Abstract

Olmsted syndrome is characterized by symmetrically distributed, destructive, inflammatory palmoplantar keratoderma with periorificial keratotic plaques, most commonly due to gain-of-function mutations in the transient receptor potential vanilloid 3 (TRPV3) gene, which involves multiple pathological functions of the skin, such as hyperkeratosis, dermatitis, hair loss, itching, and pain. Recent studies suggest that mutations of TRPV3 located in different structural domains lead to cases of varying severity, suggesting a potential genotype-phenotype correlation resulting from TRPV3 gene mutations. This paper reviews the genetics and pathogenesis of Olmsted syndrome, as well as the potential management and treatment. This review will lay a foundation for further developing the individualized treatment for TRPV3-related Olmsted syndrome.

Keywords: Olmsted syndrome, TRPV3, hyperkeratosis, itch, mutation

Introduction

Olmsted syndrome (OS) is a rare hereditary dermatosis characterized by symmetrically distributed, destructive, inflammatory palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) with periorificial keratotic plaques. The PPK could be very mild, focal, non-mutilating to extremely severe, diffuse and mutilating (e.g., spontaneous amputation). Periorificial hyperkeratosis could be noted in perioral, perinasal, perianal areas, perineum, and ear meatus. Other documented features include hair and/or nail abnormality. It is also accompanied by varying degrees of pruritus, pain, and even erythermalgia (Duchatelet et al., 2014; Duchatelet and Hovnanian, 2015). While the actual number of cases may be underreported, the prevalence is estimated to be below 1 in 1,000,000. This disease affects both genders with male predisposition, which accounts for approximately 63% of reported OS patients (Duchatelet et al., 2014).

Histopathological analysis of skin samples reveals epidermal hyperplasia, orthohyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and inflammatory infiltration in the upper dermis (Duchatelet and Hovnanian, 2015). These findings are non-specific and provide limited guidance for diagnosis. In the absence of specific biological markers, molecular genetics is the most effective method for establishing a diagnosis, particularly when the clinical presentation is atypical (Duchatelet and Hovnanian, 2015).

The causative genes of OS include membrane-bound transcription factor peptidase, site 2 (MBTPS2) gene or p53 effector related to PMP-22 (PERP), and transient receptor potential vanilloid 3 (TRPV3). MBTPS2 encodes site-2 protease (S2P) that is an integral membrane protein crucial for regulating membrane-bound transcription factors (Caengprasath et al., 2021), while PERP is responsible for coding a vital component of desmosomes (Duchatelet et al., 2019). Although MBTPS2 for X-linked recessive OS and PERP for autosomal dominant OS have been reported, the most common etiology of OS is gain-of-function mutations in TRPV3 with different patterns of inheritance.

However, the mechanism by which TRPV3 causes OS remains unclear, and there needs to be more comprehensive summaries regarding the progress of potential therapeutic drugs. Previous reviews have elucidated the clinical manifestations and differential diagnosis of OS. This review summarizes the pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic advancements related to OS associated with TRPV3 mutations.

Methods

This review is based on literature search using PubMed. To identify all relevant literature related to OS and summarize reported cases, a computerized search of the PubMed database was performed, including all studies published before 1 November 2023, using the search terms “TRPV3” and “Olmsted syndrome.”

Characteristics of TRPV3 channel

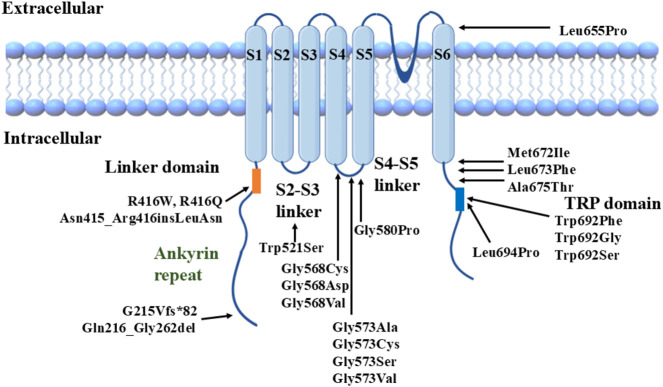

The TRPV3 channel is a symmetrical homotetramer, with each subunit consisting of an intracellular amino-terminal, carboxyl-terminal, linker region, and six transmembrane helices (S1-S6). The carboxyl-terminal contains a highly conserved transient receptor potential (TRP) domain (Zhong et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2018).

TRPV3 is expressed in various human tissues, including the skin, brain, spinal cord, dorsal root ganglia (DRG), and testes (Xu et al., 2002). In the skin, TRPV3 is highly expressed in the keratinocytes of the stratum basale and outer root sheath (ORS) of hair follicles (Peier et al., 2002; Park et al., 2017; Moqrich et al., 2005; Borbiro et al., 2011; Asakawa et al., 2006). The TRPV3 channel is activated at innocuous temperatures, ranging from 31°C–39°C, and it remains active within a noxious temperature range (Liu et al., 2011). Chemical activators for the TRPV3 channel include spice extracts (such as camphor, carvacrol, thymol, and eugenol), synthetic agents (including 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, i.e., 2-APB), and endogenous ligand farnesyl pyrophosphate (FFP) (Xu et al., 2002; Peier et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2006; Vogt-Eisele et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2002; Luo and Hu, 2014; Bang et al., 2010). Repeated exposure to heat or chemical stimuli leads to receptor sensitization through gating hysteresis (Moqrich et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2011; Xiao et al., 2008), and the combined application of various stimuli acts synergistically (Moqrich et al., 2005; Grubisha et al., 2014). Conversely, factors like adenosine triphosphate (ATP), Mg2+, and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) can inhibit TRPV3 sensitivity (Kim et al., 2013; Grandl et al., 2010; Chung et al., 2005). Studies in mouse and human keratinocyte cell lines show that TRPV3 activation induces whole-cell currents, intracellular calcium increases, or nitric oxide production, and release of inflammatory mediators like interleukin-1α (IL-1α) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (Moqrich et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2006; Yuspa et al., 1983; Miyamoto et al., 2011; Luo et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2006; Chung et al., 2004a; Chung et al., 2004b; Cheng et al., 2010; Cao et al., 2012).

