Abstract

Background

Influenza vaccination is free of charge for Danish citizens with acquired immunodeficiency but recommendations do not specifically target patients with cancer. This study investigated whether influenza vaccination reduces the main outcome of overall mortality and the secondary outcomes of influenza requiring treatment, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer.

Methods

This was a register‐based nationwide cohort study. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for overall mortality and secondary outcomes were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models. Analyses were conducted separately for four subgroups: patients aged <65 years with solid tumors, patients aged ≥65 years with solid tumors, patients aged <65 years with hematological cancer, and patients aged ≥65 years with hematological cancer.

Results

A total of 53,249 adult patients with solid tumors who received chemotherapy and 22,182 adult patients with hematological cancer were followed for up to five influenza seasons in the study period of 2007–2018. In the main analysis covering December–March, influenza vaccination was associated with reduced overall mortality in all four subgroups. The reduction was most pronounced in patients with hematological cancer aged <65 years (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.51–0.87) and smallest in patients with solid tumors aged <65 years (aHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.84–0.99). In sensitivity analyses covering January–March, the aHR was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.65–1.16) in patients with hematological cancer aged <65 years and 1.01 (95% CI, 0.92–1.10) in patients with solid tumors aged <65 years. Results for the secondary outcomes were inconclusive.

Conclusions

The results of this study cannot reject that influenza vaccination reduces overall mortality in immunocompromised patients with cancer. The results must be interpreted with caution because of potential unmeasured confounding, which can result in the overestimation of influenza vaccine effectiveness.

Keywords: chemotherapy, hematological cancer, immunosuppression, influenza vaccination, seasonal influenza, solid tumors

Short abstract

Influenza vaccination may reduce overall mortality in immunocompromised patients with cancer. The results must be interpreted with caution because of potential unmeasured confounding, which is likely to result in overestimating the effect of influenza vaccination.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza is a viral respiratory infection estimated to severely affect 3–5 million people each year 1 and to increase the rates of mortality, pneumonia, and cardiovascular events in the general population. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 Immunocompromised patients with cancer are particularly susceptible to influenza‐related hospitalization and mortality as a result of their impaired immune response and prolonged viral shedding. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Influenza vaccination is recommended for immunosuppressed individuals in most European countries. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19

Still, there is limited research on how effective the influenza vaccine is in preventing overall mortality and other clinical outcomes in immunocompromised patients with cancer. A systematic review of influenza vaccine effectiveness in immunocompromised patients with cancer identified two observational studies suggesting that influenza vaccination reduced overall mortality and one randomized trial that showed no reduction. 13 Results on confirmed influenza, influenza‐like illness, and pneumonia were inconclusive. Because of limited evidence, the authors recommended well‐conducted observational studies including a variety of malignancies, a defined age group, many influenza seasons, and clinically important outcomes such as overall mortality, confirmed influenza, and pneumonia. 13 Recent studies showed mixed results for reduction in overall mortality 20 , 21 and laboratory‐confirmed influenza in patients with cancer 22 after influenza vaccination. Associations between influenza vaccination and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with cancer are largely unexplored but one study showed no reduction in heart disease–related emergency admission or hospitalization in patients with breast cancer. 21

We aimed to fill the knowledge gap, and investigated the hypothesis that influenza vaccination reduces the main outcome of overall mortality and the secondary outcomes of influenza requiring treatment, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This nationwide cohort study was conducted with information from multiple Danish national registries, which were linked via the unique personal identification number assigned to all Danish citizens at birth or upon immigration. 23

Setting

The Danish National Health Service is funded by taxes and guarantees free access to general practitioners, hospitals, and outpatient specialty clinics for all citizens. 23 Since 2002, the influenza vaccine has been free of charge for Danish citizens aged ≥65 years. Since 2007, the Danish guidelines for free‐of‐charge influenza vaccination have gradually been expanded to include further risk groups (Table S1). From 2007 onward, persons regardless of age with congenital or acquired immunodeficiency have been eligible for free‐of‐charge influenza vaccination with the inactivated vaccine. 24 , 25 Although the recommendations do not specifically target patients with cancer, individuals with hematological cancer and those undergoing immunosuppressive treatments should be part of the recommendations.

Study population and follow‐up

The study design is graphically depicted in Figure S1. 26 We identified all Danish citizens with a recording of an incident cancer diagnosis from October 1, 2002, to October 1, 2017, in the Danish Cancer Registry. 27 Diagnoses of noninvasive, benign, or precancerous conditions were disregarded (Appendix A2). We included patients aged ≥18 years at the date of diagnosis of 23 prespecified cancers (Appendix A1). The overall study period was from the introduction of the free‐of‐charge influenza vaccine for individuals with acquired immunodeficiency in 2007/2008 until 2017/2018. For each season, eligibility criteria for inclusion were conditioned by (1) a date of diagnosis on or before October 1, which aligned with the beginning of the period during which influenza vaccination is offered free of charge to immunocompromised patients with cancer, and (2) being alive and at risk at the start of follow‐up on December 1, which defined the beginning of the influenza season. All individuals who met the eligibility criteria were followed from December 1 to March 31 in each influenza season after the incident cancer diagnosis or until the occurrence of an event, a new primary cancer, emigration, end of follow‐up (5 years after the incident cancer diagnosis), or end of the study period (March 31, 2018), whichever came first. Patients with hematological cancer were included in all seasons, whereas patients with solid tumors were only included in seasons with at least one chemotherapy treatment from July 1 until November 30.

