Abstract

A high-fat diet and physical inactivity are key contributors to obesity, predisposing individuals to various chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, which involve multiple organs and tissues. To better understand the role of multi-organ interaction mechanisms in the rising incidence of obesity and its associated chronic conditions, treatment and prevention strategies are being extensively investigated. This review examines the signaling mechanisms between different tissues and organs, with a particular focus on the crosstalk between adipose tissue and the muscle, brain, liver, and heart, and potentially offers new strategies for the treatment and management of obesity and its complications.

Keywords: Obesity, Fat tissue, Muscle, Brain, Liver, Heart, Signaling mechanisms

Introduction

Obesity is a disease that leads to a systemic chronic inflammatory response, the increase of which may lead to serious illnesses, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, osteoarthritis, and hyperlipidemia, and has even been linked to mental disorders [1, 2]. Chemical and surgical denervation studies have shown that innervation of adipose tissue is critical for the maintenance of normal metabolism and health and that synapses in obese adipose tissue are reduced in the presence of various metabolic disorders [3]. A recent study found that obese leptin-resistant animals also exhibit reduced sympathetic innervation of adipose nerves, leading to inflammation of adipose tissue that primarily affects sympathetic nerve fibers within the fat [4].

Studies have shown that obesity is associated with muscle dysfunction, and that chronic inflammation and metabolic abnormalities associated with obesity damage muscle tissue, leading to a decrease in muscle mass and function, which also includes a decrease in muscle strength and endurance [5]. Obesity is also associated with a higher risk of cognitive decline, structural brain changes, and increased risk of neurodegenerative diseases [6]. Chemical and surgical denervation studies have shown that innervation of adipose tissue is critical for maintaining normal metabolism and health, and that in the presence of metabolic disorders, synapses are reduced in obese adipose tissue [7]. Common heart problems in patients with obesity include hypertension, coronary artery disease, and heart failure, and the increased stress on the heart due to obesity causes structural and functional changes in the heart [8]. For the liver, long-term accumulation of liver fat increases the likelihood of hepatitis, liver fibrosis and even cirrhosis. Thus, obesity not only triggers systemic inflammation, but also negatively affects multiple organs and systems, including muscles, nerves, liver, and heart, and exacerbates the development of a wide range of chronic diseases. This broad impact highlights the need for in-depth research on obesity-related mechanisms and for new treatment directions. By precisely targeting metabolic factors and signaling pathways, new approaches to obesity treatment show promise for enhancing metabolic health and enabling personalized therapy.

Types and role of adipose tissue

White adipose tissue

White adipose tissue (WAT) is found in various depots throughout the body. It is less vascularized and innervated than brown adipose tissue (BAT), consists of large adipocytes with individual lipid droplets and fewer mitochondria, and plays a key role in regulating the body's energy status and metabolism [9]. A variety of cell types are present in the WAT, including adipocytes, immune cells, endothelial cells, stromal cells, and peripheral nerves which orchestrate the functions of lipid storage, lipid hydrolysis, and oxidation. WAT also serve as important endocrine cells, secreting adipokines including leptin and adiponectin to regulate metabolic activities, such as food intake and insulin sensitivity [10]. WAT is highly physiologically plastic; exposure to cold or beta-adrenergic receptor (beta3) agonists promotes adipocyte catabolism and can induce beneficial adipocyte subpopulations [11]. WAT depots include visceral white adipose tissue, subcutaneous white adipose tissue, and mammary adipose tissue [12]. In addition to expanding healthy adipose tissue and preventing triglyceride accumulation in other organs, WAT secretes various hormones and metabolites that help regulate the body's energy balance [13].

Brown adipose tissue

BAT is more vascularized and contains numerous small lipid droplets of varying sizes. Unlike white adipocytes, brown adipocytes are smaller, polygonal, and rich in highly cytochrome-rich mitochondria [14]. Derived from muscle precursor cells, brown adipocytes store energy in lipid droplets and utilize it through cyclic AMP protein kinase A signaling, enabling lipolysis-induced thermogenesis and maintaining this state throughout life [15]. During cold acclimation, BAT recruitment occurs, involving the secretion of factors known as batokines. For instance, during cold exposure, BAT is activated, leading to a significant increase in the expression and secretion of essential batokines, such as fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21). FGF21, produced in both BAT and the liver, plays a critical role in promoting fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial heat production by upregulating uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), thereby enhancing thermogenic efficiency in response to cold [16]. In addition, FGF21 works in concert with the sympathetic nervous system, accelerating the release of norepinephrine, which increases BAT sensitivity to cold stimuli. By boosting BAT’s metabolic activity and heat generation, these batokines enable the body to adapt quickly to cold environments while maintaining energy balance and body temperature, acting as crucial metabolic regulators during cold acclimation [17]. These factors target various cell types within BAT, promoting adipogenesis, angiogenesis, immune cell interactions, and synaptic growth [18]. Research has shown that BAT regulates energy homeostasis in response to overall metabolic status. When food is scarce, hunger signals from the hypothalamus activate gamma-aminobutyric acid neurons, which block sympathetic activation to reduce BAT thermogenesis and energy expenditure [19].

Beige adipose tissue

Beige adipocytes are induced thermogenic cells sporadically found in WAT. They contain multicompartmental lipid droplets and dense mitochondria expressing uncoupling protein-1, a phenomenon known as browning when brown adipocytes appear in WAT [20]. Beige adipocytes are unique thermogenic fat cells derived from white adipocytes chronically stimulated by cold, drugs, or exercise, although they have only a fifth of the heat-producing capacity of brown fat cells. Rich in mitochondria that generate heat to provide energy, beige adipocytes are a novel target for obesity prevention and treatment. They can also be derived from de novo differentiation of tissue-resident progenitor cells [21]. Activating BAT and inducing WAT browning accelerates glycolipid uptake and reduces the need for insulin secretion, offering a potential strategy to improve glycolipid metabolism and insulin resistance in obese and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients [22]. Adipocytes play a crucial role in weight control, energy balance, and the enhancement of glucose and lipid metabolism [23]. In response to external stimuli, such as cold exposure or beta3-adrenergic agonists, beige adipocytes in WAT increase glucose and lipid uptake, boosting energy expenditure and thermogenesis [24]. However, deleting Atg5 or Atg12 in adipocytes blocks the UCP-1 autophagy pathway, thereby preventing the conversion of beige to white adipocytes [25].

Role of adipokines in obesity

Leptin

Leptin, discovered in 1994, is primarily secreted by WAT [26]. It is a pleiotropic protein hormone that regulates food intake, energy expenditure, reproduction, hemostasis, angiogenesis, blood pressure, and immune responses. By activating the leptin receptor (LepR)–STAT3 signaling axis in specific hypothalamic neurons, leptin promotes satiety and energy homeostasis. In addition, leptin has direct biological roles in fetal growth, pro-inflammatory immune responses, angiogenesis, lipolysis, and tumor initiation and progression [27]. Binding of leptin to LepRb activates multiple signaling pathways, including JAK2/STAT3 (Janus kinase 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3), PI3K/Akt (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B), and ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase), which together regulate appetite, energy expenditure, fat metabolism, and insulin sensitivity [28].