Abundant evidence suggests that TRPV3 is involved in the natural development of hair. In mice, knockout of the TRPV3 gene results in irregular hair (bent and curled) and follicular keratosis, indicating that TRPV3 is responsible for maintaining normal hair morphology (Moqrich et al., 2005; Song et al., 2021). Numerous studies have shown that TRPV3 can significantly promote cell proliferation. Aijima et al. (2015) found that TRPV3 activation induces oral epithelial proliferation, promoting wound healing. Further researches revealed that TRPV3 greatly enhances keratinocyte proliferation through an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-dependent signaling pathway (Wang et al., 2021; He et al., 2015). Additionally, it has been found that TRPV3 is involved in maintaining skin barrier function and vascular formation (Cheng et al., 2010).

Aetiology

Genetics

The total number of OS cases is 100 (Duchatelet and Hovnanian, 2015; Zhong et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2021; Chiu et al., 2020). This paper mainly focuses on TRPV3 mutation-related OS, over 40 cases of OS with TRPV3 mutations are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Though most reported cases are sporadic, familial cases with different genetic patterns (autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked inheritance) have also been documented. At least 22 TRPV3 mutations have been identified in OS patients (Zhong et al., 2021) (Figure 1). These mutations are located in different structural domains and can lead to OS cases of varying severity, suggesting a potential genotype-phenotype correlation resulting from TRPV3 gene mutations (Chiu et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2015; Ni et al., 2016; Noakes, 2021). For instance, patients carrying p.Gly573Cys or p.Trp692Gly heterozygous mutations exhibit more severe hyperkeratosis compared to OS patients carrying p.Gln580Pro or p.Met672Ile heterozygous mutations. In vitro studies have shown that all four mutations mentioned above can reduce the activity of HaCaT cells and induce apoptosis, with significantly enhanced cytotoxicity observed for p.Gly573Cys and p.Trp692Gly compared to p.Gln580Pro and p.Met672Ile (Ni et al., 2016).

FIGURE 1.

Structural model of TRPV3 channel with reported mutations.

We previously found a correlation between TRPV3 genotype and OS phenotype, i.e., mutations located in the S4-S5 linker region and the TRP domain of TRPV3 significantly enhance channel function and lead to severe phenotypes. In contrast, the other mutations have a milder effect on channel function and disease phenotype (Zhong et al., 2021). We selected three TRPV3 variants, p.Arg416Gln, p.Leu673Phe, and p.Gln692Ser, representing mild, moderate, and severe clinical phenotypes of OS (especially the degree of keratinization), respectively, for functional studies. In vitro cytotoxicity experiments showed that mutant p.Trp692Ser was the most cytotoxic, p.Arg416Gln was the weakest, and p.Leu673Phe was intermediate. In vitro electrophysiological experiments also revealed that the increase in voltage sensitivity and the elevation of channel basal opening probability were most significant in p.Trp692Ser and not in p.Arg416Gln, whereas the electrophysiological properties of p.Leu673Phe were intermediate between p.Trp692Ser and p.Arg416Gln.

Pathogenesis

Hyperkeratosis

Even before the identification of the causative genes for OS, multiple studies (Raskin and Tu, 1997; Nofal et al., 2010; Kress et al., 1996) reported that in keratinocytes of OS, there is inadequate expression of mature epidermal proteins, persistent presence of basal layer keratins, and an increased expression of the proliferation marker Ki-67 in the basal layer and suprabasal layers (Tao et al., 2008; Requena et al., 2001; Elise Tonoli et al., 2012). Consequently, the involved region remains immature and continues to proliferate inappropriately. This excessive epithelial proliferation can lead to hyperkeratosis. In 2012, Lin et al. (2012) found that gain-of-function mutations in TRPV3 (p.Gly573Cys, p.Gly573Ser, and p.Trp692Gly) lead to sustained channel opening, continuous influx of Ca2+ into cells, causing calcium overload and inducing increased apoptosis of keratinocytes, which may result in the hyperkeratosis observed in OS. In 2015, transcriptomic and proteomic studies on skin lesions and non-lesions of OS patients carrying the p.Gln580Pro mutation revealed downregulation of proteins involved in keratinocyte differentiation and cell-cell connections, while proteins related to keratinocyte proliferation and cell death were upregulated, suggesting that TRPV3 mutations may disrupt the balance between keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation, impairing cell adhesion function (He et al., 2015).

In 2017, further in vitro studies found that TRPV3 mutants (p.Gly573Ala, p.Gly573Cys, p.Gly573Ser, and p.Trp692Gly) exhibited reduced membrane surface localization in HaCaT cells, being mainly localized to the endoplasmic reticulum. These mutations also reduced cell adhesion, abnormal lysosomal and endoplasmic reticulum functions, and mitochondrial aggregation (Yadav and Goswami, 2017). Further research found that in cells expressing the p.Gly568Cys and p.Gly568Asp mutants, there was a significant reduction in the number of lysosomes (Jain et al., 2022). The p.Gly568Cys mutant showed decreased lysosomal movement, while the p.Gly568Asp mutant cells exhibited reduced lysosomal acidification levels. Notably, the Ca2+ levels within lysosomes closely relate to their pH regulation (Scott and Gruenberg, 2011; Cao et al., 2017). This is because lysosomes need to retain more Ca2+ to maintain their low pH, and uncontrolled release of Ca2+ can lead to difficulties in lysosomal lumen acidification (Koh et al., 2019). Therefore, the p.Gly568Cys and p.Gly568Asp mutants may act as Ca2+ leak channels in lysosomes to varying degrees (Jain et al., 2022). However, whether similar phenomenon could be found in other subcellular organelles with other mutations in different TRPV3 structural domains needs to be further investigated. Meantime, it may also disrupt the balance between keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation, thereby contributing to the development of OS.

Increasing evidence suggests that the wild-type TRPV3 can regulate hair development and epidermal keratinization by activating the EGFR pathway in keratinocytes, and different degrees of activation of the wild-type TRPV3 channel may have various regulatory effects on keratinocytes. In 2010, researchers found that mice with keratinocytes-specific knockout of the Trpv3 gene had wavy hair and defects in the skin barrier (Cheng et al., 2010). Further studies revealed that TRPV3 forms a signaling complex with transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α)/EGFR. The constitutive low-level activity of TRPV3 can activate EGFR at a low level, and downstream activation of ERK can further sensitize TRPV3, forming a positive feedback loop. This loop plays a crucial role in normal hair development, terminal differentiation of suprabasal keratinocytes, and the formation of the skin barrier cornified envelope (Cheng et al., 2010). Recent research reported that lower concentrations (30 μM or 100 μM) of carvacrol can moderately activate TRPV3, which then promotes proliferation in HaCaT cells and epidermal hyperplasia in mice through the activation of the EGFR/PI3K/NF-κB pathway (Grubisha et al., 2014).

