Abstract

Vaccine strains of human adenovirus serotypes 4 and 7 (HAdV-4vac and HAdV-7vac) have been used successfully to prevent adenovirus-related acute respiratory disease outbreaks. The genomes of these two vaccine strains have been sequenced, annotated, and compared with their prototype equivalents with the goals of understanding their genomes for molecular diagnostics applications, vaccine redevelopment, and HAdV pathoepidemiology. These reference genomes are archived in GenBank as HAdV-4vac (35,994 bp; AY594254) and HAdV-7vac (35,240 bp; AY594256). Bioinformatics and comparative whole-genome analyses with their recently reported and archived prototype genomes reveal six mismatches and four insertions-deletions (indels) between the HAdV-4 prototype and vaccine strains, in contrast to the 611 mismatches and 130 indels between the HAdV-7 prototype and vaccine strains. Annotation reveals that the HAdV-4vac and HAdV-7vac genomes contain 51 and 50 coding units, respectively. Neither vaccine strain appears to be attenuated for virulence based on bioinformatics analyses. There is evidence of genome recombination, as the inverted terminal repeat of HAdV-4vac is initially identical to that of species C whereas the prototype is identical to species B1. These vaccine reference sequences yield unique genome signatures for molecular diagnostics. As a molecular forensics application, these references identify the circulating and problematic 1950s era field strains as the original HAdV-4 prototype and the Greider prototype, from which the vaccines are derived. Thus, they are useful for genomic comparisons to current epidemic and reemerging field strains, as well as leading to an understanding of pathoepidemiology among the human adenoviruses.

There are five genera of adenoviruses (AdVs) comprising the family Adenoviridae. One genus includes the human adenoviruses (HAdVs). HAdVs have been identified and associated as infectious agents causing several diseases, including acute respiratory disease (ARD); for example, the HAdV serotype 4 (HAdV-4) prototype was first isolated by investigators from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research from ARD cases that occurred during an influenza-like epidemic at Fort Leonard Wood (Missouri) in the winter of 1952-1953 (http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/historiesofcomsn/section1.htm). Since then (25), and since the contemporaneous isolation and characterization of the first respiratory-illness-causing adenovirus in a civilian, HAdV-1 (41), 50 additional serotypes have been identified and characterized, with the newest two being isolated from the gastrointestinal tracts of immunocompromised patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections (16). The HAdVs are divided into six species (formerly subtypes or subgroups), classified as A to F, which are based on differentiating biochemical, immunological, and increasingly, as the sequence and molecular data become available, genomic properties (15). Although AdVs are of special interest in general in terms of their basic biology, there is focused attention on the HAdVs, since they are associated with several pathologies in humans (47). To illustrate, members of species C cause mild gastrointestinal and respiratory disease; among these, HAdV-5-based vectors are also important in gene therapy protocols (49). Respiratory diseases are also caused by another important grouping, the B1 and E species, which have been associated with ARD, as well as with conjunctivitis. Interestingly, the newest member of the B1 subspecies has been isolated from a gastrointestinal infection in a HIV-infected individual (16). This additional tropism for a B1 member may have implications for HAdV serotype evolution and pathoepidemiology.

HAdV infections are highly contagious and can spread easily within confined or isolated communities (18). For example, epidemics of ARD are common in dense and contained populations, such as military training venues and day care centers. This is documented extensively for the U.S. military populations in the literature and in an archived narrative (http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/historiesofcomsn/section1.htm). In particular, reemerging epidemic outbreaks of febrile respiratory infections caused by HAdV-4 and HAdV-7 among basic military trainees since the cessation of immunization are of immediate pressing concern to the U.S. Department of Defense (21). One study published in 2000 documents HAdV-4 infections in 57%, and HAdV-7 in 25%, of the isolates from throat cultures of trainees with respiratory disease (21). An “epidemic threshold” is defined arbitrarily as 1.5 cases per 100 trainees per week. The reemergence of HAdV-caused ARD during a temporary lapse of vaccine coverage in 1994-1995 is documented in a study noting an 11.6% rate of ARD hospitalization in a military group in the week ending 6 May 1995. The following week brought a rate of 3%, with HAdV-4 characterized in 85.7% of the cases (3).

During the 1950s and 1960s, well-documented studies of respiratory disease epidemic outbreaks among basic military trainees found that up to 80% of recruits showed evidence of HAdV infections, with 20% requiring hospitalization (19). The burden of this morbidity was and is high and costly. Additionally and more devastating, a few cases have resulted in fatalities within the military (17, 34, 44). This recent reemergence of HAdV-related ARD and the burden of high costs of patient care, along with loss of worktime and training time, have prompted the Department of Defense to initiate the redevelopment of vaccines against ARD-related HAdVs.

Formalin-inactivated HAdV vaccines were tested in the mid-1950s (24). Several concerns, including the potential oncogenicity of the HAdV-3 and -7 serotypes, contamination of the vaccine stocks with simian adenovirus 40, and apparent lot-to-lot variations led to the suspension of their use in 1963 (19, 33). Alternative live vaccines for both HAdV-4 and -7 were tested subsequently, and both were deployed effectively in 1971 (11, 19, 53, 54). Both were administered routinely as combined prophylactic oral doses until the supplies were exhausted in the late 1990s. The use of these vaccines dramatically and effectively lowered HAdV morbidity and mortality rates among military recruits, by 95 to 99%; additionally, the overall ARD morbidity rate was lowered by 50 to 60% (21). In 1996, Wyeth-Lederle Laboratories (Marietta, PA), the sole producer of the vaccines, ceased production, citing a lack of funds to upgrade its production facilities. With the cessation of vaccinations, there has been a reemergence of HAdV infections with a concomitant rise in ARD cases. In fact, HAdV-related ARD cases have risen to the prevaccination era levels (21).

As the production of vaccines was concluding, an HAdV surveillance program was initiated at the Respiratory Disease Reference Laboratory, located in the U.S. Naval Health Research Center (NHRC; San Diego, CA) (43). One mission of the NHRC is to monitor emerging and reemerging respiratory pathogens, into which the documentation of the epidemiology of HAdV during and after the period of vaccine cessation fits (21). Sampling was conducted at eight U.S. military cross-service training venues (43). The surveillance, analyses, and documentation showed large increases in HAdV morbidity, including several cases of mortality, clearly suggesting that vaccination was and is still the best method of preventing HAdV-associated ARD outbreaks. This contributed to the decision to redevelop and redeploy HAdV vaccines. Understanding the original vaccine strains will contribute to the continuing development of effective vaccines. These strains are the bases for the current versions of the vaccines.

This report presents the complete DNA sequences and detailed annotations of the genomes of the vaccine strains corresponding to HAdV-4 and HAdV-7 (HAdV-4vac and HAdV-7vac, respectively). The HAdV4vac genome sequence contains 35,994 bp, encoding 49 proteins, and two RNAs. Analogously, the HAdV-7vac genome sequence contains 35,240 bp, encoding 48 proteins, plus two RNA coding sequences. The organization of coding sequences in both genomes is similar to that in other members of the genus Mastadenovirus, which comprises human and monkey adenoviruses. Comparisons between the vaccine strains and related prototypes are presented in the context of the genomics and bioinformatics analyses for identifying unique genome signatures for the development of molecular diagnostics tools and protocols and for vaccine redevelopment. As an example of the use of these reference sequences in molecular forensics, these data suggest that HAdV-4vac was derived from the circulating original HAdV-4 prototype at the time, while HAdV-7vac was derived from a circulating Greider-like strain (HAdV-7a), as opposed to the contemporary Gomen prototype strain (HAdV-7).

Given the repository of data and strains collected at NHRC, detailed comparisons and epidemiological studies may be extrapolated from the “vaccine period,” adding to an understanding of HAdV and ARDs in the context of pathoepidemiology. In this context, these genome references are useful and critical as gold standard references, i.e., to identify epidemic outbreak strains. Furthermore, this paper also serves as another example of whole-genome comparative studies of viruses as a means to characterize pathogens rapidly, perhaps as an accepted gold standard, as recent advances in DNA-sequencing technologies have dramatically reduced the time and expense involved in sequencing and analyzing the whole genomes of microorganisms. With the increasing availability of whole-genome data, it will be possible to make global comparisons of the genome sequences of organisms of interest. Such whole-genome analyses offer a complete picture of the similarities and differences of two genomes, and as an example, have led to groundbreaking results in the field of tuberculosis vaccine research (4, 9). The findings presented in this publication will complement HAdV vaccine development and further a better understanding of HAdV pathoepidemiology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

HAdV-7vac was resuscitated from an original Wyeth-Lederle Laboratories (Marietta, PA) vaccine tablet archived at the NHRC (San Diego, CA). The paired HAdV-4vac strain was not as robust, as several attempts to resuscitate it from the original tablets failed. Instead, this HAdV-4vac strain was acquired as a gift from Leta Crawford-Miksza (California State Department of Health Services, Berkeley). The original source was also a Wyeth-Lederle vaccine tablet that was used for their hexon studies (13).

Cells, virus stocks, and DNA preparation.