This multifaceted role of leptin is crucial for maintaining systemic metabolic balance. However, in the context of obesity, leptin resistance—whereby elevated leptin levels fail to trigger expected metabolic responses—has profound effects on multiple organ systems. In muscles, leptin resistance may lead to reduced fatty acid oxidation and impaired muscle function, potentially contributing to muscle weakness in obesity [29]. In the brain, leptin resistance impairs hypothalamic function, which not only disrupts appetite regulation but may also increase the risk of neurodegenerative diseases [30]. In the liver, impaired leptin signaling exacerbates lipid accumulation, increasing the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [31]. In addition, in the heart, leptin resistance is linked to higher risks of hypertension and cardiovascular disease in obese individuals [32]. Despite leptin’s critical role in maintaining energy balance, these regulatory effects are significantly diminished in obese individuals due to leptin resistance. This leads to decreased energy expenditure and increased appetite, which exacerbate obesity-related complications.

Adiponectin

Adiponectin, secreted by BAT and typically low in obese individuals, enhances systemic energy homeostasis by stimulating fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle and inhibiting glucose production in the liver [33]. It also acts as a cellular anti-inflammatory agent through AdipoR1 and R2 signaling mechanisms [34]. Growing evidence indicates that obesity is not only accompanied by low circulating adiponectin concentrations, but also by adiponectin resistance at the level of the adiponectin receptors AdipoR1 and AdipoR2, as well as impaired AMPK signaling [35–38]. These pathways collectively contribute to adiponectin's ability to improve insulin sensitivity in muscle and liver, promote glucose uptake and utilization, lower blood glucose levels, alleviate fatty liver, and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Adiponectin resistance, particularly in obesity, exacerbates metabolic challenges across various organs. In muscle, decreased adiponectin activity hampers fatty acid oxidation, leading to increased intramuscular lipid accumulation and insulin resistance [39]. In the brain, reduced adiponectin signaling may disrupt hypothalamic regulation of appetite and energy balance, potentially contributing to cognitive impairments linked to obesity [40]. Moreover, reduced levels or resistance to adiponectin are associated with an increased risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). In the heart, adiponectin plays a role in reducing inflammation and maintaining vascular health, linking low adiponectin levels to a higher risk of cardiovascular complications, including endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis [41].

These findings underscore the crucial role of adiponectin in preserving metabolic equilibrium and mitigating inflammation. Adiponectin resistance and reduced levels in obesity contribute to negative impacts on multiple organ systems, worsening metabolic imbalances and raising the risk of cardiovascular issues. This highlights the potential of targeting adiponectin signaling pathways as a novel approach for obesity treatment.

Resistin

Resistin, known for its insulin resistance-promoting effects in mice, is primarily secreted by macrophages and other immune cells in humans, rather than adipocytes [42]. Its expression and secretion are influenced by insulin, glucose, and inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α and IL-6, with significant increases under inflammatory conditions. Resistin activates several downstream signaling pathways, including NF-κB, MAPK, and PI3K/Akt, which play roles in inflammatory responses, insulin resistance, and cell survival. In the context of obesity, resistin's pro-inflammatory effects in the brain may contribute to neuroinflammation, elevating the risk of cognitive decline and obesity-associated neurodegenerative diseases [43]. In the liver, resistin worsens hepatic insulin resistance and promotes lipid accumulation, heightening the risk of NAFLD [44]. By binding to its target receptors, such as TLR4 and CAP1, resistin induces vascular inflammation and encourages lipid accumulation, thereby accelerating atherosclerosis and increasing cardiovascular risk in individuals with obesity [45]. This multi-organ impact highlights resistin’s pivotal role in linking obesity to broader metabolic and inflammatory complications.

Crosstalk between skeletal muscle and adipose tissue

Generation and effects of myofactors

Exercise induces the secretion of myokines, facilitating crosstalk between adipose tissue and skeletal muscle through endocrine, paracrine, or autocrine pathways, potentially enhancing cardiovascular, metabolic, immune, and nervous system health. This crosstalk is especially critical in the context of obesity, where metabolic dysregulation and chronic inflammation can impact normal muscle and adipose tissue functions. Some myokines act within the muscle, such as muscle growth inhibitor, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), IL-6, and IL-7, which are involved in muscle hypertrophy and myogenesis. In addition, BDNF and IL-6 contribute to AMPK-mediated fat oxidation [46].

Stress-induced IL-6 is produced by brown adipocytes in a beta-3-adrenergic receptor-dependent manner, and its levels can increase up to 100-fold in circulation during physical activity [47]. In the context of obesity, IL-6 acts as an essential energy regulator in muscle tissue, affecting WAT and skeletal muscle metabolism and supporting metabolic homeostasis. This regulatory role is particularly important in mitigating metabolic imbalances associated with obesity, especially during exercise recovery. Furthermore, injecting IL-6 increases iWAT UCP1 mRNA levels in WT mice [48].

IL-15 is another myokine that may regulate adipose tissue and is associated with obesity. It is abundant in natural killer (NK) cells and modulates lipid accumulation by enhancing lipolysis or inhibiting lipid synthesis via the JAK and PKA pathways [49]. Irisin, a hormone-like myokine, is especially significant under obesity conditions, where it helps increase energy expenditure by stimulating WAT browning [50]. It is produced in large quantities by skeletal muscle during exercise, activating non-shivering thermogenesis and contributing to skeletal remodeling. In addition, irisin is also considered an adipokine [51, 52]. It can induce fat browning and improve mitochondrial homeostasis in human visceral adipose tissue. These effects may positively impact metabolic health in individuals with obesity [53, 54].

In contrast, follicle-stimulating stimulator (FST) promotes WAT browning by inducing irisin secretion in subcutaneous fat through the AMPK–PGC1α–irisin signaling pathway [55]. β-Aminoisobutyric acid (BAIBA) also increases in plasma concentration post-exercise, promoting BAT activation and WAT browning. BAIBA induces FFA oxidation in adipocyte mitochondria, enhances lipolysis, and increases the expression of brown adipocyte-specific genes in white adipocytes via a PPARα-mediated mechanism. It also induces a brown adipose-like phenotype in pluripotent stem cells and improves glucose homeostasis in mice [56]. These findings suggest that various myokines play a crucial role in regulating adipocyte browning, thermogenesis, and lipid metabolism, particularly within obesity-related contexts, where such regulation is essential for restoring metabolic balance and countering the negative health effects of obesity.

Effects of adipose tissue secreted factors on skeletal muscle

WAT can secrete several adipokines, including leptin and adiponectin. Leptin, secreted by AT, promotes skeletal muscle lipid metabolism, fatty acid utilization, and energy production while reducing skeletal muscle lipid accumulation. Studies have shown that leptin is the sole mediator of AT in maintaining muscle mass and strength [57]. leptin not only increases muscle mass by inducing myocyte proliferation factors and negative regulators that inhibit muscle growth, such as the atrophy markers MAFbx and MuRF1, per se [58]. In addition, leptin also enhances irisin-induced myogenesis, supporting muscle growth and repair [59].

