Abstract

A sensitive and specific method has been developed to enumerate viable L. pneumophila and other Legionella spp. in water by epifluorescence microscopy in a short period of time (a few hours). This method allows the quantification of L. pneumophila or other Legionella spp. as well as the discrimination between viable and nonviable Legionella. It simultaneously combines the specific detection of Legionella cells using antibodies and a bacterial viability marker (ChemChrome V6), the enumeration being achieved by epifluorescence microscopy. The performance of this immunological double-staining (IDS) method was investigated in 38 natural filterable water samples from different aquatic sources, and the viable Legionella counts were compared with those obtained by the standard culture method. The recovery rate of the IDS method is similar to, or higher than, that of the conventional culture method. Under our experimental conditions, the limit of detection of the IDS method was <176 Legionella cells per liter. The examination of several samples in duplicates for the presence of L. pneumophila and other Legionella spp. indicated that the IDS method exhibits an excellent intralaboratory reproducibility, better than that of the standard culture method. This immunological approach allows rapid measurements in emergency situations, such as monitoring the efficacy of disinfection shock treatments. Although its field of application is as yet limited to filterable waters, the double-staining method may be an interesting alternative (not equivalent) to the conventional standard culture methods for enumerating viable Legionella when rapid detection is required.

Legionella pneumophila, the causative agent of Legionnaires' disease, was first recognized in 1977 following an epidemic of acute pneumonia among veterans of the American Legion in Philadelphia, Pa., and led to the discovery of a new bacterial species and genus (10, 34). Since then, 47 species and more than 60 serogroups have been recognized (7, 21, 24, 29, 43). Although the vast majority of Legionnaires' disease cases are due to L. pneumophila (46), 21 other Legionella species have been reported as pathogenic in humans (19, 42, 45, 56). Legionnaires' disease is the most severe form of infection, which includes pneumonia, and the fatality rate can approach 50% in immunocompromised patients (59). Over the last few years, the reported incidence of legionellosis has steadily increased. Numerous outbreaks have been documented. One of the worst recorded occurred recently (from November 2003 to January 2004) in the industrial region of Lens in the North of France, resulting in 86 cases of legionellosis and 15 deaths (40).

Outbreaks of Legionnaires' disease have been traced to a wide variety of environmental water sources, including cooling towers, hot tubs, showerheads, whirlpools and spas, and public fountains. These outbreaks have occurred in the home, offices, hotels, hospitals, and cruise ships, among other locations (3, 16, 20, 51, 55). Surveying and monitoring of legionellae in the environment are needed to prevent and control legionellosis, and Legionella concentrations in environmental sites may be used as a predictive risk factor (47). When high levels of Legionella are detectable in hot water systems, disinfection of water is critical for controlling outbreaks of legionellosis. Disinfection treatments are usually carried out by oxidizing biocides such as chlorine.

The standard culture technique is the most commonly used method for environmental surveillance of Legionella (2, 25). This method allows the isolation and the quantification of legionellae from environmental water, but it does have limitations. First, this method requires selective media and prolonged incubation periods (there is an interval of up to 10 days between taking a water sample and getting results). Second, bacterial loss during the concentration stage (centrifugation or filtration) followed by decontamination with heat (50°C for 30 min) or acid (pH 2 for 5 min) leads to a decrease in isolated Legionella. Third, the presence of background organisms may interfere with Legionella growth, leading to an underestimation of the real number of legionellae present in the sample. Finally, like many other bacteria, legionellae spp. have been detected as noncultivable cells (or PCR-inducing signals) from water samples (22, 23), but their infectivity in these samples has not been demonstrated.

The development of more rapid and sensitive alternative methods for the detection and quantification of viable Legionella cells without cultivation is of increasing importance for water monitoring, legionellosis prevention, and reduction in disinfecting treatment costs of water systems. PCR methods appeared as attractive alternatives to the conventional culture method for the detection of slow-growing and fastidious bacteria such as Legionella. In recent years, different PCR-based methods for the detection and quantification of Legionella in water have been described. PCR methodology has been used primarily against the 5S and 16S rRNA genes and against the macrophage infectivity potentiator (mip) gene of L. pneumophila (6, 13, 28, 30-32, 41, 49, 52, 54, 58). However, all PCR assays lack the ability to discriminate between living and nonliving (noninfectious) Legionella cells. Recently, a rapid method based on an immunofluorescence assay combined with detection by solid-phase cytometry (ChemScanRDI detection) has been described (4). This method achieves detection and enumeration of Legionella pneumophila in hot water systems within 3 to 4 h. However, like PCR approaches, this method detects viable as well as dead Legionella cells, whereas only live or viable bacteria are able to cause infections in human and represent an interest for public health. The development of new and rapid assays that combine both specific detection and viability criteria is essential for monitoring water quality and legionellosis prevention.

A wide array of methods based on the use of fluorescent probes targeting different cellular functions have been described for rapid assessment of microbial viability. Some of them are based on assessment of cell membrane integrity with nucleic acid dye (11) or on the capability of cells to maintain a membrane potential as determined by probe uptake or exclusion (33). Others detected the respiratory activity of bacteria using different tetrazolium salts (8, 26, 48) or the presence of esterase activity and cell membrane integrity using fluorogenic esters (15). Additionally, the capacity of cells to maintain a pH gradient (pHin higher than pHout) may also supply information about viability (12).

The aim of this study was to develop and validate a sensitive and specific method to detect and enumerate viable Legionella cells in water by epifluorescence microscopy in a short period of time (a few hours). This method, based on double-staining fluorescent labeling using a bacterial viability marker and specific antibodies, allows simultaneous detection of L. pneumophila and other Legionella species in water samples as well as the discrimination between viable and nonviable Legionella cells. It thus allows the rapid monitoring of the efficiency of disinfection treatments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The strains used in this study included 14 serogroups of Legionella pneumophila, 18 strains of other Legionella species, and 15 non-Legionella strains (Table 1). All the strains, collected by the Pasteur Institute of Lille (France), were kept in liquid nitrogen. Legionella was grown on buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE) agar supplemented with l-cysteine and ferric pyrophosphate (OXOID Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) (17). Non-Legionella strains were grown on LB (Lennox L) agar (Invitrogen, Paisley, Scotland).

TABLE 1.

