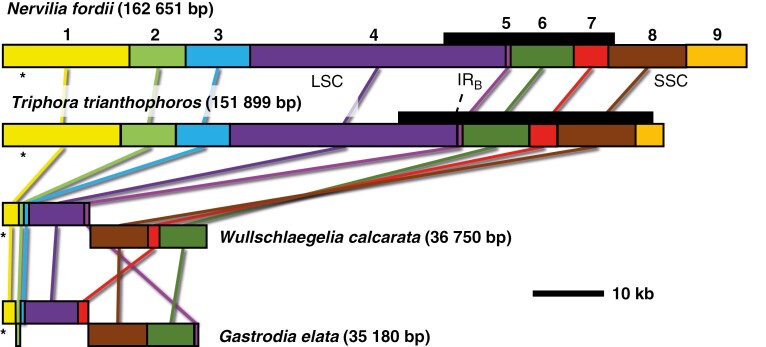

Plastome structural comparison of the leafy N. fordii and T. trianthophoros with the leafless W. calcarata and G. elata revealed striking length variation (Fig. 2). The length in Triphora is ~10 kb shorter than that in Nervilia, largely due to the loss of ndh genes in the former, despite Triphora having an IR that is 7811 bp longer than that in Nervilia. No other major structural rearrangements were detected between Nervilia and Triphora. The plastome of Wullschlaegelia is similar in size to that of G. elata (36 750 vs 35 180 bp in Gastrodia). Both leafless species lack an IR and show evidence of structural rearrangement. A total of nine locally collinear blocks (LCBs) were detected with Mauve, with LCBs 1–4 corresponding to the LSC and part of the IR, LCBs 5, 6, 7 and part of LCB 8 corresponding to the IR, and LCBs 8 and 9 corresponding to the SSC in Nervilia. Both leafless species have an inversion of a large region corresponding to the ancestral IR, with Gastrodia having an additional inversion in the region corresponding to the LSC (double-cut-and-join distances of 1 and 2 for Wullschlaegelia and Gastrodia relative to the two leafy species, respectively). Closer comparison of inversions between Wullschlaegelia and Gastrodia revealed further structural variation. LCB 9, corresponding to part of the SSC in Nervilia and all of the SSC in Triphora, is missing in both leafless species. The LCB order varies between Wullschlaegelia (1-2-3-4-5-8-7-6) and Gastrodia (1-3-2-4-7-8-6-5).

Fig. 2.

Structural comparison among representative early-diverging epidendroid plastomes from Mauve analysis. Colours indicate locally collinear blocks (LCBs) 1–9, listed above the plastome of Nervilia. Black bars above plastome maps for Nervilia and Triphora represent the inverted repeat (IR; with one copy removed); both Gastrodia and Wullschlaegelia lack an inverted repeat. Asterisks indicate the location of the matK gene.

Phylogenetic analyses

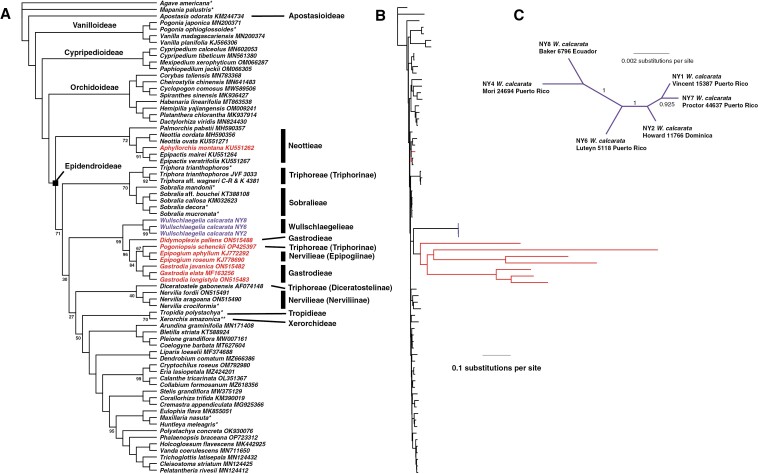

The final plastid gene matrix consisted of 72 genes (68 CDSs and 4 rDNAs), 88 268 aligned positions, 19 980 parsimony-informative characters, and 38.1 % gaps/missing data. Analyses under different rate classes of the GHOST heterotachy model clearly indicated that the model with six classes (GTR+FO*H6) was optimal (Table 4). The resulting tree generally had strong bootstrap support (BS), with the monophyly for each subfamily and relationships among them supported at BS = 100 (Fig. 3A). Moving from the basal node of Epidendroideae, tribe Neottieae formed a weakly supported clade sister to the remainder of the subfamily (BS = 72), with the next major branching point being another weakly supported clade of Triphora (Triphoreae) plus Sobralia (Sobralieae), which was sister to the remaining epidendroids (BS = 71). Support in general was low for the backbone relationships within Epidendroideae (Fig. 4A), with the next clade exclusively composed of fully mycoheterotrophic taxa with the exception of Aphyllorchis, which was placed with other members of Neottieae. Support for the monophyly of this grouping was strong (BS = 99), but this placement of the clade within the epidendroids was unsupported (BS = 30). Within this ‘mycoheterotrophic’ clade, three accessions of Wullschlaegelia were strongly supported as sister (BS = 99) to a clade of the remaining mycoheterotrophs. Didymoplexis (Gastrodieae) was sister to a clade composed of Pogoniopsis (Triphoreae: Triphorinae) plus two species of Epipogium (Nervilieae: Epipogiinae) (BS = 96), which in turn was sister to a clade of three species of Gastrodia (BS = 84). Altogether, this clade displayed extremely long branch lengths relative to all other accessions in the tree (Fig. 3B). The next clade to branch off had no support for its monophyly (BS = 40) nor its position within Epidendroideae (BS = 27) and contained three accessions of Nervilia (Nervilieae: Nerviliinae) sister to a single accession of Diceratostele (Triphoreae: Diceratostelinae). The next clade was composed of Tropidia and Xerorchis (BS = 70), but the relationship of this clade to the remaining Epidendroideae was not supported (BS = 50). Support for all relationships among the epidendroids included beyond this point was strong (minimum BS = 95).

Table 4.