Ethical approval

According to Danish legislation, informed consent and ethical approval are not required for registry‐based studies. This study was registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency at Aarhus University (record number 2016‐051‐000001‐1617).

Influenza vaccination assessment

We obtained information on the date of influenza vaccination from three Danish registries. Free‐of‐charge influenza vaccination performed under the authority of a general practitioner is registered in the Danish National Health Service Register (for reimbursement purposes). 28 Information on influenza vaccination during hospitalization was obtained from the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR). 29 Vaccines redeemed at Danish pharmacies were obtained from the Danish National Prescription Registry (DNPrR) (vaccine codes are available in Appendix A3). 30

Outcome assessment

Overall mortality was defined by the date of death from the Danish Civil Registration System (DCRS). 31 Influenza requiring treatment was defined on the basis of influenza diagnosis in the DNPR or a prescription of oseltamivir in the DNPrR. Incident diagnoses of pneumonia, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and venous thromboembolism were obtained from the DNPR (outcome codes are available in Appendix A4).

Covariate assessment

Confounders were assessed a priori in the existing literature, which included a study by our research group, 32 and were verified with directed acyclic graphs (for overall mortality, see Figure S2). Identified confounders included age, sex (male or female), place of birth (Danish or foreign born), and cohabitation (couple or single) from the DCRS. 31 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 The highest reached education (low, medium, or high) was accessed from the Danish Education Registers. 41 , 42 Information on cancer stage at diagnosis (for patients with solid tumors only: local, regional, distant, or unknown) was accessed from the Danish Cancer Registry. 27 Chemotherapy receipt (for patients with hematological cancer only: “chemotherapy” or “no chemotherapy” from July 1 until November 30 from the DNPR; Appendix A5). 29 , 43 Influenza vaccination eligibility, not including age, cancer type, or cancer treatment, included a diagnosis of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver failure, chronic lung diseases, immunodeficiency, and obesity from the DNPR, medication for diabetes from the DNPrR, or a health‐related pension from the income registries (Appendix A6). 33 , 34 , 35 , 40 , 44 Information on previous influenza vaccination (“vaccinated previous season” or “not vaccinated previous season”) was based on the same sources as used for exposure assessment. 35

Statistical methods

Analyses were conducted separately for each of the four subgroups on the basis of age and cancer type. These subgroups included patients aged <65 years with solid tumors, patients aged ≥65 years with solid tumors, patients aged <65 years with hematological cancer, and patients aged ≥65 years with hematological cancer. Distributions of patient characteristics at the beginning of each influenza season under observation were tabulated by influenza vaccination status at the end of each influenza vaccination season. The duration of the vaccination season varied according to vaccination guidelines, and included October–December in the seasons 2007/2008–2013/2014 and October–February in 2014/2015–2017/2018 (Table S1). For all influenza seasons combined, we computed adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) of all outcomes and associated 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) with a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for the potential confounders in Table 1 and with clustering by patient ID to account for repeated observations. The underlying time was days measured from December 1 in each season. As of December 1, influenza vaccination status was based on vaccinations received in October and November, where after vaccination was included as a time‐varying exposure. Thus, patients who were vaccinated for influenza from December 1 changed exposure status to influenza vaccinated on the date of vaccination. The assumption of proportional hazards was evaluated graphically. 45

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 141,192 individual influenza seasons experienced by 75,431 patients with cancer by cancer type and age group.

| Patients with solid tumors on chemotherapy aged <65 years | Patients with solid tumors on chemotherapy aged ≥65 years | Patients with hematological cancer aged <65 years | Patients with hematological cancer aged ≥65 years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated | Unvaccinated | Vaccinated | Unvaccinated | Vaccinated | Unvaccinated | Vaccinated | Unvaccinated | |

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Total | 8328 (23) | 27,283 (77) | 15,531 (48) | 17,053 (52) | 7489 (24) | 24,357 (76) | 22,908 (56) | 18,243 (44) |

| Age, years | ||||||||

| <45 | 742 (9) | 4493 (16) | NA | NA | 903 (12) | 6631 (27) | NA | NA |

| 45–54 | 2155 (26) | 8862 (32) | NA | NA | 1680 (22) | 6410 (26) | NA | NA |

| 55–59 | 2122 (25) | 6484 (24) | NA | NA | 1789 (24) | 4795 (20) | NA | NA |

| 60–64 | 3309 (40) | 7444 (27) | NA | NA | 3117 (42) | 6521 (27) | NA | NA |

| 65–69 | NA | NA | 5358 (34) | 7242 (42) | NA | NA | 5720 (25) | 5967 (33) |

| 70–74 | NA | NA | 5255 (34) | 5468 (32) | NA | NA | 6204 (27) | 5015 (27) |

| 75–79 | NA | NA | 3290 (21) | 3001 (18) | NA | NA | 4976 (22) | 3400 (19) |

| ≥80 | NA | NA | 1628 (10) | 1342 (8) | NA | NA | 6008 (26) | 3861 (21) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 2781 (33) | 8804 (32) | 7793 (50) | 8300 (49) | 4011 (54) | 14,732 (60) | 12,668 (55) | 10,203 (56) |