Virus stocks were expanded in A-549 cells (ATCC CCL-185), a human lung tumor cell line that provided the necessary quantities of HAdV-1 particles (31). The cell line was infected with adenovirus at an approximate multiplicity of infection of 5; when the entire monolayer showed viral cytopathogenic effect, the medium was gently decanted and replaced with Hirt's lysis buffer, followed by the addition of proteinase K to the monolayer. The Hirt method for extraction of virus-infected cells to purify low-molecular-weight DNA directly from the infected cell lysates proved to be the most efficient method, so it was not necessary to purify the virus particles beforehand. According to this protocol, adenoviral DNA was prepared essentially as described previously (32).

PCR strategy and methodology.

Standard PCR methodologies were used to amplify regions to be sequenced, as detailed for HAdV-1 (31). PCR conditions, in brief, called for Pfu Ultra DNA Polymerase (Stratagene, Inc.) at 2.5 units in a total volume of 50 μl containing 5 μl of 10× polymerase buffer (Stratagene, Inc.), 3.5 μl dimethyl sulfoxide (7% final), deoxynucleoside triphosphates (200 μM; stock solutions of 1 mM), oligonucleotide primers (0.5 μM; stock solutions of 10 μM), and template DNA (30 ng; stock solutions of 33.16 ng/μl). An MJ Research (Waterstown, MA) Dyad thermocycler was used under the following conditions: 95°C for 2 min for one cycle to denature, with cycling at 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 9 min (for 5- to 6-kb amplicons and 3 min for 2- to 3-kb amplicons), and 72°C for 9 min (for 5- to 6-kb amplicons and 3 min for 2- to 3-kb amplicons) for 35 cycles to amplify. At the conclusion of the cycling, an additional extension period of 72°C for 10 min was included, after which the samples were cycled into storage at 4°C.

DNA sequencing. (i) “Shotgun” sequencing of HAdV-7vac genome.

Since no previous HAdV-7 or other B species genome sequence was available to serve as a reference, a shotgun strategy was employed to provide overlapping complemented genome coverage. Purified genomic DNA was partially digested with SauIIIA1, separated from small (<400 bases) DNA fragments by passing it through a SizeSep400 Sepharose column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), and ligated to BamHI-digested pBlueScript II SK(+) plasmid (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). After selection of insert-containing clones, 100 to 200 clones were amplified using TempliPhi reagent (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) and sequenced (200 ng of template per reaction) with either KS and SK or M13-20 and M13F primer sets using the DYEnamic ET Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) on an ABI Prism 377 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequences were trimmed and assembled using Sequencher (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI).

(ii) “Leveraged” primer walk sequencing of HAdV-4vac genome.

The genome sequence of HAdV-4, determined earlier by the Epidemic Outbreaks Consortium (39), was used to generate a scaffold of minimally tiled and overlapping primers for PCR amplification and DNA sequencing, leading to threefold coverage of each base with complementary reads of the strands. As shown in a study to rapidly resequence the HAdV-1 genome, this strategy allows efficient resequencing of related genomes at minimal cost and effort (31). PCR was performed using Pfu Ultra DNA Polymerase (Stratagene, Inc.) and 30 ng of purified adenoviral DNA as a template. Fifty-microliter reactions were set up as follows: 95°C for 2 min for one cycle to denature and 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 9 min for 5- to 6-kb amplicons (3 min for 2- to 3-kb amplicons), and 72°C for 9 min for 5- to 6-kb amplicons (3 min for 2- to 3-kb amplicons) for 35 cycles to amplify. At the conclusion of the cycling, an additional extension period of 72°C for 10 min was included, after which the samples were cycled into storage at 4°C. The amplicons were visualized on a 1% agarose gel and then extracted and purified using a Millipore Ultrafree-DA centrifugal filter device. The amplicons were sequenced (200 ng per reaction) with the PCR primers using the BigDye Terminator version 3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on an ABI 3100 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

(iii) Direct sequencing of inverted terminal repeat (ITR) ends.

Both ends of this linear double-stranded DNA genome were determined by direct sequencing of the purified genomic DNA. Primers were designed from internal sequences established during the early sequencing phase and were used to sequence directly off the ends in a 40-μl reaction mixture using 16 μl of BigDye, 0.2 to 1.0 mg of template, and 20 pmol of primer. Cycling conditions were according to the manufacturer's instructions: 95°C for 5 min for one cycle to denature, followed by 95°C for 1 min, 50°C for 20 s, and 60°C for 4 min for 50 cycles to amplify. At the conclusion of the cycling, the samples were stored at 4°C. The sequencing reaction mixtures were purified with Centri Sep Spin Columns (Princeton Separations, Adelphia, NJ).

Sequence bioinformatics. (i) Sequence assembly and quality control and assurance.

DNA sequence ladders were assembled using Sequencher 4.1.1 (Gene Codes Corporation, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI). Visual inspection of the sequence assembly data resolved several miscalls and mismatches. Genome annotation provided an additional layer of sequence quality control. Unresolvable and ambiguous sequences were resequenced with primers closer to the regions in question.

(ii) Genome annotation and sequence analysis.

General features of the DNA sequence, such as percent G+C content and repetitive sequences, were revealed using the Wisconsin GCG package (SeqWeb version 2). The coding sequences were annotated by first segmenting them into contiguous 1-kb nonoverlapping segments and then querying the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. This was repeated using windows of 1-kb segments that overlapped by 500 nucleotides. The algorithm is identical to the annotation protocol employed for the HAdV-1 analysis (31). The sequence fragments were queried systematically against the nonredundant NCBI database using the BLASTX program of the BLAST suite sequence alignment software (2). The searches used the default parameters of a word size of 3 and expectation of 10, with the BLOSUM62 substitution matrix and with gap penalties of 11 (existence) and 1 (extension). Low-complexity sequences were filtered out of the queries.

GenomeScan was used for predicting theoretical genes. This approach was especially useful for identifying exons from the coding sequences where exon-intron borders were difficult to determine. To enable this feature, the algorithm uses exon-intron identification combined with similarity searches of a sequence database in order to predict coding sequences in a given DNA fragment (57). In parallel, novel sequences or “hypothetical proteins” were also identified using another gene prediction software program, GeneMark (6). In these annotations, while GeneMark had a slightly higher accuracy than GenomeScan, neither was completely accurate or comprehensive in generating a list of putative genes. To visualize and record progress, the web-accessible Sanger Center annotation tool Artemis was used to expedite genome annotation (5).

CLUSTALX was used to perform multiple-sequence alignments of adenovirus proteins (52). Sequence alignments were performed with default parameters (for pairwise alignment, gap opening and extension penalties of 10 and 0.1 and the Gonnet 250 protein weight matrix; for multiple alignments, gap opening and extension penalties of 10 and 0.2; for both, the Gonnet series of protein weight matrices was applied). All phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method described in the literature (45). Bootstrapping was performed with 1,000 resampling iterations to assess the robustness of the trees.

Substitution rates for coding sequences of interest were calculated by using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analyses (MEGA) software version 2.1 (30). The rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution were calculated according to an unweighted method of Nei and Gojobori (38).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The genomes of the vaccine strains corresponding to HAdV-4 and HAdV-7 have been deposited in GenBank at the NCBI as HAdV-4vac (accession no. AY594254) and HAdV-7vac (accession no. AY594256).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sequencing strategies and overview of annotation.

Two different DNA-sequencing strategies were employed to map the genomes. Since no species B genome sequence was available, HAdV-7vac was sequenced by the “shotgun” method. This involves fractionating the genome into smaller pieces, subcloning it into a plasmid, and sequencing it with universal primers. Walking with custom-designed primers filled the gaps. On the other hand, as the genome of HAdV-4 was recently determined, and with the corroborating sequences in GenBank, a “leveraged primer walk strategy” was employed for HAdV-4vac.

The genome sequences of both HAdV-4vac and -7vac were annotated to identify biological features. This was facilitated by the use of reference genomes from the HAdV-4 (GenBank AY594253) and HAdV-7 (GenBank AY594255) prototype strains recently determined (39, 40). The HAdV-4vac sequence includes 49 protein and two RNA coding sequences, as presented in Table 1. Comparative genomic analysis shows that the prototype strain HAdV-4 includes essentially identical sequences, with a few exceptions. Functionally, the noncoding features, such as promoters and transcription factor binding and recognition sites, are conserved between the two strains, as shown in Table 2. However, the HAdV-4vac ITRs contain some intriguing differences, as will be discussed. In contrast, the HAdV-7vac sequence contains 48 proteins and two RNA coding sequences, displayed in Table 3, compared to its counterpart prototype strain, HAdV-7, which has 49 protein, plus the two RNA, coding sequences, with many sequence differences. This vaccine strain lacks the coding sequence for a hypothetical 7.9-kDa protein. Of note, a duplication of the E3 gene-encoded 20.6-kDa protein found in HAdV-7 is also conserved in HAdV-7vac. The ITRs are longer in HAdV-7vac (136 bp) than in HAdV-7 (108 bp) and contain several differences. Other noncoding biological features are conserved between the two strains, as noted in Table 4.

TABLE 1.