Phylogenetic model comparisons for plastid and mitochondrial gene sets. GTR + Γ + I is an unpartitioned model, and GTR + FO*R{2–8} represent GHOST heterotachy models with two to eight rate classes, representing fully edge-unlinked models. Best-fit models appear in boldface. The constraint specifies monophyly of a clade containing Gastrodieae, Nervilieae and Wullschlaegelieae, following the recent nuclear gene coalescent analysis of Pérez-Escobar et al. (2024).

| Model | lnL | Number of parameters1 | BIC2 | ΔBIC3 | wBIC4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plastid | H1 (GTR+Γ+I) | −499 800 | 151 | 1 001 319 | 11 768 | 0 |

| H2 (GTR+FO*H2) | −497 445 | 299 | 998 295 | 8744 | 0 | |

| H4 (GTR+FO*H4) | −491 824 | 599 | 990 470 | 918 | 0 | |

| H6 (GTR+FO*H6) | −489 657 | 899 | 989 551 | 0 | 1 | |

| H8 (GTR+FO*H8) | −488 799 | 1199 | 991 253 | 1701 | 0 | |

| H6 (constrained) | −489 844 | 899 | 989 927 | 1534 | 0 | |

| Mitochondrial | H1 (GTR+Γ+I) | −160 290 | 171 | 322 360 | 5174 | 0 |

| H2 (GTR+FO*H2) | −157 686 | 339 | 318 902 | 1716 | 0 | |

| H4 (GTR+FO*H4) | −155 058 | 679 | 317 186 | 0 | 1 | |

| H6 (GTR+FO*H6) | −154 138 | 1019 | 318 886 | 1700 | 0 | |

| H8 (GTR+FO*H8) | −153 597 | 1359 | 321 343 | 4157 | 0 | |

| H4 (constrained) | −154 931 | 679 | 317 931 | 745 | 0 |

1Number of free parameters in each model. 2Bayesian Information criterion. 3Difference in BIC values between a particular model and the best model. 4BIC weight of the model.

Fig. 3.

(A) Plastid gene relationships based on the best-scoring GHOST heterotachy model (GTR+FO*H6). Epidendroid tribes (and subtribes) are listed to the right of the tree. Numbers adjacent to branches are bootstrap values based on 2000 ultrafast replicates in IQ-TREE 2 (no value indicates 100 % support). (B) Phylogram of the same tree as that in (A) showing relative estimates for branch lengths under the GHOST model. Taxa in red are fully mycoheterotrophic, while purple indicates W. calcarata. Reference taxa were acquired from NCBI GenBank or from Serna-Sánchez et al. (2021), with the latter indicated by an asterisk (*); **, matK, psaB and rbcL genes from Xerorchis amazonica (GenBank numbers AF074148, AF263688 and AF074244, respectively). (C) Unrooted phylogram among six accessions of W. calcarata based on whole aligned plastomes.

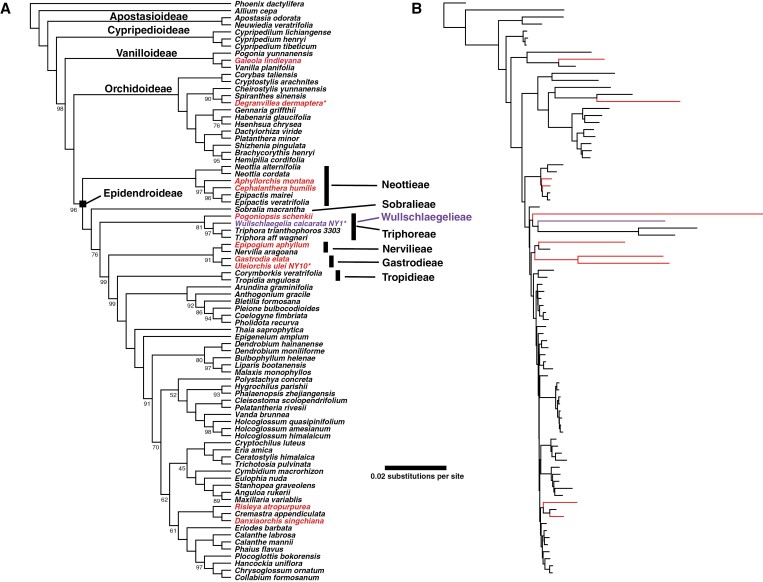

Fig. 4.

(A) Mitochondrial gene relationships based on the best-scoring GHOST heterotachy model (GTR+FO*H4). Epidendroid tribes are listed to the right of the tree. Numbers adjacent to branches are bootstrap values based on 2000 ultrafast pseudoreplicates in IQ-TREE 2. (B) Phylogram of the same tree as that in (A) showing relative estimates for branch lengths under the GHOST model. Taxa in red are fully mycoheterotrophic, while purple indicates W. calcarata. Reference taxa, excluding newly sequenced accessions of Triphora, Wullschlaegelia and Uleiorchis, were acquired from Li et al. (2019). Newly sequenced accessions are indicated by an asterisk (*).

A separate analysis of the six accessions of W. calcarata included here (37 301 aligned positions, 0.9 % gaps, and 67 parsimony-informative sites, best-fit model = F81+F+I, BIC = 106 853) placed two accessions from Puerto Rico, USA together (NY1, NY7; BS = 92.5), which were sister to an accession from Dominica (BS = 100; Fig. 3C). These were sister to a clade comprising the three other accessions, with accession NY4 (Puerto Rico) sister to accession NY8 (Ecuador), and collectively these were sister to accession NY6 (Puerto Rico), all with BS = 100. A closer analysis of polymorphism across the six plastomes revealed generally low GC content (~30 %) with the exception of the contiguous region containing the four rRNA genes (~50 %). Regions of the plastome with the highest nucleotide diversity are located between the rps18 and rpl20 genes and between rpl20 and the 5ʹ exon of rps12 (Supplementary Data Fig. S4). Other areas of high nucleotide diversity included both clpP introns, the rps15–ycf1 intergenic spacer, the ycf1–rrn5 spacer and the rps12 intron (between exons 2 and 3). Pairwise distances among the six accessions ranged from 74 between accessions NY2 (Dominica) and NY7 (Puerto Rico, USA) to 758 between accessions NY1 and NY4 (both from Puerto Rico, USA).