Several studies have found that higher concentrations of TRPV3 agonists (such as 300 μM carvacrol) can lead to excessive activation of the wild-type TRPV3 channel, inducing apoptosis/death of keratinocytes (Zhang et al., 2019; Yan et al., 2019; Szollosi et al., 2018). Blocking NF-κB can further increase cell death (Szollosi et al., 2018). Therefore, some researchers propose that the excessive activation of the TRPV3 channel may also promote keratinocytes proliferation through the EGFR/PI3K/NF-κB pathway. However, this effect is masked by the massive cell death (apoptotic effect) caused by excessive channel activation (Grubisha et al., 2014).

Dermatitis

Previous studies on mouse models also suggest that TRPV3 mediates the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1α (Xu et al., 2006) and PGE2 (Huang et al., 2008), essential mediators of skin inflammation. Lin et al. (2012) found that the mutated human TRPV3 channel exhibited constitutive activity when expressed in HEK293 cells and led to the death of transfected HEK293 cells, as well as apoptosis of keratinocytes in skin biopsy sections from affected individuals. Studies indicate that the in vitro activation of TRPV3 and gain-of-function mutations can lead to significant skin inflammation in humans and rodents (Song et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2012; Szollosi et al., 2018; Yoshioka et al., 2009; Danso-Abeam et al., 2013). For example, recent findings show that the excessive activation of wild-type TRPV3 channels induced by high concentrations (300 μM) of carvacrol induces KC apoptosis and activates the NF-κB pathway to promote the release of various inflammatory mediators (Szollosi et al., 2018). Pathological examination of skin lesions in OS patients reveals psoriasis-like epidermal hyperplasia and infiltration of inflammatory cells in the upper dermis (Lin et al., 2012). Skin thickening, inflammatory reactions, and itching can be observed in WBN/Kob-Ht rats carrying the p.Gly573Cys mutation and DS-Nh mice carrying the p.Gly573Ser mutation (Yoshioka et al., 2009). As most OS patients have heterozygous mutations in TRPV3, to better simulate the clinical situation, Trpv3+/p.Gly568Val mice were created. Clinical manifestations include skin thickening and reduced hair, and histopathology shows significant epidermal hyperplasia and pronounced infiltration of inflammatory cells (Song et al., 2021).

Hair loss

In cultured human ORS keratinocytes, activation of TRPV3 induces membrane currents, increases intracellular calcium ions, inhibits cell proliferation, induces cell apoptosis, suppresses hair shaft elongation, and promotes premature regression of hair follicles. These cellular effects, including hair growth inhibition, are blocked by siRNA-mediated knockdown of TRPV3 (Borbiro et al., 2011). Gain-of-function mutations in TRPV3 alter the hair growth cycle in mice, namely, the process of follicular growth (anagen phase) and regression (telogen phase). In DS-Nh mice, genes related to the hair growth cycle, such as keratin-associated proteins 16–1, 16–3, and 16–9, are downregulated in the skin, and the anagen phase persists (Imura et al., 2007).

Song et al. (2021) generated an OS mouse model by introducing the p.Gly568Val point mutation in the corresponding TRPV3 locus in mice. They found that these mice exhibited alopecia, which was associated with premature differentiation of hair follicle keratinocytes, characterized by early senescence of hair keratin and trichohyalin, increased production of deiminated proteins, enhanced apoptosis, and reduced expression of transcription factors known to regulate hair follicle differentiation (Foxn1, Msx2, Dlx3, and Gata3). These abnormalities occurred in the inner root sheath and proximal hair shaft regions, where TRPV3 is highly expressed and associated with impaired hair shaft and canal formation. Mutant Trpv3 mice showed increased proliferation of ORS, accelerated hair cycle, reduced hair follicle stem cells, and miniaturization of regenerative hair follicles.

Itch

The first signs of itch mediated by TRPV3 come from mutant mice. DS-Nh mice and WBN/Kob-Ht rats, both carrying autosomal dominant TRPV3 mutations, exhibit symptoms of atopic dermatitis (AD), including itchiness (Watanabe et al., 2003; Asakawa et al., 2005). Yoshioka et al. (2009) developed transgenic mice expressing mutant p.Gly573Ser in TRPV3 and found that these mice spontaneously exhibited scratching behavior after developing dermatitis, indicating that TRPV3 gene mutations cause itching. Yang et al. (2015) applied a TRPV3 agonist, carvacrol, to human burn scars and effectively induced itchiness. Enhanced TRPV3 expression was also detected in the epidermis of burn scars accompanied by itchiness (Kim et al., 2020). Compared to AD patients without itchiness, AD patients with itchiness showed increased levels of TRPV3 mRNA transcripts (Yamamoto-Kasai et al., 2012). These findings strongly support the hypothesis that TRPV3 plays a crucial role in chronic itch associated with skin dryness in mice and human.

Upon heat stimulation or activation by TRPV3 agonists, activated TRPV3 induces itchiness by promoting the secretion of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), nerve growth factor (NGF), PGE2, and IL-33 by keratinocytes (Seo et al., 2020). Inflammation may also play an essential role in the propagation of TRPV3-mediated itchiness, as inflammatory factors such as IL-31 induce high expression of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), activate TRPV3, upregulate expression of Serpin E1, and cause skin itching (Asakawa et al., 2006; Meng et al., 2018; Larkin et al., 2021).

Additionally, the lack of TRPV3 in keratinocytes impaired the function of protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2), leading to reduced activation of neurons by PAR2 agonists and decreased scratching behavior. Zhao et al. (2020) found that TRPV3 and PAR2 were upregulated in skin biopsy tissues from patients and mice with AD, and inhibition of TRPV3 and PAR2 reduced scratching and inflammatory responses in a mouse model of AD.

