Abstract

Background:

The aim was to explore the relationships among employment pressure, ego depletion, negotiable fate, and recent graduates’ suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

A total of 2703 recent graduates completed two times questionnaires that measured employment pressure, ego depletion, negotiable fate and suicidal ideation in the current study.

Results:

1) employment pressure positively predicts suicidal ideation among recent graduates; 2) ego depletion mediates the association between employment pressure and recent graduates’ suicidal ideation; and 3) negotiable fate moderates the associations of employment pressure with ego depletion and suicidal ideation, while the relationships of employment pressure with ego depletion and suicidal ideation are stronger for recent graduates with a strong belief in negotiable fate.

Conclusion:

Ego depletion and negotiable fate play a significant role between employment pressure and recent graduates’ suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic. This still needs to be noted in the post-epidemic era.

Keywords: Employment pressure, Ego depletion, Negotiable fate, Suicidal ideation, COVID-19 pandemic

Introduction

In 2020, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) spread worldwide and was declared a global public health incident (1). The contagious and harmful nature of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted governments to take precautionary measures such as enforcing home quarantine, closures, and online instruction, which, while essential to guaranteeing the public safety of individuals, led to a range of negative psychological outcomes, such as internet addiction and suicidal ideation (2, 3).

The incidence of college students’suicidal ideation increased from 8.5% to 14.3% during the February–June 2020 period (4, 5). Therefore, an in-depth study of the risk and protective factors of college students’suicidal ideation has important practical implications for reducing and preventing suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Employment pressure is a physiological, psychological, and behavioral stress process caused by internal and external pressures experienced by individuals while searching for jobs and making career choices (6). During the graduation season, recent graduates are susceptible to negative psychological and emotional behaviors such as depression, psychological stress, and anxiety under dual employment and academic pressure (7). Affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the COVID-Zero Policy, the temporary economic shutdown triggered by the pandemic caused a wave of layoffs and closures for many businesses, resulting in a significant reduction in employment opportunities and increasing recent graduates’employment pressure (8, 9). Employment pressure significantly increases suicidal ideation and suicide risk (10). Thus, this study proposed Hypothesis 1 (H1): Employment pressure significantly and positively predicts recent graduates’ suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the limited resource (LRM) model, within a limited time, individuals’ self-control, psychological resources, and energy are limited; when they need to be psychologically regulated, their self-regulatory resources are consumed or even depleted, this tends to result in a state of weak self-control, which is termed ego depletion (11). When individuals experience ego depletion, they tend to resort to more avoidant coping strategies, leading to a decrease in their self-esteem and self-identity; additionally, their suicidal schema is more likely to be activated (12). Therefore, ego depletion may increase suicidal ideation among recent graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic. On the other hand, many situations and behaviors deplete an individual’s self-control and psychological resources, such as stress coping and emotion regulation, causing ego depletion (13). Employment risk factors, such as hiring suspensions, pay cuts, and layoffs in some industries, prompted adverse emotions such as anxiety, and psychological stress in recent graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic (14). In the face of these negative experiences, recent graduates have attempted to mitigate negative emotions through self-regulation. This process consumes a large amount of self-regulatory psychological resources which in turn weakens their coping ability and thus accelerates the depletion of self-resources (15). In summary, we propose Hypothesis 2 (H2): Employment pressure positively correlates with suicidal ideation through the mediation of ego depletion among recent graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Negotiable fate, as an important cultural psychological belief (16), refers to an individual’s belief in his or her capacity to bargain or deal with his or her fate, exercise initiative within the constraints of the existing environment, and realize life goals and values through his or her efforts (17). Therefore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, recent graduates who firmly believed in the concept of negotiable fate exhibited more proactive adaptation to adversity, particularly when facing employment pressure, ultimately lowering the risk of suicidal ideation and ego depletion. Thus, this study proposed Hypothesis 3 (H3): negotiable fate moderates both the direct impact of employment pressure on suicidal ideation and the initial segment of the mediating pathway connecting employment pressure to ego depletion.