| Female | 5547 (67) | 18,479 (68) | 7738 (50) | 8753 (51) | 3478 (46) | 9625 (40) | 10,240 (45) | 8040 (44) |

| Place of birth | ||||||||

| Danish born | 7918 (95) | 25,367 (93) | 15,121 (97) | 16,430 (96) | 7037 (94) | 22,159 (91) | 22,251 (97) | 17,561 (96) |

| Foreign born | 410 (5) | 1916 (7) | 410 (3) | 623 (4) | 452 (6) | 2198 (9) | 657 (3) | 682 (4) |

| Highest reached education | ||||||||

| Low | 2382 (29) | 6857 (25) | 6095 (39) | 6961 (41) | 1837 (25) | 5875 (24) | 9241 (40) | 7898 (43) |

| Medium | 3554 (43) | 12,082 (44) | 6415 (41) | 6955 (41) | 3350 (45) | 10,902 (45) | 8813 (38) | 6901 (38) |

| High | 2392 (29) | 8344 (31) | 3021 (19) | 3137 (18) | 2302 (31) | 7580 (31) | 4854 (21) | 3444 (19) |

| Previous influenza vaccination | ||||||||

| Not vaccinated previous season | 5797 (70) | 26,321 (96) | 4793 (31) | 14,756 (87) | 3690 (49) | 22,482 (92) | 5007 (22) | 14,760 (81) |

| Vaccinated previous season | 2531 (30) | 962 (4) | 10,738 (69) | 2297 (13) | 3799 (51) | 1875 (8) | 17,901 (78) | 3483 (19) |

| Eligibility for free‐of‐charge influenza vaccination a | ||||||||

| Not eligible for free vaccination | 4006 (48) | 17,426 (64) | 6148 (40) | 8170 (48) | 3557 (47) | 16,164 (66) | 9136 (40) | 8371 (46) |

| Eligible for free vaccination | 4322 (52) | 9857 (36) | 9383 (60) | 8883 (52) | 3932 (53) | 8193 (34) | 13,772 (60) | 9872 (54) |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||||||

| Local | 1638 (20) | 6495 (24) | 1845 (12) | 1868 (11) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Regional | 3205 (38) | 11,054 (41) | 6116 (39) | 6752 (40) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Distant | 2727 (33) | 6869 (25) | 5722 (37) | 6246 (37) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Unknown | 758 (9) | 2865 (11) | 1848 (12) | 2187 (13) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||

| No | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6351 (85) | 20,289 (83) | 19,832 (87) | 14,790 (81) |

| Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1138 (15) | 4068 (17) | 3076 (13) | 3453 (19) |

Note: Data presented are the distribution of characteristics of observed influenza seasons by vaccination status, categorized into patients with solid tumors and patients with hematological cancer aged <65 and ≥65 years. Each patient could be included in several influenza seasons. NA indicates not available.

Eligibility criteria for free‐of‐charge influenza vaccination (regardless of age ≥65 years, cancer type, or chemotherapy) are the following: (1) a health‐related pension at any time point, (2) registration in the Danish National Patient Registry for diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, immunodeficiency, chronic kidney failure, chronic liver failure, or chronic lung diseases within 10 years before the start of the current influenza season, and (3) medication for diabetes or chronic lung diseases administered 2 years before the start of the current season (see Appendix A6 for codes).

To assess the robustness of our findings for the primary outcome, we performed a variety of sensitivity analyses in which we (1) restricted our analysis to influenza seasons with a match between the vaccine composition and circulating virus strain, and when the proportion of influenza‐like illness consultations was >0.75% as per a previous study to define the active influenza season (Appendix A7) 46 ; (2) restricted our analysis to patients with a recently (April–September) diagnosed local‐stage solid tumor; (3) assessed the associations outside the peak influenza months by extending the follow‐up period to 1 full year, divided into 1‐month periods, starting from December 1 until November 30 the following year; (4) restricted the full‐year analysis to patients with a recently (April–September) diagnosed local‐stage solid tumor; (5) examined modified periods of the influenza season, where the underlying time was days measured from January 1 in each modified season, which included January–March and January–April; (6) assessed the associations for men and women separately according to the influenza season and the modified periods; (7) assessed the associations for all patients combined and separately for patients aged <65 and ≥65 years (regardless of cancer type) according to the influenza season and the modified periods; and (8) performed the analysis for each cancer type separately. All analyses were performed with Stata 17.

RESULTS

We included 75,431 patients with an incident cancer diagnosis from October 1, 2002, to October 1, 2017 (Figure 1). We observed the patients for a total of 141,192 influenza seasons. The influenza vaccination coverage was higher in patients aged ≥65 years (56% in patients with hematological cancer; 48% in patients with solid tumors) than in patients aged <65 years (24% in patients with hematological cancer; 23% in patients with solid tumors) (Table 1). Among those vaccinated, there was a higher proportion of patients who were vaccinated in the previous season and who were eligible for the free‐of‐charge influenza vaccination for reasons other than age, cancer type, or cancer treatment. In patients aged <65 years, the vaccinated were older than the unvaccinated (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the study population selection. aDiagnosis codes are available in Appendix A1. bAge in the first observed influenza season for each patient.