The final concatenated mitochondrial gene matrix consisted of 38 genes, 33 218 aligned positions, 4157 parsimony-informative sites and 9.2 % gaps/missing data. Mean coverage depths of newly sequenced accessions were 3.4× (s.d = 2.7) for T. trianthophoros, 8.2× (s.d = 3.9) for T. aff. wagneri, 20.0× (s.d. = 16.5), 9.5× (s.d. = 6.7) for W. calcarata, and 2.6× (s.d. = 20.4) for U. ulei. The GHOST model with four rate classes was chosen as the optimal model (GTR+FO*H4; Table 4). As with the plastid data, support for the monophyly of each subfamily and relationships among them was strong (minimum BS = 96), with the main difference being the relative branching order of subfamilies Vanilloideae and Cypripedioideae (Fig. 4). Support values were generally high for the basal-most splits within Epidendroideae. Tribe Neottieae formed a clade (BS = 100), and was sister to the remaining epidendroids, followed by Sobralia (Sobralieae; BS = 100). The next split (BS = 76) was a clade of Triphoreae and Wullschlaegelieae. Within this clade, Pogoniopsis (Triphoreae) was sister to a clade comprising Wullschlaegelia (BS = 81) and two species of Triphora (Triphoreae; BS = 97). The next split was strongly supported (BS = 99) and included a clade composed of Nervilieae and Gastrodieae (BS = 91). Within this clade, Epipogium and Nervilia (Nervilieae) were sister to Gastrodia and Uleiorchis (Gastrodieae), with both of these sister relationships having BS = 100. Corymborkis and Tropidia (Tropideae) comprised the next clade (BS = 100), and this clade was supported as sister to the remaining epidendroids (BS = 99).

A comparison of branch lengths (Fig. 4B) also revealed apparent long branches for most mycoheterotrophic taxa, especially for those near the base of Epidendroideae, but the overall magnitude of branch length differences between mycoheterotrophs and leafy species was less extreme for mitochondrial data relative to the pattern in the plastid data. Specifically, the mean relative branch length difference among heterotrophic and photosynthetic lineages was lower for mitochondrial data (Supplementary Data Fig. S5; ratio of heterotrophic:autotrophic root-to-tip branch lengths = 1.51; Wilcoxon W = 148, P = 0.001) than for plastid data (ratio = 6.63; W = 53, P < 0.00001). Additionally, the amount of missing data between heterotrophic vs autotrophic taxa was significant for plastid data (W = 10.5, P < 0.0001) but not for mitochondrial data (W = 273, P = 0.111).

We conducted topology tests under best-fit GHOST heterotachy models for both plastid and mitochondrial data (Table 5), forcing the tribes Wullschlaegelieae and Gastrodieae to form a clade, following a recent and densely sampled orchid phylogenomic analysis based on nuclear genes (Pérez-Escobar et al., 2024). For the plastid data, both SH and AU tests indicated that the constrained topology was significantly worse than the unconstrained topology (P < 0.001 for both tests). The same was true for the mitochondrial analyses, with both tests rejecting the constrained topology (P = 0.024 and 0.016 for SH and AU tests, respectively).

Table 5.

Topology tests among constrained and unconstrained tree topologies for mitochondrial and plastid gene set analyses, respectively. The constraint specifies monophyly of a clade containing Gastrodieae, Nervilieae and Wullschlaegelieae, following the recent nuclear gene coalescent analysis of Pérez-Escobar et al. (2024).

| Tree | LogL1 | ΔL2 | P-SH3 | Reject4 | P-AU5 | Reject4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTR + FO*H6 plastid | −489 786 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| GTR + FO*H6 plastid constrained | −489 864 | 77.658 | 0 | Yes | <0.001 | Yes |

| GTR + FO*H4 mitochondrial | −155 541 | 0 | 1 | 0.995 | ||

| GTR + FO*H4 mitochondrial constrained | −155 581 | 40.219 | 0.0239 | Yes | 0.016 | Yes |

1Likelihood score. 2Difference in likelihood between constrained and unconstrained topologies. 3Significance of Shimodaira–Hasegawa test. 4Whether or not the constrained topology could be statistically rejected. 5Significance of approximately unbiased test.

Comparative analyses of plastomes

Gene losses in W. calcarata, as well as overall genome size, indicate that its plastome can be considered to be in the late stages of reductive evolution (Fig. 5). The overall genome size and gene content is similar to that in Didymoplexis, Gastrodia, Epipogium, Degranvillea (Orchidoideae), Rhizanthella (Orchidoideae), Lecanorchis (Vanilloideae), and Yoania (Epidendroideae). Wullschlaegelia retains all five ‘core non-bioenergentic genes’ (sensuGraham et al., 2017: accD, clpP, trnE-UUC, ycf1 and ycf2). As with all late-stage heterotrophs, Wullschlaegelia retains no photosynthesis-related or atp genes and has a highly reduced set of tRNA genes. Wullschlaegelia retains a putatively functional copy of matK, which has been lost in many late-stage heterotrophs but retained in some others (e.g. some Gastrodia and Lecanorchis species; Fig. 5). Related to this, Wullschlaegelia also retains all Group IIA introns for intron-containing genes that have not been deleted. Analysis of selective regimes revealed significant relaxation and intensification for some genes (Table 6). When considering all mycoheterotrophs as test branches in RELAX, significant intensification of selection was detected for accD and rps18, while infA, rps11 and rps15 all showed significantly relaxed selection. Considering only Wullschlaegelia as a test branch, selection was significantly intensified for rps18 and significantly relaxed for infA.

Fig. 5.

Retained, putatively functional genes in representative orchid plastomes of different trophic modes. Gene colours indicate different functional complexes, with the five ‘core non-bioenergetic’ genes (sensuGraham et al., 2017) in yellow. Coloured bar on left indicates the trophic mode of each species: dark green, leafy autotrophic; light green, leafless partially mycoheterotrophic; magenta, leafless fully mycoheterotrophic. Wullschlaegelia calcarata is in purple text.

Table 6.