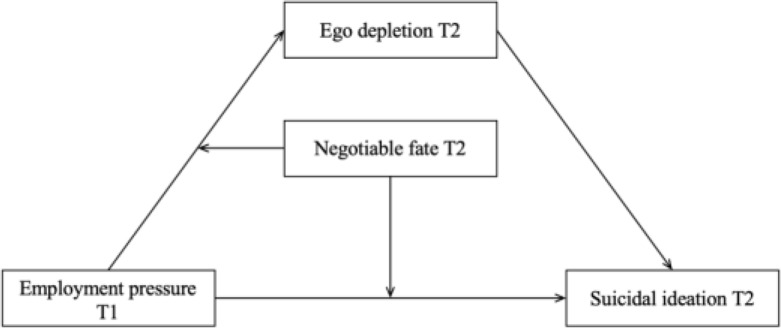

In general, this study endeavors to create a moderated longitudinal mediation model (Fig. 1) to investigate how employment pressure impacts suicidal ideation among recent graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fig. 1:

The moderated mediation model

Methods

Participants

Recent graduates from eleven universities in four provinces and cities of China were selected for the study and followed up at two time points over a period of one year. The first survey (T1, May, 2021) investigated demographic variables and employment pressure among 2882 recent graduates, and the second survey (T2, May, 2022) investigated ego depletion, negotiable fate, and suicidal ideation among 2703 recent graduates. There were 1326 male students (49.1%) and 1377 female students (50.9%), and the mean age was 21.06 years (SD = 1.78).

Measures

Employment pressure

Employment pressure was measured using the Employment Pressure Questionnaire (18). The scale consists of 4 items. Scoring is conducted on a 5-point Likert scale, where higher scores indicate higher levels of employment pressure experienced by the individual. In the current study, Cronbach’s α was 0.89.

Ego depletion

Ego depletion was measured using the Chinese version of the Self-Regulatory Fatigue Scale (19) and revised and validated by Wang et al (20). The scale consists of 16 items. Scoring is performed on a 5-point Likert scale, where higher individual scores correspond to increased levels of ego depletion. In the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.93.

Negotiable fate

The assessment of negotiable fate utilized the Negotiable Fate Scale, initially formulated by Chaturvedi et al (17) and subsequently revised and validated by Chang (21). The scale consists of 6 items. Scoring is conducted on a 5-point Likert scale; the higher the individual score is, the greater the belief in negotiable fate. In the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.94.

Suicidal ideation

The assessment of suicidal ideation employed the Suicidal Ideation Scale, originally developed by Osman et al (22) and subsequently revised and validated by Wang et al (23). The scale consists of 14 items. The scores were calculated on a 5-point Likert scale, where higher scores indicate a greater degree of suicidal ideation. In the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.90.

Data analysis

Initially, we conducted descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis on the gathered data using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Subsequently, Model 4 within the SPSS macro program PROCESS was employed to examine the mediating role of ego depletion, and Model 8 was employed to examine the moderating role of negotiable fate.

Ethical Statement

All procedures performed in the present study were approved by the Human Research Protection at the Fujian Polytechnic Normal University (Number: HR597–2021) and in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Results

Preliminary analyses

The descriptive statistics and correlations of employment pressure, ego depletion, negotiable fate, and suicidal ideation with the covariates are presented in Table 1. Employment pressure at T1 was positively correlated with suicidal ideation at T2 (r = 0.25, P< 0.01) and negatively associated with ego depletion at T2 and negotiable fate at T2 (r = −0.29, P< 0.01 and r = −0.43, P< 0.01, respectively). In addition, ego depletion at T2 was negatively correlated with suicidal ideation at T2 (r = −0.46, P< 0.01) and positively correlated with negotiable fate at T2 (r = 0.26, P< 0.01). Finally, negotiable fate at T2 was negatively correlated with suicidal ideation at T2 (r = −0.38, P< 0.01).