List of Legionella and non-Legionella strains tested for the specificity of antibodies used for the immunological double-staining method

| Strain | Reference no. | Reactivity with antibodiesa

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti- L. pneumophila sg 1-14 | Anti-Legionella spp. | ||

| L. pneumophila sg 1 | ATCC 33152 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 2 | ATCC 33154 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 3 | ATCC 33155 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 4 | ATCC 33156 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 5 | ATCC 33216 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 6 | CIP 103381 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 7 | CIP 103382 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 8 | CIP 103383 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 9 | CIP 103384 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 10 | CIP 103385 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 11 | CIP 103386 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 12 | CIP 103387 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 13 | CIP 103388 | + | − |

| L. pneumophila sg 14 | NCTC 12174 | + | − |

| L. anisa | CIP 103870T | − | + |

| L. bozemanii sg 1 | ATCC 33217 | − | + |

| L. brunensis | NCTC 12240 | − | + |

| L. cherrii | NCTC 11976 | − | − |

| L. dumoffii sg 1 | NCTC 11370 | − | + |

| L. erythra sg 1 | NCTC 11977 | − | − |

| L. feeleii sg 1 | NCTC 12022 | − | + |

| L. gormanii sg 1 | ATCC 33297 | − | + |

| L. hackeliae sg 1 | NCTC 11979 | − | + |

| L. jordanis sg 1 | ATCC 33623 | − | + |

| L. longbeachae sg 1 | ATCC 33462 | − | + |

| L. maceachernii | ATCC 35300 | − | + |

| L. micdadei sg 1 | NCTC 33218 | − | + |

| L. oakridgensis sg 1 | ATCC 33761 | − | + |

| L. parisiensis sg 1 | NCTC 11983 | − | + |

| L. rubrilucens | NCTC 11987 | − | − |

| L. spiritensis | NCTC 11990 | − | − |

| Citrobacter freundii | ATCC 8090 | − | − |

| Enterobacter cloacae | NCTC 13168 | − | − |

| Escherichia coli | NCTC 1677 | − | − |

| Hafnia alvei | CUETM 77/33T | − | − |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | CIP 104216 | − | − |

| Klebsiella planticola | ATCC 33531 | − | − |

| Micrococcus luteus | ATCC 9341 | − | − |

| Morganella morganii | NCTC 2818 | − | − |

| Proteus mirabilis | CUETM 85/121T | − | − |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATCC 14138 | − | − |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | CIP 6913T | − | − |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium | CIP 5858 | − | − |

| Serratia marcescens | CIP 104221 | − | − |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | CIP 6821 | − | − |

| Xanthomonas maltophila | CIP 6077T | − | − |

+, positive reaction; −, negative reaction.

Isolation of Legionella from natural water samples was performed by culture according to the recommendations of the French Standard method AFNOR-NFT 90-431 (2), which conforms to International Standard method ISO 11731 (24). One-liter samples of water were concentrated by filtration on a 0.4-μm-pore-diameter polycarbonate membrane (Isopore, Millipore, Ireland). After filtration, bacteria collected on the membranes were resuspended in 5 ml of the water to be analyzed by sonication, and 0.1 ml of the suspension was spread on a 90-mm petri dish containing BCYE agar supplemented with vancomycin, polymyxin B, cycloheximide, and glycine (GVPC medium) (OXOID Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, England). Acid and heat treatments for selective inhibition of non-Legionella bacteria were performed as described previously (2, 18). Briefly, 2 ml of the suspension was mixed with an equal volume of 0.2 M KCl-HCl buffer (pH 2), and the mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature for 5 min ± 0.5 min before inoculating 0.2 ml of the buffer-treated suspension onto GVPC plates. For heat treatment, 1 ml of the concentrate was treated at 50°C ± 1°C for 30 min ± 1 min before spreading of 0.1 ml onto GVPC plates. The inoculated plates were then incubated for 7 to 10 days at 37°C ± 1°C. Smooth colonies showing a grayish-white or sometimes a grey-blue-purple, yellow, or green color were counted as suspicious legionellae to be confirmed. Up to 5 to 7 colonies of suspected Legionella colonies were subcultured onto BCYE agar, BCYE agar without l-cysteine, and blood agar for verification (2, 9). The isolated colonies growing only on BCYE agar were determined to be Legionella colonies. Several colonies isolated from each positive sample were used for determining the species and/or serogroups by latex slide agglutination tests with polyclonal antisera against L. pneumophila serogroup 1, L. pneumophila serogroups 2 to 14, and Legionella spp. (OXOID Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, England).

Pure culture of Legionella was enumerated by spreading onto BCYE medium (without antibiotics).

Viability staining procedure.

Assessment of the viability of Legionella cells was analyzed using the ChemChromeV6 (CV6) (Chemunex, Ivry-sur-Seine, France). This marker consists of a nonfluorescent precursor that is internalized and cleaved into a green fluorescent product (λemission = 520 nm) by esterases present in live bacteria. The cells remain fluorescent only if their membranes are intact and the probe is unable to diffuse out. This probe requires both active intracellular enzymes and intact membranes for cells to be counted as viable. Pure cultures of Legionella were serially diluted in peptone water (bioMérieux). Samples (1 ml) were filtered through sterile, black polyester membranes (CB04; Chemunex, Ivry-sur-Seine, France). Each membrane was incubated at 30°C for 30 min in the dark on an absorbent pad soaked with CV6 labeling solution according to the manufacturer's instructions. After labeling, cells with esterase activity were enumerated with the ChemScanRDI solid-phase cytometer (Chemunex). The ChemScan laser-scanning device has been described elsewhere previously (38). Essentially, the membrane is placed in the instrument and the entire filter surface is scanned within about 3 min. The system allows enumeration and differentiation between labeled microorganisms and autofluorescent particles present in the sample. A visual validation of all the ChemScanRDI results was made by transferring the membrane to an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse E600) fitted with a motorized stage. Under the control of the ScanRDI software, each fluorescing particle was examined to confirm that it was a Legionella cell stained with CV6. Formaldehyde-fixed heat-killed Legionella cells were used as controls. ChemScanRDI results were compared with the number of CFU detected by culture.

Immunofluorescence labeling techniques.

Two commercial polyclonal antibodies (m-TECH, Inc.) were used in this study: an anti-Legionella pneumophila (serogroups [sg] 1 to 14) antibody and an anti-Legionella species antibody which recognizes 15 species and 19 serogroups of Legionella other than L. pneumophila associated with diseases (L. bozemanii sg 1 and sg 2, L. dumoffi sg 1, L. gormanii sg 1, L. micdadei sg 1, L. longbeachae sg 1 and sg 2, L. jordanis sg 1, L. oakridgensis sg 1, L. wadsworthii sg 1, L. feeleii sg 1 and sg 2, L. sainthelensi sg 1, L. anisa sg 1, L. santicrucis sg 1, L. hackeliae sg 1 and sg 2, L. maceacherni sg 1, and L. parisiensis sg 1).

The specificity of anti-Legionella antibodies was verified by a direct fluorescent antibody test against 18 species of Legionella, 14 serogroups of L. pneumophila, and 15 non-Legionella strains that share the same ecological niche as Legionella or are phylogenetically close to the Legionella genus (Table 1). Briefly, colonies were dispersed in 0.37% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) for 15 min. A drop of each suspension was then placed on multiwell slides, allowed to dry at room temperature, and then heat fixed. Wells were overlaid with the respective fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled antibody and incubated in a moist chamber at 37°C for 1 h. Unbound antibody was removed by soaking for 10 minutes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, and air dried. Slides were mounted with 50% glycerol in PBS prior to examination by epifluorescence microscopy.

IDS method.

To optimize the labeling protocol, pure cultures of L. pneumophila sg 1 or of Legionella species other than L. pneumophila were diluted in peptone water (bioMérieux) in order to obtain about 500 to 1,000 bacteria per membrane after filtration. For natural water samples, different volumes (50 to 100 ml) of water were filtered depending on the contents of particles in suspension naturally present in the samples. Particles can fill in membranes, making the further visualization of stained bacteria difficult and increasing background noise. L. pneumophila cells were enumerated by the immunological double-staining (IDS) method using the anti-L. pneumophila (serogroups 1 to 14) antibody, whereas the preparation of a cocktail of two antibodies (anti-Legionella species and anti-L. pneumophila serogroups 1 to 14 antibodies) was necessary for the enumeration of Legionella.

