Abstract

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) regulates transcriptional responses via activation of cytoplasmic effector proteins termed Smads. Following their phosphorylation by the type I TGFβ receptor, Smads form oligomers and translocate to the nucleus where they activate the transcription of TGFβ target genes in cooperation with nuclear cofactors and coactivators. In the present study, we have undertaken a deletion analysis of human Smad3 protein in order to characterize domains that are essential for transcriptional activation in mammalian cells. With this analysis, we showed that Smad3 contains two domains with transcriptional activation function: the MH2 domain and a second middle domain that includes the linker region and the first two β strands of the MH2 domain. Using a protein–protein interaction assay based on biotinylation in vivo, we were able to show that a Smad3 protein bearing an internal deletion in the middle transactivation domain is characterized by normal oligomerization and receptor activation properties. However, this mutant has reduced transactivation capacity on synthetic or natural promoters and is unable to interact physically and functionally with the histone acetyltransferase p/CAF. The loss of interaction with p/CAF or other coactivators could account, at least in part, for the reduced transactivation capacity of this Smad3 mutant. Our data support an essential role of the previously uncharacterized middle region of Smad3 for nuclear functions, such as transcriptional activation and interaction with coactivators.

INTRODUCTION

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) controls key biological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and extracellular matrix production among others (1,2). All members of the TGFβ family of multifunctional ligands signal via heteromeric complexes of type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors. Following binding of ligands to the receptors, the activated type I receptors are phosphorylated by the constitutively active type II receptor kinase and activate, by phosphorylation, intracellular effectors called receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads) (3–7). Although Smad2 and Smad3 act downstream of TGFβ and activin receptors, Smad1, Smad5 and Smad8 are specifically regulated by the BMP receptors (5,6). Following activation, R-Smads translocate to the nucleus as homo- or hetero-oligomers, where they bind to promoters of target genes and activate their transcription in cooperation with transcriptional cofactors and coactivators (3–7).

Smads have two conserved functional domains, the N-terminal Mad Homology 1 (MH1) and the C-terminal MH2 domains, which are separated by a non-conserved linker domain. Crystallographic data have shown that the MH1 domain of Smads is globular and compact and is composed of four α-helices, six short β-sheets, five loops and a β-hairpin (8). The β-hairpin structure is involved in DNA binding by contacting specific nucleotides present in Smad DNA-binding elements (SBEs) composed of the tetranucleotide GTCT (8). The MH1 domain also contains a signal that mediates the nuclear translocation of Smads and negatively regulates the functions of the MH2 domain (9–11).

The MH2 domain is indispensable for Smad homo- and hetero-oligomerization, as well as the recognition and phosphorylation of R-Smads by their type I receptors (3–7). Crystallographic studies using purified Smad2, Smad3 or Smad4 MH2 domains revealed the formation of a globular structure with a β-sandwich core element consisting of twisted antiparallel β-sheets of five and six strands each capped by a three-helical bundle (helices H3, H4 and H5) at one end and a helix–loop region (loops L1, L2, L3 and helix H1) at the opposite end (12–14). Smad homo- or hetero-oligomerization is mediated by specific contacts between amino acids of the loop–helix region of one MH2 subunit and the α helical bundle of another partner subunit in the trimer (12). The MH2 trimer was found to have the shape of a disc with the linker region emerging from one side and the C-terminal region from the other. Most of the structural elements of the MH2 domain as well as its overall fold are conserved among R-Smads. Importantly, point mutations in highly conserved amino acid residues either in the loop/helix region or the three-helix bundle of the MH2 domain of Smad4 that disrupt Smad4 oligomerization have been described in cancer patients (12,15).

In the present study, we have investigated the role of the middle linker region of Smad3, in various functions characteristic of the R-smad (receptor-regulated Smad) family, including ligand-stimulated phosphorylation, oligomerization, nuclear accumulation and transcriptional activation of TGFβ target promoters. Our findings indicate that the linker region of Smad3 harbors a potent, ligand-independent, transactivation domain that has the ability to interact with coactivators and by synergizing with the C-terminal MH2 transactivation domain controls the overall transactivation function of the protein in the nucleus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructions

Plasmids expressing the wild-type human Smad3 (amino acids 1–424) or its mutated forms 1–130, 1–230, 1–248, 130–424, 230–424, 130–230, 130–248, 143–248, 172–248, 201–248 and 230–248 were constructed by PCR amplification using 5′ and 3′ primers, specifically designed to allow the cloning of the amplified fragments into the mammalian expression vector pCDNA1amp-6myc (16) at the EcoRI and NotI sites in frame with a 6myc epitope tag at the N-terminus. Each cDNA was excised from the pCDNA1amp-6myc vector and was subcloned into the pBXG1 expression vector in frame with the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of the yeast transactivator GAL4 (amino acids 1–147). The Smad3 mutant bearing the internal deletion of amino acids 200–230 was constructed by overlap extension PCR (17). The amplified fragment corresponding to the Smad3 internal deletion mutant was cloned first into the pCDNA1amp-6myc vector and then subcloned into the pBXG1 vector as described above. The sequences of all primers used in the PCR amplifications are available upon request. All mutant Smad3 cDNAs were sequenced for verification and found to contain the proper mutation. For the construction of the yeast expression vectors, the wild-type Smad3 and the Smad3 143–248 mutant were cloned into the pAS2-1 vector (Clontech) in frame with the DBD of GAL4. Plasmid pBS-myc-BirA bearing the myc-tagged bacterial biotin ligase BirA was a generous gift from Dr John Strouboulis (Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands). The BirA gene was subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pCDNA3 (Invitrogen Life Technologies). The expression vector pCDNA3-Bio was constructed by inserting a double-stranded oligonucleotide linker with BamHI and EcoRI overhangs coding for the 23 amino acids biotinylation tag (18) into the corresponding sites of pCDNA3. Wild-type and mutant forms of Smad3 were tagged for biotinylation by subcloning their cDNAs into the pCDNA3-Bio vector in frame with the biotinylation tag. The expression vector pCDNA3-flag-p/CAF was kindly offered by Dr I. Talianidis (IMBB-FORTH, Heraklion).

Cell culture and treatments

COS-7, HepG2, NIH3T3, HEK-293T, JEG-3 and MDA-MB-468 cells were cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin–streptomycin, in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. Treatment with TGFβ1 was for 24 h with a concentration of 200 pM. For the protein stability experiments, transiently transfected HepG2 cells were treated with 50 μg/ml of cycloheximide for different time periods and collected for immunoblotting.

Transient transfections and reporter assays

Transactivation assays were performed by the calcium phosphate co-precipitation method in 6-well plates using 1 μg of a reporter plasmid and 1–2 μg of expression vectors per well. β-galactosidase and luciferase assays were performed using well-established protocols.