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics and correlations of the primary study variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Sex | - | |||||

| 2 SES | 0.06 | - | ||||

| 3 Employment pressure at T1 | −0.03 | −0.28** | - | |||

| 4 Ego depletion at T2 | −0.18** | −0.17** | 0.21** | - | ||

| 5 Negotiable fate at T2 | 0.07 | 0.13** | −0.07** | −0.17** | - | - |

| 6 Suicidal ideation at T2 | −0.14** | −0.25** | 0.34** | 0.44** | −0.13** | - |

| M | 0.52 | 4.30 | 2.86 | 2.90 | 3.14 | 2.00 |

| SD | 0.50 | 1.21 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 1.09 |

Note. Sex: 0 = female, 1 = male; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2.

P< 0.05,

P< 0.01,

P< 0.001

Testing for mediating effects of ego depletion

Initially, Model 4 of PROCESS 3.5 was employed to examine the mediating impact of ego depletion. As depicted in Table 2, after accounting for sex and socioeconomic status, the findings revealed a positive association between employment pressure at T1 and ego depletion at T2 (β = 0.19, P< 0.001). Subsequently, ego depletion exhibited a negative influence on suicidal ideation at T2 (β = 0.37, P< 0.001). Additionally, the remaining direct effect (from employment pressure at T1 to suicidal ideation at T2) remained significant (β= 0.24, P< 0.001). This signifies that ego depletion mediated the connection between employment pressure and suicidal ideation (indirect effect = 0.07, bootstrap 95% CI [0.05, 0.11]). The mediated impact accounted for 23.33% of the overall effect.

Table 2:

Testing for the mediating role of ego depletion at T2.

| Variables | Predictors | β | SE | t | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI at T2 | Sex | −0.11 | 0.02 | −3.51*** | [−0.14, −0.08] |

| SES | −0.15 | 0.02 | −4.42*** | [−0.16, −0.06] | |

| EP at T1 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 18.87*** | [0.23, 0.34] | |

| R2 | 0.13 | ||||

| F | 156.23 | ||||

| ED at T2 | Sex | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.05 | [−0.14, 0.08] |

| SES | −0.12 | 0.03 | −2.76*** | [−0.13, −0.02] | |

| EP at T1 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 11.03*** | [0.16, 0.24] | |

| R2 | 0.06 | ||||

| F | 121.56 | ||||

| SI at T2 | Sex | 0.07 | 0.02 | 1.55 | [−0.01, 0.16] |

| SES | −0.10 | 0.02 | −4.61*** | [−0.14, −0.06] | |

| EP at T1 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 15.45*** | [0.20, 0.30] | |

| ED at T2 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 22.45*** | [0.33, 0.42] | |

| R2 | 0.25 | ||||

| F | 263.27 |

Note. Employment pressure = EP; Ego depletion = ED; Negotiable fate = NF; Suicidal ideation = SI. Sex: 0 = female, 1 = male; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2

