Abstract

Background:

Sensory impairments, notably hearing loss (68% in those aged 70+) and vision loss (24%–50%), are prevalent in older individuals. We investigated the correlation between visual and hearing impairments in older adults, considering sociodemographic factors, mental health, and social support.

Methods:

The study is part of The Serbian 2019 National Health Survey, conducted in 2019. Questionnaires were used as the research tool, following the methodology of the European Health Survey. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess predictors of visual and hearing impairments.

Results:

Findings revealed a higher prevalence of vision difficulties among women (P< 0.001) and a significant reduction in reported vision issues with increased social support (P< 0.001). Higher education, particularly at the doctoral level, demonstrated a strong protective effect against hearing difficulties (P< 0.001).

Conclusion:

Education at the doctoral level provides significant protection against sensory difficulties, especially in the case of hearing loss, while a high level of social support positively influences the reduction of vision-related problems. Further research is necessary for a better understanding of relationships and the development of effective support strategies for the elderly population with vision and hearing impairments.

Keywords: Sensory limitations, Functional limitations, Vision loss, Hearing loss, Aging

Introduction

Public health faces escalating challenges due to aging demographics (1). The Who projects a substantial increase in the elderly population by 2050, particularly among those aged 80 and above (2,3). Aging often brings functional limitations, notably in hearing and vision, with around 68% of individuals aged 70 yr and above experiencing hearing loss, and vision loss affecting approximately 24% and 50% of those aged 70–79 and 80 and above (4–7).

Research confirms the impact of hearing loss on physical functioning, mental health, and social relationships among the elderly (8–16). Sensory impairments are often undervalued compared to chronic diseases, affecting various life domains and contributing to social isolation and mental health challenges (10–12). The interaction between sensory impairments and sociodemographic factors is crucial, including age, gender, education, income, and social status (8–10). Sensory impairments remain relative to other health issues, significantly affect communication, daily activities, and social participation (17–19).

This study aimed to investigate the correlation between visual and hearing impairments in older individuals, considering sociodemographic factors, mental health, and social support.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The study was a part of Serbia’s 2019 “Health Survey of the Population,” a national cross-sectional study conducted by the Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, in collaboration with the Institute of Public Health and the Ministry of Health. Methodology followed European Health Interview Survey (EHIS Wave 3) standards (20), with adherence to ethical guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants received detailed written study information and gave informed consent, with no collection of personally identifiable information to safeguard privacy.

Selection Criteria

The analysis is based on a sample of 3.705 participants aged 65 and above. The research spanned three months, from October to December, in 2019. The sample encompasses all households listed in all enumeration areas during the 2011 Census. Stratification was carried out based on the type of settlement (urban and other) and four regions: Belgrade Region, Vojvodina Region, Šumadija and Western Serbia Region, and Southern and Eastern Serbia Region.

Measurement Instruments

Participant data, including demographic and socioeconomic details, collected via interviews and validated surveys. Variables: age, gender, settlement, marital status, education, household wealth index. Participants categorized by age, residence, marital status. Education levels: no schooling, incomplete primary, secondary, higher education, master’s, or doctorate.

Functional limitations

Analysis of visual and hearing impairments via specific questions. Categories: functional vision limitations (eyewear usage, vision issues despite glasses) and functional hearing limitations (hearing aid usage, noisy environment struggles). Responses categorized: no difficulty, minor problems, major problems, or unable.

Wealth index

The Demographic and Health Survey Wealth Index, excluding income (21). Household wealth in Serbia is ranked into five socio-economic categories [5- wealthiest,4-rich, 3- middle class, 2- poor, and 1- poorest].

Social support

Social support was assessed based on Oslo-3 Social Support Scale, creating a score ranging from 3 to 15 points. Social support was classified as strong [12–15], moderate [9–11], or weak [3–8].

Mental health

Mental health was evaluated using the PHQ-8 questionnaire, providing a score from 0 to 24 points and categorizing depression as absent [0–4], mild [5–9], moderate [10–14], moderately severe [15–19], or severe [20–24].

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis involved SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), utilizing descriptive and inferential statistics, including Chi Square tests and logistic regression. Relevant variables considering significance at a 5% probability level from univariate analysis were entered into multivariate models, with only statistically significant variables retained. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis evaluated age’s predictive ability for identifying individuals with difficulty hearing in quiet spaces. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient assessed the internal consistency reliability of the Mental Health scale.