Indirect immunofluorescence

Transfected COS-7 cells were seeded on glass coverslips, coated with 0.1% gelatin. Cells were washed three times on a slow rotating platform with phosphate-buffered saline+/+ (PBS+/+) (PBS plus 0.9 mM CaCl2 and 0.5 mM MgCl2) and fixed with 3% p-formaldehyde in PBS+/+ for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were washed three times with PBS+/+ and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in buffer 1 (10× buffer 1: 137 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM Na2HPO4, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, 5.5 mM glucose, 4 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA and 20 mM MES, pH 6.0–6.5) for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were washed three times with PBS+/+, blocked with PBS+/+/1.5% FBS and incubated with anti-myc (9E10), 1:200 dilution, in PBS+/+/1.5% FBS for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed three times with PBS+/+/1.5% FBS and incubated with the secondary antibody [goat anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), 1:50 dilution in PBS+/+/1.5% FBS] for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. Cells were washed three times with PBS+/+ in the dark and mounted on glass slides using mounting solution (1:1 glycerol/PBS). Cells were observed using a Leica SP confocal fluorescent microscope.

In vivo biotinylation and protein–protein interaction assay

For the in vivo biotinylation assay (18), 7.5 × 105 of HEK-293T cells were transfected in 10 cm dishes with 5 μg of pCDNA3-Bio-Smad3 expression vectors (wild-type or mutant forms) in the presence or in the absence of 7.5 μg of pCDNA3-BirA vector expressing the bacterial biotin ligase BirA. For protein–protein interaction assays, HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with the above plasmids along with 7.5 μg of expression vectors pCDNA3-6myc-Smad2, pCDNA3-6myc-Smad3, pCDNA3-6myc-Smad4 or pCDNA3-flag-p/CAF in the presence or in the absence of an expression vector for a constitutively active form of the type I TGFβ receptor (ALK5-ca, 7.5 μg). Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 1% Triton X-100) and allowed to interact with streptavidin agarose beads for 3 h at 4°C in a rotating platform. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer. Bound proteins as well as the starting material (input) were subjected to SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblotting using anti-myc, anti-flag M2 or streptavidin–HRP and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence on X-ray film as described above.

Expression of Smad3 in yeast cells and functional assays

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain pJ694 was a kind gift from D. Tzamarias (IMBB, Heraklion, Crete). Yeast pJ694 cells were transformed with pAS2-1, pAS2-1-Smad3 wt or pAS2-1-Smad3 143–248 plasmids using the lithium acetate/heat-shock protocol. Transformants carrying the desired plasmid were selected for growth on minimal YNB medium consisting of 0.67% yeast nitrogen base (YNB) without amino acids and 2% glucose (YNBD) supplemented with 0.6% casamino acids, adenine and uracil. Their transactivation capacity was tested by their growth ability in the following assays: Ade (−) assay [growth in Ade (−) plates], AT/His (−) assays [growth in His (−) plates supplemented with 5, 10 or 20 mM AT] and X-gal assay [growth in plates supplemented with 0.4% X-gal).

RESULTS

The middle region of Smad3 contains a strong transcriptional activation domain

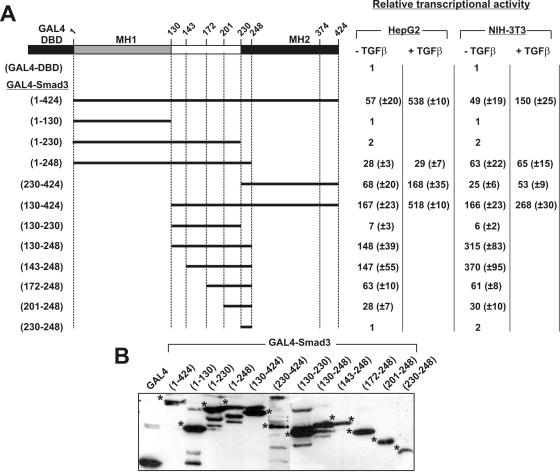

To identify regions in human Smad3 protein that are essential for its transcriptional regulatory properties, several truncated forms of this protein were constructed by PCR amplification and cloned in frame with the DBD of the yeast transactivator GAL4 (amino acids 1–147). These mutants were expressed in two different cell lines, the human hepatoma HepG2 cells and the NIH-3T3 fibroblasts, and assayed for their ability to transactivate an artificial promoter (pG5-E1B-luc) consisting of five tandem GAL4 DNA-binding elements in front of the minimal adenoviral E1B promoter and the luciferase reporter gene.

This analysis showed that the transcriptional activity of wild-type GAL4-Smad3 protein was ∼50-fold higher than the activity of GAL4 DBD alone in both cell lines and was enhanced further by TGFβ stimulation (Figure 1A). TGFβ stimulation was 3.5 times more potent in HepG2 cells than in NIH-3T3 cells, possibly reflecting a difference in the expression levels of TGFβ receptors or other TGFβ signaling regulators between the two cell lines. In contrast, the Smad3 MH1 domain (mutant 1–130) or the MH1 plus the linker domain (mutant 1–230) had no transcriptional activity. Interestingly, the Smad3 mutant 1–248, which includes the MH1, the linker and a small 18 amino acid region of the MH2 domain that includes the first and second β strands of this domain, had high transcriptional activity (28- and 63-fold higher than the GAL4 DBD alone in HepG2 and NIH-3T3 cells, respectively) and this activity was independent of TGFβ stimulation owing to the absence of the receptor interaction and phosphorylation region that resides in the MH2 domain (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Structure–function analysis of the human Smad3 protein. (A) Schematic representation of the wild-type and various truncated Smad3 forms, fused with the DBD of GAL4, that were utilized in transactivation experiments and their relative transcriptional activity in HepG2 and NIH-3T3 cells. HepG2 or NIH-3T3 cells were transfected with the indicated GAL4-Smad3 fusion proteins along with the pG5-E1B-Luc reporter plasmid and the CMV-β galactosidase plasmid. The latter was used for normalization of transfection variability. The normalized transcriptional activity of each GAL4-Smad3 protein in HepG2 and NIH-3T3 cells, relative to the activity of the GAL4 alone, which was set to 1, is presented on the right as a mean value (±SEM) of at least three separate experiments performed in duplicate. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of the different GAL4-Smad3 forms shown in (A) using a monoclonal anti-GAL4 DBD ab. The position of each GAL4-protein is shown with an asterisk.

This analysis also showed that the Smad3 mutant 230–424, which consists of the entire MH2 domain, was as transcriptionally active as wild-type Smad3 and its activity was enhanced further by TGFβ stimulation. Interestingly, the addition of the linker to the MH2 domain (mutant 130–424) increased transactivation 3- and 6-fold in HepG2 and NIH-3T3 cells, respectively (compare the activity of the mutants 130–424 and 230–424), suggesting that the linker domain should contribute to the transactivation function of Smad3 protein. This was verified by a different set of Smad3 mutants, including only the linker region. As shown in Figure 1A, Smad3 mutant 130–230, which consists of the entire linker domain, had very low levels of transcriptional activity compared with the activity of wild-type Smad3 (7- and 6-fold in HepG2 and NIH-3T3, respectively). In contrast, Smad3 mutant 130–248, which consists of the entire linker domain extended to amino acid 248, had very high levels of transcriptional activity in both cell lines (148- and 315-fold, respectively) even in the absence of TGFβ stimulation. This strong transcriptional activity was not affected by a small N-terminal truncation of the linker to amino acid 143 (Smad3 mutant 143–248), but it was decreased and eventually abolished by progressive N-terminal truncations of the linker to amino acids 172, 201 and 230 (Smad3 mutants 172–248, 201–248 and 230–248, respectively). Immunoblotting analysis showed that the expression levels of the GAL4-Smad3 truncated forms used in the transactivation assays of Figure 1A were comparable (Figure 1B).