Testing for moderating effects of negotiable fate

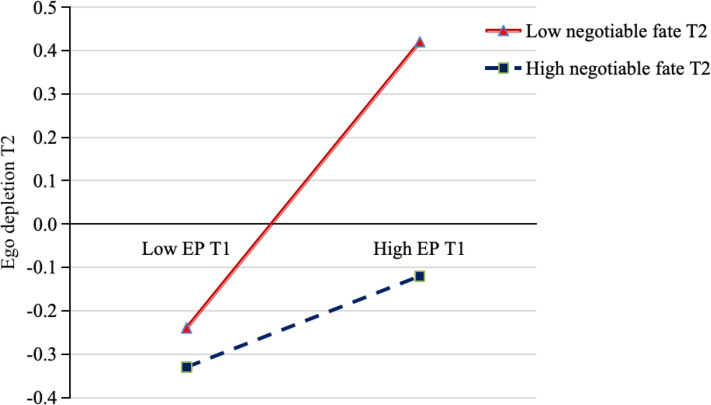

Second, Model 8 of PROCESS 3.5 was used to test the moderating effect of negotiable fate on the relationship between employment pressure and suicidal ideation. As shown in Table 3, after controlling for sex and socioeconomic status, Model 1 indicated that employment pressure at T1 was significantly and positively associated with ego depletion at T2 (β = 0.20, P< 0.001). Moreover, employment pressure at T1× negotiable fate at T2 was negatively related to ego depletion at T2 (β = −0.14, P< 0.01). Simple slope analysis indicated that among recent graduates exhibiting a lower belief in negotiable fate at T2 (M −1SD), increased employment pressure at T1 was linked to higher levels of ego depletion at T2 (Bsimple = 0.29, P< 0.001). Additionally, for recent graduates with a strong belief in negotiable fate at T2 (M +1SD), the effect of employment pressure at T1 on ego depletion at T2 was much weaker (Bsimple = 0.09, P> 0.05) (Fig. 2). Therefore, for recent graduates with a less strong belief in negotiable fate, employment pressure at T1 emerged as a notably more influential predictor of ego depletion at T2.

Table 3:

Testing for the moderating role of negotiable fate at T2

| Variables | Predictors | β | SE | t | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED at T2 | Sex | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.69 | [−0.15, 0.07] |

| SES | −0.10 | 0.03 | −3.95** | [−0.13, −0.02] | |

| EP at T1 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 11.67*** | [0.15, 0.24] | |

| NF at T2 | −0.22 | 0.02 | −10.94*** | [−0.26, −0.18] | |

| EP at T1× NF at T2 | −0.14 | 0.02 | −7.46** | [−0.18, −0.10] | |

| R2 | 0.09 | ||||

| F | 86.13 | ||||

| SI at T2 | Sex | −0.10 | 0.05 | −2.10** | [−0.12, −0.03] |

| SES | −0.07 | 0.03 | −2.36** | [−0.08, −0.01] | |

| ED at T2 | 0.35 | 0.02 | 20.97*** | [0.26, 0.38] | |

| EP at T1 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 15.97*** | [0.21, 0.29] | |

| NF at T2 | −0.08 | 0.02 | −4.23*** | [−0.11, −0.04] | |

| EP at T1× NF at T2 | −0.07 | 0.02 | −4.48** | [−0.10, −0.04] | |

| R2 | 0.26 | ||||

| F | 240.49 |

Note. Employment pressure = EP; Ego depletion = ED; Negotiable fate = NF; Suicidal ideation = SI. Sex: 0 = female, 1 = male; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2

Fig. 2:

Conditional effect of recent graduates’ ego depletion at T2 as a function of employment pressure at T1 and negotiable fate at T2. Note. EP = employment pressure; T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2; N = 2703