Pain

Over the past decade, extensive research has been conducted on the role of TRPV3 in pain sensation. However, few studies have provided conclusive evidence for TRPV3-mediated pain. TRPV3 is expressed in nociceptive neurons. Therefore, overactivation of TRPV3 may also lead to excessive production of local inflammatory cytokines, affecting the somatosensory system and resulting in peripheral neuropathic pain. Additionally, ATP released by TRPV3-mediated keratinocytes can activate purinergic receptors in dorsal root ganglion neurons, affecting nociceptive function. Consistent with this, transgenic mice overexpressing TRPV3 in skin keratinocytes showed increased pain sensitivity (Huang et al., 2008). As a thermosensitive ion channel, TRPV3 is suspected to be associated with thermal nociception, as demonstrated by the disrupted response of Trpv3 knockout mice to acute noxious heat (>48°C) in water immersion and hot plate (>52°C) experiments (Moqrich et al., 2005). Apart from thermal nociception, TRPV3 also mediates chemically induced acute nociceptive responses. FPP, an intermediate metabolite of the mevalonate pathway, is a selective TRPV3 agonist. Injection of FPP into the paw of carrageenan-pretreated mice induces rapid pain-related behaviors but not in non-sensitized mice. Knockdown of TRPV3 in the paws of mice using TRPV3-shRNA significantly alleviates FPP-induced pain-related behaviors but does not affect pain induced by the TRPV1 activator capsaicin (Bang et al., 2010). However, the role of TRPV3 in thermal nociception remains controversial. Huang et al. (2011) demonstrated that TRPV3-deficient mice showed no changes in acute thermal pain or inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia, suggesting that TRPV3 may not be a significant factor in thermal nociception.

Management including treatments

Traditional management and treatments

Various treatment methods have been attempted in the past to reduce excessive keratinization (Supplementary Table S2). Topical therapies include emollients (white petrolatum), keratolytic agents (urea, salicylic acid), wet dressings, boric acid, tar, retinoids, shale oil, corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors, but their efficacy is generally poor to moderate. In some OS patients, systemic use of retinoids (acitretin, isotretinoin), corticosteroids, or methotrexate has resulted in varying degrees of relief from poor to moderate (Ueda et al., 1993; Tang et al., 2012; Rivers et al., 1985; Hausser et al., 1993). A few patients have also undergone repeated partial or full-thickness excision with skin grafting of the palmar-plantar keratoderma, but keratinization often recurs after initial improvement (Bedard et al., 2008). Regarding specific treatments for pain and itching, analgesics and topical lidocaine may be effective. Still, for patients with severe pain, especially when erythromelalgia or neuropathic pain is present, anti-inflammatory drugs, anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, gabapentin, pregabalin), tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, desipramine), and ultimately opioid analgesics (tramadol) are needed to alleviate their pain (Duchatelet and Hovnanian, 2015). Soaking the affected areas in cold water for a prolonged period can relieve pain. However, these treatments are ineffective in preventing disease progression.

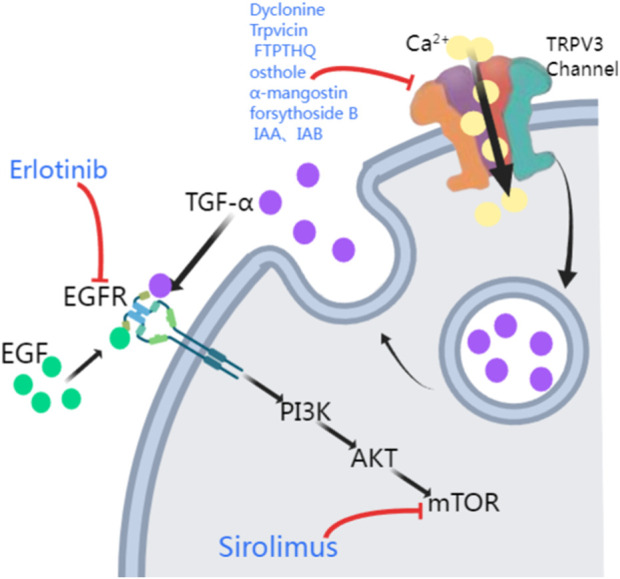

EGFR inhibitors and mTOR inhibitors

The TRPV3 gene encodes a channel that allows calcium ion influx into keratinocytes. As mentioned previously, downstream of EGFR signaling pathway plays an important role in maintaining epidermal homeostasis by forming a complex with TRPV3 (Zhong et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2010). In 2020, Greco et al. (2020) demonstrated relief from TRPV3 mutation-associated PPK, pain, and hyperkeratosis in three OS patients treated with the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib. These patients showed complete relief from hyperkeratosis and pain within 3 months of erlotinib therapy, leading to better growth and social engagement for the benefits lasted for 12 months (Greco et al., 2020). Amplification of EGFR leads to the activation of many downstream kinases, including mammalian targets of rapamycin (mTOR) (Wee and Wang, 2017) (Figure 2). Zhang et al. (2020) proposed that TRPV3 mutations are associated with the pathogenesis of OS, possibly involving the EGFR-mTOR cascade, leading to skin inflammation and hyperproliferation. Oral administration of the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus in children with OS resulted in significant improvement in skin inflammation and periorificial hyperkeratotic plaques, while a substantial reduction in PPK and associated functional limitations was observed with the clinical response to erlotinib. In this study, two patients were first treated with sirolimus, which resulted in considerable improvement in erythema and periorificial hyperkeratosis. Following the transition to erlotinib, significant progress in PPK was also noted. The other two OS patients, treated only with erlotinib, had rapid PPK resolution and better quality-of-life scores (Bedard et al., 2008). In forementioned two studies, all patients presented sustained improvements in itching and pain, without severe side effects reported. EGFR inhibitors (e.g., erlotinib) and mTOR inhibitors (e.g., sirolimus) may be potential treatment options for OS hyperkeratosis, showing clinical improvements in hyperkeratosis, pain, and other symptoms in OS patients, which suggests that the EGFR and mTOR pathways are key therapeutic targets (Zhong et al., 2021; Greco et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020; Kenner-Bell et al., 2010; Fogel et al., 2015; Buerger et al., 2017). However, more case series and further basic researches are needed to elucidate the importance of EGFR and mTOR in the pathogenesis of TRPV3-related OS and the subsequent therapeutic effect of respective signaling inhibitors, thus contributing to the individualized therapy respective to different TRPV3 mutations.

FIGURE 2.

Potential treatments of TRPV3 mutation-related OS. The activation of TRPV3 channels leads to Ca2+ influx, which causes a surge in intracellular Ca2+ signaling, promoting the release of TGF-α. TGF-α and EGF then activate their receptor EGFR, activating the EGFR/PI3K/AKT/mTOR cascade. TRPV3 antagonists (Dyclonine, Trpvicin, FTP-THQ, osthole, α-mangostin, forsythoside B, IAA, and IAB) inhibit the TRPV3 channel. Erlotinib and Sirolimus inhibit EGFR and mTOR respectively (PI3K: phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; AKT: protein kinase B, PKB).