Samples were filtered through sterile black polyester membranes (CB04; Chemunex, Ivry-sur-Seine, France) under vacuum, retaining all the bacteria. The membranes were treated with 100 μl of biotin-labeled antibodies diluted in 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Roche, Mannheim, Germany)-0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in PBS (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) for 1 h at 37°C. Membranes were then rinsed several times with PBS-Tween-BSA buffer. Streptavidin conjugated to Red670 (Invitrogen SARL, Cergy Pontoise, France) (λemission = 670 nm) diluted in the same washing buffer was applied to the membrane for 30 min at room temperature in order to detect the trapped Legionella cells specifically labeled with antibodies. Membranes were rinsed again with PBS-Tween-BSA buffer before viability staining. Staining for bacterial viability was performed using the CV6 protocol established above. The specific fluorescence of stained bacterial cells was observed under an epifluorescent microscope. Viable Legionella cells were defined as those bacteria showing both green and red fluorescence. The number of “dead” and “living” Legionella cells in each sample was estimated manually from the counts of 100 microscopic fields using a ×50 lens. Enumerations were determined by switching the epifluorescence filters of the microscope. The membrane filter microscope factor (MFMF) was used to calculate Legionella concentrations. The MFMF, which depends on the microscope objective lens, was determined by dividing the filter area by the area of the microscope field (determined with a stage micrometer). Legionella concentrations were calculated as follows: number of Legionella per liter = (average Legionella count/microscope field) × (MFMF) × 1,000/volume (ml) filtered. The values were converted to logarithms.

Chlorination treatment.

The biocide used for disinfection experiments was chlorine. The chlorine solution was freshly prepared from sodium hypochlorite (9.6°). A volume of 1.1 liter of each natural water sample to be tested was treated with disinfectant (10 mg of free chlorine per liter) for 24 h. Chlorine was neutralized by the addition of sodium thiosulfate (0.01%, final concentration) after treatment. Analyses were performed on these samples for culturable Legionella and for total and viable (metabolically active) Legionella. One liter of each sample was analyzed by the standard culture method (2) performed as described above, and 100 ml of the same sample was enumerated by IDS method using one or two anti-Legionella antibodies. Control experiments of untreated samples were done to determine the initial concentration of culturable and viable Legionella. Microscopic enumeration results were obtained from counts of 100 microscopic fields.

RESULTS

In the attempt to detect viable Legionella in water samples, we optimized a protocol allowing the detection of Legionella cells stained simultaneously with a taxonomic probe (antibodies) and a viability dye (ChemChromeV6). Before establishing a double-staining method, a separate evaluation of the two staining methods was necessary.

Assessment of viability of Legionella using ChemChrome V6.

Chemchrome V6 was shown to be well adapted to discriminate viable and dead Legionella cells. The ability of this fluorogenic ester to assess the viability of Legionella cells was first investigated by epifluorescence microscopy. Only esterases of viable bacteria cleave the nonfluorescent substrate, retaining the green fluorescent end product inside the cell. Viable Legionella cells were brightly stained with CV6 in contrast to heat-killed Legionella, which did not show green fluorescence. To better evaluate the efficiency of the CV6 dye for assessment of viability, samples prepared from pure cultures of different species of Legionella were enumerated by cytometry using a laser solid-phase cytometer, ChemScanRDI (Chemunex), and counts were compared with those predicted from culture. Table 2 shows the results obtained from the comparison between CV6-stained cell counts on ChemScanRDI and the counts obtained from BCYE culture counts (CFU counts). For all species of Legionella analyzed by solid-phase cytometry, CV6 counts were higher than CFU counts. The ratio of ChemScan counts to culture counts varied from 1.24 to 6.87. Heat-killed Legionella cells stained with CV6 were not detectable by solid-phase cytometry.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of viable counts (CV6-stained cells) determined by solid-phase cytometry (ChemScan) and culture counts (BCYE) obtained from independent spiked pure cultures of different Legionella species

| Strain | No. of CV6+ cells/liter (ChemScan) | No. of CFU/liter (culture) | Ratio of ChemScan/culture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legionella pneumophila sg 1 | 4.7 × 105 | 1.7 × 105 | 2.76 |

| Legionella gormanii | 6.9 × 105 | 4.5 × 105 | 1.53 |

| Legionella micdadeii | 6.2 × 105 | 3.1 × 105 | 2 |

| Legionella anisa | 9.5 × 105 | 2.5 × 105 | 3.8 |

| Legionella longbeachae | 1.1 × 106 | 1.6 × 105 | 6.87 |

| Legionella parisiensis | 9 × 105 | 3.2 × 105 | 2.81 |

| Legionella hackeliae | 2.4 × 105 | 1.5 × 105 | 1.6 |

| Legionella rubrilucens | 6.2 × 105 | 3.3 × 105 | 1.87 |

| Legionella pneumophila sg 1 | 3.9 × 105 | 5.7 × 104 | 6.84 |

| Legionella gormanii | 1.2 × 106 | 9.7 × 105 | 1.24 |

| Legionella micdadeii | 3.1 × 105 | 2.3 × 105 | 1.34 |

Specificity of the immunological detection of Legionella.

For the specific detection of Legionella, two commercial polyclonal antibodies were used: an anti-Legionella pneumophila serogroups 1 to 14 antibody and an anti-Legionella species antibody which recognizes the major Legionella species and serogroups other than L. pneumophila that are associated with disease. The specificity of the fluorescent antibodies was tested by reactivity to a set of pure cultures of Legionella and non-Legionella strains with a direct fluorescent antibody test. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibodies were found to be specific for serogroups and species against which they were raised. They were shown not to be reactive with the 15 non-Legionella strains tested (Table 1).

Optimization of the IDS protocol on pure cultures of Legionella.

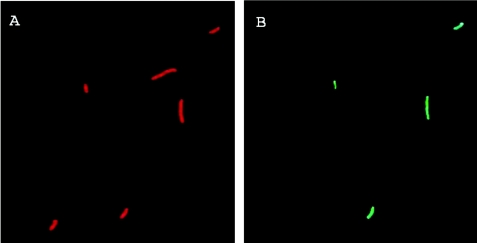

For double labeling, antibodies were coupled to the fluorochrome Red670. By using selective filter sets, it is possible to distinguish cells labeled for viability from those labeled with antibodies based on the emission spectrum of the two fluorochromes. ChemChrome V6 fluoresces predominantly green and has essentially spectral properties similar to those of fluorescein. Red670-labeled Legionella cells are counted based on their red fluorescence. There is no overlap between the emission spectrum of CV6 and that of Red670. Our staining protocol allows the discrimination between viable Legionella (green- and red-stained bacteria) from those dead having damaged membranes (red-stained bacteria) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Epifluorescent micrographs of a Legionella population stained by the immunological double-stain method. A and B show the same field visualized using selective filter sets. (A) Legionella cells stained with the Red670-coupled anti-Legionella antibody. (B) The same field as in panel A showing Legionella cells labeled for viability using the CV6 dye. Viable Legionella cells are defined as those bacteria showing green and red fluorescence simultaneously.

Enumeration of viable Legionella cells by the IDS method in environmental water samples.

