Abstract

Dopamine modulates a wide range of cognitive processes in the prefrontal cortex, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Here, we examined the roles of prefrontal vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)–expressing neurons and their D1 receptors (D1Rs) in working memory using a delayed match-to-sample task in mice. VIP neurons conveyed robust working-memory signals, and their inactivation impaired behavioral performance. Moreover, selective knockdown of D1Rs in VIP neurons also resulted in impaired performance, indicating the critical role of VIP neurons and their D1Rs in supporting working memory. Additionally, we found that dopamine release dynamics during the delay period varied depending on the target location. Furthermore, dopaminergic terminal stimulation induced a contralateral response bias and enhanced neuronal target selectivity in a laterality-dependent manner. These results suggest that prefrontal dopamine modulates behavioral responses and delay-period activity based on laterality. Overall, these findings shed light on dopamine-modulated prefrontal neural processes underlying higher-order cognitive functions.

Prefrontal VIP neurons mediate dopamine’s influence on working memory, with lateralized modulation linked to directional choices.

INTRODUCTION

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays a crucial role in working memory, which allows the retention and manipulation of information in the absence of external sensory cues, a process essential for various higher-order brain functions (1–3). A large body of studies indicates an important role of dopamine in modulating PFC neural processes supporting working memory (4–6). Of multiple subtypes of dopamine receptors, stimulating or blocking D1 receptors (D1Rs) in the PFC impairs working memory (7–11), indicating the importance of D1Rs and optimal dopamine concentration in facilitating working memory. Although PFC dopamine is essential for an array of complex cognitive processes including working memory, it is still unclear how dopamine modulates diverse PFC neural processes.

Of the various types of neurons in the cerebral cortex, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)–expressing neurons are thought to exert powerful influences on cortical circuit operations by modulating other inhibitory neuronal activity (12–15). Previous studies in the PFC have shown that VIP neurons mediate disinhibitory control of pyramidal neurons in aversive signal processing (16, 17) and memory retention (18). Furthermore, given their abundance in D1Rs (19), VIP neurons are likely to play a key role in mediating dopaminergic influences on the PFC. However, the roles of VIP neurons and their D1Rs in higher-order cognitive processes, including working memory, remain largely unknown.

To investigate this, we examined VIP neuronal activity and assessed the behavioral effects of inactivating VIP neurons and lowering their D1R expression in the medial PFC (mPFC) while mice were performing a delayed match-to-sample task. We also examined dopamine release dynamics and VIP neuronal responses to dopaminergic terminal stimulation (DTS) in the mPFC. In addition, for a comprehensive understanding of dopamine actions on prefrontal neural processes, we examined the behavioral effect of lowering pyramidal neuronal D1R expression and pyramidal neuronal responses to DTS. Our results consistently indicate critical roles of VIP neurons and their D1Rs in dopaminergic modulation of working memory. Our results also show lateralized actions of dopamine on delay-period activity. These findings shed light on the intricate interplay between dopamine and prefrontal neural processes governing working memory.

RESULTS

VIP neurons convey working-memory signals

Mice were trained to perform a delayed match-to-sample task under head fixation (20, 21). They were rewarded by choosing the same water lick port that was presented during the sample phase before a delay period (Fig. 1, A and B; see Materials and Methods and movie S1). All mice were trained to perform the task, while the duration of delay was increased from 0.5 to 4 s in a stepwise manner across sessions (0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 s; 120 to 160 trials per session; performance criterion: 0.5 to 3 s, >70% correct choices per session; 4 s, >70% correct choices for two consecutive sessions).

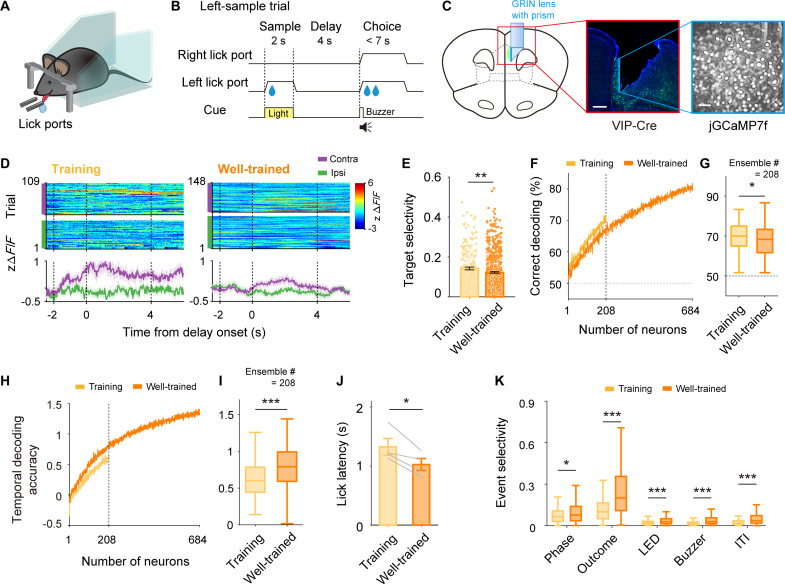

Fig. 1. VIP neurons convey working-memory signals.

(A) Experimental setting. (B) Schematic for the delayed match-to-sample task. (C) Schematic (left) and a coronal brain section (middle) showing the GRIN prism lens position and the spread of jGCaMP7f (green). Right, a sample field of view. Scale bars, 500 μm (middle) and 100 μm (right). (D) Calcium responses of sample VIP neurons during the 4-s training (left) and well-trained (right) stages. zΔF/F, baseline-normalized calcium transient signals (see Materials and Methods); purple and green, contralateral and ipsilateral trials, respectively. (E) Distributions of individual neuronal target selectivity (see Materials and Methods; filled circles, neurons with significant target selectivity). (F) Neural decoding of target as a function of ensemble size. (G) Decoding performance (n = 100 iterations) at ensemble size of 208 neurons [vertical dashed line in (F)]. (H) Temporal decoding accuracy (see Materials and Methods) as a function of ensemble size. (I) Temporal decoding accuracy at an ensemble size of 208 neurons [vertical dashed line in (H)]. (J) Lick latency since choice onset. (K) Event selectivity for trial phase (sample versus choice), outcome (correct versus error), and other task events (LED, buzzer, and ITI). Shading, SEM across trials (D) or 100 decoding iterations [(F) and (H)]. Error bars, SEM across neurons (E) or four mice (J). Box and whisker plots, data across 100 decoding iterations [(G) and (I)] or neurons (K). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, t test.

We first examined working memory–related activity of VIP neurons during the delay period. For this, we monitored VIP neuronal activity during task performance with calcium imaging (Fig. 1C). We unilaterally injected Cre-dependent Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) carrying calcium indicator jGCaMP7f (pGP-AAV1-syn-FLEX-jGCaMP7f-WPRE) into the mPFC of VIP-Cre mice and implanted a Graded Index (GRIN) prism lens targeting layer 2/3 where VIP neurons are mainly located (15) (Fig. 1C; see fig. S1 for histological verification of jGCaMP7f expressions and GRIN prism lens locations). We included in the analysis only those neurons with mean calcium event rates during task performance ≥0.01 Hz.

To examine how working memory–related VIP neuronal activity changes in the course of task learning, we analyzed delay-period activity of VIP neurons during training as well as well-trained stages. For a consistent comparison of neural activity across the same delay interval, we compared VIP neuronal activity during the first 4-s delay training session (training stage, 72.4 ± 8.6% correct choices) to that during the session with the largest number of recorded VIP neurons among 2 to 5 sessions after reaching the performance criterion (well-trained stage, 84.5 ± 9.4% correct choices). We found many VIP neurons showing target-dependent delay-period activity in the training as well as well-trained stages (examples shown in Fig. 1D; raw ΔF/F traces shown in fig. S2). Unexpectedly, delay-period target signals were stronger during the training than well-trained stage as assessed by a target selectivity index (see Materials and Methods; unpaired t test, t890 = 2.669, P = 0.008; Fig. 1E) and neural decoding of target (ensemble size, n = 208 neurons; t99 = 2.350, P = 0.021; Fig. 1, F and G) calculated using the entire delay-period (4 s) activity. These results indicate that VIP neurons convey working-memory signals and that their strengths do not increase monotonically in the course of training.

VIP neurons convey diverse task-related signals

We also compared VIP neuronal activity related to other task-related variables between the training and well-trained stages. VIP neurons conveyed more precise temporal information about the elapse of delay in the well-trained than training stage (temporal decoding accuracy; unpaired t test, t198 = −4.128, P = 5.4 × 10−5; Fig. 1, H and I), which is in line with a shorter reaction time in the choice phase in the well-trained than training stage (lick latency; t3 = 4.536, P = 0.020; Fig. 1J). To examine VIP neuronal activity related to various task events, we calculated an event selectivity index as a measure for the magnitude of neuronal response to a given task event (see Materials and Methods). We compared neuronal activity between sample and choice phases (phase; 1-s time windows from sample onset and delay offset, respectively), correct and error trials during the choice phase (outcome; 1-s time window from delay offset), and before (0.5 s) and after (0.5 s) light-emitting diode (LED), buzzer, and intertrial interval (ITI) onset (see Materials and Methods). The event selectivity was significantly higher in the well-trained than training stage for all tested task events (unpaired t test, phase, t890 = −2.578, P = 0.010; outcome, t890 = −6.171, P = 1.0 × 10−9; LED, t890 = −6.692, P = 3.9 × 10−11; buzzer, t890 = −7.616, P = 6.7 × 10−14; ITI, t890 = −3.939, P = 8.8 × 10−5; Fig. 1K). These results indicate that VIP neurons convey more precise temporal information and stronger task-related signals in the well-trained than training stage. Together with the unexpected finding that working-memory signals are stronger during the 4-s training than well-trained stage, these results suggest that well-trained animals might allocate mPFC’s neural resources more toward processes other than the maintenance of target information, such as keeping track of the elapse of delay and preparing for upcoming actions. The mPFC may opt to avoid representing an excessive level of working memory when it has the option to do so, allowing it to devote its remaining resources to other psychological processes.