Results of RELAX analyses in HyPhy for each gene present in W. calcarata.

| All MH1 | Wullschlaegelia only2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Type3 | P-value4 | k 5 | LR6 | Type3 | P-value4 | k 5 | LR6 |

| accD | Intensification | 0.007 | 1.39 | 7.25 | Relaxation | 0.272 | 0.86 | 1.21 |

| clpP | Intensification | 0.393 | 1.13 | 0.73 | Intensification | 0.775 | 1.09 | 0.08 |

| infA | Relaxation | 0.032 | 0.65 | 4.61 | Relaxation | 0.025 | 0.51 | 5.04 |

| matK | Relaxation | 0.1 | 0.64 | 2.7 | Intensification | 0.954 | 1.03 | 0 |

| rpl2 | Intensification | 0.075 | 0.51 | 3.16 | Intensification | 0.979 | 1.01 | 0 |

| rpl14 | Intensification | 0.426 | 1.13 | 0.63 | Relaxation | 0.73 | 0.9 | 0.12 |

| rpl16 | Intensification | 0.154 | 1.3 | 2.03 | Intensification | 0.636 | 1.19 | 0.22 |

| rpl20 | Relaxation | 0.064 | 0.25 | 3.43 | Relaxation | 0.818 | 0.85 | 0.05 |

| rpl36 | Relaxation | 0.576 | 0.56 | 0.31 | Intensification | 0.338 | 2.6 | 0.92 |

| rps2 | Relaxation | 0.563 | 0.57 | 0.33 | Relaxation | 0.512 | 0.86 | 0.43 |

| rps3 | Relaxation | 0.275 | 0.81 | 1.19 | Relaxation | 0.171 | 0.73 | 1.87 |

| rps4 | Relaxation | 0.865 | 0.92 | 0.03 | Intensification | 0.59 | 1.17 | 0.29 |

| rps7 | Intensification | 0.377 | 1.94 | 0.78 | Relaxation | 0.182 | 0.48 | 1.78 |

| rps8 | Relaxation | 0.347 | 0.7 | 0.89 | Relaxation | 0.226 | 0.68 | 1.46 |

| rps11 | Relaxation | 0.027 | 0.57 | 4.92 | Intensification | 0.266 | 1.34 | 1.24 |

| rps12 | Intensification | 0.137 | 2.17 | 2.21 | Intensification | 0.617 | 3.91 | 0.25 |

| rps14 | Intensification | 0.74 | 1.1 | 0.11 | Relaxation | 0.734 | 0.85 | 0.12 |

| rps15 | Relaxation | 0.036 | 0.01 | 4.37 | Relaxation | 0.102 | 0.05 | 2.67 |

| rps18 | Intensification | 0.001 | 6.39 | 12 | Intensification | 0.007 | 3.5 | 7.31 |

| rps19 | Relaxation | 0.073 | 0.4 | 3.21 | Intensification | 0.483 | 1.67 | 0.49 |

| ycf1 | Intensification | 0.662 | 1.18 | 0.19 | Intensification | 0.212 | 2.34 | 1.56 |

| ycf2 | Relaxation | 0.306 | 0.88 | 1.05 | Relaxation | 0.176 | 0.78 | 1.83 |

1All mycoheterotrophic species specified as test branches. 2Only W. calcarata specified as the test branch. 3Whether selection is relaxed or intensified. 4Significance for relaxed or intensified selection. 5Selection intensity parameter, k < 1 indicating relaxation and k > 1 indicating intensification. 6Likelihood ratio statistic between the null and alternative models. Significance indicated in boldface.

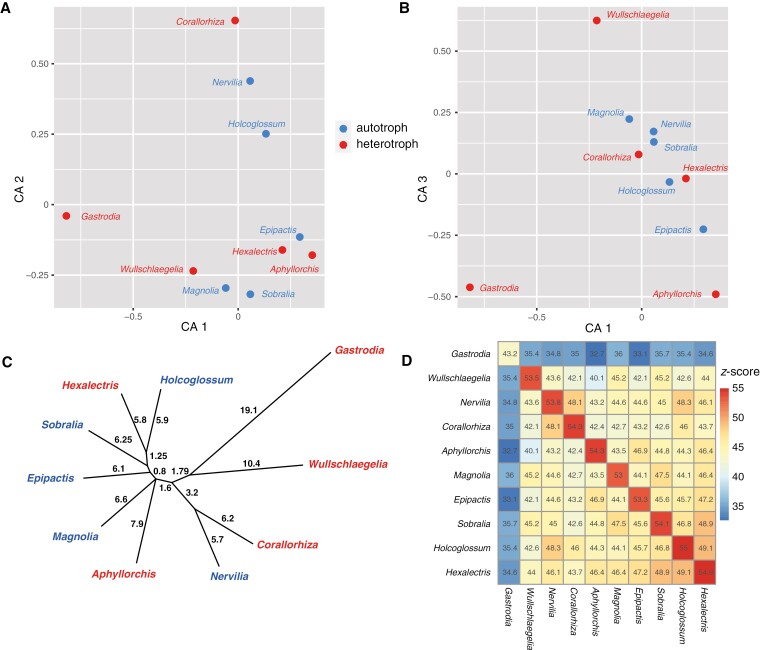

Phylo-comparative analysis with Coevol revealed significant correlations among features of the plastome among heterotrophic and autotrophic species (Table 7). The synonymous substitution rate (dS) was positively correlated with dN (non-synonymous substitution rate). Further, both dS and dN were correlated with all plastome features except for IR-L and Rep-20. Phylogenetic principal components analysis revealed three loose clusters among the 13 species included (Fig. 6). The first consists of all leafy, autotrophic taxa plus Aphyllorchis, which has the least degraded plastome among the fully mycoheterotrophic species. Epipogium roseum, Gastrodia and Wullschlaegelia formed another loose cluster, while Didymoplexis, Epipogium aphyllum and Pogoniopsis formed another. Phylogenetic principal component 1 (PPC1, 19.66 % of total variation) largely differentiated leafy vs leafless taxa, while PPC2 (8.15 % of total variation) separated the last two clusters mentioned above. PPC1 was positively correlated with RTT, Msat and DCJ, and negatively correlated with GC, tRNA, Length, CDS and, to a lesser extent, IR-L (Fig. 6, inset). PPC2 was correlated positively with IR-L and RTT, and negatively correlated Rep-20 and CDS (though weakly for the latter).

Table 7.