Results

In this study, 75.4% of participants reported using glasses or contact lenses, with 32.7% indicating minor and 7.3% significant vision difficulties even with corrective eyewear. Hearing aid usage was 5.2%, while 24.0% reported minor and 5.4% significant difficulties hearing in a quiet room.

Results in Table 1 show a statistically significant association between gender and functional limitation of FL2, with a higher percentage of women in all three examined categories (P<0.001).

Table 1:

Analysis of the relationship between vision limitations and socio- demographic characteristics of participants

| Variables | FL1.Do you wear glasses or contact lenses? | P* | FL2. Do you have difficulty seeing even when wearing glasses or contact lenses? Do you have vision difficulties? | P* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Yes(%) | No(%) | Blind or cannot see at all(%) | No difficulty(%) | Some difficulty(%) | A lot of difficulty(%) | |||

| GENDER | ||||||||

| Male | 1243(44.0) | 428(48.0) | 11(40.7) | 0.105 | 1069(48.0) | 516(42.50) | 86(31.7) | <0.001 |

| Female | 1581(56.0) | 464(52.0) | 16(59.3) | 1160(52.0) | 697(57.5) | 185(68.3) | ||

| AGE GROUPS | ||||||||

| 65–69 | 1057(37.4) | 298(33.4) | 3(11.1) | <0.001 | 935(41.9) | 374(30.8) | 46(17.0) | <0.001 |

| 70–74 | 741(26.2) | 217(24.3) | 5(18,5) | 635(28.5) | 272(22.4) | 51(18.8) | ||

| 75–79 | 487(17.2) | 151(16.9) | 3(11.1) | 343(15.4) | 238(19.6) | 57(21.0) | ||

| 80–84 | 353(12.5) | 130(14.6) | 8(29.6) | 219(9.8) | 203(16.7) | 59(21.8) | ||

| 85–89 | 143(5.1) | 76(8.5) | 5(18.5) | 78(3.5) | 100(8.2) | 40(14.8) | ||

| 90+ | 43(1.5) | 20(2.2) | 3(11.1) | 19(0.9) | 26(2.1) | 18(6.6) | ||

| MARITAL STATUS | ||||||||

| Single | 54(1.9) | 26(2.9) | 0(0.0) | <0.001 | 46(2.1) | 30(2.5) | 4(1.5) | <0.001 |

| Married/common law | 1680(59.6) | 484(54.3) | 9(33.3) | 1421(63.9) | 641(52.8) | 102(37.8) | ||

| Widiwed | 983(34.9) | 357(40.0) | 14(51.9) | 677(30.4) | 504(41.5) | 157(58.1) | ||

| Divorced | 102(3.6) | 25(2.8) | 4(14.8) | 81(3.6) | 38(3.1) | 7(2.6) | ||

| SETTLEMENT TYPE | ||||||||

| Urban | 1467(51.9) | 543(60.9) | 14(51.9) | <0.001 | 1219(54.7) | 646(53.3) | 143(52.8) | 0.653 |

| Other settlements | 1357(48.1) | 349(39.1) | 13(48.1) | 1010(45.3) | 567(46.7) | 128(47.2) | ||

| EDUCATION LEVEL | ||||||||

| No formal education | 110(3.9) | 105(11.8) | 4(14.8) | <0.001 | 69(3.1) | 99(8.2) | 47(17.4) | <0.001 |

| Incomplete primary school | 353(12.5) | 208(23.3) | 5(18.5) | 254(11.4) | 242(20.0) | 63(23.3) | ||

| Primary school | 668(23.7) | 274(30.7) | 8(29.6) | 513(23.0) | 347(28.6) | 82(30.4) | ||

| Secondary school | 1217(43.1) | 231(25.9) | 9(33.3) | 987(44.3) | 400(33.0) | 60(22.2) | ||

| Higher or vocational school | 435(15.4) | 70(7.8) | 1(3.7) | 367(16.5) | 120(9.9) | 18(6.7) | ||

| Master’s or doctorate | 39(1.4) | 4(0.4) | 0(0.0) | 39(1.7) | 4(0.3) | 0(0.0) | ||

| WEALTH INDEX | ||||||||

| Poorest | 459(16.3) | 282(31.6) | 7(25.9) | <0.001 | 364(16.3) | 295(24.3) | 82(30.3) | <0.001 |

| Poor | 597(21.1) | 6(22.2) | 463(20.8) | 276(22.8) | 69(25.5) | |||

| 212(23.8) | ||||||||

| Middle class | 648(22.9) | 177(19.8) | 4(14.8) | 502(22.5) | 261(21.5) | 60(22.1) | ||

| Rich | 602(21.3) | 135(15.1) | 6(22.2) | 474(21.3) | 225(18.5) | 38(14.0) | ||

| Wealthiest | 518(18.3) | 86(9.6) | 4(14.8) | 426(19.1) | 156(12.9) | 22(8.1) | ||

Chi Square test

Age categories and marital status were also statistically associated with functional limitations FL1 and FL2 (P<0.05). Respondents not using glasses or contact lenses, particularly those with a well-being index marked as 1-poorest, had the highest percentage (31.6%) (P<0.001).

