Abstract

Introduction

We present a rare case of long‐term survival following metastasectomy for lumbar metastasis with growing teratoma syndrome.

Case presentation

An 18‐year‐old man presented with left scrotal mass and lumbago. Alpha‐fetoprotein was elevated to 648.8 ng/mL, while human chorionic gonadotropin and lactate hydrogenase were normal. Pathology of left inguinal orchiectomy revealed immature teratoma, and computed tomography confirmed a single metastasis in the second lumbar vertebra. After two courses of bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin chemotherapy, alpha‐fetoprotein decreased, but computed tomography confirmed an enlarged lumbar metastasis. A vertebral biopsy demonstrated teratoma with a dominant mature component, and growing teratoma syndrome was suspected. Following additional etoposide, cisplatin chemotherapy, and normalization of alfa‐fetoprotein, total spondylectomy was performed. Vertebral pathology proved mature teratoma. After adjuvant chemotherapy, he has been recurrence‐free for 17 years.

Conclusion

Spondylectomy of a single metastatic vertebra contributed to long‐term survival in a testicular teratoma case.

Keywords: growing teratoma syndrome, metastasectomy, pure teratoma, spinal metastasis, spondylectomy, testicular neoplasms

Keynote message.

Early surgery was necessary to address the spinal symptoms resulting from growing teratoma syndrome in the vertebral metastases. The isolated nature of the metastasis enabled complete removal, significantly contributing to the patient's long‐term survival.

Abbreviations & Acronyms

- AFP

alpha‐fetoprotein

- BEP

bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin

- CR

complete remission

- CT

computed tomography

- EP

etoposide, cisplatin

- GCNIS

germ cell neoplasia in situ

- GTS

growing teratoma syndrome

- hCG

human chorionic gonadotropin

- IGCCCG

International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group

- L2

the 2nd lumbar

- LDH

lactate hydrogenase

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NSGCT

non‐seminomatous germ cell tumors

- TIP

paclitaxel, ifosfamide, cisplatin

- WHO

World Health Organization

Introduction

This is a case of testicular teratoma with solitary L2 metastasis, where spondylectomy enabled long‐term survival despite GTS.

Case presentation

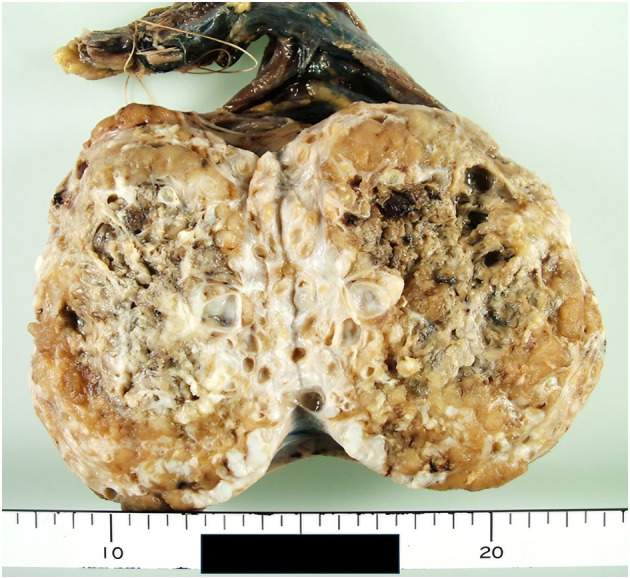

An 18‐year‐old man was referred with a left testicular tumor and recent lumbago. Physical examination showed a firm left testicular mass, with no spread to the spermatic cord. AFP was elevated to 648.8 ng/mL, with normal HCG‐β and LDH. CT showed no lymph node swelling or lung metastasis but confirmed L2 vertebral bone metastasis. Left inguinal orchiectomy revealed an 11 × 8 cm mass with a grossly divided surface of white to grayish‐white color, hemorrhage, and mesh‐like microcysts (Fig. 1). The tumor consisted mainly of atypical mesenchymal and immature to blastic cells, with epithelial‐like and neural tube‐like structures, and partial necrosis. Histology showed pT1 immature pure teratoma with rete testis invasion, no other germ cell component, and a negative spermatic cord margin. The clinical stage was IIIC, classified as poor risk by the IGCCCG.

Fig. 1.

A photograph after formalin fixation shows a large testicular tumor, measuring 11 × 8 cm, with a white to grayish‐white cracked surface, some hemorrhage, and microcysts.