VIP neuronal inactivation impairs behavioral performance

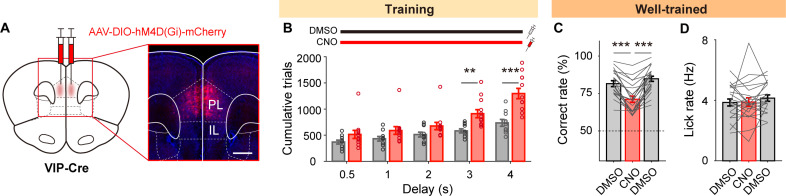

We then examined the effect of VIP neuronal inactivation on behavioral performance in a separate group of mice. For this, we used designer receptor exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD)–mediated chemogenetic inactivation. We bilaterally injected Cre-dependent hM4D(Gi)-mCherry into the mPFC of VIP-Cre mice (Fig. 2A) and, 4 to 6 weeks later, trained them with daily systemic injections (intraperitoneally) of clozapine N-oxide (CNO; 12 mice) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; 10 mice), while the duration of delay was increased from 0.5 to 4 s across sessions. Chemogenetic inactivation of VIP neurons had no significant effect on the number of trials to reach the performance criterion when the delay duration was 2 s or shorter. However, it significantly increased this number when the delay duration exceeded 2 s [cumulative trials, two-way mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA), main effect of drug, F(1,20) = 10.058, P = 0.005; delay, F(4,80) = 72.268, P = 8.9 × 10−26; drug × delay, F(4,80) = 11.027, P = 3.6 × 10−7; Bonferroni post hoc test for time, CNO versus DMSO, 0.5 s, P = 0.122, 1 s, P = 0.097, 2 s, P = 0.078, 3 s, P = 0.002, 4 s, P = 2.1 × 10−4; Fig. 2B], without increasing miss (no-choice) trials (fig. S3). These results indicate the involvement of VIP neurons in task learning when delay is sufficiently long (>2 s).

Fig. 2. VIP neuronal inactivation impairs behavioral performance.

(A) Schematic (left) and a coronal brain section (right) showing the spread of hM4D(Gi)-mCherry (red). Scale bar, 500 μm. (B) Cumulative trials over training sessions for DMSO and CNO injection groups. (C) Fraction of correct trials in the well-trained stage. (D) Lick rate during the choice period (2 s). Circles and lines, individual animal data. Bar graphs and error bars, mean and SEM across mice. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Bonferroni post hoc test following two-way mixed (B) or one-way repeated-measures (C) ANOVA.

To obtain insights on why VIP neuronal inactivation impairs task learning only when the delay is longer than 2 s, we examined temporal dynamics of target-related VIP and pyramidal neuronal delay-period activity. A cross-temporal decoding analysis revealed that VIP and pyramidal neurons persistently maintain sample-related sensory responses about 2 s since delay onset even in error trials (fig. S4). Similar results were obtained with the analysis of pyramidal neuronal delay-period activity in our previous study (21). These results suggest that the mPFC neural network can sustain sensory signals faithfully about 2 s since delay onset regardless of behavioral performance (correct versus error), which is consistent with the finding that PFC neural activity decays more slowly than sensory cortical neural activity (22, 23). Together, our results suggest that VIP neuronal inactivation does not prevent the animal from learning the task rule (delayed match to sample) per se but impairs learning only when delay duration was sufficiently long (>2 s) and there is a demand for working memory beyond sustaining initial sensory responses.

We also tested the effect of inactivating VIP neurons in well-trained animals. After training both animal groups until the 4-s delay performance criterion (5.9 ± 1.4 and 10.41 ± 2.4 sessions for DMSO and CNO groups, respectively; mean ± SD), we tested each animal with alternate injections of CNO and DMSO (total 22 mice). Chemogenetic inactivation of VIP neurons significantly decreased behavioral performance [% correct, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA, F(2,42) = 45.665, P = 2.9 × 10−11; Bonferroni post hoc test, first DMSO versus CNO, P = 3.6 × 10−6, CNO versus second DMSO, P = 2.1 × 10−8, first DMSO versus second DMSO, P = 0.108; Fig. 2C] without altering overall lick rate [F(2,42) = 0.939, P = 0.399; Fig. 2D]. This finding further indicates the involvement of VIP neurons in mPFC neural processes supporting working memory.

VIP neuronal D1R knockdown impairs behavioral performance

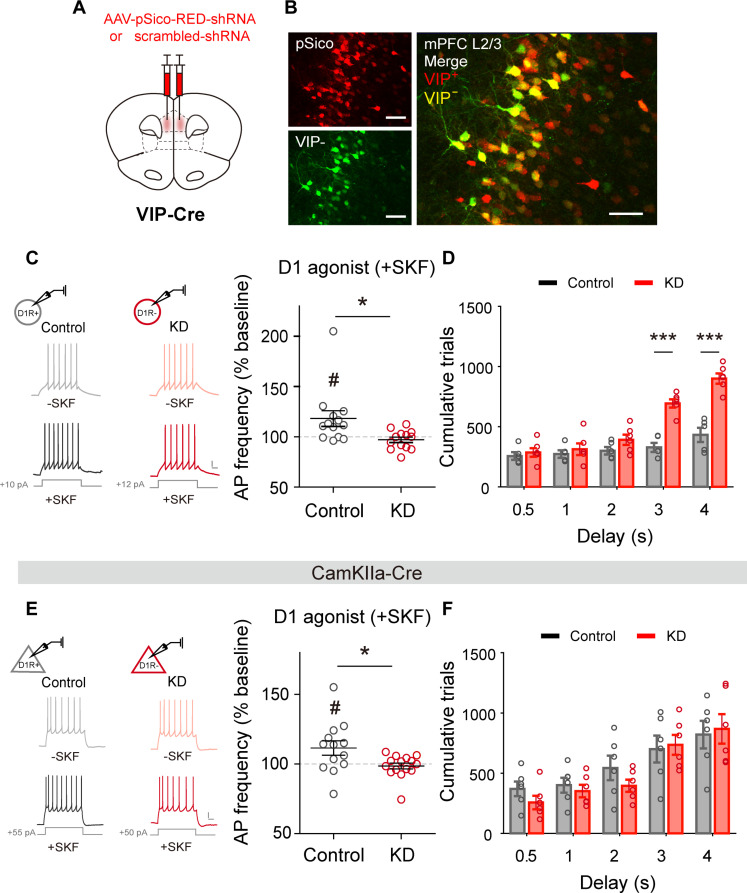

Next, we investigated the involvement of VIP neuronal D1Rs (VIPD1R) in working memory. We first confirmed the previous finding that the infusion of a D1R antagonist into the PFC impairs working memory (fig. S5). We then selectively lowered VIPD1R expression by injecting Cre-dependent pSico-RED-shRNA (short hairpin RNA) into the mPFC of VIP-Cre mice bilaterally at least 8 weeks before behavioral training [D1R-knockdown (KD) group, n = 8; Fig. 3, A and B]. In control mice (n = 8), Cre-dependent pSico–RED–scrambled shRNA was injected into the mPFC. We examined the effect of a D1R agonist, SKF-81297, on VIP neuronal activity with whole-cell patch clamp recordings in ex vivo mPFC slices (one D1R-KD mouse after completing behavioral testing and three control and two D1R-KD mice without behavioral testing). SKF-81297 (10 μM) elevated VIP neuronal action potential (AP) frequency significantly in the control (13 neurons from three mice; paired t test, t12 = 2.318, P = 0.039) but not D1R-KD group (13 neurons from three mice; t12 = 1.135, P = 0.279), and the amount of SKF-81297–induced change in AP frequency (ΔAP) was significantly greater in the control than the KD group (unpaired t test, t24 = 2.788, P = 0.012; Fig. 3C). These results indicate successful KD of mPFC VIPD1R in mice injected with pSico-RED-shRNA.

Fig. 3. VIP neuronal D1R-KD impairs behavioral performance.

(A) Schematic for bilateral AAV-pSico-RED-shRNA or scrambled shRNA injections in VIP-Cre mice. (B) Sample brain sections showing pSico+ (left upper: red, all neurons) and VIP− (left bottom: green, Cre-negative) neurons (right, merged image). Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Effect of SKF-81297 on AP frequency in ex vivo mPFC slices. Left, sample membrane potential traces with (+SKF) or without (−SKF) SKF-81297 treatment. Right, normalized (% baseline) AP frequency following SKF-81297 treatment in control (scrambled shRNA) and VIPD1R-KD groups. Scale bar, 10 mV and 100 ms. #P < 0.05 (difference from 100%), *P < 0.05 (difference between control and KD), t test. (D) Cumulative trials over training sessions in control and VIPD1R-KD groups. The same format as in Fig. 2B. (E and F) Results from CamKIIa-Cre mice. The same format as in (C) and (D).

Because D1R-KD is an irreversible process and it takes a long time to knock down D1Rs, we could examine the effect of VIPD1R-KD in naïve but not well-trained mice. VIPD1R-KD mice (n = 6) eventually learned to perform the task with extended training. However, as in VIP neuronal inactivation, it took significantly longer for them than the control mice (n = 5) to reach the performance criterion, and significant differences were found between the two animal groups only when the delay was 3 s or longer [cumulative trials, two-way mixed ANOVA, main effect of drug, F(1,9) = 17.861, P = 0.002; delay, F(4,36) = 78.609, P = 2.8 × 10−17; drug × delay, F(4,36) = 28.925, P = 8.4 × 10−11; Bonferroni post hoc test, KD versus control, 0.5 s, P = 0.555, 1 s, P = 0.525, 2 s, P = 0.134, 3 s, P = 5.1 × 10−5, and 4 s, P = 1.1 × 10−4; Fig. 3D; see also fig. S3]. Thus, as in VIP neuronal inactivation, VIPD1R-KD did not prevent the animals from learning the task rule per se but impaired performance only when delay duration was sufficiently long (>2 s).

There remains a possibility that VIP neuronal D1Rs are involved in learning to use working memory to guide behavior at delay offset, rather than being involved in working memory itself. However, we trained both groups (control and KD) until they met the performance criterion for each stage of delay duration (0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 s). Thus, after the 3-s delay stage, it is likely that both groups had learned to use working memory to guide choice behavior at comparable levels. Nonetheless, the D1R-KD group performed significantly worse than the control group in 4-s delay sessions, requiring more trials to reach the criterion [noncumulative trials, two-way mixed ANOVA, main effect of drug, F(1,9) = 42.829, P = 1.1 × 10−4; Bonferroni post hoc test, KD versus control, 4 s, P = 0.032; fig. S6]. Collectively, these results suggest the importance of VIPD1R in mediating dopaminergic modulation of working memory.