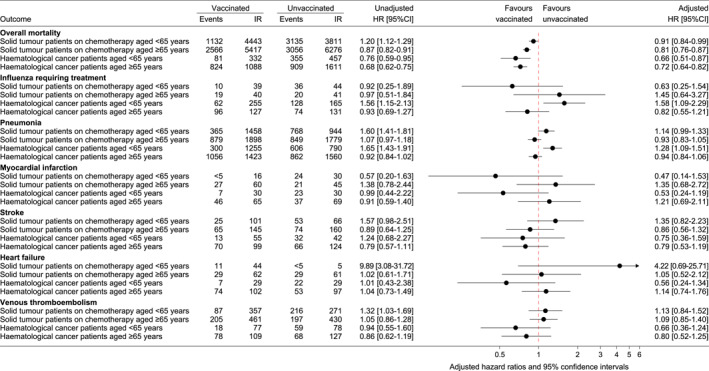

For overall mortality, the highest incidence rate was in unvaccinated patients with solid tumors aged ≥65 years (6274 events per 10,000 person‐years) and lowest in vaccinated patients with hematological cancer aged <65 years (332 events per 10,000 person‐years) (Figure 2). Influenza vaccination was associated with reduced overall mortality in all patients (Figure 2). The reduction was most pronounced in patients with hematological cancer aged <65 years (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.51–0.87) and less in patients with solid tumors aged <65 years (aHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.84–0.99) (Figure 2). For the secondary outcomes, there were a limited number of events (except for pneumonia), which resulted in uncertain estimates; we found estimates both below and above 1 for each outcome depending on patient group (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Number of events, incidence rates per 10,000 person‐years, and hazard ratios for the associations between influenza vaccination and outcomes during the influenza season (December–March) for all seasons combined (2007/2008–2017/2018). Incidence rates are shown as events per 10,000 person‐years. Hazard ratios from Cox proportional hazards models, with days measured from December 1 in each influenza season as the underlying time. The adjusted models include influenza vaccination in the previous season, criteria that qualify for free‐of‐charge influenza vaccination, education level, place of birth, age, and sex. Cancer stage at diagnosis was included in the adjusted analyses of patients with solid tumors, and receipt of chemotherapy was included in the adjusted analyses of patients with hematological cancer. CI indicates confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IR, incidence rate.

Sensitivity analyses

When restricting to the active influenza period (influenza‐like illness consultations, >0.75%) in seasons where the vaccine matched the virus, the associations between influenza vaccination and overall mortality were strengthened across all subgroups (Figure 3). When extending the follow‐up to 1 full year and reporting results for 1‐month periods, the aHR for overall mortality was lowest in December. In general, the associations weakened or disappeared from February onward. However, for patients with solid tumors and patients with hematological cancer aged <65 years, the vaccine increased overall mortality in some months outside the influenza season (Figure 4). In a subpopulation of 5430 newly diagnosed patients with local‐stage solid tumors, the aHR for overall mortality in December–March was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.50–1.54) in patients aged <65 years and 0.79 (95% CI, 0.52–1.22) in patients aged ≥65 years. When restricting the full‐year analysis to patients with a newly diagnosed local‐stage solid tumor, the protective effect of the vaccine on overall mortality was most pronounced in April in individuals aged <65 years (aHR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.06–1.05) and in February in those aged ≥65 years (aHR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.16–0.78) (Figure S3); however, the estimates were imprecise, and point estimates changed direction across the year. When using modified definitions of the periods of the influenza season (January–March and January–April), the point estimates moved closer to 1 compared with the main analysis (Figure 5). In the analysis of men and women separately, the aHR was lower in women compared with men in patients with solid tumors (Figure S4). Findings from the analyses of all patients with cancer combined and by age group indicated a reduction in overall mortality among those aged ≥65 years regardless of the influenza season period (Figure S5). When assessing overall mortality separately by the 23 prespecified cancers, the magnitude and direction of the associations varied on the basis of cancer type and age group (Figure S6).

FIGURE 3.

Sensitivity analysis of influenza seasons with a match between the influenza vaccine components and circulating influenza virus and only including follow‐up during the active influenza season defined as the proportion of influenza‐like illness consultations >0.75%. Hazard ratios from a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for influenza vaccination in the previous season, criteria that qualify for free‐of‐charge influenza vaccination, education level, place of birth, age, and sex. Cancer stage at diagnosis was included in the analysis of patients with solid tumors, and receipt of chemotherapy was included in the analysis of patients with hematological cancer. The underlying time is days measured from the date when the proportion of influenza‐like illness consultations first was >0.75%. Appendix A7 specifies the included seasons and time periods. CI indicates confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

FIGURE 4.