In conclusion, using the GAL4 transactivation system that allows the identification and characterization of autonomous transactivation domains in transcription factors, we were able to identify a novel, potent and ligand-independent transactivation domain in the middle region of human Smad3 protein bounded by amino acids 143 and 248. The minimal region required for transcriptional activity is between amino acids 200 and 248; thus, we focused our attention to this specific region.

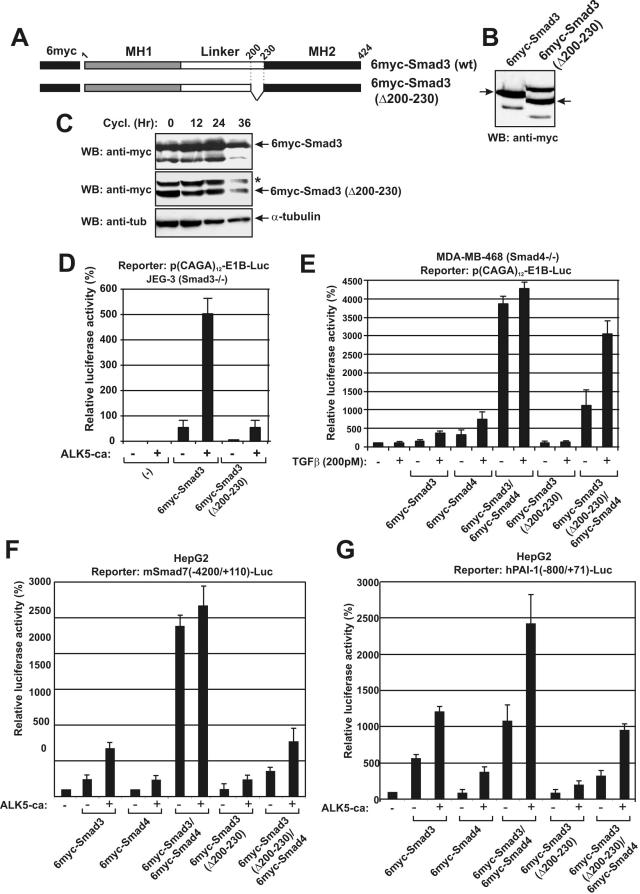

An internal deletion of Smad3 in the middle region severely affected its transcriptional activity

To further investigate the contribution of the middle region of Smad3 in its transactivation properties, we constructed a 6myc-Smad3 mutant bearing a small internal deletion of the 200–230 region (Figure 2A). The levels of expression of this mutant were comparable with the levels of expression of wild-type Smad3 (Figure 2B). Using the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide, it was shown that the 30 amino acid internal deletion of Smad3 did not have any notable effect on the stability of this protein over a period of 24 h as compared with the stability of wild-type Smad3 protein and the endogenous α-tubulin during the same time period (Figure 2C). The transcriptional activity of the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant was evaluated by transactivation experiments in the human JEG-3 choriocarcinoma cell line, which does not express endogenous Smad3 protein (19). As shown in Figure 2D, the activity of the Smad-dependent promoter (CAGA)12E1B consisting of 12 tandem copies of the Smad-binding element and the minimal adenoviral E1B promoter was nearly background in these cells both in the absence and in the presence of the constitutively active ALK5 receptor (ALK5-ca) due to the lack of endogenous Smad3. Overexpression of wild-type Smad3 in these cells reconstituted the TGFβ signaling pathway as evidenced by the enhanced (CAGA)12-E1B promoter activity in the absence and most notably in the presence of ALK5-ca (Figure 2D). In contrast, very weak promoter stimulation was obtained in JEG-3 cells with the expression vector for the Smad3 mutant Δ200–230 and only in the presence of the ALK5-ca receptor (Figure 2D). The difference in transcriptional stimulation between the wild-type and the Δ200–230 mutant in the presence of the ALK5-ca receptor in JEG-3 cells was ∼10-fold.

Figure 2.

Functional properties of a Smad3 mutant lacking part of the middle region. (A) Schematic representation of wild-type Smad3 and the Smad3 Δ200-230 mutant, tagged with a 6myc epitope at their N-terminus. Vertical dashed lines and numbers show the coordinates of the internal deletion. (B) HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors for wild-type Smad3 or the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant, and the expression levels of Smad3 proteins were monitored by immunoblotting using an anti-myc monoclonal antibody. (C) HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors for wild-type Smad3 or the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant. The transfected cells were treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (50 μg/ml) for various time periods, and the expression levels of Smad3 proteins were monitored by immunoblotting using an anti-myc monoclonal antibody. Relative total protein levels were estimated by monitoring the expression of endogenous α-tubulin. The position of the 6myc-Smad3 proteins and α-tubulin is shown with arrows. The asterisk shows a 6myc-tagged Smad3 (Δ200–230) mutant with a lower electrophoretic mobility that is possibly derived from the utilization of an alternative translation termination signal. (D) JEG-3 (Smad3 −/−) choriocarcinoma cells were transfected with expression vectors for 6xmyc-Smad3 or 6xmyc-Smad3 (Δ200–230) along with the p(CAGA)12-E1B-Luc reporter, in the absence or in the presence of an expression vector for ALK5-ca. The normalized mean values of luciferase activity (±SEM) are shown with a bar graph. (E) Breast cancer MDA-MB-468 (Smad4 −/−) cells were transfected with expression vectors for 6xmyc-Smad3 or 6xmyc-Smad3 (Δ200–230) along with the p(CAGA)12-E1B-Luc reporter in the absence or in the presence of an expression vector for 6myc-Smad4 and TGFβ (200 pM). The normalized mean values of luciferase activity (±SEM) are shown with a bar graph. (F and G) Human hepatoma HepG2 cells were transfected with expression vectors for 6xmyc-Smad3 or 6xmyc-Smad3 (Δ200–230) in the absence or in the presence of an expression vector for 6myc-Smad4 and ALK5-ca and luciferase reporter plasmids bearing the promoters of the mouse Smad7 gene (−4200/+110) (F) or the human PAI-1 gene (−800/+71) (G) as indicated. The normalized mean values of luciferase activity (±SEM) are shown with bar graphs.

To investigate the ability of the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant to transcriptionally cooperate with Smad4, its activity was analyzed in the breast cancer-derived cell line MDA-MB-468, which lacks endogenous Smad4 expression (20). As shown in Figure 2E, a strong synergistic transactivation of the (CAGA)12-E1B promoter was observed by the simultaneous expression of wild-type Smad3 and Smad4 proteins, whereas the addition of TGFβ did not change the activity of the (CAGA)12-E1B promoter in a statistically significant manner possibly due to the overexpression of the wild-type Smad proteins in the transfected MDA-MB-468 cells. Synergistic transactivation of the (CAGA)12-E1B promoter by the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant and Smad4 was also observed both in the absence and in the presence of added TGFβ, albeit to lower levels than the corresponding activity of wild-type Smad3 under the same conditions. The transcriptional activity of the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant was also evaluated on two natural promoters shown previously to be regulated by the TGFβ signaling pathway, i.e. the promoter of the mouse Smad7 gene and of the human plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) gene (21,22). The activity of Smad7 and PAI-1 promoters was significantly lower in the presence of the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant than in the presence of wild-type Smad3 either in the presence or in the absence of the ALK5-ca receptor and Smad4 (Figure 2F and G, respectively).