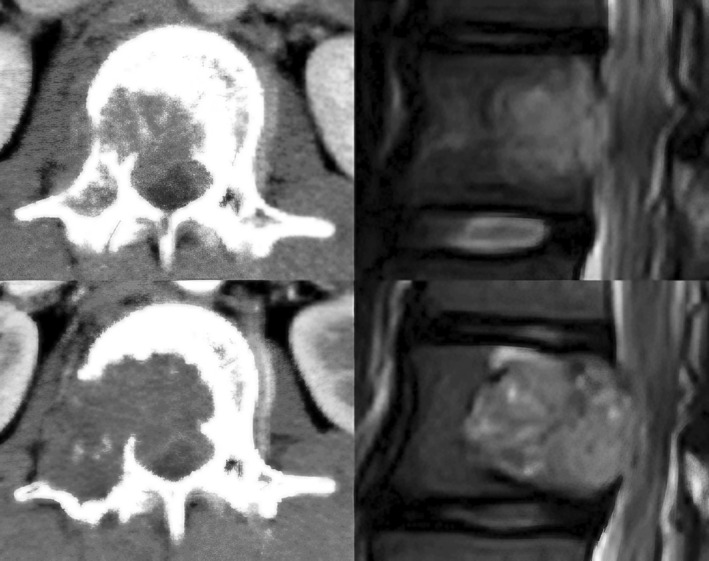

He received BEP chemotherapy, preserving semen for future fertility. Two cycles nearly normalized AFP; however, a subsequent CT revealed increased L2 bone metastasis. Additional MRI for worsening back pain confirmed prominent spinal cord compression (Fig. 2), and L2 biopsy revealed a teratoma with immature elements that had decreased in proportion (Fig. 3), suggesting GTS. This prompted us to consider spondylectomy to prevent further progressive spinal compression after additional chemotherapy. Due to no qualified surgeon being available at our hospital, we planned to invite a specialist from a high‐volume center. We chose additional EP chemotherapy for the third course, due to severe nausea during the initial two BEP courses, mental fragility, surgery wait time, and our aim to minimize adverse events beforehand.

Fig. 2.

CT and MRI images of the second lumbar spine before and after two courses of BEP chemotherapy. The size of metastatic lesion and the degree of spinal cord compression have increased.

Fig. 3.

The primary left testicular tumor forms embryonic‐type neural tubules lined by primitive cells with scant cytoplasm and high nuclear to cytoplasmic (N/C) ratios. In vertebral biopsy after chemotherapy, neuroectodermal tissue lost its immaturity with reduced nuclear density and smaller nuclei, and in spondylectomy specimens, it changed to mature‐appearing glial tissue with abundant neurofibrillary matrix (hematoxylin and eosin staining, ×200).

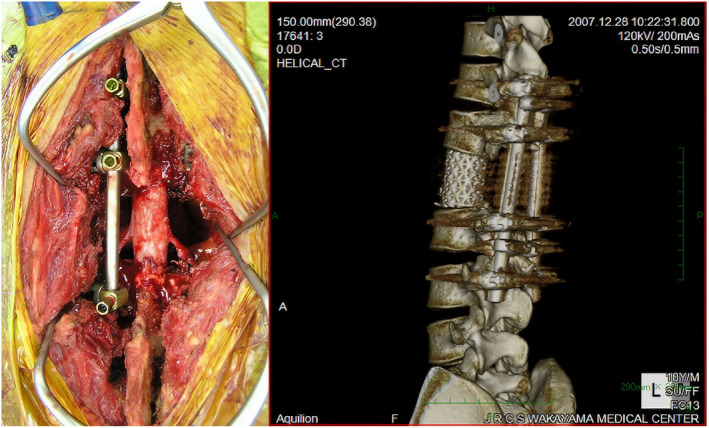

After AFP level normalized to 1.6 ng/mL, total spondylectomy of L2 vertebra was performed with anterior–posterior fusion and autogenous bone grafting (Fig. 4). The pathology of the vertebral body revealed the presence of mature teratoma without any evidence of immature component (Fig. 3) and positive resection margin. Following surgery, two cycles of adjuvant TIP chemotherapy were administered to maximize the curative effect. Regular follow‐up evaluations have revealed no evidence of recurrence. At present, the patient is 34 years old, alive, and leading an active social life.

Fig. 4.

On the left is a photograph of the surgical field after total en bloc spondylectomy and fixation, and on the right is a 3D composite CT image of the postoperative lumbar showing reconstruction of the spine with CD instrumentation and an AW glass–ceramic spacer augmented by allografts.

Discussion

Pure teratoma of the testis is rare, representing only 2%–6% of all primary testicular tumors and usually appears as a component of mixed germ cell tumors. Although histologically benign, the clinical course of primary pure teratoma is unpredictable. 1 Previously, teratomas were classified as mature and immature, but the 2018 Japanese handling rule now follows the WHO's classification. 2 Notably, the GCNIS component of teratomas is now considered malignant, regardless of cell differentiation. Even highly differentiated and benign‐appearing tumor cells in metastatic sites are still considered malignant. 1

Bone metastasis of NSGCT of the testes is rare, especially at initial presentation. Generally, bone lesions are discovered with concurrent retroperitoneal lymph node or visceral disease as a late manifestation. Our literature search identified only several published cases 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 of single bone metastasis at initial diagnosis, and none reported long‐term survival after radical vertebral surgery, as seen in the present case.