Leptin further enhances the postprandial clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein lipids, partly due to the increased activity of skeletal muscle lipoprotein lipase (SMLPL). Adiponectin, secreted by AT, stimulates fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle and inhibits glucose production in the liver, thereby improving systemic energy homeostasis. Binding of adiponectin to its receptors, AdipoR1 and R2, activates AMPK in skeletal muscle and stimulates fatty acid oxidation through the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) and PPARα ligand activity, significantly reducing ceramide levels in exercise-oxidized muscle [60]. Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), a metabolic hormone released by BAT, has pleiotropic effects on glucose and lipid homeostasis as well as insulin sensitivity. FGF21 induces an increase in BAT and mitochondrial cristae in skeletal muscle, enhancing thermogenesis and promoting myofiber-type transformation by inhibiting the TGF-β1 signaling axis and activating the p38 MAPK pathway [61]. In addition, adipocyte-derived exosomes can enter skeletal muscle cells, where exosomal miR-27a induces insulin signaling by inhibiting PPARγ-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle [62]. Collectively, these studies suggest that the crosstalk between adipose tissue and skeletal muscle is essential for maintaining human homeostasis.

Crosstalk between brain and adipose tissue

Mutual regulation of the central nervous system and adipose tissue

Crosstalk between the central nervous system and adipose tissue is crucial for maintaining energy homeostasis, body temperature, reducing cancer risk, and extending lifespan. The nervous system regulates heat loss, cutaneous vasoconstriction, and BAT thermogenesis [63]. The thermogenic effects of BAT can also be activated by the hypothalamic sympathetic nervous system. The hypothalamus maintains body temperature by driving sympathetic activation, which releases norepinephrine from nerve endings in BAT, triggering an intracellular lipolytic cascade that releases fatty acids to fuel the mitochondrial electron transport chain [64]. In addition, thyroid hormones play a significant role in energy homeostasis and cold adaptation by inducing high intracellular expression of type II deiodinase. This enhances thyroid hormone signaling, including the expression of Ppargc1a and Ucp1 genes, and is central to BAT production and development in the mouse embryo [65]. Studies have shown that thyroid hormone T3 induces high mitochondrial respiration and UCP1 expression, increasing short- and long-chain acylcarnitines in BAT, which aligns with enhanced β-oxidation. T3 also regulates the thermogenic program of BAT via AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMH). Stimulating BAT activity with thyroid hormone or its analogs may thus offer a potential therapeutic strategy for obesity and metabolic diseases [66]. M2-like macrophages are important for adipose tissue homeostasis, using the macrophage–sympathetic neuron–adipocyte signaling axis to regulate long-term cold adaptation. Targeting intra-adipose macrophage–sympathetic neuron crosstalk can ameliorate malignant diseases in cancer patients. One mechanism is that interleukin-4 receptor deficiency prevents selective macrophage activation, reduces sympathetic neuronal activity, and inhibits WAT browning. Another mechanism involves reduced catecholamine synthesis in dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH)-deficient mice, which prevents cancer-induced WAT browning and lipoatrophy [67]. Furthermore, research has shown that DMH-specific Prkg1 knockdown in the dorsomedial hypothalamus, along with chemogenetic activation of PPP1R17 neurons in the DMH, significantly ameliorates age-related WAT dysfunction, increases physical activity, and prolongs lifespan. This finding highlights the crucial role of hypothalamus–WAT communication in controlling mammalian aging and longevity [68].

Estradiol (E2) may regulate energy homeostasis by reducing hypothalamic ceramide levels and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Leptin, secreted by adipocytes, acts as an afferent signal in a negative feedback loop, primarily targeting hypothalamic (POMC) neurons, but also signaling in the hindbrain to inhibit food intake and increase energy expenditure by facilitating thermogenesis in BAT. In the hypothalamus, leptin enhances sympathetic activity in BAT and increases UCP-1 expression [69]. Leptin’s influence on innervation is mediated by spiny mouse-related peptides and presynaptic melanocortin neurons in the arcuate nucleus. In both populations, neurons lacking the leptin receptor gene can act through neurons expressing brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the paraventricular nucleus (BDNFPVH), reducing fat innervation. The absence of BDNFPVH also weakens leptin’s effect on innervation. These findings suggest that leptin signaling regulates the plasticity of sympathetic neural structures in adipose tissue via top-down neural pathways, which are crucial for maintaining energy homeostasis [70]. Glucocorticoids increase isoproterenol-stimulated respiration and UCP-1 expression in human primary brown adipocytes, but have the opposite effect in rodents [71]. This species-specific modulation of BAT function by glucocorticoids may have significant implications for developing novel therapies that activate BAT to improve metabolic health. Leptin, an adipocyte-derived hormone, crosses the blood–brain barrier and mobilizes regulatory circuits through elongation cells expressing functional leptin receptors (LepRb). These cells respond to leptin by triggering Ca2+ waves and target-protein phosphorylation. The transcellular transport of leptin requires the sequential activation of the LepR complex by leptin and EGF. Selective deletion of LepR in elongating cells blocks leptin's entry into the brain, leading to increased food intake, adipogenesis, and potential glucose intolerance by reducing insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells, possibly by altering sympathetic tone [72]. Thus, tanycytic LepRb transport of leptin could play a crucial role in the pathophysiology of diabetes and obesity, offering therapeutic implications.

Effects of obesity induced by a high-fat diet on nerve fibres

High-fat and high-sugar diets, known as obesogenic diets (OD), are associated with low-grade chronic inflammation and neurodevelopmental deficits. Rodent studies have consistently shown that chronic consumption of high-fat diets increases levels of neuroinflammatory markers. Besides memory deficits, chronic intake of OD and Western diets leads to severe metabolic and neurobiological disruptions, including impaired memory control [73]. For example, male rat offspring of obese mothers exhibit significantly increased neuroinflammation and microglial activation when fed a Western diet, as well as an elevated presence of microglial activation markers in the hippocampus of high-fat diet pups [74]. Moreover, a high-fat diet (HFD) increases the risk of obesity and neurocognitive decline. HFD-induced hippocampal damage is further worsened by Trim69 deficiency, resulting in reduced nerve fiber survival and increased apoptotic cell death [75]. Concurrently, a high-fat diet induces neurological deficits, oxidative stress, and reduces hippocampal neurogenesis, thereby negatively impacting cognitive function and overall brain health. In addition, maternal high-fat diets can adversely affect offspring, impairing hippocampal development, reducing neural progenitor cell proliferation, affecting nerve fiber differentiation, dendritic spine density, and diminishing neurogenic competence [76]. Maternal consumption of an HFD during pregnancy stimulates the production of hypothalamic orexigenic peptide neurons in offspring, while HFD ingestion in adult animals results in systemic low-grade inflammation, elevating neuroimmune factors that may hinder neurogenesis and neuronal migration [77]. Chronic feeding of an HFD not only depletes hypothalamic neural stem cells (htNSCs) through IKKβ/NF-κB activation but also contributes to neurogenic damage [78].