Since pyramidal neurons, which are the major carrier of mPFC output signals, also express D1Rs, we examined the effect of pyramidal neuronal D1R (PYRD1R)–KD on behavioral performance. For this, we injected Cre-dependent pSico-RED-shRNA (KD group; n = 10 mice) or pSico–RED–scrambled shRNA (control group; n = 10) into the mPFC of CamKIIa-Cre mice bilaterally at least 8 weeks before behavioral testing. We conducted whole-cell patch clamp recordings in ex vivo slice preparations and confirmed that SKF-81297 treatment increased AP frequency in the control but not the D1R-KD group (control, 13 neurons from four mice, paired t test, t12 = 2.229, P = 0.046; PYRD1R-KD, 15 neurons from four mice; t14 = 0.067, P = 0.513; control versus KD, unpaired t test, t26 = 2.561, P = 0.017; Fig. 3E), which indicates successful KD of PYRD1R. We trained these mice in the same manner as we trained the VIP-Cre mice, and found no significant difference between the KD (n = 6) and control (n = 6) groups in the number of trials to reach the performance criterion in any of the training stages [cumulative trials, two-way mixed ANOVA, main effect of drug, F(1,10) = 0.217, P = 0.651; delay, F(4,40) = 32.258, P = 4.9 × 10−12; drug × delay, F(4,40) = 1.179, P = 0.335; Fig. 3F; see also fig. S3]. The performance of the control group in this experiment improved more slowly than that of the control groups in other experiments, suggesting that variations in genetic background might influence baseline performance and learning rate. With this caveat, the findings suggest a greater impact of D1R-KD in VIP neurons compared to pyramidal neurons on prefrontal working memory.

Delay-period dopamine release is higher in contralateral- than ipsilateral-target trials

To investigate how dopamine modulates working memory–related VIP neuronal activity, we examined dopamine release dynamics and physiological effects of DTS. For the former, we monitored the level of mPFC dopamine using the genetically encoded dopamine sensor GRAB-DA (24). We injected green fluorescent gDA3m virus into the mPFC of VIP-Cre mice and implanted a GRIN prism lens targeting layer 2/3 of the mPFC where VIP neurons are mainly located (Fig. 4A) (25). Again, we trained the mice while the duration of delay was increased from 0.5 to 4 s across sessions, and compared delay-period dopamine dynamics during the first 4-s delay training session with that during the well-trained stage.

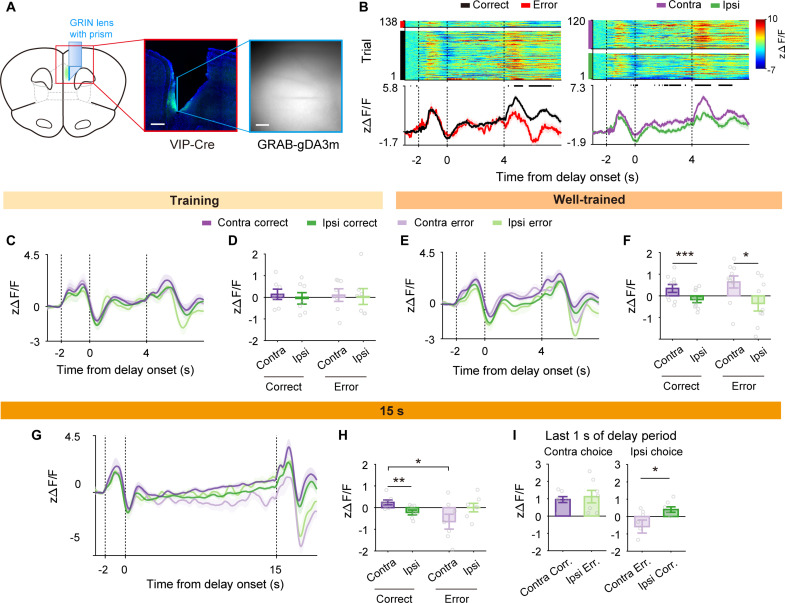

Fig. 4. Delay-period dopamine release is higher in contralateral- than ipsilateral-target trials.

(A) Schematic (left) and a coronal brain section (middle) showing the GRIN prism lens position and the spread of GRAB-gDA3m (green) in the mPFC. Right, a sample field of view. Scale bars, 500 μm (middle) and 100 μm (right). (B) Dopamine release dynamics during a sample session (well-trained stage). Trials are divided by correct versus error (left) or contralateral (Contra)– versus ipsilateral (Ipsi)–target trials (right). (C) Group data showing dopamine dynamics during contralateral-correct, ipsilateral-correct, contralateral-error, and ipsilateral-error trials during the 4-s training stage (contralateral trials, purple; ipsilateral trials, green; correct trials, saturated colors; error trials, soft colors). (D) Mean dopamine levels during the 4-s delay period sorted by trial types. (E and F) Dopamine dynamics in the well-trained stage. The same format as in (C) and (D). (G and H) Dopamine dynamics during 15-s delay sessions. The same format as in (C) and (D). (I) Mean dopamine signals during the last 1 s of the 15-s delay period. Shading and error bars, SEM across trials (B) or mice [(C) to (I)]. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Bonferroni post hoc test following two-way repeated-measures ANOVA [(F) and (H)] or t test (I).

As expected, dopamine release was higher in response to reward delivery (correct trials) than reward omission (error trials; Fig. 4B, left) in both the training and well-trained stages. We found that delay-period dopamine release differed significantly between contralateral- and ipsilateral-target trials in both correct and error trials in the well-trained stage [two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, main effect of performance, F(1,8) = 0.832, P = 0.388; direction, F(1,8) = 23.599, P = 0.001; performance × direction, F(1,8) = 1.732, P = 0.225; Bonferroni post hoc test for direction, contralateral correct versus ipsilateral correct, P = 5.6 × 10−4; contralateral error versus ipsilateral error, P = 0.015; Fig. 4B, right, E, and F], but not in the 4-s training stage [main effect of performance, F(1,6) = 0.040, P = 0.848; main effect of direction, F(1,6) = 0.450, P = 0.527; performance × direction, F(1,6) = 0.027, P = 0.681; Fig. 4, C and D; raw ΔF/F traces shown in fig. S2]. In addition, we found that delay-period dopamine concentration showed ramping activity in the well-trained but not training stage. Following a phasic dopamine release (an increase then a decrease) lasting ~4 s since sample onset, dopamine concentration increased gradually throughout the rest of the delay period in both correct and error trials in the well-trained but not training stage, and the slope was significantly greater in the well-trained than training stage (fig. S7, A to C). This is consistent with the finding that ventral tegmental area (VTA) neurons show ramping activity during the delay period in monkeys (26), which could be related to motivational variation or the proximity to reward (27, 28).

Dopamine release during 15-s delay is correlated with behavioral performance

That delay-period dopamine levels are similar between correct and error trials is unexpected given that both pharmacological D1R blockade and VIPD1R-KD impaired working memory. To further explore this matter, we examined dopamine release during a longer delay period (15 s). We reasoned that performance-correlated delay-period dopamine dynamics might be revealed under a more working memory–demanding situation, which is supported by our previous findings that optogenetic inactivation of somatostatin (SST)–expressing or intratelencephalic (IT) projection neurons impairs working memory when the length of delay is ≥10 s, but not when it is ≤5 s (21, 29). We further trained the gDA3m-expressing animals with 15-s delay to the performance criterion (>70% correct choices) and examined delay-period dopamine dynamics in the same manner. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between performance (correct versus error) and target direction [contralateral versus ipsilateral; main effect of performance, F(1,6) = 3.201, P = 0.124; direction, F(1,6) = 0.260, P = 0.628; performance × direction, F(1,6) = 10.753, P = 0.017] so that delay-period dopamine release is higher in correct than error trials in contralateral-target (Bonferroni post hoc test, P = 0.025) but not ipsilateral-target trials (P = 0.292; Fig. 4, G and H). In addition, dopamine concentration during the 15-s delay period showed significant ramping activity in correct but not error trials (difference of ramping slope from zero, paired t test, correct trials, t6 = 3.536, P = 0.012, error trials, t6 = 2.107, P = 0.080; Fig. 4G and fig. S7, D and E), and the slope was significantly higher in correct than error trials (paired t test, correct versus error trials, t6 = 3.536, P = 0.012; fig. S7E). These results show performance-correlated dopamine release dynamics at 15-s delay. Also, a significant interaction between performance and target direction argues against the possibility that delay-period dopamine release is solely related to an upcoming motor action irrespective of working memory.

To further explore potential motor preparation–related dopamine release, we compared dopamine concentration during the last 1 s of the delay period across different trial types. Dopamine concentration did not differ significantly between contralateral-correct and ipsilateral-error trials (correct and false contralateral choices, respectively; paired t test, t6 = −0.724, P = 0.497), but was significantly higher in ipsilateral-correct than contralateral-error trials (correct and false ipsilateral choices, respectively; t6 = −3.072, P = 0.022; Fig. 4I). This pattern of dopamine release cannot be fully explained by the role of dopamine in controlling the upcoming action irrespective of working memory.

DTS induces contralateral choice bias

Next, we examined the effect of DTS on delay-period VIP neuronal activity and, to examine general dopaminergic influences on PFC neural network, we also examined its effect on delay-period pyramidal neuronal activity. Because delay-period dopamine level differed between correct and error trials at 15-s but not 4-s delay, we examined the DTS effect using both 4-s and 15-s delay periods in well-trained mice (see Materials and Methods for experimental details; Fig. 5, A and D). For this, we unilaterally injected Cre-dependent jGCaMP7f virus (n = 5) or CaMKII-dependent GCaMP6f virus (n = 5) to target VIP or pyramidal neurons, respectively, in the mPFC of VIP-Cre × DAT-Cre mice. We also injected Cre-dependent ChrimsonR bilaterally to target dopaminergic neurons in the VTA. After training the mice to the criterion (initially up to 4-s delay and then with 15-s delay), we optogenetically stimulated VTA terminals in the mPFC at 20 Hz, emulating phasic activity of dopaminergic neurons known to activate D1Rs (30), in randomly selected 30% of trials. Optogenetic stimulation was given during the entire 4-s delay period and only during the second half of the 15-s delay period (7.5 s). At the same time, we monitored VIP or pyramidal neuronal activity in the mPFC with calcium imaging (see Materials and Methods).