It was of interest to test the immunological double-staining method for enumerating Legionella spp. in natural water samples as opposed to laboratory-grown pure cultures of Legionella cells. In this configuration, the discrimination and the performance of the IDS method could be investigated in the presence of large numbers of other viable bacteria not belonging to the Legionella genus.

Natural water samples were analyzed directly using epifluorescence microscopy after the double-labeling procedure. Different background levels were observed depending on the nature of the samples. The presence of particulate material that accumulates during the concentration procedure may sometimes interfere with microscopic analysis.

A total of 38 environmental water samples from different aquatic sources including water from showerheads, decorative fountains, different hot water systems, and cold and deep well waters were examined for the presence of L. pneumophila and/or other Legionella spp. by the IDS method. The number of viable Legionella cells was counted, and results were compared with those obtained with the traditional culture method (2) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of viable Legionella spp. and viable L. pneumophila counts in natural water samples obtained by the reference culture method and by the IDS method

| Sample | Culture results

|

IDS results

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture count (log10 CFU/liter)

|

Latex Identification | Antibody | IDS count (log10 viable cells/liter)

|

|||

| 1st replicate | 2nd replicate | 1st replicate | 2nd replicate | |||

| 1 | <1.7 | NDa | Legionella | Lp1-14b + Lsppc | 3.59 | ND |

| 2 | 2 | ND | L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.33 | ND |

| 3 | <1.7 | ND | Legionella | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.5 | ND |

| 4 | 4.88 | ND | Legionella | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 5.04 | ND |

| 5 | 4.88 | ND | Legionella | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 5 | ND |

| 6 | 4.4 | ND | Legionella | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 3.93 | ND |

| 7 | 3.9 | ND | Legionella | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.55 | ND |

| 8 | 3.9 | ND | Legionella spp. and L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.55 | ND |

| 9 | 5.45 | ND | L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 5.29 | ND |

| 10 | <1.7 | ND | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 3.15 | ND | |

| 11 | <1.7 | ND | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.45 | ND | |

| 12 | 1.7 | ND | L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 3.74 | ND |

| 13 | 4.65 | ND | L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.53 | ND |

| 14 | 4.65 | ND | L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.94 | ND |

| 15 | 4.40 | ND | L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.09 | ND |

| 16 | 4.6 | ND | Legionella | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.58 | ND |

| 17 | <1.7 | ND | Lp1-14 + Lspp | <2.38d | ND | |

| 18 | <1.7 | ND | Lp1-14 + Lspp | <2.75d | ND | |

| 19 | <1.7 | ND | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 2.69 | ND | |

| 20 | 5.15 | 4.78 | L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 5.46 | 5.52 |

| 21 | 3.24 | ND | Legionella | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.12 | ND |

| 22 | 3.84 | 3.82 | Legionella | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.17 | 4.17 |

| 23 | <1.7 | <1.7 | Lp1-14 | 4.49 | 4.46 | |

| Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.59 | 4.59 | ||||

| 24 | 3.04 | 3.46 | Legionella spp. and L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 | 4.82 | 4.79 |

| Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.91 | 4.89 | ||||

| 25 | 6.4 | 5.48 | L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 | 5.57 | 5.6 |

| Lp1-14 + Lspp | 5.74 | 5.76 | ||||

| 26 | 1.7 | 2.18 | L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 | 4.15 | 4.14 |

| Lp1-14 + Lspp | 5 | ND | ||||

| 27 | 3.84 | 3.8 | L. pneumophila sg 1 | Lp1-14 | 4.53 | 4.57 |

| Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.89 | 4.98 | ||||

| 28 | 4.65 | 4.6 | L. pneumophila sg 1 | Lp1-14 | 4.54 | 4.61 |

| Lp1-14 + Lspp | 5.08 | 5.1 | ||||

| 29 | 4.40 | 4.65 | L. pneumophila sg 1 | Lp1-14 | 5.16 | 5.15 |

| Lp1-14 + Lspp | 5.31 | 5.29 | ||||

| 30 | <1.7 | ND | Lp1-14 | <2.95d | ND | |

| Lp1-14 + Lspp | <2.95d | ND | ||||

| 31 | 3.55 | ND | L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 | 5.47 | ND |

| Lp1-14 + Lspp | 5.61 | ND | ||||

| 32 | 4.40 | ND | L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 | 5.07 | ND |

| Lp1-14 + Lspp | 6.06 | 6.16 | ||||

| 33 | <1.7 | ND | Lp1-14 + Lspp | <2.25d | ND | |

| 34 | <1.7 | ND | Lp1-14 + Lspp | <2.25d | ND | |

| 35 | <1.7 | ND | Lp1-14 + Lspp | <2.25d | ND | |

| 36 | <1.7 | ND | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.6 | ND | |

| 37 | <1.7 | ND | Lp1-14 + Lspp | 4.66 | ND | |

| 38 | 3.2 | ND | L. pneumophila | Lp1-14 | 3.45 | ND |

| Lp1-14 + Lspp | 3.63 | ND | ||||

ND, not determined.

Lp-1-14, anti-Legionella pneumophila serogroups 1 to 14 antibody.

Lssp, anti-Legionella species antibody.

The detection limit depends on the number of microscope fields examined and the volume of water filtered.

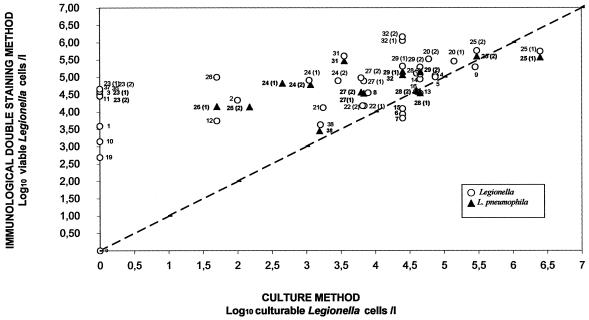

The recovery rate of the IDS procedure was similar to or higher than that with the standard culture method. IDS counts were higher than that based on standard culture in the majority of the samples analyzed. For water samples containing a high concentration of Legionella (log10 CFU/liter, ≥3), IDS and culture counts were close to the ideal linear relationship. However, for weakly concentrated samples (log10 CFU/liter, <3), no equivalence was found between the two methods (Fig. 2). In fact, for these samples, counts obtained by the IDS method were always higher than those obtained by culture and sometimes exceeded the latter by 2 log or more. Thirty-two samples were positive using the IDS method, and 24 were positive by culture. Samples 17, 18, 30, 33, 34, and 35 were negative by IDS labeling and by culture. These samples correspond to cold domestic waters or well deep waters known to be free of Legionella. Eight samples analyzed in singular (samples 1, 3, 10, 11, 19, 36, 37) or in duplicates (sample 23) were positive by the IDS method but negative in culture, whereas the opposite was never found. It is interesting that the sampling temperature of these water samples (excepting samples 1 and 37) exceeded 45°C.

FIG. 2.

Graph comparing the logarithms of concentrations of L. pneumophila (▴) or Legionella spp. (○) per liter in natural water samples determined by IDS method and standard culture method. The straight line represents the theoretical line of equivalence.