HAdV-4vac genome sequence annotationa

| Gene | Product | Location |

|---|---|---|

| E1A | ORF1 (putative protein) | 576-1154 |

| E1A | E1A 6.8-kDa protein | 576-650, 1236-1340 |

| E1A | E1A 28-kDa protein | 576-1142, 1235-1441 |

| E1A | E1A 24.6-kDa protein | 576-1049, 1235-1441 |

| E1B | Small T antigen | 1600-2001, 2003-2029 |

| E1B | E1B 20-kDa protein | 1600-2115 |

| E1B | E1B 8.2-kDa protein | 1905-2123, 3259-3276 |

| E1B | Large T antigen | 1905-3356 |

| E1B | E1B 16.8-kDa protein | 1905-2153, 3141-3356 |

| IX | Protein IX | 3441-3869 |

| IVa2 | IVa2 protein | 3930-5263, 5542-5554(c) |

| E2B | DNA polymerase | 5033-8605, 12212-12220(c) |

| Hypo | 19.4-kDa early protein | 5105-5674 |

| Hypo | 11.5-kDa early protein | 6126-6446 |

| Hypo | DNA-binding protein | 7814-8407 |

| Hypo | 14.1-kDa early protein | 7814-7819, 8536-8928 |

| E2B | Precursor terminal protein | 8404-10323, 12212-12220(c) |

| VA RNA I | VA RNA I | 10356-10514 |

| VA RNA II | VA RNA II | 10575-10743 |

| L1 | 52-kDa protein | 10765-11937 |

| L1 | Protein IIIa precursor | 11961-13736 |

| L2 | Penton protein (protein III) | 12222-12229 |

| L2 | Protein VII precursor | 14772-14779 |

| L2 | Protein V precursor | 16055-17080 |

| L2 | Protein X (protein mu) | 17103-17336 |

| L3 | Protein VI precursor | 17368-18141 |

| L3 | Hexon protein (protein II) | 18248-21058 |

| L3 | 23-kDa protease | 21082-21702 |

| E2A | DNA-binding protein | 21774-23312(c) |

| L4 | 100-kDa protein | 23341-25716 |

| L4 | 22-kDa protein | 25439-25978 |

| L4 | 33-kDa protein | 25439-25756, 25926-26252 |

| L4 | Protein VIII precursor | 26321-27004 |

| E3 | E3 12.1-kDa protein | 27005-27325 |

| E3 | E3 23.3-kDa protein | 27279-27911 |

| E3 | E3 19-kDa protein | 27893-28417 |

| E3 | E3 24.8-kDa protein | 28449-29111 |

| E3 | E3 6.3-kDa protein | 29279-29443 |

| E3 | E3 29.7-kDa protein | 29440-30264 |

| E3 | E3 10.4-kDa protein | 30273-30548 |

| E3 | E3 14.5-kDa protein | 30554-30994 |

| E3 | E3 14.7-kDa protein | 30987-31388 |

| L5 | Fiber protein | 31649-32926 |

| E4 | E4 7.4-kDa protein | 33022-33216(c) |

| E4 | E4 15.9-kDa protein | 33022-33270, 33996-34169(c) |

| E4 | E4 34.6-kDa protein | 33270-34169(c) |

| E4 | E4 14.1-kDa protein | 34072-34440(c) |

| E4 | E4 13.7-kDa protein | 34449-34802(c) |

| E4 | E4 14.6-kDa protein | 34799-35188(c) |

| Hypo | Hypothetical protein | 35335-35427 |

| E4 | E4 13.5-kDa protein | 35236-35610(c) |

Forty-nine protein and two RNA coding regions were identified in the HAdV-4vac genome sequence. Their corresponding proteins and functions are indicated (hypothetical proteins are marked as “Hypo”). The nucleotide positions of the start and stop codons and applicable splice sites are noted (5′-to-3′ direction). Coding sequences transcribed from the complementary strand are designated by “c,”e.g., 35236-35610(c).

TABLE 2.

HAdV-4vac genome noncoding feature annotationa

| Sequence motif | Function | Position |

|---|---|---|

| CTATCTECGGGG | ITR | 1-116 |

| TATAATATACC | DNA pol-pTP binding site | 9-18 |

| TATGCAAATAA | NFIII/OctI binding site | 41-51 |

| GGGGATGGGGC | SP1 binding site | 65-75 |

| TATTTA | TATA box for E1A | 479-484 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for E1A | 1499-1504 |

| TATATA | TATA box for E1B | 1558-1563 |

| TAAAAT | TATA box for IX gene | 3408-3413 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for pIX gene | 3880-3885 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for E2B and I | 3902-3907(c) |

| TGATTGGCTT | Inverted CAAT box for MI | 5803-5812 |

| GCCACGTGAC | Upstream element for MLP | 5823-5832 |

| GCCGGGGGGG | MAZ binding site for MLP | 5844-5853 |

| TATAAAA | TATA box for MLP | 5854-5860 |

| GGGGGCGGGCC | MAZ/SP1 binding site | 5861-5871 |

| TCACTGT | Initiator element for MLP | 5883-5889 |

| TTGTCAGTTTC | DE1 for MLP | 5970-5980 |

| AACGAG-TTTGA | DE2a and DE2b for MLP | 5985-6000 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for L1 | 13749-13754 |

| ATTAAA | Poly(A) signal for L2 | 17357-17362 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for L3 | 21725-21730 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for E2A | 21767-21772(c) |

| TATAAA | TATA box for E3 | 26686-26691 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for the E3 | 31428-31433 |

| AATATC | Poly(A) signal for L5 | 32986-32991 |

| AATATA | Poly(A) signal for E4 | 34392-34397(c) |

| TATATA | TATA box for E4 | 35687-35692(c) |

| GGGGATGGGGC | SP1 binding site | 35920-35930(c) |

| TATGCAAATAA | NFIII/OctI binding site | 35944-35954(c) |

| ATAATATACC | DNA pol-pTP binding site | 35977-35986(c) |

| CTATCTECGGGG | ITR | 35879-35994(c) |

Noncoding features in the HAdV-4vac genome sequence were identified by BLAST analyses with GenBank data. Their nucleotide signatures and putative functions are indicated, with positions of their locations noted in the 5′-to-3′ orientation. Functionality embedded within the complementary strand is designated by “c,”e.g., 3902-3907(c).

TABLE 3.

HAdV-7vac genome gene coding annotationa

| Gene | Product | Location |

|---|---|---|

| E1A | E1A 6-kDa protein | 572-647, 1247-1348 |

| E1A | E1A 32-kDa protein | 572-1157, 1246-1452 |

| E1A | E1A 28-kDa protein | 572-1067, 1246-1452 |

| E1B | 20-kDa protein, small T antigen | 1599-2136 |

| E1B | 55-kDa protein | 1904-3382 |

| E1A | Hypothetical protein | 1904-2172, 3166-3382 |

| pIX | Protein IX | 3476-3892 |

| E2B | pIVA2 | 3945-5278, 5557-5569(c) |

| E2B | DNA polymerase | 5048-8539, 13819-13827(c) |

| Hypo | A-106 hypothetical protein | 6141-6461 |

| Hypo | 13.6-kDa agnoprotein homolog | 7826-8422 |

| Hypo | Hypothetical 12.6-kDa protein | 8325-8570(c) |

| E2B | DNA terminal protein precursor | 8419-10386, 13819-13827(c) |

| Hypo | 8.8-kDa protein | 8545-8787 |

| Hypo | 11.3-kDa hypothetical protein | 9540-9854(c) |

| Hypo | 9.7-kDa hypothetical protein | 9754-10029 |

| VA RNA I | VA RNA I | 10419-10541 |

| VA RNA II | VA RNA II | 10651-10794 |

| L1 | 55-kDa protein | 10828-11997 |

| E2B | 6.1-kDa hypothetical protein | 12021-12194(c) |

| L1 | Protein IIIa precursor | 12022-13788 |

| L2 | Penton protein (protein III) | 12283-12291 |

| L2 | Protein VII precursor | 14860-14868 |

| L2 | Protein V precursor | 16141-17193 |

| L3 | Protein VI precursor | 17523-18275 |

| L3 | Hexon | 18388-21192 |

| L3 | 23-kDa protease | 21229-21858 |

| E2A | DNA-binding protein | 21947-23500(c) |

| L4 | 100-kDa hexon-assembly protein | 23531-26020 |

| L4 | 22-kDa protein | 25722-26321 |

| L4 | 33-kDa protein | 25722-26070, 26252-26595 |

| L4 | Protein VIII precursor | 26665-27348 |

| E3 | 12.1-kDa glycoprotein | 27348-27668 |

| E3 | E3 16.1-kDa protein | 27622-28062 |

| E3 | E3 18.3-kDa glycoprotein precursor | 28047-28565 |

| E3 | E3 20.1-kDa protein | 28595-29134 |

| E3 | E3 20.6-kDa protein | 29147-29716 |

| E3 | E3 7.7-kDa protein | 29731-29856 |

| E3 | E3 10.3-kDa protein | 29969-30244 |

| E3 | E3 14.9-kDa protein precursor | 30249-30653 |

| E3 | E3 14.7-kDa protein | 30646-31053 |

| U exon | U exon | 31072-31236(c) |

| L5 | L5 fiber protein | 31251-32228 |

| E4 | E4 ORF 6/7 | 32263-32514(c) |

| E4 | 33:2-kDa protein | 32511-33410(c) |

| E4 | E4 13.6-kDa protein | 33313-33681(c) |

| L5 | Agnoprotein | 33536-34045 |

| E4 | E4 13-kDa protein | 33690-34043(c) |

| E4 | 130-amino-acid protein | 34040-34429(c) |

| E4 | 13.9-kDa protein | 34471-34848(c) |

Forty-eight protein and two RNA coding regions were identified in the HAdV-7vac genome sequence. Their corresponding proteins and functions are indicated (hypothetical proteins are marked as “Hypo”). Nucleotide positions of the start and stop codons, as well as applicable splice sites, are noted (5′-to-3′ direction). Coding sequences transcribed from the complementary strand are designated by “c,” e.g., 31072-31236(c). ORF, open reading frame.