Associations between influenza vaccination and overall mortality across the year divided into 1‐month periods. Hazard ratios from a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for influenza vaccination in the previous season, comorbidities resulting in free‐of‐charge influenza vaccination, education level, place of birth, age, and sex. Furthermore, cancer stage was included in the analysis of patients with solid tumors, and chemotherapy was included in the analysis of patients with hematological cancer. CI indicates confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

FIGURE 5.

Adjusted hazard ratios for the associations between influenza vaccination and overall mortality observed in the modified periods of January–March and January–April for all seasons combined (2007/2008–2017/2018). Hazard ratios from a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for influenza vaccination in the previous season, criteria that qualify for free‐of‐charge influenza vaccination, education level, place of birth, age, and sex. Cancer stage at diagnosis was included in the analysis of patients with solid tumors, and receipt of chemotherapy was included in the analysis of patients with hematological cancer. The underlying time is days measured from January 1 in each influenza season. CI indicates confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

In this nationwide register‐based cohort study of 75,431 adult patients with cancer, influenza vaccination was associated with reduced rates of overall mortality during the influenza season but the results were sensitive to the definition of the influenza season duration. Results for the secondary outcomes, including influenza requiring treatment, pneumonia, and cardiovascular diseases, were inconclusive.

Strengths and limitations

As a result of the comprehensive long‐term follow‐up offered by the DCRS and the universal tax‐funded health care provided by the Danish health care system, selection bias was of limited concern in this study. Patients with no information on highest reached education, cohabitation, or place of birth from the current or previous season were excluded. Missing education data can occur if the education was obtained before entering the country or before the registries started recording information or if the education was achieved abroad and could not be translated to the Danish system. This may introduce nondifferential selection but the proportion of missing data was small and is unlikely to affect the results. 47

Misclassification bias

We have likely underestimated the proportion of those vaccinated for influenza in the study population. Influenza vaccination codes in the Danish registries have not been validated but the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine is underreported because of administrative errors related to reimbursement. 48 Similar errors are expected for the influenza vaccine but this is unlikely to be related to the outcomes. Underestimation may also occur because of, for example, nonreimbursed workplace influenza vaccinations, which are not covered by the national health insurance. This could introduce differential misclassification of exposure because patients with less severe cancers may have a higher likelihood of employment, and thus a greater risk of being misclassified as unvaccinated, while simultaneously having a lower risk of dying. This would lead to bias toward the null but would be most prominent in patients with cancer aged <65 years because of labor market attachment.

Overall mortality recording in the DCRS is expected to be high because of the comprehensive nature of the registry. 31 Influenza diagnosis codes in the DNPR and prescriptions of oseltamivir in the DNPrR have not been validated. In general, influenza cases will be underreported because only the most severe cases will require treatment. Regarding influenza requiring treatment, differential misclassification could occur if the inclination to seek medical attention or testing for influenza is reduced among those who are vaccinated. This would lead to bias away from the null. Positive predictive values (PPVs) have been estimated for diagnoses of pneumonia (PPV, 93%; 95% CI, 85%–96%), 49 myocardial infarction (PPV, 97%; 95% CI, 91%–99%), stroke (PPV, 79%; 95% CI, 62%–88%), heart failure (PPV, 76%; 95% CI, 66%–83%), and venous thromboembolism (PPV, 88%; 95% CI, 80%–93%) registered in the DNPR. 50 , 51

Confounding bias

Unmeasured confounding may have biased our results, especially in the analysis of overall mortality. Terminally ill patients with cancer with a high risk of death may have a lower likelihood of vaccination if the perceived benefit is low as a result of the short expected lifetime. This would lead to a higher mortality rate among the unvaccinated, which would result in an overestimation of the vaccine's effectiveness.

When dividing the full‐year analysis into 1‐month periods, our findings showed reduced overall mortality for vaccinated patients in December and for some groups also in January, whereas no considerable effect was observed in February and March. A plausible explanation could be that a substantial proportion of those who were unvaccinated because of terminal illness would die at the beginning of the influenza season (December and January), whereas the unvaccinated thereafter might be more comparable to vaccinated patients, and therefore result in an estimate closer to the null. In sensitivity analyses excluding December from the influenza season, the associations weakened or disappeared compared with the main analysis. To reduce bias introduced by the incomparability of prognosis between the exposure groups, we restricted both the main analysis and the full‐year analysis to include patients with a newly diagnosed local‐stage solid tumor, which assumed that these patients would not be terminally ill. Because of the low number of included patients in these analyses, the estimates were imprecise. For December–March, the effect in the newly diagnosed was similar to that observed in the main analysis. In the full‐year analysis of newly diagnosed patients, point estimates changed direction both inside and outside the influenza season, and no clear trends were observed throughout the year in this subpopulation.