The detection limit of the IDS method is dependent on the volume of water filtered and the number of microscope fields examined. Under our experimental conditions, the detection limit of the IDS method is 176 Legionella cells per liter (log10 = 2.25) for 100 ml of water analyzed and 100 microscope fields observed. This limit is theoretically reduced to a single Legionella cell per filtered volume if the entire membrane is scanned. By comparison, the detection limit of the culture method used in this study is 50 CFU per liter (2). Volumes higher than 100 ml of natural waters are not recommended to be analyzed by the IDS method because of the filtration capacity of the membrane used. Particles present in the natural samples fill in membranes and contribute to increased background noise.

Intralaboratory reproducibility of the IDS method.

Ten environmental samples (samples 20, 22 to 29, and 32) were examined for the presence of L. pneumophila and/or other Legionella spp. in two replicates in order to determine the reproducibility of the IDS method. Each sample was divided into two identical portions, and each portion was analyzed by two different operators using both IDS and culture methods. Table 4 compares L. pneumophila and/or other Legionella species counts obtained for each replicate with the IDS method and with the standard culture method. Results show that the IDS method exhibits an excellent reproducibility, better than that of the culture method used (Table 4). A maximal difference of 0.1 log was observed between the two replicates of each sample analyzed by the IDS method. Conversely, the difference of two replicates enumerated by the standard culture method can be up to 1 log.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of reproducibility of the IDS method with the standard culture method NF T90-431a

| Sample |

Legionella spp.

|

L. pneumophila

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDS

|

Culture

|

IDS

|

Culture

|

|||||||||||||

| Replicate

|

Mean | SD (CV) | Replicate

|

Mean | SD (CV) | Replicate

|

Mean | SD (CV) | Replicate

|

Mean | SD (CV) | |||||

| I | II | I | II | I | II | I | II | |||||||||

| 20 | 5.46 | 5.52 | 5.49 | 0.04 (0.8) | 5.15 | 4.78 | 4.96 | 0.26 (5.3) | ||||||||

| 22 | 4.17 | 4.17 | 4.17 | 0.00 | 3.84 | 3.82 | 3.83 | 0.01 (0.4) | ||||||||

| 23 | 4.59 | 4.59 | 4.59 | 0.00 | <1.70 | <1.7 | 4.49 | 4.46 | 4.48 | 0.02 (0.5) | <1.70 | <1.70 | ||||

| 24 | 4.91 | 4.89 | 4.90 | 0.01 (0.3) | 3.04 | 3.46 | 3.25 | 0.3 (9.1) | 4.82 | 4.79 | 4.81 | 0.02 (0.4) | 3.04 | 3.46 | 3.25 | 0.30 (9.1) |

| 25 | 5.74 | 5.76 | 5.75 | 0.01 (0.3) | 6.40 | 5.48 | 5.94 | 0.65 (11.0) | 5.57 | 5.60 | 5.59 | 0.02 (0.4) | 6.40 | 5.48 | 5.94 | 0.65 (11.0) |

| 26 | 4.15 | 4.14 | 4.15 | 0.01 (0.2) | 1.70 | 2.18 | 1.94 | 0.34 (17.5) | ||||||||

| 27 | 4.89 | 4.98 | 4.94 | 0.06 (1.3) | 3.84 | 3.80 | 3.82 | 0.03 (0.7) | 4.53 | 4.57 | 4.55 | 0.03 (0.6) | 3.84 | 3.80 | 3.82 | 0.03 (0.7) |

| 28 | 5.08 | 5.10 | 5.09 | 0.01 (0.3) | 4.65 | 4.60 | 4.62 | 0.04 (0.8) | 4.54 | 4.61 | 4.58 | 0.05 (1.1) | 4.65 | 4.60 | 4.63 | 0.04 (0.8) |

| 29 | 5.31 | 5.29 | 5.30 | 0.01 (0.3) | 4.40 | 4.65 | 4.52 | 0.18 (3.9) | 5.16 | 5.15 | 5.16 | 0.01 (0.1) | 4.40 | 4.65 | 4.53 | 0.18 (3.9) |

| 32 | 6.06 | 6.16 | 6.11 | 0.07 (1.2) | 4.40 | |||||||||||

Natural water samples were analyzed in duplicate for the presence of L. pneumophila or other Legionella spp. Count results are expressed in log10 viable cells/titer for the IDS method and log10 CFU/liter for the culture method. SD, standard deviation. Values in the parentheses represent the coefficient of variation (CV) between two replicates (I and II) expressed in a logarithmic scale.

Evaluation of the efficacy of chlorine treatments.

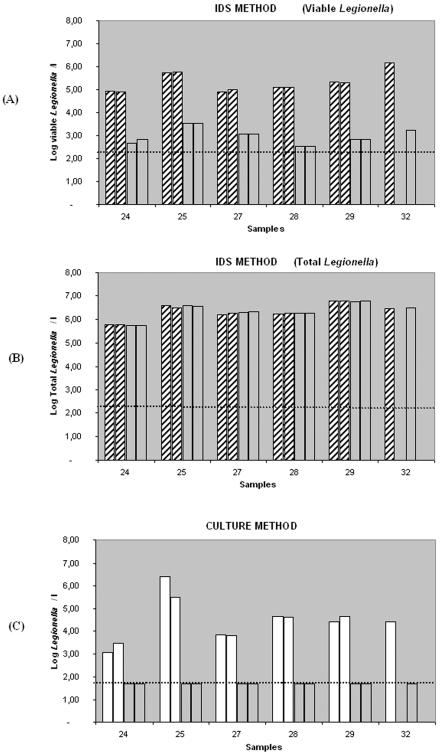

In order to determine whether the IDS method could be used to test the efficiency of disinfection shock treatments in emergency situations, six natural water samples were exposed to 10 mg of free chlorine per liter for 24 h. Samples were assayed in singular (sample 32) or in duplicate (samples 24, 25, 27, 28, and 29) in order to determine the effects of this disinfectant on viability (IDS method) and on growth (culture method). Control experiments of untreated samples were done to determine the initial concentration of viable and culturable Legionella. After chlorine treatment, surviving Legionella cells were enumerated by the IDS method and by the standard culture method (2). Figure 3 compares the results obtained for viable, total (dead plus viable), and culturable Legionella concentrations for each sample before and after chlorination using both methods. To determine viable Legionella counts, volumes from 5 to 50 ml were analyzed for each sample by the IDS method. In all cases, no viable Legionella cells were observed by double staining after 24 h of chlorination. Counts for dead Legionella cells were achieved on the basis of their red fluorescence because chlorine inactivation of Legionella cells did not destroy their reactivity to antibodies. In contrast to viable counts that dropped following the chlorination, the total count (dead plus viable Legionella cells) remained constant before and after treatment. Chlorine-treated Legionella cells were not detectable by culture. Legionella cells quickly lost their capacity to form colonies on BCYE agar plates. Actually, no Legionella cells were detected by culture after 5 min of chlorine treatment.

FIG. 3.

Evaluation of the efficacy of chlorine treatments by IDS (A and B) and by culture (C). Histograms represent the Legionella counts before and after exposure to 10 mg per liter of free chlorine for 24 h in six natural water samples analyzed by IDS method and by culture in a single assay (sample 32) or in duplicate (samples 24, 25, 27, 28, and 29). (A) Results of viable counts determined by the IDS method before chlorination (hatched bars) and after chlorination (transparent bars). (B) Results of total (dead plus viable) counts determined by the IDS method before (hatched bars) and after (transparent bars) chlorination. Note that the total Legionella counts remained constant after treatment. (C) Results obtained by the standard culture method before (white bars) and after (transparent bars) chlorine treatment. Dotted lines indicate the limit of detection of each method.