TABLE 4.

HAdV-7vac genome noncoding-feature annotationa

| Motif | Function | Position |

|---|---|---|

| CTATA-CGTGACT | ITR | 1-136 |

| ATAATATACC | DNA pol-pTP binding site | 5-14 |

| TGTTATGGTGCCAA | NFI binding site | 22-35 |

| CTGTGTGG | Sp1 recognition site | 68-75 |

| TATTTA | TATA box for E1A | 476-481 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for E1A | 1490-1495 |

| TATATA | TATA box for E1B | 1545-1550 |

| TAAAGT | TATA box for pIX gene | 3380-3385 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for pIX gene | 3905-3910 |

| AATACA | Poly(A) signal for E2B | 3923-3928(c) |

| TGATTGGCTT | Inverted CAAT box for MLP | 5818-5827 |

| GCCACGTGAC | Upstream element for MLP | 5838-5846 |

| GCCGGGGGGG | MAZ binding site for MLP | 5859-5868 |

| TATAAAA | TATA box for MLP | 5869-5874 |

| GGGGGCGGACC | MAZ/SP1 binding site for MLP | 5876-5886 |

| TCACTGT | Initiator element for MLP | 5898-5904 |

| TTGTCAGTTTC | DE1 for MLP | 5985-5995 |

| AACGAGGAGGATTTGA | DE2a and DE2b for MLP | 6000-6015 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for L1 | 13801-13806 |

| ATTAAA | Poly(A) signal for L2 | 17467-17572 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for L3 | 21878-21883 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for E2A | 21890-21895(c) |

| TATAAA | TATA box for E3 | 27030-27035 |

| AATAGA | Poly(A) signal for L4 | 27547-27552 |

| AATAAA | Poly(A) signal for E3 | 31059-31064 |

| AATATC | Poly(A) signal for L5 | 34052-34057 |

| AATATA | Poly(A) signal for E4 | 32247-32252(c) |

| TATATATA | TATA box for E4 | 34929-34935(c) |

| CTGTGTGG | Sp1 recognition site | 35156-35165(c) |

| TGGAATGGTGCCAA | NFI binding site | 35198-35211(c) |

| ATAATATACC | DNApol-pTP binding site | 35219-35228(c) |

| CTATCTETAACAT | ITR | 35129-35236(c) |

Noncoding features in the HAdV-7vac genome sequence are annotated. These features were identified by BLAST analyses with GenBank data. Nucleotide signatures and putative functions are indicated. The nucleotide positions of the locations are noted in the 5′-to-3′ orientation. Functionality embedded within the complementary strand is designated by “c,”e.g., 21890-21895(c).

HAdV-7 and HAdV-7vac sequence comparison and applications of the sequence.

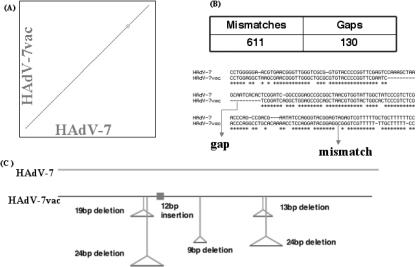

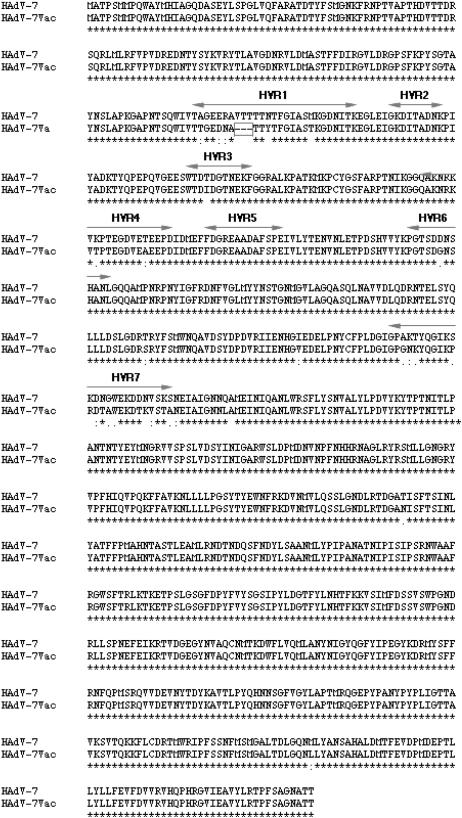

Whole-genome alignment and comparisons of the sequences from both vaccine and prototype strains were performed using the dot blot software PipMaker to analyze the nucleotide sequences. PipMaker uses the BLASTZ alignment algorithm for whole-genome alignments (48). For both vaccine genomes, PipMaker analysis suggests minimal differences at the gross level, as illustrated by the HAdV-7 sequences in Fig. 1A. However, under finer scrutiny, HAdV-7vac has 611 mismatches and 130 gaps compared to the prototype Gomen strain HAdV-7. An example of each is highlighted in Fig. 1B. For these analyses, PipMaker counts each “missing base” as a gap, so a 3-base deletion is counted as three gaps. The Gomen genome was chosen as a reference HAdV-7 prototype for these studies, as its complete genome is available (39, 40). Several selected indels found in the HAdV-7vac sequence are summarized in Table 5, along with their effects on various coding sequences. “Selected” indels are defined as those affecting ≥9 nucleotides or changing protein-coding potential. These are as follows. (i) The VA RNA I and II coding regions of the HAdV-7vac have been shortened by a 19-bp and a 24-bp deletion, respectively. The VA RNA genes are non-protein-coding genes whose products have been shown to antagonize the antiviral activities of host interferons (36). (ii) A 12-bp in-frame insertion adds four amino acids to the L1 52-kDa protein sequence. The amino acid sequence Q18 Q19 L20 Q21 is added to the N-terminal sequence of the 52-kDa protein. The 52-kDa protein serves as a scaffold for the assembly of the virus capsid (23). The structure and key residues of this protein have not been identified, so it is difficult to predict what effect such an insertion may have on the structure and function of the 52-kDa protein. (iii) A 9-bp in-frame deletion excises three amino acids, VTT, from the N terminus of the hexon of HAdV-7vac (Fig. 2). The hexon protein is the major structural and antigenic component of the HAdV capsid (46). This 9-bp deletion falls within a variable region of the hexon that contains most of the antigenic epitopes (12). (iv) A 13-bp deletion, TCTAAAAATCACC, shortens the HAdV-7vac E3 7.7-kDa protein-coding sequence compared to HAdV-7. This 7.7-kDa protein belongs to the E3 transcription unit, whose products are required to evade the host immune system (29, 56). However, the effect of this deletion remains to be seen, as the specific function of the E3 7.7-kDa protein has not been demonstrated in the literature. (v) A 24-bp deletion, TTATACTATCTGTTATTCTTTATT, occurs in a noncoding stretch between the coding sequences of the E3 7.7-kDa and 10.3-kDa proteins.

FIG. 1.

Whole-genome analyses of the HAdV-7 and HAdV-7vac sequences. The genome sequences of the HAdV-7 and HAdV-7vac strains were aligned and analyzed. (A) Dot plot analysis of the aligned sequences as displayed by PipMaker; genome duplication is indicated by short parallel diagonal lines above and below the main line in the upper right portion of the plot. (B) Mismatches and gaps in the HAdV-7vac sequence as displayed by PipMaker, with an example of a gap and a base substitution. Asterisks identify conserved nucleotides. (C) Summary of selected indels in the HAdV-7vac genome compared to the HAdV-7 genome. “Selected” indels are defined as those affecting nine or more nucleotides or changing the protein-coding potential. Note that “gaps” are defined by PipMaker as the total number of nucleotides inserted or deleted, not the number of events.

TABLE 5.

Summary of selected indelsa

| Variation | Effect |

|---|---|

| HAdV-7vac | |

| 19-bp deletion | VA RNA I shortened |

| 24-bp deletion | VA RNA II shortened |

| 12-bp insertion | In-frame addition of QQLQ to L1 52-kDa CDS. |

| 9-bp deletion | In-frame deletion of VTT in hexon CDS |

| 13-bp deletion | Truncates E3 7.7-kDa CDS |

| 24-bp deletion | Occurs in noncoding sequence |

| HAdV-4vac | |

| 3-bp insertion | In-frame addition of A to L4 33-kDa CDS |

| 1-bp insertion | Insertion in non-coding sequence in E3 region |

Indel differences between the vaccine genomes and the prototype genomes are analyzed using PipMaker; several are displayed. For HAdV-7, the Gomen prototype strain is used as a reference instead of the Greider strain due to the availability of the complete sequence for comparative analysis. “Selected”indels are defined as those affecting nine or more nucleotides or changing the protein-coding potential. CDS, coding domain sequences.

