Abstract

In Mycoplasma pneumoniae, the UGA opal codon specifies tryptophan rather than a translation stop site. This often makes it difficult to express Mycoplasma proteins in E. coli isolates. In this work, we developed a strategy for the one-step introduction of several mutations. This method, the multiple-mutation reaction, is used to simultaneously replace nine opal codons in the M. pneumoniae glpK gene.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a pathogen that lives on mucosal surfaces and causes diseases such as mild pneumonia, tracheobronchitis, and complications affecting the central nervous system, the skin, and mucosal surfaces (9, 14, 26). This bacterium possesses one of the smallest genomes of any free-living organism known so far. This reduced genome makes Mycoplasma spp. interesting from two points of view: (i) the analysis of these bacteria may help to identify the minimal set of genes that is required for independent life (7), and (ii) M. pneumoniae and its close relative M. genitalium are well suited for the development of the methods of the postgenomic era (10, 27). Another interesting aspect of the small genome is the observation that several enzymes of Mycoplasma spp. are “moonlighting”; i.e., they have multiple unrelated functions (11). This was discovered for glycolytic kinases, which are also active as nucleoside diphosphate kinases in M. pneumoniae and other Mycoplasma spp. (18).

However, the analysis of proteins from Mycoplasma spp. is hampered by a peculiarity of the genetic code of these bacteria: they use the UGA opal codon to incorporate tryptophan rather than as a stop codon as in the universal genetic code (8, 21). Thus, if cloned into Escherichia coli or other hosts, the genes from M. pneumoniae may contain many stop codons that prevent heterologous expression. Several strategies have been developed to solve this problem. For example, some M. pneumoniae genes, such as ptsH or hprK, do not possess UGA codons and thus require no special care (24). Expression of mollicute genes in Spiroplasma spp. that read the UGA as a tryptophan codon was reported, but these bacteria are difficult to handle (23). E. coli suppressor strains expressing an opal suppressor tRNA were developed, but they fail if multiple opal codons are present (22). M. pneumoniae genes containing few UGA codons have been expressed in Bacillus subtilis with low efficiency (12). In cases with only a few opal codons, these were changed by site-directed mutagenesis to allow expression in E. coli (13, 17). The M. pneumoniae P1 adhesin gene contains 21 opal codons, and a large-scale purification of the protein, though highly desired, has so far not been possible. In this case, protein fragments were expressed and purified (3). Finally, Mycoplasma genes could be synthesized in vitro from oligonucleotides; this strategy is, however, quite expensive. In this work, we present a PCR-based method that allows the simultaneous introduction of several mutations in a single step. Using this strategy, 9 of the 10 opal codons of the glpK gene from M. pneumoniae were modified, leading to expression of glycerol kinase in E. coli.

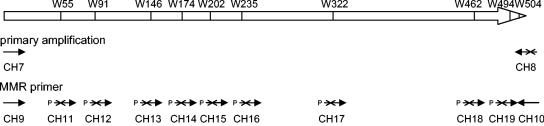

Outline of the multiple-mutation reaction (MMR) strategy.

Several methods for PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis have been developed. Among these, the combined chain reaction method (1, 2) proved to be very rapid and reliable. The principle of this method is the use of mutagenic primers that hybridize more strongly to the template than the external primers. The mutagenic primers are phosphorylated at their 5′ ends, and these are ligated to the 3′ OH groups of the extended upstream primers by the action of a thermostable DNA ligase. Moreover, the DNA polymerase employed must not exhibit 5′ → 3′ exonuclease activity, to prevent the degradation of the extended primers. In our view, Pfu and Pwo polymerases are both well suited (15, 19). The original protocol describes the introduction of two mutations simultaneously. In a previous study, we used a combined chain reaction to mutagenize four distant bases in a DNA fragment in a one-step reaction (our unpublished results).