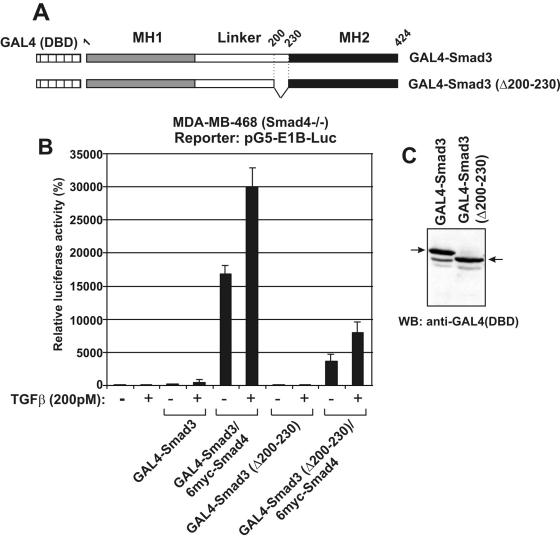

Similar results were obtained using the GAL4 system. For the purpose of this experiment, the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant was fused with the DBD of GAL4 (Figure 3A) and used in transactivation experiments in Smad4 (−/−) MDA-MB-468 cells. As shown in Figure 3B, GAL4-Smad3 wild-type protein strongly enhanced the activity of the G5-E1B promoter in MDA-MB-468 cells only in the presence of coexpressed Smad4 and this Smad3/Smad4 synergism was further potentiated by the addition of TGFβ. The GAL4-Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant was still capable of activating transcription in the presence of exogenous Smad4 and TGFβ, albeit to three times lower levels than wild-type Smad3 (Figure 3B). Immunoblotting analysis showed comparable levels of expression of the wild-type GAL4-Smad3 and the GAL4-Smad3 Δ200–230 fusion proteins (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Deletion of the middle region of Smad3 reduces transactivation in GAL4 assays: (A) Schematic representation of wild-type Smad3 and the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant, fused with the DBD of the yeast transactivator GAL4 at their N-terminus. Vertical dashed lines and numbers show the coordinates of the internal deletion. (B) MDA-MB-468 cells were transfected with GAL4-Smad3 (wt) or GAL4-Smad3 (Δ200–230) vectors and the pG5-E1B-Luc reporter plasmid in the absence or in the presence of an expression vector for 6myc-Smad4 in the presence or in the absence of 200 pM of TGFβ as indicated at the bottom of the graph. The relative, normalized, luciferase activity (±SEM) is presented in the form of a bar graph. (C) Immunoblotting analysis of transfected wild-type and Δ200–230 GAL4-Smad3 proteins using an anti-GAL4 (DBD) antibody. The arrows show the position of the GAL4-Smad3 proteins.

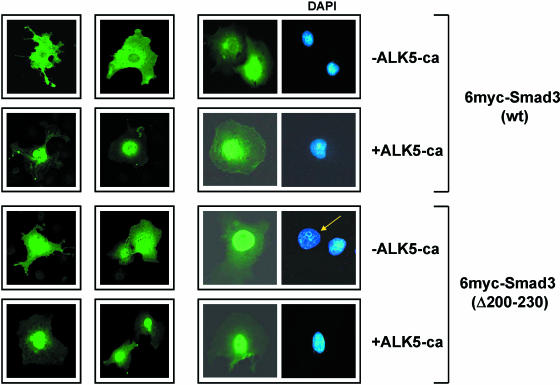

Deletion of the middle region does not affect Smad3 nuclear import

The intracellular localization of wild-type Smad3 and the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant lacking the middle region was analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence. As shown in Figure 4, wild-type Smad3 displayed a predominant cytoplasmic localization in the absence of the ALK5-ca receptor, whereas in the presence of ALK5-ca, Smad3 showed prominent nuclear accumulation. Similarly, the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant displayed a cytoplasmic or perinuclear staining in the absence of ALK5-ca, which became predominantly nuclear in the presence of ALK5-ca. The data of Figure 4 suggest that the decreased transactivation efficiency of the Smad3 mutant lacking the 200–230 middle region may not be due to a defect in the TGFβ-stimulated nuclear import of this protein.

Figure 4.

Deletion of the middle region does not affect Smad3 nuclear accumulation: COS-7 cells were transfected with expression vectors for the wild-type 6myc-Smad3 protein or the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant in the absence or in the presence of the constitutively active ALK5 receptor as indicated on the right. Immunofluorescence was performed using the anti-myc (9E10) monoclonal antibody followed by a secondary, FITC-conjugated, antibody. Smad proteins were visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Representative DAPI staining of the transfected cells is also shown.

Deletion of the middle region does not affect Smad3 homo- or heteromerization

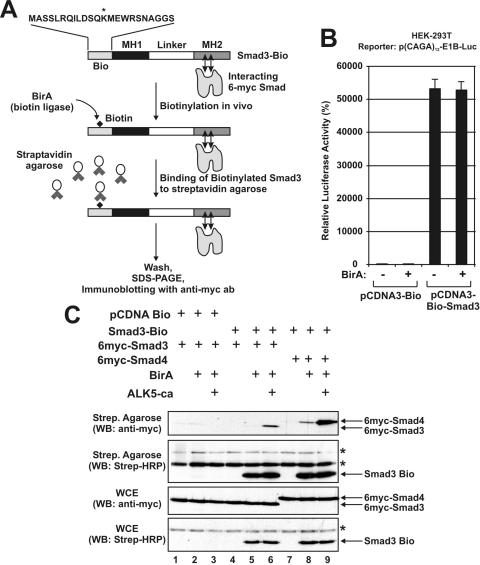

To investigate the role of the linker region in Smad3 homo- and heteromerization, we employed a recently described protein–protein interaction assay based on protein biotinylation in vivo (18). The basic principle of our strategy is shown schematically in Figure 5A. First, we constructed a Smad3 protein bearing a 23 amino acid N-terminal peptide tag that is a target for the bacterial biotin ligase BirA (Bio tag, Figure 5A). This Smad3-Bio fusion protein can be biotinylated in mammalian cells by cotransfection with BirA. Biotinylated Smad3 proteins, along with any proteins that interact with it in vivo such as 6myc-Smad proteins, are subsequently bound to streptavidin agarose beads. Smad3 interacting proteins can be analyzed by SDS–PAGE and western blotting using the appropriate antibodies.

Figure 5.

Utilization of an in vivo biotinylation assay to probe the oligomerization properties of Smad3. (A) Basic principle of the protein–protein interaction assay based on Smad3 biotinylation in vivo. (B) HEK-293T cells were transfected with pCDNA3-Bio-Smad3 (wt), and the p(CAGA)12-E1B-Luc reporter plasmid in the absence or presence of an expression vector for biotin ligase BirA as indicated at the bottom of the graph. The relative, normalized, luciferase activity (±SEM) is presented in the form of a bar graph. (C) HEK-293T cells were transfected with different combinations of expression vectors for Bio, Smad3-Bio, 6myc-Smad3, 6myc-Smad4, BirA and ALK5-ca as indicated on top. The concentrations of plasmids used and the protocol of the protein–protein interaction assay are described in detail in Materials and Methods. Western blottings were performed using the anti-myc (9E10) monoclonal antibody for the detection of myc-tagged Smad3 and Smad4 proteins (first and third row) or HRP-conjugated streptavidin for the detection of biotinylated Smad3 protein (second and fourth row). The arrows on the right show the position of the indicated proteins. Asterisks show non-specific biotinylated proteins that are detected by streptavidin HRP.