FIG. 2.

Detailed alignment of the hexon amino acid sequences of the prototype (HAdV-7) and vaccine (HAdV-7vac) strains. The hexon coding sequences of the two HAdV-7 strains were aligned by CLUSTALX. Seven hypervariable regions, designated HVR1 to -7, were identified in the literature, as discussed in the text, as containing serotype-specific residues. These seven hypervariable regions span most of the hexon epitopes. A VTT deletion in the HAdV-7vac hexon sequence is marked with a rectangular box. *, conserved amino acid; ·, either size or hydropathy is conserved; :, both size and hydropathy are preserved.

These unique genome differences define genome signatures that may be and have been used to develop tools and protocols for molecular diagnostics and to enable molecular surveillance (unpublished data). The genome data are useful for following the molecular forensics of HAdV epidemic outbreaks, identifying the specific genome type and strain, including historical circulating strains.

Example of applying genome data to historical strains: molecular forensics.

As a postscript, limited genome comparisons, due to a paucity of archived Greider sequences, suggest that the Greider strain (also called HAdV-7a), or a similar variant, was used for vaccine development rather than the contemporaneous prototype, the Gomen strain (also called HAdV-7, or prototype). The ITR for the Greider strain (GenBank V00036) contains 4 nucleotides in common with the vaccine strain, which differs from the Gomen strain ITR. Hexons described for several HAdV-7a variants, strain 55142 (GenBank AF065067), strain S-1058 (GenBank AF065066), and strain Kn T96-0620 (GenBank AF065068), have a 100% match with their counterparts in HAdV-7vac (13). In the fiber region, HAdV-7a strain S-1058 (GenBank AF104382) and HAdV-7vac have three mismatches observed in their nucleotide alignments but show 100% identity in their amino acid alignments (13).

Genome duplication.

Genome comparison using the dot plot software PipMaker shows a small duplication that is conserved in both the HAdV-7vac and HAdV-7 genomes (Fig. 1A). This duplication resides in the E3 region and gives rise to the E3 20.1-kDa protein and the 20.6-kDa protein. The 20.1-kDa protein is 10 amino acids shorter than the 20.6-kDa protein. These two proteins share 31% identity. As noted earlier, the E3 transcription unit encodes products that are required to evade the host immune system (29, 56). This duplication may have contributed to the robustness of this circulating HAdV-7 genome type in the period leading up to the initial deployment of the vaccines, as it was the main culprit in the ARD cases versus other circulating HAdVs, HAdV-3, -4, and -21, (47), leading to its use as a vaccine strain. However, the specific functions of these proteins have not been investigated.

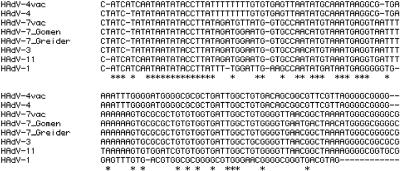

Comparison and analysis of the HAdV-7-related ITRs.

The linear double-stranded DNA genomes of adenoviruses contain ITRs that are located at either end (14) and that are critical to viral development. Contained within this ITR are DNA sequence motifs that are required for viral replication, as well as for gene activation and transcription. One component is the canonical “core” origin of DNA replication (ATAATATACC) that binds the preterminal protein-DNA polymerase complex (51). This core sequence is found in both HAdV-7vac, starting at nucleotide 9, and its prototype, as aligned in Fig. 3. In addition to the virus-encoded DNA pol and pTP, HAdVs also require a set of host cellular factors for efficient replication. These are reflected in the cellular transcription factor DNA-binding motifs contained in the genome, as cataloged in Table 4. Examples include the NFIII/Oct-1 recognition site (TATGCAAATAA). This motif is present in the HAdV-7vac genome; it is also present, albeit with a single base change relative to the vaccine strain, in both prototype strains, Gomen and Greider. The NFI/CTFI recognition site (TGTTATGGTGCCAA) is present in the HAdV-7vac genome starting at nucleotide 26. This sequence, with a 1-base difference from the vaccine genome, is also found in the Gomen and Greider ITRs. In vivo and in vitro studies in the literature note that both NFI and NFIII are required for efficient DNA replication of HAdV (37).

FIG. 3.

Multiple-sequence alignment of ITRs. CLUSTAL X (v. 1.81) was used to align the ITRs of several HAdVs. The vaccine genomes are compared with their corresponding prototypes; species B1 (HAdV-11) and C (HAdV-1) sequences are included as references. Gaps used to optimize alignments are indicated by dashes. Conserved nucleotides presumably involved in genome replication are indicated by asterisks.

The ITR of HAdV-7vac is 136 bp in length. As aligned in Fig. 3, this is in contrast to the 108-bp ITR of the prototypes, e.g., the Gomen strain (40). Up to nucleotide 108, all three (vaccine, Gomen, and Greider) HAdV-7 ITRs are nearly identical, with six nucleotide changes. As noted above, these single-nucleotide polymorphisms also suggest that the vaccine strain is related to the Greider strain (matching at four of the six positions, with the two differences matching neither prototype strain). Beyond 108 bp, the three sequences align well with each other. There are five nucleotide differences, all of which are contained in common in both the vaccine and Greider strains. Additionally, within the first 22 bases, all three strains share identity with fellow species B1 member HAdV-3, as well as with HAdV-4 (but not with HAdV-4vac, as will be discussed below). Beyond these first 22 bases, all three HAdV-7 strains share remarkable identity with each other, as well as with the species B1 member HAdV-3, as shown in Fig. 3.

Comparisons of the E1A 32-kDa protein, penton, hexon, and fiber coding sequences of the vaccine and prototype strains of HAdV-7. (i) E1A 32-kDa coding sequence.

The E1A 32-kDa protein belongs to a set of adenovirus proteins that are expressed early in the infection cycle. The E1A proteins regulate viral and host gene expression by interacting with various members of the host cell transcription machinery. Bioinformatics analysis shows that the E1A 32-kDa protein coding sequences of HAdV7 vaccine and prototype strains had seven nucleotide differences between them. Five of these were synonymous changes, while the other two were nonsynonymous mutations. The nonsynonymous changes resulted in two amino acid substitutions: E57Q and G62E. In addition, there were two insertions, K195 and C196, found in the vaccine strain. The rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations were 19 and 3 per 1,000 bp, respectively (Table 6). These low substitution rates (compared to similar rates in the penton, hexon, and fiber genes) underscore the conserved nature of the E1A coding sequences across the various adenovirus species. The E1A 32-kDa coding sequence appears to be under a strong functional constraint and thus does not seem to tolerate high rates of substitution.

TABLE 6.

Substitution rates in selected HAdV-7vac coding sequencesa

| Gene | Rate

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Synonymous | Nonsynonymous | |

| E1A 32-kDa protein | 19 | 3 |

| Penton | 21 | 7 |

| Hexon | 101 | 13 |

| Fiber | 12 | 4 |

Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software was used to calculate the synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates in the coding sequences of the E1A 32-kDa protein, penton, hexon, and fiber genes of the HAdV-7vac genome. These are important determinants of tropism and infection. They are aligned with their homologs in HAdV-7 (Gomen strain). The rates are calculated as the number of substitutions per 1,000 bp.

(ii) Hexon coding sequence.

The adenovirus capsid comprises three proteins: hexon, fiber, and penton. Of these, hexon proteins comprise roughly 60% of the capsid mass. Each hexon monomer is formed as two eight-stranded, antiparallel β-barrels and a set of loops (42). Comparative studies of several adenovirus hexon coding sequences found that while the β-barrels are conserved, maximum variation exists in the loops L1 and L2 (12). It has been documented in the literature that seven hypervariable regions identified within these loops (displayed in Fig. 2) account for 99% of the serotype-specific variations (12). Most of the antibodies against the hexon in an adenoviral infection are directed against epitopes within these seven hypervariable regions (12). A comparison of the hexon coding sequences from the HAdV-7 and -7vac genomes identifies 67 synonymous and 28 nonsynonymous substitutions. The overall rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions are 101 and 13 changes per 1,000 bp. The nonsynonymous changes lead to substitutions in 25 amino acid positions. In addition to the amino acid substitutions, there is a three-amino-acid (VTT) deletion in hypervariable region 1 of the vaccine strain, as noted in Fig. 2. The hexon proteins of HAdV-7 and -7vac are 97% identical at the amino acid level. Interestingly, most of the amino acid substitutions (23 out of 25) in HAdV-7vac occur within the seven hypervariable regions in loops L1 and L2 (Fig. 2), while the synonymous substitutions are found in the conserved regions of the hexon coding sequence. Presumably, mutations that are positively selected confer a survival advantage (20). The concentration of nonsynonymous mutations in the hypervariable regions indicates that loops L1 and L2 are sites of positive selection. This may not be surprising, given that L1 and L2 contain most of the hexon epitopes recognized by the host immune system. Any change in the amino acid sequences of these loops may result in antigenic drift, allowing the virus to evade the host's immune response. This observation may have relevance in vaccine design.

(iii) Penton coding sequence.