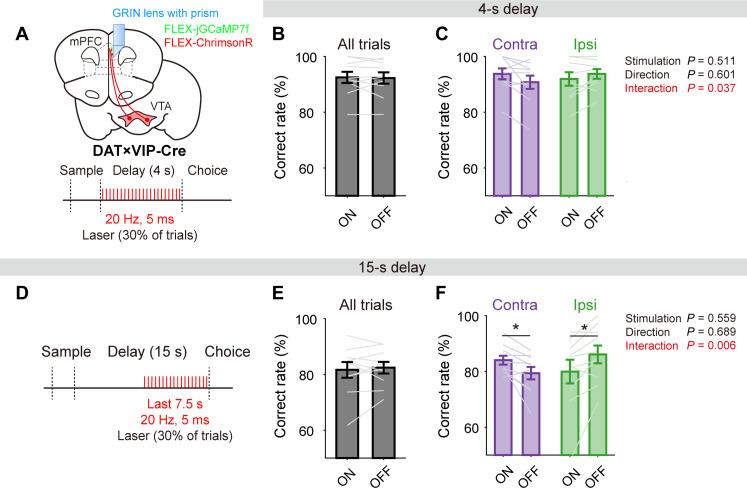

Fig. 5. DTS induces contralateral choice bias.

(A) Schematic showing FLEX-GCaMP7f injection and GRIN lens implantation in the mPFC and FLEX-ChrimsonR injection in the VTA in DAT × VIP-Cre mice. Light stimulation (red tick marks, 20 Hz, 5 ms) was given during the delay period in 30% of trials. (B and C) Behavioral performance in DTS-on and DTS-off trials during 4-s delay sessions, with contralateral (Contra)– and ipsilateral (Ipsi)–target trials shown together (B) or separately (C). In (C), P values are indicated on the right for the main effects of two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (red, P < 0.05). (D to F) Effects of DTS on behavioral performance during 15-s delay sessions. Light stimulation was given during the second half of 15-s delay period in 30% of trials. The same format as in (A) to (C). *P < 0.05, Bonferroni post hoc test following two-way repeated-measures ANOVA.

We first confirmed that DTS elevates mPFC dopamine release in a separate group of mice (n = 3; fig. S8). We assessed the effect of DTS on behavior by combining the data obtained from VIP neuron-targeting (n = 5) and pyramidal neuron-targeting (n = 5) mice to increase statistical power. In 4-s delay sessions, behavioral performance (% correct choices) was similar between DTS-on and DTS-off trials (paired t test, t9 = 0.253, P = 0.806; Fig. 5B). However, the DTS effect differed between contralateral- and ipsilateral-target trials. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between stimulation (DTS-on versus DTS-off) and target direction [contralateral versus ipsilateral; main effect of stimulation, F(1,9) = 0.467, P = 0.511; direction, F(1,9) = 0.294, P = 0.601; stimulation × direction, F(1,9) = 5.993, P = 0.037], despite no significant DTS effect when the two trial types were examined separately (Bonferroni post hoc test, DTS-on versus DTS-off, contralateral trials, P = 0.074; ipsilateral trials, P = 0.137; Fig. 5C). Similarly, in 15-s delay sessions, DTS had no significant effect on overall behavioral performance (% correct choices, paired t test, t9 = −0.542, P = 0.601; Fig. 5E), but significantly increased behavioral performance in contralateral-target trials while decreasing it in ipsilateral-target trials [two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, main effect of stimulation, F(1,9) = 0.367, P = 0.559; direction, F(1,9) = 0.170, P = 0.689; stimulation × direction, F(1,9) = 12.888, P = 0.006; Bonferroni post hoc test, DTS-on versus DTS-off, contralateral trials, P = 0.023; ipsilateral trials, P = 0.019; Fig. 5F]. Unlike behavioral performance, DTS induced no significant changes in lick behavior during the choice period (fig. S9). These results indicate that unilateral DTS induces a contralateral choice bias at both 4-s and 15-s delays.

DTS enhances working-memory signals

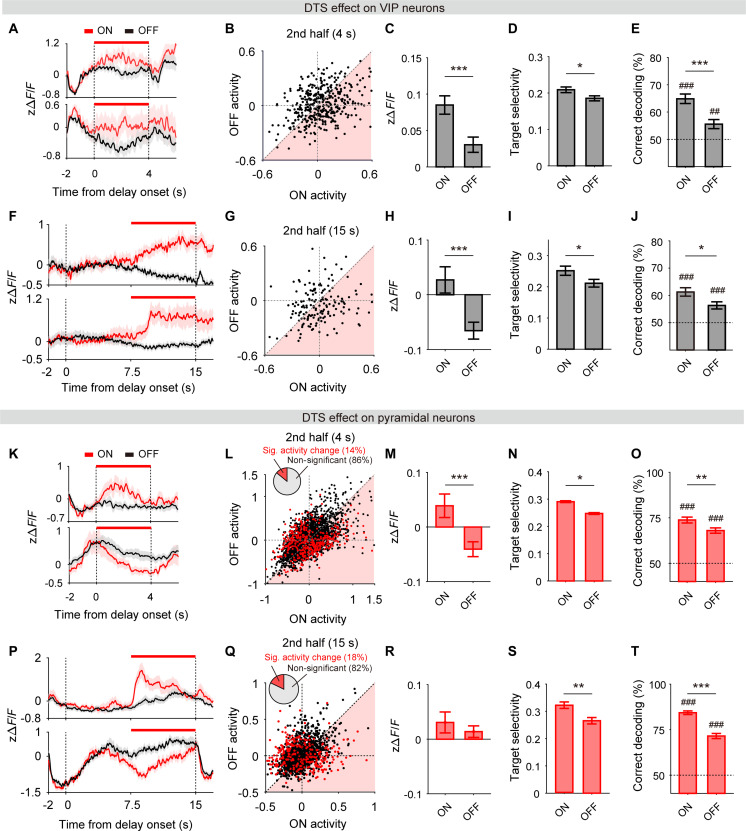

We then examined physiological effects of DTS. For this, we randomly selected the half of nonstimulation trials and compared with the stimulation trials (see Materials and Methods). At 4-s delay, DTS significantly elevated VIP neuronal activity (paired t test, t426 = 4.240, P = 2.7 × 10−5; fig. S10, A and B) but induced no significant change in target selectivity (paired t test, t426 = 0.239, P = 0.812; fig. S10C) or neural decoding of target (ensemble size, 150 neurons, 100 decoding iterations; unpaired t test, t198 = −0.777, P = 0.438; fig. S10D). However, when we repeated the same analysis excluding the early delay period (initial 2 s) during which sensory responses are strong, DTS significantly increased VIP neuronal activity (paired t test, t426 = 4.337, P = 1.8 × 10−5; Fig. 6, A to C), target selectivity (paired t test, t426 = 2.328, P = 0.020; Fig. 6D), and neural target decoding (ensemble size, 150 neurons, 100 decoding iterations; unpaired t test, t198 = 3.871, P = 1.5 × 10−4; Fig. 6E). During the second half of 15-s delay, DTS significantly elevated VIP neuronal activity (paired t test, t173 = 4.635, P = 7.0 × 10−6; Fig. 6, F to H), target selectivity (paired t test, t173 = 2.078, P = 0.039; Fig. 6I), and neural target decoding (ensemble size, 150 neurons, 100 decoding iterations; unpaired t test, t198 = 2.430, P = 0.016; Fig. 6J). These results indicate that DTS increases VIP neuronal delay-period activity and its target selectivity.

Fig. 6. DTS enhances working-memory signals.

(A) Activity of sample VIP neurons during DTS-on (red) and DTS-off (black) trials in a 4-s delay session. Red horizontal lines denote DTS. (B) Scatterplot showing mean VIP neuronal activity during the second half of 4-s delay period in DTS-on (abscissa) and DTS-off (ordinate) trials (n = 427 neurons). (C to E) Mean normalized activity (C), mean target selectivity (D), and target decoding rate (ensemble size, 150 neurons) in DTS-on and DTS-off trials (E). (F to J) Results from 15-s delay sessions (n = 174 neurons). The same format as in (A) to (E). (K to T) Results from the analysis of pyramidal neuronal activity. The same format as in (A) to (J) except that only DTS-responsive neurons (red circles in scatterplots, 4-s delay, 438 of 3105; 15-s delay, 282 of 1579) were analyzed. Shading, SEM across trials. Bar graphs and error bars, mean and SEM across decoding iterations [(E), (J), (O), and (T)] or neurons (the rest). ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 (significant difference from chance), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (DTS-on versus DTS-off), t test.

Consistent but somewhat different results were obtained with the analysis of pyramidal neuronal activity. At 4-s delay, DTS induced both enhancement and reduction in individual pyramidal neuronal activity (fig. S11, A, B, E, and F) and, on average, had no significant effect on it or target selectivity regardless of the entire delay period or its second half was analyzed (figs. S10, E to G, and S12, A to D). However, when we analyzed only those pyramidal neurons whose activity was significantly modulated by DTS (DTS-responsive neurons; n = 438 of 3105, 14%; Fig. 6, K and L; see fig. S11, C, D, G, and H, and Materials and Methods for further details), DTS significantly elevated their mean activity (paired t test, t437 = 3.858, P = 1.3 × 10−4; Fig. 6M), target selectivity (paired t test, t437 = 3.294, P = 0.001; Fig. 6N), and neural target decoding during the last 2 s of the delay period (ensemble size, 150 neurons, 100 decoding iterations; unpaired t test, t198 = 2.650, P = 0.009; Fig. 6O; similar results were obtained with the analysis of the entire 4-s delay; see fig. S10, H to J). Similarly, during the second half of the 15-s delay period, DTS induced both enhancement and reduction in individual pyramidal neuronal activity with no significant effect on their mean value or target selectivity (figs. S11, I and J, and S12, E to H). However, DTS-responsive pyramidal neurons (n = 282 of 1579, 18%; Fig. 6, P and Q; see fig. S11, K and L, for further details) showed enhanced target selectivity (paired t test, t281 = 3.098, P = 0.002; Fig. 6S) and target decoding (ensemble size, 150 neurons, 100 decoding iterations; unpaired t test, t198 = 7.520, P = 1.9 × 10−12; Fig. 6T) in response to DTS, although mean population activity did not change significantly (Fig. 6R). Collectively, these results suggest that DTS increases delay-period target selectivity of both VIP and pyramidal neurons and that this effect is stronger on VIP than pyramidal neurons (direct comparison in fig. S13).