DISCUSSION

We report a sensitive, specific, and rapid (a few hours) method to detect and enumerate viable L. pneumophila and other Legionella spp. in water using epifluorescence. Our method combines a bacterial viability test and a specific staining using antibodies. Fluorescent stains can be distinguished on the basis of their respective emission wavelengths (green viability stain and red-specific stain). Viable Legionella cells are defined as those bacteria showing green and red fluorescence under epifluorescence microscopy.

The performance of the IDS method was investigated in natural filterable water samples. Numbers of viable Legionella cells in 38 water samples from different aquatic sources were determined by the IDS method, and results were compared to those obtained with the standard culture method (2). The IDS method appears to be at least as sensitive as this reference culture method. In the majority of water samples analyzed, IDS counts were higher than those obtained by culture. Eight of the 38 samples analyzed were even positive by the IDS method but negative by culture, whereas the contrary was never observed. Aurell et al. (4) obtained similar results using different antibodies directed against L. pneumophila and a solid-phase cytometry system. Three of 19 hot water samples tested in their study were shown to be positive by cytometry but negative by culture (ISO 11731 standard method).

Thus, equivalence of the IDS method and the culture method cannot be expected. Cultivability and viability are often considered synonymous terms, but strictly speaking, they measure different properties of the cells. The plate count measures the ability of the bacteria to grow and form a colony on a particular medium. The fluorescent viability probes target different cellular functions and measure the occurrence of metabolism or a particular functional activity in the bacteria. The failure of Legionella to form colonies does not necessarily give information about the potential physiological activity of the bacteria. For the samples in which culture method results were negative but IDS method results were positive as well as for those samples in which culture counts were consistently lower than the IDS counts, we may take into account the existence of injured and “viable but nonculturable” (VBNC) cells within stressed populations. Legionella pneumophila has been shown to form viable but nonculturable cells which may be responsible for the failure to culture viable L. pneumophila from some environmental sources (22, 23, 50). Bacteria exposed to potentially lethal environmental conditions including nutrient restriction, oxidative stress, heat, UV irradiation, osmotic stress, or sublethal concentrations of antibacterial compound undergo physiological or morphological alterations that complicate the detection and accurate enumeration of such stressed bacteria using available culture methods (26, 35). However, these VBNC forms of Legionella may be detected by using a dual-labeling method that combines a viability marker for specific anti-Legionella antibodies. In fact, nonculturable forms of Legionella obtained during extended starvation retain esterase activity for prolonged periods (P. Delgado-Viscogliosi et al., unpublished results). In this study, water temperature could be a factor leading to stressed Legionella populations. Actually, the sampling temperature of most of water samples in which no culturable Legionella cells were found but the presence of viable Legionella were shown by IDS was equal to or higher than 45°C.

The culture-based method may not detect all the viable Legionella cells in water samples. It gives a value for CFU; bacterial doublets or chains are counted as only one unit, and those that cannot grow under the prevailing conditions are not counted. In contrast, our method, which is based on an epifluorescence microscopic observation, can distinguish individual cells in Legionella clusters. Furthermore, the methodological problems in the isolation of legionellae from environmental water can also contribute to an underestimation of culturable Legionella cells. The use of a selective medium and pretreatment by acid or heating reduce the cultivability (58). For all these reasons, it could be concluded that the culture methods underestimate the population of Legionella. Nevertheless, the purpose of the analysis is to measure the infection risk, and what should be considered infectious is not clearly known. Colony-forming cells are probably able to colonize a sensitive host, and esterase-negative cells are probably unable to recover, but it is not known if nonculturable, esterase-positive cells are infectious. It will be difficult to test their infectivity because it is impossible to get a population containing only such cells.

It could also be argued that IDS (and a fortiori simple immunostaining methods) as wells as PCR methods overestimate the number of infectious units because they count cells or copies of genes but not propagule. Actually, if several infectious cells are bound in a stable cluster, they will not be able to infect several people. But a multicellular propagule could be more infectious than a single cell and also more resistant to adverse conditions. So, the “true” value for risk evaluation probably lies between the culture and IDS results.

The double-staining approach described in this study allows the detection and enumeration of viable L. pneumophila or other Legionella spp. in hot water systems within a few hours. Molecular methods have also previously been developed to increase the rapidity of Legionella analysis. They are able to achieve a high degree of sensitivity and specificity without the need for a complex cultivation and additional confirmation steps (6, 28, 31, 32, 41, 49, 52, 54, 58). Some of these methods allow the detection of culturable and/or nonculturable Legionella within hours instead of the days required with the reference culture method. Recently, a rapid method based on an immunofluorescence assay combined with detection by solid-phase cytometry (ChemScanRDI detection) has been described (4). This method achieves detection and enumeration of Legionella pneumophila in hot water systems within 3 to 4 h. Although both approaches measure two different parameters (gene copies and individual cells, respectively), neither of them is able to distinguish between viable and dead Legionella cells. Our IDS approach associates the viability criterion to the taxonomic affiliation of detected bacteria. This is one of the main advantages of the IDS method because only alive or viable (maybe culturable) Legionella cells cause disease and represent an interest for public health. This method can detect the viable noncultivable forms of Legionella which are still metabolically active but unable to form colonies on solid media. It has important public health significance because the VBNC Legionella might be a potential source of infection. VBNC Legionella forms can be resuscitated by coincubation with amoebae without any loss of virulence (50). Furthermore, VBNC Legionella spp. have been shown to be capable of causing pneumonic legionellosis (14), and exposure to high concentrations of them may be an important cause of Pontiac fever (39).

On the other hand, several PCR-based methods (5, 52, 53) as well as the assay described previously by Aurell et al. (4) detect the species Legionella pneumophila only. Potentially, any species of Legionella may cause the disease. A recent study indicated that Legionella species other than L. pneumophila may be important in the etiology of community-acquired pneumonia (36) and that their prevalence may have been underestimated due to inadequate diagnostic methods currently in use. Our double-staining approach allows simultaneous detection and discrimination of L. pneumophila and other Legionella species in water samples depending on the antibody used for analysis.

The detection limit of Legionella using the French standard culture method is 50 CFU liter−1 (log10 = 1.7) (2). Under our experimental conditions, the limit of detection of the IDS method was <176 Legionella cells per liter (log = 2.25). This detection limit depends on the number of microscope fields examined and the volume of water filtered.

Legionella spp. appear to represent a health risk to humans when a threshold value estimated at 104 to 105 CFU liter−1 is reached. Epidemiological data show that outbreaks of legionellosis occur at these concentrations (37, 44), and corrective actions such as chlorination must be taken promptly in the case of contaminations. Besides a monitoring of water quality, the IDS method described in this study also allows the evaluation of the efficiency of the disinfection measures as suggested by the chlorination results.