The penton protein is found at the vertices of the adenovirus capsid. It serves as the attachment site of the fiber trimer and plays a role in virus internalization (46, 55). The penton proteins of the prototype and vaccine strains are 98% identical at the nucleotide level and 92% at the amino acid level. There are a total of 21 synonymous and 7 nonsynonymous substitutions. The overall rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous changes are 54 and 6 per 1,000 bp, respectively (Table 6). The effects of these mutations are difficult to predict, since the structural and functional domains of the penton have yet to be determined.

(iv) Fiber coding sequence.

The adenovirus fiber protrudes from the vertices of the capsid and is responsible for the virus binding to host cells (46). The fiber coding sequences of HAdV-7 and -7vac are 99% identical, with three synonymous and three nonsynonymous substitutions. The overall rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions are, respectively, 12 and 4 changes per 1,000 bp (Table 6). Analogous to the E1A 32-kDa protein, these low rates of substitution in the fiber coding sequence suggest a strong functional constraint on the protein. The substitutions result in the following amino acid changes: A85T, D128N, and T142R. Of these, the first two changes occur in the fiber “shaft,” while the third occurs in the “knob.” Importantly, these mutations are also present in the genome of a recent field isolate of HAdV-7 and are therefore unlikely to disrupt the host cell binding process (unpublished data).

A recently reported different HAdV-7 vaccine strain from China.

The sequence of a second HAdV-7vac strain, apparently in use in China, was submitted by X. Jiang et al. (GenBank AY495969). As it is unpublished, a full comparison is not available. Based on the GenBank data and PipMaker analysis, this vaccine strain has 626 mismatches and 352 gaps compared to the HAdV-7 prototype. The most important indel appears to be a 237-bp insertion in the Chinese vaccine genome sequence that abolishes the L1 52-kDa protein coding sequence. Since this protein serves in the scaffolding for the capsid (23), its absence may indicate an attenuation of the live virus. The two HAdV-7vac genomes have 17 mismatches and 274 gaps between them. Differences in the two vaccine genomes are likely a reflection of the circulating genome types that were used in the development of different versions of the vaccine in China and the United States.

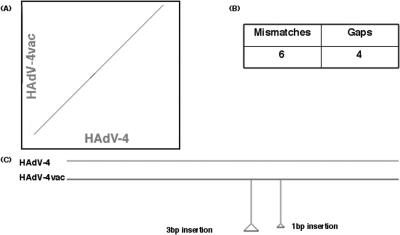

HAdV-4 and HAdV-4vac sequence comparison.

With this newly characterized reference sequence, the HAdV-4vac genome can be compared to its prototype and presumed progenitor, HAdV-4. These HAdV-4 genomes share close identity with respect to nucleotide sequences, as seen in the dot blot analysis with PipMaker (Fig. 4). HAdV-4vac has six mismatches and four gaps compared to HAdV-4. A 3-bp in-frame insertion results in the addition of a single amino acid, A128, to the amino acid sequence of the L4 33-kDa protein. No function has been assigned to the L4 33-kDa protein, so it is difficult to determine what effect such an insertion may have. A 1-bp insertion occurs in the noncoding region of the E3 transcriptional unit. Such low rates of substitution and indel events suggest strongly that the vaccine strain was based on the prevailing and circulating field strain at the time. During the preparation of this report and after the submission of the reported sequence to GenBank, another genome sequence of HAdV-4vac was published (26). This strain was also resuscitated from a Wyeth-Lederle Laboratories vaccine tablet. Its sequence corroborates the sequence reported here; it differs from this sequence by one nucleotide substitution (T:G at position 1971) out of 35,994 nucleotides. Reexamination of the raw data suggests that this may be a true single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rather than a sequencing error. Additionally, the 37 coding sequences reported earlier (26) are a subset of the 51 coding sequences in this report.

FIG. 4.

Whole-genome analyses of HAdV-4 and HAdV-4vac sequences. The genome sequences of HAdV-4 and HAdV-4vac strains were aligned and analyzed. (A) Dot plot of the aligned sequences as displayed by PipMaker. (B) Mismatches and gaps in the HAdV-4vac sequence as noted by PipMaker. (C) Summary of selected indels in the HAdV-4vac genome compared to the HAdV-4 sequence. “Selected” indels are defined as those affecting nine or more nucleotides or changing the protein-coding potential. Note that “gaps” are defined by PipMaker as the total number of nucleotides inserted or deleted, not the number of events.

Comparison and analysis of the HAdV-4-related ITRs: genome recombination.

As mentioned earlier, there are intriguing similarities and differences between the ITRs of HAdV-4vac and its prototype counterpart. These are in line with one recent key observation that the HAdV genomes appear to exchange sequences with each other, particularly the species B1 members (unpublished data). This may also be seen in the temporal progression of genome variants of strains isolated from patients (field strains). As the HAdV-4 prototype strain dates from the early 1950s and the vaccine strain, presumably derived from the then-current circulating field strain, dates from the mid- to late 1950s, recombination events are likely retained if they confer selective advantage. This may be borne out in the analysis of the ITRs, particularly those of recent field strains (unpublished data), and are reported here for the vaccine and prototype genomes.

The terminus of HAdV-4vac contains a CATCATCAA sequence, starting at nucleotide 1, which is present in species C serotypes, represented by HAdV-1 (Fig. 3). Curiously, unlike the HAdV-4vac terminus, HAdV-4 has a CTATCTATA motif in the terminus (39). This sequence motif is identical to the corresponding sequences in several species B1 members, as represented by HAdV-3, -7, and -7vac. Historically, these species B1 serotypes were and are associated with ARD. The species C serotypes are associated historically with childhood and milder respiratory diseases (8). The divergent termini of the nearly identical genomes are indicative of a recombination event between the species E serotype and species B1 and/or species C. Interspecies recombination between HAdVs has not been commonly noted in the literature. Recombination events may increase the replicating efficiency and robustness of the ensuing recombinant strain (35).

In both genomes, these divergent 9 nucleotides are followed by the canonical sequences that are conserved across all sequenced HAdV genomes from nucleotides 10 to 25. After this, with the exception of four nucleotide differences, both vaccine and prototype genomes have identical sequences stretching to the end of the 116-bp ITR. These differences are present in the vaccine genome as follows: “deletion” of a T at nucleotide 2, insertion of an A at nucleotide 5, and a dinucleotide substitution (CA for AT) at positions 7 and 8. The identical sequences include a unique string of eight T nucleotides from positions 22 to 29 in both vaccine and prototype genomes. The significance of these similarities and differences are not yet understood; however, they may have relevance in serotype and/or pathogenicity evolution, as well as infectiousness, as the reemergent HAdV-4 variants are the current predominant agent of ARD (7). This, in turn, has relevance for vaccine redevelopment. This particular genome sequence represents an important site for the development of reagents for molecular diagnostics, yielding a unique genome signature for prototype, vaccine, and current epidemic field strains of HAdV-4 (unpublished data).

As mentioned earlier, HAdVs require certain host cellular factors for efficient viral replication. Cellular transcription factor DNA-binding motifs for the HAdV-4vac genome are noted in Table 2. The HAdV-4vac genome contains an NFIII/Oct-1 recognition site (TATGCAAATAA) at bp 41 to 51, which is also found in the prototype genome, as well as all other HAdVs. However, it contains a unique Sp1 binding site (GGGGATGGGGC) at bp 65 to 75, again found in the prototype genome but not other HAdV ITRs. Also, particularly noteworthy, the NFI/CTFI recognition site is not present in either HAdV-4 genome but is present in all other HAdVs characterized to date. This is consistent with earlier work reporting the ITRs and DNA sequence motifs required for HAdV-4 replication (22, 39). In contrast, reports in the literature show that HAdVs require both NFI and NFIII for efficient DNA replication (37).

Comparisons of the E1A 32-kDa protein and penton, hexon, and fiber proteins of the vaccine and prototype strains of HAdV-4: an example of molecular forensics.

In contrast to the HAdV-7 genomes described here, the HAdV-4 genomes have very few differences, identifying the then-circulating field strain as the HAdV-4 prototype described in 1953 (25). This is an example of the molecular forensics possible using genome bioinformatics and genomes as gold standards.

The E1A 32-kDa protein and penton and fiber protein coding sequences of the vaccine and prototype strains are nearly 100% identical at the nucleotide level. The hexon coding sequence has a single synonymous A-to-T transversion at position 1997. This is a synonymous mutation, as the hexons are 100% identical at the amino acid level.

Nonattenuation of vaccine strains.

Live attenuated viruses have been used routinely for vaccination against several viral pathogens. For example, vaccines against polio, measles, mumps, rubella, and influenza are formulated from live, attenuated viral strains (1). No observations or studies were reported showing whether these HAdV strains were attenuated for virulence. This report is the first comparative examination of the two vaccine strain genome sequences with the prototype genomes. The comparative analyses, using whole-genome dot plot comparisons via PipMaker and also examining the coding structures, suggest that neither vaccine strain appears to have undergone any mutation or recombination events that would lead to attenuated virulence. While the HAdV-4vac strain sequence is nearly identical to that of its prototype, the HAdV-7vac sequence has five major indels compared to the HAdV-7 (Gomen) prototype. Three of these indels either shorten or abolish the coding sequences of the VA RNAs and the E3 7.7-kDa protein. The VA RNA and the E3 coding sequences are required by the virus to counter the host's immune system, thus raising the possibility that any disruption in these coding sequences may attenuate the virulence of the virus. However, all of these indels are also present in a current and epidemic field strain isolate of HAdV-7 (unpublished data). Therefore, it is unlikely that these differences lead to an attenuation of the virus. In contrast, a second HAdV-7vac strain (GenBank AY495969), used and sequenced in China, lacks the coding sequence for the L1 52-kDa scaffold protein. This deletion may lead to attenuation.