First, we excluded the possibility that the addition of a biotin molecule at the N-terminus of Smad3 causes any major dysfunction by showing that the biotinylated Smad3 protein fully retained its capacity to transactivate the (CAGA)12-E1B promoter in HEK-293T cells (Figure 5B).

Using the biotinylation system just described, we were able to reproduce a ligand-dependent interaction of Smad3 with itself (homomerization) or with Smad4 (heteromerization) in vivo. As shown in Figure 5C, interaction of biotinylated Smad3 with 6myc-tagged Smad3 in vivo was detected only in the presence of the biotin ligase BirA and the constitutively active ALK5-ca receptor (Figure 5C, upper panel, lane 6). The same was true for the interaction between biotinylated Smad3 and 6myc-tagged Smad4. In this case, a weak interaction between biotinylated Smad3 and Smad4 was observed in the absence of the ALK5-ca receptor, but the coexpression of the receptor significantly enhanced the interaction between the two proteins (Figure 5C, upper panel, compare lanes 8 and 9). The biotinylation of Bio-Smad3 protein in whole cell extracts and on the streptavidin agarose beads and the expression of 6myc-tagged Smad3 and Smad4 were verified by western blotting experiments using streptavidin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or a monoclonal anti-myc antibody (Figure 5C as indicated on the left of each panel).

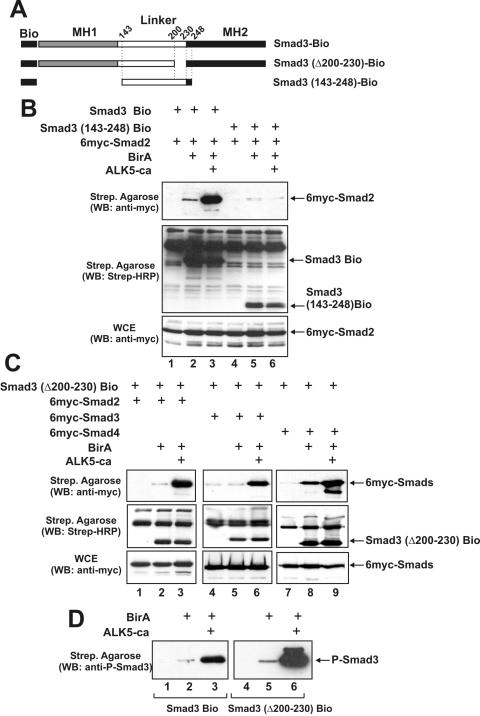

Physical interactions between biotinylated Smad3 and 6myc-Smad2 were also demonstrated with the biotinylation assay. Similar to Smad4, Smad2 interacted weakly with biotinylated Smad3 in the absence of the ALK5-ca receptor but this interaction was enhanced in the presence of the receptor (Figure 6B, upper panel, compare lanes 2 and 3). In a control experiment, we showed that the biotinylated Smad3 143–248 mutant that lacks the MH2 domain (Figure 6A) could not interact with Smad2 either in the absence or in the presence of ALK5-ca receptor (Figure 6B, upper panel, lanes 5 and 6) or with Smad3 and Smad4 (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Deletion of the middle region does not affect Smad homo- and hetero-oligomerization or phosphorylation by the ALK5 receptor. (A) Schematic representation of wild-type Smad3-Bio, Smad3 (Δ200–230)-Bio and the Smad3 (143–248)-Bio proteins used in the oligomerization experiments of (B and C). (B) HEK-293T cells were transfected with various combinations of expression vectors for Smad3-Bio, Smad3 (143–248)-Bio, 6myc-Smad2, BirA and ALK5-ca as indicated on top. Western blottings were performed using the anti-myc monoclonal antibody for the detection of myc-tagged Smad2 (first and third row) or HRP-conjugated streptavidin for the detection of biotinylated Smad3 proteins (second row). (C) HEK-293T cells were transfected with various combinations of expression vectors for Smad3 (Δ200–230)-Bio, 6myc-Smad2, 6myc-Smad3, 6myc-Smad4, BirA and ALK5-ca as indicated on top. Western blottings were performed using the anti-myc monoclonal antibody for the detection of myc-tagged Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 (first and third row) or HRP-conjugated streptavidin for the detection of biotinylated Smad3 proteins (second row). (D) HEK-293T cells were transfected with expression vectors for Smad3-Bio or Smad3 (Δ200–230)-Bio in the absence or in the presence of BirA and ALK5-ca as indicated on top. Proteins bound to the streptavidin agarose beads were analyzed by immunoblotting using a polyclonal antibody recognizing only the phosphorylated form of Smad3.

Having established the validity of the biotinylation assay for the analysis of protein–protein interactions in the TGFβ pathway in vivo, we proceeded to analyze the homo- and heteromerization properties of the Smad3 mutant bearing the internal deletion Δ200–230. For this purpose, a new plasmid was constructed expressing the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant as fusion with the Bio peptide (Figure 6A). As shown in Figure 6C, efficient, receptor-dependent interactions between the biotinylated Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant and Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 was observed (upper panel, lanes 3, 6 and 9, respectively), suggesting that the deletion of the middle region of Smad3 between amino acids 200 and 230 has no effect on Smad homo- or heteromerization. Furthermore, the receptor-dependency of the interactions shown in Figure 6C suggested that the internal deletion should not affect the interaction of Smad3 with the type I TGFβ receptor. We confirmed this by showing that both wild-type Smad3 and the Δ200–230 mutant are efficiently phosphorylated by the ALK5-ca receptor (Figure 6D, lanes 3 and 6).

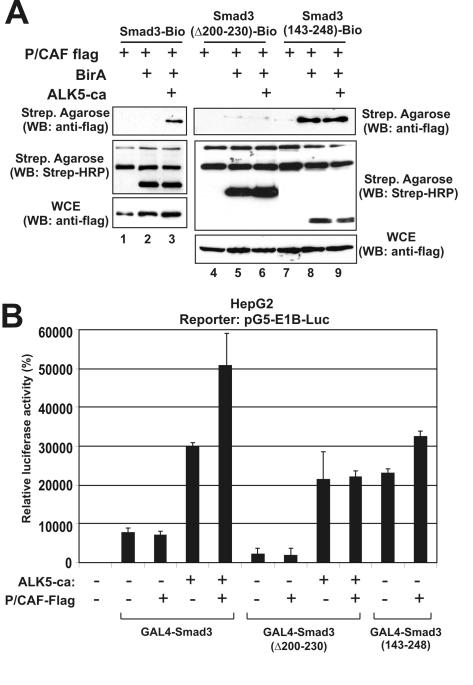

Deletion of the 200–230 region affects the physical and functional interactions between Smad3 and the histone acetyltransferase p/CAF

To further investigate the mechanism of the transcriptional inactivation of the Smad3 mutant bearing the internal deletion Δ200–230, we analyzed the ability of this mutant to interact physically and functionally with the histone acetyltransferase p/CAF. Interactions of Smad3 with this coactivator as well its homolog GCN5 have been demonstrated previously (23,24). As shown in Figure 7A, the biotinylated wild-type Smad3 protein interacted with flag-tagged p/CAF in an ALK5-dependent manner (upper panel, lane 3). In contrast, the biotinylated Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant failed to interact with p/CAF either in the absence or in the presence of ALK5-ca (Figure 7A, upper panel, lanes 5 and 6).