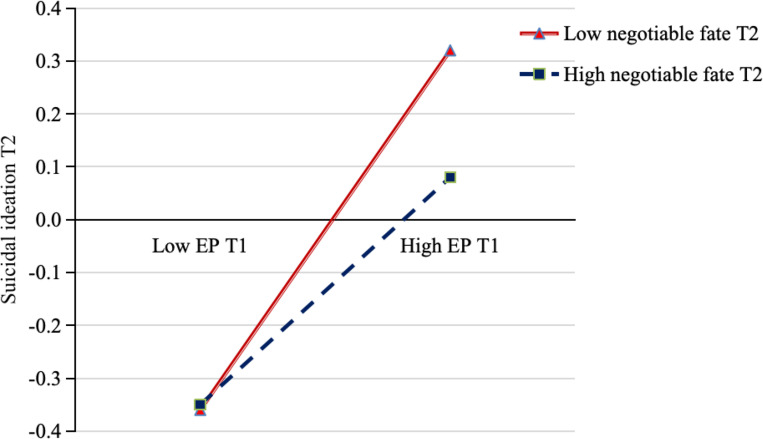

Model 2 indicates that employment pressure at T1 was significantly and positively related to suicidal ideation at T2 among recent graduates (β = 0.25, P< 0.001). In addition, employment pressure at T1× negotiable fate at T2 was negatively related to suicidal ideation at T2 among recent graduates (β = −0.07, P< 0.01). Simple slope analysis demonstrated that among recent graduates exhibiting a weaker belief in negotiable fate at T2 (M−1SD), increased employment pressure at T1 correlated with a heightened degree of suicidal ideation at T2 (Bsimple = 0.29, P< 0.001). However, for recent graduates with a strong belief in negotiable fate at T2 (M +1SD), the effect of employment pressure at T1 on suicidal ideation at T2 was much weaker (Bsimple = 0.19, P> 0.05) (Fig. 3). Consequently, among recent graduates with a weaker belief in negotiable fate, employment pressure at T1 emerged as a significantly more potent predictor of suicidal ideation at T2.

Fig. 3:

Conditional effect of recent graduates’ suicidal ideation at T2 as a function of employment pressure at T1 and negotiable fate at T2. Note. EP = employment pressure; T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2; N = 2703

Discussion

Employment pressure and suicidal ideation

The current study demonstrated a significant positive association between employment pressure and suicidal ideation among recent graduates. H1 was supported. Recent graduates are in an important stage of moving from school to society, and employment pressure is the greatest psychological stressor at this stage (24). For these individuals, successful employment is related to material and economic satisfaction, personal independence, and the realization of life value. Graduates who encounter negative events such as setbacks or failures in the job search process easily experience negative emotions such as frustration and disappointment (9). Therefore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, economic downturns resulted in a discrepancy between the employment goals and expectations of recent graduates and the actual situation, and suicidal ideation could be induced.

The mediating role of ego depletion

The study revealed that ego depletion acts as a mediator in the link between employment pressure and suicidal ideation among recent graduates, confirming hypothesis H2. In the context of the pandemic, university graduates had no clear idea when the pandemic would end, and the normal job search process was disrupted (25). As a result, recent graduates were prone to depleting their limited psychological energy, i.e., self-control resources, when coping with negative emotions and perceptions arising from employment stress, thus leading to ego depletion. On the other hand, ego depletion among recent graduates was significantly and positively related to suicidal ideation. According to the limited resource model, when an individual experiences ego depletion, it becomes challenging for them to effectively manage their reactions, resulting in potentially problematic behaviors (11). If recent graduates have a low level of ego depletion, they are more likely to take the initiative to regulate their emotions and thinking and use positive strategies to cope with employment pressure so that they can quickly reduce negative emotions and thinking, thus reducing the likelihood of suicidal ideation. Studies indicate that individuals experiencing higher levels of ego depletion often resort to employing more negative coping strategies (26). Since recent graduates who adopt negative emotional coping strategies pay more attention to emotions themselves, such coping strategies not only help people solve problems but also amplify the intensity of stress caused by existing employment pressure, triggering negative emotions such as anxiety and depression, potentially leading to suicidal thoughts.

Moderating role of negotiable fate

The results showed that the impact of employment pressure on ego depletion and suicidal ideation among recent graduates was moderated by negotiable fate. In other words, a strong belief in negotiable fate alleviated the negative impact of employment pressure. From the perspective of negotiable fate, negotiable fate is a positive personality trait (27). Individuals with a strong belief in negotiable fate are more optimistic and adopt positive coping strategies in the face of setbacks and difficulties, facilitating the achievement of their life goals (17). Therefore, recent graduates with a strong belief in negotiable fate were better able to cope with employment pressure and pro-actively adapt to the COVID-19 pandemic environment, thus reducing negative emotional experiences. In addition, negotiable fate helps to enhance individuals’ sense of meaning in life, future expectations, subjective well-being, optimism, etc. (28); the greater the level of these psychological resources, the more individuals can cope with various negative events (29). Therefore, the negative impact of employment pressure is mitigated by the fact that recent graduates with a strong belief in negotiable fate have more internal psychological resources. In conclusion, during the COVID-19 pandemic, recent graduates with a strong belief in negotiable fate were better able to adapt to the current environment and had greater access to supportive resources. As a result, the effects of employment pressure on suicidal ideation and ego depletion were attenuated.