The method of HAdV immunization is to administer oral doses to produce an asymptomatic infection that leads to seroconversion. Numerous safety and efficacy studies have indicated that this asymptomatic gastrointestinal infection results in between 70 and 80% of those vaccinated seroconverting to HAdV-4 and HAdV-7 (50, 53, 54). Since HAdV-4 and -7 are rarely associated with gastrointestinal disease in adults, likely due to the fact that these serotypes lack tropism for the intestinal epithelial lining, this appears to be an effective and safe immunization strategy (47). However, the recent isolation of an apparent B1 species member, HAdV-50, from a gastrointestinal infection in a HIV-infected individual may elicit concern (16). This additional tropism may have implications, as data are accumulating for genome recombination between HAdV serotypes and species (unpublished data). As an academic point, recombination events between the ingested vaccine strains and other coinfecting adenovirus strains could give rise to new strains and serotypes that have altered infectious and pathogenic pathways.

Vaccine efficacy and genome evolution.

It is important to note that the vaccines have proven very effective for countering HAdV strains circulating at the time of vaccine deployment. Given the evolving nature of the genomes, as noted in the data presented here, continued monitoring will ensure continued efficacy of the vaccines.

An experimental approach to the issue of whether the vaccines would protect against current and future circulating strains can be followed by using archived sera of vaccinated individuals and current HAdV isolates. This complements the approach of hypothesizing the predicted effects of antibodies on presumed altered coat proteins, as noted by the bioinformatics.

The adenovirus prototype strains were isolated approximately 50 years ago, ca. 1953; the vaccine strains were derived from that era's circulating epidemic field strains ca. the mid- to late 1950s. Limited sequence comparisons, e.g., hexon coding regions, between the vaccine strains and the present-day circulating strains reveal significant differences (13). Because of this, one might hypothesize that the neutralizing antibodies directed against the outer coat proteins of the 1950s era vaccine strains may not protect against current and future epidemic field strains. Antibodies are generated against the outer coat proteins, which include the fiber, hexon, and penton proteins. In particular, the hexon amino acid sequence has seven major hypervariable regions that contain most of the serotype-specific epitopes (12), as shown in Fig. 2. A comparison of the hexon sequences of the vaccine, prototype, and current field strains identifies phylogenetic relationships among these strains that may be used as predictors of vaccine efficacy (unpublished data). The HAdV-7vac hexon is closer to its counterpart in the HAdV-7 field strain than it is to the HAdV-7 prototype hexon. The hexon of HAdV-7vac also has a higher level of similarity (99% identity at the amino acid level) to its homologs in the HAdV-7 genome types, HAdV-7a and -7d (data not shown), than it does to the hexon of the HAdV-7 prototype. Given this difference in the levels of conservation between the vaccine strain hexon and its homologs in the other HAdV-7 genome types, it is possible that the vaccine strain affords various degrees of protection against different genome types of HAdV-7. In contrast, the hexon of HAdV-4vac differs greatly from its homologs in the current field isolates of HAdV-4. This suggests that while the HAdV-7vac strain may prove to be efficacious in preventing an HAdV-7 infection, the HAdV-4vac strain may offer a lower degree of protection against the current evolving epidemic HAdV-4 field strains. Continued monitoring will ensure continued efficacy.

Despite these genome differences between the vaccines and current field isolates, it must be pointed out that strong evidence exists to suggest that these HAdV-4 and HAdV-7 field strains were already in circulation at least as early as the 1990s, when vaccination was still occurring in military trainees (7). Studies during this time showed effectiveness of the vaccine, despite these differences betrween vaccine strains and circulating strains, with unvaccinated recruits being 28 times more likely to be positive for HAdV-4 or HAdV-7 (21).

Nevertheless, epidemiological studies indicate that the global prevalence patterns of HAdV genome types do shift over time and geographical region (10, 18, 27, 28). This, along with the genome data presented here, suggests that it is advisable and prudent to design HAdV vaccines from strains that offer the greatest protection against the prevalent genome type and to continue surveillance and vaccine redevelopment with periodic evaluations of current field strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Lou Gibson (Virapur, Inc., San Diego, CA) for virus growth and DNA preparation and Steve Carlisle (Commonwealth Biotechnology, Inc., Richmond, VA) for DNA-sequencing support. We also thank James Clark, GMU, for comments, analyses, and illustrations.

Research support was provided through a grant (DAMD17-03-2-0089) from the U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command (USAMRMC). Partial support was also provided through the Epidemic Outbreak Surveillance Project (EOS), funded through HQ USAF Surgeon General Office (SGR) and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private ones of the authors and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the Department of Defense.

During the course of this work, the EOS Consortium included the following members: Col. Peter F. Demitry (USAF/SGR) and Lt. Col. Theresa Lynn Difato (USAF/SGR) (sponsors); Maj. Robb K. Rowley (USAF/SGR), Lt. Col. Eric H. Hanson (USAF/SGR), Rosana R. Holliday (USAF/SGR [contractor]), and Clark Tibbetts (The George Washington University [IPA]) (Executive Board and Principal Investigators); Jerry Diao (USAF/SGR [contractor]), Curtis White (Lackland AFB, TX), Elizabeth A. Walter (Texas A&M University—San Antonio [IPA]), Russell P. Kruzelock (Virginia Tech [IPA]), Jennifer Weller (George Mason University [IPA]), Donald Seto (George Mason University [IPA]), David A. Stenger (Naval Research Laboratory), and Maj. Brian K. Agan (Wilford Hall Medical Center) (Operational Board and Senior Scientists); CDR Kevin Russell (Navy Health Research Center), David Metzgar (Navy Health Research Center), Jianguo Wu (Navy Health Research Center), and Ted Hadfield (Armed Forces Institute of Pathology) (Technical Advisors and Collaborating Investigators); Anjan Purkayastha (George Mason University), Jing Su (George Mason University), Baochuan Lin (Naval Research Laboratory), Dzung Thach (Naval Research Laboratory), Gary J. Vora (Naval Research Laboratory), Zheng Wang (Naval Research Laboratory), Chris Olsen (USAF/SGR [contractor]), John Gomez (Lackland AFB, TX), Jose J. Santiago (Lackland AFB, TX), Margaret Jesse (Lackland AFB, TX), Sue A. Worthy (Lackland AFB, TX), Sue Ditty (Armed Forces Institute of Pathology), John McGraw (Armed Forces Institute of Pathology), Robert Crawford (Armed Forces Institute of Pathology), TSgt. Michael Jenkins (Wilford Hall Medical Center), and Linda Canas (Air Force Institute for Operational Health) (Research and Clinical Staff); and Cheryl J. James (USAF/SGR [contractor]), Kathy Ward (USAF/SGR [contractor]), Kenya Grant (USAF/SGR [contractor]), and Kindra Nix (Lackland AFB, TX) (Operations Support Staff).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ada, G. 1997. Overview of vaccines. Mol. Biotechnol. 8:123-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barraza, E. M., S. L. Ludwig, J. C. Gaydos, and J. F. Brundage. 1999. Reemergence of adenovirus type 4 acute respiratory disease in military trainees: report of an outbreak during a lapse in vaccination. J. Infect. Dis. 179:1531-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behr, M. A., M. A. Wilson, W. P. Gill, H. Salamon, G. K. Schoolnik, S. Rane, and P. M. Small. 1999. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science 284:1520-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berriman, M., and K. Rutherford. 2003. Viewing and annotating sequence data with Artemis. Brief Bioinform. 4:124-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Besemer, J., and M. Borodovsky. 1999. Heuristic approach to deriving models for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:3911-3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blasiole, D. A., D. Metzgar, L. T. Daum, M. A. K. Ryan, J. Wu, C. Wills, C. T. Le, N. E. Freed, C. J. Hansen, G. C. Gray, and K. L. Russell. 2004. Molecular analysis of adenovirus isolates from vaccinated and unvaccinated young adults. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1686-1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buescher, E. L. 1967. Respiratory disease and the adenoviruses. Med. Clin. N. Am. 51:769-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cockle, P. J., S. V. Gordon, A. Lalvani, B. M. Buddle, R. G. Hewinson, and H. M. Vordermeier. 2002. Identification of novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens with potential as diagnostic reagents or subunit vaccine candidates by comparative genomics. Infect. Immun. 70:6996-7003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper, R. J., A. S. Bailey, R. Killough, and S. J. Richmond. 1993. Genome analysis of adenovirus 4 isolated over a six year period. J. Med. Virol. 39:62-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couch, R. B., R. M. Chanock, T. R. Cate, D. J. Lang, V. Knight, and R. J. Huebner. 1963. Immunization with types 4 and 7 adenovirus by selective infection of the intestinal tract. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 88(Suppl.):394-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crawford-Miksza, L., and D. P. Schnurr. 1996. Analysis of 15 adenovirus hexon proteins reveals the location and structure of seven hypervariable regions containing serotype-specific residues. J. Virol. 70:1836-1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crawford-Miksza, L. K., R. N. Nang, and D. P. Schnurr. 1999. Strain variation in adenovirus serotypes 4 and 7a causing acute respiratory disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1107-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dan, A., P. Elo, B. Harrach, Z. Zadori, and M. Benko. 2001. Four new inverted terminal repeat sequences from bovine adenoviruses reveal striking differences in the length and content of the ITRs. Virus Genes 22:175-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davison, A. J., M. Benko, and B. Harrach. 2003. Genetic content and evolution of adenoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 84:2895-2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Jong, J. C., A. G. Wermenbol, M. W. Verweij-Uijterwaal, K. W. Slaterus, P. Wertheim-Van Dillen, G. J. Van Doornum, S. H. Khoo, and J. C. Hierholzer. 1999. Adenoviruses from human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals, including two strains that represent new candidate serotypes Ad50 and Ad51 of species B1 and D, respectively. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3940-3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dudding, B. A., S. C. Wagner, J. A. Zeller, J. T. Gmelich, G. R. French, and F. H. Top, Jr. 1972. Fatal pneumonia associated with adenovirus type 7 in three military trainees. N. Engl. J. Med. 286:1289-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erdman, D. D., W. Xu, S. I. Gerber, G. C. Gray, D. Schnurr, A. E. Kajon, and L. J. Anderson. 2002. Molecular epidemiology of adenovirus type 7 in the United States, 1966-2000. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:269-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaydos, C. A., and J. C. Gaydos. 1995. Adenovirus vaccines in the U.S. military. Mil. Med. 160:300-304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graur, D., and W.-H. Li. 2000. Fundamentals of molecular evolution, 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates Inc., Sunderland, Mass.