Our approach has two limitations. First, as for any method based on a manual enumeration using a microscope, the IDS assay may cause operator fatigue. It requires trained personnel to identify Legionella cells in natural water samples, which are smaller than cultured Legionella cells. The automation of the method by the use of solid-phase laser cytometry would ease the enumeration, even if it would not reduce the analysis time by much. Actually, the ChemScanRDI approach also requires a somewhat time-consuming manual confirmation step after laser scanning in order to validate each event selected by the cytometer as a true positive or a false positive. However, it offers the advantage of analyzing the whole membrane and reducing the detection limit of the method. Assays to enumerate double-stained Legionella by ChemScanRDI have been conducted in our laboratory. Results indicated that the reading in the red channel still needs some adaptations. Further developments are undertaken to transpose IDS methodology to the ChemScanRDI. Second, the application domain of the IDS method is limited as yet to filterable water. Cooling tower water, frequently cited as a source of infection in outbreaks of Legionnaires' disease (1, 15, 27, 57), cannot be easily analyzed by the IDS procedure due to interferences. The presence of particulate material that accumulates during the concentration procedure interferes with microscopic analysis. Research is under way to apply this method to nonfilterable waters including interfering particles.

In conclusion, the IDS method appears to be suited for rapid surveillance of hot water systems. It is based on an innovative principle combining viability with taxonomic specificity. The main advantage over the standard culture method is its rapidity, which allows results to be obtained within hours versus 10 days for culture. This rapidity may enable better control of water systems because corrective actions in the case of contamination can be taken promptly.

The IDS method may provide the basis for a decision for water system disinfection leading to reduction in treatment costs and enables monitoring of the effectiveness of disinfection treatment. Even if some technical improvements remain to be made, we can conclude that our double-staining approach is an interesting alternative (not equivalent) method to culture for enumerating viable Legionella cells when rapid detection is required, like in emergency situations.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. L. Drocourt (Chemunex, France) and N. Leden (AES, France) for their collaboration in this study. We also thank R. Pierce for critical reading of the manuscript. P. Delgado-Viscogliosi gratefully acknowledges E. Viscogliosi for fruitful discussions.

This work was supported by the French Ministère de l'Economie, des Finances et de l'Industrie (Programme RITEAU).

REFERENCES

- 1.Addiss, D. G., J. P. Davis, M. La Venture, P. J. Wand, M. A. Hutchinson, and R. M. McKinney. 1989. Community-acquired Legionnaires' disease associated with a cooling tower: evidence for longer-distance transport of Legionella. Am. J. Epidemiol. 130:557-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association Française de Normalisation. 1993. Testing water—detection and enumeration of Legionella et de Legionella pneumophila—general method by direct culture and membrane filtration. French standard AFNOR NF T90-431. Association Française de Normalisation, Paris, France.

- 3.Atlas, R. M. 1999. Legionella: from environmental habitats to disease pathology, detection and control. Environ. Microbiol. 1:283-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aurell, H., P. Catala, P. Farge, F. Wallet, M. Le Brun, J. H. Helbig, S. Jarraud, and P. Lebaron. 2004. Rapid detection and enumeration of Legionella pneumophila in hot water systems by solid-phase cytometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1651-1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballard, A. L., N. K. Fry, L. Chan, S. B. Surman, J. V. Lee, T. G. Harrison, and K. J. Towner. 2000. Detection of Legionella pneumophila using a real-time PCR hybridization assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4215-4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bej, A. K., M. H. Mahbubani, and R. M. Atlas. 1991. Detection of viable Legionella pneumophila in water by polymerase chain reaction and gene probes methods. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 57:597-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benson, R. F., and B. S. Fields. 1998. Classification of the genus Legionella. Semin. Respir. Infect. 13:90-99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhupathiraju, V. K., M. Hernandez, D. Landfear, and L. Alvarez-Cohen. 1999. Application of a tetrazolium dye as an indicator of viability in anaerobic bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 37:231-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bornstein, N., D. Marmet, M. Surgot, M. Nowicki, H. Meugnier, J. Fleurette, E. Ageron, F. Grimont, P. A. D. Grimont, W. L. Thacker, R. F. Benson, and D. J. Brenner. 1989. Legionella gratiana sp. nov. isolated from French spa water. Res. Microbiol. 140:541-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner, D. J., A. G. Steigerwalt, and J. E. McDade. 1979. Classification of the Legionnaires' disease bacterium: Legionella pneumophila, genus novum, species nova, of the family Legionellaceae, familia nova. Ann. Intern. Med. 90:656-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunthof, C. J., S. van den Braak, P. Breeuwer, F. M. Rombouts, and T. Abee. 1999. Rapid fluorescence assessment of the viability of stressed Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3681-3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chitarra, L. G., P. Breeuwer, R. W. Van Den Bulk, and T. Abee. 2000. Fluorescence assessment of intracellular pH as a viability indicator of Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88:809-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cloud J. L., K. C. Carroll, P. Pixton, M. Erali, and D. R. Hillyard. 2000. Detection of Legionella species in respiratory specimens using PCR with sequencing confirmation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1709-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuthbertson, W. C. 1954. Causes of death among dentists: a comparison with the general male population. J. Calif. Nev. State Dent. Soc. 30:159-160. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaper, J. P., and C. Edwards. 1994. The use of fluorogenic esters to detect viable bacteria by flow cytometry. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 77:221-228. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dondero, T. J., R. J. Rendtoriff, and G. F. Malluson. 1980. An outbreak of Legionnaires' disease associated with contaminated air conditioning cooling tower. N. Engl. J. Med. 302:365-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edelstein, P. H. 1981. Improved semiselective medium for isolation of Legionella pneumophila from contaminated clinical and environmental specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 14:298-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edelstein, P. H. 1985. Legionnaires' disease laboratory manual, 3rd ed. National Technical Information Service, Springfield, Va.

- 19.Fang, G. D., V. L. Yu, and R. M. Vickers. 1989. Disease due to the Legionellaceae (other than Legionella pneumophila). Historical, microbiological, clinical, and epidemiological review. Medicine 68:116-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fenstersheib, M. D., M. Miller, C. Diggins, S. Liska, L. Detweiler, S. B. Werner, D. Lindquist, W. L. Thacker, and R. F. Benson. 1990. Outbreak of Pontiac fever due to Legionella anisa. Lancet 336:35-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franzin, L., and P. Gioannini. 2000. Legionella taurinensis, a new species of Legionella isolated in Turin, Italy. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fry, J. C., and T. Zia. 1982. A method for estimating viability of aquatic bacteria by slide culture. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 53:189-198. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hay, J., D. V. Seal, B. Billcliffe, and J. H. Freer. 1995. Non-culturable Legionella pneumophila associated with Acanthamoeba castellanii: detection of the bacterium using DNA amplification and hybridization. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 78:61-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hookey, J. V., N. A. Saunders, N. K. Fry, R. J. Birtles, and T. G. Harrison. 1996. Phylogeny of Legionellaceae based on small-subunit ribosomal DNA sequences and proposal of Legionella lytica comb. nov. for Legionella-like amoebal pathogens. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46:526-531. [Google Scholar]

- 25.International Standards Organisation. 1998. Water quality—detection and enumeration of Legionella. International standard ISO 11731. International Standards Organisation (International Organization for Standardization), Geneva, Switzerland.