Results from COEVOL analysis of plastome features among selected leafy, autotrophic species (Spiranthes sinensis, Dendrobium acinaciforme, Triphora trianthophoros, Sobralia callosa, Holcoglossum flavescens and Nervilia fordii) and leafless, heterotrophic species (Didymoplexis pallens, Aphyllorchis montana, Pogoniopsis schenckii, Epipogium aphyllum, Gastrodia elata, Epipogium roseum and Wullschlaegelia calcarata). Numbers above the diagonal are correlation coefficients, with boldface numbers having significant posterior probabilities of <0.05 (negative correlation) or >0.95 (positive correlation).

| d S 1 | d N 2 | Length3 | CDS4 | IR-L5 | tRNA6 | RTT7 | GC8 | Rep-209 | Msat10 | DCJ11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d S | 1.00 | 0.96 | −0.89 | −0.86 | −0.37 | −0.81 | 0.84 | −0.68 | −0.04 | 0.71 | 0.70 |

| d N | 1.00 | −0.87 | −0.85 | −0.39 | −0.76 | 0.81 | −0.61 | −0.03 | 0.64 | 0.65 | |

| Length | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.47 | 0.91 | −0.91 | 0.78 | 0.06 | −0.79 | −0.82 | ||

| CDS | 1.00 | 0.37 | 0.83 | −0.90 | 0.69 | 0.23 | −0.67 | −0.70 | |||

| IR-L | 1.00 | 0.32 | −0.31 | 0.21 | −0.43 | −0.35 | −0.49 | ||||

| tRNA | 1.00 | −0.84 | 0.91 | 0.21 | −0.89 | −0.87 | |||||

| RTT | 1.00 | −0.75 | −0.15 | 0.69 | 0.73 | ||||||

| GC | 1.00 | 0.21 | −0.88 | −0.78 | |||||||

| Rep-20 | 1.00 | −0.10 | −0.03 | ||||||||

| Msat | 1.00 | 0.84 | |||||||||

| DCJ | 1.00 | ||||||||||

1Synonymous substitution rate. 2Non-synonymous substitution rate. 3Length of the plastome in base pairs. 4Number of putatively functional protein coding genes. 5Length of inverted repeat in base pairs. 6Number of putatively functional tRNA genes. 7Root-to-tip branch lengths under the GHOST heterotachy model with six rate mixture classes. 8GC content of the plastome. 9Proportion of the plastomes composed of dispersed repeats >20 bp in length. 10Proportion of the plastome characterized by microsatellite DNA. 11Double-cut-and-join distance, or the number of structural inversions in the plastomes.

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic principal components analysis (PPCA) of nine log-transformed plastome features. Red font indicates leafless, fully mycoheterotrophic species, blue font indicates leafy, autotrophic species. Inset shows the PPCA biplot, with feature names defined in the caption of Table 7.

Comparative analyses of matK

Analysis of the presence or absence of matK and the Group IIA introns that matK processes for a broad range of mycoheterotrophic orchid taxa is shown in Supplementary Data Fig. S6. This gene has been lost in many ‘advanced’ or late-stage heterotrophs, including Pogoniopsis, Epipogium, several (but not all) species of Gastrodia, Yoania, Degranvillea, Didymoplexis and Rhizanthella, and one species of Neottia, N. nidus-avis. All tRNA genes containing Group IIA introns have been lost in nearly all taxa that lack matK, with the exception of trnA-UGC in N. nidus-avis, which retains its intron. Group IIA introns have been lost, but their containing genes retained, in only three species: Pogoniopsis schenkii (clpP intron 2, rpl2 and rps12), Epipogium aphyllum (clpP intron 2 and rps12), and Epigonium roseum (rps12). No species that retains matK has lost all of the genes containing Group IIA introns, though several taxa have lost all or most tRNA genes containing introns and atpF; all of these taxa retain clpP and rpl2 with their introns. Although matK did not display evidence of relaxed or intensified selection in those heterotrophic species retaining it (Table 6), there was evidence for positive episodic selection in Wullschlaegelia based on the aBSREL test in HyPhy [B = 0.15, likelihood ratio (LR) = 5.94, P = 0.0183] but not in Gastrodia (B = 0.32, LR = 1.62, P = 0.1742) or Aphyllorchis (B = 0.03, LR = 0.008, P = 0.4845). A further investigation across sites of the matK gene with BUSTED did not detect significant overall positive selection (P = 0.083), but identified a single codon surpassing the evidence ratio threshold of 10 (codon 20), which encodes a lysine residue (AAA) in all taxa but Triphora (arginine, AGG) and Wullschlaegelia (phenylalanine, TTT).

Comparison of matK structural distances based on Dali z-scores is shown in the correspondence analysis (CA) in Fig. 7A, B. CA axis 1 separated Gastrodia from the remaining taxa, and the same was true for Wullschlaegelia to a lesser extent (Fig. 7A). CA axis 2 separated the mycoheterotrophic Corallorhiza and the autotrophic Nervilia and Holcoglossum from the remaining taxa (Fig. 7A). CA axis 3 separated Gastrodia and Aphyllorchis from the remaining taxa, but also differentiated Wullschlaegelia in the opposite direction (Fig. 7B). Cluster analysis of Dali z-score distances clearly showed that Gastrodia and Wullschlaegelia have the two most divergent structures, and further that they are each other’s closest relatives in terms of predicted matK structure (Fig. 7C). Pairwise comparison of z-scores showed that Gastrodia is the most structurally divergent (z-score range in all comparisons 32.7–36.0), followed by Wullschlaegelia and Aphyllorchis (ranges 40.1–45.2 and 40.1–46.9, respectively, not including the comparisons with Gastrodia; Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Structural analysis of Dali z-scores for predicted matK gene products among representative leafy, autotrophic (blue) and leafless, fully heterotrophic (red) epidendroid orchids. (A, B) Correspondence analysis of z-scores for axes 1 vs 2 and 1 vs 3, respectively. (C) Average linkage dendrogram based on the pairwise z-score matrix showing divergence in structural similarity. (D) Heat map of pairwise z-scores, with lower structural similarity shown in in blue and higher similarity in orange-red.

Comparison of structural annotations of matK along the predicted amino acid alignment revealed some notable patterns of variation (Supplementary Data Figs S7 and S8). Most apparent was a 5ʹ truncation of matK in Gastrodia, which contained a β-sheet in place of an α-helix in all other taxa between alignment positions 100 and 120. Both Gastrodia and Wullschlaegelia had a predicted β-sheet shared with no other taxa between two α-helices at approximately position 160. The regions corresponding to the Tether and Domain X appeared to be highly conserved, with the exception a deletion near the 3ʹ end of Domain X in Gastrodia, but that deletion was not predicted to have a major effect on the 3D protein structure, as Gastrodia retains an α-helix in that region shared with all other taxa. A closer look at the predicted 3-D structures for matK revealed that all taxa appear to have highly conserved structures for both the Tether and Domain X. The two main differences in overall 3-D structure are a missing β-sheet in Wullschlaegelia and Gastrodia (arrows at the top right of each structural model in Supplementary Data Fig. S7), and further a missing α-helix in the same region, and a missing ‘second loop’ in Gastrodia (arrow at top left in Supplementary Data Fig. S7 for Gastrodia).