Completion of high school was associated with the largest percentage 44.3% stating no vision problems (P<0.001).

Sociodemographic characteristics in Table 2, indicate that participants who stated that they do not use hearing aids, predominantly 37.1%, belong to the age groupof 65–69 years (P<0.001).

Table 2:

Analysis of the relationship between hearing limitations and socio- demographic characteristics of participants

| Variables | FL3. Do you use a hearing aid? | P* | FL4. Do you have difficulty hearing another person when talking to them in a quiet space (even when using a hearing aid)? | P* | FL5. Do you have difficulty hearing another person when talking to them in a noisier space (even when using a hearing aid)? | P* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| YES (%) | NO (%) | Deaf or cannot hear at all (%) | No difficulty (%) | Some difficulty (%) | A lot of difficulty (%) | No difficulty (%) | Some difficulty (%) | A lot of difficulty (%) | unable (%) | ||||

| GENDER | |||||||||||||

| Male | 93 (47.0) | 1585 (44.8) | 4(30.8) | 0.435 | 416 (46.5) | 86(42.4) | 0.475 | 875 (42.7) | 543 (45.7) | 236 (53.0) | 20 (47.6) | 0.001 | |

| Female | 102 (52.0) | 1950 (55.2) | 9(69.2) | 1455 (55.3) | 479 (53.5) | 117 (57.6) | 1174 (57.3) | 644 (54.3) | 209 (47.0) | 22 (52.4) | |||

| AGE GROUPS | |||||||||||||

| 65–69 | 43 (22.1) | 1312 (37.1) | 3(23.1) | <0.001 | 1136 (43.2) | 198 (22.1) | 21(10,3) | <0.001 | 728 (35.5) | 427 (36.0) | 177 (39.8) | 21 (50.0) | 0.001 |

| 70–74 | 39 (20.0) | 921 (26.1) | 3(23.1) | 736 (28.0) | 194 (21.7) | 28 (13.8) | 490 (23.9) | 340 (28.6) | 120 (27.0) | 11 (26.2) | |||

| 75–79 | 49 (25.1) | 590 (16.7) | 2(15.4) | 411 (15.6) | 189 (21.1) | 39 (19.2) | 361 (17.6) | 188 (15.8) | 78 (17.5) | 7(16.7) | |||

| 80–84 | 42 (21.5) | 446 (12.6) | 3(23.1) | 253 (9.6) | 183 (20.4) | 52 (25.6) | 277 (13.5) | 152 (12.8) | 54 (12.1) | 3(7.1) | |||

| 85–89 | 18(9.2) | 204 (5.8) | 2(15.4) | 73(2.8) | 104 (11.6) | 44 (21.7) | 144 (7.0) | 68(5.7) | 12 (2.7) | 0(0.0) | |||

| 90+ | 4(2.1) | 62(1.8) | 0(0.0) | 20(0.8) | 27 (3.0) | 19(9.4) | 49(2.4) | 12(1.0) | 4(0.9) | 0(0.0) | |||

| MARITAL STATUS | |||||||||||||

| Single | 2(1.0) | 77(2.2) | 1(7.7) | 0.315 | 62(2.4) | 16 (1.8) | 1(0.5) | <0.001 | 39(1.9) | 31(2.6) | 9(2.0) | 1(2.4) | 0.034 |

| Married/common law | 107 (55.2) | 2061 (58.4) | 5(38.5) | 1631 (62.1) | 449 (50.3) | 87 (42.9) | 1169 (57.20) | 672 (56.6) | 291 (65.5) | 27 (64.3) | |||

| Widiwed | 79 (40,7) | 1268 (35,9) | 7(53,8) | 830 (31.6) | 405 (45.4) | 110 (54.2) | 764 (37.4) | 441 (37.2) | 130 (29.3) | 13 (31.0) | |||

| divorced | 6(3.1) | 125 (3.5) | 0(0.0) | 103 (3.9) | 23 (2.6) | 5(2.5) | 73(3.6) | 43(3.6) | 14(3.2) | 1(2.4) | |||