- 26.Joux, F., and P. Lebaron. 2000. Use of fluorescent probes to assess physiological functions of bacteria at single-cell level. Microbes Infect. 12:1523-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keller, D. W., R. Hajjeh, A. DeMaria, B. S. Fields, J. M. Pruckler, R. S. Benson, P. E. Kludt, S. M. Lett, L. A. Mermel, C. Giorgio, and R. F. Breiman. 1996. Community outbreak of Legionnaires' disease: an investigation confirming the potential for cooling towers to transmit Legionella species. Clin. Infect. Dis. 22:257-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koide, M., A. Saito, N. Kusano, and F. Higa. 1993. Detection of Legionella spp. in cooling water by the polymerase chain reaction method. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1943-1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lo Presti, F., S. Riffard, H. Meugnier, M. Reyrolle, Y. Lasne, P. A. Grimont, F. Grimont, F. Vandenesch, J. Etienne, J. Fleurette, and J. Freney. 1999. Legionella taurinensis sp. nov., a new species antigenically similar to Legionella spiritensis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lye, D., S. Fout, S. R. Crout, R. Danielson, C. L. Thio, and C. M. Paszko-Kolva. 1997. Survey of ground, surface, and potable waters for the presence of Legionella species by enviroamp PCR Legionella kit, culture, and immunofluorescent staining. Water Res. 31:287-293. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahbubani, M. H., A. K. Bej, R. Miller, L. Haff, J. DiCesare, and R. M. Atlas. 1990. Detection of Legionella with polymerase chain reaction and gene probes methods. Mol. Cell. Probes 4:175-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maiwald, M., K. Kissel, S. Srimuang, D. M. Von Kneel, and H. G. Sonntag. 1994. Comparison of polymerase chain reaction and conventional culture for the detection of legionellas in hospital water samples. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 76:216-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason, D. J., R Lopez-Amoros, R. Allman, J. M. Stark, and D. Lloyd. 1995. The ability of membrane potential dyes and calcafluor white to distinguish between viable and non-viable bacteria. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 78:309-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDade, J. E., C. C. Shepard, D. W. Fraser, T. R Tsai, M. A. Redus, and W. R. Dowdle. 1977. Legionnaires' disease: isolation of a bacterium and demonstration of its role in other respiratory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 297:1197-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McFeters, G. A., F. P. Yu, B. H. Pyle, and P. S. Stewart. 1995. Physiological assessment of bacteria using fluorochromes. J. Microbiol. Methods 21:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNally, C., B. Hackman, B. S. Fields, and J. F. Plouffe. 2000. Potential importance of Legionella species as etiologics in community acquired pneumonia (CAP). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 38:79-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meenhorst, P. L., A. L. Reingold, D. G. Groothuis, G. W. Gorman, H. W. Wilkinson, R. M. McKinney, J. C. Feeley, D. J. Brenner, and R. van Furth. 1985. Water-related nosocomial pneumonia caused by Legionella pneumophila serogroups 1 and 10. J. Infect. Dis. 152:356-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mignon-Godefroy, K., J. C. Guillet, and C. Butor. 1997. Solid-phase cytometry for detection of rare events. Cytometry 27:336-344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller, L. A., J. L. Beebe, N. C. Butler, H. Martin, R. Benson, R. E. Hoffman, and B. S. Fields. 1993. Use of polymerase chain reaction in an epidemiologic investigation of Pontiac fever. J. Infect. Dis. 168:769-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miquel, P. H., S. Haeghebaert, D. Che, C. Campese, C. Guitard, T. Brigaud, M. Thérouanne, G. Panié, S. Jarraud, and D. Ilef. 2004. Epidémie communautaire de légionellose, Pas-de-Calais, France, novembre 2003-janvier 2004. Bull. Epidemiol. Hebd. 36-37:179-181. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyamoto, H., H. Yamamoto, K. Arima, J. Fujii, K. Maruta, K. Izu, T. Shiomori, and S. I. Yoshida. 1997. Development of a new seminested PCR method for detection of Legionella species and its application to surveillance of legionellae in hospital cooling tower water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2489-2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munder, R. U. 2000. Other Legionella species, p. 2435-2441. In G. L. Mandell, J. E. Bennett, and R. Dolin (ed.), Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 5th ed., vol. 2. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park, M. Y., K. S. Ko, H. K. Lee, M. S. Park, and Y. H. Kook. 2003. Legionella busanensis sp. nov., isolated from cooling tower water in Korea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:77-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patterson, W. J., D. V. Seal, E. Curran, T. M. Sinclair, and J. C. McLuckie. 1994. Fatal nosocomial Legionnaires' disease: relevance of contamination of hospital water supply by temperature-dependent buoyancy-driven flow from spur pipes. Epidemiol. Infect. 112:513-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Presti, F. L., S. Riffard, F. Vandenesch, E. Ronco, P. Ichai, and J. Etienne. 1996. Liver-transplant patient with pneumonia yields first clinical isolate of Legionella parisiensis, p. 39-41. In Proceedings of the 11th Meeting of the European Working Group on Legionella Infection, Oslo, Norway.

- 46.Reingold, A. L., B. M. Thomason, B. J. Brake, L. Thacker, H. W. Wilkinson, and J. N. Kuritsky. 1984. Legionella pneumonia in the United States: the distribution of serogroups and species causing human illness. J. Infect. Dis. 149:819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shelton, B. G., G. K. Morris, and G. W. Gorman. 1993. Reducing risks associated with Legionella bacteria in building water systems, p. 279-281. In J. M. Barbaree, R. F. Breiman, and A. P. Dufour (ed.), Legionella: current status and emerging perspectives. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 48.Smith, J. J., and G. A. McFeters. 1997. Mechanisms of INT (2-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-phenyltetrazolium chloride) and CTC (5-cyano-2,3-ditotyl tetrazolium chloride) reduction in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Microbiol. Methods 29:161-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Starnbach, M. N., S. Falkow, and L. S. Tompkins. 1989. Species-specific detection of Legionella pneumophila in water by DNA amplification and hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:1257-1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steinert, M., L. Emody, R. Amann, and J. Hacker. 1997. Resuscitation of viable but nonculturable Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia JR32 by Acanthamoeba castellanii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2047-2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tobin, J. O., J. Beare, and M. S. Dunnill. 1980. Legionnaires' disease in a transplant unit: isolation of the causative agent from shower baths. Lancet ii:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Villari, P., E. Motti, C. Farullo, and I. Torre. 1998. Comparison of conventional culture and PCR methods for detection of Legionella pneumophila in water. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 27:106-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weir, S. C., S. H. Fischer, F. Stock, and J. G. Vee. 1998. Detection of Legionella by PCR in respiratory specimens using a commercially available kit. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 110:295-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wellinghausen, N., C. Frost, and R. Marre. 2001. Detection of legionellae in hospital water samples by quantitative real-time LighterCycler PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3985-3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winn, W. C., Jr. 1988. Legionnaires' disease: historical perspective. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1:60-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Winn, W. C., Jr. 1995. Legionella, p 533-544. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 6th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 57.World Health Organization. 1990. Epidemiology, prevention and control of legionellosis: memorandum from a W.H.O. meeting. Bull. W. H. O. 68:155-164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamamoto, H., Y. Hashimoto, and T. Ezaki. 1993. Comparison of detection methods for Legionella species in environmental water by colony isolation, fluorescent antibody staining, and polymerase chain reaction. Microbiol. Immunol. 37:617-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu, V. L. 2000. Legionella pneumophila, p. 2424-2435. In G. L. Mandell, J. E. Bennett, and R. Dolin (ed.), Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 5th ed., vol. 2. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]