DISCUSSION

Plastome structure

The plastome size and gene content of Wullschlaegelia are comparable to the most severely degraded plastomes among Orchidaceae, including Epipogium, Degranvillea, Gastrodia, Yoania and to a lesser extent Pogoniopsis, the most degraded orchid plastome sequenced to date (Figs 1, 2 and 5; Klimpert et al., 2022). The complete loss of the IR in Wullschlaegelia is shared with other late-stage heterotrophic orchid plastomes (Epipogium roseum, several species of Gastrodia; Fig. 5; Schelkunov et al., 2015; Wen et al., 2022). Only a single remnant pseudogene was detected (Ψ-rpl23) in the plastome of Wullschlaegelia, suggesting that any ancestral pseudogenes in the lineage leading to Wullschlaegelia have ultimately been deleted over time. No remnants of the ancestral SSC were detected, with ~60 % of the plastome comprising the ancestral IR region. Though sampling across the range was limited, the finding of four divergent accessions from Puerto Rico suggests that populations of W. calcarata may carry more plastid genomic diversity than may be expected for a rare, predominantly selfing orchid with presumably low population sizes. In fact, all individuals of this species from Puerto Rico were found to be completely cleistogamous in a previous study (Bergman et al., 2006). Based on our findings, we hypothesize there may be little population structure in this species across its broad range, as has been observed in some other leafless heterotrophs, e.g. in Corallorhiza bentleyi from the eastern USA (Fama et al., 2021) and Epipogium aphyllum across Eurasia (Minasievich et al., 2022). This is counter to what might be expected for heterotrophic orchids, which typically have small population sizes, are patchily distributed, and are prone to selfing; all of these factors would predict low genetic diversity within populations and possibly high population structure due to the effects of genetic drift. The reasons for deviation from these expected patterns are unknown and certainly worthy of future investigation. Further sampling of populations of W. calcarata from different regions and the sequencing of plastomes, nuclear SNP data and fungal hosts would go a long way in revealing useful information for the conservation of genetic variation in this species.

Phylogenetic analyses

As with other mega-diverse clades, resolution of higher-level orchid groups and the relationships among them, especially during the era when morphological data predominated, was difficult. A case in point is the epidendroids. A core group of ‘advanced’ epidendroids, defined by incumbent anthers, firm pollinia, and often highly developed cellular pollinium stalks, was evident from early in the history of orchid classification systems (e.g. Lindley, 1826) – these were often epiphytes as well. Similarly, the orchidoid taxon we today recognize as Orchideae was also distinct, united by sectile pollinia and well-developed caudicular pollinium stalks (this group was also recognized by Lindley, 1826). The cypripedoids, with their pair of fertile anthers, were also distinct. Over the next 150 years, much new orchid diversity was discovered, some of it fitting into these groups, but much of it comprising an assemblage of species with few apomorphic characters linking them clearly with any of these well-marked groups. Hence, many of the genera that are now known to fall at the base of the epidendroids were previously placed with other relatively plesiomorphic genera without clear ties. The latter include genera belonging to the currently recognized Diurideae, Goodyerinae, Spiranthinae, Cranichidinae and Vanillinae. They were often placed together in a higher-level group at some rank (Neottieae, Neottioideae) and known commonly as the ‘neottioid’ orchids, exemplified by the leafless Neottia nidus-avis that embodied many of those features. This assemblage contained most of the soft-pollinium species that have none or little in the way of pollinium stalks and have a more or less erect anther. Most are terrestrial. A group of this type existed in systems of the later 19th and 20th centuries (e.g. Pfitzer, 1887; Schlechter, 1926; Dressler and Dodson, 1960) until the advent of explicit phylogenetic analyses across the family. Some genera of particular interest in the current study (Wullshlaegelia, Epipogium and Gastrodia) floated among the epidendroids and orchidoids because they have at least semi-incumbent anthers that could link them to epidendroids and sectile pollinia that could link them to orchidoids, although the nature and arrangement of their massulae is somewhat different from true orchidoid sectile pollinia (Freudenstein and Rasmussen, 1996). The fact that they are leafless made their placement even more difficult because of the relative paucity of morphological characters.

The morphological phylogenetic analyses of Burns-Balogh and Funk (1986) and Freudenstein and Rasmussen (1999) made some progress in sorting the neottioid groups between the orchidoid and epidendroid sides of the tree, but it was the advent of DNA sequence data and its application across the family, beginning with Chase et al., (1994) and continuing with Cameron et al., 1999, that really began to clarify the picture of relationships among orchid subfamilies. In particular, the recognition of the vanilloids as a distinct lineage near the base of the family revealed the convergent nature of the incumbent anther in the vanilloids and epidendroids and made sense of the otherwise largely plesiomorphic features of vanilloids. As important was the sorting of the remaining neottioid genera into groups at the bases of Orchidoideae and Epidendroideae, making it clear that they did not comprise a monophyletic group but rather embodied the plesiomorphic elements in those two subfamilies. Subsequent broad-scale molecular analyses have confirmed the disparate placement of the neottioids and provided increasing support for structure at the base of Epidendroideae, but the affinities of many leafless epidendroids remain elusive (Rothacker, 2007; Górniak et al., 2010; Freudenstein and Chase, 2015; Givnish et al., 2015; Li et al., 2019; Pérez-Escobar et al., 2021; Serna-Sánchez et al., 2021). Dressler (1993) called the leafy and leafless ‘primitive’ Epidendroideae ‘especially troublesome’.