Crosstalk between the heart and adipose tissue

Adipokines and BAT-secreted cytokines regulate heart function

Excess visceral adipose tissue significantly increases the risk of fat accumulation in normal lean tissues, leading to ectopic fat deposits in organs, such as the liver, heart, and skeletal muscle. Obesity is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, with strong correlations to coronary heart disease, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation. BAT represents one of the main sources of lipokines, a series of bioactive lipids that contribute to the communication between adipose tissue and other metabolic tissues, including the heart [79]. In this regard, 12,13-di-HOME is a lipokine (not adipokine) that increases cardiac hemodynamics via direct effects on cardiomyocytes [80].Adiponectin, a complex adipokine, is associated with an increased risk of heart failure, atrial fibrillation, aortic stenosis, and myocardial infarction. The adiponectin Receptor 1 of GRK2 (G Protein-coupled Receptor Kinase 2) maintains the S205A type, and administering adiponectin to failing hearts can reverse remodeling and improve cardiac function post-myocardial infarction [81]. In addition, adiponectin modulates the left stellate ganglion (LSG) in a canine myocardial infarction model, exerting cardioprotective effects via the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) [82]. In the absence of adiponectin kinase activation is impaired. Kinases are vital for tissue preservation, including components of the RISK pathway, such as PI3K–Akt and p44/42, and inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), although they may exacerbate ischemia/reperfusion (I/R)-induced cardiac injury [83]. Studies in mice have shown that adiponectin prevents LPS-induced apoptosis during sepsis by modulating the Cx43 and PI3K/AKT pathways, both in vitro and in vivo [84].

Resistin, known for its role in inducing insulin resistance, can induce cardiac fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation through the JAK/STAT3 and JNK/c-Jun signaling pathways. It also protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury by activating the AKT pathway [85]. Reduced circulating resistin protein (Retn) levels decrease myocardial fibrosis and apoptosis, thereby improving heart failure outcomes. Exogenous resistin induces dose-dependent positive inotropic and cardiogenic effects in human atrial trabeculae, but does not promote arrhythmias [86]. The role of leptin and its receptors in heart disease is complex, especially in rodent models. Leptin can counteract inflammation in the heart and adipose tissue by regulating gene expression [87]. Hyperleptinemia is positively associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and the cardioprotective effects of leptin require the activation of brain melanocortin-4 receptors [88]. In addition, elevated leptin levels are linked to increased body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, and myocardial wall thickness. While the leptin–LEPR pathway is essential for maintaining normal cardiac function, overactivation of this pathway in the presence of pathological injury may impair cardiac function [89].

FGF 21, a unique member of the fibroblast growth factor family, affects cell metabolism rather than proliferation and has profound beneficial effects on obesity and type 2 diabetes. It inhibits cardiac hypertrophy and protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury [90]. While FGF 21 is primarily secreted by the liver under normal conditions, it can also be produced by other tissues, including BAT and the heart itself, under certain pathophysiological conditions. Ruan et al. demonstrated that in rodents, BAT can secrete FGF 21 into the circulation under hypertensive conditions, directly targeting the heart to attenuate cardiac remodeling [91]. The mineralocorticoid receptor (MR)/FGF 21 axis plays a key role in liver–heart protection against myocardial infarction. Both hepatocellular IL-6 receptor deficiency and Stat3 deficiency exacerbate cardiac injury by modulating this axis. In addition, cardiomyocyte-derived FGF 21 may provide a feedback signal to adipose tissue. Clinically, serum concentrations of FGF 21 are significantly elevated after myocardial infarction, as observed in both patients and mouse models [92]. FGF 21 promotes BAT activation and WAT browning, enhances the selective uptake of fatty acids from triglyceride-rich lipoproteins into BAT and browned WAT, and accelerates the hepatic clearance of cholesterol-rich remnants [93]. Together, these findings suggest that FGF 21 forms a bidirectional communication axis between adipose tissue and the heart.

The adenosine A2A receptor is a G protein-coupled receptor that plays a crucial role in the cardiovascular system. It is also the most abundant adenosine receptor in human and mouse BAT. Knockdown of the A2A receptor results in a BAT-dependent reduction in thermogenesis and prevents diet-induced obesity [94, 95]. In BAT, specific knockdown of FGF 21 reduces the effects of A2A receptor agonists. Conversely, activation of the A2A receptor promotes FGF 21 release, thereby improving cardiac function [96]. Stress-induced IL-6, produced by brown adipocytes in a β3-adrenergic receptor-dependent manner, can increase cardiac matrix oxidation, protect the heart from hypertrophy and oxidative stress, but may also contribute to adverse cardiac remodeling and myocardial infarction [97]. In addition, BAT can regulate energy metabolism and its activation through the release of adipokines, such as 12,13-diHOME [98]. Acute administration of 12,13-diHOME in mice increases skeletal muscle fatty acid uptake and oxidation [99]. Furthermore, 12,13-diHOME may counteract the negative effects of a high-fat diet on cardiac function and remodeling. Acute injections of 12,13-diHOME have been shown to directly improve cardiac hemodynamics by acting on cardiomyocytes. The A2A receptor is also expressed in lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs), where its mediated activation of VEGF-independent VEGFR2 signaling plays a role in dermal lymphangiogenesis and sodium homeostasis. This mechanism may serve as a potential target for treating hypertension caused by excessive dietary sodium intake [100].

Factors produced by the heart regulate BAT activity

The heart produces natriuretic peptides, including atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and ventricular natriuretic peptide (BNP), which can act as heart hormones. Both ANP and BNP preferentially bind to natriuretic peptide receptor-A (NPR-A or guanylyl cyslase-A) and exert similar effects through increases in intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) within target tissues. Expression and secretion of ANP and BNP are stimulated by various factors and are regulated via multiple signaling pathways [101]. Natriuretic peptides is involved in pathophysiological processes, such as heart failure, obesity and systemic hypertension. The loss of homeostatic effects of natriuretic peptides is exacerbated by the interference of obesity and heart failure with adiponectin signaling. This complex neurohormonal interaction leads to plasma volume expansion, adverse ventricular remodeling and cardiac fibrosis [102]. At low concentrations, the addition of ANP and beta-adrenergic receptor agonists increases brown fat and mitochondrial marker expression in a p38 MAPK-dependent manner. Cardiac natriuretic peptides (NPs) and β-AR agonists are equally effective in stimulating lipolysis in human adipocytes. In human adipocytes, atrial NP (ANP) and ventricular NP (BNP) activate the expression of PPARγ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) and UCP1, induce mitochondrial biogenesis and increase uncoupled and total respiration. When infused into mice, BNP significantly increases the expression of UCP-1 and PGC-1a in white and brown adipose tissue and increases respiration and energy expenditure [103].