| SETTLEMENT TYPE | |||||||||||||

| Urban | 97 (49.7) | 1918 (54.3) | 9(69.2) | 0.256 | 1448 (55.1) | 446 (49.8) | 119 (58.6) | 0.010 | 1106 (54.0) | 635 (53.5) | 249 (56.0) | 22 (52.4) | 0.838 |

| Other settlements | 98 (50.3) | 1617 (45.7) | 4(30.8) | 1181 (44.9) | 449 (50.2) | 84 (41.4) | 943 (46.0) | 552 (46.5) | 196 (44.0) | 20 (47.6) | |||

| EDUCATION LEVEL | |||||||||||||

| No formal education | 15(7.7) | 202 (5.7) | 2(15.4) | 0.143 | 75(2.9) | 99 (11.1) | 43 (21.2) | <0.001 | 148 (7.2) | 61 (5.1) | 9(2.0) | 0(0.0) | <0.001 |

| Incomplete primary school | 36 (18.6) | 529 (15.0) | 1(7.7) | 340 (12.9) | 168 (18.8) | 57 (28.1) | 319 (15.6) | 180 (15.2) | 58 (13.0) | 5(11.9) | |||

| Primary school | 35 (18.0) | 913 (25.8) | 2(15.4) | 652 (24.8) | 250 (28.0) | 46 (22.7) | 528 (25.8) | 310 (26.1) | 98 (22.0) | 9(21.4) | |||

| Secondary school | 75 (38.7) | 1374 (38.9) | 8(61.5) | 1123 (42.7) | 280 (31.3) | 43 (21.2) | 784 (38.3) | 461 (38.8) | 186 (41.8) | 20 (47.6) | |||

| Higher or vocational school | 30 (15.5) | 476 (13.5) | 0(0.0) | 407 (15.5) | 87 (9.7) | 12(5.9) | 255 (12.5) | 158 (13.3) | 82 (18.4) | 7(16.7) | |||

| Master’s or doctorate | 3(1.5) | 40(1.1) | 0(0.0) | 31(1.2) | 10 (1.1) | 2(1.0) | 13(0.6) | 17(1.4) | 12(2.7) | 1(2.4) | |||

| WEALTH INDEX | |||||||||||||

| Poorest | 33 (16.9) | 712 (20.1) | 3(23.1) | 0.063 | 465 (17.7) | 223 (24.9) | 57 (28.1) | <0.001 | 419 (20.4) | 243 (20.5) | 74 (16.6) | 10 (23.8) | 0.098 |

| Poor | 53 (27.2) | 757 (21.4) | 5(38.5) | 545 (20.7) | 219 (24.5) | 46 (22.7) | 423 (20.6) | 290 (24.4) | 89 (20.0) | 9(21.4) | |||

| Middle class | 42(21.5) | 784 (22.2) | 3(23.1) | 596 (22.7) | 185 (20.7) | 45 (22.2) | 478 (23.3) | 235 (19.8) | 103 (23.1) | 8(19.0) | |||

| Rich | 48 (24.6) | 694 (19.6) | 1(7.7) | 555 (21.1) | 151 (16.9) | 34 (16.7) | 413 (20.2) | 228 (19.2) | 90 (20.2) | 8(19.0) | |||

| Wealthiest | 19(9.7) | 588 (16.6) | 1(7.7) | 468 (17.8) | 117 (13.1) | 21 (10.3) | 316 (15.4) | 191 (16.1) | 89 (20.0) | 7(16.7) | |||

Chi Square test

The highest percentage of all respondents 25.6% experiencing significant difficulties in hearing another person in a quiet space falls within the age group of 80–84 years (P<0.001). Of all respondents who reported great difficulty hearing another person in a quiet space, the highest percentage 28.1% had incomplete primary school education (P<0.001).

The value of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of internal consistency for the Mental Health scale was 0.846. The mental health score (Table 3) was statistically significantly associated with all the mentioned functional limitations (P<0.05).