Our findings based on phylogenetic analyses of plastid and mitochondrial gene sets both corroborate and differ from other recent studies based on plastid, mitochondrial and nuclear datasets (Figs 3, 4 and 8). Both of our organellar analyses place Neottieae and then Sobralieae as the first two clades to diverge at the base of Epidendroideae, respectively. This structure was also recovered based on multiple genes from all three genomes (Freudenstein and Chase, 2015), a nearly complete plastid gene set (Serna-Sánchez et al., 2021), coalescent analysis of nuclear sequence capture data using the Angiosperms353 bait set (Pérez-Escobar et al., 2021, 2024; although Xerorchideae was placed as sister to Sobralieae in the latter study), and transcriptome data (Zhang et al., 2023). From this point on, the topologies in our study and previous studies begin to disagree, highlighting the degree of difficulty in resolving early-diverging epidendroid relationships. Our plastid analysis placed Triphoreae as sister to Sobralieae, which is not seen in any other analyses published to date (Fig. 8). Our mitochondrial analysis placed Tropideae as sister to the remaining ‘higher’ or ‘core’ epidendroids, as did the nuclear studies of Pérez-Escobar et al. (2021, 2024) and Zhang et al. (2023). Our mitochondrial analysis placed Wullschlaegelieae as nested within Triphoreae (i.e. sister to Triphora, and this clade collectively sister to Pogoniopsis; Figs 4 and 8). To our knowledge, this is the first time this relationship has been recovered in any study with moderate to strong support. Wullschlaegelieae was placed as sister to Xerorchideae, collectively sister to Tropideae, in Górniak et al. (2010) based on the nuclear Xdh gene, and in the multigene analysis of Freudenstein and Chase (2015), while in the nuclear analysis of Pérez-Escobar et al. (2024) Wullschlaegelieae was placed as sister to Gastrodieae. Wullschlaegelieae was not included in other studies. Our topology tests constraining a clade of (Wullschlaegelieae, Gastrodieae) in accordance with Pérez-Escobar et al. (2024) rejected this topology based on plastid and mitochondrial data. Concerning the plastid analysis, we view this finding not as evidence against nuclear findings, but rather as evidence of conflict between organellar and nuclear datasets. However, it should be noted that Pérez-Escobar et al. (2021, 2024) did not include representatives of Triphoreae. Further, support at the epidendroid base was weak based on nuclear sequence capture data in Pérez-Escobar et al. (2024), especially for the recovered sister relationship between Wullschlaegelieae and Gastrodieae, with only three gene trees being concordant with this node in the species tree estimate, while 51 gene trees were discordant. Future studies should employ data from all three genomes and increased taxon sampling in this part of the orchid tree to more closely investigate patterns of support and congruence.

Fig. 8.

Representative topology summaries for early-diverging Epidendroideae from previous studies and the current study. Analyses including Wullschlaegelia are indicated in purple. The solid square indicates the node constrained in topology tests (Wullschlaegelieae, Gastrodieae). Support values adjacent to branches are as follows: Freudenstein and Chase (2015), maximum likelihood (ML) bootstrap; Serna-Sanchez et al. (2021), maximum likelihood bootstrap; Pérez-Escobar et al. (2024), number of gene trees concordant (top) and discordant (bottom) with the inferred species tree; Zhang et al. (2023), maximum likelihood bootstrap support for all gene trees for a particular node (e.g. >70 indicates that all gene trees received at least 70 % support); current study (plastome and mitochondrial genes), maximum likelihood bootstrap. Asterisk and square in the summary tree from Pérez-Escobar et al. (2024) indicate a non-monophyletic Neottieae and the node used for topology tests in the current study, respectively.

Wullschlaegelia has long been problematic because of its leafless nature and reduced floral morphology. Dressler (1980) called it an ‘orphan’ and created a tribe for it because he was unsure where to place it. The overall morphological reduction and selfing nature of the flowers have led to the situation where there are no clearly derived morphological features that link it to other taxa. Sectile pollinia are perhaps the most unusual feature, being limited mainly to Orchidoideae except for a few epidendroid genera at the base of the subfamily. Hence, Wullschlaegelia could share this as a synapomorphy with Gastrodia, Epipogium, Stereosandra, Nervilia, Tropidia and Corymborkis among early-diverging epidendroids. However, sectile pollinia may also characterize a grade among these early-diverging epidendroids and not represent a synapomorphy, as suggested by the phylogenomic analysis of Pérez-Escobar et al. (2021). Stern et al. (1993a, b) characterized spherical amyloplasts (calling them ‘spiranthosomes’) from the root cortex of spiranthoid orchids (Cranichideae; Orchidoideae) and believed they might be limited to that group. Soon thereafter, Stern (1999) found them in Wullschlaegelia and Uleiorchis, and Stern and Judd (1999) found them in the stems of Vanilla, indicating that they are more broadly distributed than originally thought; this pattern suggests they may be a plesiomorphic feature in Wullschlaegelia and Uleiorchis, and not one that links them. An analysis of 18S rDNA sequences suggested that Wullschlaegelia might be allied to Calypsoinae (Molvray et al., 2000) but no subsequent analyses have confirmed that relationship. From a geographic perspective, our mitochondrial analysis reveals an interesting pattern at the base of Epidendroideae. The clade of [Pogoniopsis (Wullschlaegelia, Triphora)] is composed fully of New World genera, while the clade of [(Epipogium, Nervilia), (Gastrodia, Uleiorchis)] is largely Old World, with the exception of the Central/South American Uleiorchis, which was strongly supported as being placed in Gastrodieae. The maximum likelihood analysis of Klimpert et al. (2022) found moderate support for the placement of Pogoniopsis as sister to Sobralia based on mitochondrial DNA, but that study did not include any representatives of Triphora, Wullschlaegelia, Epipogium or Gastrodia.

Even employing best-fit models explicitly addressing heterotachy, our plastome analyses reveal a long-branched, ‘mycoheterotrophic’ clade comprising Wullschlaegelieae, Gastrodieae, Epipogium (Nervilieae) and Pogoniopsis (Triphoreae) (Figs 3 and 8), which Lam et al. (2018) refer to as a ‘long-branch attractor’ clade. Thus, our interpretation of the strong support for this clade is that significantly elevated substitution rates and large amounts of missing data (Supplementary Data Fig. S5) mean that the plastome may not be a reliable source of character information for the placement of heterotrophic lineages in this part of the epidendroid tree, as has been postulated for other parts of the monocot tree containing heterotrophs (e.g. Lam et al., 2018; Klimpert et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2022). While our mitochondrial analysis also reveals extremely long branches for early-diverging heterotrophic epidendroids, the ratio of branch lengths among heterotrophic and photosynthetic lineages is lower relative to that based on plastid data, and missing data are less of a problem for mitochondrial data in terms of physical losses from the genome (Supplementary Data Fig. S5). Unlinked mixture (i.e. heterotachy) models are extremely parameter-rich, and the number of parameters increases rapidly with the number of taxa, as each branch has its own set of parameters for each rate class (Crotty et al., 2020). For unlinked models like GHOST, larger taxon samples may lead to overparameterization, a situation in which the number of parameters exceeds the number of data points needed to estimate those parameters accurately (Tuffley and Steel, 1997; Steel, 2005; Holder et al., 2010). For example, an analysis with 200 taxa (n) and 6 rate classes (k) would yield k × (2n − 3) or 2382 free branch parameters under the GHOST model. The plastome, even in autotrophic species, has a finite number of characters, which is often significantly fewer for heterotrophic lineages, and thus there are limits on the level of taxon sampling possible in terms of the ability to accurately estimate parameters under current heterotachy models.