Comparison with other studies

Observational studies have shown reduced overall mortality after influenza vaccination in various cancer populations, including 1225 elderly US patients treated for stage IV colorectal cancer (aHR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.77–0.99), 34 21,462 Danish patients with solid tumors undergoing curative surgery (aHR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.81–0.99), 20 and 806 adult Israeli patients with hematological cancer and patients with solid tumors receiving chemotherapy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.42; 95% CI, 0.24–0.75). 52 Two of these studies included December in the analysis of overall mortality, 34 , 52 and one study followed patients from 180 days after surgery and did not specify a specific period. 20 Authors of these studies also discussed unmeasured confounding bias in terms of underlying factors related to vaccination and risk of mortality. A Cochrane systematic review, 13 including a randomized trial of 78 patients with cancer, reported that influenza vaccination before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation compared with nonvaccination did not reduce overall mortality (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.43–3.62). 53 Furthermore, in an observational study of 5973 elderly newly diagnosed patients with breast cancer from Taiwan, influenza vaccination did not reduce overall mortality (aOR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.90–2.16). 21 This observational study did not include December in the analysis.

Our findings showed no reduction in influenza requiring treatment, pneumonia, and cardiovascular end points; neither did other observational and experimental studies of influenza‐like illness or confirmed influenza‐, 34 , 52 , 53 pneumonia‐, 21 , 52 , 54 and heart disease–related hospitalization. 21 Other studies were able to show a reduction. In an observational study of 43 recipients of bone marrow transfusion, primarily patients with cancer, who met the criteria for vaccination, vaccine effectiveness against influenza was 80%. 55 In a randomized trial of 50 patients with multiple myeloma, lower rates of influenza‐like illness were observed in the vaccinated group (OR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.05–0.61). 54 An observational study of 26,463 patients with solid tumors or hematological cancer observed a vaccine effectiveness against laboratory‐confirmed influenza hospitalization of 20% (95% CI, 13%–26%) with the test‐negative study design. 22 An observational study of 1225 adult patients with advanced colorectal cancer undergoing treatment showed, according to a Cochrane review, 13 that influenza vaccination reduced pneumonia (seven events in 626 person‐years among the vaccinated; 33 events in 951 person‐years among the unvaccinated). 34

Interpretation and implications

Our main analysis showed a 9%–34% reduction in overall mortality rates after influenza vaccination. According to a study, influenza is estimated to account for a maximum of 10% of all deaths among the elderly during the influenza season. 56 Thus, even at 100% effectiveness against influenza‐related deaths, the vaccine would only prevent 10% of overall deaths. 56 Whether the vaccine has the potential to assert a stronger effect in immunocompromised individuals is debatable. On one hand, the vaccine may be more effective in immunocompromised patients because of their increased vulnerability to severe complications from influenza. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 On the other hand, effective immunization may depend on an intact immune system in the vaccinated individual to produce antibodies in response to antigen exposure. A reduced immune response to vaccination is particularly expected in subgroups of patients with hematological cancer and patients with B‐cell cancers receiving treatment with anti‐CD20 antibodies 57 , 58 but is also suspected in patients undergoing chemotherapy. 59 , 60

Bias may have partially accounted for our main findings on reduced overall mortality during the influenza season. The analyses showed that the reduction mainly appeared in December. When omitting December in the modified influenza season periods, the associations weakened or disappeared. Still, some results from additional analyses could suggest a potential vaccine effect. During active seasons with a match between the vaccine and the virus, we showed that the associations were strengthened compared with the main analysis. This could indicate a potential benefit of the vaccine during seasons with increased protection. However, this must be interpreted with caution because defining the occurrence of a match may be more complex than a binary categorization, and we did not account for partial matches. Although a potential protective effect of the influenza vaccine on overall mortality appears to be present, we cannot quantify the exact effect size. Notably, the observed reduction in overall mortality was without a concurrent reduction in influenza requiring treatment. A potential explanation could be that the reduction in overall mortality after influenza vaccination is a result of the vaccine's effectiveness in protecting against the most severe cases of influenza that could lead to mortality. Additionally, we are aware that influenza rarely leads to diagnosis. Another study observed a protective effect of the influenza vaccine on confirmed influenza in a study where all patients underwent influenza testing. 22 In terms of generalizability, patients with cancer in other countries may have different characteristics in terms of health care systems, genetics, and health and lifestyle factors. Still, our results, if valid, may generalize to other countries with free‐of‐charge influenza vaccination for patients with cancer with impaired immune systems induced by either the cancer itself or the treatment.

In conclusion, we found that influenza vaccination was associated with reduced overall mortality in immunocompromised patients with cancer. However, our sensitivity analyses indicated that our study is prone to overestimating influenza vaccine effectiveness, as in other observational studies. Randomized trials may be needed to assess this important question further. Results for influenza, pneumonia, and cardiovascular end points were inconclusive.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lau Amdisen: Conceptualization; methodology; software; validation; formal analysis; investigation; resources; data curation; writing–original draft; writing–review and editing; visualization; project administration; and funding acquisition. Lars Pedersen: Conceptualization; methodology; software; validation; formal analysis; writing–review and editing; and supervision. Niels Abildgaard: Conceptualization; writing–review and editing; and supervision. Christine Stabell Benn: Conceptualization; writing–review and editing; and supervision. Deirdre Cronin‐Fenton: Conceptualization; investigation; writing–review and editing; project administration; funding acquisition; and supervision. Signe Sørup: Conceptualization; methodology; software; validation; formal analysis; investigation; resources; writing–review and editing; visualization; supervision; project administration; and funding acquisition.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Employment of Lau Amdisen is supported by a grant to Signe Sørup from the Danish Cancer Society (R231‐A13671). Lau Amdisen received support from the Danish Cancer Research Foundation (FID2014816). The funding sources were not part of the design and conduct of the study, analyses, or interpretation of the data.