Table 3:

Influence of mental health and social support on functional limitations

| FL1. Do you wear glasses or contact lenses? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | YES (%) | NO (%) | Blind or cannot see at all (%)4 | P * | |

| MENTAL HEALTH | |||||

| No symptoms of depression | 2238(82.6) | 659(80.3) | 8(42.1) | <0.001 | |

| Mild symptoms of depression | 354(13.1) | 118(14.4) | 5(26.3) | ||

| Moderate depressive episode | 76(2.8) | 26(3.2) | 3(15.8) | ||

| Moderately severe depressive episode | 30(1.1) | 15(1.8) | 1(5.3) | ||

| Severe depressive episode | 11(0.4) | 3(0.4) | 2(10.5) | ||

| SOCIAL SUPPORT | |||||

| Poor social support | 2268(85.5) | 695(85.9) | 16(88.9) | 0.981 | |

| Moderate social support | 376(14.2) | 112(13.8) | 2(11.1) | ||

| Strong social support | 9(0.3) | 2(0.2) | 0(0.0) | ||

| FL2. Do you have difficulty seeing even when wearing glasses or contact lenses? Do you have vision difficultie | |||||

| MENTAL HEALTH | |||||

| No symptoms of depression | 1919(89.4) | 852(74.3) | 124(53.0) | <0.001 | |

| Mild symptoms of depression | 185(8.6) | 221(19.3) | 66(28.2) | ||

| Moderate depressive episode | 34(1.6) | 43(3.8) | 25(10.7) | ||

| Moderately severe depressive episode | 6(0.3) | 25(2.2) | 13(5.6) | ||

| Severe depressive episode | 3(0.1) | 5(0.4) | 6(2.6) | ||

| SOCIAL SUPPORT | |||||

| Poor social support | 1831(87.3) | 949(84.1) | 181(77.7) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate social support | 264(12.6) | 175(15.5) | 48(20.6) | ||

| Strong social support | 3(0.1) | 4(0.4) | 4(1.7) | ||

| FL3. Do you use a hearing aid? | |||||

| MENTAL HEALTH | 0.007 | ||||

| No symptoms of depression | 130 (73.0) | 2772 (82.4) | 3 (60.0) | ||

| Mild symptoms of depression | 32 (18.0) | 444 (13.2) | 1 (20.0) | ||

| Moderate depressive episode | 10 (5.6) | 94 (2.8) | 1 (20.0) | ||

| Moderately severe depressive episode | 3 (1.7) | 43 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Severe depressive episode | 3 (1.7) | 13 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| SOCIAL SUPPORT | |||||

| Poor social support | 138 (79.3) | 2836 (85.9) | 5 (100.0) | 0.095 | |

| Moderate social support | 36 (20.7) | 454 (13.8) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Strong social support | 0 (0.0) | 11 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| FL4. Do you have difficulty hearing another person when talking to them in a quiet space (even when using a hearing aid)? | |||||

| MENTAL HEALTH | |||||

| No symptoms of depression | 2240(87.8) | 579(69.0) | 83(53.9) | <0.001 | |

| Mild symptoms of depression | 255(10.0) | 185(22.1) | 36(23.4) | ||

| Moderate depressive episode | 33(1.3) | 53(6.3) | 18(11.7) | ||

| Moderately severe depressive episode | 16(0.6) | 17(2.0) | 13(8.4) | ||

| Severe depressive episode | 7(0.3) | 5(0.6) | 4(2.6) | ||

| SOCIAL SUPPORT | |||||

| Poor social support | 2189(87.4) | 666(81.4) | 118(77.6) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate social support | 309(12.3) | 148(18.1) | 33(21.7) | ||

| Strong social support | 6(0.2) | 4(0.5) | 1(0.7) | ||

| FL5. Do you have difficulty hearing another person when talking to them in a noisier space (even when using a hearing aid)? | |||||

| MENTAL HEALTH | |||||

| No symptoms of depression | 1537(80.0) | 940(82.8) | 379(87.7) | 37(88.1) | 0.034 |

| Mild symptoms of depression | 274(14.3) | 149(13.1) | 43(10.0) | 4(9.5) | |

| Moderate depressive episode | 65(3.4) | 32(2.8) | 7(1.6) | 1(2.4) | |

| Moderately severe depressive episode | 32(1.7) | 12(1.1) | 2(0.5) | 0(0.0) | |

| Severe depressive episode | 13(0.7) | 2(0.2) | 1(0.2) | 0(0.0) | |

| SOCIAL SUPPORT | |||||

| Poor social support | 1588(84.4) | 969(87.0) | 373(87.8) | 38(90.5) | 0.025 |

| Moderate social support | 285 (15.2) | 144 (12.9) | 51(12.0) | 3(7.1) | |

| Strong social support | 8(0.4) | 1(0.1) | 1(0.2) | 1(2.4) | |

Chi Square test

The highest percentage of respondents 89.4% without visual difficulties did not exhibit symptoms of depression (P<0.001). In all categories of investigated limitations (without difficulties, with minor difficulties, with significant difficulties, unable), respondents without symptoms of depression and those with poor social support were dominantly represented (P<0.001).