For the introduction of up to nine mutations in a single experiment, we developed the MMR. This method requires the efficient binding of all the mutagenic primers to the target DNA. To ensure that extension of a PCR product is not possible beyond the next (i.e., more downstream) mutation site without ligation to the corresponding mutagenic primer, special care needs to be taken in primer design. This reaction is based on an accurate calculation of melting temperatures. For this purpose, the formula Tm (melting temperature in °C) = 81.5 + 16.6(log[Me+]) + 0.41 × %G+C − (500/oligonucleotide length) − 0.61 × % formamide was used (16). Only bases that match between primer and template were used for the calculation. One consideration was made when designing the mutagenic primers: ligation was facilitated by placing a G or C at the 5′ end of the oligonucleotide to favor close duplex formation between the primer and the target DNA. The external primers were selected to have melting temperatures considerably lower (about 4°C) than those of the mutagenic primers. The MMR was performed with 2.5 units of Pfu DNA polymerase (MBI Fermentas, Lithuania) and 15 units of Ampligase (Epicentre, Madison, WI) in MMR buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.5], 3 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.4 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, and 0.5 mM NAD+) in a total volume of 50 μl. Conditions for MMR included denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, primer annealing at 57°C for 30 s, and elongation at 65°C for 6 min, for 35 cycles. Initially, the DNA fragment (100 ng) was denatured for 5 min at 95°C. Ten picomoles of each primer was used. The sequences and the arrangements of the oligonucleotides used in this study are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Mutation | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CH7 | AAAAGTCGACATGGATCTAAAACAACAATACATTCTTG | None | 59 |

| CH8 | TATAAAGCTTGTCTTAGTCTAAGCTAGCCCATTTTAG | A1512G | 63 |

| CH9 | AAAAGTCGACATGGATCTAAAACAAC | None | 57 |

| CH10 | TATAAAGCTTGTCTTAGTCTAAGCTAG | None | 59 |

| CH11 | P-GATCCCTTAGAAATTTGGTCAGTCCAATTAG | A165G | 64 |

| CH12 | P-CCATTGTGTTATGGAACAAAGAAAATGGTTTG | A273G | 63 |

| CH13 | P-CACTAAGATTGCTTGGATCTTGGAAAATGTTC | A438G | 64 |

| CH14 | P-CCTGGTTAATTTGGAAACTAACGGGTG | A522G | 64 |

| CH15 | P-CCATGACATGGTCACAAGAGTTAGGC | A606G | 65 |

| CH16 | P-TACCGAGTCATTGGTCTACTAGTGC | A705G | 65 |

| CH17 | P-CCTTAAAGTGGTTAAGGGATAGTCTTAAGG | A966G | 65 |

| CH18 | P-GCAGTTAATTATTGGAAGGACACTAAACAAC | A1386G | 63 |

| CH19 | P-GAAATCAAAGCGTTGGAACGAAGCTG | A1482G | 65 |

The “P” at the 5′ end of oligonucleotide sequences indicates phosphorylation.

FIG. 1.

Strategy for amplification and mutagenesis of the M. pneumoniae glpK gene (MPN050 [6]). The positions of the opal codons in the wild-type glpK gene (indicated by a W followed by the number corresponding to the amino acid) and the position and orientation of the external and mutagenic oligonucleotides are shown. The annealing site of each oligonucleotide is indicated by an arrow. Oligonucleotides bearing an A→G transition are depicted by crossed arrows.

Cloning of M. pneumoniae glpK and expression of the protein in E. coli.