DTS modulates delay-period activity in a laterality-dependent manner

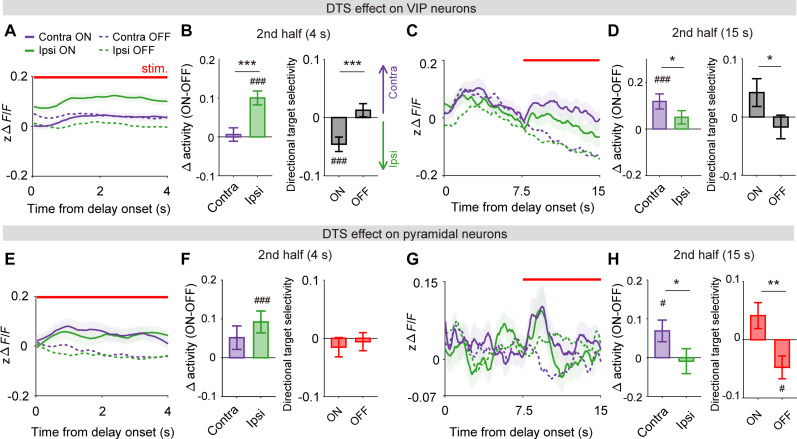

Because dopamine release differed between contralateral- and ipsilateral-target trials, we further examined a potential laterality of the DTS effect by estimating a directional target selectivity index (see Materials and Methods; positive and negative values indicate higher neural activity in contralateral- and ipsilateral-target trials, respectively). When we examined the laterality of delay-period activity in the absence of optogenetic stimulation, VIP neurons showed a tendency to favor the contralateral target at the 4-s delay, while pyramidal neurons displayed a preference for the ipsilateral target at the 15-s delay (fig. S14). In VIP neurons, DTS significantly enhanced ipsilateral but not contralateral target–related activity (Δactivity, paired t test, difference from zero, ipsilateral-target trials, t426 = 5.624, P = 3.4 × 10−8; contralateral-target trials, t426 = 0.346, P = 0.730; contralateral versus ipsilateral, t426 = −4.000, P = 7.5 × 10−5; Fig. 7, A and B, left) during the second half of the 4-s delay period, biasing delay-period activity toward the ipsilateral target compared to no-DTS trials (directional target selectivity, paired t test, t426 = −3.611, P = 3.4 × 10−4; Fig. 7B, right). In contrast, DTS significantly enhanced contralateral- but not ipsilateral-target related activity during the second half of the 15-s delay period (Δactivity, difference from zero, contralateral-target trials, t173 = 3.632, P = 3.7 × 10−4; ipsilateral-target trials, t173 = 1.751, P = 0.082; contralateral versus ipsilateral, t173 = 2.000, P = 0.047; Fig. 7, C and D, left), biasing delay-period activity toward the contralateral target compared to no-DTS trials (directional target selectivity, t173 = 1.985, P = 0.049; Fig. 7D, right; results from error-trial analysis shown in fig. S15).

Fig. 7. Laterality of DTS effect.

(A) Delay-period activity of VIP neuronal population (n = 427 neurons) in four trial types grouped by DTS (on and off) and target location (contralateral and ipsilateral). (B) Left: Difference in VIP neuronal activity between DTS-on and DTS-off trials during the second half of 4-s delay period for contralateral- and ipsilateral-target trials. Right: Directional target selectivity (see Materials and Methods) in DTS-on and DTS-off trials. (C and D) Results from 15-s delay sessions (n = 174 neurons). The same format as in (A) and (B). (E to H) Results from the analysis of pyramidal neuronal activity. The same format as in (A) to (D) except that only DTS-responsive neurons (4-s delay, 438 of 3105; 15-s delay, 282 of 1579) were analyzed. Shading and error bars, SEM across neurons (shading of DTS-off trace omitted for visual clarity). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 (difference from zero), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (contralateral versus ipsilateral or DTS-on versus DTS-off), t test.

When we analyzed all pyramidal neurons, DTS significantly enhanced directional target selectivity, biasing delay-period activity toward the contralateral target in both 4-s and 15-s delay sessions (fig. S16). When we confined our analysis to DTS-responsive pyramidal neurons, DTS significantly enhanced both contralateral and ipsilateral target–related activity (Δactivity, paired t test, difference from zero, contralateral-target trials, t437 = 1.576, P = 0.117; ipsilateral-target trials, t437 = 3.351, P = 8.8 × 10−4; Fig. 7, E and F, left) during the second half of the 4-s delay period, without changing directional target selectivity (paired t test, t437 = −0.947, P = 0.344; Fig. 7F, right). However, similar to VIP neurons, DTS significantly enhanced contralateral target–related activity during the second half of the 15-s delay period (Δactivity, difference from zero, t281 = 2.470, P = 0.014; contralateral versus ipsilateral, t281 = 2.213, P = 0.028; Fig, 7, G and H, left), biasing delay-period activity toward the contralateral target (directional target selectivity, t281 = 2.780, P = 0.006; Fig. 7H, right; results from error-trial analysis shown in fig. S15). These results suggest that dopamine modulates both VIP and pyramidal neuronal delay-period activity in a laterality-dependent manner.

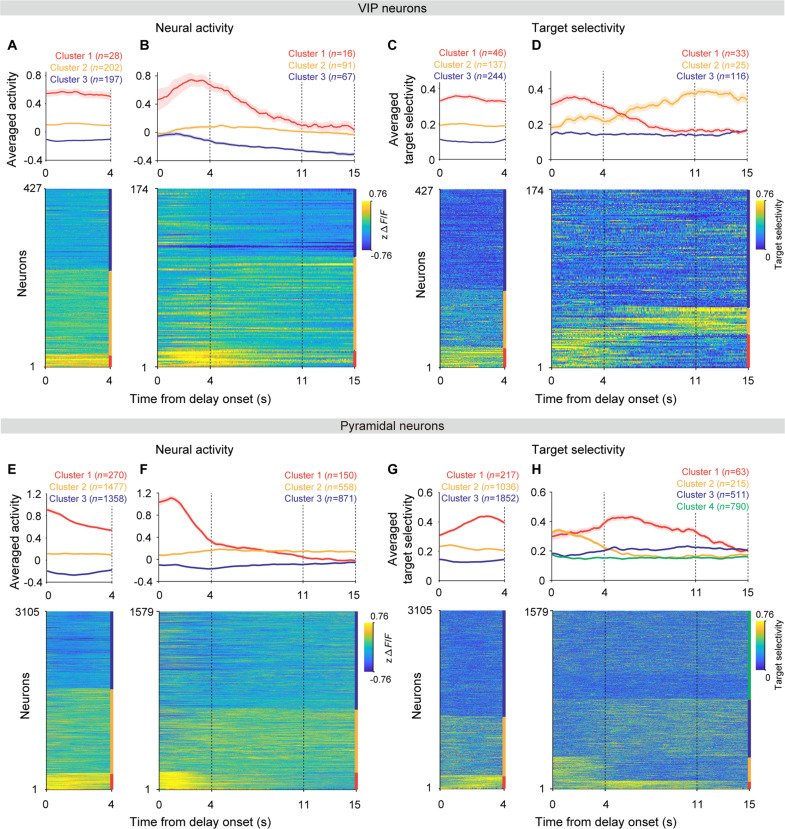

Neural activity dynamics differ between short and long delays

Because dopamine release dynamics correlated with behavioral performance at 15-s delay but not at 4-s delay, and because the DTS effect on directional target selectivity varied between 4-s and 15-s delays, we investigated the possibility that mPFC neural processes supporting working memory differ considerably between short (4 s) and long (15 s) delays. To explore this, we analyzed the delay-period activity dynamics of VIP neurons using trials without optogenetic stimulation (70% of total trials). We classified neurons according to delay-period dynamics using K-means clustering. When we used mean z-score normalized activity in correct trials as an input, the activity dynamics of three clusters were largely static in 4-s delay sessions, but more variable in 15-s delay sessions (Fig. 8, A and B). Similarly, when we classified neurons using target selectivity as an input to examine dynamics of working-memory content, its dynamics were largely static in 4-s delay sessions, but more variable in 15-s delay sessions (Fig. 8, C and D). Similar results were obtained with the analysis of pyramidal neuronal activity (Fig. 8, E to H). These results support the possibility that delay-period mPFC neural circuit dynamics undergo considerable changes as delay duration becomes longer than 4 s. Consistent with this possibility, a previous study has shown that mPFC neurons are actively recruited following 4 s since delay onset for the maintenance of target-related information during a long delay period (31). These findings underscore the importance of considering delay duration in future research.

Fig. 8. Neural activity dynamics differ between short and long delays.

(A and B) K-means clustering of VIP neuronal delay-period activity. Top: Averaged delay-period activity of each cluster in 4-s (A) and 15-s (B) delay sessions. Bottom: Heat maps of individual VIP neuronal delay-period activity. Colors on the right denote distinct clusters. (C and D) K-means clustering of VIP neuronal target selectivity. The same format as in (A) and (B) except that target selectivity was analyzed instead of neural activity. (E to H) Results from the analysis of pyramidal neurons. The same format as in (A) to (D). Shading, SEM across neurons.

DISCUSSION

The modulation of prefrontal working memory by dopaminergic mechanisms has been a subject of study since the late 1970s. However, earlier efforts were constrained by technical limitations. To tackle this long-standing issue, we used state-of-the-art techniques, focusing specifically on VIP neurons and their D1Rs. Our findings highlight the critical role played by VIP neurons in working memory and the importance of VIP neuronal D1Rs as mediators of dopaminergic influences on working memory.