Based on the analyze in Table 4,individuals who belong to the wealthiest category were 2,274 times more likely to wear glasses or contact lenses compared with individuals who belong to the poorest category.

Table 4:

Determining factors significant for vision and hearing: univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis

| Variables | Univariate Logistic Regression | Multivariate Logistic Regression* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Odds ratio (95%CI) | P | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P | |

| FO1. Do you wear glasses or contact lenses(0-No; 1-Yes) | ||||

| Well-being index | ||||

| I-poorest | 1 | 1 | ||

| V- Wealthiest | 3.673 (2.799–4.820) | <0.001 | 2.274 (1.596–3.242) | <0.001 |

| Education Level | ||||

| No formal education | 1 | 1 | ||

| Doctorate | 8.980 (3.103–25.988) | <0.001 | 3,891(1,104–13,72) | 0.035 |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Unemployed | 1 | 1 | ||

| Retired | 3.823 (2,585–5,655) | <0.001 | 4.144 (2.108–8.148) | <0.001 |

| FO2. Do you have difficulty seeing even when wearing glasses or contact lenses? Do you have vision difficulties?(0-Not having difficulties; 1-Having difficulties) | ||||

| Education Level | ||||

| No formal education | 1 | 1 | ||

| Doctorate | 0.048(0.017–0.141) | <0.001 | 0.088(0.022–0.345) | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.072(1.061–1.082) | <0.001 | 1.038 (1.017–1.060) | <0.001 |

| Mental Health Score | 1.196(1.168–1.224) | <0.001 | 1.087(1.042–1.134) | <0.001 |

| Social Support Score | 1.132(1.080–1.186) | <0.001 | 1.153(1.056–1.259) | <0.001 |

| FO3. Do you use a hearing aid? (0-No; 1-Yes) | ||||

| Age | 1.055(1.034–1.075) | <0.001 | 1.057(1.033–1.082) | <0.001 |

| FO4. Do you have difficulty hearing another person when talking to them in a quiet space (even when using a hearing aid)?(0-Not having difficulties; 1-Having difficulties) | ||||

| Age | 1.113(1.101–1.126) | <0.001 | 1,088(1,063–1,113) | <0.001 |

| Education Level | ||||

| No formal education | 1 | 1 | ||

| Doctorate | 0.628(0.312–1.267) | 0.194 | 0.371(0.147–0.937) | 0.036 |

| Mental Health Score | 1.178(1.152–1.204) | <0.001 | 1.092(1.047–1.138) | <0.001 |

| Social Support Score | 1.136(1.080–1.195) | <0.001 | 1.186(1.081–1.302) | <0.001 |

| FO5. Do you have difficulty hearing another person when talking to them in a noisier space (even when using a hearing aid)?(Not having difficulties; 1-Having difficulties) | ||||

| Education Level | ||||

| No formal education | 1 | 1 | ||

| Doctorate | 0.420(0.214–0.823) | 0.012 | 0.443(0.225–0.875) | 0.025 |

1-Reference category

*Adjusted for type of settlement, well-being index, level of education, work status, self-assessment of health, presence of hypertension, visit to a specialist doctor, unfulfilled need for health care due to financial reasons, age, mental health score and social support score

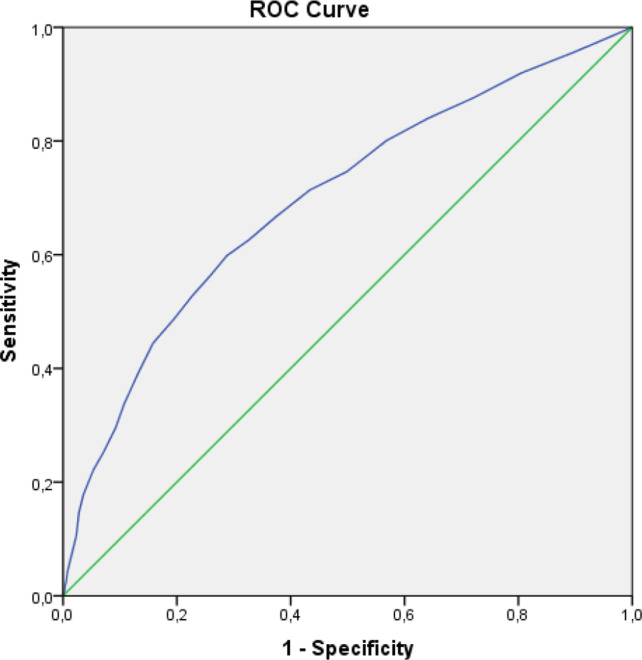

It indicates that individuals with a doctoral degree were by 91.2% less likely of experiencing vision difficulties compared with individuals without formal education. For each one-unit increase in age, the odds of using a hearing aid increased by 5.7%. In Fig. 1, ROC curve indicates that age is a good predictor of belonging to the group that has difficulties hearing another person when talking to them in a quiet space (AUC=0.696, 95%CI: 0.677–0.715). At a threshold of 71.5 years, the sensitivity was 71.4% and the specificity was 43.4%.