Amdisen L, Pedersen L, Abildgaard N, Benn CS, Cronin‐Fenton D, Sørup S. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in immunocompromised patients with cancer: a Danish nationwide register‐based cohort study. Cancer. 2025;e35574. doi: 10.1002/cncr.35574

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data presented in this study were obtained from Danish registries. Because of data protection rules, sharing individual‐level data is not allowed. Data are available for other researchers who fulfill the requirements set by the data providers.

REFERENCES

- 1. Influenza (Seasonal). World Health Organization . Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/influenza‐(seasonal)

- 2. Hansen CL, Chaves SS, Demont C, Viboud C. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the US, 1999–2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220527. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cavallazzi R, Ramirez JA. Influenza and viral pneumonia. Clin Chest Med. 2018;39(4):703‐721. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Musher DM, Abers MS, Corrales‐Medina VF. Acute infection and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(2):171‐176. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1808137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Warren‐Gash C, Blackburn R, Whitaker H, McMenamin J, Hayward AC. Laboratory‐confirmed respiratory infections as triggers for acute myocardial infarction and stroke: a self‐controlled case series analysis of national linked datasets from Scotland. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(3):1701794. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01794-2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warren‐Gash C, Smeeth L, Hayward AC. Influenza as a trigger for acute myocardial infarction or death from cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(10):601‐610. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(09)70233-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sin P, Siddiqui M, Wozniak R, et al. Heart failure after laboratory confirmed influenza infection (FLU‐HF). Glob Heart. 2022;17(1):43. doi: 10.5334/gh.1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rubino R, Imburgia C, Bonura S, Trizzino M, Iaria C, Cascio A. Thromboembolic events in patients with influenza: a scoping review. Viruses. 2022;14(12):2817. doi: 10.3390/v14122817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boehme AK, Luna J, Kulick ER, Kamel H, Elkind MSV. Influenza‐like illness as a trigger for ischemic stroke. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5(4):456‐463. doi: 10.1002/acn3.545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cooksley CD, Avritscher EB, Bekele BN, Rolston KV, Geraci JM, Elting LS. Epidemiology and outcomes of serious influenza‐related infections in the cancer population. Cancer. 2005;104(3):618‐628. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carreira H, Strongman H, Peppa M, et al. Prevalence of COVID‐19‐related risk factors and risk of severe influenza outcomes in cancer survivors: a matched cohort study using linked English electronic health records data. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29‐30:100656. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yousuf HM, Englund J, Couch R, et al. Influenza among hospitalized adults with leukemia. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(6):1095‐1099. doi: 10.1086/513648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bitterman R, Eliakim‐Raz N, Vinograd I, Zalmanovici Trestioreanu A, Leibovici L, Paul M. Influenza vaccines in immunosuppressed adults with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD008983. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008983.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Memoli MJ, Athota R, Reed S, et al. The natural history of influenza infection in the severely immunocompromised vs nonimmunocompromised hosts. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(2):214‐224. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li J, Zhang D, Sun Z, Bai C, Zhao L. Influenza in hospitalised patients with malignancy: a propensity score matching analysis. ESMO Open. 2020;5(5):e000968. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glezen WP. Prevention and treatment of seasonal influenza. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(24):2579‐2585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0807498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2020–21 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69(8):1‐24. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6908a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hak E, Nordin J, Wei F, et al. Influence of high‐risk medical conditions on the effectiveness of influenza vaccination among elderly members of 3 large managed‐care organizations. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(4):370‐377. doi: 10.1086/341403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seasonal Influenza Vaccination and Antiviral Use in Europe—Overview of Vaccination Recommendations and Coverage Rates in the EU Member States for the 2013–14 and 2014–15 Influenza Seasons. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/Seasonal‐influenza‐vaccination‐antiviral‐use‐europe.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gögenur M, Fransgård T, Krause TG, Thygesen LC, Gögenur I. Association of postoperative influenza vaccine on overall mortality in patients undergoing curative surgery for solid tumors. Int J Cancer. 2021;148(8):1821‐1827. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu SY, Tung HJ, Huang KH, Lee CB, Tsai TH, Chang YC. The protective effects of influenza vaccination in elderly patients with breast cancer in Taiwan: a real‐world evidence‐based study. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(7):1144. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10071144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blanchette PS, Chung H, Pritchard KI, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness among patients with cancer: a population‐based study using health administrative and laboratory testing data from Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(30):2795‐2804. doi: 10.1200/jco.19.00354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Adelborg K, et al. The Danish health care system and epidemiological research: from health care contacts to database records. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:563‐591. doi: 10.2147/clep.S179083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bekendtgørelse om gratis influenzavaccination til visse persongrupper. The Danish Ministry of Health. Accessed June 27, 2024. https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2021/2074 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Statens Serum Institut . Influenza Vaccination 2007/2008. EPI‐NEWS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schneeweiss S, Rassen JA, Brown JS, et al. Graphical depiction of longitudinal study designs in health care databases. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(6):398‐406. doi: 10.7326/m18-3079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gjerstorff ML. The Danish Cancer Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(suppl 7):42‐45. doi: 10.1177/1403494810393562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andersen JS, Olivarius NDF, Krasnik A. The Danish National Health Service Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(suppl 7):34‐37. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449‐490. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kildemoes HW, Sorensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(suppl 7):38‐41. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(suppl 7):22‐25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Amdisen L, Pedersen L, Abildgaard N, et al. The coverage of influenza vaccination and predictors of influenza non‐vaccination in Danish cancer patients: a nationwide register‐based cohort study. Vaccine. 2024;42(7):1690‐1697. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Portero de la Cruz S, Cebrino J. Trends, coverage and influencing determinants of influenza vaccination in the elderly: a population‐based national survey in Spain (2006–2017). Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8(2):327. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Earle CC. Influenza vaccination in elderly patients with advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(6):1161‐1166. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vinograd I, Baslo R, Eliakim‐Raz N, et al. Factors associated with influenza vaccination among adult cancer patients: a case‐control study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(9):899‐905. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stafford KA, Sorkin JD, Steinberger EK. Influenza vaccination among cancer survivors: disparities in prevalence between Blacks and Whites. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(2):183‐190. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0257-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim YS, Lee JW, Kang HT, You HS. Trends in influenza vaccination coverage rates among Korean cancer survivors: analysis of the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III–VI. Korean J Fam Med. 2020;41(1):45‐52. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.18.0165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oh MG, Han MA, Yun NR, et al. A population‐based, nationwide cross‐sectional study on influenza vaccination status among cancer survivors in Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(8):10133‐10149. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120810133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Poeppl W, Lagler H, Raderer M, et al. Influenza vaccination perception and coverage among patients with malignant disease. Vaccine. 2015;33(14):1682‐1687. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martinez‐Huedo MA, Lopez‐De‐Andrés A, Mora‐Zamorano E, et al. Decreasing influenza vaccine coverage among adults with high‐risk chronic diseases in Spain from 2014 to 2017. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(1):95‐99. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1646577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish Education Registers. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(suppl 7):91‐94. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee JE, Shin DW, Shin J, et al. A cross‐sectional study of factors associated with influenza vaccination in Korean cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2021;30(5):e13443. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wumkes ML, van der Velden AM, van der Velden AW, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage in patients treated with chemotherapy: current clinical practice. Neth J Med. 2013;71(9):472‐477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(suppl 7):103‐105. doi: 10.1177/1403494811405098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stensrud MJ, Hernán MA. Why test for proportional hazards? JAMA. 2020;323(14):1401‐1402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Christiansen CF, Thomsen RW, Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. Influenza vaccination and 1‐year risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, pneumonia, and mortality among intensive care unit survivors aged 65 years or older: a nationwide population‐based cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(7):957‐967. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05648-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dong Y, Peng CY. Principled missing data methods for researchers. Springerplus. 2013;2(1):222. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Holt N, Mygind A, Bro F. Danish MMR vaccination coverage is considerably higher than reported. Dan Med J. 2017;64(2):A5345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Holland‐Bill L, Xu H, Sørensen HT, et al. Positive predictive value of primary inpatient discharge diagnoses of infection among cancer patients in the Danish National Registry of Patients. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(8):593‐597.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wildenschild C, Mehnert F, Thomsen RW, et al. Registration of acute stroke: validity in the Danish Stroke Registry and the Danish National Registry of Patients. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:27‐36. doi: 10.2147/clep.S50449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sundbøll J, Adelborg K, Munch T, et al. Positive predictive value of cardiovascular diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry: a validation study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e012832. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vinograd I, Eliakim‐Raz N, Farbman L, et al. Clinical effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine among adult cancer patients. Cancer. 2013;119(22):4028‐4035. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ambati A, Boas LS, Ljungman P, et al. Evaluation of pretransplant influenza vaccination in hematopoietic SCT: a randomized prospective study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50(6):858‐864. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Musto P, Carotenuto M. Vaccination against influenza in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 1997;97(2):505‐506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Machado CM, Cardoso MR, da Rocha IF, Boas LSV, Dulley FL, Pannuti CS. The benefit of influenza vaccination after bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36(10):897‐900. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Simonsen L, Reichert TA, Viboud C, et al. Impact of influenza vaccination on seasonal mortality in the US elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(3):265‐272. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.3.265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vijenthira A, Gong I, Betschel SD, Cheung M, Hicks LK. Vaccine response following anti‐CD20 therapy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of 905 patients. Blood Adv. 2021;5(12):2624‐2643. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. See KC. Vaccination for the prevention of infection among immunocompromised patients: a concise review of recent systematic reviews. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(5):800. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ring A, Marx G, Steer C, Harper P. Influenza vaccination and chemotherapy: a shot in the dark? Support Care Cancer. 2002;10(6):462‐465. doi: 10.1007/s00520-001-0337-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Verma R, Foster RE, Horgan K, et al. Lymphocyte depletion and repopulation after chemotherapy for primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0669-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study were obtained from Danish registries. Because of data protection rules, sharing individual‐level data is not allowed. Data are available for other researchers who fulfill the requirements set by the data providers.