Figure 7.

Deletion of the middle region abolishes physical and functional interactions of Smad3 with histone acetyltransferase p/CAF. (A) HEK-293T cells were transfected with various combinations of expression vectors for Bio-Smad3, Bio-Smad3 Δ200–230, Bio-Smad3 143–248, p/CAF-flag, BirA and ALK5-ca as indicated on top. The concentrations of plasmids used and the protocol of the protein–protein interaction assay are described in detail in Materials and Methods. Western blottings were performed using the anti-flag monoclonal antibody for the detection of p/CAF (first and third row) or HRP-conjugated streptavidin for the detection of biotinylated Smad proteins (second row). WCE, whole cell extract; Strep, streptavidin. (B) HepG2 cells were transfected with GAL4-Smad3, GAL4-Smad3 (Δ200–230) or GAL4-Smad3 (143–248) and the pG5-E1B-Luc reporter plasmid in the absence or in the presence of an expression vector for ALK5-ca and p/CAF-FLAG as indicated at the bottom of the graph. The relative, normalized, luciferase activity (±SEM) is presented in the form of a bar graph.

To confirm the participation of the middle region of Smad3 in protein–protein interactions with p/CAF, we utilized the Smad3 143–248 mutant that was shown in Figure 1A to have high levels of TGFβ-independent transcriptional activity. This analysis showed that the 143–248 mutant interacts potently with p/CAF even in the absence of stimulation by the ALK5-ca receptor (Figure 7A, upper panel, lanes 8 and 9).

We also performed GAL4 transactivation assays using the wild-type Smad3 and the Smad3 mutants Δ200–230 and 143–248 in the absence and in the presence of p/CAF. As shown in Figure 7B, p/CAF enhanced the transcriptional activity of the wild-type GAL4-Smad3 protein only in the presence of ALK5-ca. In contrast, p/CAF had no effect on the activity of the GAL4-Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant, either in the presence or in the absence of ALK5-ca, which showed that the interaction between Smad3 and p/CAF requires both the 200–230 region and the stimulation by the ALK5-ca receptor. Finally, p/CAF enhanced the activity of the Smad3 143–248 mutant again in agreement with the physical interaction data of Figure 7A.

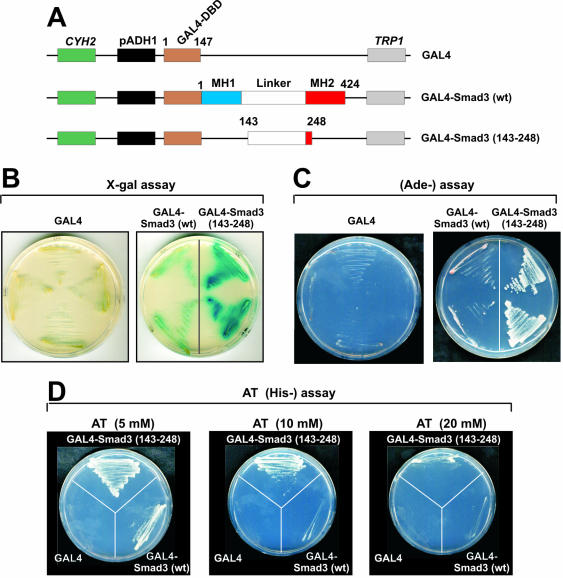

The middle region of human Smad3 protein is transcriptionally functional in yeast cells that lack an endogenous TGFβ/Smad pathway

To further explore our findings regarding the ligand-independent transcriptional activation function of the middle region of Smad3, we performed transactivation experiments in yeast cells that are devoid of an endogenous TGFβ/Smad pathway. For this purpose, wild-type Smad3 and the Smad3 143–248 mutant bearing only the middle region were cloned into a yeast expression vector as fusions with the DBD of GAL4 (Figure 8A) and utilized in transactivation experiments in S.cerevisiae. The results presented in Figure 8B–D established that wild-type GAL4-Smad3 and the GAL4-Smad3 143–248 mutant transactivated a GAL4-dependent promoter linked to various reporter genes, including the β-galactosidase gene (Figure 8B), the ADE1 gene (Figure 8C) and the HIS3 gene (Figure 8D). Importantly, the GAL4-Smad3 143–248 mutant displayed higher transcriptional activity than wild-type Smad3 in yeast in accordance with the transactivation data from HepG2 and NIH-3T3 cells (Figure 1A). Thus, the transactivation experiments in yeast cells confirmed that the middle region of Smad3 possesses a strong, ligand-independent, transcriptional activation function.

Figure 8.

Wild-type Smad3 and the Smad3 (143–248) mutant are functional in yeast cells. (A) Schematic representation of the yeast expression vectors that were utilized in the assays of B–D. (B–D) Functional assays which established that GAL4-Smad3 (wt) or GAL4-Smad3 (143–248) mutant are functional in yeast cells. The assays were based on the ability of transformed GAL4-Smad4 (wt) or GAL4-Smad3 (143–248) to activate chromatin incorporated reporters consisting of 5 GAL4 binding sites linked to the β-galactosidase gene (B), the ADE1 gene (C) and the HIS3 gene (D). These assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have investigated the role of the middle linker region of Smad3, a key intracellular mediator of the TGFβ signaling pathway, in various functions characteristic of the R-smad (receptor-regulated Smad) family, including ligand-stimulated phosphorylation, oligomerization, nuclear accumulation and transcriptional activation of TGFβ target promoters. Our study was facilitated by the generation of large number of N-terminal, C-terminal and internal truncations of the protein and their utilization in functional assays, including the well-established GAL4-based transactivation assay as well as a recently described protein–protein interaction assay (18).

The selection of the GAL4-based assay for our analyses was based on the following criteria: (i) it allows the identification of autonomous transactivation domains in truncated forms of multifunctional proteins by their recruitment to a target promoter via an heterologous DBD that does not recognize endogenous regulatory elements in mammalian cells; and (ii) it allows efficient nuclear localization of the tested protein domains owing to the presence of a nuclear localization signal inside the DBD of the GAL4 protein. Using this approach, we were able to show that the middle, non-conserved, linker domain of Smad3, bounded by amino acids 143 and 248, harbors a strong, TGFβ-independent transcriptional activation domain that cooperates with the MH2 domain to achieve maximal levels of transcriptional activity (Figure 1). The importance of the middle region of Smad3 for transcriptional activation was also established by showing that a Smad3 mutant bearing an internal deletion of the 200–230 middle region drastically reduced the transactivation capacity of Smad3. The 200–230 region was selected for further analysis because it was the minimal region of the linker domain with an autonomous transcriptional activation function in our GAL4 assays (Figure 1A). This deletion did not have any effect on the stability of Smad3 as shown by the cycloheximide experiment of Figure 2A.