- 21.Gray, G. C., P. R. Goswami, M. D. Malasig, A. W. Hawksworth, D. H. Trump, M. A. Ryan, and D. P. Schnurr. 2000. Adult adenovirus infections: loss of orphaned vaccines precipitates military respiratory disease epidemics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:663-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris, M. P., and R. T. Hay. 1988. DNA sequences required for the initiation of adenovirus type 4 DNA replication in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 201:57-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasson, T. B., P. D. Soloway, D. A. Ornelles, W. Doerfler, and T. Shenk. 1989. Adenovirus L1 52- and 55-kilodalton proteins are required for assembly of virions. J. Virol. 63:3612-3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilleman, M. R., R. A. Stallones, R. L. Gauld, M. S. Warfield, and S. A. Anderson. 1956. Prevention of acute respiratory illness in recruits by adenovirus (RI-APC-ARD) vaccine. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 92:377-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hilleman, M. R., and J. H. Werner. 1954. Recovery of new agent from patients with acute respiratory illness. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 85:183-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs, S. C., A. J. Davison, S. Carr, A. M. Bennett, R. Phillpotts, and G. W. Wilkinson. 2004. Characterization and manipulation of the human adenovirus 4 genome. J. Gen. Virol. 85:3361-3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kajon, A., and G. Wadell. 1994. Genome analysis of South American adenovirus strains of serotype 7 collected over a 7-year period. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2321-2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kajon, A. E., and G. Wadell. 1992. Characterization of adenovirus genome type 7h: analysis of its relationship to other members of serotype 7. Intervirology 33:86-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kajon, A. E., W. Xu, and D. D. Erdman. 2005. Sequence polymorphism in the E3 7.7K ORF of subspecies B1 human adenoviruses. Virus Res. 107:11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, I. B. Jakobsen, and M. Nei. 2001. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics 17:1244-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lauer, K. P., I. Llorente, E. Blair, J. Seto, V. Krasnov, A. Purkayastha, S. E. Ditty, T. L. Hadfield, C. Buck, C. Tibbetts, and D. Seto. 2004. Natural variation among human adenoviruses: genome sequence and annotation of human adenovirus serotype 1. J. Gen. Virol. 85:2615-2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le, C. T., G. C. Gray, and S. K. Poddar. 2001. A modified rapid method of nucleic acid isolation from suspension of matured virus applied in restriction analysis of DNA from an adenovirus prototype strain and a patient isolate. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:571-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, S.-G., and P. O. Hung. 1993. Vaccines for control of respiratory disease caused by adenoviruses. Rev. Med. Virol. 3:209-216. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levin, S., J. Dietrich, and J. Guillory. 1967. Fatal nonbacterial pneumonia associated with Adenovirus type 4. Occurrence in an adult. JAMA 201:975-977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu, H., J. H. Naismith, and R. T. Hay. 2003. Adenovirus DNA replication, p. 131-164. In W. Doerfler and P. Bohm (ed.), Adenoviruses: model and vectors in virus-host interactions. Springer, Berlin, Germany.

- 36.Mathews, M. B., and T. Shenk. 1991. Adenovirus virus-associated RNA and translation control. J. Virol. 65:5657-5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mul, Y. M., C. P. Verrijzer, and P. C. van der Vliet. 1990. Transcription factors NFI and NFIII/oct-1 function independently, employing different mechanisms to enhance adenovirus DNA replication. J. Virol. 64:5510-5518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nei, M., and T. Gojobori. 1986. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 3:418-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Purkayastha, A., S. E. Ditty, J. Su, J. McGraw, T. L. Hadfield, C. Tibbetts, and D. Seto. 2005. Genomic and bioinformatics analysis of HAdV-4, a human adenovirus causing acute respiratory disease. Implications for gene therapy and vaccine vector development. J. Virol. 79:2559-2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purkayastha, A., J. Su, S. Carlisle, C. Tibbetts, and D. Seto. 2005. Genomic and bioinformatics analysis of HAdV-7, a human adenovirus of species B1 that causes acute respiratory disease: implications for vector development in human gene therapy. Virology 332:114-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowe, W. P., R. J. Huebner, L. K. Gilmore, R. H. Parrot, and T. G. Ward. 1953. Isolation of a cytopathic agent from human adenoids undergoing spontaneous degradation in tissue culture. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 84:570-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rux, J. J., P. R. Kuser, and R. M. Burnett. 2003. Structural and phylogenetic analysis of adenovirus hexons by use of high-resolution X-ray crystallographic, molecular modeling, and sequence-based methods. J. Virol. 77:9553-9566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryan, M., G. Gray, A. Hawksworth, M. Malasig, M. Hudspeth, and S. Poddar. 2000. The Naval Health Research Center Respiratory Disease Laboratory. Mil. Med. 165:32-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryan, M. A. K., G. C. Gray, M. D. Malasig, L. N. Binn, L. V. Asher, D. Cute, S. C. Kehl, B. E. Dunn, and A. J. Yund. 2001. Two fatal cases of adenovirus-related illness in previously healthy young adults—Illinois, 2000. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 50:553-555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.San Martin, C., and R. M. Burnett. 2003. Structural studies on adenoviruses, p. 57-94. In W. Doerfler and P. Bohm (ed.), Adenoviruses: model and vectors in virus-host interactions. Springer, Berlin, Germany.

- 47.Schmitz, H., R. Wigand, and W. Heinrich. 1983. Worldwide epidemiology of human adenovirus infections. Am. J. Epidemiol. 117:455-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz, S., Z. Zhang, K. A. Frazer, A. Smit, C. Riemer, J. Bouck, R. Gibbs, R. Hardison, and W. Miller. 2000. PipMaker—a web server for aligning two genomic DNA sequences. Genome. Res. 10:577-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sugarman, B., B. M. Hutchins, D. L. McAllister, F. Lu, and B. K. Thomas. 2003. The complete nucleic acid sequence of the adenovirus type 5 reference material (ARM) genome. Bioprocessing 2003(Sept./Oct.):27-32.

- 50.Takafuji, E. T., J. C. Gaydos, R. G. Allen, and F. H. Top, Jr. 1979. Simultaneous administration of live, enteric-coated adenovirus types 4, 7 and 21 vaccines: safety and immunogenicity. J. Infect. Dis. 140:48-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Temperley, S. M., and R. T. Hay. 1992. Recognition of the adenovirus type 2 origin of DNA replication by the virally encoded DNA polymerase and preterminal proteins. EMBO J. 11:761-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Top, F. H., Jr., E. L. Buescher, W. H. Bancroft, and P. K. Russell. 1971. Immunization with live types 7 and 4 adenovirus vaccines. II. Antibody response and protective effect against acute respiratory disease due to adenovirus type 7. J. Infect. Dis. 124:155-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Top, F. H., Jr., R. A. Grossman, P. J. Bartelloni, H. E. Segal, B. A. Dudding, P. K. Russell, and E. L. Buescher. 1971. Immunization with live types 7 and 4 adenovirus vaccines. I. Safety, infectivity, antigenicity, and potency of adenovirus type 7 vaccine in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 124:148-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wickham, T. J., P. Mathias, D. A. Cheresh, and G. R. Nemerow. 1993. Integrins alpha v beta 3 and alpha v beta 5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell 73:309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wold, W. S., and L. R. Gooding. 1991. Region E3 of adenovirus: a cassette of genes involved in host immunosurveillance and virus-cell interactions. Virology 184:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeh, R. F., L. P. Lim, and C. B. Burge. 2001. Computational inference of homologous gene structures in the human genome. Genome Res. 11:803-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]