Role of VIP neurons in working memory

Our previous studies in the mouse mPFC have shown more important roles of SST than parvalbumin (PV)–expressing interneurons and IT than pyramidal-tract projection neurons in working memory (21, 29). Together with these studies, the present study indicates important roles of VIP, SST, and IT neurons in the mPFC in mediating working memory. Our results are also consistent with the finding that VIP neurons mainly exert their inhibitory influences on SST neurons (14, 16, 32). Currently, the specific roles played by each neuron type and how they interact with each other to support working memory are unknown [see (33)]. Nevertheless, the inactivation effect of VIP neurons on behavioral performance was considerably greater compared to those of SST and IT neurons. SST and IT neuronal inactivation impaired behavioral performance only modestly and only when the delay was longer than 5 s [SST, 10 s, (29); IT, 15 s, (21)]. The behavioral effect of VIP neuronal inactivation, on the other hand, was evident even at 4-s delay. A cross-temporal decoding analysis revealed that mPFC neurons persistently maintain sample information for the initial ~2 s of the delay period even in error trials [current and previous study, (21)], suggesting long-lasting sensory responses of the mPFC neural network. Furthermore, taking into account the time for motor preparation, the actual duration required to maintain working memory is likely to be shorter than 2 s in 4-s delay tasks. Remarkably, VIP neuronal inactivation impaired behavioral performance even under this condition. With the caveat that the relative level of neuronal inactivation may vary across studies, this finding is consistent with the notion that VIP neurons exert powerful influences on PFC circuit operations by modulating other inhibitory neuronal activity (13–15, 32). VIP neurons may play a pivotal role in overseeing PFC circuit processes supporting working memory and other higher cognitive functions.

Role of VIP neuronal D1Rs in working memory

A large body of studies in monkeys and rats has shown the involvement of PFC D1Rs in working memory and its inverted U-shaped relationship with behavioral performance (7–9, 11). Consistent with these results, we found that injecting SCH23390, a D1R antagonist, into the mouse mPFC impairs working memory. Because pyramidal and VIP neurons are major D1R-expressing neurons in the mouse mPFC, the SCH23390 effect is most likely mediated by pyramidal neurons and/or VIP neurons. We found that both behavioral effects of D1R-KD and physiological effects of DTS are greater in VIP than pyramidal neurons. This, along with exceptionally powerful influences of VIP neuronal activity on mPFC circuit operations, may explain why D1R-KD in VIP neurons, but not pyramidal neurons, had a significant effect on behavioral performance. Overall, our results suggest that even a small change in VIP neuronal D1R activation can have a large impact on PFC circuit operations. The PFC is implicated in diverse neuropsychiatric disorders accompanying poor working memory, such as schizophrenia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression. Clarifying the roles of VIP neurons and their D1Rs in working memory may lead to a better understanding of the etiology of these mental diseases along with the identification of effective therapeutic targets.

Laterality in dopaminergic modulation of delay-period activity

The effects of dopamine on delay-period neural activity and behavior were complex, indicating the involvement of multiple factors in determining its influence. First, notable differences emerged between the 4-s and 15-s delay sessions. Dopamine release varied between correct and error trials during the 15-s delay but not during the 4-s delay. Also, during the 4-s delay, DTS more strongly enhanced VIP neuronal activity related to ipsilateral targets compared to contralateral targets; however, the opposite pattern was observed during the 15-s delay. These findings are consistent with the observation that neural activity dynamics differ between the 4-s and 15-s delays. Second, during the 15-s delay, dopamine release was influenced by both the upcoming choice and performance (correct versus error), suggesting that the forthcoming action alone does not fully determine dopamine release. Third, while the effects of DTS were generally consistent across VIP and pyramidal neurons, they were not identical. DTS biased the 4-s delay-period activity toward the ipsilateral target in VIP neurons and toward the contralateral target in pyramidal neurons. Together, these results indicate the involvement of multiple factors in shaping dopamine’s impact on prefrontal neural activity and working memory–related behaviors. Clearly, further research is needed to elucidate the precise mechanisms by which dopamine modulates PFC neural network dynamics during the delay period.

Despite these complexities, DTS consistently biased the animals’ choices toward the contralateral target without altering overall behavioral performance in both the 4-s and 15-s delay sessions. Additionally, during the 15-s delay, dopamine release was higher for contralateral than ipsilateral choices, and DTS more strongly increased contralateral target–related neural activity for both VIP and pyramidal neurons. These results suggest that dopamine plays a role in promoting contralateral target choices, highlighting the lateralized nature of dopamine’s action on prefrontal neural processes during the delay period. This finding aligns with earlier studies in monkey PFC, where D1R agonists and antagonists selectively influenced contralateral choices while leaving ipsilateral choices unaffected (7, 34). These results are consistent with the established role of the PFC in controlling egocentric spatial behavior (35, 36) and may reflect the fundamental importance of choosing between leftward and rightward movements for survival in natural environments. Our study leaves room for further exploration, particularly regarding whether dopamine enhances delay-period working-memory signals in tasks that do not involve laterality, such as delayed go-no-go tasks. Additionally, given the difference in DTS effects on directional target selectivity between the 4-s and 15-s delays, it remains to be clarified how the physiological effects of DTS translate into behavioral outcomes. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that the mammalian VTA-PFC system has likely evolved primarily to facilitate neural processes associated with planning and controlling lateralized movements.

Multifaceted roles of dopamine in the mPFC

The major dopaminergic pathways of the brain include the nigrostriatal, mesolimbic, and mesocortical pathways (37). Extensive research underscores the critical role of the nigrostriatal pathway in controlling movement, with its degeneration causing the motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease (38). The mesolimbic pathway is well known for its roles in motivation and reward seeking (39). In contrast, the function of the mesocortical dopamine pathway, which is crucial for cognition (40), has received far less attention (41). Historically, dopamine signals have often been linked to reward-related signals, such as reward prediction errors (42, 43). The mesocortical dopamine pathway is also implicated in reward processing (44), as observed in the present study (Fig. 4). However, recent studies have shown that dopamine signals in the mPFC may also convey aversive signals (45, 46). Given that our current task involves a rewarding context, it would be intriguing to investigate the impact of dopamine on working memory in an aversive context. Dopamine may enhance the functioning of the mPFC in working-memory tasks, regardless of whether the outcome is positive or negative. Alternatively, dopamine’s effects on working memory may vary substantially depending on whether the environment is rewarding or punitive. These investigations are expected to provide valuable insights into how dopamine affects the cognitive and reward processing functions of the mPFC.

Lens implantation in the mPFC

Inserting the prism-attached GRIN lens into the mPFC inevitably causes some brain damage, raising concerns about potential impacts on functions like working memory. However, lens-implanted mice performed comparably to nonimplanted mice in our working-memory tasks (VIP neuronal recording versus chemogenetic DMSO groups, 84.5 ± 9.4 versus 82.1 ± 9.4% correct choices, respectively; t test, t22 = 0.788, P = 0.439), suggesting that the procedure was not severely detrimental. The results may be due to compensation by the untreated hemisphere. However, considering that even unilateral mPFC inactivation can impair working memory (47), our prism-GRIN lens implantation is unlikely to be notably pathological, at least in terms of working memory. In a recent study, a GRIN prism lens was inserted in the opposite hemisphere, leaving the imaging hemisphere intact (48). We chose our method over this one because it preserves the integrity of superficial layers in both hemispheres, and maintains consistency with our previous study (21). Nevertheless, our method has the potential for substantial disruption to the connection between superficial and deep layers. Therefore, future studies should weigh the pros and cons of different lens implantation methods when measuring calcium transient signals from the mPFC.

Limitation of the study

Our study has several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the role of prefrontal VIP neurons in mediating dopamine’s effects on working memory. First, it remains unclear whether delay-period VIP neuronal activity is associated with slowly decaying sensory responses, the maintenance of cue information, motor preparation, or a combination of these factors. We also cannot exclude the possibility that VIP neuronal target selectivity was driven by the animal’s covert movements. While this is a common challenge in working-memory research, further investigation is needed to clarify the psychological processes most closely linked to VIP neuronal activity during the delay period. Second, we used two different delay durations (4 and 15 s) and observed dynamic changes in delay-period activity, particularly after 4 s in the 15-s delay. The decrease in activity in the most active cluster during the early phase of the 15-s delay suggests that distinct neural circuits or strategies may be engaged at different phases of the delay period. Therefore, the results from the 4-s and 15-s delays may reflect different aspects of VIP neuronal involvement in working memory. Similarly, it remains unclear to what extent the findings from the 4-s delay relate to neural processes supporting working memory in tasks using much longer delays [e.g., 30 to 60 s; (49, 50)]. Third, we used different manipulations of VIP neuronal activity. Chronic D1R-KD in VIP neurons may have broader effects on prefrontal circuitry beyond the intended manipulation. Long-term alterations in D1R expression could trigger compensatory adjustments in other neural circuits, potentially influencing additional neurotransmitter systems and network dynamics. These potential off-target effects complicate the interpretation of the specific role of VIP neurons in working memory. Fourth, the control group for D1R-KD in pyramidal neurons showed a slower learning rate compared to control groups in other experiments. This discrepancy could be due to the use of different mouse lines with distinct genetic backgrounds across experiments, complicating the interpretation of results from pyramidal neuronal D1R-KD experiments. These limitations, along with the complexity of the neural processes underlying working memory, emphasize the need for a more nuanced understanding of how VIP interneurons, dopamine, and other neural elements interact to support this cognitive function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

VIP-Cre (JAX010908, Jackson Laboratory; 48 male and 15 female, B6129SF2/J background), CamKIIa-Cre (JAX005359, Jackson Laboratory; 9 male and 7 female, C57BL/6NJ background), and DAT × VIP-Cre (JAX006660, Jackson Laboratory; 9 male and 1 female) knockin mice were used to target VIP neurons, pyramidal neurons, and VTA dopaminergic terminals, respectively, in the mPFC (see table S1). The mice were handled extensively and water-deprived so that their body weights were maintained at >80% of ad libitum levels throughout the experiments. They were 6 to 8 weeks old at the time of virus injection surgery. Each mouse was housed individually, and all experiments were performed in the dark phase of a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All animal care and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the directives of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (approval number KA2022-031).

Behavioral task

The mice were trained to perform a delayed match-to-sample task under head fixation (20, 21). The mice were faced with two identical water lick ports, one on their left and the other on their right, that were in retracted positions before trial onset (Fig. 1A). At trial onset, a randomly chosen water lick port was advanced toward the animal, delivering a 1.5-μl drop of water as a reward for the animal to consume (sample phase; 2 s). A green LED light was turned on during the sample phase. After the sample phase, the advanced water lick port was retracted, and a delay period of up to 15 s followed (delay phase). Following the delay period, both water lick ports were simultaneously advanced toward the animal together with a brief (100 ms) buzzer sound (choice phase). If the mouse licked the same lick port that was advanced during the sample phase within 4 s, it received a 3-μl drop of water from the chosen lick port. If the mouse licked the other lick port, both water lick ports were retracted in 1 s without any water delivery (see Fig. 1B and movie S1). A new trial began after an ITI (uniform random distribution; 5 to 10 s in chemogenetic, D1R-KD, antagonist-infusion, and calcium imaging experiments; 7 to 15 s in GRAB imaging and VTA terminal stimulation experiments).