Crosstalk between liver and adipose tissue

The effect of adipose tissue and its secreted factors on liver function

Leptin secreted by AT regulates diet and energy metabolism. It prevents lipid overaccumulation in the liver and WAT during obesity by restoring the coordinated action of aquaporin-9 (AQP9), which helps reduce hepatocyte damage and death [104]. In addition, FGF21 reduces body fat, improves glucose tolerance, and significantly decreases hepatic steatosis. This effect is associated with the upregulation of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation and increased hepatic VLDL triglyceride secretion. Neuromodulin 4 (Nrg4), a novel factor highly expressed in brown fat, attenuates hepatic lipogenic signaling, reducing insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in patients with obesity. Mechanistically, Nrg4 activates ErbB3/ErbB4 signaling in hepatocytes and regulates LXR/SREBP1c-mediated adipogenesis in a cell-autonomous manner [105]. Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) induces weight loss and increases insulin sensitivity in obese rodents. When fatty acid synthesis in the liver is inhibited, it increases fatty acid synthesis in WAT. Glycoprotein non-metastatic melanoma protein B (Gpnmb) acts as a hepatic–WAT crosstalk factor involved in adipogenesis. It stimulates adipogenesis in WAT and exacerbates diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Therefore, inhibiting Gpnmb may provide a therapeutic strategy for obesity and diabetes [106]. WAT and the liver work together to regulate systemic metabolism. If adipose tissue cannot store and mobilize lipids, it results in a systemic cascade of lipid overload, particularly in the liver. FGF21 functions as a bidirectional communication axis between BAT and the liver. Hepatic induction of FGF21 during the fetal-to-neonatal transition directly activates brown fat thermogenesis [107]. In addition, AT can produce circulating exosomal miRNAs. Transplanting WAT and BAT into ADicerKO mice restores hepatic FGF21 mRNA and circulating FGF21 levels, which are linked to circulating exosomal miRNAs [108]. Furthermore, replacing isoleucine with methionine at position 148 of the PNPLA3 protein leads to loss of function, preventing the remodeling of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acid esters. This promotes their retention in the liver and is an important factor in the development of steatohepatitis [109].

Influence of the liver on adipose tissue

Hepatocytes are the main metabolic center of the body, and WNT2 secreted from sinusoidal endothelial cells controls cholesterol uptake and bile acid binding in hepatocytes via the receptor frizzled class receptor 5 (FZD5) [110]. The hypothalamic G protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5) is a key mediator of the neural mechanisms through which bile acids (BAs) improve metabolism and exhibit anti-obesity effects. It is also a potential pharmacological target for treating obesity and related metabolic disorders. In mice, bile acid administration increases energy expenditure in BAT [111]. Hepatocytes express the sodium–taurine bile acid cotransporter protein (NTCP), a sodium-dependent bile acid transporter that facilitates bile acid uptake from blood to liver cells [112]. NTCP deficiency reduces hepatic clearance of plasma bile acids, leading to increased plasma bile acid levels, reduced diet-induced obesity, attenuated hepatic steatosis, and lower plasma cholesterol levels. Panax ginseng delta saponin Ft1 (Ft1) acts as a TGR5 agonist, activating TGR5 in adipose tissue and alleviating high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance [112]. Notably, NTCP and TGR5 double knockout mice show the same level of protection from diet-induced obesity as NTCP single knockout mice, suggesting that NTCP deficiency is linked to increased uncoupled respiration in BAT, resulting in elevated energy expenditure [113]. Bile acids also promote TGR5 signaling, leading to mitochondrial division and beige remodeling in WAT [114]. In addition, the human hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis controls the bile acid cycle in the enterohepatic system via the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), influencing dietary fat absorption and BAT activation1 [115].Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), synthesized by the liver, plays a role in increasing lipolysis and BAT activity while reducing BAT mass [116]. This crosstalk between the liver and adipose tissue is essential for maintaining liver function and whole-body energy homeostasis.

Conclusions

The interaction between adipose tissue and organs such as muscle, brain, liver, and heart is crucial for maintaining energy balance and metabolism. Different adipose tissues, including white, brown, and beige adipocytes, have unique functions that influence various physiological and pathological processes. Adipokines, such as leptin, adiponectin, and resistin, significantly impact metabolic health and the development of chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and mental disorders. Obesity disrupts the communication between adipose tissue and these organs, worsening metabolic abnormalities.

Recent advancements have led to targeted therapies that address specific metabolic pathways involved in obesity. For instance, FGF21 analogs are being developed to improve insulin sensitivity, reduce liver fat accumulation, and enhance lipid oxidation, showing promise particularly in patients with NAFLD associated with obesity [117]. In addition, GDF15 mimetics have shown potential in controlling appetite and promoting weight loss by influencing central nervous system pathways linked to hunger and satiety [118]. For liver-related metabolic dysfunction, Nrg4-based therapies are under investigation for their role in reducing hepatic lipogenesis and combating obesity-induced liver complications through hepatocyte signaling modulation [119].

Moreover, studies have highlighted metabolic differences between human and rodent brown adipocytes, underscoring the importance of tailoring research and treatment approaches. For example, while human brown adipose tissue thermogenesis is mediated by β2-adrenergic receptors, β3-adrenergic receptors play a more prominent role in rodents [120]. This distinction reinforces the need for species-specific research to develop effective therapeutic interventions.

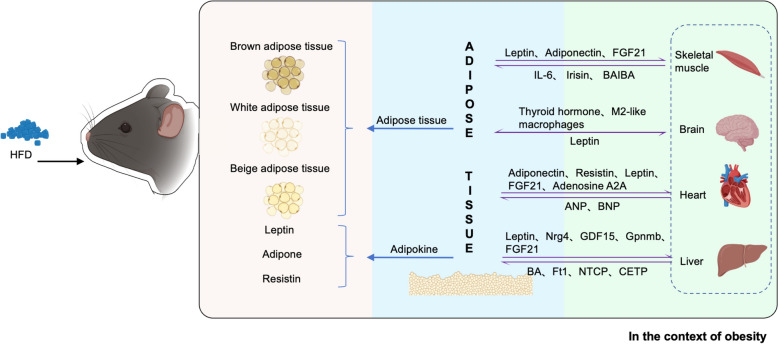

The complex bidirectional communication between adipose tissue and other organs involves various signaling pathways, often disrupted in obesity, leading to metabolic dysregulation. This review identifies potential therapeutic targets, including the regulation of adipokines and adrenergic receptors. Future research should further explore these cellular and molecular mechanisms, focusing on therapies that harness the metabolic roles of adipokines, adrenergic receptors, and thermogenic regulators to develop effective strategies for combating obesity and promoting metabolic health (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Composition of adipose tissue and its secretory factors. Communication between adipose tissue and other organs

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants from the Central Government Guides Local Science and Technology Development Funds (YDZX2022091).