The epidendroid base has been a major challenge from a systematics perspective for several reasons, in a way representing a ‘perfect storm’. First, the hypothesized rapid divergence among the early splitting epidendroid lineages means that opportunities for incomplete lineage sorting and deep coalescence were rife (e.g. Pamilo and Nei, 1988; Maddison, 1997; Freudenstein et al., 2004; Maddison and Knowles, 2006; Van Den Berg et al., 2005; Carstens and Knowles, 2007; Knowles and Chan, 2008; Xi et al., 2014; Freudenstein and Chase, 2015; Zhang et al., 2023; Pérez-Escobar et al., 2024). Second, the concentration of leafless, heterotrophic lineages with accelerated substitution rates and high levels of missing plastid sequence (Gastrodieae, Wullschlaegelia, Epipogium, Pogoniopsis and some members of Neottieae) make the problem worse, and the placement of these lineages continues to be an issue in orchid systematics. Nuclear phylogenomic datasets based on the Angiosperms353 probe set vs transcriptomes reveal conflict at the epidendroid base, especially with respect to the relative branching orders of Xerorchideae and Sobralieae, though differences in sampling of early-diverging epidendroid tribes between these studies makes comparison difficult (Fig. 8; Pérez-Escobar et al., 2021, 2024; Zhang et al., 2023).

Even multilocus, nuclear sequence capture approaches may fail to resolve the base of the epidendroids because of gene tree estimation errors. First, many of the most conserved, low-copy nuclear loci among angiosperms have photosynthetic or chloroplastic functions, which are among the most useful for designing sequence capture probe kits such as Angiosperms353 (Johnson et al., 2019). Many of these are expected to be missing or highly modified in late-stage heterotrophs (e.g. Yuan et al., 2018). Model mis-specification and associated gene tree error remain a major source of bias in phylogenomic studies (e.g. Mirarab et al., 2021). For example, if heterotachy affects a significant number of loci in a dataset (e.g. Gastrodia, Pogoniopsis and Wullschlaegelia), then the ability to apply parameter-rich models (e.g. GHOST) based on the relatively short alignments for gene tree estimation may pose a major limitation. A common approach in such studies is to remove long-branch ‘outlier’ taxa from gene trees based on some relative length criterion, which is often assumed to stem from orthology mis-assessment, mis-alignment, pseudogenes, and other causes (e.g. TreeShrink; Mai and Mirarab, 2018). However, doing so is not guaranteed to distinguish between true signal in lineages with accelerated overall substitution rates in heterotrophic lineages vs the presumption of upstream errors that may lead to long branches. This highlights the need for more research on dealing with the effects of heterotachy with such data, as these types of datasets are increasingly applied to megadiverse clades such as the orchids, sampling thousands of species (e.g. Mandel et al., 2017; Pérez-Escobar et al., 2024).

Comparative analyses of plastomes

The plastome of Wullschlaegelia is that of a late-stage, highly degraded heterotroph, retaining only 33 genes, and representing a 77 % reduction in size from the autotrophic Nervilia (Figs 1 and 2; Table 3). Wullschlaegelia is similar in total functional gene content to Didymoplexis, Epipogium and Gastrodia (Fig. 5). The tempo of plastome degradation is a key question in plant organellar phylogenomics: how rapidly does plastome degradation occur after divergence from leafy ancestors? Phylogenetic uncertainty, drastically increased substitution rates, extinction of putatively intermediate forms and a lack of reliable fossils for calibration all hamper progress in answering this question. As with the aforementioned lineages, Wullschlaegelia retains no genes directly or indirectly related to photosynthesis (ndh, psa, psb, rbcL, rpo, atp), comprising only ribosomal protein subunit genes (rpl, rps), matK, a handful of tRNA genes and the five ‘core non-bioenergetic’ genes sensuGraham et al. (2017). As more heterotrophic plastomes are sequenced (including orchids), a pattern is emerging that indicates this may be a common sticking point, or point of stasis, between (1) plastomes with degraded photosynthetic apparatus only, and (2) plastomes that seemingly have gone ‘off the rails’, spiralling towards complete loss of the plastome (e.g. Molina et al., 2014; Bellot and Renner, 2016; Lim et al., 2016; Jost et al., 2022; Klimpert et al., 2022; Garrett et al., 2023). Wullschlaegelia appears to fit into ‘stage 5’ of plastome degradation following the conceptual models of Barrett and Davis (2012) and Barrett et al. (2014), and in the latter portion of the spectrum of reductive evolution according to the model of Graham et al. (2017). Such punctuated equilibria have been suggested along the path to plastome miniaturization in heterotrophs (e.g. Wicke et al., 2016; Schneider et al., 2018; Wicke and Naumann, 2018; Barrett et al., 2020), but this is a difficult hypothesis to test given the sparsely sampled heterotrophic plastomes and the absence of extant, possibly transitional, forms in many of these lineages due to presumed extinction.

A notable feature of these late-stage heterotrophic plastomes is the nearly complete lack of remnant pseudogenes, all of which have presumably been deleted, leaving the appearance of a ‘lean’ or ‘clean’ genome. This contrasts with the patterns observed in nuclear and mitochondrial genomes of heterotrophs, which in some cases appear to become ‘bloated’ over evolutionary time (e.g. Yuan et al., 2018; Ibiapino et al., 2020; Lyko and Wicke, 2021). It is unknown why these genomic size increases have occurred, but possibilities include rampant expansion of repetitive elements (e.g. transposons), host-to-parasite gene transfers, or genomic reconfiguration and gene family expansion associated with novel functions. Regardless, there is clearly a consistent, convergent trend of reduction in plastid genomes among all heterotrophic lineages studied to date that often contrasts with the situation in other genomic compartments, suggesting that smaller, compact plastomes may be the product of directional selection rather than just a relaxation of negative selection.