Furthermore, GTS is also rare (1.9%–7.6%) among patients with NSGCT who present with enlarging metastatic masses during appropriate systemic chemotherapy and in the context of normalized serum markers. Surgical resection remains the gold standard treatment for GTS since teratomas are resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. 8 The timing of surgery is particularly critical, as delayed intervention may result in more complicated procedures and potentially poorer outcomes. 9

In our case, GTS prompted surgical intervention, however, had the tumor continued to diminish in size with chemotherapy, alternative treatment may have been explored. For example, if radiotherapy was selected and the tumor failed to achieve CR, surgery would have finally become essential. Given the characteristics of teratomas, this scenario is likely. It is essential to approach the treatment plan with an understanding that surgery after radiotherapy involves higher risks and complexities. 9 Long‐term survival can be attributed to two key factors: solitary metastasis and successful vertebral surgery. The decision to pursue radical surgery rather than palliative treatment was influenced by both the isolated metastasis and young age. Kato et al. 10 examined the spinal metastasectomy outcomes in 124 patients with isolated spinal metastases of various malignancies, reporting 3‐ and 5‐year survival rates of 70% and 60%, and local recurrence and instrumentation failure rates of 10% and 22%, respectively. Although challenging, spinal metastasectomy can provide significant functional and survival benefits for well‐selected patients.

On the other hand, spondylectomy is a surgical procedure that preserves the spinal cord while resecting surrounding vertebrae, but this approach may not allow for the complete en bloc removal of all tumor tissue. Due to this limitation and positive resection margin with potential dissemination risk, we administered additional chemotherapy. While the need for two TIP chemotherapy courses is debatable, this aggressive approach may have improved outcomes.

Conclusion

Timely surgery and comprehensive treatment are essential for long‐term survival in testicular teratoma with vertebral metastasis, underscoring the importance of recognizing GTS early.

Author contributions

Masahiro Tamaki: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Kouhei Maruno: Resources. Tatsuya Hazama: Resources. Toshifumi Takahashi: Resources. Yuya Yamada: Resources. Masakazu Nakashima: Resources. Kazuro Kikkawa: Resources. Noriyuki Ito: Supervision.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Dr. Mutsumi Matsushita of Kurashiki Central Hospital (at the time) for performing the spondylectomy in this case. We would also like to thank Dr. Yasuyuki Tanaka, the attending orthopedic surgeon at our hospital, and Dr. Kazuo Ono, the pathologist at our hospital, for his valuable advice on the pathology findings.

References

- 1. Simmonds PD, Lee AH, Theaker JM, Tung K, Smart CJ, Mead GM. Primary pure teratoma of the testis. J. Urol. 1996; 155: 939–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Williamson SR, Delahunt B, Magi‐Galluzzi C et al. The World Health Organization 2016 classification of testicular germ cell tumours: a review and update from the International Society of Urological Pathology Testis Consultation Panel. Histopathology 2017; 70: 335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bosco P, Bihrle W 3rd, Malone MJ, Silverman ML. Primary skeletal metastasis of a nonseminomatous germ cell tumor. Urology 1994; 43: 564–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Benedetti G, Rastelli F, Fedele M, Castellucci P, Damiani S, Crinò L. Presentation of nonseminomatous germ cell tumor of the testis with symptomatic solitary bone metastasis. A case report with review of the literature. Tumori 2006; 92: 433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aldejmah A, Soulières D, Saad F. Isolated solitary bony metastasis of a nonseminomatous germ cell tumor. Can. J. Urol. 2007; 14: 3458–3460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chargari C, Macdermed D, Védrine L. Symptomatic solitary skull bone metastasis as the initial presentation of a testicular germ cell tumor. Int. J. Urol. 2010; 17: 100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Biebighauser KC, Gao J, Rao P et al. Non‐seminomatous germ cell tumor with bone metastasis only at diagnosis: a rare clinical presentation. Asian J. Urol. 2017; 4: 124–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gorbatiy V, Spiess PE, Pisters LL. The growing teratoma syndrome: current review of the literature. Indian J. Urol. 2009; 25: 186–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paffenholz P, Pfister D, Matveev V, Heidenreich A. Diagnosis and management of the growing teratoma syndrome: a single‐center experience and review of the literature. Urol. Oncol. 2018; 36: 529.e23–529.e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kato S, Demura S, Murakami H et al. Medium to long‐term clinical outcomes of spinal metastasectomy. Cancers 2022; 14: 2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]