TRPV3 antagonists

Gain-of-function mutations in the TRPV3 gene are responsible for increased apoptosis of affected individuals’ keratinocytes and excessive skin keratinization. Therefore, TRPV3 antagonists may be a practical therapeutic approach for treating OS patients carrying such mutations. Liu et al. (2021) reported that the clinical drug dyclonine inhibits TRPV3, relieving skin inflammation. However, due to the relatively low affinity of dyclonine for TRPV3, the information provided by the structure-based drug optimization is limited. Fan et al. (2023) found that the TRPV3 antagonist Trpvicin effectively relieved OS-like symptoms in a mouse model. However, particularly in chronic itching and hair loss mouse models, it is necessary to conduct pharmacokinetic studies on mouse skin to detect drug exposure further to ensure that the observed efficacy is due to TRPV3 blockade by Trpvicin. Hydra Inc.’s FTP-THQ is an efficient and selective in vitro antagonist of recombinant and native TRPV3 receptors, with almost no activity against TRPV1, TRPV4, TRPM8, and TRPA1 (Grubisha et al., 2014). FTP-THQ has now been evaluated in vitro for its effects on m308 keratinocytes, confirming its ability to block ATP and GM-CSF release by aggregating DPBA and 2-APB, known to selectively activate TRPV3 in these cells (Luo and Hu, 2014).

Many herbal extracts also inhibit TRPV3, including osthole, α-mangostin, forsythoside B, and isomers of isochlorogenic acid (Figure 2). Research has shown that osthole, an active ingredient in fructus cnidii, has been used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat eczema. Osthole inhibits TRPV3, and Neuberger et al. (2021) revealed two osthole binding sites on the transmembrane region of TRPV3, which overlap with the binding site of the agonist 2-APB. So far, osthole and its derivatives have been limited in disease treatment due to the need for high concentrations and their action on multiple targets (Kim et al., 2020). α-Mangostin, an extract from the pericarp of Garcinia mangostana, effectively inhibits TRPV3, reducing calcium influx and cytokine release, protecting cells from TRPV3-induced death, and has inhibitory effects on both wild-type and mutant TRPV3 (Dang et al., 2023). Forsythoside B inhibits channel currents activated by the agonist 2-aminoethyl diphenyl borate, and its pharmacological inhibition of TRPV3 significantly alleviates acute itching induced by carvacrol or histamine, as well as chronic itching caused by acetone-ether-water in mice with dry skin. Additionally, forsythoside B can prevent cell death in human keratinocytes expressing the TRPV3 p.Gly573Ser gain-of-function mutation or in HEK293 cells or naturally immortalized non-carcinogenic keratinocytes in the presence of the TRPV3 agonist carvacrol (Zhang et al., 2019). Forsythoside B also significantly reverses the inhibitory effect of carvacrol on hair growth (Yan et al., 2019). Two natural isomers of isochlorogenic acid, IAA and IAB, act as TRPV3 channel gating modifiers, selectively inhibiting channel currents by reducing channel opening probability. IAA and IAB can alleviate excessive activation of TRPV3-induced keratinocyte death, ear swelling, and chronic itching (Qi et al., 2022).

Conclusion and future perspectives

This review summarizes the pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic advances of OS associated with TRPV3 mutations. Despite obtaining compelling evidence from TRPV3 mutant alleles and transgenic mice, the low selectivity of TRPV3 antagonists has diminished reliability. Therefore, future research is required to develop TRPV3 antagonists with higher selectivity. In conclusion, this review elucidates the main clinical symptoms and mechanisms of TRPV3 mutation-related OS, laying the foundation for the individual treatment of OS.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shenzhen Public Service Platform for Molecular Diagnosis of Dermatology for theoretical support.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82203900), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2021A1515111009), Shenzhen Sanming Project (No. SZSM202311029) and Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund (No. SZXK040).

Author contributions

AL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. KL: Supervision, Writing–review and editing. CH: Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing–review and editing. BY: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing–review and editing. WZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing–review and editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2024.1459109/full#supplementary-material

Glossary

- AD

Atopic dermatitis

- AKT (PKB)