Fig. 1:

ROC Curve for age and hearing difficulty in quiet spaces

Discussion

Findings suggest a gender disparity in vision-related difficulties, with women more frequently reporting such challenges compared to male respondents.

We observed that widows/widowers and individuals with lower education levels are more prone to experiencing issues with both vision and hearing. Previous research has highlighted the significant impact of spousal loss on emotional and social well-being, potentially influencing overall health outcomes (22). Results corroborate these findings, reinforcing the link between widow-hood, lower educational attainment, wealth index, and sensory difficulties (6–18, 23–24). This aligns with existing literature that identifies similar patterns and risk factors associated with vision problems across various demographic groups. The individuals with completed primary education had the highest proportion of significant hearing difficulties in quiet environments.

This aligns with Bauer et al ‘s study, which demonstrated that older adults with more years of formal education tend to report fewer hearing complaints (25).Study underscores the protective effect of education on auditory function, particularly evident among those with a completed doctorate. This underscores the complex relationship between education and sensory perception, likely due to cognitive advantages like increased cognitive reserve and flexibility.

Higher social support scores are linked to fewer sensory limitations, particularly in vision.

Global studies are emphasizing the link between social support and sensory health (26–30). Research from Canada (26) and China (27) suggests that social isolation contributes to sensory impairments and loneliness, among older adults. Individuals self-reporting visual difficulties tend to show a tendency for reduced engagement in activities outside the home and social activities (28). Yu et al ‘s (27) findings indicate a bidirectional relationship between loneliness and the severity of visual impairments, emphasizing the role of social connections in stress reduction and emotional well-being. This finding underscores how a sense of support and connection with others can have a beneficial effect on stress reduction, improvement of emotional well-being, and preservation of sensory functions.

These studies highlight the complexity of the relationship between social interactions and sensory perception, calling for further research and the development of support strategies to enhance the sensory well-being of the older population.

According to the findings of studies (29), a statistically significant correlation is observed between hearing loss and an increased propensity for expressing social isolation. Our research explores the significance of specific demographic factors, including gender, in the context of the perception of social isolation associated with hearing loss. Research demonstrates a significant correlation between hearing loss and increased social isolation, with women in the older population facing a higher risk of isolation due to hearing impairment. Findings mirror those of previous studies, highlighting the specific challenges faced by women in terms of social interaction and hearing loss (29, 30).

The collective evidence underscores the necessity for targeted interventions and tailored support to address social isolation among older individuals with vision and hearing impairments.

Considering the association between social isolation and mental well-being, it is crucial to prioritize mental health in support strategies. Further research is warranted to comprehensively understand the complex interplay between health conditions, mental health, and social factors, facilitating the development of effective interventions.

Conclusion

Education, particularly at the doctoral level, significantly reduces sensory difficulties, especially hearing impairment. Women are more prone to social isolation due to hearing loss, highlighting the importance of social support.

Further research is necessary to understand these complexities fully and developeffective strategies to support older individuals with vision and hearing impairments, addressing social isolation and promoting mental well-being.

Journalism Ethics considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

There was no financial source for this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.WHO (2012). 10 facts on ageing and the life course.(accesed:26/1/23); https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/336671/WHO-EURO-2012-2224-41979-57739-eng.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

- 2.Economic Policy Committee (2009). The 2009 ageing report: economic and budgetary projections for the EU-27 Member States (2008–2060).