Implications for practice

This study reveals the effects and mechanisms of employment pressure on the suicidal ideation of college graduates and provides empirical references for the prevention and intervention of suicidal ideation in college graduates. Based on the results of the study, the following recommendations are made: first, employment pressure on recent graduates should be reduced by treating the source. A multipronged support system has been constructed at the social, school and other levels to reduce employment pressure on university graduates. For example, schools should strengthen employment assistance during epidemics, such as organizing career planning contests, conducting job search simulation interviews, and providing employment information. In addition, ego depletion plays a mediating role in the relationship between employment pressure and suicidal ideation. Therefore, it is also important to regularize psychological counseling for employment in the context of epidemics and to help individuals acquire positive emotion regulation strategies through regular psychological counseling seminars and online counseling. In this way, university graduates will have access to a wealth of psychological resources to minimize their ego depletion even when they encounter employment setbacks during epidemics. Finally, negotiable fate buffers the negative effects of employment pressure on ego depletion and suicidal ideation. This also suggests that we should shape the negotiable destiny of college graduates. In employment support programs for college graduates, we can use positive beliefs in traditional Chinese culture, such as “man proposes and God disposes”, to encourage students to take initiative, to positively cope with adversity and frustration.

Limitations and future directions

This study has several shortcomings. First, all the data measurements in this study were based on the perspectives of recent graduates and were somewhat subjective. Subsequent research could gather information from classmates, teachers, and parents to supplement the constraints associated with self-reported data. Additionally, as this study utilized data from only two time points, a comprehensive and systematic understanding of the dynamic relationships among the variables was limited. Hence, it is imperative to further investigate the trends and interactions among these variables across multiple time points (at least three). Additionally, considering the enduring and momentary impacts of ego depletion (30), this study focused solely on its enduring effects. Future investigations should explore both the enduring and momentary effects of ego depletion to yield a more comprehensive understanding of ego depletion. In the end, data were collected only from recent graduates in four provinces; in particular, data on recent graduates from other regions were not included, which may make it difficult to represent university graduates nationwide. Future studies should increase the sample size and collect data on a wider range of university graduates for exploration.

Conclusion

The study indicated three critical results: 1) a significant positive relationship between employment pressure and suicidal ideation among recent graduates, 2) ego depletion acting as a partial mediator between employment pressure and suicidal ideation among recent graduates, and 3) negotiable fate moderating the associations between employment pressure and both suicidal ideation and ego depletion. Further analysis using simple slope analysis revealed that these effects (employment pressure → suicidal ideation; employment pressure → ego depletion) were less pronounced among recent graduates with a strong belief in negotiable fate.

Journalism Ethics considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Education Science “Thirteenth Five-Year Plan” Key Project of the Ministry of Education (No. DBA190307).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- 1.Yang BL, Fang T, Huang J. (2023). SES, Relative Deprivation, Perceived Kindergarten Support and Turnover Intention in Chinese Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Moderated Mediation Model. Early Educ Dev, 34(2): 408–425. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet, (395): 912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devylder J, Zhou S, Oh H. (2021). Suicide attempts among college students hospitalized for COVID-19. J Affect Disord, 294(2): 241–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang S W, Liu LL, Peng XD, et al. (2022). Prevalence and associated factors of suicidal ideation among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: A 3-wave repeated survey. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1): 336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Z, Wang D, Zhao J, et al. (2022). Longitudinal associations between multiple mental health problems and suicidal ideation among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord, 311: 425–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JS, Lee SK. (2020). The effects of laughter therapy for the relief of employment-stress in korean student nurses by assessing psychological stress salivary cortisol and subjective happiness. Osong Public Health Res Perspect, 11(1): 44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng Y, Lv SB, Low SR, et al. (2023). The impact of employment stress on college students: Psychological well-being during COVID-19 pandemic in China. Curr Psychol, 1–12. (2024) 10.1007/s12144-023-04785-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Y, Zhang J, Liu Y. (2022). The impact of enterprise management elements on college students’ entrepreneurial behavior by complex adaptive system theory. Front Psychol, 12: 769481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin L. (2022). From employment pressure to entrepreneurial motivation: An empirical analysis of college students in 14 universities in China. Front Psychol, 13: 924302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rozanov V. (2020). Mental health problems and suicide in the younger generation — implications for prevention in the Navy and merchant fleet. Int Marit Health, 71(1): 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuk MA, Zhang KJ, Sweldens S. (2015). The propagation of self-control: Self-control in one domain simultaneously improves self-control in other domains. J Exp Psychol Gen, 144 (3): 639–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin X, Lin S, Zhang H, et al. (2023). Longitudinal association between cumulative work risks and suicidal ideation among Chinese employees during the COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated mediation model. Curr Psychol. 10.1007/s12144-023-04848-y [DOI]