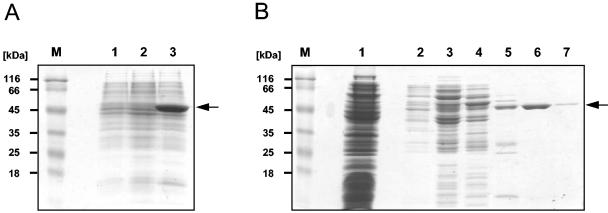

An analysis of growth behavior and the in vivo protein phosphorylation pattern identified glycerol as a key carbon source associated with regulatory phenomena. This substrate triggered in vivo phosphorylation of the HPr protein of the phosphotransferase system by the metabolite-sensitive HPr kinase/phosphorylase (5, 24). We were therefore interested in studying glycerol metabolism and its regulation in more detail. As a first step, we intended to purify the glycerol kinase. This enzyme is known to be a key target of catabolite regulation in gram-positive bacteria (4, 25). However, the corresponding glpK gene contains 10 opal codons and was therefore a good subject for MMR in order to change these codons to tryptophan codons for E. coli. The glpK gene was amplified using the oligonucleotides CH7 and CH8 and chromosomal DNA of M. pneumoniae M129 (ATCC 29342) as a template. With CH8, the most C-terminal opal codon was replaced by a TGG codon. The amplicon was cloned between the SalI and HindIII sites of the expression vector pWH844 (20). The resulting plasmid, pGP253, was used as a template for MMR with CH9 and CH10 as external primers and CH11 through CH19 as mutagenesis primers. Five independent MMRs were carried out, and the MMR products were individually cloned as a SalI/HindIII fragment into pWH844. The inserts of one clone resulting from each MMR were sequenced. Out of the five candidates, three contained the nine desired mutations without any additional mutations. One plasmid contained seven out of nine mutations, and the fifth plasmid bore all nine mutations and one additional undesired 1-bp deletion in one of the primer regions. Plasmids bearing all nine desired mutations but no additional mutations were designated pGP254. pGP254 allows the expression of M. pneumoniae glycerol kinase fused to an N-terminal hexahistidine sequence under the control of an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter. To test the success of the mutagenesis, we compared the protein contents of E. coli cultures carrying either pWH844, pGP253, or pGP254. A prominent band corresponding to an approximate molecular mass of 56 kDa is detectable in the strain bearing pGP254, while no such protein is expressed from pGP253 encoding the unmutated glpK gene (Fig. 2A). The glycerol kinase was purified to apparent homogeneity by Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid chromatography as described previously (Fig. 2B) (15). Thus, MMR was successful in achieving efficient overproduction of M. pneumoniae glycerol kinase for biochemical studies.

FIG. 2.

Overproduction and purification of M. pneumoniae GlpK. (A) Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)- polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the detection of His6-tagged GlpK in crude extracts of E. coli DH5α bearing either the empty expression vector pWH844 (lane 1); the expression vector including the wild-type glpK allele, pGP253 (lane 2); or the vector including the mutated glpK allele, pGP254 (lane 3). Cells were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.8, and expression from the IPTG-inducible promoter was induced by addition of 1 mM IPTG (final concentration). After 2 h, cells were harvested and disrupted by sonication. The insoluble fraction was pelleted in a centrifugation step and solubilized using 6 M urea, and sample aliquots were separated on an SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel. (B) SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to monitor the purification of His6-tagged GlpK. Crude extract of the GlpK expression strain (E. coli DH5α bearing the plasmid pGP254) that had been grown in the presence of 1 mM IPTG was passed over a Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid superflow column (5-ml bed volume; QIAGEN) and washed extensively with a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and 200 mM NaCl, followed by elution with an imidazole gradient (from 10 to 500 mM imidazole). Aliquots of the individual fractions were separated on SDS-12% polyacrylamide gels. A prestained protein molecular mass marker (Fermentas) served as a standard (lane M). Lane 1, flowthrough; lane 2, 10 mM imidazole; lane 3, 20 mM imidazole; lane 4, 50 mM imidazole; lane 5, 100 mM imidazole; lane 6, 200 mM imidazole; lane 7, 500 mM imidazole.

This study demonstrates that MMR can be used for the rapid and highly efficient introduction of multiple mutations into a gene. Out of five individual clones, four had the desired mutations. Of these four, only one candidate contained an extra mutation, which was most probably due to an impure oligonucleotide mix. Indeed, other experiments indicated that the quality of the oligonucleotides is the limiting factor for MMR. Obviously, this method is useful not only for the expression of Mycoplasma species genes, but also to change codon usage patterns or for any other purpose that requires the introduction of many mutations or combinations of mutations at the same time. What is the maximum number of mutations that can be introduced by MMR in a single step? Our results suggest that the target of nine mutations is still far from a theoretical limit, and we are confident that this method can be made even more effective by taking care of the quality of the oligonucleotides (see above) and by using mutagenic primers that alternate between the two strands of the DNA. With this method at hand, even the expression of a functional P1 adhesin gene in E. coli, which has so far been beyond imagination (3), now seems feasible.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Richard Herrmann for the gift of M. pneumoniae chromosomal DNA.