Behavioral training

To acclimate the mice to the behavioral setting, they were placed in the behavioral apparatus and provided with water (1.5 μl), which was delivered from a randomly chosen water lick port every 2 s, for 2 days (250 trials per day). Following the habituation phase, the mice were trained in the delayed match-to-sample task initially with a delay period of 0.5 s. The duration of the delay period was progressively increased to 1, 2, 3, and 4 s across daily sessions as the mice reached the performance criterion (>70% correct choices per session) for each duration (total 4 to 7 days). The mice were considered well trained when their performance in the task with a 4-s delay exceeded 70% correct choices for two consecutive sessions. Some mice were further trained in the task with the delay gradually increased up to 15 s (in 3- to 5-s steps) until they met the performance criterion (>70% correct choices; total 3 to 4 days).

Surgery

The mouse was anesthetized with isoflurane [1.5 to 2.0% (v/v) in 100% oxygen flow], and its head was fixed in a stereotaxic frame (Kopf 940, Kopf, CA, USA). One or two small burr holes were made on the cranial surface targeting the mPFC unilaterally or bilaterally (1.80 mm anterior and 0.33 mm lateral to bregma). For those mice used for optostimulation, three burr holes were made targeting the mPFC unilaterally and VTA bilaterally (3.08 mm posterior and 0.5 mm lateral to bregma). We injected diluted AAV carrying various genes slowly (0.5 μl/min) into the mPFC or VTA (1.5 and 4.25 mm ventral to brain surface, respectively) using a glass pipette. For calcium and dopamine sensor imaging, following virus injection, a GRIN lens with prism (diameter, 1 mm, length, 4.3 mm, 1 mm × 1 mm prism attached, 1050-004601, Inscopix, CA, USA) was implanted targeting either layer 2/3 (VIP neuronal calcium imaging and dopamine sensor imaging) or layer 5 (pyramidal neuronal calcium imaging) in the mPFC (2.0 mm ventral to brain surface). For D1R antagonist infusion, two cannulas (diameter, 1 mm) were implanted bilaterally (1.84 mm anterior and 0.4 mm lateral to the bregma; 1.2 mm ventral to brain surface) without virus injection. If necessary, the scalp skin at the injection site was sutured or cemented to facilitate postoperative recovery. At least 1 week was allowed for recovery from surgery before experiments.

VIP neuronal calcium imaging

The AAV carrying the gene for a genetically encoded calcium indicator (pGP-AAV1-syn-FLEX-jGCaMP7f-WPRE, Addgene #104492-AAV1) was injected into the mPFC (1.5 mm ventral from brain surface) of VIP-Cre mice and a GRIN prism lens was implanted unilaterally during surgery. Following 6 to 8 weeks since lens implantation, the baseplate for nVista 3.0 microscope (Inscopix, CA, USA) was attached to the skull. We checked calcium signals before fixing the baseplate in place to optimize its position. Calcium signals were acquired through the implanted GRIN lens and the microscope at 30-Hz frame rate using LED power of 0.4 to 0.8 mW/mm2. Spatial downsampling (× 1/4) and motion correction of calcium imaging data were performed using Inscopix Data Processing Software (version 1.3.1). The processed video was exported in TIFF format and analyzed with the CNMF-E algorithm to extract single-unit signals (51). Details of lens implantation and image processing are described in a previous report (21).

Chemogenetic inactivation

The AAV carrying the gene for hM4D(Gi) [pAAV2-hSyn-DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry, Addgene #44362-AAV2] was injected into the mPFC (1.5 mm ventral from brain surface) of VIP-Cre mice bilaterally during surgery. Following 4 to 6 weeks from the virus injection, CNO [0.5 mg/kg in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] or DMSO (0.5 mg/kg in PBS) was systematically injected (intraperitoneally) 30 min before behavioral testing for VIP neuronal inactivation and as a control, respectively.

D1R antagonist infusion

After recovering from cannula implantation surgery (5 to 7 days), a D1R antagonist, SCH23390 (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA, 1 μg/μl), or saline (0.5 μl) was injected into the mPFC bilaterally at a rate of 0.02 μl/min (0.5 μl in each hemisphere) 30 min before behavioral testing. Fluorescein (5 mM; Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA, 0.2 μl in each hemisphere) was injected before sacrifice to visualize drug spread in the brain. Histological examination showed the spread of fluorescein mostly within the prelimbic cortex, with a small amount of spread to the upper infralimbic and the lower anterior cingulate cortex (fig. S5A).

D1R knockdown

Behavioral effects of suppressing VIPD1R and PYRD1R expressions were examined in VIP-Cre and CamKIIa-Cre mice, respectively, that were injected with pSico-RED-shRNA virus bilaterally in their mPFC. The sequence for the target region of D1R shRNA was determined to be nucleotides 2778 to 2800 of the Drd1 mRNA, with a specific sequence of “5′-AAGAGCATATGCCACTTTGTATT-3′” based on a previous report (52). The D1R shRNA expression cassette was cloned directly into the pAAV-Sico-Red vector (pSico vector), which contains the reporter gene mCherry outside loxP-loxP sites, enabling conditional regulation of shRNA expression. When Cre recombinase is expressed in a cell, the green fluorescent protein (GFP) marker is excised, allowing the shRNA to be enabled, resulting in the disappearance of GFP expression. A scrambled shRNA–containing pAAV-Sico-Red construct was used as a control. Viral vectors carrying the D1R-shRNA and the control construct were generated at the Institute for Basic Science Virus Facility (https://centers.ibs.re.kr/html/virusfacility_en/center/center_0101.html) through AAV packaging.

Ex vivo patch clamp recording

To confirm the successful KD of D1R, ex vivo mPFC slices were prepared as previously described (53) and recordings were made from epifluorescence-identified neurons. Recoding electrodes (thin-walled borosilicate capillaries, 30–0062; Harvard Apparatus, MA, USA) were pulled to a resistance of 5 to 7 megohms using a two-step Narishige PC-10 micropipette puller and then filled with an internal solution containing 137 mM potassium gluconate, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes, 0.2 mM EGTA, 10 mM sodium phosphor-creatine, 4 mM Mg-ATP (adenosine triphosphate), and 0.5 mM Na-GTP (guanosine triphosphate) (potassium-based solution). Neural signals were low pass–filtered at 10 kHz using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, CA, USA), digitized at 10 kHz using a Digidata 1440 Digitizer (Molecular Devices), and stored on a personal computer running pClamp 7 (Molecular Devices). Recorded cells were excluded from the analysis if their resting membrane potential (RMP) was >−50 mV or the access resistance was not maintained at <20 megohms. Drugs were bath-applied using a gravity-fed system. To estimate dopamine modulation of neuronal firing, a depolarizing square current pulse (700-ms duration) was applied to the recorded neuron. The magnitude of the current pulse was adjusted to reliably evoke at least five APs. The current pulse was delivered five times at 10-s intervals. Firing modulation was calculated by comparing the average number of evoked APs before and 5 min after SKF-81297 bath application (10 μM, Tocris Bioscience #1447).

GRAB imaging of dopamine

The AAV carrying the gene for green fluorescent G protein–coupled receptor activation–based (GRAB) DA sensor (pAAV-hsyn-gDA3m, https://centers.ibs.re.kr/html/virusfacility_en/center/center_0101.html) was injected into the mPFC (1.5 mm ventral from brain surface) and then a GRIN lens with prism (diameter, 1 mm, length, 4.3 mm, 1 mm × 1 mm prism attached, 1050-004601, Inscopix, CA, USA) was implanted targeting layer 2/3 of the mPFC (2.0 mm ventral to brain surface) in VIP-Cre mice during surgery. Dopamine sensor imaging was performed 4 to 6 weeks after the surgery. Acquisition of fluorescent signals from GRAB dopamine sensors, motion correction, and image processing were performed using Inscopix Data Processing Software (version 1.3.1) in the same manner as in calcium imaging. Because dopamine sensors display a broad “bulk” signal over a large area of tissue, we determined the best focus plane based on clear blood vessel signals. We used the LED power between 0.2 and 0.4 mW/mm2, which is lower than that used in neuronal calcium imaging, and averaged signals from the entire field of view.

VTA terminal stimulation

During surgery, the AAV carrying the gene for a calcium indicator (pGP-AAV1-syn-FLEX-jGCaMP7f-WPRE for VIP neuronal calcium imaging, Addgene #104492-AAV1; a CamKII promoter-including gene, AAV1-CaMKII-GCaMP6f-WPRE-SV40, for pyramidal neuronal calcium imaging, Addgene #100834-AAV1) was injected in the mPFC (1.5 mm ventral from brain surface) unilaterally and the AAV carrying the gene for FLEX-ChrimsonR (AAV2-hSyn-FLEX-ChrimsonR-tdTomato, UNC, AV6555B) was injected into the VTA (4.25 mm ventral from brain surface) bilaterally in DAT × VIP-Cre mice. A GRIN prism lens was then implanted in the mPFC (2.0 mm ventral from brain surface; the same hemisphere where the calcium indicator was injected). VTA terminal stimulation began 8 to 10 weeks after surgery. We used a miniature microscope that allowed the use of Ca2+ imaging LED (EX-LED) and optogenetic LED (OG-LED) at the same time (nVoke, Inscopix, Palo Alto, CA). Ca2+ fluorescence was imaged continuously during the entire behavioral session with the following settings: frame rate, 30 Hz; EX-LED power, 0.4 to 0.8 mW/mm2; gain, 8. The terminals of VTA dopaminergic neurons were stimulated with square light pulses (5 ms at 20 Hz; OG-LED power: 5 mW/mm2, randomly selected 30% of trials) during the delay period (4-s delay sessions, entire delay period; 15-s delay sessions, last 7.5 s). This approach yielded insignificant amounts of biological and optical cross-talk between optogenetic LED and calcium imaging in a previous study (54). To verify dopamine release in response to the light stimulation, we performed GRAB-gDA3m sensor imaging in the mPFC while stimulating the terminals of VTA dopaminergic neurons 20 times each for 1, 4, and 7.5 s with 30-s interstimulation intervals in a separate group of mice (n = 3).