Using the in vivo biotinylation system, we were able to reconstitute ligand-dependent homomeric and heteromeric interactions between Smad proteins and to analyze the effect of mutations in these interactions. This system is much more sensitive than the widely used co-immunoprecipitation assay or the glutathione S-transferase pull-down assay owing to the extremely high affinity and specificity of the biotin–streptavidin interaction. Using a panel of control antibodies, we could not observe any non-specific interactions with this assay. Furthermore, the binding of endogenous biotinylated proteins to the streptavidin agarose beads, which are clearly visible in our western blotting assays of Figures 5–7, does not seem to interfere with the purification of Smad3-interacting proteins.

Using this technology, we showed that the transcriptional defect of the Smad3 Δ200–230 mutant could not be attributed to impaired ligand-dependent phosphorylation by the TGFβ type I receptor (ALK5-ca) or to impaired ligand-dependent homo- and heteromerization with Smad2 and Smad4 (Figure 6). Furthermore, we established that deletion of the linker region does not prevent the accumulation of Smad3 in the nucleus in a ligand-dependent manner (Figure 4).

The transcriptional activity of the middle region of Smad3 could be attributed, at least in part, to its interaction with nuclear coactivators, such as the histone acetyltransferases CBP/p300 and p/CAF. We speculated that this region may play a role analogous to the Smad activation domain (SAD), a 48 amino acid, proline-rich element within the linker domain of Smad4 protein, which was shown previously to be sufficient to activate transcription in GAL4 assays (25). The transcriptional activity of SAD could be attributed, at least in part, to its physical and functional interactions with the p300 coactivator (25). In preliminary analyses, we found that the 200–248 region of Smad3 has the potential to interact physically and functionally with the middle region of the p300 homologous protein, CREB binding protein (CBP) and not with the N-terminal region, which is required for its interaction with the SAD domain of Smad4 (V. Prokova and D. Kardassis, unpublished data). Our data are in agreement with a recent study showing that the linker region of Smad3 (amino acids 143–230) physically and functionally interacts with the p300 coactivator (26). Amino acid sequence comparison between Smad3 and other R-Smads or Smad4 in the 200–230 region revealed the conservation of several proline resides (prolines 205, 209, 214, 223 and 229) as well as of additional amino acids (leucine 219, glutamine 222 and alanine 230) in this region that could be important for its function as a transactivation domain, but this hypothesis requires further mutagenesis analysis of these proteins in the above region.

We also found that the middle region of Smad3 has the ability to interact with the histone acetyltransferase p/CAF, whereas an internal deletion mutant of Smad3 in this region abolished its affinity for p/CAF (Figure 7A). These results seem to contradict previous observations which had shown that a Smad3 mutant lacking the MH2 domain (Smad3 ΔMH2) is unable to interact with p/CAF (23). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the physical interactions between our in vivo biotinylated Smad3 linker domain and p/CAF could be indirect, requiring auxiliary nuclear factors that bind to the linker region of Smad3.

Although the contribution of the Smad3–p/CAF interaction for Smad-mediated transcriptional responses in vivo remains to be established by gene knock-out experiments, it was shown recently that siRNA-mediated inactivation of the p/CAF homologous protein gcn5 in mammalian cells affected Smad3-mediated transactivation (24). This finding prompted us to speculate that a similar interaction with the yeast gcn5 (27) could easily account for the high levels of transcriptional activity of the wild-type Smad3 or the Smad3 143–248 mutant in S.cerevisiae (Figure 8). Given that a number of yeast transcriptional regulatory proteins, including coactivators, histone acetyltransferases, such as gcn5, mediator components or chromatin remodeling enzymes, have their homologs in mammalian cells (28–30), we predict that the yeast system could serve as a valuable tool for the initial identification of factors that participate in evolutionarily conserved Smad-mediated mechanisms of transcriptional activation.

The middle linker domain of Smad3 contains several serine residues, some of which have been shown to serve as sites for phosphorylation by kinases, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinases Erk, p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase, cyclin-dependent kinases and Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent kinase II (31–35). Phosphorylation of the linker region by the above kinases may regulate several Smad3 functions, including nuclear accumulation in response to TGFβ stimulation. For instance, it was shown that oncogenic ras, acting via the Erk MAP kinase, causes phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 at specific Ser-Pro motifs in the middle linker region causing cytoplasmic retention, whereas mutagenesis of these MAP kinase sites in Smad3 yielded a ras-resistant form that could rescue the growth inhibitory response to TGFβ in Ras-transformed cells (31). Given that the same region in Smad3 that contains the above Ser-Pro motifs (region 200–230) is also required for the transcriptional activity of Smad3 and its interaction with coactivators (as shown in the present study), we are tempted to speculate that the phosphorylation of these Smad3 motifs by MAP kinases may regulate, in addition to the intracellular distribution, the transactivation function of Smad3 by influencing its interactions with coactivators or auxiliary factors that bind to this region.

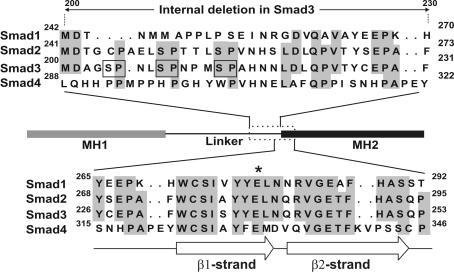

Finally, our structure–function analysis of Figure 1A showed that a small region at the N-terminal part of the MH2 domain is essential for the transactivation function of linker domain as well as of the MH2 domain (V. Prokova and D. Kardassis, unpublished data). This region is highly conserved among the Smad family members, and according to the crystal structure of Smad4, it includes the first two β strands (β1 and β2) of this domain (Figure 9) (12). This region, being an integral part of the loop–helix region of the MH2 domain, may be important for Smad oligomerization. However, this region by itself is not sufficient to confer oligomerization properties to the linker domain as shown in the present study (Figure 6B). Importantly, a single amino acid substitution within the β1-strand of Smad4 (E330A) was found to be frequently associated with tumors (15). This specific amino acid residue is also conserved in the R-Smads, including Smad1, Smad2 and Smad3 (Figure 9). It is not yet known whether this specific mutation in Smad4 is responsible for loss of TGFβ signaling in these tumor cells. Our preliminary observations showed that the corresponding mutation in Smad3 severely inhibits its transcriptional activity in mammalian cells as well its oligomerization properties (V. Prokova, S. Mavridou and D. Kardassis, unpublished data) further supporting the important role of this region for TGFβ signaling.

Figure 9.