This work was supported by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie. S.H. was supported by a personal grant from the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bi, W., and P. J. Stambrook. 1997. CCR: a rapid and simple approach for mutation detection. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:2949-2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bi, W., and P. J. Stambrook. 1998. Site-directed mutagenesis by combined chain reaction. Anal. Biochem. 256:137-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhry, R., N. Nisar, B. Hora, S. R. Chirasani, and P. Malhotra. 2005. Expression and immunological characterization of the carboxy-terminal region of the P1 adhesin protein of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:321-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darbon, E., P. Servant, S. Poncet, and J. Deutscher. 2002. Antitermination by GlpP, catabolite repression via CcpA and inducer exclusion triggered by P∼GlpK dephosphorylation control Bacillus subtilis glpFK expression. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1039-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halbedel, S., C. Hames, and J. Stülke. 2004. In vivo activity of enzymatic and regulatory components of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 186:7936-7943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Himmelreich, R., H. Hilbert, H. Plagens, E. Pirkl, B.-C. Li, and R. Herrmann. 1996. Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4420-4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutchinson, C. A., III, S. C. Peterson, S. R. Gill, R. T. Cline, O. White, C. M. Fraser, H. O. Smith, and J. C. Venter. 1999. Global transposon mutagenesis and a minimal mycoplasma genome. Science 286:2165-2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inamine, J. M., K.-C. Ho, S. Loechel, and P.-C. Hu. 1990. Evidence that UGA is read as a tryptophan codon rather than as a stop codon by Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Mycoplasma genitalium, and Mycoplasma gallisepticum. J. Bacteriol. 172:504-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs, E. 1997. Mycoplasma infections of the human respiratory tract. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 109:574-577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaffe, J. D., H. C. Berg, and G. M. Church. 2004. Proteogenomic mapping as a complementary method to perform genome annotation. Proteomics 4:59-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeffery, C. J. 1999. Moonlighting proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:8-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kannan, T. R., and J. B. Baseman. 2000. Expression of UGA-containing Mycoplasma genes in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 182:2664-2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knudtson, K. L., M. Manohar, D. E. Joyner, E. A. Ahmed, and B. C. Cole. 1997. Expression of the superantigen Mycoplasma arthritidis mitogen in Escherichia coli and characterization of the recombinant protein. Infect. Immun. 65:4965-4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lind, K. 1983. Manifestations and complications of Mycoplasma pneumoniae disease: a review. Yale J. Biol. Med. 56:461-468. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meinken, C., H.-M. Blencke, H. Ludwig, and J. Stülke. 2003. Expression of the glycolytic gapA operon in Bacillus subtilis: differential syntheses of proteins encoded by the operon. Microbiology 149:751-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meinkoth, J., and G. Wahl. 1984. Hybridization of nucleic acids immobilized on solid supports. Anal. Biochem. 138:267-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noh, E. J., S. W. Kang, Y. J. Shin, D. C. Kim, I. S. Park, M. Y. Kim, B. G. Chun, and B. H. Min. 2002. Characterization of Mycoplasma arginine deiminase expressed in E. coli and its inhibitory regulation of nitric oxide synthesis. Mol. Cells 13:137-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollack, J. D., M. A. Myers, T. Dandekar, and R. Herrmann. 2002. Suspected utility of enzymes with multiple activities in the small genome Mycoplasma species: the replacement of the missing “household” nucleoside diphosphate kinase gene and activity by glycolytic kinases. OMICS 6:247-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schilling, O., I. Langbein, M. Müller, M. Schmalisch, and J. Stülke. 2004. A protein-dependent riboswitch controlling ptsGHI operon expression in Bacillus subtilis: RNA structure rather than sequence provides interaction specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:2853-2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schirmer, F., S. Ehrt, and W. Hillen. 1997. Expression, inducer spectrum, domain structure, and function of MopR, the regulator of phenol degradation in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus NCIB8250. J. Bacteriol. 179:1329-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simoneau, P., C.-M. Li, S. Loechel, R. Wenzel, R. Herrmann, and P.-C. Hu. 1993. Codon reading scheme in Mycoplasma pneumoniae revealed by the analysis of the complete set of tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:4967-4974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smiley, B. K., and F. C. Minion. 1993. Enhanced readthrough of opal (UGA) stop codons and production of Mycoplasma pneumoniae P1 epitopes in Escherichia coli. Gene 134:33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stamburski, C., J. Renaudin, and J. M. Bove. 1991. First step toward a virus-derived vector for gene cloning and expression in spiroplasmas, organisms which read UGA as a tryptophan codon: synthesis of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in Spiroplasma citri. J. Bacteriol. 173:2225-2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinhauer, K., T. Jepp, W. Hillen, and J. Stülke. 2002. A novel mode of control of Mycoplasma pneumoniae HPr kinase/phosphatase activity reflects its parasitic lifestyle. Microbiology 148:3277-3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stülke, J., and W. Hillen. 2000. Regulation of carbon catabolism in Bacillus species. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:849-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waites, K. B., and D. F. Talkington. 2004. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:697-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wasinger, V. C., J. D. Pollack, and I. Humphery-Smith. 2000. The proteome of Mycoplasma genitalium. Chaps-soluble component. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:1571-1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]