- 13.Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Tice DM. (2007). The strength model of self–control. Curr Dir Psychol Sci, 16 (6): 351–355. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang S, Yang J, Yue L, et al. (2022). Impact of perception reduction of employment opportunities on employment pressure of college students under COVID-19 epidemic–joint moderating effects of employment policy support and job–searching self–efficacy. Front Psychol, 13: 986070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hobfoll SE. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested–self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl Psychol, 50(3): 337–421. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Au E, Qin X, Zhang ZX. (2017). Beyond personal control: When and how executives’ beliefs in negotiable fate foster entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process, 143: 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaturvedi A, Chiu CY, Viswanathan M. (2009). Literacy, negotiable fate, and thinking style among low income women in India. J Cross Cult Psychol, 40(5): 880–893. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Z. (2010). Study on the Relationship of Job-hunting stress, Career decision-making self-efficacy and Vocational selection anxiety of College students (Harbin Engineering University, Master Thesis).

- 19.Nes LS, Ehlers SL, Whipple MO, et al. (2013). Self-regulatory fatigue in chronic multisymptom illnesses: Scale development, fatigue, and self-control. J Pain Res, 6: 181–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Zhang J, Wang J, et al. (2015). Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the self-regulatory fatigue scale in young adults. Chin Mental Health J, 29(4): 290–294. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang B, Bai B, Zhong N. (2017). Effect of negotiable fate on subjective well-being: The mediating role of meaning in life. Chin J Clin Psychol, 25(4): 724–730. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osman A, Gutierrez PM., Kopper BA, et al. (1998). The positive and negative suicide ideation inventory: Development and validation. Psychol Rep, 82(1): 783–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Gong H, Kang X. (2011). Reliability and validity of Chinese revision of positive and negative suicide ideation in high school students. China J Health Psychol, 19(8): 964–966. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu F, Shi JN, Shi Y. (2016). Research on relationship of undergraduates employment pressure, personality traits and career orientation. China J Health Psychol, 24(9): 1397–1401. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang Y, Lin X, Yang J, et al. (2023). Association between psychological capital and depressive symptoms during COVID-19: The mediating role of perceived social support and the moderating effect of employment pressure. Front Public Health, 11: 1036172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nigg JT. (2017). On the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 58(4): 361–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Au EWM., Chiu CY, Zhang ZX, et al. (2012). Negotiable fate: Social ecological foundation and psychological functions. J Cross Cult Psychol, 43(6): 931–942. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen M. Q. (2016). The relationship of negotiable fate and expect: The mediation of emotion and the moderation of societal practices for collectivism. J Fujian Norm University (Philos and Soc Sci Edition), 2: 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Au EWM, Chiu CY, Chaturvedi A. (2011). Maintaining faith in agency under immutable constraints: Cognitive consequences of believing in negotiable fate. Int J Psychol, 46 (6): 463–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barlett C, Oliphant H, Gregory W, et al. (2016). Ego-depletion and aggressive behavior. Aggress Behav, 42: 533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]