Histology

After the completion of imaging or behavioral testing, the mouse brain was perfused with 10 ml of cold 0.1 M PBS and then with 10 ml of ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) using a 10-ml syringe. The mouse brain was incubated first in 4% PFA at 4°C for 7 days, and the lens was gently removed from the brain. The brain was then incubated in 30% sucrose in 0.1 M PBS at 4°C for 2 days. The fixed, dehydrated brain was cut into 40-μm-thick coronal sections using a cryostat (Leica CM3050 S) and washed with 0.1 M PBS for 10 min. Slices were imaged on a slide-scanning microscope with a 10×/0.45 numerical aperture (NA) objective using Zen 2.5 software (blue edition, Axio scan Z1; Zeiss) or a confocal microscope with 10×/0.45 NA, 20×/0.8 NA, and 40×/1.20 NA water objectives using Zen 2011 SP7 software (black edition, LSM 780; Zeiss). Images were processed using Zen 2.5 lite software (blue edition; Zeiss).

Analysis

For the analysis of VIP and pyramidal neuronal activity during the well-trained stage, we analyzed the data obtained from the session with the largest number of recorded neurons among two to five sessions after reaching the performance criterion for each animal. For the analysis of dopamine release dynamics during the well-trained stage, we analyzed the data from the best-performance session among two to five sessions after reaching the performance criterion. For the training stage, we used the first 4-s training session and the data obtained from the mice with >90% of correct choices were excluded. All imaging analyses were based on ∆F/F (30-Hz frame rate). To reduce the effect of neuronal variability, the activity of each neuron was z-score normalized to its activity during the 1-s time window before sample onset (baseline activity; mean and SD across trials) to reduce the effect of neuronal variability. For GRAB-gDA3m imaging, individual trial data were z-score normalized to its 1-s baseline activity (mean and SD across 30 time windows) and smoothed with a Savitzky Golay filter (27-frame window with order 2) to reduce the effects of slow fluctuations in ∆F/F signals across trials and slowly decaying previous reward signals. The z-normalized individual trial data were then averaged for each session (see fig. S2 for a comparison of raw and normalized signals).

Target selectivity

Target-dependent firing of individual neurons was assessed by calculating the target selectivity as the following

where Contra and Ipsi denote z-score normalized calcium fluorescence signals in the contralateral- and ipsilateral-target trials, respectively, during a given analysis time window, and mean and SD indicate the mean and standard deviation across trials, respectively. The directional target selectivity was calculated in the same manner, but without taking the absolute value of the difference between Contra and Ipsi trials as the following

Target decoding

For neural decoding of target, we combined all cells across different sessions and predicted the target (the lick port presented during the sample phase) based on delay-period neuronal ensemble activity using the support vector machine (SVM; fitcsvm function of MATLAB using the linear kernel; MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). We randomly selected a given number of neurons for a given ensemble size and, for each selected neuron, randomly selected 30 correct left-sample and 30 correct right-sample trials (out of 36 to 81 correct left-sample and 30 to 76 correct right-sample trials). Then, a single trial was removed, and the sample lick port in that trial (target) was predicted based on neuronal ensemble activity in that trial (test trial) and neuronal ensemble activity in the remaining trials (training trials) separated by target (leave-one-out cross-validation). This procedure was repeated 100 times. Only correct trials were used for neural decoding of target unless otherwise noted. For neural decoding of target in error trials, we trained the classifier with ensemble activity in correct trials and tested target decoding with neuronal ensemble activity in error trials. For cross-temporal decoding, we trained the classifier with ensemble activity in the sample period (1-s window before delay onset) and tested target decoding with neuronal ensemble activity in another 1-s time bin that was advanced in 0.1-s steps during the time period spanning 1 s before and after the delay period.

Temporal information

Timing-related delay-period neural activity was assessed by decoding elapsed time based on neuronal ensemble activity using the SVM as previously described (21). We combined all cells recorded from different sessions, randomly selected a set of neurons for a given ensemble size, and randomly selected 30 correct trials regardless of sample target for each neuron. We divided the delay period excluding the first 0.5 s (0.5 to 4 s; total 3.5 s) into 10 equal duration bins, trained the SVM to predict the bin number (rather than target), and decoded the bin number using a leave-one-out cross-validation procedure. Decoding performance was estimated by calculating the temporal decoding accuracy—the difference in decoding error (the absolute difference between actual and predicted bin numbers) between the temporal bin-shuffled data (i.e., the order of 10 temporal bins was randomly shuffled) and the original data. Temporal decoding accuracy measures the degree to which temporal prediction is improved (reduced decoding error) by using the original instead of the temporally shuffled neural data. This procedure was repeated 100 times (using a randomly selected set of neurons and a randomly selected set of 30 correct trials regardless of sample target for each neuron per iteration).

Neural responses to task events

To examine neural responses to diverse task events, we computed the event selectivity for each task event using correct trials except when examining trial outcome (correct versus error)–related neural activity. Neural activity differentiating between the sample and choice phases was assessed by calculating the event selectivity as the following

where Sample and Choice denote z-scored ∆F/F calcium signals during the 1-s time window from sample onset and delay offset, respectively, regardless of the target of a given trial. Trial outcome-dependent neural activity was assessed by calculating the event selectivity as the following

where Correct and Error denote z-scored ∆F/F calcium signals during the 1-s time window after the first choice lick in correct and error trials, respectively. Neuronal responses to LED, buzzer, and ITI onsets were assessed by calculating the event selectivity for each of these events as the following

where After and Before denote z-scored ∆F/F calcium signals during 0.5-s time windows before and after LED, buzzer, or ITI onset, respectively.

Dopamine ramping signals

Delay-period GRAB-gDA3m ∆F/F values were z-scored relative to ∆F/F values during the baseline period (1-s period before sample onset; see above). The first 2 s of the delay period was excluded to eliminate cue-related phasic dopamine responses. The slope of dopamine release dynamics during the remaining delay period was determined with linear regression (fitlm function of MATLAB).

DTS effect

To assess the DTS effect on neuronal activity, we matched the number of trials between stimulation (ON) and nonstimulation (OFF) trials. Since the stimulation was given 30% of total trials, we divided the OFF trials into two halves. We randomly selected the half number OFF trials (OFF1 trials), and they were compared with ON trials. The rest of OFF trials were grouped as OFF2 trials. We compared neuronal activity, target selectivity, neural decoding of target, and directional target selectivity between ON and OFF1 trials. Those neurons whose activity in a given analysis window (second half of 4-s delay, entire 4-s delay, or second half of 15-s delay) differed significantly between ON and OFF1 trials (unpaired t test, P < 0.05) were defined as DTS-responsive neurons. When DTS had no significant effect on neuronal activity, to test whether this is because of mixed changes in neuronal activity (i.e., both enhancement and reduction) or the absence of DTS effect on it, we compared the absolute activity differences between OFF1 and OFF2 trials with that between ON and OFF1 trials. To examine the laterality of delay-period activity in the absence of stimulation, we analyzed all VIP and pyramidal neurons using all OFF (OFF1 + OFF2) trials. To compare directional target selectivity between error versus correct trials, we selected sessions with one or more error trials for both contralateral and ipsilateral trials.

K-means clustering

To examine major temporal dynamics of delay-period activity in an unsupervised manner, we calculated mean normalized activity or target selectivity during the delay period (4 or 15 s) of individual neurons and subjected them to K-means clustering (kmeans function of MATLAB with 10 times of replicates; MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). K-means algorithm starts with random K centroids and calculates squared Euclidean distance between all data points to the centroid, assigning points to the nearest centroid to make K clusters. This procedure was repeated 10 times to find the clusters with the least total variation within the clusters. We used the elbow method to determine the optimal number of clusters by calculating within cluster sum of squares (WCSS). After clustering, each neuron was assigned a label based on its corresponding cluster and the averaged activity of each cluster was compared.

Statistical tests

Results are presented as mean ± SEM unless noted otherwise. All statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB (version 2017a). Student’s t test, chi-square test, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, two-way mixed ANOVA, and Bonferroni post hoc test were used for group comparison. All tests were two sided, and a P value of <0.05 was used as the criterion for a significant statistical difference unless otherwise specified.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Research Center Program of the Institute for Basic Science (IBS-R002-A1; M.W.J.).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: J.W.B., J.H.Y., and M.W.J. Methodology: J.W.B., J.H.Y., and Y.L. Investigation: J.W.B., J.H.Y., and S.Y.C. Visualization: J.W.B. and J.H.Y. Resources: J.W.B., J.H.Y., S.Y.C., Y.L., and M.W.J. Funding acquisition: M.W.J. Data curation: J.W.B., J.H.Y., and S.Y.C. Validation: J.W.B., J.H.Y., S.Y.C., and M.W.J. Formal analysis: J.W.B., J.H.Y., and M.W.J. Project administration: J.W.B., J.H.Y., and M.W.J. Software: J.W.B. and J.H.Y. Writing—original draft: J.W.B., J.H.Y., and M.W.J. Writing—review and editing: J.W.B., J.H.Y., and M.W.J. Supervision: M.W.J.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The neural and behavioral datasets used in this study are available at: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.mcvdnck7c.

Supplementary Materials

The PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S16

Table S1

Legend for movie S1

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Movie S1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.J. M. Fuster, The Prefrontal Cortex (Academic Press, ed. 5, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Funahashi S., Working memory in the prefrontal cortex. Brain Sci. 7, 49 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baddeley A., Working memory. Science 255, 556–559 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman-Rakic P. S., Muly E. C. III, Williams G. V., D1 receptors in prefrontal cells and circuits. Brain Res. Rev. 31, 295–301 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark K. L., Noudoost B., The role of prefrontal catecholamines in attention and working memory. Front. Neural Circuits 8, 33 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cools R., Arnsten A. F. T., Neuromodulation of prefrontal cortex cognitive function in primates: The powerful roles of monoamines and acetylcholine. Neuropsychopharmacology 47, 309–328 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawaguchi T., Goldman-Rakic P. S., D1 dopamine receptors in prefrontal cortex: Involvement in working memory. Science 251, 947–950 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]