Abbreviations

- WAT

White adipose tissue

- BAT

Brown adipose tissue

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- AT

Adipose tissue

- BAIBA/BA

β-Aminoisobutyric acid

- VEGFA

Vascular endothelial growth factor A

- SMLPL

Skeletal muscle lipoprotein lipase

- HFD

High-fat diet

- ANP

Atrial natriuretic peptide

- BNP

Ventricular natriuretic peptide

- NTCP

Sodium–taurine bile acid cotransporter protein

- CETP

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein

Author contributions

CZ and JL conceptualised the study; ZJ, ZW, HP and JZ were involved in the literature review; ZJ, CZ, and QL prepared Fig. 1. All authors wrote the final and first drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zixuan Jia and Ziqi Wang have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Caixia Zhou, Email: zcq_zcx@126.com.

Jun Liu, Email: liujun1@sdpei.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Gutiérrez-Cuevas J, Santos A, Armendariz-Borunda J. Pathophysiological molecular mechanisms of obesity: a link between MAFLD and NASH with cardiovascular diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutiérrez-Cuevas J, Sandoval-Rodriguez A, Meza-Rios A, et al. Molecular mechanisms of obesity-linked cardiac dysfunction: an up-date on current knowledge. Cells. 2021;10(3):629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaszkiewicz M, Willows JW, Dubois AL, et al. Neuropathy and neural plasticity in the subcutaneous white adipose depot. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9): e0221766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi Z, Wong J, Brooks VL. Obesity: sex and sympathetics. Biol Sex Differ. 2020;11(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardaci TD, VanderVeen BN, Bullard BM, et al. Obesity worsens mitochondrial quality control and does not protect against skeletal muscle wasting in murine cancer cachexia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2024;15(1):124–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sui SX, Pasco JA. Obesity and brain function: the brain-body crosstalk. Medicina. 2020;56(10):499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Q, Wang O, Ji B, et al. Alcohol, white adipose tissue, and brown adipose tissue: mechanistic links to lipogenesis and lipolysis. Nutrients. 2023. 10.3390/nu15132953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mouton AJ, Li X, Hall ME, et al. Obesity, Hypertension, and cardiac dysfunction: novel roles of immunometabolism in macrophage activation and inflammation. Circ Res. 2020;126(6):789–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reyes-Farias M, Fos-Domenech J, Serra D, et al. White adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity and aging. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;192:114723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qian X, Meng X, Zhang S, et al. Neuroimmune regulation of white adipose tissues. FEBS J. 2022;289(24):7830–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang QA, Tao C, Gupta RK, et al. Tracking adipogenesis during white adipose tissue development, expansion and regeneration. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1338–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emont MP, Rosen ED. Exploring the heterogeneity of white adipose tissue in mouse and man. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2023;80:102045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinonen S, Jokinen R, Rissanen A, et al. White adipose tissue mitochondrial metabolism in health and in obesity. Obes Rev. 2020;21(2): e12958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang J, Zhang H, Parhat K, et al. Molecular imaging of brown adipose tissue mass. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(17):9436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheele C, Wolfrum C. Brown adipose crosstalk in tissue plasticity and human metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(1):53–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diallo K, Dussault S, Noll C, et al. 14-3-3ζ mediates an alternative, non-thermogenic mechanism in male mice to reduce heat loss and improve cold tolerance. Mol Metabol. 2020;41:101052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shamsi F, Xue R, Huang TL, et al. FGF6 and FGF9 regulate UCP1 expression independent of brown adipogenesis. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim S, Honek J, Xue Y, et al. Cold-induced activation of brown adipose tissue and adipose angiogenesis in mice. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(3):606–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henningsen JB, Scheele C. Brown adipose tissue: a metabolic regulator in a hypothalamic cross talk? Annu Rev Physiol. 2021;83(1):279–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suárez-Zamorano N, Fabbiano S, Chevalier C, et al. Microbiota depletion promotes browning of white adipose tissue and reduces obesity. Nat Med. 2015;21(12):1497–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Francis CE, Allee L, Nguyen H, et al. Endocrine disrupting chemicals: friend or foe to brown and beige adipose tissue? Toxicology. 2021;463:152972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lizcano F. The beige adipocyte as a therapy for metabolic diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(20):5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harms M, Seale P. Brown and beige fat: development, function and therapeutic potential. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1252–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitehead A, Krause FN, Moran A, et al. Brown and beige adipose tissue regulate systemic metabolism through a metabolite interorgan signaling axis. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikeda K, Maretich P, Kajimura S. The common and distinct features of brown and beige adipocytes. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29(3):191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perakakis N, Farr OM, Mantzoros CS. Leptin in leanness and obesity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(6):745–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obradovic M, Sudar-Milovanovic E, Soskic S, et al. Leptin and obesity: role and clinical implication. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12:585887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang S, Liu Y, Chen J, et al. Effects of multi-organ crosstalk on the physiology and pathology of adipose tissue. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1198984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins KH, Gui C, Ely EV, et al. Leptin mediates the regulation of muscle mass and strength by adipose tissue. J Physiol. 2022;600(16):3795–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zou X, Zhong L, Zhu C, et al. Role of leptin in mood disorder and neurodegenerative disease. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boutari C, Mantzoros CS. Adiponectin and leptin in the diagnosis and therapy of NAFLD. Metabolism. 2020;103:154028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang H, Guo W, Li J, et al. Leptin concentration and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3): e0166360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kita S, Maeda N, Shimomura I. Interorgan communication by exosomes, adipose tissue, and adiponectin in metabolic syndrome. J Clin Investig. 2019;129(10):4041–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodríguez A, Becerril S, Méndez-Giménez L, et al. Leptin administration activates irisin-induced myogenesis via nitric oxide-dependent mechanisms, but reduces its effect on subcutaneous fat browning in mice. Int J Obes. 2015;39(3):397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao J, Fan J, Meng Z, et al. Nicotine aggravates vascular adiponectin resistance via ubiquitin-mediated adiponectin receptor degradation in diabetic Apolipoprotein E knockout mouse. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(6):508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mullen KL, Smith AC, Junkin KA, et al. Globular adiponectin resistance develops independently of impaired insulin-stimulated glucose transport in soleus muscle from high-fat-fed rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;293(1):E83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen MB, McAinch AJ, Macaulay SL, et al. Impaired activation of AMP-kinase and fatty acid oxidation by globular adiponectin in cultured human skeletal muscle of obese type 2 diabetics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(6):3665–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodríguez A, Catalán V, Becerril S, et al. Impaired adiponectin-AMPK signalling in insulin-sensitive tissues of hypertensive rats. Life Sci. 2008;83(15–16):540–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abou-Samra M, Selvais CM, Dubuisson N, et al. Adiponectin and Its mimics on skeletal muscle: insulin sensitizers, fat burners, exercise mimickers, muscling pills… or everything together? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(7):2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizzo MR, Fasano R, Paolisso G. Adiponectin and cognitive decline. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(6):2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Berendoncks AM, Garnier A, Ventura-Clapier R, et al. Adiponectin: key role and potential target to reverse energy wasting in chronic heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2013;18(5):557–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi Y, Zhu N, Qiu Y, et al. Resistin-like molecules: a marker, mediator and therapeutic target for multiple diseases. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parimisetty A, Dorsemans AC, Awada R, et al. Secret talk between adipose tissue and central nervous system via secreted factors—an emerging frontier in the neurodegenerative research. J Neuroinflamm. 2016;13(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wen F, Shi Z, Liu X, et al. Acute elevated resistin exacerbates mitochondrial damage and aggravates liver steatosis through AMPK/PGC-1α signaling pathway in male NAFLD mice. Horm Metab Res. 2021;53(02):132–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou L, Li JY, He PP, et al. Resistin: potential biomarker and therapeutic target in atherosclerosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;512:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(8):457–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qing H, Desrouleaux R, Israni-Winger K, et al. Origin and function of stress-induced IL-6 in murine models. Cell. 2020;182(2):372-387.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knudsen JG, Murholm M, Carey AL, et al. Role of IL-6 in exercise training- and cold-induced UCP1 expression in subcutaneous white adipose tissue. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1): e84910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ajuwon KM, Spurlock ME. Direct regulation of lipolysis by interleukin-15 in primary pig adipocytes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287(3):R608–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perakakis N, Triantafyllou GA, Fernández-Real JM, et al. Physiology and role of irisin in glucose homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(6):324–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roca-Rivada A, Castelao C, Senin LL, et al. FNDC5/irisin is not only a myokine but also an adipokine. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4): e60563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moreno-Navarrete JM, Ortega F, Serrano M, et al. Irisin is expressed and produced by human muscle and adipose tissue in association with obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(4):E769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neira G, Hernández-Pardos AW, Becerril S, et al. Differential mitochondrial adaptation and FNDC5 production in brown and white adipose tissue in response to cold and obesity. Obesity. 2024;32(11):2120–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frühbeck G, Fernández-Quintana B, Paniagua M, et al. FNDC4, a novel adipokine that reduces lipogenesis and promotes fat browning in human visceral adipocytes. Metabolism. 2020;108:154261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li H, Zhang C, Liu J, et al. Intraperitoneal administration of follistatin promotes adipocyte browning in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7): e0220310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roberts LD, Boström P, O’Sullivan JF, et al. β-aminoisobutyric Acid induces browning of white fat and hepatic β-oxidation and is inversely correlated with cardiometabolic risk factors. Cell Metab. 2014;19(1):96–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stern JH, Rutkowski JM, Scherer PE. Adiponectin, leptin, and fatty acids in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis through adipose tissue crosstalk. Cell Metab. 2016;23(5):770–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nwadozi E, Ng A, Strömberg A, et al. Leptin is a physiological regulator of skeletal muscle angiogenesis and is locally produced by PDGFRα and PDGFRβ expressing perivascular cells. Angiogenesis. 2019;22(1):103–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reza MM, Subramaniyam N, Sim CM, et al. Irisin is a pro-myogenic factor that induces skeletal muscle hypertrophy and rescues denervation-induced atrophy. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rutkowski JM, Halberg N, Wang QA, et al. Differential transendothelial transport of adiponectin complexes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Luo X, Zhang H, Cao X, et al. Endurance exercise-induced Fgf21 promotes skeletal muscle fiber conversion through TGF-β1 and p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(14):11401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu Y, Du H, Wei S, et al. Adipocyte-derived exosomal MiR-27a induces insulin resistance in skeletal muscle through repression of PPARγ. Theranostics. 2018;8(8):2171–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morrison SF, Nakamura K. Central mechanisms for thermoregulation. Annu Rev Physiol. 2019;81(1):285–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blondin DP, Frisch F, Phoenix S, et al. Inhibition of intracellular triglyceride lipolysis suppresses cold-induced brown adipose tissue metabolism and increases shivering in humans. Cell Metab. 2017;25(2):438–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bianco AC, McAninch EA. The role of thyroid hormone and brown adipose tissue in energy homoeostasis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1(3):250–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yau WW, Singh BK, Lesmana R, et al. Thyroid hormone (T 3) stimulates brown adipose tissue activation via mitochondrial biogenesis and MTOR-mediated mitophagy. Autophagy. 2019;15(1):131–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xie H, Heier C, Meng X, et al. An immune-sympathetic neuron communication axis guides adipose tissue browning in cancer-associated cachexia. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119(9): e2112840119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tokizane K, Brace CS, Imai S. DMHPpp1r17 neurons regulate aging and lifespan in mice through hypothalamic-adipose inter-tissue communication. Cell Metabol. 2024;36(2):377-392.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Friedman JM. Leptin and the endocrine control of energy balance. Nat Metab. 2019;1(8):754–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang P, Loh KH, Wu M, et al. A leptin–BDNF pathway regulating sympathetic innervation of adipose tissue. Nature. 2020;583(7818):839–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ramage LE, Akyol M, Fletcher AM, et al. Glucocorticoids acutely increase brown adipose tissue activity in humans, revealing species-specific differences in UCP-1 regulation. Cell Metab. 2016;24(1):130–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duquenne M, Folgueira C, Bourouh C, et al. Leptin brain entry via a tanycytic LepR–EGFR shuttle controls lipid metabolism and pancreas function. Nat Metab. 2021;3(8):1071–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tsan L, Décarie-Spain L, Noble EE, et al. Western diet consumption during development: setting the stage for neurocognitive dysfunction. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:632312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bilbo SD, Tsang V. Enduring consequences of maternal obesity for brain inflammation and behavior of offspring. FASEB J. 2010;24(6):2104–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li LJ, Zheng JC, Kang R, et al. Targeting Trim69 alleviates high fat diet (HFD)-induced hippocampal injury in mice by inhibiting apoptosis and inflammation through ASK1 inactivation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;515(4):658–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mendes-da-Silva C, Lemes SF, Baliani TDS, et al. Increased expression of Hes5 protein in Notch signaling pathway in the hippocampus of mice offspring of dams fed a high-fat diet during pregnancy and suckling. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2015;40(1):35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Poon K, Abramova D, Ho HT, et al. Prenatal fat-rich diet exposure alters responses of embryonic neurons to the chemokine, CCL2, in the hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 2016;324:407–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li J, Tang Y, Cai D. IKKβ/NF-κB disrupts adult hypothalamic neural stem cells to mediate a neurodegenerative mechanism of dietary obesity and pre-diabetes. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(10):999–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rodríguez A, Becerril S, Hernández-Pardos AW, et al. Adipose tissue depot differences in adipokines and effects on skeletal and cardiac muscle. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2020;52:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pinckard KM, Shettigar VK, Wright KR, et al. A novel endocrine role for the BAT-released lipokine 12,13-diHOME to mediate cardiac function. Circulation. 