Protein kinase B

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- BNP

Brain natriuretic peptide

- DPBA

Dipeptide boronic acid

- DRG

Dorsal root ganglia

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- FPP

Farnesyl pyrophosphate

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor

- IA

Isochlorogenic acid

- KC

Keratinocyte

- MBTPS2

Membrane-bound transcription factor peptidase, site-2

- mTOR

Mammalian targets of rapamycin

- NGF

Nerve growth factor

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-B

- ORS

Outer root sheath

- OS

Olmsted syndrome

- PAR2

Protease-activated receptor 2

- PERP

p53 effector related to PMP-22

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- PIP2

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- PPK

Palmoplantar keratoderma

- S2P

Site-2 protease

- TGF-α

Transforming growth factor-α

- TRP

Transient receptor potential

- TRPA1

Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1

- TRPM8

Transient receptor potential melastatin 8

- TRPV3

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 3

- TSLP

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin

- 2-APB

2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate

References

- Aijima R., Wang B., Takao T., Mihara H., Kashio M., Ohsaki Y., et al. (2015). The thermosensitive TRPV3 channel contributes to rapid wound healing in oral epithelia. FASEB J. 29 (1), 182–192. 10.1096/fj.14-251314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa M., Yoshioka T., Hikita I., Matsutani T., Hirasawa T., Arimura A., et al. (2005). WBN/Kob-Ht rats spontaneously develop dermatitis under conventional conditions: another possible model for atopic dermatitis. Exp. Anim. 54 (5), 461–465. 10.1538/expanim.54.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa M., Yoshioka T., Matsutani T., Hikita I., Suzuki M., Oshima I., et al. (2006). Association of a mutation in TRPV3 with defective hair growth in rodents. J. Invest Dermatol 126 (12), 2664–2672. 10.1038/sj.jid.5700468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang S., Yoo S., Yang T. J., Cho H., Hwang S. W. (2010). Farnesyl pyrophosphate is a novel pain-producing molecule via specific activation of TRPV3. J. Biol. Chem. 285 (25), 19362–19371. 10.1074/jbc.M109.087742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard M. S., Powell J., Laberge L., Allard-Dansereau C., Bortoluzzi P., Marcoux D. (2008). Palmoplantar keratoderma and skin grafting: postsurgical long-term follow-up of two cases with Olmsted syndrome. Pediatr. Dermatol. 25 (2), 223–229. 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbiro I., Lisztes E., Toth B. I., Czifra G., Olah A., Szollosi A. G., et al. (2011). Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid-3 inhibits human hair growth. J. Invest Dermatol 131 (8), 1605–1614. 10.1038/jid.2011.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerger C., Shirsath N., Lang V., Berard A., Diehl S., Kaufmann R., et al. (2017). Inflammation dependent mTORC1 signaling interferes with the switch from keratinocyte proliferation to differentiation. PLoS One 12 (7), e0180853. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caengprasath N., Theerapanon T., Porntaveetus T., Shotelersuk V. (2021). MBTPS2, a membrane bound protease, underlying several distinct skin and bone disorders. J. Transl. Med. 19 (1), 114. 10.1186/s12967-021-02779-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q., Yang Y., Zhong X. Z., Dong X. P. (2017). The lysosomal Ca(2+) release channel TRPML1 regulates lysosome size by activating calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 292 (20), 8424–8435. 10.1074/jbc.M116.772160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Yang F., Zheng J., Wang K. (2012). Intracellular proton-mediated activation of TRPV3 channels accounts for the exfoliation effect of α-hydroxyl acids on keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 287 (31), 25905–25916. 10.1074/jbc.M112.364869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Jin J., Hu L., Shen D., Dong X. P., Samie M. A., et al. (2010). TRP channel regulates EGFR signaling in hair morphogenesis and skin barrier formation. Cell 141 (2), 331–343. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu F. P., Salas-Alanis J. C., Amaya-Guerra M., Cepeda-Valdes R., McGrath J. A., Hsu C. K. (2020). Novel p.Ala675Thr missense mutation in TRPV3 in Olmsted syndrome. Clin. Exp. Dermatol 45 (6), 796–798. 10.1111/ced.14228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M. K., Guler A. D., Caterina M. J. (2005). Biphasic currents evoked by chemical or thermal activation of the heat-gated ion channel, TRPV3. J. Biol. Chem. 280 (16), 15928–15941. 10.1074/jbc.M500596200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M. K., Lee H., Mizuno A., Suzuki M., Caterina M. J. (2004a). TRPV3 and TRPV4 mediate warmth-evoked currents in primary mouse keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (20), 21569–21575. 10.1074/jbc.M401872200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M. K., Lee H., Mizuno A., Suzuki M., Caterina M. J. (2004b). 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate activates and sensitizes the heat-gated ion channel TRPV3. J. Neurosci. 24 (22), 5177–5182. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0934-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang T. H., Kim J. Y., Kim H. J., Kim B. J., Kim W. K., Nam J. H. (2023). Alpha-mangostin: a potent inhibitor of TRPV3 and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion in keratinocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (16), 12930. 10.3390/ijms241612930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danso-Abeam D., Zhang J., Dooley J., Staats K. A., Van Eyck L., Van Brussel T., et al. (2013). Olmsted syndrome: exploration of the immunological phenotype. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 8, 79. 10.1186/1750-1172-8-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchatelet S., Boyden L. M., Ishida-Yamamoto A., Zhou J., Guibbal L., Hu R., et al. (2019). Mutations in PERP cause dominant and recessive keratoderma. J. Invest Dermatol. 139 (2), 380–390. 10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchatelet S., Hovnanian A. (2015). Olmsted syndrome: clinical, molecular and therapeutic aspects. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 10, 33. 10.1186/s13023-015-0246-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchatelet S., Pruvost S., de Veer S., Fraitag S., Nitschke P., Bole-Feysot C., et al. (2014). A new TRPV3 missense mutation in a patient with Olmsted syndrome and erythromelalgia. JAMA Dermatol 150 (3), 303–306. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elise Tonoli R., De Villa D., Hubner Frainer R., Pizzarro Meneghello L., Ricachnevsky N., de Quadros M. (2012). Olmsted syndrome. Case Rep. Dermatol Med. 2012, 927305. 10.1155/2012/927305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Hu L., Yue Z., Liao D., Guo F., Ke H., et al. (2023). Structural basis of TRPV3 inhibition by an antagonist. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19 (1), 81–90. 10.1038/s41589-022-01166-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel A. L., Hill S., Teng J. M. (2015). Advances in the therapeutic use of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors in dermatology. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 72 (5), 879–889. 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandl J., Kim S. E., Uzzell V., Bursulaya B., Petrus M., Bandell M., et al. (2010). Temperature-induced opening of TRPV1 ion channel is stabilized by the pore domain. Nat. Neurosci. 13 (6), 708–714. 10.1038/nn.2552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco C., Leclerc-Mercier S., Chaumon S., Doz F., Hadj-Rabia S., Molina T., et al. (2020). Use of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor erlotinib to treat palmoplantar keratoderma in patients with olmsted syndrome caused by TRPV3 mutations. JAMA Dermatol 156 (2), 191–195. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubisha O., Mogg A. J., Sorge J. L., Ball L. J., Sanger H., Ruble C. L., et al. (2014). Pharmacological profiling of the TRPV3 channel in recombinant and native assays. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171 (10), 2631–2644. 10.1111/bph.12303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausser I., Frantzmann Y., Anton-Lamprecht I., Estes S., Frosch P. J. (1993). Olmsted syndrome. Successful therapy by treatment with etretinate. Hautarzt 44 (6), 394–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Zeng K., Zhang X., Chen Q., Wu J., Li H., et al. (2015). A gain-of-function mutation in TRPV3 causes focal palmoplantar keratoderma in a Chinese family. J. Invest Dermatol 135 (3), 907–909. 10.1038/jid.2014.429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H. Z., Xiao R., Wang C., Gao N., Colton C. K., Wood J. D., et al. (2006). Potentiation of TRPV3 channel function by unsaturated fatty acids. J. Cell Physiol. 208 (1), 201–212. 10.1002/jcp.20648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. M., Lee H., Chung M. K., Park U., Yu Y. Y., Bradshaw H. B., et al. (2008). Overexpressed transient receptor potential vanilloid 3 ion channels in skin keratinocytes modulate pain sensitivity via prostaglandin E2. J. Neurosci. 28 (51), 13727–13737. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5741-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. M., Li X., Yu Y., Wang J., Caterina M. J. (2011). TRPV3 and TRPV4 ion channels are not major contributors to mouse heat sensation. Mol. Pain 7, 37. 10.1186/1744-8069-7-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imura K., Yoshioka T., Hikita I., Tsukahara K., Hirasawa T., Higashino K., et al. (2007). Influence of TRPV3 mutation on hair growth cycle in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 363 (3), 479–483. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A., Sahu R. P., Goswami C. (2022). Olmsted syndrome causing point mutants of TRPV3 (G568C and G568D) show defects in intracellular Ca(2+)-mobilization and induce lysosomal defects. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 628, 32–39. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenner-Bell B. M., Paller A. S., Lacouture M. E. (2010). Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition with erlotinib for palmoplantar keratoderma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 63 (2), e58–e59. 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. O., Jin Cheol K., Yu Gyeong K., In Suk K. (2020). Itching caused by TRPV3 (transient receptor potential vanilloid-3) activator application to skin of burn patients. Med. Kaunas. 56 (11), 560. 10.3390/medicina56110560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. E., Patapoutian A., Grandl J. (2013). Single residues in the outer pore of TRPV1 and TRPV3 have temperature-dependent conformations. PLoS One 8 (3), e59593. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh J. Y., Kim H. N., Hwang J. J., Kim Y. H., Park S. E. (2019). Lysosomal dysfunction in proteinopathic neurodegenerative disorders: possible therapeutic roles of cAMP and zinc. Mol. Brain 12 (1), 18. 10.1186/s13041-019-0439-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress D. W., Seraly M. P., Falo L., Kim B., Jegasothy B. V., Cohen B. (1996). Olmsted syndrome. Case report and identification of a keratin abnormality. Arch. Dermatol 132 (7), 797–800. 10.1001/archderm.132.7.797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin C., Chen W., Szabo I. L., Shan C., Dajnoki Z., Szegedi A., et al. (2021). Novel insights into the TRPV3-mediated itch in atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 147 (3), 1110–1114.e5. 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Chen Q., Lee M., Cao X., Zhang J., Ma D., et al. (2012). Exome sequencing reveals mutations in TRPV3 as a cause of Olmsted syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90 (3), 558–564. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Yao J., Zhu M. X., Qin F. (2011). Hysteresis of gating underlines sensitization of TRPV3 channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 138 (5), 509–520. 10.1085/jgp.201110689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Wang J., Wei X., Hu J., Ping C., Gao Y., et al. (2021). Therapeutic inhibition of keratinocyte TRPV3 sensory channel by local anesthetic dyclonine. Elife 10, e68128. 10.7554/eLife.68128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Hu R., Liu L., Ding H. (2021). Analysis of clinical feature and genetic basis of a rare case with Olmsted syndrome. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi 38 (7), 674–677. 10.3760/cma.j.cn511374-20200811-00597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Hu H. (2014). Thermally activated TRPV3 channels. Curr. Top. Membr. 74, 325–364. 10.1016/B978-0-12-800181-3.00012-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Stewart R., Berdeaux R., Hu H. (2012). Tonic inhibition of TRPV3 by Mg2+ in mouse epidermal keratinocytes. J. Invest Dermatol 132 (9), 2158–2165. 10.1038/jid.2012.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J., Moriyama M., Feld M., Buddenkotte J., Buhl T., Szollosi A., et al. (2018). New mechanism underlying IL-31-induced atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 141 (5), 1677–1689.e8. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T., Petrus M. J., Dubin A. E., Patapoutian A. (2011). TRPV3 regulates nitric oxide synthase-independent nitric oxide synthesis in the skin. Nat. Commun. 2, 369. 10.1038/ncomms1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moqrich A., Hwang S. W., Earley T. J., Petrus M. J., Murray A. N., Spencer K. S., et al. (2005). Impaired thermosensation in mice lacking TRPV3, a heat and camphor sensor in the skin. Science 307 (5714), 1468–1472. 10.1126/science.1108609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuberger A., Nadezhdin K. D., Zakharian E., Sobolevsky A. I. (2021). Structural mechanism of TRPV3 channel inhibition by the plant-derived coumarin osthole. EMBO Rep. 22 (11), e53233. 10.15252/embr.202153233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni C., Yan M., Zhang J., Cheng R., Liang J., Deng D., et al. (2016). A novel mutation in TRPV3 gene causes atypical familial Olmsted syndrome. Sci. Rep. 6, 21815. 10.1038/srep21815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noakes R. (2021). Olmsted Syndrome: response to erlotinib therapy and genotype/phenotype correlation. Australas. J. Dermatol 62 (3), 445–446. 10.1111/ajd.13663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nofal A., Assaf M., Nassar A., Nofal E., Shehab M., El-Kabany M. (2010). Nonmutilating palmoplantar and periorificial keratoderma: a variant of Olmsted syndrome or a distinct entity? Int. J. Dermatol 49 (6), 658–665. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04429.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. W., Kim H. J., Choi Y. W., Chung B. Y., Woo S. Y., Song D. K., et al. (2017). TRPV3 channel in keratinocytes in scars with post-burn pruritus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (11), 2425. 10.3390/ijms18112425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peier A. M., Reeve A. J., Andersson D. A., Moqrich A., Earley T. J., Hergarden A. C., et al. (2002). A heat-sensitive TRP channel expressed in keratinocytes. Science 296 (5575), 2046–2049. 10.1126/science.1073140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H., Shi Y., Wu H., Niu C., Sun X., Wang K. (2022). Inhibition of temperature-sensitive TRPV3 channel by two natural isochlorogenic acid isomers for alleviation of dermatitis and chronic pruritus. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 12 (2), 723–734. 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin C. A., Tu J. H. (1997). Keratin expression in Olmsted syndrome. Arch. Dermatol 133 (3), 389. 10.1001/archderm.1997.03890390133024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Requena L., Manzarbeitia F., Moreno C., Izquierdo M. J., Pastor M. A., Carrasco L., et al. (2001). Olmsted syndrome: report of a case with study of the cellular proliferation in keratoderma. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 23 (6), 514–520. 10.1097/00000372-200112000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers J. K., Duke E. E., Justus D. W. (1985). Etretinate: management of keratoma hereditaria mutilans in four family members. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 13 (1), 43–49. 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70141-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott C. C., Gruenberg J. (2011). Ion flux and the function of endosomes and lysosomes: pH is just the start: the flux of ions across endosomal membranes influences endosome function not only through regulation of the luminal pH. Bioessays 33 (2), 103–110. 10.1002/bies.201000108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo S. H., Kim S., Kim S. E., Chung S., Lee S. E. (2020). Enhanced thermal sensitivity of TRPV3 in keratinocytes underlies heat-induced pruritogen release and pruritus in atopic dermatitis. J. Invest Dermatol 140 (11), 2199–2209.e6. 10.1016/j.jid.2020.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. K., McGoldrick L. L., Sobolevsky A. I. (2018). Structure and gating mechanism of the transient receptor potential channel TRPV3. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25 (9), 805–813. 10.1038/s41594-018-0108-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. D., Gunthorpe M. J., Kelsell R. E., Hayes P. D., Reilly P., Facer P., et al. (2002). TRPV3 is a temperature-sensitive vanilloid receptor-like protein. Nature 418 (6894), 186–190. 10.1038/nature00894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z., Chen X., Zhao Q., Stanic V., Lin Z., Yang S., et al. (2021). Hair loss caused by gain-of-function mutant TRPV3 is associated with premature differentiation of follicular keratinocytes. J. Invest Dermatol. 141 (8), 1964–1974. 10.1016/j.jid.2020.11.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szollosi A. G., Vasas N., Angyal A., Kistamas K., Nanasi P. P., Mihaly J., et al. (2018). Activation of TRPV3 regulates inflammatory actions of human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Invest Dermatol. 138 (2), 365–374. 10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L., Zhang L., Ding H., Wang X., Wang H. (2012). Olmsted syndrome: a new case complicated with easily broken hair and treated with oral retinoid. J. Dermatol 39 (9), 816–817. 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01535.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J., Huang C. Z., Yu N. W., Wu Y., Liu Y. Q., Li Y., et al. (2008). Olmsted syndrome: a case report and review of literature. Int. J. Dermatol 47 (5), 432–437. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03595.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda M., Nakagawa K., Hayashi K., Shimizu R., Ichihashi M. (1993). Partial improvement of Olmsted syndrome with etretinate. Pediatr. Dermatol 10 (4), 376–381. 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1993.tb00404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt-Eisele A. K., Weber K., Sherkheli M. A., Vielhaber G., Panten J., Gisselmann G., et al. (2007). Monoterpenoid agonists of TRPV3. Br. J. Pharmacol. 151 (4), 530–540. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Li H., Xue C., Chen H., Xue Y., Zhao F., et al. (2021). TRPV3 enhances skin keratinocyte proliferation through EGFR-dependent signaling pathways. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 37 (2), 313–330. 10.1007/s10565-020-09536-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe A., Takeuchi M., Nagata M., Nakamura K., Nakao H., Yamashita H., et al. (2003). Role of the Nh (Non-hair) mutation in the development of dermatitis and hyperproduction of IgE in DS-Nh mice. Exp. Anim. 52 (5), 419–423. 10.1538/expanim.52.419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee P., Wang Z. (2017). Epidermal growth factor receptor cell proliferation signaling pathways. Cancers (Basel) 9 (5), 52. 10.3390/cancers9050052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N. J., Cole C., Milstone L. M., Kiszewski A. E., Hansen C. D., O'Toole E. A., et al. (2015). Expanding the phenotypic spectrum of olmsted syndrome. J. Invest Dermatol. 135 (11), 2879–2883. 10.1038/jid.2015.217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R., Tang J., Wang C., Colton C. K., Tian J., Zhu M. X. (2008). Calcium plays a central role in the sensitization of TRPV3 channel to repetitive stimulations. J. Biol. Chem. 283 (10), 6162–6174. 10.1074/jbc.M706535200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Delling M., Jun J. C., Clapham D. E. (2006). Oregano, thyme and clove-derived flavors and skin sensitizers activate specific TRP channels. Nat. Neurosci. 9 (5), 628–635. 10.1038/nn1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Ramsey I. S., Kotecha S. A., Moran M. M., Chong J. A., Lawson D., et al. (2002). TRPV3 is a calcium-permeable temperature-sensitive cation channel. Nature 418 (6894), 181–186. 10.1038/nature00882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav M., Goswami C. (2017). TRPV3 mutants causing Olmsted Syndrome induce impaired cell adhesion and nonfunctional lysosomes. Channels (Austin). 11 (3), 196–208. 10.1080/19336950.2016.1249076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto-Kasai E., Imura K., Yasui K., Shichijou M., Oshima I., Hirasawa T., et al. (2012). TRPV3 as a therapeutic target for itch. J. Invest Dermatol 132 (8), 2109–2112. 10.1038/jid.2012.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan K., Sun X., Wang G., Liu Y., Wang K. (2019). Pharmacological activation of thermo-transient receptor potential vanilloid 3 channels inhibits hair growth by inducing cell death of hair follicle outer root sheath. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 370 (2), 299–307. 10.1124/jpet.119.258087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. S., Cho S. I., Choi M. G., Choi Y. H., Kwak I. S., Park C. W., et al. (2015). Increased expression of three types of transient receptor potential channels (TRPA1, TRPV4 and TRPV3) in burn scars with post-burn pruritus. Acta Derm. Venereol. 95 (1), 20–24. 10.2340/00015555-1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka T., Imura K., Asakawa M., Suzuki M., Oshima I., Hirasawa T., et al. (2009). Impact of the Gly573Ser substitution in TRPV3 on the development of allergic and pruritic dermatitis in mice. J. Invest Dermatol 129 (3), 714–722. 10.1038/jid.2008.245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuspa S. H., Kulesz-Martin M., Ben T., Hennings H. (1983). Transformation of epidermal cells in culture. J. Invest Dermatol. 81 (1), 162s–8s. 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12540999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A., Duchatelet S., Lakdawala N., Tower R. L., Diamond C., Marathe K., et al. (2020). Targeted inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor and mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathways in olmsted syndrome. JAMA Dermatol 156 (2), 196–200. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Sun X., Qi H., Ma Q., Zhou Q., Wang W., et al. (2019). Pharmacological inhibition of the temperature-sensitive and Ca(2+)-permeable transient receptor potential vanilloid TRPV3 channel by natural forsythoside B attenuates pruritus and cytotoxicity of keratinocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 368 (1), 21–31. 10.1124/jpet.118.254045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Munanairi A., Liu X. Y., Zhang J., Hu L., Hu M., et al. (2020). PAR2 mediates itch via TRPV3 signaling in keratinocytes. J. Invest Dermatol 140 (8), 1524–1532. 10.1016/j.jid.2020.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W., Hu L., Cao X., Zhao J., Zhang X., Lee M., et al. (2021). Genotype‒phenotype correlation of TRPV3-related olmsted syndrome. J. Invest Dermatol. 141 (3), 545–554. 10.1016/j.jid.2020.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.