Homology between Smad3 and other members of the Smad family in the transcriptionally active 200–253 region. The amino acid identity among Smad family members is shown by gray shadowing. The single letter code for the representation of the amino acid sequences was utilized. The thin black arrow indicates the internal deletion that was introduced into full-length Smad3 protein. The wide white arrows represent β strands. A missense mutation in a conserved amino acid present in the β1-strand of Smad4 (E330), which is associated with tumors, is shown with an asterisk. Ser-Pro motifs that are potential targets for phosphorylation by MAP kinases in Smad3 are shown by open squares.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of Tzamarias laboratory Niki Gounalaki and Manolis Papamichos-Chronakis (IMBB-FORTH) for assistance in the yeast experiments. The authors also thank Dr John Strouboulis (Erasmus U, Rotterdam), Dr Aris Moustakas, (LICR, Uppsala), Peter ten Dijke (NCI, Amsterdam), Dr Iannis Talianidis (IMBB-FORTH, Heraklion) and Dr Vassilis Zannis (UC and IMBB-FORTH, Heraklion) for cell lines and reagents used in this study, Dr Aris Moustakas for his suggestions on the manuscript and all the members of the Kardassis laboratory for helpful discussions and technical help. This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Development of Greece (PENED-2001) and by funds from the Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology of Crete. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by a grant from the Ministry of Development of Greece.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Massagué J. TGF-β signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:753–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts A.B., Sporn M.B. The transforming growth factor-betas. In: Sporn M.B., Roberts A.B., editors. Peptide Growth Factors and Their Receptors. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derynck R., Zhang Y.E. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-β family signaling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi Y., Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moustakas A., Souchelnytskyi S., Heldin C. Smad regulation in TGF-β signal transduction. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:4359–4369. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ten Dijke P., Miyazono K., Heldin C.-H. Signaling inputs converge on nuclear effectors in TGF-β signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:64–70. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01519-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massagué J., Wotton D. Transcriptional control by the TGF-β/Smad signaling system. EMBO J. 2000;19:1745–1754. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Y., Wang Y.-F., Jayaraman L., Yang H., Massagué J., Pavletich N.-P. Crystal structure of a Smad MH1 domain bound to DNA: insights on DNA binding in TGF-β signaling. Cell. 1998;94:585–594. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurisaki A., Kose S., Yoneda Y., Heldin C.-H., Moustakas A. Transforming growth factor-beta induces nuclear import of Smad3 in an importin- β1 and Ran-dependent manner. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:1079–1091. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.4.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao Z., Liu X., Henis Y.-I., Lodish H.-F. A distinct nuclear localization signal in the N terminus of Smad 3 determines its ligand-induced nuclear translocation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7853–7858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu F., Hata A., Baker J.-C., Doody J., Carcamo J., Harland R.-M., Massagué J. A human Mad protein acting as a BMP-regulated transcriptional activator. Nature. 1996;381:620–623. doi: 10.1038/381620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y., Hata A., Lo R.-S., Massagué J., Pavletich N.-P. A structural basis for mutational inactivation of the tumour suppressor Smad4. Nature. 1997;388:87–93. doi: 10.1038/40431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qin B.Y., Lam S.S., Correia J.J., Lin K. Smad3 allostery links TGF-β receptor kinase activation to transcriptional control. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1950–1963. doi: 10.1101/gad.1002002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu J.W., Hu M., Chai J., Seoane J., Huse M., Li C., Rigotti D.J., Kyin S., Muir T.W., Fairman R., Massague J., Shi Y. Crystal structure of a phosphorylated Smad2. Recognition of phosphoserine by the MH2 domain and insights on Smad function in TGF-β signaling. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:1277–1289. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00421-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hata A., Shi Y., Massagué J. TGF-β signaling and cancer: structural and functional consequences of mutations in Smads. Mol. Med. Today. 1998;4:257–262. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(98)01247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kardassis D., Pardali K., Zannis V.-I. SMAD proteins transactivate the human ApoCIII promoter by interacting physically and functionally with hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:41405–41414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007896200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho S.-N., Hunt H.-D., Horton R.-M., Pullen J.-K., Pease L.-R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Boer E., Rodriguez P., Bonte E., Krijgsveld J., Katsantoni E., Heck A., Grosveld F., Strouboulis J. Efficient biotinylation and single-step purification of tagged transcription factors in mammalian cells and transgenic mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7480–7485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332608100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu G., Chakraborty C., Lala P.K. Expression of TGF-β signaling genes in the normal, premalignant, and malignant human trophoblast: loss of smad3 in choriocarcinoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;287:47–55. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Winter J.P., Roelen B.A., ten Dijke P., van der Burg B., van den Eijnden-van Raaij A.J. DPC4 (SMAD4) mediates transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-β1) induced growth inhibition and transcriptional response in breast tumour cells. Oncogene. 1997;14:1891–1899. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brodin G., Ahgren A., ten Dijke P., Heldin C.H., Heuchel R. Efficient TGF-beta induction of the Smad7 gene requires cooperation between AP-1, Sp1, and Smad proteins on the mouse Smad7 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:29023–29030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keeton M.R., Curriden S.A., van Zonneveld A.J., Loskutoff D.J. Identification of regulatory sequences in the type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor gene responsive to transforming growth factor beta. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:23048–23052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itoh S., Ericsson J., Nishikawa J., Heldin C.-H., ten Dijke P. The transcriptional co-activator P/CAF potentiates TGF-β/Smad signaling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4291–4298. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.21.4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahata K., Hayashi M., Asaka M., Hellman U., Kitagawa H., Yanagisawa J., Kato S., Imamura T., Miyazono K. Regulation of transforming growth factor-beta and bone morphogenetic protein signalling by transcriptional coactivator GCN5. Genes Cells. 2004;9:143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Caestecker M.-P., Yahata T., Wang D., Parks W.-T., Huang S., Hill C.-S., Shioda T., Roberts A.-B., Lechleider R.-J. The Smad4 activation domain (SAD) is a proline-rich, p300-dependent transcriptional activation domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:2115–2122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang G., Long J., Matsuura I., He D., Liu F. The Smad3 linker region contains a transcriptional activation domain. Biochem. J. 2005;386:29–34. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sternglanz R., Schindelin H. Structure and mechanism of action of the histone acetyltransferase Gcn5 and similarity to other N-acetyltransferases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:8807–8808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berk A.J. Activation of RNA polymerase II transcription. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 1999;11:330–335. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurdistani S.K., Grunstein M. Histone acetylation and deacetylation in yeast. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;4:276–284. doi: 10.1038/nrm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rachez C., Freedman L.P. Mediator complexes and transcription. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 2001;13:274–280. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kretzschmar M., Doody J., Timokhina I., Massague J. A mechanism of repression of TGF-beta/Smad signaling by oncogenic ras. Genes Dev. 1999;13:804–816. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engel M.E., McDonnell M.A., Law B.K., Moses H.L. Interdependent SMAD and JNK signaling in transforming growth factor-beta-mediated transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:37413–37420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mori S., Matsuzaki K., Yoshida K., Furukawa F., Tahashi Y., Yamagata H., Sekimoto G., Seki T., Matsui H., Nishizawa M., Fujisawa J., Okazaki K. TGF-beta and HGF transmit the signals through JNK-dependent Smad2/3 phosphorylation at the linker regions. Oncogene. 2004;23:7416–7429. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuura I., Denissova N.G., Wang G., He D., Long J., Liu F. Cyclindependent kinases regulate the antiproliferative function of Smads. Nature. 2004;430:226–231. doi: 10.1038/nature02650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wicks S.J., Lui S., Abdel-Wahab N., Mason R.M., Chantry A. Inactivation of Smad-transforming growth factor beta signaling by Ca(2+)-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:8103–8111. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.8103-8111.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]