2021;143(2):145–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhu D, Zhang Z, Zhao J, et al. Targeting adiponectin receptor 1 phosphorylation against ischemic heart failure. Circ Res. 2022;131(2):e34–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhou Z, Liu C, Xu S, et al. Metabolism regulator adiponectin prevents cardiac remodeling and ventricular arrhythmias via sympathetic modulation in a myocardial infarction model. Basic Res Cardiol. 2022;117(1):34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smith CCT, Yellon DM. Adipocytokines, cardiovascular pathophysiology and myocardial protection. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;129(2):206–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu L, Yan M, Yang R, et al. Adiponectin attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis by regulating the Cx43/PI3K/AKT pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:644225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Singh R, Kaundal RK, Zhao B, et al. Resistin induces cardiac fibroblast-myofibroblast differentiation through JAK/STAT3 and JNK/c-Jun signaling. Pharmacol Res. 2021;167:105414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Aitken-Buck HM, Babakr AA, Fomison-Nurse IC, et al. Inotropic and lusitropic, but not arrhythmogenic, effects of adipocytokine resistin on human atrial myocardium. Am J Physiol-Endocrinol Metabol. 2020;319(3):E540–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Abd Alkhaleq H, Kornowski R, Waldman M, et al. Leptin modulates gene expression in the heart, cardiomyocytes and the adipose tissue thus mitigating LPS-induced damage. Exp Cell Res. 2021;404(2):112647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gava FN, Da Silva AA, Dai X, et al. Restoration of cardiac function after myocardial infarction by long-term activation of the CNS leptin-melanocortin system. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2021;6(1):55–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sweeney G. Cardiovascular effects of leptin. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7(1):22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Scarpellini E, Arts J, Karamanolis G, et al. International consensus on the diagnosis and management of dumping syndrome. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(8):448–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ruan C, Gao P. GW29-e1353 A2A receptor activation attenuates hypertensive cardiac remodeling via promoting brown adipose tissue-derived FGF21. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(16):C41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sunaga H, Koitabashi N, Iso T, et al. Activation of cardiac AMPK-FGF21 feed-forward loop in acute myocardial infarction: role of adrenergic overdrive and lipolysis byproducts. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):11841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu C, Schönke M, Zhou E, et al. Pharmacological treatment with FGF21 strongly improves plasma cholesterol metabolism to reduce atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2022;118(2):489–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gnad T, Scheibler S, Von Kügelgen I, et al. Adenosine activates brown adipose tissue and recruits beige adipocytes via A2A receptors. Nature. 2014;516(7531):395–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cully M. Adenosine protects from diet-induced obesity. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(12):886–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ruan CC, Kong LR, Chen XH, et al. A2A receptor activation attenuates hypertensive cardiac remodeling via promoting brown adipose tissue-derived FGF21. Cell Metab. 2018;28(3):476-489.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Alter C, Henseler AS, Owenier C, et al. IL-6 in the infarcted heart is preferentially formed by fibroblasts and modulated by purinergic signaling. J Clin Investig. 2023;133(11): e163799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vasan SK, Noordam R, Gowri MS, et al. The proposed systemic thermogenic metabolites succinate and 12,13-diHOME are inversely associated with adiposity and related metabolic traits: evidence from a large human cross-sectional study. Diabetologia. 2019;62(11):2079–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stanford KI, Lynes MD, Takahashi H, et al. 12,13-diHOME: an exercise-induced lipokine that increases skeletal muscle fatty acid uptake. Cell Metab. 2018;27(5):1111-1120.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhuang T, Lei Y, Chang JJ, et al. A2AR-mediated lymphangiogenesis via VEGFR2 signaling prevents salt-sensitive hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(29):2730–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nakagawa Y, Nishikimi T, Kuwahara K. Atrial and brain natriuretic peptides: hormones secreted from the heart. Peptides. 2019;111:18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Packer M. Leptin-aldosterone-neprilysin axis: identification of its distinctive role in the pathogenesis of the three phenotypes of heart failure in people with obesity. Circulation. 2018;137(15):1614–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bordicchia M, Liu D, Amri EZ, et al. Cardiac natriuretic peptides act via p38 MAPK to induce the brown fat thermogenic program in mouse and human adipocytes. J Clin Investig. 2012;122(3):1022–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Makri ES, Evripidou K, Polyzos SA. Circulating leptin in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-related liver fibrosis: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;39(5):806–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tutunchi H, Ostadrahimi A, Hosseinzadeh-Attar M, et al. A systematic review of the association of neuregulin 4, a brown fat–enriched secreted factor, with obesity and related metabolic disturbances. Obes Rev. 2020;21(2): e12952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gong XM, Li YF, Luo J, et al. Gpnmb secreted from liver promotes lipogenesis in white adipose tissue and aggravates obesity and insulin resistance. Nat Metab. 2019;1(5):570–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hondares E, Rosell M, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Hepatic FGF21 expression is induced at birth via PPARα in response to milk intake and contributes to thermogenic activation of neonatal brown fat. Cell Metab. 2010;11(3):206–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Thomou T, Mori MA, Dreyfuss JM, et al. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. ESPE. 2017. 10.1530/ey.15.11.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mancina RM, Spagnuolo R. Cross talk between liver and adipose tissue: a new role for PNPLA3? Liver Int. 2020;40(9):2074–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kaffe E, Roulis M, Zhao J, et al. Humanized mouse liver reveals endothelial control of essential hepatic metabolic functions. Cell. 2023;186(18):3793-3809.e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Castellanos-Jankiewicz A, Guzmán-Quevedo O, Fénelon VS, et al. Hypothalamic bile acid-TGR5 signaling protects from obesity. Cell Metab. 2021;33(7):1483-1492.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Asami J, Kimura KT, Fujita-Fujiharu Y, et al. Structure of the bile acid transporter and HBV receptor NTCP. Nature. 2022;606(7916):1021–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Donkers JM, Kooijman S, Slijepcevic D, et al. NTCP deficiency in mice protects against obesity and hepatosteatosis. JCI Insight. 2019;4(14): e127197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Velazquez-Villegas LA, Perino A, Lemos V, et al. TGR5 signalling promotes mitochondrial fission and beige remodelling of white adipose tissue. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rose AJ, Díaz MB, Reimann A, et al. Molecular control of systemic bile acid homeostasis by the liver glucocorticoid receptor. Cell Metab. 2011;14(1):123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Raposo HF, Forsythe P, Chausse B, et al. Novel role of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP): attenuation of adiposity by enhancing lipolysis and brown adipose tissue activity. Metabolism. 2021;114:154429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wei S, Wang L, Evans PC, et al. NAFLD and NASH: etiology, targets and emerging therapies. Drug Discov Today. 2024;29(3):103910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhang Y, Zhao X, Dong X, et al. Activity-balanced GLP-1/GDF15 dual agonist reduces body weight and metabolic disorder in mice and non-human primates. Cell Metab. 2023;35(2):287-298.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yang C, Zhu D, Liu C, et al. Lipid metabolic reprogramming mediated by circulating Nrg4 alleviates metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease during the early recovery phase after sleeve gastrectomy. BMC Med. 2024;22(1):164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Blondin DP, Nielsen S, Kuipers EN, et al. Human brown adipocyte thermogenesis is driven by β2-AR stimulation. Cell Metab. 2020;32(2):287-300.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Not applicable.