- 3.WHO . Ageing and Health Report. (accessed 28.7.2023). Available online:https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

- 4.Nguyen VC, Moon S, Oh E, et al. (2022). Factors associated with functional limitations in daily living among older adults in Korea: A cross-sectional study. Int J Public Health, 67:1605155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton MJ, Ramke J, Marques AP, et al. (2021). The Lancet Global Health commission on Global Eye Health: vision beyond 2020. Lancet Glob Health, 9(4): e489–e551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ge S, McConnell ES, Wu B, et al. (2021). Longitudinal association between hearing loss, vision loss, dual sensory loss, and cognitive decline. J Am Geriatr Soc, 69(3): 644–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo R, Li X, Sun M, et al. (2023). Vision impairment, hearing impairment and functional limitations of subjective cognitive decline: a population-based study. BMC Geriatr, 23(1): 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang S, Wang Q, Wang X, et al. (2022). Longitudinal relationshipbetween sensory impairments and depressive symptoms in older adults: The mediating role of functional limitation. Depress Anxiety, 39(8–9): 624–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao X, Zhou Y, Wei K, et al. (2021). Associations of sensory impairment and cognitive function in middle-aged and older Chinese population: The China health and retirement longitudinal study. J Glob Health, 11: 08008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maharani A, Dawes P, Nazroo J, et al. (2018). Visual and hearing impairments are associated with cognitive decline in older people. Age Ageing, 47(4): 575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parada H, Laughlin GA, Yang M, et al. (2021). Dual impairments in visual and hearing acuity and age-related cognitive decline in older adults from the Rancho Bernardo Study of Healthy Aging. Age Ageing, 50(4): 1268–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverstein SM, Sörensen S, Sunkara A, et al. (2021). Association of vision loss and depressive symptomatology in older adults assessed for ocular health in senior living facilities. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt, 41(5): 985–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayro EL, Murchison AP, Hark LA, et al. (2021). Prevalence of depressive symptoms and associated factors in an urban, ophthalmic population. Eur J Ophthalmol, 31: 740–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marques T, Marques FD, Miguéis A. (2022). Age-related hearing loss, depression and auditory amplification: a randomized clinical trial. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 279(3): 1317–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu A, Liljas A. (2019). The relationshipbetween self-reported sensory impairments and psychosocial health in older adults: a 4-year follow-up study using the English longitudinal study of ageing. Public Health, 169: 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun W, Matsuoka T, Imai A, et al. (2021). Effects of hearing impairment, quality of life and pain on depressive symptoms in elderly people: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18(22): 12265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Q, Zhang S, Wang Y, et al. (2022). Dual sensory impairment as a predictor of loneliness and isolation in older adults: National cohort study. JMIR Public Health Surveill, 8(11): e39314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Igarashi A, Aida J, Yamamoto T, et al. (2021). Associations between vision, hearing and tooth loss and social interactions: the JAGES cross-sectional study. J Epidemiol Community Health, 75(2): 171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yorgason JB, Tanner CT, Richardson S, et al. (2022). The longitudinal association of late-life visual and hearing difficulty and cognitive function: The role of social isolation. J Aging Health, 34(6–8): 765–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Health Interview Survey (EHIS wave 3) - Methodological manual, Eurostat, 2018.

- 21.Jankovic J, Simic S, Marinkovic J. (2010). Inequalities that hurt: demographic, socio-economic and health status inequalities in the utilization of health services in Serbia. Eur J Public Health, 20(4):389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joksimović Krstić K. (PhD thesis). Trajectories of coping with the death of a spouse in old age–a prospective diary study. University of NoviSad, Serbia; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rong H, Lai X, Jing R, et al. (2020). Association of sensory impairments with cognitive decline and depression among older adults in China. JAMA Netw Open, 3(9): e2014186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuller-Thomson E, Nowaczynski A, MacNeil A. (2022). The association between hearing impairment, vision impairment, dual sensory impairment, and serious cognitive impairment: findings from a population-based study of 5.4 million older adults. J Alzheimers Dis Rep, 6(1): 211–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bauer MA, Zanella ÂK, Filho IG, et al. (2017). Profile and prevalence of hearing complaints in the elderly. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol, 83(5): 523–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hämäläinen A, Phillips N, Wittich W, et al. (2019). Sensory-cognitive associations are only weakly mediated or moderated by social factors in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Sci Rep, 9(1): 19660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu K, Wu S, Jang Y, et al. (2021). Longitudinal assessment of the relationships between geriatric conditions and loneliness. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 22(5): 1107–1113.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heyl V, Wahl H-W, Mollenkopf H. (2005). Visual capacity, out-of-home activities and emotional well-being in old age: Basic relations and contextual variation. Social Indicators Research, 74(1): 159–189. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mick P, Kawachi I, Lin FR. (2014). The association between hearing loss and social isolation in older adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 150(3): 378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shukla A, Harper M, Pedersen E, et al. (2020). Hearing Loss, loneliness, and social isolation: A systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 162(5): 622–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]